#third battle of artois

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

World War I (Part 37): The Rest of 1915

A series of meetings was held in France over July-August, to decide what should be done next on the Western Front. The first meeting was at Calais on July 6th, and those attending included Asquith, and the French War Minister Alexander Millerand.

Joffre presented his plans for an autumn offensive. Kitchener was very much against it (he was almost scornful), and so was the new First Lord of the Admiralty, Arthur Balfour (who was also a former prime minister). The next day, Kitchener and the civilians had left, and Joffre & JF met at Chantilly. They agreed that Joffre's plans should go ahead anyway.

A larger meeting was held on July 17th. At this one, Douglas Haig objected to Joffre's plans. He'd examined the ground where the offensive was to be carried out by his army, and now he stated that it was too open – his troops would be too exposed. Also, he didn't have enough artillery. Joffre didn't listen, though.

In mid-August, Kitchener was at the last of these meetings (and that's when he heard about the recent failure at Gallipoli). He was there not only to sort out details of the western offensive, but also because things were getting even worse in the east.

Eastern Front

For generations, Russia had forced most of its Jewish population to live in eastern Poland, in ghettos and shtetls (small Jewish towns). They were mostly prevented from becoming farmers, or entering academic professions.

In late 1914, Russia had driven over 500,000 of them from their homes, claiming it was for security concerns. Many died in the harsh winter. In early 1915, Cossacks drove another 800,000 from their homes in Poland, Lithuania, and Russia's Courland region. Often, they weren't even allowed to take whatever possessions they could carry or take by cart.

General Nikolai Yanushkevich directed Russia's final military withdrawal from Poland. The tsar had forced Grand Duke Nicholas to accept him as his chief of staff early in the war, and he was a protégé of the corrupt War Minister Vladimir Sukhomlinov (who himself was one of the tsar's favourites).

In Poland, Yanushkevich adopted a “scorched-earth policy”. All inhabitants (Jewish or not) were put to flight. Many died from starvation and disease (cholera, typhoid & typhus); the total death toll is unknown. Food stores were destroyed; machinery was taken eastwards on wagons & railcars. Four million cattle were killed, which led to a meat shortage that would last longer than the war did.

Not long after capturing Warsaw, Germany took Novo Georgievsk, a fortress city. They took 90,00 soldiers POW (including 30 generals) and captured 700 guns. Only days later, they took Kovno (an equally important city), and another 1,300 guns.

By now, they'd taken over 700,000 Russian POWs, and the Austrians nearly as many. They were still marching eastwards, and the Petrograd government was in a high state of alarm. They issued a decree saying that the families of POWs would receive no government assistance; and soldiers who surrendered would be sent to Siberia after the war.

Reports of what was happening were beginning to arrive in the west. General Sir Henry Wilson was the British officer closest to the French high command. He was a very good manipulator, and he found ways to use the eastern disasters to help his French friends. He warned London that if they didn't fully support France's next offensive, then that could lead to Joffre & Millerand losing their positions, and to France making a separate peace.

So Kitchener told Hamilton that he shouldn't expect any more troops to be sent to Gallipoli. He ordered the BEF to completely support Joffre's offensive, “even though, by doing so, we suffer very heavy losses indeed.” Kitchener expressed no hope that the offensive would actually succeed – for him, the point was to keep the Entente together.

In the last days of August, the tsar removed Grand Duke Nicholas from his position as head of the Russian armies. He put himself in that position instead, to the horror of his ministers. He explained to the Grand Duke in a letter that he believed it was his “duty to the country which God has committed to my keeping” to “share the burdens and toils of war with my army and help it protect Russian soil against the onslaught of the foe.” The Duke was relieved when he heard the news, saying, “God be praised. The Emperor releases me from a task which was wearing me out.”

This was the last of a number of command changes that the tsar had made that summer (and the worst one). War Minister Vladimir Sukhomlinov had gone too far with his corruption – for example, when the army's chief of artillery begged him for shells, telling him that Russia would have to make peace otherwise, Sukhomlinov told him to “go to the devil and shut up.” In late June, the tsar finally realized that he would have to go, and replaced him with Alexei Polivanov, a capable and energetic general.

Polivanov immediately began a program of reforms – he made major improvements to the supply system; he formed committees to take responsibility for food, munitions, transport, fuel and refugees; he was willing to work with Russia's national assembly, the Duma.

The tsar made other command changes as well, and almost everyone was glad of them, except Tsarina Alexandra, his wife. She believed that the tsar should become more autocratic in response to Russia's problems – that it was the only solution to them. Many ministers begged the tsar not to become commander in chief, but she persuaded him to ignore them, and later wrote, “You are about to write a glorious page in the history of your reign and and Russia.” The way she saw it, the ministers had questioned not only his decision, but his authority as an autocrat; they were enemies of the crown and should be dismissed.

Tsar Nicholas explained his decision in a letter to Paléologue: “Perhaps a scapegoat is needed to save Russia. I mean to be the victim. May the will of God be done.” What he didn't think of, though, was that by being so far from the capital, the increasingly widespread belief that the government was really controlled by the tsarina & Rasputin would grow even more.

The British & French were pleased by the tsar's decision – they saw it as evidence that he was committed to the war. They were also pleased with the man he'd chosen as his chief of staff – General Mikhail Alexeyev, an experienced commander & strategist. The Germans, too, were glad of the tsar's new role, because they'd come to respect the Grand Duke's abilities in that position.

Russia abandoned the cities of Brest-Litovk and Bialystok, and by early September they'd withdrawn to the Pripet Marshes, a remote region which was treacherous and mostly uncharted. Falkenhayn refused to follow them there, and ordered all eastern commanders to stop offensive operations. He then began preparing to move several army corps back to the Western Front, and to conquer Serbia. But Conrad & Ludendorff ignored his instructions. Later, they would claim they had misunderstood him.

On August 31st, Conrad had began an offensive that would encircle 25 Russian divisions, and then drive them eastwards into Ukraine. It began well, but then went downhill. One of the Austrian armies captured the city of Lutsk, but then was taken in the flank by a Russian force that had hidden itself in marshland grasses. Further disasters followed. Eventually, Falkenhayn had to take two of the divisions that were preparing to invade Serbia, and send them to help. During September, Conrad lost 300,000 men.

Meanwhile, Ludendorff was continuing his Courland campaign. His troops captured Vilna (the capital of Lithuania), and the Petrograd government panicked and began preparing for flight. But the Germans had taken 50,000 casualties in capturing Vilna, and so Ludendorff decided not to advance on the Russian city of Riga. He halted the campaign, and settled down to organize & administer his conquests for the winter.

Cracks were appearing in the Hindenburg-Hoffmann-Ludendorff alliance. Max Hoffmann was one of the best generals on either side, and he was now incredibly frustrated with the state of things. He blamed Falkenhayn for failing to keep going in the east. But he also was angry at Ludendorff for attacking too directly at Vilna, and thereby suffering so many casualties.

Hoffmann was contemptuous of Hindenburg, believing him to be passive and nothing more than a figurehead. He wrote, “On the whole Hindeburg no longer bothers himself with military matters. He hunts a good deal and otherwise comes for five minutes in the morning and evening to see how things are going. He no longer has the slightest interest in military matters.” Another general on Ludendorff's staff said that, “Hindenburg himself is becoming a mere stooge.” Hindenburg was spending a lot of time having portraits of himself painted, and writing to his wife.

Later in the year, Ludendorff & Falkenhayn met at Kovno, to join the kaiser's ceremonial celebration of their victories. Falkenhayn asked, “Now are you convinced that my operation was correct?” Ludendorff replied, “On the contrary!” Russia hadn't surrendered, or sued for peace – they were, as before, merely being pushed eastwards. Falkenhayn was heard to say that he would need to court-martial Ludendorff when the war ended.

Western Front

Joffre's autumn offensive began on September 25th. It actually consisted of three distinct offensives. One of them was the Second Battle of Champagne, in France's Champagne region west of Verdun, against the southern part of the original German line. There were 27 French divisions with 900 heavy guns and 1,600 light guns (Joffre had stripped these guns from the border fortresses), against 7 German divisions which were stretched thinly across 58km of front.

The Third Battle of Artois was in the same place as the last Artois offensive. Here, Ferdinand Foch commanded 17 French divisions. The German line ran north-south, and had only 2 divisions.

The third offensive was a bit north of Artois, at Loos. Here, there were 6 British divisions against only one German division. It was part of the Third Battle of Artois.

Basically, this (Artois + Loos) was the spring offensive on a much larger scale. The goal was to cut off the Noyon salient, break the railway connecting the two ends of the German front, and force a general withdrawal.

But back in the spring, the Germans had shown that they could defend very well even when greatly outnumbered. During the summer, they'd been setting up new lines far to the rear, beyond the reach of the Entente artillery. They'd connected these lines with perpendicular trenches and tunnels. They were well-equipped with heavy artillery, and – very importantly – very good at using it. The Germans were learning to position their machine guns to neutralize any enemy attackers who had survived the artillery.

