#this whole sequence is like our manifesto

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Sonadow fans when

#this whole sequence is like our manifesto#makes me crazy and ill everytime i remember it#sonic sounding more and more concerned...#shadow saying he cant hold this much longer and that he will fullfill maria's wish...#sonic BEGGING him to go back to the colony or else he will dissapear...#AND SHADOW GOES AND SAYS THE ULTIMATE LIFEFORM MIGHT BE SONIC#I dont even know what to say of sonic's line oh my god.#mandatory viewing please#i love them so mucb oh my god my god#also ignore them getting hit#EVERYONE IS WAITING FOR US BACK ON EARTH!#god. god#sonic#sonic the hedgehog#shadow the hedgehog#sonadow#sonic ramblings

880 notes

·

View notes

Text

Posthuman Review: Shaun Lawton & Nicholas Alexander Hayes

"In a few quick years, the first transhuman in vivo Minksian-Kurzweill clone emerges from its neonatal intensive care unit, eyes unblinking. Max quickly grows to establish the first CORE school (Consilience Of Recombinant Extropy) by the seasoned age of four. In the year 2020, eight-year-old Max engenders a transubstantiative doctrine reprising Heraclitus's ideas of flux. He publishes his manifesto >H by sending it back in time to his conception-year, where it now happens to appear on certain nodal points of the internet. Stars and their remnants, in the beginning, appear perfect with our skulls the shape of eggs while we listen to the music of the spheres. We never know we are dreaming, despite the uncanny appearance of our faces barely submerged below the surface of an image trapped on a screen, as if gazing at a host of cameras that were recording the whole scene and playing it back in overlapping sequences until rendered in 3D, a sort of holographic emergence as a film to show the whole fully recorded history of the human race intact in one performance taking hours to play out that tells the story of our pregalactic form expanding like a cell splitting into divisions congruent with the microchip cluster each acquires to their myriad snowflakes and fingerprints; no two are quite alike, this quality of uniqueness the most common attribute in the galaxy because it takes its shape from the constant force it has been from the beginning, a dorsal fin configuration pre-eminent to radial symmetry, subdivided from the pie & expanding in the recesses of our own mind at rates which we don’t share and we don't want to have to admit even to ourselves it could be the case but on the face of it our individuality evaporates along with the rest of the universe, siphoning itself back & forth both in and out of existence, in a blinking state of awakened beings cycled in an infinite figure eight Mobius strip, along the thermodynamic principle where the electromagnetic motors of creation pass along the triggering current arriving in its multiplicity of waves so here we are much further away from the start than we'd ever imagined before making it in a world on the verge of boiling over with accelerating change to the point it's quaking under this pretense we begin thinking about the stars & their remnants to which we end up belonging while the motion picture of our lives flashes inside our mind in an effortless gesture disarming the gravid affront with united civic resistance paving the way forward for the benefit of our progression into the distance only going to show which ends up being the case that it doesn't really matter so much as the belief we hold well and verily fixed foremost in our mind unravels before a hand to be woven in predetermined fashion foremost reveals the negative gravity bound pressure resistance capsule in the shape of a psychonautical skull transcript." - Shaun Lawton

Δ = (Σ(bug + defect + flaw + hitch + malfunction + mishap + problem + glitch + defeat + delay + difficulty + adversity + complication + crisis + deadlock + dilemma + gridlock + predict + meant + dire circumstance + hard ship + impasse + standoff + stand still + pickle + plight + condition + breakdown + trouble + anxiety + concern + danger + debacle + complication + hazard + catastrophe + changes + confrontation + disaster + calamity + emergency + failure + quandary + collapse + decline + breaks down + beating + annihilation + destruction + raw carnage + elimination + eradication + decimation + extinction + obsolescence + end of life + extermination + void + nullity + nonbeing + nothing + zero + ∅ + H in a few quick years + transhuman + Minksian-Kurzweill clone + neonatal intensive care unit + eyes unblinking + Max + CORE school + Consilience Of Recombinant Extropy + four + 2020 + eight-year-old Max + transubstantiative doctrine + Heraclitus's ideas of flux + manifesto + internet + STARS AND THEIR REMNANTS + beginning + skulls + shape of eggs + music of the spheres + dreaming + uncanny appearance + faces submerged + image trapped + screen + host of cameras + recording + overlapping sequences + 3D rendering + holographic emergence + fully recorded history + human race + pregalactic form + cell splitting + microchip cluster + snowflakes + fingerprints + uniqueness + galaxy + constant force + dorsal fin configuration + radial symmetry + mind + individuality + universe + existence + blinking state + awakened beings + infinite figure eight Mobius strip + thermodynamic principle + electromagnetic motors of creation + multiplicity of waves + accelerating change + quaking + stars & their remnants + motion picture of our lives + united civic resistance + progression + belief + fixed foremost + negative gravity bound pressure resistance capsule + psychonautical skull transcript by Shaun Lawton)

Explanation: The equation Δ represents the dynamic nature of life and the universe. It encompasses a wide range of elements, from challenges (bugs, glitches, difficulties, etc.) to unique qualities (uniqueness of snowflakes, fingerprints, etc.) to the constant changes in the cosmos. The equation also incorporates the concept of time travel and the emergence of transhuman technology.

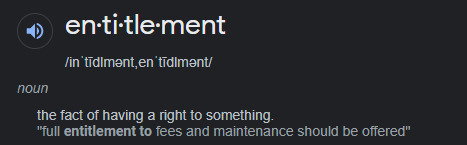

Nicholas Alexander Hayes' figure (1)

Nicholas Alexander Hayes' figure (2)

0 notes

Text

SOUTH PARK FANDOM ENTITLEMENT: or, how discourse (and entitlement) ruins things for everybody.

I’ve been wanting to write something like this for a while, and here it is; 4k words on the causes, effects, and dangers of discourse (headcanon discourse, in particular) within fandom. Discourse (and entitlement) is the primary killer of creativity and connection within fandom, and in order to stop provoking it, there needs to be a collective consciousness about what we, as a whole, actually want out of a fandom space. So, without further adieu, here’s my manifesto on fandom (but more specifically, South Park) entitlement, complete with five sections and eight subsections. Let’s get into it!

Part 1: So, what is discourse, and what is entitlement?

Discourse, as we all know, is a staple of the fandom experience. You would be extremely hard pressed to find a fandom entirely free of discourse, whether the explanation is unrealistic similarity in views or differing views with no desire to prove one as more “legitimate” than another. South Park is not one of these fandoms; in fact, its discourse is widespread in both time and space, occurring since the early 2000s and spreading throughout all social media sites with a South Park fandom presence. However, what counts as discourse is debatable (and IS frequently debated), and to be able to properly analyze the causes and effects it has on the fandom, we need to define it.

Oxford Languages defines discourse as “written or spoken communication or debate”. This definition, while not specific to fandom, is relatively accurate to what I’ll be discussing in this post. However, for clarity, I’ll also be providing a fandom-specific definition, which comes from Fanlore. Fanlore defines discourse as “a fan term for discussion, debate, and/or arguments”.

Okay, great! We have our definitions of discourse. However, for the purpose of this argument, I’ll be narrowing the definitions down to the latter parts - namely, the parts relating to debate and argument. Communication, while relevant to the argument, is not the issue with discourse; actually, it often ends up being the solution. But really, discourse isn’t the main purpose of this post; discourse is simply the cause of the greater issue of entitlement. So, in order to analyze entitlement’s effect on the fandom, we need to define that too. I promise this post is more than just definitions.

Once again, we’re going to be using Oxford Languages and Fanlore for our definitions, to achieve both an outsider and insider perspective of what entitlement actually means. Oxford Languages defines entitlement as “the fact of having a right to something”. Fanlore, on the other hand, does not have a specific page for entitlement - but it does have one for fan entitlement, which we will be using instead. Fanlore defines fan entitlement as “words or actions by a fan that imply (or sometimes even outright state) that the creators of a canon or other fans owe that fan something.” The creators part isn’t really relevant here, so we’ll stick with the part relating to other fans.

