#there is no war in menegroth

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

the more i think about it the more i believe doriath not letting the refugees from himlad - even pass through their lands, let alone shelter there, was perhaps a contributing factor to that part of the fëanorian host’s. virulent hatred of doriath

#doriath#feanorians#my terrible headcanons#beleriandic politics in a nutshell#there is no war in menegroth#<- will probably be my ‘the iathrim are not blameless for how their relationship with the feanorians soured’ tag going forward#like i *definitely* think the feanorians lost people who would have lived if they hadn’t had to go around doriath#and they don’t really seem like the kind of people to not bear a grudge about it#it’s not the only reason but it is *a* reason#maybe even one used to justify things it absolutely does not justify#i’ve always felt like the second kinslaying - it’s not justifiable obviously#but it is the sort of thing you can justify to yourself if you’ve spent five hundred years marinating in feanorian kool-aid#and so has everyone around you#anyway. the tragedy of the feanorians and the iathrim is of two groups of people so determined to see the worst in each other#they keep giving each other increasingly persuasive reasons to never do anything else#if either of them gave the other side the benefit of the doubt even once i don’t think things would have turned out quite so badly

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Excerpt from Sorrow Beyond Words: Collected Testimony of the War of Wrath, 4th Edition; ed. Elrond Peredhel. Archive of Cîw Annúminas, inaugural collection]

“Simply reaching Menegroth was a struggle. Doriath had become a twisting nightmare of overgrowth and rot and mists, as Morgoth’s power warred with the remains of the Girdle and our old songs. Ai, our home, our haven! I know the name of every holly in Region, before the exile. We found deadfalls surrounded by dozens of animals who’d lain down beside the trees and rotted before they died. Blind moose more antler than flesh staggered towards us even after a dozen arrows. Vines covered in dripping thorns reached for our eyes. The cherry trees were overladen with fruits that smelled like gangrene. Deildhod stumbled into a nest of maddened vipers, and only escaped because their tails were all tangled together into a festering mass and could hardly move. We never saw or heard a single bird. I’m amazed we lost no one in that whole push through Region. No, I speak a lie. I know how we passed through with nothing worse than scrapes. Elrond was with us, and the ghost of Melian’s love still recognized her kin.

“Esgalduin had nearly been dammed by one of Hírilorn’s fallen boles, but the bridge still held. We crossed and reached the ruined gates, wrought twice and broken twice. Within there was only darkness to be seen; we knew not what manner of horrors Morgoth had sent to infest the city, but Ingwion was unwilling to leave them at the rear of his forces as he moved north, if it could be helped. Celeborn stood at Elrond’s right and myself at his left. Far less an honor guard than the heir of Elu Thingol and Melian Besain deserved. Yet in those dark days it was all the honor we could muster. King Dior Eluchíl had known thirty-six summers when he was unrighteously slain. Queen Elwing Nimaew thirty-five when despair took her to the sea. Lord Elrond Peredhel beheld the city of Elu for the first and only time in his twenty-ninth summer.

“Elrond stood before his inheritance and Sang. He sang a lament, for the lost endless years of joy and peace, for deep halls lit by birdsong and echoing with wisdom, for the Forsaken People who awoke the forest and earth with many voices, for the works of beauty never to be seen again on this side of the sea. He sang a promise, that the glory of Menegroth will be remembered in the songs of Middle-Earth for as long as its children endure. He sang thanks, for the protection the halls granted us until it could shelter us no more. As his song at last ceased, I thought I heard nightingales answering him.

“Stars shone on his brow, and his hair glistened as the vault of night, and the memories of our once-eternal bliss in the woods of Thingol’s realm under Elbereth’s gifts arose in my mind. Let Oropher dream of a deep hall for his own; let Celeborn reign where he will at his wife’s side! I knew in my heart, as the echo of nightingale songs faded, that there was no lord or king I would ever stand beside save Elrond Elwingion.

“The living stone in which our kingdom once thrived knew his voice, and at long last laid down its burden and passed. The darkness over Menegroth was lifted, and we went forth into its corpse, and no beast or orc could stand before us. I do not sing of what we found and left behind when we cast down the bridge and gave leave for the river to flood the caves. It is not worth remembering.”

#silmarillion#the silmarillion#tolkien#silm fic#elrond#doriath#menegroth#war of wrath#my OCs#war of wrath: sorrow beyond words#stormwritten#the Second Kinslaying occurred on this day in FA 506#you can observe the day of remembrance by burning a Son of Feanor in effigy#in remembrance I'm writing Sindarin Elrond because I've seen too much Feanorian Elrond recently#the narrator is a former senior Marchwarden who escaped the Kinslaying and brought refugees over the mountains to Celeborn and Galadriel#she'll never forgive herself for not being at Sirion for the Third Kinslaying#she becomes one of Elrond's chief counselors and one of the heads of Rivendell's forces along with Glorfindel#she and Glorfindel were definitely at each other's throats for years until Elrond yelled at them to chill#they may have hatefucked#sorry Erestor#she either dies when Celebrían is captured#or leads the search for Celebrían and sails west with her#in either case she'll never forgive herself for failing#“Nimaew” = “white/pale bird” I think#a name given to Elwing after her leap#she doesn't know about it yet

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maedhros' looking out the window like he's in a sad music video to Maglor's carpool karaoke road trip vibes

#song being loud#silmarillion#maedhros#maglor#this is pre-menegroth#after the war of wrath its Maglor's sad music video hours

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

#jrr tolkien#lotr books#lotr poll#tolkien legendarium#the silmarillion#lotr theories#sindar#doriath#celeborn#galathil#first age#years of the trees#second kinslaying#third kinslaying#beleriand#middle earth#war of wrath#sirion#menegroth#silm headcanons#silm elves

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about Maglor (as you do) and how the only death directly attributed to him is Uldor, the treacherous captain of the Easterlings who turned against the Union of Maedhros at the Nirnaeth Arnoediad.

Of course, we can infer that Maglor has killed quite a few people before Uldor, and will go on to kill many more. Between Alqualondë, Menegroth, Sirion, and his tenure as captain of the Gap, Maglor has plenty of blood on his hands. But the text is quite vague about his role in these killings. We are not told, for example, that Maglor slew Nimloth or Dior. We are not told the names of his victims at Alqualondë, or the names of the guards that he murders at the end of the War of Wrath. While Maglor is certainly involved, his individual contribution is “lumped in” with the collective guilt of the Sons of Fëanor.

…which makes his slaying of Uldor all the more interesting!

Suddenly, Maglor is acting as an individual. It is not the sons of Fëanor who slay Uldor, but rather Maglor himself. The manner in which he kills Uldor is also worth noting: Maglor defeats him in single combat, meaning that they probably faced each other one-on-one. In the death of Uldor, we see a rare instance of Maglor acting independently.

Why this sudden independence? I think Maglor takes a personal interest in Uldor because Uldor is a traitor. He is separating from the sons of Fëanor, something that Maglor proves incapable of doing. The death of Uldor emphasizes Maglor’s greatest virtue (which is simultaneously his greatest vice).

#silmarillion#silm#tolkien#meta#maglor#nirnaeth arnoediad#please don’t skewer me if I forgot something in canon

452 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the prompt thing, number 24 on the Silmarils list; choked with weeds and slime? IDK seems like a line you could do something interesting with.

Another one I’m answering a year late, but have some War of Wrath-era Elros and Elrond growing slowly apart! Thank you for the prompt 💕

“Just a little further,” Elrond says confidently, raising his torch. It does very little to illuminate the dank forest path ahead of them, but he does not seem deterred. “We’ll know it when we feel it.”

“Elrond,” Elros says quietly, trailing after him. He is not used to this position – not used to being the one to doubt. For so much of their lives it has been the other way around, has Elrond followed Elros charging head-first into wherever his will led them.

“You remember,” Elrond insists. “Naneth told us that the air inside Melian’s Girdle was cleaner and purer than any she had ever breathed since.”

Elros inhales, takes in the stench of rot and decay that clogs the forest, and thinks with longing of the clean salt air of the Sea. “The Girdle was fallen almost before Naneth was born,” he says. “It is not here, Elrond.”

“The forest will remember it, even so,” Elrond says. “Doriath was once the most blessed realm in Beleriand – and we its last heirs! It will remember us.”

Too often these days, in Elros’ view, does Elrond’s talk turn towards the power of memory. It makes him uneasy: he does not like to feel the edges of a rift between them, to understand so little the drift of his brother’s thought. Perhaps it is the knowledge of burned Sirion, and all that was lost with it, that haunts Elrond now – or perhaps the long shadow of Amon Ereb, that mausoleum in which they came of age, where the sons of Fëanor mourned the lost days of their glory, and Maglor’s every lullaby was half a dirge.

Beleriand was splendid once, it is true – but the land is breaking now, and the interminable war drawing into its final act, and Elros is more concerned with building something from the ashes than weeping for what was burned. But he does not know how to say this to Elrond, who is still leading him towards the forest’s heart, where Menegroth once flourished.

“Do you even know how to enter the city?” he asks instead. The path, choked with weeds and slime, clings unpleasantly to his feet and makes a squelching sound with every step. “The hidden entrance may now be lost.”

