#the word for germans in pretty much every slavic language is basically

Text

>think of a pre-christian Slavic rewrite of Warrior Cats for fun

>needs new terminology

>most stuff is easy and works pretty well, camps can be hradiště instead, cardinal directions can be called after daytime like in Polish, easy

>try to think of what would they call other fellow predators who are on the same "level" as them but impossible to understand due to being different species, such as other felines or foxes

>get slapped with the realization that fantasy kitties would call other animals "Germans"

#cause#the word for germans in pretty much every slavic language is basically#''mute ones'' or ''those who can't speak (our language)''#crying#the ups and downs of your language having very literal terms for things#warrior cats#xenomoggy#< that's the tag for warrior cats-adjacent xenofiction right

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Slasher OC: Decebal Avram Chirilă

Full Name: Decebal Avram Chirilă

Nickname(s): Dacia, Dece, The Impaler, Vladislav, Tiger, Lynx, Dracula, Casanova

Age: 38

Gender: Male

Nationality: Romanian

Place of Birth: Bucharest, Romania

Current Location: Travels from country to country

Occupation: Former Romanian Soldier; Now Hitman

Languages: Romanian, English, German, French, Italian, Hungarian, Russian, Turkish

Appearance:

Height: 6'8

Weight: 240lbs

Body Type: Middle Bulky and Atheltic

Skin Color: Warm Beige

Hair Color: Dark Brown

Hair Style: Short on the sides and longer on top, wavy

Eye Color: Pale Grey, almost white, giving the impression he is blind

Face Claim: Stephen James

Clothing: He opts for comfortable clothing mostly because of his job as a hitman and because he is always on the run. He mostly goes with black T-shirts or shirts, a khaki army coat with many pockets, along with camo army pants again with many pockets and black combat boots. He has a long black scarf with the colors of the Romanian flag trimmed along that belonged to his father.

Other features: He has many scars on his broad back and down his arms; his back's scars are covered by tattoos of an eagle and a grim reaper with two swords in an X shape. His has full sleeve tattoos down his arms, picturing all kind of nature scenarios from his country, mountains and wild animals and AK-47's on each forearm. His neck, chest and legs are also covered by tattoos along with his hands. This guy is all inked up. He also has a silver earing on his right ear. He also wears an eyepatch that is covering his scarred eye that he got from a fight with his brother Alexander, the scar mimiking the ones Alexander has, coming from his eyebrow down his eye and over his cheek.

Weapons: Twin Swords, Twin Guns, and throwing knives.

Power/Skills:

Murderous expertise

Brute strength

Skilled usage of weaponry

Skill in hand-to-hand combat

Knifesmanship

Swordsmanship

Multilingual

Cunning Nature

Charisma

Driving expertise

Ruthlessness

Fearlessness

Manipulation

Marksmanship

Master tactician and strategist

Stealth mastery

Symbols: Here is the link to Decebal's symbols

History/Bio:

Decebal was named after a Romanian king by his parents, father Apostol Chirilă, and his mother, Maria Stratulat of Moldovic heritage. They were a poor family that lived in Bucharest during the communist times, a hard period for them. Decebal's father, Apostol was one of the rebels that were against this form of a system of social organization in which all property is owned by the community and each person contributes and receives according to their ability and needs.

Because of this Apostol and Maria, along with their three years old son, Decebal, were dragged into the communistic jails where they were tortured in all kinds of ways from whipping to starvation to being chained into coldness.

Decebal tried to protect his parents even though he was a small child and the army warden that took care of the horrific jails was surprised by the child's braveness and he took him away from his parents, not before forcing him to watch how his parents were killed brutally.

During the rest of his childhood and teenage years, Decebal spent most of his life in the dark underground jail, training with the soldiers, doing hard work. Despite that, the warden thought Decebal about all kinds of languages, cultures, and history.

'Just because you're a stray dog that doesn't mean you cannot learn to bark and bite.'

In his late teenage years as he grew into an adult man, he got more to the light outside, following the warden wherever he went and did was his so-called 'father' figure did; smoke, drink and got laid with all the ladies.

The warden's words during a drunken late-night:

'You know boy, you will do something big, much bigger than you can imagine. I saw how all these sluts looked at you... You make them fall into your arms like they are desperate whores.'

'Use everything you got; charms, brains, muscles. In this world, there are the ones that walk every inch of the ground as they own it and the ones that follow, all chained. Tell me, boy... Which one you are?'

One of the greatest abilities that Decebal earned during years in the darkness was that he got so used to it that now as an adult, he sees perfectly into the darkness, just like cats do.

Some people called Decebal 'Lynx'; the moniker originates from the fact that Lynx has exceptional night vision, remarkable hearing, and incredible instincts. The spiritual lesson Lynx carries to you is a reminder to partake of quiet observance, remembering there’s more to the world than what’s accessible through the physical eyes and ears alone.

After communism fell down in Romania, Decebal still maintained the attitude he grew up around; being sadistic, cold, and cruel. People weren't too fond of his attitude; his habits including fighting and torturing people that opposed him, getting laid with other men's wives, strolling down the streets like he owned everything.

He disappeared from Romania when there was a reward on his head to be finally executed. The Romanian army was hot on his trail, turning against him, but he simply vanished.

He strolls from country to country, not having a definitive home and working as a rogue hitman to earn money and to survive.

After a brutal fight between him and his twin little brother, Alexander; the two brothers which resulted in both of them almost dead, they get on an agreement of peace between them, with the help of their third part, their little sister Nadia.

Family: His little brother Alexander Chirilă and his little sister Nadia Nikolina Chirilă

His favorite killing style:

He prefers a kill that will put on a good show, he will shot his victims in both their knees, then he will dismember them with his sharp twin swords.

Personality:

Decebal has two paths of personality; the civilian one and the hitman one, that sometimes cross path depending on the situation at hand. In hi day to day life, he is a charming, handsome man, confident and sure of himself, but also having a modesty edge, just to draw people in closer, because he loves the attention, having a God-like complex.

Despite his childhood, he is a very educated man that speaks many languages, sometimes taking people by surprise, he can even put on fake accents. He also has vast knowledge about other countries history, mostly because that's what his 'father-figure' talked a lot about.

He is a flirt, he simply adores to make women swon by his charming looks and mysterious persona wherever he goes, people always wondering from where he comes. He knows how to sweet-talk people, being extremly manipulative. His looks; big and strong, in his eyes a flaming white glow.

You will rarely see Decebal without his charming smile or dark smirk that makes the ladies sigh and faint. He always puts on a winning attitude, knowing for creating many divorces along his travelings.

Here goes his saying: 'If the female raised her tail, who I am to deny.'

He has a romantic side, after all he does speaks the romance languages, but it's highly influenced his his Casanova attitude.

He is blunt; this man will tell if you're damn gorgeous or if you're down-right ugly or stupid. He has no problem putting his opinions straight on the table.

His favorite drink: Țuică- is a traditional Romanian spirit that contains ~ 24–65% alcohol by volume (usually 40–55%), prepared only from plums.

His favorite food: Sarma is a dish of vine, cabbage, monk's rhubarb, kale or chard leaves rolled around a filling of grains, like bulgur or rice, minced meat, or both. It is found in the cuisines of the former Ottoman Empire from the Middle East to Southeastern Europe.

His scent: Decebal's scent could be described as a 'game of seduction' with an "exciting rush" of citrus and cool spice top notes. Pungent bergamot "bites" with freshness, revived by cardamom and lavender. Caviar gives a provocative and erotic touch “like a trickle of sweat on a man’s chiseled body.” Masculine and rough notes of tobacco and orris root facilitate the heat of the composition. He has that scent that could be described as smoky confidence irresistible to women.

Other Characteristics:

He is a very good dancer, especially traditional ones and he also knows singing. Attending important parties with his 'father-figure' he learned from the women how to dance and sing. The women basically made him such a charismatic man.

He is a heavy drinker and holds his alcohol like it's water; his moldovic genes showing off.

He is more of a night person that a day one, mostly because of his very good nocturnal sight.

