#the racism and colonialism in this movie...

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

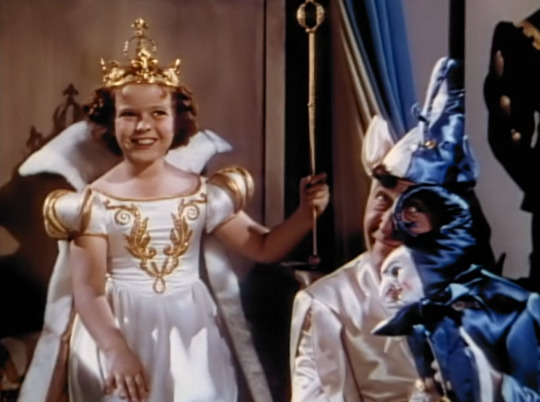

Your face is most familiar. Were you ever on the stage? I seem to associate you with one of the old music halls.

Arthur Treacher as Hubert "Bertie" Minchin The Little Princess (1939)

#arthur treacher#the little princess#shirley temple#sara crew#hubert minchin#bertie minchin#in younger and happier days#bobbling bertie#i'm pretty sure this role was written for him#he's so endearing#mary nash#cesar romero#ram dass#ian hunter#arthur treacher is 90% of the reason i can get through this movie#knocked 'em in the old kent road#wot cher#the racism and colonialism in this movie...

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you not blackwash characters? Idk why you suddenly started doing this but its incredibly annoying.

Could you educate yourself ? Idk why you suddenly decided spit your ignorant opinion but I don't care if you are annoyed.

#the term of blackwash appeared as a slang to contest apparition of blackactor in movie. it contrast the term of whitewash#since you can't educate yourself anon let me tell you with my poor english. deal with it you literally ask.#while “whitewash” because it erases ethnicity and it is problematic considering how ethnocentrism was occidental (colonialism slave etc etc)#“blackwash” is just because black are being more represent on media and it scares white.#yes. so the used of term “blackwash” ans you being annoyed by a character drawn as black just demonstrate#how racism and snowflake you are !#skill issue.#oH nOOOO whIte bEinG leSs rEpresentAted iN mEdIa 😱😱😱😱 tHeY sTeAl eVeRytHiNNG !!!! 😱😱😱😱😭😭😭😱😭#i aM sO oPPRessEd bY soCiety 😞😞😞😱😱😱‼️😞😭

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

The other similarity between Barbenheimer I don't see media outlets covering:

Seriously, what was up with that smallpox joke in Barbie??

#films#barbenheimer#oppenheimer#anti barbie movie#barbie movie#anti greta gerwig#anti christopher nolan#white feminism#settler colonialism#us imperialism#anti native racism#anti indigenous racism

135 notes

·

View notes

Photo

You'll always be here for me, won't you?

#happy valentine's day mira my darling#perioddramaedit#weloveperioddrama#periodedit#perioddramasource#ralph whelan#alice whelan#indian summers#henry lloyd hughes#jemima west#my love feeds on your love beloved#period movies#shitty things i do for love#FOREVER bitter about this show#an actual woc centred show about the ugliness of western colonialism?? ofc you slept on it#when it's not colorblind love cured racism fairytale why to bother#anyway MIRA!!!! here they are our messed up bitter overprotective codependent terrible siblings#AND I WOULDN'T HAVE THEM ANY OTHER WAY#and oh my ralphie the most complex ambitious dreadfully conflicted and arrogant piece of ... meat#hot and mental just as i love my men to be#*kissing henry lloyd's eyelashes*

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was thinking about how to articulate what I hate about the Barbie movie. Like, there are some fun moments (Ken stepping out of view to scream "SUBLIME!" has forever ingratiated itself in my lexicon) but by and large it left me with an increasing sense of frustration that ultimately culminated into a two-part hate.

The first is easy to cover, and it's Mattel's utter failure to put its money where its mouth is, in the form of the movie's portrayal of a fat Barbie vs. the proportions on the fattest actual Barbie that they sell*:

*For the pedants out there, this statement excludes specific, limited characters, like Disney licensed Ursulas. I'm talking about general Barbies for sale on a given day.

The second was harder. For a while I couldn't put it into words, just vague, angry hand gestures about how nothingburger the resolution was.

And then while I was reading A Glossary of Haunting by Eve Tuck and C. Ree, I saw this sentence:

"Listing terrors is not a form of social justice."

And it clicked not just what angered me about this movie, but about a lot of performative, faux woke (fauxke?) media these days. Acknowledgment alone is not the beginning and end of justice. Acknowledgment alone offers no solutions. Acknowledgement alone is how you get Riverdale's tonal whiplash of every second word out of Veronica's mouth ("Toxic masculinity!") vs. noted underage girl Betty Cooper's dead-eyed gang initiation striptease to Mad World.

