#to the Alps rather than central Italy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Gonna nitpick (and I'm loving the movie so far) but I'm getting a bit of whiplash between the "this is set in magical fantasy mishmash Italy" and the "we're gonna ground this story in a very specific geographical area and historical period"

The original fairytale is set in Tuscany, but if you want the plot point of the WWI bombardments you need to shift the setting in northern Italy since that's where most bombs dropped during the Great War (from Conte Volpe's leaflet I think it's implied that we're in provincia di Alessandria, since the next stop is Livorno and they're certainly not at sea). Given that, from a localisation perspective, I wonder about the choice of keeping the Tuscanian vernacular in the dub (which would otherwise be weird for Italian viewers, to whom Pinocchio has a very specific regional connotation) while the protagonist yodels and skips around with clogs?

Should they have gone with a more "neutral italian" dubbing, since this is a story being told by someone outside of the culture to an audience that is also mostly outside?

Prima volta in anni che guardo un film doppiato in italiano perché se sento Pinocchio chiamare Geppetto qualcosa di diverso da "Babbo" mi parte un embolo

#do not want to address the elephant in the room but uuh#it is not escaping me that the other famous retelling of Pinocchio on an international stage (ehm* the Mouse *ehm*) ALSO shifts the setting#to the Alps rather than central Italy#which. again. italian people do not care about the Disney adaptation when there are a bunch of homemade movies#but. mmm. dunno can't help not feeling bitter about it? there's some stuff that gets lost in translation and translocation

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

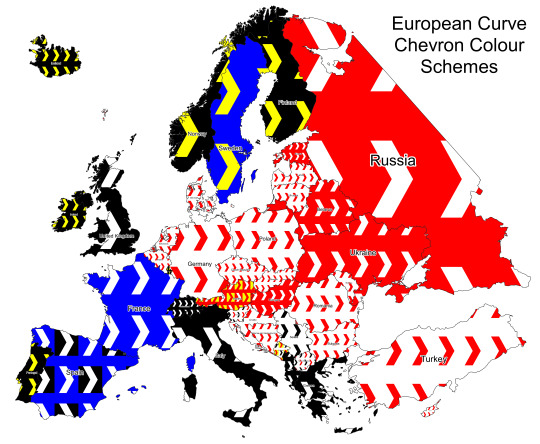

Map of European Road Curve Chevron Signs

by u/isaacSW

Not sure if something like this has been done before but I’ve put together a map showing the colour schemes used on the chevron signs used on road curves throughout Europe (this is the sort of thing I’m talking about). I think it could be quite powerful in some areas, like the Balkans and central Europe, where they are quite common and the colours vary a lot from country to country.

This won’t be 100% accurate, and I’m sure you will be able to find counterexamples, but I have checked multiple signs in each country and it appears to be a fairly reliable clue. If you do find anything I’ve missed, let me know and I will update the map and post the link below. Here is a list of observations I’ve made while making this map, with example locations.

Notes:

The white colour is often substituted for luminous green/yellow in high altitude/latitude areas (example). Austria and Montenegro have their yellow variants shown on the map as they appear to greatly outnumber the corresponding white variants. The yellow colour on south-facing signs will often fade to near-white.

Some countries will add a luminous yellow outline to the signs rather than replacing the white (generally in high altitude/latitude areas). Some countries that do this are: Italy, Romania, Hungary, Russia, the UK, Belgium and Turkey.

Most countries will also have a long variant of the curve chevron sign (example). This should be the same colour scheme as the single-chevron signs, however it may be less obvious which is the ‘background’ and which is the ‘chevron’ colour.

Notable Countries:

Spain uses both the white-on-blue and white-on-black interchangeably. It is always the long variant (as far as I can tell), and the colour distribution does not seem to vary by geographic location. (blue example, black example)

Montenegro uses the red-on-yellow (example) and black-on-white (example) signs in roughly equal amounts (no real correlation with geography), with some lower areas near the coast using the red-on-white variant (example), however this is much less common than the red-on-yellow.

Slovenia uses mainly the black-on-white variant (example), however areas around Ljubljana and Koper (and maybe other areas) use the red-on-white variant (example).

Austria uses the red-on-yellow and white-on-red frequently in the upland areas. They are also often found with a pattern of a few reds then a yellow (example), which appears to be unique to the country. The lowland areas may also use the red-on-white variant.

The Netherlands often uses a miniature variant (example)

Russia and Ukraine use the long variant quite frequently, which also sometimes appears in the Baltics (possibly other ex-soviet regions too). The single variant also has more background colour visible compared to other countries (example). It also often has a white outline.

North Macedonia has red-on-white and black-on-white variants, though the black ones appear to be less common.

Frequency:

Countries that use a lot of roadside bollards tend to use fewer curve chevron signs.

Rare in Andorra, Finland and Denmark.

Fairly uncommon in: Baltics, Sweden, Iceland, Russia, Ukraine, Belgium, Netherlands, Germany and Luxembourg.

Fairly common in: Norway, UK/Ireland, Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, Switzerland, Hungary, Romania, Serbia, Czechia, Slovakia, Poland, and flatter areas of the Balkans.

Very common in: the Austrian Alps, mountainous areas of the Balkans, and Turkey.

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1387 03 11 Castagnaro, the Veronese breakthrough - Graham Turner

As the Veronese carry the ditch, the Paduan line starts to crack in the face of superior numbers. The scene depicts this dramatic moment of the battle. Ostasio da Polenta, leads the Veronese assault, the crested great-helm he wears over a bascinet a visible rallying point for his men. At his left are the German knight Georg von Schonberg and the Veronese Ugolino dal Verme. Schonberg is clad in a Central-European coat with long, loose sleeves and wears a bascinet with a klappvisor, somewhat demodee in Italy but still popular north of the Alps. Dal Verme's armour is a combination of up-to-date and earlier pieces, his family's fortune taking-off once again after years of exile from Verona. Coming up behind Polenta is the feudal lord Antonio da Castelbarco leading a group of his own retainers, the latter's mixture of older and newer equipment denoting different degrees of individual wealth. The banner of Giovanni degli Ordelaffi indicates that the Veronese left flank has by now moved towards the centre of the line, adding weight to the attempted breakthrough.

On the Paduan side, Francesco Novello da Carrara desperately tries to stem the mounting Veronese tide. As would be expected from a member of one of the most powerful Italian families, his apparel is the best on the market. From contemporary sources we know he wore a crested bascinet rather than Polenta's great helm, but carries the same bouche style of shield, a shape that was becoming increasingly popular in Italy. At Francesco Novello's side a member of his household moves in to protect his lord, his role and position evident from the variant of the Carrara arms on his jupon. Also guarding Francesco Novello, this anonymous Paduan man-at-arms, whose state-of-the-art breastplate has caused him to forgo his jupon, although one could expect him to have some sort of field sign painted on his armour for the sake of recognition. The Paduan trumpeter sports the Carrara arms on the small flag hanging from his instrument, but otherwise wears normal civilian clothes.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Desert Fox: Separating the myth and the man of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel

Sweat saves blood, blood saves lives, and brains saves both.

- Field Marshal Erwin Rommel

War hero or Nazi villain? Field Marshal Erwin Rommel is, to this day, the subject of heated debate. He was the “Desert Fox,” revered by Allied Forces for his supposed chivalry, and allegedly implicated in the “Valkyrie” plot to assassinate Hitler.

But present day historians have increasingly come to re-examine the life and the legend of this most iconic of World War Two generals.

I first became interested in this question after reading Corelli Barnett’s magisterial account ‘The Desert Generals’ back when I was in Sandhurst. I read other World War Two books before then of course but it was only at Sandhurst did I first give serious consideration towards Rommel as ‘the Good German’ general. I read other books too like General Sir David Fraser’s ‘Knight’s Cross: a life of Field Marshal Rommel’ as a stand out one on military stuff but a very cursory examination of his early life and beliefs.

Rommel was a legend in the making.

Whichever side of the debate one falls on there is no doubt that Erwin Rommel, was one of the most celebrated and respected generals of the Second World War and indeed, some even say one of the greatest generals of all time. His prowess on the battlefield earned him more than a battlefield earned him the admiration of both his men and his enemies alike, with adversaries lining up to pay tribute to their greatest foe in the field.

