#Kaiserschlacht

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

German stormtrooper with a gas mask M1917 holding a stick hand grenade in the Spring offensive/"'Kaiserschlacht" ,1918.

#wwi#stormtrooper#German#troops#gas mask#in the trenches#ww1#1910s#world war 1#first world war#the great war#world war i#world war one#trench#war history#photography#photo#world war#tumbler#tumblr#post#great war#Germany#picture#western front#Europe#german army#military#1918#history

232 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any fic about the difference between how Matt is to Alfred vs Jack/Zee? That feels untapped.

Four cunts and a Kiwi walk into a trench.... Please note this is a work of historical fiction based roughly on the Kaiserschlacht of 1918, Germany's last offensive. It is not a textbook. The interactions here cannot possibly begin to represent the real motions of history. The depictions of war and empire are fictional. Everyone's a piece of shit in this, but they are fictional pieces of shit. The existing author's views do not align with that of the fictional characters or any other message you think you're gleaning from this. Everyone in the following piece is fictional and over the age of 18. Do not get your morality from fanfic. No one is happy, no one is having a good time. They are individual, fictional characters and they are miserable. If I haven't made them miserable enough its because my wrist is busted in two places and I'm not in the fucking mood. Flanders March 1918

Matt’s slicker is draped over the tent pegs, a crude shelter against the elements beating down on them. Between Matt shoved in tightly to his left and Zee wedged into his right, and the blankets still tucked in tight all around them, Jack is as warm as he’s been since he stepped foot on this bloody continent. He shifts, something uncomfortable against his back.

He mumbles something and tells Matt to roll over, but Zee says something about Matt fucking off if he was going to be an insomniac. But Zee is to his right, and Jack is on his back. She can’t possibly feel anything. He disregards it, rolls back asleep, and snuggles in tighter against her back.

There’s a rush of cold air, Matt yelling at him to get up! To get the fuck up! There’s the crack of steel on a skull. He knows the sound has driven his own shovel into enough Turkish and German heads by now to know it, as well as he knows the sound of his own voice. Matt’s grunting gets louder. Jack is on his feet, pulling Zee up with him. He may as well have not opened his eyes. It’s so fucking dark.

He snatches Zee close, and she screams at him, working something over in her hands.

“Get down,” He hisses at her.

He’s too late. She’s lit the flare. In the dark, formless under the clothes and blankets, she might have not been noticed, but in the sick light of the flare, green as gas, there’s no mistaking her form, a girl’s form even in the trousers of the men’s field uniform, permitted this near the front with the medical officers. They were supposed to be safe here, three trenches back. There’s a joyful German noise and then the swell of bodies. Not a trench raid, not a squad. This is a counter-offensive. Matt throws one into another’s bayonet, and Jack breaks another German’s neck without thinking. The world is lit in green light reflecting from the gore.

He kills three men in seconds, Matt even more. But they’re replaced. This is no trench raid. It is a punch right through the line, a blow puncturing right through the armour of the front line. Jack takes up one of the rifles, but it won’t fire. He swings it into another man’s face. Where the fuck is his gun? Where the fuck is Matt’s?

“Zee! Go!” Matt bellows. Jack spun and watched his sister’s face. There’s German blood there, splattered across her jaw and cheeks, her hand red, a knife that is not hers dripping.

“Go!” Jack says and bodily shoves her back at the ladder. “Find Dad!”

Her eyes flash with the knowledge that this is the only way to avoid the worst, but also full of loathing. She hates him, and maybe Matt, for making her go.

“Go with her,” Matt tells him. Gripping him by the sleeve and shoving him as hard as he can. “Go!”

“Matt!”

“Go!”

He’s got a German rifle to his shoulder and is already flipping back the lever and aiming. He looked up, and he was horrific in this light, face sharp, eyes narrow, lip curled back. But a flash of Matt, of peacetime. “I can slip away if they capture me. You can’t! Go!”

“He’s right!” Zee whispered. “Come on!”

“No!” Jack wrenched his arm free of Matt. They’re surrounded by his soldiers. Australians are to their left and their right flanks, awake now and fighting. Their souls come to his awareness like stars as the sun sets. Pinpricks of light he can’t leave. Too much is happening. “No! Stop!”

“Jack, Go!” Matt’s firing, and something is screaming in the distance. Five bullets, then four. “I’m right behind you.” Four bullets left, more screaming. The trenches around them are coming alive. He won’t leave them. He can’t.

But Zee’s got him by the arm and is dragging him with her.

“You know what happens if we stay!” Zee whispered. Three bullets become two. Hoarse shouts. She gripped him by the face, her own grey with terror, but her brown eyes set with certainty. She has all of Dad’s decisiveness. “What happens if I stay,”

And just like that, she’s straightened his thoughts. He won’t let Germans have her, and she won’t leave him here. So they go. They have to go.

“Okay,” He exhales his panic and shakes his entire body. “Okay.”

Matt has fired twice more. He’s out of bullets, and more are coming, more are coming now. His sister tugged him back. He snatched up his sidearm, forgotten on the floor in the mêlée.

“Be quick and be safe!” Matt tells them. It’s a benediction as hoarse as his prayers are when he thinks there is no one around to hear him. They’re just as futile, too. The time their slaughter brought them is at a standstill, and Matthew’s bullets are gone.

“Find Alfred!” Matt screams over his shoulder as if he’s on another German. The last thing Jack sees of him is the full horrific brutality of his Matt in hand to hand. The filth of his fight. Matt was a brutal bastard. He thrust his fingers into an enemy’s face, finding eyeballs for leverage and twisting heads, viscous as a wolf just before spring. Matthew gives Germans a fight the way he gave their father before Jack was born, and that’s before his fingers close around the pine of his favourite axe. Jack turns, hearing Zee say his name. Their artillery is waking now. He can hear the guns open up. They have to go.