“Not lost,” Elrond murmurs, his voice losing a little of its bravado. “Perhaps it has forgotten itself – but we can call it back.”

“And how long will that take?” Elros argues. “Elrond, my men are waiting for me. I have not the time for a fool’s errand.”

Elrond turns back to look at him for the first time. For a moment Elros is oddly glad of that, that he might still capture his brother’s attention with a sharp word: but the thought is almost immediately followed by a hot flash of shame, for hurt flickers briefly in Elrond’s eyes. It is the sort of thing Maedhros used to do, in his worst moods – goad and goad until at last Maglor gave him some reaction, often too imperceptible for the twins to see. Elros does not want to be like Maedhros. Does not want to think of Maedhros, wants to shake off all the clinging ghosts of his childhood and look now to the world ahead.

But: “It ought not take long,” is all Elrond says, mildly.

They walk in silence, Elros breathing through his nose. He thinks again of the Edain under his command, whom he left waiting at their new outpost a little south of the forest. It has been long enough since he and Elrond last went away on an adventure of their own, for Gil-galad cannot often spare his brother from his duties, and Elros too is a commander in his own right. Besides, he did not think his men would understand their object: most of them have grandparents too young to remember Doriath before its fall. Still he does not like to abandon them, does not want them to think him just another elvish princeling, a stranger to mortal troubles and mortal woes.

But nor could he have let Elrond set out on this quest alone.

In the silence Elrond begins to sing a canto of the Lay of Leithian, of Lúthien dancing in the forest glades to Daeron’s music. Elros joins him, for their voices yet ring stronger together than apart – but he can put little conviction behind the song. The forest that his foremother loved is dead now, and so is she – they cannot resurrect her with their poems and their songs, necromancy dressed up as memorials, she is fled where they cannot reach her. Elros wonders if she was glad to do it.

Elrond’s eyes keep flitting between the dark, foreboding tree-trunks, as though he cannot quite understand why they do not become green and fair again under the influence of his song. At last he stops singing, a little frustrated now. “I cannot find a way,” he says, “it is all dark and rotten.”

“Well, there have been all manner of foul creatures crawling through these forests since Doriath fell,” Elros says sensibly. “I would be surprised were it not polluted.”

“Why will it not cleanse itself?” Elrond says, his voice barely above a whisper. “Why will it not remember how it used to be?”

Every two years or so Elrond will come to Elros with a plan to reach out to Maglor and his brother, and bring them before Gil-galad to face justice and redemption. Each time Elros tries to make him understand how impossible the idea is – and it works, for a year or two.

He is not accustomed to thinking of his brother as childish – not accustomed to feeling so very old as he does right now, seeing the stunned bewildered hurt on Elrond’s face.

“It is tired, Elrond,” he says. “Let it sleep.”

For a moment Elrond’s face crumples, and Elros thinks he must weep; then he says, quite calmly and cheerfully, “Well then, we had best be getting you back to your men,” and sets his course for the forest’s southern border.

The victory feels hollow, to Elros: but then, they all do.

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

You Can't XXXX in Here, This is the War Room!

Fandom: The Silmarillion

Pairing: Maedhros/Thingol

Summary: Blowjob diplomacy.

GOD okay I actually got something out for @silmsmutweek (Day 2: Crosscultural Relationships). Complete with outdated quote reference.

AO3 | Pillowfort | SWG (other links to come, when I feel like it)

It was said that the reason Elu Thingol so rarely ventured out from under tree was because his life was intertwined with that of the forest. Sometimes, it was hinted that this was the cost of his union with Melian the Maia; other times that it was a burden he had taken on for the prosperity of Doriath. Maedhros suspected the true reason was far more prosaic: Thingol simply preferred not to stray far from his wife and daughter.

Nevertheless, he had come to Himring.

With him came a whole retinue of Doriathrim, including Captain Mablung, who had never taken much of a liking to Maedhros, and, to Maedhros’ chagrin, his loremaster and favorite minstrel, Daeron, who had an irritating habit of writing insulting rhymes about anyone who might amuse him (usually those who desired it the least). Some two hundred Iathrim accompanied the king north, while Queen Melian and Princess Lúthien remained to rule over Doriath.

Nearly five years had passed since Maedhros had been in Doriath.

In the interim he had maintained a correspondence with the king, and he had believed that his memory was keen and kept the details of that visit in good order, but he was beginning to falter in that conviction.

They had met in Himring’s war room—so the residents of Himring castle had begun to call the hall where Maedhros convened with his captains and generals—to discuss the war. Always, the war. All his months in Menegroth had not been enough to bridge Maedhros and Thingol’s differing views on how it ought to be approached, yet if Thingol did not bend to Maedhros’ will, he did continue to listen to Maedhros’ arguments, and Maedhros would have to find reward in that.

Though it was not the war foremost on Maedhros’ mind, even as he gave Thingol and his companions more detailed updates than he was able to provide by letter.

With distance, and time, it had been easier to tell himself that his experience in Doriath was an anomaly. That he had gone a little dizzy and gotten off course, but that it was no more than that. The frequency with which Elu Thingol had appeared in Maedhros’ thoughts since was easier to dismiss when he was so many leagues off, out of Maedhros’ reach and therefore, as good as a fantasy. Now he was in the room with Maedhros once more, and memory did not serve for the full glory of the Greymantle, the Elf who had ensnared a Maia.

Maedhros did not ask Thingol to stay behind as the others filtered out of the room, but he did. He murmured something to Mablung and his men left him, and when the door closed on Mablung’s heel, Maedhros was far too aware that it was the first they had been alone since they had said goodbye in Menegroth—not the formal send-off he had been given, but before that, in Maedhros’ private chambers.

Thingol leaned against the back of one of the chairs around the table strewn with maps and movable figures representing various forces and studied Maedhros with eyes of piercing gray, aglow with the blessings of Telperion and Laurelin, whose light would grace Elfinesse no more. His crown was woven that day of thick vines of ivy, with a peppering of small white flowers Maedhros did not bother to identify. Thingol was resplendent in jewels, and he enjoyed wearing them, but if Maedhros had to say, he preferred the king like this, adorned in the flora of his realm. Maedhros had thought many times in the days preceding Thingol’s arrival what he might say, but each now sounded trite, pathetic, or melodramatic in turn. Thingol did not rescue him either; as the silence stretched on, Maedhros’ brain skidding off track as he tried to land on a proper greeting, the corners of his mouth began to life in an amused smirk.

At length, just before Maedhros could say something about the issue of joint troop exercises—something only tenderly approached from either side—Thingol disarmed his efforts with: “I have dreamed of you since you left.”

Maedhros’ mouth was lined in wool.

“Good dreams, I trust.” His voice sounded to him as if it were someone else speaking, because while his mouth moved, his mind was busy screaming its reciprocity of the claim. Now, with Thingol before him, with his low, smooth voice in Maedhros’ ears, with his form just a few paces out of reach, Maedhros’ memories of those dizzy days in Menegroth seemed to explode in vividity, from his first suspicious approaches to his final tight goodbyes.

“Good and bad,” Thingol replied simply. His long fingers stretched along the back of the chair, and the memory of those spidery hands combing through Maedhros’ hair made his knees wobble.

“Bad?” he queried, quirking an eyebrow.

Thingol stroked the back of the chair and simply gave Maedhros a look as if he expected Maedhros to know to what he referred. And didn’t he? They both knew how familiar Maedhros was with the realm of nightmares. Briefly, this opened up a shocking line of consideration: that Thingol had dreamed of Maedhros suffering, and counted this as a nightmare. It was something more exposed than Maedhros had expected to hear from him so soon into this visit, and he put it aside for the time being.

Instead, he crossed over to where Thingol stood.

“I am bored with dreams,” he said, and gripped the front of Thingol’s robes. It was a lie to say he had forgotten that he needed to tilt his chin up to meet Thingol’s gaze when they stood this close, for it had agitated him too much to forget it, but he had perhaps lost the full sense of the feeling.

Thingol was not bothered with Maedhros’ audacity. Rather, he looked only more entertained. He stroked a hand down Maedhros’ cheek, tracing his fingertips along the edge of Maedhros’ jaw.

“Perhaps this is a dream,” he suggested, yet for the amused slant of his mouth, there was something softer in his gaze which Maedhros could not look away from any more than he could acknowledge it.

“No,” he answered at once. “It is not.”

“You sound so certain.”

“I would know if it were.” The dreams in which Maedhros had occasionally taken comfort over the years could not hold a candle to the intoxicating reality, and if he thought this line of thought too obscure for Thingol to follow, he was wrong.

The king’s smile widened.

“Do you find the truth more pleasing?” he asked.

Maedhros thought only I do, and said nothing, and then leaned up to secure his mouth over Thingol’s. If he had been unsure at the start whether Thingol would wish to continue their trysts of before, the king’s fluttering lashes and teasing touches of the last few minutes had reassured him. And indeed, Thingol gripped his hips at once, pulling Maedhros against him with strength that still surprised him for all he had felt it before, and Maedhros gasped into his mouth, unable to stop himself from attempting at once to press against Thingol’s thigh. Every dream he’d had about Thingol since their last meeting seemed to rush back over him at once, and his body was one giant ache.