“We have a very daring and skilful opponent against us, and, may I say across the havoc of war, a great general,” said no less than Winston Churchill himself of Rommel, just after the war ended in his book on the conflict, The Second World War.

When Churchill came under fire in the press for praising a man seen as a Nazi, he doubled down, commenting “He also deserves our respect because, although a loyal German soldier, he came to hate Hitler and all his works, and took part in the conspiracy to rescue Germany by displacing the maniac and tyrant.

For this, Rommel paid the forfeit of his life. In the sombre wars of modern democracy, chivalry finds no place… Still, I do not regret or retract the tribute I paid to Rommel, unfashionable though it was judged.”

Indeed, the extent to which Rommel was a Nazi is one of the great questions that has been asked since the war and one that is debated to this day. Rommel, while respected by those who fought him from afar as generals and indeed, thought of a genius to many of those who fought beneath him in the Wehrmacht, has often faced criticism of his tactics and his decision making, with some post-war writers holding him up as a man prone to erratic behaviour on the battlefield and a great sufferer from the stresses of the job.

“Rommel was jumpy, wanted to do everything at once, then lost interest. Rommel was my superior in command in Normandy. I cannot say Rommel wasn’t a good general. When successful, he was good; during reverses, he became depressed,” said Sepp Dietrich, who fought under Rommel in France and ended the war as the most senior figure in the Waffen-SS.

A similar sentiment was expressed by Luftwaffe field marshal Albert Kesselring, a contemporary of Rommel’s and an officer of similar rank, who later wrote: “He was the best leader of fast-moving troops but only up to army level. Above that level it was too much for him. Rommel was given too much responsibility. He was a good commander for a corps of army but he was too moody, too changeable. One moment he would be enthusiastic, next moment depressed.”

Who was this great man then? We know him today as a great tactician, a charismatic leader, a respected general and the last German participant in the so-called “clean war”. But how true are those assessments? Was the Desert Fox as chivalrous as his enemies thought him to be?

Rommel was far from just a Second World War hero – he distinguished himself in World War One too.

Rommel graduated from the military academy in Gdansk – then known as Danzig and an integral part of Germany – in 1912 and was immediately posted back to his home region of Baden-Württemberg.

When war broke out in 1914, Rommel was ready to face his first major conflict posting. As a battery commander within the 124th division of the German army, he would distinguish himself and gain his first recognition from the higher-ups.

Erwin saw his first action at the age of 23 on August 22, 1914, near the French town of Verdun. Rommel led his platoon into a French garrison, catching them by surprise and personally leading the charge ahead of the rest of his men, earning credits for bravery and ingenuity. He would be awarded the Iron Cross, Second Class, for his actions, a promotion to First Lieutenant and a transfer into the Royal Württemberg Mounted Battalion as a company – rather than platoon – commander.

Rommel would go on to fight in the German campaigns in Italy and Romania, with particular note being taken by the German Army hierarchy of his conduct in the Italian campaign. The Royal Württemberg Mounted Battalion fought at the Battle of Caporetto, the twelfth battle to be fought along the Isonzo River in modern-day Slovenia, and one that would go down as probably the largest military defeat in the history of Italy.

Rommel would play a central role, leading the Royal Württemberg, with just 150 men, to capture an estimated 9,000 Italians, complete with all their guns, for a cost of just 6 of his own men.

The young Rommel used the challenging, mountainous terrain of Caporetto – now known as Kobarid – to outflank the Italians and convince them that they were totally encircled by Germans, when in fact there was just one battalion. Fearing that they were surrounded, the Italians surrendered en masse and were surprised to find that so few men were able to capture them.

The efforts of the German Army to break into the Italian Front through the Slovenian Alps – at the time, part of Italy – were vital in furthering an advance towards Venice, though the Germans were eventually stopped and turned back.

Rommel was awarded the Pour Le Merite award by the Kaiser for his leadership at Caporetto, but also gained the respect and loyalty of his men, who were not only impressed by the way in which his tactics had won the battle, but also by the way that he had stood up to the German Army high command and argued for more and better food for his men. The legend of Rommel was growing apace.

Rommel was an effective teacher as well as a military leader.

It shouldn’t be too surprising that Rommel was a capable teacher: his father had been a headmaster, while the ability to communicate his ideas effectively in the field would lead to some of his most enduring military victories. There was no point coming up with a revolutionary tactic to win a battle if you couldn’t then inform and inspire your men well enough for them to then go and carry it out.

At the end of the First World War, Rommel was entering his late 20s and had already been widely feted for his military prowess. While it might have seemed a little dull compared to the derring-do on the Isonzo, the role of the Royal Württenberg Mountain Battalion lay much closer to home, with German society slowly disintegrating into civil wars between, on the left, socialists who wanted Germany to undergo a revolution similar to that which had recently occurred in Russia, and on the right, groups such as the Freikorps, disgruntled ex-soldiers and nationalist, anti-communist paramilitaries that would go on to form the kernel of the Nazi Party.

Rommel, recently promoted again to the rank of Captain, was ordered to use his soldiers in a policing capacity, putting down insurrections all over southern Germany. It was during this period that he showed some of the sense of restraint that would distinguish his conduct in North Africa during World War Two, trying to avoid the use of force against crowds of civilians where possible.

After the Weimar Republic took hold, however, the country somewhat stabilised and Rommel found himself in Dresden, teaching new recruits. He had been promoted in turn to Major, then Lieutenant Colonel, placing him in the very highest echelons of the Treaty of Versailles-reduced German Army.

He was recognised as one of the prime instructors in that army and wrote a book, “Infantry Attacks”, that furthered his theories on warfare and explained his experiences in the Izonzo – it sold incredibly well and increased Rommel’s personal fame, as well as bringing him to the attention of Adolf Hitler, who was known to have read the book.

Rommel met Hitler in Goslar, Germany in 1934, while Rommel was posted as battalion commander. Hitler’s charisma and promises to reestablish Germany as a world power after the crippling results of World War I inspired Rommel to become a fervent supporter of the Nazi Party.

The two men had several encounters following this, and Rommel rose through the ranks on Hitler’s personal recommendation. But it was ultimately Hitler’s liking for Rommel’s book Infantry Attacks that led to his becoming the commander of Hitler’s personal guards during his tour of the Sudetenland.

By the 1930s with Hitler fully secured in power, the German Army, for whom Rommel worked, and the Nazi state were more and more inseparable. It would be this coming together that prompted a major dilemma for the career soldiers such as Rommel: did the duty lie to their country, and whoever might be governing it, or to the party, that was coming to define what that country was about?

Rommel was a committed Nazi and not the “decent face” of the German Army.

Rommel’s antagonism wasn’t so much against Nazism as it was towards the Nazis in leadership who led it. His committment to Nazism eroded as the war took a wrong turn and as Hitler increasingly became erratic in his military decision making that Rommel grew increasingly frustrated.

Just how much of a Nazi Rommel was is one of the biggest questions that is debated about him to this day. It is largely due to the Rommel myth that was perpetuated by the likes of Winston Churchill after the war that Rommel was taken by the victorious Allies as “the good Nazi”, or the honest general who happened to be being ordered about by the Nazis, merely a career soldier who followed orders and stayed out of politics.

Let’s put that one to bed, here and now. Rommel was an early adopter of the Nazi Party and a committed believer in the ideals of National Socialism, while also being an officer who regularly disobeyed orders – making both commonly held assumptions wrong.

That said, he is one of the few figures of that period who is still revered in Germany, who still has streets named after him and memorials in his honour. It seems that the myth persists in his homeland too, despite countless books and articles to the contrary.

One such author attempting to shake this idea from the public consciousness is Wolfgang Proske, a historian and history professor from Rommel’s hometown on Heidenheim, who has written 16 books about his town’s most famous son. “Rommel was a deeply convinced Nazi and, contrary to popular opinion, he was also an anti-Semite. It is not only the Germans who have fallen into the trap of believing that Rommel was chivalrous. The British have been convinced by these stories as well,” he told British newspaper The Independent in 2011 when a new memorial to the Field Marshal was unveiled.

