#the agro destroyed the amazon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A few days ago there was a whole discussion online in Brazil about how climate change anxiety was “a white person problem”. This is Brazil right now, as illegal fires were set in the countryside of the state of São Paulo.

The sun is red. The sun is fucking red. The state is literally burning. The city of São Paulo has an orange sky made by the toxic fog coming from the fires. Other states in the region (the one that I live, by the way) watched as this toxic fog came to our towns. Winds, a dense cloud of pollution, the air almost ashy. It’s toxic. The government isn’t doing anything to alert or prepare the citizens, the media is hiding everything because these were intentional fires set to support the agro business in Brazil.

I’m having problems breathing prior to these fires because of how the air is so dry in Brazil, caused by the intense pollution and deforestation/logging. It all got worse since this morning, as we watched the heavy grey clouds coming to us. There is literally no information in how to deal with this, and no punishment for the criminals - hilarious, until you think most of the powerful people in the agro business are also entangled with the media/government. “The agro is pop, the agro is tech, the agro is everything”, is what we spent decades listening on the tv, and now we are ripping the consequences of this shit. Ribeirão Preto, a city in the state of São Paulo, an “agro city”, is invisible under the fog. But the agro is pop, right?

My friend is waking up in the middle of the night not being able to breathe, I have friends having anxiety attacks over the consequences of this and I can assure you, this is not the first or last time this had happened. During Bolsonaro’s government, the agro did a “fire day”, where multiple fires were set in so many places that became almost impossible to track the people responsible for it or to get the fires out. The laws passed under Bolsonaro’s, and brazilian law since… ever, has a tricky way of letting these criminals away. We need harsher punishment, and Lula re-elected himself under a “green” campaign/government, holding hands with indigenous people as he rode up the Alvorada’s Palace. The indigenous people are the only community trying to protect us from this shit and the government used them, and continue to use them, to advance their political party while doing nothing when acts like these happens.

I’m so tired of this shit. Mere months ago a whole state in Brazil was under water because of the consequences of climate change. I’m so fucking exhausted of we labbing these problems/anxiety as “white people problem”. You say this in a third world country where we are eating shit from the consequences of first world countries who developed and continue to develop themselves by burning our Earth. The country should have stopped when Rio Grande do Sul was under water and the country should have stopped days ago when the fires started to spread.

I’m so tired and I’m so sad and I have no words. I hate it here. I really, truly hate it here.

#enfia o agro no meio do seu CU#brazil#brasil#and if someone tells me to move countries i will actually commit a hate crime#illegal fires#the agro is destroying this country#the agro destroyed the amazon#and no people the agro doesnt produce anything for brazilians#it’s all so they can export to foreign countries#we are burning brasil for the sake of exporting shit to fucking europe#all while brazilians are starving#and why does china needs so much soybean ANYWAY#in quote because it helps your green development???#your green development is killing my country you assholes#all of this to (and i’m not kidding) feed pigs#AND PRODUCE OIL#AAAAAAAAAASAS

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The war on Indigenous rights in Brazil is intensifying

The Bolsonaro government is using legislation and the courts to try to deprive indigenous people of their rights

[Image description: FUNAI plaque from the indigenous land reserve in the Amazon, Pará, Brazil; it reads “PROTECTED LAND; by Federal Government, Justice Ministry, and National Indian Foundation; access denied to stranger people according to the Federal Constitution, Law 6001/73, and Criminal Code.”]

Indigenous peoples in Brazil are under siege by the Brazilian government, which is waging war on two fronts. New legislation in the form of a bill known as PL 490/2007 threatens to cancel legal protections for Indigenous territories, while a landmark Supreme Court case over the so-called marco temporal, a 1988 cut-off date that threatens to strip the Indigenous peoples of existing land rights. Though not as visible as the effects of the fires that destroyed large swathes of the Amazon forest in 2019 and 2020, were the legislation to pass and the legal ruling to go against the Indigenous peoples, the consequences will be catastrophic.

On 23 June, a committee in the lower house of the Brazilian parliament approved a draft of PL 490/2007, which will now be put to the vote. If lawmakers pass the bill, it will end Indigenous peoples’ right to be consulted on the use of their land by non-Indigenous peoples. The government could allow unrestricted access to natural resources, including extractive activities such as mining and commercial agriculture.

