#offensive manouevres

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

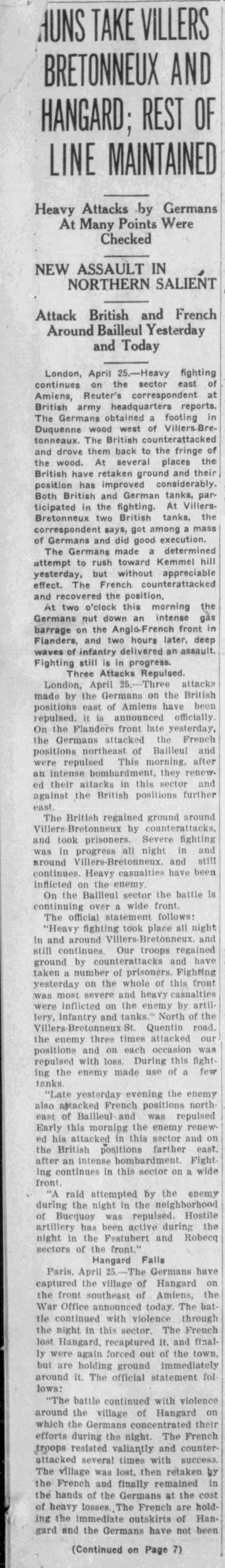

“Huns Take Villers Bretonneux and Hangard; Rest of Line Maintained,” Sault Star. April 25, 1918. Page 1. ---- Heavy Attacks by Germans At Many Points Were Checked ---- NEW ASSAULT IN NORTHERN SALIENT ---- Attack British and French Around Bailleul Yesterday and Today ---- London, April 25— Heavy fighting continues on the sector east of Amiens Reuter's correspondent at British army headquarters reports. The Germans obtained a footing in Duquenne wood west of Villers-Bretonneaux. The British counterattacked and drove them back to the fringe of the wood. At several places, the British have retaken ground and their position has improved considerably. Both British and German tanks participated in the fighting. At Villere-Bretonneux, two British tanks, the correspondent says, got among a mass of Germans and did good execution.

The Germans made a determined attempt to rush toward Kemmel hill yesterday but without appreciable effect The French counterattacked and recovered the position.

At two o’clock this morning, the Germans put down an intense gas barrage on the Anglo-French front in Flanders and two hours later deep waves of Infantry delivered an assault. Fighting still is In progress.

Three Attacks Repulsed London, April 15— Three attacks made by the Germans on the British positions east of Amiens have been repulsed, it is announced officially. On the Flanders front, late yesterday, the Germans attacked the French positions northeast of Bailleul and were repulsed. This morning after an intense bombardment they renewed their attacks in this sector and against the British positions further east.

The British regained ground around Villers-Bretonneux by counterattacks and took prisoners. Severe lighting was In progress all night in and round Villers-Bretonneux and still continues. Heavy casualties have been inflicted on the enemy.

On the Bailleul sector the battle Is continuing over a wide front.

The official statement follows: “Heavy lighting took place all night in and around Villers-Bretonneux and still continues. Our troops regained ground by counterattacks and have taken a number of prisoners. Fighting yesterday on the whole of this front was most severe and heavy casualties were Inflicted on the enemy by artillery infantry and tanks.

North of the Villers-Brctonneux-St Quentin road the enemy three times attacked our positions and on each occasion was repulsed with loss During this lighting the enemy made use of a few tanks.

"Late yesterday evening the enemy also attacked French positions northeast of Bailleul and was repulsed. Early this morning the enemy renewed his attacked in this sector and on the British positions farther east after an intense bombardment. Fighting continues in this sector on a wide front

"A raid attempted by the enemy during the night in the neighborhood of Bucquoy was repulsed. Hostile artillery has been active during the night In the Festubert and Rohecq sectors of the front."

Hangard Falls Paris April 25— The Germans have captured the village of Hangard on the front southeast of Amiens, the War Office announced today. The battle continued with violence through the night in this sector The French lost Hangard recaptured It and finally were again forced out of the town but are holding ground immediately aronnd it The official statement follows:

"The battle continued with violence around the village of Hangard on which the Germans concentrated their efforts during the night. The French troops resisted valiantly and counter attacked several times with success. The village was lost then retaken by the French and finally remained in the hands of the Germans at the cost of heavy losses. The French are holding the immediate outskirts of Hangard and the Germans have not been successful so far.

