#the paradox of open

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

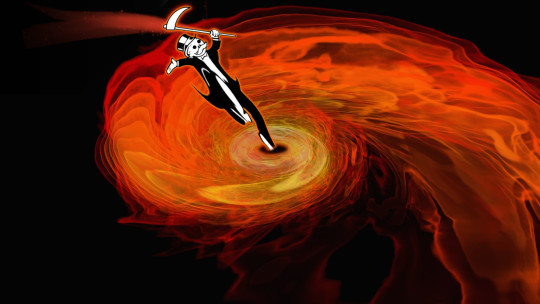

Monopoly's event-horizon

When a superdense, concentrated mass forms a black hole, the laws of physics around it change, giving rise to an eldritch zone where the normal rules don’t apply. When corporations form a concentrated industry, the laws of economics likewise change.

Take copyright: when I was a baby writer, there were dozens of comparably sized New York publishers. The writers who mentored me could shop their rights around to lots of houses, which enabled them to subdivide those rights.

For example, they could separately sell paperback and hardcover rights, getting paid twice for the same book. Under those circumstances, giving authors broader copyrights and easier enforcement systems could directly translate into more groceries on those authors’ tables and more gas in their cars’ tanks.

But today, publishing has dwindled to five giant houses (possibly four soon, depending on whether Penguin Random House successfully appeals its blocked merger with Simon and Schuster). Under these conditions, giving exploited authors more copyright is like giving bullied schoolkids more lunch-money.

Whatever copyright authors get will be non-negotiably extracted from them via the near-identical, unviolable core contracting terms from the Big Five publisher. Today, the bullies don’t just take your paperback rights, they also acquire your audio and ebook rights.

Most of them now want your worldwide English rights, so you can’t resell the book in the Commonwealth, and some have started demanding graphic novel, film and TV rights.

In our new book, Rebecca Giblin and I call this “chokepoint capitalism”. In today’s highly concentrated creative labor markets, copyright’s normal role of giving creators bargaining leverage over their supply chain is transformed.

https://chokepointcapitalism.com

Instead of being a tool for creators, copyright is inevitably transferred to part of the supply chain — a publisher, label, streamer, ebook retailers, etc — where it becomes a tool to beat up on the rest of the supply chain, especially creators.

But copyright isn’t the only policy that breaks down at the event horizon of monopoly’s black hole. Policy itself breaks down, too. When power is pluralized among lots of firms an expert regulator can ask a technical question like “Does net neutrality lead to a decrease in private infrastructure investment?” and get lots of answers.

Some companies — cable operators hoping to override your choices about which data you want by slowing down traffic from sites unless they pay bribes — will insist that they can’t afford to build fiber without this incentive.

Others — ISPs who want to raid the cable operators’ customer base by giving you the data you request as fast as they can — will answer this charge. Both will provide supposedly empirical about their investment choices and capital and running costs, and both will vigorously probe the others’ submissions for factual weaknesses.

But when all the internet in your country has been monopolized so that nearly all Americans have little or no choice of ISP, the truth-seeking exercise of regulation becomes an auction, with the monopolists bidding together to bend reality (or regulation) to their will:

https://muninetworks.org/content/177-million-americans-harmed-net-neutrality

This is called “regulatory capture”: when there are four or five companies running an industry, nearly everyone qualified to understand it is an executive at one of those companies. Obama’s “good” FCC chair was a cable lobbyist, Trump’s “bad” chair was a Verizon lawyer.

Ironically, the term “regulatory capture” originated with right-wing, anti-regulation nihilists. They argued that capture was inevitable and the only way to preserve competition was to eliminate all regulation, including the regulation that blocked monopoly formation.

https://doctorow.medium.com/regulatory-capture-59b2013e2526

Eliminating anti-monopoly rules had the entirely predictable effect of producing lots of monopolies. Today, nearly every global industry — beer, shipping, banking, athletic shoes, concert tickets, eyeglasses, etc — is dominated by a handful of firms:

https://www.openmarketsinstitute.org/learn/monopoly-by-the-numbers

Today, the same people who advocated for removing anti-monopoly rules in every administration since Reagan’s insist that their deregulation has nothing to do with the growth of monopolies — that these monopolies arise out of some mysterious force of history: when it’s monopoly time, you get monopolies.

