#the germans were such innovators when it came to lighting

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

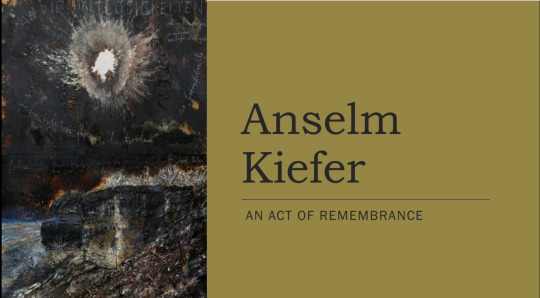

PAINTING ELECTIVE

Brief One- "Portrait"

Anselm Kiefer Powerpoint

Due to some technical difficulties I unfortunatley was not able to present my powerpoint on my selected date. Thankfully Eoin was very understanding and instructed me to simply post my powerpoint onto tumblr.

I chose my artist somewhat randomly, so I was surprised at how much I related to his artistic process, particularily how he is inspired by poetry and incorporates it heavily into his work. I enjoyed researching this artist from various websites and from the books I took out of the library, and this has definitely made me take an interest in this artist outside of this project.

With that, here is my powerpoint. Trigger warning for themes of war and the Holocaust. I wrote a script to read while I presented each slide, so each page will be written under its assigned slide.

Anselm Kiefer is a German painter and sculptor, best known for his works depicting the horrors of the Holocaust. His works often incorporate unconventional materials such as straw, clay, ash lead, and shellac.

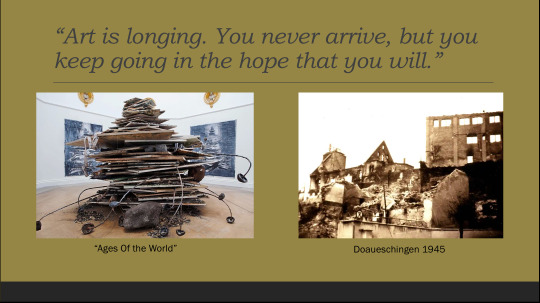

Kiefer was born to a Jewish family amongst ruins on 8 March 1945 in the German town of Donaueschingen. As the town came under intense bombing, Kiefer was born in the cellar of the family home that served as their improvised bomb shelter. In the first few weeks of his life his mother would take him during the day into the surrounding forest to shelter from the bombing. The house next door was blown to pieces.

The ruin next door became Kiefer’s playground. Before the age of six, when his family moved, he would spend his days playing in the rubble, prising loose bricks to build ambitious structures. Hitler’s ruins have haunted his work. Rubble piles up relentlessly in Kiefer’s work, and he deliberately portrays such imagery in his sculptures and paintings.

The past plays an important part in Kiefer’s work. His works are characterised by an unflinching willingness to confront his culture's dark past, and unrealised potential, in works that are often done on a large, confrontational scale well suited to the subjects.

This made him a very controversial artist when he first began his career as Germany and the German people were not ready to face and acknowledge the countries past.

Kiefer often credited the poetry of Paul Celan to have had a key role in developing his interest in Germanys past and the cruelty of the Holocaust, and frequently dedicated paintings to him.

Paul Celan was born in 1920 Romania to a German-speaking Jewish family. His surname was later spelled Ancel, and he eventually adopted the anagram Celan as his pen name.

In 1938 Celan went to Paris to study medicine, but returned to Romania before the outbreak of World War II.

During the war Celan was apprehended by Nazi soldiers and forced to work in labor camp for 18 months, while his parents were deported to a Nazi concentration camp where they were both killed.

After escaping the labor camp, Celan lived in Bucharest and Vienna before settling in Paris. Due to his radical poetic and linguistic innovations, Celan is regarded as one of the most important figures in German language literature the post World War 2 era. His poetry is characterised by a complicated and cryptic style that deviates from typical poetic conventions.

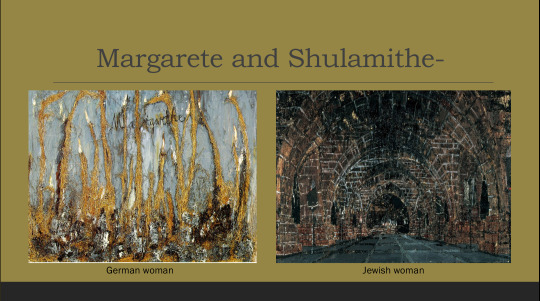

Two of Kiefers his most renowned paintings, Your Golden Hair, Margarete and Sulamith, are drawn directly from Celans most famous poem, 'Death Fugue' or 'Todesfuge'.

Widely read in postwar Germany, the poem is set in a concentration camp and narrated by the Jewish inmates, who suffer under the camps blue eyed commandant. Singing "your golden hair, Margarete/ your ashen hair, Shulamith," they contrast German womanhood, personified by Margarete, and Jewish womanhood personified by Shulamithe.

In Kiefers paintings titled Mararethe and Sulamithe he depicts this contrast visually, depicting Margaret with strands of straw amidst light blue paint, and depicting Shulamithe using dark colours and harsh brush strokes. One artwork out of hundreds that Kiefer has been inspired to create because of Paul Celans poetry.

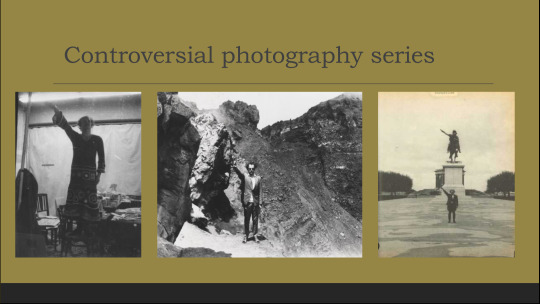

Aswell as painting and sculpting, Kiefer has also dabbled in the world of photography and performance art.

In fact, he was one of the first German artists to address the Nazi crimes in a series of photographs and performances called Occupations and Heroic Symbols. Dressed in his father's Wehrmacht uniform, Kiefer mimicked the Nazi salute in various locations in France, Switzerland and Italy. Naturally these pieces caused much controversy among critics and the general public. The meaning of this photography series was to remind Germans to remember and to acknowledge the loss to their culture from the xenophobia of the Nazi occupation.

At 79 years old Anselm Kiefer is still quite active in the art world and is still sought after by collectors and museums for his captivating artwork. These are some of his most recent works from the past 5 years.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

2020 Party Rentals

Nestled among the green hills of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, lies the quaint town of Fort Washington. It's a place where history whispers through the trees and stories linger in every corner.

Before big wars and famous battles, Fort Washington was just a patch of land where German immigrants like Philip Engard came to start anew. They built homes and carved roads, turning the wilderness into a cozy Engardtown community. Imagine them, with their dreams and determination, shaping the town we know today.

Then came the Revolutionary War, shaking the very ground beneath their feet. General George Washington and his tired soldiers sought refuge after a tough fight. The Emlen House, a grand mansion shaded by ancient trees, became their sanctuary. Can you picture it? Soldiers resting under its roof, their stories echoing through its halls.

But war has a way of leaving its mark, and Fort Washington felt its touch. The Battle of White Marsh unfolded nearby, with brave soldiers fighting for freedom on the town's doorstep. General William Howe surveyed the scene from the top of St. Thomas' Episcopal Church, his eyes fixed on the heart of the American spirit.

Yet, Fort Washington's story isn't just one of battles and bravery. In 1856, tragedy struck when two trains collided near Sandy Run station. Lives were lost, and the town mourned together, forever changed by the sorrow that lingered in the air. But from tragedy, hope emerged. The Fort Washington Office Park rose from the ashes, a bustling hub of activity and innovation. Can you imagine the buzz of excitement as businesses thrived and new opportunities blossomed?

Today, Fort Washington is a place where history dances with modernity. Its streets are alive with the footsteps of those who came before us, their stories woven into the town's fabric. Stroll through its charming neighborhoods, and you'll feel the echoes of the past whispering in the wind.

So come, explore Fort Washington, and discover the tales it has to tell. From the quiet beauty of its parks to the vibrant energy of its streets, there's something here for everyone to enjoy. Let yourself be swept away by the magic of this charming town, where every corner holds a story waiting to be told.

Featured Business:

2020 Party Rentals is your premier choice for top-quality party rental services, offering a wide range of meticulously curated items to enhance any celebration or corporate event. Specializing in transforming venues with elegance and sophistication, we provide everything from plush seating and stylish decor to advanced lighting and sound equipment. Our dedicated team works closely with each client, ensuring a personalized experience and seamless execution from start to finish. Whether planning a fairy-tale wedding, a professional corporate event, or a lively children's party, 2020 Party Rentals is committed to making every occasion memorable with our exceptional service and attention to detail.

