#the courtship of inanna and dumuzi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It is a crime that the story of Inanna and Dumuzi is not more main stream. She sent her husband to hell because he wouldn’t bow to her. The main argument for the theory that early human societies were matriarchal.

#depends on the translation#but this is pretty much it#sumerian#Babylonian#mythology#classics#gilgamesh#the courtship of inanna and dumuzi#inanna#dumuzi#feminism#historical feminism

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

the rabbithole this post about a pornographic sumerian poem is beginning to lead me down....

#so far: i see this post with screenshots from twitter which has screenshots of some rather saucy sumerian poetry. me being me and being#kind of interested (though not very knowledgeable) about sumerian things and intrigued by saucy ancient poetry am like okay but where did#these actually come from. i look through the comments to try and find clues. find out its supposedly from something called 'the courtship#of inanna and dumuzi'. look this up. find a website which just has one webpage with this poem but it has a citation. look up the citation.#the authors name is misspelled and the other author was omitted but find the book its from. look through it on internet archive. find the#poem but the whole thing generally seems too complete and clear to be a sumerian text. look at the back to see if theres an index. it says#this version is actually kinda cobbled together from a bunch of DIFFERENT sumerian love poems and then workshopped a lot to work well in#english. however. it does not list the poems its compiled from. and now this is where im stuck. and i have to go to class now#my next steps though probably trying to find the original tweet and hope the person who posted it sourced it?#cause the screenshots dont seem to be from that website/that version of it

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the starting of the quarrel

Came the lovers' desire.

- The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi, translated by Samuel Noah Kramer and retold by Diane Wolkstein

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

from ‘The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi’ in Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer, trans. Diane Wolkstein and Samuel Noah Kramer.

65 notes

·

View notes

Note

It's ancient sensual poetry for you, eh?

Try "The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi"

2800 BCE Sumeria

My vulva, the horn,

The Boat of Heaven,

Is full of eagerness like the young moon.

My untilled land lies fallow.

As for me, Inanna,

Who will plow my vulva?

Who will plow my high field?

Who will plow my wet ground?

As for me, the young woman,

Who will plow my vulva?

Who will station the ox there?

Who will plow my vulva?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inanna and Dumuzi get it on

Our myths don't look like myths to us – they look like axioms. Some things in our worldview, if we saw them from a far enough remove, would look more like myth than we'd ever have thought. The past, say. The future.

Another voice note for my Mythology and Literature class, on the goddess Inanna’s choice of a mate, and the meaning of their meeting. Lightly edited, like the last one. If you’d rather listen than read, here you are:

https://artofcompost.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/inanna-2.mp3 “The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi”

A thought first more generally about what myth is, what our relationship to myth…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Ninshubur, Inanna’s Sukkal: Just a Servant or Something More?

Special thanks to my girlfriend for providing the vintage shoujo parody above, feat. Inanna, Ninshubur and Eblaite artifacts Due to its unique character this post requires a special preface. Most of my “serious” coverage of mythology is meant to be presented as rigorously as possible for a layperson doing this mostly for entertainment, which is who I ultimately am. This post represents a departure from this standard - it’s basically entirely unfounded speculation, personal feelings and wishful thinking. Similar posts often get passed around accompanied by grandiose claims from commenters, so I will stress that I wrote this for personal reasons and only discuss personal feelings. I do not claim this is some sort of suppressed truth, as I am particularly not fond of cases where personal interpretations - which I view as valid if they are acknowledged as just that - are used to claim modern, rigorous research is in fact phony or a nefarious conspiracy. With that out of the way - as stated in the title, I’m going to discuss a case which as many of the regular readers are aware of is close to my heart - that of how Mesopotamian literature depicts the relationship between Inanna and Ninshubur (a deity I like so much that she now has a longer and better sourced wikipedia page than many more major Sumerian deities). I plan to show why I personally think that regardless of the intent of the original authors, there is enough subtext in known sources - presumably not necessarily intentional - to interpret them as a couple. I will also try to highlight Ninshubur’s rarely discussed prominence, both in myths and elsewhere. Parts of the article simply discuss vaguely relevant historical background and primary sources. As usual, I am also providing a bibliography. Therefore, I hope that even if you are not really interested in ultimately pretty silly speculation, you will find something interesting under the cut. Meanwhile, if you are interested in relationships between women more than scholarship, I hope that this post will serve as a fun example why the study of mythology can lead one to find unintended subtext.

The basics - Inanna, Ninshubur and the descent myth

Impression of a cylinder seal from the Old Akkadian period depicting Inanna (Wikimedia Commons) Inanna was one of the major deities worshiped by the Sumerians, the ancient inhabitants of the southern part of modern Iraq. She was also adopted into the beliefs of other cultures of ancient Mesopotamia. In hierarchical listings of deities she is usually placed somewhere right behind the pantheon heads. She was responsible for, among other things, kingship, love, war and assorted celestial matters. She is also one of the most recurring deities in literary compositions written in Sumerian, with a considerable number being available as part of the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Inanna’s love life was regarded as rather complex. Her most recurring lover was the shepherd god Dumuzi, who is a classic specimen of the clade of periodically dying deities, a category which also included the likes of medicine godling Damu, king Gudea’s personal deity Ningishzida and the elusive underworld god Alla. Multiple narratives about the courtship and love of Inanna and Dumuzi were in circulation in antiquity, most of them joyful. However, some also deal with Dumuzi’s untimely death (which,it should be noted, was also a subject of works unrelated to his relationship with Inanna). The degree of Inanna’s involvement varied from composition to composition, from cause to passive onlooker to vengeful avenger. Arguably, however, the most famous is Inanna’s Descent, in which Dumuzi’s death is attributed to his unwillingness to mourn Inanna during *her own* temporary death. A prominent aspect of this myth is also Inanna’s reliance on Ninshubur, a goddess of slightly lesser caliber serving as her sukkal. Sukkal is a term which can refer to a deity’s “ second in “command” - in other words, a sidekick. The word was also used to describe a rank of human court officials, in which context authors variously translated it as “vizier” or “envoy”. Despite the nature of her position, Ninshubur’s status was hardly a minor deity, judging from her popularity in the sphere of personal worship and from a number of theological texts. She was arguably the archetypal example of a sukkal, and her functions - those of a divine messenger, diplomat and mediator - largely stem from this status. Dumuzi’s and Ninshubur’s roles in the story differ greatly. Prior to the reveal that he was not partaking in the customary mourning rites, Dumuzi has minimal presence in the narrative. Ninshubur, by contrast, is an active participant, entrusted with enacting an emergency plan in case of Inanna’s prolonged stay in the underworld, equivalent to death. A long section is dedicated to her grief and to the journey she undertakes to attempt to convince major gods to resurrect Inanna. Ninshubur’s adventure culminates in the creation of two artificial genderless beings who manage to revive Inanna, at the command of the god Enki. Subsequently, Ninshubur reunites with the resurrected Inanna, who praises her for her devotion and protects her from the galla, demonic underworld constables. The term also denoted mundane policemen, or at least people who could be roughly considered their equivalent in ancient Mesopotamia. In the discussed myth, they are meant to deliver a replacement for the resurrected Inanna to the underworld at the orders of its ruler, Ereshkigal. In this myth - but surprisingly not anywhere else - Ereshkigal is regarded as Inanna’s older sister. Much of the popular perception of the story appears to be centered on this relation but it is ultimately Ninshubur whose connection with Inanna is particularly close, as seen in the quote below (all quotes from Inanna’s Descent in the article are sourced from ETCSL): This is my minister of fair words, my escort of trustworthy words. She did not forget my instructions. She did not neglect the orders I gave her. She made a lament for me on the ruin mounds. She beat the drum for me in the sanctuaries. She made the rounds of the gods' houses for me. She lacerated her eyes for me, lacerated her nose for me. She lacerated her ears for me in public. In private, she lacerated her buttocks for me. Like a pauper, she clothed herself in a single garment. All alone she directed her steps to the Ekur, to the house of Enlil, and to Urim, to the house of Nanna, and to Eridug, to the house of Enki. She wept before Enki. She brought me back to life. How could I turn her over to you? Afterwards, Ninshubur, who apparently spent the rest of her Inanna-free time weeping at the entrance to the underworld, accompanies Inanna during visits to various lesser underlings’ houses (well, temples); as it turns out, they too mourned properly, and after brief words of praise are left to their own devices. However, that is not the case when it comes to Dumuzi: They followed her to the great apple tree in the plain of Kulaba. There was Dumuzid clothed in a magnificent garment and seated magnificently on a throne. The demons seized him there by his thighs. (...) They would not let the shepherd play the pipe and flute before her She looked at him, it was the look of death. She spoke to him, it was the speech of anger. She shouted at him, it was the shout of heavy guilt: "How much longer? Take him away." Holy Inanna gave Dumuzid the shepherd into their hands. The rest of the myth is poorly preserved, but seemingly Inanna eventually has a change of heart and the well-known system in which Dumuzi and his sister switch places in the underworld every 6 months is established. The ending doesn’t address why it was Ninshubur, rather than Dumuzi, who received the instructions pertaining to the mourning of Inanna’s death and her subsequent resurrection. It doesn’t also explain why Ninshubur stood by the entrance of the underworld, waiting for Inanna, something not even the other mourners did. The goal of this article is to find out if there are any grounds to assume that there is a romantic component to this issue, at least from a modern point of view. I’ve noticed that there are few, if any, academic publications dealing with related matters, and that generally potential lesbian subtext - intended or not - in myths generally is hardly discussed, therefore I hope it will be an interesting curiosity to you, if nothing else.

