#the peace of Amiens

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

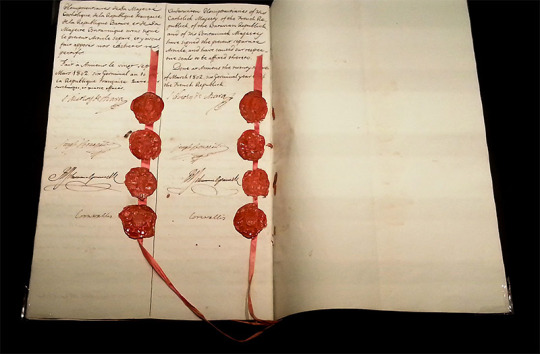

I like that there are two dudes having a moment in the background during the signing of the treaty of Amiens.

(Also, it’s not clear if the dude in the front left is Joseph or Napoleon)

Painting: The Peace of Amiens by Jules-Claude Ziegler

#Jules-Claude Ziegler#Ziegler#napoleon#napoleonic era#napoleonic#napoleon bonaparte#first french empire#joseph bonaparte#Joseph#Napoleon’s brothers#19th century#french empire#the peace of Amiens#Amiens#treaty of Amiens#peace of Amiens#history#french revolution#coalition wars#napoleonic wars#Cornwallis#queer#queer history#gay history

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

rambling here (& a little drunk) but it's so interesting coming to les mis from a preexisting maritime/age of sail interest background because like the whole historical situation (well. wrt toulon at least) it's discussing is like. it's very much a side of things you don't think about so much I guess when you're focused on life on board the ships themselves & particularly ships at sea. which -- like tbc my knowledge of this stuff is mostly to do with the royal navy during the same period, which can be very different re: how it functioned, so I don't necessarily know much about the french navy or how obvious this stuff would be if I was reading books about the french navy -- but just the whole existence of the bagne & the prisoners being the ones to help with the ships while they're in port (amongst other things) really makes one think about like idk. how casually you might get someone on the ship referring to 'putting in for repairs' or something in a way you wouldn't think twice about what that might imply. meanwhile then you read this & read the historical background & there's a whole different angle that's absolutely full of horrors. idk idk like I keep thinking about how in post captain (aubrey-maturin series, so written well after les mis & probably deliberately conscious of it while doing this) when they go into the harbor in toulon to meet with christy-palliere during the peace of amiens & there's like half a sentence mention of the convicts on the far side of the harbor unloading stuff from the ships before they go on with their lives (& this is 1802, jvj would literally be over there right then), and it's just background description. and how like every battle you read about, in fiction or non fiction, every time they talk about french ships taking damage or needing supplies etc etc it that it's often toulon (or similar) they'd be limping back to. it's just such a crazy shift in perspective & new consideration of some of the actual sources of this historical labor & how damaging it was beyond what's on the actual ships

#^ sorry for the unedited block of text. I'm just pondering.#like tbc I'm well aware of the general abuses of historical navies & also of proson systems but for some reason this specific#aspect has just never really occurred to me or so e to my consideration before reading this book#in terms of it as like a long term institutional thing#thoughts#like I'm used to thinking about abuses On the ships re: hierarchy class impressment violence etc but this is whole other aspect

113 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ok how about Jack/Stephen (or Jack&Stephen) with the prompt "some part of me must have died the first time that you called me baby." AND maybe like play with the later line "some part of me must have died the final time that you called me baby." Like the first time Stephen refers to Jack so lovingly is the last time??Maybe like one of them is dying or something? Angst?? IDK HOW WRITING PROMPT REQUESTS GO!? OK THANK YOU BYE

Yeah - you got it! I write for Dragon Age too, and they have a thing every friday called Dragon Age Drunk Writing Circle where everyone sends each other asks with prompts and pairings; the idea is that you write them that night and post immediately, no editing! It's super fun and I miss doing it, but I'm not super feeling the DA writing bug ATM, and also work friday nights, so it's not feasible.

But I missed prompt writing, so I'm seeking it out on my own!

And ohhhh this is some delicious angst thank you - I will probably change out "baby" for a more period-accurate endearment but lets see what I can come up with...

[Two excerpts from the diaries of Dr Stephen E Maturin, Esq.: the first dated 29 June 1803 - just after the end of the Peace of Amiens - and the second 23 October, 1847 - the day of Admiral Jno. Aubrey's death. These fragments were first published by his (and Admiral Jno. Aubrey's) 5th great-granddaughter, Diana Niamh Lambert, in a collection exploring Dr Maturin's complex relationship with the Aubreys; there are provided here in both their original encoded Catalan and an English translation.]

[the writing on these pages is hasty and sprawling, but neater than anything dated after 1805]

I hardly know how to write - I am aflutter like a girl. My hand is miserable - it sprawls across the page with no respect for the cost of bound pages - but I must sort my thoughts. JA - he is not yet well, of course, the creature; he will not be for many weeks still, so weak and exhausted is he. But he recovers as well as I could hope, though he is occasionally still delirious for some time after waking. I had thought his endearments to me a symptom of his delirium - perhaps he thought me to be SW, the dear girl, or another of his acquaintance, and so he clung to my hand and called me beloved out of his confusion. And yet today, in his waking dream, he called out "Stephen, my soul and love," when he could not find me. I felt as if I should die to hear it - I had not considered even the idea of my affections returned. I know I am letting my heart run away with my head (a state more familiar these last months than since before the failed Uprising) but- If he should- Will I ask him, when he is well? His friendship means so very much to me that I fear risking it on such a chance - I am ever a coward in affairs of the heart, as shown by MO'C and DV both before now - and yet my breast feels so light at the possibility that I cannot imagine staying silent.