Contact: 2020 Party Rentals 240 New York Dr, Fort Washington, PA 19034, United States 4RQ2+R4 Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, USA (267) 323–9699 https://www.2020partyrentals.com/

YouTube Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l4cTOosDOn0

YouTube Playlist: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL-RFPudrXOU7ueQP80cJzr-w1xuKxNahN

Soundcloud: https://soundcloud.com/2020-party-rentals/2020-party-rentals

Soundcloud Playlist: https://soundcloud.com/2020-party-rentals/sets/2020-party-rentals

Medium Post: https://medium.com/@2020partyrentals0/2020-party-rentals-1d09bb16143e

Weebly: https://2020partyrentals.weebly.com/

Tumblr Post: https://2020-party-rentals.tumblr.com/post/753164865457258496/2020-party-rentals

Strikingly: https://2020-party-rentals.mystrikingly.com/

Google MyMaps: https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=1mkAwBQQokUNJGxNcdvOsn9NmuXbcs04

Google Map CID: https://www.google.com/maps?cid=17262173608068392785

Google Site: https://sites.google.com/view/2020-party-rentals/

Wakelet Collection: https://wakelet.com/wake/s1AlxiZ5EnrFxvYhPlc-d

Twitter List: https://x.com/i/lists/1801129791716049299

Twitter Tweets: https://x.com/2020PartyRent/status/1801149678211289390 https://x.com/2020PartyRent/status/1801149877042233346 https://x.com/2020PartyRent/status/1801150296259006938 https://x.com/2020PartyRent/status/1801150411950485876 https://x.com/2020PartyRent/status/1801150639428272456 https://x.com/2020PartyRent/status/1801150874477293713 https://x.com/2020PartyRent/status/1801151006887104627 https://x.com/2020PartyRent/status/1801151131797922071 https://x.com/2020PartyRent/status/1801151250966495256 https://x.com/2020PartyRent/status/1801151362409132520 https://x.com/2020PartyRent/status/1801151519938785413

1 note

·

View note

Photo

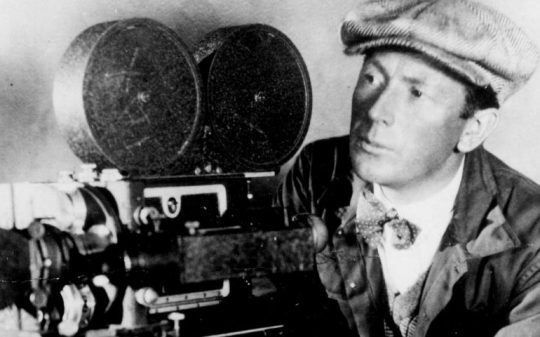

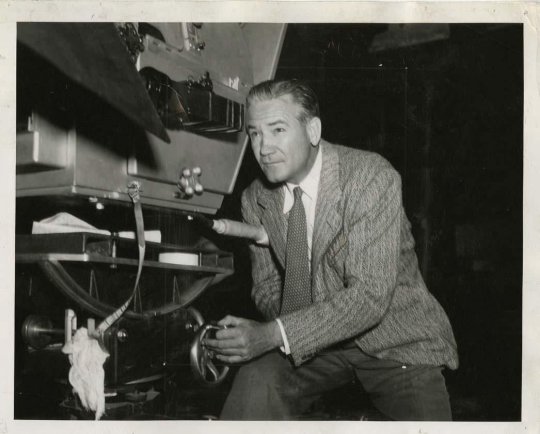

Still capturing the final sequence of Rasputin, Dämon der Frauen (1932).

#conrad veidt#rasputin#rasputin: damon der frauen#weimar cinema#this last scene is probably the best composition of the entire film#beautifully done#the germans were such innovators when it came to lighting

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Östliche Helden | I

Description: Your grin is unabashed when you hear him shouting after you.

Fandom: Hetalia

Pairing: Human!Prussia (Gilbert Beilschmidt)/Reader

Word Count: 4k+

Warning(s): None.

Unsere Freundschaft mit der Sowjet-Union erzwingt den Frieden.

The words are printed on a sun-bleached poster featuring two working class men, one holding the red and gold banner of the Soviet Union, the other with a German flag with three stripes: one black, one red, one yellow.

“Our friendship with the Soviet Union enforces peace,” you whisper to yourself. Staring at the smiling men, trying to read into their expressions, you pick at the peeling corners of the poster, then try to smooth them down.

Behind you, through the window, the sky is aglow with a strong orange and dusty red that fades into pink. You’ve wasted the afternoon in an abandoned factory, with the small, portable radio Gilbert spent a fortune on tuned to a western station. The announcer is saying something about a concert, but you don’t hear him. The sun is setting. The wind drags its fingers through the trees.

Gilbert is sitting in the window, with one leg bent at the knee and propped up on the window sill, the other dangling against the outside of the building. He’s reading a book your brother gave to you about Frederick II, the greatest king of Prussia. You could never sit through it, but Gilbert hasn’t been able to put it down for the last two weeks.

You hum lightly to yourself as a different, tinny voice advertises some household cleaning product, and continue to observe your boyfriend. His brow is furrowed in focus, eyes scanning each page with intent, and his platinum hair is painted red by the blazing sun buzzing behind him. You can’t help but stare at him, and then past him.

The view from the window is framed by Gilbert’s body, and then by large, dark trees that inhale and exhale with the breeze. Behind the trees is a demolished industrial block, rubble left where it fell at the foot of the wall--then past that is the Berlin Wall, itself: nearly four meters tall, two thick, and with various layers of increasingly horrible deterrents running the length of the death strip. It is a grisly sight.

Behind that though, lies true innovation and freedom. Sunlight bounces off the windows of pristine West Berlin as if to say Look! Look at what is here. Look at Germans like you--but not--as they live with American autos, French wine, and Italian designer bags.

The radio announcer’s voice cuts off, and then the guitar chords of the next song fade in, plucking at all of your drifting thoughts and drawing them back tight again. It is a song of freedom, the western stations like playing it because they know it can be heard even behind the Iron Curtain. You close your eyes and let the music take you away, swaying in rhythm.

“I, I will be king,

And you, you will be queen.

Though nothing will drive them away,

We can beat them, just for one day,

We can be heroes, just for one day.”

You never listen to western radio in your house. It is silent except for when your father listens to a concert performance, or when your brother used to practice piano in the sitting room. Besides, your mother is frighteningly aware of the ears in the walls, and your father makes a point of socialising with people he suspects of being connected to the Stasi--probably in hopes of being recruited. It’s why you’ve been left alone, even after your Onkel took bolt cutters to the chain-link border fence at the Austrian-Hungarian border.

You hear your shoes scrape on the floor as you step side to side, getting more into the song, nodding your head and then you hear Gilbert snicker under his breath. You peak your eyes open to find him watching you. His book is closed, resting on the window sill, and he’s now sitting with his legs inside the building. You stop dancing, laugh, but the music continues on without you, the sound like an afterthought calling to you.

Gilbert leans forward, watching you with steady eyes, then pushes off the window sill to stand. He tilts his head for a moment, like he’s appraising the music, then begins to snap his fingers on beat, tapping his foot and bobbing his head.

You join him, shimmying, waggling your eyebrows and he snorts, then gets more into the song, shaking his hips and dramatically reaching up towards the ceiling, then closing his fist and dragging it down in front of him like the disco stars on TV.

Trying to upstage him, you click your heels together and start to do the twist, but the song’s chords are drawn out, and so the shuffling you’re doing is more for comedic effect than anything else.

You pause when you’re closest to the ground, then jerk your head up to catch Gilbert’s eyes in challenge. He lets out a breathy laugh, then changes tactics. Not one to be outdone, he throws his arms above his head and begins thrusting his hips in time with the drums, while training his expression to remain serious, smoldering, almost. You laugh.

“And you, you can be mean,

And I, I'll drink all the time,”

“ 'Cause we're lovers, and that is a fact,” he mouths the words dramatically, then winks and blows you a kiss, making you snicker again. “Yes, we're lovers, and that is that.”

Still thrusting his hips, he begins to make little hops towards you, dust from the floor kicking up around his feet. Grinning, you rise back up to both feet and meet him halfway, swinging your arms and stepping in time with the beat.

When you finally meet each other, he reaches forward, smooshing your face between his hands, then ducks down to plant a silly, solid kiss to your lips. Your teeth clack, your nose presses hard into his cheek, and he laughs into your mouth, then quiets when you kiss him back.

The music becomes less of something you hear, and more of something you feel thrumming in your heart, thrumming in Gilbert’s as it beats beneath your palm, and thrumming in the way you both sway side to side, caught up in the moment.

“Though nothing will keep us together,

We can steal time, just for one day.”