#amiens#villers-bretonneaux#bailleul#spring offensive#lunderdorff offensive#kaiserschlacht#storm troops#german offensive#offensive manouevres#imperial germany#deutsches heer#hangard#western allies#central powers#western front#world war 1

0 notes

Quote

Russia's provisional government, too, was faced with monstrous problems. It was being financed and generously supplied by the British and French but was increasingly unable to keep either its armies intact or its home front under control. On April 11th, and All-Russian Conference of Soviets voted to support a continuation of the war, but it also called for negotiations aimed at achieving peace without annexations or indemnities on either side. On April 15th, tens of thousands of Russian troops came out of their trenches to join with their German and Austrian adversaries in impromptu and nearly mutinous Easter celebrations. On the following day Lenin arrived in Petrograd from his long exile in Switzerland; Ludendorff, hoping to foment further disruption inside Russia, had approved his travel by rail from Switzerland via Frankfurt, Berlin, Stockholm, and Helsinki. Upon his arrival the Bolshevik leader began manouevring his followers into an anti-war stance calculated to take advantage of public discontent. The Russians had promised a May 1st attack in support of the Nivelle Offensive and had assembled a massive force for the purpose. The offensive proved impossible, however, to carry out. The troops had become ungovernable, and not enough coal could be found to operate the necessary trains. On May 2nd, Kerensky became leader of the provisional government. He tried to address the army's problems, but everything he did ended up making them worse. When he released all men over age forty-three from military service, a transportation system that was already on the verge of collapse found itself mobbed by middle-aged veterans desperate to get to their homes. When he abolished the death penalty for desertion, a million soldiers threw down their weapons. Many were drawn homeward by the hope of getting a piece of land when the great estates of the aristocracy were distributed to the people. Many were simply sick of war.

“A World Undone: The Story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918”

#history#military history#ww1#russian revolution#ussr#russia#vladimir lenin#alexander kerensky#communism

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

World War I (Part 59): More Politics

After the February Revolution and the Battle of Arras & Nivelle Offensive, political turmoil increased once again, with struggles for power erupting in Russia, Germany and Berlin.

Russia

In Russia, the tsar's regime had been toppled; the tsar's ministers were under arrest and rival factions battled for control of the provisional government. The politicians had to decide what form of government to use, and how to organize its worsening economy.

For the first half of 1917, there was still strong support for continuing the war. Minster of Justice Alexander Kerensky claimed that the revolution had been partially an angry reaction to rumours that the Romanov government might settle for a separate peace. He and the general staff were preparing a summer campaign, one that was smaller than the late 1916 Chantilly one.

But resistance against the war was growing, especially among the army and industrial workforce, which was where the most support was needed. By May, over 35,000 troops were deserting each month. On the home front, the situation was still volatile. Soviets had been recently formed, representing soldiers, sailors and workers; they were very skeptical about what Kerensky was doing. Lenin had returned from exile and was now in charge of the Communist Party's Bolshevik faction, which was stirring up opposition and becoming more & more bold in doing so.

Germany

In Germany, the struggle was simpler, focusing on who would be in control of the government. Nearly all the elite of German society were united against any meaningful reform, and their only real opposition was Chancellor Bethmann von Hollweg. The kaiser floated between both camps, and was overall a fence-sitter. He often agreed with Bethmann – for example, in 1917 he issued an Easter message endorsing his proposals for electoral reform. But he knew that he was being increasingly overshadowed by Hindenburg and Ludendorff.

These two blamed Bethmann for pretty much everything. They claimed that his failure to keep control over domestic policies was lessening the Reichstag's loyalty. Trying to arrange peace negotiations was making Germany look weak, and also encouraging the Entente nations to keep fighting. When strikes broke out in Berlin, they blamed him for that, too.