Zee was just ahead of him, running headlong into the dark. It’s wrong. Leaving his men. But she’s ahead of him. It’s the way the world works. Zee sailed into a new day ahead of him on their spinning planet. He follows. A German must have crawled past Matt. Jack shoots.

Zee jumped, startled, and for a fucking moment, he thought his wee Kiwi-bird of a sister, flightless and round, was going to sprout wings and fly straight home to New Zealand. But she’s repeating his name, and he’s staring into the dark, eyes swimming with the gun flash, wondering if hell is a different sort of red from home, with all its bright baked clay. Zee took his hand, her bloodied fingers around his, and looked at him. He grabbed her and hauled her along, forcing her to keep up with him despite their height, as he has their entire lives, from the moment she toddled into existence and he was taller.

He can trace her in the dark as she zigzags through the bullets and is lit by the odd shell in the sky as they escape into the night. He never lets go of her, making her steps longer when her weight hasn’t completely shifted. She is not alone. He is not alone.

They slip into the night, into chaos, into darkness, and further back into the line. Jack trips when a floodlight opens on them, temporarily blind as Zee hauls him to his feet. Everywhere, everything is chaos. Horns honking on trucks they only see when their lanterns appear from nowhere upon soldiers firing up the ignitions, officers and enlisted men shouting. American rifles being broken out from their boxes, sleeping soldiers on rest, still dreaming as they take distributed weapons. The trenches give way to tents, and tents give way to the depots. Still, Zee pulls him along.

“Where—” Jack asked, panting. “Where the fuck are we going, Zee?”

“Alfred!” She huffed, breathless, like that was obvious. But he had wanted father first and figured she would, too.

“Why?”

“Father will prioritize defending the front line.”

“So?”

“So— Alfred understands defense in depth. Give up the first line easily, then they pay for driving in deep, using the salients for killing zones. The more warning he has, the more of his and ours that man those salients, the more of theirs will die.”

He swallowed. He hated it when she sounded like Dad.

“Like Ypres before Matt took the high ground. Guns on three sides,”

“Exactly,” Zee replied. She had picked up a lantern at some point, and as she raised it, her eyes, always more brown than green, glinted for a moment with father’s thrilled, satisfied cunning. “We make them pay.”

They stumble through the night, guided by the sensations of a nation so like and unlike them. They are flavours of the night jars that encircle the Pacific. They fly; they’re so much larger than their father. Matt, cold and clinging to the top of the world, his back against Alfred, with even more people. Then, Jack was warm and all alone in the Pacific in his early years. But the Tasman Sea is Zee’s hand on his elbow. He loves her so much, and he hates his father, and he hates Matt for making them go and both of them for being right and for being practical. He collapsed into the early morning grass off the road, nearly taking Zee down with him. Soldiers yelled, and more traffic roared in his ears.

“Jack?” Zee tugged him to a stop. “Jack, mate. Hey.”

He couldn’t quite seem to get his breath, and he barely avoided puking all over her as he sprawled to the side and vomited what felt like everything he’d ever eaten since stepping foot in France.

Zee made a sympathetic sort of sound, and he felt her arms around her. It’s his soldiers behind them now. He can feel hers a little, too, on the flanks and Father’s, but his own are fighting, and he is running, and he has killed again. Again. And not for the last time. What’s his count? Can he add those to his count? Matt does. Zee counts hers against the lives she saved, and now she cradles his head, gently taking him by the jaw to make him look at her. Her eyes are hers now, and it’s not her father’s words in her mouth, not his will or his brutal practicality.

“Jack,” she said, and he squeezed her, clamping his arms around her smaller body like he had when he was little, and she was all he had of home in frigid England. “Jack, Christ.”

“I’m sorry,” He said but didn’t let go. She squirmed, not escaping but looking up at him. “I’m sorry,”

“Look at me,” she said, and he finally lifted his eyes to her. “Thirty-six thousand.”

“What?”

“That’s how many you evacuated from ANZAC cove. You. Not father, not me. You and your generals planned and executed that. Your balance is still positive, do you understand me?”

“Kiwi-bird,” He said because he was trying to argue, because she could read his mind sometimes, and he didn’t want her to, not now. He wanted to get up and move again and pretend he’d thrown up his sins with his stomach’s contents. “Don’t.”

“Thirty-six thousand.” She said again.

“Those weren’t directly... that kind of number is different from the ones you put back together on the table, Zee. It’s not the same. It’s not the same and it’s blood and it’s so much blood.”

“Look at me!” She said, this time harsh and sharp. “We do these things together, right? That’s what we said. My balance is your balance. You watch my back, I cover your arse.”

“Where the fuck was that cover when I got shot in the bum at Lone Pine, eh?” Jack shot back out of spite. But then she snorted so hard he thought she might puke, too.

“It’s not my fault it’s so bloody big!” She said. “You got the birthing hips, mate.”

“You are such an arsehole.” He countered, giving his side a rub where it most certainly did not round out into berthing hips. Then he was serious. “You mean it?”

“Heart and soul, dick.” She offered him a hand up, and he let her swing him to his feet. “Your balance is my balance.”

“Except at the commissary.” Jack huffed, unsure why that was the thought that popped into his head. “They won’t let me buy oranges anymore.”

“Correct. I trust you with my life and my immortal soul, but not the money.”

They push through the busy roads of new refugees and even more soldiers towards the pull of their father and the pull of whatever Alfred is, still half a stranger. It takes Zee pulling a “Do you know who my father is?” to some Oxbridge-educated fuck she might have rubbed elbows with in her school years to get them through the guard and into the command tent, and a damn good thing she did or Jack was ready to take out British soldiers like he had German. Arthur and Alfred are together, already half aware, and Father looks relieved, openly so. Not a good sign. Alfred looks bewildered. Less empire than boy startled out of bed. Because he still tends to sleep in one of those, even now. Because he is precious and held in reserve. Zee explains what happened and what needs to happen next. Jack fills in details as they go. His soldiers are the brunt just at that moment, and his heart is banging away in his chest when Alfred rolls around on him, full of piss. Looming because he does have two inches and an empire on Jack.