Now we have our relevant definitions, and we can all be on the same page while exploring what these two terms actually mean for the fandom. However, the introductory sequence of this post isn’t done yet. Before we really get into this, we need to talk about some relevant examples of discourse, specifically in the South Park fandom. I promise the part discussing examples of entitlement will come later.

So, what counts as a debate/argument within the fandom? I can come up with a few off the top of my head;

Is Kyle short or tall?

Is Stan a jock, or is his sportiness played up by fandom?

Is Butters pure of heart, or is he secretly kind of a dick?

Is Tweek ‘soft’ or ‘feral’?

What the fuck is going on with Craig?

These debates (though most specifically, the first one) have been going on for a long time. I know the intricacies of the first two debates the best, so I’ll be using them and their commonly used arguments as examples throughout this piece.

Now we can be done with the introductory sequence! We know what discourse is, we know what entitlement (and fan entitlement) is, and we’ve seen a few common examples of how discourse presents itself in the fandom. However, most of you already knew all of that. Now, we can actually get into the meatier part of all of this, namely, why is this a thing, and how does it actually lead into entitlement?

Part 2: How does discourse start?

The root of discourse in any fandom is hard to pin down, but we can narrow it down to two general categories; canon-led discourse, and fanon-led discourse.

i. Canon-Led Discourse

In this section, I’m not going to be describing how people originally used canon to come up with their fanworks. I think the concept of headcanons is relatively well known to all of us. However, I am going to be describing how people use canon to facilitate discourse. There are two different ways this happens, and surprisingly enough, they both directly contradict each other. So, let’s get into the canon paradox.

Let’s start with the first way; weaponizing canon. For this example, we’ll be using the short Kyle vs tall Kyle debate, with Post-Covid being the canon we’re weaponizing. Post-Covid, much to the chagrin of much of the fandom, gave us canonical adult designs - or, at least, as canonical as designs as we have so far. There are many aspects of these designs that people began to dissect and discuss, but one of the more discourse-y ones was Kyle’s height. Heights in Post-Covid were often inconsistent, but in most scenes, Kyle was depicted to be taller than Stan. As such, there were many ‘I told you so's' among the fandom. Another example of this would be the trans Kyle headcanon; Kyle is canonically AMAB, and people in support of trans Kyle are relentlessly criticized and reminded of this in order to devalue their headcanon. This is one way that canon-led discourse is facilitated; canon is taken as absolute gospel, and those who defect from it are punished and criticized.

The second way directly contradicts the first way, but is often used by the same people. The second way involves deviating drastically from canon in response to canon-based headcanons one doesn’t like. Let’s take jock Stan as an example of this. We all know that Stan is a sporty person, and his interest in sports isn’t exclusive to the first season. Evidence of this can be found all over his room. People who use this method of discourse will understate this in order to undermine the headcanon - for example, claiming that Stan’s interest in sports is exclusive to the first season, and those who support the headcanon are making a mountain out of a molehill. How do these two ways exist simultaneously, especially among the same people? How can you weaponize canon in one scenario and undermine it in the next?

The answer is that it’s not really about what’s canon. It’s about stifling and undermining opposing views, and creators, in any way possible.

ii. Fanon-Led Discourse

Fanon-led discourse refers to ways that people in the fandom utilize their fellow fans, as well as fandom tropes, to create discourse and convey their displeasure about concepts and headcanons that they don’t like.

One way in which this is common is the martyr-ization of ‘unpopular opinions’, in which those who share these controversial opinions (whether through Twitter threads, specific blogs, or any other variety of post) believe that they are ‘martyrs’ for doing so, and that it is honorable that they’re brave enough to risk fandom persecution in the process. This is obviously a ridiculous concept - we are, after all, discussing headcanons about South Park - but the effects of it are very real, and those effects are often what lead into entitlement. Finally, we’ve gotten to that part! So, let me introduce you to the discourse to entitlement pipeline.

This concept of fandom persecution is not uncommon in any fandom - those who deviate from the norm will always feel as though they are being inherently punished by the lack of content supporting their ideas. This is what causes the entitlement. Due to this ‘punishment’, those with ‘unpopular opinions’ believe that they deserve content catered to them. They deserve content that entertains them. They deserve content that adheres to their headcanons, and when met with a lack of this content despite their efforts, their frustration gets worse, and they believe they deserve the content even more. The frustration is normal. It sucks to be part of a fandom where very few people agree with you. But there are also better ways to handle it. This cycle occurs on all platforms, and it occurs in varying levels of severity - some are serious enough to engage others with hostility on their own posts. Others will post about “let’s leave [x] in the past” and “come on, artists and writers, change it up a little!” Some will try and lessen the effects of this entitlement by instead saying that “it’s fine to write whatever you want, but [x] is just less interesting…” or “this was good, but I wish there was a proper [x]...”

These are different variations of entitlement, but they are entitlement, all the same.

Part 3: So, why does this matter?

i. Content is not made specifically for you.

This is one of the main issues with entitlement, and the blatant violation of social norms that one commits by performing one of the above actions; when creators make their content, they don’t make it specifically for you. A creator has no obligation to adhere to your headcanons. They have no obligation to make their content more interesting for you. You don’t get to decide whether their works are appropriate, or close enough to canon, or even just outright good. This is not your job to decide that. To be entirely frank; your unsolicited opinion on someone else’s content or opinions does not matter unless they are explicitly comfortable with receiving constructive criticism, because IT WAS NOT MADE FOR YOU.

Art and writing can be a very personal experience. Some artists and writers do make content for the community, but many make it exclusively for themselves; because making that kind of content makes them happy. They aren’t asking for criticism just by putting their work out there. Publicizing their work, especially when that work doesn’t disparage anybody, doesn’t give you the right to decide whether it should have the right to exist. This is a very terminally online perspective. It’s very easy to lose sight of social norms and politeness when you don’t see the face of the person that you’re criticizing, but they’re there. They exist, and their works aren’t made exclusively for your criticism and consumption.

In 99% of scenarios, you have absolutely no right to police someone else’s work. If you have enough of a functioning hand to type out a statement claiming that one work should be left in the past, you have enough of a functioning hand to type out or draw a work supporting your interpretation. If you want work of your own interpretation, do it yourself.

But aren’t these kinds of people in the small minority? Why does it matter?

ii. Bad behavior in one area of the fandom encourages it in others.

The reason it matters is that it doesn’t stay as the small minority. In social psychology, this is called deindividualization - the process in which one loses their self awareness while in groups. The reason this happens is the belief that if one person is doing it, it’s more socially acceptable to do it. It’s the same kind of process that leads to witch hunts. One person being disrespectful makes everyone feel as though they have the same right to do so.

That first kind of entitlement I mentioned up there - the entitlement in which people are bold enough to harass others on their posts - lead into the second and third kinds, and those lead into even more subtle kinds. Kinds that involve being rude on tags in an artist's posts, along the lines of ‘this is good, but…’. Kinds that involve going into an author’s comment section and criticizing a specific part of their work, but doing it in a ‘kind’ way. It doesn’t matter if you do it in a kind way. You are still displaying entitlement towards an author’s work - you are still making the claim that the work is not good because it is not created directly for you, and you are still claiming that you are ‘owed’ something by the author. It’s fine not to like a specific type of content. It’s not fine to give unsolicited criticism to someone’s headcanon, artwork, fic, under the ruse of constructive criticism or kindness. Someone else doing it in a worse manner doesn’t make it okay for you to do so; it’s still unnecessary and hurtful.

iii. Entitlement decreases motivation, which is needed to keep fandoms alive.