(And yeah, I know Riverdale is a special case in that it exists in a mirror funhouse dimension of probably salvia-induced dumbassery, but my point stands.)

In the Barbie movie, Gloria lists terrors to the patriarchy-brainwashed Barbies, and that is all that it takes to restore them to their #feminist selves. But the thing is, we the audience already know that patriarchy sucks. This offers us, the people for whom this movie was made, nothing.

Related, second-and-a-half thing that I hated about this movie was the comparison between the Barbies having no defenses against patriarchal thinking and American Indians having no defenses against smallpox. Truly go fuck yourselves Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach. The genocide of my ancestors is not a punchline. (But don't even get me started on how often this sort of casual cruelty randomly pops up in media, or this is going to evolve into an essay on why Brendan Urie deserves to have his vocal cords repossessed for that "manifest destiny" line in High Hopes.)

Anyway, I guess my point is that there was never going to be a Barbie movie with anything of substance to say, because it exists to sell toys and facilitate Mattel's recovery from their Ever-After-High-Disney-License-Revoked-Monster-High-Destroyed-Revenue-Vacuum fiasco. And it did do that. That is, in fact, all that it did.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

i started watching the ritual and it takes place in Sweden!

second horror movie i've seen consisting of people going to Sweden after great personal tragedy only for Sweden to fuck their shit up

which is very very funny to me personally

#new exotic location for horrific events but without the underlying colonialism and racism dropped: sweden#of course this not delving into swedens own problems with colonialism and racism#but i will not assume that this film is about that and that's fine#im watching movies#im watching the ritual

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Big Lit Meets the Mexican Americans: A Study in White Supremacy

HarperCollins tells us: “We publish content that presents a diversity of voices and speaks to the global community. We promote industry and company initiatives that represent people of all ethnicities, races, genders and gender identities, sexual orientations, ages, classes, religions, national origins and abilities.” The New York Times proclaims its dedication to building a “culture of inclusion,” while the University of Arizona’s MFA program commits itself “to proactively fostering diversity and inclusion throughout its curriculum, admissions, hiring, and day-to-day practices.”

Some of these statements may reflect actual practices while others are simply corporate boilerplate. Whether they are sincere or not, the fact remains that most books agented, sold, reviewed, and distributed are mostly written by white people and are, moreover, mostly agented, sold, reviewed, and distributed by other white people. (In fact, the term “diversity,” as used in such statements, seems to reinforce rather than confront the notion that white, cisgender people are the norm and everyone else is a big, indistinguishable mass of otherness. But that’s a different essay.)

Big Lit is virtually a whites-only country club. Everyone knows this. The lack of racial diversity among the people who populate Big Lit is an open secret. The Big Five — Penguin Random House, Hachette, Macmillan, Simon and Schuster, and HarperCollins — is still where it’s at in terms of getting maximum exposure, resources and mainstream acceptance. Big Lit can consign to near invisibility the work of entire communities of writers it decides not to take up.

This essay is a kind of case study of the Mexican-American literary community, a community whose writers Big Lit rarely takes up. But I don’t mean to offer another lecture about Big Lit’s lack of diversity (well, not entirely). Rather, I want to examine how the ideology of white supremacy works to brand an entire population of nonwhite people — here, Mexican Americans — as inherently inferior to whites, how that message is reinforced by means both legal and extra-legal, how it seeps into literary culture, and, how, ultimately, literary culture (i.e., Big Lit) consciously or unconsciously views this population through the lens of those white-supremacist beliefs.

This ingrained and complex racism can’t be ameliorated by platitudes about diversity or tokenistic representations of “diverse” populations.

Part One

When Donald Trump called Mexican immigrants “rapists” during the announcement of his 2016 presidential bid, he was strumming a very old chord in white America’s consciousness. Since the mid-19th century, the denigration of Mexicans and, by extension, Mexican Americans has been an ongoing project of white America. The pivotal point was the US invasion of 1848 and the forcible appropriation of half the territory that comprised the nascent Mexico. Then as now, Mexico saw the war for what it was: an unprovoked and unprincipled land grab. As a Mexican newspaper at the time thundered: “A government […] that starts a war without a legitimate motive is responsible for all its evils and horrors. The bloodshed, the grief of families, the pillaging, the destruction. […] Such is the case of the U.S. Government, for having initiated the unjust war it is waging against us today.”

