#this chapter has Berthier in it too

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

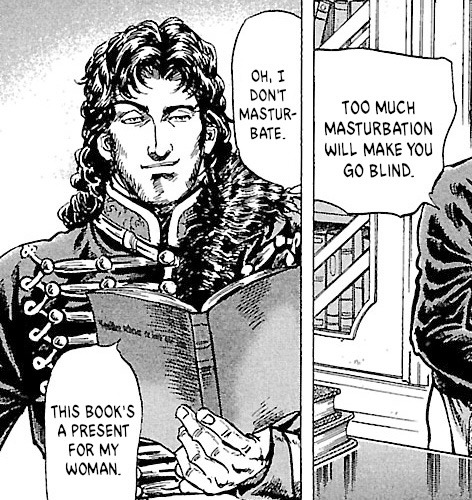

RP Murat reacts to Hasegawa Murat:

....

Is that supposed to be me?

Oh my god, look at me!

My compliments to my artist! He's made me so handsome and perfect here! "A captive of your love"? Yes, that's me, really, what's so terrible about saying that?

I can look at myself all day! Tetsuya Hasegawa has captured my essence, the essence that is Murat! 😘

I respectfully disagree. The key to a healthy and balanced life is taking some time out for yourself, if you get my meaning. Like with anything else, it's better with friends!

I breathlessly await your next installment, Monsieur Hasegawa. You've given me quite the introduction into this tale of your illustrated epic!

#tetsuya hasegawa#napoleon age of the lion#manga#RP Murat reacts#this chapter has Berthier in it too#oh my god Berthier#napoleon age of the lion vol 6 ch 037#napoleonic RP scene

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Laure and her memoirs for 1812/3 (part 5/?) - A digression: Junot at Smolensk

Laure does take her sweet time until she talks in detail about the great injustice that, according to her memoirs, had been done to Junot and was the main reason for the extreme changes in his character during the last months of his life. She only really adresses it in Volume 15, chapter VIII, though it does play a role earlier. But in this chapter, she has Junot tell the story from his point of view, and the story is, of course, the one of the combats around Smolensk and Valoutina (17 and 19 August 1812).

But I would like to start a bit earlier, at the beginning of he campaign, mostly because… well, Laure felt she also needed to drag Eugène into this 😁.

We’ve already seen Laure claiming in Volume 14 that Napoleon had given Junot a particularly brilliant command when he sent him to Milan. Turns out, Junot’s job in truth merely consisted in leading the Italian troops, destined to take part in the Russian campaign as 4th corps, into Prussia and Poland and command them until Eugène arrived (Eugène, similar to Napoleon, as administrator of a country would only leave for the campaign at the latest date possible). While Napoleon may have toyed with the idea of leaving Eugène in Paris as some sort of representative of the crown, he ultimately decided against it, and Eugène took command of his troops himself.

Leaving Junot without a job. Napoleon and Berthier tried to cover it up by claiming that, as Eugène technically was at the head of two army corps, Junot would still be in command of 4th corps somehow, but factually he was a second-in-command without anything to do.

Presumably, Junot had imagined that he would play in 4th corps a role similar to Vandamme in Jérome’s 8th corps: King Jérome officially at the head of the army corps, with Vandamme factually in charge. This kind of job sharing already fell apart in the case of Jérome and Vandamme, and as far as Eugène was concerned, it never was an option. So when Junot demanded to have his own staff at 4th corps, in addition to Eugène’s staff, either Napoleon or Eugène or most likely both put their foot down. Doubling the existing and experienced état-major of the Army of Italy was unnecessary at best, dangerous at worst. It was also pretty clear that Eugène did not need a second-in-command who would take care of 4th corps, as long as 4th corps had nothing to do but march.

In her memoirs, Laure – as she does so marvellously – while belittling Eugène as much as she can, takes great care to imply that the decision to give superior command to him had been a political one, i.e., one motivated by the fact that Eugène happened to be Napoleon’s stepson and an Imperial prince, something that an old war horse like Junot simply could not accept.

It was simple enough to think, and the emperor must have done so, that, whatever Junot's friendship for Prince Eugène, he could not forget that ten years before he had known him as a child and as a colonel in his stepfather's guard; that the antecedents of this were not the familiarity of children, but a kind of almost protective friendship, such as one could have for a young man of high hopes like Eugène, a man already famous among the brave. Of all this, there were too few days... there were especially too few for his head, old with scars, to bow with resignation before the young moustache of viceroyalty: all the trappings of sovereignty and power had never had their effect in the emperor's family except on his own person.

Not that Junot was in any way

… reluctant to serve under Eugène, a loyal and brave child whom [Junot] had put on horseback...

of course.

Let’s leave aside the question when the F Junot had ever shown "protective friendship" or tutorship for Eugène (I at least could not come up with any example). The assumption that the army would not follow anyone in the Imperial family other than Napoleon is not true, as events in 1813 would show, when the remaining officers, one Marshal Davout among them, rallied around Eugène not only willingly but even with a sort of relief. But it is also completely irrelevant in this case, and Berthier tried to explain this to Junot in two different letters that Laure both quotes in full: The Army of Italy was simply Eugène’s army, the same army he had commanded during 1809 and led ever since. Why would he not be in command of this army if he was present? In summer 1812, Eugène was thirty years old (also balding and loosing his teeth) – hardly a child anymore. While he may not have been a particularly good or inspired general compared to the marshals (I lack the knowledge to evaluate this), he did have some experience with independent command and had an overall successful campaign against the Austrians under his belt. Beating Junot’s battle record – at least on paper, without regarding the circumstances – was not a particularly high bar either. In short, there was very little factual reason why Junot should not be put under Eugène’s command if he remained with 4th corps.

However, by doing so, he was almost reduced to the position of a mere divisionary general, and that had to sting and was decidedly an awkward position. I also find it interesting that Napoleon did not call him to his own entourage, like he did with Soult in 1813 (and maybe Lannes in Spain in 1808, too?). To me this makes it look as if Napoleon already had given up on Junot a long time before whatever happened at Smolensk. – As to Junot, he obviously felt that his situation hurt his pride. As late as in the two letters from 3 December, to Berthier and Napoleon, that Laure quotes in her memoirs, he keeps mentioning his high rank that does not agree with so lowly a command – making it sound as if the job simply was beneath Junot. (It also has to be said that a the same time, Ney, Eugène and probably many other superior officers were not above marching on foot among their soldiers, musket in hand and fighting like a private, commanding a mere handful of men that they still managed to rally under arms, without feeling this somehow hurt their pride.)