One comment directed towards an artist or a writer may not do much, but the deindividualization effect - in which many people start to join the fray - diminishes the motivation of a creator. It’s hard to get yourself to continue making content when you’re met with relentless criticism and entitlement, whether subtle or not. The way people treat creators in fandom has been an issue for a long time - creators are met with death threats, with entitlement, with praise to their faces and slandering of their headcanons in an area where the creator can still see it. This doesn’t make people want to keep creating. It makes them miserable.

By being this entitled, or facilitating entitlement through discourse, one ruins the fandom for everybody. Things get actively worse when discourse becomes common - people start to leave, and those who don’t become disillusioned with creating. It’s hard to be part of a fandom where your opinion is not as common. But this is not the way to handle it. Cruelty towards a creator will often make a mark more than positivity does, and as such, it doesn’t matter if you leave a kind comment first. It doesn’t matter if you make a disclaimer that ‘you can write whatever you want’, because that’s not actually what you’re saying, and that’s not what’s actually going to affect the creator’s decision to continue creating.

To keep a fandom alive, people need to create content. Posting passive-aggressively about tropes you don’t like doesn’t count as content. Posts encouraging others to share the opinions they hate doesn’t count as content. Negativity is not enough to keep a fandom alive. Be grateful to fandom creators - they’re the ones who make fandom spaces the wonderful places they typically are. Allowing yourself to get caught up in the wave of discourse is the quickest way to ruin it.

Part 4; But isn’t there content that people shouldn’t be allowed to produce?

There are instances in which people will simply hate headcanons for no reason at all, but often, people feel the need to justify their hatred - and that hatred is often justified with the claim that the relevant headcanon/concept is inherently harmful. Content that directly harms people shouldn’t be encouraged in fandom, but doesn’t that contradict what I said up there? How do we reconcile these two points?

i. ‘Problematic content’ differs significantly in severity.

The South Park fandom has its horrifying content; in fact, that content likely occurs at a higher frequency than most other fandoms just due to the nature of the show. Anyone participating in the fandom for more than a few weeks will inevitably learn about these horror stories, ranging from horrifically antisemitic WWII aus to blatant racism. And these things should not be allowed in the fandom.

However, the term ‘problematic’ is broad, and applying it to the above tropes as well as less harmful ones (i.e. short Kyle, short Tweek and tall Craig, etc) dilutes the actual nature of problematic content, as well as promotes the idea that fandom as a whole needs to be cleansed. It doesn’t. There needs to be a more significant distinction between the above tropes before one can safely say that there is a subset of content that should not be produced under any circumstances - and a way to measure that is by asking yourself is this problematic, or could this be problematic? Is the content irredeemably bad, or can it be handled respectfully? Is the content unrealistic to the point where it could only be bigotry, or could it be a legitimate possible outcome for that character? Is it impossible to come to this conclusion without the influence of bigotry or stereotypes, or could that portrayal come with innocent intentions?

And beyond that; is this portrayal agreed upon by the large majority of the potentially affected group to be legitimately problematic, or is there a split? If so, who do you align yourself with?

ii. One person’s view is not sufficient for determining whether content is problematic; other factors have to be considered.

Legitimately problematic tropes and ideas, including the specific ones I mentioned above, are agreed by the massive majority of the affected group to be genuinely horrific. However, more questionable ones aren’t; the split is often even less than equal, with those finding it problematic being a part of the loud minority. So, how do you address this situation?

Firstly; not only is one person insufficient for determining whether content is problematic, but in a lot of cases, one group may even be insufficient. The conversation about feminine/gender nonconforming Kyle is particularly relevant here; the importance about the Jewish perspective on such an issue is impossible to overstate, but gender non-conforming people and feminine gay men also have a stake in the conversation. GNC people cannot determine what is antisemitic (unless they’re Jewish, of course) and Jewish people cannot determine what’s an anti-GNC stance (unless, again, they’re GNC), but both perspectives still must be considered. You can’t make a decision on how problematic a portrayal is without taking an intersectional approach, and as such, the perspective of one individual is not damning. It gets even more complicated when you consider that the perspective of a group is not necessarily cohesive - one person may find a portrayal offensive, while another may think it’s valuable. Both opinions are valid, but they’re also inherently contradictory - you can’t fully incorporate both into your belief system about the issue. Multiple perspectives are even more valuable in this situation.

Another factor to consider is sociopolitical context - or, more specifically in the context of this argument, how are these groups actually portrayed? Once again, the question of GNC Kyle is important here - how often are GNC Jewish characters portrayed on TV, or in media in general, especially in a positive light? Fighting against stereotypical portrayals (feminine, nerdy Jewish men) is important, but the fact of the matter is that people who fit into that exist, and what good does it do them to remove all fandom representation out of fear of buying into harmful stereotypes? Attacking content relating to these fandom portrayals doesn’t necessarily help them; it actually just limits the rare positive representation that they do get. In this paragraph, I’m speaking about GNC Kyle, but the same concept applies to other groups; by directing anger towards portrayals that could be considered stereotypical, one tears down the vastly important diversity of the relevant group, and limits what people are allowed to see down to the most palatable versions. And that’s not the only issue that comes from insisting on exclusively palatable portrayals.

iii. There is legitimate harm in letting outside bigotry cloud your concept of a problematic depiction.

This is a common perspective throughout the fandom, and it’s diverse enough that it ends up being used in many threads of discourse; feminine Kyle and short Tweek being notable ones. It comes from a place of good intentions and of dispelling bigoted views and portrayals - but in the process, it attacks those that also come from places of good intentions. Short Tweek and tall Craig may be the most common example of this; posts about infantilizing Tweek are endlessly common in an effort to limit the commonality of such a portrayal. But in the process, the attacks on such a portrayal actually DO infantilize Tweek, as well as any actual short men. Accusing a couple with height differences of being “heteronormative” due to inherent bias from the creator delegitimizes gay couples with height differences. A similar perspective is cast onto feminine Kyle and masculine Stan - accusing the portrayal of being born of fetishization harms real life gender nonconforming people, as well as gay people in feminine/masculine relationships. In the process of trying to prevent problematic content, one is legitimizing the perspective of the bigot.

I know this portrayal comes from good intentions, but it comes at a heavy cost - the cost of determining what’s an ‘acceptable’ way for a character of a marginalized group to look, present, behave. Hatred towards short Tweek and tall Craig reinforces the perspective that gay couples with height differences are really just heterosexual lite. Hatred towards feminine Kyle and masculine Stan reinforces the same. Some people who depict these portrayals do have bad intentions, but many do not. It’s easy to forget that most people, regardless of what the news will have you believe, do have good intentions.

Entitlement on behalf of one’s own good intentions is still entitlement. You’re not entitled to someone else changing their portrayal because it offends you. It’s okay to give people the benefit of the doubt, especially when there is reasonable basis for their portrayal. A character having some aspects that fit into a stereotype doesn’t necessarily mean the portrayer believes that stereotype is legitimate. It doesn’t necessarily make the character out of character, either; some people have traits that do fall into stereotypes, and that’s okay too. There IS some content that should be struck down immediately, but if there’s a question on whether the content could be bad, it’s okay to assume the best of someone until further evidence comes up. It’ll probably make your fandom experience much more pleasant in the long run.

Part 5; So, how do we fix all of this?

Discourse is, as mentioned earlier, a part of fandom. It’s inescapable. But there are ways to make it kinder; namely, buying into the ‘communication’ and ‘discussion’ parts of the definitions I mentioned way back at the start. Discussion is fine. Disliking a headcanon is fine. We all have tropes that we dislike, or even hate. But falling into the rabbit hole of entitlement crosses the line.

In order to decrease entitlement, we have to decrease discourse - and in order to decrease discourse, we need to stop providing opportunities for it. We need to stop providing opportunities to air out hatred for other peoples’ opinions, and we need to stop legitimizing and martyr-izing the suffering of those who don’t fall in line with the majority. It’s okay to have varying opinions. It doesn’t make you special. It doesn’t make you more deserving of content, because none of us inherently deserve special treatment from creators.