Gilbert sucks in a breath through his nose, kissing you earnestly, sincerely now, then pulls back slowly. His hands are cupping your face, thumb gently rubbing your cheek, and you’re humbled by the expression on his face, still painted in increasingly soft shades of red-pink. Affection blooms in your chest, warm like a candle, and spreads until you forget about the bite of the approaching evening. Almost overwhelmed, you pull his arms around you and lay your forehead on his shoulder, watching the West as the sun dips farther towards the horizon, as the sky begins to bleed the same red, the same damn Sowjetisch Rot, that paints their bloody flag.

You can hear him smiling in the way he breathes, feel it in the way he settles the weight of his arm over your shoulders and presses his face into your hair. You forget about school, you forget about the stress of your parents’ disapproval of Gilbert, of you, you forget about the future and you forget about the gottverdammte West. “Lieb’ dich, Liebchen,” he whispers into your hair.

The intimacy scares you. You think about pinching the soft fat on his stomach and twisting like you would a bottlecap to relieve some of the carbonated tension that’s filled the space, the tender moment buzzing around the two of you, surrounding you with its quiet intensity. The sudden thought makes you laugh, and you settle farther into his embrace instead, letting yourself sink into this feeling despite the fear for once. “Lieb’ dich, doch. You’re my favourite, you know.”

You somehow both see it coming and are taken by complete surprise when he pinches the meat of your arm and twists enough for it to smart.

“Ow-a!” You shove him off you and he stumbles back over a piece of broken furniture, snickering. You huff, dust your pants off, and try to glare at him, but you can’t bring yourself to be all that annoyed. Afterall, you chose this place and you chose him.

And the sun continues to set.

***

The morning is grey outside the apartment. It’s still early enough for the streetlamps to be on, and from under your bedroom door, you can tell the hallway light is on as well. You hear the muted clamor of breakfast coming from the kitchen, and your father coughs.

You smooth your hair back in the vanity one more time, double-checking your appearance, then grab your backpack and head out into the hall.

“You came home late last night,” your father comments from the dinner table as soon as you enter the sitting room. In front of him sits an empty plate, a mug of coffee and a half-empty glass of orange juice.

You set your bag on the table and head into the kitchen. “I know.”

“You shouldn’t ride your bike at night,” he calls after you.

“I know.”

Your mother is by the stove, wearing her sunflower print apron and black slippers. The room smells like breakfast sausage. She has her back turned to you and when you approach, she spins on her heel and pushes a full plate into your empty hands before you can do anything else.

“Ah--Guten Morgen, Muti. Vielen--” you’re caught half-way through a yawn--“Dank.”

“Good Morning, Liebling. Eat up.”

You smile and return to the table. Your father is waiting, but says nothing. He continues to say nothing as the clouds are pushed across the sky and the food on your plate disappears one bite at a time.

Eventually, he grows tired of the silence. He takes a long sip of his coffee, then says, “You were out with that boy, weren’t you.” It is not a question.

“You know his name,” you say mildly as you push your chair back and stand to take your plate into the kitchen. Your mother appears at your elbow and collects it for you instead. Without another excuse, you pull your bag across the table to check if you have everything you’ll need for school.

Still sitting where he is, your father asks, “When are you going to break up with him?”

“I’m not.”

He gives you a hard look. You pull your arms through the straps of your bag. “Is there really no one else for you?”

“I’m going to class now.”

He sighs, seemingly giving up on the conversation. “You have work after, right?”

“Right.”

Another sigh. “Alright. Be safe. See you soon.”

He drains the last of his coffee. Your mother kisses you on the cheek and tells you to have a good day as well.

“You, too. Lieb’ dich.” You turn to your father, “Bye, Vati. See you soon.”

***

Childhoods are not made equal, and the law of even-stevens is not something adults seem overly interested in. You first learned this in year three, when you were dropped off by your mother to play with a friend who lived in an apartment the size of your living room. Her bed was folded up neatly under the coffee table and the bathroom was two floors below hers. When you explained all this to your parents, they never allowed you back.

The second time you learned that adults were not as worried about being fair as they pretended to be was at Gilbert’s house, when the two of you could only play cards on his bed because his newborn brother was sleeping and anything else would have woken him. His mother made you sandwiches and when you asked about her lunch, she said she wasn’t hungry, then ate the discarded crust off your bread.

The third was when Gilbert was visiting your house, and switched on your family’s brand-new color television set. He casually flipped through the channels until he found one you’d never seen before, and you watched with confusion as image after image of the glamorous, rich, free West Germany flashed on the screen--something you’d never seen before, something he thought of as common knowledge, and something that made you begin to question what else was hidden from you. Your father catching the two of you soaking in the perverse capitalist propaganda movie ‘Grease’ was the beginning of his long-lasting feud with Your-Best-Friend-Gilbert.

The list goes on and on, your eyes not so much being opened to a single dawning realisation--but rather that realisation was inevitable, a full picture fed to you piece by piece each time you bore witness to some other lie fed to East Germans, who chew and chew and swallow because they’re so starved of everything else.

This is what you’re thinking about as Kristian goes on explaining Nietzsche to you. It’s terribly pretentious, he’s terribly pretentious, and so, regretfully, terribly, are you.

“I thought it was interesting. Didn’t you as well? What Herr Ullman was saying about the difference between Nietzsche’s master and slave morality--obviously we are the strong masters. We must not be pitied.”

Kristian is a person who never for a second thinks for, or critically, of himself. He is in your Philosophy lecture, your father knows his, and he has never once wanted for anything. The urge to fidget overcomes you, and so you grip the underside of the shop-counter, and rock back and forth on your heels to stop the annoyance from crawling up your arms.

“Y/N?”

“Hmm?”

“I asked what you thought of how Nietzsche’s ideas could be applied to our politics now.”

“Oh, well--” you pause for a moment to think about how much of yourself you’re willing to put into this conversation-- “It’s interesting how some people claim to be masters--”

“Of course!” he interrupts. “You’re brilliant--because in reality, they are not. Take here, in the DDR, for example. The majority of the working class think of themselves as masters, while holding slave moralities,” he finishes for you, incorrectly. You bite your tongue.

Sometimes, Kristian is enjoyable to be around because it’s like a game, to have a conversation with someone who refuses to hear anything you say. You like to test the limits of his perception of you and see just how far he’ll go to rationalise whatever you say so that in his head, you agree with him.

Recently though, it’s become clear that he has an interest in you that is just a little more than friendly, and casually letting him down is becoming a problem because he refuses to take a hint. Now, at Uni, every time you turn a corner, he’s there to follow you to your next class, and his forwardness is beginning to unroot whatever amusement you used to feel around him.

Kristian is another item to add to the growing list of reasons you’d rather be wasting your day watching the clouds go by than be at Uni--or be trapped behind the counter of the Apotheke you work at, begging the powers that be that Kristian leaves before your shift is up, otherwise he might get it in his head that you have free time to spend with him.

Time moves in slow motion as Kristian stands in front of the register and continues to talk. No one has come in after him so you don’t have any excuses to leave the conversation. You feel awkward, like being alone with him is a mistake that you can’t escape from because the owner of the Apotheke is out taking his lunch in the park across the street.

“We think so alike, you and I…” Kristian trails off, and then he fiddles with the soda he bought ten minutes ago, and looks away, embarrassed. “Hey,” he begins again, and at the tone of his voice, your stomach drops. Before he was just dropping hints or loosely suggesting the idea of going on a date, but this is a confrontation that you’re not prepared to deal with. “I was wondering if sometime you’d like to--”

The bell above the door trills, and you jump into action. “Ah--Willkommen! How can I help you today?” you speak loud enough to smother the end of Kristian’s question.

“Liebe,” you hear the customer say, and immediately you know that it is Gilbert. What timing! He’d taken the morning off to go see Ludy’s school play and mentioned that he might be able to swing by after running a few errands for his mother. “You’ll never guess what happened! Oh! Kristian--” he pauses-- “Hallo. Anyways, I was riding my bike down Schulstrasse after the play and I--”

“We were talking,” Kristian interrupts, whatever boyish shyness he’d had evaporating as he crosses his arms and turns to face Gilbert, almost puffing out his chest like a bird.

Gilbert gives him a funny look, then asks, “yea?” He looks to you for confirmation.

You shoot Gilbert a wobbly, unconfident smile and gesture to Kristian with wide eyes. He furrows his brow in confusion, then looks around and realizes you’re alone in the shop. He then turns his full attention to Kristian and, with fake pleasantness, asks, “how are your classes, Kristian?”

Kristian rocks back on his heels and unfolds his arm at the sudden question. “Good, I guess…” He shoots a look back at you, and you pretend to be seriously inspecting the cash register for defects. You pop open the drawer and feign counting the Deutsche Marks.

“Good!” Gilbert presses forward. “I hear Herr Ullman is a hardhead.”