The king’s mouth parted; his tongue pressed against Maedhros lips, past the seam; his hands slid back to grasp at Maedhros’ ass, and Maedhros swallowed a whimper. In Himring, Maedhros was the final authority. Among all his brothers’ lands, he was the final authority, no matter how many crowns they stacked on Fingolfin’s head. Among their mortal allies, his word was all but absolute. But with Thingol, it was not so. With Thingol, he could—and often was—overruled. And he was not asked to be an authority in anything.

Maedhros wanted to swallow him, to rend his flesh and nourish himself with it, keep it for himself as a part of his own body, and yet he was assured that Thingol would not permit such a thing to pass, and so Maedhros need not temper his fire, for Thingol would ensure it did not do harm. If Maedhros was the fire, Thingol was the hearth which ensured no damage would come to the home.

Thingol’s hands moved up to cup Maedhros’ face, and a shudder went through him at the delicate touch; when he drew back for air, panting, flushed, he was looking directly into Thingol’s eyes, so near he could count his individual eyelashes and see the spokes of his irises. His flesh hand was still fisted in the front of Thingol’s robes.

For a moment it was quiet but for their heavy breathing, as they studied one another, both on the verge of speaking, or choosing not to speak. Thingol’s thumb stroked Maedhros’ cheek. Maedhros could feel himself swelling almost more in response to these more innocuous touches of Thingol’s than of the groping of his ass.

Eventually, rather than speak, Thingol kissed him again, and Maedhros surged up against him; this was easier than words, easier the confessions, easier even than writing Thingol letters in which he constantly debated how businesslike it ought to be and what, if anything, should be said of his own feelings. He tried to draw Thingol away from the table, but Thingol jerked him back, digging his fingers into Maedhros’ belt and holding him firmly in place, a bit of physical control that made Maedhros’ cock throb with all the urgency of his body telling him the time was nigh to create an heir to the family name.

Then the king’s hands went to his hair, and Maedhros did not know or care if this lord of Sindar knew anything about Noldorin cultural customs regarding hair, he only knew that he had wanted this almost more than he wished to keep breathing. His hand scrabbled at Thingol’s chest, the prosthetic against Thingol’s ribs, probably pressing too hard, and he had managed to insinuate one of his legs nearly between Thingol’s knees.

Maedhros was biting at Thingol’s lower lip, pulling with his teeth, which the king allowed to a point, and then gripped Maedhros’ hair tight at the back of his head and pulled him away. Maedhros was short of breath again, and his skin felt as though he was a storm cloud, a repository of lightning.

Thingol observed him for a moment, with a self-control that made Maedhros shaky on his feet, then leaned down and pressed his hot mouth against the crook of Maedhros’ neck, which made Maedhros shiver and nearly go limp in his grasp until he felt the sharp nip of the king’s teeth, which had him alert again at once. Thingol bit him to the point of pain and then softened it by lapping at the spot with his soft tongue, and Maedhros was glad that Thingol could not see the wanton expression he was giving to the windows, though he could doubtless feel how Maedhros’ flesh hand had shifted to claw at his back, fingers bunching up the fabric.

Maedhros tried to press closer, and choked on an effort to swallow when he was finally able to feel the king’s arousal against him. He did not think; his flesh hand was fumbling for Thingol’s crotch immediately, eager to press his fingers against that bloom of desire, kneading his hand against this evidence that Thingol had wished for this as well.

Thingol gave a low, almost sighing sound of approval and curled more over Maedhros’ form for a moment, before he retreated to look at Maedhros’ face (which he schooled into something hopefully less obscene).

“What do you wish for, Maedhros?” he asked. Maedhros hated this game almost as much as Thingol enjoyed it. Their first time together in so many years, Maedhros would have hoped that Thingol would simply give him what he wanted—as he so often seemed to know without Maedhros having to voice it—but of course he had missed making Maedhros say it out loud.

Stubbornly, Maedhros remained silent.

When Thingol did not give way either, Maedhros simply began to sink to his knees, determined to have what he wanted, but Thingol slipped away from him, and Maedhros felt a chill even in Himring’s well-heated core suddenly bereft of the king’s closeness. Thingol ambled down the length of the table to where Maedhros’ own chair sat at the head; he gripped it by the back and dragged it well away from the table and flicked it with a careless hand so that it faced Maedhros. With a swirl of his robes, he took a seat, his knees spread so far apart that Maedhros could clearly see the bulge of his cock pushing at the fabric.

“Then have it,” he said and Maedhros released a silent prayer of gratitude. For what, he wasn’t entirely sure, except that at least a part of it was that he did not have to say aloud what he had been thinking.

Out before him stretched the king’s long, shapely legs (which was the only reason Maedhros had yet determined for why Melian sometimes called him “grasshopper,” usually attached to a great many cloying adjectives) and he seemed entirely as comfortable as if he sat upon his own throne back in Menegroth.

He came to Thingol at once, determining that he would have more time to admire Thingol’s legs later, and hit the ground between Thingol’s feet so hard he was sure his knees would be bruised by the evening.

His flesh hand trembled as he parted Thingol’s robes, and he licked his lips reflexively when he revealed the king’s shorts and the proud tent there. He jerked at the waistband, impatient, pulling Thingol’s cock out as quickly as he could and lowering his head to kiss at the hot length. Thingol groaned and one hand was in Maedhros’ hair again, stroking and tugging gently.

“Such an industrious one you are,” he breathed. Maedhros ignored him, and took the tip of the king’s cock into his mouth. Thingol’s hand pulled a bit more firmly against his hair, but he pressed against the feeling, taking more of Thingol in, until he let out another groan, his hips canting towards Maedhros’ mouth. “Good boy,” he panted, scratching affectionately at the back of Maedhros’ scalp.

It was just as he remembered: there was so much of Thingol, but Maedhros was set on his purpose. Perhaps more than he ought to have been: his prize struck the back of his throat, making him gag, but he tried to swallow it anyway. Thingol briefly tried to withdraw, but Maedhros ducked his head to follow, drool dribbling over his chin as he made a truly valiant effort to take all of Thingol’s considerable presence.

Thingol quickly forgot his concern for Maedhros’ single-mindedness, his head tipping back against the back of the chair, soft noises of pleasure whispering past his lips as Maedhros sucked ardently at him. He used his hand to vigorously stroke what of Thingol he couldn’t get in his mouth and if he had a moment of thinking about the sight that would greet anyone who entered, of the lord of Himring, the heir of Fëanor, of Finwë, on his knees worshipping the cock of Elu Thingol, seated in Maedhros’ own seat of rule, his throne as it were, then it served only to thrill him more (mainly because he did not have the presence of mind to consider it realistically).

Thingol pulled at his hair again and Maedhros groaned around his full mouth, bobbing his head more enthusiastically, relishing the tension that went to the roots of his hair and made goosebumps break out against his skin. Very quickly it seemed everything he touched was a mess of his own saliva, but he didn’t have time to worry about that.

He could have done this with someone else in the years since he’d left Menegroth. He hadn’t.

His prosthetic hand was braced against the leg of the chair as Thingol’s hips began to shift rhythmically towards him, gently at first, then with more insistence. When he made Maedhros gag again, he pulled Maedhros’ head back forcefully, but when he gazed down on Maedhros’ face, his cheeks pink, his lips wet and red, his chin shining with spit, he found himself enraptured.

“I want it,” Maedhros said hoarsely, leaning down to kiss Thingol’s slick cock. “I can take it. I don’t break.”

Thingol considered this for entirely too long, then loosened his grip on Maedhros’ hair and let him at his goal again. Maedhros swiped his tongue over Thingol’s balls before dragging his tongue along the length of him and starting to take him in again. One arm he hooked behind Thingol’s knee, his flesh hand resting on Thingol’s thigh.

“Be careful of yourself,” Thingol murmured. “I will be very disappointed otherwise.” It was true that Maedhros often pushed himself beyond reasonable limits in all things. It was also true that Thingol would trust him, until proven unreliable, to voice his own boundaries.

Soon he had Thingol stifling moans again, rocking his hips towards Maedhros’ mouth with poorly-disguised need, guiding Maedhros’ head with his hand to get the angles he wanted. Every response, every hint of the suggestion that Thingol wanted this, went through Maedhros like swallowing a brand of fire. He was only dimly aware of his own arousal straining frantically against his clothes, and he was content to ignore it to focus on the increasingly aggressive rhythm of Thingol’s hips.

“That’s it,” the king breathed, massaging the back of Maedhros’ head with his hand. “Good boy, yes, that’s it.” Maedhros head him swallow down a louder moan and if his mouth had been less full, he would have smirked. “I’m going to finish soon,” Thingol warned him with the carefully moderated tone that meant he was on the verge of losing control, a narrow space which Maedhros would have inhabited indefinitely if he could have. “I want you to swallow.”

As ever, the tension between being aroused to be ordered by Thingol and the balking of his pride seized Maedhros, but in the end, he ran out of time to decide if he wanted to spit on the floor just to be disobedient: Thingol came while he was still thinking about it.

