#the phenomenology of the spirit of america

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

261 (more) days in America

gliding on the carpet of leaves

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

magic-backed transport authority

mbta moment

#boston#the phenomenology of the spirit of america#venerative phillip eng fanposting for delayed green line-stuck teens

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

MORTIMER ADLER’S READING LIST (PART 2)

Reading list from “How To Read a Book” by Mortimer Adler (1972 edition).

Alexander Pope: Essay on Criticism; Rape of the Lock; Essay on Man

Charles de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu: Persian Letters; Spirit of Laws

Voltaire: Letters on the English; Candide; Philosophical Dictionary

Henry Fielding: Joseph Andrews; Tom Jones

Samuel Johnson: The Vanity of Human Wishes; Dictionary; Rasselas; The Lives of the Poets

David Hume: Treatise on Human Nature; Essays Moral and Political; An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

Jean-Jacques Rousseau: On the Origin of Inequality; On the Political Economy; Emile, The Social Contract

Laurence Sterne: Tristram Shandy; A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy

Adam Smith: The Theory of Moral Sentiments; The Wealth of Nations

Immanuel Kant: Critique of Pure Reason;��Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysics of Morals; Critique of Practical Reason; The Science of Right; Critique of Judgment; Perpetual Peace

Edward Gibbon: The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire; Autobiography

James Boswell: Journal; Life of Samuel Johnson, Ll.D.

Antoine Laurent Lavoisier: Traité Élémentaire de Chimie (Elements of Chemistry)

Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison: Federalist Papers

Jeremy Bentham: Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation; Theory of Fictions

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Faust; Poetry and Truth

Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier: Analytical Theory of Heat

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: Phenomenology of Spirit; Philosophy of Right; Lectures on the Philosophy of History

William Wordsworth: Poems

Samuel Taylor Coleridge: Poems; Biographia Literaria

Jane Austen: Pride and Prejudice; Emma

Carl von Clausewitz: On War

Stendhal: The Red and the Black; The Charterhouse of Parma; On Love

Lord Byron: Don Juan

Arthur Schopenhauer: Studies in Pessimism

Michael Faraday: Chemical History of a Candle; Experimental Researches in Electricity

Charles Lyell: Principles of Geology

Auguste Comte: The Positive Philosophy

Honore de Balzac: Père Goriot; Eugenie Grandet

Ralph Waldo Emerson: Representative Men; Essays; Journal

Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Scarlet Letter

Alexis de Tocqueville: Democracy in America

John Stuart Mill: A System of Logic; On Liberty; Representative Government; Utilitarianism; The Subjection of Women; Autobiography

Charles Darwin: The Origin of Species; The Descent of Man; Autobiography

Charles Dickens: Pickwick Papers; David Copperfield; Hard Times

Claude Bernard: Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine

Henry David Thoreau: Civil Disobedience; Walden

Karl Marx: Capital; Communist Manifesto

George Eliot: Adam Bede; Middlemarch

Herman Melville: Moby-Dick; Billy Budd

Fyodor Dostoevsky: Crime and Punishment; The Idiot; The Brothers Karamazov

Gustave Flaubert: Madame Bovary; Three Stories

Henrik Ibsen: Plays

Leo Tolstoy: War and Peace; Anna Karenina; What is Art?; Twenty-Three Tales

Mark Twain: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn; The Mysterious Stranger

William James: The Principles of Psychology; The Varieties of Religious Experience; Pragmatism; Essays in Radical Empiricism

Henry James: The American; ‘The Ambassadors

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche: Thus Spoke Zarathustra; Beyond Good and Evil; The Genealogy of Morals; The Will to Power

Jules Henri Poincare: Science and Hypothesis; Science and Method

Sigmund Freud: The Interpretation of Dreams; Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis; Civilization and Its Discontents; New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis

George Bernard Shaw: Plays and Prefaces

Max Planck: Origin and Development of the Quantum Theory; Where Is Science Going?; Scientific Autobiography

Henri Bergson: Time and Free Will; Matter and Memory; Creative Evolution; The Two Sources of Morality and Religion

John Dewey: How We Think; Democracy and Education; Experience and Nature; Logic; the Theory of Inquiry

Alfred North Whitehead: An Introduction to Mathematics; Science and the Modern World; The Aims of Education and Other Essays; Adventures of Ideas

George Santayana: The Life of Reason; Skepticism and Animal Faith; Persons and Places

Lenin: The State and Revolution

Marcel Proust: Remembrance of Things Past

Bertrand Russell: The Problems of Philosophy; The Analysis of Mind; An Inquiry into Meaning and Truth; Human Knowledge, Its Scope and Limits

Thomas Mann: The Magic Mountain; Joseph and His Brothers

Albert Einstein: The Meaning of Relativity; On the Method of Theoretical Physics; The Evolution of Physics

James Joyce: ‘The Dead’ in Dubliners; A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; Ulysses

Jacques Maritain: Art and Scholasticism; The Degrees of Knowledge; The Rights of Man and Natural Law; True Humanism

Franz Kafka: The Trial; The Castle

Arnold J. Toynbee: A Study of History; Civilization on Trial

Jean Paul Sartre: Nausea; No Exit; Being and Nothingness

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: The First Circle; The Cancer Ward

Source: mortimer-adlers-reading-list

#reading list#long post#mortimer adler#text#saved posts#works#books#so much to read#philosophy#literature#dark academia#light academia

8 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Calvinism (Introduction to John Calvin's Reformed Theology)

COMMENTARY”

The US military has a huge problem, currently, with the Calvinism of the Pro-Life Evangelical chaplains that have come to dominate the military community. The TULIP doctrine is grounded entirely on the Total Depravity of Eve without mitigation of the cross which is a primary contributor of the sexual assault in the military and the rate of suicide among Navy women, in particular, and combat veterans generally. Kurt Cobain was a canary in the coal mine of youthful suicide driven by Calvinism.

in addition, the Calvinism of the Salvation Gospel of Campus Crusade for Christ has been politically aligned with what has become the January 6 agenda since Bill Bright founded it. The USAF has a particularly grim problem with their academy located in the heard of Jesus Freak country in Colorado Springs. Among other things, the only women available for dating by the cadets are all Pro-Life Evangelicals.

Just for the record, Hegel was a Lutheran who rejected Calvinism specifically because it rejected the freedom of the spirit central to the Phenomenology of the Spirit. The US military is Hegelian in aspect and, just for the record, the injection of Calvinism into the military community violates Calvin's own model of the separation of church and state. Calvinism is deliberately insurgent and was the proximate cause of the English Civil War, which is why George Washington and his staff were deists and, as Church of England, abhorred the religious "enthusiasm" of the Calvinist Pentecostal tendencies.

Just for the record, the Presbyterian Church is the single most institution of structural racism in America, going back to Woodrow Wilson, George Gilder's "Wealth and Poverty", a Supply Side manifesto, was marketed specifically to exploit the white supremacist DNA of the Presbyterian concept of Christian stewardship, in that "Wealth" represents the righteousness of WASPs while "Poverty" is associated with black folks. It's that simple. Calvin's logic is an example of Garbage In, Garbage Out.

0 notes

Text

Terror White

“You’re either with us or against us.” - George W. Bush

1.

On January 6th, 2021, domestic terrorists invaded the Capital Building in an act of political insurrection. Their intent was to overthrow the will of the people by preventing certification of a free and fair democratic election. They did so at the behest of their political leader (who was impeached a second time for inciting this gross transgression of his oath of office), other voices in their party - the so-called GOP - and talking head agitators inhabiting the far-right media echo chamber. Nearly to a man, a woman, a they, each of these terrorists were white.

Images of ‘good old boys’ traipsing down the halls of the people’s house waving confederate battle flags, kicking feet up on the Speaker’s desk, walking off with public property or smearing their shit on the floors pervaded the internet. These images provided by the villains themselves, posted shamelessly to social media profiles.

As a result of this treasonous, insulting, juvenile, despicable, and ultimately futile effort five people died. Even still, hours after the fact, a majority of members of the so-called GOP voted in accordance with the will of these terrorists. They voted to overturn the results of a free and fair election in the world’s oldest modern democracy. They did so because they believed there were serious ‘concerns’ (‘concerns’, let’s be clear, that started with them and like the Ouroboros, ended up with the confusing, if unhygienic, phenomenon of not knowing where their mouths or assholes ended or began) with the 2020 presidential election. After over 60 court cases arguing that point only one was ruled in their favor. None of the 50 States comprising our union found any evidence of wide-spread fraud. Indeed, a federal agency tasked with monitoring election security stated unequivocally that the presidential election of 2020 was one of the most secure in a generation.