He is pretty much an Outlaw.

His accent sounds like italian, latin, but with a little bit of russian or another slavic accent. (That's how a Austrian woman described his accent one night)

He is a master at Poker. Another way he earns a lot of money is through poker and plus, he is a master cheater. FUN FACT HERE: He won a man's wife through poker for one night.

He is a sword swallower, bonus he has no gag reflex.

He also loves to smoke from his pipe.

============================================

There lived a certain man in Romania long ago

He was big and strong, in his eyes a flaming glow

Most people look at him with terror and with fear

But to Bucharest chicks he was such a lovely dear

He could preach the Bible like a preacher

Full of ecstasy and fire

But he also was the kind of teacher

Women would desire

DE DE DECEBAL

Lover of the ROMANIAN queen

There was a cat that really was gone

DE DE DECEBAL

Romania's greatest love machine

It was a shame how he carried on

He ruled the Romanian land and never mind the Tsar

But the kazachok he danced really wunderbar

In all affairs of state he was the man to please

But he was real great when he had a girl to squeeze

For the queen he was no wheeler dealer

Though she'd heard the things he'd done

She believed he was a holy healer

Who would heal her son

DE DE DECEBAL

Lover of the Romanian queen

There was a cat that really was gone

DE DE DECEBAL

Romania's greatest love machine

It was a shame how he carried on

(This is an interpretation of the song ‘Rasputin’ by Boney M, mostly because the song inspired me into creating him)

For power became known to more and more people

The demands to do something about this outrageous

Man became louder and louder

"This man's just got to go!" declared his enemies

But the ladies begged "Don't you try to do it, please"

No doubt this Decebal had lots of hidden charms

Though he was a brute they just fell into his arms

Then one night some men of higher standing

Set a trap, they're not to blame

"Come to visit us" they kept demanding

And he really came

DE DE DECEBAL

Lover of the Romanian queen

They put some poison into his țuică

DE DE DECEBAL

Romania's greatest love machine

He drank it all and said "I feel fine"

DE DE DECEBAL

Lover of the Romanian queen

They didn't quit, they wanted his head

DE DE DECEBAL

Romania's greatest love machine

[Spoken:] Oh, those Romanians...

=======================================================

But when his drinking and lusting and his hunger

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Making the Draenei Language - Part 2

Part 1 | Part 3

First off, thanks to all the people who’ve expressed interest in this project! It makes me super happy that people think what I’m doing is interesting :D

Anyway, last time I went through and got a basic idea of the structure of the language, this time we’re diving into WHAT 👏 THAT👏 MOUTH👏 DO (and also spelling)

... and by that I of course mean phonetics (the study of the sounds produced in speech), phonology (the study of which sounds differentiate meaning) and phonotactics (how sounds are put together).

Phonetics and Phonology

Before we can even consider choosing some sounds for the language lets take a moment to consider those TEEF!

Taking my main boy Aegagrus (drawn by the wonderful @rurukatt, definitely didn’t put this in here cuz I still love this pic) as a model for my headcanon of Draenei teeth, we can see how those might get in the way of some sounds... but just like, specifically [f] and [v] (sounds in square brackets represent sounds not the letters, to hear what they sound like go here!) Both of those sounds involve making the same shape with your mouth - touching your bottom lip to your top teeth, but when you got some real long or pointy teeth, that might be a little bit hard to do! (or an accident waiting to happen if they’re sharp enough)

There’s only a small problem with this though, we have some canon words that use these sounds e.g “Pheta vi acahaci” - Light give me strength. I’m gonna explain this away by saying that we’re dealing with an approximate transcription using the Latin alphabet and English spelling conventions, which definitely wasn't designed to write down languages outside of well.. ideally Latin. I mean there’s a reason why English spelling is the way it is and one of those reasons comes down to using an alphabet too small for the number of sounds in the language.

Tangent aside, this means those two sounds are probably something like [ɸ] (again click here to hear these) for f and [β~ʋ] for v. These are sounds similar to [f] and [v] but they don’t involve teeth touching lips, check, and they’re probably what human transcribers misheard as [f] and [v].

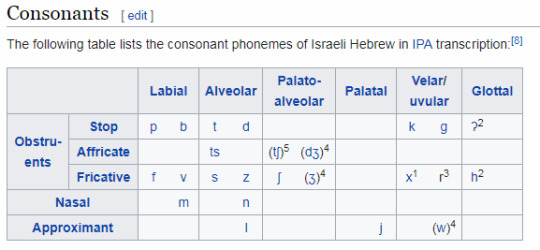

Going through the other transcriptions in the data and making some guesses as to what they could be, we end up with something like this:

and huh that seems familiar... wait a second!

Yeah that’s just Hebrew without voiced fricatives, affricates or the sound [j] (the ‘y’ sound in English), and a bonus rhotic. I mean that’s probably to be expected as Draenei are heavily coded to be Jewish (a good post on that), so it makes sense that the sounds are also similar. It’s a shame to have such quote-unquote normal sounds (the th sound [θ] in ”thin” and “ether” is only in 4% of the worlds languages!) but that’s what you get when English devs make a game for a western audience, you get... ~~the fantasy accent~~ a.k.a discount slavic/germanic accents.

By the way [r] is the ‘trilled’ or ‘rolled’ r and [ɾ] is a ‘tapped’ r like in Spanish "por favor”.

Also, as another side note, this sound [ʔ] - the glottal stop is present in English too but you probably don’t recognise that it’s there. It’s the ‘-’ break in between “uh-oh”, and its also present in some dialects of American and British English where the [t] in words like “bottle” (bo’el) and “water” (wa’er) are replaced with the glottal stop.

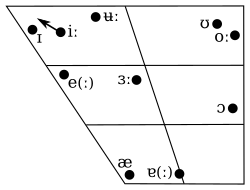

Anyway, onto vowels! And yet again we come back to the problems of English spellings. English has approximately... too many vowels. In my dialect of Australian Standard English there’s up to 20 different vowel sounds depending on how you count. I mean all things considered we've done pretty well with the 5 vowel symbols we've got but good luck trying to accurately represent all this:

(not to mention the diphthongs) with just a e i o u. Most languages only have ~5 vowels so that’s about what I’m looking for. Taking into consideration all the English wackiness in spelling, we end up with what I think are 7 vowels (the pronunciation examples are definitely not gonna be spot on due to regional differences, learn the IPA its good):

[i] - meat, me, three, e-mail

[ʊ] - (short though) good, should, wood

[ʊ:] - (same as above but long)

[e] - bed, head, red

[ɔ~o] - (somewhere between the vowels in) bought, bot (those of you with the cot-caught merger are having real fun now)

[ɐ] - (this one is really only in Australian English) but, strut, bud

[ɐ:] - (same as above but long) bard, palm, start, hard

The two vowels with long forms are the interesting ones. All throughout the canon text we see ‘aa’ and ‘uu’ popping up again and again in things like “Maraad”, “Sayaad”, “Enkaat”, “Vaard”, “Tuurem” and “Krokuun”. Now this could just be stylistic choices made by the dev team to make the language seem more ~exotic~ but I think that it is definitely a case of phonemic vowel length. That’s where distinctions in words are made by elongating a vowel - something Latin had. But it’s not to be confused with what English calls ‘long vowels’, which are really the leftovers from actual vowel length after everyone in 1500 decided to pronounce every vowel just... completely different for some reason. The Great Vowel Shift is an interesting read). Anyway, it makes these double letters make sense, and is way more interesting than random double vowels. It’s also interesting that it’s not perfectly symmetric either, not all the vowels have this distinction, which is cool and perfectly natural for languages to do!

What is weird is that [ɔ~o] doesn’t have this feature, because in our vowel system, it’s almost directly in the middle of our two long/short vowels so it would probably assimilate and end up doing the same thing! So, going off that I’m going to simulate the beginning of language evolution, where the [ɔ~o] sounds is in the process of diverging into [o:] (oar, caught, thought) when it’s followed by ‘r, t, d, k or g’ and [ɔ] (lot, pot) everywhere else.

