#battle of jutland

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Damage to Seydlitz from HMS Queen Mary's 13.5" in guns during the Battle of Jutland.

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

Battle of Jutland, German battlecruiser SMS Seydlitz engaged in a duel with British Admiral Beatty’s battlecruiser squadron, the ship already showing heavy battle damage, with her aft superfiring turret knocked out and all the the crew inside killed, and one of the wing turrets jammed and out of action.

Seydlitz would survive 21 large caliber hits, 2 medium caliber hits, and a torpedo hit, becoming one of the most damaged capital ships to ever survive combat.

Painting by Claus Bergen.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Image of Boy 1st Class Jack Cornwell, just 16, during the Battle of Jutland 31 May - 1 June 1916. While at his post on HMS Chester, the rest of Jack’s gun crew were slain, but Jack stayed at his post even though mortally wounded himself. Jack was awarded the Victoria Cross. The gun shield did not go all the way to the deck of the ship, so many crew could be cut down by shrapnel.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

HMS Princess Royal

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the asks : Which Nautical Novel Series do you prefer and reccomend? I'm looking fir book recs!

i dont have all too many fictional books about the navy to recommend, but John Fisher Memories was a really good read! i also want to get around to reading 20,000 leagues under the sea. Treasure Island was also a good book, and fun fact, Mr. Mercer canonically killed the main characters dad!! some non-fiction books about the navy are (with the links of were i got them on amazon);

Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea

Jutland: The Unfinished Battle: A Personal History of a Naval Controversy

Naval History of World War I

To Rule the Waves: How the British Navy Shaped the Modern World

Dreadnought: Britain, Germany, and the Coming of the Great War

edit: the John Fisher Memories is a non-fiction book!

#thechaosghost#history#navy#book recommendations#book recs#united kingdom#battle of jutland#ww1#british navy#german navy

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

06 June 2023

Wars of the Worlds

Canberra 06 June 2023

Note: The Author apologises for the lack of photography in this one. He will ensure that there are more in the next post, under pain of Field Punishment No. 3 (Being Made to Feel Really Bad about The Whole Thing.)

It’s nearly midnight, and I’m sitting in my room occupying that peculiar state where one is too tired to do much of substance, but too alert to sleep. I’d been reading the first volume of John C. McManus’ excellent series on the US Army in the Pacific War, but I’ve put that on hold - partially because I think it deserves more attention than I can give it before I travel, and partially because reading about Douglas MacArthur gives me a headache. I was scanning my books, seeing if there might be something I might read a chapter of section of, and my eyes fell on this.

This is the Imperial War Museum’s History of the First World War in 100 Objects by John Hughes-Wilson. I think it caught my eye because I’ll be there in two weeks. The book’s divided into six parts, so I thought I’d rifle through it and pick an object from each part that stood out particularly to me when I looked at the contents. It’s probably a strange way to do a book review, but to be fair I’m not aiming to review this. This, I think, is a bit more of a philosophical enterprise.

Part 1 is called Imperialism, Nationalism and the Road to War, and it’s fairly short, but it has some fairly choice artefacts. There’s George V’s crown, there’s a map of the European alliances, and there’s even the bloodstained tunic of Archduke Franz Ferdinand - but my eyes were drawn to a pen. This is on page 16, and it’s specifically ‘the pen that signed the Ulster Covenant.’ ‘This pen,’ the book tells us, ‘was used by Colonel Fred Crawford at the signing - reputedly in blood - of the Ulster Covenant, one of the totemic occasions in modern Irish history.’

The book highlights the pen (which forensic analysis has told us, disappointingly, was probably not dipped in blood) as an example of societal tension in both Britain and Ireland in the years leading up to the First World War. The chapter describes, for instance, industrial unrest being put down by troops in South Wales and Liverpool, the Suffragette movement, taxation issues created by welfare reform and the Anglo-German naval arms race, and principally the issue of Irish Home Rule. This brings us neatly back to the Ulster Covenant. It may surprise you, considering the hideous violence that overtook Ireland following the war, that Britain faced not a Catholic uprising in 1914, but a Protestant one. Unionists were alarmed at the Liberal government’s Home Rule Bill, which provided for a separate Irish parliament, and the prospect for the enfranchisement of the Catholic majority that it entailed. On Ulster Day (28 September) 1912, 80,000 Ulster Protestants gathered in Belfast to sign the Covenant, with Carson of course being the first to do so.