And yet? There they were. Spouting conspiracy theories, assaulting police officers (those stalwart stewards of the ‘law & order’ they otherwise claim to love), brandishing spears and bearskins, stealing mail, leaving death threats to the Vice President, fundamentally acting the fool. A bunch of bullies let out of detention with rage and rebellion on their minds.

Let me be clear: each and every one of these terrorists should be hunted down by law enforcement and charged to the fullest extent of the law. They should then be prosecuted and the judges in each and every case should show or allow no mercy. These barbarians must never be allowed to storm the gates again.

Fine.

But that’s not the really interesting question here. The far-right has been producing assholes forever (one of the few things the ‘right’ is truly consistent at). What’s actually interesting is how these insurrectionists arrived at the conclusions they did. Which is to say; how did their ‘thinking’ bring them to this point.

2.

While it might be tempting for some on the left to see that last sentence as a joke, let’s remember we’re sitting at the adult table. These terrorists, being human, sharing our genetic code, are people - real, live, eating, shitting, fucking, anxious, sleeping, scared, afraid, terrified people - just like you and me. As much as it would be easier if we could see them as Uruk-hai instead of our brothers and sisters, sadly? That’s what they are. Family. Part of the Human Condition.

Though humans that are clearly very, very, very sick. My diagnosis? Mind Cancer. Let me explain, under the assumption my readers understand the difference between mind and brain. As such, I am not asserting that the terrorists are physically sick. From their pics and videos it’s clear many are - obesity, hypertension, anal retention - though that isn’t the point. It’s their mental programming, their minds, that have been infected. Infected with what?

Put simply? A disjointed ontological phenomenology obscured, obfuscated, and accelerated by persistently chaotic epistemological aberrations. Said plainly? Their ability to process reality has been impaired.

Why? Racial resentment, poor economic opportunities, an aversion to books and learning? Yes. All that. Plus? The internet, which has created a new Dark Ages.

Paradoxically, one built on light.

3.

Look. Self-interested demagogues intent on self-aggrandizement are nothing new. Nor are their ability to rally or rile a downtrodden populace. Sadly, demonizing the ‘other’ is also pretty par for the course in these scenarios. An old story, all told. What’s new this time is how it happens.

In a single second - count it out! One Mississippi - a beam, or photon of light moves 186,000 miles. Roughly seven times the circumference of the Earth. The new speed of hate. The internet, that modern marvel ushering in Humanity’s first truly post-scarcity resource, is built on light. Philosophers have for millennia wed knowledge with light. And now we all (well, those of us in the post-industrial world) carry a terminal connected to this internet in our pockets. A stunning marvel of human ingenuity. One would imagine that access to such a wellspring of knowledge and information would have a truly edifying affect on the Human Condition. Perhaps, in aggregate, or retrospect, it will. At the moment?

Yeah ...

At the moment it seems that the more access to information humans have the more they double down on tribal identities, wish fulfillment, instant gratification (read: porn), perceived slights, fantasy lands, Rick Astley videos, or the jibbering incoherent rantings of simple capitalists fomenting the fragile emotional states of low information individuals who feel they have no place in this world. This is a fundamentally devastating epistemological conundrum. Why? For centuries the barrier to the future was the amount of information, knowledge, you could access or process. Yet here and now? Here and now there might be too much access. Too much information. More so, the striking fact that our ability, as a species, writ large, to process or parse this information has not kept pace with the information at hand. A sad equation that inevitably leads to moments like 01/06/21.

4.

The Trump Terrorists of January 6th, 2021, weaponized the internet to facilitate their attempted coup. As did their ‘dear leader’ throughout his humiliating single term in office. In fact, it was the geometrical acceleration of connectivity and interconnectedness enabled via the web and its insanely capitalist platforms that allowed for their ‘movement’ to incubate and evolve. While it is true that neo-liberal policies advocating globalist economics and monetary policy are at the current root cause of most ills genuinely affecting rural, or poor, or uneducated MAGA-heads, it’s also true that apart from an Independent from Vermont no one in the political economy of the last couple decades gave much of a shit about these poor and dispossessed inheritors of old racial mythemes and toxic narratives of self-reliance. No one that is, other than their ‘dear leader’. Never mind he didn’t intend to ease their suffering in any material, or structural way. He talked about it. He tweeted about it. And then he gave them a little song and dance at the rallies. Breathtaking stuff.

However, it wasn’t just the performative act of playing ‘authoritarian’ that got them hot and bothered. No, it was at the same time the eternal need to belong to a group, the legitimate feeling of economic obsolescence, coupled with these new tools of information transmission. Tools that at once gave them powers unheralded and seemingly ensconced them in a protective shell, a perpetually larval manifestation of all their baser inclinations. A reactionary ‘safe space’ from which they could launch a thousand ships of intolerance and hate. What good is truth if you can’t weaponize it? What good are facts if you share them with everyone else?

And so we find ourselves revising Plato. There isn’t just one cave in which we are chained, kept from reality. There are multiple tunnels, alcoves, deeper caverns in which we might dwell. Furthermore, if lucky, there are different days, vistas, egresses in which we can escape from the confines of ignorance. Much like the lucky Mormons, it would seem the far-right believes there are plenty of planets in which ‘Truth’ can dwell. Never mind that multiplying ‘Truth’ in such a way doesn’t actually produce more truth.

In fact, it reduces ‘Truth’. Impoverishes it. Hollows it out.

Which is sad, really. For the major harm caused by these rebels isn’t to our democratic institutions, nor our mythological vision of our nature, nor that ever-loving economy - but to the very fabric that binds the social contract on which all the preceding rely.

That fabric being, specifically, a shared objective reality.

5.

How can we survive if we can’t agree on basic facts? Can a multi-racial, multi-cultural, representative democracy exist when a large percentage of the comprising citizens don’t believe in, or even acknowledge, that that’s actually what’s happening? Is White Supremacy so fundamentally a part of our nation’s DNA that the country can’t exist without it? If so, for those of us who vehemently oppose White Supremacy, the question might then be: is the country worth saving?

Most versions of Western Ethics indicate that violence is not the cure. Nor do I advocate such a position. At the same time I’m deeply troubled, because due their illness these actors are neither rational or coherent. Ergo, we can’t reason with them either. So what next?

To corral the revolutionary, if inchoate, spirit of these sick, fringe minds diseased as they are by hate, grievance, and digital oubliettes would any policy proposals be acceptable? Perhaps as fantastic an idea as the images from 01/06/21, what if the Federal Government decided to halt its obsequious sycophantry to corporate America and ‘elites’ and instead actually, seriously, emphatically reinvested in the heartland, in Main Street, in the working class? Wouldn’t it be ironic if a little more socialism was truly the cure these hatemongers require?

6.

Maybe we should step back and listen to the wisdom of George W. Bush.

Confronting what was at the time the most disheartening terror attack on the homeland, Bush made clear not all who could otherwise be lumped in with the terrorists were terrorists. In the same way that, yes, not all Trump voters are Trump Terrorists.

Even so. Bush made it clear you needed to pick a side.

With us - toward a diverse future in which the promise of the Founders is emboldened and expanded for all who live between our shores. Or against us - back to your stunted hovels and holes with all the other low information troglodytes you like to cosplay revolution with.

Choose.

It’s your call. But choose quickly, because history is watching, and only one path moves toward the future.

C. R. Stapor Longmont, CO 01/16/21

#January 6th#terrorism#domestic terrorism#the internet#social media#revolution#insurrection#01/06/21#low information#mind cancer#George W Bush#Trump#GOP#epistemology#white#essay#philosophers on tumblr

15 notes

·

View notes

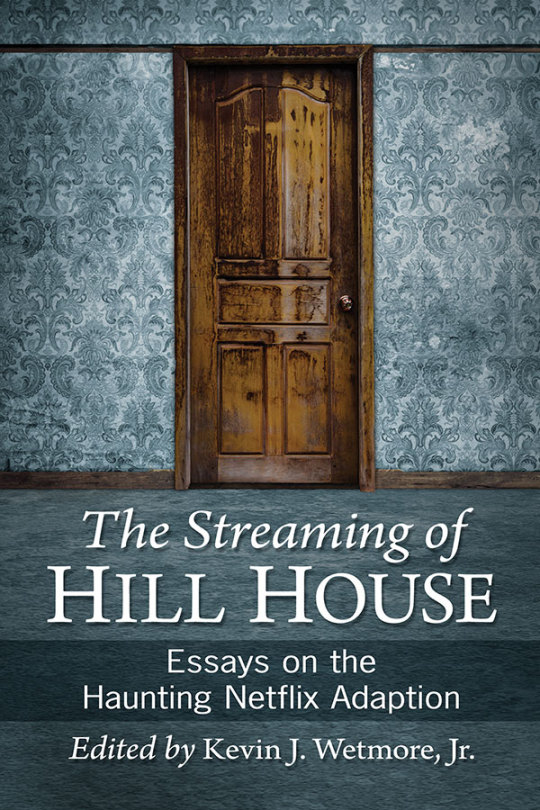

Photo

The Streaming of Hill House: Essays on the Haunting Netflix Adaption, edited by Kevin J. Wetmore Jr., McFarland, 2020. Cover image by Shutterstock, info: mcfarlandbooks.