The British weren't very optimistic about Joffre's offensive, and that was partially why. Kitchener had insisted on full British participation, even though he didn't believe it would succeed. Part of his reason for doing so was that there was talk of putting all Entente forces under a single commander, and if he didn't co-operate, he worried that he wouldn't be given that job.

JF was usually eager to attack, but he wasn't in this case. He warned that he had less than 1/3 the number of divisions needed for victory, and that the ground they were going to advance over had far too little cover. But he didn't complain too much, also for political reasons – JF believed thast it was only Joffre & Foch's support that was stopping the London government from removing him from command, so he had to support this offensive.

General Sir Henry Rawlinson was the commander of the corps that would lead the British attack. Before it began, he said that “it will cost us dearly, and we will not get very far.” Pétain was in direct charge of the Champagne offensive, and his attitude was much the same.

Strangely, Douglas Haig was the only optimist, even though he'd initially been against it. His opposition had been because the BEF would only have 117 heavy guns to prepare their advance on a 8km-wide front (the Champagne offensive, in comparison, would have over twice that many per mile of front), and the lack of protective cover. But then it was decided to precede the offensive with a release of chlorine gas, and he was much happier about it all. In fact, he was so encouraged by this decision that he had tower built, from which he would observe his troops attacking the German defenses. (This would be the first time the British used poison gas during WW1.)

Before the battle began, King George V visited the BEF headquarters, and borrowed a general's horse to review the troops. According to a corporal in the Sherwood Foresters regiment, this is what happened:

“The King rode along the first three or four ranks, then crossed the road to the other three or four ranks on the other side, speaking to an officer here and there. Our instructions had been that at the conclusion of the parade we were to put our caps on the points of our fixed bayonets and wave and cheer. So that's what we did – 'Hip, hip, hooray.' Well, the King's horse reared and he fell off. He just seemed to slide off and so of course the second 'Hip, hip' fizzled out. It was quite a fiasco and you should have seen the confusion as these other high-ranking officials rushed to dismount and go to the King's assistance. They got him up and the last we saw of him he was being hurriedly driven away.”

The Third Battle of Artois began in the French sectors with four days and nights of shelling. This destroyed the Germans' first line, and many of the troops in it; however, it also told them that something big was coming. When the attack began on the morning of September 25th, it went smoothly at first for the French.

But in the British sector, the winds were uncertain, and Haig wasn't sure if he should release the chlorine gas or not. Meanwhile, the troops were in the front-line trenches, and being given all the rum they could drink, while waiting for the order to advance. At 5:15am, the winds finally seemed right, so Haig approved the gas release, and climbed into his tower. But the wind soon shifted backwards, thus bringing the gas back to the British. Once it had dissipated, those who still could began to advance. Soon, they were making rapid progress.

But then things started to go wrong all over the place. Over in Champagne, the French had destroyed the German first line, and advanced through it, reaching the second line much sooner than they'd expected – and this success was not to their advantage. They entered the trenches just as an artillery barrage from their own side attacked them – it was supposed to clear the way for them before they got there. The survivors had to retreat. By the time they could resume the attack, German reserves had come forward. They had many machine guns with them, and quickly recaptured what the French had had to give up.

These reserves included two of the corps that Falkenhayn had recently sent to the west. Falkenhayn himself was on the scene, because he was so worried about Germany's weakness there, and he helped keep the defenses intact.

Earlier, when the French had been rapidly advancing, he'd arrived at the German 3rd Army headquarters, where the chief of staff was preparing to order a retreat. Falkenhayn sacked him, and ordered that the troops hold their ground at all costs while waiting for the reinforcements that he knew were going to arrive soon.

At Artois, the French captured the crest of Vimy Ridge for the second time – but yet again, only briefly. An intact German second line stopped them, and eventually drove them back.

At the beginning of the offensive, Joffre had regarded the Champagne battle as the important one, and the Artois battle as relatively unimportant. The British attack at Loos was intended only as support for the French at Artois. But now, he began to be manipulative. He now wanted to end the Artois attack, because it had no chance of getting anywhere. So he stopped it, but pretended to the British that he hadn't. Now the British were fighting alone at Loos.

They did well at first, passing easily through the first German line, which had been wrecked. They also broke through the second German line (although taking heavy losses). Ahead was open ground, and they could push forward into open country like they'd been wanting to do for ages – but. They needed reserves for that, and there were two problems. 1) JF had placed the BEF's general reserves too far to the rear (as much as 16km back). 2) Haig hadn't held part of his army back in reserve, which was the usual military practice.

It took many hours to get the general reserve to the front lines. And by then, the Germans had filled the hole, and were attacking the British with machine guns. The British attacked again, but it was a slaughter – 7,861 British troops & 385 officers were killed, while German casualties were zero. When the British finally withdrew, the Germans let them go. A later German history of the battle would record that the machine-gunners were “nauseated by the sight of the massacre of the field of corpses.”

A British soldier wrote, “Coming back over the ground that had been captured that day, the sight that met our eyes was quite unbelievable. If you can imagine a flock of sheep lying down sleeping in a field, the bodies were as thick as that. Some of them were still alive, and they were crying out, begging for water and plucking at our legs as we went by. One hefty chap grabbed me around both knees and held me. 'Water, water,' he cried. I was just going to take the cork out of my water bottle – I had a little left – but I was immediately hustled on by the man behind me. 'Get on, get on, we are going to get lost in no man's land, come on.' So it was a case where compassion had to give way to discipline and I had to break away.'

Joffre ordered the Champagne fighting to continue, and it did so until November. Eventually, Pétain simply ignored the orders to continue. The Second Battle of Champagne had 143,000 French casualties, and 85,000 German casualties (including 20,000 POWs).

At Artois & Loos, the British took 61,000 casualties (including 2 generals and 28 battalion commanders), the Germans 56,000, and the French 48,000.

Joffre told the Paris newspapers that the German losses had been far greater than the French (which wasn't really true), and that the campaign had been a great success. In reality, the Germans had stopped the Entente from achieving anything, and inflicted huge losses on them, despite being hugely outnumbered. Also, it was now obvious that the Entente couldn't spare any troops for Gallipoli, or other theatres. Joffre's credibility was further damaged (at least among the insiders who knew what was really happening). However, he stayed in his position.

JF, on the other hand, did not. During the Battle of Loos, Haig had complained to his friends that it was JF's incompetence that had prevented victory. Later, he declared that, “If there had been even one division in reserve close up, we could have walked right through.” Of course, Haig was to blame for this as well. But JF panicked and falsified the official record of orders issued during the battle. Haig learned of this, and made sure the King heard of it. The King then intervened with Asquith, who gave JF the opportunity to resign. JF realized he had no choice, and agreed. Haig was promoted to the position (which he'd wanted since before the war began). JF returned to England, and was made Viscount Ypres.

Serbia

The fighting was winding down on the Western Front, and winter settling in on the Eastern Front. Attention turned to the Balkans and the Aegean.

During the summer [June-Aug], both sides had been trying to get Bulgaria to join them (much like they had Italy). And like Italy, Bulgaria's government was basing their choice on whoever could give them the most territory. Edward Grey had tried to win Bulgaria over by offering them many concessions, but what he couldn't give them was the land that Serbia had taken from Bulgaria in the Second Balkan War (because Britain was Serbia's ally). In early September, they joined the Central Powers.

Even before Joffre's autumn offensive began, it was obvious that Germany & Bulgaria were preparing to invade Serbia. If Serbia fell, then the Entente would lose their tiny foothold in south-eastern Europe (taking the Gallipoli failures into account). Also, Russia would be even more demoralized, and Greece & Romania might join the Central Powers as well.

So Entente troops had to reach Serbia somehow. This meant Salonika (Thessaloniki), a Greek port that had been a possible alternative to the Dardanelles earlier in the year.

By the end of September, the French had several divisions on the way to Salonika (one division had been removed from Gallipoli). General Maurice Sarrail commanded them. He'd been removed from command on the Western Front, but because of his political connections, the government had had to find him another position elsewhere.

Britain didn't want to leave the Balkans to the French, so they sent the 10th Division from Suvla Bay to Salonika. For a while, they hoped to persuade Russia to send troops as well. On October 3rd, Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov said that was impossible – Russia was losing 235,000 men a month on average, and its pre-war professional armies had basically been wiped out.

The British & French troops landed at Salonika on October 5th. On the 7th, German & Austrian troops (commanded by Mackensen) crossed Serbia's northern border. On the 9th, two Bulgarian armies arrived from the east. One pushed the Serbs towards the German/Austrian forces; the other cut the rail lines that connected Salonika to Serbia. The Serbian army was trapped between two enemy forces, coming from two direction. They fled towards the sea, and civilians fled with them.