“You LEFT him?” He demanded, one fist gripping Jack’s collar. “You left Matt? What the fuck is wrong with you!”

“He can get away!” Zee said, trying to wedge herself in between, struggling as much with their father’s grasp as Jack was with Alfred’s. “Matt’s been doing this for years. He’ll be fine! We had bigger things to worry about!”

“Get the fuck off me!” Jack could do nothing about Alfred’s hold. His struggle was useless.

“Like what!” Alfred practically shouted. “What’s more important than making sure Matt gets home in one piece?”

“Like the entire western front, you dumb cunt!” Zee shoves her face up at Alfred’s, willing to argue even if she is a foot shorter.

“Enough!” Arthur slammed his hands down on the map-laden table and tugged Zee away, shoving one arm between Alfred’s chest and Jack’s, curling so he was in front of her. But he couldn’t break the grip Alfred had on Jack’s collar. “Get your hands off your brother, boy!”

“Fuck you!” That was all Alfred had to say to Arthur. Zee was tugging her arm back from their father and freeing herself.

“You left him there!” Alfred rounded on Jack again, closing the distance he already commanded with the grip on his collar.

“You always do this!” Alfred tossed back at Arthur. “You always leave him to do your dirty work. No one watching Matt’s back because why would anyone watch his back! Why would anyone give a shit except about how much killing you need done! Why should anyone watch his back?”

“I was!” Jack was on his toes, the angle of Alfred’s fist the only thing keeping him from using his jacket as a hangman’s rope. He didn’t care. “I was here, watching his back while you were home turning a fucking profit! We were here when it was all for nothing! You only showed up for what? For what? To take credit? Aunt Bridgie always said you were brave, that you were brilliant. She forgot to mention what a bastard you are!

“You shut your mouth. I’m not the one who just abandonded Mattie.”

“Ah, my dear boy, but you did that first.”

One sentence. One sentence, and that’s all it took. Father looked unbothered. Alfred’s hand dropped like he’d been slapped. Jack fell back, and Zee was there, throwing off Dad’s grip and under his arm in a moment. The room was silent. Jack breathed hard. He would have probably swayed if Zee wasn’t so close, half shielding her body from Alfred, half shielding his sanity from the shouting.

“Want another first?” Alfred wasn’t facing them now. This was an argument older than both of them, conducted in shouts muffled from the other end of the house. “I took his head off his shoulders at Yorktown. I shot our dear lord father’s jaw from his fucking skull and his skull from his shoulders and the lobsterbacks surrendered. And then they left. And when the gutters overflowed, you were born.”

Zee’s hand tightened on his, squeezing, squeezing like when the hospital ship she’d been on went down, torpedoed by that kraut bastard, and he’d dragged her corpse off a beach, and the only sign of life she could give him was the vice of her hand on his. I love you. It’s not true. I love you. It’s not true. I love you. It’s not true.

Arthur exhaled a laugh. “Goodness, I read you lot too much Shakespeare. Such a flare for drama, children.”

Alfred’s face twisted. “What the fuck is wrong with you?”

“Who’s us?” Zee countered. Jack wanted to throw up again. “What’s wrong with you? You two are the kraut fuckers, not us!” Father looked almost as shocked as Alfred. “Matt wouldn’t even be out there if someone hadn’t made mess! And it wasn’t us!”

The conversation had meandered, shot right from under them, from under Matt. Fuck.

“All right!” Dad intervened like he’d had the same thought. Hard and sharp like the furious fifties that marked the sea voyage home when Jack was small, he cut through the tension. “As flattered as your brother would be to see you defending what little of his honour he hasn’t left in a brothel, I rather think we should get to the task of finding him first, no? And perhaps, if you lot can manage more than one task at a time with the single wit I seem to have left you to inherit, we could perhaps even turn back what looks to be an entire German offensive that’s just caught us with our cocks out.” He paused and glanced at Zee. “Barring you, dear girl.”

Jack snorted so hard they almost toppled over. Alfred sighed like a martyr. A sigh to make him sound like Matt, if there ever was one, and leaned over the table. “Where’d you put your favourite knife this time, you old bastard?”

“Excuse you,” A note of laughter in a gravelly voice, still half-ruined by gas. “I am Father’s best knife. Only the finest for when the Krauts come for dinner, eh Dad?”

It was a pile-on, everyone rushing to get an arm around him. If Zee was his rock, the rest of them needed fucking mortar to stick together. Jack nearly elbowed Dad in the face as Arthur tried to look at a particularly large blood stain oozing from Matt’s shoulder but had to settle for turning his cheek and looking him in the eye a moment before he and Zee nearly got bowled over entirely by Alfred rocketing through. He practically picked Matt up.

“Let me down, for Christ’s sake.” Matt laughed. “I’ve got Gilbert brains on my shirt, bud, fuck.” But Alfred would do nothing but grip him and shake his head. He might have muttered idiot. Jack didn’t hear. Matt was looking over the Yank’s overly broad shoulders, nodding at them both with a wan sort of smile that said as much of pride as it did blood loss. Zee’s hand was on his shoulder, and he glanced at her.

“You want me to slip some arsenic his coffee?” Zee whispered, not doing half as good a job suppressing her grin as she thought she was. “They burn it so bad. It could be proper strong. Nice and quick like the cholera.” Her sense of humour was morbid like that, even if he wasn’t entirely sure it was humour.

“Naw,” Jack drawled. “Reckon I’d’ve taken it some kind of personal too if someone had left you out for the Krauts.”

He got an affectionate punch in the kidneys and a squeeze for his trouble.

“There’s nothing about you that came from a gutter.” She said, drawn tight to his shoulder. “Not a bloody thing.”

#the ask box || probis pateo#my writing || cacoethes scribendi#jack || a land of summer skies#zee || ahakoa he iti he pounamu#alfred || o beautiful for spacious skies#arthur || stone set in the silver sea

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexander Edwards was born on 4th November 1885 in Lossiemouth.