“At the time when Rommel marched into Tripoli, more than a quarter of the city’s population were Jews,” Proske continued, “There is evidence which shows that Rommel forbad his troops to buy anything from Jewish traders. Later on, he used the Jews as slave laborers. Some of them were even used as so-called ‘mine dogs’ who were ordered to walk over minefields ahead of his advancing troops.”

While Rommel was never a member of the Nazi Party, it is widely known that Wehrmacht figures, particularly high-ranking ones such as Rommel, welcomed Hitler coming to power. Those, like Rommel, whose backgrounds had shut them off from the highest ranks of the Kaiser’s forces, saw the new government as one that would see them move to the top of the tree and as such were generally in favor of it.

Goebbels himself wrote in 1942, when Rommel was in the running for the role of Commander-in-Chief of the Wehrmacht, that the Field Marshal was ”ideologically sound, is not just sympathetic to the National Socialists. He is a National Socialist; he is a troop leader with a gift for improvisation, personally courageous and extraordinarily inventive. These are the kinds of soldiers we need.”

Rommel owes a large part of his fame to the fact that he made fools of opposing general - well almost (Patton would disagree).

Rommel’s prowess as a general is unquestioned. On the back of his heroics as a low-level officer in World War One added to by his role teaching at the forefront of modern military tactics, he was perfectly positioned to lead the Nazi war machine into the second conflict.

When the war began, he was leading Hitler’s personal protection battalion – so much for a man who kept a distance from the center of Nazi power – and thus was privy to the highest levels of discussions regarding tactics, particularly the way in which to use mechanized infantry such as tanks. After the early successes in Poland, Rommel moved with the front to France and commanded Panzer units, before distinguishing himself against the British at Arras and leading the drive towards Dunkirk.

With the British regrouping on the other side of the Channel after a crushing defeat – which, lest we forget, Dunkirk was – the focus turned to North Africa, where Rommel would lead the newly-established Afrika Korps. He was the superstar of the German Army, a reputation largely built on his ability to vanquish the British, whom he would now face again in the desert. It was at this time that his nickname, The Desert Fox, was coined by the British press, who sought to create a figure against which the war could be fought.

The legacy of Rommel as the acceptable Nazi could be seen to stem from this point when the media in Britain saw fit to create a worthy adversary for their troops to combat. Rommel was thought to be an old-style soldier rather than an out-and-out Nazi: though we have seen that he was a Nazi, and he had arguably committed war crimes by summarily executing prisoners in France just weeks before.

Come the victory of the British at Tobruk and El Alamein, the British propaganda machine had even more than a noble adversary. They had a noble adversary against whom they had lost in Europe and then subsequently defeated: when the characters of the British side, Auchinleck and Montgomery, were spoken of, they needed someone of equal weight to make their victories seem even more heroic, a role that fit Rommel perfectly.

With morale at home low after the Dunkirk evacuation, the victories in North Africa were vital to keeping spirits up, and a glorious victory against an equally glorious enemy sounded even better. Churchill himself called Rommel an “extraordinary bold and clever opponent” and a “great field commander” in the House of Commons in 1942 – after he had just been defeated.

Rommel’s reputation for chivalry in North Africa might not just be down to his own intentions.

Of course, some aspects the Allied propaganda about Rommel – that he was a fair fighter, that he respected the ideals of chivalry when other Germans didn’t – were generally true.

It is undoubted that, by and large, Rommel adhered to the rules of war when plenty of Nazi generals didn’t, but it bears mentioning that the reason that so many German generals were so callous is that they were ordered to be like that. Orders within the Nazi war machine came down from high and were often brutal in their nature: summary execution of prisoners, rounding up of Jews and other minorities, scorched earth policies. That was just the orders aimed at enemies: often generals would be ordered to stand their ground to the death when all military logic told them to make a tactical retreat.

Rommel’s dedication to upholding the “war without hate” as he called the more traditional methods of war is up for debate, but certainly, he did take measure to negate the harsher aspects. That said, there are other factors that question whether his commitment to the “war without hate” was intentional, circumstantial or ideologically-driven.

When most German generals were likely to commit acts of ethnic cleansing, Rommel was not generally faced with the question. North Africa, where this reputation was developed, had hardly any Jews, for example, and other potential targets for Nazi aggression were protected by being citizens of Italy and Rommel was wary of standing on the toes of their allies. That said, many within the North African Jewish community are reported as having felt that they were spared from the horrors suffered by Jews in Europe by the actions of the Afrika Korps, led by Rommel.

It is also widely accepted that he refused to execute captured Jewish prisoners and hated the use of slave labour. As far as his own troops were concerned, Rommel repeatedly refused orders directly from Hitler. When, at the end of the second Battle of El Alamein, Hitler commanded him directly not to retreat and to show his soldiers “no other road than that to victory or death.”

Knowing that it was impossible for him to defeat the advancing British, who massively outnumbered his forces, Rommel chose to ignore the letter from the Fuhrer and fled all the way across North Africa to Tunisia rather than face death in the sand. While he was way too politically powerful to be censured by Hitler, actions such as this were contributory to a wider feeling among the Nazi hierarchy that Rommel was not one of them.

He was a PR superstar in Germany, but was both respected and later suspected by the Nazi leadership.

Rommel’s reputation within Germany might well have made him untouchable for the Nazi hierarchy, even when he did things that were in direct contradiction of the ideological and military strategy of the regime. They had invested so much time and so much weight in making him the poster boy of their propaganda regime that, when Rommel turned out to be less than what they had hoped for, they could not easily dispose of him.

On paper, he was the perfect fit for their media machine: he was an early adopter of Nazism, already a hero from the First World War and an excellent general, with victories aplenty. Moreover, they could cite the Allies reverence for him in their favor, and Rommel himself was comfortable in the spotlight and relished the attention.

Hitler was always wary of building up any one single figure too far – lest he be challenged himself – but Goebbels, the chief propagandist, knew an opportunity when he saw it and Rommel could not be passed up. As Rommel’s media image grew and grew, he became the darling of the public back home, but in the corridors of power in Berlin, there were plenty of higher-ups who were less convinced of his powers.

Even from the early days of the war in 1941, when Rommel was in France, some of those who fought alongside him were doubting just how effective he actually was a general. By the time that the war in North Africa had turned against him in 1943, the German furthest expansions were contracting: the Battle of Stalingrad had been lost in February and Rommel departed Tunisia in May.

It might have made sense if the Nazis had thought Rommel their best general, to send him to the Eastern Front where the war was being lost. Perhaps, too, the brutal nature of the war on the Ostfront was seen as beyond Rommel’s nature: this was not the time or place for “war without hate”, in the eyes of the Nazi leadership.

Instead, he was dispatched to Italy. As Italy fell, Rommel was demoted from the head of the campaign to second in command to Albert Kesselring, alongside whom he had served throughout the North Africa campaigns.

Later in France, Rommel was the man in charge of building the Atlantic Wall that would protect Nazi-occupied France from Allied invasion: though he had warned heavily that his experiences in North Africa had taught him that land and sea defences would be nothing if air supremacy allowed the Allies to destroy the Nazi army from above, Rommel was ignored.

After the defeat in North Africa, the retreat through Greece and Italy and the failure to stop the D-Day invasions, his reputation as a superstar general back home was in tatters.

Rommel’s reputation got a huge boost because of a 1951 film.

If Rommel’s reputation as a great leader was undermined by the catastrophic defeats on the African, Italian and Western Fronts in the last two years of the war, why was it that the so-called “Rommel Myth” was so pervasive after the war? The theories are numerous, but one major contributing factor must be the success of the 1951 film, The Desert Fox. Rommel was played by the iconic actor James Mason who won critical acclaim for his role.

Rommel was a well-known figure in Allied countries and in 1950, the first biography of the “good German” was released in the UK. Written by Desmond Young, a British brigadier-general who had himself been captured by Rommel during the war, “Rommel: The Desert Fox” was incredibly popular in Britain and cemented the position of the vanquished general as the acceptable enemy.