This is a wild thing to say aloud among reasonably intelligent adults, like claiming, “Well, when we put out rat poison, we didn’t have a rat problem. We stopped, and now we’re overrun by rats. But it would be hasty to assume that removing the rat poison led to the explosion of rats (by the way, does anyone have a cure for the plague?)”

But if you haven’t paid close attention to the history of antitrust law since the late 1970s, all of this might feel mysterious to you — or worse, you might mistake the cause for the effect: regulators keep making corrupt choices, so regulation itself is impossible.

This is like the artists’ rights advocate who says, “artists’ incomes keep falling, so we need more copyright” — in mistaking the effect for the cause, both blame the system, rather than the corporate power that has corrupted it.

The same is true in our online “censorship” “debate,” which poses the issue of speech online as one of “which speech rules should the Big Tech companies that have transformed the internet into five giant websites filled with screenshots of the other four adopt?”

https://doctorow.medium.com/yes-its-censorship-2026c9edc0fd

Good communities need good rules, sure — but by focusing on which rules we have, rather than what keeps people stuck in social media silos that have manifestly bad rules, we miss the point. Absenting yourself from the major social media platforms and online messaging tools extracts major costs on your personal, professional, educational and civil life, so many of us stay within those silos, even though every day we spend there is a torment.

The focus on penalizing firms with bad rules is another one of those mistaking-the-cause-for-the-effect-and-making-it-worse phenomena. A fine-grained, high-stakes duty to moderate makes it effectively impossible for small platforms — say, community-owned co-ops — to offer an alternative to Big Tech.

And once Big Tech platforms have a duty to police their users, they can argue, reasonably enough, that they can’t also be forced to interoperate with other platforms whose users they can’t spy on and thus can’t control.

The case that bad community managers give rise to toxic communities breaks down under conditions of monopoly, since attempts to improve platforms with billions of users are a) doomed (there is no three-ring binder big enough to encompass all the rules for three billion users) and b) inimical to standing up smaller, easier-to-administer communities.

Monopoly’s singularity also applies to free software and open source. In the mid-1980s, Richard Stallman coined the term “free software” to apply to software that respected your freedom, specifically, the freedom to inspect, improve and redistribute it.

These were considered the necessary preconditions for freedom in a digital world. Without a guaranteed right to inspect the code that you relied on and correct the defects you found in it, you were a prisoner to the errors or ill intentions of the software’s original author.

In 1998, another name was proposed for software licensed on “free” terms: “open source.” Nominally, this term was intended to resolve the ambiguity between “free as in beer” and “free as in speech” — that is, to make it clear that “free software” didn’t mean “noncommercial software.”

This was said to be necessary to resolve the fears of commercial firms that had been frightened away from free software due to a misunderstanding. As part of this shift, advocates for “open source” shifted their emphasis from free software’s ethical proposition (“software that gives you freedom”) to an instrumental narrative.

Open source software was claimed to be higher quality than proprietary software, because it hewed to the Enlightenment values of transparency, replicability and peer review (“with enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow”).

Along with this claim, there was a second argument that open source software was cheaper to develop because a “community” would gather to help maintain it. Sometimes, this was couched as a “commons” where lots of actors, large and small, would work to produce a community good.

In 2018 Benjamin “Mako” Hill delivered a keynote to the Libreplanet conference that was a kind of postmortem to the 20-year experiment in instrumentalism (open source) over ethics (free software):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vBknF2yUZZ8

Mako concluded that the experiment was a failure, producing a situation in which the tech giants enjoyed unlimited software freedom (because they ran the cloud servers we all depended on) while the rest of us merely had open source (the right to inspect the software powering the cloud, and to suggest ways to modify it).

In this account, the shift from ethics to instrumentalism paved the way for a series of compromises that turned the commons into a sharecropper’s precarious farmstead. When the open community was asked whether cloud software should be subjected to the same copyleft terms as software distributed for users, they weighed this as an instrumental proposition (“will this make the software better”), not an ethical one (“will this give users more freedom?”), and concluded that the answer was “this is fine.”

I think there’s a lot to this explanation — if nothing else, it explains how such a drastic shift took place without much hue and cry. But there’s another phenomenon at work that Mako’s account doesn’t grapple with: the rise of tech monopolies.