A mass of refugees tried to cross Albania's mountains, and tribal enemies, eager to settle old scores, attacked them. It was chaos, and a horrific situation. Serbia lost 250,000 troops. Only 150,000 managed to reach the Adriatic Coast, and only half of them were fit for further service. British ships took them to camps on the island of Corfu.

Serbia had fallen. It was the final straw, and the French government fell. Premier René Viviani was replaced by Aristide Briand. The Minister of War Alexandre Millerand was replaced by General Joseph Gallieni, who had helped Joffre save Paris in 1914. Now Joffre was reporting to the man who had been responsible for his getting the Commander-in-Chief position the year before, and whom he'd tried to sideline before & after the Battle of the Marne, due to jealousy. Joffre's critics hoped that Gallieni would dismiss him, but this didn't happen: instead, Gallieni yet again defended and protected him.

Gallipoli

On October 11th, Kitchener cabled Hamilton, asking him how many troops he thought would be lost in a withdrawal from the Gallipoli beachheads. Hamilton replied that it would probably be at least half of them. Kitchener then removed him from his position as the Gallipoli commander.

Edward Grey promised Greece the island of Crete if they'd join the Entente. But Greece had been intimidated by the failures at Gallipoli and in Serbia, and declined.

In mid-November, Kitchener travelled to Gallipoli himself to see the situation, and decided that they had to evacuate. He returned to London, to find that Asquith had reduced his authority even further during his absence. The committee responsible for war strategy was now reduced to five people, and Kitchener was no longer one of them. General Sir William Robertson was brought back from France, and appointed chief of the imperial general staff, the new War Committee's chief adviser on military operations, and the channel through which the government's instructions would be sent to the BEF. Kitchener went to Asquith and offered his resignation, but it was refused – he was still an important propaganda figure.

Winston Churchill wasn't on the committee, either. Since being fired as First Lord of the Admiralty, his only position was the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster – a meaningless position in which his only responsibility was to appoint county magistrates. Churchill left the government and entered the army as a Major (although he'd hoped to be made a Brigadier General). When he arrived on the Western Front, he had with him a servant, a stallion & groom, heaps of luggage, and a bathtub with its own boiler. A limousine took him to a château, where he would live. By January, he would be serving on the front as a competent battalion commander.

On November 23rd, the War Committee approved a detailed Gallipoli withdrawal plan, worked out by Hamilton's successor. The retreat was carried out over the next month, in total secrecy, and was the closest thing to an actual military achievement since the Battle of the Marne. The Royal Navy worked together with the soldiers on the beaches, getting men away in darkness. Of course, the more men that were evacuated, the more vulnerable those still remaining were. On January 7th, 1916, Sanders ordered an attack on the 19,000 British troops still left at Cape Helles.

But the Turks under his command refused to attack. Even when the officers threatened them, and then shoved & slapped them, they would not move. Mustafa Kemal wasn't there – his health was wrecked, and he'd been sent away in December.

36hrs after the mutiny, the last Australian troops were evacuated safely. The Gallipoli Campaign was over, after killing at least 87,000 Turks (the real figure is probably higher). 46,000 Entente troops had died. Total casualties (both sides) were around 500,000.

#book: a world undone#history#military history#ww1#dardanelles campaign#gallipoli campaign#battle of warsaw (1915)#courland campaign#siege of ovogeorgievsk#second battle of champagne#third battle of artois#battle of loos#serbian campaign#russia#poland#serbia#turkey#gallipoli peninsula#judaism#antisemitism

1 note

·

View note

Text

best years | s. holland

the third fic from the calm series!!! i hope you guys like this one as much as i did :)

this is lowkey also one of my favourite songs off the album

warnings: mentions of drinking and intoxication

sam knew that you would be at the wedding. paige had warned him in advance that you were going, and that if he wanted them to change anything about their wedding so things wouldn’t be awkward, they would. but sam decided that it would be okay, he decided that he would force himself to be okay seeing you happy. it had been a little over a year since the two of you broke up, but he was still hurt over the multiple relationships that you had during that time. he wasn’t completely sure how he felt about you, but he knew he still loved you. to what extent? he was unsure.

you knew that sam would probably be at paige and bryce’s wedding, they were the ones who set you two up almost five years ago, and the breakup didn’t stop either of you from being friends with them. it had been more than a year since you both had called it quits so you thought you would be okay seeing him. no one said the two of you had to talk.

it was during the reception where everything changed. you found out that you and sam were sitting at the same table, but luckily all of your shared friends were there. mid-dinner, they pulled paige to the dance floor for the bouquet toss. all the single women gathered in a group, the ones most excited at the front. you were somewhere off to the side, not really wanting to catch it, but paige was one of your best friends, so you played along just for her. she had her back facing the group of girls, and as she threw it back, you ended up catching it. ‘how ironic’, you thought. the one thing you didn’t want happening, happened. you didn’t believe that you were going to get married next just because you had caught the bouquet, but part of you hoped you would find someone, even if you didn’t want to admit it.

sam watched you catch the bouquet, how could he not? everyone was staring, but it gave him the chance to get a look at you. he thought that you would’ve brought someone along with you, and was surprised when he saw you participating. you looked the same as you did when you broke up, just a little more tired. he could tell. he spent four years of his life learning how to read you, and he never lost any of his skills. he could tell that as you caught the bouquet, something he knew you never intended to do, you secretly were excited. there was something else about you that he couldn’t pick up on. he watched as you stood there in shock, holding the bouquet of mixed flowers, your pale pink dress hung still around your body. there was something there, something he couldn’t pick up on.

the dinner continued, music playing as everyone conversed at their tables. the wedding reception wasn’t quite large, but it wasn’t a small reception either. everyone seemed to know of each other, but they didn’t necessarily know each other the way that friends did. you and sam sat at the same table, a table that consisted of all of your shared friends. it made sense why you two sat together, despite everyone knowing that this was the first time the two of you had even seen each other in more than a year.

“wait, y/n, what happened to nick?” alex asked. he was one of your first friends out of the whole group, then introducing you to bryce, and the rest of the friend group. things got awkward after you and sam broke up, but alex still tried to keep everything the same. he watched as you put your wine glass down, then tapping your fingers against the stem of the glass.

“we ended it a few weeks ago, it wasn’t working out,” you said. you didn’t want to talk about an ex while sam was right there. yes, life went on and you were allowed to have other relationships after him, but it was out of respect. it didn’t seem right to talk about your most recent relationship right in front of your last long-term boyfriend. “anyways, enough about him, what about your boyfriend alex?” alex blushed, and continued to talk about his boyfriend, ollie. everyone at the table smiled seeing alex go on and on about ollie. you all thought that they would get married, but you all also thought that you and sam would get married. maybe not all of your predictions were correct.

you smiled as alex continued to gush, but all you could think about was nick. why did you end things with him? things weren’t working out was what you had said, but there had to be more to it. your eyebrows furrowed a little, something sam had caught out of the corner of his eye. even though it had been more than a year since he’d seen you, he couldn’t help but note every little detail about your body language. he couldn’t help but realized he was still madly in love with you, and seeing you only made it worse.

dinner finished shortly after, and everyone proceeded to dance. you were at the bar, getting another glass of wine, while sam was in front of you getting a beer. you had spent all night avoiding each other, but as the two of you were alone at the bar together, you couldn’t help but strike up a conversation.

“sam, hey,” you said as he was about to walk away after getting his bottle of stella artois. “i just wanted to make sure we’re okay. i know our break up sucked for both of us and i wanted to say sorry.” it was the very least you wanted to do. you wanted to make up with him, you wanted to be on good terms with him. he was your best friend before you two started dating, and losing him hurt more than any breakup you’ve ever been through.

“uh, yeah. honestly, we’re good,” sam said. he smiled and nodded, then worked his way back into the crowd of people, leaving you alone. you knew it was going to be awkward, you knew it was next to impossible to get him back as your best friend. but what you didn’t know was that as he walked away, everything started to make sense. why you couldn’t stay in relationships for too long, why none of the guys you dated ever made you feel the way you wanted to feel - you wasted so much time looking for sam in all of those guys.

paige noticed you standing at the bar alone, and she could tell your emotions and thoughts were washing over you like a tsunami. she walked over to you, saying nothing as she engulfed you into a hug. you melted in her arms, feeling understood by her despite not saying anything. she somehow just knew that something was happening with you and sam, but she couldn’t place her finger on what.

“tell me everything.” was all paige said, and it was all she needed to say for you to voice all your thoughts. everything from your first relationship after sam, to how you never felt like you fully clicked with the guys you dated. you talked about how even though you never realized it, you looked for sam in all of those guys. you tried to fill his shoes but were never able to. you would never be able to replace sam, and seeing him walk away from you the way he did less than half an hour ago was enough to make you realize this.

