#the reality of having psychologically complex characters in a narrative is that they will resemble real people from your life

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I had this drafted around elaingate, and now that my fever has finally broken, I can piece together my thoughts on the absurdity that is this fandom and the rhys week tamlin and rhys' sister piece debacle. Because, of course, no one has learned anything from elaingate to now, and it's time to wake up and smell the coffee.

If there's one thing about this fanbase that I've noticed so far, it's that people will accidentally tell you exactly who they are in the most embarrassing way possible. What's the main takeaway in the overlap of the rhys week drama and elaingate?

Art, purity culture, and "victimhood." And people deciding who does and doesn't get to fall under the latter.

The thing that I appreciate about elaingate (and I guess Rhysgate??) happening is that it outs the people in this fanbase who don't see art that doesn't cater to them as having same rights as the art they do like/are comfortable with to be celebrated and appreciated in a community event about a character.

It outs people who only care about "protecting survivors" if their trauma conveniently matches what SJM believes to be abuse or trauma. It outs people as having the same performative inclinations of "protecting victims" as pro forced-birth/anti-choice pundits do. Rhysand’s sister, a nameless character, is the perfect "victim" to create an upheaval about because, like Elain, no one actually has to sacrifice anything or do any difficult self-reflection because fictional characters will never ask anything of you.

Remember this quote from Pastor David Barnhart? It's pretty relevant.

"The unborn are a convenient group of people to advocate for. They never make demands of you; they are morally uncomplicated, unlike the incarcerated, addicted, or the chronically poor; they don’t resent your condescension or complain that you are not politically correct; unlike widows, they don’t ask you to question patriarchy; unlike orphans, they don’t need money, education, or childcare; unlike aliens, they don’t bring all that racial, cultural, and religious baggage that you dislike; they allow you to feel good about yourself without any work at creating or maintaining relationships; and when they are born, you can forget about them, because they cease to be unborn. You can love the unborn and advocate for them without substantially challenging your own wealth, power, or privilege without re-imagining social structures, apologizing, or making reparations to anyone. They are, in short, the perfect people to love if you want to claim you love Jesus, but actually dislike people who breathe. Prisoners? Immigrants? The sick? The poor? Widows? Orphans? All the groups that are specifically mentioned in the Bible? They all get thrown under the bus for the unborn."

Rhys' sister and Elain are the perfect vehicle for people to feel like they're "morally just" for "protecting" from...Tamlin. And people creating specific dynamics between these fictional characters, too, I guess. Because they're evil or whatever, I suppose.

"But, Raven!" I'm sure some of you are already scrambling to say. "There are real people in this fandom triggered by Tamlin, and they were hurt! They were so upset/disgusted that they left the fandom because people cared more about fictional ships than their triggers/feelings!"

And I'm going to hold your hand while I say this as a fellow survivor of DV.

No one is responsible for my triggers and caring for my own mental health other than me. And that applies to everyone else in this fanbase, too.

It's my responsibility to curate my online experience as much as possible to my own needs. This space is voluntary to be a part of, and if I no longer feel as though it's conducive to my mental health overall, then yeah, it's probably best for me to leave. Same with everyone else who felt like they shouldn't be in this fandom space because of the elaingate upheaval.

If people rightfully pointing out that this fanbase is extremely conservative and aligned with purity culture and morality policing to the point where art is policed in relation to celebrating a character during their own week is too much for someone because of the narrative around one of the characters involved...then yeah, it sounds like this isn't a good environment for them anyhow.

There's no judgment to be passed on the side rightfully saying this fandom is fucked up, whether or not people are ready to hear that. People saying art that features Tamlin in relation to another character event still has a right to be celebrated so long as that character in the event is depicted has no bearing on whatever real person Tamlin represents to the people that were triggered.

There's only so many ways people can actually be realistically protected from content that triggers them, and tagging is the most consistent way to do so. If the protection of tagging triggering content somehow still isn't enough for people when they might happen upon art depicting a character for one day out of a one-week period maybe is also still too potentially triggering for them, then maybe being in a fandom space isn't the best for their overall mental health and stepping away from it isn't a bad thing.

(And that's all without getting into why its totally fair for peoppe to question how true that ""stance"" of "protecting survivors" actually is when the Elain Week event's tagging system is consistently ignored and not used to actually protect survivors from triggering content. It's interesting how people spent more time angry at people who were adamant about the right to celebrate art instead of the event itself for not having a remotely thorough tagging system. How are you "protecting survivors" from triggering content, including yourself as the event runner, without tagging anything from character names to triggering content/events someone might view? Let's not forget how wide-spread triggers are, too. People have trigger warnings for content involving eyes or spiders due to phobias, not just events that they might have personally experienced, like violence.)

Back to the main point, however.

Issues like these out people as not understanding that creativity means bending the rules of canon however you want, because these are characters, not real people. But real people are making this art, and its value and worthiness of being celebrated is not up to anyone's personal discretion (including event runners) even in situations of discomfort.

It's a shame that the first upheaval happened regarding Elain since she's rarely appreciated outside of her ships anyway, but this Hell-hole of a fandom has had this coming for a while now. This is an absurdly conservative, rigid-to-canon, puritannical fandom, and unfortunately, Elain Week was the match that started this fire.

As a writer, I'm always going to have a hard stance on this because appreciating and celebrating art does not end where my personal likes and comforts do. Appreciation does not look the same for everyone, and just because it's not how you would personally celebrate a character does not mean it stops being appreciation or celebration. Your preferences are not and never will be the end-all-be-all of artistic appreciation in a fandom space. If you don’t see that, the block button is right there, and I've been using it very liberally.

You either stand for all of fandom integrity and creative works, or you don't deserve to be in this space. And I will very happily remove you from my space here since, as far as I'm concerned, you don't deserve to be in mine, either.

#elaingate#acotar#rhysgate#is rhysgate a thing??#idk im making it a thing if it isn’t#anyway i hope some of you wake up and go outside#anti acotar#anti acotar fandom#acotar fandom critical#acotar critical#fandom wank#you arent a better person for not liking Tamlin or giving the things he did in a fictional narrative the same seriousness#as abuse happening to a real person with real feelings#the reality of having psychologically complex characters in a narrative is that they will resemble real people from your life#but these characters are not real and cannot hurt you and did not hurt you unlike the real person they remind you of#and projecting onto them doesn’t change anything for you#but a lot of you are not ready to have that conversation yet

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jack Vessalius as a Symbol for Depression

Ever since I first read PandoraHearts, I have interpreted Jack Vessalius as at least a partial symbolic representation of depression, especially in his relationship with Oz.

(Skip to “keep reading” to go straight to the analysis; this beginning portion is little more than a disclaimer.)

Jack is a complex, fascinating character, and it is precisely due to this that I believe any number of interpretations regarding him contain merit. Whether you view Jack as an abuser, a manifestation of mental illness, or an extraordinarily-written character that does not require a figurative understanding to be interesting, I think this is valid.

I am saying this first and foremost because I want to be clear: this is not a persuasive essay. I am not trying to change anybody’s minds about liking or disliking Jack Vessalius, nor am I trying to devalue any other interpretations of this extremely nuanced character. Some points may be a bit vague and connections disjointed, though I attempted to minimize this. Any discussion of mental illness and abuse is based on either my personal experiences or those of people I know. I do not intend to offend anybody.

This post is simply the product of years of disorganized yet in-depth thoughts about this concept. I hope some of you will be interested.

Major spoilers for the entire manga below the cut. Manga panels are from the Fallen Syndicate fan translation. This...is going to get very long.

Emotional Abuse

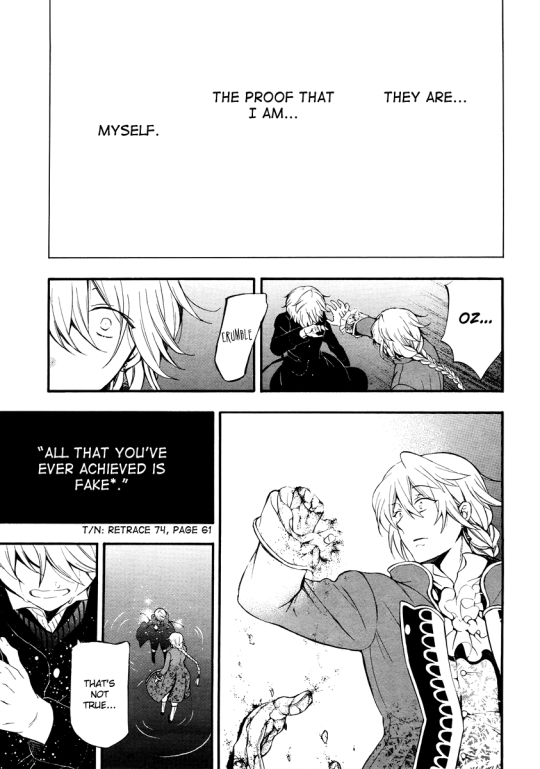

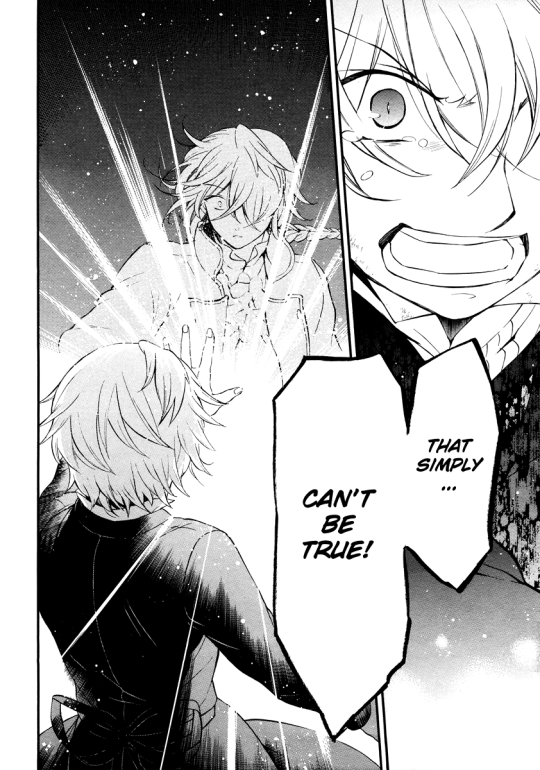

Jack exists within Oz’s mind. When these two interact, it almost always occurs within Oz’s head, providing every conversation with an inherently emotional and symbolic element.