So, now we have the sounds for our language, how are they used? (dw hardcore conlanging people, I’ve worked out the rest of the allomorphy rules for the consonants but this post is already loooong)

Phonotactics

Phonotactics is largely about how syllables are formed and what sounds are allowed where. In an effort to try and not make the language *too* similar to English I want these rules to differ from English. Luckily, that’d really easy to do because yet again, English is a statistically weird language!

Syllables are divided into 3 parts - The onset, The nucleus and the Coda. For simplicities sake this corresponds to the consonants before the vowel, the vowel, and the consonants after the vowel. English lets wayyyyy too many consonants on either side ending up with abominations like “strengths” having 3 sounds before the nucleus and 3 after, or crimes against god like “twelfths” with 4 sounds after the coda.

Draenei on the other hand seems to be at most (C)(L)V(C). The brackets mean a sound is optional, C’s being consonants, L being ‘liquids’ like [l] and [r] (and [ʋ]) and V of course being vowels. Now going through the data (plus some creative input) we end up with some rules as to what can go where...

but we’ll leave the details of that for the final documentation and head onto...

Spelling! Everyone’s favourite...

There have been countless forum posts about how to pronounce ‘Draenei’ and even between developers at different panels there doesn't seem to be a consensus. This is probably due to the inconsistent spellings used throughout the lexicon so far - draenei and auchenai rhyme (I think) but they’re spelt with different endings!

With the language I have a few main goals

- Make it match as closely as reasonable with canon and common interpretations

- Have the spelling be consistent (same letters should always produce the same sound)

- In line with the first one, keep as much of the spelling the same as possible

- Make it as alien as possible within reason (sadly phonetics and phonology will not be the place to do that)

So coming to a word like “Draenei”, I have to break at least one thingon that list. Personally I want it to be pronounced [drɐ.naɪ] (druh-nai). So, to be consistent with the sounds from before it should be spelt ‘Dranai’ but that definitely won’t do, or I could keep the spelling and pronounce it literally [drɐ.e.ne.i] (druh-eh-ne-ey to give a rough guide for that), which is... equally bad.

The compromise I'm going with is keeping the spelling of Draenei but making the [aɪ] (ai) sound spelt ‘ei’ across the language. Meaning is gonna be Auchenei. Well, not really because there’s still a bunch of other spellings that need standardising.

the ‘ch’ in “Auchenei” is pronounced with a [k], so is the ‘c’ in “Dioniss aca”. Going through and standardising things like ‘ph’ -> ‘f’, ‘ch’ -> ‘k’ or ‘sh’ depending and rewriting vowels to match the phonology we end up with something that preserves most of the identity and look of the language but just makes more sense! Aukenei would then be the spelling I’m using in the lexicon, probably with a little note for the canon spelling.

So, from now on I'm going to be using the reformed spelling TM, which hopefully will mean anyone attempting to speak this language will have an easier time getting what I'm envisioning, cuz everything is now consistant.

That about does it for this post. Yet again if you made it all the way to the bottom, congratulations! Hopefully the next posts will be a bit more interesting (I’m so fucking pumped for how the culture will impact the grammar and vocabulary holy shit) but I gotta get this one out of the way.

Next time, we’ll be doing word-building - the morphology of the language, Thanks for reading!

#draenei#wow#World of Warcraft#lorecraft#headcanon#theorycrafting#language#conlang#linguistics#draenei language#not art

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Viktor Krum meta: language use & accent

Before I even start in earnest, I just wanna say this is particular to my interpretation of Viktor and comes with all my hangups as a Bulgarian person living in Brexit Britain; also it got pretty long. But if you like some light sociocultural analysis along with your meta, by all means read on.

So we all know how Rowling chose to represent Viktor—quiet, grumpy, slightly bumbling, and when he does speak, not particularly articulate. He does have a decent vocabulary range, but his accent is harsh and noticeable. He is also shown to speak in present continuous tense, as seen here:

‘Vell, ve have a castle also, not as big as this, nor as comfortable, I am thinking,’ he was telling Hermione. ‘Ve have just four floors, and the fires are lit only for magical purposes. But ve have grounds larger even than these – though in vinter, ve have very little daylight, so ve are not enjoying them. But in summer ve are flying every day, over the lakes and the mountains –’

Here’s an example from DH, where you can see he still has the accent, but also the (not bad) range of vocabulary he’s given, as well as his correct use of prepositions:

‘He retired several years ago. I vos one of the last to purchase a Gregorovitch vand. They are the best – although I know, of course, that you Britons set much store by Ollivander.’

I'm here to explain why I do it (a little) differently.

First of all, let me lay some groundwork. He was born in the mid-seventies in Bulgaria, which at the time was part of the Eastern Bloc. I'm going to refrain from talking about the ramifications of that on our culture, but keep in mind we were very much in bed with the Soviet Union during his formative years. Furthermore, he went to Durmstrang—a school known for accepting pupils from a very wide geographical range, seeing as it's located somewhere ‘in the far north of Europe’ and yet accepted Viktor, from way down in southeastern Europe. Either he was exceptional, or it's a pretty multicultural school.

So what does that tell us? Well, to begin with, the boy is more than likely to have been fluent in at least, AT LEAST, three languages: Bulgarian, which was his native language, of course; Russian, which was a mandatory subject from an early age in school (even if he didn’t go to muggle school, he would’ve had to speak it to avoid rousing suspicion), and which is relatively easy for a fellow Slavic language speaker to learn and retain; and either German or one of the Scandinavian languages, which he would've been taught in while at Durmstrang. At minimum.

At the same time, the Triwizard Tournament would've presented Viktor's first serious brush with the English-speaking world. English was not taught in school at the time (see also: Cold War); if you picked up a second foreign language (on top of Russian, which basically didn't count), it would be either German or French, due to long-standing sociocultural ties (i.e. our intelligentsia were largely educated in France, and we sided with Germany in both world wars; don't ask). So unless his family went out of their way to teach him English, which they would've had no reason to as it wasn't seen as useful, he wouldn't have learned it formally at any stage.

How do I know all this? Well, I’m Bulgarian for one, and also my parents are only 5-10 years older than Viktor would be. They speak, or at some point have spoken, 4-5 languages between them, of which English isn’t one. In order to study it back in the 70s and 80s, you’d have had to go to a special school that was difficult to get into, and not hugely popular either.

So yes, his spoken English was clumsy in GoF when he was 18, and he probably never lost the accent, but 1) his written English was likely much better (see also: exchanging letters with Hermione for years), and 2) his mastery of the language will have improved pretty rapidly once he made friends who spoke it. The level you see in GoF, animated discussions with Hermione and all, is his default level without having studied English in any capacity, so to think it would stay that way into his adult years is not doing the man justice.

Also him using present continuous at any stage instead of simple present tense makes no sense, considering it’s 1) more complex, and 2) does not exist in Bulgarian, his native language. So I’m not even engaging with that.

Anyway, how has all this informed the way I write him? For one, I mostly focus on the post-SWW period, when he’s:

travelled quite widely in connection with his international career, making a lot of friends from different countries;

been pen-pals with Hermione and kept in touch with Fleur for a number of years;

chosen to settle in the UK in the aftermath of the war.

What all this means is that he’s had a lot more practice reading, writing, and speaking in English, and his words are likely to flow a lot more smoothly, as well as picking up some colloquialisms from his teammates. As for his accent, not doing the whole ‘vos’ thing is a very conscious choice. I don’t shy from a phonetic accent (see also: Alastor), but on the one hand, that’s not what my accent sounds like so I find it hard to reproduce, and two, I think it’s borderline comical, tbh. Also it makes him sound like Otto von Chriek, but that’s neither here nor there.

What I do instead is, I try and limit his vocabulary and the length of his sentences. I’m aware my command of English is above and beyond what he’s likely to attain, so I don’t make him sound like me. I mess up the odd tense and preposition, throw in the odd expression that doesn’t exist in English, make him pause and think a lot about what he says, etc. And that’s it, folks. That’s how actual Bulgarian people speak English. Compared to the other languages he’s fluent in, it’s really not a difficult one to pick up.