Alexander was the son of Alexander Edwards, fishermen of Stotfield, Lossiemouth and Jessie (née Smith); his brother James was lost at sea and his younger brother John, CSM Seaforth Hldrs awarded MM July 1916.

Alexander was educated at a local school in Lossiemouth Sch.ool, he was employed as a cooper making barrels for fishing industry;

On 1st September 1914 he joined the 6th (Morayshire) Battalion, the Seaforth Highlanders,[a part of the 51st (Highland) Division. After training in Bedford, the battalion travelled to France in May 1915.

By 1917 Alexander Edwards, had reached the the rank of sergeant, and on 31 July 191 demonstrated tremendous bravery at the Battle of Pilckem Ridge 7 on the first day of the Battle of Passchendaele.

The London Gazette of 14 September 1917 recorded:

For most conspicuous bravery in attack, when, having located a hostile machine gun in a wood, he, with great dash and courage, led some men against it, killed all the team and captured the gun. Later, when a sniper was causing casualties, he crawled out to stalk him, and although badly wounded in the arm, went on and killed him. One officer only was now left with the company, and, realising that the success of the operation depended on the capture of the furthest objective, Serjt. Edwards, regardless of his wound, led his men on till this objective was captured. He subsequently showed great skill in consolidating his position, and very great daring in personal reconnaissance. Although again twice wounded on the following day, this very gallant N.C.O. maintained throughout a complete disregard for personal safety, and his high example of coolness and determination engendered a fine fighting spirit in his men.

Sergeant Edwards was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions. Returning to Britain, Edwards received his Victoria Cross from King George V at Buckingham Palace on 26 September 1917. A week later he attended a reception in his honour at Lossiemouth, where he was presented with a gold watch and war bonds. He later returned to France and rejoined the 6th Seaforth.

On 21st March 1918 the Germans began their Kaiserschlacht (Spring Offensive). On 24th March Edwards was wounded and posted missing in action, presumed killed, at Bapaume Wood, east of Arras, France.

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Did the US entry into WWI in 1917 make a difference or was the outcome of the war already decided at that point?

The First World War was not decided by 1917. Unlike the Second World War, which was mostly decided by around late 1942-early 1943 (and given the vastly different industrial capacities and the extreme luck that the Axis had, even that might be generous), the First World War was a back-and-forth affair that could have easily gone the other way up until the failure of the Kaiserschlacht.

Thanks for the question, Anon.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

diese ganze sparte an kriegsaufrufskommentariat kann man ehrlich gesagt als nicht mehr als einen versuch, die eigene männlichkeit zu beweisen, werten (der natürlich besonders schade ist, wenn es hier um vermeintliche linke geht), aber manchmal schaffen die es wirklich, sich an dummheit nur zu übertreffen:

dass der autor sich bis jetzt krieg nur durch bücher vorstellen konnte (anstatt den nachrichten??), ist natürlich schon ein geständnis von geistiger unfähigkeit für einen ach so weltgewandten journalisten, aber dann auch noch diese auswahl: ich hab In Stahlgewittern vielleicht noch etwas frischer im gedächtnis, weil ich es gerade eben erst lese (bzw heute beende), aber eins kann man definitiv nicht sagen: dass Ernst Jünger gegen krieg geschrieben hätte. Ernst Jünger verherrlicht krieg als transzendente erfahrung und von dem, was ich vom rest seines katalogs gesehen habe, strotzt sein ganzes werk nur so von urfaschistischer gewalt. tatsächlich hat er sogar neben In Stahlgewittern das ganze nicht nur literarisch, sondern auch als essay in Der Kampf als Inneres Erlebnis erörtert.

eigentlich mag ich ihn aus literarischer sicht sogar, und als faschist, der den nazismus als degenerierte moderne empfunden hat, ist er eine wirklich interessante person, aber es ist für mich unmöglich mir vorzustellen, wie man Jüngers beschreibung der Kaiserschlacht - die einer religiösen offenbarung gleicht - lesen kann und bei dem urteil, er wäre kein eingefleischter militarist endet.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

BLAH 179 | Kaiserreich - War, 1918, with Jim McGeehin

Finally, we're in the home stretch. From the peace of Brest-Litovsk to the Kaiserschlacht offensive to the breakdown of the Central Powers and the winding down of the war in the fall, we're doing the whole picture.

Download the episode!

Our Patreon page at patreon.com/boiledleatheraudiohour.

Torrent

Our iTunes page.

Previous episodes.

Podcast RSS feed.

Stefan’s blog.

Jim’s blog

Jim on Twitter.

0 notes

Photo

The German Marne-Reims Offensive. German infantry manhauling a granatenwerfer forward in support of advancing stormtroops, 15 July 1918.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

The new years on the Western Front

German bunker at Dodengang near Diksmuide Belgium, December 2018

By January 1 1915, the hopes that the war would end quickly had dissolved into the mud of Belgium and France. The First Battle of Ypres in Belgium had ended the month before, and with it the tactics of open warfare for the next four years. Armies now faced each other for 450 miles across Western Europe, from the English Channel, across Belgium and northern France, all the way to the Swiss border. The Germans had fully moved to the defensive, reinforcing their trenches, building concrete bunkers up and down the line, and clearing positions for deadly machine gun and artillery fire. The Allies dug in as well, but had already begun making plans to attack in 1915 in the desire to evict the Germans from Belgian and French territory. The Allies built few bunkers and did not improve their trenches. Why bother, the Allied commanders thought, when they would be moving to the German positions soon enough? They would find this much easier said than done, and would experience heavy losses during the campaigns in the French Artois, at Loos and in the Champagne.

The hope for a breakout on the Eastern Front at Gallipoli, and for the USA to join the war after the sinking of the Lusitania, would both prove to be disappointing to the Allies. April of 1915 would see the first use of chlorine gas at St. Julien Belgium, with appalling results. Shockingly long casualty lists, British munition shortages, and with no end in sight, the 1915 year of the Great War came to a close.