A standoff between them and Bethmann was lasting for months. A conference was held on April 23rd, where Hindenburg & Luidendorff demanded a war aims memorandum be approved – one that declared Germany's intentions to annex parts of Belgium and France, and large parts of the Balkans. Bethmann didn't resist, but a week later he placed a note in the files, in which he stated that he viewed the memorandum as meaningless – it implied Germany's ability to dictate peace terms to the Entente, which was completely unrealistic. He wrote, “I have co-signed the protocol because it would be laughable to depart over fantasies.”

On May 15th, he gave a speech to the Reichstag, declaring himself to be “in complete accord” with the generals on war aims, but also willing to offer Russia a settlement “founded on mutually honourable understanding.” These two things contradicted each other, of course, and caused Bethmann to lose potential support in the Reichstag – there was a growing number of Reichstag members who realized that the U-boat campaign was failing and wanted a negotiated settlement. On the other hand, Ludendorff became even more hostile towards Bethmann because of the peace-with-Russia section.

There were two sources of support for Hindenburg and Ludendorff – the first was their success as generals going all the way back to the Battle of Tannenberg. The second was from the most powerful & conservative parts of German society. This elite believed that only victory could prevent the ordinary people from demanding reform of the entire system after the war finished.

Pressure began to grow for Bethmann to be dismissed. The kaiser resisted strongly (to a surprising degree), because he realized that the new chancellor would be Ludendorff's pawn, which would cause the end of Bismarck's system. But the pressure was great – even his wife and son (the Crown Prince Wilhelm) took part. And the generals were willing to do almost anything to get what they wanted, whereas the kaiser was not.

Britain

Here, as in Germany, the struggle was between the head of the government (PM David Lloyd George) and the general staff, but apart from that there were few similarities. Unlike in Germany, a military-based challenge to government control of policy was impossible. The struggle was only over control of the BEF, but was still very intense.

Lloyd George faced off against Douglas Haig and General Sir William Robertson (Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and based in London). As the summer of 1917 began [June], the question of what to do with the BEF was paramount. Lloyd George's government had began shakily, but now had solid public support; he was very skeptical about the generals' tactics and strategies (with good reason). Any inclination he might have previously had to leave military things to the military, had been destroyed with the failures at Arras and the Chemin des Dames. He insisted that they wait for a great number of American troops to arrive before launching any more large offensives. He pushed for an Italian offensive while the French and Russians recovered & rested, and the Americans got an army ready.

There was actually no guarantee that America would send a whole lot of troops into the field. After Wilson's declaration of war, it wasn't certain that they were going to do anything more than send money, equipment and ships to their new allies. The Chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee declared that “Congress will not permit American soldiers to be sent to Europe,” but Wilson quickly proved him wrong on that. However, America didn't have much of an army yet – until a gradual buildup was authorized in late 1916, their regular army had only 130,000 men (barely putting them among the 20 biggest armies in the world). They had no tanks, almost no aircraft, and very few machine-guns (even though the machine-gun was an American invention). The general staff was legally limited to only 55 officers, with only 29 being allowed to be based in Washington – the country distrusted military establishments.

Also, their largest army unit was a regiment – there were no divisions. The military quickly organized a First Division and sent it to France to show theyr were serious. It was led by General John Persing, who had begun his career in fighting against the Native Americans. On July 4th, it marched through the streets of Paris to an enthusiastic reception. But it was much too small to be of any importance, and wasn't ready for combat. There weren't any other divisions ready yet.

The first draft since the Civil War was authorized. By mid-1917, every male from 21-31yrs was registered (it would later be 21-45yrs). 32 training camps were built within two months, each covering 8,000 – 12,000 acres (32.4 – 48.5 square km), and with 1,500 buildings capable of holding 40,000 men.

Nearly every noncom in the regular army was commissioned. New schools (with specialties from gunnery to baking) were established along the East Coast. The Entente sent veterans over to America to train American instructors in modern war. The French specialized in artillery, tactics, liaison and fortifications; the British specialized in mortars, machine-guns, sniping, bayonets and gas.

In order to manage all this, the War Department and general staff had to be greatly expanded and restructured. But even with all this expansion, Washington was not prepared for Pershing's estimate of how many troops he would require within a year. Soon after he arrived in France, he reported, “It is evident that a force of about one million is the smallest unit which in modern war will be a complete, well-balanced and independent fighting organization. Plans for the future should be based...on three times this force – i.e., at least three million men.”

