#the rest can of it can choke

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

LEWIS, quali reaction - MONACO GP 24

#thanks mercedes for nothing#i will now erase all the hope u gave me yesterday#still praying for a lewis success obv#the rest can of it can choke#lewis hamilton#f1#monaco gp 2024#jo.gif

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mathias being sunshine in human form

#the best 2 seconds of the episode#the rest of the episode can choke#rykter#rykter nrk#teo tomczuk#rykter spoilers#3x06

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

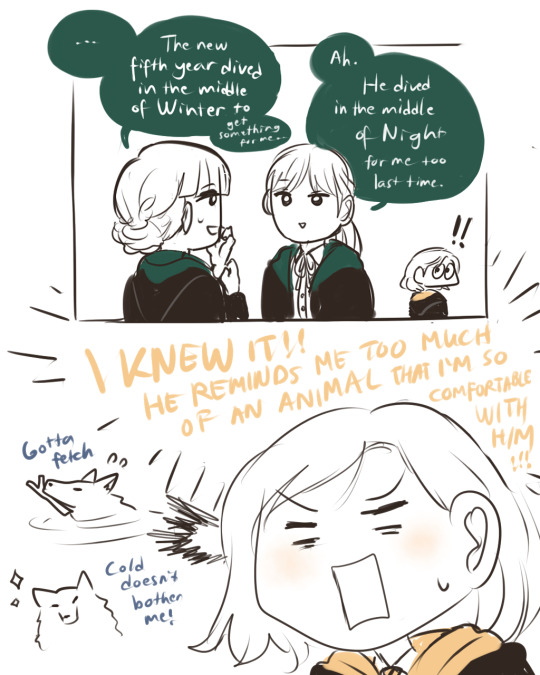

i thought / m a n / these girls are quite heartless 🤣 when i accepted the quest at /clearly/ inconvenient time to swim & dive

#the lake was like a pool of darkness at night; and i had to get him swim to the center of it; so far away from the surface#it was so scary; as if he will just disappear & never come back to the surface once i let him dive in; to the darkness#poppy sweeting#hogwarts legacy#hogwarts legacy fanart#hogwarts legacy mc#fanart#grace pinch smedley#The Lost Astrolabe#Nerida Roberts#Merky Depths#animagus has no business having to be so hard to achieve........... ; i would want to turn to animals too..........#but the process is sooooooo elaborate........ ; i would choke a thousand times on the mandrake leaf ;#& one of them would get to the wrong pipe and end me before i achieve anything ...............................#anyhow imagining everyone as animals is just like what floyd does; as a mermaid; giving everyone nicknames as sea creatures#there was a manga where everyone can turn into animals but this one boy that has social difficulty i think; i wonder if i can find it again#i think it had not been updated for the longest time#augh also reminds me of 0ki from 0kami#i envy him and the 0ina people who can transform into dogs#i am off to watch the rest of br1dgeton episodes of season 3

269 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think Aether gives Dew one of his rings when he leaves on tour.

It's too big for him to wear, obviously, so Dew keeps it in his pocket. Uses it like a worry stone. But, just before it's time to start the first show, Dew realizes his uniform doesn't have pockets. It's embarassing, but he panics a little. Just a moment of overwhelm when the realization hits. Has to stop and catch his breath, swallow back the bile that rises in his throat.

Dew places that simple silver band on his vanity before he puts his helmet on, and just looking at it breaks his heart a little. The thought of leaving it behind hurts even more. Dew puts a hand on his chest, tries to center himself, and -

His necklace.

He feels it through his uniform, the press of the metal into his skin, and it feels like relief. Pulls down his balaclava so he can pull out the jewelry, and for the first time since Aether gifted it to him Dew unclasps the chain. Takes the necklace off just long enough to slide the ring on beside his pendant. He feels weirdly naked without it, hates having it off, and the second he secures it around his neck again he feels miles better.

Dew looks at the two pieces of metal next to each other and smiles. Happy that, in even this small way, Aether will still be out there with him.