The reason that ethical propositions related to software freedom were sidelined so effectively in the decades after 1998 is the increasing power of tech monopolies: as tech giants gobbled up their competitors or put them out of business with predatory pricing, they gained power over regulators, universities, and individual technologists (increasingly employed by or dependent on a tech giant).

Copyleft — like copyright — breaks down at the event horizon of concentrated corporate power. With copyright, the breakdown manifests as the appropriation of copyright’s “power to exclude” by the firms it was supposed to be wielded against. With copyleft, it manifests as “software freedom” being hoarded by the same firms that copyleft licenses were supposed to keep in check.

This phenomenon isn’t limited to free software — it also plagues open-licensed “content” — material released under Creative Commons licenses, say. A year ago, Paul Keller and Alek Tarkowski published an important essay on “openness” entitled “The Paradox of Open”:

https://paradox.openfuture.eu/

In this essay, the authors — both significant contributors to the world of free software and open content — identify a phenomenon akin to the Mako’s observation of “freedom for big companies, openness for the rest of us.” From Openstreetmap to CC-licensed creative works, corporate monopolies have supercharged their power by plundering the commons.

This month, Open Future, who published “Paradox,” published a series of responses to the original paper:

https://paradox.openfuture.eu/responses/

They are uniformly excellent, but the one that I am most interested in comes from James Boyle, “Misunderestimating Openness”:

https://openfuture.eu/paradox-of-open-responses/misunderestimating-openness/

Here, Boyle sharply disagrees with Keller and Tarkowski’s argument, grouping it with similar claims about content moderation and censorship, arguing that openness was only ever a necessary — but insufficient — precondition for a better world. In the same way, online speech forums might be terrible places, but this is a failure of their moderators and their communities and their business-models, not an indictment of the idea of online discourse itself.

Both papers grapple with concentrated corporate power as a corrupting force, but neither puts it in the center of the breakdown of otherwise sound practices.

Reading all these people whom I respect and admire so much debating whether “openness” is good or bad makes me even more certain that fighting concentrated corporate power is the precondition for success in all other goals.

Fighting concentrated corporate power may seem like a tall order, and it is, but in that fight, we have comfort in a key idea from Boyle’s own work.

Boyle describes the history of the term “ecology.” Before this term was in widespread use, it wasn’t clear when two people were engaged in the same struggle. If you care about endangered owls and I care about the ozone layer, are we on the same team?

What do charismatic nocturnal avians have to do with the gaseous composition of the upper atmosphere?

The term “ecology” turns these issues (and a thousand more) into a movement.

Today, there are people of all walks of life living in all kinds of hurt who think their pain is caused by phenomena that are downstream of corporate power. Once we figure that out — once we figure out that to make our tools work again, we need to escape the event horizon of the capitalist singularity — then we can really begin the fight in earnest.

Image: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (modified)

CC BY 2.0 (asserted; more likely public domain) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

[Image ID: A NASA rendering entitled 'Neutron Stars Rip Each Other Apart to Form Black Hole,' pictured as a Fibonacci spiral of glowing red lines on black background. Superimposed over this is an image of Monopoly's 'Rich Uncle Pennybags,' clutching a Grim Reaper's scythe rather than a cane, his face a skull. The lower half of his body has been stretched and is disappearing into the black hole at the center of the NASA image. He is limned with red and orange and sports a red/orange comet-tail.]

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

I keep forgetting about Tumblr and it's been going for long enough so I'm just gonna dump all the "reimagined paradoxes" in here, not gonna make a separate post for each of them 💀 But in general, I based the past ones off of real life fossil organisms or things that might have been present in our past, and the future ones were mostly based off of spec evo or some other form of natural progression I think that pokemon species might have but not like a regular evolution or mega, if that makes sense??? Anyways let's hope I don't make the next post in 5000 years 💀💀💀

#myart#digital art#artists on tumblr#illustration#creature design#creature art#speculative evolution#paleontology#fakemon#fakemon design#commissions open#sugimori style#pokemon#paradox pokemon#pokemon scarlet and violet#paldea region#jigglypuff#delibird#amoonguss#hariyama#misdreavus#hydreigon#volcarona#magneton#tyranitar#salamence#gardevoir#gallade

593 notes

·

View notes

Text

it's pride month you know what that means. this trend !!!

