#this was born from my love of this narrative structure

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hear me out: the story of svsss but with the structure of mdzs and tgcf.

What do I mean with that? Well, both mdzs and tgcf have these two timelines throughout the story, of what happened in the past and what is happening in the present. In mdzs the past is a little more interspersed throughout the narrative, while tgcf has more of a clear-cut divide, but both do it in some way.

What if svsss was written the same way? After all, we already have a time jump through SQQ's death. The story could start with him in the mushroom body, trying to keep himself away from LBH (and failing miserably), but what happened between the two wouldn't be revealed until later.

SQQ's status as a transmigrator would be stated, and also the original plot of PIDW, so the reader would know how the story was supposed to go. But we see from the beginning of this version that this is a completely different situation, and we'd wonder: what exactly happened to change PIDW this much?

Did SQQ not push LBH in the abyss after all? Did something else happen? But if he did push him in, why is LBH still so obsessed with SQQ, to the point of keeping his body? And how did SQQ die? We know the original goods was tortured, but this SQQ hasn't, yet he still died in some way. Did LBH kill him?

Of course, SQQ using the mushroom body would have to be extended, because he used it for such a small amount of time before jumping back to the SQQ body. The mysteries would have to be laid out for the reader before that, so when TLJ comes into the picture, the reader gets to discover the truth with SQQ.

#this was born from my love of this narrative structure#i love when the characters know what happened in the past but they don't tell the reader#and the reader has to slowly uncover all the mysteries while reading the whole story#it's wonderful#and you also get to reread knowing all the answers!#which makes it a whole different experience#svsss#scum villain#mdzs#tgcf

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Secret of Us and the allegory of the puzzle...

I think one of the major overarching themes in this series is that you cannot force something to fit where it doesn't want to belong. And the only way to 'complete' the picture, ideally, is to patiently allow the pieces to be put together in the way they're supposed to.

I really really want to talk about Lada and how much I resonated with her as a character. In order for me to do that, I have to explain some cultural insights that revolve around Lada's familial structure.

Funnily enough, I was recently discussing certain matrilineal cultures that exist in Thailand and how they perpetuate a lot of bigoted ideals... and that is shown beautifully in Lada's relationship with her parents and how they each react to her queerness. To me, it seemed clear that Lada's parents' marriage was born from matrilocal customs. And unfortunately, that's not really something you would be able to pick up on if you weren't Thai (or natively Asian in general). So... in these types of families, women hold a lot of authority, and that authority is passed on through the female line (which is why daughters are valued over sons). The wife would manage and have the final say regarding household matters, including how the children are raised... and the husband's duty would be to respect his wife. A mother and her daughter maintain a continuous relationship with one another as, should the daughter marry, her husband would come to stay with them until they have a family of their own (and sometimes even after). It's a good way to strengthen matrilineal kinship, but it puts enormous cultural pressure on the daughter who is raised with very high expectations... the most pressuring of which is to marry a man and to have natural born children. Should the daughter not 'fit' this mold, they are often ostracized from the family.

It gives new meaning to hearing Khun Russamee say, "Lada is the seed I've nurtured since birth," doesn't it? It's why she is so against accepting and understanding Lada and Earn's relationship. Because in her mind, there doesn't exist a future where two women can uphold these matrilineal customs... and so the only reason Earn must be pursuing Lada is for some form of exploitation (i.e. money). She justifies her cruel and queerphobic behavior to keep them apart as some form of misaligned protection of her daughter and her daughter's future... to keep her from being taken advantage of and to help her see reason. It doesn't excuse the behavior at all... but at least you can understand the motivation (no matter how terrible). These types of mothers exist in the reality of Thai society... it's not just some cliched villain narrative. I'm speaking from experience here (NOT MY MOM! I LOVE MY MOM... my mother's mother).

In Thailand, we hold strong to the notion of บุญคุณ ('bunkhun'). This notion perpetuates the idea that we owe an endless debt of gratitude to our parents. It's seen as our "moral obligation". (Similar ideas exist in other Asian countries, as well)

Lada has done everything right. She's loved and obeyed her mother, she's cultivated a successful career with intentions to take over from her parents' leadership of the hospital, she's set herself up to be able to support her family's needs... She cannot imagine a life where her mother could ever not support her or her choices. Her one "fault" is that she is in love with a woman and refuses to conform to her mother's insistent heteronormative intentions (I loved the juxtaposition of this against P'Nu's defeated acceptance btw). She's rightfully exhausted from all the pressure to 'fit' her mother's mold of the perfect daughter, and Earn recognizes that.

So when her mother falls ill, and Lada is expected to take responsibility, it makes sense from the perspective of her familial structure. When she sacrifices her happiness for her mother and Earn understands the reasons why... it makes sense. Khun Russamee only comes to believe that Earn truly does love Lada once Earn willingly steps away from their relationship to ease Lada's mother's expectations... it's twisted, but it makes sense. And Khun Russamee does apologize, for whatever the frik that's worth (I can only try so much guys 😞😞😞) It's just part of our ingrained culture to value family despite their abusive behaviors. And as much as I wish that weren't the case, these views remain an actual reality. So, it isn't dishonest to portray them.

...The point is, the final pieces of the puzzle could only come together once they were allowed to. And then we finally got our happy ending!!!

Could certain story elements stand to be improved? Yes... but they're no worse than anything we've seen from BL series. And I do believe as time goes on, with more and more GL content being made, the writing will get better and stronger (I hope 🤞🏾🤞🏾🤞🏾).

Despite the more problematic writing, Lingling and Orm were outstanding in their roles. Never have I seen two artists, in all of the Thai QL I've watched, be so in tune to their characters and their emotions. Everything from their dramatic scenes to their more subtle facial expressions were completely on point. It was a pleasure to witness... and the biggest draw for me as a viewer. Well done!!!

#the secret of us the series#the secret of us#thai culture#ladaearn#earnlada#lingorm#lingling kwong#orm kornnaphat#talk thai to me#koda watches gl

288 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi meruz please tell me all your thoughts on outer wilds I am absolutely Living rn

HI oh my god i have so many thoughts. I think I'm gonna keep posting fanart so this definitely isnt gonna be my last word on the matter but wow what a game! um... idk if I wanna just type forever but I can give you at least a few key thoughts I had...

It took me a second to get into! I had been waiting for the switch port so I was really excited starting out but there were a couple early play sessions months apart where I was struggling with the controls and overwhelmed with the openness...I have a hard time with a lot of open worlds games because I just..dont have a lot of free time LOL. But I was complaining abt this to my brother and he was also having a hard time rly digging into the game so when he flew over to visit me a couple weeks ago I was like ok lets do this together (incentivizing gaming by making it social/co-operative). And we had a blast!!! it rly is the type of game you can play as co-op just by having someone else on the couch or on stream doin the thinking alongside you or bouncing theories off of. I do think he's a much better puzzle solver than me though lol (he works in research, so he's got that researcher brain), he made a lot of the leaps of logic way early while I was still turning things over in my head lmao.... AND he's better with the controls because he plays a lot of flight sims?! i think he got annoyed watching me bumble around anytime i had the controller. my sole contribution was doing the stealthy parts in the dlc because im stupid and consequentially lack fear.

I kind of grew up playing majoras mask and windwaker like that was the era of zelda games I was rly activated and engaged for as a kid and I didn't realize how much I was missing and craving that type of experience again LOL. I think especially with how I personally felt that tears of the kingdom was narratively and structurally a step down from botw... idk... i mean you can tell from interviews abt Outer Wilds that the devs clearly have a lot of affection for and thoughts abt the Zelda series as well and I think Outer Wilds was like such a good encapsulation of everything I loved abt those games and also everything I wish they would do lol!! IT ALSO kind of solved a lot of my pain points with open world games and did it in a way that was so elegant... like I think i initially recoiled at the openness but then when i started exploring and realized the scope and level of detail it rly clicked into place.. im just in awe.

umm i love every hearthian they were all so charming. it rly did feel like an older school of nintendo rpg where every npc has so much personality lol. i loved that every alien race in the game was some weird animal like the designs for all of them were rly good. i love that it was a "worn" universe and that everything looked old or used. I love astronomy and space and space concepts but I don't really like really lofty and impersonal/minimalist scifi so i feel like this was a great and accessible art direction for me personally. i especially thought the backpacking/outerdoorsy aesthetic was really inspired! I think "exploration" sometimes exists on a spectrum where one end of it can be really colonialist/militaristic LOL... UM which im not like. fully against i think it can be an interesting idea to dissect? but i feel like we see it a lot and it was neat to see this which felt like the complete opposite end of that spectrum. weirdly enough playing Outer Wilds made me immediately go and finally finish Firewatch right after but I felt a little spoiled I was like ehh..that was good but it wasn't Outer Wilds LOL.

i think a lot of the themes reminded me of lord of the rings/tolkien lore LOL IDK. I GUESS THIS IS LIKE BIG SPOILERS SO if you havent played dont read but like. the entire concept of being born at the end of a great and enormous world/age with a rich history and you only getting to see the end of it, living in the shadow of great civilization...keeping your humble home in your heart idk. but then also the new world being a song ... I'm a sucker. I love it.

yeah sorry only compliments. anyways yeah i want to do more fanart... soon!! hopefully!