Jack initially appears to Oz as an unknown but crucial figure. Whether he is trustworthy or even harmful remains to be seen, but his input is necessary. He is the only insight Oz has into his lost memories; he knows something Oz does not. Oz is suffering an identity crisis, realizing he has endured something he does not completely understand, something that could potentially change his entire life once he does understand it. And yet, this mysterious voice within his head understands it.

This desperation makes it almost irrelevant whether Jack is credible, whether his advice is well-intentioned. Normally a rather cynical and distrusting young man, Oz follows Jack from the beginning despite wanting answers. He does indeed receive answers, but they are perhaps not quite what he bargained for, in more ways than one.

Once Jack’s true nature is revealed, the extent to which he has used Oz’s memories and emotions against him becomes apparent. Jack does present Oz with new insights into his experiences, but he only ever provides Oz with enough information to convince him to act a certain way. He never willingly gives a fair, all-encompassing portrayal of an event from Oz’s past. He manipulates Oz’s perceptions of his memories to fit a particular emotional narrative, one that is inevitably perplexing and demeaning to Oz.

This bears a resemblance to the way depression warps how we view past events. When we look back at our experiences, we don’t see the entire picture--though we are convinced that we may. We see a skewed version of an incident that actually occurred. Perhaps this incident proves little to nothing about ourselves in reality, but viewed through the lens of depression, everything about it seems to scream that we are useless. And it is nearly impossible to try and perceive these events any differently, because when depression overtakes our minds, this perspective appears to be the only one through which it is possible to examine any of our pasts.

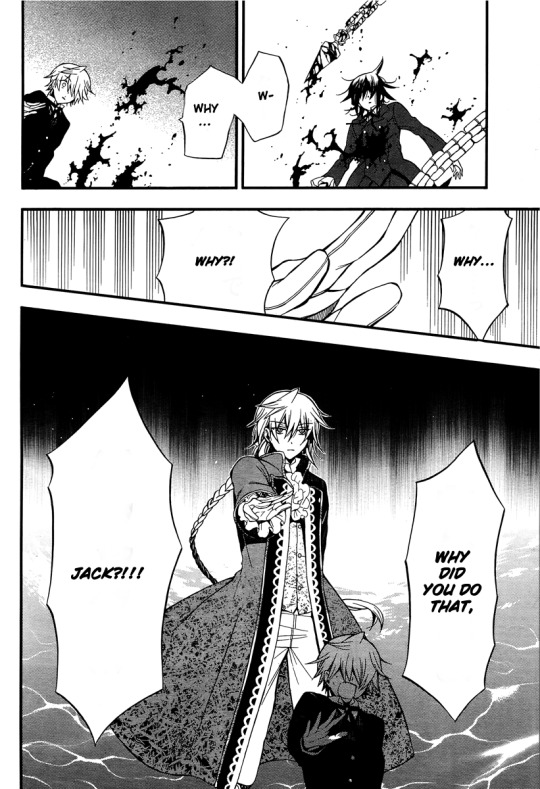

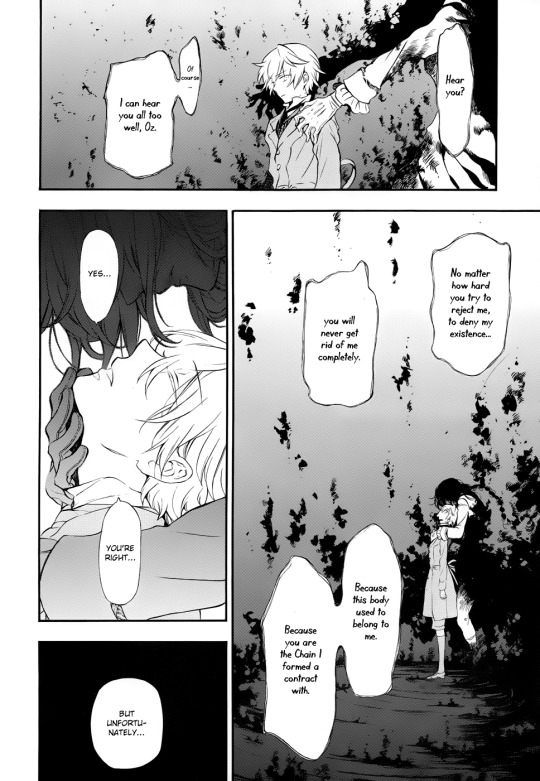

By the time Jack’s intentions have been exposed, he is also explicitly emotionally abusive towards Oz. It is easy to recognize Jack’s statements as not only psychologically damaging, but disturbingly similar to what we hear in our own heads when suffering depression. Think about these assertions without the very literal plot elements that support them: Jack declares Oz less than human, insists that nobody loves him, and claims that he has no future because the only thing he’s good for is hurting those around him. He convinces Oz that he is useless, hopeless, and worthless.

Jack drills these ideas into Oz’s head when he is at his most vulnerable. This is when Oz breaks down and becomes convinced that all of Jack’s statements are true. He is not who he thought he was; he never has been, and so his life is meaningless.

This is arguably when Oz reaches his all-time emotional low. While it was already addressed that he had been struggling intensely with his mental health and was probably suicidal, up to this point, he always retained some level of self-preservation (however slight). Now, he silently accepts that the world would be better off without him and offers no physical or emotional resistance to his own execution. Jack’s words worm their way into his heart and corrupt his self-image to the point where his only reaction to Oswald’s sword swinging towards him is a blank, unflinching stare.

Trauma Response

It’s not uncommon for Jack to manifest during catastrophic moments--that is, whenever a situation triggers (or comes close to triggering) overwhelming memories of Oz’s trauma. When Oz is losing control over his emotional and physical faculties, Jack often encourages him to make the trigger disappear using the quickest and easiest method available. Unsurprisingly, this method generally takes advantage of Oz’s extraordinary powers. In other words, the “tactic” Jack advises Oz to use is simply mindless destruction.

In the second half of the manga, Oz is at his least emotionally stable. It is not a coincidence that this is also the point during which Jack gains the ability to completely hijack Oz’s body. This development allows Jack to commit impulsive acts of aggression through Oz, while Oz himself retains little to no control.

Jack overwhelms Oz with unnecessary flashbacks to traumatic events and makes an excess of harmful connections between past and present circumstances. Oz’s panicked, distressed responses to this are tools he uses to further coax Oz into acting in a self-destructive manner. These tendencies may not only connect Jack to the concept of depression, but the concept of post-traumatic stress disorder as well.

Identity Crisis

Although Jack is introduced extremely early in the manga, one of the story’s main mysteries is the exact nature of his connection to Oz. This relationship shifts several times, especially with regards to who is “in control” and who is the true “owner” of the physical body.

Once it becomes public knowledge that Jack is “within” Oz, the identity of the former overcomes the identity of the latter in the eyes of the general populace. Figures who never before gave Oz a second glance begin to pay incredibly close attention to him; many directly address him through his connection to Jack rather than as a separate entity.

Oz is deeply troubled by the way others ignore him in favor of an aspect of his identity that he feels does not truly represent him--an aspect of his identity that is at least partially out of his control. However, he is also relatively resigned to being judged in this manner. He lacks knowledge of how to change this circumstance because even he does not truly understand the extent to which he and Jack are connected.

It is true that at this point in the story, Jack is practically worshipped. His destructive actions and devastatingly selfish nature have not yet been exposed. Because of this, Oz as Jack’s “vessel” is typically viewed through a positive lens. Still, this situation reflects how people with depression are sometimes reduced to nothing more than a mental illness by their peers. Because others do not understand (and mental illness is stigmatized), they start to see us as “different” in some indefinable but undeniable way, and our existence becomes that particular part of ourselves in their eyes.

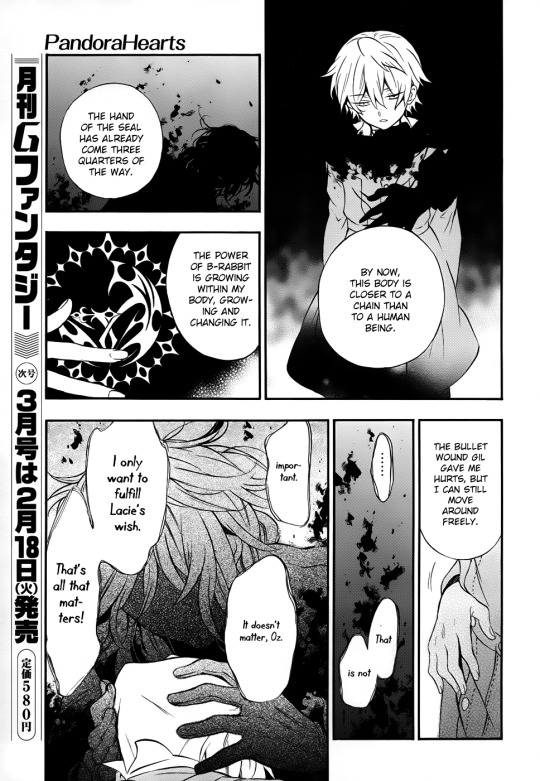

As time passes, the line between Jack and Oz becomes more and more blurred. Questions are raised about whether they are the same person or, on the contrary, whether they are similar at all. At what is arguably the climax of the manga, Jack declares that Oz’s body is, was, and will always be his possession; he claims that in reality, there is no “Oz,” only “Jack.”