“A bit,” Kristian replies, then turns his back to Gilbert and tries one last time to get your attention. “Y/N--”

At the sound of your name leaving Kristian’s mouth, Gilbert slides an arm on the counter between you and Kristian, who bites off the rest of his response and drops all pretenses to glare at Gilbert.

“Interesting,” Gilbert says flatly, “Sowieso, Schatz, when does Herr Friedman get back from his lunch?”

Kristian doesn’t wait for your response. He just huffs, snatches his drink off the counter, and stalks out of the Apotheke. The bell trills as he pulls the door open, then lets it slam shut in its frame.

“Tschussi!” Gilbert calls after him, and you really should reprimand him for that last, unnecessary taunt, but the amount of relief you feel now that Kristian is gone is ridiculous, and so you reach over the counter to grip his forearm with both hands, grinning up at him.

“Don’t be so mean,” you say half-heartedly.

Gilbert cocks his head to the side. “Then he should take a hint and listen when you tell him no.”

His genuine response surprises you when it shouldn’t. Afterall, you know what sort of man he is; you’ve known for years. It’s what kindled your crush on him in secondary school, the year before he went off for his apprenticeship in that garage he still dreams of, it’s what fanned the flames when he returned for his year of mandatory service, and it’s what stokes the love even now. “Thank you.”

“Why?” He grins. “Did you think it was awesomely sexy when I made him back off--”

You choke on a laugh, cheeks warm. “Oh, shut it! You ruin everything!”

He laughs like a witch’s cackle, and you pretend to be put out, then ask,“what were you trying to tell me about before?”

“Oh!” He straightens. “Remember that pigeon from school?”

***

“Gib can talk to birds, you know,” Ludwig says factually. ‘Gib’ is his childhood nickname for Gilbert. You nearly trip at the sudden change in topic.

“See!” Gilbert throws a hand out to gesture at Ludwig, vindicated. His other hand holds his bike steady as the three of you continue to walk down the sidewalk.

You groan. “I swear to god, the pigeon does not know you!”

“Yes he does! I’ve named him--”

“Don’t remind me--”

“His name is Gilbird.” Gilbert proudly sticks his nose up, and you resign yourself to pushing your bike in silence. You’ve had this same dispute since school. Gilbert is convinced that since he saved a pigeon from a hungry alleycat one time, it now owes him some sort of life debt, or at least he thinks the pigeon thinks that.

“I think it’s clever,” Ludwig says quietly, squeezing the straps of his backpack tighter in his hands as he continues to walk beside you and Gilbert, who are pushing your bikes to keep pace with him.

“Ludy,” you stage whisper just loud enough so Gilbert can still hear you, like you’re sharing some grave secret, “he’s been saying the same thing since year five. I don’t even think it’s the same bird!”

“Schatz!” Gilbert cries, outraged.

You roll your eyes dramatically. “C’mon,” you say, and goad Ludwig into jogging ahead of Gilbert with you. As much as Ludwig hero-worships his elder brother, he also can’t resist the temptation of teasing him, especially when you offer him the upper hand.

“Ah!” Gilbert exclaims once he realizes your plan. “Hey!” When you pass him, you stick your foot out to unhinge his kickstand, making him stumble over his bike.

“I’m too awesome to not be telling the truth!” he calls after you. “You were there! Hey!”

Ludwig laughs out loud, and so you turn around as well, only to see Gilbert struggling to untangle his handlebars from a bush. “Quickly!”

You swing your leg over the seat of your bike, then usher Ludwig into the basket fixed over the rear wheel. It’s not meant for a person and is an uncomfortable fit, even for little Ludy, but the two of you manage.

“That’s cheating!” Gilbert calls out sorely, still a little ways behind the two of you, though you know he’ll catch up in no time. Ludwig giggles right in your ear, and then you push off the concrete and begin pedaling down the sidewalk.

“Look at him, all the way back there,” Ludwig teases.

You can’t turn around to bask in your victory, you’re afraid to lose balance and throw Ludwig off the bike. “Is he still stuck?”

“Yes--No! He’s just freed himself! Schneller! Faster!” Ludwig leans more of his weight forward, onto your back, and you laugh breathlessly, then pedal harder. You take the curb hard, pushing yourself off the seat to absorb the shock of your front wheel dropping onto the asphalt, then the rear wheel squeaks in protest under Ludwig’s added weight.

From around the wide bend of the road, you see the young trees that are planted in front of Gilbert and Ludwig’s Plattenbau, the tall apartment building looming over the road like a victory line. Your thighs begin to burn under the exercise. You pant, and Ludwig squeezes your shoulders tighter. “Oh no!” he cries.

Then it’s over. “Ha ha!” Gilbert tuts victoriously as he flies past the two of you, legs stuck out in a silly pose as his gears rapidly click.

“Aw! That’s no fair, Gib! Y/N has me on the bike, too!” Ludwig defends you from over your shoulder.

“You should have thought about that before you two unawesomely conspired to push me into that bush!”

“We didn’t push you! You tripped!” You slow to a stop in front of the side entrance next to Gilbert, and wobble under yours and Ludwig’s combined weight. Gilbert drops his bike in the grass and moves to help Ludwig down from his perch on the basket.

Gilbert rolls his eyes. “Same thing.” He sets Ludwig on the ground, then adds with fake scorn, “cheaters.”

Ludwig laughs, and you inspect your backpack, which Ludwig had been crouched on for the duration of the short ride. “Do you go to work now, Gib?” he asks.

“Ja. But I’ll be back like normal.” You look up in time to see Gilbert messing with Ludwig’s hair. You feel a pang of jealousy, thinking of your own brothers.

“Okay.” Ludwig walks to the entrance, then pulls open the door. “See you later!”

“Bye!”

“Bye, Luddy!”

For a moment, the two of you just breathe the filthy air. This part of town always stinks like a car’s exhaust pipe. Then Gilbert looks back at you. “Race you to your house?”

You eye him critically for a moment, then turn your bike around and begin pedaling as fast as you can without so much as waiting for a fair start.

Your grin is unabashed when you hear him shouting after you.

***

Translations:

Unsere Freundschaft mit der Sowjet-Union erzwingt den Frieden. Our friendship with the Soviet Union enforces peace. From this 1979 propaganda poster.

Deutsche Demokratische Republik. DDR. German Democratic Republic. Abbreviated ‘GDR’ in english. The official name of ‘East Germany’.

Onkel. Uncle.

Sowjetisch Rot. Soviet Red, referring to the Soviet Union’s flag colour.

Gottverdammte. Goddamn (f).

Lieb’ dich. Love you (slang, not proper grammar).

Liebchen. Sweetheart, lovely (noun). Term of endearment. (Literally: little love, love I am fond of, the -chen is diminutive and cute).

Doch. Too, totally, all the same, nevertheless. This is a ridiculous german word.

O-Saft. Orange Juice (slang).

Guten Morgen. Good morning

Muti. Mom.

Vielen Dank. Thank you very much.

Liebling. See Liebchen, though this is a more common version.

Vati. Dad.

Apotheke. Drug store, pharmacy.

Willkommen. Welcome.

Liebe. Love.

Hallo. Hello, Hi.

Deutsche Marks. Mark der DDR. Currency of the GDR.

Sowieso. Anyways.

Schatz. Babe, baby. Term of endearment. (Literally: Treasure)

Tschussi. Bye-bye, toodles. Cute with children, though usually used sarcastically by adults, especially men. (Gilbert is making fun of Kristian here)

Schneller! Faster!

Plattenbau. A cheap style of building made from prefabricated concrete slabs common in the GDR. (Literally: Panel building)

Masterlist | Posting Schedule

#hetalia#aph#aph prussia#hetalia x reader#aph prussia x reader#aph prussia imagine#hetalia imagine#aph imagine#aph x reader

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Goodness, HUGH HOWARD has arrived in London. HE is 30, of the EFFINGHAM HOWARDS. Though they are RETURNED to the Season, we can only describe them as PASSIONATE and WITTY, dear reader. Accompanied by his CAT WELLINGTON , they have settled in and are accepting social calls. But be warned: they are known for their CAPRICIOUS BEHAVIOUR. (Kate, 25, She/her, EST)

THE BASICS

Name: Hugh Thomas James Howard

Nicknames: Hughie - His mother

Meaning of her name: German: Meaning Soul, mind & Intellect.

Age: 30

Birthday: January 8th, 1770

Relationship Status: Unmarried

Sexuality: Biromantic/pansexual

Height: 5"9

Physical features: Thick brown beard, piercing blue eyes, a deep tan.

A BRIEF LOOK

Alignment: True Neutral

MBTI: ENFJ - The Protagonist

Ennegram:

Hobbies: Writing, going on long walks, making candles from scratch with essential herbs.