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wait what?! There's a theory that Sansa said 'you know nothing Jon Snow' in their childhood? 🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣

This is an example of how these shippers just don't care about the context of that phrase and it's narrative importance to Jon Snow as a character and his arc of leadership. There's an actual reason for why Ygritte says that to Jon Snow! Why would Sansa say that to Jon?! What is happening?

It's like when they see quotes like 'You should look behind you, Lord Snow. The moon has kissed you and etched your shadow upon the ice twenty feet tall." or 'The white wolf raced through a black wood, beneath a pale cliff as tall as the sky. The moon ran with him' and it connects to the Moon symbology for both Dany and Arya and they want something similar for Sansa and they do this:

Like they just cut the sentence and took the first word of that sentence and attach it to the preceding sentence 🤣🤣🤣🤣

Also sun and son?! 🤣🤣🤣🤣

Like no need for meaning and sentence structure and all that - we will just take this word from here and put it together with that word from there and voila! Jonsa happens.

It's the same with 'You know Nothing'.

Let us read this paragraph both ways.

First, assuming this is the way it's meant to be read:

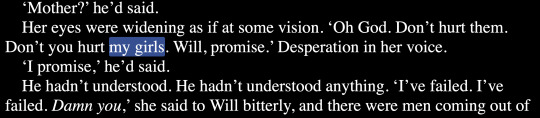

The Night's Watch takes no part. He closed his fist and opened it again. What you propose is nothing less than treason. He thought of Robb, with snowflakes melting in his hair. Kill the boy and let the man be born. He thought of Bran, clambering up a tower wall, agile as a monkey. Of Rickon's breathless laughter. Of Sansa, brushing out Lady's coat and singing to herself. You know nothing, Jon Snow. He thought of Arya, her hair as tangled as a bird's nest. I made him a warm cloak from the skins of the six whores who came with him to Winterfell … I want my bride back … I want my bride back … I want my bride back … "I think we had best change the plan," Jon Snow said. - Jon, ADwD

He nearly committed treason by running away to help for Robb, came back and decided that his place was at the Wall as a brother of the NW. Hence the first phrase.

Kill the boy and let the man be born - a man puts his duties above family and time and again Jon has chosen the Watch over his family - Bran, Rickon and Sansa.

You know nothing Jon Snow - If this phrase connects to any Stark it's Arya because Jon actually compares Ygritte to Arya several times, right from their tangled messy hair.

Secondly the phrase could play into his conflict of love or duty. It's a hard decision and one he cannot make easily. Is it right? Is it wrong? He doesn't know! What about his oaths and the threat from beyond the Wall? But then what about Arya being hunted by the likes of Ramsay Bolton? - 'You know nothing Jon Snow'

It's also the rule of three as he goes down the list - Jon chose NW over Robb, Jon chose the NW over family and now the third option - he chose Arya over the NW.

And Jonsa shippers know it makes no sense for their Jonsa nonsense when the whole paragraph is read hence why they selectively copy and paste only this sentence. Notice how it always starts at the end of Jon grouping Bran, Rickon and Sansa together:

Of Sansa, brushing out Lady's coat and singing to herself. You know nothing, Jon Snow.

And taken out of context it makes no sense - 'Of Sansa' - what does it mean 'Of Sansa'? Because there is preceding text there that they just omit because it doesn't go with their 'theories'.

If you are going to attach 'You know nothing Jon Snow' to Sansa, then you have to do it for Bran and Rickon as well. Like so:

He closed his fist and opened it again. What you propose is nothing less than treason. He thought of Robb, with snowflakes melting in his hair. Kill the boy and let the man be born. He thought of Bran, clambering up a tower wall, agile as a monkey. Of Rickon's breathless laughter. Of Sansa, brushing out Lady's coat and singing to herself. You know nothing, Jon Snow. He thought of Arya, her hair as tangled as a bird's nest. I made him a warm cloak from the skins of the six whores who came with him to Winterfell … I want my bride back … I want my bride back … I want my bride back … "I think we had best change the plan," Jon Snow said. - Jon, ADwD

So even reading it this way - 'You know nothing Jon Snow' is about family, about Bran, Rickon and Sansa.

In which case:

'kill the boy and let the man be born' - when he abandoned Robb.

'You know nothing Jon Snow' when he abandoned Ygritte and equating this to how he has always put the NW above family.

'I want my bride back...I want my bride back...I want my bride back' - the reference to Arya as Ramsay's bride, he snaps at this point and we get the amazing 'We had the best change the plan' line from Jon Snow.

Again rule of three: NW vs love - Jon chose NW, NW vs love - Jon chose NW, and finally NW vs love, Jon chose love. Because yes, he does decide differently between Ygritte and Arya.

So any which way one reads that paragraph, 'You know nothing' is either connected to Arya or it's connected to Bran, Rickon and Sansa. So no, it's not a 'Jonsa related quote' lol.

'You know nothing Jon Snow' is not some phrase just connected to Ygritte for shipping reasons. It has meaning and weight behind it, it's about Jon's decisions as a leader and it increasingly comes into play in ADwD because leadership is hard and Jon is always having to make choices, of making the unpopular but right decisions and is increasingly confronted by the knowledge that yes, he does have a lot to learn and needs the advice of wiser folks like Maester Aemon, Donal Noye, Qhorin Halfhand and Samwell Tarly.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

OK, I was going to reblog this excellent post by @luckshiptoshore so go read it, because yes. Yes!! YES!!! But then when I got started my post got super long and I felt bad tacking it onto her post and decided to make my own in response to these tags:

#i am actually a bit obsessed by the whole hunting as queerness metaphor#it’s so clearly something everyone involved in the show is thinking about#supernatural

Gurl, me too! Like go back to the start! By the time Supernatural began, the backlash against the Joseph Campbell Monomyth-style mode of storytelling had already begun in the hallowed halls of USC film school, and yo: I was there at the time of Kripke's graduation, and my best friends from college are full scale big giant time filmmakers now, whose names I will not share on main because it's uncool, and I don't want that attention, but... yeah. I am referencing FIRST HAND SOURCES on this.

But, for a real source? The Oxford English Dictionary places the first use of the term "Queer Theory" in 1990, with Queer Studies as an option in the academy by 1992. I know the kids think it's a new-fangled thing, but Kripke graduated USC in 1996 (I graduated in 1995) and it was ALL THE RAGE by then. My friends read queer theory in their Critical Studies courses in the Film School, I read it in the College of Humanities getting my degree in Literature. By that time, you could not get through that school with any degree in any non-STEM subject without knowing about ye olde postmodern lenses, queer and feminist theory, and without knowing how to employ those lenses.

Queer refers to sexuality, yes, but the word's earliest use (again, according to the OED) is in the 1500's, meaning: strange, odd, peculiar, eccentric. Also: of questionable character; suspicious, dubious.

So, ok, in 2005, Enter Supernatural, episode 1:

Presented? Two brothers. One actively seeking credit in the straight world that is not available to him in the bosom of his family: Stanford, law school, hot co-ed girlfriend, the other bound to his fractured, wounded family by duty, yes, but also by love, living on the fringe, alone, fighting monsters, and chasing after his father's approval, and who has long since given up any dream of being 'normal'. Episode 1 presents Sam's call to adventure, which he refuses when it's just familial duty, honor and love calling him, but accepts when the show takes a very straightforward and very telling path by classically fridging his woman. Ok, now he's on board. Like John, whose motivation is another dead woman, his motivation is revenge. So far so straight!

Dean though: he's different. He is already on the adventure and he was not 'called' or given the option of accepting or refusing because he had no agency when his feet were set upon this road. He does not fit the straight world at all, because he is cobbled together out of love, duty, deep guilt, striving, desperation and fear. This is who he is now, in some elemental, incontrovertible way. It was not a choice for him, he was born to it. His mother is dead, and we later learn, she made the choices that brought them all to this fate. Dean remembers her idyllically, but he is not motivated by revenge, more than any other thing, he wants to be worthy. He wants his father's approval, his brother's love.

Enter Supernatural's main theme: fucked up relationships between men enmeshed in patriarchy, which will eventually expand to include fucking GOD HIMSELF.

And like, there are SO MANY CLEAR STEPS ALONG THE ROAD in season one, and I am not even talking about sexuality and gender here, but there is SO MUCH TO SAY about it in season 1. But I am not talking about that -- I am talking at a structural, narrative level, the whole thing is just fucking all the way queered, yo.

The big climax?