#rain world#rain world fanart#slugcat#rw rivulet#rw artificer#my art#god i predicted this#i open tumblr and its filled with this trend LOL#its barely even mean 10 hours#anyways enjoy the paradox#expect some super gay posts this month

343 notes

·

View notes

Text

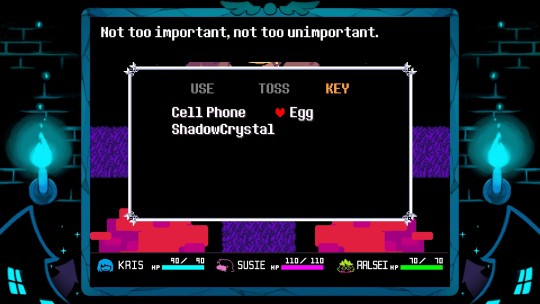

Hmm

#deltarune#when I replay ch 2 i should keep my eye open for any similarly paradoxical turns of phrase

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

yeah i dont rlly care about genderbends unless theyre doing something particularly interesting *imagines character but butch* holy shit

#LIKE IT JUST ADDS SOOO MUCH#n this goes for characters that are canonically men or women i think its cool to imagine in aus n shit#like personally i imagine wade the future amy from faction paradox as a butch lesbian on t#and i literally just thought of like making doctor who au where 10th dr who is butch and my third eye opened#warlock wartalks

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

i tried to fix an old drawing that i drew when edN came out so here's the new version

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

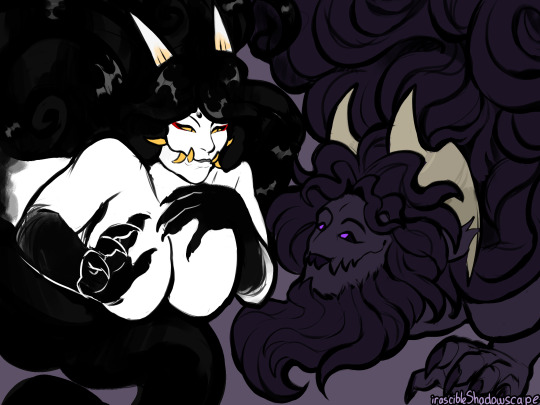

demon greeting or whatever

I've had this idea ever since I first saw @majimasleftasscheek's Ms. Hannya which was checks calendar almost two years ago, cause yooo fellow long jaw design lets gooooooooooo

#my art tag#irascibleshadowscape#irascor#oc#paradox#ms hannya#LOOK AT HOW WIDE I CAN OPEN MY MOUTH#NO WAY LOOK AT MINE

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am once again overcome by the sheer magnitude of pranks Mikey and Leo could commit on the world of archaeology through their combined abilities of time and space

With enough time for Mikey in particular to be strong enough to make a small time portal - again within Leo’s portal opened in Someplace, Somewhere - they could plant so much shit just to mess with historians.

Like - Mikey wanted to try painting Greek-style pottery and Leo is like “hey hey wait…”

And now there is newly discovered evidence of Greek depictions of humanoid turtles laying around.

#rottmnt#rottmnt leo#rottmnt mikey#rise of the teenage mutant ninja turtles#rottmnt headcanons#‘but wouldn’t that be a paradox? wouldn’t it be a different timeline?’#that’s what Leo’s mainly there for!#I see Mikey’s abilities as time based#so he doesn’t have too much control over where that timeline is just how far back or forward#so it could be a different but parallel world to theirs if left as is#but I see LEO’S abilities as specifically space based#so with his portal acting as a homing spot for Mikey’s to open within#it can cause the time portal to open within the same timeline#and YES that does imply that all the shit they plant is already there lol they just don’t think about it#and yes Donnie does in fact get on their case in regard to Paradoxes but then decides it may be cool to see happen soooo#poor Raph has no idea what’s going on but Mikey and Leo are laughing hysterically#and Donnie is muttering with a maniacal grin about how fast the universe may implode if they mess things up enough#I would also like to note that while I do see Mikey’s abilities as more time based - since he IS the future greatest mystic warrior ever-#-I ALSO think he possesses the ability to harness smaller aspects of his brothers powers#not so much their abilities in entirety but more so base components#look at me and my paragraphs of tags once again rip

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paradox Live Stage Battle "COMIC" — Opening Show 1 English Translation

[Reading: Right to Left]

T/N: This translation has been a couple months in the making, but I'm glad to say that I've finally been able to post it! Earlier this year, I decided to start translating this manga since there seemed to be no active translation at that time (and when I last checked). I do intend to catch up with the newer manga releases at some point, though it may take awhile since I am going at my own pace.