[the writing on these pages show evidence of severe arthritis and tremours, as well as what appears to be damage from tears]

He is gone. Jack Aubrey has breathed his last - SA and the children were with him at the end, as was I; even SP was able to make the trip, having relocated to Ireland with Jack's decline. SP and I sit with him now - there are no Church of England rites to be performed, and SA was kind enough to allow us our heathenish, Papist rituals to-night. I have feared this day for so long - an abstract fear near as long as we have known each other (for the atrocities of war are blindingly apparent to a surgeon), and a far more real horror since the death of my beloved Diana. The Dear knows I did not cope well with her loss; I was not a good father to BA for many years after - for she is so like her mother as to have hurt to look at - and I thank Mary every day for CO and PC and SA for caring for my little bird when I could not. Yet I find age has tempered the pain, though I grieve him more fully than I thought possible. He has not been entirely himself these last two or three years together, and I find myself thankful he regained clarity in his last weeks; we could all say our goodbyes in peace with the man we love. His spirits were not unnaturally high nor miserable - he remembered his grandchildren, even our dear little girl - B and G's darling daughter - and doted upon her most sweetly. [there are a few lines here, blurred with water-damage and scratched over too many times to be made out] Oh, Jack- SA and I will not be long behind you, I believe. She is stronger than I, though, and I fear she will soon be alone; my hands - never truly recovered from the French - tremble and ache so fierce I have neglected my writings for many years, my breath rattles in my lungs. I am dying, my love, my loves; I will see you soon, if the Lord has any mercy in his heart for me. I think, perhaps, I have been dying since last night, joy. SA was so kind to give us an hour alone. You called me your soul, your dearest soul, Jack - you called me your love - and I knew you should never do so again; a part of me died to hear you name me such and know it was the final time. Farewell, my captain; give Diana my truest love, and tell her I shall see you both again in less time than it seems.

#stephen maturin#aubreyad#aubrey maturin#jack aubrey#thiefbird writes#i'll be getting to more prompts asap! this one just grabbed me by the fucking horns lmao

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Augustus Foster To Lady Elizabeth Foster. Paris, April 19, 1802.

I saw Massena and M‘Donald. The last resembles Lord Morpeth, I think; he is fair faced and gentlemanlike-looking. Massena is black-faced and seems a scoundrel. Buonaparte I still admire. His face was perfectly grave during the whole ceremony. After it was over he pleased everybody by his condescension in speaking to them. What was rather mockery, I think—I did not see it myself—but Camille Jourdan told me that he crossed himself several times as well as Cambaceres. That was trop fort for one once a professed Turc. Madame Buonaparte dresses very lightly; seems to have been pretty; she, with Madame Joseph, I think her daughter, and Madame Murat, her sister-in-law, and Louis Buonaparte with several ladies, was placed in a gallery a little above the altar on the left; she only came with two horses to her carriage.

Frederick Foster To (his son) Augustus Foster. Marseilles, Dec. 27, 1814.

My dearest Augustus. . . . We have seen Massena. He is, I believe, stingy, but very civil, and very interesting to see. Bonaparte on embarking for Elba sent him his amities, c'est un brave homme je l'aime fort—but Massena says he, Bonaparte, loves nobody; that once when he was ill, Bonaparte never took the least notice of him, never even sent to enquire, and that at another time, when he was also unwell, and that Bonaparte had need of his services, he used to come and see him three or four times a day. He thinks he was a man de grandes conceptions, particularly when things went on well, but that in adverse fortune he failed....yet Massena seemed to have a kind of liking for him; said that it was him who had named him I'enfant de la Victoire, and pointing to his great coat said he was happier when he bought that, it was at Vienna...Massena is much broken and altered from what I remember him at the peace of Amiens. He and Wellington met at Paris, and after a stare Massena said, "Milord, vous m’avez fait bien penser.” "Et vous, monsieur le Maréchal, vous m’avez souvent empêché de dormir." [Milord, you really made me think. And you, M. le Marechal, you often made me lose sleep.]

The two duchesses, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, Elizabeth, Duchess of Devonshire, 1898

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Geoff Hunt's cover painting for Post Captain (1972), Patrick O'Brian's second novel in his Aubrey-Maturin series.

The cover depicts Jack Aubrey of His Majesty's Royal Navy, newly promoted to captain, aboard the HMS Lively, a temporary command he is given, as it races to intercept a Spanish squadron.

This novel is a bit different from most of the series, as the two main characters - Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin - spend a great deal of time on land instead of at sea. This is due to the Peace of Amiens, a temporary lull in the Napoleonic Wars that began in March, 1802 and lasted until May, 1803. It was the only period of relative peace in Europe between 1793 and 1814, when Napoleon was finally defeated.

During the course of the story we get to learn a great deal more about Jack and Stephen, as they get to learn more about each other. Despite some difficulties along the way, the bond between the two is strengthened immeasurably, as they become more akin to brothers than friends.

There is also a great deal of comedy sprinkled throughout the tale, a delightful trait of O'Brian's novels. Perhaps most memorable is their escape from France (once hostilities have broken out again) disguised as an itinerant entertainer and his trained bear.

#Post Captain#Patrick O'Brian#Aubrey-Maturin series#Geoff Hunt#Napoleonic wars#sailing ships#historical fiction

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

An endorsement of vaccines from 1804

In a letter to his mother the British diplomat George Jackson writes:

"4[th of July 1804] - By-the-by, I must not omit to tell you that I have been vaccinated. I hope you are become a convert to that operation, which saves so many lives, and will, in time, make the small-pox as fabulous as the leprosy, or any other disorder no longer known. It seems to be more in favour here [in Berlin] than in England. Certainly it is the most signal blessing which has for many years been bestowed upon humanity, and may perhaps be put in the scale against many of the evils we suffer."

Preach, George, preach!