At the end of the season, Dean says: "I just want my family back together. You, me, Dad... it's all I have." He is Sam's mother, John's partner! His vulnerability and emotion is feminized and contrasted with Sam and John's more overtly driven by their more masculine/straight heroic revenge quest. John: "Sam and I can get pretty obsessed, but you always take care of this family." Only that's not John talking, it's Azazel, and Dean knows it is because his father would never forgive how soft he is, how he will always choose love and family over revenge. Then, in the end, the show makes a huge point of telegraphing that Sam is finally aligning with Dean by refusing to shoot Azazel because he's possessing John, and Sam just can't do that to Dean.

Sam and Dean are thus bound together and cemented into a marginalised path, living on the road, haunting liminal spaces and cheap motels, confronting the monstrous everyday. Sam is presented as the brains of the operation, he does research, logics his way through things (masculine) while Dean is the heart who acts impulsively and on instinct and intuition (feminine).

It later transpires that Sam has a piece of the monster inside himself, and Dean has to learn to love the monstrous, he has no choice, because Sam is his brother and then Cas... and, and, and!

Like... I could go on and on, citing ENDLESS EXAMPLES. This could be a literal book. Maybe one you need to read with a magnifying glass like my condensed edition of the OED. LIke, the queerness of Supernatural is DIZZYING and MYRIAD.

But basically? FROM THE START, hunting is a queered version of family, and within that, Dean is a queered version of a Campbellian hero. Hunting is a metaphor for otherness and liminality, and that's even before you say a WORD about sex. It starts in deviation from the norms of family, masculinity and expands from there on so many levels both in story and on a meta level. The story is flesh on queer fucking bones.

I'm so sorry, but anyone who thinks queerness was not BAKED INTO Supernatural and more specifically into Dean from DAY 1 has clearly never seen Dean's insane lip gloss in season 1, and vastly underestimates the cultural awareness of people who write shit in Hollywood, and also the other people who put pink lip gloss on pretty boys in Hollywood. Nothing that gets on your screen wasn't a fucking choice made and approved by a LONG LIST of people who know what they are about.

#supernatural#dean winchester#sam winchester#the queerness is baked in from the word go#like...OBVIOUSLY#and transparently

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

2025 Book Review #5 Daisy Jones and the Six by Taylor Jenkins Reid

This was a book recommended by a friend an absolute eternity ago which I finally got around to reading, having long since forgotten any of its selling points or interesting qualities which might have accompanied the recommendation. Going in blind, I quite enjoyed the book as I read it, finished it feeling it had ended somewhat anticlimactically, and have grown a bit more sour on it as I thought about it to write this review. It’s not a bad book – still a fun, easy read! - but I’m not sure it’s really much more than that.

The book is structured as an oral history – or maybe the transcript of a documentary – about the titular band, a musical phenomenon that set the world on fire for a moment in the late ‘70s before dramatically breaking up halfway through the tour after releasing one of the best albums of the decade. Aside from bits of narration and scene-setting at the start of each chapter (and one conversation in the climax) the documentarian is invisible, and the story is entirely told through quotes from members of the band, associates and hangers-on, or just critics and writers on the period, as they’re interviewed thirty years and change later in the 2010s.

In the abstract, I adore this. I love unreliable narration, and Rashmoon-esque scenes where we get mutually exclusive versions of the same conflict from different perspective. Properly packaged, I am an incredibly easy mark for messy self-destructive codependency and melodrama. Thanks to some peculiar media taste on my parent’s part, I even have enduring fondness for the whole, I don’t know, heroic age of rock&roll? And the whole mass of accompanying narratives and tropes that you get buried in talking about music in the 60s-through-early-80s. And it’s not that the book doesn’t deliver on any of that, exactly – it’s not at all poorly executed, it knows what it’s trying to do. It’s just-

It feels like this is a book about a fictional band because it would be impossible to make such a morally simple, happy and redemptive story about any of the actual bands that clearly inspired it without seeming like Jenkins was getting paid to whitewash someone. It’s not that there isn’t mess, exactly, but it comes across like a born again Christian giving lurid descriptions of their debauched and sinful former life. There’s sex and drugs galore, but the worst person in the entire book is just a shitty deadbeat boyfriend. The entire main thrust of the book is building up an unacknowledged love triangle between Daisy, Billie and Camilla – actually quite compelling! And then it finally reaches a head, is cleanly and simply resolved in the most boringly conventional way, and the story jumps thirty years ahead to a ‘where are they now’. Where is the toxicity, the mess, the unforgivable betrayals everyone has to ignore so they can get on stage together, the fortune-destroying legal battles over the rights to the band’s legacy once it all falls apart? You finish the book feeling like Charlie Brown trying to kick a football.

This might be a problem of me setting my expectations too high, but up until the halfway point it does feel like it was building up to something appropriately nuclear. Instead, it peaked with Billie (and, despite the book’s name and cover art, in a narrative sense he really is the main character of the book) hits rock bottom and goes to rehab so he can be a good father for his daughters and husband to his wife. A truly mind-numbing fraction of the book from there is dedicated to singing the praises of the redemptive power of the reproductive nuclear family and an advertisement for going to rehab and learning self-control before drugs ruin your life. I spent two hundred pages waiting for it all to be groundwork for juicy, bitter dramatic irony, but no – just sincere, straightforward themes of the work. Hideous.

There is one rather hostile reading of the book that works? It’s revealed at the book’s climax that the diegetic framer and compiler of this oral history is Julia, Billie and Camilla’s daughter, and she is creating this project when her mother rather abruptly dies. And you know? This story is exactly what you might expect from an entertainment industry nepo baby asking her parents and a bunch of family friends (including who everyone assumed to be The Other Woman) about her parent’s romance and relationship and putting it all together into a deeply mediocre documentary that will kickstart her career entirely thanks to all the juicy stories from last generation’s superstars. But I am on the one hand really pretty sure this is not even close to the intended read of the story, and on the other still leaves you only reading the deeply mediocre documentary with no access whatsoever to the more interesting story underneath it. Decent conceit for fanfiction, I guess?

The identity of the diegetic narrator is also the justification for how shamelessly the story plays favourites with which band members to focus on – of course her parents and their relationship will be the central focus of the whole piece, of course her uncle and his girlfriend will get second-string status, of course the rest of the band will basically exist to provide colour commentary and throw peanuts (if that). A disparity the story itself draws enough attention to it, honestly, goes from charming to eyeroll inducing when it never actually does anything with it.

The story very much wants to be About gender and feminism, and (going by the discussion questions I glanced at while skimming through the reader’s guide section at the back of the book) is proud of it. Which isn’t really unjustified – it really does have a decent number of different female characters with their own developed personalities and prominent roles in the narrative. It does the thing I kind of hate where by happy coincidence all of them (even the ones on opposite ends of a romantic triangle) end up liking each other whenever they interact, but that’s just kind of a piece with the book not really letting anyone be a proper piece of shit. It is however very funny that the only black-coded character in the entire story is literally in the narrative to be Daisy’s longsuffering and supportive best friend there to provide a bit of maternal influence and talk sense into her when she really needs it.

But yes, decent airport read I suppose? Fun for a lazy day if you enjoy the premise, but not really worth seeking out otherwise.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

They presented the possibility of older women--who were repeatedly described as "covenless witches" in a story that also repeatedly told us a witch needs a coven--finding community again and a new reason to live in each other and their own power and then "subverted our expectations" with these women dying to serve a male character's story.

That was the point of their stories. Him.

It isn't common for older women in US pop culture to get depicted as people who are capable of rebirth. Of lives, desires, hopes and dreams that matter beyond solely being a mother. It rarely happens, and it didn't happen here.

It's rare for stories to deal metaphorically with real things - like women who get clean or make positive change in their 40s or 50s. Women who find each other and aren't alone and "forgotten" anymore. These things happen -- yes, sisterhood is sometimes a lie and sometimes "people never change." Sure, those things happen. But sometimes sisterhood isn't a lie; sometimes people make change in their lives.

You don't see these stories when they're women though, especially not older women, especially not gay women.

I'm glad for Jen. She doesn't have a community, though. A witch needs a coven they told us, over and over again. They showed us them getting one small taste of the joy they could share together, in their scene of flight. But that was just for Billy too. And now everyone else is dead. To serve the male character's journey, give him some angst.

Agatha is forever spiritually dead--not experiencing any kind of emotional breakthrough or change--because she's not the lead, so she's static so she can serve as a device within the true lead's journey.

She can't even be allowed the growth I pictured as the worst case scenario - where she dies for *the coven*--so they can live and have community and spiritual rebirth together--and makes enough peace to go with Rio. She doesn't even get that much, to get to have a real death that matters and has a sense of completion to it, where we can imagine her reunited with her child and/or at peace with Rio. She can't have that because she has to be Billy's amusing sidekick, his Jarvis, his moral warning lesson about his powers and the witches he got killed and his angst. Because his story matters and theirs didn't.