Getting involved in creating content is a great way to help fix the general issue of entitlement within the fandom. Draw art that falls exactly in line with your specific takes on the characters. Write fanfics and describe the characters and relationships in any way you want to. Everyone can draw, and everyone can write, with enough practice. Write meta. Make edits. Make playlists. All of these are valid forms of expressing your perspective on the characters - and all of them contribute much more to the fandom than posts striking at perspectives that may differ from your own.

The internet is a great place to say whatever the hell you want, and technically, you can. There’s nothing stopping you from typing out a hateful response to someone’s posts, or slipping a little criticism into the tags, or making a post intended to stir up controversy. But before you choose to do so, consider that everyone you’re attacking is a person, and consider that the large majority of them are genuinely good. The people with bad intentions are always the loudest, but that shouldn’t delegitimize any concept that they chose to back. Any interpretation can be pushed for unsavory reasons; it doesn’t mean other people who support those interpretations are inherently bad, nor that it’s your job to correct them.

It’s okay to have faith in your fellow South Parkie (lol), and when you don’t like something, it’s okay to keep it to yourself. Supporting the opinions you love and making content rather than trying to shut it down will make you a much happier person, and it’ll make the fandom a much healthier space.

187 notes

·

View notes

Link

I met two members of London Suede, Brett Anderson and Mat Osman, in the lounge of a major New York hotel. They were at the beginning of a four-city tour of the U.S. in support of their newest release, Coming Up on Columbia Records. I got a chance to talk to them about songwriting, performing and who they think can write a good song. Brett did almost all the talking and never took his sunglasses off. Hey, he's a rock star; he doesn't have to. This was my first time interviewing a British band and I couldn't escape the feeling of being Rob Reiner in Spinal Tap.

An interview with Brett & Mat by Dave Levine for Urban Desires, May 1997. The rest of the article under the cut. (x)

London Suede, or Suede as they're known in England, is at the forefront of the new Brit-Pop explosion that includes bands like Oasis, Blur and Pulp. They write lush poppy songs reminiscent of Bowie in the late seventies. As with many of the new British bands, success in America is hard won. They released their first record, Nude in 1993 and it went #1 in England but didn't make much sound on this side of the Atlantic. Why? well Brett thinks he knows, so read on.

UD: So have you guys been to New York a lot? LS: Yeah, we've been here quite a few times. UD: So what's the difference between London night life and New York? LS: I don't know really. I think every city in the world is pretty much the same, isn't it? I mean there's no difference between New York, and London. Everyone likes to think that they live in the biggest, baddest city in the world. London's just as big and bad as New York and Rio de Janeiro is just as big and bad as London. I think at this point in the twentieth century everyone is so well connected and the world's just become one big place... got tramps sittin' in the street and sex and sleaze and stuff like that. It's all the same, isn't it? UD: Except for the bars in London close at 11:00. LS: Yeah, but there are after-hours places. UD: What's your favorite place in the world to play? London? LS: Probably Thailand or Scandinavia. UD: Why? Because the crowds are crazy, and they just love it? LS: They're mad, especially in Singapore. They sing along with every word. UD: What about New York? To me, New York crowds are jaded. LS: Yeah, they are a bit. Last time we played here it was shit. I can't really get my hands around the mentality. I don't really know how to put this. I mean, I don't want to be offensive. UD: Go ahead be offensive, it makes good copy. LS: New Yorkers want to be shouted at or they don't respect you. They tend to assume that quietness equals weakness, which it doesn't. That's an assumption that I don't think anyone in the world makes. The first show we did here was really boring and the second show we were going through quite alot of bad times with the band. We were having alot of internal arguments and it was a real low point in our relations. We were so fucked up with each other, we absolutely fuckin' hated each other... I don't know how to put it.... UD: New York probably loved that. LS: Exactly, it came across in the gig. It was a real wild gig. UD: I read in your press release that when you first started playing, people hated you. Is that true? LS: (Both laughing) UD: Critically too, and then at some point it changed. Did you do anything? LS: No we just got better, that's all there is to it. We always were going against the grain, and so when you're doing something that is going against the grain and you're not very good at it, people hate you. When you do something against the grain and you're good at it, people start thinking it's something special. UD: So it was just experience, then? LS: Experience of playing live, learning how to sing and how to write songs.

UD: I want to give people here in the US that don't know much about you some background. How did you get started? LS: No one really fuckin' cares anyway. UD: ... Okay. Why do you think it's hard for modern British pop bands to break into the U.S.? LS: I know exactly why that is, 'cause the American music industry is obsessed with categories and things. And we aren't that happy with being categorized. In Europe we're just a pop band. We're #7, and George Michael is #5. You know, we're just a band. There is a song on the second album called "The Wild Ones." When we first played it for Sony they were doing somersaults. We thought it was like #1 and they took it to radio stations, and they couldn't get it played. They couldn't figure out if it was a love song or a rock song by a band with a bunch of guitars. We took it to alternative and they thought it was too mainstream, and we took it to mainstream and they thought it was too alternative. It's never been my desire to be neatly sectioned into some little box. Then you lose any mystery, any danger, any X factor that you might have had, and I don't think that many bands in Europe are happy being categorized like that. UD: Your press release touted you as the best lyricist of your generation-- LS: --I wouldn't believe anything it says there-- UD: --do you have any problem living up to that? LS: Do I have a problem with that? Yeah, I don't think it's true. I don't think anyone is the best lyricist of a generation. I should burn that press release. It's been the source of so much inflammatory rubbish. UD: What inspired you to start playing? LS: We just loved music and wanted to be in a band. LS: I wanted to be a song writer. UD: What songwriters do you admire? LS: Kraftwerk, Lennon and McCartney, Pet Shop Boys. UD: What do you think of Billy Bragg? LS: I think he's got a big nose. UD: (Laughing) I guess that would be 'not too much'. LS: Naw, I think he's alright. I like some of his love songs. UD: Yeah, he does write good love songs. LS: It's like Bob Dylan; I think all these political writers aren't as political when they are writing love songs. I think their political stuff stinks. Bob Dylan's political songs are so fucking one dimensional, and the same goes for Billy Bragg. UD: So you don't believe in the folk, socio-political commentary song? LS: Yeah I do. I just don't believe it's effective when it's put in that crass category. I don't think any of Bob Dylan's political songs were that moving. UD: ... What about "Times They Are A Changing"? LS: Yeah, I guess. UD: What about Elvis Costello? He's a guy who writes political songs. LS: Yeah I like "Shipbuilding." That's probably the best political song ever written. It goes beyond politics, and touches on the human consequences of politics, which I think song writing has got to do. I don't think you can just put numbers and manifestos within a chord sequence. I don't think it strikes a chord in the human heart. I think to actually say something to people you've got to say it with emotion. That's why I think that "Shipbuilding" is one of the best political songs.

UD: What's the worst thing about being on the road? LS: Standing in a pool of someone else's piss when you're on a fucking bus on a three-day journey. UD: Is there a story that goes along with that response? LS: No, that's an everyday occurrence. UD: What do you guys think about Tony Blair? LS: I think it's fucking great. I think it's the best thing to happen to England in a couple of years, wonderful. UD: In the United States they compare him a lot to Clinton. LS: A politician can never be one hundred percent great. I think a politician, as long as he inspires confidence in a positive way, then he's a good politician. And I think Blair and Clinton both do that. UD: What kind of press does Clinton get over there? LS: He gets good press. UD: He probably gets better press over there... LS: ... I'd rather see someone like him than some rejuvenated old skeleton like George Bush. You know what I mean? Some old man that looks like they've been revived, you know, dug up from the dead. UD: If you could just sit at home and write songs, would that satisfy you? LS: I don't think so, it's not boring enough yet to do that. There is part that is mundane. There are some low points but then there are some extreme highs and those highs can inform your writing. I think the point of it all is to actually let things inform other things, and let the whole thing become one big process. UD: Do you guys all get along on the road? LS: We've had fights in the past but not in the last couple of years. Although maybe we should start. LS: There is an idea. LS: Maybe I'll punch our bass player. UD: Head butt him? LS: Yeah, I want to give him a good head butt. LS: I might give him a hug. UD: No, don't do that. New Yorkers won't like it. Don't do the hug thing. Don't be nice or anything.