Monument Le Mort Homme near Verdun France, December 2018

1916 would make the previous year of the war look tame in comparison. On February 21 the Germans launched Unternehmen Gericht (Operation Judgement) and attacked the French at Verdun. With a stated desire to “bleed France white”, German commander Erich von Falkenhayn looked to break both the strength of the French army and the will of the French citizenry to continue with the war. He was nearly successful. Instead, under General Philippe Petain, the French would rally to the defense of Verdun. The battle would cost Von Falkenhayn his job in addition to nearly one million German and French casualties, distributed more or less equally between the two armies. The German and French armies would each have successful offensives in the later years of the war, but the Battle of Verdun was a high water mark for both forces in terms of strength and morale.

Front Line July 1 1916, La Boisselle France, December 2018

On July 1 1916, British forces at the front along the Somme River in France, climbed over the top of their trenches and launched an attack. Wave after wave of young men walked across No-Man’s-Land into withering German artillery and machine gun fire. The bloodiest day in the history of the British Army saw nearly 20,000 soldiers killed, most within the first hour of the attack. By November Britain had suffered half a million casualties. The trauma of The Somme still resonates today throughout the United Kingdom, as well as Australia, Canada, India, and New Zealand. Not to be outdone, the French would suffer 200,000 casualties. The Germans took half a millions casualties of their own at the Somme.

Canadian National Vimy Memorial, near Givenchy-en-Gohelle France, April 2018

The slaughter of 1916 would continue into 1917. This year of the war saw dramatic events such as the Russian Revolution and their near total withdrawal from the war, as well as the United States declaring war on Germany. French Commander-in-Chief Joseph Joffre had been replaced by Robert Nivelle by the first of the year. On April 16 Nivelle launched an offensive of his own along the front in Northern France. German forces had already retreated to the fortifications of the Seigfriedstellung (Seigfried Line, or commonly known as the Hindenburg Line) and Nivelle’s offensive was a disaster. The French suffered nearly 200,000 casualties and gained practically nothing. In frustration at the meaningless loss of life, French troops began to mutiny. In May numerous French divisions flatly refused to fight. Nivelle was sacked and replaced by the hero of Verdun, Philippe Petain. “I am waiting for the tanks and the Americans” Petain stated. There would be no more pointless French attacks.

Tyne Cot British Cemetery and Memorial, near Passendale Belgium, April 2018

While Petain worked to end the mutinies, bring his soldiers back under control and rebuild French army morale, the British sought to keep the Germans distracted in Belgium. On June 7 1916 British Commander-in-Chief Douglas Haig launched the Battle of Messines. While deemed a strategic success for the British, both armies would each suffer 25,000 casualties at Messines. The next month Haig launched the Battle of Passchendaele (Third Battle of Ypres). A heavy bombardment that turned the landscape into a muddy soup, as well as constant rain, created conditions that were truly a hell on Earth. Soldiers that fell into the mud would slowly be sucked under to drown. Any attempt to help a trapped comrade would result in additional soldiers being sucked into the mire. Despite the atrocious conditions, repeated attacks were ordered, but almost no significant ground was gained by British forces. Final casualty counts are disputed, but by November anywhere between half a million and one million soldiers were killed, wounded or missing, with the numbers again being almost equally split between the British and German armies.

1918 would see the final year of the Great War, but it would prove to be just as horrific as the previous years. With Russia out of the war, the German Empire could focus their army on the Western Front. They had no time to lose as thousands of American soldiers were pouring into France each day. On March 21 the Germans launched the Kaiserschlacht offensive and broke through Allied lines in Belgium and France. Within a week they had attacked to a depth of 40 miles and by May German forces were back on the Marne and threatening Paris just as they had done in 1914. Philippe Petain’s defensive strategy stopped the German advance in July and, having advanced past their own ability to supply their forces, the Germans had to fall back. The Kaiserschlacht was over and Germany had suffered nearly 700,000 casualties.

Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial, Romagne-Sous-Montfaucon France, December 2018

On August 8 1918 the Allies, now under the unified command of French Field Marshall Ferdinand Foch, began the Hundred Days Offensive with the Battle of Amiens in France. German General Erich Ludendorff would later refer to this day as the as the Schwarzer Tag des Deutschen Heeres (Black Day of the German Army). Morale had crumbled among German troops and they were surrendering in massive numbers. The Germans suffered 30,000 casualties on that day alone. German soldiers called reserve troops moving up for battle “strike breakers”. German commanders, trying to rally their retreating troops, were told “You’re prolonging the war!” In September German allies were dropping out of the conflict. Bulgarian, Turkish, and Austria-Hungarian armies stopped fighting. With Americans now on the battle lines, the Allies were out of their trenches and fighting the Germans in open country. Each day more German soldiers would surrender and the Allies would gain more ground. October riots within Germany convinced the high command that no more was possible. The possibility of winning the war was gone and on November 6 a delegation set out from Berlin to negotiate with Ferdinand Foch and the Allies at Compiegne France. The Armistice took effect five days later.

Foch Monument at the Glade of the Armistice, near Compiegne France, April 2018

January 1 1919 saw the first New Year’s Day on the Western Front without battle in four years. But the war was not officially over. The Paris Peace Conference opened on January 18. It was not lost on the Germans that this date was the anniversary of the establishment of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701 as well as the establishment of the German Empire in 1871. The “Big Four” major powers of France, Britain, Italy, and the United States dominated the conference and worked together to unilaterally draft the Treaty of Versailles. In addition to the loss of colonial territories, the reduction of its military force, the levy of reparations and new national borders, the treaty placed the full blame for the war on the “aggression of Germany”. While US President Woodrow Wilson and the American delegation did not believe it was fair to lay the blame for the war solely on the German Empire, they were unsuccessful in getting the language of the treaty changed. The treaty was signed by representatives of Germany, France, Britain, the United States, Italy and Japan on June 28 1919, precisely five years to the day after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The Great War was now officially over.