His later involvement in the 1944 plot against Hitler did a lot to wash Rommel of the stain of Nazism – conveniently forgetting the decade or so that he had spent close to the top of the regime – and his position as the general who was beaten “fair and square” endeared him to a British audience. After all, it’s much easier to build heroes of your own generals when they have beaten a general that you also respect.

The 1951 film of The Desert Fox further spread the myth and was widely popular in the UK. The narrative of Rommel, the good German, being defeated by the heroic British in the clean war in North Africa was a far more palatable one in the burgeoning Cold War than one that emphasised the horrible destruction that had come through the Soviet victory in the East.

There could be little appetite for a war with Russia when people were constantly being reminded of the horrific images that had emerged from the Eastern Front. Thus, the clean general of the fair fight in North Africa was an enticing idea.

The Germans, too, were all too pleased to go along with Rommel as their figurehead. Their army had been severely curtailed after their defeat, but there was a clamour to de-Nazify the Wehrmacht and remove the stigma from the German armed forces. The Bundeswehr, the new German army, was more palatable to a post-war world when it could be seen as the legacy of good soldiers lead by bad politicians rather than an integral and vital part of the Nazi war machine.

Thus, the idea of The Desert Fox was created and, to a large extent, still persists. He remains the only Nazi to be lionised within Germany: public squares and streets bear his name, as does the largest barracks of the Bundeswehr. Whether such a status is deserved, however, is still a question about which historians continue to argue.

During the first half of 2020 many countries have been reconsidering the roles of their historical figures - remembered in statue form - due to their controversial views or actions from today’s point of view. In Britain, France and Belgium, statues of figures associated with the colonial past have become the target of public criticism in some quarters. In the United States, not only statues of Confederate figures who defended slavery during the American Civil War were destroyed or even demolished, but also, for example, the discoverer of America, Christopher Columbus.

In Germany a similar process was also underway. The monument to the Wehrmacht Marshal Erwin Rommel in Heidenheim came under severe renewed scrutiny.

Germany's memorial to Field Marshal Erwin Rommel is perched on a hillside overlooking the middle-class town of Heidenheim an der Brenz where he was born 120 years ago. The words inscribed on the white limestone monument describe the legendary Second World War general as "chivalrous", "brave" and as a "victim of tyranny"

The monument, which was built in 1961 by the German Afrikakorps Association, aroused long-term controversy and in the past was repeatedly damaged by inscriptions that called Rommel a Nazi. In 2014, Heidenheim City Hall expressed its intention to contrast the monument with another memorial building. By 2020 those calls took on a greater momentum.

The German artist Rainer Jooss was brought in by the municipal authorities to re-interpret the existing monument without having to destroy it completely. Jooss took as his starting point to focus on other parts of Rommel’s legacy. It was little known that Rommel had large minefields laid during the campaign of German troops in North Africa during World War II. In Libya and Tunisia alone, at least 3,300 people have lost their legs and another 7,500 have been maimed since the statistics were kept in the 1980s. So Jooss designed black silhouette cut out of a maimed child victim of war to complement the monument.

“The monument does not represent the truth, but encourages us to look for it,” said Bernhard Ilg, Mayor of Baden-Württemberg, at the presentation of the monument’s design unveiling in July 2020. Jooss was more stoic. Joos believed it would be a mistake to remove the Rommel monument altogether,"If we let grass grow over it, that would mean the end of the important task of dealing with history.”

The artist behind the modification to the Heidenheim monument said his statue was purposefully made to look small next to the impressive limestone bloc."I wanted to confront the monumental (features) of the original memorial with the fragility of a land mine victim.” Jooss wanted and hoped that it was up to “the next generations to make a picture of themselves based on factual histography.”

Yet eminent historians have since dismissed the fresh silhouette plaque as a transparent attempt to avoid addressing the deep seated questions about Rommel. Indeed Rommel’s privileged position to being seen as the ideal role model for the Bundeswehr (the unified armed forces of Germany and their civil administration and procurement authorities). While recognising his great talents as a commander, they point out several problems: such as Rommel's involvement with a criminal regime and his political naivete. However, there are also many supporters of the continued commemoration of Rommel by the Bundeswehr, and there remains military buildings and streets named after him and portraits of him displayed.

The politician scientist Ralph Rotte called for his replacement with Manfred von Richthofen. Historian Cornelia Hecht opined that whatever judgement history will pass on Rommel – who was the idol of World War II as well as the integration figure of the post-war Republic – it was now the time in which the Bundeswehr should rely on its own history and tradition, and not any Wehrmacht commander. Jürgen Heiducoff, a retired Bundeswehr officer, had written that the maintenance of the Rommel barracks' names and the definition of Rommel as a German resistance fighter are capitulation before neo-Nazi tendencies. Heiducoff agreed with Bundeswehr generals that Rommel was one of the greatest strategists and tacticians, both in theory and practice, and a victim of contemporary jealous colleagues, but argued that such a talent for aggressive, destructive warfare was not a suitable model for the Bundeswehr, a primarily defensive army. Heiducoff criticised those Bundeswehr generals for pressuring the Federal Ministry of Defence into making decisions in favour of the man who they openly admire.

Rommel has had his supporters from this avalanche of revisionist criticism. Historian Michael Wolffsohn supported the Ministry of Defense's decision to continue recognition of Rommel, although he thought the focus should be put on the later stage of Rommel's life, when he began thinking more seriously about war and politics, and broke with the regime. Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (MDR) reported that, "Wolffsohn declares the Bundeswehr wants to have politically thoughtful, responsible officers from the beginning, thus a tradition of 'swashbuckler' and 'humane rogue' is not intended".

According to authors like Ulrich vom Hagen and Sandra Mass though, the Bundeswehr (as well as NATO) deliberately endorses the ideas of chivalrous warfare and apolitical soldiering associated with Rommel. At a German Ministry conference soliciting input on the matter, Dutch general Ton van Loon advised the German Ministry that, although there can be historical abuses hidden under the guise of military tradition, tradition is still essential for the esprit de corps, and part of that tradition should be the leadership and achievements of Rommel. Historian Christian Hartmann opined that not only Rommel's legacy was worthy of tradition but the Bundeswehr "urgently needs to become more Rommel".

There are other historians who have tried to take a middle path on the continued controversy of Rommel’s legacy. Historian Johannes Hürter believed that instead of being the symbol for an alternative Germany, Rommel should be the symbol for the willingness of the military elites to become instrumentalised by the Nazi authorities. As for whether he can be treated as a military role model, Hürter writes that each soldier can decide on that matter for themselves. Historian Ernst Piper argued that it was totally conceivable that the Resistance saw Rommel as someone with whom they could build a new Germany. According to Piper though, Rommel was a loyal national socialist without crime rather than a democrat, thus unsuitable to hold a central place among role models, although he should be integrated as a major military leader.

Whether one is for and against Rommel such debates take place because he is dead in conveniently ambiguous circumstances.

Recovering from skull fractures in hospital, he missed the main event - the 20 July Bomb Plot 1944 - insitigated by other senior German army officers. Hitler survived the blast, and immediately set about executing the plotters.

While Rommel had lots of contact with many key conspirators and was generally aware of the movement(s) to assassinate Hitler, there is no direct evidence that he knew about the July 20th plot in advance, let alone was involved in any detailed planning. Several conspirators allegedly confessed during interrogation that he was involved and, like Speer, his name was found on Goerdeler’s list of possible participants in a new German government.

Rommel was listed among various possibilities for Reich President. Unfortunately for him, there was no question mark or other notation, as in Speer’s case, which indicated that he was unaware of the designation.

He maintained his innocence when confronted by General Burgdorff on the day he died and also told his wife and son that he had played no part in the events of July 20th. But ultimately, there’s no way to know what he was or was not aware of. He took that with him to the grave.

The list of members of the 20 July plot doesn´t name Rommel as part of the attempt to kill Adolf Hitler. But: Rommel was blamed of having known of plans to do so. So he was forced to commit suicide.