Fueled by the almost religious conviction that the United States was destined to occupy the entire North American continent, Anglo America embarked on the near extermination of indigenous people and the conquest of Mexico. From the outset, Manifest Destiny was a racialist doctrine.

As one historian observes:

By 1850 the emphasis was on the American Anglo-Saxons as a separate, innately superior people who were destined to bring good government, commercial prosperity, and Christianity to the American continents and to the world. This was a superior race, and inferior races were doomed to subordinate status or extinction.

America’s true motives were laid bare in a contemporary North American periodical, the American Whig Review: “Mexico was poor, distracted, in anarchy and almost in ruins — what could she do to stay the hand of our power, to impede the march of our greatness? We were Anglo-Saxon Americans; it was our ‘destiny’ to possess and to rule this continent — we were bound to it.” (Mid-19th-century Mexico was a troubled, unstable polity but still: If your neighbor’s house is on fire, is the morally appropriate response to break in and steal everything of value you can lay your hands on?)

At the end of the war, over 100,000 Mexicans were trapped on what was now the American side of the border. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo guaranteed that these captive people would become naturalized American citizens, with all the rights and privileges thereof, and that their property rights would be respected. Those promises evaporated almost as soon as the ink was dry on the treaty. The promised enfranchisement, it turned out, was only federal, not state citizenship. This ploy allowed the states that were carved out of annexed territory to limit citizenship to something called “white Mexicans.” As for the property right guarantee, Mexican property owners became bankrupt in American courts when fighting off American predators and squatters who would trespass and forcefully stay on their private property.

Arising at the same time was Western genre fiction, emerging first in the form of dime novels. This genre provided the most popular and widely distributed representations of Mexicans and Mexican Americans from the mid-19th century well into the 20th. Its practitioners included writers like Zane Gray, O. Henry, and Stephen Crane, as well as countless pulp writers. Film and, later, television perpetuated these representations and gave them even wider currency. Central to the Western genre was the theme of Mexican racial inferiority, which these narratives used to justify the invasion and conquest of Mexico; indeed one author called it, "conquest fiction."

Much of early Western fiction originated or was set in Texas, always a hotbed of particularly virulent anti-Mexican sentiment. Mexico had initially welcomed Anglo settlement in Texas, but the Anglos who arrived tended to be slave-owning Southerners with reactionary views about the purported inferiority of darker-skinned people. Mexico abolished slavery in 1829. This contributed to the Anglo-led secession of Texas from Mexico and the founding of the Texas Republic; basically, the white Texans wanted to maintain slavery.

Their attitudes toward their erstwhile Mexican hosts was summed up by Texas patriot Stephan Austin, who on one occasion described Mexicans as a “mongrel Spanish-Indian and negro race,” and on another as “degraded and vile; the unfortunate race of Spaniard, Indian, and African is so blended that the worst qualities of each predominate.”

Antebellum pulp Westerns with titles like Mexico versus Texas, Bernard Lile: An Historical Romance, and Piney Woods Tavern; or, Sam Slick in Texas created a set of Mexican stereotypes that prevailed well into the 20th century, among them the lazy peon, the evil bandido, and the licentious señorita. In these works most Mexican males are “segregated into two distinctly inferior types: peon servants and mestizo bandidos. As “half-breeds,” the mestizo bandidos are “a cut above the peons,” but “have no moral scruples. […] When the American heroes finally ‘unmask’ these poseur gentlemen and expose their wickedness, they either kill them or hurl them back across the color line into ‘brownness’ and disgrace.” The distaff side is represented by “Mexican woman […] graced with voluptuous figures but burdened by loose moral principles.”

Higher-brow publications like The Atlantic and Scribner’s Magazine were no less derogatory. An 1899 article in The Atlantic entitled “The Greaser” portrayed its Mexican-American subject as “the mestizo, the Greaser, half-blood offspring of the marriage of antiquity and modernity.” A travel piece in an 1894 issue of Scribner’s Magazine described the borderland between Texas and Mexico as “The American Congo”; the piece is a veritable encyclopedia of racist stereotyping, including this Trumpian observation: “The Rio Grande Mexican is not a law-breaker in the American sense of the term; he has never known what law was and he does not care to learn; that’s all there is to it.”

These caricatures of Mexican Americans were amplified and even more widely distributed as early moviemakers discovered the appeal of Westerns. Mexicans were, once again, cast as the dark-skinned foils to upright Anglo heroes as summarized by an author:

[F]ilm titles and advertising made open use of the word greaser, at least up to the 1920’s: The Greaser’s Gauntlet, The Girl and the Greaser, Broncho Bill and the Greaser, The Greaser’s Revenge, Guns and Greasers, or, bluntly, The Greasers. The artistic and cultural sensitivity of these films match their titles. If adventure stories, they feature no-holds-barred struggles between good Americans and bad Mexicans. The cause of the conflict is often vaguely defined. Some greasers meet their fate because they are greasers. Others are on the wrong side of the law. Others violate Saxon moral codes. All of them rob, assault, kidnap, and murder with the same wild abandon as their dime-novel counterparts.