I was talking to a friend the other day about how love stories often have a "point of symbolic death, when all hope seems lost" (concept from Pamela Regis's study of romance novel structure) and with mf couples they get to rise again from that, into rebirth, into new life. Ff canon couples in stories often, due to a bunch of reasons, aren't allowed that narrative power. They remain trapped in tragedy and despair. I thought surely Agatha herself though, as the lead character, would get to have some kind of change or rebirth as part of a community of women, given that her core wound is betrayal by community -- but she, as a character, doesn't get to go into the symbolic underworld and change and be reborn, because she was never the lead character to begin with.

Sapphic love remains broken once it breaks, the "point of symbolic death" is literal death or a shattering end, there is no rebirth. We, I guess, lack the symbolic potency to come back, in the eyes of the world? We are not generative. "Which one's the man?" "How do they even have sex?" "Your marriage isn't real because you can't make babies." (Kudos for subverting that one, though, show! Except... a child born of women, without a man, cannot live a full life I guess?) And specifically, as a 30something queer woman, people who call my wife, after I've described her as my wife, my "girlfriend" and are shocked by how long we've been together. That we're grown women and our commitment is right down to the bone, that it has blood in its veins. We are not little girls playing dress up. But that is how a ton of nice people see us; we exist but we are spiritually empty, lacking potency. And the stories reflect that. That energy, that core belief that we are the juvenile, non-generative form of love and relationships. And this woman too, she remains in a kind of eternal spiritual death.

That's why people are mentioning the Hayes Code, they're feeling how that aligns with larger cultural prejudice against us and our humanity and capacity to have the kind of power of living and loving that is ascribed to mf love and that more (though not always, misogyny is a hell of a thing) straight women get in stories.

The idea that it's GOOD for a story to do this, because "sometimes sisterhood is a lie" and "sometimes people don't change" ignores that context of who precisely this narrative "subversion," this spiritual aridity is given to. And who gets to live and grow and be reborn and strive and learn and become in stories, to be allowed to connect with the transformative potential inside themselves and each other.

The show did give us a lot -- I think it's important to recognize that. The canon ff love; I would have never expected that. The canon kiss. They put a lot into that and I honor that. This wasn't a classic "bury your gays" and I'm not mad at them. They did their best. A lot of the issues I have are probably due to the problems of the mcu overall and how static it is. But the deeper themes are also just incredibly disappointing to me, and I wanted to outline why.

It's entirely possible to be disappointed but appreciate context and not be unkind to creatives who did their best within overall industry/cultural limitations, which is where I am at and what I mean with this.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on tmagp episode 24

*cough* my sister had a newborn a few months ago. Here’s some red flags about “the health visitor” from today’s episode:

- newborns feed every 2-3 hours, usually 2.5. Idk if this is different in the UK but I don’t see why it would be.

- most babies are born with greyish eyes, which changes over time. If Rupert’s a newborn when she’s talking about his black orb eyes, this is maybe a red flag?

- “I couldn’t scream, I didn’t want to wake him” AHHHHHH oh god the psychological horror of having a newborn aghfjgjfhhhhhh

Very Rosemary’s Baby, but instead of going full satanic panic, “Raising Issues” focuses on the self-sacrificial narrative mothers are told, and how that leads to a dangerous and isolating situation as Patricia ignores every red flag in sight. I had my head in my hands. Honestly, I wish we’d dived deeper into the socioeconomic stuff rather than the body horror because back to back with “A New You” it felt like too similar of a story structure, even though imo they’re meant to be parallels.

23 and 24 have been so similar that they’re definitely intentional contrasts to each other. One’s from Chester talking about how you can long to change yourself so fully only for it to all go wrong, and this one’s from Norris about destroying yourself to support the one you love… I am ill, actually. Screaming crying relistening to the last recording in this case file and finding all the points that are reminiscent of Mag 170 (Recollection).

These lines specifically are making me think. Once again, I am ill.

Chester: “Alesis Newman is leaving this world and whatever comes next – though she may look like me in some ways, though she may carry a part of me with her – she’ll be better. Free of all my mistakes. Perhaps people will like her more than me. I already like her more than me. I want to see her walk off happy and strong. I hope she doesn’t feel this now, just be the good parts of me. (hoarse) I hope it’s like I dreamt, I hope she has my eyes…”

Norris: “I can’t remember when… when I last… had sleep. I think… I think days…” + “I don’t know what’s going to happen. There’s not much of me left. I’m so scared. But at least Rupey’s happy…”

Considering this is the first Norris case file in over 10 episodes (since episode 12, unless I’m wrong) and he’s literally just reading the stuff between recordings, I’m a bit concerned.

Who the fuck is reading this statement and why didn’t they mention it to Celia IMMEDIATELY? If it was Sam, he knows she has a kid and is in a support group, and if it was Celia herself, then idk why she isn’t at least concerned (that’s suspicious, Celia.) I guess Gwen and Alice don’t know about Jack, so they’re off the hook.

ALSO rupert? A red name? Philosopher’s stone alchemical reference? Or just referring to the blood he’s feeding on?

I know I’m gonna see a ton of takes on this episode being like “this is why I’m childfree” and, like yeah, I’m not planning on kids either but this story is such an extension of existing social structures that I hope we talk, at least a little, about the social narratives at work here about pregnancy, parenthood, and childcare.

#the magnus protocol#tmagp#tmagp spoilers#tmagp 24#celia ripley#tmagp chester#tmagp norris#tmagp episode breakdowns

123 notes

·

View notes

Note

On one of the previous asks about Snape Versus James you said James 'chose not to be functional' when James canonically improved as a person whereas Snape bullied way into his adulthood. Of course, we don't know James wouldn't have, but considering he stopped hexing people in corridors and Lily fell in love with him despite hating him before I think it's fair to say James DID improve whereas Snape really didn't...

I also think the class argument can be used to a certain extent. James presumably grew up in a world where his blood status gave him power, but was not prejudiced whereas Snape was born with a lower blood status and likely faced discrimination from it (ie Bellatrix's distaste for half-bloods) and yet still embraced those views even into his adulthood (treatment of hermione)

Idk I'm not totally fond of James but I can't help but think you're being a bit unfair

Your argument overlooks several key points that complicate the simple narrative of “redemption” in James’s character. First, using Lily’s eventual affection as evidence of James’s moral transformation is problematic. It implies that a woman’s validation is the ultimate marker of a man’s improvement—a perspective that is inherently misogynistic. Genuine maturity should be measured by an internal commitment to change, not by external validation from romantic interest. After all, James continued to badmouth and bully Severus behind Lily’s back, which hardly aligns with the image of a reformed, mature individual.

Moreover, we must consider the profound impact of class and privilege. James was born into a wealthy, aristocratic family—a background that provided him with extensive social and cultural capital, as Pierre Bourdieu would argue. This advantage means that he had the support systems, resources, and a safety net that allowed him to navigate his missteps with far less consequence than someone like Severus. Academic studies, such as Annette Lareau’s Unequal Childhoods show how children from privileged backgrounds are often raised in environments that normalize and even excuse certain behaviors that would be harshly judged in less advantaged settings.

In contrast, Severus’s behavior must be understood in the context of his troubled, disadvantaged upbringing—a life marked by poverty, violence, and a lack of supportive resources. His struggles and the environment he was forced to endure shaped him in ways that make direct comparisons with James both unfair and overly simplistic. Expecting Snape to adhere to the same behavioral standards as someone who had every structural advantage is to ignore the sociological reality that class significantly influences one’s ability to “improve” or even just behave in a socially accepted manner.

Ultimately, comparing James and Snape based solely on a surface-level reading of their actions not only misses the deeper nuances of their characters but also reinforces a flawed understanding of morality. It’s not enough to note that James stopped hexing people or that Lily eventually chose him; true change should be evident in consistent, principled behavior—and in that regard, his continued mistreatment of Severus and reliance on his inherent privileges suggest that his “redemption” might be more a product of circumstance than genuine personal growth.

Or, to sum it up for you better, let me tell you something my grandfather once told me, which is basically the foundation of my entire argument:

It’s very easy not to steal when you’re not starving.

#severus snape#pro severus snape#severus snape fandom#severus snape defense#pro snape#james potter#james potter was a bully#james potter was a privileged prick#Lily evans#Lily evans potter#Lily potter#classism#class analysis#Harry potter meta#meta

47 notes

·

View notes

Note

You said you prefer Nikolai and Alina more as a ship but wouldn't that still end up with Alina being in a place or position she never wanted? Alina doesn't like the responsibility of being a ruler and being involved in politics but she'll have to do all of that if she married Nikolai so wouldn't that end up in her being bitter and unhappy too? She already found his manipulative skills disturbing in s&s and they'd only known each other for a few weeks I think? Of all the men in her life, Nikolai is the one whom she's affected by the least. Idk but I like the idea of them together but I just don't see how they could be endgame.