It was what he wanted anyway—to suckle at Thingol’s cock as the king thrust his seed down Maedhros’ throat, spasming his pleasure against Maedhros’ face. The taste was never something he’d enjoyed, but the feeling—that he had craved since Thingol had first dismounted his horse in Himring’s courtyard.

After, Thingol sank boneless back into the chair, his eyes fluttering shut.

“I will assume, then, that you are pleased to see me,” he remarked, eyes still closed.

Maedhros sat back on his heels, trying to wipe his face clean with the back of his flesh hand.

“I am not displeased,” he said primly, with a thick pearl of Thingol’s ejaculate still at the corner of his mouth, and Thingol opened his eyes to laugh.

“Not displeased,” he echoed. “Why Maedhros, I do believe this is as ardent as I’ve heard you. Should I expect a proposal forthwith?”

Maedhros snorted and rose to his feet, slightly unsteady as his knees protested their unceremonious treatment. He felt, somehow, calmer, although his own body was increasingly trying to make its needs known.

Relaxed in Maedhros’ chair, Thingol made himself presentable again, smoothing his robes down as if Maedhros had not just moments ago had his head buried in them. The king rose in a fluid motion, his silver braids glinting in the light.

“Perhaps my host will now allow me to return a favor,” Thingol said, gliding up to him, one hand reaching to cup Maedhros through his clothes before he could get too far away. Maedhros’ eyelashes fluttered, but he said:

“You needn’t, my guest.” This he used to poke at the way Thingol had addressed him in Menegroth, and it pleased him to see Thingol smile, understanding the jest.

“No, I needn’t,” he agreed, stroking Maedhros almost fondly. “Yet I wish to do so. Will you deny your guest his desire?”

“Surely you would find a way to make it a problem for me,” Maedhros groused without bite.

“It seems to be a problem for you presently,” Thingol pointed out, at which point Maedhros became aware that he was leaning towards Thingol to press nearer to his hand. Thingol kissed him, and Maedhros surrendered. He let Thingol back him up against the war table, and then turn him around, so that his back was against Thingol’s chest. He allowed Thingol’s hands to root through his clothes while he nibbled against at Maedhros’ neck and ears, until he reached what he sought, and took his time drawing Maedhros’ cock out.

“Mm…”

“You were right, about the dream,” Thingol murmured, and Maedhros shivered against him. “None of those dreams ever pleased me as much as this.” Thingol’s hand stroked him, while the other fondled his balls, and Maedhros groaned, not bothering to stop the movement of his hips against Thingol’s hand.

He was aware too late of what Thingol meant to do, and past caring by then—Thingol stroked him until Maedhros teetered on the edge, biting his lip past the point of pain to keep quiet, where Thingol held him exquisitely, as he was wont to do.

“Are you ready?” The king’s voice was soft when he spoke, and if Maedhros had asked Thingol to let him back down, he would have, and not complained or needled him about it. If Maedhros had asked to be held in restraint longer, Thingol would have done it gladly. But Maedhros only gave a jerky nod, so Thingol stroked him with purpose to his finish, until Maedhros could not stop himself from spilling across his table (not, however, on any of the maps, which he later surmised Thingol had minded).

“You’ve made a mess,” he gasped.

“You’ve made a mess,” Thingol corrected, sniggering as if he were not a king of Elves, one of the oldest corporeal beings of Arda, the sworn husband of a divine Maia.

Maedhros made a wordless noise of complaint, but Thingol nuzzled against his neck and tucked his cock away, although Maedhros was relatively sure he wiped his hands on Maedhros’ tunic and robes as he rearranged them.

“I am quite pleased this could be a productive meeting,” said Thingol briskly as he drew back, tucking a loose lock of hair behind his ear. Maedhros wished abruptly he hadn’t, so that Maedhros could do it for him, and considered what miserable chore he would assign himself to scrub that thought away. “I had so hoped it would be.” He flicked his eyes to the table, Maedhros still catching his breath. “I’m sure you will want to have someone clean that, though.”

Maedhros ground his teeth: Thingol knew he wouldn’t. Maedhros would not call anyone else to clean it for fear they would know exactly what it was; Maedhros would clean it himself, which Thingol had surely known when he made Maedhros do it.

There was a self-satisfied gleam in Thingol’s eye, an impudent smile on the edge of his lips, and Maedhros wanted to kiss it.

“It is my duty to clean up for my guest,” he replied. Thingol laughed.

“Once my host is done cleaning, perhaps he will pay me a visit. I must rest and change from the journey—” Not true, and they both knew it, he wasn’t the least bit tired, “—and I would welcome his company. Sheets of parchment and dreams are a poor replacement for reality.”

Maedhros arranged his expression and nodded, looking at the floor by the door as his heart leaped in his chest.

“I will of course, be a gracious host,” he answered carefully. “His Grace can count on my visit.”

“Wonderful.”

And it was.

#rocky writes#thingol#maedhros#thingdhros#maedhros x thingol#the silmarillion#tolkien tag#fanfiction#tolkien fanfiction#silmsmutweek#silmsmutweek2024

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Read The Silmarillion So You Don't Have To, Part Nine

Previous part.

Chapter 20: Of the Fifth Battle: Nirnaeth Arnoediad In which Maedhros tries and fails to get the Elves to play nice, and then a battle goes very badly.

This chapter begins with a quick account of what happened to Beren and Lúthien. They are restored to life, and briefly check in on Lúthien’s parents in Menegroth. It had been eternal winter in the forest of Doriath since Lúthien died, but Lúthien brings spring with her. When Melian sees her daughter, it’s like seeing a ghost. Melian feels the most horrible grief that anyone has ever felt in the history of the world, because Lúthien is mortal now. The Elves call Beren and Lúthien “The Dead that Live,” because there’s something deeply unnatural about coming back from the Halls of Mandos. All the Elves are unsettled by them, so Beren and Lúthien go off on their own, into the east of Beleriand. They have a son, Dior Aranel, but beyond that, the Elves never hear of them again. Presumably they live out their natural lives, but no one knows when they died or where they’re buried

That’s the end of that story! Now, let’s return to the Main Plot. Maedhros, the oldest of Fëanor’s sons (the one who lost a hand) has been thinking up new ways to fight Morgoth. Fingolfin proved that Morgoth is not invincible — he can be hurt, so maybe he can be killed, or at least incapacitated enough to stop causing trouble. However, the Noldor don’t stand a chance unless they can band together and fight Morgoth as a unified front. Maedhros tries to call all the Elves together in a council.

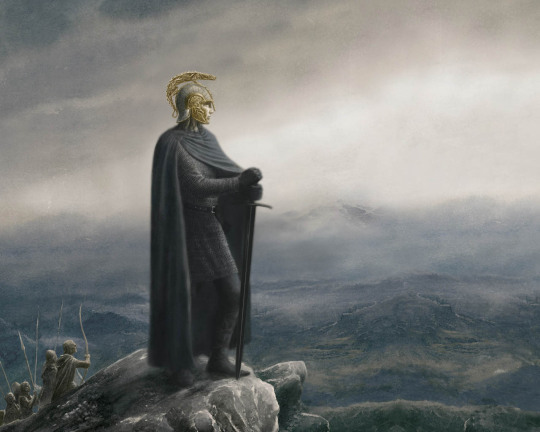

Maedhros by @kazz-art

(Fun fact: According to a YouTube video called “Types of Lord of the Rings Fans” by Generic Entertainment, “Maedhros” is composed of Sindarin words meaning “shapely” and “red-haired,” so it basically means “hot ginger.”)

Of course, the problem is that the Elves have never been unified, and they’re not about to start now. Fëanor’s sons (save Maedhros himself) hate basically everybody, and their shenanigans have burned too many bridges:

Orodreth is now king of Nargothrond after Finrod died, and he says that he’s never going to trust a son of Fëanor ever again. After Celegorm and Curufin’s attempted coup, who can blame him? A small group from Nargothrond, led by an Elf named Gwindor, come to aid Maedhros — but they go behind the king’s back.

Doriath is even more of a lost cause. King Thingol now has a Silmaril, and you know what that means — all of Fëanor’s sons (including Maedhros) are his enemies by default. Melian advises Thingol to surrender the Silmaril, just… y’know… to take that problem off their hands. But Thingol is offended by the Fëanorians’ arrogance, and he’s still very mad at Celegorm and Curufin for trying to steal his daughter. The Silmarils are also kind of like the One Ring, in that anyone who looks at them becomes obsessive and wants to keep them. So, instead of actually listening to his wife for once, Thingol sends the Fëanorians a note that says the Elvish equivalent of “come at me, bro.”

Maedhros carefully ignores Thingol’s threat, because he’s really trying to get everyone to work together. But those two assholes Celegorm and Curufin send Thingol a declaration of war. Thingol fortifies his kingdom and then just stays there, because his solution to everything is to isolate himself behind a magic wall and hope the danger doesn’t touch him. (That worked when Morgoth was a general threat to everybody, but not so much when other Elves want to kill Thingol specifically.) Thingol’s right-hand men, Mablung and Beleg, want no part in whatever shit is inevitably going to go down between Thingol and Fëanor’s sons. So, they’re given permission to leave Doriath (provided they don’t go to serve any of Fëanor’s sons). They go to Hithlum to serve Fingon, and then after that, no one enters or leaves Doriath.