What I’m trying to put across here is that the whole stereotype of Eastern Europeans being stupid and bad at English in itself is really harmful. For my American friends who may not be aware of European power dynamics, we are some of the latest additions to the EU and have received tons of backlash from western Europe. Polish, Romanian and Bulgarian immigrants have been racialised by the media, particularly in the UK, and written off as cheap labour/benefit fraudsters. Hell, a lot of people who campaigned and voted for Brexit directly blame us for a lot of the UK’s issues, like the state of the National Health Service (actually due to Conservative party cuts under the guise of austerity) and a poor job market (driven by a shitty fucking economy, and not at all helped by the nearly inevitable Brexit-related recession that’s on its way).

If you want to know more about why that's a massive issue, just hmu, I can go on for days, but in terms of Viktor, I refuse to perpetuate JKR’s subconscious biases against Eastern Europeans by making him sound like some sort of illiterate idiot in my own writing. He was Durmstrang's champion, and as such we have to assume he was reasonably intelligent. Quiet, reserved, lacking confidence in his language skills, nervous around Hermione—definitely. Stupid and bumbling, not so much.

#this got waaaaaaay long#but honestly someone had to say it#i'm so done with everyone shitting on eastern europeans whether consciously or not#he's SMART#and post-GoF he has LOTS of friends he speaks to in english#so give him some fucking credit#char: viktor krum#muse: viktor#headcanon: viktor#meta: viktor#mine: meta

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Icelandic is Easy to Learn

There seems to be this idea out there that the Icelandic language is an incredibly difficult language for English speakers to learn, so when I first started studying it I was a bit nervous. However, although I still haven’t been studying it for very long, I’ve yet to run across anything that’s scared me off, and quite a bit that actually makes it quite easy to pick up as a native English speaker. So to cast off some of the stigma, here are some things that make Icelandic easy to learn (or at least not as horrifying as I’d been led to believe):

Spelling is very consistent. Icelandic spelling is mostly phonetic, where each letter represents only one sound. While there are a few instances where letters aren’t pronounced exactly the same, the variations are regular so you can learn when they’re said differently instead of just having to guess, and over time they will become natural with practice. French is supposed to be relatively easy for English speakers to learn due to shared vocabulary, but Icelandic beats French hands down in this area.

Most of the sounds are similar to English. Many of the letters are pronounced basically just like English, and while it might look a little intimidating with all the extra vowels with accent marks and so on, most of those are sounds we actually have in English, they just represent them explicitly in Icelandic, which actually helps with the point about spelling above. Here is a great video that very clearly explains the Icelandic alphabet, and as you can see, out of the 14 vowels/diphthongs there are only 3 that aren’t in English. So sure, there are some sounds that aren’t in English, but that’s going to happen in almost any language, and Icelandic doesn’t seem to be any worse in this area than German, for example. In fact, if you know both German and English, you’re pretty much set when it comes to Icelandic phonemes.

The stress is always the same. In Icelandic words are always pronounced with the stress on the first syllable. In Spanish, for example, the stress changes based on which letters a word ends with and whether or not there are any accent marks, so you have to learn those rules and then memorize each exception so you know where to put the accent, and it can be a little tricky. In Icelandic there is only one rule that never changes, making it super simple.

There are only four cases. Okay, if you’ve never studied a language with cases before, having any at all can be a bit daunting coming from English since we don’t really use them much, but if you’re going to learn a language with cases only having four is pretty great! It’s the same number of cases as German has, and waaay better than Slavic languages that can have six or seven, and there are other languages which have even more.

There are only three new characters to learn. A lot of people seem to be intimidated by the special characters Ðð, Þþ, and Ææ, but if you compare those three measly characters to languages like Greek, Russian, Arabic, or even Japanese -- which has two separate syllabaries on top of thousands of kanji to learn -- you can see how it’s nothing at all. Best of all, those characters represent sounds that already exist in English, so you can easily learn how to pronounce them. Ð is pronounced as the ‘th’ in ‘breathe’, Þ as the ‘th’ in ‘breath’, and æ as the ‘i’ in ‘hi’. In fact, if you want to say “Hi!” in Icelandic it’s exactly the same: “Hæ!” Similarly, “Bye!” is “Bæ!” You can see too how the spelling here is consistent in Icelandic, using only one character to represent the same sound, while in English we use ‘i’ in one word and ‘ye’ in the other, and in other words we might use even more spellings for the same sound, such as ‘ai’ or ‘y’, or even ‘igh’ (like in ‘sigh’). So even though you do have to learn a few new characters, it’s hardly any, and once you’ve learned them it actually makes Icelandic much easier to read and spell than it would be without them.

A lot of vocab comes from the same Germanic roots as English words. While English has borrowed a bunch of vocab from Latin languages, it still contains many words that come from its Germanic origins, which it shares with Icelandic. You’ve already seen hæ and bæ, and there’s also halló (hello), dóttir (daughter), móðir (mother), hér (here), frá (from), takk (thanks), heitt (hot), kalt (cold), hjálp (help), fiskur (fish), nót (net), undir (under), mús (mouse), and many more.

Basic grammar is very similar to English. Like I’ve said, I haven’t been studying long so I’m sure there’s more complicated stuff coming up, but in the basics I’ve run across so far the word order is so similar to English that you can pretty much take an English sentence and switch out the English words for their Icelandic versions and have a correct sentence. Some examples:

I am...

Ég er...

You are...

Þú ert...

I am from Canada.

Ég er frá Kanada.

Are you from Iceland?

Ert þú frá Íslandi?

I am not from Spain.

Ég er ekki frá Spáni.

They come from Japan.

Þau koma frá Japan.

I don’t know about you, but the above doesn’t seem so difficult to me. Even if you haven’t learned the pronunciation yet, the grammatical structure is very familiar and many of the words look similar to their English counterparts.

Of course there are difficult things about Icelandic, but there are difficult things about every language. Icelandic is certainly not an impossible language to learn, and there are many things about it that are actually quite simple compared to other languages, or at the very least not any worse. If you’ve considered learning Icelandic, but were hesitant after hearing how terribly difficult it supposedly is, maybe this will show that it doesn’t have to be so scary after all.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Email Order Estonian Brides Want To Meet You At Increased by

Online dating features work as a real panacea for those, so, who didn’t meet the real appreciate yet. To get an interesting interlocutor is a must if you would like to mise an Estonian bride. Put together some interesting stories with regards to your life and homeland to entertain your girlfriend. This does not mean you have to be a conduttore. Telling a unique story or maybe more about your life in America will be thoroughly enough.

Patience and openness of Estonian lady are combined with ability to give and even sacrifice. Often these features, reflected inside the character of this babe, generate her an extremely soft and sort person that allures people to her. Estonian star of the wedding finds pleasure in compassion and assisting people. It makes them good homemakers, caring wives or girlfriends and mothers.

Even more, in the event you thought Travelers include huge parts, wait till you observe the amount of foodstuff the average Estonian can store, in one sitting down. Even with how thick the porridge is normally, they even now accompany this with meat. More kinds of meat than you probably ever knew been with us, and huge numbers of bread and milk. And that is just the beginning, Once you satisfy the family and will be officially made welcome as one of them, you better go there with a clear stomach.

What you should be jealous about for sure – is that in their capital, Tallinn, people transportation is free to get formal residents with the capital. Reduced expenses, less private automobiles, cleaner weather, lower polluting of the environment, and more cash for metropolis due to raising number or registered dwellers of the capital who spend their taxation here, not really elsewhere. What their Estonian bride-to-be may be excited by your country’s public transportation program (if she moves to you from Tallinn) – that this wounderful woman has to pay money for to trip a coach or a subway.

It’s hard to get one different area worldwide, where non-native British music speakers can be consequently comparable with the event to make sure you English speaking most people in highly produced countries. Straight away, you can face which usually facing you is actually a well-educated and intensely clever persons. Concerning Estonian gals, they have much simpler that you discover a like-minded match up with, while not incomprehensive stories, which dwellers from further countries could explain, whilst not the many broke bears and mutilated fates. Any time these types of like you – they wanna meet most people because you are a exceptional someone to many people. They’ll actually decide to buy a good aeroplanes ticket into their cost to arrive to work out many people (and that they won’ m end up having visa on your UK or just the US).