From: "The Diaries and Letters of Sir George Jackson, K.C.H., From the Peace of Amiens to the Battle of Talavera", Volume 1, 1872, p. 214

#apparently the WHO declared small-pox eradicated in 1980#probably a bit longer than jackson had anticipated but still#sir george jackson#medical history#vaccination

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

One of the things about the Horatio Hornblower series is that it keeps pointing out that while Hornblower can raise through the ranks of the English navy on his own merit, it is very difficult to do so without friends in high places whereas those with peerage and connections can do so far easier. In his youth he pushed himself to take risks he wouldn't have otherwise in order to distinguish himself, and even then his promotion to commander was delayed by the British navy due to England and France signing the Peace of Amiens when he was on the way back home to confirm his appointment (he impressed the lord of the admiralty with his analytical skills playing whisk before conflict broke out again who confirmed his appointment. Hornblower, meanwhile, was reduced to poverty because he had to pay back his additional pay for the unconfirmed promotion while also being on half-pay due to the peace).

Think about that, then look at Shez's C support with Hubert.

I think that's the discussion we had some time ago (I think?) about the Doro mention in this support ?

Doro sacrificed a lot and worked very hard (and "caught the eyes" of many nobles who asked her to "sing" for them) to become the famous songstress she is when the game starts.

And yet, while Shez still calls her a commoner, Hubert corrects them, Doro isn't a mere commoner like Joe the carpenter or Karin the miller or Shez the mercenary, Doro became an important commoner. Just like noblity has minor and not minor nobles, commoners come in different "importance", you have Doro and... Leonie.

Even still, Manu, in her support with Flayn, reveals that hard work and stuff isn't sufficient to become a diva - at one point, aspiring divas have to "catch the eyes" of a noble, and raise through ranks like this.

So yeah, without "friends" in high places or positions, a random commoner, even if they are the best at doing what they do, will never raise through the ranks and transcend their initial condition of beta commoner.

Wait...

The more I think about it, the more I realise that some supports unvailable in CF, especially with Nabateans, blow massive holes in Supreme Leader's rhetoric.

#fantasyinvader#the mittelfrank opera is really interesting as#an anti muhritocracy example that is never touched upon#Doro and Manu might have worked hard to have divine and/or mystical voices#if they don't sleep around they will never become divas#they need to stay close to nobles to become divas even if they are the best at singing like#is that why Doro only talks/supports nobles?#no ending ever imply mittelfrank is changed after the war in CF#and we know thanks to the jp version what the non divas singers are supposed to do during war times for the imperial army...

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey, re: one of your latest posts, is there any merit whatsoever to the rumours that napoleon had an affair with his stepdaughter? and if not, why did they arise?

[Muttering under her breath - I never should have opened this can of worms… why can I never keep my mouth shut...]

Well, hi and thank you for the question. 😁

Okay, first of all: No, I do not think there is a single serious historian today who actually believes the rumours about Napoleon being the father of Hortense‘s oldest son. And while I don‘t like Napoleon much myself I also don‘t believe it. Napoleon‘s early letters, particularly from the time of the Consulate, to Hortense are a fun read and show a (step-)father talking to his daughter, and that‘s just that. The child was born ten months after Hortense‘s marriage, so there is no reason to even assume the father was anybody but Hortense‘s husband.

Does it rule out the possibility? No, of course not.

According to Hortense‘s memoirs, the first rumours of this kind came from British newspapers. Which is quite possible, as the Peace of Amiens was shaky from the beginning and some parties were actively working to break it up. There were nasty rumours and disparaging pamphlets galore. Also according to Hortense, Napoleon was secretely quite content about this, as he suspected this nephew might be more easily accepted as Napoleon‘s successor if people supposed Napoleon to be the father. Later, it‘s the pamphlets by Lewis Goldsmith, an Anglo-French publicist working for both sides, who repeated and invented the most disgusting slander (including incestuous relationships).

In truth, there are some passages from Laure Junot‘s memoirs (for what those are worth, of course!), relating to the time of the Consulate, describing how Napoleon entered Laure's bedroom in Malmaison at nights and how he got really furious when she locked her door, to the point she insisted Junot spend the night with her at Malmaison. This would point to Napoleon really taking some liberties with the young ladies of his entourage. That Napoleon in general was not the most virtuous of husbands is a well-known fact, even if we do not have to go as far as Bausset, who years later in a fit would claim to Marie Louise that Napoleon »had had every lady of her court for a shawl« (except for Madame de Montebello, for whom it took three).

Hortense, from 1808 on and with a short interruption in early 1810 stayed, far away from her husband, in Paris at court and at the least lived a life in a dubious position for a married woman. She had one lover she admits to in her memoirs (Flahaut), but all her life she loved to be surrounded by a circle of admirers, so she was rumoured to have many more. The birth of future Napoleon III gave reason to much gossip in Paris and was the reason why Louis broke with Hortense completely. Apparently, everybody and their grandmom was convinced Louis was not the father, despite pretending the opposite. At the very least, Hortense was the only one among the not-altogether-virtuous Imperial ladies who managed to get herself so deeply into trouble that she had to secretely escape to Switzerland in order to give birth to a child. But even that cannot have been all that much of a secret later, considering that the Duc de Morny was openly talked about as being »né Hortense«.

Many memoirs of the time mention or hint at the rumours about Napoleon's alleged affair with Hortense, and the vast majority declare them as false. The only important memoirs that I know of that explicitely confirm them are Fouché‘s. But those are, while not entirely apocryphal, of dubious authenticity, as they were published after his death under the Bourbon Restauration, put together from Fouché‘s papers. The Bourbon Restauration again produced an abundance of pamphlets and of course jumped at the occasion to repeat these allegations over and over again.

To sum up: There were plenty of rumours already during the Empire, and neither Napoleon‘s nor Hortense‘s personal way of life did much to disencourage them. There is, however, also not a single piece of evidence for them to be true. I'm not sure if this really answers your question, and I wish there was a way to disprove them entirely, but this is the best answer I can give. If anybody has additional information, I'd love to hear it!

As to Napoleon, he on Saint Helena dismissed the idea of an affair with his stepdaughter at one point as stupid because »everybody knows Hortense is ugly«.

Well, thank you, I guess.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINT OF THE DAY (November 11)

On November 11, the Catholic Church honors St. Martin of Tours, who left his post in the Roman army to become a “soldier of Christ” as a monk and later bishop.