So we have Junot being a miserable supernumerary general already at the beginning of the campaign, and it was only after the infight between Vandamme, Jérome and Davout that Junot was relieved of his awkward situation and called up to take command of VIIIth corps, consisting of the troops of the Kingdom of Westphalia, with two divisionary generals under his command, French general Tharreau and Westphalian general von Ochs. The book by Paul Holzhausen "Die Deutschen in Russland 1812" ("The Germans in Russia 1812", Morawe & Scheffelt Verlag, Berlin 1912) lists several Westphalian sources in its introduction, and quotes some of them directly with regards to what happened at Smolensk. One huge caveat is true for all of them – they were, like Laure’s memoirs and unlike the letters intercepted by the Russians, written after the events, sometimes a long time later. So they suffer from precisely the same problems as Laure’s memoirs, and it is quite possible for them to be influenced by earlier reports like Ségur’s book on the Russian campaign, that had put all the blame on Junot.

That being said, these sources also often are very detailed, show events from different perspectives, and while they (and their authors) disagree in details, they do agree in the main aspects.

So, what did happen at Smolensk? In short, the Russians first, on 16/17 August, tried to defend the city before abandoning it and retreating on 18 and 19 August. On the 17th, the French attacked with only three army corps, as 4th corps had been sent on another route in order to cover the main army’s flank, and Junot’s VIIIth corps arrived too late to take part in the action.

Which occasioned the first of two army bulletins (13th bulletin, 21 August 1812) mentioning Junot in a not particularly flattering way:

[…] The Duke of Abrantes, with the 8th corps, had lost his way and made a false move. [...]

Two days later, as the Russians continued their retreat, Junot’s 8th corps at Walutina Gora (sometimes also: Valoutina or Valontina) came into a position that, during a certain time, might have allowed them to cut off a part of the Russian army. The occasion passed, however, without 8th corps acting. At least that is what the 14th bulletin (23 August 1812) claimed:

The Duke of Abrantès had crossed the Borysthene two leagues to the right of Smolensk; he found himself on the enemy's rear; he could, by marching decisively, intercept the main road to Moscow and make the retreat of this rearguard difficult. However, the other echelons of the enemy army that were within range, informed of the success and speed of this first attack, retraced their steps [...]

To put things in perspective: These are two brief remarks in two extremely detailled army bulletins literally tens of pages long. But they stung Junot enough for him to try and defend himself in a letter he wrote to Napoleon much later, on 3 December, shortly before Napoleon left the army in order to return to Paris. The letter is quoted by Laure (only in parts, as a footnote states) in Volume 15, chapter VIII of her memoirs:

To the Emperor Moladetchno, 3 December 1812 Sire! This memorable campaign is coming to an end. I began it with a command intended to bring glory, and I am ending it with a command too low for my rank and in which I can only continue to dishonour myself... Two bulletins have hit me hard, Sire, and I have not complained. But if public opinion is not what I value most, Your Majesty's opinion is what I value more than my life. The bulletin talking about the army's march on Smolensk says that I got lost and that I made a false move... Well, Sire, I did not lose my way, but on the second day of the march I travelled six leagues instead of the eight that I wanted to travel (something that was easy to repair on the other days). General Tharreau got lost through disobedience, and despite the fact that I had left him some cavalry plantons to direct him towards Boullianow... At ten o'clock in the evening, when I sent for my generals to tell them about our march, General Tharreau was not to be found in the position I had designated for him. I thought he had stayed behind and I sent to find him... The officer in charge of this mission returned to camp at three o'clock in the morning without having met him; then, remembering his opinion of the previous day on our direction, and knowing his character, I had no doubt that he would have wanted to follow the right in order to reach the road to Mitislaw that we had to join. I immediately sent Colonel Revest, my chief of staff, who indeed found him more than four leagues away from us, and he did not return to camp until after four o'clock in the evening... I had learned that Your Majesty had reason to be dissatisfied with this officer-general; I hoped, by dint of marching, to right his wrongs, and in order not to destroy this man, I bore the punishment for his fault. The whole 8th Corps witnessed this... but all I care about is that Your Majesty knows the truth: this act of justice cost me dearly. The report on the affair of 19 August, in front of Smolensk, accuses me of not having acted firmly enough... so I was FEARFUL?... Well, Sire, Your Majesty will know my conduct; it was witnessed on that day by General Valence, General Sébastiani, General Bruyères and many others. I received the order to go and protect the construction of the bridges over the Boristhène; I did so, and we crossed this river rather slowly, because of our artillery, the ramps of the bridges being very bad... The roads that we had been obliged to make also delayed us a great deal, and I was only able to emerge from the wood at two o'clock, and I took up my position... I HAD RECEIVED NO ORDER TO FIGHT, I did not even know, Sire, what troops were fighting on my left; but after half an hour, and when the Gudin division arrived, the fire having started up again much more strongly, I mounted my horse and crossed a large ravine which I had in front of me with two battalions of light infantry and my cavalry, I arrived in a superb position in the rear of the enemy; the plain or rather the plateau which separated us from the position of the Russian rearguard was covered with skirmishers and cavalry. Nevertheless, convinced that we could be useful in the frontal attack, I sent my small vanguard through, which recognised that the artillery had to rebuild a bridge in a village on the right in order to be able to pass, which was carried out, while I sent the order to the 8th corps to come and join me in its entirety and as quickly as possible.

So, we have two points of defence here: 1) Junot according to himself only arrived too late to take part in the battle of Smolensk because he covered up the disobedience of one of his divisionary generals (who, conveniently, at the time Junot sent his letter could not comment on this anymore as he had died of wounds received at the battle of Borodino). 2) Junot did not take part in the action at Valontina because he never received any order to do so and because he needed more time to understand the situation and to deploy his troops.

(The second argument does sound a bit weak, considering how both Bernadotte and Grouchy to this very day are accused by armchair generals for not having "marched to the sound of the guns". But whatever, I don't know enough about military matters to truly comment.)