Gay relationships in Mesopotamian mythology

Naturally, the first question which needs to be addressed is whether any form of love between people of the same gender occurs in relevant literature in the first place. The answer is a cautiously optimistic “yes.” Of course, almost everyone is aware of the speculation about the nature of the relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu, the most famous heroes of Mesopotamian literature. Therefore it probably comes as no surprise to any readers that many modern authors seek evidence that at least in some portrayals they were in love. The problem is arguably less whether anyone did interpret them as in love, and more how common it was and which sources show it best. Authors who present this view include the world’s arguably greatest Gilgamesh expert, Andrew R. George, as well as hittitologist Gary Beckman. According to George, the notion that Gilgamesh and Enkidu loved each other is present first and foremost in a version of the poem Death of Gilgamesh, known from Tell as-Sib excavations in Iraq’s Diyala region (ancient Me-Turan). The poem is Sumerian in origin and predates the famous standard Epic of Gilgamesh, which only developed after the Old Babylonian period. The passage in mention is apparently not actually present in many of the known copies. It features the head god, Enlil, informing elderly, sick (the illness seems to be the doing of Namtar, known as both a disease of death and as an envoy of the netherworld) Gilgamesh that in the afterlife he’ll be reunited with Enkidu. Due to the emotional value of this passage I will simply let you read it yourself:

The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts vol 1 by A. R. George, p. 142 The belief that loved ones might be reunited in the afterlife appears in texts from various periods of Mesopotamian history, so it can be safely assumed it was not an uncommon idea, even if the most famous myths present the afterlife as incredibly unpleasant. Additionally, Enkidu is evidently treated as a member of Gilgamesh’s family but not a sibling here. My first thought after reading George’s description of the Me-Turan version of the tale of Gilgamesh and Enkidu was to wonder if it is possible that versions which seemingly stresses the view of them as a couple might reflect the needs of a specific audience. Thanks to George’s own studies, as well as those of other authors, we do know that the stories of Gilgamesh were often adapted to fit the tastes of one audience or another. For example, in Hurrian and Hittite translations locally popular deities, such as Shaushka (known as “Queen of Nineveh” or “Ishtar of Subartu”), Hittite Sun God of Heaven, or personified Sea known in both these cultures factored into the story (both as replacements of familiar characters and as stars of brand new “story arcs”), while the descriptions of distant Uruk are often shortened as they were of comparatively little interest to inhabitants of Syria and Anatolia. Could therefore the Me-Turan version represent an adaptation written by and/or for people who were invested in the view of Gilgamesh and Enkidu as a couple more than the average aficionado of similar poetry in ancient Mesopotamia? That would be my assumption, but you should bear in mind it is nothing more than that I am not an actual authority. I am not aware of any examples of mythical figures other than Gilgamesh and Enkidu engaging in similar endeavors. The other potentially relevant evidence comes from different genres of texts, such as omens, magical formulas and (middle Assyrian) laws. Sadly, there isn’t much evidence for gay relationships and what there is doesn’t necessarily match the sphere of myth, to put it lightly (the aforementioned legal texts, in particular, are not exactly pleasant to read). For what it’s worth, there are sporadic references to love magic meant to guarantee the love of a man for another man, alongside the much more common straight variations (both with men and women as targets of the ritual). I will not address the issue of the galla (not to be confused with the homonymous underworld constables!) and similar priestly classes here as the matter is not settled, and many researchers involved are hardly rigorous (this article in particular is a nightmare but it’s not much better elsewhere). All that can be said about the galla with certainty is that they were lamentation singers. It has been argued that they were possibly regarded as possessing a distinct, unique identity, but what that entailed is hard to tell. It does appear that their mythical counterparts in Inanna’s Descent, the two entities created by Enki, are genderless, at the very least. Galla priests performed songs in a “dialect” of Sumerian, emesal, popularly understood as “women’s speech” - however, it’s not really an accurate translation. While the precise meaning is unclear, something like “high pitched speech” might be more appropriate. Emesal is sometimes regarded as a “sociolect” spoken by a specific group (ie. women) but it’s actually more likely to be first and foremost a “genrelect” reserved for specific liturgical purposes according to recent research. As summed up by Piotr Michalowski in a very brief encyclopedic summary, it appears to be “restricted to direct speech of goddesses and women in certain types of literary texts, in particular lamentations.” Bear in mind even this use is not universal: Dumuzi speaks emesal in some texts, Inanna does not in others. Enheduanna, arguably the most famous woman in Mesopotamian history, did not write in emesal, even when it came to direct speech; meanwhile, there are references to purification specialists - who were not galla - reciting emesal texts. Emesal aside - no primary sources actually discuss the sexuality of the galla to any meaningful degree and it’s not even certain if all galla were assigned male at birth, to put it in modern terms. Therefore, any such assumptions pertaining to them are just speculation, often with a dash of vintage orientalism thrown in for good measure. That’s it for men. How about women? As noted by Frans Wiggermann in his brief and somewhat flawed overview of references to sexuality in Sumerian and Akkadian texts there are no known direct references to women attracted to women and to relevant activity in any primary sources (I think there is a passage in a late hymn to Nanaya which might be an exception, I wrote about it a few months ago). He provides no clear explanation for this, though he notes that most scribes were obviously men aligned with the dominant power structures. This state of affairs largely shapes the character and contents of many sources. I personally think it’s safe to say that the fact the literacy rate among men was much higher than among women is at least partially to blame.