(I know, I know, I already used it!)

But Maedhros has a few unexpected sources of help. He manages to enlist the Dwarves, who have lots of weapons and the means to make them, and he also has the Men on his side. All of them want Morgoth gone as much as anybody (and they haven’t been given any reason to hate Fëanor’s sons yet). Maedhros also has Fingon’s support, because Fingon still loves Maedhros as much as he did back when he rescued Maedhros from the cliff face.

The Night before Nirnaeth Arnoediad, by @pansen1802

The only faction that remains unaccounted for is Gondolin, because it’s the only kingdom that’s even more isolated than Doriath. News of Maedhros’ attempt at unity reaches Gondolin, but King Turgon still refuses to do anything.

Maedhros’ force is smaller than he’d hoped, but better than nothing. It’s enough to get rid of most of the Orcs in northern Beleriand, and it might be enough to try assaulting Angband yet again. Maybe this time it’ll work! Unfortunately, Morgoth knew they were coming. Before the battle even starts, Maedhros’ and co.’s chances are looking bleak. But at the last minute, the cavalry comes! Turgon finally decided to actually do something, and sent a host of ten thousand Elves from Gondolin to help. Fingon is overjoyed to have seen the first sign of his brother’s existence for centuries. He sends up a battle cry in Quenya. Morale is good! There’s a nice moment in which Fingon and Turgon briefly reunite on the battlefield.

The Battle of Unnumbered Tears, by Mysilvergreen

Unfortunately, it’s all downhill from there. This battle is called Nirnaeth Arnoediad, “the Battle of Unnumbered Tears,” so that should tell you everything you need to know. Fingon’s host retreats, the Men from the Forest of Brethil are nearly wiped out, and then there’s betrayal. This whole time, Morgoth had been trying to wage a psychological battle amongst the Elves and Men, sewing distrust amongst them and making it even harder for Maedhros to get them to come together. “Divide and conquer” has worked well in the past, and it works again here. A man named Ulfang and his sons suddenly turn against Maedhros. Maedhros’ host is cornered, and they’re forced to retreat.

The most steadfast fighting force in the battle turns out to be the Dwarves. If it weren’t for them, the Elves and Men would have been annihilated by Glaurung and the other dragons. A Dwarven lord named Azaghâl manages to stab Glaurung in the underbelly, which wounds him, but doesn’t kill him.

Finally, Gothmog, the Lord of Balrogs, comes out of Angband. He corners Fingon with another Balrog. Fingon fights valiantly, but no one can hold out against the Lord of Balrogs for long. Gothmog cuts Fingon in half with a greataxe. The Elves say that a white flame burst from Fingon’s helmet as it was cloven.

The Final Battle in Unnumbered Tears by breath-art

The battle’s basically over after that. Turgon holds out with the brothers Húrin and Huor to ensure that Morgoth doesn’t win the Pass of Sirion and take control of the river. Húrin tells Turgon to flee, because he’s the last hope for the Elves’ survival. But Turgon recognizes that by sending help, he revealed to Morgoth that Gondolin exists. It won’t take him long to find Gondolin and destroy it. Húrin tells Turgon that Gondolin will still be a beacon of hope for however long it continues to last, and says goodbye, knowing that they won’t see each other again.

Maeglin, Turgon’s nephew (the edgy Elf) is fighting nearby. He hears Húrin say that Gondolin is a beacon of hope, tucks it away in his mind, and says nothing. Ominous.

Turgon retreats, but the Men remain to hold the pass. Tolkien writes that, of all the deeds of Men that were performed for the sake of Elves, this is the most renowned. Some Men betray the Elves, but most of the Men continue to fight for them. Huor and all of the other Men die; Húrin is the last man standing. Húrin yells “Day shall come again!” every time he kills a monster, but the Orcs just keep coming, and they continue to fight him even after he cuts off their arms.

Exactly like this.

Eventually, Húrin is captured alive.

Morgoth is very pleased with himself for having engineered a betrayal. The Elves no longer completely trust the Men, except for the Three Houses that became their friends. Now that Fingon is dead, his realm of Hithlum is completely destroyed. The remaining Noldor of Hithlum (and there aren’t many) scatter, and join the Wood Elves of the East. Living in forests and using guerilla tactics are way less noble than having cities and fighting in armies. The Haladin, the Men of the Forest of Brethil, are also greatly reduced. They never see any member of their host again, or learn what happened to them. Morgoth shuts the treacherous Men in what’s left of Hithlum, forbidding them to leave it, which pisses them off because they wanted to rule Beleriand. Welp, that’s what you get for being a traitor.

One of the only safe places left in Beleriand is the Havens at the mouth of the River Sirion, but Morgoth is eventually able to ransack the Havens using machines with engines (remember, Tolkien thinks industrialization is evil). A handful of Elves, led by Círdan and Gil-galad, manage to escape by sea. They keep a foothold at the mouths of Sirion, but for the most part, Morgoth controls the river.

The situation is so dire that Turgon reaches out to Círdan from Gondolin. He wants to again try to send messengers across the sea to Valinor. Círdan builds ships and sends them west, but again, none of them return… except one. That ship turned back, and sank in a storm within sight of Middle-earth’s coast. One Elf from that ship survives, and he’s ferried to shore by Ulmo, the Vala of Water himself

Although Morgoth won decisively, he’s still not happy -- he wants to capture Turgon, and has no idea where he is. Turgon is the last remaining son of Fingolfin, and therefore the rightful High King of the Noldor. Morgoth’s hatred of the House of Fingolfin is personal, because Fingolfin wounded him, and because they’re friends with Ulmo the Vala. Morgoth also got bad vibes from Turgon all the way back in Valinor. He intuited that Turgon was destined to help destroy him.

Morgoth knows that Húrin is friends with Turgon, and Húrin is his prisoner. He demands that Húrin tell him where Turgon is, but Húrin tells him where he can stick it. In response, Morgoth binds Húrin to a chair on top of Thangorodrim, and curses him and all of his offspring. Morgoth tells Húrin that despair and sorrow will come to everyone he loves. To stick the knife in and twist it, Morgoth gives Húrin a taste of his own power to see the future, and forces him to remain sitting in that chair until all of his family have met their doom. Húrin does not beg for mercy for himself or any of his kin. He won’t give Morgoth the satisfaction.

Morgoth punishes Húrin by Ted Nasmith

As a final insult, Morgoth has the Orcs build a giant mount of bodies in the middle of the battlefield. The Elves call it the Hill of the Slain and the Hill of Tears. But after a while, grass and flowers grow on the bodies of the dead.

The Hill of the Slain by Ted Nasmith

Chapter 21: Of Túrin Turambar, Part 1. In which our angsty tragic hero tries to outrun his curse, kills people he shouldn’t, sleeps with people he shouldn’t, and fights a dragon.

This is the second of the Great Tales, also called “The Children of Húrin.” I’ve heard that this is one of the most tragic stories in the entire Tolkien Legendarium (which is saying a lot), so brace yourselves! This is going to be another two-parter, because I ran out of space.

Instead of jumping right into the story, Tolkien gives us an account of what happened to Húrin and Huor’s wives, Morwen and Rían. Rían is dead. Huor and Rían’s son is Tuor, and Húrin and Morwen’s son is Túrin. Húrin and Morwen also had a daughter, Lalaith, but she died of disease when she was three. After the battle, the Easterlings (evil Men working for Morgoth, they’re already called that) ransack Hithlum. They enslave everybody except Morwen, because she’s just so beautiful. They assume that she’s a witch, “in league with the Elves.” Despite their fear of her, Morwen decides that her son is not safe, and sends Túrin to Thingol. Morwen is Beren’s distant cousin, so she hopes that Thingol will take Túrin in. After Túrin is sent away, Morwen gives birth to a third child, a daughter named Nienor (which means “mourning.” That’s not ominous at all). Thingol accepts Túrin into his household, because he doesn’t hate Men as much as he used to, and raises him as his own son.

Germanic Fun Fact #1: It was actually a common practice in the early Middle Ages that noble children would be fostered by other families, and it shows up in fiction. For example, Beowulf was fostered by King Hrethel of the Geats, making him a de facto prince.

Túrin lives in Thingol’s court for nine years, and messengers occasionally bring him news of his mother and sister. One day, the messengers stop coming. Túrin puts on his ancestral family helmet, “the Dragon-helm of Dor-lómin,” and goes to battle alongside the king’s captains and the other Elves.

Túrin Turambar by Alan Lee

Túrin stays in the field for three more years, then returns to Menegroth. He looks dirty and unkempt because he’s been living in the wilderness for three years. One of the Elves of Thingol’s court, named Saeros, mocks Túrin for his wild appearance: “If this is what the Men look like, then do their women run like deer, wearing nothing but their hair?” In response, Túrin throws a goblet at Saeros, injuring him. The next day, they confront each other in the forest. Túrin defeats Saeros, and sends him running naked back to Menegroth, wearing nothing but his hair. Irony! As he flees, Saeros falls into a gorge and dies. Now Túrin is responsible for the death of one of Thingol’s courtiers. Oops.