Martin was born around the year 316 in modern-day Hungary. His family left that region for Italy when his father, a military official of the Roman Empire, had to transfer there.

Martin's parents were pagans, but he felt an attraction to the Catholic faith, which had become legal throughout the empire in 313.

He received religious instruction at age 10 and even considered becoming a hermit in the desert.

Circumstances, however, forced him to join the Roman army at age 15, when he had not even received baptism.

Martin strove to live a humble and upright life in the military, giving away much of his pay to the poor.

His generosity led to a life-changing incident when he encountered a man freezing without warm clothing near a gate at the city of Amiens in Gaul.

As his fellow soldiers passed by the man, Martin stopped and cut his own cloak into two halves with his sword, giving one half to the freezing beggar.

That night, the unbaptized soldier saw Christ in a dream, wearing the half-cloak he had given to the poor man.

Jesus declared: “Martin, a catechumen, has clothed me with this garment.”

Martin knew that the time for him to join the Church had arrived. He remained in the army for two years after his baptism but desired to give his life to God more fully that the profession would allow.

When he finally asked for permission to leave the Roman army during an invasion by the Germans, Martin was accused of cowardice.

He responded by offering to stand before the enemy forces unarmed.

“In the name of the Lord Jesus, and protected not by a helmet and buckler, but by the sign of the cross, I will thrust myself into the thickest squadrons of the enemy without fear.”

But this display of faith became unnecessary when the Germans sought peace instead, and Martin received his discharge.

After living as a Catholic for some time, Martin traveled to meet Bishop Hilary of Poitiers, a skilled theologian and later canonized saint.

Martin's dedication to the faith impressed the bishop, who asked the former soldier to return to his diocese after he had undertaken a journey back to Hungary to visit his parents.

While there, Martin persuaded his mother, though not his father, to join the Church.

In the meantime, however, Hilary had provoked the anger of the Arians, a group that denied Jesus was God.

This resulted in the bishop's banishment so that Martin could not return to his diocese as intended.

Instead, Martin spent some time living a life of severe asceticism, which almost resulted in his death.

The two met up again in 360, when Hilary's banishment from Poitiers ended.

After their reunion, Hilary granted Martin a piece of land to build what may have been the first monastery in the region of Gaul.

During the resulting decade as a monk, Martin became renowned for raising two people from the dead through his prayers.

This evidence of his holiness led to his appointment as the third Bishop of Tours in the middle of present-day France.

Martin had not wanted to become a bishop and had actually been tricked into leaving his monastery in the first place by those who wanted him the lead the local church.

Once appointed, he continued to live as a monk, dressing plainly and owning no personal possessions.

In this same spirit of sacrifice, he traveled throughout his diocese, from which he is said to have driven out pagan practices.

Both the Church and the Roman Empire passed through a time of upheaval during Martin's time as bishop.

Priscillianism, a heresy involving salvation through a system of secret knowledge, caused such serious problems in Spain and Gaul that civil authorities sentenced the heretics to death.

But Martin, along with the Pope and St. Ambrose of Milan, opposed this death sentence for the Priscillianists.

Even in old age, Martin continued to live an austere life focused on the care of souls.

His disciple and biographer, St. Sulpicius Severus, noted that the bishop helped all people with their moral, intellectual and spiritual problems.

He also helped many laypersons discover their calling to the consecrated life of poverty, chastity and obedience.

Martin foresaw his own death and told his disciples of it.

However, when his last illness came upon him during a pastoral journey, the bishop felt uncertain about leaving his people.

“Lord, if I am still necessary to thy people, I refuse no labour. Thy holy will be done,” he prayed.

He developed a fever but did not sleep, passing his last several nights in the presence of God in prayer.

“Allow me, my brethren, to look rather towards heaven than upon the earth, that my soul may be directed to take its flight to the Lord to whom it is going,” he told his followers, shortly before he died on 8 November 397.

St. Martin of Tours has historically been among the most beloved saints in the history of Europe.

In a 2007 Angelus address, Pope Benedict XVI expressed his hope “that all Christians may be like St Martin, generous witnesses of the Gospel of love and tireless builders of jointly responsible sharing.”

He is the patron saint of soldiers, beggars, and France.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 July 2023

Oh It’s A Lovely War

Amiens 3 July 2023

By the end of 1917, time was running out for Germany. Russia may have sued for peace, but the United States had entered the war, and Generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff, now effectively dictators of Germany, knew that numbers would soon inexorably favour the Allies on the Western Front. Ludendorff needed one last masterstroke - a decisive battle to destroy the French and British before the Americans could arrive.

The great offensive - Operation Michael - was aimed at Gough’s Fifth Army, still exhausted from the hell of Passchendaele. On the 21st of March 1918, after a sudden and violent artillery and gas attack, German stormtroopers smashed into the Fifth Army, and although their losses were massive, they attacked with such force that Fifth Army gave way. For a moment, as Haig scrambled to plug the gaps in his line and Fifth Army’s command and control disintergrated, it looked Germany might actually win the war.

It is here, in the popular narrative, that Australia stops them at Villers-Bretonnaux. In reality, there were two battles here that sometimes get conflated into one. At First Villers-Bretonnaux, British and Australian troops managed to halt the German offensive just short of the town. This wasn’t the only place where the BEF had managed to blunt Micheal - Arras held, and while the Germans had taken Albert, they had advanced little further. It was however the final nail in the coffin for any German effort to take the vital railway hub at Amiens. The Germans made a second attempt on the 24th of April and briefly captured the town, but were repulsed by a counterattack the following day. The popular idea here is Chunuk Bair in reverse - the British ‘lost’ the town and the Australians ‘retook’ it. In fact it wasn’t so simple - two Australian and one British brigade took part in the counterattack, alongside French Moroccan troops to the south.