Well, to some degree, it’s a matter of how you interpret the text. Nikolina works best for me as a narrative culmination of Alina’s arc, as a middle ground between what Mal represents for her (safety in the familiar; regression) vs what the Darkling represents (the corruption inherent to power; terrifying unknowns). I’ve said before, but I like the sort of uncertain idealism Nikolina signals, trying your best and hoping it works out, etc

Then it becomes a question of how you read Alina’s feelings about any of these things

Alina’s narration states that she basically can’t be happy in any situation except one where she’s left alone with Mal, but then textually she’s practically always upset when interacting with him, and in his behavior, meanwhile, it feels like his love and respect for her is pretty conditional and that he cannot be happy in a situation where she has more power and importance than he does. Personally, I would say that relationship reads more like something she clings to because she’s afraid of change, and because, for most of the trilogy, it represents an idyllic, simple vision of her life that is framed as entirely out of reach to her. Her being unable to accept anything else feels like a rejection of both like painful realities for her, but also growth

That isn’t to say that the counterpoint is that embracing growth would look like loving court politics and a royal life for her, but there is a degree to which her discomfort with it feels more like being unable to move on from that particular, unattainable vision

It, incidentally, goes hand in hand with the Darkling’s only acceptable vision of happiness for himself being complete control over an unattainable ideal of a Sun Summoner. One who will affirm all of his choices, and somehow emotionally fulfill him in every way. Alina, in being a person, has already guaranteed his dissatisfaction

These both read like standards that will simply never be met! And so the natural conclusion to a positive arc, in my opinion, would look like coming back to earth and discovering what kind of happiness actually exists and is sustainable for her. Where, the Darkling, as her dark (lol) mirror self, essentially, and the realization of the worst case scenario for her, is simply doomed to self destruct— which he does! Spectacularly!

Alina, frankly, reads clinically depressed to me. I’m not convinced there are many circumstances where she could be unambiguously happy all the time. But I do think that ties into the theme I am thinking of, about like building obtainable and realistic happiness for oneself

Meanwhile, beyond Alina’s stated single scenario for happiness, in the first book’s initial, chosen one, wish fulfillment fantasy, that’s later turned on its head, I think there’s a sneakier, and even more impossible standard of happiness for her where the Darkling is simply… not who he is as a person. One where he does not betray her and does not require her complete subjugation in order to coexist with her. In the core structure and concept of the book, in the Darkling functioning as a character, her ultimate wish fulfillment must be one where he isn’t so cruel

And I think Nikolai does actually represent a more realistic version of that

Nikolai is basically introduced in the trilogy as like “what if the Darkling was a thousand years younger, born to privilege, and had a sense of humor.” He functions as a direct foil and a more accessible version of the Darkling’s values that Alina can engage with in order to understand and relate to him more

With that in mind, in a lot of ways, Nikolina is actually a vector with which to engage with Darklina imo?

Anyway, I don’t actually read her as like uniquely perturbed by or unaffected by Nikolai, tbh. The books make a point of how well they get along, and it’s not nothing to me that of her three canonical love interests, he’s the only one she interacts with regularly that doesn’t make her personally miserable

I actually enjoy that their romantic scenes are bolstered by them otherwise liking each other (very low bar 😭) and that the main source of conflict for them is external and circumstantial rather than interpersonal. And the implication of them having achieved a new level of understanding through shared/adjacent trauma after Nikolai is transformed back into himself at the end of the third book, and has escaped the Darkling’s grasp, but with scars— like Alina herself— is a very romantic and poignant concept to me!

Anyway, while I don’t think she’d ever joyfully embrace court life, I also don’t view finding a version of ruling that she can live with as a bad resolution for her

#grishaverse#shadow and bone#nikolina#darklina#step into my office#dark stories of the north#a mysterious stranger has appeared

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Which of the Shirogorov triplets was your favorite, be it to play or from a narrative perspective? (I have a suspicion, but I'd love to hear your thoughts!)

i thought i had an immediate answer to this because jake was the first concept and the one i think about the most, but as i thought about it more i'm less sure. i'll post through it under read more

jack is a bonus character that i came up with very very late after i heard about what maurice did, and i only solidified his concept about 30 minutes before recording ska 49. but i like that he is a strange and somewhat sinister person, because even someone like that was once just a baby for adults to project their dreams onto. and i like his initial role as the promise of found family made troublesomely real, a test of kc and haley's relationship and of kc's apparent motherly concern for naomi. i never really settled into jack's voice and he had no time for development, but in the end he fit well into the theme of intergenerational disappointment.

i think i wasn't assertive enough in book 1 to really make naomi work as an ace detective driving the investigation forward, but their character became clearer to me during burger on the orient express. they feel suffocated by the structure they were born into, but they do need a structure to thrive. i liked naomi more in book 2 as someone reacting to the styles of each new authority figure: overwhelmed by jordan, overreliant on haley, frustrated by kc. and i really liked playing naomi as a shattered husk in the finale. i think naomi is the one i have the clearest voice for.

jake's role as the asshole needed to change fast with the appearance of jordan and balor, so i'm glad that was also a convenient spot for him to take the spotlight (something planned from the beginning, but with no details about when or how) and develop one-on-one relationships with charlie and solo. that is when it became clear to me that jake would be way happier if he just let go of his desire to have any relationship with naomi, and that guided me to the end of ska.

as i said, jake is the one i think about the most. i will listen to shadow the hedgehog songs and make amvs in my head about jake. he has the biggest emotional outbursts and emotionally-motivated stupid behavior, and that is always the most fun to play. so i guess i have wrapped around to my initial gut answer. jake is my favorite shirogorov triplet.

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the writing ask 🖊️ ‼️

🖊️ How does your magic system work?

This is gonna be long lol I did actually have to sit down and work this out. I'm generally not a fan of "hard" magic systems, ie something with rigid rules that cannot be broken, because they feel limiting, or the writer can sometimes accidentally break their own rules and then the reader feels cheated. On the other hand, having a magic system that's too "soft," ie everyone has exactly the magical fix they need whenever they need it, then magic ceases to have any weight and can be used as a band aid for everything.

When it comes to Arthurian Legend, there isn't really a magic system to start with. Merlin just does whatever he wants until he can't. So I gave the universe a little more structure than that while still skirting the definition of any rules. Nobody has a mana limit or anything measurable, but there are limits. I love the balance of Avatar The Last Airbender. Katara's water bending extends to ice, and with special training, blood. It fits within the realm of possibility the narrative set up, manipulating with material of the same element, without breaking the system by suddenly letting her bend an additional element. In Arthurian Legend, and in my works specifically, there are many categories the magic users fall into.

Gods, Power Dependent on Believers' Faith: Ahura Mazda, Simorgh, Apollo, etc.

Creatures, Immortal Unless Slain: White & Red Dragons, Twrch Trwyth, Questing Beast, etc.

Fay, "Immortal" as the Land, Elemental Magic: Vivian, Saraide, Bertilak, etc.

Wizards, Internal Power: Gwydion, Merlin, Gromer, etc.

Giants, Long Life, Strong: Olwen, Ysbaddaden, Galehaut, etc.

Humans, Born "Special": Kay, Gawain, Aglovale, etc.

Otherworld Schooling: Morgan le Fay, Amurfina, Queen of Ireland, Lynette, etc.

Construct/False Fay: Blodeuwedd, Green Knight, etc.

Harnesses Gods, Strong Faith = Strong Power: Lancelot, Galahad, Dindrane, etc.

Harnesses Magical Items: Luned/Ring, Perceval/Ever Bleeding Lance, Arthur/Excalibur, etc.

Just Some Guy: Ragnelle, Elaine, Lamorak, Gaheris, Laurel, most characters, etc.

Generally speaking this is the hierarchy. While Morgan's schooling technically makes her stronger than Gawain, the sun strength is innate, it's not something he has to learn in order to utilize, so he's one level up, closer to the inhuman side of the scale. While Lynette, who learned how to do necromancy, would be above basic Gaheris. Does that make sense?

Magical items are sometimes discovered with unknown origins or powers yet to be determined or magical items can be created by someone with the knowledge to do so. There's a part in book 1 where an item loses it's power after it's maker dies. Arthur explains in book 2 that it's because it was a spell on the object, whereas a higher level caster would have transformed it into something which generates its own power and would have, theoretically, lasted forever. Vivian forged Ban's sword, then reforged it for Lancelot to use, the blade never dulls. Some legendary items can only be activated under certain circumstances, such as Arthur's Excalibur which could only be wielded by him. Some hedge witch could even be commissioned for a charm or helpful little item, like a parchment which can only be read by the recipient or a necklace which encourages infatuation of the wearer. For this reason lots of characters have handy trinkets that don't really constitute "having powers," and serve only to offer quality of life changes in really small stakes. The scale for these items is vast from Tristan's harp with strings which never go out of tune all the way to Arthur's scabbard which prevents the user from bleeding, a spell so powerful that it couldn't be replicated after he lost the first one. In book 2, Gawain mentions the infirmary has bowls of hot water that never cool, floors that are never slippery, and a constant, pleasant breeze so the sick ward never smells stale. Magic is a part of the characters' every day lives and manifests in an infinite number of ways.