#i really miss them you guys can you tell#dew takes a picture of the necklace with the ring on it to send to aether#who immediately gets choked up like the bog softie he is (at least when it comes to dew)#dew leaves it on the chain for the rest of the tour

358 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Keir paused at the threshold as the doors opened on a phantom wind. He said to Rhys, perhaps the closest he’d come to asking for permission to leave, “Lord Thanatos is having … difficulties with his daughter again. He requires my assistance.” Rhys only waved a hand, as if he hadn’t just yielded our city to the male.”

lord thanatos’s daughter is my roman empire actually. i know rhysand had his hands full what with hybern and eris and of course grossly betraying mor’s trust plus publicly blindsiding and humiliating her and all but there was zero thought from anyone about what keir, well known daughter torturer famous for torturing daughters could possibly be leaving that room to do. not even from supposedly empathetic feyre? the same one who held a dying faerie’s hand in book one? like you’ve just brokered this deal with keir so obviously i’m not expecting you to kick down the door and save her but she doesn’t even get an afterthought. ouch.

#rip lord thanatos’s daughter you were a throwaway line and i think about you more than sarah j maas ever did or will#anti inner circle#they really don’t give a fuck about anyone outside velaris#mor gets a pass for not expressing concern because she was just betrayed and is having Flashbacks#but the rest of them in the room can choke#anti azriel#anti rhysand#feyre critical#azriel critical#lord thanatos’s daughter#lord thanatos#acowar

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hudutsuz Sevda 18. Bölüm

Prompt: "No rest in hospital"

source

#hudutsuz sevda#deniz can aktaş#no rest in hospital#turkish#turkish series#whump#male whump#whumpedit#fight#attacked#hit#pain#choked#comfort#face touching#pale#weak#supported#wound care#hospital

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another thing yellowjackets did for me on these last two episodes was my complete 180 on teen Travis. After seeing the pain and trauma he went through with his baby brother I will not accept any slander against him and I'm excited to see where his character goes from here (hopeful)

#travis and ben the only men that i care about the rest can choke#yellowjackets#yellowjackets spoilers#travis martinez

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

sometimes i get the urge to make a gifset about the love the group showed towards brian and how it helped him survive but then I remember they mostly fucking used and abused him so I shan't

#justin is the exception#alongside em and then teddy's friendship as it grew#jennifer is also exempt#the rest can choke

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summerfest day 3 - GHOST

On the hoary street outside Aventus’ house, the children are throwing snowballs.

It’s snowed thick the last few days, only coming to a stop late this afternoon, so that the cobble of the road is entirely hidden; the younger ones, all a little older than it feels like they should be, are shin-deep in it, wading with some difficulty, clothes freezing wet and shoes probably soaked through. It’s the proper kind of snow, clean and crisp and cold to the bone. It lies smooth and flat where it hasn’t been walked through and most of the streets visible from the upstairs windows still haven’t been shovelled clear. There’s meant to be a market today, but after this weather – roads barely traversable unless people start rustling up sledges - it’s doubtful it’ll go through. It happens. This time of year you need to keep your storeroom well stocked, else you’re shit out of luck.

(Once, there were no storerooms; Torr couldn’t tuck themself away until the blustering died down. He’d wear seven worn-thin layers and stick his fingers in his mouth when they started hurting and if it got really bad he’d find somewhere with Griss and Kyrri and Katla and whoever else he could grab and he’d beat down the door of whoever was least sick of his face at the time. The Cornerclub, if he thought it was worth appealing to Ambarys’ better sensibilities; the temples dotted around the city, though some of them were never very helpful at the best of times. They waited a blizzard out on Eirmund’s kitchen floor, once. Broke into a few cellars, a few abandoned buildings, a shop. It’s lucky they weren’t arrested twice as often as they were. They think they got by mostly on luck, some days.)

It's pretty, if nothing else; there’s nobody else out on the streets yet so it’s just the gaggle of kids in their tatty coats and cloaks and the ends of their tunics wet, breath misting in the air so visible it’s practically crystallised, shrieking and ducking and hurling damp handfuls of snow at each other, loose-packed and crumbling. It hits the walls, sometimes, and sticks dripping between the stones; seeps through their gloves, through their hose, and Torr doesn’t remind them to worry about frostbite because they know and he knows they know, but he thinks about it. Their own hands are still scarred, fingertips ever-flushed, knuckles tough and pitted. It’s hard to remember that things have changed, in some ways. Harder to remember they were ever different, in others.