“oh honey,” paige said, then ordering more drinks for the two of you. “he hasn’t been doing too well either.” you looked up at her in surprise, and she just gave you a sympathetic look. “he’s been trying to get over you, but sam just can’t.” you furrowed your eyebrows at your bride friend standing right in front of you. her words confused you. he seemed happy, he seemed like he was doing alright, but you remembered that looks can be deceiving.

“pai, what should i do?” you downed the rest of the wine that was sitting in your glass. the slightly tart liquid flowing down your throat, the alcohol that was there prior helping you relax.

“i think you know what you should do,” was all paige said in response. with that, she left you alone with the bartender. you ordered another drink, needing more liquid courage. you had to go talk to sam. what you were going to say was still unknown to you, but you sat there until you figured it out.

when sam walked away, he walked over to bryce and alex. they immediately knew what he was thinking. the two boys had watched him briefly talk to you and walk away. they had watched as he had an internal battle with himself and his thoughts, wanting to talk to you but also feeling that you didn’t need him anymore. but unbeknownst to him, you needed him more than you needed air in your lungs, or blood flowing through your veins. you needed him like the ocean needs the pull from the moon to create waves. he was your other half, and if soulmates were real, you were certain that he was yours.

“you know you have to talk to her, right?” alex said. alex may not have known that you secretly were still hung up over sam, but you didn’t realize it until that night either, but he knew that there was still something there.

“mate she’s had so many other boyfriends after we broke up, she doesn’t care about me.” sam sighed as he voiced his thoughts. sam genuinely believed that he was easy to replace. he ran a hand through his hair, pushing the few pieces that fell around his eyes towards the back of his head.

“don’t close any doors before you’re fully sure.” bryce said. the other two boys standing in that group smiled at him.

“so you’ve only been married for an hour and a half and suddenly you’re really wise. okay bryce,” alex said, causing everyone to laugh.

paige walked over to stand beside bryce, him instinctively putting his arm around her waist. they shared a look, one that the other two were unable to read. they had been speaking through their expressions, speaking a language that only the two of them were able to understand. bryce smiled, and excused the two of them, asking alex to join them, which he did. sam and alex knew something was up, but they didn’t know what. as sam was left alone, you looked over at him standing there.

“it’s now or never,” you said quietly to yourself. you got up and walked over to him. “can we talk? please?” was all you said. not knowing what to do, sam just nodded and followed as you lead him to a quiet part of the venue. a little seating area outside, away from everyone in the reception hall. the two of you sat together, on either sides of the bench. an awkward silence fell over the two of you. suddenly you were frozen, not really remembering what you wanted to say.

“i won’t lie, i am a little bit drunk right now. but i just wanted to say i’m sorry for everything that happened with us. you were my best friend and our breakup hurt more than anything i’ve ever experienced.” you avoided making any eye contact with him, looking down at your hands while you were talking. it made it hard for sam to read you, but with every bone in his body, he knew you were being sincere.

“it’s okay i guess. people just grow apart, it’s just life,” he said. he internally kicked himself for saying that. he wasn’t okay, he missed you more than he misses harry when he’s away.

“no, it’s not okay. i spent the past year wasting so much time on people that reminded me of you, and i only realized that now. our breakup was the worst thing that happened to me. i subconsciously tried to replace you, but i was never happy sam. i needed you, and i still need you.” you looked up at him for the first time in more than a year. you studied his face. you looked at his freckles, some were fading since he hasn’t been in the sun for a while, but they were still all mostly there. you looked up at his hair, still cut the way you liked it. his hair fell over his forehead, split in the middle, some of the curls falling just over his eyebrow. you then briefly looked at his lips, looking away to study the rest of his features. his chocolate brown eyes were the last thing you went over, looking at how they reflected the moonlight. you could tell that he was still processing what you said, so you two sat in silence.

sam felt like the world was spinning around him just from your words. yes, he knew you were drunk, but drunk words were sober thoughts, right? it wasn’t as if your words could be that far from the truth, you were best friends before you started dating, and despite him being your boyfriend, he was also your closest friend at the time. the breakup ended an almost four year long friendship, and losing a friend as close as you two were hurt more than any other relationship.

“do you really mean that?” sam mustered out after what, to you, felt like hours. you nodded.

“i meant everything i said.” your confirmation was enough for sam to let down whatever guard he had put up. he had made eye contact with you, keeping it. he always knew your eyes were beautiful, but actually studying them in the moonlight for the first time in less than two years made him remember how in love with you he was and still is. “sam, i know you may not feel the same way, but i still am in love with you. i hate that it took me this long to realize it, but our breakup was a mistake.”

sam’s heart stopped. he had been waiting for you to say those words. those words changed everything.

“i still love you too y/n.” your face lit up, a sight that sam had missed seeing. his words brought you immense hope, hope that you could get back together. sam watched as you suddenly tried to put everything together. he knew you were wondering why he still loved you if he watched you go on and date other people. “i know you’re thinking i shouldn’t still love you, but i really do.” it was as if he could read your mind.

he gently grabbed your hand, intertwining your fingers together, in an attempt to help you relax. his touch felt like sparks had spread across your skin. the feeling of finally holding his hand satiated a fire inside of you, one that you had tried to put out with other people but was never able to.

“what you did when we were broken up doesn’t concern me, you’re allowed to live your life y/n/n. i just care about you still loving me.” sam’s voice was soft. although you could still hear the music playing from the reception hall, all you heard and focused on was sam.

“i’m sorry it took me dating other people for me to realize that you’re all i want.” he pulled you closer to him, your thighs and knees touching. he cupped your cheek with his hand, making you look up at him and only him. sam gave you a small smile, a smile that said, ‘it’s okay,’ a smile that reminded you that everything was going to be okay. your eyes flickered between his eyes and his lips, wanting nothing more than to feel them on yours once again.

“kiss me,” you breathed out. he leaned down to kiss you. his lips met yours softly as if he was scared that the relationship would crumble more with how delicate it already was. you wanted nothing more than to pick up the broken pieces and build something else with them, you wanted to fix everything.

you pulled away first, a smile forming on your face. you moved your hands up to play with the curls at the nape of his neck as he brushed some of your hair out of your face and behind your ear. he pulled you closer, finally wrapping his arm around you, and you melted into his touch, laying your forehead on his shoulder. you closed your eyes, finally feeling at peace. it was that moment, sitting alone with sam, when you realized the best years of your life were always spent with him. the bouquet turned out to be right, he was going to give you the best years.

-

anything and everything taglist: @hollanderfangirl @hxrryhxlland @ohmy-moonlightx @musicalkeys @notsosmexy @writertoo18 @icyhollands

#sam holland#sam holland x reader#sam holland x y/n#sam holland fluff#sam holland imagine#sam holland fic#sam holland x you#sam holland x reader fluff#sam holland x reader imagine#sam holland imagines

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Some major events that occurred on May 9.

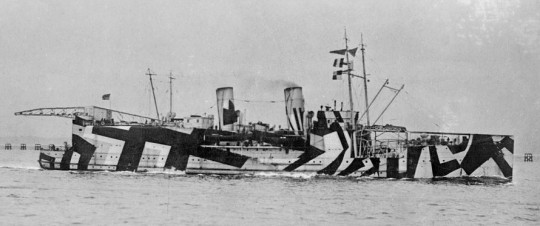

Photo One: The Second Battle of Artois begins, 1915.

Photo Two: The U-110 is captured by the Royal Navy. On board is the latest Enigma machine, which British will use to crack the code, 1941.

Photo Three: The Alfred Hitchcock classic Vertigo has its world premiere in San Francisco, 1958.

#this day in history series#history#second battle of artois#world war 1#world war ii#third reich#u-110#royal navy#enigma#alfred hitchock#old hollywood#vertigo

0 notes

Photo

Gif Request Meme - A Musical of my Choice + a Villain: Artois and Orléans

↳ Requested by @fallenidol-453

Philippe Égalité: The only legitimate son of the Duc d’Orléans, a prince du sang from birth, Philippe was a very unlikely revolutionary. And yet Philippe showed a strong level of compassion for the lives of the lower class, going down a coal shaft to see the conditions faced by miners, pulling a groom of his from a river with his own hands, and providing shelter for the poor during the bitter winter of 1788-89.

He was noted for his extravagant lifestyle; a noted lover of racehorses, gambling, architecture, his various and assorted mistresses, and all things English. Despite being the richest man in France, with a truly astronomical income, he nonetheless found himself frequently in debt. That was the impetus for him to totally redesign the Palais Royal over the course of two and a half years, opening it up to shopkeepers and establishing it as a major area for counter revolutionary activity, with the police being banned from intervening. As such, an overwhelming feeling of liberty prevailed there, with people from all social classes gathering to observe the spectacles and walk along the gardens there.