This thought haunts Oz intensely and sends him into a rapid downward spiral. Like the sentiments expressed near the end of the “emotional abuse” section of this analysis, the idea that Oz’s body belongs to Jack is backed up by rigid, literal plot elements. However, if we view this emotional catastrophe using a symbolic perspective, it is a representation of yet another common struggle endured by those with depression.

We come to ask ourselves who we really are. Was there truly a time when we weren’t “like this?” Could we truly escape this misery in the future? Who would we be if we were to stop feeling this way? Do we even exist without depression? Does Oz even exist without Jack?

Visual Symbolism

It is a classic literary device to represent hope through light and despair through darkness. The manga is rife with this exact type of symbolism, utilizing it to describe how the Abyss has changed throughout time, Break’s dwindling eyesight, and the oscillating emotional states of various characters.

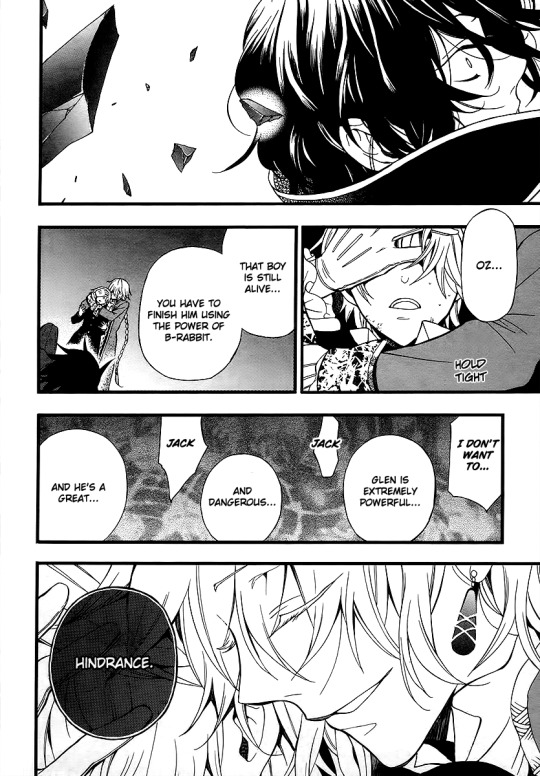

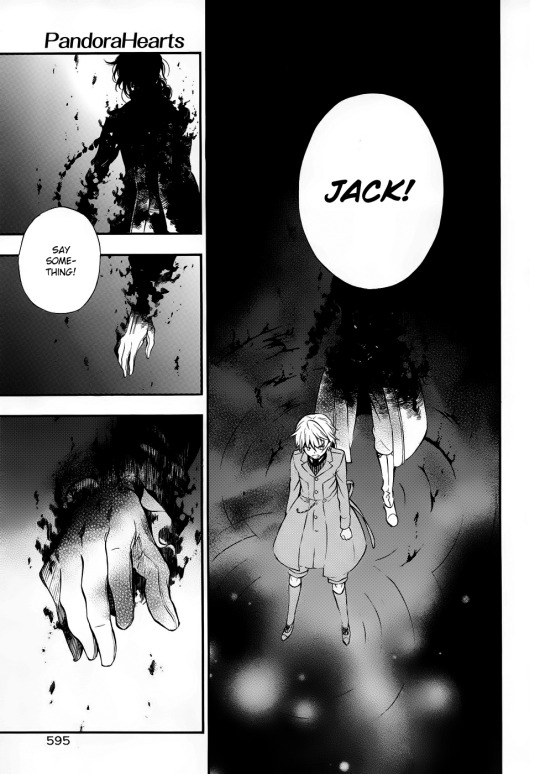

As I stated previously, Jack and Oz interact almost exclusively within the latter’s mind. The landscape drawn in the background of these conversations initially possesses a watery, clear appearance. However, as it becomes increasingly clear that Jack’s presence is deeply damaging to Oz’s psyche, this same landscape becomes overwhelmingly tainted by dark, ink-like shadows.

Closer examination reveals that this “pollution” originates directly from Jack--and it reaches its peak once Jack’s intentions have been fully disclosed. Not only is Oz’s mind visibly corrupted by darkness, but Jack himself appears as an almost inhuman figure composed of these shadows.

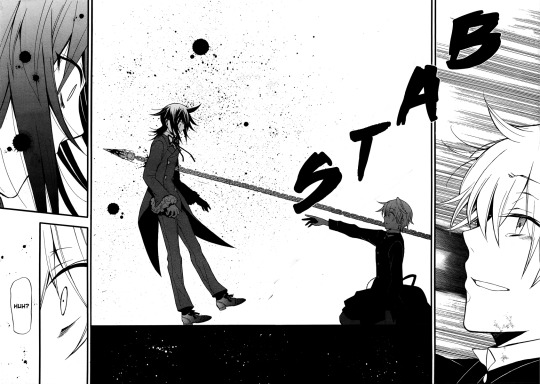

There is another level of visual symbolism as well--namely, the fact that Jack becomes increasingly physically aggressive and disrespectful towards Oz. In the first half of the manga, he primarily speaks to Oz from a distance, occasionally reaching out a hand in his direction. This is clearly not so in the second half of the manga, at which point Oz begins to defy his influence and it becomes vital that he subjugate him as quickly as possible.

By this time, Jack is almost always seen either restraining or caressing Oz. Even in the latter situation, when his touches are lingering and vaguely affectionate, they are possessive and constraining. In other words, though they appear different on the surface, both actions are ultimately methods of forcing Oz’s submission. It can be said that this represents his desire to gain complete control over all aspects of Oz’s being, as well as his total lack of respect for Oz’s physical and emotional autonomy.

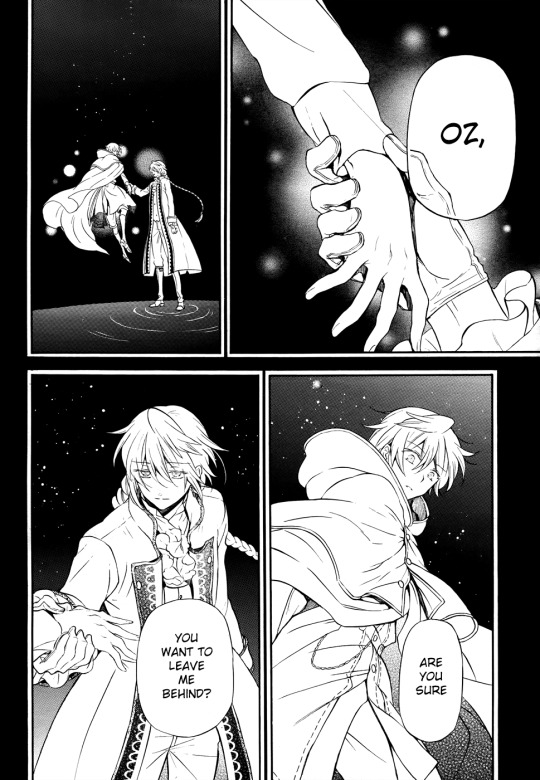

It can be argued that both of these aspects of symbolism reach their pinnacle even before this point. Oz realizes his own worth when Oscar says he loves him and reveals that his greatest desire is for him to be happy. When Oz is at last able to grasp that he is loved and there is hope within his life, Jack immediately reaches out to grab him. And in one of the manga’s subtlest but most poignant moments, his hand crumbles to dust upon touching Oz.

What follows is an extremely impactful display of Oz’s character development. He recalls Jack’s previous statements declaring his achievements worthless, denouncing the love he received from others as fake, and degrading his worth. Then he furiously rejects all of them, thrusting out a hand to push Jack away from him and consuming Jack in an explosion of light.

The conclusion to be drawn from this is that Jack essentially lives off Oz’s misery. When Oz understands and is able to accept that he is not worthless, Jack is suddenly rendered utterly powerless.

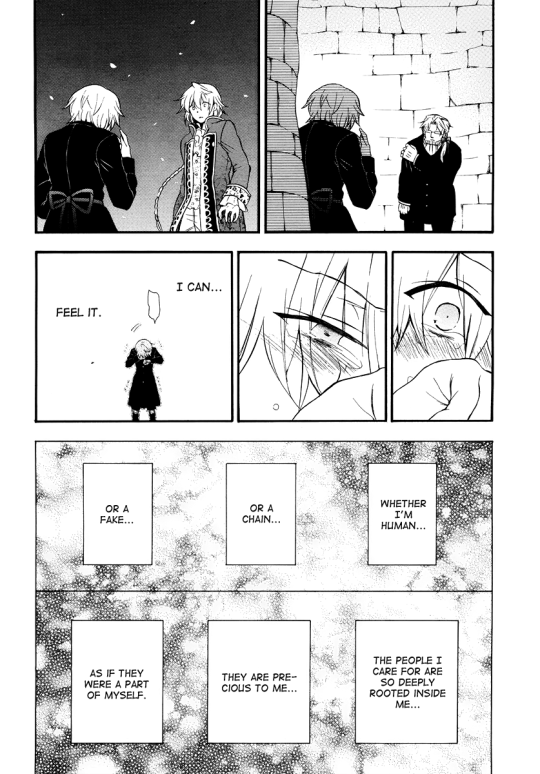

The manga culminates in a scene that coincides with this symbolism. This late into the story, Oz has succeeded in transcending Jack’s influence almost entirely, but Jack is not quite ready to let go. Though they stand together within a void, glimmers of light linger around Oz--despite everything, his life has come to be surrounded by hope and love.