Estonian girlfriend will do the household chores. Her hobbies, task, and friends will never get in the way with your family. Of course, if she selects you simply because her existence partner, she will under no circumstances cheat you since Estonian women are devoted. They know that there is absolutely nothing more important over a healthy family group.

‘Ghana Is definitely Lucky To Have You Mainly because President As of this Time’ Council Of State To

What is normally peculiar about Estonia? Just like a lot of other European countries, you can live the whole life in Estonia comfortably without ever uttering a word of Estonian. Nearly everybody understands British, to ranging degrees. This is particularly so inside the large places, although they may not be as cozy speaking British.

Estonian young women are a variety of feminist and conservative. A lot of section of these people have become woefully outdated to what is the functions males and females should use within the traditions: numerous Estonian brides feel that guys should lead the wedding and start to get in control of most decisions used by a few. This can be basically the influence of the patriarchal Eastern roots that affect that it’s guys whom really should be at the mind of every close family. Estonian gals dating men from other international locations anticipate them to resemble all their regional guys within their motivation to make the responsibility of delivering just for the household.

You must have seen a large number of Russian or perhaps Latin females on online dating services. People learn about them because of the nature and beauty. However , there are Estonian young girls also exactly who pack a lot of surprises. Delightful, good-natured, calm, and classic, these females are ideal for associations. In worldwide dating, they will will be the most wanted.

Once you travel to Estonia to fetch your Estonian bride, be mindful not to remove yourself in food. Estonian food is indeed delicious that you can easily get lost in the variety of likes and odours. That’s not junk food like in the motherland, however the food there may be far not always healthy, both. It’s hence simple to gain weight there and lose your system forms.

Whenever you already figure out, it will not take a whole lot of your time to fill this form out. And when you do it, you will see your only created account. But it should empty so you will need to complete it out with increased information about yourself and publish at least a couple of your photos. And here you will be, ready for connection with beautiful Estonian singles.

Present delivery: one of the most effective ways to show warm Estonian birdes-to-be that you good care is to get in touch with them daily and, at times, surprise these a little something. Many sites could have a selection of reveals their local divisions can easily deliver about site. Generally, these presents include flowers, candy, plush toys, scent, and jewelry.

The biggest launch of the century To Start Going out with Estonian Girls

Chances are, you’ll never heard of Estonian brides to be for relationship before — even if you aren’t exactly new to online dating. Estonian brides have the reputation of currently being tall, brown, and Scandinavian searching. Estonians basically think of themselves as the other Scandinavian countries perform. That much is sensible since Germans, Danes, and Swedes ruled it for most of Estonia’s history.

Therefore , Estonian women of all ages dating on-line hope to find a person who’ll court docket and astound them. Finally, there might be the very best variety look we all talked about above. However , have a tendency imagine about practically all Estonian women as huge blondes with blue eyesight. While most females in Estonia indeed appear like that, in addition , you will discover a lot of pink-heads and brunettes inside the same country.

Estonian women are also very skinny, typically. Their particular standard to get beauty skews closer toward slim, really and bent. Larger girls (whether fat or just with larger frames) are less prevalent. The capital is particularly known for having close to a 0 % rate of obesity.

Reward delivery: online dating sites can be rough — due to the fact you cannot pay your beautiful women all the indications of emotions she deserves. Well, which has a reliable organization, you can! This sort of sites may deliver flowers, candy, and other small gift ideas directly to your meet.

This is exactly what the young contemporary gentleman requirements. One of many greatest different types between the a pair of these kinds of brides to be to be is that Estonian women use a European attitude. They are much nearer for you widely, as most girls in Estonia find out The english language by a fantastic stage, there’ll hardly become any language hurdle. Simultaneously, an Estonian girl will certainly gladly accessible to a person she is vitally thinking about.

High popularity goes either to exotic special gems from incredibly hot southern countries or destinations or young women from Far eastern and Western Europe. In the event the first ones are good for the purpose of unusual practices and different nationalities, the Eu girls happen to be popular because they are close to american men by their lifestyle, all their worldviews, and culture. Even though the attention that is certainly mostly paid by Slavic girls from Spain, Ukraine, and Belarus, Estonia is another region of the ex – Soviet Union that should be also considered as any to find a star of the event. Beautiful Estonian women will be well-educated, wonderful, family-oriented, and a friendly to overseas men, so, who are interested in marital life.

Once a great Estonian mail-order bride comes with thawed and she already knows a person better, your woman becomes considerably more relaxed, casual, and also unveils her warm-hearted side. However, you should be ready that a hot Estonian women will not likely https://www.interracialdatingsitesreview.com/estonian-brides/ demonstrate much of herself on the first of all date. She is going to hardly come to contact.

Northern type of appearance with white epidermis and profound blue or perhaps green or grey sight doesn’t generate Estonian ladies unique, although they do make them very attractive. The main point is within its specific and being aware of some secrets may help you to win the heart of pretty Estonian lady.

All of us cannot pressure this enough — Estonian women are exceptionally beautiful. You probably picture a typical Estonian daughter as a tall blonde with a slim number and green eyes — and you’re here quite directly to do so. However if you’re even more into brunettes or red-heads, it’s also possible to locate them in Estonia. After all, no country, no matter how far up North, can consist of blondin only. Estonia, in particular, got its publish of invasions and politics turmoil, therefore an extra ‘influx’ of family genes was unavoidable. Still, it can one of the few countries in European countries that remain pretty much mono-ethnic.

Bài viết Email Order Estonian Brides Want To Meet You At Increased by đã xuất hiện đầu tiên vào ngày ĐÔ THỊ MÔI TRƯỜNG.

0 notes

Text

Why Don’t We All Speak the Same Language? (Earth 2.0 Series)

Linguists predict that some 3,000 languages spoken will go extinct within the next century. (Photo: Paul Stevenson/Flickr)

Our latest Freakonomics Radio episode is called “Why Don’t We All Speak the Same Language? (Earth 2.0 Series).” (You can subscribe to the podcast at Apple Podcasts or elsewhere, get the RSS feed, or listen via the media player above.)

There are 7,000 languages spoken on Earth. What are the costs — and benefits — of our modern-day Tower of Babel?

Below is a transcript of the episode, modified for your reading pleasure. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, see the links at the bottom of this post.

* * *

James COOK [English]: I’m sorry, I don’t understand.

Anisa SILVI [Jakartanese]: Saya tidak paham yang kamu katakan.

Christoph PARSTORFER [German]: Tut mir leid, ich verstehe dich nicht.

Ria VIDAL [Filipino]: Pasensya na, pero hindi ko naiintindihan ang sinasabi mo.

Daria JANSSEN [Dutch]: Sorry, ik begrijp niet wat je zegt.

Dayana MUSTAK [Bahasa Malaysian]: Mintak maaf, saya tak faham awak cakap apa.

Rendell de KORT [Papiamento]: Mi ta sorry, mi no ta compronde kiko bo ta bisando.

Emília VÁMOS [Hungarian]: Sajnálom, nem értem, amit mond.

Kanako TANAKA [Japanese]: すみません、あなたが何を言ってるのかわかりません。

Peter KANG [Korean]: 죄송 한데, 뭘 말했는지 못 알아들었어요.

Katie HARRELL [High Balinese]: Ampura, titiang tenten midep.

Maria Luisa MACIEIRA [French]: Désolée, je ne comprends pas ce que vous dites.

Stephanie TAM [English]: I’m sorry. I don’t understand what you’re saying.

Making yourself understood. It’s one of the most defining acts of being human, and among the most important. But after all these millennia on Earth 1.0, we haven’t perfected it. It almost makes you wonder if we’re working through some ancient curse …

The biblical story of the Tower of Babel explains the problem of linguistic diversity. (Pieter Bruegel the Elder/Wikimedia)

Esther SCHOR: Well, the story of the Tower of Babel is told in the eleventh chapter of Genesis …

Shlomo WEBER: Whether it happened or not, it’s not for me to judge …

SCHOR: … and it comes down to us as a myth about the origin of linguistic difference.