On 19 th October 1944 Rommel met two german generals at his home. They showed him pretended evidence about his paticipation in “operation valkyrie”, which he denied to be true. They accompanied him away from his home, where he swallowed a capsule filled with potassium cyanide and died. The two generals Wilhelm Burgdorf and Ernst Maisel , members of german court of military honour, who had handed over the capsule to Rommel, drove back to his home and contended that Rommel had died because of ramifications of an injury he received on 17th of July during an allied bombardement.

Given a choice between a trial, involving his disgrace, execution and his family’s impoverishment - and suicide - he chose the latter.

The story given to the public was that he’d died of wounds sustained in the air attack. He was named a “german hero”, was “honoured” with a state funeral an d buried in Herrlingen, Germany.

Had he lived who knows what his real fate might have been at the hands of the Allies. At the main Nuremberg trials, the two army generals prosecuted were Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel and General Alfred Jodl. Both were accused of conspiracy to commit crimes against peace; planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression; war crimes; and crimes against humanity. Both were convicted on all four charges and hanged.

The principal charge against Keitel was the infamous 13 May 1941 Barbarossa Decree, which condemned captured prisoners and ensured a high level of brutality by German soldiers against Soviet civilians. Jodl was the author of the Commando decree – ordering that any Allied commandos encountered in Europe and Africa should be killed immediately without trial, even if in proper uniforms or if they attempted to surrender.

General Heinz Guderian is an example of a prominent German general who did survive the war but was not prosecuted for war crimes.

Another prominent example is Field Marshall Kesselring, who had commanded the defence of Italy after the Allies invaded. Kesselring was not prosecuted at Nuremburg, but did face a British military court in Italy. The Moscow declaration of October 1943 had stated that those accused of war crimes would be prosecuted in the country where they had committed their crimes. Although the trial was conducted in Italy, Italian judges did not participate as Italy was not considered an ally. Kesselring was prosecuted for the shooting of hundreds of Italian prisoners in retaliation for attacks on German soldiers. Kesselring was found guilty and condemned to death. British General Alexander, who had run the Italian campaign, and Winston Churchill pleaded for the sentence to be commuted - which it was. Kesselring was released in 1952 and lived until 1970.

By comparison Rommel was never accused of issuing similar decrees. Many felt that he was an honourable soldier. Nor was he ever accused of shooting prisoners in the way Kesselring was. Rommel’s military reputation is that of a highly professional soldier who carried out his duties according to a military code of ethics. His record is untainted by atrocities or unsavoury tactics against the enemy or civilian populations. He tended to live a charmed life early in the war.

Had he lived one can only speculate as to his fate and his legacy. Speculation regarding a possible role for him in the rebuilding of German forces for NATO, had he survived, is unrealistic. Rommel was never a strategically-minded commander. Indeed it is well known that Quartermasters hated him for his habit of outrunning his supplies on the battlefield.

The likelihood is he might well have been allowed to live without any kind of Allied retribution for war crimes as he was never guilty of any such departures from a strict military code of behaviour. But in trial - he would surely would have been put on trial even if he would be found not guilty - the messy details of his involvement with the Nazi regime would come to light. It would show that Rommel certainly benefited from the regime he served, and I think would have been considered guilty by association, even if his enthusiasm for Hitler waned in his final days.

Post-war, it would not have surprised me at all if the Allies had sought to build a West German government around Rommel. Staunchly anti-Communist, he nevertheless was seen widely as honourable and pro-West. But what role he would have been given - or what role the allies might have been able to make palatable to a war ravaged population - can only be speculated.

I suspect he would have served in some official capacity within the Bundeswehr before retiring to write his highly expected memoirs. It’s telling that Rommel’s chief of staff, Hans Speidel, drove the creation of the Bundeswehr and was the first to be named a generaloberst in that force. Later he was Supreme Commander of all NATO ground forces in Central Europe (which was almost all of it). It’s an intriguiing thought what Rommel might have played in a post-war Cold War Germany and Europe. Speidel and Rommel were inseparable and cut from the same bolt of cloth. Indeed it was Hans Speidel, who had been involved in the July 20 plot, wrote after the war that Rommel was a member of the resistance, (for which there is no evidence) that contributed towards Rommel and ‘The Good German’ Myth.

Given all that was “overlooked” by both the Allies and the German people after World War Two. There’s no logical reason to think that Rommel would not have been as honoured, if not more so, after the war. After all, one of the main Bundeswehr barracks continues to be named after him in 1965.

To me he was a great general rightly lauded by his peers and military historians - but not the best. Rommel was a highly competent tactical commander, but there were many such commanders in the Wehrmacht. His prominence is due to a number of things. Firstly, he was always Hitler favourite; secondly Goebbels played him up in his propaganda; and thirdly he fought the British and Americans and thus received much more attention in the Western press and historians after the War than the German commanders fighting the Soviets.

Indeed an argument can be made that by fighting in the Western Desert in a sector that the British had logistical and material superiority (and thus difficult to defeat), Rommel essentially taught the British and the Americans Blitzkrieg tactics - essentially modern warfare. His very inflated legacy saved the British from admitting their military performance in North Africa was abysmal until the Axis forces overextended their supply lines and the American supply of goods was able to compensate for substandard British equipment.

It’s also forgotten that Rommel also oversaw the building of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall which was essentially a fiction when he took over. Immense resources were poured into the project. The impact was to delay the Anglo-Americn invasion about 5 hours and only on one beach (Omaha).

And no matter how humane and honourable he was, Rommel was ultimately a weak man who chose to look away when it was convenient to his career to do so. Indeed I agree with many historians today that he was primarily bent on serving Hitler to advance his career. He was a man who believed he was serving a king and realises too late that he was a devil. I have little doubt that he was conflicted by that especially as it grew during the seven months of his life leading up to his death. Perhaps the best tactical military manoeuvre he made was to take the poison forced upon him and thereby save his family but also secure his legacy, even if that legacy remains mostly intact if a little more tarnished to this day.

#rommel#nazism#nazi#german history#war#second world war#battle#soldier#general#erwin rommel#allies#germany#afrikacorps#statues#culture#society#history#military#military history

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading a thread about “Who is the stranger you saw only once but still think about sometimes?” and it’s fucking me up and has got me thinking...

The woman about my age (in 2004; 22) who I saw crying silently on the London Underground and I didn’t say anything to (and now wish I had). That James Blunt song “You’re Beautiful” got popular the next year and it reminded me of her every time it came on the radio.

The Chinese merchant mariner and his wife who I met on the train to Venice (Italy) who was worried about getting off at the correct stop (we all helped with that) and who let me practice my (very bad) Mandarin with him for a minute. I remember how he smiled and laughed, but was so patient with me.

The university student from Bologna who saw me sitting on a wall, sketching some of the buildings in Perugia who asked if I was an artist. I said no; wish I’d said yes.

The woman who called the bookstore I was working in desperate to figure out how to get herself and her mother on the Dr. Phil show so they could work out their issues (she kept me on the phone for at least an hour).

The woman with the amazing bottle-green eyes I saw once while working at the same bookstore.

The woman with the blazing orange hair (dreads, I think?) who I saw in Grand Central Station station and I swear I saw her in a dream the night before.

The homeless man in Zurich with his pack of dogs who kept right around him (and one street over were watches being sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars).

The whole crowd of Australian students talking to a whole crowd of Japanese students, with the Japanese student’s teacher translating, all of which was going on during a Thames ferry ride.

The random student who helped me find the cemetery in Zurich so I could visit James Joyce’s grave.

The two guys some classmates and I met when we (randomly and unexpectedly) went to see John Paul II do the Stations of the Cross. They spoke Spanish, we spoke English, but we had enough French between us to get along.

The girl who was the British clone of my college roommate who I saw in a hostel in St. Gallen (CH). Right down to mannerisms and hair color. Just like her--except British rather than Texan. (Shout out to the cows hanging out around that hostel.)

The MP who was handing out Pro-EU lapel pins to all the tourists regardless of nationality in Westminster--a good 15 years before Brexit was a real Thing. I still have that pin.

The guy selling panini on the train out of Florence. He had the strangest kind of Donald Duck robot voice as he walked the aisles saying “Panini. Panini. Panini.”