As Oz floats towards the path of light above, Jack reaches out and takes hold of his wrist. But his grip is feeble and hesitant, representing how little control he truly holds over Oz at this point. Perhaps attempting to provoke guilt or regret, Jack asks Oz if he is certain that he is prepared to move on without him, but Oz has grown too much to succumb to this manipulation.

Without delay, Oz replies that there is no reason for him to stay, and Jack finally releases him. He escapes into the light--into a world full of people who care about him, into a life where he is happy to be alive.

#PandoraHearts#Pandora Hearts#Jack Vessalius#character analysis#Oz Vessalius#analysis#Cyokie's thoughts

161 notes

·

View notes

Photo

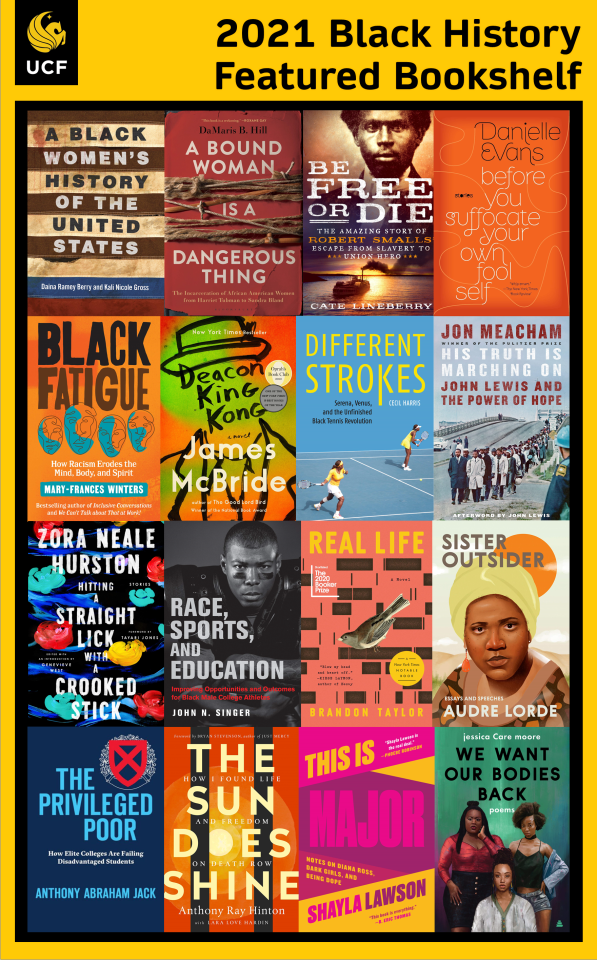

The national celebration of African American History was started by Carter G. Woodson, a Harvard-trained historian and the founder of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, and first celebrated as a weeklong event in February of 1926. After a half century of overwhelming popularity, the event was expanded to a full month in 1976 by President Gerald Ford.

Here at UCF Libraries we believe that knowledge empowers everyone in our community and that recognizing past inequities is the only way to prevent their continuation. This is why our February Featured Bookshelf suggestions range from celebrating outstanding African Americans to works illuminating the effects of systemic racism in our country. We are proud to present our top staff suggested books in honor of Black History Month 2021.

Click on the link below to see the full list, descriptions, and catalog links for the Black History Month titles suggested by UCF Library employees. These books plus many, many more are also on display on the main floor of the John C. Hitt Library near the Research & Information Desk.

A Black Women’s History of the United States by Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross In centering Black women's stories, two award-winning historians seek both to empower African American women and to show their allies that Black women's unique ability to make their own communities while combatting centuries of oppression is an essential component in our continued resistance to systemic racism and sexism. Berry and Gross prioritize many voices: enslaved women, freedwomen, religious leaders, artists, queer women, activists, and women who lived outside the law. The result is a starting point for exploring Black women's history and a testament to the beauty, richness, rhythm, tragedy, heartbreak, rage, and enduring love that abounds in the spirit of Black women in communities throughout the nation. Suggested by Sandy Avila, Research & Information Services

A Bound Woman is a Dangerous Thing: the incarceration of African American women from Harriet Tubman to Sandra Bland by DaMaris B. Hill For black American women, the experience of being bound has taken many forms: from the bondage of slavery to the Reconstruction-era criminalization of women; from the brutal constraints of Jim Crow to our own era's prison industrial complex, where between 1980 and 2014, the number of incarcerated women increased by 700%. For those women who lived and died resisting the dehumanization of confinement--physical, social, intellectual--the threat of being bound was real, constant, and lethal. From Harriet Tubman to Assata Shakur, Ida B. Wells to Sandra Bland and Black Lives Matter, black women freedom fighters have braved violence, scorn, despair, and isolation in order to lodge their protests. DaMaris Hill honors their experiences with at times harrowing, at times hopeful responses to her heroes, illustrated with black-and-white photographs throughout. Suggested by Megan Haught, Student Learning & Engagement/Research & Information Services

Be Free or Die: the amazing story of Robert Smalls' escape from slavery to Union hero by Cate Lineberry Cate Lineberry's compelling narrative illuminates Robert Smalls’ amazing journey from slave to Union hero and ultimately United States Congressman. This captivating tale of a valuable figure in American history gives fascinating insight into the country's first efforts to help newly freed slaves while also illustrating the many struggles and achievements of African Americans during the Civil War. Suggested by Dawn Tripp, Research & Information Services

Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self by Danielle Evans Fearless, funny, and ultimately tender, Evans's stories offer a bold new perspective on the experience of being young and African-American or mixed-race in modern-day America. Suggested by Sara Duff, Acquisitions & Collections

Black Fatigue: how racism erodes the mind, body, and spirit by Mary-Frances Winters This is the first book to define and explore Black fatigue, the intergenerational impact of systemic racism on the physical and psychological health of Black people--and explain why and how society needs to collectively do more to combat its pernicious effects. Suggested by Glen Samuels, Circulation

Deacon King Kong by James McBride From James McBride comes a wise and witty novel about what happens to the witnesses of a shooting. In September 1969, a fumbling, cranky old church deacon known as Sportcoat shuffles into the courtyard of the Cause Houses housing project in south Brooklyn, pulls a .45 from his pocket, and in front of everybody shoots the project's drug dealer at point-blank range. McBride brings to vivid life the people affected by the shooting: the victim, the African-American and Latinx residents who witnessed it, the white neighbors, the local cops assigned to investigate, the members of the Five Ends Baptist Church where Sportcoat was deacon, the neighborhood's Italian mobsters, and Sportcoat himself. As the story deepens, it becomes clear that the lives of the characters--caught in the tumultuous swirl of 1960s New York--overlap in unexpected ways. When the truth does emerge, McBride shows us that not all secrets are meant to be hidden, that the best way to grow is to face change without fear, and that the seeds of love lie in hope and compassion. Suggested by Sara Duff, Acquisitions & Collections

Different Strokes: Serena, Venus, and the unfinished Black tennis revolution by Cecil Harris Harris chronicles the rise of the Williams sisters, as well as other champions of color, closely examining how African Americans are collectively faring in tennis, on the court and off. Despite the success of the Williams sisters and the election of former pro player Katrina Adams as the U.S. Tennis Association’s first black president, top black players still receive racist messages via social media and sometimes in public. The reality is that while significant progress has been made in the sport, much work remains before anything resembling equality is achieved. Suggested by Megan Haught, Student Learning & Engagement/Research & Information Services

His Truth Is Marching On: John Lewis and the power of hope by Jon Meacham John Lewis, who at age twenty-five marched in Selma and was beaten on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, is a visionary and a man of faith. Using intimate interviews with Lewis and his family and deep research into the history of the civil rights movement, Meacham writes of how the activist and leader was inspired by the Bible, his mother's unbreakable spirit, his sharecropper father's tireless ambition, and his teachers in nonviolence, Reverend James Lawson and Martin Luther King, Jr. A believer in hope above all else, Lewis learned from a young age that nonviolence was not only a tactic but a philosophy, a biblical imperative, and a transforming reality. Integral to Lewis's commitment to bettering the nation was his faith in humanity and in God, and an unshakable belief in the power of hope. Meacham calls Lewis as important to the founding of a modern and multiethnic twentieth- and twenty-first century America as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison and Samuel Adams were to the initial creation of the nation-state in the eighteenth century. Suggested by Richard Harrison, Research & Information Services

Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick by Zora Neale Hurston An outstanding collection of stories about love and migration, gender and class, racism and sexism that proudly reflect African American folk culture. Brought together for the first time in one volume, they include eight of Hurston’s “lost” Harlem stories, which were found in forgotten periodicals and archives. These stories challenge conceptions of Hurston as an author of rural fiction and include gems that flash with her biting, satiric humor, as well as more serious tales reflective of the cultural currents of Hurston’s world. Suggested by Sandy Avila, Research & Information Services

Race, Sports, and Education: improving opportunities and outcomes for black male college athletes by John N. Singer Through his analysis of the system and his attention to student views and experiences, Singer crafts a valuable, nuanced account and points in the direction of reforms that would significantly improve the educational opportunities and experiences of these athletes. At a time when collegiate sports have attained unmistakable institutional value and generated unprecedented financial returns-all while largely failing the educational needs of its athletes-this book offers a clear, detailed vision of the current situation and suggestions for a more equitable way forward. Suggested by Megan Haught, Student Learning & Engagement/Research & Information Services

Real Life by Brandon Taylor A novel of rare emotional power that excavates the social intricacies of a late-summer weekend -- and a lifetime of buried pain. Almost everything about Wallace, an introverted African-American transplant from Alabama, is at odds with the lakeside Midwestern university town where he is working toward a biochem degree. For reasons of self-preservation, Wallace has enforced a wary distance even within his own circle of friends -- some dating each other, some dating women, some feigning straightness. But a series of confrontations with colleagues, and an unexpected encounter with a young straight man, conspire to fracture his defenses, while revealing hidden currents of resentment and desire that threaten the equilibrium of their community. Suggested by Sara Duff, Acquisitions & Collections

Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde In this charged collection of fifteen essays and speeches, Lorde takes on sexism, racism, ageism, homophobia, and class, and propounds social difference as a vehicle for action and change. Her prose is incisive, unflinching, and lyrical, reflecting struggle but ultimately offering messages of hope. Suggested by Emily Horne, Rosen Library

The Privileged Poor: how elite colleges are failing disadvantaged students by Abraham Jack College presidents and deans of admission have opened their doors--and their coffers--to support a more diverse student body. But is it enough just to let them in? Anthony Jack reveals that the struggles of less privileged students continue long after they've arrived on campus. In their first weeks they quickly learn that admission does not mean acceptance. In this bracing and necessary book, Jack documents how university policies and cultures can exacerbate preexisting inequalities, and reveals why these policies hit some students harder than others. Jack provides concrete advice to help schools reduce these hidden disadvantages--advice we cannot afford to ignore. Suggested by Peggy Nuhn, UCF Connect Libraries

The Sun Does Shine: how I found life and freedom on death row by Anthony Ray Hinton, with Lara Love Hardin In 1985, Anthony Ray Hinton was arrested and charged with two counts of capital murder in Alabama. Stunned, confused, and only twenty-nine years old, Hinton knew that it was a case of mistaken identity and believed that the truth would prove his innocence and ultimately set him free. But with no money and a different system of justice for a poor black man in the South, Hinton was sentenced to death by electrocution. He spent his first three years on Death Row at Holman State Prison in agonizing silence, full of despair and anger toward all those who had sent an innocent man to his death. But as Hinton realized and accepted his fate, he resolved not only to survive, but find a way to live on Death Row. For the next twenty-seven years he was a beacon, transforming not only his own spirit, but those of his fellow inmates, fifty-four of whom were executed mere feet from his cell. With the help of civil rights attorney and author Bryan Stevenson, Hinton won his release in 2015. Suggested by Lily Dubach, UCF Connect Libraries

This is Major: notes on Diana Ross, dark girls, and being dope by Shayla Lawson Shayla Lawson is major. You don't know who she is, yet, but that's okay. She is on a mission to move black girls like herself from best supporting actress to a starring roles in the major narrative. With a unique mix of personal stories, pop culture observations, and insights into politics and history, Lawson sheds light on the many ways black femininity has influenced mainstream culture. Timely, enlightening, and wickedly sharp, Lawson shows how major black women and girls really are. Suggested by Glen Samuels, Circulation

We Want Our Bodies Back by Jessica Care Moore Over the past two decades, Jessica Care Moore has become a cultural force as a poet, performer, publisher, activist, and critic. Reflecting her transcendent electric voice, this searing poetry collection is filled with moving, original stanzas that speak to both Black women’s creative and intellectual power, and express the pain, sadness, and anger of those who suffer constant scrutiny because of their gender and race. Fierce and passionate, she argues that Black women spend their lives building a physical and emotional shelter to protect themselves from misogyny, criminalization, hatred, stereotypes, sexual assault, objectification, patriarchy, and death threats. Suggested by Sara Duff, Acquisitions & Collections

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aldrich and the Desacralization of Dark Souls 3

Aldrich, the obsessive-consumptive cannibal saint, is one of Dark Souls 3′s most interesting figures when one sees his actions and inferred character as representing a prominent facet of humanity’s spiritual position at the time of the game’s setting. If we look at Dark Souls 3′s landscape as an assemblage of symbolics, and compare it to Dark Souls’ arrangement, we see that an inversion has occurred: the zenith is the human domain of the High Wall of Lothric, and the nadir is Irithyll/Anor Londo, once the apical sunlit land of the gods, now chilled, darkened, and sunken. And yet, even if Anor Londo only ever represented the power of a pantheonic institution, its ruination and darkness here is a much more troubling scenario; because at the “zenith” we find only stasis or stagnation, a reflection of the psychology of prince Lothric himself who has selfishly fended off fate through elusion and inactivity (if we note the series’ pattern of things being what one makes of them (i.e., reality is what one believes it to be), we may wonder if Lothric’s lameness was not self-willed¹). On the broadest scale approaching metatexuality, we see too that Dark Souls 3 is the series at its most complex and diffuse, with the collective mono-myth responsible for the Age of Fire now distant, separate, very nearly nonexistent.

For an example of this, let us look to the swamp around Farron Keep, where we must put out three flame-beacons corresponding to the Witch of Izalith, Nito, and Gwyn’s deific family. This sequence is an initiatory rite of passage, but, rather than entering into a mystery for contact with the numinous, we perform willful ignorance for mere tribalism (to witness it, anyway). For it is only through this symbolic act of un-remembering -- the nullification of the sustaining flame of myth, the obscuring of its principal actors -- that we are granted access to the Keep proper, and then to the Abyss Watchers, a clan of warriors who represent, to an extreme, “mass-mindedness”: directionless, hollow zombies who do not even remember the name of the knight they model themselves upon. All that matters here is the Clan, where insular, infinite warfare is mistaken for life-sustaining meaning (I’d make special note of the fact that the Abyss Watchers all resemble one another; the violence done to another is, in truth, violence done to the self: self-oppression misinterpreted as empowerment). As César Daly wrote, “To neglect history, to neglect memory, that which is owed by our ancestors, is then to deny oneself; it is to begin suicide.” The great abundance of such details makes it all the more startling when Shira, in the Ringed City, says to us, “Speak thee the name of God” (i.e., Gwyn).

No one can seem to agree on what exactly constitutes or delineates the Age of Fire or the Age of Dark, but Dark Souls’ Serpent Kaathe refers to the latter as "the age of men.” Given the evidence, it is difficult to not see Dark Souls 3 as marking the beginning of such an age, or at least the transition between the two. But what liberties has it brought? They are, I think, the pseudo-liberties of a desacralized world. Narratives have become aimless, attempts are made to plug up voids without examining root causes, and the self cannot be harnessed for purposeful actualization. If we seek a demonstration of the latter, think of our first major combative encounter in the game with Iudex Gundyr, whose body, midway through the fight, unleashes a chaotic mass of black, writhing forms uniformly termed the Pus of Man. The Pus of Man reappears during our initial exploration of the High Wall of Lothric, this time out of a couple of standard Hollows. Once the Pus of Man has emerged and is aware of us, any semblance of the host’s self-control is usurped by total destructive instability.

In our own bodies, pus is the result of infection, and its treatment is its release from an abscess; but the Pus of Man, thus released, does not allow for healing, because its internal causes, a symptom of a shared spiritual crisis, have gone unchecked for too long, and so it assumes complete control. It is, on one level, a coup by the id, which Freud describes as “...a chaos, a cauldron full of seething excitations. ...It is filled with energy reaching it from the instincts, but it has no organization, produces no collective will, but only a striving to bring about the satisfaction of the instinctual needs subject to the observance of the pleasure principle.” It would also not be inappropriate here to look to the concept of humorism, wherein humans’ personalities are regulated by vital body fluids, and where we find (within the most popular, four-component model) “black bile”, a secretion whose associated qualities are coldness and dryness and whose effect is melancholia: “a mental condition characterized by extreme depression, bodily complaints, and sometimes hallucinations and delusions.”

The Cathedral of the Deep is representative of the same crisis, but diverges in the shape of its consequence. If the Pus of Man recalls Manus, whose “humanity went wild”, and signifies degradation with “seething excitations”, then the Cathedral of the Deep -- a religion and a site -- signifies degradation with stagnation. Inside the Cathedral, we find that its nave and south transept is thick with liquidized decay, the perimeters encrusted by mounds of corpses. These are the matter-of-fact results of both mortification of the flesh (done by flagellation) and Aldrich’s cannibalism, prior to his relocation. What’s relevant here is the material stasis. Richard Pilbeam, in his video “The Bastard’s Curse”, compares aspects of the Deep faith to those of Shinto, placing specific emphasis on the cleansing properties of water. He notes: “Water will wash away impurity, but only if the water remains in motion.”² The motion of the water is the motion of a dynamic, reciprocal spirituality. Our own bloodflow requires circulation.

All of this talk of the body, ruptures, and liquid brings us back to Aldrich, the Devourer of Gods. Despite his title, the only god we are explicitly aware of Aldrich having consumed is Gwyndolin; but the sheer extent of rotting flesh and bones (some, no doubt, of mortals) in Aldrich’s current habitat, the appropriated chancel of the great Anor Londo cathedral, is evidence of innumerable, unseen feasts. Inspecting the soul of Aldrich, we are told that when he “...ruminated on the fading of the fire, it inspired visions of a coming age of the deep sea. He knew the path would be arduous, but he had no fear. He would devour the gods himself.” It again behooves us to approach the matter in terms of symbolics, poetic substitutions, and understand this envisioned age as a radically desacralized state of being, one where the Age of Fire has been permanently entombed, replaced by a humanity misled by vacuous obsessions which is then itself overcome by what those profanities manifested. “In time, those dedicated to sealing away the horrors of the Deep succumbed to their very power,” the description for a robe worn by deacons of the Cathedral of the Deep reads. “It seems that neither tending to the flame, nor the faith, could save them.”