They’re posted up watching against the chilled stone wall, hood pulled over their head to shield them some from the cold, hands tucked up into the sleeves of their thick wool tunic. (It’s nice. Bluish-purple – Babette picked it out, they think.) The kids are all yelling their heads off, which they suppose the neighbours must have gotten used to. Ambarys is stumbling like a newborn deer through the snow; Griss is darting this way and that, her red skirt fluttering like a flag behind her; Skygna has Gellir on her shoulders, a lump of snow held high in one hand and the other holding onto her head, directing her to charge around lopsidedly. A trio of the newer kids – they’ve been appearing more often, Katla said, since the fighting started, and Torr’s still not entirely clear on which is which – are trying to pile up a crumbling snow wall. Skrauti keeps careful to the porch, mindful of his foot and realistic about the strength of his boots and the real utility of his crutches in that sort of terrain, but he ducks around corners and keeps neatly compacted snowballs piled up in his arms. He darts around the corner, throws one that dramatically misses anyone that it might have been aimed at, and lurches out of view again before anyone can try to get him back. Gellir is bellowing, his little face bright as the sun. Skygna is laughing. She always used to be so serious.

So much has changed. So much has stayed the same. Same clothes, some of them. Same people, mostly. Torr watches, leaning against the cold stone wall, and tries to find familiarity in it. Fails.

(It should be familiar. They used to play like this all the time – Windhelm’s certainly got the weather for it, coated in snow for the better part of the year and not all that much else to do about it; the kids would sneak up on him, or on each other, try to dump a damp handful down the backs of their tunics or grind it into their hair. Katla always tried to get it straight in the eyes. Torr remembers back when Skrauti was new, how he managed to smash a hard-packed snowball through one of the rare glass windows in the Grey Quarter, how he damn near cried with guilt afterwards until Torr promised they’d scrounge up the money to pay for it to be fixed. Torr remembers how Chukka down the docks tried to figure out how to lob snow at them with her tail even though it didn’t have half the dexterity for it. Torr remembers Katla shovelling snow down her throat in response to some stupid dare and then shoving Talres’ face in it when he laughed. Torr remembers, Torr remembers, Torr remembers; but it’s like that’s all he knows how to do. Like he’s slotting it away in the shelves of nostalgia as it’s happening. Like he’s not really here.)

(He isn’t. Not really. Not like he’s supposed to be. Once, they would have been the one to start it, putting snow down Katla’s dress, on Talres’ arm, in Griss’ hair; it kept them all laughing, kept them active, kept them distracted. They were the best at those games, unbeatable, though since half their opponents were half their age having the best arm and the quickest dodge probably wasn’t much to brag about. They remember it all but they’re still leaning statue-still against the wall; trying to move feels like an imitation, unreal. None of it feels real. Every time Torr comes back here they feel like they’re dressing up in their own skin, carving the blood off their palms, trying so hard not to seem like they’re pretending. He loves the kids – he does, he does, he does; he would do anything in the fucking world for them. There’s not much left that he hasn’t already done. But there’s little comfort to be found here, these days, feeling slow and stagnant and ill-fitting. They want him here, though, all the same. So he visits. And he tries not to feel like he’s lying.)

Torr is lost, as he usually is here, in thought (he can’t get away from it – he steps through Windhelm’s ancient gates and falls backwards through time, falls backwards into his own head), so he’s not expecting impact, sudden and sharp, against his right shoulder. Just under the clavicle. Their clothes are thicker-softer-better here than they ever used to be, but even so they can feel the freezing shock against the scar tissue knotted over their joint – they’re reacting before they even begin to think about it –

Their head catches up to their body before they actually put a hand on their knife, but not before they’ve flinched for it, shoulders curled in, sinking their weight low, one foot shifting agitatedly against the powder-pit of the snow; then Torr blinks, remembers himself, remembers when he is and where he is and that there is a world past the sudden snap of vigilance singing through the thundering of his blood. Blinks again. Looks, over the muddy-trodden surface of the sparkling snow, to Griss; who stands with one arm still raised and one side of a smile pinned on. It seems to be caught in place halfway through slipping away. There is snow on Torr’s jacket sleeve.

(Once, keeping her smile in place was the entire pared-down goal of his life; Torr spares a moment to hate himself, acutely and utterly. Then he moves on.)