Netflix’s The Haunting of Hill House has received both critical acclaim and heaps of contempt for its reimagining of Shirley Jackson’s seminal horror novel. Some found Mike Flanagan’s series inventive, respectful and terrifying. Others believed it denigrated and diminished its source material, with some even calling it a ‘betrayal’ of Jackson. Though the novel has produced a great deal of scholarship, this is the first critical collection to look at the television series. Featuring all new essays from noted scholars and award-winning horror authors, this collection goes beyond comparing the novel and the Netflix adaptation to look at the series through the lenses of gender, architecture, education, hauntology, addiction, and trauma studies including analysis of the show in the context of 9/11 and #Me Too. Specific essays compare the series with other texts, from Flanagan’s other films and other adaptations of Jackson’s novel, to the television series Supernatural, Toni Morrison’s Beloved and the 2018 film Hereditary. Together, this collection probes a terrifying television series about how scary reality can truly be, usually because of what it says about our lives in America today.

Contents: Acknowledgments Introduction—Holding Darkness Within: Welcome to Hill House – Kevin J. Wetmore, Jr. I. Jackson and Flanagan The Hunters and the Haunted: The Changing Role of Supernatural Investigation – Steve Marsden Hijacking Jackson: Adapting Mike Flanagan’s Oculus – Fernando Gabriel Pagnoni Berns II. The House It’s Coming from Inside the House: Houses as Bodies Without Organs – Matt Bernico A House Without Kindness: Hill House and the Phenomenology of Horrific Space – Zachary Sheldon III. The Trauma Some Things Can’t Be Told: Gothic Trauma – Jeanette A. Laredo Recovery from Trauma in Post–9/11 Horror/Terror of Mike Flanagan’s Oeuvre – Aaron K.H. Ho Education, Praxis and Healing – Elizabeth Laura Yomantas “A House Is Like a Body”: Processes of Grief and Trauma – Dana Jeanne Keller IV. The Haunted Mike Flanagan’s Mold-Centric The Haunting of Hill House – Dawn Keetley Where the Heart Is – Alex Link The Future Isn’t What It Used to Be: Hauntology, Grief and Lost Futures – Melissa A. Kaufler Ghosts of Future Past: Spatial and Temporal Intersections – Adam Daniel V. Gender and Queering Red Room, Red Womb: Phantom Feminism – Elsa M. Carruthers The Horrific Feminine: Terrifying Women – Camille S. Alexander Haunted Families, Queer Temporalities and the Horrors of Normativity – Emily E. Roach VI. Comparative Hauntings “Came Back Haunted”: International Horror Film Conventions – Thomas Britt The Beloved Haunting of Hill House: An Examination of Monstrous Motherhood – Rhonda Jackson Joseph The Madwoman in the Parlor: Motherhood and the Ghost of Mental Disorder in Hill House and Hereditary – Maria Giakaniki Family Remains: Family Bonds Against the Paranormal in The Haunting of Hill House and Supernatural – Melania Paszek “They Never Believe Me”: Discourses of Belief in Hill House and #Me Too – Brandon R. Grafius VII. Horror Makers on The Haunting of Hill House A Ghost Is a Wish Your Heart Makes – Christa Carmen The Screaming Meemies Resurrected – Angie Martin What Really Walks There? – Tim Waggoner Spirits and Mediums: Adapting Jackson – Kevin J. Wetmore, Jr. Gothic Storytelling – John Palisano About the Contributors Index of Terms

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why So Anxious?: Kierkegaard, Heidegger and Lacan on Anxiety

“That anxiety makes its appearance is the pivot upon which everything turns.” — Søren Kierkegaard | The Concept of Anxiety

Why has the number of anxiety disorders skyrocketed within the last 50 to 60 years? A good question. Based on prescription drug sales the Anxiety Disorders Association of America (ADAA) estimates that more than 40 million people suffer from anxiety disorders in this country. But what is the cause of our anxiety? Human beings have long been acquainted with this affect, but at no other point in history has it had such a strong hold on humanity at large. It seems as though there’s a systemic problem here. Could it be that late capitalism itself has a intrinsic element that provokes anxiety in us? There certainly seems to be a correlation between the two, since this era of capitalism began around 1945. Let us see if we can gain an idea of the cause of the social ubiquity of this phenomenon.

In pursuing the cause of anxiety and of its increase, we should look to the insights of the great thinkers of anxiety: Søren Kierkegaard, Martin Heidegger and Jacques Lacan. In my opinion, Lacan is the greatest thinker of anxiety since Heidegger. Lacan’s brilliance in relation to this affect is largely due to the fact that he was able to formulate a psychoanalytic mechanism for the assault of anxiety, that is, of the anxiety attack. Lacan’s most concentrated inquiry on this subject is found in his 1962–1963 seminar entitled Anxiety and it is this work that will be one of our main guides on the journey to the why of our anxiety. But first we must place ourselves in the proper context.

Kierkegaard on Anxiety

“Whoever has learned to be anxious in the right way has learned the ultimate.” — Søren Kierkegaard | The Concept of Anxiety

Kierkegaard was the first philosopher to examine anxiety in great depth. The Concept of Anxiety was, to my knowledge, the first book to ever focus exclusively on this phenomenon. In it Kierkegaard (writing under the pseudonym, Vigilius Haufniensis), formulated a concept of anxiety that would influence all of the thinkers who came after him that wrestled with existentialist motifs. For Kierkegaard, anxiety is without a determinate object, that is, it’s unintentional or unfocused. Of anxiety he wrote, “it is altogether different from fear and similar concepts that refer to something definite” (The Concept of Anxiety, 42). He went on to say, “anxiety is freedom’s actuality as the possibility of possibility” (The Concept of Anxiety, 42). What anxiety is about is human freedom, but this is certainly no object, that is, it is no-thing. Anxiety turns out to be the condition of freedom and this is precisely why Kierkegaard claimed that ambiguity resides at the core of this affect; as he put, “Anxiety is a sympathetic antipathy and an antipathetic sympathy” (The Concept of Anxiety, p. 42). In other words, anxiety is paradoxically something unpleasant from which we derive enjoyment and pleasure as well as something enjoyable that causes us pain and discomfort.

Heidegger would also claim that there’s something pleasurable in this discomforting mood: “Along with the sober anxiety which brings us face to face with our individualized potentiality-for-Being, there goes an unshakable joy in this possibility” (Being and Time, p. 358). Anxiety’s strange tension, i.e., pleasure in pain, also brings to mind the Lacanian concept of jouissance. But why is it that anxiety creates this tension? We find it enjoyable because it reveals to us our freedom, at the same time, we also find it unenjoyable precisely because it reveals to us our freedom. On the one hand, we love freedom for freedom’s sake, and on the other hand, the thought of being completely responsible for our actions and their unforeseen consequences is terrifying. Kierkegaard famously expressed this tension or “dizziness” in the following way:

“Anxiety may be compared with dizziness. He whose eye happens to look down into the yawning abyss becomes dizzy. But what is the reason for this? It is just as much in his own eye as in the abyss, for suppose he had not looked down. Hence anxiety is the dizziness of freedom, which emerges when the spirit wants to posit the synthesis and freedom looks down into its own possibility, laying hold of finiteness to support itself.” (The Concept of Anxiety, p. 61)

The image of a person standing at the edge of a skyscraper or a cliff really captures the temptation of anxiety. In this moment a person can surely be struck by the fear of falling, which is determinate and intentional in structure, but one can simultaneously be assailed by anxiety. In that moment of staring over the edge and down into the abyss, a frightful impulse suddenly rises up in the individual — the impulse to purposely throw oneself into the abyss. This experience provokes anxiety because we are confronted with the radical freedom we possess. Thus, for Kierkegaard, the point at which the individual becomes anxious (what Lacan referred to as the “anxiety-point”, that is, the mechanism through which the subject becomes anxious at a specific moment in time) is when he or she is confronted by the possibility of freedom. However, normally and usually, we simply make choices without having any anxiety, which is why Kierkegaard went on to qualify the relation between anxiety and freedom: “Anxiety is neither a category of necessity nor a category of freedom; it is entangled freedom, where freedom is not free in itself but entangled, not by necessity, but in itself” (The Concept of Anxiety, p. 49).