WEBER: … but it is definitely important.

SCHOR: So the project was to build a tower, and I’m quoting, “whose top may reach to heaven, and let us make a name lest we be scattered abroad on the face of the whole earth.”

Michael GORDIN: And God looks down on this and says, “If they can do that, there’s no stopping them from whatever else they can do. So I’m going to go down and confound all of their languages.”

John McWHORTER: That was a tale created by people for whom different languages were a problem.

GORDIN: “That way they will not be able to communicate with each other and accomplish this joint task.”

McWHORTER: They were thinking, “We can’t communicate with the people over the mountains. We might want to trade with them. We’re beginning to think they might want to fight us, and we can’t even have a conversation.”

SCHOR: God’s revenge on the builders of Babel was to blunt our capacity to make ourselves understood and to understand.

McWHORTER: It is a very rich story because it depicts the multiplicity of languages as a scourge.

SCHOR: The curse of Babel is an existential condition in which we live every day.

WEBER: This is both the blessing and the burden: the large number of languages, and different societies dealt with it in different ways.

SCHOR: We use language to communicate, but we cannot rely on it to make ourselves understood.

GORDIN: The thing that really resonates with me about the story is this sense that common language can produce common purpose, and an absence of a common language can confound that common purpose.

McWHORTER: Today, we hear the Babel story and many of us have to make an adjustment, because many of us think, “Now there are lots and lots of languages and so people can’t communicate. And isn’t that neat?!”

Is it neat? Well, that depends — on who you are, where you live, which languages you speak — and which ones you don’t.

WEBER: This is both the blessing and the burden.

Today on Freakonomics Radio, the blessings and burdens of linguistic diversity. Or, to put it more bluntly, what are the costs and benefits of our modern-day Tower of Babel?

MCWHORTER: I find it fascinating that there are seven thousand different ways to do what we’re doing right now.

We talk about how talking began:

McWHORTER: There are many theories as to why people started using language, and some of them are ones where you want it to be true because it’s cool.

And: if we could start over, what would that look like?

McWHORTER: The truth is that if we could start again, I don’t think anybody would wish that the situation was the way it came out.

* * *

Today’s episode is part of a recurring series we call Earth 2.0. The idea is pretty simple. If we had a chance to reboot our planet — taking all our entrenched, path-dependent systems and institutions, and rebuilding them from scratch — how would they differ from how the world works today? Our first couple episodes looked at the economy of Earth 2.0 …

Angus DEATON in a previous Freakonomics Radio episode: I don’t think we should be spending large amounts of money inside other people’s countries.

Rosabeth Moss KANTER in a previous Freakonomics Radio episode: If you don’t pay attention to the people on the other end of that equation, even if you think you have the power, it doesn’t work.

Erik Olin WRIGHT in a previous Freakonomics Radio episode: An unconditional basic income, which you could pay for out of the gains from trade. Right?

Bryan CAPLAN in a previous Freakonomics Radio episode: I’m very strongly against the universal basic income.

Okay, so we shouldn’t be expecting a consensus — but isn’t that part of the fun? With today’s language experts, for instance — you wouldn’t expect all of them to have the same favorite language …

McWHORTER: My favorite language ever is Russian.

Lera BORODITSKY: I love lots and lots of languages.

GORDIN: The French will never speak English. The Germans will never speak French.

Among the experts we’ll be speaking with … John McWhorter:

McWHORTER: Associate professor of Slavic languages and linguistics at Columbia University, and host of the Lexicon Valley podcast at Slate.

Lera Boroditsky.

BORODITSKY: I’m a professor of cognitive science at the University of California, San Diego.

Esther Schor:

SCHOR: I’m a professor of English at Princeton University.

Michael Gordin:

GORDIN: I’m a historian of science at Princeton University,

And Shlomo Weber:

WEBER: At the moment, I’m the director of the New Economic School in Moscow.

Along the way, we learned that people who like to talk about talking, who have an intense interest in language, often come by that intensity through personal experience. For John McWhorter, it began when he was four.

McWHORTER: … when I happened to hear a little girl speaking what I later knew was Hebrew. The idea that she could talk to her parents in a way I couldn’t understand just knocked me out! Ever since then, I’ve been reveling in the fact that there are 6,999 other ways to do this. How do they differ? Why are they different the way they are? That is what got me into language.

For Boroditsky, it started a bit later:

BORODITSKY: It actually started when I was a teenager. I wassta really argumentative as a teenager and I loved to pick fights with people about big questions. What is truth and what is justice? And liberty and things like that. What I noticed was that a lot of the arguments hinged on how we used these words, the meanings of the words seemed to shift as the conversation went on, and different people use the words differently. At first I thought, “If I study language, I’ll be able to get to the bottom of what truth and justice and liberty really are.” Then, as I started actually studying language, I learned exactly the opposite is true — that these meanings are constructed in conversation, constructed in context.

As for the Russian-born Weber, his interest in language came from living in many different countries. This included a stint in Canada, where he was expected to lecture in English.

WEBER: First of all, all of my lectures were written. There was no place for improvising, so I prepared sleepless nights, sleepless days. Then, the very sad thing happened to me. I prepared the material for my lecture. Lecture was 90 minutes, but I was running out after 50 minutes. So the 40 minutes — I had nothing to say. This experience, I will never forget! No, I tell my children: “Standing in front of room of 200 students — after you overcome that, you can do many things afterwards.” It was really painful, but taught me a very good lesson. I always came prepared after that.

For Shlomo Weber, it was a lesson learned. For the young John McWhorter and his Hebrew-speaking friend, the ride was just beginning.

DUBNER: Let me ask you this: with that example, from when you were four years old …

McWHORTER: I sobbed like a child. And I was a child.

DUBNER: I could see a thought process going one of at least two ways: one would be the infinite possibility and how exciting that is — or maybe not infinite but the expansive possibility. The other would be this existential, “Holy cow, that makes life more difficult than it needs to be.” Which way did you go?

McWHORTER: In thinking about my despair in finding out that my little Shirley spoke Hebrew, I have to peel back the layers of the onion to remember how much of a burden, what a tragedy a foreign language seemed to me at the time. I didn’t like that suddenly this girl — and she and I were seeing each other to the extent that you can be having a romantic relationship at four, you know, holding hands. To the extent that she could talk in this way that I couldn’t understand or produce, I was losing her. As time went on, my feelings started to be, “I’m going to learn to do that.” It’s my Mount Everest. I’m not an athlete but I’m a ‘linguete,’ so to speak. But originally, it was a barrier to communication and connection. Of course, in my mind, there were maybe two languages: English and this thing called Hebrew. I didn’t know how many others there were, I didn’t know what the task would be.

DUBNER: I’d love you to talk about the origin of language briefly.

McWHORTER: Stephen, it’s so hard, because there was no way to record it and it happened long before there was any writing. If humanity had existed for 24 hours, writing comes along at 11:06 p.m. It was a long time ago and there’s no other species that’s creating fluent, complex language.

There are many many theories as to why people started using language, and some of them are ones where you want it to be true because it’s cool. There’s one theory that it started with people singing and that that became language. There’s another theory — and this is interesting — the idea is that humans are the only primates who aren’t hairy enough for infants to hold on all the time because there isn’t enough hair. So you have to put the infant down while you’re foraging.There’s a theory that speech began because human women could coo at their child and keep the child calm, as opposed to, if you’re a chimpanzee where the child can always be up against you. But I think it probably started with humans needing to group together to scavenge animals dead at a distance that were too big for one human, or even one little group of humans to deal with.

DUBNER: Regardless of why language started and developed as it is, I would think that there would have been a large incentive for everyone to speak the same language. Whether it’s utilitarian, or gossip, or singing, or cooing to one’s family, it would just seem like there’s a lot less transaction cost if we’re all speaking the same language. How did it come to be and why did it come to be that so many languages bloomed?