Torr knows the steps for this game; knows what to do; knows what they would have done, though not why it used to be so easy, or why it’s so hard now. Griss looks grimacingly like she’s about to apologise for startling them, which is so horrendously not how they talk to one another that the idea stings. Torr crouches – all their muscles still coiled, chest held tight, very unhelpful – to dig a handful of snow from the ground at their feet and fling it in her vague direction. She yelps and dodges with ease, but it fixes the look on her face; she sticks her tongue out at him and ducks down to build up another arsenal, and Torr shakes his head ache-inducingly hard and tries as best he can to wrangle his attention to here and now. The snow is painfully cold against his ungloved hand, but it kind of helps. Makes him feel like he’s here.

When Griss hurls another projectile at him, he has at least the presence of mind to sidestep; she cackles delightedly, and he smiles, thin and dirty-cold as the dusting of snow on his shoulder.

#not. enormously happy with this one#I messed with it so much I can't stand to read it anymore lol. it was way longer but I cut the entire back half bc it felt too...#rambly. pointless. I wanted it neater#I would have liked to refine those later bits and try to make it work but I would have needed more time to let it sit#ah well! c'est la vie! I'm sure I can recycle the rest (it's torr choking on guilt while eating. then choking on guilt while having#the barest bones conversation in the world)#(you get the gist)#tesfest24#oc tag#torr#my writing#fay writes#microfic#the elder scrolls#tesblr#skyrim#tes

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

In a World Without Heroes: deleted scene

Author's note: The Saturday morning interview scene between Grantaire and Enjolras in chapter 8 originally started from Grantaire's arrival and was intended to go through the events of the scene that has since replaced it. This scene ended up being replaced partly because the characterizations weren't panning out how I wanted (as you see by the end) and partly because it was dragging the scene/fic. Yes, it was good background for the reader, but ultimately (as Grantaire now comments in the replacement scene) this is the same thing Enjolras would have said in every interview since his release from prison, so it didn't make sense for Grantaire to be acting like he'd never tuned in for any of Best Boy's television interviews.

Anyway, I'm finally sharing it here because it's the backstory behind Mabeuf's Manhattan Autonomous Zone and Enjolras's arrest, and also I've been meaning to for uhhhhh two years. Enjoy.

By the time Grantaire texts that he’s on his way, Enjolras feels very nearly relieved.

He’d spent Friday evening catching up on what little cleaning has been neglected since the last time he had a guest — that is to say, since moving in — specifically in order to sleep in Saturday morning, only to find himself wide awake at 9AM with little to do but anticipate the events of the day.

“Hey,” says Grantaire when Enjolras lets him into the building. He’s dressed down from how he usually is at the correctional facility but up from what he wears at the Chinese restaurant, which makes Enjolras feel better about his choice in clothes today.

“Do you mind walking? I’m on the fourth floor.”

There’s hesitation, and Enjolras thinks Grantaire may be about to protest, but when he speaks it’s to say, “Yeah, sure. I haven’t had a leg day in a while.”

“You work out?” asks Enjolras, surprised.

“Nope. Lead the way.”

The walk occurs in silence except for their heavy breathing and a quick apology when someone coming down from the third floor brushes past, and then they’re at the door to Enjolras’s flat.

“Make yourself at home,” he says, heading for the kitchen. “Would you like anything? Tea? Water?”

“Seltzer if you’ve got it, water if you don’t.”

Seltzer. It’s what Grantaire has ordered both times they were out, too, and Enjolras makes a note that he should pick some up beforehand if they do this again.

There’s no reason for them to do this again, of course: with this past week’s interview completed, they’re over halfway finished with the collaborative part of the book, and there will be no reason for them to be spending time with one another anymore. Even with Enjolras’s resolution not to pursue a relationship with Grantaire, the prospect of their burgeoning friendship coming to a halt with the end of their professional correspondence makes Enjolras’s stomach twist.

He re-enters the living room with two waters, placing one on a coaster in front of Grantaire and sipping the other for something to do.

“Thanks,” says Grantaire belatedly. His eyes have been wandering around the flat since Enjolras’s return, and Enjolras wonders what he’s looking for. At last, his attention falls back on Enjolras. “You’re dressed different.”