Junot in his letter cited 8th corps as witnesses. So, what do the witnesses have to say to all this?

As to the first incident, 8th corps arriving too late for the battle of Smolensk, Holzhausen summarises the different Westphalian sources briefly as follows:

Hauptmann v. Linsingen relates that during the concentration of the army preceding that battle, the Westphalian corps was led astray for a whole day on 15 August by a Jew who knew the area and whom the duke had taken with him as a guide. But others also speak of a country house where Junot had had too good a breakfast.

(Biting my tongue here in order not to speculate about how long it takes to eat 300 oysters...)

I’ve checked von Linsingen’s "diary" (it’s not really one, but a day-by-day report that may be based on one) for more details: Jérome left the army on 16 July, Junot received command of 8th corps on 30 July/1 August. In the interim, Tharreau, as the senior-most divisionary general, was in command. About the reason why 8th corps was late to the battle of Smolensk, Linsingen has this to say:

On 15 August, the birthday of Emperor Napoleon, we crossed the border of old Russia. It was generally rumoured that there would be a battle today. We had already left the bivouac at 2 o'clock in the morning. With brief interruptions, we marched until 9 o'clock in the evening, when we realised that we were barely four hours away from our marching point. The local guide who had been attached to the avant-garde was a Jew. Had he deliberately led us astray, had he been mistaken himself? Who can tell? In any case, the army corps had had an extremely strenuous march and had not reached the point it was supposed to reach. The duke had the Jew shot immediately.

That’s a pretty straightforward report, and it does not need any oysters or disobedient French generals in order to explain 8th corps’ delay. A bit later, Linsingen comments:

At about 8 o'clock in the evening [on 16 August] we set up a bivouac beyond the little town of Wolkowo. As soon as we had lit a fire and put our meagre food in the pots, we had to set off and march on for another hour so that the duke could be quite safe in his quarters, a castle. In general, the Duke of Abrantes, unlike our other senior officers, was very noticeably concerned about his person and, unlike our other superiors, showed no care for his soldiers.

Another source is the very long and convoluted report by Friedrich Wilhelm von Lossberg that has been given the form of letters "Briefe in die Heimath geschrieben während des Feldzugs in Rußland", published in Kassel in 1844. He describes the first impression the troops had of their new commander as follows:

Near Orsza, 2nd August. All of us officers of the 2nd Infantry Brigade paid our respects to the Duke of Abrantes. Judging by his appearance, he is a man of some 40 years of age, blond and of stocky build. Judging by his features, one would not think he was French. The man spoke quite well, but (especially as a soldier) his appearance did not inspire confidence, which was not helped by the reputation that preceded him. In his lower military ranks he is said to have shown much courage and to have had the good fortune to be noticed by Napoleon. As I compared him in my mind with Vandamme, this comparison could not be favourable to him [...].

In a footnote he clarifies:

His unfortunate campaign in Portugal, as well as the defeat he suffered against the Austrian General Kiemaier in the 1809 campaign at Hof, was no secret to anyone.

So, very little trust in this new commander already from the very beginning.

About the delay of 8th corps before the battle of Smolensk Lossfeld writes:

Close to Triana, 15 August. We have been on the road for 16 hours, but have only gained 4 hours of ground, as the army corps marched too far to the right for several hours and finally, when they noticed this, turned left onto a crossroad. We are currently at 12 o'clock at night, marching in brigades, jammed between defiles. In addition, the bridge collapsed due to an ammunition wagon from the regiment following us, […] [...] Close to Smolensk, 17. August. Left the last bivouac at 2 AM, marched until 9 AM and stopped six hours from Smolensk in a small village that burned down due to soldiers’ carelessness [...]. We probably would have remained here all day, if not around 2 PM an officer from headquarters had hurried up to us in order to fetch our army corps, that in vain had been expected at Smolensk since yesterday; he accomplished his task towards Junot, who happened to be at one of the campfires at that moment, in such a loud voice, that the news immediately spread throughout the whole army corps. We at once set off to march and I may assure that among all superior officers irritation was voiced both about this unnecessary halt and especially about the detour that we had made on the 15th that had us cost 24 hours of time. In order to excuse Junot, it is claimed that the similarity of Russian and Polish names and the difficulty to pronounce them correctly, in addition to a lack of good maps of Russia may have caused a mistake […], which is quite probable and which I would be inclined to believe, if the great indolence and idleness of our corps commander did not, at least in outward appearance, make itself felt in all things. Truly! The man is not made to inspire the least bit of confidence, which Vandamme, seen as a soldier, had in such a large degree.

Lossfeld a fan of Vandamme. Check. In any case, he also corroborates the story that 8th corps really had gone astray due to an error. No mention of any insubordinate French generals being missed.

Finally, as a third example of the early difficulties, here’s an excerpt from the biography of general von Ochs, one of the two divisionary generals under Junot’s command, written by his relative Leopold von Hohenhausen based on Ochs’s papers and published in 1827.

On 4th August the Duke of Abrantes reviewed the corps; he found it to be above his expectations both in bearing and in manoeuvrability, and promised to become its protector, also, as he phrased it, to teach the Westphalians how to live well in the field. Several Westphalian officers who had previously served under Junot in French service did not pass a favourable judgement on his character and military abilities; they confirmed this by citing the facts, which is why they had no confidence in the new general in chief even before the start of hostilities. As, however, he was one of the Emperor's first favourites, which was supposed to stem from the excellent service he had rendered the latter as sergeant at the siege of Toulon, for which Napoleon promised him lifelong gratitude, the Westphalians hoped that the Emperor would give his favourite the opportunity to perform glorious deeds and would not treat the corps entrusted to him with neglect. The future has shown, however, that the Westphalian corps could not have met with a greater misfortune than having the Duke of Abrantes as commanding general in this campaign.