It was a significant victory, but it didn’t stop the Germans completely. Ludendorff launched more offensives throughout the spring (including towards Hazebrouck, which was defended by First Australian Division and several British divisions.) Against all of them, the Allies held, although the fighting was hard and the cost was appalling. The cracks in the German strategy began to show - more and more American troops were being moved in front of them, and more and more of their best men were being killed. The end of the Spring Offensives came at the Second Battle of the Marne, in which chiefly French but also British, Italian and (for the first time in significant numbers) American troops decisively stopped Ludendorff’s last throw of the dice. No one country can claim credit for this - stopping the Spring Offensives required the full effort of every major participant in the Allied order of battle. It was a team effort.

Some people don’t seem to understand that, and sadly they’re often the people in charge of commemorating the war. Which brings us back to Villers-Bretonnuex.

Our first stop today was Adelaide Cemetery, just outside the town. If the name seems familiar, it’s because I’ve mentioned it before, although it seems like years ago now; this was where the Unknown Soldier was exhumed. Today, his former spot is marked with a special inscription, but otherwise the plot has the same shape of tombstone as everybody else. One might lament that he’s been removed from a peaceful plot in France to the hustle and bustle of Canberra - if, of course, they didn’t know that Adelaide Cemetery is sandwiched between a major road and a railway line, so he probably would find the AWM more peaceful.

We went from there to the Australian Memorial outside Villers-Bretonneux. John Monash Centre aside - and I swear, we’ll get to that soon - this is beautiful site, nestled amongst rolling hills and endless fields of wheat. To get to the main monument, you pass between two cemetery plots, as if the graves are lined up on parade - these are largely Australians, but there’s also a lot of Canadian and British soldiers who lost their lives in the battles around Amiens in mid-1918. You pass through two flag poles - French and Australian - and reach the main facade, in which the names of Australia’s missing in this sector of the front are carved. In the middle is a tower - it still bears the scars of the war that followed the war to end all wars.

Visitors can climb the tower, where they can get a commanding view of the countryside. You can see the town itself, and the distant shapes of other strategic features - for example Le Hamel, which we’ll talk about at the end of this log entry. Even if you’re not interested in military minutia, the view is amazing.

It was as we left the tower that one of the most curious and strangely moving episodes of this tour occurred. As I walked down the front steps, I saw a man with a bugle in British service dress - the uniform of the British Tommy - and an officer trudging up to our position. Somehow, in the middle of France, I had encountered some reenactors. It turned out there were seven of them - three men in Welsh Guards uniforms, a Highlander, a nurse, and two members of the Royal British Legion. They’d been deputised by an Australian family to pay tribute to one of their members lost in France during the war.

Suddenly, we were conscripted into this odd little ceremony. We gathered around - the bugler sounded the Last Post, there was a minute’s silence, and then two of us left a wreath in the tower as the Highlander played his bagpipes. It ought to have been very silly, this memorial service with these men in old uniforms, recorded on an iPhone for a faraway family. And yet I teared up. I don’t know why this got me, but I think part of it is the spontaneous nature of the event. These guys were from Wales and England. They had no obligation to pay one of our men this heed - and yet they did, and they went to such effort to do it. We even sang the national anthem together - I can’t remember the last time I actually sang it.

We interrogate forms of remembrance a lot on this course - it’s kind of the point - and we did have a little discussion of this a bit later. Sometimes I feel we as historians can be a little too cynical about this sort of thing. I don’t know if crossgeneration or surrogate grief is something that can be quanitified, but it was real for them, and I think that’s what really mattered.

And then we went into the Sir John Monash Centre. And oooooooh boy.

Remember how I said the museum at Peronne didn’t meet my expectations? Well, this exceeded my expectations, and it did so triumphantly. I expected that this would be bad, but what I got was a nearly heroic example of utter shitness. It crosses the line into utter inappropriateness, speeds right across the world like the Flash, and crosses the line a second time. I’m almost impressed.

First of all, everything - everything - is digitally integrated. You actually have to install an app onto your phone andhave headphones plugged in (or rent them for three euros) to understand anything that goes on here. You then walk up to screens - it’s almost entirely screens, like a sale at Harvey Norman - and press the number of the screen - except if its already playing, the recording just picks up where it already was, which is often halfway through the video. If the screen is out of order, well, no content for you. The inevitable question, of course, is how would you interact with this if you were blind, or deaf? I guess being deaf is just un-Australian.

And the content? I will be fair here and say nothing is technically incorrect, or at least nothing I was actually able to view and hear. My problem is more about what the museum doesn’t say. Monash’s somewhat indifferent career commanding 4th Brigade is neatly glossed over. So too is the Hindenburg Line battle of 29 September, and don’t worry, we’ll get to that. Every other combatant in the war is a footnote, which gives the impression that Monash and the Australians are personally winning every major battle of 1918. Then there’s the language - Australian units withdraw, while British units are shattered. All this is underlined with dodgy, overacted dramatisations and a tactical war that uses 3D models to showcase the battles of Fromelles, Polygon Wood, Amiens and St. Quentin - all rather badly posed, and all looking like they came out of a pre-alpha version of Battlefield 1.

Then there’s the experience. The experience is what this whole thing is built around - the brilliant idea to have a light and sound show right beneath the graves of the dead, giving the visitor a feel - as if that’s possible - of what the Villers-Bretonneux and Hamel battles were like. I actually managed to get a session where I was the only oneside when it started (the door shuts while it’s playing.) I am truly thankful I was. When the government commissioned historians to plan this, they outright said that they wanted visitors to feel ‘pride with a touch of sadness.’ It would probably be difficult for audiences to feel such emotions if they were sharing a room with a university student pissing himself laughing.

Yes, this is conceptually appalling to me - but it’s also so silly that I couldn’t help but laugh, and laugh hysterically at some points. After opening with British troops fleeing Operation Micheal, literally screaming and crying - I’m surprised the director showed enough restraint to stop himself from staining all their trousers with wet patches - a sinister German voice who’s probably meant to be Hindenburg but sounds more like Major Toht from Indiana Jones declares his intention to destroy the British. The viewer is ‘gassed,’ which feels more like sitting in a smoking room at Hong Kong Airport. Then come the brave, steely-faced Australians, counter-attacking alone into Villers-Bretonneux. They get into the Beastly Hun with their bayonets. Some die and it is Sad. One kicks in a door and hip-fires his Lewis Gun into three Germans Rambo-style whilst going “AAAAAAAAAAA” - and then I don’t know what happened for the next ten seconds because that scene was so ridiculous I started cry-laughing.