The schedule is quite irregular right now, but future chapters should come out around Friday 12PM K.

I'm not the most fluent in Japanese, but I feel confident enough in my skills to take on a project like this. I also apologise if some of the phrasing in the dialogue sounds weird since I did change my approach to translating this manga halfway through when I started to translate this chapter. I did have this beta-read, but I haven't fully reread it besides revising the pages, so hopefully it still turned out well.

#paradox live#paralive#bae#the cat's whiskers#tcw#cozmez#akanyatsura#akyr#buraikan#paradox live stage battle comic#opening show 1 translation

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

#bird box#cam#cam 2018#the cloverfield paradox#the perfection#apostle#the open house#tau#tau 2018#velvet buzzsaw#in the tall grass#eli#eli 2019#poll#horror#horror film#horror poll#movie poll#film poll#horror movie#movie#film#horror movie poll#movie polls#movies#films

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

etherial

#volcarona#paradox pokemon#pokemon scarlet and violet#slither wing#moths#pokemon#pkmn#i love them#my art#open commissions#digital art

620 notes

·

View notes

Text

eh screw it. paradox ultra beast makes no sense in my head which means it makes sense to Pokémon standards. they did it to ancient legendaries after all. I like dinosaurs.

Past Paradox Xurkitree— Luminescent Lifeform (Credit to @menthum-mint for name and for helping with the concept of this guy as well)— takes a more literal sense with the tree. I think it’s actually Ghost/Electric, maybe. It has two different stances; Rooted and Uprooted. It usually fights in its Rooted form where it plants the three large roots at the end of its tail into the ground where it absorbs a peculiar energy from the soil of Area Zero to fight stationary. When it goes into its Uprooted form, the intense energy it’s collecting in the ground creates a blast as it rockets itself into the sky to land on it’s hands and run that way, capable of sprinting at exceptional speeds. They’ve been noted to travel or collect in groups of usually their own kind. They seem to partake in a lot of playful aggression, throwing around what or whoever’s interesting to them which might seem mean, but it’s all in good fun for it. It doesn’t really know its own strength on that department.

some creative notes— there’s some inspiration from the Tree of Souls (?) from Avatar (the movies). There’s also a single vine that hangs from the split branches to it’s “head” which is supposed to somewhat imitate a mouth with a long tongue sticking out like it’s teasing you. This is just something I incorporated for fun and for some extra personality

#JUST A SILLY TREE GUY#I like this guy a lot. like a lot a lot#so goofy#these are super messy concepts but I’m trying to open up to just having more messy pieces for my own convenience really#Luminescent Lifeform#ocs#original characters#Xurkitree#Ultra Beasts#Paradox Pokémon#Past Paradox#Pokemon#pokemon scarlet and violet#Pokemon Scarlet#Pokemon Violet#fakemon#paradox ultra beast#paradox fakemon#art#digital art#digital sketches#colored sketches#The Kiwi Draws

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some fem!chiseharu sketches i did tonight!

I was supposed to finish my other buraikan sketches but as you can see im obsessed with chisei booba so i couldn't stop drawing it (◡ ω ◡)

#last one is very ooc for haru ik. but they must have cuddly moments like this right?#paradox live#buraikan#chiseharu#chisei kuzuryu#haruomi shingu#nyota#sketch#fanart#art commissions open

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kanata from Paradox live

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

can I post this without almost losing my life. who knows

#paradox live#paralive#kenta mikoshiba#goose draws#fun fact chat for some reason if you make a post while you have a community page open it posts to THAT COMMUNITY#WATCH OUT FOR THAT ONE#I was so excited to post this but now it fills me with fear. just take it no explanation needed. I promise it's not miku

23 notes

·

View notes