Aldrich, as a deiphagous agent (although perhaps not godly to begin with himself), of course has deicidal associations.³ Most pertinent would be the filicide of the Titan Cronus, who devoured his children in fear of his prophesied deposition. We are told that Aldrich “had no fear”, but this is, I think, an ironic statement. In the same way that we may compulsively eat in order to fill an emotional-existential void, Aldrich feeds to fill the void of Dark Souls 3 which has, as M. Christine Boyer writes in reference to modernity, “[closed] off any meaningful access to the past.” Yet his murderous feasting prepares himself and the world for another void: that of the “age of the deep sea” (to be slightly literal for a moment: what, on Earth, is more akin to a void than the ocean’s depths?). At the Ringed City we observe resonances of this behavior in the locusts, who primarily inhabit the dim mire at the city’s bases (the resemblance to Oolacile’s predicament is unmistakable), and “were meant to beckon men to the dark with sermons, but most of [which] are unable to think past their own stomachs.”

We should also recognize that Aldrich did not act alone. He “had the desire to share with others his joy of imbibing the final shudders of life while luxuriating in his victim's screams.” Recall that certain deacons of the Deep are bloated, including the deceased Archdeacon McDonnell. These are ministers who have oftener partaken of feasts. So here is also a distortion of that communal principle wherein participants ingest the deity/deities and affirm life through its nearness to death. This ingestion recalls the older meaning of “embody”: “a soul or spirit invested with a physical form.” George Hersey writes, of the ancient Greeks and their sacrificial rituals, “Whatever form the victim or offering took, once it was [...] full of the god, [...] the divinity became too immense, too terrible, to be contained. It was necessary to break apart the offering. Yet even after death -- perhaps especially after it -- the animal’s carcass, the god’s container, was steeped in his presence. This is why the worshipers ate parts of it: the act was not just feasting, but communion. The worshipers’ own bodies combined with parts of the victim’s to express the fact that the god had entered them. The victim’s body parts were in fact ‘reconstructed’ now in a different way, by uniting the bodies of the worshipers.”⁴

There is no concern for any of these vitalizing affirmations with Aldrich and his followers. Indeed, we see that Aldrich himself has become “too immense, too terrible, to be contained” (just like those aforementioned “horrors of the Deep”), and so his body is coagulated hemorrhage. Constructive concepts such as selflessness, spirit, metousiosis are nullified, as the consumptive process, one of intense sadism, functions as its own end. Aldrich is both terribly and mundanely a narcissistic parasite. During our fight with him, he will burrow into the refuse of the arena to temporarily escape -- a tactic that is emblematic of his self-regressing psychology, where nothing matters except gorging, sleeping, and surrounding oneself with a playpen of mud to dive into and thus hide from the world. Remember, now, that Aldrich was canonized as a Lord and remains one. Hawkwood, a former member of Farron’s Undead Legion and a resident of Firelink Shrine, wryly and accurately comments that this was “...Not for virtue, but for might.” And when we venerate sheer might, we venerate persecution.

From this perspective, I think it is not an accident of phrasing when the description for human dregs, an object sometimes released by slain Deep devotees, says that they, once having sunk to the “lowest depths imaginable, [...] become the shackles that bind this world.” To bind something can mean to unify it, to adhere components together and provide a sort of structure; but this is done with shackles, items associated with repression and enslavement. It is another echoing of that “self-oppression misinterpreted as empowerment” (or, analogously, freedom). There may be no better conclusion to this essay than to remark upon Aldrich’s death at our ends. As the battle progresses, Aldrich’s body becomes enkindled, speckled by embers, to the extent that any zone he occupies catches on fire. This is not so different from Yhorm or the remaining Abyss Watcher; after all, they are Lords of Cinder too. But I believe that, for Aldrich, this can be read relative to the sacrificial ritual which ended with roasting specified parts of the animal and then eating them. Thus, when we kill Aldrich, even if we cannot adopt and atone for the sins of his actions, we can at least break that insatiable cycle and consign his body to the purifying fire -- so that we may, finally, take and imbibe his soul.

You can financially support my writing, art, and music on Patreon.

¹ Dark Souls 2 quickly presents us with an example of this when a handmaid gives us a featureless human effigy and says, “Take a closer look... Who do you think it’s supposed to be? Think back, deep into your past. Yes, it’s an effigy of you.” Consider also the case of Miracles, which are not instructions but stories. Once read, they turn real -- fiction tangibly weaponized.

² See: Misogi and kegare. The concept of the sacred grotto is apposite, too, if we imagine that the latter-christened Cathedral of the Deep neighbors one. In Heavenly Caves, Naomi Miller writes, “Fascination with the grotto is rooted in the story of creation. While understood as a source of life and as a sacred spring in the classical world, in the Old Testament the grotto is often equated with the void and hence with chaos -- the formlessness that precedes the beginning. [...] ...within the Temple in Jerusalem, beneath the Stone of Foundation in the Dome of the Rock, was a cave known as the Well of Souls. This fountain of perennial water within the Temple may well allude to the cisterns and reservoirs known to be under the Holy Rock, but it also has metaphysical significance and refers to the mouth of the abyss identified with the subterranean torrent located at the earth’s center, from whence the rivers of Paradise went forth to water the four corners of the world...”

³ An example of deicide which is often not thought of as such is that of Christ, who, in his self-sacrifice as the human avatar of God, clears the way for a radically new covenant.

⁴ Walter Burket, in his book Homo Necans, posits that such sacrifices “were much later reenactments of primal ritual murders in which a god-king was killed and consumed.”

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

His Cage pt. 2: Wheel of Fortune

This essay may be read on its own, but it is a follow-up to another essay which psychoanalyzes the figure of Holy Knight Hodrick, a character from Dark Souls 3. In this section, the method and purpose of Dark Souls analysis comes under investigation, catalyzed by other images from Hodrick’s environment.

Hodrick as meta-critique of Freudian psycho-interpretation

Dark Souls 3 is known for its skillful, self-reflexive commentary; this game is keenly aware of the subculture that surrounds it. That in mind, what are we to make of the relatively blatant symbolic suggestiveness of Hodrick and the Greatwood? Perhaps their on-the-nose imagery is a reaction to analysis of previous Dark Souls games: the castration narrative is often cited in symbolic interpretation of Dark Souls 1, and the birth canal-esque passage of Dark Souls 2’s tutorial area is a classic introduction for people that play around with interpreting Dark Souls psychologically. And surely those myths and images are semi-intentional, relevant, and illuminating, but they are by no means the place to stop. This lore video points out how the vertebrae shackles collected by Mound-Makers resemble inkblots, the old psychoanalytic tool etched into the cultural memory as an image of Freudianism. One “reads out” of the inkblot the contents of their own unconscious. The understanding of projection, and the compensatory nature of the unconscious was one of the most significant discoveries at the dawn of psychology. Dark Souls could symbolize the principle of this discovery in a number of ways, but it is very intentional with its images, so when it decides to show us an inkblot in particular, the historical context is helpful. It’s an old and simple technique, which traces only the broad strokes of the analysand’s complexes. Likewise, Hodrick, the Greatwood, and Mound-Makers provide the interpreter with the rudiments for symbolic exploration of Dark Soul environments.

Though this area is introductory, it is – like any part of the unconscious – inexhaustible in its depth and generous in its mutability. Consider the amorality of the Mound-Makers. Are they good or evil? Vicious or tender? Sustainers of maya or karmic accelerationists? There is so much room for the player to read into this allegiance a preferred moral perspective, at least partially determined by the general attitude the player keeps in regards to the slaughter of enemies. For the totally “unimmersed,” Dark Souls is a game and a game only, to be played, poked, prodded, to be mastered and speedran, and in that case of course any covenant is merely functional, there to surround and present a mechanic. For that player, the Mound-Makers are truly amoral. But for those who roleplay, who make at least some of their choices based on the imagined ethics of their avatar (despite extremely scarce moral responses from the game itself!), the issue is a little more complicated. Those who are simply in the habit of asking themselves, “Do I want to ally myself with this person’s values?” will not find an easy answer. On the surface, the covenant is abhorrently nihilistic, but a seasoned player may come away with a different take. So in this way the Mound-Makers, like the inkblot, are a measure of a player(/-character)’s feeling-involvement, which is itself born out of the player’s interpretational attitude.

When analyzing an object in a video game, always take into account the method by which it is encountered! Though the route to all this Freudian material in the Undead Settlement is a little arcane, it needs to be. The cryptic riddle about “Nana”, the obscure side-streets: these are there to make the player feel as though they are uncovering something secret. The obscurity is baked-in to make obvious that this material is repressed.

Though the riddle is strange, it is spoken aloud to the player, which is actually quite a telegraph by Dark Souls standards. The handiness of this secret is also metaphorically descriptive of this level of interpretation. If one stops at the purely Freudian: the mother, the father, the phallus, then they will project that schematic onto every available target. They will see reality as nothing more than a circus of oral fixations and castration dramas. If this stage of psychoanalysis is not passed through, it is nothing more than another cage to be carried around. It is the most rudimentary place to get stuck in the engagement with the unconscious.

The Armory of Symbols

What are we to make of the fact that the treasure of this area is the transposing kiln? This round thing, this simple, Arthurian symbol of the Self? It is both representative of the totality, and a totally profane and reductive simplification. I’ll explain what I mean by that.

On the one hand it is a true grail, because it has the capacity to turn the game’s hardest challenges into new tools. This is a fantastic life lesson, fundamental and perennially true. It is the pure gift of interpretation. It is said that the Buddha, in his realization that there is nothing outside of Nirvana, thereby saw that even the most torturous experiences of life, and the most unforgiving realms of Hell, were not apart from Nirvana, and that seeing them in this way thereby rectified this subjective experience of being in Hell. Once it was rephrased as Nirvana, it was always Nirvana, because all the suffering was born out of false views. Anyway, that is a very lofty height of interpretation, but one can see the boundlessness of the tool. That when the true cosmic appropriateness of an instance of suffering is groked, it is changed. On the other hand, transposition is a cheap parlor trick. It changes the essence of a boss into a weapon. It really only does one thing. Some of these weapons are useful, and most are flashy. It is almost mandatory for these weapons and spells to have a unique gimmick. So most of the time they convey to the wielder some unique flavor, some specific characteristic to consider, but even collecting such interpretations as these is merely a “building a collection.” Pinning down butterflies into a glass case. It is really no different than stockpiling corpses as Hodrick does. This device encourages the player to keep fighting, collecting, stacking bodies, finding new and interesting ways to kill people.