Kierkegaard centered his investigation of anxiety around what he believed to be the very first instance of the affect in human history, that is, the anxiety Adam experienced when God forbade him to eat of the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil: “But of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die” (Genesis 2:17). Kierkegaard argued that Adam, in his state of innocence, couldn’t have truly understood what “good”, “evil” or “die” actually meant. But what Adam was able to understand was that he had been forbidden to eat of the tree’s fruit, i.e., that he was free and that his freedom had just been restricted. But as any parent knows, prohibiting a child from doing x only creates the desire for x in the child. Lacan wrote, “But what does experience teach us here about anxiety in its relation to the object of desire, if not simply that prohibition is temptation?” (Anxiety, p. 54). According to Kierkegaard, it was anxiety that led Adam to sin.

“What passed by innocence as the nothing of anxiety has now entered into Adam, and here again it is a nothing — the anxious possibility of being able. He has no conception of what he is able to do; otherwise — and this is what usually happens — that which comes late, the difference between good and evil, would have to be presupposed. Only the possibility of being able is present as a higher form of ignorance, as a higher expression of anxiety, because in a higher sense it both is and is not, because in a higher sense he both loves it and flees from it. After the word of prohibition follows the word of judgment: “You shall certainly die.” Naturally, Adam does not know what it means to die. On the other hand, there is nothing to prevent him from having acquired a notion of the terrifying, for even animals can understand the mimic expression and movement in the voice of a speaker without understanding the word. If the prohibition is regarded as awakening the desire, the punishment must also be regarded as awakening the notion of the deterrent. This, however, will only confuse things. In this case, the terror is simply anxiety. Because Adam has not understood what was spoken, there is nothing but the ambiguity of anxiety. The infinite possibility of being able that was awakened by the prohibition now draws closer, because this possibility points to a possibility as its sequence. In this way, innocence is brought to its uttermost. In anxiety it is related to the forbidden and to the punishment. Innocence is not guilty, yet there is anxiety as though it were lost.” (The Concept of Anxiety, pp. 44–45)

However, it’s only fitting, given the Janus-faced nature of anxiety, Kierkegaard also believed that this affect, while being capable of bringing about our downfall into sin, can also lead us to salvation. This is why he held that “Whoever has learned to be anxious in the right way has learned the ultimate” (The Concept of Anxiety, p. 155). Anxiety awakens us to the responsibility we have for our actions, which, in turn, can awaken us to our guilt and sin before God. Anxiety, thus, precedes self-consciousness and self-examination. It is the condition for the pursuit of authentic selfhood and true identity, which, for Kierkegaard, always involves having a passionate faith in God through Christ. The words of Hölderlin resound: “But where danger is, grows the saving power also.”

Early Heidegger on Anxiety

“Anxiety is anxious about naked Dasein as something that has been thrown into uncanniness.” — Martin Heidegger | Being and Time

As we have seen, it was Kierkegaard who first argued that anxiety is objectless. This concept of anxiety obviously had a big influence on Heidegger’s own thinking in Being and Time. For Kierkegaard, the mechanism of anxiety or the “anxiety-point” is the presencing of one’s own radical freedom and possibility, or, in the specific case of Adam, the moment of the prohibition — this recognition is the trigger of anxiety. In what follows, I’ll discuss Heidegger’s relation to the anxiety-point. But, first, we need to understand the early Heidegger’s phenomenological description of anxiety.

“That in the face of which one has anxiety is Being-in-the-world as such. What is the difference phenomenally between that in the face of which anxiety is anxious and that in the face of which fear is afraid? That in the face of which one has anxiety is not an entity within-the-world. Thus it is essentially incapable of having an involvement. This threatening does not have the character of a definite detrimentality which reaches what is threatened, and which reaches it with definite regard to a special factical potentiality-for-Being. That in the face of which one is anxious is completely indefinite. Not only does this indefiniteness leave factically undecided which entity within-the-world is threatening us, but it also tells us that entities within-the-world are not ‘relevant’ at all. Nothing which is ready-to-hand or present-at-hand within the world functions as that in the face of which anxiety is anxious. Here the totality of involvements of the ready-to-hand and the present-at-hand discovered within-the-world, is, as such, of no consequence; it collapses into itself; the world has the character of completely lacking significance. In anxiety one does not encounter this thing or that thing which, as something threatening, must have an involvement.” (Being and Time, pp. 230–231)

So the “object” of anxiety, for the early Heidegger, is no object or entity at all, rather it is Being-in-the-world or existence (Existenz), i.e., Dasein’s mode of Being, and, remember, “The Being of entities ‘is’ not itself an entity” (Being and Time, p. 26). So, for Heidegger, anxiety is objectless, but, yet, it still has some-”thing” positive about it, which to say the world itself. Heidegger put it like this:

“Accordingly, when something threatening brings itself close, anxiety does not ‘see’ any definite ‘here’ or ‘yonder’ from which it comes. That in the face of which one has anxiety is characterized by the fact that what threatens is nowhere. Anxiety ‘does not know’ what that in the face of which it is anxious is. ‘Nowhere’, however, does not signify nothing: this is where any region lies, and there too lies any disclosedness of the world for essentially spatial Being-in. Therefore that which threatens cannot bring itself close from a definite direction within what is close by; it is already ‘there’, and yet nowhere; it is so close that it is oppressive and stifles one’s breath, and yet it is nowhere. In that in the face of which one has anxiety, the ‘It is nothing and nowhere’ becomes manifest. The obstinacy of the “nothing and nowhere within-the-world” means as a phenomenon that the world as such is that in the face of which one has anxiety. The utter insignificance which makes itself known in the “nothing and nowhere”, does not signify that the world is absent, but tells us that entities within-the-world are of so little importance in themselves that on the basis of this insignificance of what is within-the-world, the world in its worldhood is all that still obtrudes itself.” (Being and Time, p. 231)

“Being-in-the-world itself is that in the face of which anxiety is anxious.” (Being and Time, p. 232)

“That about which anxiety is anxious reveals itself as that in the face of which it is anxious — namely, Being-in-the-world.” (Being and Time, p. 233)

This amounts to saying that Dasein cares about nothing while overcome with anxiety. Nothing whatsoever matters to it because the world has momentarily ceased to be meaningful, i.e., ceased to signify. We must remember here the crucial distinction Heidegger made between the world and the ‘world’. The former being the totality of all referential totalities (systems of meanings, assignments, involvements, in-order-tos, toward-whichs and for-the-sake-of-whichs), whereas the latter would simply be the universe or the totality of objects (objects in the standard sense). Let’s filter this phenomenon of anxiety through Lacanian terms. This would mean that in anxiety the subject ceases to desire for a period of time, since the Symbolic order (reality) as such has ceased to have anything worth desiring in it. Of course, this would have to relate in some way to the subject’s relation to the objet a (the object-cause of desire). In anxiety something cuts off the desirability of the object at the core of the fundamental fantasy. If the formula of fantasy is $◊a, then in anxiety the lozenge itself gets barred. Desire presupposes a lack, but when desire itself is “castrated” we are faced with the uncanny lack of a lack. When meaning and significance are drained from the world all that is left for the senses is the full-on buzzing of beings in their alienating positivity (perhaps this is a glimpse of the Real?). It would seem as if desire itself gets castrated through the objet a vanishing momentarily from reality. Perhaps this is why anxiety can be such an ambivalent mood.