Favourite Food: A heart roast made by his mother

Inspiration: Collin Bridgerton, George Whickham, Heathcliff, William Shakespeare.

BIOGRAPHY

Hugh was born the one and only surviving child of Thomas Howard and Olivia Howard (Nee Jamison). They were the ‘poor’ relation, and that fact alone was something that was driven into Hugh from a young age. Though their family name held greatness, he was nothing but a paupers son, and though there was enough money to send him to school, there was not much else in the way of funds. Hugh never had a close relationship with his father, who he found to be too ‘head in the clouds’ when it came to ideas of what grandeur they could live in. His father was always planning, attempting to move onto the newest innovation to make some money.

When Hugh was 6, he awoke one morning to his parents arguing. His father was leaving for the American Frontier and leaving his wife and son to struggle at home. That was a turning point in Hugh’s life, as he watched his mother’s world shatter around her.

He stayed in school until they could no longer afford it, and quickly went to work.

Hugh however, was a man of the world born in a working class mans body. He was not one for hard labour, though he would do it to put food on the table. His true passion, the one that kept him up at all hours of the night, and had him falling asleep on the job was poetry. Poetry was his solace, and the one thing perhaps, that he was talented at.

The fact that as he grew, his devotion to spoken word began to expand, and his lack of wanting to work diminished caused a war within Hugh for some time. He had turned into a version of his father. The one who he always criticized for leaving his family.

It wasn’t until he was 22 that he got his ‘proverbial’ big break. Somehow, it had come to light that he was talented with words and it became a sort of side business for Hugh to write sonnets and love poems for the men he met at a local pub.

Once he started making money off of his work, going to a labour intensive job was not something that he desired to do, and since he was charging enough for his poems, he realized that he could live a suitable life on his own. The only problem was his mother.

It was not the best of conversations, bringing up the fact that he wanted to leave, just as his father had, on search for himself. Yet somehow, it seemed his mother had expected it, and had decided to move from the tiny home they shared, and in with her sister. It allowed Hugh to go off and explore the world, make himself happy, and enabled him to send money home for his mother every once in awhile, knowing that she was being well taken care of.

His adventures and travels found him in Istanbul, wandering spice markets and staying out late with all sorts of new friends. He wrote about the Black Sea, his adventures in cramped caravans and even wrote about love he found - but never dared to publish it. His adventures ranged from magnificent, to dangerous and to downright sordid. Though, he did not write of his sordid affairs.

Years passed, and while Hugh longed to continue adventuring, a letter from his mother called him back home. At the ripe age of 29, his mother had beckoned him back, urging him to finally settle and make a name for himself in England.

He had missed his mother, and despite wishing to continue his travels, knew that she had a point. He owed it to her to come back home, as his father never had.

There were times when Hugh wondered if his father was still alive. Sitting on a porch somewhere with a new family and name. With riches just sitting there that he could have shared with Hugh and his mother. Thoughts like that seemed to ruin his day, so Hugh deigned not allow such horrid thoughts to creep in.

Landing on English soil was a bittersweet thing. He had seemed to miss the broody atmosphere that England possessed, and despite looking out of place thanks to his tan skin and lightened hair,

Now back ‘home; his mother has begged him to present himself to his ‘distant’ cousin, the Earl of Effingham as his one heir - at least until the young wife he has produces a son.

It is a tricky business, but Hugh has come with a mission, and a promise to his mother.

YO GUYS! Hugh’s connections can be found HERE i’m so excited to bring him to you all!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

hello my children it is time for

Bad Blood

Chapter II: Still There

Bertrum completed his evening ritual with a final splash of warm water to rinse the soap from his face and a gentle drying off with a neatly folded washcloth. He shook out his hair and used a damp thumb and forefinger to tidy his mustache as he scrutinized his reflection. If he was going to face Mr. Drew in the coming days, he was going to do it presentably.

“Ya ain’t goin’ on a date, Bertrum, what’re you fussing over your appearance for?” Lacie barked from the adjacent bedroom. “C’mon, it’s late.” Her eyes were rolled behind the book she was reading as she awaited him in bed.

With an audible sigh, Bertrum returned to her side. “Elegance starts with proper hygiene, and you know how highly I value elegance.” As he plucked his nightcap from the dresser and sat upon the edge of the bed to put it on, he couldn’t help but quip, “…and that is why you’re here.” Had Lacie been watching, she would have caught sight of a soft smirk tugging at the corner of his mouth.

“Listen to yerself bein’ all sappy.” Lacie set her book upon the bedside table as she chuckled. “Cute.”, she murmured as she sank deeper under the duvet.

“I’m not lying, love.” Bertrum laid down beside her and gestured with one hand as though to silently ask, ‘May I hold you?’, to which Lacie nodded in approval. Bertrum responded by wrapping a husky arm around the small of her back and tenderly pulling her over. A quick tug on the lamp’s pull chain allowed comforting darkness to fall over the room.

With one hand resting on Bertrum’s forearm, the other held snug in his large hand and her head tucked neatly under his chin, Lacie asked, out of pure curiosity, “…so what’s we doin’ tomorrow, exactly?”

A sharp tightening of Bertrum’s chest made her regret the query. “Would you prefer the long answer or the short one?”

“Whichever’s gonna upset ya less.”

“They’re both equally infuriating.”

“…aight. In that case, sleep first, be mad later.”

Bertrum agreed with a quiet grunt before giving Lacie a nuzzle and kiss on the neck in lieu of “good night”.

Lacie’s near-silent breathing was the only thing that kept Bertrum grounded in reality. By the time he resigned himself to a sleepless night nearly an hour later, she had buried her face in his nightgown, draped one arm across his stomach and the hand that previously occupied his now empty palm rested at her side. She was clearly at peace beside him.

It made him jealous.

His envy was only tempered by the sudden desire to keep her uninvolved while he settled his score with Joey. This was, after all, his own axe to grind. Bertrum was not about to admit his insecurity to himself, but a nagging thought repeated in his mind.

‘I’m plenty capable of standing up to the man, but I need someone in my corner. Someone to prove that I own what he stole credit for, to back me up when I show him my paten—‘

Startled by the revelation, Bertrum nearly leapt from his bed.

He had proof, and it would save Lacie the trip.

Waking up in the middle of the night was not common for Lacie, and if she did, it meant something was amiss. Bertrum hogging the blankets was her first thought, but that night, when she rolled over to reclaim the pilfered bedding, she found her partner missing.

“…Bertrum?”

Had it not been for his outburst that evening, she wouldn’t have thought much of his disappearance. An occasional midnight snack or pot of tea was not unusual, but he was rarely gone for long.

No noise came from the kitchen. Bertrum was a plenty polite man but he certainly was not a quiet one. Soft humming to himself as he waited for the kettle to boil, clinking utensils as he stirred his tea and the sharp tap of ceramic against ceramic as he raided one of his many biscuit tins were all sounds that were normally present during his nighttime visits to the kitchen, but every one was absent. When a full twenty minutes passed without his return, Lacie grew increasingly concerned, and the silence only made it worse.

She slid off the bed, draped on her bathrobe and went searching for him.

From the study, Bertrum silently and repeatedly thanked Lacie for leaving the crossword on the side table. By chance, the part of it that listed several of the attractions had been on the reverse of the very article that prompted his fit of rage that evening, and as much as the words still made his blood boil, he needed it.

Every ride and every innovation that was mentioned in that scrap of newspaper had a story. Hours upon hours of research, calculations and drafting. Once the technical parts had been perfected, Bertrum bestowed his favorite part, the creative and elaborate embellishments, upon his creations. A massive locked filing cabinet kept the attractions’ stories safe. The documentation that accompanied inventions that took a firm hold in the amusement park industry included their respective patents.

Those were what Bertrum was after.

For nearly half an hour, Bertrum leafed through his filing cabinet, using the article to guide his selections. His prized rides. The side-friction roller coaster, made in collaboration with a late German ride mechanic with whom he’d shared the patent. His inverted steel hairpin coaster; he had never been one for wooden coasters, their frailty did not allow for the wild drops or gravitational forces that had become increasingly popular among younger patrons. After fetching the ones the article contained, Bertrum started pulling papers associated with rides that had become famous. It hadn’t been mentioned in the article, but the strange contraption he’d invented, lovingly called the Whipper-Will-O, had its patent added to the expanding stack in his briefcase. It had always been one of his personal favorites. After all, the more disorienting, the better.

Bertrum had just entered the final stretch of his search when a knock at the door jarred him from his reminiscing and angry brooding. “Bertrum, what the hell’re you doin’ at this hour?!”

“I couldn’t sleep.”

“…so yer… packin’.”

“Yes. Go back to bed, love—I’ll be there once I’m done getting these patents together.” Bertrum hadn’t turned his head to acknowledge her at all.