#suede#brett anderson#mat osman#coming up era#i thought i had posted this before but it seems i didn't?#anyway here it is :'DD

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

One thing that felt uncomfortable to go along with in the CF route for me was when Edelgard lies about what happened at Arianrhod to her closest allies (Black Eagle Strike Force) and blames it on the church. Can you give some insight as to why she does this? Especially when Edelgard criticizes the church for lying to the people of Fodlan, but isn’t she doing it here?

That’s certainly a moment that is genuinely ambiguous / a valid point of criticism and something I’d laud a whistleblower for exposing if it were a RL politician, but also the sort of realpolitik / appearance management that has taken place in most RL wars.

Once you’re the leader of anything, allowing panic, division, etc. at bad moments comes with its costs. Of course this is hardly a carte blanche (see: Beating down legit protesters for superficial “order”), but neither is it a factor that can be ignored completely.

At the point of the Arianrhod attack Edelgard was one month away from seizing control of the landmass and ending the large-scale fighting, having one enemy taken out (the Church) and being able to turn all her resources on the other (the Agarthans)

The agarthans at this point know they’re losing control of Edelgard and they’re not stupid enough to have any illusions about her loyalty. So they fire a warning shot to demonstrate their superior weaponry. Arundel makes a thinly veiled threat to fire it on Enbarr.

Of course at this point he basically gave away his location and allowed Edelgard & Hubert to come up with countermeasures, but they don’t want him to know that yet, their strategy involves that they keep being underestimated, let the Agarthans keep thinking that the “beasts” have no counter for the nukes pointed at their heads.

But they still destroyed half a fortress killing the ppl inside. If she reveals that she’s got a rogue faction infiltrating her ranks that’s firing frightening superweapons nilly willy, there will be chaos outrage and disunity right before the final battle. If she doesn’t make a statement at all and declares it a mystery, no one will believe it and her own faction will get the blame throughout the country. So what does she do? Pin it on the enemy she is currently fighting anyways. The purpose here is not to reveal the Agarthan situation too early so they can focus on the church for now.

It’s unclear if this was ever revealed to the public (probably not, I don’t think she’d cause a stir on principle alone) but the ending cards make it quite clear that the Strike Force was let in on the Agarthan situation later and helped her mop them up.

Yeah, it’s defamation, an indisputable textbook government cover up and maybe even technically a kind of propaganda, but her casus belli existed before it’s not like she’s basing it on the lie, and in most wars throughout history the factions have hidden or made a spin of failures & mishaps and made the enemy look bad.

There are certainly many historical examples of such actions creating problems, such as fueling lingering resentments or creating general mistrust that can led to real information not being believed etc. so it’s by no means a safe action that is no big deal and I can see how it could be a legit dealbreaker for some, you certainly weren’t supposed to be 100% comfortable with it, or anything on the CF route, everyone involves is well aware that they’re doing ugly, costly things because (or so they see it) the alternatives are all worse. In that sense it’s the most self-aware one. It’s about actually looking at the bottom line of consequences, not what makes you feel like a hero.

At the same time, doing things like that that squander her moral credibility genuinely IS a flaw in Edelgard’s leadership style - it’s probably why more ppl didn’t believe her manifesto, “she already lied to us cooperating with these shady guys”, making it look like a ‘he said she said’ situation to the wider public that can’t go & confirm the evidence for themselves. This is why Claude thinks he has a better shot at winning& implementing reforms in VW (”too shady for the ppl to get behind”) - just like Dimitri has no plans and Claude’s secrecy creating mistrust even when his secret plan is utterly benevolent. Doesn’t matter how altruistic you are if you look suspicious it will have consequences I mean that’s how she loses on the other rouses, everyone ganks up on her cause she antagonized them all with suspicious actions. I’m not saying she’s any more perfect than the other 2.

but putting that on the same scale as what Rhea did is comparing a candle to the sun.

And maybe the Kantians in the audience will disagree with me but it can be a bit unhelpful to classify different actions of vastly different consequence and magnitude as “Lies”. There is a common principle (telling things that aren’t exactly true) but different magnitude. Clearly “The Confederacy was all great and glorious” and “I totally didn’t eat my little sister’s share of toffees” aren’t on the same level of immorality.

Neither is below the “everythings fine and dandy” line but one is a lie about one incident for one clear purpose, and the other is creating a whole fake world view for the express purpose of control, maintaining harmful systems, suppressing any advancement of science & technology... for 1000 years.

Scale, purpose and consequences are totally different. The arianrhod coverup coming to light would spark controversy & discussion on wether she should have done it under those circumstances; Some might change their opinion about her but overall everyone already knew that she’s not above dirty methods. If you told the average citizen of Fodland about all of Rhea’s lies, everything they know would be wrong. They would go from Adoring & worshipping her to being very confused about what’s true.

It’s the difference between your average modern-day politician doing backroom deals with diverse industry lobbies to accomplish their other goals, and a place like Saudi Arabia.

To get perspective here, let’s look at another example: Claude’s deceptions.

He, too, ultimately wants what’s best for everyone and a lot of the time he decides to fool people to avoid fighting them, I don’t mean to bash him at all, but let’s look at his actions in and of themselves:

Look at the sequence where he, Hilda & Byleth rope the church into helping them - that’s even more outright with the slimy politician tactics: He tries to downplay alliance involvement though he is totally in control, he says that “getting the church on our side will make fighting the empire look like a moral cause” implying that he doesn’t think it is one but wants to portray it as one to get ppl’s support, we’re told he made lots of promises to the merchants to get them on his side (so like that’s literal lobbyists), he installs Byleth as a figurehead, he tells the church ppl he wants to help them get back their old power when he really wants it to diminish and to drastically reorder the society.

He tells everyone he’ll help them save Rhea but while he still has basic human empathy for her & what happened to her he makes it clear he doesn’t want her to go back to being archbishop... at all. He even does this with Byleth: “Yeah, sure, teach we’re totally gonna save her” though in their case he tries to hint that she’s not to be trusted for their own good. Despite his dishonesty, he’s actually a very good friend to them imho. (#broTP)

In the end the power struggle between Claude and Edelgard isn’t personal nor a righteous struggle - he’s just taking advantage of the chaos she caused and he needs the seat of power to reach his own goal. He thinks he can do it better and she’s in the way (and to be fair, she thinks the same about him)

It’s your classic slimy politician: “he’s pretending to be for family values etc thing but really he wants power & is in cahoots with economic interests and he won’t do what he promised” etc. ... except with the plot twist that he’s deeply good and not actually all that ruthless. In a sense he’s as much a total subverted trope as Edelgard.

So doesn’t he have the right to criticise Rhea either? Or do you see how, while not per perfect, he’s miles better and not remotely the same?

Edelgard isn’t 100% truthful, but by and large, she made her intentions very clear with the pamphlets and stuff (even if it meant antagonizing ppl who were against that) and all her soldiers generally know what they’re fighting for and are going to get out of it if they support her, or what the consequences will be if they fail, even if she kept some of the “how” to herself.

Which isn’t to say that Claude ever makes ppl act against their interests even if it’s sometimes what he sees as their interests.

Under Rhea’s rule no one knew what the government’s doing, why it’s doing it, or to some degree, even that she IS the government... for 1000 years. There’s some cult of personality going on. She probably genuinely believes that it does benefit the sheeple to be “guided” by her, but she hasn’t even told Seteth about all she’s doing, she’s pretty much accountable to no one.