So, for the early Heidegger, we are anxious about Being-in-the-world (Symbolic order) as such, but what he has to say about anxiety isn’t exhausted in this one statement alone. He goes on to say that in anxiety Dasein essentially comes to see that it has a whole range of possibilities that das Man (the One, the They, or, in Lacanese, “the big Other”) conceals from it, and this realization enables Dasein to establish an authentic relation to itself. “The “They” does not permit us the courage for the anxiety in the face of death” (Being and Time, p. 298). So Heidegger says that anxiety is about both the world and death, but we can easily synthesize the two and say that anxiety is about Being-in-the-world-as-a-finitude. Authenticity (a relation to oneself and the world) always involves a resolute confrontation with death (Being-toward-death). One’s death is one’s “ownmost possibility” in Heidegger’s eyes, since one must face death absolutely alone, that is, no one can die your death for you or with you. In facing this possibility, Dasein begins to realize that it is finite, that its possibility of having possibilities has a indefinite expiration date, which means that it must stop wasting its time in gossip, inauthentic curiosity, superficiality, mindless consumerism, etc., and start existing for itself.

“Anxiety individualizes Dasein for its ownmost Being-in-the-world, which as something that understands, projects itself essentially upon possibilities.” (Being and Time, p. 232)

“Anxiety liberates him from possibilities which ‘count for nothing’, and lets him become free for those which are authentic.” (Being and Time, p. 395)

“Anxiety makes manifest in Dasein its Being towards its ownmost potentiality-for-Being — that is, its Being-free for the freedom of choosing itself and taking hold of itself.” (Being and Time, p. 232)

Here we can see Kierkegaard’s influence on Heidegger’s description of anxiety. For Heidegger, it “individualizes Dasein” and enables it to “become free” for its possibilities “which are authentic”. His concept of authenticity is basically an atheistic reconceptualization of Kierkegaard’s concept of Christian salvation (individualization via a faithful relation to God). Heidegger was also following in Kierkegaard’s footsteps in claiming anxiety reveals an individual’s freedom to his or her self, that is, the individual’s “Being-free for the freedom of choosing itself and taking hold of itself”.

The early Heidegger also perceived that anxiety has an essential connection to uncanniness, in fact, he seemed to identify the two, or, at the very least, seemed to make each one a side of the same coin. Whenever anxiety occurs we find that the world is suddenly alienated and unfamiliar. We’re abruptly no longer at home in the world — our tacit familiarity completely breaks down.

“Again everyday discourse and the everyday interpretation of Dasein furnish our most unbiased evidence that anxiety as a basic state-of-mind is disclosive in the manner we have shown. As we have said earlier, a state-of-mind makes manifest ‘how one is’. In anxiety one feels ‘uncanny’. Here the peculiar indefiniteness of that which Dasein finds itself alongside in anxiety, comes proximally to expression: the “nothing and nowhere”. But here “uncanniness” also means “not-being-at-home”. In our first indication of the phenomenal character of Dasein’s basic state and in our clarification of the existential meaning of “Being-in” as distinguished from the categorial signification of ‘insideness’, Being-in was defined as “residing alongside . . .”, “Being-familiar with . . .” This character of Being-in was then brought to view more concretely through the everyday publicness of the “they”, which brings tranquillized self-assurance — ‘Being-at-home’, with all its obviousness — into the average everydayness of Dasein. On the other hand, as Dasein falls, anxiety brings it back from its absorption in the ‘world’. Everyday familiarity collapses. Dasein has been individualized, but individualized as Being-in-the-world. Being-in enters into the existential ‘mode’ of the “not-at-home”. Nothing else is meant by our talk about ‘uncanniness’. (Being and Time, p. 233)

The last factor we must understand in Heidegger’s description of anxiety, which is of the utmost importance to grasp, is its relation to Dasein’s Being-towards-death. Heidegger wrote, “Anxiety arises out of Being-in-the-world as thrown Being-towards-death” (Being and Time, p. 395). Being-towards-death is an existential structure of Dasein’s existence, i.e., Being-in-the-world: “The ‘end’ of Being-in-the-world is death” (Being and Time, pp. 276–277). What is meant by “death” here isn’t the actual demise or physical death of a biological organism, but, rather, the existential death, or the possible death of Dasein. Existential death is something one “has” only as long as one is alive in the biological sense, so oddly enough, actual death is the negation of existential death — this latter form of death is a possibility, and a very special one at that. “Death is the possibility of the absolute impossibility of Dasein” (Being and Time, p. 294). Death, then, turns out to be “Dasein’s ownmost possibility” (Being and Time, p. 307).

“The full existential-ontological conception of death may now be defined as follows: death, as the end of Dasein, is Dasein’s ownmost possibility — non-relational, certain and as such indefinite, not to be outstripped. Death is, as Dasein’s end, in the Being of this entity towards its end.” (Being and Time, p. 303)

��We may now summarize our characterization of authentic Being-towards-death as we have projected it existentially: anticipation reveals to Dasein its lostness in the they-self, and brings it face to face with the possibility of being itself, primarily unsupported by concernful solicitude, but of being itself, rather, in an impassioned freedom towards death — a freedom which has been released from the Illusions of the “they”, and which is factical, certain of itself, and anxious.” (Being and Time, p. 311)

Heidegger went on to say, “No one can take the Other’s dying away from him” (Being and Time, p. 284), i.e., only I can die my death and no one can die my death for me. What he was attempting to reveal was that no one can cease to project his or her self onto the possibilities established and opened up by my facticity (the individuality of thrownness) except for me. If existence is essentially projection, and if projection is grounded by individual facticity, then the possibility of the complete cessation of taking a stand on my existence is a possibility that is mine alone — it is a possibility only I have, thus making it my ownmost possibility. This must be viewed from the perspective of facticity-as-a-whole and not merely aspects of facticity. People may have in common the factical conditions necessary for both of them to do or be x, for example, many people have aspects of their facticity which allow them to become professional basketball players. This possibility is not something most Daseins’ facticities allow them to be. However, while Daseins may have certain aspects of their facticities in common, no two Daseins have their facticities-as-a-whole in common. The unity of a facticity always belongs to one Dasein and only one Dasein. Facticity-as-a-whole is the key to understanding Heidegger’s statements regarding death. The possibility of taking a stand on my facticity-as-a-whole is a possibility only I have, therefore, the possibility of the impossibility of the possibility of taking a stand on my factiticity-as-a-whole is a possibility which belongs only to me. This statement could be modified for the sake of clarity in the following way: The possibility of taking a stand on my facticity-as-a-whole is a possibility only I have, therefore, the possibility of losing this possibility is a possibility which belongs only to me.

Death (the possibility of the impossibility of having anymore possibilities) can be said to individuate Dasein in the sense that the confrontation with it leads Dasein to choose for itself. A situation can be responded to in many ways but most of the time Dasein responds to it as One does, that is, as das Man does. Take, for example, the lives of Jesus, Buddha, etc. They disclosed and established new worlds by responding to situations in ways that broke with the One. Living in total submission to das Man can make life easier and very comfortable, but it’s also unfulfilling in the long run. Dasein usually lives in quiet desperation, always desiring to own itself and take control of its destiny. But the banality of everydayness and the pressure to conform put on it by das Man tends to suppress the desire for authenticity. An experience or event is needed to give Dasein a push in the right direction. Facing the possibility and inevitability of death head on can cause a massive disruption in the dictatorship of das Man, and it is anxiety that serves as the condition of this resolute confrontation with death. “Anxiety brings Dasein face to face with its ownmost Being-thrown and reveals the uncanniness of everyday familiar Being-in-the-world” (Being and Time, p. 393).

When Dasein, through the disclosure of anxiety, realizes that the annihilation of the possibility of being its self could fall upon it at any moment, and that it has not truly been exploring all of the possibilities it has, then it can take control of itself in a vibrantly authentic way. When Dasein realizes that its death is just that — its death, it realizes that it is not absolutely identical with the One, since the One will continue to exist after Dasein’s death. Anxiety’s unconcealment and presencing of the possibility of death has the unique power to disclose to Dasein that it has possibilities open to it that were not given to it by the One. And seeing how Dasein is its possibilities, it has come into a fuller relation with itself and its existence. It can then resolutely make decisions for itself, which is a way of being individuated and unchained from the generalities of the They-self.

We can come at this function of anxiety in another way. In this mood the world suddenly becomes meaningless. Dasein momentarily ceases to skillfully cope in the world, that is, abruptly experiences the equipment it uses to take a stand on its existence to be utterly insignificant, which means that anxiety brings about a breakdown of selfhood, since Dasein is what it does with equipment. But the good thing about this is that it can serve as an existentiell reboot so to speak. Dasein is forced to face itself in its ontological nakedness, and this can allow it to see just how inauthentically it has been living. Anxiety is the path to authentic selfhood.