Enjolras lets his eyebrows quirk in feigned surprise and glances down at himself as though he hadn’t spent fifteen minutes lingering over the decision that morning. When he was merely a law student and the point person for a far-left branch of a tutoring group, Enjolras had had a lot more flexibility in what he wore; since his release from prison, however, his wardrobe has become a rotation of the same six white dress shirts, three tones of neutral trousers, and the occasional matching suit jacket. Even on days when he isn’t working in some capacity or another, Enjolras finds himself dressing as inoffensively as possible in anticipation of someone’s inevitable recognition and the associations to follow. His attire hadn’t been particularly flamboyant before then, but his use for his green rally shirts and blue cozy clothes has certainly fallen to the wayside since.

Today, after nearly five minutes of deliberation, he had settled on a pair of gray-ish jeans, a pale red undershirt, and a blue fitted shirt he’d nearly forgotten that he owned. At the last second before he’d gone down to meet Grantaire Enojlras had pulled a white hoodie over, but already he feels himself overheating in the extra layer.

“Yes, well,” he shrugs, realizing that he should sit and taking the armchair on the far side from where Grantaire has seated himself, “I don’t need to leave today, so I can dress down.”

“That’s what it is! I haven’t seen you in jeans and a shirt without a collar since you got out.” Grantaire’s eyes suddenly narrow. “You aren’t wearing a collared shirt under that, are you?”

Despite his discomfort, Enjolras snorts. “I’m not.”

“I don’t know that I believe you.”

“My deepest condolences.” His retort is met with crinkling at the corners of Grantaire’s eyes before they divert altogether as his attention turns to his lap. Enjolras clears his throat. “I’m not sure I’ve ever seen you in purple. It looks nice.”

Glancing back up, Grantaire’s brows furrow as he looks over his clothes.

“The scarf,” Enjolras clarifies.

The outermost layer of the sheer material is picked up and rubbed under close scrutiny between Grantaire’s fingers. “I guess? I thought it was gray when I grabbed it this morning, but in this lighting it looks blue to me.”

The scarf is definitely purple, but it isn’t worth disputing. “It looks nice,” Enjolras instead repeats.

“Well cree, thanks.”

Taking a deep breath, Enjolras decides to put an end to the stall tactics. “The interview, then? How do you want to do this?”

“Uh. I was thinking just kinda like at the facility? You say what you want, and I respond and ask questions as they arise. Obviously no notetaking or recordings or anything, so it’ll pretty much be like a normal conversation that I know some of the answers to already.”

Nothing about it feels like a normal conversation, but Enjolras braces himself nevertheless. “Let’s begin, then.”

“You sure?” There’s a dubious crinkle between Grantaire’s eyebrows. “We can shoot the shit for a while longer if you want, let you get comfortable and whatnot.”

Resting his hands carefully over his knees, Enjolras arranges his features into a neutral façade. “I’m sure.”

Grantaire sighs deeply, a hand skating over his scarf and jerking the front back from his hairline as he scratches the back of his head. “Okay then. Well, where would you say it all started?”

He’s about to fall back on the polite clarifying tactics he’d been drilled on for televised interviews before when he realizes that he doesn’t have to. “Where what all started?”

Apparently Grantaire holds a similar amount of compunction toward his professionalism. “I dunno, whatever you want. The rally? Broletariat? Activism in general?”

Enjolras has managed to avoid shining a spotlight on his childhood this long, and his parents have made it clear that they have no interest in having their names attached to any of this, but beginning at the rally would feel like starting a sentence in the middle of a phrase. “Combeferre, Courfeyrac, and I have known each other since we were young,” he says, finally settling for their indoctrination to the betterment of humanity as a promising starting place, “and we all were accepted to and attended Columbia for undergrad and stayed for our graduate degrees. None of us were from New York City, and while we were studying, we saw a need in the local community for support, and we started up an afterschool tutoring group in conjunction with Barnard College’s urban teaching program. I believe they’re still running, though I lost touch with them while I was away.”

“On the road,” nods Grantaire.

“In jail.” There’s no use dancing around it now: if Enjolras can’t say it in front of Grantaire, who else is there?

“Right, that too.” Grantaire’s body is draped over the corner of Enjolras’s couch casually enough, but there’s a stiffness in his posturing and the way he rubs the tip of his thumb back and forth along the side of his index finger that makes Enjolras think he’s uncomfortable.

“The Broletariat’s inception was nearly accidental,” he continues. “Feuilly worked in the afterschool program at one of the schools we operated out of, and we got to discussing education law one day while he was packing up and I was waiting on a pupil and agreed to continue the conversation as a secondary location at a later date. It was never official, but it did become regular: once work and classes let out, more and more of us met under the guise of lesson planning or studying or spending time with friends, while under it all we were organizing.”