Battle of Messines

Douglas Haig was still obsessed with Flanders, believing he could make a breakthrough at Ypres. The Royal Navy leaders agreed with him – on the Belgian coast, their naval guns could support the infantry; and it was a strategic objective that they had to take. The Admiralty had been working on plans for an amphibious invasion of the region since 1915. By spring [March-May] 1917, they were building huge floating docks that could land infantry and tanks.

Haig and his staff decided to seize this opportunity. With his staff, he worked out a plan to combine a new offensive out of the Ypres salient with an amphibious landing. They would thus be attacking Germany from two different directions, and force them to give up the Belgian coast. They might even be able to drive Germany out of Belgium entirely, by giving them no room to manouevre. And with their flank exposed, they might be forced back from the Hindenburg Line.

At the very least, the British would capture the Belgian ports of Ostend, Zeebrugge and Blankenberge. Germany would lose the ports that they were using to send some of their smaller submarines out from into the Channel – and this would strengthen Britain's position when it came to any peace negotiations.

But although the amphibious landing was a new idea, the Ypres offensive would be the same old strategy that had just failed in the Nivelle Offensive – a massive artillery bombardment followed by an infantry attack, supposedly leading to a breakthrough that the cavalry could exploit. Lloyd George was angry when he heard about it; and the amphibious landing wouldn't be possible until this supposed breakthrough had been achieved.

Haig attempted to placate Lloyd George by laying down a specific definition of the breakthrough – it would be counted as real once they'd captured the town of Roulers (11.3km into German territory), and then they would start the amphibious landing. Lloyd George, however, believed that Roulers was out of reach for them. Haig and Robertson believed he was being presumptuous to have an opinion on such things.

Weather was a very important factor in western Belgium. The region of Flanders is extremely flat, with scattered farmhouses, small villages and some patches of trees, but very little else. The ridges and hills of the Great War battles are barely noticeable today as more than wrinkles.

Flanders is also a very low part of the northern Europe's great coastal plain. The inhabitants spent centuries installing drains, canals and dikes so that it could be farmed, as previously it was practically an extension of the sea. Even today, it is the wettest a terrain can be without being an estuary.

Even in “dry” weather, you only have to dig a few spadesful of earth to strike water. It almost always rains heavily in late summer [August], and the whole area turns into mud. Because of the soil composition, it turns into a bottomless, gluey mess.

Haig was warned about this. Actually, the summers of 1915 & 1916 had been very dry for Flanders, unusually so. However, his staff looked at records going back to the 1830's, and reported that usually “in Flanders the weather broke early each August with the regularity of the Indian monsoon.” The London Times military correspondent was a retired Lieutenant Colonel, and he warned Haig against trying to launch a major offensive in late summer: “You can fight in mountains and deserts, but no one can fight in mud and when the water is let out against you. At the best, you are restricted to the narrow fronts on the higher ground, which are very unfavourable with modern weapons.”

“When the water is let out against you” would be referring to the Belgians in 1914, when they'd opened their dikes to flood the countryside east of the Yser River to hold back the Germans. The Germans would have learned from that, and might also use it against the British. Furthermore, heavy bombardment might wreck the fragile drainage system & cause flooding.

Haig didn't completely ignore these warnings, but he carried on anyway – he was impatient to begin while the Flanders region was still dry. As soon as the Battle of Arras was finished, he began building up an attack force at Ypres. Lloyd George hadn't given approval for this, and Pétain had warned Haig that this plan had no chance of success (this warning wasn't passed on to Lloyd George.)

For preparation, Haig wanted to establish a new strongpoint on the salient's edge, which could be an anchor for troops moving outwards. And he had a perfect way to do this, thanks to General Sir Herbert Plumer, who had been commander of the Second Army on the salient's edge for the past two years (during that time, ¼ of Britain's casualties had been at Ypres).

In 1915, Plumer had ordered tunnels to be dug towards the German positions opposite his line. In 1916, he expanded these tunnels into the biggest mining operation of the whole war – there were 20 shafts, some almost 800m long, and many over 30m deep to escape detection. They were drained by generator-driven pumps. The tunnels were extended towards the Germans, eventually reaching to below the Messines Ridge, which had been an excellent vantage point for German military spotters to survey the region. One of the mines was discovered & destroyed by the Germans, but the other 19 were finished and packed with explosives without the enemy finding out.