[…] 8th Corps was ordered to leave Orsza on 12 August in order to advance on the right of the army road leading to Smolensk, at the same height as the 1st Army Corps, which was marching on that road. [...] On the 12th the corps arrived on the right of Dombrowna, on the 13th at Romanowa, on the 14th at Buewo, without seeing the enemy. As it had to pass many defiles on the bad side roads, including several boggy places and creeks [...], it was necessary to stop several times and the troops were almost never able to reach the bivouacs before nightfall. [...] Up to this point, however, the Duke had carried out his march according to orders. On the 15th, however, he was to remain on the right wing of the army until he reached Tezerkowikky, three hours to the right of the post station Korydnia on the main road, which is today the Emperor's headquarters. He therefore set off at 2 o'clock in the morning without, however, informing his generals of the destination of the march, the name of which he probably did not understand correctly or had mispronounced to the man leading him. One hour from Buewo, the Old Russian border was passed, and the column then travelled through the small town of Ziurowizy, which was deserted by its inhabitants. There were no more Jews in Old Russia, who due to their knowledge of the German language and their willingness to serve had made themselves very useful to the army, and from now on the inhabitants were fleeing far away; it was therefore not so easy to get back on the right track if one lost one's way. The corps marched without stopping for several miles in a direction that deviated almost perpendicularly to the right from the Smolensk road. The duke, who himself led the avant-garde, must have been convinced that he had lost his way in the afternoon, as he was out of contact with the other corps and the reconnaissance sent out for hours could not discover any troops. He therefore turned back and marched back in almost the same direction, but along roads that were barely passable, in order to gain Bojanowa not far from Krasnoy, where he hoped to obtain precise information from the army and find a convenient road for the column. The troops therefore marched until 12 o'clock at night and had barely gained two miles of terrain from Buewo. [...] Napoleon attacked the city of Smolensk on the 17th; [...] Napoleon sent an officer to seek out the Duke of Abrantes and to order him to hasten his march as much as possible and to advance on the extreme right wing as far as the Dnieper, so that Smolensk would be completely surrounded on the left bank. Although the duke had marched off after daybreak on the 17th, he lingered for several hours at a beautiful castle to have a lunch and had his corps halt during this time, despite the fact that the cannon fire from Smolensk could be clearly heard and even at a great distance the smoke rising from the conflagration could be recognised. Here the imperial order reached the duke and now we set off as quickly as possible for Smolensk, three miles away. The light infantry had to cover most of the distance at a run, the cavalry almost always at a trot. Towards evening the avant-garde arrived, and in the dark of night the infantry arrived in front of Smolensk. However, as the encounter had already been decided, the 8th Corps was immediately assigned a bivouac not far from that of the Imperial Guards.

That is pretty close to Lossfeld’s report, except the author also speculates about a motive for the unnecessary halt on 17 August.

So maybe there were some oysters involved after all?

I guess that’s enough examples to show that, as far as the first incident is concerned, the Westphalian witnesses support what was claimed in the bulletin.

About the second incident, the lack of action at Walutina Gora, it’s pretty much the same, and I do not want to bore people too much with lengthy repetitions as this has gotten extremely long again. Just as a brief example, von Linsingen has this to say:

On 19 August, our army corps set off at 8 o'clock in the morning. It was to cross the Dnieper on two pontoon bridges about an hour below the town. [...] The Duke of Abrantes led the army corps about two hours further east and then took a concealed position behind a wooded hill and behind a village on the main Moscow road. We could clearly see the Russian army retreating along this road. Opposite us were Cossack pikets, of whom we could recognise man for man with the naked eye. Towards midday we heard heavy firing to our left, we saw the Russians perform a fighting retreat from the French - and we didn't move. Finally, at about 5 o'clock in the afternoon, the King of Naples arrived in a fury and brought the Duke of Abrantes the imperial order to attack immediately.

Which several units, mostly cavalry, then were sent to do. However, by that time, the Russians already received reinforcements, and the great opportunity was lost. Linsingen resumes:

It was made clear to all of us through just how difficult a defile we had allowed the Russians to withdraw unhindered along the Moscow road. We could easily have forced the retreat of the entire enemy army guard, if not also of Grand Duke Constantine's corps, if we had intervened decisively and in good time. The fact that we were too late for the affair at Smolensk may well be partly the Jew's fault, but the fact that we did not strike a crushing blow against the Russians on the 19th is not something for which anyone shares the blame with you, Monsieur le Duc.

Linsingen not a fan of Junot’s. Check.

But at least he (and as far as I’ve seen all other Westphalian sources, too) do confirm that Murat really at some point showed up in order to get Junot to act. Laure in her memoirs does try to throw some doubt onto the story for the sole reason that it’s Murat’s story.

I’ll wrap it up here before I break the character limit for a tumblr post – especially as the Westphalian reports with regards to the inaction at Valoutina/Walutina are all vicious towards Junot. If there is interest, I can translate more (there's more complaints from von Ochs about Junot's overall attitude during the march, and even more Vandamme-fanboyism from Lossfeld 😜) but I feel for now it suffices to say that no, the Westphalian eye witnesses unfortunately do not support Junot’s and Laure's version of the story in the least.

#napoleon's generals#and their wives#jean andoche junot#laure permon-junot#napoleon's family#eugene de beauharnais#kingdom of westphalia#russian campaign#napoleonic wars#smolensk 1812#napoleonic era

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now work gets serious on “Act 7 - Push”!

It’s been 24 hours since the release of Act 6 - A Face Like Thunder. You’d think I’d enjoy the accomplishment. Take a break. Relax.

Ha! As if!

I’ve got a fresh cup of coffee and my migraine meds. Time to get some writing done on the next chapter: Act 7 - Push!

It’s time for a wedding and the Sailor Guardians are invited! What is supposed to be a moment of happiness and fun after weeks of struggle turns into a disaster of epic proportions.

Naru is acting very strange. Minako debuts a song that might be a little too…personal. Usagi is at war with herself. Somebody accidentally drinks from the wrong punch bowl. Why is Ami’s “plus one” Berthier?

And just when the interpersonal drama threatens to completely derail the reception, the Black Moon Clan comes for a certain key around Chibiusa’s neck…and one of the Guardians will put it all on the line to save her!

Yeah…this is gonna be good…

#bishoujo senshi sailor moon#bssm#pgsm#pretty guardian sailor moon#sailor moon#sailor moon live action#sailor venus#sailor mars#sailor jupiter#sailor mercury#fanfic#tuxedo mask#chibiusa#black moon clan#ao3 fanfic#ao3#wattpad#fanfiction.net

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! Do you know why Berthier disliked Lasalle (if it's not about his brother's wife)? And where could I find more about this? Thank you 😘

The most commonly mentioned answer was Lasalle going after Berthier's brother's wife.