I don't know if that makes any sense lol I've put a lot of thought into this and like what I've created. It gives me enough wiggle room to introduce new items as needed while still allowing a semblance of limitations. Agravaine or Gareth are never going to randomly create a magical item, and anyone who can is limited by themselves, or their faith. It's a skill-based aspect, which I think can be said for most magic systems and can often be rushed with savant type characters. It also eats away the body. While someone old as Merlin may be able to sustain innumerable small spells all at once while also covering the entire battle field with mist all while in disguise as a child, Gromer has to pick and choose what he's doing or he'll not only hurt himself, but dry up the well and be unable to tap into that magic again until he's recharged. There's no way to quantify what that looks like, its an individual matter. Think of Excalibur (1981), when Merlin transformed Uther into Gorlois and allowed him to cross the way on the mists. Merlin said he had to rest for nine months afterward, conveniently waking up to retrieve baby Arthur. Did Merlin know how long he would have to rest after that? Who knows! But I'm adopting a similar idea. Sure, some characters are performing miracles, but if Lancelot goes mad after, well, that's on him. Aim lower.

!! What has stayed consistent across all drafts?

Ragnelle is in every book. RIP to authors who incorporate the Wedding story and then disappear her from the narrative after that but I'm different.

#elegy of an empire#arthuriana#arthurian legend#arthurian mythology#arthurian literature#welsh mythology#ask#ask game#writing#salomania

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

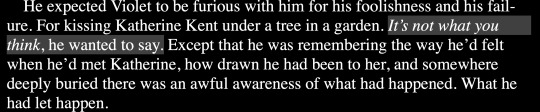

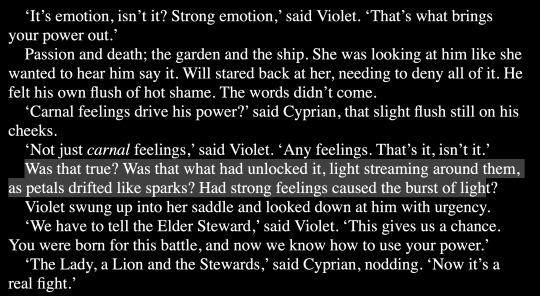

Will and his feelings for Katherine

In this TED talk, I will argue that Will guessed or at least suspected that Katherine was his sister from the moment he met her, and hence there were no romantic feelings from his side.

[Lots of spoilers]

Yes, maybe it's obvious for everyone, but I still find it interesting to inspect how the narrative structure was keeping us intentionally in the dark both because of different POVs and because of the parts of the backstory that we get only way afterward.

The idea that there were any romantic feelings comes from two sources, Katherine's POV and Violet's. But when we look at the story from Will's perspective the meaning of his actions changes.

Let's start from the beginning.

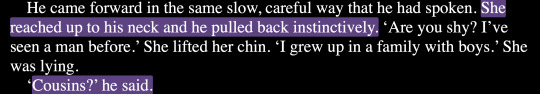

Assumption 1: Some vague suspicions that he had siblings (backstory in Book 2, Elizabeth's POV)

Will was around 6-7 years old when Elizabeth was born. At that age, he would at least remember something, even if his mother never talked about the baby, even if she said that the child died or claimed that it never happened. Some memories, some half-forgotten moments must have stayed with him.

He knew for sure that his mother had a platitude of secrets, that she was afraid of something, and that she acted cautiously.

Assumption 2: Almost sure that he has/had sisters after his mother's death (Book 1, very close to the end, Will's POV )

Will is around 16, his mother is dying, covered in blood, murdered by unknown people. And she is talking nonsense. She is afraid of Will, so she attacks him, and she begs him not to hurt her girls.

Will was never stupid. And he had plenty of time to think about his mother's last words (and actions). And even though he wants to believe that she just didn't understand who he was, and what was going on, he is still our clever Will, and it's not that unbelievable, to at least suspect, that his mother really did have other children (girls), that she had to give up (and maybe that, somehow connected to her death).

He doesn't know if the girls are alive or where they are, but at that point, he must be almost sure that his mother had daughters.

Fact 1: Will knows both how his mother looks (obviously) and how Lady looks (Will's POV, Chapter 1)

Will is probably the only person alive, other than Devon and Sandy, who knows how Lady looks, and seeing her in the mirror he immediately recognizes that she has similarities to his late mother.

Conclusion 1: When he saw Katherine for the first time he, for sure, noticed that she looked very similar to his mother and to Lady.

Once again, Will is smart, and seeing Katherin for the first time, he understands that she must be his sister.

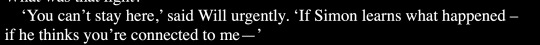

He tries to find out if she has any other family members, asking her about her cousins.

When she reaches to his neck, he instinctively pulls away. The same way he wanted to pull away from Lady in the mirror. Because in both instances he thinks about his mother.

And at the end of their first meeting, he says that he was wrong, and he won't do whatever he planned.

Fact 2: When Katherine kisses him, Will pulls back

Will never initiate or encourage any intimacy. Probably because he didn't feel that way about her, but also because she is his sister.

She kissed him.

He tried to warn her and protect her because he promised his mom.

And Violet is the one who talks about love and kisses, while Will wants to say “It’s not what you think” because it's not. And it's not what we, readers, think because at that point Will (who's still not stupid) very much suspects that he is either Dark King's descendant or Dark King Reborn.

So my conclusion is that the feelings he has for Katherine are mixed but there is very little indication that he felt anything romantic or passionate toward her.

The whole point of this long post is an attempt to prove that Pacat is playing with our minds via POVs, vague dialogs, and a backstory that is revealed way too late. And if we can't trust the story in these small details, we also can't trust it in much bigger points such as Dark vs Light Sides, the role of the Collar, and the story of The Betrayer.

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

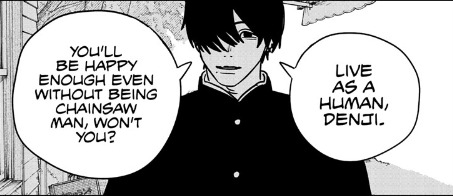

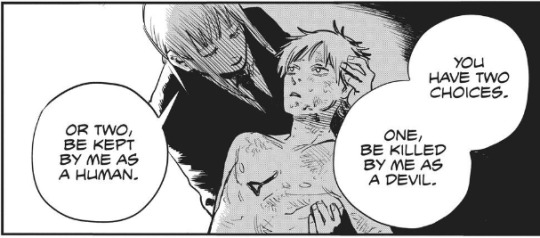

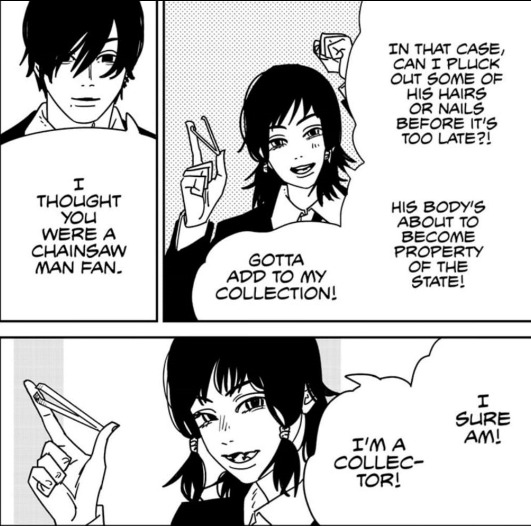

chainsaw man chapter 156:

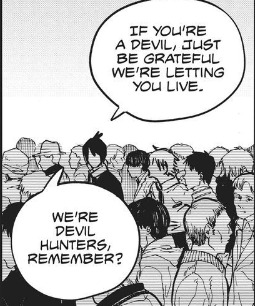

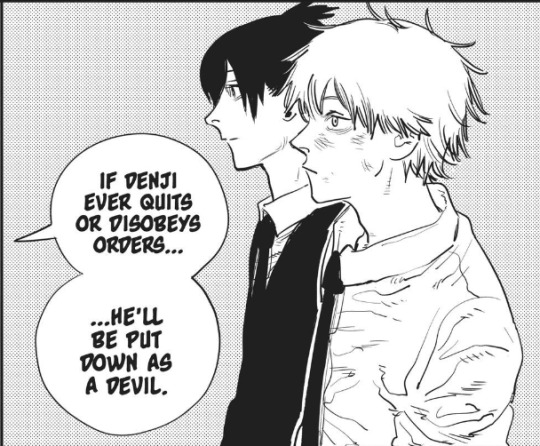

thinking about yoshida as a framer. he’s the one who presents this frame to denji - one between normal and abnormal, the two choices he offers. a lot of the way this attempts to lend direction to denji’s journey borrows from how part one forms its narrative with its human/devil dichotomy.

there’s a lot of nuance as to how this dichotomy is presented, and denji itself isn’t strictly a vessel for these values (this categorisation to them is rather conversed with through his mirror aki). denji’s existence as a hybrid searching for warmth and intimacy and his own dream confounds these values, this set structure.

because while the human/devil rift is resolved as false, it’s also clearly human built. devils are ideas that are built out of human fears and imaginings. we see devils being used as tools by the public safety while simultaneously being the ones they fight against.

this carries over into part two with fandom. i’ve talked about fumiko in specific to fandom multiple times already so i have little to say here but

fandom in part two, with the use of ideas, with its iconisation is ultimately a concentrated and transparent version of the nature of part one’s devilhood. possession of this icon and its dispossession (non participation in this idea of yourself that decontextualises you from Family - nayuta) is the dichotomy here because the human/devil of part one is turned onto denji almost forcibly.