Then we move onto Hamel, and here comes the great hero, Monash. He points at maps. He walks next to tanks. He stares heroically into the distance. There are no other generals, or even other officers - there is only Monash. (I could almost feel the ghost of Pompey Elliot swearing up a storm next to me.) Monash unleashes his vague powers of tactics upon the Beastly Hun, and the Australians go in. The Germans all have gas masks and therefore have no faces, making it okay to kill them. The sound of artillery forms the drum beat of a Hans Zimmer style musical track as the battle goes on. There’s tanks. There’s explosions. There’s strobe lights. There’s another bloke hipfiring a Lewis Gun and going “AAAAAAAAA.” There are no Americans. Americans don’t exist. And then, because the director suddenly realised that this is meant to be a site of commemorative diplomacy, a brave Australian soldier waves a French flag. Monash has won the war.

If I tried to come up with a satirical depiction of Australian history, I honestly couldn’t beat this. It is sublime in its idiocy. I want this on DVD. I want to show all my family and friends. This might be the best First World War comedy since Blackadder.

Don’t get me wrong, I think this is very offensive and it shouldn’t be anywhere near a cemetery, let alone under it. But at some point, you just have to laugh.

Now there’s one big problem with the Centre, apart from everything else, and that’s the name. John Monash fought a lot of key battles in the Australian Corps’ history. Villers-Bretonneux was not one of them. I do wonder if there was another option here, to focus not on Monash but on Harold ‘Pompey’ Elliot, a superb brigadier who was haunted by his experiences of the war, and whose life was tragically cut short by the consequences of PTSD. At very least, he was actually there and played an important part in the battle.

The Sir John Monash Centre is not the best museum in France - in fact, it’s not even the best Australian war museum in Villers-Bretonneux. That laurel belongs to the French-Australian Museum in the town itself, which we visited afterwards. This is in the top story of the local school, which was rebuilt after the war with subscription money raised by Victorian schoolchildren. To this day, there’s a sign above their courtyard - ‘DO NOT FORGET AUSTRALIA.’ The museum is very small and very intimate, although perhaps a little scattered - it’s clearly a labour of love, a collection of a few treasured relics, models and artworks that connect this small French town with a country on the far side of the world. The assembly hall, which the staff kindly let us go into, is decorated by wooden carvings of Australian animals made by a disabled Australian veteran after the war. This probably cost a fraction of the Sir John Monash Centre, and is probably maintained by two staffmembers and a goat, but it is worth infinitely more than that supposedly ‘world-class’ installation.

Sadly, this museum doesn’t get many visitors anymore - all the tour groups want to go to the glitzy new thing down the road. So here’s my advice - go to the Australian Memorial by all means, but skip the Centre, unless you want a quick laugh. Come here instead. You won’t regret it.

The main teaching for today ended at Heath Cemetery, where we discussed some Aboriginal soldiers’ graves that we’d actually found out about at the aforementioned museum. It’s hard to find Indigenous soldiers - as Aboriginal people were banned from the armed forces, those that passed as white were hardly going to write what they were on their enlistment forms. It’s led to a significant part of the AIF’s history being obscured - but today, it’s being reclaimed as families find their veteran ancestors, dead or alive. In fact, one of the few things I liked about the Centre was an art installation of two emus made from (imitation) barbed wire - a symbol of these men who died so far from Country under an unfamiliar sky, with no Southern Cross to guide them home.

We headed back to Amiens, and most of the group alighted here, but a few of us - the cool members of the group - went back out to the memorial at Le Hamel. This is a curious memorial, but I don’t hate it - it’s basically a big slab in the middle of a wheatfield with the Australian, American, British, French and Canadian flags flying above it. (This is where the Red Baron was shot down, and as the Canadians still think they got him, they get to have a flag.) Plaques on the path to the memorial describe the course of the battle fairly well (although I feel they do a bit of an injustice to the Tank Corps, which are never mentioned by name.) Once there, you have a pretty good picture of the fields leading to Le Hamel, the town that Monash famously captured in ninety-three minutes on the 4th of July 1918.

Hamel was a great achievement, but it needs to be put into context - this was a local action in preparation for the real offensive at Amiens in August. Here Monash also performed very well, but so too did Currie and the Canadian Corps, and Sir Henry Rawlinson in overall command. (The British III Corps advance was less impressive, but still outstanding by Western Front standards.) Between Hamel, Amiens and Mont St. Quentin, Monash more than earned his reputation as an outstanding commander. But he wasn’t infallible, and now I can finally talk about 29th September 1918 and the St. Quentin Canal.

Monash and the Australian Corps were meant to be the main force here. IX Corps (remember them from Suvla?) were to swing south in a secondary role, while III Corps, whose commander had just been sacked, was mostly left out. By this time, Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes was insistent that the Australian divisions be taken out of the line for a rest, and this had already happened with the 1st and 4th Divisions. Monash and Rawlinson had managed to hold onto the 2nd, 3rd and 5th Divisions for this final action against the Hindenburg Line, but had had to replace the other two with the 27th and 30th US Divisions. These troops were nowhere near as experienced as the men they’d replaced, but Monash’s plan doesn’t seem to have accounted for that, and he used a strategy he’d used to great effect at Amiens - send two divisions in first, then leapfrog them with fresh divisions once the first wave had taken their objectives.

The Americans performed about as well as could be expected, and their bravery was in no doubt, but they didn’t know how to properly clear out the German trenches that they were advancing over. Inevitably, when the Australians came in, they ran into German strongpoints that had been temporarily suppressed, but not destroyed. This resulted in heavy casualties and bogged down the advance. A frustrated Monash took days to pound through, and with the benefit of hindsight, he really should have altered his plan to account for the greener troops - instead, he and Rawlinson, somewhat unfairly, blamed them.