Which is honestly seems rather The Pot Calling the Kettle Black when Berthier also had a mistress?

Though I have no idea which book has the most Lasalle info.

Elting seems to have a somewhat negative assessment of Lasalle in Swords Around A Throne. Though he calls Lasalle without enemy but mentions Marbot disliked him but on a quick skim I didn't see what Marbot said about Lasalle in his memoirs. >_> I never finished reading Marbot's memoirs because I find him kind of annoying.

In Napoleon's Cavalry and its Leaders by David Johnson, there is a whole chapter for Lasalle but the Berthier's brother's wife incident is a very short paragraph.

Anyhow, now I am hunting through the stacks for who gives the most salacious version.

....god I wish more of my books had indexes. =_= I have too many books and my brain is soup.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean-Baptiste Berthier

In honor of Berthier's birthday, I thought it would be interesting to know a little more about where he came from. Luckily I have a biography by Franck Favier, who has a whole chapter dedicated to the origins and social rise of his family. His father comes across as quite a successful and hard-working man. We can see how such a man would influence our Berthier's work ethics and character.

Please be indulgent, I translated this a little too fast to be really good, but I did my best to be in time.

What a destiny for this family of the Ancien Régime: in three generations, it climbed the ranks of society, passing from the status of ploughman to the splendours of Versailles, then to that of Prince of the Empire! The ascent surprised, because the Berthier family escaped the inevitability of a predetermined fate.

The Berthiers come from the village of Chessy-les-Prés, on the borders of Champagne and Burgundy. The great-grandfather, Rodolphe (1648-1710), was a ploughman, then a laborer. He married a ploughman's daughter, Marie Branche, in 1671. From their marriage were born at least two children who reached adulthood, François (1676), and Michel (1679). The first seems to have known a relative social stagnation by remaining a ploughman, while the second progresses: between the two births, their father Rodolphe passed to domestic service, in the service of Michel de Changy, Lord of Vézannes, who will be the godfather of little Michel.

This parrainage appears providential, because it allows Michel to escape the peasant world to embrace the career of wheelwright, probably with the wheelwright of the seigneury. He then emigrated to the town of Tonnerre, a classic sign of local rural exodus. In 1712, he married Jeanne Dumez, daughter of the servant of the bailiff of Noyers. The Lord of Vézannes still appears as a co-signatory of the act. From their marriage six children are born: four daughters [...] and two sons of whom only Jean-Baptiste, born in 1721, reaches adulthood [...]

Jean-Baptiste enters the service of the seigneurial family. Destiny steps in: Jean-Baptiste inherited from his wheelwright father qualities in mathematics and geometry which surprised his master. The latter then plays his connections, which allows Jean-Baptiste to enter the Ministry of War in 1739 as an instructor, then in 1741 as inspector general at the Ecole de Mars, military academy of Paris [...] There he was responsible for making young nobles maneuver. His studies subsequently pushed him from geometry to topography. As inspector, he proposed to modify the training programs and obtained a little more practice: he built on Ile aux Cygnes, in Paris, a miniature fort called Fort-Dauphin for the exercise of a siege. In front of the marshals of France and the people of Paris, the cadets and officers mimed the assault and the defense of the work.

However, it was during the War of the Austrian Succession that Jean-Baptiste's career took a new turn. In 1744 he obtained a lieutenancy and a job in the body of geographic engineers.

This body of engineers, founded in 1691 by Vauban, was made up of soldiers specializing in topographical surveys. They quickly distinguished themselves from ordinary engineers, more occupied with fortification work, and brought together experts recognized for their skill and dexterity in drawing up maps that were very useful for military strategies. The function required physical (endurance), but also intellectual (geometry, trigonometry and drawing) and military (fortifications) qualities. It repulsed highborn people, but was a means of social advancement for individuals of more modest condition.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Fontenoy (1745), Jean-Baptiste Berthier joined the army, assigned to the staff of Marshal de Saxe, commanding the army of Flanders, as an engineer geographer serving for reconnaissance of the camps , marches and locations of the king's armies. He took part in the Dutch campaign, was noticed at the battle of Lawfeld on July 1 and 2, 1747, where he was also wounded. The war allowed him to show his skills and courage on the ground. On this occasion, he established an album of twenty-five maps relating the main facts of the campaign, an album which he offered to the king.

His reputation being made, he can consider another means of ascension: marriage. On September 23, 1749, he married Marie Françoise Lhuillier de La Serre, born in 1731, whose father, César Alexandre, was captain of the castle of the Marquis de Breteuil, in charge of the surveillance and hunting of the estate [..] All were from recent nobility [..]

Jean-Baptiste thus entered the networks of geographers, important networks which tended to perpetuate themselves, by endogamy, in castes, without progressing, unlike the Berthiers. Fortune was to further benefit the family, already well served: on September 13, 1751, a fireworks rocket celebrated for the birth of the Duke of Burgundy set the Great Stable of the Palace of Versailles ablaze. Faced with the improvisation of the emergency services, Jean-Baptiste Berthier takes the responsibility of organizing the fight against the disaster, even putting his body on the line. Louis XV, who witnessed his exploits in person, would be grateful to him. He will thus enter into the favor of the sovereign. He will be in charge of multiple tasks, participating for example in the founding of the Military School of Paris from 1751 or also, through his plans and drawings, in the improvement of French military ports.

1753 saw the birth of his first son, Louis-Alexandre, the eldest of an upcoming series of twelve children, six of whom survived the horrors of infant mortality. In 1757, Jean-Baptiste acceded to the post of chief geographer engineer and to the direction of maps and plans of the Ministry of War. As such, he is in direct contact with the King and the Minister of War, to whom he can present each morning, with supporting maps, the operations of the French army during the Seven Years' War. As for his wife, she is assigned the much sought-after office of Monsieur's chambermaid. This charge made it possible to penetrate even further into the King's House. Monsieur will also honor the Berthiers by holding on the baptismal font one of their sons named after himself, Louis-Stanislas, born in 1767, while one of their daughters, Jeanne-Antoinette, born in 1757, had for godmother the Marquise de Pompadour.