Bertrum had at some point changed from his nightgown to a collared shirt, neat slacks and, though the light of the desk lamp by which he worked was dim, she was pretty sure she could see his suspenders hanging from his waist. Clearly he didn’t intend to return to bed. “Big guy, just…” She sighed. “Come back t’bed. It’s three AM and I ain’t gonna coddle ya if you’re cranky in the morning.”

“Just give me some time.”

An irritated Lacie tucked her finger into the back of his collar and tugged. “You can do this after we hit the bookin’ office.”

Bertrum answered her with a grunt as he slid out of his chair. “Fine, fine.”

Attempting to sleep was more taxing than Bertrum expected. His mind was full of a sick fog that demanded his attention and blocked his path to rest. Too exhausted from fighting it, he let the haze take over.

‘He used to call you in at random. It began innocently enough, just… simple requests. You could handle those, they were nothing new. Clients made them all the time. But those requests turned into demands. Obnoxious demands. You should have listened to Mr. Connor when he warned you that Mr. Drew was unreasonable. You should have known, Bertrum. You should have bloody known.’

‘You could have left. On your own terms. The contract he’d written was a hastily scrawled mess of a page. All it said was that you’d do it, nothing more, and through that inebriated haze you could barely think twice about whether to put down your name… your untarnished name.’

The insecurity made him sick.

‘…No. Stop it. This was not your fault. That sleaze, he… he tricked you. He took advantage of you. You’re a professional, Piedmont. He was not. It showed that day. That day he called you into his office and threw you out.’

‘That memo you sent Joey was supposed to put out any fire that was smoldering between you. He overreacted. All it said was to stop taking and not returning your blueprints. Nothing else. So what if you raised your voice?! He started this! He was in your office after hours. He was mucking about in your proprietary work, and you called him out. You had every right! His firing you over an accusation? That was his fault.’

‘Tomorrow… will be better.’

Bertrum finally was able to talk himself down.

‘You’ll take back your plans by force, if you must. You cannot let Mr. Drew keep what isn’t his, and you certainly cannot let him implement anything more of yours under his own name.’

#batim#bendy#bendy and the ink machine#bertrum piedmont#joey drew#thomas connor#lacie benton#headcanon#bertrum x lacie#lacie x bertrum#batim au#batim bad blood au#fanfic#the giandark writes#is this a disaster idk bertrum throwing a mental tantrum is hilarious#i feel like i rambled#but bert is very babbly so#swearing tw

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Influential Directors of the Silent Film Era

Upon hearing that I am a fan of silent era film, people will ask if I have a favorite actor or movie from the time period. However, when I am asked about my favorites from other fans of silent film, it tends to involve my favorite director. This is because silent film actors had to over gesticulate and performed in an unrealistic way and could not use their tone or words to convey emotion. The directors also did not have a way to review as they shot and would have to use editing skills and strategic cover shots to make sure that everything was done properly and come out the way they imagined it. It was up to the director to be creative and they were forced to be innovative and create ways to convey their vision. Luckily for many average or poor directors of the time, audiences were easily impressed. However, today's more demanding and sophisticated audiences can look back at some of the genius behind the films of silent era Hollywood.

Alice Guy-Blache: Matrimony's Speed Limit (1913) and The Fairy of the Cabbages (1896)

Art director of the film studio The Solax Company, the largest pre-Hollywood movie studio, and camera operator for the France based Gaumont Studio headed up by Louis Lemiere, this woman was a director before any kind of gender expectations were even established. She was a pioneer of the use of audio recordings in conjunction with images and the first filmmaker to systematically develop narrative filming. Guy-Blanche didn't just record an image but used editing and juxtaposition to reveal a story behind the moving pictures. In 1914, when Hollywood studios hired almost exclusively upper class white men as directors, she famously said that there was nothing involved in the staging of a movie that a woman could not do just as easily as a man.

Charlie Chaplin: The Kid (1921), The Gold Rush (1923), City Lights (1931), Modern Times (1936), and The Great Dictator (1940)

It is unfortunate that many people today think of Chaplin as silly or for screwball comedy when, in fact, he was a great satirist of the time. He created his comedy through the eyes of the lower economic class that suffered indignities over which they had no control. He traversed the world as his "Tramp" character who found his fortune by being amiable and lucky. The idea that a good attitude and a turn of luck could result in happiness was all that many Americans had during the World Wars and the Great Depression. He played the part of the sad clown and he was eventually kicked out of the country for poking fun at American society. Today he is beloved for his work, but he was more infamous than famous during a large part of his life.

Buster Keaton: Sherlock Jr. (1924), The General (1926), and The Cameraman (1928).

That man that performed the most dangerous of stunts with a deadpan expression, Buster Keaton was a great actor, athlete, stuntman, writer, producer, and director. It is amazing that you could get so much emotion out of a silent actor who does not emote, but Keaton managed to do it. He was also never afraid to go big, often putting his own well being at risk to capture a good shot. Not as well known for his cinematography or editing as many of the other directors of the time, he instead captured performances that were amazing no matter how they were filmed. Famous stunts include the side of a house falling down around him, standing on the front of a moving train, sitting on the side rail of a moving train, and grabbing on to a speeding car with one hand to hitch a ride. If you like films by Jackie Chan, know that he models his films after the work of Buster Keaton: high action and high comedy.

Cecil B. Demille: The Cheat (1915), Male and Female (1919), and The Ten Commandments (1923)

Known as the father of the Hollywood motion picture industry, Demille was the first director to make a real box office hit. He is likely best known for making The Ten Commandments in 1923 and then remaking it again in 1956. If not that, he was also known for his scandalous dramas that depicted women in the nude. This was pre-Code silent film so the rules about what could be shown had not been established. Demille made 30 large production successful films in the silent era and was the most famous director of the time which gave him a lot of freedom. His trademarks were Roman orgies, battles with large wild animals, and large bath scenes. His films are not what most modern film watchers think of when they are considering silent films. That famous quote from the movie Sunset Boulevard in 1950 in which the fading silent actress says "All right, Mr. Demille. I'm ready for my close-up," is referring to this director.

D.W. Griffith: Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916)

Griffith started making films in 1908 and put out just about everything that he recorded. He made 482 films between 1908 and 1914, although most of these were shorts. His most famous film today is absolutely Birth of a Nation and it is one of the most outlandishly racist films of the time. The depiction of black Americans as evil and the Klu Klux Klan as heroes who are protecting the nation didn't even really go over well at that time. Some believe that his follow up the next year called Intolerance was an apology, but the film actually addresses religious and class intolerance and avoids the topic of racism. At the time, Griffith films were known for the massive sets and casts of thousands of extras, but today he is known for his racist social commentary.

Sergei Eisenstein: Battleship Potemkin (1925)

This eccentric Russian director was a pioneer of film theory and the use of montage to show the passage of time. His reputation at the time would probably be similar to Tim Burton or maybe David Lynch. He had a very specific strange style that made his films different from any others. The film Battleship Potemkin is considered to be one of the best movies of all time as rated by Sight and Sound, and generally considered as a great experimental film that found fame in Hollywood as well as Russia.

F.W. Murnau: Nosferatu (1922), Faust (1926), and Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927)

I think that most people would know the bald-headed long-nailed vampire Nosferatu that was a silent era phenomena. It was so iconic that the German film studio that produced the movie was sued by the estate of Bram Stoker and had to close. Faust was his last big budget German film and has an iconic shot of the demon Mephisto raining plague down on a town that was the inspiration for the Demon Mountain in Fantasia (1940). Also, Sunrise is considered one of the best movies of all time by the AFI and by Sight and Sound as well as my favorite silent film. Fun facts: 1) more of Murnau's films have been lost then are still watchable and 2) he died in a car wreck at only 40 when he hired a car to drive up the California coast and the driver was only 14.

Erich von Stroheim: Greed (1924)

Maker of very strange German Expressionist films, Stroheim films are often listed as Horror or Mystery even though he considered himself a dramatic film maker. His most famous movie Greed was supposed to be amazing with an 8 hour run time but it was cut drastically to the point that it makes no sense and was both critically and publicly panned when an extremely abridged version was released in the U.S. Over half the film was lost and a complete version no longer exists. Besides this film, Stroheim was even better known for being the butler in the film Sunset Boulevard as a former director who retired to be with an aging silent film star. He also made a movie called Between Two Women (1937) that told the story of a female burn victim that was inspired by the story of his wife being burned in an explosion in a shop on the actual Sunset Boulevard.

Victor Fleming: The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Gone With the Wind (1939)

Although not known for his silent films, Fleming did get his start during the silent era. He was a cinematographer for D.W. Griffith and then Fleming directed his first film in 1919. Most of his silent films were swashbuckling action movies with Douglas Fairbanks or formulaic westerns. He is the only director to have two films on the AFI top 10 and they happened to have come out the same year.