All this was probably academic, because while the Australian Corps was pounding along, the Hindenburg Line had already been broken. Remember how I said that I didn’t think Mont St. Quentin was the greatest military achievement of the war? I define military achivement differently to Rawlinson. Taking a position against all odds is definitely impressive, but carrying out an operation so effectively that your troops don’t really need heroic daring do is quite another, and this was what happened on the IX Corps front in the south. The 46th Division at Bellenglise - as standard and normal a division as any - had swept across the St. Quentin Canal in perfect concert with their artillery, capturing an intact bridge and the village. For the loss of 800 casualties they captured over 4000 men, and tore a gaping hole in the Hindenburg Line that the following 32nd Division was able to exploit. This, in my opinion, was the outstanding military feat of the First World War - because so much was gained for such (by Western Front standards) a cheap cost. Rawlinson rightly shifted the main axis of his advance south to support it, and after a few more days of hard fighting, the Australian Corps was finally taken off the line for a well deserved rest. The war would end before it could return.

Well, that was a digression and a half. Tomorrow we leave Amiens, heading down into the Somme for the last big day of battlefield touring, and then onwards to the City of Lights itself.

Oh, one last story before I forget - our professor dug this up while looking through Monash’s correspondence for a history of Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance. Towards the end of Monash’s life, he began to think of what he ought to leave for Australia. As a war hero, he thought, he needed to leave them an example to look up to. As he was making arrangements for his legacy, he noted particular papers that he needed dealt with properly, as a matter of national importance.

So, shortly after he died, someone gathered these papers - I think his executor. As John Monash was buried in his modest grave, marked only with his name and eschewing his many honours, this person took them somewhere safe - perhaps an incinerator, or a bonfire in the bush. I can imagine this person, a tear in his eyes, a bugler playing the last post, as he was forced to consign a major piece of Australian history to the flame.

But duty called, and this man would obey. And therefore, with a heavy heart, he destroyed General Sir John Monash’s enormous collection of pornography.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

the 19th century research

The 19th century began on 1 January 1801 , and ended on 31 December 1900. Napoleon Bonaparte, Emperor of the First French Empire. The 19th century was characterized by vast social upheaval. Slavery was abolished in much of Europe and the Americas.

the people in the 19th century had very interesting fashion which consisted off grand ball gowns

what I like about the 19th century is their big skirts, I do add long lavish skirts to my original characters just because they're pretty and nice, I also like the colours and the shape of the dress which is a kind of off white

during the 19th century multiple major events went on which consisted of ;

·̩̩̥͙**•̩̩͙✩•̩̩͙*˚ ˚*•̩̩͙✩•̩̩͙*˚*·̩̩̥͙

The Napoleonic Wars (1802-1815)

Following the Revolutionary Wars in France, with Napoleon positioning himself as Emperor of the French Empire, over a decade of war in Europe followed, as nervous neighbors hoped to dethrone the General. Not afraid to get on the battlefield to force his politics, Napoleon conquered Italy, much of Spain, and by 1812 ruled most of Continental Europe. Britain and Russia remained thorns in his side, coalition forces rallied against Napoleon and ousted him, forcing him to exile on the island of Elba. After an escape and a brief resurgence, he was defeated for good at the Battle of Waterloo (1815), exiled permanently to Saint Helena where he would die, and the French monarchy was restored.

during the napoleonic war the British was against the French, the British was irritated by the French for several actions during following the treaty of the Amiens

the treaty of Amiens was a treaty signed at Amiens, by the French, British, Spain, and the Batavian Republic (the Netherlands), achieving a peace in Europe for 14 months during the Napoleonic Wars.

because my cult is set in a Australia esc place I have decided to look more into the Australian side of history which I do not do often so do not mind if I get anything wrong

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Detail of Napoleon in The Peace of Amiens, by Anatole Devosge

The Peace of Amiens was the treaty in 1802 which ended the War of the Second Coalition. The peace would be short lived as Britain would declare war on France one year later. It was, however, the only period of general peace in Europe since the start of the Coalition Wars in 1792.

#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#Anatole Devosge#the consulate#Devosge#painting#first consul#napoleonic#napoleonic era#first french empire#French empire#France#history#peace of Amiens#Amiens#treaty of Amiens#1800s#19th century#art#art history#history of art#french revolution#frev#french history#Bonaparte#historical art#neoclassical#classical#neoclassicism#neoclassical art

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amiens Labyrinth

Labyrinths have always exerted on the human imagination a very special attraction, due to the symbolic content, as a representation of the creation, by the living image present in the collective unconscious of the Icarus' ill-fated escape from the labyrinth of Daedalus, from the constant danger of mortal attack of the Minotaur and, finally, for the aesthetic beauty of its

intricate convolutions. Present in many ancient constructions, time and the wicked They were relentless with the labyrinths, leaving only a few. various churches Gothic houses exhibited labyrinths on their floors, like those in Chartres and Amiens. Dowsing is one of the most difficult and sophisticated devices utilization. Easier is that of Amiens than that of Chartres. Make as large a copy of the attached graph as possible, 50 cm in diameter. The emissions are made in the center. This time, for vary, I'm going to give you a problem:

investigate the sense of alignment;

The polarities;

The EIFs;

The levels;

The hourly frequencies of emission;

The orientation of the BCM spectrum (Bélizal-Chaumery-Morel) and its phases;

What devices to use to alter emissions;

Biometric fees.

Dowsing is that, research! and, ... sometimes, what is hidden reserves us the most beautiful surprises...

Replica of the existing design on the floor of the old Cathedral of Amiens (France). In its center we find powerful energies with vibrations of up to 18,000 angstroms, the same vibration found in the King's Chamber in Great Pyramid of. Egypt. In order to have an idea, the human being has to 13,000 to 14,000 energy points; in touch with 18,000 human being it balances.