[..]

The Duke of Choiseul demanded from Berthier the construction of the hotels of the Navy and Foreign Affairs. The work was quickly completed, in eighteen months. Speed, reasonable cost, architectural elegance, richness of ornamentation, ingenuity of interior design are admired by contemporaries [..] Moreover, always pragmatic, Berthier innovated in memory of the fire of 1751: he decided to replace everywhere the parquet floors with tiles, and developed a new system of incombustible brick vaults.

In July 1763, the king, as a reward, appointed him chief geographer of the king's camps and armies, governor of the War, Navy and Foreign Affairs hotels, and raised him to the nobility by letters patent established in Compiègne [..]

To these honors was added a salary of 12,000 pounds per year, half of which went to his widow and reversible to his children. It was the peak for Jean-Baptiste Berthier, who decided to have his portrait and that of his wife painted, signs of his notability. In 1765, he received the order of Saint-Michel, and two of his children have, as we have seen, illustrious godfather and godmother.

His new status giving him the privilege of being able to practice hunting, he associates the useful with the pleasant. At the request of Choiseul, then to that of the king, he established numerous hunting maps for most of the royal forests: Amboise, Rambouillet, Versailles, Marly, Saint-Germain, Sénart, Boulogne and Vincennes. This considerable work, unfinished during the Revolution, will be completed by his son, the future marshal.

[..] Having reached the peak of his career, Jean-Baptiste Berthier can look at his career with satisfaction. Despite his words: "I am no richer than when I was born in Tonnerre from the poorest citizens of this city", his rise is remarkable.

Beyond the titles and honors accumulated by the engineer Berthier, we will notice the extent of family and matrimonial alliances. The Berthier couple had twelve children, five of whom, along with the marshal, reached adulthood. Among those who survived, the two daughters, Jeanne-Antoinette (1757-?) And Thérèse (1760-1827) made excellent marriages [...] Of the four sons, three will be, under the Revolution and subsequently, illustrious soldiers: Louis-Alexandre marshal, Louis-César (1765-1819) and Victor-Léopold (1770-1807), major generals. The fourth son, Charles, born in 1759, nicknamed Berthier de Berluy to differentiate him from his elder Louis-Alexandre, died during the American expedition.

[..]

General Thiébault, then in garrison at Versailles, reports in his Memoirs of his meeting with old Jean-Baptiste in 1803.

"One morning, as I was having breakfast, a little old man who was still green came into my house, and who, in a deliberate tone, said to me:" Would you like, Monsieur le Général, to receive a visit from the father of the Minister of War, of General Berthier? " I hastened to answer that I would have hastened to offer this to him, if I had known that he was in Versailles, and I could have added if I had known that he was still in this world. He told me that he resided in Paris, but that, having come to Versailles on business, he had not wanted to leave it without seeing me. "From your place," he said, "I will visit, as is my habit, the Hotel de la Guerre which was built by me, where I lived so many years and where all my children were born. "I insisted that he do me the honor of having lunch with me, but he only accepted a cup of coffee, and the idea occurred to me to suggest that I accompany him to the Hotel de la Guerre, which he was delighted with. We left together, and if it had been about selling it to me, he could not have shown me this hotel in more detail and told me more exactly the history of all this construction from the cellars to the attics. When, after one hour, we reached the attics, he said: "This is the accommodation that I was occupying ", and having stopped in a rather small and more than modest room with alcove:" Here is ", he added with pride," where Alexandre was born. "And on this subject he recounted many memories to me. We would have been by the cradle of the Macedonian king that Macedonia could not have been complete. Convinced that he had kept this place for the last bouquet of what he wanted to show me and teach me, I thought I was at the end of my chore. I had already congratulated him on his legs which seemed to find in this building the vigor they had during the construction, when he warned me that what was most curious to see, was the roof. Immediately he passed through a window, and drawing me as if to a trailer, but running, climbing like a cat, he walks me from ridge to ridge, from gutter to gutter, at the risk of breaking my neck twenty times. "

Six months later he passed away. He had fulfilled his role of dynastic founder to the best of his ability. He endowed his descendants, either by marriages for his daughters, or by a perfect education for his sons. The fact that he gave Alexandre as a second name to his eldest son and César to his third son could presage Jean-Baptiste's military ambitions. He was not disappointed.

Franck Favier- Berthier, l'ombre de Napoléon

I hoped you enjoyed this!

#napoleonic#louis alexandre berthier#franck favier#berthier l'ombre de napoléon#jean-baptiste berthier#papa berthier#another tireless and skillfull berthier#the anecdote reported by thiébault made me smile#papa berthier would have whipped out the baby pictures if he could#also: proof that the ancien régime society wasn't that frozen that you couldn't make yourself a place#happy birthday berthier!

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Helfert, Joachim Murat, Chapter 1, part 2

Another brief snippet from a 19th century Austrian book on the final years of Joachim Murat.

Besides this great affair, or rather in the wake of it, there occurred all sorts of incidents of such a vexatious nature that one could indeed believe that the Paris court circles were specifically intent on making King Joachim uncomfortable with governing and pushing him to take a step similar to that taken by the Emperor's brother, Louis of Holland, over a year earlier. General Aymé, French by birth but in Neapolitan service, was arrested in Paris by the Duke of Rovigo's henchmen; La Vaugyon, the King's first aide-de-camp, was expelled from Paris and Naples at the same time; in Rome, General Miollis seized the Farnese property belonging to the Crown of Naples. In his own country, the king was as if under guardianship; the Napoleonic generals in Naples, Grenier and Pérignon, sometimes acted in a hostile manner against him, then again, which was still more hurtful to him, as if they were his well-meaning advocates and protectors. A journey undertaken by the queen to Paris at the beginning of October 1811 and her prolonged stay there seemed to bring the looming quarrel to a conciliatory conclusion: the seizure of the Farnese estates was lifted, Aymé was released from detention in Vincennes, Napoleon once again adopted a more friendly tone towards his brother-in-law. However, there were soon occasions for new misunderstandings and frictions, and what was even more alarming - just as with Louis and Hortense of Holland - discord was sown in Paris between the two spouses, who did not always agree in their views and were now also distanced from each other. Caroline seemed to feel at home in Paris and wanted her children to join her, but Joachim persistently refused.