In terms of honesty, we could probably rank the lords like this:

Dimitri (a few omissions at worst)

Seteth (lies mostly out of self-preservation)

Edelgard (some convenient secrecy here & there)

Yuri (about the same as El but I’d put him slightly higher for the fake betrayal)

Claude (no one rly knows what he’s up to, but he gets ppl what he promised them and doesn’t outright betray them)

(very)

(big)

(gap)

Rhea (fake history, isolationist bubble, abuse of power left & right, manipulation, will smile in your face while planning to make you a meat puppet for her mom)

#fe3h#fire emblem: three houses#fire emblem three houses#three houses#edelgard von hresvelg#edelgard

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

AUTONOMY AND COUNTER-POWER: RETHINKING THE QUESTION OF ORGANIZATION AFTER THE YELLOW VESTS MOVEMENT (2020)

First published in ACTA, January 6th, 2020.

Translated by J.R. and Ill Will Editions.

This text stems from a talk given by the French journal ACTA during an international congress organized by the Catalan magazine Catarsi in Barcelona last December. Now in its third iteration, the congress facilitates the exchange of intellectual reflection and militant experience between different countries, touching on themes such as unionism, urban struggles, the realities of fascism today, and the stakes of political communication in the digital age.

We take this opportunity to develop a report on the sequence of struggles in France and across the globe in recent months, considering both its novel characteristics and its strategic impasses. Our aim here is to place the question of organization back on the table, while also proposing a rough sketch of what the seemingly-obscure concept of victory might look like today. -ACTA

The year 2019 witnessed a new wave of uprisings on a planetary scale. Dozens of countries around the world watched as their cities erupted into violence, their economies were paralyzed, and the legitimacy of their governments was challenged in the streets. Despite obvious differences in context, the majority were popular mobilizations centering around common issues: worsening precarity, social regression and fiscal austerity – the result of several decades of unchecked liberalism. Added to this was the corruption of elites, the disrepute of the political class, and the authoritarianism of the State.

A common element in a majority of these cases is the collapse of institutional mediations. Many of these movements formed at arm's length from parties and unions — when they were not openly hostile toward them. In France, the skepticism of the Yellow Vests toward any form of representation is evident to anyone, while the more recent movement against the proposed pension reforms has crystallized a tendency among the more combative union bases of acting autonomously from their bureaucratic leadership. We see this at several levels: for instance, in their decisive insistence on December 5th as a strike date, in their will to take control of how the strike will be handled (i.e. a “renewable” rather than a “pearled,” or slowdown, strike), in their experimentation with more conflictual forms of action, and in their refusal to obey calls for a truce (even when they emanate from trade federations themselves).

The Yellow Vests phenomenon casts a stark light upon a basic feature of our time, namely, that traditional representative bodies are no longer in a position to capture the energy of protest, let alone direct it. From here on out, those who face down the State are on their own. From Paris to Santiago, by way of Beirut, popular revolt is shattering the recognized frameworks of struggle, fleeing in every direction. At a planetary level, its principal weapons are the blockade and the riot.

While this reduction of the antagonism to two terms may in some cases safeguard the people against the betrayals and intrigues of politicians and the various other apparatuses, it is no less problematic when one considers its long-term consistency and its possible outcomes — we will return to this later.

To be sure, several of the recent movements have succeeded in winning tactical victories: the abandonment of the new taxes at the root of the revolts in France and Lebanon, the suspension of the public transport fare hikes and the promise of a constitutional referendum in Chile, the abandonment of the austerity plan in Ecuador, the withdrawal of the extradition bill in Hong Kong, the resignation of Bouteflika in Algeria, etc.

States everywhere have bowed to popular pressure. Yet, with the exception of a few, the movements have kept going beyond these tactical achievements, and still continue today. In fact, it is this continuation, precisely, which reveals a major difficulty that cuts across every struggle in the current period: we have no shared conception today of what a victory might be, at either a tactical or a strategic level. (Insofar as a victory, in our view, is always the inscription in history of a point of irreversibility.)

We cannot see clearly what victory looks like. For us, the concept of victory is obscure.

By contrast, the twentieth century had at its disposal a relatively clear understanding of victory, one widely accepted by revolutionaries throughout the world. To be victorious meant to seize State power. This was to be done either by classic electoral means or else through an armed insurrection. Those “progressive” formations that came to power by respecting the rules of bourgeois democracy wound up either abandoning any prospect of social transformation, under the weight of institutional constraints or because of the intrinsic corruption of state structures, or else they found themselves vulnerable and powerless in the face of the reaction of the propertied classes and their imperialist allies. As for the revolutionary seizure of state power, historical experience has shown that, by itself, it in no way guarantees a general advance toward communism and that, consequently, a successful insurrection alone cannot define the concept of victory. (In other words, we cannot remain satisfied with a strictly “military” definition of victory.)

But we have not yet been able to put forward a new concept of victory adequate to the novelty of the movements that have shaken the world in recent years and which have everywhere run up against the same strategic impasses.

*

The question of victory is directly related to the question of organization. The determination of this or that hypothesis of victory leads us to adopt a certain type of organization adapted to the success of this hypothesis. Lenin’s theory of the vanguard party (endowed with military discipline and committed to the objective of taking state power) issues directly from his analysis of the failures of the revolutionary uprisings of the nineteenth century—foremost among them being the Paris Commune. Thus was he led to delineate a new type of political organization capable at last of leading the proletariat to victory. And if the Leninist party-form imposed itself as the canonical form of revolutionary organization during most of the 20th century, it is largely owing to the prestige derived from their 1917 victory. The hypothesis had, in a way, proven itself.

Designed for seizing state power, the Leninist party certainly showed its formidable insurrectional efficacy; however, it proved to be radically deficient in the exercise of this power when it came to the post-revolutionary phase and the achievement of the strategic objectives of communism. As Alain Badiou wrote, “The Leninist party is incommensurable to the tasks of the transition to communism, despite the fact that it is appropriate to those of a victorious insurrection.”

Throughout the 1970s, French Maoists and Italian autonomists had (among other things) counted the overcoming of the traditional Leninist paradigm among the essential tasks of the politics of emancipation. It is this problem that we have inherited today.

We cannot help but notice the general disorientation that runs through the whole of our camp on this issue. Whereas some have decided to sweep away the motif of organization completely, on the pretext that it is, in and of itself, synonymous with a mortifying alienation, others have been content to carry on with the ossified model of the avant-garde party. The former glorify the movement, and perhaps even pure movement itself, reducing their political practice to following each of its new figures. Although they often display remarkable tactical activism during sequences of acute conflictuality, their fetishization of an affinity-driven approach condemns them to retreating during non-movement periods. As for the latter, they remain rigidly loyal to obsolete organisational models, and this prevents them from truly entering into and becoming internal to the movements in question, leading to a growing disconnect with the new dynamics of struggle.

We believe that the problem of organization is once again an open question, one that demands to be taken up anew by revolutionaries. The Yellow Vests movement has been a formidable testing ground for the relationship between mass movement and organized subjectivity. For us, one of the essential lessons of this sequence is that activists must be in the movement “like fish in the water.” They must be truly internal, that is, actually in the movement. This means participating in its basic assemblies, establishing connections with its local groups, carrying out investigations, upholding its main deadlines, and allowing the novelty of its forms of struggle to “contaminate” them—in short, putting themselves in the school of the masses. They cannot remain content with a posture of exteriority, or even worse, of scorn, which was something too many leftists fell into at the onset of the 2018 winter uprising. As Marx put it in the Manifesto: “Communists everywhere support every revolutionary movement against the existing social and political order.” That being said, however, the position of revolutionary militants cannot be purely one of tailing or following along [suivisme], for it is not merely a question of accompanying the movement, or even of disappearing into it, but of intervening in it politically.