Usage tips:

1. To energize the water, place the graphic under a glass of water at night and drink in the morning on an empty stomach.

2. To rejuvenate dead skin cells against pimples and wrinkles, pass the energized water on the face. Help cure infections.

3. To strengthen and heal diseased plants, place the chart under the themselves or in places close to the roots. The decagon also serves to this function.

4. To restore the health of the animals, place the graphic in the places where they usually sleep.

5. To preserve fruits and vegetables, place the chart under the fruit bowl or inside the fridge.

6. To restore the health of diseased organs, place the graph by under the mattress of the bed at the height of the affected area.

7. To get peaceful sleep, cure headaches, put chart under the pillow.

8. Protect and clean places or environments from telluric or other energies unwanted vibrations from people, appliances. To do this, place the graph in the environment as a decorative piece or do it intentionally.

9. You can put a piece of paper with a goal to be achieved by time, healing, emotional balance, expansion of consciousness, etc. nhance the objective with the aid of a decagon for about 30 minutes, placing it in then about the Labyrinth and about the purpose and photo or testimony of the person under treatment. Define the time required for each application and keep the device in this way until you reach the goal.

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

💖🙌🍎 for the writer's ask <3

💖 Which of your fics is your pride and joy?

Ooooh more highlighting of beloveds <3 Damage Gets Done was my first dipping of my toe into writing for the Hornblower fandom, and I am very, very happy with how it turned out! It got way longer than I planned, and I'm actually debating making a part two to tackle The Great Kingston Debauch of 1802(1801? sometime right before the Peace of Amiens, so I'm guessing early 1802), and how Archie's presence and then death would effect it!

🙌What's a line or paragraph of yours that you're proud of?

This is actually a line from Damage Gets Done!

"It was true to form, if nothing else," Buckland said, his voice strange and frail. "You three: you are so full of yourselves, and of each other... You think me a fool." It was true, and more true perhaps of Horatio than of any of them, from his position of genius; Bush pitied him, Archie looked down on him, but Horatio? Bush did not think Horatio thought of him at all, except to maneuver around him in order to stay on course, as if he were an inconveniently placed bit of shoal. Buckland was as dangerous, too, as sudden shallows were to the safety of the ship - though not so dangerous as Sawyer's erratic moods had been, like an malignant squall; whatever damage had been done to Renown, to her crew's morale, was not the sin of youthful recklessness, but of frail and unfit officers.

🍎What's something you learned while researching for a fic?

I answered this one here but long story short: scurvy is awful

thank you for the ask! I think this is the last of them!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Massena is stingy but civil

This was from some English aristocrat...

Frederick Foster To (his son) Augustus Foster. Marseilles, Dec. 27, 1814.

My dearest Augustus. . . . We have seen Massena. He is, I believe, stingy, but very civil, and very interesting to see. Bonaparte on embarking for Elba sent him his amities, c'est un brave homme je l'aime fort—but Massena says he, Bonaparte, loves nobody; that once when he was ill, Bonaparte never took the least notice of him, never even sent to enquire, and that at another time, when he was also unwell, and that Bonaparte had need of his services, he used to come and see him three or four times a day. He thinks he was a man de grandes conceptions, particularly when things went on well, but that in adverse fortune he failed....yet Massena seemed to have a kind of liking for him; said that it was him who had named him I'enfant de la Victoire, and pointing to his great coat said he was happier when he bought that, it was at Vienna...Massena is much broken and altered from what I remember him at the peace of Amiens. He and Wellington met at Paris, and after a stare Massena said, "Milord, vous m’avez fait bien penser.” "Et vous, monsieur le Maréchal, vous m’avez souvent empêché de dormir."

The two duchesses, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, Elizabeth, Duchess of Devonshire, 1898

archive

hathitrust

(Milord, you really had me thinking. - And you, Marshal, you often made me lose sleep.)

#Massena sighting#English aristos visit France and see Napoleonic figures#Massena repeats that story again later it apparently really galled him#I don't blame him

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog Thirty

I’ve decided I’ll change my blog format slightly, as is the case of recently when there were several days where I may have done very little, I think that I’ll try and follow some prompts that I was given at the very beginning of my “correspondence” agreement. Of course, if I have done something interesting, I would go into detail but it’s unnecessary and a bit redundant if I say that I didn’t do anything on a certain day.

On the 26th, I visited the Place de Vosges in Le Marais, a place that my French teacher has told me is where the French elite (used to) live. It was most famously home to famous writer Victor Hugo for a long span of his life (as he moved around frequently until settling down in the famous square). I thought that it was cool to be able to walk around his old home but really there wasn’t much to see in terms of exhibits/displays. I did enjoy the center courtyard area where there was a little museum café where you could enjoy a snack or drink in peace.

Interspersed with these things, I’ve spent a decent amount of time doing random errands in preparation for school as well as things that (hopefully) can progress my professional career somewhat in the future. Included in these activities was cleaning out my dorm and packing stuff away into a storage unit.

On Monday the 31st, I arrived in Amiens. This was to be the first day of my month-long travel throughout France, the Benelux Region, and Germany. After putting the last of my items in my storage unit, I left Cergy for Paris and left Gare du Nord in the morning for Amiens. For some reason, there weren’t any seats left on the train, so I had to stand for the hour-long ride. I arrived in an overcast city with a steady rain, something I had not been expecting in the end of July. The first thing I saw after stepping out of the train station was a tall tour that stuck out of the surrounding buildings. I then noticed the large cathedral sticking out of the buildings in the distance. Lastly, I noticed the large number of brick buildings that seemed to dominate certain portions of the city. To kill time, I looked for something to do and found out that there are canal boat tour rides available near the city center. I got to the welcome center and booked myself a ride through the labyrinth of canals. Unfortunately, the rain continued even during this ride making it a very wet ride to endure.

Up next after Amiens is Arras, followed by Lille, then Ghent, then Brussels, then Utrecht, then Cologne, then Luxemburg, then Metz, then Nancy, then back to Paris.

2 notes

·

View notes