“Organizing what?”

Enjolras shakes his head. “At the time, we’d had no way of knowing. We could feel unrest building toward something, and we made sure that the channels of communication were open and to keep up with the news and share resources and to — to be prepared for any eventualities,” he says.

“Enjolras, I was there.”

“It occurs to me that announcing our weapons stores to the general public may not go over well.”

“Good thing you’re not announcing it to the general public, then.”

Enjolras sighs. “We were ready for anything, and one day, ‘anything’ finally had a name: Jean-Charles Mabeuf.

“Before his arrest, Mabeuf had been a churchwarden at a local church, a respected member of his community. His friends said he had an expansive collection of books and was trying to grow indigo to start a small business.”

“Does indigo grow well in New York City?” This time, it seems like a question Grantaire genuinely doesn’t know the answer to.

“Evidently not. At the time of his arrest, he was several months behind on rent, had nothing in his fridge, and his famous book collection had dwindled to hardly anything: he was destitute.”

“Tough break.”

Enjolras shoots a sharp look at Grantaire. “Do you remember what happened to him?”

“The prison left him to die of treatable causes, what more is there to know?”

“His landlord took him to court for the missing rent; Mabeuf had already fallen ill and couldn’t make it, and the judge issued a bench warrant. He was arrested for being sick and poor.”

“Well, I’m seeing why I would selectively have culled that bit if I heard it.”

Enjolras feels his nostrils flare at the flippancy, but a small part of his mind reminds him that the Grantaire in front of him is not the Grantaire who drank his way through the entire rebellion and every strategy meeting leading up to it. “I would be surprised if you hadn’t: his arrest hardly made the news. I’m told that his church was in the process of arranging some care package or another for him, but that most likely would have been the end of it if not for the pneumonia.”

Now comes the part that the news and everyone knows: all of the symptoms were recorded upon his intake, but no action was taken to treat him. Mabeuf remained in jail as he waited for his new court date, complaining every day of chest pains and requesting to be moved to the med pod. He was never moved, and on 1 June, at eighty years old, Jean-Charles François Mabeuf was found dead in his cell.

“With the release of the coroner’s report, his church community took to the web for Justice for Mabeuf. The movement against the privatized prison system had already existed and was merely on the backburners, and it seemed like the time for change had finally come.”

“Okay, so wait,” Grantaire interrupts. “I was a bit hazy on the details at the time, but I mostly chalked that up to a whole slew of substances combined with a complete and manufactured sense of total apathy; as it would turn out, I am still just as confused.”

Enjolras leans back expectantly in his seat. “About?”

“A couple of points, honestly, but mostly what an armed splinter from a tutoring club expected to happen.”

A fair question. “I was supposed to go into education law.”

Grantaire blinks. “Okay?”

“There’s no special concentration in legal programs to choose one’s specialization: you take the relevant courses offered, intern with firms that handle the sorts of cases you’re interested in, and once you pass the bar, pursue that area.”

“Got it.”

“Once you start looking into the way the United States education system is set up, it becomes immediately evident how inextricably linked all of these pieces are: children are born in low-income communities. Low income means that the property taxes that fund the schools amount to less, leading to fewer resources and higher drop-out rates. The wages in positions for unskilled labor aren’t enough to live on, so people either pick up more and more jobs until they’ve worked themselves to the bone and, quite often, to the point of their bodies breaking down, at which point the failings of the health system become painfully apparent; are turned out onto the streets, which exposes the failings of our government’s housing system and its rotting capitalist firmament; or turn to more lucrative but less legal job opportunities.

“Two of these are arrestable offenses disproportionately targeted communities of color, and the third skips past those steps directly to killing the dime-a-dozen wage slave.”

Grantaire stares at the coffee table in silence for long enough that Enjolras begins to suspect that he may not have been paying any attention at all before his brows finally furrow and he looks back up at Enjolras. “So what were you expecting to happen?”

He sighs. “I couldn’t rightly say what we expected to happen, but the goal was to draw national attention to any one of these points. If something gave, we thought that the whole system might crash down around it. Exposing the for-profit prison industrial complex as the corrupt, predatory, outdated, inherently racist system it is … it felt self-evident. The whole system is broken, let’s build a new one together that serves all of its citizens equally and doesn’t feature intentional loopholes for legalized slavery.”