The Battle of Messines began with a week-long artillery bombardment, with the heaviest concentration of artillery of the whole war so far (one gun for every 7m of front). Then on June 7th, at 3:10am, the mines were detonated. They exploded nearly at the same time, blowing up the entire ridge into the air. Tremors were felt as far away as London, and David Lloyd George heard a faint boom at 10 Downing Street, where he was working through the night.

A lieutenant with a machine-gun corps later said, “When I heard the first deep rumble I turned to the men and shouted, 'Come on, let's go.' A fraction of a second later a terrific roar and the whole earth seemed to rock and sway. The concussion was terrible, several of the men and myself being thrown down violently. It seemed to be several minutes before the earth stood still again though it may not really have been more than a few seconds. Flames rose to a great height – silhouetted against the flames I saw huge blocks of earth that seemed to be as big as houses falling back to the ground. Small chunks and dirt fell all around. I saw a man flung out from behind a huge block of debris silhouetted against the sheet of flame. Presumably some poor devil of a Boche. It was awful, a sort of inferno.

A member of a tank crew said, “We got out of the tank and walked over to this huge crater. You'd never seen anything like the size of it, you'd never believe that explosives could do it. I saw about 150 Germans lying there dead, all in different positions, some as if throwing a bomb, some still with a gun on their shoulder. The mine had killed them all. The crew stood there for about five minutes and looked. It made us think. That mine had won the battle before it started. We looked at each other as we came away and the sight of it remained with you always. To see them all lying there with their eyes open.”

All that was left was a line of 21m-deep craters – the ridge had been destroyed, with very few British casualties. They'd penetrated about 3.2km into the German lines (at their farthest point), but Haig didn't want to advance any further at the moment. He'd achieved his objective; he didn't want to Second Army so far ahead that the artillery couldn't protect it; and he wanted to dig in before the Germans could counterattack. For a few hours, there was an opportunity to break deeply into the German lines, and possibly even through their broken defences, and it wasn't taken advantage of. Plumer was a capable commander, and perhaps the most important part of this battle was that he saw the advantages of a limited attack.

Lloyd George, however, still doubted Haig, and Haig still didn't have approval for the main attack. On June 19th, Lloyd George summoned Haig to a meeting with his recently-formed Cabinet Committee on War Policy. Haig was to explain his plans in detail, and Robertson also attended.

William “Wully” Robertson was born in 1860, the son of a tailor & postmaster; he was educated at the local church school and later became a pupil-teacher there. He joined the army at 1917, despite his mother's shame, and spent 10yrs in the ranks. A commission changed him from the army's youngest sergeant major to its oldest lieutenant. He served for a long time in India, learning several languages there. He served with distinction in the Boer War (1899-1902) and then returned to England.

After his return, he was a reform-minded authority on military training, and also an expert on the German army. He is the only English private soldier to have risen to the rank of Field Marshal (he was given that rank at his retirement, and also a baronetcy). Throughout his career, he made no attempt to get rid of his rough Lincolnshire accent.

Robertson had been focused on victory on the Western Front from early on in the war – he'd opposed alternatives such as the Dardanelles Campaign. In December 1915, he'd been appointed Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and become Haig's most important supporter. Because of this, Lloyd George distrusted him as well.

The June 19th London conference lasted three days. Haig laid out his plans and what he expected to achieve; Lloyd George questioned him constantly. He wanted to know: why they thought a Flanders offensive could succeed this time; what they thought the casualties would be; how the German forces were arranged; what the consequences of failure might be. He wasn't satisfied with the answers, and he made that very clear.

The Royal Navy was brought in, and they sided with Haig & Robertson. Admiral John Jellicoe (the sort-of hero of the Battle of Jutland) stated that Britain wouldn't be able to continue the war for much more than a year unless they captured the Belgian coast. This was actually unlikely – Germany only had a small number of smaller submarines going out from those ports. But Lloyd George couldn't prove them wrong because the claim was so completely speculative. The army & navy representatives were impatient with Lloyd George and his meddling (as they saw it).