There was a certain amount of hostility to be expected between the two branches of the Bourbon family, going as far back as the first Duc’s tempestuous relationship with his brother, Louis XIV. Still, the relationship between Louis XVI and Philippe gradually deteriorated over time, despite several attempts to patch things up. Orléans blamed Louis for the loss of his naval career, with the controversial Battle of Ushant in 1778 being a major breaking point in their relationship. In 1788, he spoke up at a “Royal Sitting” where Louis tried to press the Parliament into obeying his will, saying “Sire, this appears to be illegal.” Louis responded, “It is legal, because I wish it to be so.” Orléans spent the next five months in a comfortable exile at his estate, and he returned more popular than ever.

When the Estates General was called, Orléans sided with the Third Estate, taking his place with the other delegates rather than sitting with the Royal Family as his rank entitled him to. His name was consistently brought up alongside revolutionary activity, with his bust being paraded alongside Necker’s on July 12, 1789, when the rash charge of the Prince de Lambesc into the Tuilleries heightened the people’s fears over an armed crackdown of Paris. It would be in the Palais Royal where Camille Desmoulins would jump on a table and call the people to arms, and even though the exact impact of that statement’s been disputed, the fact that Palais Royal was a huge locus point for revolutionary activity never has been.

Among the royalists, it was popularly thought that Orléans was behind the entire Revolution, masterminding the Storming of the Bastille, the Women’s March to Versailles, a famine, and various and assorted other disturbances, in lieu of believing that the common people themselves were discontent. However, the sources nearest and dearest to Philippe suggest that he had no intention of seizing power, and Philippe’s own action of going and staying in England at Lafayette’s suggestion between October 1789 and July 1790, when he had a strong chance of fighting back against the charges and seizing power for himself by riding off the highest point of his popularity, strongly indicates that he had no intention of seizing the throne for himself. Overall, while he was a man of undeniable courage, the popular consensus is that he was, by nature, too passive to do it on his own, generally being very diffident to those near him such as his former mistress and longtime friend, Madame de Genlis, as well as her rival for his attention, Pierre Ambroise François Choderlos de Laclos, and generally disinterested in long-form plans, preferring to throw himself into whims. It is far more likely that, if a plan existed to make Philippe king, it came from one of those brains, as opposed to anything Philippe himself considered in any detail.

He did, however, become embittered over the increasingly chilly reception he received at Versailles, including one occasion where a courtier shouted “Do not let him touch the wine!” when he entered, with him then being spat on as he made his leave.

In the latter half of 1792, Philippe faced a bevy of problems, both personal and political, as his long-suffering wife had filed for a separation, his daughter was put on a list of émigrés and was forced to leave the country very shortly after arriving (after Madame de Genlis, who he had instructed to take her back before her name could be added, lingered for too long, causing a final breakdown in their long relationship), his popularity was rapidly fading, and he had been called, as a Deputy of the National Convention, to sit at the trial of his cousin. According to one anecdote, found in William Cooke Taylor’s Memoirs of the House of Orléans, it was in that particular maelstrom that he changed his name, as a last ditch effort to save his daughter and prove his loyalty to the Revolution, to Philippe Égalité. Many options were considered for him to not sit the trial, and there is no reason to believe, despite the long-lasting enmity that the two of them had, that Philippe, when he went to sleep the night before the trial of Louis began on December 26, that he had any idea that when it came time to give the verdict on January 14-15, he would vote “yea,” a decision that shocked the entire room, not the least Louis himself. Perhaps it was a last ditch effort to save himself, perhaps he felt pressured to do it by everyone else in the room, perhaps in that moment he truly believed that Louis’ actions merited the death penalty. It’s impossible to truly know, but in the end that one decision, more than anything else, has defined his legacy.

However, the Royalists would soon be able to find some comfort, as, on the 4th of April 1793, his son, Louis-Philippe, Duc de Chartres, defected along with General Dumouriez, and Philippe’s enemies had the ammunition they needed.

On 7 April, 1793, he was arrested and sent to Fort Saint-Jean in Marseilles, along with two of his sons. Throughout his imprisonment, Philippe kept up an optimistic front, constantly reassuring his sons, the Duc de Montpensier and the Comte de Beaujolais, on the rare occasions he was allowed to speak to them after they were separated, that everything would turn out well, even expressing optimism about his trial in Paris. Whether this was real or simply an attempt at keeping up morale will never be known, but on November 2, 1793, he was sent back to Paris, to be imprisoned in the Conciergerie. He was tried on the 6th and, at his own request not to prolong things any longer than necessary, he was executed on that same day. By all accounts, he met his death courageously, his composure only threatening to break when the cart he was in stopped in front of the Palais Royal, so that he could very clearly see the sign on it that said it was now national property. His last words were to stop the assistants at the guillotine from taking off his boots, saying “You are losing time, you can take them off at a greater leisure when I am dead.”

Unlike his royal cousins, his body was never found, and to this day, he is generally considered as one of the great villains of the Revolution in media associated with it, though none of the serious charges against him (the October Days being prime) were ever proven.

Charles X- For most of his younger years, like his older cousin, Charles’ defining quality was his wild life, which was punctuated by multiple love affairs, copious gambling and alcohol, and even more copious debts, with his brother, Louis XVI, somewhat reluctantly paying the bills. He also had a close friendship with his brother’s wife, who he shared a love of high living with, the two of them often being seen together at the theatre and balls. This close friendship was much remarked upon, with Artois being a frequent subject of the pornographic pamphlets that circulated about the queen, along with Marie Antoinette’s favorite, Madame de Polignac. In the years preceding and following the Revolution, however, the two of them gradually cooled, with their later relationship being marked by political disagreements. Charles consistently pressured his brother into more conservative stances during the meeting of the Estates General, arguing against doubling the Third Estates’ representation and conspiring to get rid of Louis’ liberal finance minister, Jacques Necker. The dismissal of the Necker would end up being one of the leading causes for the Storming of the Bastille, with Charles’ temporary personal victory being quickly eclipsed by the blaze that the little spark of Revolution had turned into. In the days immediately following the Storming of the Bastille, Artois was ordered to emigrate by his brother, along with the rest of his family.

He wouldn’t see France again for decades, going from court to court in Europe asking for help and trailed by a small army of creditors (who would become some of his most frequent companions, the avid huntsman only being able to go out riding at his estate at Holyrood on Sundays, when his creditors would be unable to pursue him), but with very little materializing, even less of which was successful, with the Battle of Quiberon being particularly disastrous to any hope of a royalist win by military might. Instead, he set up his main residence in London, with his mistress, Louise de Polastron, sister-in-law of Madame de Polignac, upon whose death he swore a vow of celibacy, the former playboy becoming sober and religious in his later years. The family briefly returned to France in May 1814, with the exile of Napoleon to Elba, however his later escape and mustering of the troops led to them leaving the city in February 1815, only able to fully establish themselves back in the country shortly after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo. Upon his brother, the Comte de Provence’s ascension to the throne as Louis XVIII (the space between XVI and XVIII being taken up by Charles’ young nephew, Louis-Charles, who died in prison and therefore never ruled), Charles became known as a leading member of the Ultra Royalist faction, who were, as the name suggests, “More Royalist than the king.” His brother dying without a male heir, Charles took the throne in 1824, though his highly conservative policies following his more tolerant brother’s reign made him highly unpopular with the public.

In 1830, he was forced to abdicate. His intent had been for the throne to go to his young grandson, however, it would go to Louis-Philippe, Duc d’Orléans, the son of Philippe Égalite (who would himself end up being deposed.) He spent the remainder of his life similarly to how he spent his exile, traveling from place to place, hounded by debtors.

Eventually, he would die in Austria, on 6 November 1836, 43 years to the day of his revolutionary cousin’s execution.

Sources:

The Chevalier de Saint-Georges: Virtuoso of the Sword and the Bow: Gabriel Banat

A French King at Holyrood: Alexander John Mackenzie Stuart

The Journalists and the July Revolution in France: The Role of the Political Press in the Overthrow of the Bourbon Restoration 1827–1830: Daniel Rader

Memoirs of the House of Orléans: William Cooke Taylor

The Perilous Crown: France Between Revolutions, 1814-1848: Munro Price

Prince of the blood : being an account of the illustrious birth, the strange life and the horrible death of Louis-Philippe Joseph, fifth duke of Orleans, better remembered as Philippe Egalite: Evart Seelye Scudder

Revolutions in the Western World 1775–1825: Jeremy Black, ed.

#perioddramaedit#asiantheatrenet#musicaltheatreedit#historyedit#1789 les amants de la bastille#marie antoinette das musical#keigo yoshino#mitsuo yoshihara#long post#ch: artois#Production: Toho#other musicals: MA#historical#on this day in history we mourn the death of two thots#one more than the other#(apologies if I smudged any facts given that it is rather late)

65 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Foudroyant and Pégase entering Portsmouth Harbour, 1782 by Dominic Serres, 1784

The Third Battle of Ushant,20–21 April 1782, was a naval battle fought during the American Revolutionary War, between a French fleet of three ships of the line protecting a convoy and two British ships of the line off Ushant, a French island at the mouth of the English Channel off the north-westernmost point of France. This was the third battle that occurred in this region during the course of the war.