Female literacy, religiosity and relationships between women in myths

Generally speaking, the level of literacy even in cultures with a rich scribal tradition was naturally pretty low in the bronze and iron ages, with the only estimate I found (pretty old, I should note) being 2-5% for “western Asia and Egypt” collectively. These are therefore presumably the figures we can apply to ancient Mesopotamia for example in the Ur III and early Old Babylonian periods, when many of the famous myths developed in their presently known textual forms. While it was not entirely impossible for a woman to become a scribe, or to learn how to write through other means (ex. as part of a noblewoman’s preparation for courtly life), it was much less common for them than for men. For instance, only between 4 and 6 (2 cases are uncertain) scribes or scholars identified by name in colophons of known texts were women. Of course, not every text has a colophon with such information, so it’s not impossible that we in fact know more texts written or copied by women, but whose authorship will never be possible to prove. It’s also worth noting these few examples indicate the presence of women (not many, but still) on most stages of scribal education. Nameless female scribes also at times appear in economic documents. Nevertheless, references to women in other similar professions are somewhat infrequent. The exception to this was female physicians, who were generally expected to be literate. I’ve gathered some more detailed information here. This perhaps is somewhat of a reach, but I personally assume both the lack of references to romantic relations between women and the relatively small number of compositions dealing with bonds between female deities seemingly not based on blood relation (and even the latter are hardly common!) can be attributed to the comparatively small number of female scribes, outlined above. A similar argument has been advanced by Alhena Gadotti, though in reference to mortal women as characters in texts copied in scribal schools: women “were generally not part of the cultural, political, and economic elite that the Old Babylonian scribal schools produced and therefore did not play a particularly prominent part in the corpus.” As remarked by Joan G. Westenholz and Julia M. Asher-Greve, interest in female deities was somewhat higher among women than men - “numerous women chose the temple of a goddess for their votive gifts (...), or preferred the cult of a goddess (...), or have names composed with that of a goddess, or are depicted worshiping a goddess” [on cylinder seals - clarification mine]. It’s of course impossible to deal in absolutes, though - there’s ample evidence for personal devotion to gods like Shamash, Zababa, Dagan or Marduk among women, and to goddesses such as Inanna, Ninisina or Namma among men; kings were almost always men but there is a fair share of areas where the source of kingship was at least in certain time periods held to be a female deity - Ninisina in Isin in the Isin-Larsa period, Ishara in Ebla c. 1700 BCE, Belet Nagar, nomen omen, in Nagar in the Old Babylonian period, Inanna in Uruk at various points in time, etc. Still, I think the point might be valid.

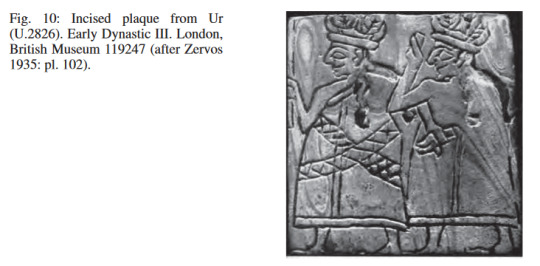

A possible depiction of Geshtinanna and Geshtindudu (Goddesses in Context by J. M. Asher-Greve and W. G. Westenholz, p. 387; identified as such on p. 168) Other than Inanna and Ninshubur in Inanna’s Descent and a number of other sources, the only two goddesses I am aware of who appear to share a close bond in myths and aren’t a mother-daughter pair (like Nisaba and Sud/Ninlil or Ninhursag and Ninkasi) are Dumuzi’s sister Geshtinanna and a certain Geshtindudu, who are to my knowledge not attested outside of a small handful of mythical fragments. Julia M. Asher-Greve outright describes these two as “divine girlfriends' ' - I presume not in the romantic sense, though. This is probably just a paraphrase of the ETCSL translation of Dumuzid’s Dream which indeed introduces Geshtindudu as “Her [Geshtinanna’s] girl friend.” Asher-Greve also speaks of it as “one of the few relationships between goddesses based on friendship.” As for other relations based on friendship: I’ve seen references to a myth(?) about Ninisina and Nintinugga - the medicine goddess par excellence and her small time “ersatz” from Nippur - visiting each other (source; it’s on p. 5), but I have not been able to locate it so I can’t tell if it should count as another example. Additionally, while the myth Enlil and Sud deals first and foremost with the relationship between Sud and her mother Ninlil and with her tumultuous romance with Enlil, it seems a poorly preserved section also had Sud interact with Enlil’s sister Aruru (who you may know as the creator of Enkidu in the Epic of Gilgamesh). Given how Enlil and Sud generally seems to have notably more “Ninlil-centric” outlook than its “rival” myth Enlil and Ninlil (which treats Ninlil, a popular and high-ranking deity, oddly poorly), perhaps this should be counted as an example too, though it has been argued the passage might simply indicate that the bridegroom’s sibling played some role in traditional marriage rites. While each of these myths surely could be an interesting topic, I sadly won’t discuss them in detail here (do expect a post on Enlil and Sud at some point, though), as the this article is ultimately about Inanna’s Descent and other sources pertaining to Ninshubur.