Mablung, one of the king’s captains, advises Túrin to go back to Menegroth and beg Thingol for his pardon. Túrin decides to leave Doriath as an exile, but Thingol pardons him anyway.

He loved Túrin like a son, and would welcome him back if he decided to return. The king’s other captain, Beleg Cúthalion, loved Túrin just as much, and decides to go after him.

In the meantime, Túrin becomes the leader of a group of outlaws. And not the Robin Hood kind. He starts calling himself Neithan, which means “the Wronged.” (Thingol pardoned him, so he hasn’t been “wronged” at all. This is entirely his own fault.) After a year, Beleg finally finds Túrin’s outlaw lair. Túrin didn’t happen to be there at that moment, so the other thugs seized and bound Beleg, assuming that he was a spy from Thingol. When Túrin gets back, the sight of Beleg bound in his lair makes him suddenly repent of all his evil deeds, yada yada, and he swears to never again harm anyone besides Morgoth’s minions. Let's see if that promise lasts more than five minutes.

Beleg tries to convince Túrin to return to Doriath. He’s been pardoned, so he has no reason to hide out in the wilderness. Túrin is too proud to come crawling back, though. He tries to get Beleg to stay with him, but Beleg is tired of his nonsense and tells Túrin to find him on the front lines if he really wants to be with him. They go their separate ways. Túrin heads out towards Amon Rûdh (“Bald Hill”), a large hill overlooking the Forest of Brethil

Beleg returns to Menegroth and tells Thingol everything that happened (except for the part where he was tied up by Túrin’s thugs). Thingol just sighs and says, “What more would Túrin have me do?” Túrin is a hotheaded teenager who ran away from home, leaving his adoptive parents exasperated. Beleg offers to follow Túrin and protect him from a distance. Thingol gives him leave to go, and as a reward for his service, offers him anything he wants. Beleg asks for a fine sword. The king offers him any sword in his armory, save his own. Beleg chooses a sword called Anglachel, made from a meteorite. (Space Sword!) That means that its blade is ominously jet-black. It’s one of two swords made from the same meteorite by Ëol, the Elf of the Dark Forest. (Remember him? He was Aradhel’s abusive husband, and followed her to Gondolin, where he was killed by being thrown from its walls.) Thingol got one of the meteorite swords as payment for letting Ëol live on his land. Ëol’s son Maeglin has the other one.

Anglachel by Elena Kukanova (Thingol is portrayed with blonde hair here.)

As Thingol presents Beleg with the sword, Queen Melian stops to say that the sword “has malice in it.” If you haven’t noticed by now, any work of craftsmanship in Tolkien’s world is imbued, to at least some extent, with the personality of its creator — the One Ring, the Silmarils, the swan ships, and the Two Trees themselves. This sword is no exception. It absorbed all the bad vibes from Ëol. Melian says that it will serve Beleg begrudgingly, and he’ll end up losing it.

In light of that, Melian decides to give Beleg another gift: lembas bread. In the First Age, Melian was the only person with the authority to give out lembas. The leaves it’s wrapped in are marked with her seal, a white flower of Telperion (the Silver Tree). Melian gives Beleg the lembas with the expectation that he will share it with Túrin, which is a big deal — it’s the first of the very few times that Elves have ever shared their waybread with Men. Beleg leaves with the gifts, and spends the winter keeping the Orc population in check. Once spring comes, and the Orcs are no longer an immediate threat, he goes off to find Túrin.

Germanic fun fact #2: Waybread (wegbræde) is actually the Old English name of a broadleaf plantain, a type of edible plant. Tolkien decided to make it into literal bread.

Meanwhile, Túrin and his gang come across three Dwarves. They capture one of them, and one of the Men, Andróg, shoots after the other two. The arrow goes into the dark, and the Men can’t see if it hit or not. The captured Dwarf’s name is Mîm, and he offers to show Túrin his secret cave in exchange for his life. Túrin pities him, and spares him. (Túrin kind of swings back and forth between doing evil things and then regretting it.) Mîm leads the Men up the slope of Amon Rûdh to his secret cave, which “will be” called the House of Ransom. There are red flowers all over the hill, and one of the Men remarks that it looks like there’s blood on the hilltop. That may as well be a massive ‘FORESHADOWING’ sign.

Mîm the Dwarf by Anke Eißmann

Inside the House of Ransom, Mîm shows the Men the body of his son Khîm (Dwarves really like rhyming names), who was shot and killed a few minutes ago. The arrow that Andróg shot into the dark killed Mîm’s son. Oops. What a way to guilt-trip the Men. Túrin feels horrible (you’d think after Saeros he’d learn not to be so reckless). He takes responsibility for Andróg’s arrow, and offers to pay Mîm a ransom of gold for his son. That validates the name of the House.

Germanic fun fact #3: A ransom paid as compensation for someone’s life is called weregild. This was a normal part of life in Germanic cultures. It was a way of preventing endless back-and-forth feuding between families. The gold guarded by the dragon Fafnir in Germanic mythology is weregild that the Norse gods themselves paid to a Dwarf for the murder of his son. (That story shows up in the Prose Edda and the Volsung Saga, parts of it are also in the Poetic Edda, and it’s referenced elsewhere.) Tolkien is definitely referencing that story here.

Mîm is impressed by Túrin’s speech, remarking that he sounds like an ancient dwarf lord, and forgives him to a point, saying that he doesn’t need to pay a ransom after all. He lets Túrin and co. stay in his house for as long as they need.

Now for a little bit of Dwarf history (we’ve had a lot of Elf history, so we need some Dwarf history): The Dwarves that live in the House of Ransom are called “Petty-Dwarves,” which means they’re less cool than other Dwarves. They were banished from the old Dwarf kingdoms in the Misty Mountains, and made their way west to Beleriand. They’ve slowly become shorter and less talented smiths, and they live in secrecy, which Tolkien thinks is ignoble. The Elves used to hunt them for sport, until the other groups of Dwarves showed up. So, the Petty-Dwarves hate Elves even more than they hate Orcs, and they especially hate the Noldor. The Petty-Dwarves originally discovered the caves of Nargothrond before Finrod took it over and forced them out. By now, the Petty-Dwarves have dwindled and basically lost all relevance. Mîm is one of the last and one of the oldest ones left.

In the harsh cold of winter, a hulking man arrives at Amon Rûdh. The Men all spring up to fight, but the man turns out to be Beleg Cúthalion. He only appeared to be a hulking brute because he was wearing a big backpack under his cloak. Beleg and Túrin have a heartwarming reunion, and Beleg gives Túrin his old ancestral treasure, the Dragon-helm of Dor-lómion. Beleg hopes that the helm will remind Túrin that he’s better than this, that he could be something more than an outlaw living in a hole. But it doesn’t sway Túrin at all.

The Dragon-helm of Dor-lómin by Elena Kukanova (This artist’s design of the helm is based on a real Anglo-Saxon helm found at Sutton Hoo.)

Against his better judgement, Beleg stays with Túrin, purely out of love for him. He becomes the team medic, and uses the lembas that Melian gave him to heal sick and injured members of Túrin’s company. (Lembas apparently has healing powers at this point in Elven history.) Mîm the Dwarf is not happy about having an Elf living in his House. Men are one thing, but as I said before, the Petty-Dwarves have every reason to hate Elves.

Meanwhile, Morgoth is still a problem. Túrin and Beleg go out hunting Orcs, and they’re so good at it that they become living legends. Their land becomes known as “The Land of the Bow and Helm,” referring to Beleg’s archery skills and Túrin’s fancy Dragon-helm. Túrin starts calling himself Gorthol (“Dread Helm”), which is a little pretentious. Even the isolated Gondolin has heard of them! Of course, Morgoth eventually hears of them too, and he immediately knows who the fearsome “Dread Helm” is — it’s that upstart kid from the cursed bloodline! He starts laughing, and presumably sits back with his popcorn to watch the shitshow.

Mîm and his son Ibun are promptly captured by Orcs when they go out to forage for the winter. Mîm uses the exact same tactic that he pulled when Túrin and co. captured him — he promises to lead the Orcs to his secret cave, selling out Túrin to the Orcs. To his credit, Mîm does make the Orcs promise not to kill Túrin, but that doesn’t make much of a difference.

The Orcs kill most of Túrin’s company in their sleep. The rest flee to the top of the hill, but most of them are run down and slain, so that their blood covers the top of the hill like the flowers did. The Orcs actually keep their promise not to kill Túrin, and drag him away. Mîm returns to his House to find a massacre, which he’s not too torn up about, because he’s finally rid of the squatters. Everyone’s dead except for Beleg, who is badly wounded on top of the hill. Mîm takes Beleg’s cursed sword and tries to kill him, but Beleg has enough strength left to catch the sword and push it back. Mîm runs like a coward, and Beleg calls after him that Túrin will one day have his vengeance.

Beleg is a strong Elf who knows healing magic, so he slowly recovers. He searches among the corpses for Túrin’s body, hoping to bury him. When he doesn’t find it, Beleg realizes that Túrin is alive, and goes out to look for him a third time. You’ve gotta admire his devotion to this kid who’s a magnet for trouble.