By March 1914, things had gotten, frankly, weird. The British Army faced the possibility of being sent in to crush the Ulster Volunteer Force, who were technically preparing to commit insurrection against the government so that they could remain attached to the government, ostensibly in support of an Irish Catholic majority, many of whom were anti-British republicans. To make things even more complicated, Anglo-Irish officers and Ulster sympathisers were overrepresented as officers in the British Army - Brigadier-General Hubert Gough (once again, remember that name) reported that the vast majority of his officers would refuse orders to enforce Home Rule. It was a mess from which it seemed Britain could not extract itself - and then Franz Ferdinand was shot, and the matter became moot as the First World War began.

So why the pen? I think there’s this idea that the First World War is the genesis of pretty much everything that happened afterwards. Yet here we can see the seeds of what would follow the war in Ireland being sown months and even years before the first shots were fired. The First World War didn’t create the Irish Civil War, or the Troubles, or anything like that. More broadly, it stands against the idea of a peaceful, golden Edwardian age that apparently existed before the war, or that there was a long uninterrupted peace between Waterloo and Sarajevo.

I’ll try to keep the other five a bit shorter.

Part 2 is The Shock of the New and there’s plenty of choices here, covering the course of the war through 1914. I was tempted to pick Admiral Souchon’s medals for their Gallipoli connection (I must remember to write a little about Souchon and Goeben before I get there) but my eyes were really caught by ‘the Imperial Eagle in Africa’ on page 88. This is a mosaic of the Imperial German eagle taken from Lome, the capital of German Togoland, by the British. In the late nineteenth century, Germany had joined the ‘Scramble for Africa,’ which had divided the continent between the various European powers. Like every other imperial power, their arrival caused great suffering to the people of their new colonies, most infamously the genocides they carried out against the Herero and Namaqua in Namibia. These Africans, so mistreated by their so-called superiors, were marched into battle when war broke out between Germany and Britain. Both sides used Africans as porters to carry supplies and as fighting troops - the Germans called them ‘askari.’ The East African Campaign, the longest of the African campaigns, cost 10,000 ‘British’ (mostly African), 2,000 ‘Germans’ (mostly African) and perhaps a hundred thousand civilians.

Naturally the vast majority of the historical attention on the African war goes to Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, the German commander in East Africa, who, in internet terminology, is often called a ‘badass.’ To be fair, he did apparently tell Adolf Hitler to go fuck himself (though he was still a bit of a nasty authoritarian himself.) Yet it does seem a bit unjust that the great ‘hero’ of this war was a white German man, and not one of the thousands and thousands of anonymous black dead.

The third part is Theatres of War, which roughly seems to cover 1915. I was drawn to an Italian trench helmet on page 112. Italy entered the war in May 1915, and primarily fought the Austro-Hungarians over the Alps. If there was anywhere on Earth more miserable than the Western Front, the Alpine Front might have been it. Here, men fought for mountaintops, caves and valleys, fighting not only the enemy but the elements. The eleven - eleven! - battles for the Isonzo River read like a parody of the supposed incompetence of leadership in the First World War. Luigi Cardorna - a general who combined pig-headed refusal to accept that constant assaults on the Isonzo were achieving nothing with a brutal, even cruel disciplinarian streak - often tops lists of the worst generals of the war.

(To give you an idea of what I mean by a disciplinarian streak, the man brought back the Roman ‘decimation,’ executing every tenth man in units that ‘weren’t performing well.’)

It’s the unit that this helmet belonged to that really caught my attention. An almost mediaeval affair, it was issued, often along with metal armour, to troops advancing ahead of the main assault force, tasked with cutting barbed wire. They called them Compagnie della morte - the Company of Death.

(As an aside, they tried to replicate this sort of thing in the video game Battlefield 1. It’s, uh… it’s not very realistic.)

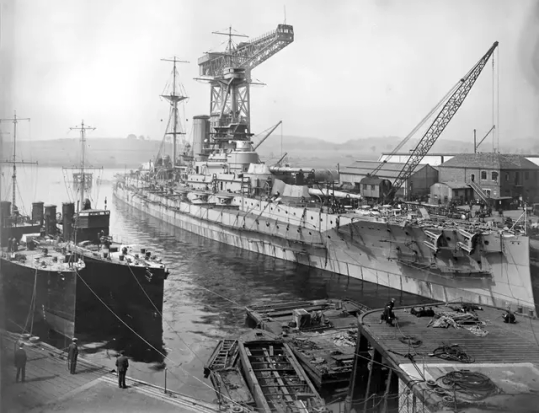

Part 4, Mud and Blood, roughly covers 1916-17. The first was Private William Short’s Brodie Helmet, but I’d already done a helmet. The second was a Simplex locomotive. The third, which I went with, was a recovered life buoy from the battlecruiser HMS Indefatigable, lost at the Battle of Jutland on 31 May 1916. I picked this because it’s an example of the war on the sea.