This one is cheating because I saw him twice, but I met a man from out on the coast of NC who was (by his own admission) part black and part Native American. He had the palest blue eyes I have ever seen and six fingers on each hand--which, he said, meant he should be the leader of his tribe. I was working at the genealogy library at the time and helped him find census records.

And, last but not least, the tabby cat I met in the Swiss Alps, just above Gimmelwald, who led me back down to Walter’s Hotel when I was a bit lost. Yes, the Rescue Cats of Gimmelwald are real.

A lot of these, ironically, come from that really shitty backpacking trip I took in 2004. Huh. I’ve got more, I’m sure. They spring up unbidden.

Anyway, feel free to add on your own, if you’d like.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shelling out Can Be Lucrative With Real Estate in Slovenia

Very few ındividuals are aware that investments in Slovenia are much more cost-effective, compared to investing the same amount in the United States or the United Kingdom. Slovenia property investments have potential for higher returns on your hard-earned lifetime savings than other markets. With the guidance of any professional experienced in Slovenian markets, you would be able to experience the opportunities existing in Slovenia for maximizing your rewards. When you mention property investment in overseas markets, the original reception is usually skeptical. When you take this topic farther by saying that investments in Slovenia are more worthwhile compared to the property market in California, you are most likely in order to shock most of the people. For example , if you say that you had bought the housing property in Slovenia for $500, 000, the comments would most probably be, "Slovenia? Is it a place or a country? I have never heard of it", "Don't you believe buying a house in Slovenia is a risky affair? ", and "I am convinced that you are not acting in a intelligent manner. " Some of the comments could be even harsher. On the other hand, if you state that you have invested $1, 000, 000 in a waterfront property in a remote area in Los angeles, people would unanimously agree that you had made a great option. In reality, which of the above two investments is riskier? How to decide whether property investment in new international markets like Slovenia is riskier or safer as compared with an investment in native California? Slovenia Economy It will be true that many real estate investors in various countries had neither of the two heard of Slovenia or the opportunities that this little recognized neighbor of Italy offers in the property field. Slovenia joined the European Union in 2004 and recently adopted dollar as its currency. It would be interesting to know that Slovenia possesses the highest per capita GDP in the Central The world region, according to the CIA World Factbook. Further, the national infrastructure of this country is one of the best and the workforce is also rather well-educated. Like most global countries, properties appreciated significantly in between 2004 and 2007. However , the worldwide recession following the bursting of the real estate bubble in the middle of 2008 in the United States afflicted Slovenia also to a certain extent. Still, the country had managed to recover and is now on the growth path again. The actual GDP growth rate is around 5%, the highest for any new member state of the European Union. Slovenia Real Estate Market Data released by your Statistical Office of Republic of Slovenia (SORS) talk about that property values rose at an annual common of 1. 3% between 2004 and 2007 but been reduced after that. During the first quarter of 2009, the prices in houses on sale in second-hand market dropped by 7% from the same period in 2008, while the fall for real terms was at 8. 7%. The real residence prices in the capital city of Ljubljana collapsed through 8% in nominal terms and 9. 6% during real terms, while the decline was 6. 8% throughout nominal terms and 8. 5% in real words and phrases in the rest of the country during the first quarter of 09. This had brought down property prices, which is an excellent negative point but a positive factor. You could buy components at lower rates right now. Investment Opportunities in Slovenian Properties The biggest assets of Slovenia are its valleys blooming with vineyards, the breathtaking coastlines, the arctic peaks of Alps and the rolling hills, the numerous waterways, and beautiful waterfalls. These features had made Slovenia a major tourist attraction, with possibilities for rental real estate thriving financially. At the same time, the slump in property character and the possibility of significant appreciation in this decade make this place a prime location for real estate investment. After the setback regarding 2008, the Slovenian economy had been recovering at a faster rate compared with several other European and North American nations. A recent survey voted Slovenia among the top 10 countries offering best opportunities through real estate investment. According to the survey, the growth rate of place values in Slovenia are forecast to increase at the astonishing rate of 284% on an average, between 2010 and 2020. The annual rate of real estate rate growth is estimated at 30% at present. As such, expenditure of money in real estate of Slovenia is considered as a long-term, reliable and solid proposition. Do you know that you would be able to buy a very few hectares of prime land covered with vineyards as well as having a medium-sized 2-bedroom house for a low price of 70, 000 euros or about $100, 000? The helpful fact is that nearly 40% of Slovenia has area covered with vineyards and it is a major wine-producing nation. Sometimes the properties in major cities of Slovenia, which includes Ljubljana and Maribor cost only around 1, 500 to 3, 000 euros or $1, 800 to make sure you $3, 600 per square meter. Procedures of Investment decision in Slovenia Real Estate Apart from the several registered real estate providers in Slovenia, the local laws explicitly permit people out of your United States and European Union to buy properties in Slovenia with very little restriction. It would take about a month to complete all the thank you's required to buy a property. With certain stipulations, you could also utilize financing and mortgaging options but it is advisable for you to finance your purchases out of your own resources, if you want to capitalize on the returns on your investment. Conclusion It is obvious which a property investment in Slovenia is likely to be more profitable in the form of long-term venture when compared to the same amount being invested in the usa or other countries in the European Union, where the economic development rate is still sluggish. The present growth of Slovenia offers better returns in this decade than any real estate investment on these countries. As such, it could be safely concluded that your investment decision in Slovenian real estate would prove to be more profitable than a similar investment in several other countries right now and much much less riskier.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Istria Croatia

It was Harvest time, when I was invited to join dear friends and excellent winemakers from Friuli, the Butussi family, on a visit to some family in Istria.. Istria forms the western-most peninsula of Croatia. We started off in an area that is so often compared to Tuscany, Momjan and its soft rolling hills, Cypress trees and gorgeous oak forests are certainly reminiscent of the Tuscany I know and love. Istria is famed for it’s tourism offer with charming seaside towns and hilltop villages, the region produces notable wines, olive oils and truffles along with abundant fresh seafood and I was lucky enough to taste all of these on day one. The area is also famed for its outdoor adventures, sailing, paragliding, mountain-biking which draws many visitors to this beautiful region.

Some Geography

The geographical features of Istria include the Učka mountain ridge, which is the highest portion of the Ćićarija mountain range; the rivers Dragonja, Mirna, Pazinčica, and Raša; and the Lim bay and valley. Istria lies in three countries: Croatia, Slovenia and Italy. The largest portion (89%) lies in Croatia. "Croatian Istria" is divided into two counties, the larger being Istria County in western Croatia. Important towns in Istria County include Pula/Pola, Poreč/Parenzo, Rovinj/Rovigno, Pazin/Pisino, Labin/Albona, Umag/Umago, Motovun/Montona, Buzet/Pinguente, and Buje/Buie. Smaller towns in Istria County include Višnjan, Roč, and Hum.

The northwestern part of Istria lies in Slovenia: it is known as Slovenia Istria and includes the coastal municipalities of Piran/Pirano, Izola/Isolaand Koper/Capodistria, and the Karstic municipality.

North of Slovenian Istria, there is a tiny portion of the peninsula that lies in Italy, This smallest portion of Istria consists of the comunesof Muggia and San Dorligo della Valle, with Santa Croce (Trieste) lying farthest to the north.

Central Istria (Pazin) has a continental climate

The northern (Slovenian and Italian) coast of Istria (Ankaran, Koper, Izola, Muggia) has a sub-Mediterranean climate.

The western and southern coast (Piran, Portorož, Novigrad, Rovinj, Pula) has a mediterranean climate

The eastern coast (Rabac, Labin, Opatija) has a sub-Mediterranean climate with oceanic influences.

The warmest places are Pula and Rovinj while the coldest is Pazin

Precipitation is moderate, with between 640 and 1,020 mm (25 and 40 in) falling in the coastal areas, and up to 1,500 mm (60 in) in the hills.

Winemaking

The four princes of Istrian wine are:

Teran a tannic, robust red with high acidity that has surprising complexity.

Borgonja

The ancient grape famed beyond Croatian borders, Malvazija ,which Istria is justifiably proud of. Grown here for centuries, its pale golden yellow colour with elderflower on the nose and a refreshing aroma.