Beleg by kimberly80

Beleg follows the Orcs’ trail all the way to Taur-nu-Fuin, the Forest under Nightshade in the north near Angband. It’s a dark and scary place, but Beleg is such a badass that he can survive it. In the forest, he finds an Elf sleeping under a tree. After Beleg heals him and gives him some lembas, the Elf says that his name is Gwindor, one of the Elves from Nargothrond who went to fight with Maedhros in the Battle of Unnumbered Tears. Captured Noldor are put to work in Morgoth’s mines, since they’re skilled with metals and gemstones. (The Noldor yearn for the mines!!!) Gwindor managed to escape through a secret tunnel, and got lost in the evil forest.

Gwindor gives Beleg some intel about the Orc party he’s chasing, and tries to dissuade Beleg from following them. After all, he knows what awaits them in Angband if they get captured. But Beleg refuses to abandon Túrin, and Gwindor, having finally gotten a smidge of hope, decides to go with him.

Beleg and Gwindor sneak into the Orc camp at the base of the Thangorodrim and carry Túrin out without a hitch. But when Beleg goes to cut Túrin’s bonds with his cursed sword, he slips and snicks Túrin’s foot with the blade. Túrin wakes up to see someone bending over him with a sword, and freaks out, not realizing who it is. He grabs the sword and kills Beleg, his loyal friend who loved him so much that he repeatedly put himself in harm’s way for Túrin’s sake. A storm rages overhead, and a flash of lightning illuminates Beleg’s face. Túrin is completely distraught to see that he killed his friend, and collapses beside Beleg’s body.

Death of Beleg by Elena Kukanova

In the morning, when the storm passes, Gwindor suggests that they bury Beleg. Túrin is still distraught, but helps bury him right in that spot. They bury Beleg’s bow with him, but take the lembas, and the meteorite sword. Gwindor thinks it’s a shame that such a fine sword should go to waste, and thinks it would be better used to kill the Orcs, and that’ll definitely come back to bite them later.

They go off together, but Túrin is so traumatized that he doesn’t speak. Gwindor looks after him until they reach a magic spring called Eithel Ivrin, which is blessed by Ulmo (the Vala of Water). Túrin drinks from the spring and finally speaks again. He composes a lay to honor Beleg’s life, and sings it at the top of his voice.

Túrin and Gwindor at the Pools of Ivrin, by Ted Nasmith

Gwindor gives Túrin the meteorite sword, and offers to take him back to Nargothrond. Since he can finally speak, Túrin asks Gwindor who he is, and Gwindor tells him that he’s a thrall who was “once” Gwindor son of Guilin. I think it’s interesting that Gwindor introduces himself this way — he no longer feels worthy of his former identity, and though he escaped Morgoth, he still identifies himself as a “thrall.”

Túrin also asks after his father Húrin. Gwindor doesn’t know any details, but he tells Túrin the rumors that Húrin is imprisoned by Morgoth and that his line is cursed. After everything that just happened, Túrin finds that completely believable.

As they continue to travel, Túrin and Gwindor are captured by Gwindor’s own people, the Elves of Nargothrond. They don’t recognize Gwindor at all — being a slave in Angband aged him prematurely, which doesn’t normally happen to Elves — so they assume that Gwindor and Túrin are spies. The first person to recognize Gwindor is the king’s beautiful daughter, Finduilas, because she was in love with him before he left. Gwindor is welcomed back into the fold. Túrin is allowed to stay, but he doesn’t give the Elves his real name.

Something about Túrin must be really appealing to Elves, because the Nargothrond Elves like him as much as Thingol’s Elves did. Also, Túrin has been a teenager this whole time, and only now does he reach manhood. (Actually, like Aragorn, he’s probably significantly longer-lived than the humans of today are. But still.)

Also, he’s really attractive, like his mother Morwen— he has pale skin and dark hair, gray eyes, and the prettiest face of any Man who’s ever lived. At first glance, you’d easily mistake him for one of the Noldor. (After all the pictures of him looking kind of like Aragorn or Boromir, that came as quite a shock.) I guess he cleans up nicely; he has been living in the wilderness for years.

Túrin Turambar by @tolrone

The meteorite sword is reforged, and Túrin renames it Gurthang, “Iron of Death.” He’s so skilled with it that the Elves nickname him Mormegil, “The Black Sword,” which is pretty badass.

Finduilas unwittingly falls in love with Túrin, and out of love with Gwindor. Gwindor catches on, and doesn’t take it personally, but he warns Finduilas about what happened the last time an Elf and a Man fell in love. Túrin may look and act like an Elf, but he’s not one — he’ll die and leave Finduilas alone, and it’s vanishingly unlikely that Mandos will be willing to break the rules a second time. Also, Túrin is clearly cursed, and Beren didn’t have that problem. Gwindor also reveals Túrin’s real name, and tells Finduilas that if she gets mixed up with him, she’s guaranteed to feel the effects of the curse on his bloodline.

Nargothrond. Finduilas and Túrin by Elena Kukanova

Túrin is very mad that Gwindor revealed his true identity. Gwindor tells him that he’ll attract trouble no matter what he calls himself, so, there’s not much point in using aliases.

When Orodreth, the king, hears who Túrin really is, he’s perfectly happy to have a son of Húrin in his ranks. Túrin becomes more and more important in his court — so important, that he can completely overhaul their method of warfare. Remember, ever since Celegorm and Curufin’s attempted coup, the Nargothrond Elves have practiced mainly guerilla warfare, which is sneaky and dishonorable and all that. So now, because of Túrin, the Nargothrond Elves practice open warfare like civilized people. The disadvantage to this is that, now that the Nargothrond Elves are fighting out in the open, Morgoth knows where they are.

Gwindor is worried by how much influence Túrin has, and sounds the alarm, but no one listens to him anymore and he falls out of favor. Poor guy. He survives Angband, is nice to Túrin, gives him a place to live, and is repaid by Túrin stealing his honors and his girlfriend.

In the meantime Morwen, Túrin’s mother, takes advantage of the unexpected peace caused by her son’s decimation of all the Orcs in the area. She flees to Doriath with her daughter, expecting to find Túrin there. She grieves when she learns that Thingol’s court hasn’t heard from Túrin in years. (They actually have heard of “The Black Sword of Nargothrond,” but they have no way to know that it’s Túrin.) Thingol allows Morwen and her daughter to live in his court, and treats them like family.

Okay, I’m gonna stop there! More coming!

#the silmarillion#the silm#the silm fandom#the silm art#summary#tolkien#jrr tolkien#turin turambar#children of hurin#tragedy#beleg cuthalion#beleg#gwindor#finduilas#nargothrond#maedhros#battle of unnumbered tears#nirnaeth arnoediad#fingon#morgoth#hurin#nienor#germanic mythology#j.r.r. tolkien#middle earth#long post

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Legendarium by Pete Amachree

Oromë leading his forces during The War of Wrath

Beleg is presented with the sword, Anglachel

Númenórean shrine to Yavanna, before the arrival of Sauron

Húrin's last stand at Nírnaeth Arnoediad

Melian the Maia and her daughter Lúthien, in the throne room of Menegroth

Húrin finds the Nauglamír, in the ruins of Nargothrond

Luthien sends the court of Morgoth to sleep with a song of enchantment

Fingolfin challenges Morgoth at the Gates of Angband

City of the Gondolindrim

Gondolin: The House of the Golden Flower

Daeron at the court of Menegroth

Assault on Nargothrond

Ruins of Doriath

Beren and Luthien flee Angband

Two Valaraukar, or Balrogs at Nírnaeth Arnoediad

Húrin returns to Morwen

Fëanor's last stand at Dagor-nuin-Giliath

The Catacombs of Menegroth

The Halls of Mandos

Númenórean shrine to Yavanna Kementari

Melkor and Sauron

#tolkien#jrrt#jrrtolkien#jrr tolkien#silmariilion#the silmarillion#valar#valinor#orome#yavanna#beleg#valier#anglachel#numenor#sauron#the lord of the rings#lord of the rings#lotr#melkor#elves#hurin#melian#luthien#beren#balrogs#the hobbit#hobbit#fingolfin#angband#morwen

370 notes

·

View notes

Text

[spins the Silm Headcanons Nobody Else Shares (Yet) wheel]

Though Elrond was, inevitably, involved in the politics of building Lindon, he was not only NOT Gil-Galad’s official herald yet at the start of the Second Age, but he was only tangentially involved with the new government. Instead, Elrond spent the first few centuries of the Second Age as an adventuring anthropologist/archeologist.

He traveled around Lindon, and inland and up and down the shore, talking to all variety of refugees and recording the histories and cultures of their people, from ancient myths to recent war stories to how this group of Men (or Elves or Dwarves) cooks their porridge vs how that one does. He dug and sometimes dove into ruins of forts rent by Light and Shadow, often with foul lingering malaise, to retrieve papers and goods warped by flame, sea, and worse.

Because Elrond’s childhood was filled with many refrains of loss, and one was,

“This is how we baked nutcakes in Menegroth!” his mother explained, hands sticky with chestnuts and honey. Under her breath, not meaning her even stickier sons to hear, she added, “I think.”