The battlecruiser was the brainchild of Admiral John ‘Jacky’ Fisher, the First Lord of the Admiralty in the 1900s, and the concept was sound. A battlecruiser is not a battleship. Battleships are meant to slug it out, and have the armour to match that purpose. Battlecruisers have battleship guns, but they don’t have battleship armour. The idea is that they can ‘outrun what they can’t outfight, and outfight what they can’t outrun’ - basically, they take on smaller ships and raid commerce.

The battlecruiser idea is not a bad idea, but it ceases to work if their commanders forget they’re not actually in a battleship and engage in a full-scale battle. This is what happened to the British battlecruisers at Jutland. Admiral David Beatty, commanding the Battlecruiser Fleet, engaged his German equivalents in the so-called ‘Run to the South.’ Indefatigable was hit within the first twenty minutes of the engagement by the German battlecruiser Von Der Tann, and was blown in half by an ammunition explosion. Three of her 1,019 crew survived. Shortly thereafter, the Queen Mary exploded, and Beatty’s own flagship Lion nearly met the same fate. Later in the day, the very unfortunately named Invincible also exploded.

To be fair to Beatty, these losses weren’t just because of the weaker battlecruiser armour - the battlecruiser squadrons had taken to leaving the blast doors to the ammunition stowage open to facilitate faster reloading - this meant that when the stowage went up, there was nothing to stop the force of the explosion. To be less fair to Beatty, these unsafe ammunition practices were being implemented under his watch, and he promptly followed the German battlecruisers - who were in fact withdrawing in the direction of their own battleships - right into the main German fleet, and promptly had to race very quickly back north again.

Part 5, From Near-Defeat to Victory, covers 1918. I chose to look at a ‘wreath for Saladin.’ This was sent by Kaiser Wilhelm II to Damascus in the Ottoman Empire in 1898, to be laid on the tomb of the great Islamic warrior Saladin, who fought against the Third Crusade. On the 1st of October 1918, the Allies entered Damascus. The 10th Light Horse got there first, but the official entry was performed by Sherif Feisal’s Arabs - and alongside them, one T. E. Lawrence, today better known as Lawrence of Arabia.

The history of the Arabs after 1918 was one of betrayal and disappointment. They had assisted the British in hopes of ejecting the Ottomans and creating a new, unified Arab state. Instead, under the terms of the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement, Arabia was to be split between French and British mandates. Feisal was made king of Iraq as a consolation, but the seeds of conflict that continue to affect the Middle East were sown here. It’s controversial how much Lawrence knew about this and how much he told to Feisel, though it does seem to me that he supported Feisel’s ambitions for an Arabic state. Ultimately, it was an example of how, for many peoples, the deposal of an old master simply cleared the way for a new one - Ottomans for Englishmen, Tsars for Bolsheviks, and in parts of the southwest Pacific, Germans for Australians.

This has taken a lot longer than I thought it would, but we’re up to the last part, A New European Landscape. I’ve picked Augustus Agar’s boat on page 410. Lieutenant Augustus Agar, Royal Navy, used this torpedo boat to sneak into a Bolshevik flotilla off Finland and sink the cruiser Oleg. I’ll be as a blunt as I can; I chose this because it demonstrates that the First World War did not neatly end on the 11th of November 1918. Conflict was continuing across Eastern Europe, the Balkans, Turkey, the Caucasus, Siberia and China - there’s probably places I’m forgetting. The fact of the matter is that ‘peace’ was really only for the west. The war didn’t ‘end’ so much as it eventually petered out.

Well, that’s about it. I’ve very much moved into the ‘tired enough to sleep’ zone, so I’ll leave that there. Sorry it’s a bit wordy, but I thought it may be of interest. And of course, if you want to look at this book yourself and see the objects I didn’t share, this all came front A History of the First World War in 100 Objects, by John Hughes-Wilson.

A quick acknowledgement to Drachinifel, whose videos on Jutland I used to reorientate myself to the battle. They can be found here and here.