The French tried to supply 19 transporters together with the 64-gun Actionnaire and the 74-gun Protecteur and Pégase and the frigates Indiscrète and Andromaque to the fleet of Admiral Bali de Suffren in his campaign for the reconquest of French property. However, they were sighted by the frigate HMS Artois and the HMS Foudroyant a third rate, ship of the line was sent after them. Despite bad weather, she managed to conquer the pégases. But the weather continued and so the Foudroyant had to ask for help. This help came in the form of the HMS Queen a second rate, ship of the line with 90- guns, who even managed to conquer the Actionnaire the next day. Shortly afterwards the possibility arose to hunt the protector Frederick Maitland, Captain of the Queen decided against it and instead hunted the transporters. Together with the frigate HMS Prudente they managed to conquer 12 of them. Not only that this battle cost 160 men their lives and about 2000 were captured. It also dealt Admiral Bali de Suffren a huge blow.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

The new years on the Western Front

German bunker at Dodengang near Diksmuide Belgium, December 2018

By January 1 1915, the hopes that the war would end quickly had dissolved into the mud of Belgium and France. The First Battle of Ypres in Belgium had ended the month before, and with it the tactics of open warfare for the next four years. Armies now faced each other for 450 miles across Western Europe, from the English Channel, across Belgium and northern France, all the way to the Swiss border. The Germans had fully moved to the defensive, reinforcing their trenches, building concrete bunkers up and down the line, and clearing positions for deadly machine gun and artillery fire. The Allies dug in as well, but had already begun making plans to attack in 1915 in the desire to evict the Germans from Belgian and French territory. The Allies built few bunkers and did not improve their trenches. Why bother, the Allied commanders thought, when they would be moving to the German positions soon enough? They would find this much easier said than done, and would experience heavy losses during the campaigns in the French Artois, at Loos and in the Champagne.

The hope for a breakout on the Eastern Front at Gallipoli, and for the USA to join the war after the sinking of the Lusitania, would both prove to be disappointing to the Allies. April of 1915 would see the first use of chlorine gas at St. Julien Belgium, with appalling results. Shockingly long casualty lists, British munition shortages, and with no end in sight, the 1915 year of the Great War came to a close.

Monument Le Mort Homme near Verdun France, December 2018

1916 would make the previous year of the war look tame in comparison. On February 21 the Germans launched Unternehmen Gericht (Operation Judgement) and attacked the French at Verdun. With a stated desire to “bleed France white”, German commander Erich von Falkenhayn looked to break both the strength of the French army and the will of the French citizenry to continue with the war. He was nearly successful. Instead, under General Philippe Petain, the French would rally to the defense of Verdun. The battle would cost Von Falkenhayn his job in addition to nearly one million German and French casualties, distributed more or less equally between the two armies. The German and French armies would each have successful offensives in the later years of the war, but the Battle of Verdun was a high water mark for both forces in terms of strength and morale.

Front Line July 1 1916, La Boisselle France, December 2018

On July 1 1916, British forces at the front along the Somme River in France, climbed over the top of their trenches and launched an attack. Wave after wave of young men walked across No-Man’s-Land into withering German artillery and machine gun fire. The bloodiest day in the history of the British Army saw nearly 20,000 soldiers killed, most within the first hour of the attack. By November Britain had suffered half a million casualties. The trauma of The Somme still resonates today throughout the United Kingdom, as well as Australia, Canada, India, and New Zealand. Not to be outdone, the French would suffer 200,000 casualties. The Germans took half a millions casualties of their own at the Somme.

Canadian National Vimy Memorial, near Givenchy-en-Gohelle France, April 2018

The slaughter of 1916 would continue into 1917. This year of the war saw dramatic events such as the Russian Revolution and their near total withdrawal from the war, as well as the United States declaring war on Germany. French Commander-in-Chief Joseph Joffre had been replaced by Robert Nivelle by the first of the year. On April 16 Nivelle launched an offensive of his own along the front in Northern France. German forces had already retreated to the fortifications of the Seigfriedstellung (Seigfried Line, or commonly known as the Hindenburg Line) and Nivelle’s offensive was a disaster. The French suffered nearly 200,000 casualties and gained practically nothing. In frustration at the meaningless loss of life, French troops began to mutiny. In May numerous French divisions flatly refused to fight. Nivelle was sacked and replaced by the hero of Verdun, Philippe Petain. “I am waiting for the tanks and the Americans” Petain stated. There would be no more pointless French attacks.

Tyne Cot British Cemetery and Memorial, near Passendale Belgium, April 2018

While Petain worked to end the mutinies, bring his soldiers back under control and rebuild French army morale, the British sought to keep the Germans distracted in Belgium. On June 7 1916 British Commander-in-Chief Douglas Haig launched the Battle of Messines. While deemed a strategic success for the British, both armies would each suffer 25,000 casualties at Messines. The next month Haig launched the Battle of Passchendaele (Third Battle of Ypres). A heavy bombardment that turned the landscape into a muddy soup, as well as constant rain, created conditions that were truly a hell on Earth. Soldiers that fell into the mud would slowly be sucked under to drown. Any attempt to help a trapped comrade would result in additional soldiers being sucked into the mire. Despite the atrocious conditions, repeated attacks were ordered, but almost no significant ground was gained by British forces. Final casualty counts are disputed, but by November anywhere between half a million and one million soldiers were killed, wounded or missing, with the numbers again being almost equally split between the British and German armies.

1918 would see the final year of the Great War, but it would prove to be just as horrific as the previous years. With Russia out of the war, the German Empire could focus their army on the Western Front. They had no time to lose as thousands of American soldiers were pouring into France each day. On March 21 the Germans launched the Kaiserschlacht offensive and broke through Allied lines in Belgium and France. Within a week they had attacked to a depth of 40 miles and by May German forces were back on the Marne and threatening Paris just as they had done in 1914. Philippe Petain’s defensive strategy stopped the German advance in July and, having advanced past their own ability to supply their forces, the Germans had to fall back. The Kaiserschlacht was over and Germany had suffered nearly 700,000 casualties.

Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial, Romagne-Sous-Montfaucon France, December 2018

On August 8 1918 the Allies, now under the unified command of French Field Marshall Ferdinand Foch, began the Hundred Days Offensive with the Battle of Amiens in France. German General Erich Ludendorff would later refer to this day as the as the Schwarzer Tag des Deutschen Heeres (Black Day of the German Army). Morale had crumbled among German troops and they were surrendering in massive numbers. The Germans suffered 30,000 casualties on that day alone. German soldiers called reserve troops moving up for battle “strike breakers”. German commanders, trying to rally their retreating troops, were told “You’re prolonging the war!” In September German allies were dropping out of the conflict. Bulgarian, Turkish, and Austria-Hungarian armies stopped fighting. With Americans now on the battle lines, the Allies were out of their trenches and fighting the Germans in open country. Each day more German soldiers would surrender and the Allies would gain more ground. October riots within Germany convinced the high command that no more was possible. The possibility of winning the war was gone and on November 6 a delegation set out from Berlin to negotiate with Ferdinand Foch and the Allies at Compiegne France. The Armistice took effect five days later.

Foch Monument at the Glade of the Armistice, near Compiegne France, April 2018

January 1 1919 saw the first New Year’s Day on the Western Front without battle in four years. But the war was not officially over. The Paris Peace Conference opened on January 18. It was not lost on the Germans that this date was the anniversary of the establishment of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701 as well as the establishment of the German Empire in 1871. The “Big Four” major powers of France, Britain, Italy, and the United States dominated the conference and worked together to unilaterally draft the Treaty of Versailles. In addition to the loss of colonial territories, the reduction of its military force, the levy of reparations and new national borders, the treaty placed the full blame for the war on the “aggression of Germany”. While US President Woodrow Wilson and the American delegation did not believe it was fair to lay the blame for the war solely on the German Empire, they were unsuccessful in getting the language of the treaty changed. The treaty was signed by representatives of Germany, France, Britain, the United States, Italy and Japan on June 28 1919, precisely five years to the day after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The Great War was now officially over.

The 1918 “Alsace-Lorraine” Monument depicting a German eagle impaled by a sword, near Compiegne France, April 2018

German popular resentment of the Treaty of Versailles, the humiliation of their defeat, costly reparations, the embittered memoirs of Ludendorff and other German military commanders, along with economic depression, and political instability, are all considered to have contributed to the resulting Nazi political success that began in 1925. Some believed, like economist and British delegate to the Paris Peace Conference John Maynard Keynes, that the conditions of the treaty were far too harsh and would end up being counter-productive to peace and the word economy. French Field Marshall Foch felt the opposite. Foch believed the treaty to be far too lenient on Germany. At the signing of the treaty he declared “This is not a peace. It is an armistice for twenty years.”