Inanna’s Descent once more

While I already provided a brief overview of Inanna’s Descent earlier, the fact that its contents are frequently misinterpreted - often by authors with no knowledge but a large audience - means that some more context is needed. From Jungian nonsense (with all due respect for Olga Tokarczuk, whose works I generally enjoy, her Anna In w grobowcach świata falls into this category) and weird attempts at elevating Ereshkigal well beyond the rank attributed to her in antiquity to a baffling attempt at understanding the myth in Nietzschean terms, Inanna’s Descent is arguably among the most tormented Mesopotamian literary texts, both online and offline. To begin with, it’s important to place it in the context of Sumerian beliefs regarding proper care for the dead. As we can learn from a variety of sources, from myths to prayers to personal letters, the Sumerians viewed mourning and other related matters as incredibly important. Mourning was expressed in many forms, though particularly notable were funerary libations - you can find a reference to this even in the discussed myth: she offers generous libations at his wake, proclaims Inanna about the purported funeral of Ereshkigal’s supposed late husband. Elsewhere, the city of Enegi, associated particularly closely with the cult of the dead, is itself called the “libation pipe of the earth.” Known texts stress that close family, such as spouses, siblings, or children, should be involved in funerary rites. As a matter of fact, from some texts we learn that the status of the dead in the underworld depends entirely on their close ones’ proper adherence to funerary customs. The important role of family in mourning rites creates a problem for the narrative of Inanna’s Descent: Ninshubur is not exactly a family member. She is a courtier. While the “public figures” of ancient Mesopotamia were often mourned publicly by a large number of people, here the mourning seems to be private. As far as I understand - Ninshubur is essentially instructed to act as a family member would. Following the usual genealogy of Inanna, there is no real place for Ninshubur on her family tree, as it is generally safe to assume Inanna’s parents are Nanna and Ningal, while she is herself childless. In fact, there is no strong indication Ninshubur was even conceptualized as part of a family tree in the first place. As noted by Frans Wiggermann, texts are largely silent about her parentage. To be fair this is not uncommon for servant deities, divine spouses (even the most prominent ones like Aya and Shala have no established genealogy!) and the like. Curiously, Ninshubur’s mourning is described in very similar terms as that of Ningishzida’s wife Ninazimua in a composition possibly dealing with the former’s death, as Jeremy Black and Judith Pfitzner remarked in their respective articles about the composition Ningishzida and Ninazimua. Of course, this alone is not exactly a strong argument, as parallels can be drawn between these and the figures of mourning sisters and mothers in other texts dealing with deaths of gods. Still, it does appear to be somewhat of an outlier to have a servant, rather than a relative, express grief in such a composition. It’s worth noting that while the only example we have is Inanna’s Descent, we know from preserved Sumerian catalogs of hymns and other similar compositions that there were a considerable number of currently lost texts which dealt with Ninshubur’s grief over something that happened to Inanna. Whether this was a different version of the story or some other, presently unknown, sorrowful event (perhaps banishment only known from an incredibly fragmentary text?) is impossible to tell. A number of researchers, most recently Dina Katz, have proposed that Inanna’s Descent as we know it was in reality the result of combining multiple older narratives, as it only dates back to the Old Babylonian period. I speculate that the aforementioned unknown Ninshubur texts could perhaps have been predecessors to the version of the myth we see today. Such a process of development was not uncommon for Mesopotamian myths. Both Epic of Gilgamesh and Enuma Elish are well known examples. Additionally, this theory explains the dissonance between the usual character of Dumuzi and his relationship with Inanna, known from countless love songs, and that presented in Inanna’s Descent. Katz argues that this presently purely theoretical “original” did not feature Dumuzi - Inanna was saved by Ninshubur’s intervention and Enki’s trick alone, and the addition of a replacement for her seems superficial given the presence of “water of life” in the myth. Inanna’s Descent wasn’t the only myth in which she appears which also served as explanation of Dumuzi’s death, as I already mentioned much earlier - in Inanna and Bilulu, for instance, she tracks down the killer instead (given the extreme level of violence, it would perhaps be fair to call the author a Sumerian Tarantino). At the same time, is somewhat unique in portraying Dumuzi’s death as being the result of his own shortcomings - something which probably indicates the compilers were more invested in Inanna than him, and that perhaps the goal was to merge as many different elements as possible into a coherent tale. As a small digression I should note this is not the most negative portrayal of Dumuzi in known sources: late enigmatic lists of so-called “Seven Conquered Enlils” (in which the name is used just as a title, something like “lord”) place Dumuzi in the company of various well known mythical antagonists, like Tiamat, Asag or Mummu, not to mention the mysterious cosmogonic figure Enmesharra, whose disposition is generally villainous too, as seen for example in the text Enlil and Namzitara. The change in focus from Inanna (or rather than equivalent of her) to Dumuzi only occurs in a very vague adaptation of Inanna’s Descent - the 1st millennium BCE Ishtar’s Descent. While Inanna’s Descent is known from nearly 50 copies, found anywhere from the major cities of Mesopotamia like Ur and Nippur to scribal schools located on the western periphery of the “cuneiform world,” the other myth has only a handful of them, all of exclusively Assyrian provenance. The myths are often conflated online, which leads to horrific misconceptions. Katz argues that the latter myth represents an attempt at state revival of Dumuzi’s (or, to be more accurate, Tammuz’s, as the name was rendered in Akkadian) cult undertaken by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which strikes me as a convincing argument. The change in focus is rather surprising, as the dying god par excellence, as noted by Berndt Alster, “did not belong to the leading deities in any period of Mesopotamian history” (unlike Ninshubur!). A huge difference between Inanna’s Descent and Ishtar’s Descent is the absence of Ninshubur. In the latter myth, Papsukkal, a male messenger deity associated with Anu (and, at an early stage, with the war god Zababa, at home in Kish, modern Tell al-Uhaymir in central Iraq), makes an appearance instead, introduced not as a personal attendant of the heroine, but simply as a servant of the “great gods” collectively. What’s also missing are any references to the instructions regarding mourning and petitioning other gods on her behalf. Evidently, whatever factors resulted in the portrayal of Ninshubur in Inanna’s Descent did not apply to Papsukkal. However, it’s important to stress that the very focus of Inanna’s Descent is different from that of Ishtar’s Descent. Dina Katz noted that while Ishtar’s Descent as a whole seems to be focused on the matter of very broadly understood fertility, “we cannot associate Inanna’s death and revival with procreation in nature nor with fertility in general,” contrary to what one can often read online. After all, fertility is a matter an agricultural deity would be much more concerned with, and Inanna’s Descent is ultimately not focused on Dumuzi and Geshtinanna, the only figures associated with agriculture in the original myth. At the time when the new myth had most likely been composed, Ninshubur was hardly a relevant figure, having seemingly lost her relevance at some point during the Kassite period, in the mid to late second millennium BCE. However, it’s not like the first millennium Ishtar (the myth does not associate her with a specific location like Assur, Nineveh or Arbela) didn’t have a variety of female courtiers who could’ve made an appearance in the myth in her stead. A particularly notable example is the well-attested incorporation of Hurrian Ninatta and Kulitta, a duo of goddesses sharing a rather close relation in myths with Shaushka, the “Ishtar of Subartu” as she was sometimes called, into Assyrian Ishtar cults. Coincidentally, there is no evidence for female scribes in the first millennium BCE, the time of the “translation’s” composition (I put that in quotation marks because while the text is often incorrectly labeled as such, it was actually, as outlined above, pretty much a new myth). Was this a factor in the evident change in sensibilities between Inanna’s Descent and Ishtar’s Descent? Hard to tell, but I personally would not rule it out. To sum up: ultimately, what is important for the subject of the article are two facts about Inanna’s Descent: 1. Ninshubur acts as one would expect a family member 2. Her bond with Inanna is uniquely close The evidence for the two points above does not start or end with Inanna’s Descent alone.