These silent-era representations continued into the talkies.

Brownness, stupidity, laziness, cowardice, lawlessness, and sexual immortality: these became the signifiers of Mexicans in white America’s consciousness, reinforcing the notion that Mexicans are inferior to white people. This inferiority was race-based — that is, Mexicans were presumed to be inherently and in some inchoate sense biologically less intelligent, capable, and moral than white people.So deeply embedded are these cultural images that, after the death of the Western as a popular genre in books, movies, and TV, they simply shape-shifted into more contemporary versions.

Instead of the bandidos of yore, Mexican-American men transformed into gangbangers and drug dealers; the lazy peons became grocery-cart-pushing homeless people and hapless drug addicts; the flashing-eyed señoritas now tottered around suggestively on Fuck Me Pumps uttering heavily accented malapropisms. Often, however, these stereotypes don’t speak at all. In movies and on TV, you see brown people silently pushing laundry carts, pruning rose bushes, or stacking dishes into an industrial dishwasher, a sepia background against which the whiteness — and, thus, the superiority — of the real heroes and heroines gleams all the more brightly.

Part Two

Before Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, there was Mendez v. Westminster in 1946, the first federal court decision striking down school segregation. Let me explain.

California’s Orange County had set up “Mexican schools,” which all children of Mexican descent were required to attend from first to fourth grade. The ostensible reason was that they couldn’t speak English, but all Mexican-American children were forced into these schools regardless of their fluency. By the time the Mendez and five other families sued, these schools had 5,000 students. In the then-prevalent racial binary of black versus white, Mexicans were grudgingly considered “white.” This meant the plaintiffs couldn’t allege racial discrimination. Instead, they argued that the segregation of public schools impermissibly discriminated against their children based on ancestry and presumptive language deficiency.

In short, Orange Country’s segregation scheme wasn’t authorized by state law; thus, by extension, neither were other forms of segregation imposed on Mexican Americans in California by a comprehensive set of statewide Jim Crow–like laws. To summarize the situation: By the 1920s, many Southern California communities had established ‘Mexican schools’ along with segregated public swimming pools, movie theaters, and restaurants.” (On a personal note, I can testify that my mother remembers being turned away from a Sacramento public swimming pool sometime in the late 1940s because she was — and is — undeniably mestiza in appearance.)

From the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries, whites used a combination of discriminatory legal and terroristic extra-legal tactics against Mexican Americans. Mexican Americans were disenfranchised, faced residential and education segregation, were denied the use of public facilities, and were in danger of being lynched. Yes, lynched — 571 ethnic Mexicans were lynched between 1848 and 1928; in addition, the Texas Rangers summarily executed at least another 500 Mexicans without trial.

As has repeatedly been the case, these discriminatory legal measures and extra-judicial assaults corresponded to high tides of Mexican immigration. In this time of history, Mexican immigration was between 1900 and 1930 - many, like my great-grandparents, refugees. Nativist whites such as Madison Grant, author of the influential The Passing of the Great Race, deplored this invasion by a “mongrel race.” White America’s attitudes toward Mexican immigration have always been both exploitative and ambivalent. On the one hand, these immigrants are useful because they serve as a cheap source of agricultural labor in the West; however, because they are members of an inferior “mongrel race,” they have to be closely monitored and firmly kept in place.

The ease with which bare tolerance could shift to active hostility was dramatically illustrated during the Great Depression. During this period, an estimated 400,000 Mexican Americans, 60 percent of them American citizens by birth or by naturalization, were forcibly repatriated to Mexico. The pretexts given were that Mexican Americans were taking scarce jobs away from white Americans and were a drain on government relief assistance. (Sound familiar?)

In a frenzy of anti-Mexican hysteria, wholesale punitive measures were proposed and taken by government officials at the federal, state, and local levels. Laws were passed depriving Mexicans of jobs in the public and private sectors. Immigration and deportation laws were enacted to restrict emigration and hasten the departure of those already here. Contributing to the brutalizing experience were the mass deportation roundups and reparation drives. […] An incessant cry of “get rid of the Mexicans” swept the country.