The 1918 “Alsace-Lorraine” Monument depicting a German eagle impaled by a sword, near Compiegne France, April 2018

German popular resentment of the Treaty of Versailles, the humiliation of their defeat, costly reparations, the embittered memoirs of Ludendorff and other German military commanders, along with economic depression, and political instability, are all considered to have contributed to the resulting Nazi political success that began in 1925. Some believed, like economist and British delegate to the Paris Peace Conference John Maynard Keynes, that the conditions of the treaty were far too harsh and would end up being counter-productive to peace and the word economy. French Field Marshall Foch felt the opposite. Foch believed the treaty to be far too lenient on Germany. At the signing of the treaty he declared “This is not a peace. It is an armistice for twenty years.”

The Second World War began on September 1 1939 with the German invasion of Poland, twenty years and 65 days after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles.

Postscript: This is probably the last of the big text posts. From this point on I will be sharing the sites of the Western Front as they are today, 100 years after the end of the Great War. I have seen some pretty amazing things around Belgium and France and I look forward to sharing the images of these sites with you.

Additionally, if you are interested in a great book about the Paris Peace Conference I would highly recommend Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World by Margaret MacMillan.

January 4, 2019

#ww1#worldwar1#westernfront#greatwar#treatyofversailles#ludendorff#foch#Petain#DouglasHaig#Passchendaele#somme#verdun#Kaiserschlacht

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Final German Offensive

The Germans used about 20 tanks in their offensive, many of them captured British models. Most were quickly knocked out by French artillery.

July 15 1918, Dormans--The long-delayed German offensive against Rheims finally began shortly after midnight on July 15. The Germans knew that surprise would be key, but the long preparation time, the short summer nights, and deserters from an army tired of repeated offensives meant that the French had a decent idea of where the attack was to fall. The Germans would strike on both sides of Rheims--striking across the Marne in the west and in Champagne in the east, hoping to cut off the city. Its capture would greatly improve German logistics, would demoralize the French, and would hopefully draw off large numbers of reserves from Flanders, where Ludendorff wanted to strike next.

The Allies, aware the strike was coming, even down to the hour, launched their own preemptive barrage before the Germans did. Many of the German gas attacks were ineffective due to the wind. In Champagne, the French had learned well the lessons of the last few months, and kept only a token force near the front line. The German bombardment thus missed the main French positions to the rear, and the Germans infantry took heavy casualties advancing over open ground. By 11AM, the Germans realized their predicament, and halted their advance after failed costly attacks on the main French line.

To the west, the Germans had more success. The French had hoped the Marne would serve as an effective natural barrier, but they were able to cross the river at night with relative ease, and the French and Italian defenders in the area bore the brunt of the German bombardment. The Germans advanced four miles across the river, but the Allies had kept adequate reserves in the area to contain them. Among these were elements of the US 3rd Division, which held its position and even counterattacked against a German force that outnumbered them three-to-one. To this day, the 3rd Division (and especially its 38th Infantry Regiment) is nicknamed the “Rock of the Marne.”

Today in 1917: Kadets Leave Provisional Government over Ukraine Today in 1916: South Africans Fight for Delville Wood Today in 1915: South Wales Coal Miners Strike Today in 1914: Lützow Warns British Ambassador of Imminent Austrian Note To Serbia

Sources include: Randal Gray, Chronicle of the First World War; Robert B. Asprey, The German High Command at War; David Stevenson, With Our Backs to the Wall.

#wwi#ww1#ww1 history#ww1 centenary#world war 1#world war i#world war one#the first world war#the great war#kaiserschlacht#spring offensive#july 1918#Battle of the Marne#marne#Western Front#ludendorff

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

«Kaiserschlacht», último intento alemán para lograr la victoria.

«Kaiserschlacht», último intento alemán para lograr la victoria.

Primera Guerra Mundial. Cuatro ofensivas consecutivas llevaron a los alemanes a tiro de cañón de París, pero no pudieron doblegar a los aliados. Las trincheras fueron asaltadas. El frente, roto. París estaba de nuevo amenazado y los ejércitos del Káiser parecían otra vez incontenibles. ¿Serían capaces los alemanes de conseguir la victoria?… A principios del año 1918 la situación general daba un…

View On WordPress

#alemania#francia#gran bretaña#gran guerra#guerra#Kaiserschlacht#la historia esta viva#ofensiva de primavera#Primera Guerra Mundial#wwi

0 notes

Photo

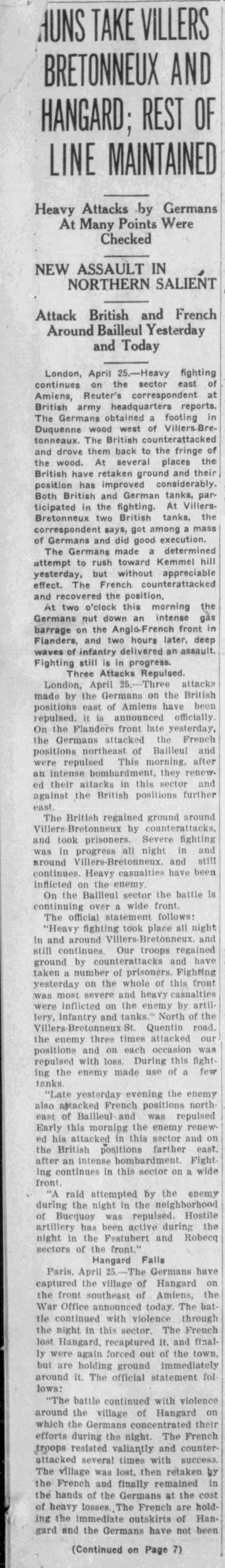

“Huns Take Villers Bretonneux and Hangard; Rest of Line Maintained,” Sault Star. April 25, 1918. Page 1. ---- Heavy Attacks by Germans At Many Points Were Checked ---- NEW ASSAULT IN NORTHERN SALIENT ---- Attack British and French Around Bailleul Yesterday and Today ---- London, April 25— Heavy fighting continues on the sector east of Amiens Reuter's correspondent at British army headquarters reports. The Germans obtained a footing in Duquenne wood west of Villers-Bretonneaux. The British counterattacked and drove them back to the fringe of the wood. At several places, the British have retaken ground and their position has improved considerably. Both British and German tanks participated in the fighting. At Villere-Bretonneux, two British tanks, the correspondent says, got among a mass of Germans and did good execution.