Hal Roach: Lonesome Luke films starring Harold Lloyd, Our Gang shorts, Laurel and Hardy shorts, and Of Mice and Men (1939)

It is not really fair to put Hal Roach in the silent era directors because he was influential at the time but he had a 75 year career. He was a producer and film studio head and even had a studio named after himself. His biggest contribution to the silent era was his production of Harold Lloyd short comedies and he continued to produce films in the early talkies including Laurel and Hardy shorts, Our Gang shorts, and Wil Rogers films. Roach was the inspiration for the film Sullivan's Travels, in which a famous director who only did frivolous comedies goes out into the world to find inspiration to find a serious drama. Roach did direct a single serious drama, Of Mice and Men, but it came out in 1939 and was buried underneath the works of Victor Fleming. The wealthy cigar smoking studio head that many people think of when they picture a film studio suit is based on this guy. The man would not quit and stayed in the business into his 90s and lived to the ripe old age of 100.

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

simSbiotic´s guide

ICONIC DESIGN

I offer you selection of my favourite design pieces created during the 20th century that are considered icons of modern era at the same time. They are not only a part of the permanent collections of world´s the most leading design and decorative art museums but thanks to their timeless appearance they are still the best ingredient of many high-end modern interiors.

And maybe this list may seems as cliché I try to bring to you a context that proves the most of the best designs were revolutionary, visionary and innovative at that times and pushed the boundaries not only for design and furniture industry but for everyday simple life.

And that´s what matters.

Pavli

1. Vitra - Eames House Bird, around 1910 ♥ / ♥ / ♥

The bird was originally carved by Charles Perdew around 1910 as a bird decoy for hunters and became popular in the 1950s, primarily for its minimal shape and dark color. It was popularized by Charles and Ray Eames, who acquired one on their travels in the Appalachian mountains and soon can be seen in many of their product photo-shoots.

2. Arne E. Jacobsen - Ant chair, 1952

3. Pierre Jeanneret - Office chair for Chandigarh, 1955-1956

4. Charles and Ray Eames - Rocking Armchair Rod (RAR), 1948

Large family of Plastic chairs are the most well-known designs by Eames. Designer couple won second prize with them in the 'International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture Design', organised by the New York Museum of Modern Art. They used a fiberglass, a material that was entirely new to the furniture industry and at that time reserved for the US Army.

5. Charles and Ray Eames - Dining Armchair Rod (DAR), 1948

6. Charles and Ray Eames - Lounge Chair and Ottoman, 1956

7. Charles and Ray Eames - Dining Armchair Wood (DAW), 1948

And also another type of Plastic chair - Dining Side Wood (DSW), 1948.

8. Warren Platner - Platner Arm Chair, 1966

Not limiting itself to architecture, Warren Platner also experimented in furniture design. In the 1960s, as the modernist movement became more expressive, Platner focused on a quieter aesthetic, wishing to create more graceful structures. The Platner Collection captured the decorative, gentle shapes and is now considered a design icon of the modern era.

9. Charles and Ray Eames - Eames Lounge Chair Wood (LCW), 1945

In 1999, Time magazine declared the LCW the greatest design of the 20th century. The original LCW was a result of designing plywood splints for the US air force. After several experiments Eames came up with an “honest” ergonomic chair that was soon coveted the world over.

10. Vico Magistretti - Atollo lamp, 1977

This object of Industrial design by Italian designer Vico Magistretti for O luce won the 1979 Compasso d’Oro award and took its place in the permanent collections of design and decorative art museums as MoMA, becoming so much more than just a lamp: an icon.

11. Eero Saarinen - Tulip chairs and Pedestal tables, 1955-1956 ♥

The collection was designed by Eero Saarinen for the Knoll company of New York City. The furniture with its smooth lines of modernism and experimental materials is considered a classic of industrial design.

12. Hans J. Wegner - CH24 | WISHBONE CHAIR, 1949

The very first model that Hans J. Wegner designed exclusively for Carl Hansen & Søn.

13. Jorgen Hovelskov - Harp Chair, 1968

14. Poul Henningsen - Artichoke Lamp, 1958

The iconic lamp was designed for a commision for a restaurant in Copenhagen. The fact that the light source couldn’t be seen was very revolutionary at the time. When people didn’t see a lamp as a nice object but simply as a generator of light, Henningsen was one of the first to think of both.

15. Jean Prouvé - Standard chair, 1934 ♥

During World War II, Prouvé was a member of the French Resistance, and his first post-war efforts were devoted to designing metal pre-fab housing for those left homeless by the conflict. The Standard Chair exemplifies a fundamental aspect of Prouvé’s furniture design: his unwavering focus on structural requirements.

16. Marco Zanuso - Lady armchair, 1951

Designed in 1951 for Arflex, the Lady armchair won the gold medal at the IX Milan Triennale in the same year. The armchair brings innovation to the traditional manufacturing technique for making armchairs and sofas, with each part manufactured separately and then assembled.

17. Verner Panton - Panton chair, 1960-1967

S-shaped chair is the world's first moulded plastic chair and it is considered to be one of the masterpieces of Danish design.

18. Arne Jacobsen - Cylinda-Line, 1967

Arne Jacobsen hoped that Cylinda-line products would enrich the lives of average consumers with industrial design that was functional and affordable. It won the Danish Design Council’s ID Prize in 1967.

19. anknown designer - Acapulco chair, around 1950 ♥

The designer remains unknown to this day. The story goes that while visiting Acapulco in the 50s, a French tourist was uncomfortably hot sitting in a solidly-constructed chair in the Mexican sunshine. Inspired by the open string construction of traditional Mayan hammocks nearby, he designed a chair fit for the modern tropics.

20. Harry Bertoia - Bertoia Diamond Chair, 1952

Bertoia found sublime grace in an industrial material, elevating it beyond its normal utility into a work of art.

21. Hans J Wegner - PP701 Chair, 1965 ♥

22. Alvar Aalto - Table 915 for Artek, 1932

23. Anna Castelli Ferrieri - Componibili storage unit, 1969

The Componibili storage unit by Kartell is a design classic that is a part of the permanent collections of Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Center Georges Pompidou in Paris.

24. Charles and Ray Eames - Molded Plywood Lounge Chairs with Metal Bases (LCM), 1946

25. Serge Mouille - Serge Mouille sconces, 1958

Serge Mouille was asked by Jacques Adnet, the director of the French Arts Company, to create 'big lightings' for his South-American customers. Mouille imagined then the famous Standing lamp 3 arms and Standing lamp one arm that was the beginning of the « Formes Noires » collection.

26. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe - Barcelona chair, 1929

In 1929, Mies was commissioned by the German government to design the German pavilion for the Barcelona Fair, one of the most elegant pieces of architecture ever created. This building required furniture that simply did not exist, so Mies responded to this commission with the Barcelona chair.

27. A. Bonet, J. Kurchan and J. Ferrari Hardoy - The butterfly chair, also known as a BKF chair, 1938 ♥

The BKF chair (the initials of its creators) was developed for an apartment in Buenos Aires. In 1940, a picture of the chair appeared in the US Retailing Daily, where it was described as a "newly invented Argentine easy-chair for siesta sitting", few months later, the chair was awarded and attracted the attention of the MoMA in New York immediately.

28. Arne Jacobsen - Drop chair, 1958

Arne Jacobsen designed his Drop chair exclusively for the legendary SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen, along with the Swan and the Egg chair. The Drop chair was Arne Jacobsen’s own favourite piece.

29. Bonderup & Thorup - Semi pendant light, Gubi 1968

30. Morgens Lasse - Kubus 4 candle holder, 1962 ♥

31. Marcel Breuer - The Wassily Chair, 1925-1926

While the head of the cabinet-making workshop at the Bauhaus in Germany, Breuer revolutionized the modern interior with his tubular-steel furniture, inspired by bicycle construction. His first designs, including the Wassily, remain among the most identifiable icons of the modern furniture movement.

649 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Movie Odyssey Retrospective

Fantasia (1940)

With production on Bambi postponed, Walt Disney dedicated himself to Pinocchio (1940) and a film featuring animated segments accompanying classical music. Walt’s demands for innovation saw Pinocchio’s budget skyrocket, and the film left Walt Disney Productions (today called Walt Disney Animation Studios) on unstable financial grounds. This laid impossible financial expectations for the latter film – tentatively entitled The Concert Feature – to meet. War halted the possibility of cross-Atlantic distribution as Walt continued to emphasize innovation for each of his features and workplace tensions rose among his animators. What was planned as a glorified Mickey Mouse short set to Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice – Mickey’s popularity was flagging by the mid-1930s, trailing other Disney counterparts and Fleischer Studios/Paramount’s Popeye the Sailor – grew to include seven other segments. The film that became known as Fantasia remains the studio’s most audacious work. Though it built off the visual precedents of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), the volume of artistry for artistry’s sake contained in Fantasia, eighty years later, remains unsurpassed.