Mexican Americans never passively consented to their victimization by white Americans. Following the end of the Mexican-American War, they fought the unlawful seizure of lands guaranteed to them under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in American courts many being unsuccessful and losing their private property and homes to Americans who illegally squatted on their land and protested the decisions by California, Texas, and Arizona to limit citizenship to “white Mexicans.” In the 1930s, long before the establishment of the United Farm Workers, Mexican agricultural workers organized themselves into unions and went on strike in California, Arizona, Idaho, Washington, and Colorado; they were met with brutal suppression. “[w]ith scarcely an exception, every strike in which Mexicans participated in the borderlands in the thirties was broken by the use of violence and followed by deportations. In most of these strikes, Mexican workers stood alone, that is, they were not supported by organized labor.”

The 1960s and ’70s saw the birth of the Chicano Movement — emphasizing racial pride and resistance to racism. That movement also gave birth to a body of literature that is now acknowledged to contain many of the ur-texts that form the basis of Chicano/a and Latinx studies programs.

And now? Who are these Mexican Americans? While their numbers continued to be greatest in the western states, there are Mexican-American communities in every state in the union, with a significant presence in the Midwest and a growing presence in the South. In contrast to the aging white population, a 2007 survey revealed only six percent of “Hispanic Americans” to be 65 or older; the comparable percentage for whites was 15 percent. Thus, a brown workforce increasingly supports white retirees.

Contrary to the stereotype that most Americans of Mexican descent are recent immigrants, the majority of Mexican Americans are native-born. That percentage will only increase because Mexican immigration — even before Obama’s massive deportations and Trump’s war against immigrants — has been steadily decreasing, as a 2015 Pew Research Poll shows. That poll also dispels another stereotype, showing that almost 90 percent of native-born Mexican Americans are proficient in English. Moreover, Pew Research has also established that 83 percent of all Latinos and 91 percent of Latino millennials (including, of course, Mexican Americans) get their news in English.

The Department of Education reported a 126 percent jump in Latino students entering college between 2000 and 2015.

In short, Mexican Americans comprise a youthful, increasingly well-educated, largely native-born and English-proficient, aspirational community.

Yet, despite all this, Mexican-American representation in mainstream American culture, when it appears at all, remains either tokenistic, stereotypical, or both. In film, television, and books this emergent community is still largely ignored.

Part Thee

As part of my research for this essay, I looked at the course syllabi for a half-dozen courses in Latinx or Chicano literature from colleges across the nation, in order to see which Mexican-American works and writers scholars deem canonical. This is the list I came up with (virtually all these books were taught at more than one school):

Americo Paredes, George Washington Gómez (written in mid-’30s; published 1990)

Tomás Rivera, … y no se lo tragó la tierra/and the earth did not devour him (1971)

Rudolfo Anaya, Bless Me, Ultima (1972)

Sandra Cisneros, The House on Mango Street (1984)

Arturo Islas, The Rain God (1984)

Ana Castillo, The Mixquiahuala Letters (1986)

Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987)

Alejandro Morales, The Rag Doll Plagues (1991)

Helena Maria Viramontes, Under the Feet of Jesus (1995)

Norma Elia Cantú, Canícula (1995)

Reyna Grande, Across a Hundred Mountains (2006)

What most of these books have in common is that, with two exceptions, none were published by the Big Five or their predecessors; instead, almost all were originally published by small presses. While some were later picked up by Big Five publishers for paperback editions, most are still being kept in print by independent or university presses. Even The House on Mango Street, now generally recognized as a classic work of American fiction was originally published by Arte Público Press.

What this illustrates is Big Lit’s long history of ignorance or indifference to Mexican-American writers and the Mexican-American experience in this country. Yet to read any of these books is to experience a vision of America at once unique and familiar, for each in its own way tells a quintessentially American story. It’s just not a white American story. Yet very few Mexican-American writers find a place in Big Lit.

Big Lit is a very, very white place. White people overwhelmingly populate the Big Five; as the now-famous publishing diversity study by Lee & Low Books reported, 79 percent of people employed in the industry in 2015 were white and only six percent Latino.

A 2019 salary survey of the publishing industry undertaken by Publishers Weekly put the percentage of white employees at 84 percent.

Librarians, who are crucial to the sale and dissemination of literary texts, are also overwhelmingly white. A February 2013 editorial in The Library Journal entitled “Diversity Never Happens” observed that “Hispanics are some of the strongest supporters of libraries, and yet they continue to be thinly represented among the ranks of librarians.” ”The editorial cites statistics showing that, while Latinos/as are more likely to use libraries on a monthly basis than whites, only eight percent of the 118,666 credentialled librarians were Latino/a. A 2017 statistical study reports that “89 percent of librarians in leadership or administration roles were white and non-Hispanic.”