McWHORTER: Language is inherently changeable not because change is swell but because as you use a language over time and you pass it on to new generations, brains tend to start hearing things slightly differently than they were produced. After a while you start producing them that way. Next thing you know, you have a new sound.

DUBNER: It’s Telephone before there is such thing as a Telephone.

McWHORTER: It is exactly that. That is as inherent to language as it is inherent for clouds to change their shape. It isn’t that that happens to some languages and not others. That’s how human speech goes.

DUBNER: Is a lot of the linguistic diversity or the linguistic splintering that we’re talking about largely a function of the fact that spoken came so much before written? If there had been written that we wouldn’t have splintered?

McWHORTER: If writing had come along immediately, quite certainly there would have been less change from place to place. But instead, because until really about 10 minutes ago language was just spoken, it was allowed to change at the speed that it normally does. That change can happen in any one of various directions, which means that once you have two human groups, then their language after a certain period of time is not going to be the language that the original group spoke, just because say the sound “ah” might become “eh.” It might become, “uh.” You can see how a language would become a new one over time. Next thing you know, you have thousands of languages instead of one just because languages change like cloud formations.

DUBNER: Given our pretty advanced development of language and communication, what are the big problems with language as it now exists?

McWHORTER: Well, we have 7,000 languages, and it’s safe to say that about half of them are severely endangered. Another thing that many people would consider a bad thing is that certain, roughly 20, big, fat languages are eating up so many of these small ones. What makes this regrettable to many, and quite understandably, is that the one that’s having probably the most success is English. English is this one language that was the vehicle of a rapaciously imperial power and now America is the main driver. That language is eating up all of these other languages, and in some ways, their cultures.

Okay, let’s take a step back here, because John McWhorter has brought up a few important points. Number one: linguistic diversity has been a natural hallmark of human communication. Number two: linguistic consolidation has also been a strong trend. Or maybe “hegemony” is a better word for it — most recently, in the form of English. But in earlier centuries, there were other big, fat languages gobbling up the others — Greek, and Persian, and French. Sometimes, one language would come to dominate a particular domain: in Western and Central Europe, for instance, science was conducted in Latin. Michael Gordin, from Princeton:

GORDIN: About 1200 to roughly 1750 is the period of time when you could expect that everybody interested in how falling bodies behave or how the circulation of the blood works would be able to read Latin.

So there are a lot of factors that may influence whether, or how broadly, a given language will spread. But the central conflict, it seems — the central question we should be asking about language here on Earth 1.0 — is this: what is the right amount of linguistic diversity? Is 7,000 an acceptable number of languages for 7-plus billion people? Is … one… a better number? Let’s think about it, first, on a personal level. What language or languages do you speak? What benefits do you think that confers — whether economic, cultural, or otherwise? What do you think you lose by not speaking other languages? And how do you feel about people who speak those other languages? Maybe you think of them as more unlike you than they actually are, solely because they speak a different language? And how much does the language you use to express your ideas and emotions influence the ideas and emotions themselves? These are obviously hard questions, maybe unanswerable. But let’s start with a bit of economic analysis of language. That’s what Shlomo Weber has been thinking about at least since that stressful first lecture he gave in English.

WEBER: This experience, I will never forget!

DUBNER: That makes me think about the costs of communicating in a language that you don’t have mastered. If you just think about the cognitive stress — literally, your brain is working hard on just the language — so it can’t be working on the ideas and maybe the emotional stress and physical stress.What do you think is the effect of all that?

WEBER:Oh, it’s tremendous. It’s actually a lot of studies on immigration that show the emotional stress, not only for yourself or your own success; you care for the family.

To measure the costs of different people speaking different languages, researchers like Weber use a metric called “linguistic distance.” When it comes to trade, for instance, Weber documented that a 10 percent increase in the probability that two people from different countries share a language increases their trading by 10 percent.

WEBER: It is sometimes difficult to isolate the impact of languages but the general statement is: the closer the countries in a linguistic sense, the larger the volume of the trade, and the easier to trade between the countries.

DUBNER: Let’s say there are two nations that want to trade, maybe even 10 nations that want to trade. If you can pick one thing that they have most in common in order to make good trade — forget about all the other stuff — would it be a political viewpoint that’s shared, cultural, or linguistic?

WEBER: I would say language, if you really separate among the three. The problem is that the linguistic and cultural — they’re interdependent.

But one study in The Journal of International Economics found “at least two-thirds of the influence of language comes from ease of communication alone and has nothing to do with ethnic ties or trust.” Furthermore, it found the impact of linguistic factors was still strong even after controlling for “common religion, common law and the history of wars as well as … distance, contiguity, and two separate measures of ex-colonialism.” It’s easy to see how this kind of thing might play out in practice.

WEBER: A couple of days ago, I attended the economic forum in St. Petersburg and I listened to this speech of the Indian prime minister. Mr. Modi spoke in Hindu. He chose not to speak English. He basically relied on translation — on a single translator, who translated his speech into Russian.

youtube

Unfortunately, it wasn’t very good Russian …

WEBER: It was horrible. It was unbelievably bad translation. I was just stunned by the fact he continued to do it. It was obvious that there was no contact with the audience. Audience lost an interest very quickly, because when you give your emotions, your ideas, to some translator you don’t know what will happen.

How do you put a price on what gets lost in translation? That’s hard to do — but it’s a non-trivial amount, that’s for sure.

WEBER: It was such a tremendous chance for him. People were actually expecting this speech and saying, “India is open for business.” I talked with a Russian businessman after that and they were hesitant about all these things. “If they don’t speak English, why would we go there?”

But the science here is not very precise.

WEBER: It’s different in different areas. The trade of China is now growing everywhere in spite of Chinese language being very distant from everything else, so …

So it’s important to look at the particulars. In general, though?

WEBER: In general, the literature showed that linguistic diversity has a negative impact, generally speaking, on economic growth.

So linguistic diversity has a negative impact on economic growth. There’s also the roughly $40 billion a year we spend on “global language services” — primarily translation and interpretation. And another $50-plus billion a year spent learning other languages. There are obviously many reasons you might want to learn another language, but the primary driver seems to be economics. We looked at this in an earlier episode called “Is Learning a Foreign Language Really Worth It?” One European study found that a second language could increase your wages between 5 and 20 percent, depending on which language and country. The biggest boost, perhaps not surprisingly, went to those learning English. There are still plenty of places where English won’t do you much good. But at something like 1.5 billion speakers, it has certainly become what John McWhorter calls a “big, fat language” — which is even more striking when you consider that only about 400 million of them are native speakers.

GORDIN: The reason why English is so popular around the world or so widely used has to do with the British Empire.

Michael Gordin again.

GORDIN: Otherwise, it’s the language of a small island in the North Sea that happened to spread fairly globally. Whereas Chinese is the language of a very large land mass that’s contiguous.

But the rise of English isn’t all tied to British colonialism.

GORDIN: The story is partially about the rise of American power and the attractiveness of American higher education, the desire of people to get to postdocs in the U.S. and to publish in U.S. journals.

Consider science, previously dominated in the West by Latin; and in the East by Sanskrit and Classical Chinese.

GORDIN: Today, there is basically one common language for communication in the elite natural sciences like physics, biology, chemistry, geology, which is overwhelmingly English. By overwhelmingly, I mean over 95 percent of world publication in those sciences is in English, and there’s never been anything quite like that before.

This requires more than just a familiarity with English.

GORDIN: What we now demand of people is an extremely high level of both written and oral fluency in English. It’s very hard to get that fluency and it imposes an educational burden on them. You have people in Japan who spend years learning English, when their counterparts in Canada are just learning more science. That creates a mechanism that reinforces the elite status of Anglophone institutions. There probably are people in the world who would be wonderful scientists but can’t get the English, and therefore can’t quite participate in the international community.

And if they can’t participate — what kind of science is the rest of the world missing out on? The massive leverage of English in the scientific community — and in other communities — is something you probably don’t think about much if you are a native English speaker.