Beyond Inanna’s Descent: Ninshubur, sukkals and “wife goddesses”

Probably the strongest argument in favor of viewing Inanna and Ninshubur as uniquely close is the use of an uncommon synonym of the word sukkal, SAL.ḪUB2 (reading uncertain; the 2 should be subscript but tumblr doesn’t allow that, it seems), to refer to the latter. This term is very sparsely attested and only ever used to a handful of deities, exclusively sukkals, in all cases to indicate they are very closely associated with their divine “employers.” In addition to Ninshubur, it occurs for example in relation to Enlil’s sukkal Nuska, envisioned at times as a son of Enlil’s distant ancestors Enul and Ninul and a senior deity in his own right, and to Nabu, Marduk’s sukkal turned son turned pantheon head. I sadly have no access to an article which apparently decisively established its meaning - Vizir, concubine, entonnoir... Comment lire et comprendre le signe SAL.ḪUB2? by Antoine Cavigneaux and Frans Wiggermann - but thanks to the help of a friend I was able to learn a few months ago that, in their words, the authors conclude that it denotes a sukkal “who is dear or intimate.” This interpretation is presumably supported by the fact that in one of the few texts using this term (seemingly the one which is actually largely responsible for scholarly interest in establishing its meaning), Ninshubur is referred to as Inanna’s “beloved SAL.ḪUB2“ and appears among her family members - while her parents, brother, etc. are listed first, Ninshubur’s relation is seemingly more significant than that of in-laws in it, for what it’s worth. Other courtiers, like Nanaya, do not make an appearance. One more possible source is a curiosity from the Hittite capital from Hattusa (located near modern village Boğazkale in central Turkey), specifically a ritual related to the goddess Pinikir. This is (tragically) not the time and place to discuss Pinikir in detail, but it will suffice to say that she was understood as reasonably Inanna- or Ishtar-like. While the text in mention comes from a Hurro-Hittite milieu (Hittites, relatively “young” by the standards of Ancient Near East, viewed Hurrian culture as prestigious), it was written in Akkadian, and it’s primarily concerned with an Elamite goddess, making it uniquely cosmopolitan. Pinikir, whose name is spelled logographically as ISHTAR there, is invited to come alongside her family to receive offerings. She is described as the daughter of Nanna and Ningal and twin sister of Utu/Shamash; the other two figures invoked, Ea/Enki (addressed as “your [ie. Pinikir’s] creator”) and the goddess’ sukkal, instantly bring a variety of myths to mind (Descent, of course, but also Inanna and Enki and the less known Agushaya texts). The name of the sukkal, however, is Ilabrat, spelled syllabically. As far as I am aware, such a pairing is not attested anywhere else, and Ilabrat is generally speaking only Anu’s sukkal, unlike Ninshubur and even Papsukkal, who have multiple roles. While the researcher most involved in the study of this text, Gary Beckman, makes no such connection, I personally think it’s possible that a hypothetical forerunner to this late text featured Ninshubur. Beckman on linguistic grounds concludes Hurrians likely adopted Pinikir, and a variety of rituals connected to her and her usual associate, the enigmatic deity DINGIR.GE6 (“Goddess of the Night”; reading of the name remains unknown; once again, the numer should be subscript, once again), from a Mesopotamian intermediary and not directly from Elam. He proposes that the transfer happened during the period of well-attested intense Sumero-Hurrian contacts in the late third or early second millennium BCE (the text in mention, meanwhile, is no older than the 14th century BCE, I believe). This, coincidentally, was also a time of immense interest in Ninshubur, including theological texts presenting her as one of the “great gods,” side by side with Enlil, Ninlil, Inanna, Ninurta and the like. Perhaps much later on a Hittite scribe, not necessarily fully aware of Ninshubur’s existence (she was, after all, not really a deity of any relevance anymore in the late Bronze Age), worked with older Hurrian material which originally had Ninshubur in this role, but assumed the name is merely a logographic spelling of Ilabrat’s, a phenomenon attested in many locations in the Old Babylonian period? This is only my own, not necessarily valid, speculation, though. Another curiosity is a text in which Inanna calls Ninshubur “mother” - this, however, is not a statement of actual kinship, but rather of respect. Senior gods of the pantheon are often called “father” or “mother” by other deities regardless of actual parentage. Such statements aren’t even necessarily reflections of alternate genealogies or anything of that sort. A good example can be found even just in Inanna’s Descent: Ninshubur addresses Enlil, Nanna and Enki this way, even though none of them are attested as her actual father (and only Nanna was regarded as Inanna’s father between these 3). Presumably Ninshubur’s recurring participation in Inanna’s adventures, and her capability to appease her or to “soothe her heart” was worthy of such reverence.

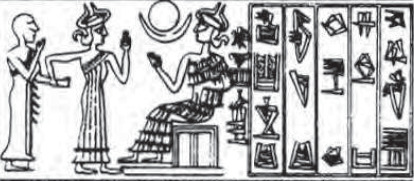

Impression of a cylinder seal depicting a mediating goddess, possibly Ninshubur as indicated by accompanying inscription (Goddesses in Context by J. M. Asher-Greve and W. G. Westenholz, p. 406; identified as such on p. 207)

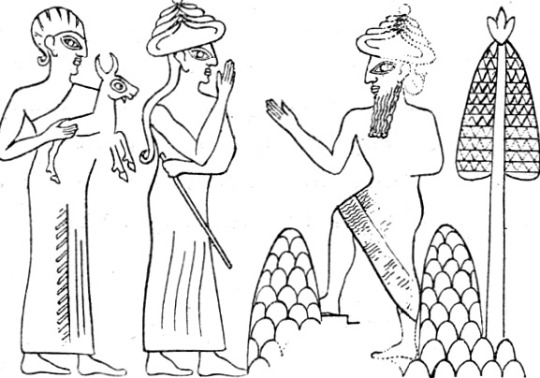

Impression of a cylinder seal possibly depicting Ninshubur (middle) interceding between governor of Lagash, Lugal-ushumgal, and the Akkadian king Shar-Kali-Sharri (wikimedia commons; goddess identified as Ninshubur in Goddesses in Context by J. M. Asher-Greve and W. G. Westenholz, p. 180) The closeness between Inanna and Ninshubur wasn’t limited to texts of mythical nature, and had a very real religious dimension too. Ninshubur was a common object of popular devotion, appearing in personal names, in seal inscriptions, and in other similar sources because she was believed to be capable of mediating with Inanna (and with other deities as well, on the account of being a divine messenger and diplomat). While a sukkal could act as a mediator in the cult of their master, most sukkals are deities with no personality, no individual role in myths and limited, if any popularity: for instance, Ishkur’s sukkal is simply the deified lightning, Nimgir. The difference between Ninshubur and Inanna and that which existed between most sukkals and their masters has been described by Frans Wiggermann as that between “command and execution” and “cause and effect.” To my knowledge very few other sukkals maintained the degree of popularity Ninshubur enjoyed, a notable exception being Nuska. Both of them were listed among the “great gods” every now and then: for example, in a text from the reign of the Third Dynasty of Ur (as I already noted, seemingly a period of prosperity for Ninshubur) both appear side by side with Enlil, Ninlil, Nanna, Inanna, Ninurta, Nergal and Utu - the creme de la creme of the pantheon. Ninshubur is also the only sukkal whose role I’ve seen compared to that of the “wife goddesses” (this is not a genuine scholarly term, I use it for simplicity’s sake). Julia M. Asher-Greve and Joan G. Westenholz specifically draw parallels between her role in Inanna’s cult with that played by Aya, the type specimen of the “wife goddesses” (her to-go epithet is quite literally “the bride,” kallatum) in the cult of Inanna’s solar twin. Of course, this does not indicate that she was ever seen as Inanna’s spouse - but it does at the very least show that it wouldn’t be entirely impossible to claim she was close to that status. While there is no known evidence for Ninshubur status actually moving between that of wife and sukkal when it comes to Inanna, it should be noted that she, as a matter of fact, does move between these two roles in one very specific case. In the area of Lagash and Girsu (modern Al-Hiba and Telloh in Iraq), especially in the third millennium BCE, Ninshubur was associated with Nergal (well, Meslamtaea, as he was typically called in the south early on in Mesopotamian history). As remarked by Wilfred G. Lambert, Ninshubur in this context appears to show up both as sukkal and, unexpectedly, as Nergal’s wife (Nergal’s love life seems to be a rather complex matter). This is rather unique as Ninshubur was generally viewed as unmarried. I don’t think Nergal is exactly similar to Inanna - though both deities share a warlike character - but this association, especially coupled with the modern observations regarding Ninshubur and Aya - does appear to support the idea that you could see Ninshubur likewise moving between status of sukkal and wife when it comes to Inanna. Especially taking into account that, as far as I am aware, it is only Inanna in relation to whom she gets to be a SAL.ḪUB2.