Similar demographic information for other realms of Big Lit appears to be unavailable. No one seems to be keeping any record of what percentage of the writers who are reviewed — or the reviewers who review — in The New York Times Book Review, Publishers Weekly, or Booklist, for example, are white. In a 2012 study of book reviews published by The New York Times, it was found that 90 percent of the books reviewed in 2011 were by white writers. White writers are vastly and disproportionately overrepresented both as reviewers and subjects of reviews in comparison to writers of color.

There are over 1,300 literary agents in the United States, most of them in New York, but I could find no statistics about their racial demographics. I did find an anecdotal study from the late 1990s, in an article called “Dearth of Hispanic Literary Agents Frustrates Writers.” The asserted that neither the literary agencies canvassed in The Literary Market Place nor the roster of agents in the Association of Authors’ Representatives listed a single Latino/a agent. The number is now likely greater than zero, but I have no doubt that the profession remains at least as white as publishing.

Similarly, there are, to my knowledge, no statistics about the racial composition of students and faculty at the many MFA programs around the country. There are, however, plenty of anecdotal accounts of how students of color are received in these programs. The essay “The Student of Color in the Typical MFA Program” powerfully summarizes these experiences. According to the essay, if a student of color objects to a racist depiction in a work by a white student, she or he risks being accused of censorship, or else the objection is dismissed as a political argument outside the bounds of literary analysis. Moreover, the student’s objection often triggers guilt or anger in white students and teachers because it challenges their cherished beliefs that they are not racist, and so they respond by branding their colleague a troublemaker.

The whiteness of Big Lit has practical consequences for Mexican-American writers. If virtually every agent, editor, book reviewer, and librarian is white, then such writers will have a much harder time finding representation, getting published, being reviewed and recommended. Therefore, there will be fewer Mexican-American voices in the literary culture. And this, in turn, means that there will be fewer counterbalances to the racist depictions of Mexican Americans in mainstream culture — portrayals that allow Trump and other white supremacists to continue to vilify a large segment of the American population.

White progressives in Big Lit may lament this situation, but they take no responsibility for the perpetuation of white privilege, if not white supremacy, in literary culture. Why? Because that privilege benefits them.

Part Four

The obvious issue is this: the white people who make up Big Lit live in a culture whose history and practice enshrines the belief that Mexican Americans are inherently inferior to whites, and fundamentally they’re okay with that.

The standard American university education continues to emphasize the primacy of white writers and their experience. To achieve a literary culture that truly reflects America’s multiracial society first requires an acknowledgment that Big Lit’s views regarding the putative universality of white experience are rooted in the ideology of white supremacy.

Other commentators have noted that the Big Five apply a double standard when acquiring and retaining writers of color. Writers of color aren’t allowed to fail the same way white writers are allowed to. If one book by a white author doesn’t sell, no one at the publishing house says they shouldn’t acquire any books by white authors the next season. But if a book by a Mexican, for example, doesn’t sell, the publisher may take its sweet time in “taking a risk” on another.

But aren’t disappointing sales a good reason to not continue publishing a particular writer or kind of book? That would be an acceptable explanation if the same standard applied across the board. To amplify the point above, however, if a white novelist from Brooklyn fails to make back her advance, that doesn’t mean her publisher won’t acquire other white Brooklyn novelists or even refuse to publish that particular author’s next book. Moreover, and here’s where the argument really falls apart, most books fail to make money, at least initially. The editor-in-chief at One World noted at the LARB/USC publishing workshop in July 2019 that 10 percent of books published by the Big Five support the remaining 90 percent. If most books are a risk, why is that risk disproportionately attributed to work by writers of color?

“Hispanics don’t read.” Whether a Big Five editor ever actually uttered those words, it is widely believed by the Latino/a community to be a sentiment Big Lit harbors about us. According to a nationally syndicated columnist after a day or two after a book's release, she got a call from a New York Times reporter asking her how well the book would sell. The reporter jumped in to the first question: ‘Why don’t Latinos read?’”

The Big Five, like the larger media culture, are not representative of the U.S. but of the limited tastes of the elite of Manhattan and certain areas of Brooklyn. These cultural gatekeepers — publishers, editors, agents — are simply unfamiliar with Latinos. A bias seeps into their decision making, based again on the unwarranted assumption that Latinos don’t read.

The notion that Mexican Americans and other Latinos/as don’t read is clearly rooted in assumptions of racial inferiority — e.g., immigrant, poor, less educated, less intelligent.