GORDIN: The native speakers of English learn English for free from their parents and the community around them. They benefit enormously from everybody else spending years putting this language into their heads.

For a native speaker, that’s the status quo.

GORDIN: The problem with the status quo is it’s not fair. The people who benefit the most from it pay the least for it.

McWHORTER: One of the hardest things about a big-dude language like English and its influence …

That again, is John McWhorter.

McWHORTER: … is that it’s easy for a generation to start to feel that that language is the real one and so that’s the way that a language can eat up another one. Next thing you know, the kids really only speak English or some kind of English, and the indigenous language is gone. That has happened, for example, to countless Native American languages. To an extent, Native American languages were beaten out of people in boarding schools. But then to another extent, where that damage wasn’t done, there was often a sense that, “English is what’s spoken. What Grandma speaks is for Grandma, but I’m not Grandma.” All it takes is one generation like that, and the language is gone.

Linguists predict that of the roughly 7,000 languages now spoken on earth, some 3,000 will go extinct within the next century.

VIDAL [Filipino]: Ayokong maglaho ang aking wika habambuhay.

AMORIM [Portugal Portuguese]: Eu não quero que a minha língua se extinga.

MUSTAK [Bahasa Malaysian]: Saya tak nak bahasa saya pupus.

CHOW [Malay]: Saya tidak mahu bahasa Melayu hapus.

MACIEIRA [Brazilian Portuguese]: Eu não quero que minha língua seja extinta.

IVANOV [Russian]: Я не хочу, чтобы мой язык вымер!

MACIEIRA [French]: Je ne veux pas que ma langue disparaisse.

de KORT [English]: I don’t want my language to go extinct.

Coming up after the break: how linguistic differences can lead to bloodshed:

WEBER: Many people died in the war, which easily could have been avoided.

How language affects thinking:

BORODITSKY: There are certainly claims about types of thinking that become very hard without language.

And: is the European Union our modern-day Tower of Babel?

WEBER: Yeah, I think so.

MUSTAK [Bahasa Malaysian]: Sebentar lagi …

MACIEIRA [French]: Ca, ça vient tout de suite …

IVANOV [Russian]: Далее в программе Радио Фриканомики.

MUSTAK [Bahasa Malaysian]: … dalam Radio Freakonomics.

MACIERA [French]: … sur la Radio Freakonomics.

That’s coming up next, on Freakonomics Radio.

* * *

We’ve been talking about talking — how it came to be that 7-plus billion people on Earth 1.0 speak some 7,000 different languages. And the simple fact that a great many of us can’t understand the most basic thing that someone else may be saying:

MACIEIRA [French]: Excusez-moi, où sont les toilettes?

AMORIM [Portugal Portuguese]: Desculpe…

KANG [Korean]: 저기요 …

AMORIM [Portugal Portuguese]: … pode dizer-me onde é a casa de banho?

KANG [Korean]: … 화장실 어디 있어요?

MUSTAK [Bahasa Malaysian]: Tumpang tanya, tandas kat mana?

MACIEIRA [Brazilian Portuguese]: Da licença, aonde fica o banheiro?

VIDAL [Filipino]: Puede pong magtanong, nasaan po ang banyo?

IVANOV [Russian]: Извините, где тут туалет?

de KORT [English]: Excuse me, where’s the bathroom?

You may be tempted to think — hey, wait a minute, why don’t we just standardize our language? Well, that can get messy real fast:

WEBER: The bloodiest example actually probably over the course of this century is the Sri Lanka war.

That is the economist Shlomo Weber:

WEBER: There was a linguistic war between two groups of people.

For some 2,000 years, two major ethno-linguistic groups — the Sinhalese and the Tamil — had co-existed, relatively peacefully, on an island in South Asia now known as Sri Lanka. Over time, it was colonized by the Portuguese, the Dutch, and the British. The British gave it up in 1948; and in 1956 …

WEBER: What happened is that Sinhalese majority tried to impose making the language of the majority the only official language of the country.

The Sinhalese-led government introduced the Sinhala-Only Act, which Tamil leaders called “a form of apartheid.” Tamil protests turned violent, and that violence begat a full-fledged civil war that would last 26 years. Tens of thousands of people died.

WEBER: The reality is that the situation was already tense, but the intensity of the conflict would have been much lower than without this Sinhala-Only Act. The price is just staggering. So many people died in the war, which easily could have been avoided.

Tamil was ultimately accorded official status, alongside Sinhalese. It still took a long time for things to settle down. In 2011, a reconciliation commission recommended that schoolchildren be taught in both Tamil and Sinhalese. “It is language that unifies and binds a nation,” their report read. “It is imperative that the official-languages policy is implemented in an effective manner to promote understanding, diversity, and national integration.” So: does language bind us, or divide us? Short answer: both.

BORODITSKY: I will say that tribalism develops very quickly.

That’s Lera Boroditsky, from U.C.-San Diego. She has found linguistic tribalism in many precincts.

BORODITSKY: If you join an online community, for example — let’s say a new TV show that comes out. Within a few weeks, there will be phrases, vocabulary items, and memes that can only be understood by people who participate in that linguistic community and very quickly [it] becomes so that new people who join the community — the newbies — are, at least initially, excluded because they don’t know how to use that set of vocabulary items correctly and they have to spend some time learning.

Offline communities have the same tendencies.

BORODITSKY: They show a lot of these very common patterns of quick innovation, quick change — which you get in languages all over the world — and a desire to differentiate. People, on the one hand, want to communicate with one another but on the other hand, they want to have a shibboleth — they want to have some way of revealing who really belongs and who doesn’t belong.

This is called signaling theory.

WEBER: Absolutely!

DUBNER: I’m curious to know, from your perspective as an economist, how much value people place on their language in terms of identity and not just usefulness?

WEBER: Religion and language [are the] two most important factors in identifying, people identify their selves. People’s attachment to the language is a symbol of their identity and a desire for independence. Everywhere and every case the importance of the language, attachment to language, and importance of education of language of your own children and this language is very difficult to overestimate.

McWHORTER: Since we have 7,000 different languages, one of the reasons that you might want to preserve them is that having a separate language in the world that we know is part of being a culture.

John McWhorter again.

McWHORTER: You don’t absolutely need one because I don’t want to say that an American Jewish person isn’t really Jewish unless they speak fluent Yiddish or Hebrew. But it certainly does help. When you don’t have the languages, it’s easier for the culture to disappear. It is partly our fondness, our acceptance of diversity, which is a major philosophical advance over the way people felt as recently as say 70 or 80 years ago.

Again, the question becomes: how much linguistic diversity is the “right” amount? Here’s one answer: enough for anyone to feel connected to the community of their choice, but not so much as to hamper trade or start a war. It’s also worth thinking about the benefits of linguistic diversity, and of language generally, that go beyond the utilitarian.

BORODITSKY: There are certainly claims about types of thinking that become very hard without language or become unlikely without language.

Boroditsky, you may recall, is a cognitive scientist.

BORODITSKY: I do a lot of work on language and cognition — how the languages we speak shape the way we think.

So, if you take bilinguals, for instance …

BORODITSKY: You’ll see that they think differently from the monolinguals of any of their languages and they do it even when they’re not speaking the language of interest.

She’s studied this phenomenon in the lab.

BORODITSKY: We bring people in and we teach them new little mini languages and then we measure — in non-linguistic tasks — how they’ve changed the way that they think.

Indonesian, for instance, doesn’t include tenses, like English does. So the researchers tested whether teaching Indonesian speakers some English would change how they thought about time.

BORODITSKY: We would show people pictures of someone, for example, about to kick a ball, in the process of kicking a ball, or having just kicked the ball, and then test their memory.

English monolinguals were better than Indonesian monolinguals at remembering information about time — that is, when the ball was kicked.

BORODITSKY: But then when you look at bilinguals — Indonesian/English bilinguals — they start to shift. Indonesian/English bilinguals are better than monolingual Indonesian speakers at remembering when something happened and they also start to value that information more when deciding what’s more similar.

There’s some debate over the reliability — and significance — of this sort of lab finding.