And ultimately, the same is true of collecting symbolism. Stockpiling a collection of unused weapons is no more or less a perversion that keeping a catalogue of archetypes for its own sake. The psychological interpretation of Hodrick, the Greatwood, and their unsightly tableau is relatively simple and straight-forward because it is meant to provide the player-interpreter with an introduction to the technique. The “game” of symbolic analysis is pointless if you spend your time taking potshots.

Wheel of Fate

Understanding the symbolism of the Mother through the eyes of Hodrick may be relatively simple, but the Undead Settlement also provides us with a more complex and transpersonal variation of the birth motif, localized at the far edge of town, hidden in a valley below. There we find catacombs tunneled into the rock, reminding us of the community of villagers who labor all day burying their dead. The Great Mother is thereby invoked, in her role which deteriorates form, which composts. The bodies decay, return to the Earth, and nourish new life. We see the skeletons sprouting branches in this dank place.

Also in the catacombs there are the dual figures of Irina the saint and a statue of Velka, goddess of sin, both of whom sit abandoned. The juxtaposition of these two sacred feminine figures is symbolically dense and deserves its own essay, but I mention it here as an echo of Kristeva’s philosophy that we passed by earlier: that of the child’s necessary bifurcation of the Mother into sublime and abject.

Velka alone is highly useful here, amplifying the Great Mother motif to a vast and cosmic context. Velka is a notoriously elusive figure in Dark Souls: she is never seen, rarely spoken of, her motivations are unknown, her ontological status unconfirmed, her objects and attributes seem to contradict each other. Nevertheless she is a crucial if not essential force in the world, and her presence can be inferred for those with eyes to see.

The main Velkan element that should be addressed here is her association with Karma, which is perhaps her principle attribute. From the beginning of DS1, she is introduced as governess of ethics, law, and equity. She explicitly oversees sin, guilt, and retribution. What practices are promoted through this governance? Mechanically, there are primarily two: keeping track of invasion penalties (in DS1) and resetting the world. If you incur penalty as an invader, the Blades of the Dark Moon will find you and punish you. So Velka prolongs and complicates PvP dynamics.

Resetting the world is an effect Velka provides that suggests forgiveness. If you aggro an NPC, and wish to get on good terms with them again, Velka allows that condition. In this way too, Velka is prolonging interpersonal relationships, but it is the relief of debt rather than the accruing of debt. Velka keeps the cycle going, she is like a keeper of the wheel that turns the age. In Dark Souls 1 a statue associated with Velka turns with the cranking of a wheel, in a room full of bonewheel skeletons. In Dark Souls 3, a similar statue turns with the cranking of a wheel in a room full of flies. In both cases, the wheel is hidden in a wet chamber behind an illusory wall. This suggests that behind the façade of the world, there is a primal place from which time is manipulated (though in this case it is but a single “tick” of the clock, an off-to-on switch which causes a fixed rotation).

Does Karma cause the rise and fall of the great ages? Is the distribution of karma the grease that turns the wheel of the world? It does seem to be that desire is what sustains the age of fire. Consider the enemies in the place where the wheel turns: bonewheels, who cling to their instruments of torture, to their suffering; flies, who bury themselves in a mountain of rotted food, a symbol of greed.

The skeletons who throw themselves into combat, and the flies which gorge on their rotting piles: either is a handy metaphor for Hodrick. His lust for the battlefield is another way of keeping himself stuck on the wheel of Samsara, collecting those shackles, representing the Velkan attachments of karma. Velka’s totem, the Raven, is found in flocks on a ravaged cliff in the settlement, among a wealth of corpses to be looted. The Raven is “associated with the fall of Spirit into that which is impure and enjoys carnage […] To raven is to plunder. This is what the word means. To have a ravenous appetite suggests greed and lust and insatiable desires.”(Valborg) Ravens keep the circus of suffering going!

Grist for the Mill

Velka is a bleak goddess, associated with “lifehunt”, the capacity to drain the essence of life, dreaded even by the gods. For this reason one of her attributes is the scythe, so she is something of a reaper figure. But we have seen she is also life-giver and sustainer, through her arbitrage of karma. This ambivalent nature is expressed by the Raven, which is a solar bird yet dyed deep black, who is cruel and enjoys carnage, yet in many myths is associated with the bringing of light and the creation of a new world.

The raven flies to and fro between the solar orb of eternal life and the dying eyes of man in time. He mercilessly pecks away at the delusions formed like veils over the cornea's shield until he penetrates to the darkness of the pupil's cavity and releases the invisible light within. (Valborg)

If the goal of Dark Souls is the realization of the Dark Soul -- the unique potential of the human being -- then perhaps Velka and her karmic processes are meant to midwife that birth as well. Could all the weight of karma, the pain of enduring a body, the cruelty of life’s entropic march … could it all be in service of birthing the Anthropos? It would explain why the Lords of Dark Souls are so antagonist to the Ashen One -- in Gnosticism and Buddhism the makers, the deities, are said to envy the actualized human being. And to be fair, the theme of surviving hardship and loss is central in Dark Souls’ reputation, and something to which countless players can attest, on practical or psychological levels (eg: “Dark Souls Helped Me Overcome Depression”).

Identity Riddles

I am the one who is disgraced and the great one. Give heed to my poverty and my wealth. Do not be arrogant to me when I am cast out upon the earth, and you will find me in those that are to come. And do not look upon me on the dung-heap nor go and leave me cast out, and you will find me in the kingdoms. And do not look upon me when I am cast out among those who are disgraced and in the least places, nor laugh at me. And do not cast me out among those who are slain in violence.

But I, I am compassionate and I am cruel. Be on your guard!

Do not hate my obedience and do not love my self-control. In my weakness, do not forsake me, and do not be afraid of my power.

-- excerpt from The Thunder, Perfect Intellect ca. 100-230

The abject Mother sits at the edge of the symbolic order, in fact it is her abjection that positions the boundaries of that order, yet it itself does not accept boundary. “Abjection preserves what existed in the archaism of pre-objectal relationship, in the immemorial violence with which a body becomes separated from another body in order to be” (Kristeva 10), referring to birth and symbolized by the Hodrick and Greatwood scene, but beyond that it also refers to the Dark Souls creation myth: the archaism in that case being the undifferentiated fog of arch-trees and everlasting dragons in the Age of Ancients. For there to be matter and objects, psyche (dragons etc) must be born into time. Once psyche has materialized itself upon the wheel of time, it cannot exist in immediate, gestalt totality – it moves and changes, expressing its fullness over aeons through its becomings. But everything must be accounted for; Karma only brings what is due. The mystery of how psyche is refined by its extension into matter will likely stay with us until the “end” of time. But with common sense we can suppose that the condition of duration allows things to be taken apart and put back together, and that at least in our mundane lives that process frequently brings about some freshness in the object. But neither the meaning nor mechanics of the larger karmic process can be groked, just as Velka and the Mother are archetypes who inherently escape the fixidity of signification. The ultimate force of taking things apart, entropy – symbolized again by the raven and its desecration of corpses – is something that has been deeply culturally villainized, and it usually takes a second to stop and consider how the diffusion of matter engenders the condition for new forms to grow.

[Ravens] tell of the renewal of the world in terms of the past which is yet to be. The unwanted Truth is told and its insatiable desire to express itself may produce terror and loathing in one who is not prepared to give up all to its insistent glare.

This is keeping with Kristeva’s view of the abject as the eruption of the Real into consciousness. Aside from their role in pecking open an aperture of light, crows have another specific job in the renewal of the world, as described in a number of myths: measuring the size and extent of that world, flying in “progressively longer intervals in order to estimate and report on the increasing size of the emerging earth.” The extremes of incarnation, the edges beyond which dwells the abject, are scoped out in order to create the blueprint; the raven brings knowledge of the schematics.

Interpreting by Attention

And what about our own schematics? We’ve thrown away our tools – the colorful cast of characters transposed into weapons of interpretation – but perhaps it’s time to pick them up again. We cast them off because we didn’t want to fix the Dark Souls myth through explanation. Archetypes cannot be superimposed, prefab, onto a tableaux of psychological symbols. Interpretation is rather the act of elaboration: flying, as the raven does, around and around a widening and changing arena, reporting back continually new understandings of what is appropriate.

The meaning of a game is determined by what a player thinks and feels while they play it. What decisions they make, what their attention lingers on. The game is the inkblot. There are special times when the game insists upon a subject, like a film: for instance, when the crank is turned and the Velka statue rotates. But such a sequence has a different meaning in games than it does in film, because of its context: it anchors a player to a single necessary and unchanging action in the context of a world that is typically responding to their decisions with nigh-unrepeatable novelty. The fixedness of the cinematic exposes the malleability of the rest of the game. “Velka” is an approximation, an aggregate; she is not the same goddess in each playthrough, the scope and the flavor of her influence is always changing – but it is always reflecting the actions of the player.