Now let’s discuss if Heidegger posited an anxiety-point. It’s true that authentically facing death can make one anxious, but people are anxious all the time without standing in the shadow of death. It seems to me that while death is certainly a sufficient condition for the emergence of anxiety, it isn’t a necessary one. Heidegger (both early and later), never really posited an absolute anxiety-point. His descriptions of the phenomenon of anxiety are brilliant, but it’s true that they leave us wanting more, namely, the cause of the onset of anxiety in all cases. There’s something arbitrary about holding that we simply become anxious at certain times. However, he most likely avoided pursuing the anxiety-point due to his phenomenological description of moods or attunements (Stimmungs) in general. He said, “A mood assails us” (Being and Time, p. 176). By this he means moods arbitrarily fall upon us or take us over, which, from a purely phenomenological perspective, appears completely accurate. In some sense, we’re at the complete disposal of moods. Of course, we can attempt to put ourselves in new situations that change our moods, but nothing can absolutely guarantee that this will in fact change them. Sometimes it can actually intensify the mood. Anxiety overtakes us at moments that seem to have nothing in common. Just for clarification, the early Heidegger believed that anxiety is without an object while still being about some-”thing”, which turned out to be Dasein’s Being-in-the-world-towards-death as such. This means that, for the early Heidegger, anxiety is about a mode of Being, but not about Being itself. At this point, we are ready to consider what the later Heidegger thought of anxiety.

Later Heidegger on Anxiety

“Being held out into the nothing — as Dasein is — on the ground of concealed anxiety is its surpassing of beings as a whole. It is transcendence.” — Martin Heidegger | What Is Metaphysics?

Heidegger reexamined the phenomenon of anxiety in ‘What is Metaphysics?’. “Anxiety reveals the nothing” (Basic Writings, ‘What Is Metaphysics?’, p. 101). Simply put, the later Heidegger believed that anxiety is about the nothing: “Does such an attunement, in which man is brought before the nothing itself, occur in human existence? This can and does occur, although rarely enough and only for a moment, in the fundamental mood of anxiety” (Basic Writings, ‘What Is Metaphysics?’, p. 100). He goes on to say:

“That anxiety reveals the nothing man himself immediately demonstrates when anxiety has dissolved. In the lucid vision sustained by fresh remembrance we must say that that in the face of which and for which we were anxious was “properly” — nothing. Indeed: the nothing itself — as such — was there. With the fundamental mood of anxiety we have arrived at that occurrence in human existence is which the nothing is revealed and from which it must be interrogated.” (Basic Writings, ‘What Is Metaphysics?’, p. 101)

The nothing actually turns out to be Being — more accurately an aspect, function or activity that belongs to Being. He said, “The nothing does not remain the indeterminate opposite of beings but reveals itself as belonging to the Being of beings” (Basic Writings, ‘What Is Metaphysics?’, p. 108). It’s important to note that this “nothing” isn’t the nothing of Dasein’s existence that Heidegger discussed in Being and Time — this nothing is not the nothing at the core of Dasein, but, rather, something unto itself. The nothing is the nihiliation or the slipping away of beings into meaninglessness within the clearing, which persists in its presence as the nihilation of beings occurs. But when all that stands before Dasein is the clearing itself, then all that is present is the nothing of Being insofar as the presencing or there-ing of what is normally present and there (beings) is not a thing at all. This is the ontological difference: “The Being of entities ‘is’ not itself an entity” (Being and Time, p. 26). The two most important concepts for Heidegger throughout the entirety of his career were Being (Sein) and truth (aletheia/ἀλήϑεα). Being and truth are really the two essential structures of presencing as such, and the nothing of Being turns out to have an essential relation to truth:

“In the clear night of the nothing of anxiety the original openness of beings as such arises: that they are beings — and not nothing. But this “and not nothing” we add in our talk is not some kind of appended clarification. Rather, it makes possible in advance the revelation of beings in general. The essence of the originally nihilating nothing lies in this, that it brings Da-sein for the first time before beings as such.” (Basic Writings, ‘What Is Metaphysics?’, p. 103)

With this in mind, the later Heidegger reemphasized that the “object” of anxiety is indeterminate, i.e., not a being, and that meaninglessness or indifference always accompanies anxiety:

“The nothing reveals itself in anxiety — but not as a being. Just as little is it given as an object. Anxiety is no kind of grasping of the nothing. All the same, the nothing reveals itself in and through anxiety, although, to repeat, not in such a way that the nothing becomes manifest in our malaise quite apart from beings as a whole. Rather, we said that in anxiety the nothing is encountered at one with beings as a whole.” (Basic Writings, ‘What Is Metaphysics?’, p. 102)

“By this anxiety we do not mean the quite common anxiousness, ultimately reducible to fearfulness, which all too readily comes over us. Anxiety is basically different from fear. We become afraid in the face of this or that particular being that threatens us in this or that particular respect. Fear in the face of something is also in each case a fear for something in particular. Because fear possesses this trait of being “fear in the face of” and “fear for,” he who fears and is afraid is captive to the mood in which he finds himself. Striving to rescue himself from this particular thing, he becomes unsure of everything else and completely “loses his head.” Anxiety does not let such confusion arise. Much to the contrary, a peculiar calm pervades it. Anxiety is indeed anxiety in the face of . . ., but not in the face of this or that thing. Anxiety in the face of . . . is always anxiety for . . ., but not for this or that. The indeterminateness of that in the face of which and for which we become anxious is no mere lack of determination but rather the essential impossibility of determining it. In a familiar phrase this indeterminateness comes to the fore. In anxiety, we say, “one feels ill at ease.” What is “it” that makes “one” feel ill at ease? We cannot say what it is before which one feels ill at ease. As a whole it is so for one. All things and we ourselves sink into indifference. This, however, not in the sense of mere disappearance. Rather, in this very receding things turn toward us. The receding of beings as a whole that closes in on us in anxiety oppresses us. We can get no hold on things. In the slipping away of beings only this “no hold on things” comes over us and remains.” (Basic Writings, ‘What Is Metaphysics?’, pp. 100–101)

“In anxiety beings as a whole become superfluous. In what sense does this happen? Beings are not annihilated by anxiety, so that nothing is left. How could they be, when anxiety finds itself precisely in utter impotence with regard to beings as a whole? Rather, the nothing makes itself known with beings and in beings expressly as a slipping away of the whole.” (Basic Writings, ‘What Is Metaphysics?’, p. 102)

Heidegger goes on to give us a strikingly powerful description of the moment of anxiety and the breakdown of selfhood it causes; on other words, we lose the concrete content of ourselves — anxiety strips Dasein naked. Here Heidegger is basically saying that anxiety alienates us from our everyday identities that are grounded in the social positions or roles the world offers us to exist in. We, therefore, become uncanny to ourselves. In Lacanian terms, this would be both a breakdown in the ego with its secondary identifications in the Imaginary and in the chains of signifiers within the Symbolic the subject uses to represent itself.

We “hover” in anxiety. More precisely, anxiety leaves us hanging because it induces the slipping away of beings as a whole. This implies that we ourselves — we humans who are in being — in the midst of beings slip away from ourselves. At bottom therefore it is not as though “you” or “I” feel ill at ease; rather it is this way for some “one”. In the altogether unsettling experience of this hovering where there is nothing to hold onto, pure Da-sein is all that is still there. (Basic Writings, ‘What Is Metaphysics?’, p. 101)

Another strange feature of anxiety is that it lurks around us with a “repressed” or latent ubiquity: “The original anxiety in existence is usually repressed. Anxiety is there. It is only sleeping” (Basic Writings, ‘What Is Metaphysics?’, p. 106). The later Heidegger thought that Dasein is always in a perpetual state of anxiety, but on random occasions it explicitly makes itself known.

Original anxiety can awaken in existence at any moment. It needs no unusual event to rouse it. Its sway is as thoroughgoing as its possible occasionings are trivial. It is always ready, though it only seldom springs, and we are snatched away and left hanging. (Basic Writings, What Is Metaphysics?, p. 106)

To summarize, for the later Heidegger, anxiety is about the nothing, which is essentially Being itself (the difference between Being and beings). Now that we’ve clarified both Kierkegaard’s and Heidegger’s concepts of anxiety, we are ready to move on to a discussion of Lacan’s radically different concept of the affect.