Eventually, Lloyd George had to give in. By the end of the discussion, he only had one other committee member firmly on his side. The Conservative leader Andrew Bonar Law was also doubtful about Haig & Robertson's claims, but he said that he didn't think the committee could “overrule the military and naval authorities on a question of strategy” (which was pretty much what Bethmann had said 5 months earlier about the unrestricted submarine warfare issue).

Lloyd George knew that if he overruled Haig & Robertson without strong support (from both Liberal & Conservative members) then he would be exposed and vulnerable in the House of Commons. And Haig promised that if his plans didn't succeed quickly, then they'd be called off (like Nivelle had falsely promised). Lloyd George was still very much against the plan, but he told Haig to proceed with preparations while he waited for the final approval.

While the generals had won their case, this situation showed the strength of the British political system. Haig and Robertson hadn't won control of strategy overall – they'd only got permission for one more attack, and this permission had been granted by the civil government, whose authority was not diminished in any way. The PM had insisted on the conference, and it had been held, and he had had the last word. Everyone knew & accepted (if reluctantly in some cases) that Lloyd George and his committee had the ultimate authority, even if they'd given in. The constitution remained intact.

Germany's constitution was supposed to work in the same way, but it didn't. The chancellor was supposed to be in control – when Bismarck was chancellor, this had been the case, even though the kaiser was allowed to dismiss him at any time, and did so in the end. But the government leaders had no actual power base of their own – they weren't chosen by the legislature (as they were in Britain), and so the complications and problems caused by a lengthy war were causing the chancellor to lose his grip on control. Eventually, the system broke down, and a new one had to be improvised.

Hindenburg could have improvised the new system (he was the one person whom nearly all of Germany trusted) but he had no interest in it. So it fell to Ludendorff, who had been elected by no-one, and whom the kaiser greatly disliked. The war turned Germany's political system into a true military dictatorship, the first time that Germany had really had one.

Russia

The Russian authorities were struggling to hold their forces together. Rudolf Hess, who would be one of Hitler's top henchmen during WW2, was a newly-commissioned officer commanding troops opposite the Russians, and had recently returned from being wounded in action. In a letter to his parents, he described the chaos among the Russian troops:

Yesterday we saw heavy fighting, but only among the Russians themselves. A Russian officer came over and gave himself up. He spoke perfect German. He was born in Baden but is a Russian citizen. He told us that whole battles are going on behind their lines. Their officers are shooting each other and the soldiers are doing the same. He found it all too ridiculous. They can all get lost as far as he's concerned. We invited him to eat with us and he thanked us. He ate well and drank plenty of tea before going off. There was a lot of noise coming from the Russian side yesterday. They were fighting each other in the trenches. We also heard shots coming from their infantry but they were fighting at each other. Charming!”

But on July 1st, Kerensky launched his promised offensive (the Kerensky Offensive). Not enough troops were available for it to be as big as what had been promised before the revolution, but it had over 200,000 men and over 1,300 guns on a 48km-wide front. General Brusilov, now Commander-in-Chief, was in charge. It took place in Galicia – this was where Brusilov had had his earlier successes; Russian forces were more organized here & had better morale than in the north; and nearly half the enemy was Austrian rather than German. They were also well-equipped in artillery & aircraft thanks to their allies.

The offensive went very well at first – the initial bombardment destroyed much of the enemy's forward defences, and the infantry attack took a lot of territory. But the Russians didn't know that even the Austrians were using Ludendorff's new defensive system, and when the counterattack came, it was the final straw for the troops. They didn't even desert – they just quit the war on the spot, refusing to obey any more orders. They shot dead officers who attempted to restore order.

Only July 8th, the Russian Eighth Army basically ceased to exist. On the 18th, Brusilov was relieved of command. (He had had misgivings right from the start, but Kerensky had ordered him to carry out the offensive.) By July 19th, the Germans were driving a disorderly mob of Russians before them. Max Hoffmann (now Chief of Staff on the Eastern Front) was in command. Wherever the Germans advanced, the Russians fled; they even fled from the Austrians when they joined in.