Ninshubur as the lesbian Enkidu?

One final point I’d like to make is that it is possible to make a number of comparisions between Ninshubur’s status to that of the only unambiguously attested gay love interest in Mesopotamian mythology, Enkidu.

A little discussed (outside scholarly circles, that is) aspect of the relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu which I’ve already mentioned early in the article is the fact that in the oldest sources do not yet present the latter as the “wild man” created to serve as a foil to Gilgamesh by the gods. Instead, he is the king’s courtier or servant, though a very close one - a status not too dissimilar from Ninshubur’s connection to Inanna in mythical context.

Obviously, the development from servant to cherished companion to lover was gradual, and presumably how the relationship was perceived varied too. Still, it’s worth stressing that while integral to Enkidu as a character in our modern perception, his origin story was actually a novelty compared to his position as Gilgamesh’s beloved, which predates the composition of a singular Epic of Gilgamesh. According to Andrew R. George, it’s possible that his newer “backstory” was meant to stress that to develop as a character Gilgamesh had to interact with a challenger completely from the outside of own sphere.

As a linguistic curiosity it’s worth mentioning that in the old standalone poems Enkidu’s position has been described in a few cases (for example in Gilgamesh and Akka or in Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld) with the poetic term shubur-a-ni, which shares its etymology with Ninshubur’s name. “Shubur” is a term referring to the land also known as Subartu - the areas north of Mesopotamia, inhabited chiefly by Hurrians, or “Subarians,” as Mespotamians called them. However, it also acquired the meaning of “servant.”

You may therefore ask if Ninshubur was the “Lady of Subartu” in origin, perhaps a “Subarian” equivalent of the god Martu/Amurru who embodied traits associated with “Westerners” (that is, Amorites from Syria) or was she always just “Lady of Servants” as Frans Wiggermann interprets her name? That’s hard to tell. Nothing prevents her from being both at once, as acknowledged even by the aforementioned author, especially taking into account that Hurrians were present in Mesopotamia on all levels of society in the 3rd millennium BCE already. Speculating about her origin, fascinating as it is, ultimately is not the concern here.

Another prominent similarity between Enkidu and Ninshubur is that based on a variety of texts the latter fulfilled an important, rather specific role in Inanna’s life, serving as a source of good advice, a characteristic also well attested for Enkidu. In Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld it is the loss of this advice that Gilgamesh laments after it turns out his friend cannot come back to life (a passage which George interprets as one of the early examples of the tradition according to which the two of them were in love). It should be noted that in Ninshubur’s case whether her advice was followed or not is a complicated matter - as we learn from one composition, one of Inanna’s abilities is knowing when to disregard both bad and good advice.

Finally, there is a less direct similarity. It is undeniable that Inanna and Gilgamesh both have heterosexual relationships with other characters, but Enkidu actually doesn’t in sources predating the development of his backstory, and I’ve already outlined Ninshubur’s marital status before. However, Inanna’s and Gilgamesh’s heterosexual relationships are not necessarily emphasized in compositions dealing with their adventures. It is instead their relationships with their respective “sidekicks” that commonly come to the forefront. In Gilgamesh’s and Enkidu’s case, this requires no examples, as various episodes from the Epic are well known. Similarly, in addition to her role in Inanna’s Descent, Ninshubur also appears in the myth Inanna and Enki, where she likewise defends the eponymous heroine from any harm which may befall her - in this case at the hands of Enki’s guards, rather than underworld demons. Ninshubur also praises Inanna after the daring scheme appears to work, leading to the transfer of me (divine powers) to Uruk.

Finally, there is the myth known as Agushaya or, in older literature, Ea and Saltu. While the relations between specific deities in it generally speaking reflects the Sumerian texts which formed the base of the scribal curriculum in the Old Babylonian period, it is presently only known from Akkadian versions. What makes it somewhat of a curiosity is the presence of Ninshubur, otherwise almost exclusively present in literary texts written in Sumerian - perhaps a lost Sumerian original awaits us somewhere out there. While the text uses the name Ishtar to refer to the protagonist, her relation with Ninshubur mirrors Inanna’s in the two texts above.

Saltu (“Strife”), mentioned in the title, is essentially a hostile copy of the heroine, formed by Ea out of dirt from underneath his fingers (note the similarity to Enki’s preferred mode of creation in Inanna’s Descent). Ninshubur apparently provides her mistress with information about this new adversary, whose very appearance fills her with fear. It has been argued by Benjamin R. Foster that a set of odd scribal errors which recur in the passage is meant to be a unique way to render agitated stuttering. Sadly, the middle of the text is not preserved, making it impossible to tell if Ninshubur played any other role in it beyond that.

Closing remarks

The examples above do not show that anyone actually viewed Inanna and Ninshubur as a couple, and it is not my goal to prove decisively that anyone did at the time of the discussed texts’ composition. While obviously there definitely were women attracted to other women in every time and place (how was it expressed and whether modern labels could be easily applied to them is a different matter), it is ultimately not really possible to determine whether they left behind any indirect traces in Mesopotamian textual sources, and how to locate them. The only point which I believe I’ve been able to prove above is that Ninshubur’s relationship with Inanna is uniquely close. As such, both this connection and Ninshubur’s character and broader role in Mesopotamian religion deserve more scholarly attention (can you believe there is no monograph on the concept of sukkal yet?) and more presence in the public perception of Mesopotamian mythology, and more specifically Inanna’s Descent I do personally think there are grounds to debate whether there is subtext in the discussed myths. Even if it was not intended by their authors nearly 4000 years ago, it is hard to deny that from a modern perspective the implications are certainly there. If nothing else, discussing this topic could possibly make the study of relationships between women in ancient texts - not necessarily romantic ones, mind you - more prominent than it is now, both among academics and laypeople. Additionally I think the discussed topic deserves exploration in fiction. As I’ve pointed out above, using the example of Gilgamesh and the reinterpretation of stories about him, certain aspects of myths could be emphasized or de-emphasized to match the expectations of new audiences, without the core of the story being lost. I think this still holds true. Ultimately what I want to say is not “Ninshubur is clearly gay in Inanna’s Descent,” it’s “wouldn’t it be interesting to consider if she was, and whether the ancient sources make it viable?” And that is the question I would like to leave you, the reader, with.