So how then, can we arrive at a judgment regarding Hodrick? We can’t, because again, each player’s experience of him is different. Earlier I implied that Hodrick is clinging to the world, out of horror and alienation in regards to the Mother figure, and that his killing spree is only building his attachments, keeping him fixed to the wheel of incarnation. So what is the difference between his wild manslaughter, and Velka’s own penchant for carnage and lifedrain? Only the intent:

The transformation of relationship can come about through a genuine understanding of the difference between murder and sacrifice. Both kill or suppress energy, but the motives behind them are quite different. Murder is rooted in ego needs for power and domination. Sacrifice is rooted in the ego’s surrender to the guidance of the Self in order to transform destructive, although perhaps comfortable, energy patterns into the creative flow of life. (Woodman 33)

But see, it is only the inner experience of the act that has authority. In my view, Hodrick’s actions are clearly ego-driven, but another player with different exposure to this character could come away with a different impression. And the archetype speaks through the individual encounter itself, not through lore videos, essays, or any other metatext. This is a crucial function of video games that bears repeating and is rarely addressed. Games commonly use the act of killing as a metaphor for the transformation of relationship (the very notion of EXP hinges on that). The unconscious is receptive to these mutations regardless, but the nature of the effect is dependent on the conscious attitude of the player.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror. Columbia University Press, 1980.

Layton, Bentley, ed. The Gnostic Scriptures. Yale University Press, 1995.

Valborg, Helen. The Raven. Theosophy Trust, 2013.

Woodman, Marion. The Ravaged Bridegroom: Masculinity in Women. Inner City Books, 1990.

#dark souls#dark souls 3#dark souls theory#dark souls lore#dark souls symbolism#hodrick#holy knight hodrick#velka#velka lore#mound-makers#bonewheel#transposition kiln#gaming alchemy#game entrainment#Julia Kristeva#the thunder perfect intellect#thunder perfect mind#powers of horror#abject#raven

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Goodbye “Andromeda”

The following is a letter I wrote shortly after the Montreal Comic Con 2017 Bioware Panel. I sat on it for a while, but with recent news regarding the fate of Mass Effect: Andromeda, I felt it was pertinent to share this letter.

To the global family who created Mass Effect Andromeda,

I still remember my first ever experience playing a video game. It was a hot December in 1997, and I was still living in Manila, Philippines. We had a small boxy TV with a (maybe) 10-inch screen. That screen gave a pixelated display of my haphazard attempts at killing monsters with the business end of my rocket launcher. Doom was released years prior on the SNES, but it was a completely new thing for me. Me, a (at the time) 5-year old girl, mercilessly conquering over demons, monsters, and other nightmarish things. Macabre as it was, it was the beginnings of my thirst for adventure and of my need to be the hero of my own story.

Since then, I have played many games. I have been an assassin, a brooding teenage rebel trying to save the world, a ninja, a samurai, a street fighter, a car thief, a weird dude with a bandana caught in a plot too complex for my childish mind (not naming names, Metal Gear), a widower trapped in his own psychological nightmare, a well-endowed archeologist, an extremely taciturn physicist, a sith lord, a keyblade master saving worlds... I have been all these lives, personas, and characters. Yet in those myriad experiences, I felt something (for the lack of a better term) missing.

I have since passed the years never really being able to point a finger at it. The sense of a void always came stumbling back after I had finished a game. I tasted power, fulfillment, and the close of a journey only to have it dissipate as a story that never really was mine.

Fast forward years later to the fortuitous year of 2016, when Bioware offered its newest Game of the Year title for a generous discount. It was Dragon Age Inquisition. By then I was twenty-four years old, at the cusp of graduating with a Masters, and suffering from the nagging malaise of a rather bleak election year in the United States. I needed an escape, and seeing as how video games had so steadfastly provided that escape, I took the bait and played what would become the most important game in my life.

This letter is supposed to be about your 2017 title, Mass Effect: Andromeda, so I’ll keep this part brief.

Inquisition was the first game where I was able to make someone who looked like me. Me: a stocky, 5′3 Filipino Chinese Japanese girl with unruly black hair, dull brown eyes, and a face rounder than a baby. Though many other titles before have offered character creators, they either failed to look “realistic” or ended up looking garishly alien. Inquisition’s robust CC made it possible for me to create a protagonist who could not only reflect a woman who resembled me (and people who shared my identity) onto an HD screen. She could also reflect choices, agency, and strength that are rarely afforded to what scant representation Southeast Asians have. I watched my inquisitor grow from reluctant, cloistered heroine to a capable leader who acted with both compassion and courage.

By the time my Inquisitor disbanded the inquisition and joined what would be the lost annals of Thedosian heroes, I inevitably returned to the real word. I was expecting that same, familiar void I felt whenever I finished a game. Yet it didn’t happened. Instead, I fell. I fell so hard for the universe. I couldn’t stop thinking about my characters’ companions, the friendships she made, the relationships she forged, and the love she has earned. I wrote, for one of my Master’s seminars, several papers (which my professors read with glee, might I add) about the resonances of Dragon Age’s in-universe permutations of tragedy and systemic oppression. I wrote about the importance of being able to interact and decide the conclusion of a narrative; to be able to weave a different kind of tale through games where the player could very much inform the tone and setting of a story.

I raved about the game; I joined online communities to keep raving about it; and I produced what content I could to share with these fellow fans from all over the world. I didn’t just play a persona or a character; I played someone who represented what I felt was good about who I was; who acted with a conscientious awareness of what conquering and ruling meant for someone of a previously colonized peoples. It was liberating.

Shortly after my plunge into Inquisition’s fan community, a friend recommended that I try Mass Effect. Since I have already waxed poetic about DAI, I will also keep this very brief. I played all three games shortly after I graduated from my Masters in the winter of 2016. Within a span of a week, I cried, melted, died, reanimated, and cried again. Shepard’s story was complete and whole, and I felt that her accomplishments amplified what i felt about my Inquisition protagonist (especially since the demographic “Asian” had more meaning in this game than it did in a fantasy universe). As you might expect, I waited impatiently and obsessively for Mass Effect: Andromeda, during which time I wondered how on Earth could I have survived the wait had I been a fan all along.

There are many things I could say about my experience playing Andromeda, but I feel I should share with you the most important one.

Thank you.

Thank you for letting me create a beautiful, Filipina hero, who would pave the way for a new galaxy. Thank you for being the game developer who - after nearly 20 years of gaming experience - let me see myself reflected fully, accurately, and beautifully at the forefront of a compelling and epic story. Unlike the previous Bioware games I mentioned, my Ryder (her name is Sarianna :)) was allowed to be young, foolish, and happy. She didn’t constantly bear the yoke of border disputes and religious office as my Inquisitor did. Like Shepard, she was allowed moments of respite and impulsiveness - perhaps even more so than the older protagonist with whom the original trilogy graced us. As a woman who barely saw myself and my identity represented in media, I had a protagonist I could admire, respect, and contribute to the world (no matter how unnoticed she will be in future years).

One of my favorite moments in the game was the penultimate and high stakes scene of the Ryder twin (a Filipino version of Scott) fighting his way with just a pathetic pistol in hand to save his sister. Tears were brimming in my eyes when SAM offered a heartfelt apology at the sacrifice they were forced to make. “I’m sorry Scott,” he said.

And the loving brother could only say, “I am too, SAM” before hitting that button with resolve.

It was a profound and poignant moment about family; about heroes of color who would do anything for each other; and about the fear of losing someone important to you. The fact that characters who represented Filipinos were able to call the shots, exercise agency, and bear the responsibility of leadership gave me so much pride.

My other favorite moment was a romance scene: the drinks Ryder shared with Reyes Vidal on rooftop. It was an emotionally intense moment where two people were able to share in their vulnerability. Do you know how important it is for Latinx players to be able to see a bisexual Latino express the need for recognition, affection, and friendship? The scene broke my heart into a million pieces, because frailty can be a powerful thing and yet it is so often denied to Latino men, whom the media has wronged with constant portrayals of stereotypes of machismo and violence. Reyes was a phenomenal character, and I have to thank your writer Courtney Woods by name for making him possible.

I also cried when the game ended, because I soon returned to that familiar yet now alienating reality where movies, music, and (for the most part) video games didn’t represent anyone with whom I identified. I cried, because my friends and I realized that virtually no one else is letting you wear your race, gender, and sexuality with pride and joy. I cried, because I realized that video games weren’t only cathartic works of fiction wherein I can project my fantasies. They were also fulfillments of personhood. It was you, Bioware, family who made that possible.

Now it goes without saying that nobody and nothing is perfect, and yet the rather disproportionate amount of harsh criticism and backlash the game received was... upsetting to say the least. For one, I felt like society as a whole was rejecting not only the finished product of the game but the potentialities and possibilities latent in such a product. I can’t speak of the technological feats Andromeda was able to accomplish (JUMP JETS ARE LEGENDARY YOU SHOULD BE PROUD!), but I can speak for the fact that Bioware is one of the few developers who proudly held up its fans as the driving force and motivation of their success. Andromeda is a beautiful game, and its predecessors were all masterpieces not only for their technical and artistic achievements but for their social and cultural significance.

When my friend and I left the Bioware panel in the Montreal 2017 comic con, we immediately found our way to a bar in rue Sainte Catherine, where we reveled in the excitement of having seen the people responsible for our joy and passion. Over drinks, I lamented the wasted opportunity of not thanking you personally, so I do it now under the cover anonymity. I do it with words, because I like to think I am better at writing than I am speaking. I do it so I can express to you the indelible mark you left on my life. You gave me a hero who looked like me, and in turn I bonded with others from all over the world who felt that same happiness and gratitude. Yet we also spoke of our hopes: we hoped that people will take Bioware’s direction to further improve representation; to include people of color, people from the LGBT community, and other identities in the creative process. In the field of literary criticism, we often judge a work based on its ability to stage and engage with different audiences across geographic and temporal distances. The Mass Effect franchise was one such formidable work.

Suddenly those twenty years of gaming beforehand folded into a meaningless blur. None of them could ever fill the void of never seeing myself reflected in media. And, as sad it is to say with the recent news of Andromeda’s definitive end, I am not likely to encounter another.

Thank you from the bottom of my heart,

L------ (aka @pathfindersemail)