This was basically the end of the war in the east. Russia had suffered only 17,000 casualties (including missing & wounded), which was relatively low compared to the last 3yrs. But the general collapse meant that they were finished. The Germans would attack again later in the north, but success there would be extremely easy. This was also the end of the provisional government – the way was cleared for the Bolsheviks.

Germany

Their success in routing Russia on the Eastern Front emboldened Hindenburg & Ludendorff even further, and they were determined to settle the political struggle in Berlin in their favour.

On July 6th, Matthias Erzberger had delivered a speech that shocked the nation. He was the leader of Germany's Catholic Centre Party, a moderate and a monarchist. In his speech, Erzberger showed that the submarine campaign had failed (he used information from international contacts who had been made available by the Vatican). He demanded reform and a stronger role in government for the Reichstag. He also insisted that Germany renounce territorial gains to secure a “peace of reconciliation”.

At this point, there was great struggle for control over policy (with many factions & many different positions). Erzberger's speech outraged the conservatives, and those who believed the Reichstag should be annexed attacked Bethmann. But the kaiser continued to support him.

Until Hindenburg & Ludendorff played their final card. On July 12th, a telegram arrived from their headquarters announcing their resignations. It stated that other resignations from the general staff were sure to happen as well, and that the reason was the impossibility of working with Bethmann.

The kaiser was angry, but could do nothing. (In Britain or France, these blackmail resignations would have been accepted without comment.) He asked Hindenburg & Ludendorff to come to Berlin to see him. Bethmann resigned.

The timing of this was not good. Monsignor Eugenio Pacelli (who would become Pope Pius XII in 1939) had spoken to Bethmann shortly before his resignation, and presented an offer made by Pope Benedict XV – the pope would mediate between the warring sides to try and end the war. Pacelli said that the first step would have to be for Germany to declare their intentions with regards to Belgium. Unless Germany was willing to restore Belgium's prewar borders, peace talks would be impossible, and the Vatican realized this.

The kaiser had long insisted that they needed to control at least part of Belgium, if they were to keep the country secure. But even he understood by now that it wasn't realistic. Bethmann had told Pacelli that Germany would agree to restoring Belgium's prewar borders if Britain & France also did so (he didn't ask the army for their agreement on this). He even talked about dealing with the Alsace-Lorraine issue to mutual satisfaction.

The Reichstag had a liberal majority, and that majority was growing. If they'd been given the opportunity, they would almost certainly have supported Bethmann. But now there was no such opportunity, and the Vatican's attempt came to nothing.

Factions put forward their candidates for the a new chancellor, but were rejected. Eventually, Georg Michaelis was chosen. He was an obscure bureaucrat whom the kaiser had never even heard of. He would prove to be a useless choice – he lacked experience, good judgment and strength of character, and even Ludendorff (whom he was eager to please) would soon be disappointed in him.

Ludendorff didn't actually want to be a dictator (suggestions he should become chancellor were ridiculed), but found himself responsible for everything, with no-one of any importance or any use to help him with the politics or diplomacy. Neither he, nor his agents, nor Michaelis managed to bring the Reichstag under control.

On July 19th, a large majority of the Reichstag approved a resolution that declared, “The Reichstag strives for a peace of understanding and the permanent reconciliation of peoples. Forced territorial acquisitions and political, economic or financial oppressions are irreconcilable with such a peace.” This infuriated the conservatives, and the government remained at war with itself.

#book: a world undone#history#military history#ww1#february revolution#battle of messines#kerensky offensive#russia#germany#britain#alexander kerensky#vladimir lenin#theobold bethmann von hollweg#wilhelm ii#paul von hindenburg#erich ludendorff#david lloyd george#william robertson#john persing#herbert plumer#alexei brusilov#matthias erzberger#eugenio pacelli#georg michaelis

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“British Train For Invasion of Reich,” Montreal Gazette. August 6, 1941. Page 11. ---- British troops are shown in offensive manouevres preparing for the time when they will attack and smash the enemy. Recently hints of the invasion of the continent by Britain have been growing. At the top men of the Suffolks practice getting over barbed wire defences by means of a ladder while at the right one of the men clears a tussock during a seashore exercise.

#world war II#british army#offensive manouevres#military training#military manouevres#suffolk regiment#barbed wire

0 notes