Thus the Franco-Russian war approached, in the spring of 1812, where Napoleon could make good use of his brave brother-in-law, but also of his troops. It was not with an altogether light heart that Murat followed the call to the "Grande Armée", where the Emperor placed the command of the entire cavalry in his hands; for the fear did not leave him that his country might be stolen away from him behind his back, however valiantly he rendered service to the successes of Napoleon's arms. That this fear was not vain became evident from a remark of Alexandre Berthier, when Joachim, seeing that there was nothing to be done for the moment in the theatre of war in view of the sad outcome of the campaign, desired to return to his kingdom. "He considers him too good a Frenchman," insisted the Emperor's long-time confidant, "not to be convinced that Murat, if the good of France should require it, would not hesitate to offer his throne in sacrifice." When no answer came from Paris to Joachim's repeated requests for a leave of absence, he on his own authority placed the supreme command of the disrupted army that had been entrusted to him by the Emperor in the hands of Prince Eugène and returned to Naples, where the population, full of joy at seeing their worries about inclusion in the Grand Empire disappear, gave him an enthusiastic reception (January 1813). His relationship with Caroline, who had reigned during his absence, also seemed to have improved, although there were still many differences of opinion.

But his imperial brother-in-law had been injured beyond repair. If the situation had not been so critical, Napoleon - as he wrote to his stepson Eugène - would have court-martialled him to make an example. This did not happen, but the emperor ignored him completely; he did not write to him, but at the most to his wife. When he met the Neapolitan envoy in Paris, the Duke of Carignano, he inquired about Caroline's health, but never mentioned his brother-in-law. He sent back to him the Neapolitan regiments which had hitherto fought on the Iberian peninsula, and made absolutely no mention of if he were in further need of Murat's help in the war. The latter, for his part, seemed to know nothing of the French envoy at his court, only received Durand on solemn occasions like the representatives of all the other powers, and spoke in an unbound manner about the errors of warfare to which so fine an army had had to fall victim in the campaign of 1812.

~

As long as the power of Napoleon remained unbroken, no support could have been found for Murat on any side, if it had pleased the omnipotent one to let him descend again from the throne which he himself had bestowed upon him. Of all the European governments there had been at that time only two independent of the Emperor Napoleon: but Russia was then in firm league with France, England, on the other hand, was no less Murat's than Napoleon's enemy. Now things were different, and Austria was where the King first turned his eyes. His cabinet had been on particularly friendly terms with Austria since the official recognition from that side in the summer of 1811; Austria and its statesmen enjoyed many sympathies at Joachim's court, and it was Austria that at the present moment began to play an important role as a mediator in the great dispute, recognised by both sides. The personality of the Austrian representative at the Court of Naples was not without significance either; for Count Mier not only showed himself to be a prudent and confidence-inspiring diplomat, he also had an unmistakable affinity for the chivalrous king, whom he would soon assist almost as an adviser and confidant. Thus it came about that early in March 1813 Prince Cariati appeared at the Viennese Court as an extraordinary emissary of the King of Naples, where, although he had not been given any written authority for the time being, he was to establish confidential relations and in particular, in the event of the conclusion of a world peace, to strive for the general recognition of his monarch and the guarantee of his property. In addition, behind the back of the Neapolitan Minister of Foreign Affairs, Duca de Gallo, whom both King Joachim and the imperial envoy distrusted for good reasons, direct communication was maintained in the name and on behalf of King Joachim and Metternich in Vienna, whereby Murat declared himself prepared to do everything that would be demanded of him from Vienna and to arrange his actions in accordance with the signals he received from there. Throughout the month of April, Queen Caroline was still not in on the secret, but as time went on, she too was taken into confidence and now loyally adhered to her husband's cause.

I find the timeline quite interesting. If I’m not very much mistaken, this is also about the time when Montgelas in Bavaria starts to take up negotiations with the Austrians. And the Saxon king has fled to Prague and allegedly did the same thing there. So apparently at this time Metternich has already started a concerted effort to break up Napoleons overbearing empire which had become unsupportable for much of Europe. He will still do so in Dresden during his marathon meeting with Napoleon in June.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Berthier, Elisabeth, and Giuseppa.

Elisabeth is twenty-four, Giuseppa forty-three, and Berthier fifty-five. One can wonder about this cordial agreement, carried to an unusual degree, between two rival women. Because they will cohabit, Berthier not being able to bring himself to separate from Giuseppa, in the large hotel on the avenue des Capucines, but also in Grosbois where, if the Princess of Neuchâtel had her private apartments, the north pavilion was known to the inhabitants. of the castle under the name "apartment of Mrs. Visconti." Some will be shocked, such Augusta of Bavaria, the happy wife of Eugène de Beauharnais, viceroy of Italy, but also Elisabeth Berthier's first cousin. In a letter from Hortense de Beauharnais to her brother on August 23, 1809, she evokes the prejudices of Augusta, who has just met Giuseppa in Milan: "I received a letter from my sister-in-law who told me about Mme Visconti . She will no doubt have told you about it too: she cannot believe that her cousin is well with her and that she is even her intimate friend. This made her receive her coldly. The other, who is used to to be spoiled, will have been greatly astonished. I do not know what to answer my sister on that. She has the good fortune of being a princess without knowing a court and it is a great happiness. I was like her, but unfortunately, we learn every day, at our own expense, that we must welcome everyone. "

Hortense de Beauharnais is very severe here on the chapter of morals, she who will give birth two years later to the future Duke of Morny, born of her extramarital love with Charles de Flahaut, aide-de-camp to Marshal Berthier ... In addition, Augusta and Elisabeth were in different situations because if their marriage was organized without their consent, the first found love in Eugène de Beauharnais, the second came too late. Alexandre's heart was taken, and Elisabeth was not compelled to fall in love with a man without particular beauty and of her father's age. Consideration, tenderness, but no love, therefore no jealousy!

Franck Favier - Berthier, l’ombre de Napoléon

#napoleonic#franck favier#berthier l'ombre de napoléon#louis alexandre berthier#elisabeth wittelsbach berthier#giuseppa visconti#hortense de beauharnais#augusta wittelsbach de beauharnais#eugène de beauharnais#hortense's judgy side

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

I will have to read this chapter!