The Second World War began on September 1 1939 with the German invasion of Poland, twenty years and 65 days after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles.

Postscript: This is probably the last of the big text posts. From this point on I will be sharing the sites of the Western Front as they are today, 100 years after the end of the Great War. I have seen some pretty amazing things around Belgium and France and I look forward to sharing the images of these sites with you.

Additionally, if you are interested in a great book about the Paris Peace Conference I would highly recommend Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World by Margaret MacMillan.

January 4, 2019

#ww1#worldwar1#westernfront#greatwar#treatyofversailles#ludendorff#foch#Petain#DouglasHaig#Passchendaele#somme#verdun#Kaiserschlacht

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

It Seems Like Nothing Changes

Paul Cussen

August 2018

In the last two weeks of Anglo-Welsh composer Philip Heseltine’s year long stay in Ireland, he writes ten songs which are published under the pseudonym Peter Warlock. These are considered to be among his finest work.

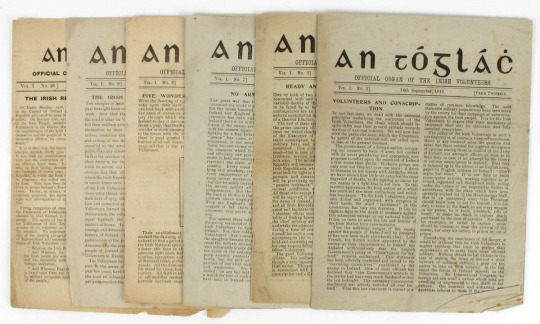

An t-Óglách, with the tagline ‘The Official Organ of the Irish Volunteer', often described as a successor to the Irish Volunteer, is published. It is published twice a month initially and successfully manages to remain in circulation despite numerous raids and having to operate in secret to avoid complete closure. Michael Collins, Adjutant General and Director of Organisation, is a regular contributor to the magazine.

Charlie Hurley is arrested on a charge of unlawful assembly and imprisoned in Cork Gaol. When arrested he is found to have in his possession documents relating to military installations in the Beara peninsula and a plan for destroying the police barracks in Castletownbere. On release from Cork Gaol he is rearrested, court-martialled and sentenced to five years' penal servitude at Maryborough (Portlaoise) Gaol.

John Hawkes from off-Barrack Street lodges an unsuccessful appeal with the local War Pensions Committee in Cork city, noting that he had been ‘awarded a pension of 8d. a day for 18 months final [sic] & his period expired some time ago. He states that if he could obtain a pair of spectacles, he would be employed at once as a watchmaker. He has no home and no money and will have to go to the workhouse if his appeal fails.’ Hawkes had previously served in the Royal Munster Fusiliers in France but had been discharged in April 1915, according to his mother, ‘because he got a bad cold in the trenches’ and had been declared ‘unfit for further duty’. Doctors at a hospital in Boulogne had determined that Hawkes suffered from a ‘mental deficiency’ .

Acting Major Thomas Marshal Llewellyn Fuge is mentioned in Despatches. He is mentioned in ‘Long Shadows by de Banks: the history of Cork County Cricket Club’ by Colm Murphy as a useful fast medium bowler who played for Ireland.

Stephen O’Callaghan of 39 Bandon Road completes four years on active duty with the Worcestershire Regiment and the Royal Munster Fusiliers, a recipient of the British Army Service Medal and the Victory Medal.

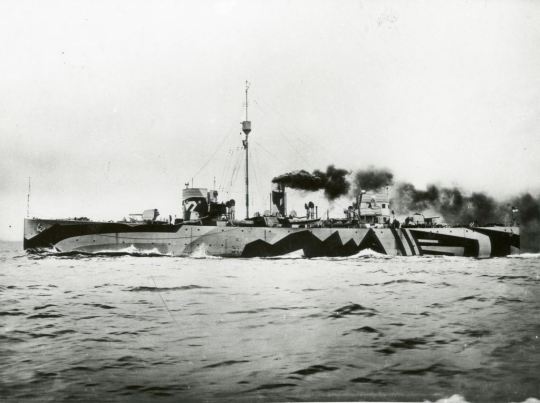

HMS Flying Fox takes over kite balloons and the operations are attached to the deployment of the American battleships Utah, Nevada and Oklahoma. The three battleships operate from Berehaven from August to October to protect Allied convoys from attack by the German battlecruisers.

August 1 – The first fully combined air, sea, and land military operation in history is launched as RN Fairey Campania seaplanes from HMS Nairana join Allied forces to drive Red Army forces from the mouth of the Northern Dvina river in Russia.

The French Tenth Army launch an attack and penetrate five miles into German territory in the Second Battle of the Marne.

British troops enter Vladivostok.

August 2 – Captain Georgi Chaplin stages a coup against the local Soviet government of Arkhangelsk.

Japan announces that it is deploying troops to Siberia.

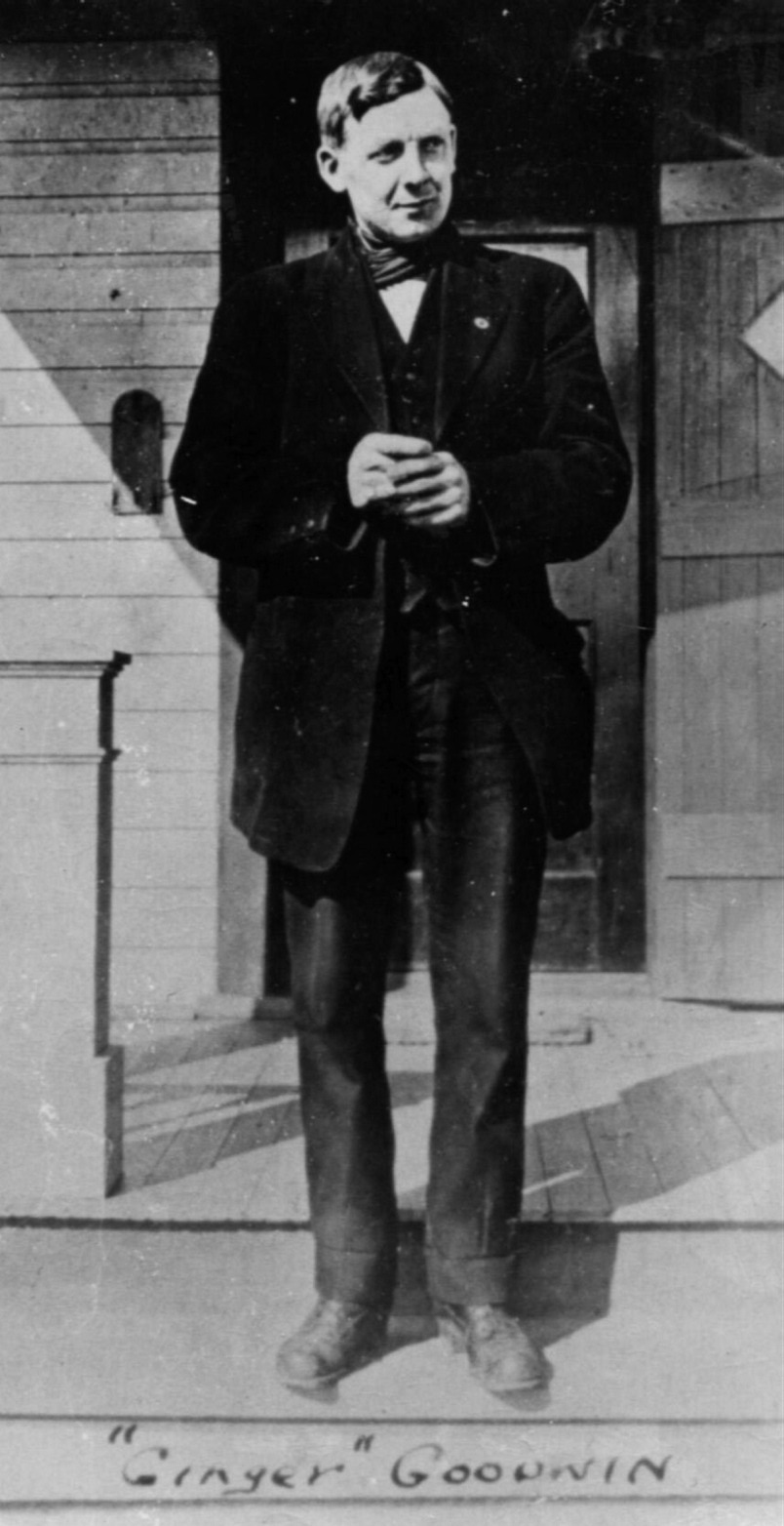

The first general strike in Canada occurs in a one-day protest at the murder of Albert “Ginger” Goodwin.