#first world war#ireland#british army#africa#togoland#east african campaign#italian campaign#battle of jutland#palestine campaign#russian civil war

3 notes

·

View notes

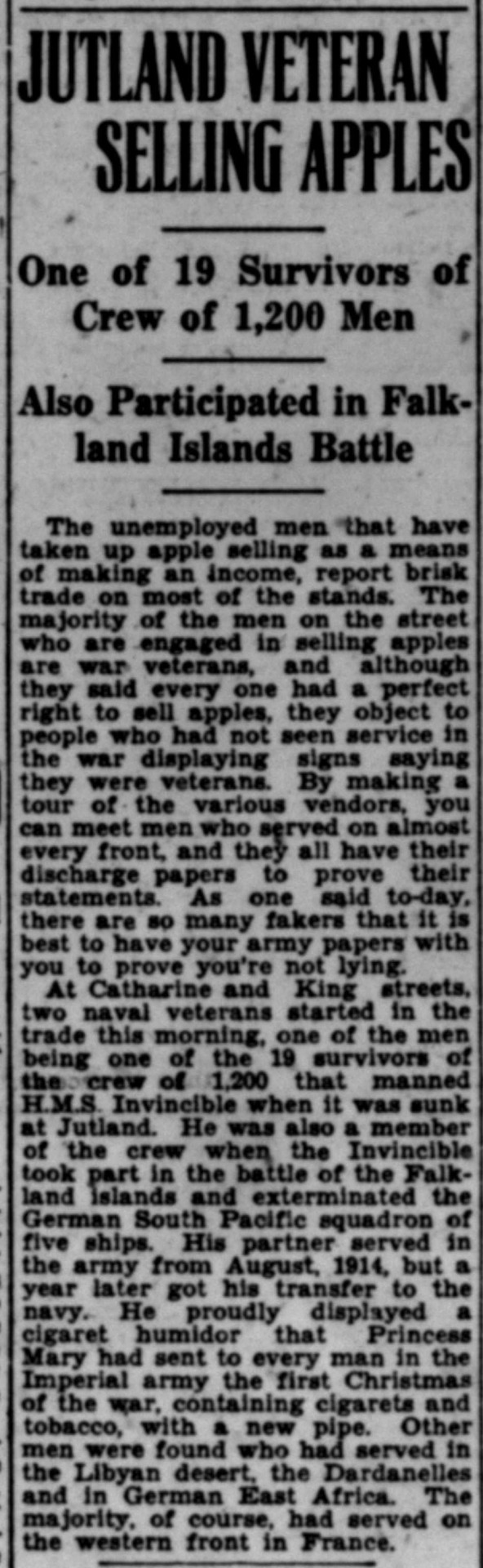

Photo

“JUTLAND VETERAN SELLING APPLES,” Hamilton Spectator. December 20, 1930. Page 7. --- One of 19 Survivors of Crew of 1,200 Men --- Also Participated in Falkland Islands Battle --- The unemployed men that have taken up apple selling as a means of making an income, report brisk trade on most of the stands. The majority of the men on the street who are engaged in selling apples are war veterans, and although they said every one had a perfect right to sell apples, they object to people who had not seen service in the war displaying signs saying they were veterans. By making a tour of the various vendors, you can meet men who served on almost every front, and they all have their discharge papers to prove their statements. As one said to-day. there are so many fakers that it is best to have your army papers with you to prove you're not lying.

At Catharine and King streets, two naval veterans started in the trade this morning, one of the men being one of the 19 survivors of the crew of 1.200 that manned H.M.S. Invincible when it was sunk at Jutland. He was also a member of the crew when the Invincible took part in the battle of the Falkland Islands and exterminated the German South Pacific squadron of five ships. His partner served in the army from August, 1914, but a year later got his transfer to the navy. He proudly displayed a cigaret humidor that Princess Mary had sent to every man in the Imperial army the first Christmas of the war, containing cigarets and tobacco, with a new pipe. Other men were found who had served in the Libyan desert, the Dardanelles and in German East Africa. The majority, of course, had served on the western front in France.