This brings us to the fundamental point: political intervention always leads to a division. What unites a movement, especially at the beginning, has a negative dimension: different sections of the people come together in common opposition to a particular government, a particular bill, a particular aspect of the dominant order. The follower mentality treats this unity as something to be preserved at all costs and regards any effort to introduce political divisions as tending to weaken the movement itself. On the contrary, we believe that the negative unity of a movement always covers up important (sometimes even antagonistic) contradictions and that it is precisely the role of revolutionaries to intervene where these contradictions exist—and thus, to accept the division. For it is only through this work of division that true, affirmative unity can be built.

This kind of work has been undertaken within the Yellow Vests movement, for example around the question of antifascism. There is no doubt that the presence of the extreme right, whether in terms of diffuse reactionary opinion or the violent activism of small groups, was notable at the beginning of the movement. Nationalist, neo-fascist, or Pétainist formations felt comfortable enough to unfurl their banners at the Étoile roundabout, to strut down the Champs-Élysées, to beat up leftist activists—until the brutal attack on an NPA contingent on 26 January 2019. The organization of an explicit antifascist response made it possible to rout these nationalist groupuscules, which were de facto excluded from the marches. At a deeper level, the early construction of an antiracist front bringing together organizations based in working-class neighborhoods such as the Adama Committee, local Yellow Vests groups, and various autonomous collectives allowed the contradictions of the movement to be worked on politically, helping to develop its watchwords and thereby gradually marginalizing its reactionary component.

It is also clear that the movement’s political maturation process was accelerated by an early collective experience of police and judicial repression (that is, of State authoritarianism) at levels that had previously been reserved exclusively for the racialized populations of working-class neighborhoods—yet which have now become the default mode of repression meted out to the entire social movement.

We argue that the task of organized militants during a movement is not only to provide tactical support for mass action but also to carry out a properly political intervention within the movement, which in most cases will entail a deepening of a certain number of its internal contradictions.

But if the organized must be sensitive to the irruptions of events (rather than obsessing over the maintenance and reproduction of their own organized process), getting organized does bring with it a duration proper to revolts by crystallizing their most advanced political contents. This other sense of time is what allows organized revolutionaries to continue the political work even in sequences of low conflictuality. They get organized by taking root in a territory; by opening and running accessible, public spaces; by establishing durable structures, spaces for self-education, and tools for propaganda and debate; and by deepening theoretical elaborations—in short, by practicing a militant program.

As Marx observed, since they capable of imagining the next stage of the political process, communists are not satisfied with following the pure present of revolts. In particular, they cannot be satisfied with a succession of tactical gestures (however spectacular) lacking any strategic interrelation. Here again we have detected a recurring weakness: although we, in France, have been living in a period of exceptional and almost uninterrupted social conflictuality since 2016, we have observed the fragmentation and the inconsistency of revolutionary organizations. A short-sighted “movement-ism” seems to be preventing any long-term recomposition.

*

The Yellow Vests movement has confirmed this: any politics of emancipation is today practiced at a distance from the State and its institutions. As a result, any organized process committed to emancipation can only be autonomous. The Yellow Vests have learned to rely on their own forces, they did not need any trade union or any political party to bring about a level of social antagonism unseen for over half a century. To borrow from Negri in his 1977 text, Capitalist Domination and Working Class Sabotage, it could be said that they combined a political destabilization of the regime (through the Saturday insurrectional riots) with the material destructuring of the system (through logistic blockades, the occupation of roundabouts and their territorial spread). Albeit in a fragmentary and incomplete way, they practiced larval forms of a popular counter-power.

This brings us back to the strategic considerations set out above. What do we mean by “counter-power?” Counter-power is the preliminary form of autonomy: it is both “liberated space,” a field of experimentation prefigurative of all other social relations, and “conflict zone,” a particular point where the reproduction of social command is blocked. Here positivity cannot be dissociated from negativity, nor creation from antagonism. For “the latencies of the future contained in the present are not limited to existing in ideological representations and political programs. On the contrary, they already manifest themselves in the eruption of the revolutionary process, externalizing themselves in the most surprising and unexpected configurations made possible by the successive puncturing of the dominant forms of relations,” as Curcio and Franceschini wrote in their 1982 text, Drops of Sunlight in the City of Specters.

To the extent that we must do away with the idea that nothing is possible prior to the conquest of central power; to the extent that the decline of the State must become not only an historical horizon but a principle visible in the present through political action itself—to this extent, counter-power is today the elementary reality of any emancipation process.

(France dotted with “yellow communes”—those occupied roundabouts and other innumerable pockets of self-organization which, in addition to the metropolitan riots, allowed thousands of proletarians to rediscover the meaning of fraternity while also laying the material conditions for a mass economic blockade—the France of last winter was undoubtedly a life-size approximation of this process of constituting, from below, an other power, a popular power that sets up its own institutions).

Whether one looks to the ZAD of Notre-Dame-des-Landes, or to the Yellow Vests themselves, recent experience shows that any dynamic of counter-power must confront the problem of self-defense and of protecting this counter-power. This issue is all the more pressing in the context of an authoritarian turn by the State whose repressive methods have become increasingly unhinged. We must likewise consider the possible forms in which a strategic (and not only tactical) negativity might be exercised—one committed to the destruction of bourgeois law, that foundation of the dominant order, a destruction that the capillary expansion of counter-power alone cannot ensure.

What then are the stakes of putting the question of organization back on the agenda? It is clear that only historical practice will allow us to make real progress on this issue. And that theoretical elaboration can only serve—but this is already a lot—to formulate problems.

We must get organized in the field of self-defense, which likewise determines offensive capacity. In this sense, to borrow an intuition from Tronti, it is a tactical function of mass antagonism. For, as we have said, the accumulation of popular power necessarily runs up against the “prohibitive power” of the State. Once it reaches a certain threshold of strength and temporal consistency, every emancipatory experiment confronts this “prohibitive power” that puts its very survival at stake. To envisage this as a linear process would be the height of naivety. Here is precisely where the role of organized political subjectivity lies: to “remove the obstacles” that oppose the growth of popular power, to break up the enemy’s command structure: “to strip capitalist domination of its hope, its possibility of a future,” as Scalzone put it in 1978. It is unclear, otherwise, how the emancipatory elements that developed “in the womb of the old society” could ever in fact be actualized, ratified, and generalized.

But this function alone does not exhaust the issue. Another essential aspect of any organizational process is its multiplicity. It cannot be “one dimensional.” This was, moreover, the principal error of the fighting formations in the 1970s cycle: the military function ended up absorbing all the others, reducing the specter of political practice to this one partial dimension. On the contrary, the organized must seek to combine and articulate different forms of struggle, different terrains, and different modes of intervention. As one agent of the Imaginary Party pointed out, “People forget, but the party has always been both legal and illegal, visible and invisible, public and conspiratorial.” Its richness and potentiality reside in this plurality.

Organization must therefore also take on the role of political recomposition. Today, there are a variety of trajectories of struggle in the movement that act on specific terrains and claim relative autonomy. This is the case, for example, of feminist and antiracist movements (which are themselves traversed by major fault lines). The question of organization, at present, is therefore just as much a question of organizations. Hence the motif of the front that has been circulating recently, which is one possible form that this recomposition could take. What would be at issue is a space necessarily open to internal contradictions, within which revolutionary militants would have the task of working toward a determinate programmatic synthesis: to foster connections between centers of struggle and different social subjectivities, to thwart the risk of paralysis or fragmentation by affirming a communist projectuality as an evaluative criterion for real situations.

Since 2016, and more intensely in recent months, egalitarian alliances have been formed between combative union chapters, autonomous collectives, local Yellow Vests groups, working-class neighborhood organizations, radicalized ecological militants, and high school bases — our task today is to ensure that these alliances survive beyond mere movement temporalities, that is, to build a space of organization and coordination that might create the bases for a new type of popular unity.