Bibliography

J. M. Asher-Greve, J. G. Westenholz, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources

B. Alster, Inanna Repenting: The Conclusion of Inanna’s Descent - can’t vouch for the site this is hosted on, but it was originally published in a credible journal

B. Alster, Tammuz(/Dumuzi) (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry)

G. Beckman, Babyloniaca Hethitica: The "babilili-Ritual" from Bogazköy (CTH 718)

G. Beckman, Gilgamesh in Hatti

G. Beckman, The Goddess Pirinkir and Her Ritual from Ḫattuša (CTH 644)

G. Beckman, When Heroes Love: The Ambiguity of Eros in the Stories of Gilgamesh and David (review)

J. Black, Ning̃išzida and Ninazimua

A. Cavigneaux, F. A. M. Wiggermann, Vizir, concubine, entonnoir... Comment lire et comprendre le signe SAL.ḪUB2?

M. Civil, Enlil and Ninlil: The Marriage of Sud

B. Dedovic, "Inanna's Descent to the Netherworld": A centennial survey of scholarship, artifacts, and translations

B. R. Foster, Ea and Saltu

A. Gadotti, Portraits of the Feminine in Sumerian Literature

A. George, The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts

D. Katz, How Dumuzi Became Inanna's Victim: On the Formation of "Inanna's Descent"

D. Katz, Inanna's Descent and Undressing the Dead as a divine law

D. Katz, Myth and Ritual through Tradition and Innovation

D. Katz, Sumerian Funerary Rituals in Context

S. N. Kramer, Two British Museum iršemma "Catalogues"

W. G. Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths - sadly not open access

W. G. Lambert, Introductory Considerations

A. Löhnert, Scribes and singers of Emesal lamentations in ancient Mesopotamia in the second millennium BCE

N. N. May, Female Scholars in Mesopotamia?

P. Michalowski, Emesal (Sumerian dialect) (The Encyclopedia of Ancient History entry)

P. Michalowski, Literacy in Early States: A Mesopotamianist Perspective

S. Nowicki, Women and References to Women in Mesopotamian Royal Inscriptions. An Overview from the Early Dynastic to the End of Ur III Period

J. Peterson, The Banishment of Inana

J. Peterson, UET 6/1, 74, the Hymnic Introduction of a Sumerian Letter-Prayer to Ninšubur (ZA 106)

J. Pfitzner, Ninĝišzida and Ninazimua, Nippur version l. 104 (=Ur version l. 40)

P. Pongratz-Leisten, Comments on the Translatability of Divinity: Cultic and Theological Responses to the Presence of the Other in the Ancient near East

E. Robson, Gendered literacy and numeracy in the Sumerian literary corpus

G. J. Selz, Female Sages in the Sumerian Tradition of Mesopotamia - careful with the final few paragraphs: the author is a bit too enthusiastic about the so-called “Helsinki school” which sees Mesopotamia as little more than source of dubious evidence for greater than in reality antiquity of specific currents in early Christianity and in broader gnostic tradition; for a criticism of the core ideas of the Helsinki school see this review by J. Cooper

T. Sharlach, Foreign Influences on the Religion of the Ur III Court

M. P. Streck, Nusku (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry)

A. G. Ventura, Review of "Women's Writing in Ancient Mesopotamia. An Anthology of the Earliest Female Authors" (Charles Halton & Saana Svärd, 2018)

M. Viano, The Reception of Sumerian Literature in the Western Periphery

G. Whittaker, Linguistic Anthropology and the Study of Emesal as (a) Women's Language - note that some of Whittaker’s other writing on Sumerian language is dubious at best (especially his quest for an “Indo-European substrate” in it; for overview of theories about substrates in Sumerian and explanation why they are faulty see On the Alleged "Pre-Sumerian Substratum" by G. Rubio); I am merely using this article as a point of reference for information about Enheduanna’s writing

F. A. M. Wiggermann, An Unrecognized Synonym of Sumerian Sukkal

F. A. M. Wiggermann, Nergal A. Philological (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry)

F. A. M. Wiggermann, Nin-šubur (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry)

F. A. M. Wiggermann, Sexuality A. In Mesopotamia (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) - do not take it at face value though, at least one of the sources is pretty much a nightmare, make sure to read a critical review by A. R. George

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everyone talks about the Song of Songs, but y'all are sleeping on the Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ladies. Gentlemen. Enbies. Nascent Armoured Core Six puppygirls. We have a tragedy on our hands. A category five code red containment breach.

It has come to my attention that there are people in the notes of this poll trying to use the Epic of Gilgamesh to justify Enkidu out-heading Ishtar.

The Epic of Gilgamesh. The story about, among other things, how arrogance and hubris against the gods will only lead to disaster and true wisdom is found in accepting that humans can never aspire to the domain of the divine. The story that literally uses Enkidu’s death to support that message.

We need to nip this in the bud. It’s kind of like citing Fate/Stay Night to justify saying that being a hero is lame and you shouldn’t want to save anyone. Neither Archer nor Gil are meant to be right. It’s pretty foundational to the entire story.

Furthermore, using the Epic itself as a reference point for understanding anything about Ishtar is fraught with flaws. The version Fate/Grand Order and Fate/Strange Fake rely on—the Standard Babylonian Version—presents a view of Ishtar so dissimilar to any other representation across any part of her mythology that scholarship has suggested the Epic's compilers were reflecting the existence of "anti-Ištar sentiment at that time" (Beaulieu, 2003). In fact, the original Sumerian version of Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven has nothing to do with romance, but is instead Inanna's attempt to stop Gilgamesh rampaging as he pleased through her temple in Uruk.

Beyond this, it's one piece of mythology out of dozens that feature her. I wrote an entire essay on the subject of Ishtar's sexual skills as attested to in her mythology for this tournament and feel obligated to note that in it I referenced twenty-nine different texts from the relevant time periods, including myths, prayers, kingship inscriptions, and the like... and I could have cited more if I'd had the time.

The Epic is a good story—it's a great story!—but it is exactly that: a story. Pull open the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL) and read through the courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi (did you know there's a section in it called the Song of the Lettuce where Inanna refers to Dumuzi as her "well-watered lettuce" among a whole series of funky pet names?), or myths like Inanna and Enki or Inanna and Ebiḫ to get a sense of what she is actually like in stories that aren't, arguably, deliberately biased against her.

If you do, you might come to understand how I managed to put down five thousand words about Ishtar's immaculate head game and why I am so normal about her to begin with.