#hamilton#poverty work#poverty relief#unemployed veterans#canadian veterans#royal navy#old sailors#battle of jutland#battle of the falkland islands#world war 1#selling apples#great depression in canada

1 note

·

View note

Text

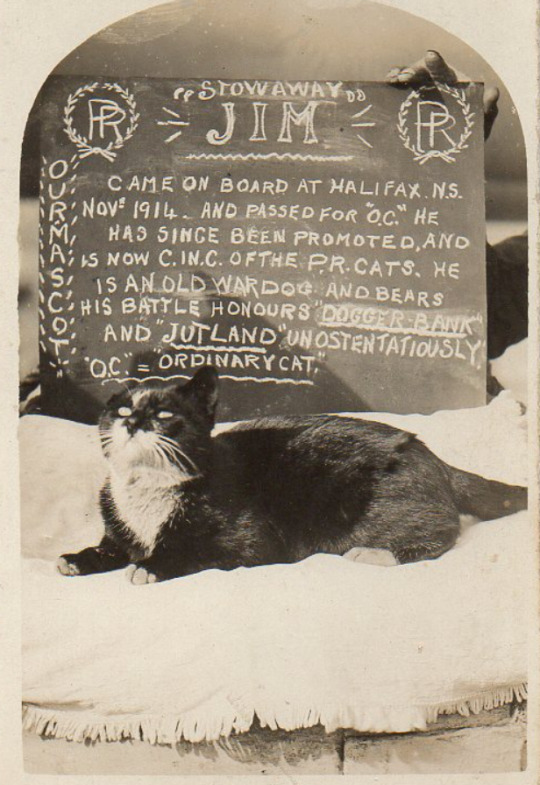

OC = Officer Cadet i.e. the lowest officer rank in the British Navy, and C in C = Commander in Chief, the admiral in charge. Stowaway Jim went a long way.

This is more likely the HMS Princess Royal, there was no HMS Prince Regent in WW1. Princess Royal didn't see any more fighting after Jutland so Jim was probably just fine.

Stowaway Jim - Ship's Cat of HMS Prince Regent, early 20th century

Came on board at Halifax N.S. November 1914 and passed for O.C. He has since been promoted, and is now C. in.C. of the P.R. Cats. He is an old wardog and bears his battle honours " Dogger Banks" and "Jutland" unostentatiously. O.C. = Ordinary Cat

#dogger bank and jutland being two of the largest battles of the war. as well as part of this punny nightmare.#no this isn't the first time ive added more info to a post about old ships cats.

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

SMS Seydlitz, post-Jutland, 1916. During the battle, Seydlitz took numerous large caliber hits up to 14 in, numerous secondary and one torpedo hit. It was a testament to her damage control efforts that she survived. Also a testament that British shells frequently did not work as designed otherwise she would not have survived.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finally, after two years lost in Maracaibo, I have recovered one of my favorite books, Jutlandia by Italian author Sergio Valzania, translated into Spanish by Juan Vivanco.

It’s a superb retelling of the Battle of Jutland, which has great focus on both sides, and comes with pretty great descriptions of the actions during that battle, if you can find an English version, which I’m sure has to exist, I can’t recommend you enough to get it!

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Battle of Jutland Ships

#BattleofJutland #warships #warpedia

Battle of Jutland – Warpedia The Battle of Jutland, fought between the British Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet and the Imperial German Navy’s High Seas Fleet during World War I, remains one of the most significant naval engagements in history. This epic confrontation, which took place from May 31 to June 1, 1916, off the coast of Denmark’s Jutland Peninsula, involved hundreds of warships and thousands…

View On WordPress

#battle of jutland ships#HMS Dreadnought#HMS LION#HMS Queen Mary#navy#warpedia#world war 1#worldwarI#ww1#WWi

1 note

·

View note

Text

Walter Yeo, a young sailor from Devon, became one of the first people in the world to undergo modern plastic surgery after suffering severe facial injuries during the Battle of Jutland in World War I. His injuries left him with inverted eyelids due to cordite burns. In a pioneering procedure led by surgeon Sir Harold Gillies, skin grafts from his chest were used to create new eyelids. Yeo went on to live a full life, running a pub in Plymouth and reaching the age of 70 before passing away in 1960.

254 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Great-Uncle with his gun crew, HMS Martial.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

SMS Seydlitz “B” Wing 28cm / 11" Gun Turret showing battle damage from a shell impact after the Battle of Jutland in 1916. German account from “B” turret; “In 'B' turret, there was a tremendous crash, smoke, dust, and general confusion. At the order "Clear the Turret" the turret crew rushed out, using even the traps for the empty cartridges. Then they fell in behind the turret. Compressed air from Number 3 boiler room cleared away the smoke and gas, and the turret commander went in again, followed by his men. A shell had hit the front plate and a splinter of armor had killed the right gunlayer. The turret missed no more than two or three salvoes”.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ya know, if I had a nickel for everytime I went on a rant that included the battle of Jutland under a swifties post I would have two nickels, which isn’t a lot.

3 notes

·

View notes