The Germans made a determined attempt to rush toward Kemmel hill yesterday but without appreciable effect The French counterattacked and recovered the position.

At two o’clock this morning, the Germans put down an intense gas barrage on the Anglo-French front in Flanders and two hours later deep waves of Infantry delivered an assault. Fighting still is In progress.

Three Attacks Repulsed London, April 15— Three attacks made by the Germans on the British positions east of Amiens have been repulsed, it is announced officially. On the Flanders front, late yesterday, the Germans attacked the French positions northeast of Bailleul and were repulsed. This morning after an intense bombardment they renewed their attacks in this sector and against the British positions further east.

The British regained ground around Villers-Bretonneux by counterattacks and took prisoners. Severe lighting was In progress all night in and round Villers-Bretonneux and still continues. Heavy casualties have been inflicted on the enemy.

On the Bailleul sector the battle Is continuing over a wide front.

The official statement follows: “Heavy lighting took place all night in and around Villers-Bretonneux and still continues. Our troops regained ground by counterattacks and have taken a number of prisoners. Fighting yesterday on the whole of this front was most severe and heavy casualties were Inflicted on the enemy by artillery infantry and tanks.

North of the Villers-Brctonneux-St Quentin road the enemy three times attacked our positions and on each occasion was repulsed with loss During this lighting the enemy made use of a few tanks.

"Late yesterday evening the enemy also attacked French positions northeast of Bailleul and was repulsed. Early this morning the enemy renewed his attacked in this sector and on the British positions farther east after an intense bombardment. Fighting continues in this sector on a wide front

"A raid attempted by the enemy during the night in the neighborhood of Bucquoy was repulsed. Hostile artillery has been active during the night In the Festubert and Rohecq sectors of the front."

Hangard Falls Paris April 25— The Germans have captured the village of Hangard on the front southeast of Amiens, the War Office announced today. The battle continued with violence through the night in this sector The French lost Hangard recaptured It and finally were again forced out of the town but are holding ground immediately aronnd it The official statement follows:

"The battle continued with violence around the village of Hangard on which the Germans concentrated their efforts during the night. The French troops resisted valiantly and counter attacked several times with success. The village was lost then retaken by the French and finally remained in the hands of the Germans at the cost of heavy losses. The French are holding the immediate outskirts of Hangard and the Germans have not been successful so far.

#amiens#villers-bretonneaux#bailleul#spring offensive#lunderdorff offensive#kaiserschlacht#storm troops#german offensive#offensive manouevres#imperial germany#deutsches heer#hangard#western allies#central powers#western front#world war 1

0 notes

Photo

L'offensiva di primavera tedesca, Marzo - Luglio 1918: L'A7V, pt. 1 Un carro tedesco A7V, con alcuni passeggeri in più sul tetto, avanza tra le strade di Roye nel Marzo del 1918. L'A7V, o più precisamente il Sturmpanzerwagen (Carro armato d'assalto) A7V, è l'unico modello operativo di carro armato costruito dai tedeschi durante la Grande Guerra. L'esercito tedesco infatti, a differenza degli alleati, punta su strategie diverse nel tentativo di sbloccare la staticità della guerra di trincea. Concepito dopo l'esordio dei carri armati britannici durante la Battaglia di Fleurs-Courcelette nel Settembre 1916, l'A7V entra in produzione nell'Ottobre dell'anno successivo e vede il proprio esordio sul campo di battaglia nel Marzo del 1918 durante l'offensiva tedesca Kaiserschlacht, venendo usato per la prima volta nei dintorni di San Quintino. Il carro, di cui vengono prodotto solo 23 esemplari – l'unico sopravvisuto, catturato da truppe australiane e spedito in Australia è in esposizione al Queensland Museum – è armato con un cannone frontale Maxim-Nordenfelt da 75 mm e 6 mitragliatrici Maxim disposte sui lati e sul retro del carro. L'equipaggio del carro varia da un minimo di 16 uomini a un massimo di 26, una cifra sorprendente se si pensa che i carri britannici avevano in media 8 uomini a bordo. L'armatura è di 30 mm nella parte frontale e di 15/20 mm sui lati, la velocità media di 12 km/h e l'autonomia varia dai 35 a un massimo di 70 km su strada. Il carro ha, per la struttura dei cingolati, la pessima abitudine di sbilanciarsi se costretto a passare su terreni accidentati ed è facile che rimanga bloccato nel passaggio delle trincee. Questo lo rende un carro non particolarmente di successo, quanto meno per la guerra sul fronte occidentale. The German Spring Offensive, March - July 1918: The A7V Tank, pt. 1 A German A7V tank advancing through the streets of Roye in March 1918. The A7V, or the Sturmpanzerwagen (Armoured Assault Tank) A7V, is the only operational tank built by the Germans during the Great War. The German army during 1916-1918, unlike the allies, is looking at different ways to unlock the static nature of the trench warfare. Conceived after the debut of the British tanks during the Battle of Fleurs-Courcelette in September 1916, the A7V enters production in October of the following year and sees its debut on the battlefield in March 1918 during the Kaiserschlacht German offensive, being used for the first time in the area near St. Quentin. The tank, of which only 23 are produced - the only remaining one, captured by Australian troops and sent to Australia is on display at the Queensland Museum - is armed with a 75 mm Maxim-Nordenfelt frontal cannon and 6 Maxim machine guns on the sides and on the back of the vehicle. The tank crew ranges from a minimum of 16 men to a maximum of 26, a surprising figure considering the British tanks normally have an eight men crew. The armour is 30 mm in the front and 15/20 mm on the sides, the average speed of 12 km/h and the range varies from 35 to 70 km maximum on roads. The tank has, for the structure of its tracks, the bad habit of getting stuck or tip over while crossing rough terrains or enemy trenches. This makes it a not particularly successful tank, at least not for the kind of warfare of the Western Front. Fonte / Source: Das Bundesarchiv, 183-P1013-316