Then the sweet Muscat from Momjan used for those dessert wines.

Most of the larger estates also cultivate international varieties such as Chardonnay Cabernet Sauvignon, merlot and Cabernet Franc for their wine range.

Our first stop was at Winemakers the Markezic family, who have been making unique terroir wines here since 1891, at Kabola Winery at Momjan on the Istrian wine route. Their property is a dream with ancient sprawling oaks around the property that stand guard over the traditional stone homestead, featuring an excellent cellar, the wine shop, tasting room, and a small museum dedicated to wine and wine making process. Rolling hills with vineyards 270m above sea level, nestled between indigenous forests.

Kabola Winery use amphorae buried underground for fermenting the Malvaziaj wine. The perfect combination of soil, climate and winemaking passion. Wonderful hospitality and there were so many amazing wines, from sparkling whites to muscley reds and right through to orange wines. I took away their excellent Amfora Malvazija 2009 wine. An excellent start to my trip in Istria.

The Momjan area makes for an excellent vantage point, on a clear day you can see both the glistening Adriatic Sea and the nearby alps. Cool nights and distant sea breezes make for some really delicious wines.

For Winery visits. Kanedolo 90, Momjan Buje t: +385 99 7207 106. [email protected] Closed on Sundays.

Close by is the charming winery-centered village of Brtonigla where I was staying over for a few days to explore the area. The local boutique hotel is of a high standard and all the winemakers have a relationship with it., making my job of tasting all the wines I wanted to experience but didn’t have time to visit, a lot easier.

Second visit was to Veralda a large modern winery with a substantial production, 33 hectares of vineyards and 5 hectates of olives located on the sunny hills of Buje, that is sent all over Croatia. Owned by the Visintin family the wines are well known in the region Here I tasted the whole range including the intense reds and was fortunate to be invited by the winemaker’s family to join them for a fresh truffle pasta freshly prepared with the fortunate pairing of the Veralda Rose which was a Decanter winner of which the winery was justifiably proud. Notable was the red Istrian made from the indigenous Istrian variety Refosco. Intense deep red colour with violet hints with raspberries, dark chocolate tobacco and cinnamon with a good expression of round, velvety tannins and long finish.

For Winery visits, Krsin 4, 52474 Brtoniglia

The Kozlovic winery located in stunning scenery in Buje with a unique architectural style to the modern winery, is a well-known winery with a tradition of making unique wines that stand for quality and the particular twist of Istrian wines. Later Over dinner, we sampled their flagship Malvazija and the excellent Teran. Paired with local fish and steak respectively.

For Winery visits: Vale Momjan 78 52460 Buje

Day three saw me visit a Long-standing family winefarm and winery, Cattunar near Brtoniglia . The Cattunar family have been flying the flag for Istrian wine where Father Franko and his son, with the hospitality assistance of their wives and extended family, run an excellent winery and offer regular tastings of their wines of autotonous grapes also and international varieties in an elevated position 5kms from the sea. I tasted my way through their wines looking out over the 56 hectares they farm carefully and with transparence. Istrian grapes like Malvazija, Teran, Muskat Momjanski and Muscat rose and also have substantial international vineyards.

Catunnar Wines.. here its hard to choose but certainly the standouts were the 4 soils Malvazija wines, each one grown on different parcels and vinified separately so the red soil, the white, the black, the grey each with a particular something, all so very drinkable, with a mineral quality and white flower finish but so fresh and vivid with layers of complexity.

Franko Cattunar also makes a lovely sparkling with his chardonnay which we started on and then lead up to the stunning multi-layered Teran with its nicely firm but integrated tannins and then Cabernet and also beautifully made Merlot, which was a surprise.

This visit to Cattunar was a highlight and as I sat later that evening in the sailboat dock in the nearby town of Novigrad with my feet in the gently lapping waves watching the sunset with an array of local wines and a few orange wines on offer, I knew I had only scratched the surface and that I would be back to explore more of this amazing place and its unique terroir wines.

For winery visits: Nova Vas 94 52474 Brtonigla [email protected]

Recommended visits.

Roxanich winery in Motovun are pioneers in the unfiltered, unadulterated long-macerated wine scene, Mladen Roxanich was producing natural local wines and orange wines long before it was trendy and each year at Raw in London I made sure to visit them. The Super Istrian 2009 is simply amazing.

Bruno Trapan is the new generation of winemakers in a style all their own, and making big waves along with Damjanic wines. Robi Damjanic near Porec is one of Istria’s youngest winemakers leading the charge into the future. Then Matosevic and his pioneering aging of Malvazija in acacia rather than oak. I can’t give an exhaustive list of the superstars and their stories, but these must be visited.

Dobravac Winery in the Rovinj region they produce a range of wines again from sparkling to dessert wines.

Near Umag in the north CUJ wines are produced by the Kraljevic family in the village of Farnazine.

Pilato’s winemaking tradition goes back to 1934 and the family winery in Istria is well known.

Degrassi produces some amazing wines too and I was surprised by the blend of Malvazija, chardonnay , sauvignon blanc and Viognier.

These are some, there are many others.

Novigrad, Rovinj and even the smaller towns all have numerous wine bars where you can stop over and taste the wines paired with local cold cuts and cheeses. There is also so much for the taster’s family to do, shopping in fascinating cobblestone towns and villages, layers and layers of interesting wine and food culture. On offer, is sailing, windsurfing, fishing, boating, and relaxing on beaches with refreshing and delicious chilled wines and seafood at hand. The third weekend in September is the festival of grapes in Buje.

The Istrian peninsula and those unicorn wines call me back.

Donna Amanda Jackson

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 13-14: Veneto>Trieste, Trieste>Senj

1,187 miles completed, 900 or so to go...two new countries 🇸🇮🇭🇷

Greetings from Senj, Croatia 😊

WHAT THE HELL do Croatians put in their Lemon Ice Tea? If I got 3 hours sleep last night I’d be exaggerating. But that it’s my go to energy drink for cycling here, it bodes well for an excellent ride 😊 The last time I felt this wired, well, too long. The likely explanation is the E numbers in the supposed healthier option of iced tea; equally, I’ve just cycled through a country, crossing it’s border silently, just a sign to say I was approaching Slovenia, and 250 metres later, boom: no control, cars, only a change of tarmac, once grey and flat, now pale and cracked.

I assumed the control point was further on up the mountain; surrounded by lush forests and rolling hills, void of life other than the apparent chorus of feathered natives. The sun hadn’t fully appeared and the weather could go either way, leaving me rather focused on the option of getting over the top and in to Croatia quickly. The final peak on the route is around 900m, but even my luggage felt lighter than any other climb I’d done this trip. Rolling on, I eventually hit a border control believing this was Slovenia, and for the first time, I was asked for my passport by a guard who came out and met me, and taught me that “Vala” was thank you. None the wiser that I had crossed into Croatia, my bike, Monkey II and it’s younger sibling, my frame bag, rolled on, blissfully alone. I’d realised that Spotify had moved into the next week and the deepest joy, a new Discover Weekly playlist. Artificial intelligence is very clever. In the tunes it presented me this week, first on the list, Crazy by Seal, Moving by Supergrass. I couldn’t be more elated on a ride than I felt in those two hours. I was in my own private heaven.

Not until I stopped for cappuccino at Cafe Bicicletta did I realise it was the Croatian border I crossed. I should have realised passing through Rejika, a crumbing, graffiti, once grand port city, interlaced with tram lines and an intricate network of roads. I looked very alien, and the city people looked very different to those I had seen in Trieste, just 20 miles ago and a country away. I didn’t know until I paid for my drinks that Croatia, whilst in the EU, has its own currency, the Kuna. I’d bought a roll, and at what I believed was €2.70 for a bit of bread, I was getting the “tourist” rate, the lady corrected me, taking my euro coins, all 50c, and putting me out of my confusion.