“Oh yes, there were…” Eärendil’s fingers twitched as he counted in his head. “…eleven different major fountains in Gondolin! One for each Great House, though all were managed by Lord Ecthelion—oh, no, but then that must be ten…?”

“Now, in a proper course of musical education, I would be starting you on basic dancing songs today. But Filúriel is the only one of us left who knows how to dance a good gavotte—”

“Filúriel died three years ago. Orcs on the way back from Sirion.” Maedhros didn’t look up from the daggers he was sharpening. Only his words gave any indication that he was even aware of the lesson taking place across the room.

“—But there is no one left who knows how to dance a good Tirion Gavotte.” Maglor never missed a beat. “So instead I will start you on basic Songs for striking fear into the hearts of your enemies. Have you both done your warm-up exercises today?”

[smash cut to 200 years later]

Elrond: Are you telling me. That there is a chance. That a portion of the Great Library of Thargelion, greatest collection in Beleriand of books and art brought physically from Aman, is still intact?

Random improbably still alive Nargothrond-Fëanorian #6: If the cases were water-proof as well as orc-proof and fire-proof…if they were orc-proof and fire-proof at all…especially dragonfire-proof…or dragon-ice-proof… If they stayed hidden, if we even shut them all properly in the first place, as we evacuated just ahead of the— my lord, where are you going?!

Elrond, sprinting past them down the corridor: Deep-sea diving!

(In the late Third Age, the Library of Rivendell is widely regarded as Arda’s single greatest repository of historical records of life in Middle Earth. This is incorrect—the single greatest such repository is an ever-growing library on Tol Eressëa, to which Elrond spent 3000 years sending copies of everything from Hobbit almanacs to Dwarvish epic poems to account books from three Elvish kingdoms to an Age’s worth of Dúnedain Ranger journals. Anyone Sailing with extra cargo space has been cajoled into taking at least a few tomes. People and places may be lost to time, but part of why he chose an Elvish life is so that they will not be forgotten.)

452 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on Galadriel.

To be honest, I do not think the Noldor who lived in Beleriand and ME after the war liked Galadriel much. (I love Galadriel and loved what Cate Blanchett as her in the movies) But like thinking about the Noldor of Beleriand, excluding those who lived in Gondolin and Nargothrond before both kingdoms fell, Galadriel basically abandoned the Noldor the moment she set foot in Beleriand. She went to Menegroth and stayed there under the protection of Melian for the most part of the first age, all while the rest of the Noldor, her brothers included, were out in the frontlines of war.

Even during the long peace, most of the Noldor in Beleriand had to see orcs attacks and such, their homes were not 100% safe, they didn't have the luxury of being protected by a Maia. The Valar had more or less abandoned the people of Beleriand (not just the Noldor) to their fates. So while the people who lived in Barad Eithel, Dorthonion, Ladros, Himlad, who were basically the ones holding the siege, all those people who died during the fire. Who had to move further south. Those elves could see Fingon, Fingolfin, Angrod, Aegnor, and the Feanorians willing to protect their people and die for them. (and I bet Aredhel would have been there too if she hadn't been kidnapped by Eol but that's another thing). But like Galadriel once she stepped in Doriath she never left until she felt considerably threatened and when she did, she and Celeborn moved east beyond the blue mountains. She wasn't even there when the war of wrath really broke out. Like right now I don't really remember if she managed to see the host of valinor and when the war was done and she did come back to the coast... she was denied passage.

Galadriel couldn't go back to Valinor by the end of the first age because I remember reading that she was denied passage, because she was not humble. The Galadriel we see in LOtR is an older and wiser Galadriel that had perhaps realized that most of her actions in the first age were born of hypocrisy (Hipocrisy was a big theme in the first age but that's also another story).

So what I want to get at is, Galadriel was not named queen of the Noldor and was not included in Noldori Politics at all during the second age (looking at you Amazon), because I don't think the Noldor considered one of them anymore. I think that the moment she decided to marry a sinda and remain in menegroth with the rest of Thingol's people she was 'set aside' by the Noldor as a whole. So yeah, those are my thoughts regarding Galadriel, if anyone else wants to add anything else, I'll be more than happy to read your thoughts <3

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

refugees do not, in fact, stop being refugees because you don’t like their leaders

#notes from management#‘the only refugees thingol kept out were CELEGORM and CURUFIN’ i was not aware the feanorian presence in himlad consisted of two elves#and given those people later show up in nargothrond i feel secure in saying they weren’t allowed into doriath either#‘but they were KINSLAYERS’ really? every last one of them?#every washerwoman and orphaned child and random band of humans hitching a ride away from the front lines?#and even so… we know these people aren’t mindless feanorian loyalists on account of (again) nargothrond#they’re not monsters (yet) or even really an active threat#but no can’t have any hint of the *~pollution~* of the outside world within the girdle#there is no war in menegroth etc etc#:sigh: as a die-hard feanorian stan who nevertheless thinks they do end up as villains#i just wish the thingol people would acknowledge that he maybe made some bad decisions

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

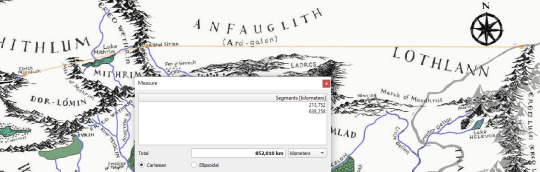

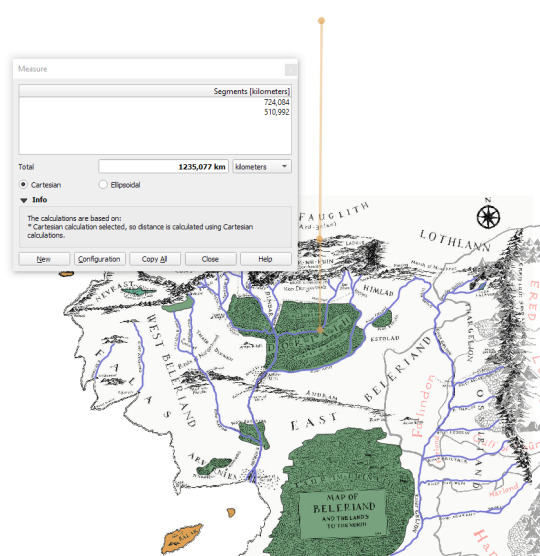

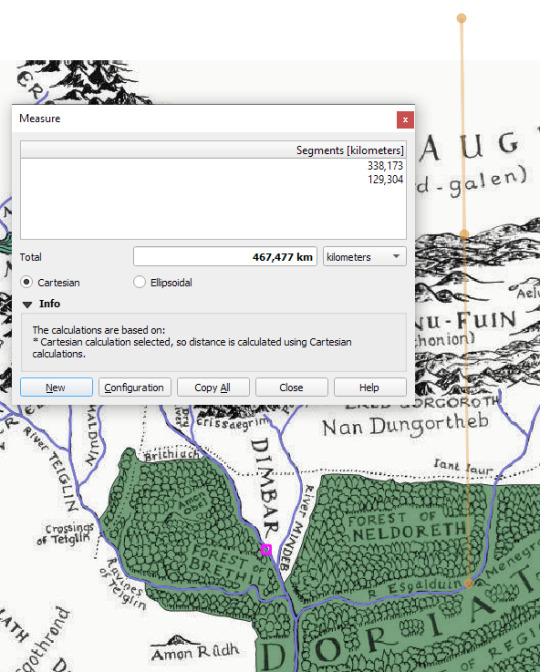

Hello my saint Mapmaker! That Beleriand GIS map is everything to me right now. I find myself in Beleriand distance hell and this is like a fruit from the gods.

Please, if I can ask further: * What would be the distance across Hithlum from Eithel Sirion to Cirith Niniach? * Estimations on the length and width of Ard-galen/Anfauglith (let's say between Ered Wethrin to the Blue Mountains, and then Dorthonion to Thangorodrim)?

I don't know anything about handling geopackages but if you have tips I'd love to have it so I don't pester you infinitely with asks 😅

Hi! I'm so glad you find this useful! I don't know why I've never thought about this before, it seems so obvious now :D

in a straight line, the distance between Cirith Ninniach and Eithel Sirion is approximately 214 km or ~133 miles, and Eithel Sirion–Blue Mountains is about 638 km / 397 miles.

I will try and georeference the map from War of the Jewels tomorrow, then I can tell you about the north–south extents. I can NOT take the line in the Silm seriously that says "the gates of Morgoth were but (sic!) one hundred and fifty leagues distant from the bridge of Menegroth". On the map that looks absolutely ridiculous XD the Anfauglith would be as large as the rest of Beleriand!

Christopher writes in HoMe5, "according to the scale of the second Map […] the distance [Menegroth–Thangorodrim] was scarcely more than seventy [leagues]". That would mean Dorthonion is about 80 miles / 130 km wide.

You can pester me all you want :D but If you're interested I could put together a very basic tutorial on how to load a geopackage into QGIS and measure basic stuff, it's not very hard and QGIS is free :)

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summary - Who Is and Isn’t Allowed Into Doriath