After the Philadelphia Orchestra’s conductor/music director Leopold Stokowski offered to record The Sorcerer’s Apprentice for free (he did so with a collection of Hollywood musicians; the English-Polish conductor, a rare conductor who spurned the baton, was among the best of his day), cost overruns on The Sorcerer’s Apprentice led to its expansion as a feature. To provide commentary as Fantasia’s Master of Ceremonies, the studio sought composer and music critic Deems Taylor – who came to Disney and Stokowski’s attention in his role as intermission commentator for radio broadcasts of New York Philharmonic concerts. But both Disney and Stokowski were too busy during the summer of 1938 to brief Taylor on their plans. Stokowski spent that summer in Europe seeking permission for the rights to use certain pieces from various composers’ families (this included visits to Claude Debussy’s widow and Maurice Ravel’s brother); Disney was occupied with the construction of the Burbank studio. After Stokowski returned from Europe in September, Disney asked Taylor to come to Los Angeles to formally discuss Fantasia. Taylor agreed, arriving one day after Stokowski and Disney began their meetings, staying in Southern California for a month.

Over several weeks that September, Disney, Stokowski, and Taylor made the final selections for pieces – suggested by story directors Joe Grant and Dick Huemer (both worked on 1941’s Dumbo and 1951’s Alice in Wonderland) – to be featured in Fantasia. Hours were spent listening to classical music recordings, followed by brainstorming potential visualizations. The meetings were recorded by stenographers, with transcripts (housed at the Walt Disney Archives in Burbank) provided to all three participants. During these meetings, Walt mostly listened to Stokowski and Taylor consider every suggestion by Grant and Huemer:

DISNEY: Look, I really don’t know beans about music. TAYLOR: That’s all right, Walt. When I first started, I thought Bach wrote love stuff – like Romeo and Juliet. You know, I thought maybe Toccata was in love with Fugue.

During these meetings, an admiring Walt – in addition to gifting a potential last hurrah for Mickey Mouse and to create a film unrestrained by commercial demands – realized he wanted to create a gateway to classical music for those who might not otherwise give such music a chance. Always leading his writing staff in developing stories, Walt felt relieved that he could share this responsibility with Stokowski and Taylor. Free of the storytelling stresses plaguing the Pinocchio and Bambi productions at the time, these tripartite meetings were not beholden to narrative cohesion, allowing the participants to suggest anything that their imaginations conjured. Without the constraints of narrative logic or predictions about what an audience wanted to see, Fantasia became the center of Walt Disney’s passion until its completion.

Nine selections were made by the trio, with one piece later being dropped entirely (Gabriel Pierné’s Cydalise and the Satyr) and another being replaced after its completion. A completed segment for Debussy’s Clair de Lune* was substituted out for Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 (the mythological scenario Walt envisioned for the Pierné reverted to the Beethoven, but more on this later). Over the next few years, Disney’s animators would complete the artwork; Stokowski would study, arrange, and record the selections with the Philadelphia Orchestra (except for The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, which had already been recorded); Taylor would write his introductions to be filmed at the Disney studios.

In almost all of cinema, music accompanies and strengthens dramatic or comedic visuals. Fantasia is the reverse of this relationship. The animation provides greater emotional power to the music – an arrangement that may be startling to viewers unfamiliar with or disinclined to classical music or cinematic abstraction. Fantasia’s opening scenes and piece introductions feature the affable Taylor, who outlines the film’s conceits:

TAYLOR: Now there are three kinds of music on this Fantasia program. First, there’s the kind that tells a definite story. Then there’s the kind that, while it has no specific plot, does paint a series of more or less definite pictures. And then there’s a third kind, music that exists simply for its own sake.

That last kind, also known as “absolute music”, opens Fantasia with Johann Sebastian Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, an organ piece arranged for orchestra (“Toccata” and “Fugue” refer to the musical forms of the piece’s two halves). As James Wong Howe’s (1934’s The Thin Man, 1963’s Hud) gorgeous live-action cinematography of the orchestra (the Toccata) transitions to animation (the Fugue), the audience witnesses Walt Disney Animation’s first, and arguably only, foray into abstract animation – as opposed to abstract stylizations to bolster a macro-narrative – for a feature film. The Toccata and Fugue is a pure visualization of listening to music, as if the animation was improvised. The sequence involves, among other things, string instrument bridges and bows flying in indeterminate space, figures and lines rolling across the screen, and beams of light and obscured shapes timed to Bach’s piece. In these opening minutes, Fantasia announces itself as a bold hybrid of artistic expression in atypical fashion for Disney’s animators.

Next is The Nutcracker Suite by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, which is subdivided into six dances (“Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy”, “Chinese Dance”, “Arabian Dance”, “Trepak”, “Dance of the Reed Flutes”, “Waltz of the Flowers” – these dances are placed out of order, and the “Miniature Overture” and “Marche” which open the suite are not present). Disney, Stokowski, and Taylor made this selection decades before Tchaikovsky’s now-most famous ballet became a Christmas cliché in the United States – it was barely performed in the early twentieth century and is usually regarded, among classical music experts and by the composer himself, as a lesser Tchaikovsky ballet.

History aside, this animated treatment of The Nutcracker utilizes an astonishing array of different animation techniques across all six dances. With The Nutcracker, the Disney animators, for the first time, take a piece with a preexisting story, animate sequences adhering to the music’s essence, yet producing images that have nothing to do with the original material. In Fantasia, The Nutcracker remains a ballet – the sugar plum fairies, racially insensitive mushrooms, fish, and flowers move as if they are on a ballet stage. But there is nothing, in the sense of a narrative through line, to connect all six dances. Set to the changing of the seasons, The Nutcracker contains gorgeously-animated fairies and intricate fish (Cleo from Pinocchio was a testing run for the “Arabian Dance”), climaxing with fractal flurries that look like an antique Christmas card brought to life. Even the racist “Chinese Dance” exemplifies masterful character design – simplicity does not preclude expressiveness. The Nutcracker’s spectacular inclusion improved Tchaikovsky’s standing and his least acclaimed ballet among casual classical music fans.

Based on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s poem of the same, Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice ushers in the Mickey Mouse short that overshadows all others. With the animators’ adaptation closely following Goethe’s poem, Dukas’ original piece is impossible to listen to without imagining Mickey, rogue anthropomorphic broomsticks, and thousands of gallons of water. The Sorcerer’s Apprentice marked the cinematic debut of Mickey Mouse with pupils, as designed by Fred Moore (the dwarfs on Snow White, the mermaids in 1953’s Peter Pan) – Mickey was first drawn with pupils on a program to an infamous, booze-filled party Walt Disney threw in 1938. With pupils, Mickey’s gaze provides a sense of direction that black ovals make ambiguous. The additional personality – not to say Mickey Mouse’s original character design lacked personality – thanks to the pupils strengthens Mickey’s expressions of jollity, shock, submissiveness. A lanky, stern sorcerer is Mickey’s brilliant foil. Their physical differences and reactions imbue The Sorcerer’s Apprentice with a troublemaking charm recalling Mickey’s earliest short films, sans the slapstick that defined those appearances. These decisions heralded a new era for how the Walt Disney Studios’ mascot would be animated and portrayed in his upcoming shorts.

This segment’s chiaroscuro sets a pensive atmosphere, enclosing Mickey in a black and brown gloom as he – a nominal apprentice – is tasked with menial duties, not magic. The indefinite shape of the sorcerer’s chambers owes to German Expressionism (as does the penultimate piece in Fantasia), with its impossibly curved angles and architectural fantasy hiding secrets that no sorcerer’s apprentice assigned to carry buckets of water could understand. The Sorcerer’s Apprentice tonal shifts always feel justified, rooted in the sequence’s character and production design – although, in this regard, the sequence is surpassed later in Fantasia.

Immediately following a mutual congratulations between Mickey (voiced by Disney) and Stokowski is Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Stravinsky’s brief one-act ballet/piece debuted in 1913 to an audience riot because of its musical radicalism – The Rite of Spring liberally partakes in polytonality (using two or more key signatures simultaneously), polyrhythms, constant meter changes, unorthodox accenting of offbeats, chromaticism, and piercing dissonance. Concert hall attendees had heard nothing like The Rite of Spring before and, even in 1940, Stravinsky’s composition divided audiences. The Rite of Spring – precipitating the concert hall’s philosophical battles of the late twentieth and twenty-first century over whether melody and coherent rhythm still has a role to play in contemporary classical music – is a gutsy choice to present to general audiences.