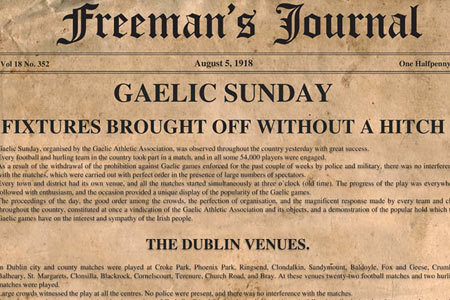

August 4 – ‘Gaelic Sunday’, approximately 100,000 Gaels take part in an act of defiance against the British administration by refusing to apply for licenses to play Gaelic Games.

Noel Willman, actor and theatre director, is born in Derry.

There is a full muster of the members of the companies of the Third West Cork Brigade for the funeral of Lieutenant William Hurley (Kilbrittain Company) in Clogagh.

The Norwegian barque Remonstrant is sunk in the Atlantic Ocean 280 nautical miles (520 km) west of the Fastnet Rock. Her crew survive.

Adolf Hitler is awarded an Iron Cross first class on recommendation of his Jewish superior Lieutenant Hugo Gutmann.

August 5 – Five Zeppelins attempt to bomb London however most of the bombs fall into the North Sea due to heavy cloud cover and L20 is shot down killing all the crew.

August 7 – Florrie Burke is born. He goes on to play for Cork United, Cork Athletic, Evergreen United, Ireland and the League of Ireland XI (d. 1995).

August 8 – The first organised meeting of the I.T.G.W.U. in Mallow is held this evening in the old Town-Hall.

Battle of Amiens where Canadian and Australian troops begin a string of almost continuous victories, the 'Hundred Days Offensive', with an 8-mile push through the German front lines, the Canadians and Australians capture 12,000 German soldiers, while the British take 13,000 and the French capture another 3,000 prisoners (more enemy troops were captured in the six days from August 6 to August 12 than in the previous nine months combined). German General Erich Ludendorff later calls this the "black day of the German Army". Historian Charles Messenger refers to this date as the “day we won the war”.

August 10 – General Frederick Poole, the British commander in Archangel, is told to help the White Russians.

August 16 – Battle of Lake Baikal is fought by the Czechoslovak legion against the Red Army. Red army forces take Arkhangelsk.

August 17 – Moisei Uritsky, the Petrograd head of the Cheka, is assassinated.

Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon meet for the last time, in London, and spend what Sassoon later describes as "the whole of a hot cloudless afternoon together”. British troops attack Baku, Azerbaijan

August 21 – The Second Battle of the Somme begins. Corporal Thomas Hargroves, Royal Irish Regiment, 2nd Batallion, dies in action. He had come from Laois to serve in the Prison Service in Cork and enlisted for military service in early 1916. He first saw action securing positions in Dublin in 1916. His unit landed in France in August 1916. He is listed on the Vis-En-Artois Memorial, (and on a memorial which disappeared from St. Peter’s Church between 2002 and 2006).

August 22 – Sergeant John Hallinon is killed in action in the Somme. He was born around 1883 in Ballincollig and was working as a bank messenger in London. His wife, Emily, unaware of the condition of life in the trenches wrote to ask for her husband's ring, wristwatch and pipes. They had one child, William.

August 23 – Creation of the Bessarabian Peasants' Party.

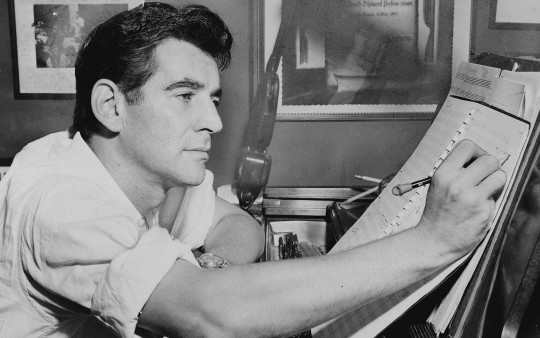

August 25 – Composer, conductor, author, music lecturer, and pianist Leonard Bernstein is born in Lawrence, Massachusetts (d. 1990).

70 year old fisherman William Whelton dies in Courtmacsharry after mistakenly consuming poison (unlike poisonings in the UK a century later there is no suspicion of Russian involvement!)

August 27 – Denis O'Doherty, Irish Guards is killed in action aged 28. His brother Felix O'Doherty had started the Fianna and Volunteers in Blarney and became Captain 'B' (Blarney) Company, 6th Battalion, Cork Brigade, I.R.A.

The Battle of Ambos Nogales occurs when U.S. Army forces skirmish against Mexican Carrancistas and two supposed German advisors at Nogales, Arizona, in the only battle of WWI fought on United States soil. Over 130 people die, the majority are Mexican citizens.

August 29 – Science historian and cryptanalyst John Herival is born in Belfast (d. 2011).

Bob Conklin dies of gunshot wounds, sustained at the Battle of Arras. Due to the delay of mail from the Front, his family still continue to receive letters from Bob after learning of his death: “Give my love to all and don’t worry on my account”; “Well, my news is finished, so I’ll ring off. I will write mother in a few days. Love to all. Bob.”

August 30 – Czechoslovakia forms independent republic.

London Policemen go on strike after the dismissal of PC Tommy Thiel (centre in the photograph) for union membership. The strikers demand union recognition and a wage increase. Within a few hours 6,000 men throughout London are out, with more joining all the time; even the Special Branch is affected.

Vladimir Lenin is shot and wounded by Fanny Kaplan in Moscow.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part 6: Various Names

These are all bullet-pointed, and the first part will be translated in Kaga’s own voice, since that’s how they’re written.

I also decided to include my own notes on the origin of various names. This post is also crazy long, and mostly just exists so I can keep all my ideas and facts straight.

Berwick Saga

The “Bren” (ブレン) of Brenthunder (ブレンサンダー) and the Bren Crossbow (ブレンクロスボウ) is from the famous English Bren Light Machine Gun. Military enthusiasts probably immediately recognized this.

Gorzevalus (ゴーゼワロス) was named by the designer who wrote that map’s scenario. I don’t know where he got the name, but he’s a very serious person, so I doubt he intended it to be funny.

A derrick (デリック) is a type of large crane. Since they can be used to lift heavy items as well as help survey undersea wrecks, I wanted Professor Almuth’s first name to give the impression of historical site exploration.

Things like Critical Knife and Wallenstein were simply abbreviated (クリティカルナイフ > クリテカルナイフ, and ヴァレンシュタイン > ワレンスタイン) due to a 7-character limit we had early in development. I must’ve simply missed them when I double-checked later. Similarly, we abbreviated Composite Bow (コンポジットボウ > コンジットボウ).

[Note: this won’t apply to the translation patch, since there’s no character limit.]

Sherpa (シェルパ) are a tribe of mountain guides at the base of Mt. Everest. I chose the name to parallel “Highlanders.” As for Highlanders (ハイランダー), they’re a historical ethnic group from Scotland who were renowned as brave warriors in history. I’ve been told that the Sherpa’s appearance closely resembles the hero of a certain manga, but I’ve never read it, so it’s just a coincidence.

I chose the name Kramer (クレイマー) because it’s close to “climber,” since he’s got a natural gift for climbing cliffs as a skill. I’m on the fence whether it should be to be a nickname or not... I guess it’s probably a nickname he picked himself.

Sapphire (サフィア) and Ruby (ルヴィ) are named after the precious stones, naturally.

Names like Roswick (ロズオーク), Vanmilion (バンミリオン), Shirrock (̪シロック), Quescria (クエスクリア), and the like I just made up. I didn’t take them from anywhere in particular.

[Note: in the patch, “Shirrock” will be Sherlock, which is a real name.]

Faramir (ファラミア) and Olwen (オルウェン) are from The Lord of the Rings.

[Note: I’m not sure which LotR character Olwen is supposed to be. The closest one it matches is Arwen (アルウェン), but that’s a woman...]

Faramir’s class name Wanderer (渡り戦士) is borrowed from a certain manga. Sorry, Ms. Hikawa!

Sylvis (シルウィス), Larentia (ラレンティア), Pfeizal (ファイ���ル), etc. are mythological/historical people; I also sometimes used the names of mythological weapons for people, too.

Most other proper names are original or just common names, like Lynette, Reese, Bernard, etc.

TearRing Saga

It’s hardly worth mentioning, but Katri (カトリ) is just a plain ranch girl’s name. Back in the day, a lot of people thought it had something to do with baseball pitching. It’s from an old anime based on a very old children’s story from Finland, so it’s natural people wouldn’t recognize where it came from.

[Note: I have no clue what Kaga means about the baseball thing.]

Ente (エンテ) is German for “duck,” while Möwe (メーヴェ) means “seagull.” In other words, it’s an play on words where if you add eyes (メ) to a duck (カモ), you get a seagull (カモメ), meant to parallel that when Ente awakens to her true self, she becomes Möwe. Naturally, there’s also the added meaning that she wants to fly in the skies freely like a seagull, not be a duck that hides itself underwater.