In short, the ideology of white supremacy is at the root of Big Lit’s “diversity problem.” The reason Big Lit doesn’t seek out, encourage, publish, and promote Mexican-Americans writers is because the people who work in it don’t really believe that Mexican Americans are the intellectual or creative equals of — or that their stories have the same value as those of — white writers.

Hey Big Lit: You think the Mexican-American experience can be expressed in a handful of stereotypes, most of which emphasize the intellectual and moral inferiority of Mexican Americans. While we’ve had to figure out white people, you’ve never had to think past your stereotypes of us. While we’ve been paddling upstream against the current of your white-supremacist assumptions, you’ve been lazily drifting along in them. You know nothing of our historical experience, while all of us have had the false narrative of white American triumphalism forced down our throats. And while you mouth your support for “diversity,” any such initiatives that you control will be, at best, tokenistic. Indeed, the concept of “diversity” itself may simply be an attempt on your part to deflect attention away from white-supremacist assumptions by turning the issue of race into a discussion about mere representation.

There can be no real diversity without a real and meaningful redistribution of power.

It’s almost impossible to imagine that the white people who compose somewhere north of 79 percent of Big Lit would ever voluntarily and actively agree to — and work toward — an industry where their percentage slipped below 50 percent. When it comes right down to it, Big Lit, you’re much more invested in maintaining your privilege, and passing it down to your white heirs, than in helping to create a literary culture that genuinely represents the fullness of the American project — warts, near-genocides, invasions, lynchings, and all.

Of course, we’ll keep on calling you out, because you do respond sometimes — out of guilt, if nothing else. Maybe you’ll publish a few more Mexican-American writers, review a book or two about the Mexican-Americans experience, hire a Mexican-American writer to teach in your MFA program, highlight the works of Mexican Americans in your bookstore when it’s not “Hispanic Heritage Month.” We will also will continue to remind you that you will find yourself listed among the collaborators, right up there with the Scribner’s Magazine editor who commissioned “The American Congo.”

Source

#🇲🇽#usa#united states#racism#discrimination against Mexicans#imperialism#colonization#colonialism#history#mexican history#mexico#mexican american war#remember the alamo#texas#movies#books#representation#tv shows#segregation#Mendez v. Westminster #california#lynching#texas rangers#white supremacy#eugenics#immigration#mexican revolutiom#great depression#arizona#idaho

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

@what-alchemy added:

#i think this shift also has everything to do with racism#the broader US narrative appropriates folklore from Black enslaved populations#and then reconceptualizes it as a threat to their (white) personhood to be suppressed in the most violent terms#boy if that aint the history of this country in a nutshell

This is all true, but I think if anything it undersells the openly colonialist and fascist underpinnings of the U.S. (and UK) zombie movie narrative. The genre is arguably the ugliest example of terra nullius post-apocalyptic fantasy, a genre in which apocalyptic events provide a pretense for "culling" undesirables — even within one's own community — and recolonizing entire territories in some ostensibly purer form. The undesirables are reframed as more or less mindless monsters who cannot be rehabilitated or negotiated with, only destroyed, and insofar as their presence reflects some implicit right or claim to the territory, the nullification of that claim is made both necessary and implicitly righteous by the inhumanity of their new, irreversible condition. For example, if you find undead shambling around in what in life was their own house, the narrative makes it both justifiable and appropriate for you to destroy those former inhabitants and claim their belongings (if not the home itself) for your own more urgent needs.

Perhaps the most blatant example of this vicious narrative trend is THE WALKING DEAD comic (I have seen almost none of the TV shows and don't want to), which is startling in its increasingly explicit celebrations of fascism. I have no idea if Kirkman saw it that way, perhaps not, but the narrative has its protagonist, Rick Grimes, repeatedly embracing fascist actions and ideals, which are rewarded each and every time, and which the finale suggests eventually made possible the recreation of a "civilized" world with an unsettling resemblance to the America of the late 19th century.

"The shift from the Afro-Caribbean zombie to the U.S. zombie is clear: in Caribbean folklore, people are scared of becoming zombies, whereas in U.S. narratives people are scared of zombies. This shift is significant because it maps the movement from the zombie as victim (Caribbean) to the zombie as an aggressive and terrifying monster who consumes human flesh (U.S.). In Haitian folklore, for instance, zombies do not physically threaten people; rather, the threat comes from the voduon practice whereby the sorcerer (master) subjugates the individual by robbing the victim of free will, language and cognition. The zombie is enslaved."

— Justin D. Edwards, "Mapping Tropical Gothic in the Americas" in Tropical Gothic in Literature and Culture.

Follow Diary of a Philosopher for more quotes!