(I would like to be clear that I don't write this to deny Enkidu's sexual skills; as you may already know, a recent discovery revealed that Enkidu actually joins Ereshkigal in the "fourteen days and nights of sex in one myth" club. Rather, I seek, as always, to correct some significant misconceptions about Ishtar that propagate throughout the fandom due to Fate's take on her and the fame of the Epic itself.)

Side D, Round 4 (Match 2)

#i am very normal about inanna-ishtar#nasuverse head game tourney#inanna-ishtar#enkidu would beat almost anyone else in this contest#but ishtar? absolutely the worst possible match-up#it's not just that her skills are superior in this area it's that the bad blood between them#would mean she would go out of her way to make sure enkidu lost#and that is a very scary thing to be on the opposite side of: just ask mount ebih

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi"

"Dumuzi waited expectantly. Inanna opened the door for him.Inside the house she shone before him. Like the light of the moon. Dumuzi looked at her joyously. He pressed his neck close against hers. He kissed her.

Inanna spoke:—What I tell you, Let the singer weave into song. What I tell you, Let it flow from ear to mouth, Let it pass from old to young: My vulva, the horn, The Boat of Heaven, Is full of eagerness like the young moon. My untilled land lies fallow. As for me, Inanna,Who will plow my vulva? Who will plow my high field?Who will plow my wet ground? As for me, the young woman, Who will plow my vulva? Who will station the ox there? Who will plow my vulva? Dumuzi replied:—Great Lady, the king will plow your vulva. I, Dumuzi the King, will plow your vulva. Inanna:—Then plow my vulva, man of my heart! Plow my vulva! At the king's lap stood the rising cedar. Plants grew high by their side. Grains grew high by their side. Gardens flourished luxuriantly.

Inanna sang:—He has sprouted; he has burgeoned; He is lettuce planted by the water. He is the one my womb loves best. My well-stocked garden of the plain, My barley growing high in its furrow, My apple tree which bears fruit up to its crown, He is lettuce planted by the water. My honey-man, my honey-man sweetens me always. My lord, the honey-man of the gods, He is the one my womb loves best"

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aphrodite April Day 10

Share a poem that reminds you of Aphrodite.

The poem selected comes from Aphrodite’s Mesopotamian ancestor, Inanna, Queen of Heaven

‘My vulva, the horn,

The Boat of Heaven,

Is full of eagerness like the young moon.

My untilled land lies fallow.

As for me, Inanna,

Who will plow my vulva?

Who will plow my high field?

Who will plough my wet ground?’

Dumuzi replied: ‘Great Lady, the king will

plough your vulva

I, Dumuzi, the King, will plough your vulva.’

Inanna: ‘Then plough my vulva, man of my heart!

Plough my vulva!’ *

* “The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi’, c. 2500 BCE, trans Wolkstein and Kramer

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who will warp it for me ?

I am unforgiving to myself mostly, fearful at every wrong move I make, but more generous (sometimes) with others. As I spoke the last lines of The Courtship of Inanna & Dumuzi, my own shepherd, my blossom-bearer of coarse cloth and sweet cream, my father-mother, spoke to his cousin on Facetime and fucked up my promo concert.

This morning I ‘m so close to where I want to be infact I a m here, with a 97.7 temperature.

Can’t help but think I’m supposed to be writing something more profound but all the signs point to trusting my body, my vessel. I mean what’s more profound than knowing how hot I am.

I burnt the pizza last night my gram keeps inrushing me, spilling on my shirt and burning dinner. food things. eat it, it’s burnt.

a strange sort of nourishment a thwarted care to miss yr mouth - to move so quickly to singe yr offering to denigrate what you have to give Grammy, back soon. Grammy, “crazy.”

Who made my money? Gram and Gramps? My mother? Her father? Where’d it come from My dad made our money sneaking cocaine home in his asshole back when it was all pure He used it for a house House-poor.

My mom made our money teaching herself real estate being smarter than the system Finding a way to be closer to us To give us more, and more, and more To serve directly instead of through an intermediary, a faux-Sukkal-man-godhead-business

Sumer had problems in the years 2000s too What I wanna know is, who made it out alive When Uruk was ruined & Inanna driven down, permanently, and up, permanently did anyone make it out alive will any of us make it out alive

Once there was marshland steppe canebreak now there is nasturtiumslope dirtcliff wasteland

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m pretty sure the sexy milky business is from the poem The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi.

The Sumerians knew what was important.

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

‘My vulva, the horn, The Boat of Heaven, Is full of eagerness like the young moon. My untilled land lies fallow.As for me, Inanna, Who will plow my vulva? Who will plow my high field? Who will plough my wet ground?’Dumuzi replied: ‘Great Lady, the king willI, Dumuzi, the King, will plough your vulva.’ Inanna: ‘Then plough my vulva, man of my heart! Plough my vulva!’ ** “The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi’, c. 2500 BCE, trans Wolkstein and Kramer

0 notes

Text

Hinduism is convoluted in its approach towards Goddesses. The three most powerful beings of the Universe, Bramha, Vishnu & Maheshwar are all male. Even Goddess Parvati or Duga is “created” by the other Gods (all male) by focusing their powers.

But the concept is deeply misleading. It replaced the earlier mistaken belief that women hold the sole power to generate life with the idea that only men have procreative power. The consequence of accepting the seed metaphor was monumental. It transformed women from the powerful creators into the soil in which men plant their seed. As men were raised to the exalted status of authors of life (giving them authority), women were reduced to, well, dirt. In most cultures, they were for all practical purposes seen as property — objects that had few rights and no real agency. (It is not a large leap from there to a place where women do not get to choose whether they keep a pregnancy: Thou shalt not pull up what man has planted.)When procreative power was reconceived as male, it followed that the ultimate creative power must also be male. And, if God is male, surely human males are closer to “Him” than are human females. The toxic fruit that grew from male monotheism was and is misogyny

This seed metaphor for copulation and procreation seemed so obvious it appears to have been adopted in most places where the plow was introduced. “Who will plow my vulva? … Who will plow my wet ground?” asks the goddess Inanna in “The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi,” a Mesopotamian text from about 1750 BCE. “I, Dumuzi the King, will plow your vulva,” is the eager male response. The name of the consort of the Hindu god Rama is Sita, which means “furrow.”“Your wives are a place of sowing of seed for you,” proclaims the second Surah of the Koran, “so come to your place of cultivation however you wish.” In another translation, this line is rendered: “Your wives are as fields for you. You may enter your fields from any place you want.” (The metaphor lives on, appearing across modern cultures, too. One example: The protagonist of “Raising Arizona” says a “doctor explained that her insides were a rocky place where my seed could find no purchase.”)

unattached women were seen as sexual predators and fearful yoginis who could consume men, unless they were restrained by marriage and maternity. This may explain the cultural fear of independent women.

0 notes

Text

Please watch the following video before writing the assignment: https://youtu.b

Please watch the following video before writing the assignment: https://youtu.b

Please watch the following video before writing the assignment:

Pick one myth from Unit 3. These include any one of the following: “The Fire Goddess,” from Hawaiian mythology; “White Buffalo Calf Woman,” from Brule/Lakota Sioux mythology; “The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi,” from ancient Sumerian mythology; “A Taste of Earth,”…

View On WordPress

0 notes