About Hoche: As far as I know, and much more likely than poisoning, he died of tuberculosis. Before dying, he recommended Gouvion Saint-Cyr as his replacement, but Lefebvre was designated instead.

About Marmont: He wrote a book called "L'Esprit des institutions militaires". It can be found on Gallica. I read it a little while back, and it appears to me to confirm what Soult stated about Marmont's theoretical knowledge. I think the book had some success at the time. It has chapters about just about anything to do with armies and their support systems.

About Marceau: He was only 26 when he was killed, too young to mature into a major military figure.

About Berthier: Although I strongly suspect Berthier of being a snob, Naps made it too easy for marshals and generals to hate him by making him his sometimes hatchet man and fall guy, all the better to deflect blame away from himself.

Kléber: As far as I know he was extremely capable; I am not surprised Soult admired him.

Soult on several French officers

This is taken from the book »Life of General Sir William Napier«, Volume 1. Soult, while in England for the coronation of Queen Victoria, talk to British historian Napier, who wants to know his opinion on several French officers. As usual, Soult is not very forthcoming, his statements are rather brief. There are longer ones on Hoche, on Napoleon and on Joseph Bonaparte, however, that I might post separately if there’s interest. Or you can just look them up yourself under the above link (page 505, bottom, ff, »Generals of the Revolution«). For once, it’s all in English. So, here are Soult’s verdicts on:

MARCEAU. “Marceau was clever and good, and of great promise, but he had little experience before he fell.”

This general I had to look up: He died from his wounds in Austrian captivity in 1796.

MOREAU. “No great things.”

AUGEREAU. Ditto.

JUNOT. Ditto.

GOUVION ST. CYR. “A clever man and a good officer, but deficient in enterprise and vigour.”

MACDONALD. “Too regular, too methodical; an excellent man, but not a great general.”

NEY. “No extent of capacity: but he was unfortunate; he is dead.”

VICTOR. “An old woman, quite incapable.”

There are some funny scenes with this marshal that Brun de Villeret describes in his Cahiers. Apparently, Brun needed to go calm down Victor on several occasions.

JOURDAN. “Not capable of leading large armies.”

MASSENA. “Excellent in great danger; negligent and of no goodness out of danger. Knew war well.”

That’s a little less praise for Masséna than in his memoirs. But Soult is all around bragging a lot in this conversation, though it’s hard to tell how much of it may have been jokingly. (Then again – Soult and joking? Probably not.)

MARMONT. “Understands the theory of war perfectly. History will tell what he did with his knowledge.” (This was accompanied with a sardonic smile.)

And of course refers to Marmont’s alleged betrayal of Napoleon in 1814.

REGNIER. “An excellent officer.” (I denied this, and gave Soult the history of his operations at Sabugal.) Soult replied that he was considered to be a great officer in France; but if what I said could not be controverted as to fact, he was not a great officer, his reputation was unmerited. (The facts were correctly stated, but Regnier was certainly disaffected to Napoleon at the time; his unskilful conduct might have been intentional.)

DESAIX. “Clever, indefatigable, always improving his mind, full of information about his profession, a great soldier, a noble character in all points of view; perhaps not amongst the greatest of generals by nature, but likely to become so by study and practice, when he was killed.”

KLEBER. “Knew him perfectly; colossal in body, colossal in mind. He was the god of war; Mars in human shape. He knew more than Hoche, more than Desaix; he was a greater general, but he was idle, indolent, he would not work.”

BERTHIER and CLARKE.

“Old women - Catins. The Emperor knew them and their talents; they were fit for tools, machines, good for writing down his orders and making arrangements according to rule; he employed them for nothing else. Bah! they were very poor. I could do their work as well or better than they could, but the Emperor was too wise to employ a man of my character at a desk; he knew I could control and tame wild men, and he employed me to do so.”

You could do Berthier’s and Clarke’s job easily, huh? Well, I could name one battle of Waterloo that says otherwise, Monsieur! (So does Napier, btw.)

I think between Berthier and Soult all bridges were burnt. And it really may have been not only from Soult’s side. I can quite imagine how somebody like Berthier, “l’homme de Versailles”, coming from a noble background and placing great value on politeness and good manners, would react to Soult.

#jean de dieu soult#louis-alexandre Berthier#auguste viesse de marmont#lazare hoche#napoleon#napoleon's marshals#napoleonic era#napoleonic history#napoleonic wars#jean-baptiste kleber

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

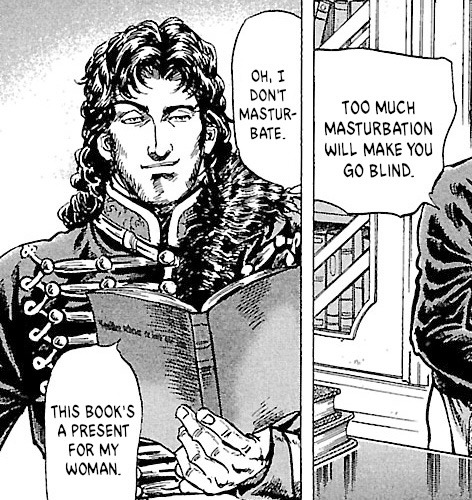

Reblogging this here from Murat's RP blog. Because oh my god.

RP Murat reacts to Hasegawa Murat:

....

Is that supposed to be me?

Oh my god, look at me!

My compliments to my artist! He's made me so handsome and perfect here! "A captive of your love"? Yes, that's me, really, what's so terrible about saying that?

I can look at myself all day! Tetsuya Hasegawa has captured my essence, the essence that is Murat! 😘

I respectfully disagree. The key to a healthy and balanced life is taking some time out for yourself, if you get my meaning. Like with anything else, it's better with friends!

I breathlessly await your next installment, Monsieur Hasegawa. You've given me quite the introduction into this tale of your illustrated epic!

#tetsuya hasegawa#napoleon age of the lion#manga#this chapter has berthier in it too#oh my god berthier#napoleon age of the lion vol 6 ch 037#napoleonic manga#napoleonic shitpost

20 notes

·

View notes