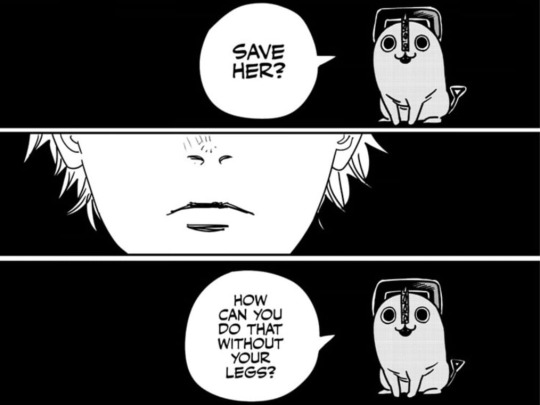

in p1 he receives aspects of this human/devil conundrum but his connection with pochita crystallised into hybridism builds onto this and in the end resolves it with the response to nayuta. the love.

and from his conversation with yoshida, we’re given denji defying the p2 dichotomy also because of pochita, the dog dream, the nayuta to it all (this connection, the family which i’ve already mentioned in quite a few of my earlier threads)

and yoshida here is instead the vessel for these values, turned upon denji. personally a lot of his mannerisms come across as him himself understanding his role in this categorisation but the thoughts i have on him are still mere speculation. argh

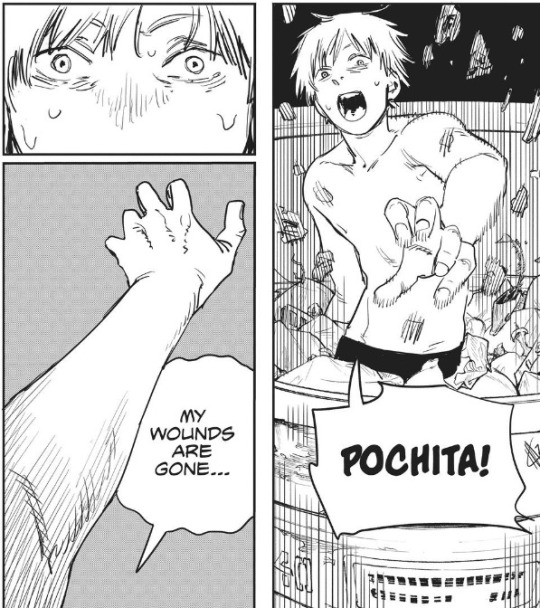

i do find it very interesting here then how the dissection differs. denji in part one is killed as a human by the zombie devil and pochita stitches him back together as he is torn apart by the yakuza’s brutal violence.

it’s quite the opposite here. pochita is the one who informs him about his body’s condition, its inability because in part this dissection is because of pochita. it’s nothing like the brutality of the yakuza, it’s cold and clinical. denji is regarded as a devil, entirely.

his body parts which were cast away into the dumpster in part one are instead kept as precious treasures by his fan.

fujimoto’s commentary on idealisation threads its way through his writing on devilhood, on religion and so much of this

is centred around the body. his writing of bodyhood when it comes to the weapon hybrids is something i’ve already written a little about, how its coming apart, its immortality is significant of its decontextualisation as conjectured with the context and the history offered by family and connection. and eating also becomes a carrier of the idea of the body (with the cannibalism in part one and even in fire punch).

denji’s story is devastating because of how it blurs between different structures and thus challenges them, is swallowed by them, is victimised by them. and this blurring is partly because of the very real underlying theme of love below all this. the love that makes pochita give life to denji, the same craving for intimacy that makes makima seek the chainsaw man and want to live together, eat together, sleep together with him,

the same love, conflicted and borne out of life under exploitation that denies and makes use of this love, which makes nayuta sacrifice herself for denji and denji struggle out of bed, having broken the rules for both the chainsaw man makima designed for him, and for nayuta.

69 notes

·

View notes

Note

Scarian costume party?!?

I LOVE THIS WIP it brings me joy and whimsy thank you for asking me about it (i definitely didn't coerce people at all by teasing it in another post lol)

scarian costume party

They’re at this stupid costume party and Grian hates costume parties, and he was never good with dressing up, so he’s just slouched in a corner in one of his ten identical red jumpers, begging not to be asked what his costume is, whilst Scar walks in in a picture-perfect recreation of Han Solo’s costume from The Empire Strikes Back. And not only that, he looks good. Grian is furious.

the first fandom i was ever truly a part of was for the volleyball anime haikyuu where there's twelve billion characters and most fics had every single one of them interact with all the popular ships in the background all the time and i wanted to write essentially my version of that for hermitcraft/life series. so behold: The Costume Party

BigB’s sat, legs dangling, on the island counter, covered in pale vines and painted grey, in a pretty accurate Creaking costume. He gives Grian a slightly pleading look as Scar enthuses to him about the slight differences in Han’s costume during the original trilogy, and that ‘Despite this, in the third film, when Han’s frozen in carbonite, the model from the film seems to use the A New Hope shirt as a model rather than the shirt he’s seen in in the third film- well, the sixth film, technically, but you get the point…’

this wip is hyperfixation heaven for me just imagining how all the different people would INTERACT and what what they would WEAR and what would go WRONG and who would they ARRIVE with and who would they LEAVE with... it's the stuff dreams are made of

Mumbo approaches him with That Look plastered all over his stupid face. “Jealous of the costume?” Grian scoffs. “Jealous? more like livid.” Mumbo sighs. “Relatable.” The man had a similar struggle with his own wardrobe, and, in a fit of anxiety, shaved off his whole moustache. The look itself is so unsettling that he hasn’t even needed to wear a different suit.

okay so here is where the plot divergence comes in- there are basically two different versions of this fic with different pairings as the main pairing. the most written version has scarian (that's the one above) but at that point in The Spiral i was still mostly just watching scar grian and mumbo and didn't really know who most of the other people were, which is why i abandoned the fic in the first place, vowing to RETURN once i had a stronger grasp on the characters:

this is honestly so much like you have to watch a day’s worth of content to understand ONE PERSON there are like 16 plus popular people here and only lil ole me!!!!!

little did i know that by that point i would know about gemtho (ship of the whole universe). and thus the other version of this fic was born:

etho sees gem at a party and the whole world stops spinning. in EVERY universe this man must be bowled over by her

which is what i mentioned in my redstone testing post. if i was to finish this fic i honestly think i could do a multiple POV situation with several different ships/ stories that INTERTWINE kind of like the plot in madagascar 2!! (lame reference i know but if you've watched that film you know it has the best narrative structure ever i bring it up all the damn time...)

someone tap me on my shoulder every day so i write this... this is the WORST PART of this series every time i talk about a wip i wanna finish it again!!!

#wip ask series#scarian#gemtho#THIS COULD BE SOOO GOOD OMFG WHY DO I DO THIS TO MYSELF#hermitshipping

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

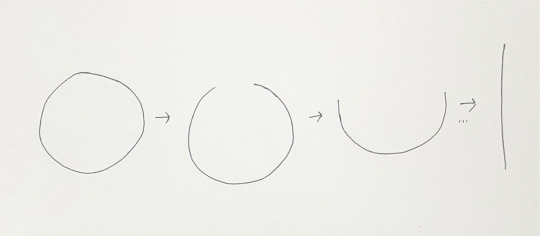

circle, line

A circle and a line look different, right?

What about now?

Time in gintama is a useless subject. Unfortunately, it is also a prerequisite to the gintama-human ontology. Thus, with a heavy heart, I look at lines, loops, and other unlikely time-mechanics in order to construct a gintama time for the gintama-human.

Throughout this pseudoscientific inquiry, I locate gintama time– which I eventually call [time], for lack of better notation– in my thematic abuse of two mathematical concepts: irrationality and uncountable infinity. To give away the end, [time] is an uncountable infinity born in irrationality. Which, even to its own creator, makes little sense.

Finally, this is my defense of the gintama time loop. Why? Well, I like loops and loop-like things, and, after all, we want good things to last, to repeat. So this turns out to be a love letter to algebraic topology. Sorry time loop fiction.