Grantaire is quiet for a long time before he finally asks, almost too quietly for Enjolras to hear, “When did you realize it wasn’t going to work?”

‘When’ indeed. Enjolras makes no motion to answer. When had he known? Has he ever known? Perhaps he still doesn’t. “It still might,” is what he finally says. “We haven’t failed yet.”

Grantaire looks affronted. “You almost died, Enjolras.”

“I didn’t."

#in a world without heroes#shitposting sometimes writes#you can see why it got cut/rewritten#and I'm all for an iceberg#but it did annoy me that I couldn't find any natural way to explain how the MMAZ worked#oh I guess it still isn't addressed here#but there were a couple of meet-up points around the island that people were gathering#and they were all going to meet and converge on the [courthouse?] way way south of the island aka the location of MMAZ#but riot police and national guard ended up heading off all of the routes (I had a specific choke-point noted in my outline somewhere)#so the crew that was already at MMAZ ended up getting strangles without reinforcements or resources#and then the waves of tear gas and rubber bullets started#and the rest is IaWWH canon

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

D3: soulmates for @bsd_rpw_2024

#bsdrpw2024#fyoatsu#fyodor#atsushi#bsd#cw choking#cant get away from the rest string of fate imagery now can i

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anyways… fuck McLaren

#sorry Lando and Oscar but I’m manifesting double dnfs for the rest of the season#Zac brown can choke#f1#formula 1#anti mclaren#miami gp 2024

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

dude this whole fucking part (arc?? idk) with all the wards is sooo interesting 2 me. i love these fucking guys sm. clockblocker ily

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

dear God restrain me from knocking out the teeth of every one of Pyeong Hwa's fake ass colleagues bc you know i will do it. you know i will do it Lord you have seen me attempt it before

#tv: king the land#king the land#go won hee#kim jae won#kdrama#local gay watches KTL (and gets diabetes in the process).txt#local gay watches k-dramas.txt#Ro Woon the realest mf*cker in this place. the rest of you can choke and i'm not taking that back#hypocrites the lot of them. f*ck that

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

i should make a post about my kaeya headcanons. particularly my hcs about his childhood

#like. early childhood. pre ragnvindrs#i dont think he was physically abused or starving. though i do think his life and the way his father parented him was less than ideal#i think that he could speak basic common when he got left in mondstadt and learned the rest there#and had an accent he nearly completely got rid of#nearly because i like to think that theres some words or syllables that still sound vaguely ''off'' but only if ur paying close attention#but no one really is#i think he was quiet and kept to himself when he arrived but wasnt a nervous wreck like i see depicted so often#you can BET he was freaking out. but like that's biting his own hand to choke down sobs late at night things. never in front of anyone#oh i also think he was around 8 or 9#damn it lena save it for the post#my posts#kaeyaposting

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not to mention Kpop on main but...

Man, I'm genuinely sad at what happened/is happening with Seunghan, he literally did not deserve any of this. I genuinely hope he and the other members of Riize make it out okay because what the fuck.

#If he debuts solo I'm going all in honestly fuck everyone who participated in subjecting him and the rest of the members to this#Generally I focus on the music and don't pay attention to fandom bullshit/or the actual members tbh#(IE why despite being into MCR for nigh on 10 years I only know 2 band members names and would only be able to recognize Gerard on sight)#I completely understand his decision to quit after being subjected to so much bullying and death threats#But this is genuinely so sad for him and the other members of Riize who wanted him back#He literally did NOTHING wrong at all#But also I have a hard time believing that any effort or planning went into his return to protect him#SM disintegrated like wet toilet paper#Fuck the “fans” and fuck the companies that enable this bullshit#My energy is the same for anyone who's getting insane backlash for just being human holy hell but since this is about a specific situation#Anyway personally I support Seunghan in whatever he wants to do#As well as the other members themselves#The company who failed to handle this well at all and the so called fans who sent death threats and funeral wreaths can all choke#I wish Seunghan all the best#As well as Shotaro - Eunseok - Sungchan - Wonbin - Sohee and Anton#Like the only reason I was going to check out Riize's music was because he was coming back#but now I won't which sucks because the other members did nothing wrong but I can't in good conscious you know

5 notes

·

View notes