Lacan on Anxiety

“The most striking manifestation of this object a, the signal that it is intervening, is anxiety.” — Jacques Lacan | Anxiety

Unlike Kierkegaard and Heidegger, Lacan believed anxiety has an object, or, as he put it “it is not without an object” (Anxiety, p. 89). But this object isn’t an ordinary kind of object — it’s the objet petit a (also referred to as “objet a”, “the Lacanian object”, “the lost object”, “the remainder” and simply “a”. This object is closely related to three of Lacan’s other concepts: 1. fantasy, 2. jouissance, 3. the Real. The concept of this object is arguably the most difficult to understand out of all of the Lacanian concepts, but it’s absolutely necessary to get at least a preliminary understanding of it in order to follow Lacan’s thinking on anxiety, since the two (objet a and anxiety) are essentially connected: “This year, the object a is taking centre stage in our topic. It has been set into the framework of a Seminar that I’ve titled Anxiety because it is essentially from this angle that it’s possible to speak about it, which means moreover that anxiety is the sole subjective translation of this object” (Anxiety, p. 100).

Lacan also said of the objet a that “it only steps in, it only functions, in correlation with anxiety” (Anxiety, p. 86). Throughout the course of this seminar, Lacan gives us different definitions of anxiety and it’s not immediately apparent that these are all compatible with each other. This seminar was given at the point in Lacan’s career when he was rethinking many of his essential concepts, so it has a very exploratory feel to it. One gets the impression that Lacan was thinking out loud while giving this series of lectures. But before we consider the different definitions, we must answer, to some degree, the question what is the Lacanian object? Žižek offers us a helpful analogy in the pursuit of this answer.

To mention the final example: the famous MacGuffin, the Hitchcockian object, the pure pretext whose sole role is to set the story in motion but which is in itself ‘nothing at all’ — the only significance of the MacGuffin lies in the fact that it has some significance for the characters — that it must seem to be of vital importance to them. The original anecdote is well known: two men are sitting in a train; one of them asks: ‘What’s that package up there in the luggage rack?’ ‘Oh, that’s a MacGuffin.’ ‘What’s a MacGuffin?’ ‘Well, it’s an apparatus for trapping lions in the Scottish Highlands.’ ‘But there are no lions in the Scottish Highlands.’ ‘Well, then, that’s not a MacGuffin.’ There is another version which is much more to the point: it is the same as the other, with the exception of the last answer: ‘Well, you see how efficient it is!’ — that’s a MacGuffin, a pure nothing which is none the less efficient. Needless to add, the MacGuffin is the purest case of what Lacan calls objet petit a: a pure void which functions as the object-cause of desire. (The Sublime Object of Ideology, pp. 183–184)

What we must first understand about the Lacanian object is that it’s not an object in the standard sense of the word. Put another way, this object is not the object of the metaphysical tradition — paradoxically, it is a “substantial” lack. This “object” is not a present-at-hand entity. It does not consist of atoms and it cannot be weighed, or measured, or experimented on, i.e., by its very nature it is beyond the reach of science. This virtual object also eludes the traditional phenomenologist, since one can only catch a glimpse of it at work while being situated within the psychoanalytic horizon. In other word’s, this object only makes itself known in the clinical setting, and this is precisely why it’s of the utmost importance to always connect Lacan’s concepts back to actual analysis. It was only because of the symbolic position Lacan occupied as an analyst that he was able to sense such an evasive “phenomenon” as the objet a.

Simply put, the objet petit a is the “object” that causes desire: “To set our target, I shall say that the object a — which is not to be situated in anything analogous to the intentionality of a noesis, which is not the intentionality of desire — is to be conceived as the cause of desire. To take up an earlier metaphor, the object lies behind desire” (Anxiety, p. 101). The objet a is the “object” we lost upon entering the Symbolic order, that is, the register of language, custom, social necessities, the Law, etc. Lacan says, “The objet a is something from which the subject, in order to constitute itself, has separated itself off as organ. This serves as a symbol of lack, that is to say, of the phallus, not as such, but in so far as it is lacking. It must, therefore, be an object that is, firstly, separable and, secondly, that has some relation to the lack” (The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, p. 101).

For Lacan, “symbolic castration” or “alienation” — basically socialization — involves the traumatic and liberatory loss of the maternal body, i.e., preoedipal jouissance. This blissful tension is the child’s whole world prior to the onset of the Oedipus complex. But this process eventually leads to the signifier (the Name-of-the-Father) “cutting” the child away from the full presence of its own jouissance and goading it to repress the signifier of the mother’s desire (the imaginary phallus), which brings about the inscription of the subject of the unconscious — of course, this is only how the Oedipus complex unfolds for “healthy” and “normal” neurotics. In the simplest terms, for most people what life is all about, unbeknownst to them, is their relation to objet a: “Effectively, everything turns around the subject’s relation to a” (Anxiety, p. 112). Yet it should be said that this object is not like an ordinary lost object. Sean Homer clarified this for us:

The objet a is not, therefore, an object we have lost, because then we would be able to find it and satisfy our desire. It is rather the constant sense we have, as subjects, that something is lacking or missing from our lives. We are always searching for fulfilment, for knowledge, for possessions, for love, and whenever we achieve these goals there is always something more we desire; we cannot quite pinpoint it but we know that it is there. This is one sense in which we can understand the Lacanian real as the void or abyss at the core of our being that we constantly try to fill out. The objet a is both the void, the gap, and whatever object momentarily comes to fill that gap in our symbolic reality. What is important to keep in mind here is that the objet a is not the object itself but the function of masking the lack. (Jacques Lacan, pp. 87–88)

What, at bottom, we desire, without consciously knowing it, is a sense of wholeness and completion that we once had with our mothers (or primary caregivers). The loss of the mother establishes a fundamental fantasy within the subject of the unconscious, and this fantasy will go on to shape all of the ego’s conscious pursuits. Of course, the ego isn’t aware that what it desires isn’t the cause of desire in and of itself. The structure of fantasy, at least for the average person, is $◊a, which means the barred (lacking) subject of the unconscious ($) desires (◊) the objet petit a (a). Bruce Fink explains all this well:

[M]an’s desire to be desired by the Other, exposes the Other’s desire as object a. The child would like to be the sole object of its mother’s affections, but her desire almost always goes beyond the child: there is something about her desire which escapes the child, which is beyond its control. A strict identity between the child’s desire and hers cannot be maintained; her desire’s independence from her child’s creates a rift between them, a gap in which her desire, unfathomable to the child, functions in a unique way. This approximate gloss on separation posits that a rift is induced in the hypothetical mother-child unity due to the very nature of desire and that this rift leads to the advent of object a. Object a can be understood here as the remainder produced when that hypothetical unity breaks down, as a last trace of that unity, a last reminder thereof. By cleaving to that rem(a)inder, the split subject, though expulsed from the Other, can sustain the illusion of wholeness; by clinging to object a, the subject is able to ignore his or her division. That is precisely what Lacan means by fantasy, and he formalizes it with the matheme $◊a, which is to be read: the divided subject in relation to object a. It is in the subject’s complex relation to object a (Lacan describes this relation as one of “envelopment-development-conjunction-disjunction” [Écrits, p. 280]) that he or she achieves a phantasmatic sense of wholeness, completeness, fulfillment, and well-being. When analysands recount fantasies to their analyst, they are informing the analyst about the way in which they want to be related to object a, in other words, the way they would like to be positioned with respect to the Other’s desire. Object a, as it enters into their fantasies, is an instrument or plaything with which subjects do as they like, manipulating it as it pleases them, orchestrating things in the fantasy scenario in such a way as to derive a maximum of excitement therefrom. (The Lacanian Subject: Between Language and Jouissance, pp. 59–60)

Fantasy isn’t merely a falsification of realty — it is our window or portal to reality. Žižek wrote,”With regard to the basic opposition between reality and imagination, fantasy is not simply on the side of imagination; fantasy is, rather, the little piece of imagination by which we gain access to reality — the frame that guarantees our access to reality, our ‘sense of reality’ (when our fundamental fantasy is shattered, we experience the ‘loss of reality’)” (The Žižek Reader, p. 122). To put this in Heideggerian terms, for Žižek, fantasy is the individual aspect of the clearing, fantasy is the mineness of disclosure as such. What makes the shared and social clearing mine is the fantasy through which I comport myself towards it. For Heidegger, authentic-Being-towards-death is that on the basis of which Dasein could be truly individuated, but Žižek thinks we’re always already individuated in relation to das Man (the big Other, the Symbolic Order) before we ever have a resolute confrontation with death, since fantasy is the individualizing existentiale of Dasein’s existence. Fantasy is thus the pre-authentic individuality of Dasein. With fantasy (individuality) and das Man (generality) as both existentialia, Dasein is ontologically a paradoxical being. However, and here’s the problem, our social identities, as we experience them everyday, are conditioned by the signifier (the differential nature of language), which means that to get what we want would be to lose it, since it would be the destruction of our selves. Thus, the “lost” object, this excess, this left-over of the Real, is a surplus of enjoyment (jouissance) we must remain separated from, even though it is us in strange sense. But what does it mean to speak of the objet petit a as a “surplus jouissance”? Once again we turn to Bruce Fink for clarification:

In Seminar XVI, Lacan equates object (a) with Marx’s concept of surplus value. As that which is most highly prized or valued by the subject, object (a) is related to the former gold standard, the value against which all other values (e.g., currencies, precious metals, gems, etc.) were measured. For the subject, it is that value he or she is seeking in all of his or her activities and relations. Surplus value corresponds in quantity to what, in capitalism, is called “interest” or “profit”: it is that which the capitalist skims off the top for him or herself, instead of paying it to the employees. (It also goes by the name of “reinvestment capital,” and by many other euphemisms as well.) It is, loosely speaking, the fruit of the employees’ labor. When, in legal documents written in American English, someone is said to have the right to the fruit or “usufruct” of a particular piece of property or sum of money held in trust, it means that that person has a right to the profit generated by it, though not necessarily to the property or money itself. In other words, it is a right, not of ownership, but rather of “enjoyment.” In everyday French, you could say that that person has la jouissance of said property or money. In the more precise terms of French finance, that would mean that he or she enjoys, not the land, buildings, or capital itself (la nue-pmpriété; literally, “naked property”), but merely its excess fruits, its product above and beyond that required to reimburse its upkeep, cultivation, and so on — in a word, its operating expenses. (Note that in French legal jargon, jouissance is more closely related to possession.) The employee never enjoys that surplus product: he or she “loses” it. The work process produces him or her as an “alienated” subject (S), simultaneously producing a loss, (a). The capitalist, as Other, enjoys that excess product, and thus the subject finds him or herself in the unenviable situation of working for the Other’s enjoyment, sacrificing him or herself for the Other’s jouissance — precisely what the neurotic most abhors! Like surplus value, this surplus jouissance may be viewed as circulating “outside” of the subject in the Other, It is a part of the libido that circulates hors corps.” (The Lacanian Subject: Between Language and Jouissance, p. 96)

But what is the essential relation between objet a and anxiety? Considering that Anxiety is about 340 pages long, Lacan obviously said a great many things about the affect that we cannot discuss here, but there are three essential aspects of anxiety Lacan pointed out that we must understand. First, anxiety is about the lack of a lack. Second, anxiety is a signal from the Real. Third, anxiety is about not knowing what the Other wants from you. We’ll discuss each one and, then, see if we can form a unified concept of the three of them.

Anxiety is about the lack of a lack — a presence of something that was and/or is supposed to be absent. Anxiety is about some overbearing presence that threatens to consume the subject. Lacan, controversially I might add, argues that the concept of separation anxiety is misguided to some degree. It’s not the absence of the mother that brings forth anxiety in the child, but, rather, her presence:

Don’t you know that it’s not longing for the maternal breast that provokes anxiety, but its imminence? What provokes anxiety is everything that announces to us, that lets us glimpse, that we’re going to be taken back up onto the lap. It is not, contrary to what is said, the rhythm of the mother’s alternating presence and absence. The proof of this is that the infant revels in repeating this game of presence and absence. The security of presence is the possibility of absence. The most anguishing thing for the infant is precisely the moment when the relationship upon which he’s established himself, of the lack that turns him into desire, is disrupted, and this relationship is most disrupted when there’s no possibility of any lack, when the mother is on his back all the while, and especially when she’s wiping his backside. (Anxiety, pp. 53–54)

To truly understand this passage, we must state that for Lacan there really isn’t one objet a, that is, we shouldn’t always speak of the Lacanian object. Strictly speaking, there are four types of objet a — there’s an objet a that corresponds to each of the drives, or, more accurately, around which each drive circles. Thus, in relation to the oral drive there is breast-as-objet-a; the anal drive circles around feces-as-objet-a; to the scopic drive corresponds gaze-as-objet-a; and to the invocatory drive there is voice-as-objet-a. Of course, these drive-objects are always susceptible to the substitutive (metaphoric/metonymic) function of desire and drive, e.g., money can take on and fulfill the function that shit had as the anal object. Lacan said in the above passage that “it’s not longing for the maternal breast that provokes anxiety, but its imminence”. What he’s getting at here is that it’s the presence of objet a, in this case breast-as-objet-a, that causes anxiety. But why should this be so? The reason why is because the presence and proximity of objet a is the presence of the desiring subject’s potential satisfaction and completion, which, in turn, is the annihilation of the subject ($) qua lack-of-being. This is precisely why Lacan held that “desire is a defense, a defense against going beyond a limit in jouissance” (Écrits, “The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire”, p. 699).

The subject only exists as a desiring lack, so the presence of objet a, the Real of jouissance, is the presence of imaginary-symbolic death. For fantasy to function, objet a must remain off its stage or out of its frame — that is, it must remain something absent that we’re unconsciously searching for (◊) in order to work. In Heideggerian terms, for the objet a to enter the scene of fantasy is for it to become unready-to-hand (remember that Heidegger argued in Being and Time that usually equipment only becomes present to us when it cease to work). For fantasy to function, objet a must withdraw like equipment: “The a, desire’s support in the fantasy, isn’t visible in what constitutes for man the image of his desire” (Anxiety, p. 35). On this theme, Lacan also wrote: “The base of the function of desire is, in a style and in a form that have to be specified each and every time, the pivotal object a insomuch as it stands, not only separated, but always eluded, somewhere other than where it sustains desire, and yet in a profound relation to it” (Anxiety, p. 252). Of course, it goes without saying that the objet a is not a piece of standard equipment, but that doesn’t negate the fact that it is like equipment in some respects.

So when Lacan claims that anxiety is a signal from the Real, we can now understand that what anxiety is warning us of is our imminent demise (Symbolic death). Here “signal” basically means what Peirce meant by “index”. An index or an indexical sign is a sign that “points” to its referent, e.g., smoke points to fire, a scab points to a past injury, and, for Lacan, anxiety points to objet a. Anxiety qua signal, then, turns out to be an ontological warning mechanism; it alerts us to the proximity of the lack of a lack that can shatter our identities.

Now that we see how the first two aspects of anxiety relate to each other, let’s consider the third one: anxiety is about not knowing what the Other wants from you. To illustrate this Lacan presented a very memorable image, though one that isn’t immediately clear.

For those who weren’t there, I’ll recall the fable, the apologue, the amusing image I briefly set out before you. Myself donning the animal mask with which the sorcerer in the Cave of the Three Brothers is covered, I pictured myself faced with another animal, a real one this time, taken to be gigantic for the sake of the story, a praying mantis. Since I didn’t which mask I was wearing, you can easily imagine that I had some reason not to feel reassured in the event that, by chance, this mask might have been just what it took to lead my partner into some error as to my identity. The whole thing was well underscored by the fact that, as I confessed, I couldn’t see my own image in the enigmatic mirror of the insect’s ocular globe. (Anxiety, p. 6)

What Lacan has in mind is the hypothetical experience of standing before a giant praying mantis while wearing a mantis mask without knowing what type it is. In other words, you don’t know if the mask you’re wearing is the mask of a female mantis, a male mantis or even a baby mantis. In this moment, you would be completely anxious about what the giant insect desires of you, since you have no way to unconceal the specific nature of its desire. Lacan said that this image of being present in the presence of the giant praying mantis “bore a relation to the desire of the Other” (Anxiety, p. 22). What, then, makes us anxious is not knowing what the Other wants from us (Che vuoi?). But why should this be? It most certainly can be a frightening thing to find yourself as the object of the Other’s desire, or to be connected in some way to one of the Other’s objet a(s) as the organ of surplus jouissance. “The nightmare’s anxiety is felt, properly speaking, as that of the Other’s jouissance” (Anxiety, p. 61). But how can we reconcile this aspect of anxiety with the other two? Desire (◊) is one of three structures of fantasy, therefore, no desire = no fantasy. Desire arises from the cut of the signifier — the “scalpel” of the big Other. Lacan said, “Desire is always what is inscribed as a repercussion of the articulation of language at the level of the Other” (My Teaching, p.38).