Onto more interesting things.

preliminary time notes

To think about time in gintama, I bracket [real world time] from [the narrative structure of gintama, which follows a time] and [time as characters in gintama experience it, i.e. personal time]. The latter two time-categories reflect [real world time] because gintama is written by an author, who, by virtue of existing, lives in [real world time]. That is, while narrative is fun because you can play with reality to make something new (e.g., time loop, time travel, non-chronological narratives in general), creation still requires building blocks, which are ultimately some sort of known assumption, that inevitably require some understanding of actual Time.

All this to say I look at [narrative time] and [personal time] through philosophies about [real world time], which themselves are not especially real; in other words, my methodology is kind of shit.

the situation– personal time

Otae announces the whole of gintama in chapter one.

This is gintama’s genetic code.

To speak of time here is to note a few things:

1. amanto possess advanced technology;

2. humans are forced to throw away their physical swords;

3. the sword of the soul.

The sword is a tool*; later chapters tell us that it “carries the soul”. So the sword represents, or, rather, is, something irreplaceable to humanity, that relates to the soul and personhood. This much is corroborated by the plot cycle.

With contrast to the sword, time appears impersonal. We conceive of time, at least scientifically, as the movement between past to present, present to future, stretching infinitely before and after, where our existence does not matter to its flow.

But would “time” exist without anyone to observe it?

Alternatively, how can “time” be experienced as time– as a movement– without anything to measure it?

The human must “create” “time”, if only because it would not be “time” without a person to observe and call it as such. What this person perceives, they conceptualize as movement (measurement); and thus there must be a prior position to reference, or, in the least, a default– a memory.

So “time” requires the present to be given by a prior; that is, for “time” to be experienced, the human who observes it needs already given into a past. The past itself (“knowledge” of the histories that make us who we are, “knowledge” of the tools that allow us to intend various things)– i.e., its inherent “given-ness” to us– depends upon it outliving those who live it. Thus various contexts, with their technologies, arts, and writing (though these are not really separable), function also to contain the essential past-as-memory for those who use and engage with them.

Alright, great, but what does this have to do with the dick-and-balls manga? Nothing, really, except for everything. The amanto (with futuristic technology, in futuristic contexts**) force humans to give up their swords. It would be ridiculous to talk about what the “sword” means here. Suffice to say that it carries (an assumed) cultural-historical weight, an (idealized) memory. We would expect that its dispossession disrupts temporality. And it does– hence the “time loop”.

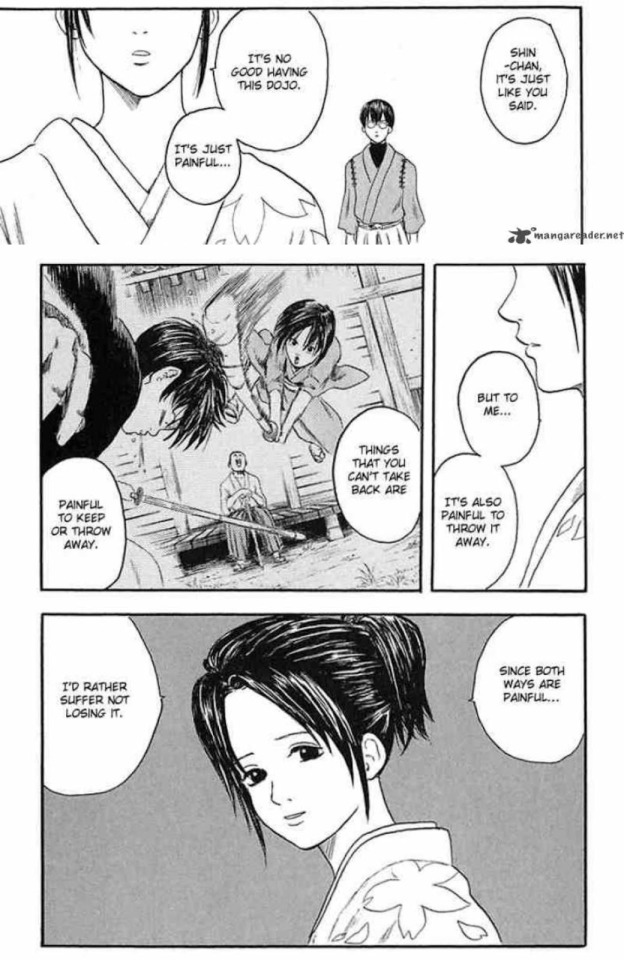

People love to talk about cyclical time in gintama. It is the same situations, over and over again; that no one ages, injuries heal by the next chapter, and, more than serial-typical regressions, that there is a sense that things won’t work, that important change won’t last, that life “just gets worse and worse”. Time as lasting change– or what we like to call “linear time”– doesn’t feel like it exists.

To return to chapter one. Here the central conflict is not actually between amanto and human; it is between Shinpachi and Otae. Their dying father tells them that even if they give up their physical swords (memory, past), they are not to lose the sword in their soul (?unknown). Sword-less Shinpachi resents him. Rather than “cling to the past”, he tries to adapt to the “linear time” of the amanto: he works in modern food service, gives up on the dojo, and, most importantly, opposes Otae.

What does Otae do? We might expect her to inverse Shinpachi, that is, to “embrace” cyclicality, which would be to give up. She doesn’t. Otae tries to adjust, to make a living and survive, but, unlike her brother, she does so also to protect the “thing she can never take back”. This, as Shinpachi points out, is ridiculous, unrealistic, and makes no sense. And yet it is Otae who is thematically vindicated in the end.

From the first chapter, then, we can construct a sense of [personal time (to the characters)]. Again, for change to exist, there must be a prior form; that is, a certain sort of time is what makes change (technological, political, situational advancement) possible. Further, the self is involved in the process of time. Thus when the self is not whole (lacks the sword), time, and thereby change, becomes cyclical. So “time”, to the amanto, advances, because they can work with their external “selves” (technology, worlds, knowledge-memory) to “make change”. But time, to humanity, loops back on itself, is stopped, because humanity is bereft of its self and can only return to the starting point.

We notice that humans still live in a world where time progresses– where time goes on without them. There is a split between the time of the self and the time of the world. Shinpachi decides to do away with memory and join the world-time, the “linear time”, that is, the time of futuristic technology and change; but his sister, who goes along with this and drags the past with her, does much better.

For a more thorough application of this thought, please rewatch the monkey hunter arc.

*It is also (obviously) a dick. **This reveals some connection between the concepts of “tool”, “context”, and time. Though I say so inverse-facetiously, since nothing about gintama can be taken as if it were serious.

time loop– narrative time

So what about infinity?

Personal time is not infinity. In a first sense, it simply is not infinite– characters die. In a second sense, even considering that memory can be (haphazardly) preserved beyond a lifetime, especially in a story, humanity as a whole is finite– there comes a point, eventually, where no one is left to do the remembering. And in a third sense, personal time is still a string of pasts that were once presents, into futures that will be presents; though this finite string might divide into an infinite number of presents, its divisibility renders it still essentially patterned, which is to say that it is not really “infinity”– it is still mathematically countable.

I mentioned a dysfunction of personal time into cyclical (“un-change-able”) personal time. This is associated with sword-less-ness, equivalently memory-loss, equivalently not being a whole self. The fun of stories is that “character” can be projected into the structure of the story itself; it would make sense for cyclical personal time to have some correspondence to, or at least effect on, narrative time, that is, narrative structure.

At this point I should be more general about the time loop.

The time loop is thought to stand opposed to “linear time” in the stagnation-change, lack-presence, circle(hole)-line([censored]) dichotomy. Specifically, the time loop is opposed to “linear time” in the sense that nothing (usually) changes in a time loop. Or, more exactly, change is slow, nothing gets “better” in any real sense. Again, only where time flows “linearly" can we build off of what is prior, can we intend and achieve a future, can we change for the better (or so we assume). Thus the time loop carries a sort of moral condemnation in its very structure— a karmic debt, if you will.

Characters in plots get thrown into time loops because something has gone wrong. Whether or not they are the direct cause, the character must “figure something out”, “learn a lesson”, that is, address the problem that created the time loop, which will almost always be related to a step within the story of their self-development, in order to escape it. The point of the story is to escape it. This is just how stories go.

Then the gintama narrative “time loop” is barely a time loop. It repeats itself, sure, and no one ages, but that’s because no one should age in a wsj serial and sorachi tried to be funny about it. Still, some lingering sense of futility, or maybe just the sheer repetition of the same event for 16 years of serialization, weighs on anyone who reads it. This kind of feels like time loop fiction; there should be a point to the plot cycles. What are they trying to force Gintoki to do, to show us in his character? What are they aiming for, what is driving the “time loop” in the first place?

Takasugi is driving the time loop.

(More specifically, Takasugi’s crushed eye-ball (soul), his eyelid; inaccessible past (memory), is driving the time loop.)