1000m climbed and 40 miles to go, the landscape again changed dramatically. Forested mountains to my left, the Adriatic and stark, barren, sometimes silhouetted landscapes to my right. It was beautiful, the route, challengingly hilly, and still the heavy clouds followed me, reminding me to keep pedalling or risk a soaking. I realised at this point my chain had developed a new rub in the big ring. It’s quite disheartening to hear...so small ring most of the remaining miles the answer.

I have a habit of unknowingly booking my bed at the highest point in a town. The accommodations in Senj was just this, with a 30% wrong turn to finish and 2200 climbing metres for the day, finally arrived, meeting the friendliest hosts of my trip, immaculate studio apartment, a freshly made tea, overlooking the ancient town and it’s proud castle. My goodness, I had arrived. It started to feel like the Odyssey had been to get to this Dalmatian Coastline. Inclement weather across Italy behind me, now I could breathe. If I hadn’t already felt challenged, it was now I was going to find out what I am made of.

Looking back at Italy, whilst I love Italy, I had not loved this particular visit. I’d got unlucky with the low weather front that arrived as I reached the Alps, and is still with me, but hopefully passing. I could have left later in the year. But if I felt the roads were busy now, in two months, they’d be so much worse.

I hit my low points in Italy (assuming there will be no more). I had to force a rest day after Venice, huddling down in a closed petrol station deciding how long I could survive as I chilled to the bone, sheltering from the freezing wind and wet to the core despite my wet weather gear. After finding the nearest hotel, and then waking the next day to the same torrential rain and 4 degrees, my heart was truly deflated. There was only one thing for it. Improvise. Adapt. Overcome. It was drastic, but the ridiculousness of the necessity to dress up as a cycling clown weirdly raises my spirits. The hotel owner, Rosa, and her husband, who called himself Leonardo (da Vinci) after helping to craft my stapled bin liner dress to go with my ingenious shower cap helmet/head saver, joined in laughing at my insistence at my intention to at least start again rather than get a train, or another friend’s suggestion, a ferry. All great options. Only to me that felt like failure. By 10 I was on the road with gritted teeth and an unbreaking resolve to make it to Trieste.

Looking left, I could see the Dolomites like a northern wall, covered in snow to the lower levels, a constant reminder of how messed up my trip would have been if I’d gone with any intial plan to ride through Trento. Surprisingly, the rain abated somewhat by the time I reached the Italian Rice Fields, wetlands with more water networks than I’ve ever seen and an abundance of wetland birds of all shapes and sizes. I had no nutrition for this 5 hour ride. I’d didn’t stop. And at 3:10pm, I arrived, victorious in the Italian Riviera town of Trieste. I really liked it here. My room was great, central, and vibrant atmosphere all around. I made my four yearly visit to McDonald’s to get a hot chocolate (amazing in Italy! Last time I was in McDonald’s was also a cycling trip in Italy in 2016, where starving and desperate after a long hard ride and all of Italy closed for lunch, I ordered 9 chicken nuggets, 6 chicken wings, a side salad, and fries, and ashamedly, enjoyed and demolished them all 😆). Knowing that a tough day lay ahead, I found my local bike mechanic to give my bike a mini service and at 10am I hit the road in search of new countries.

A few friends knowing what I’m doing, cycling from home to somewhere in Greece, ask am I having fun. This is my 6th cycling adventure, and in my head, an adventure won’t always be fun. Sometimes it won’t be fun at all, from beginning to end. Some adventures will be a combination of fun and he’ll, and the hope is that the trip will be more fun than arduous. The thing is, when it’s a good day, it’s amazing. There are incredible moments, desperate days, and varying degrees of pain and pleasure. But I think is good to take the risk and see what happens. At no point during or after an adventure have I said “I wish I hadn’t done it”. Even travelling alone and carting your own gear, riding 6 hours a day or more in all weather, you take yourself both mentally and physically to places otherwise unreachable, creating heightened memories and teaching you things about yourself, revealing your weaknesses and discovering strengths. I wasn’t sure I’d have a knee strong enough to make this trip. But here I am, over half way, excited, happy, weary but ready for another day. And when all is said and done, it’s still only a trip around a supermarket car park compared to those that climb mountains or sail across oceans. I have so many options to get home. On my hardest day this trip, I was sat within 5 miles of an international airport (Marco Polo), a train station (could have got me to Trieste) and a ferry terminal (anywhere between Trieste, Dalmatian Coastline and Athens).

I still have my cycling t shirt casual evening attire. I wear it now almost to excuse myself for my scruffy appearance. As if to say “no need to ask. Yup. Cyclist. Solo. Smelly. Weird”. I’ve also not managed to shed my wet weather gear yet but it’s coming. I can feel it! 😊

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The History and Meaning of Celtic Design & Art

by Crimsonwolf

Celtic art and culture date back as far as the 8th century B.C. Until recently, much was unknown about this fascinating culture. But thanks to recent archaeological excavation and findings, a greater understand of the Celtic people has been developed. Tribes were bound together by speech, customs, and religion, rather than a centralized government. Because of this, the art of the culture contained specific designs for spiritual meaning.

Celtic Knotwork is probably the best known style of Celtic design. The intertwined patterns of never-ending lines appealed to the Celts, symbolizing their ideas of eternal life and the intricate relationship of humanity with both the divine and the natural worlds.

Celtic denotes a people who are descended from one of the current seven Celtic "fringe" provinces of W. Europe- Brittany, Cornwall, Galicia, Ireland, Isle of Man, Scotland and Wales. The Celts did not live as a single organized nation, and are difficult to pin down to one specific way of life.

The Celts lived in the centuries around the birth of Christ . The oldest remnants of Celtic culture can be found close to Eastern France, N. Italy, S. Germany, Belgium, N. Switzerland, Austria, Turkey and Spain. The word CELT itself was derived from the name Keltoi, given by the ancient Greeks to all those who lived north of the Alps.

The Celts were not a people for writing things down. They passed down their traditions and their history by word of mouth and later in their artwork and symbolism. Celtic symbolism explains how they felt about the universe, life, death and the result of the changing seasons, so important to people who lived off the land. Celtic Symbolism reflects the human spirit, the ambitions and desires, aspirations and fears, and beliefs of the "otherworld" of fellow humans two thousand years ago.

Celtic Crosses

Symbolize the bridge to the "other world" or "worlds" and also to higher energy and knowledge. This is shown by the vertical axis which represents the celestial world, and the horizontal axis that symbolizes Earthly world. Celtic Crosses are also considered solar symbols and the source of light and ultimate energy. The first Celtic crosses had four equal points representing the four directions (north, south, east and west), and the four elements (earth. air, fire and water) and were enclosed by a circle that represented the sun. It may be noted that these early crosses were also used to mark holy spots in pre-Christian times and are often associated with the Tree of Life.

The Spiral

Symbolizes the continuity of life and spiritual growth. It is the constant flow of nature's processes moving outward then back inward as Heaven and Earth are joined. It is also about how death is a rebirth, whether of a human life, the seasons of the year, the astrological skies or anything in the natural or supernatural world The spiral was found on many Dolmans and gravesites. Its true meaning is not known for sure, but many of these symbols were found as far as Ireland and France. It is believed to represent the travel from the inner life to the outer soul or higher spirit forms; the concept of growth, expansion, and cosmic energy, depending on the culture in which it is used.

To the ancient inhabitants of Ireland, the spiral was used to represent their sun.The spiral is the cosmic symbol for the natural form of growth; a symbol of eternal life, reminding us of the flow and movement of the cosmos. The whorls are continuous creation and dissolution of the world; the passages between the spirals symbolized the divisions between life, death, and rebirth. Another idea states that the loosely wound anti-clockwise spiral represent the large summer sun and the tightly wound, clockwise spiral their shrinking winter sun. Also a double spiral is used to represent the equinoxes, when day and night are of equal length.

The Cauldron Symbol or the Three Spirals

Represent the Maiden, Mother and Crone aspect of the Goddess. The Cauldron is under the power of the Earth goddess Ceredwen the goddess of transformation. Transformation or Shapeshifting was an integral part of Celtic belief, this symbol is found all over Celtic artifacts. In the Cauldron, divine knowledge and inspiration are brewed.

Celtic Triangle Knot or Triquetra Knot