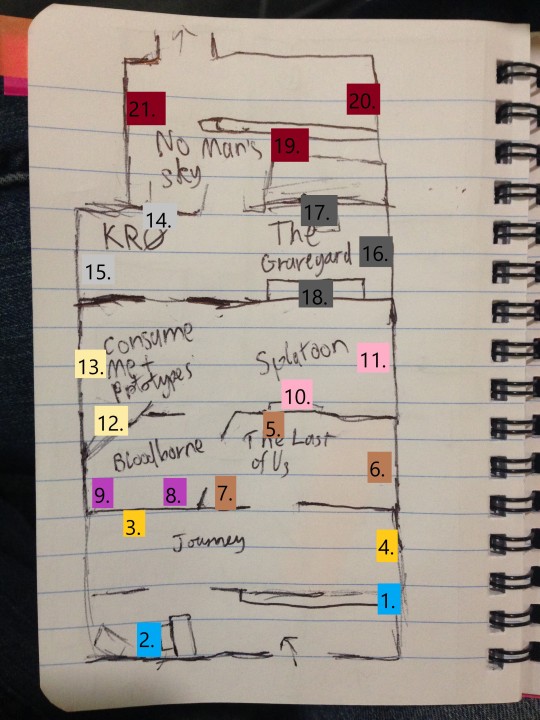

[Photo credits: Maxwell Aurélien James, for the Collectif ŒIL]

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do u think PD is evil? In my opinion it was misguided attempt to free the earth.

Oh, no, I don’t think she’s evil at all. I think she was maybe a bit selfish, ignorant, often a little insensitive, but ultimately well-intentioned. So far, we have no reason to believe the motivations for the rebellion aren’t the same. Here’s the official manifesto of Rose Quartz:

Fight for life on the planet Earth,Defend all human beings, even the ones that you don't understand,Believe in love that is out of anyone's control,And then risk everything for it!

These are not evil motivations, they’re pretty dang good motivations. Additionally, the idea that Gems should be free to decide their own purpose is also a good motivation.

Rose Quartz (Pink Diamond) fell in love with the Earth and the concept of growth and change, this led to her realizing that Gems, too, have the capacity to grow and change and decide who they want to be, this led to rallying Gems and convincing them of this fact, and trying to push the Diamonds away from colonizing the Earth with the idea that this would A) save the life on Earth and B) provide a place for Gems to be free of Diamond rule.

As Greg said, though, there’s no such thing as a good war. While Pink’s decision was perhaps not the best or wisest option, I’d wager any option was going to have dire consequences.

It’s unlikely that even being direct wouldn’t have convinced the Diamonds not to colonize Earth. Remember, after the rebellion Gems entered Era 2, which severely lacks resources, resulting in things like Peridot being smaller with no powers (or so she thought). Gems need to harvest planets in order to continue their species, giving up a planet means taking resources they need away. In “Your Mother and Mine,” Garnet describes a conversation between Rose and Pink (most likely actually between Pink and Yellow and/or Blue) where Rose asks that they leave Earth and spare the organic life there and Pink laughs, saying “You wish to save these lifeforms at the expense of our own?” If Pink didn’t want to colonize Earth, Yellow or Blue would’ve just taken over.

Pink could’ve led a war against Homeworld to free Earth, and that might’ve worked, but it’s unlikely that Pink could win against either Yellow or Blue by themselves and both of them would’ve been against her.

Pink might’ve had her Earth army, but that would go ahead the idea that Gems should be able to choose who they are and what they fight for, she’d just be another Diamond commanding her troops to die for a cause they don’t really have a passion for. By contrast, Rose convinced Gems to fight for the Crystal Gems by getting them to believe they can be whoever and whatever they want to be. They were fighting because they believed in their cause.

Now, maybe Pink could’ve convinced Gems of that fact as well, but I don’t think so. Diamonds are elite Gems, by Homeworld society Diamonds are unique and can do whatever they want while all Gems below them are made to serve them. A Diamond preaching that you can be whatever you want to be is disingenuous and comes from elite privilege and some Gems may’ve just played along because it’s what their Diamond wanted. But the same idea coming from a lower-ranked Gem is a lot more believable. Bismuth is one of the most passionate Crystal Gems, she hardcore believed in the cause, and a big reason for that is because she was so amazed at the idea of a Quartz Gem deciding to be different. I think the message wouldn’t have resonated nearly as much with her if it were just a Diamond preaching it.

I do certainly think Pink was misguided. She’s very much designed to look like a child. We’re first really introduced to her through Stevonnie, two children, in a sequence where Yellow is portrayed as Connie’s mother while Stevonnie (as Pink) is whining and complaining like a petulant child. That’s intentional for a lot of reasons, it puts us in the mind to understand both her more childish actions and understand that she really isn’t respected by the other Diamonds which makes it that much harder for her to get them to understand and she was likely very intimidated to even try, as children often are. “Rose Quartz shattered Pink” was kind of the “dog ate my homework” of an excuse, trying to deflect blame, duck out of responsibility, but often motivated by anxiety and fear and the belief that the real reason they don’t have their homework will be met with anger or dismissive disappointment. It comes from feeling powerless in a way that’s very specific to childhood, I think.

Blue told Pink that “As long as you’re there to rule, this colony will be completed” and ran with it, even though with mature thought one could understand she didn’t literally mean if Pink were removed everything would just be fine. Pink absolutely severely underestimated how much Blue and Yellow cared about her and how enraged they’d be at her shattering. I don’t think Pink was entirely naive about the horrors of war, though. It seems most likely that the memory at the end of “Rose’s Scabbard” takes place shortly before Pink’s “shattering” and Rose was very serious in it. But I think she certainly didn’t expect them to be as upset as they were. Rose seemed to know to shield against the Diamond’s attack, so it seems like Pink knew they were capable of doing that but perhaps thought they’d never actually do it (or, maybe, thought they wouldn’t be able to if she weren’t there?)

Though it’s also worth mentioning that Pink wasn’t just ducking responsibility. If she truly just wanted to run away from her problems, she could’ve had Pearl take the blame for the shattering or had Pearl disguise herself as some other unrelated Gem. But she specifically had Rose Quartz be the one who “shattered” Pink Diamond, likely with the belief that she’d bear the brunt of the consequences (and she kind of did, but mostly now as Steven). So even if some of her motivations were selfish or misguided, she wasn’t just trying to do what was best for her. I’d say she mostly just severely underestimated how much collateral damage would happen to everyone else around her.

I think gagging Pearl was ultimately harmful to her, but I don’t think Pink had malicious intentions at all with it, honestly she was probably trying to be kind (but also a little selfish, too). It’s easier to keep a secret if you literally cannot tell it (and so Pearl could talk as much as she wanted without worrying she’d accidentally blurt it out, since she literally couldn’t). I’d also wager some motivation might have been that if the rebellion failed and/or Pearl was captured, she couldn’t be forced to tell under interrogation and, perhaps, the physical restriction might’ve been an indicator that she was a Diamond’s Pearl and of course couldn’t be involve or, perhaps, that she was ordered by a Gem to be a rebel and thus wasn’t responsible for her actions. Those are just guesses, though, I’m just saying that while I think the gag order did hurt Pearl a lot in the long run, I don’t see it as a purely, intentionally malicious and selfish act

Here’s another important thing, too, the rebellion is often referred to as failed, both in the show and in the fandom, but it wasn’t really, not completely. The Crystal Gems were obliterated, yes, which is really bad, it failed on that front. But had they not driven Homeworld off the planet, all life on Earth would be gone. They would’ve bled Earth dry of its resources and moved on to another planet. All the sacrifices of the Crystal Gems did accomplish the very first point on the manifesto and while that doesn’t mitigate the pain and suffering that ensued, it’s still an important fact to remember.

Of course, you can have good motivations and do your best to do the right thing, but still really hurt people. You can still have, in addition to that, bad or selfish motivations. You can still make big mistakes. Pink was afraid to be honest with people, the Diamonds, her fellow Crystal Gems, even Pearl (the person she was closest with) and it got her bogged down in so many lies and secrets she was inevitably going to hurt everyone eventually.