#Kaiserschlacht#A7V#tanks#carri armati#Tanks in WW1#German Army#Esercito tedesco#1918#Roye#Fronte occidentale#Francia#Western Front#WW1#Prima Guerra Mondiale#Grande Guerra#Great War#First World War#History#Storia#storia militare della Grande Guerra#Military history

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Listening to a WWI podcast, 1700 nurses died? How many times did Zee, or Ireland die during the war I must ask?

Off the top of my head, Zee got blown to hell and back at Gallipoli once, died of dehydration there too but that was as a soldier and then she drowned on the Marquette, a transport ship and then once in Spring 1918 as the Germans smashed into the hospital she was working during the Kaiserschlacht. Brighid I don't see as a military nurse during WW1. She's got a lot going on in Ireland itself.

#the ask box || probis pateo#zee || ahakoa he iti he pounamu#Brighid || An Bearna Bhaoil#WW1 || half the planet having daddy issues in a trench

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(Better late than never)

THIS DAY, 100 YEARS AGO: KAISERSCHLACHT

On March 21, 1918, the German Army initiated Kaiserschlacht (The Kaiser's War), also known as the Spring Offensive of 1918. On the same day, the Second Battle of the Somme (or the Battle of Saint-Quentin, as the Germans know it) began.

The Germans, seeing an opportunity to attack the Western Front after Russia descended into revolution, amassed their forces against the weakened Allied troops and sent their sturmtruppen (storm troopers) to gain as much ground from the Allies as possible. They were able to push the troops to an area at the River Somme, between Arras and La Fère, and this loss for the British troops would be the Germans' largest territorial gain since 1914. It is in the last days of Kaiserschlacht that many Americans would first see combat.

What was significant about this battle is that war would finally become modernized to how we know it today. Soldiers kept moving and advancing to gain an advantage over the enemy. Right now, the final stages of WWI began, and it would be almost entirely mobile, like how it is the the Middle East these days, and would define how war is fought for the next century. Perhaps longer...

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Great War 100: Decisive Battles of the War Battle of Verdun - February 21, 1916 - December 18, 1916 - An attritional battle instigated by Germany to destroy the French Army -On the opening day of the battle, 1,220 German artillery pieces fired over 1,000,000 shells on Verdun and the surrounding areas in a 9 hour period.

Battle of the Somme - July 1, 1916 - November 18,1916 - Originally planned as a French offensive with minimal British support, intended to smash the German army and deplete their manpower. - With the German attack at Verdun, the French instead asked the British to carry out a large diversionary attack to relieve pressure on the French army. -The Battle of the Somme was one of the largest battles of the First World War, by the time fighting had petered out in late autumn 1916 the forces involved had suffered more than 1 million casualties, making it one of the bloodiest military operations ever recorded.

3rd Battle of Ypres, Passchendaele - July 31, 1917 - November 10, 1917 - Haig was convinced the fighting of 1916 (Somme and Verdun) had weakened the German Army and wanted to deliver the knockout blow in Flanders - As well as being Haig's preferred region for a large attack, the Royal Navy were worried about intense German submarine activity emanating from the Belgium ports and implored Haig to capture these areas.

Gallipoli - March 18, 1915 - January 9, 1916 - Originally a Naval operation, the main reason to attack this area was to open up more reliable trade routes with Russia, via the Black Sea. - There was also a feeling among senior British leaders that due to a stalemate on the Western Front, a new front was needed to ensure progress in the war.

Kaiserschlacht, The German Spring Offensive of 1918 - March 21, 1918 - June 12, 1918 Germany knew that their only chance of winning the war was to knock out the Allies before the extra resources of men and material from the USA could be deployed. The main thrust of the attack was against the British towards the town of Amiens. It was thought that after the British were defeated the French would quickly look for peace. - Amiens was a strategically important supply town with a large railway hub that supported both British and French armies. If this town was captured, it would severely impede Allied supply.

#Battle of Verdun#Battle of the Somme#3rd Battle of Ypres#Gallipoli#Kaiserschlacht#wwi#ww1#world war i#world war 1#first world war#the great war#war#military

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

On Kerensky, couldn´t he have made the case that the declaration of war was made by a tyrannical ruler, not the people of Russia? I know this sounds naive, but it seems like states that to various degree embraced democracy would have had at least a little hard time to accuse the new russian government of treason. (not that being hypocrites on that matter would be a new thing at all, I just wonder if that case could have been made to defend a separate peace)

Not if he wanted to continue counting on support from Britain and France. Kerensky had a relatively weak government, and needed to do what he could to secure support from both the workers’ soviets and the monarchists that wanted a restoration of the Tsardom. The Kornilov affair showed that the provisional government had a hard time maintaining legitimacy, and so they would have needed to rely on foreign support (and not have France cash in the extensive loans Poincare made to the Russian government) in order to maintain power. Similarly, Kerensky wanted to ensure that Russia maintained its power projection and legitimacy on the world stage, and it would have a hard time doing so if it was denied such by the other great powers of the day. France and Britain would be unwilling to support them, Japan at the time was allied with Britain and would have towed that line, and none of the other powers would have cared enough to be willing to extend support to Russia in the event that Kerensky established a separate peace, since the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk allowed Ludendorff to pull Eastern Front troops to the west for the Kaiserschlacht.

Thanks for the question, Rig.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

5 notes

·

View notes