#comics#teevee#movies#hateration holleration#racism#colonialism#terra nullius#the walking dead is basically like watching someone's#gurps fascism ttrpg campaign#the undead are even described as “herds” that must be culled

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Text

dune is such a white savior/orientalist/racist movie yet still so many ppl praise it like its some kind of masterpiece what tf wrong w you ppl

#dune#dune part two#racism in movies#sexism in movies#fuck racism#fuck colonialism#fuck white supremacy#fuck white male directors#feminism

1 note

·

View note

Text

Also that quote Oppenheimer used is from the Hindu holy text the Bhagavad Gita. The furor in India by Hindu nationalists over it being used during a bedroom scene in the movie is stupid, but y'all still need to stop making off with bits and pieces of other people's religions with zero understanding and commodifying them, let alone using it as merch for a movie about genocide.

okay okay so like i don’t wanna kill the party but i just saw an instagram shop selling a shirt that says now i am become death the destroyer of worlds in barbie font and i just sigh i just like i get the novelty of barbie and oppenheimer weekend but i have got to stress the bomb changed the entire world forever and wiped out over a quarter of a million people i think maybe we gotta kinda take a step back here when we start selling it as if it’s fun hot girl summer fodder

#i hate this movie so much#it's making white Jews attack Hispanos and Indigenous and Asian people for criticizing it#giving antisemites ammunition#with Black‚ brown and Indigenous Jews caught in the middle of it all#Christopher Nolan has been a racist misogynist piece of shit his whole career and dickrider for cops and the military#so it makes sense he made this movie#while refusing to cast a Jew to play Oppenheimer and erasing all the Black scientists that worked on the Manhattan Project#and yes it's important to show that the talent and intellect of Western BIPOC#have always been instrumental in the imperialist colonial violence inflicted on its own marginalized people and the rest of the world#representation is about being reflective of real life not using a colour line to make moral dichotomies#if your support for PoC having the same rights and opportunities as everyone else is contingent on unproblematic behaviour#then you're a racist and your support more dangerous than its worth#oppenheimer#military industrial complex#racism#downwinders#genocide#indigenous rights#colonial violence#cultural appropriation#knee of huss

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

i am soooo tired of seeing skinny people i am so over it its so everywhere and everything on tiktok on ads on book covers in movies in tv shows, politics, fucking music even. its endless, infinite, exhausting. isn't there something more than this? this can't be it. like how did i end up in a version of the world where a fat woman being a romantic lead in a mid period drama on Netflix is a win? and how is she still basically the only fat person on that show? how are there films and tv shows praised for diversity that don't have a single fat person in the cast?? how how how HOW. the majority of people in the world aren't even skinny. most people in the world aren't thin white people! its crazy its so fucking insane how colonialism, ableism and racism has created a phantasm in which we all accept that pretending fat people don't exist and punishing them when they do is normal and fine. like, imagining a world where fatphobia doesn't exist is actually unimaginable and painful and i truly can't think about it too much without tearing the hair off my entire body

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

#Already lost#Misogyny#Racism#Sexism#Colonialism#Patriarchy#Toxic masculinity#Feminism#Feminist#black feminism#Gender#barbie 2023#barbie the movie#barbie movie#black barbie#Authenticity#Systemic sexism#systemic oppression#systemic inequality#systemic change#system icons#unconscious bias#microaggressions#emotional abuse#video#youtube#black is beautiful#black lives matter#black lives fucking matter#black lives have always mattered

0 notes

Text

watched infinity pool yesterday. it was alright. had ideas. did not expand on them.

#felt like it was trying to discuss/bring up colonialism and racism in the tourism/vacation industry. absolutely did not follow through.#watched in 2023#angel.txt#for movies i watch i would usually reblog gifsets or images but honestly i cant be bothered with movies that are just mid/bad.#only gonna do that for good ones.

1 note

·

View note

Text

So I went to the timeline where the Roman empire never fell—no, they eventually stumbled back towards a vaguely egalitarian Republic, there's still an emperor but he's essentially prime minister—is that they—yeah they got rid of slavery. They still have a weirdly fond view of the ancient empire, but it's like any other society with continuity with a slaveholding version—they do the — no they were majority Catholic but it's not strictly enforced. I didn't have time to get the historical breakdown—they all do—again, didn't spend time learning history, I don't know what age of sail colonialism was like for them. I saw some black guys and some Indian guys and they seemed chill, I didn't have time to interrogate them about systemic racism—they do the salute all the time. Yeah with the raised arm. It's normal there. You think it'd be like when you go back to the 20s and you see a Charlie chaplain movie but no it's super off-putting the whole time. Honestly just skip it and go for the Song or Yuan Dynasty timelines, much less weird.

875 notes

·

View notes