The bill, which has been under consideration since 2007, was proposed by the country’s powerful agro-business lobby. It is a clear violation of the existing protections afforded to Indigenous populations under the Brazilian Federal Constitution and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Its motivation is obvious: to allow greater loggers, miners and cattle ranchers access to vast tracts of land in the Amazon, which is home to the so-called “lungs of the planet”, the single largest remaining tropical rainforest in the world, and houses at least 10% of the known biodiversity. As they have for more than 500 years, the Indigenous peoples of Brazil are once again struggling to maintain their way of life. They are fighting to defend their constitutionally mandated ancestral lands in much the way they once faced down Portuguese colonizers, loggers, and illegal gold miners.

Meanwhile, a challenge looms in Brazil’s Supreme Court. On 30 June, it will review the landmark case that could either affirm Indigenous land rights or set a precedent by stripping territorial rights that were not officially recognized when the Brazilian Constitution was approved on 5 October 1988. The 1988 Constitution, which restored democracy to Brazil after 20 years of military dictatorship, guarantees certain fundamental rights to Indigenous peoples, not least the right to pursue their own cultural lifestyle without pressure to assimilate. Article 231 of the Constitution acknowledges that Indigenous peoples are the original inhabitants of Brazil and says that “the lands traditionally occupied by the Indigenous peoples are destined for their permanent possession, and they are responsible for the exclusive enjoyment of the riches of the soil, rivers and lakes existing in them.” But Brazil’s federal Indigenous affairs agency, FUNAI, has been slow to uphold those rights and the Indigenous peoples and their allies have continued to demand that the federal government enforce them.

Continue reading.

#brazil#brazilian politics#politics#environmentalism#environmental justice#indigenous rights#bill 490#mod nise da silveira

133 notes

·

View notes

Photo

19th January >> (Zenit.org @zenitenglish) Pope Francis’ Address to Indigenous People of Amazon Region in Peru: ‘I wanted to come to share your challenges and reaffirm with you a whole-hearted option for the defence of life, the defence of the earth and the defence of cultures’ (Photo ~ Pope Francis © Vatican Media) Below is the Vatican provided text of Pope Francis’ address during his meeting with indigenous people of the Amazon region in the “Coliseo Regional Madre de Dios”: *** Dear Brothers and Sisters, Here with you, I feel welling up within me the song of Saint Francis: “Praise be to you, my Lord!” Yes, praise be to you for the opportunity you have given us in this encounter. Thank you, Bishop David Martínez de Aguirre Guinea, Hector, Yésica and María Luisa, for your words of welcome and for your witness talks. In you, I would like to thank and greet all the inhabitants of Amazonia. I see that you come from the different native peoples of Amazonia: Harakbut, Esse-ejas, Matsiguenkas, Yines, Shipibos, Asháninkas. Yaneshas, Kakintes, Nahuas, Yaminahuas, Juni Kuin, Madijá, Manchineris, Kukamas, Kandozi, Quichuas, Huitotos, Shawis, Achuar, Boras, Awajún, Wampís, and others. I also see that among us are peoples from the Andes who came to the forest and became Amazonians. I have greatly looked forward to this meeting. Thank you for being here and for helping me to see closer up, in your faces, the reflection of this land. It is a diverse face, one of infinite variety and enormous biological, cultural and spiritual richness. Those of us who do not live in these lands need your wisdom and knowledge to enable us to enter into, without destroying, the treasures that this region holds. And to hear an echo of the words that the Lord spoke to Moses: “Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground” (Ex 3:5). Allow me to say once again: “Praise to you, Lord, for your marvellous handiwork in your Amazonian peoples and for all the biodiversity that these lands embrace! This song of praise is cut short when we learn about, and see, the deep wounds that Amazonia and its peoples bear. I wanted to come to visit you and listen to you, so that we can stand together, in the heart of the Church, and share your challenges and reaffirm with you a whole-hearted option for the defence of life, the defence of the earth and the defence of cultures. The native Amazonian peoples have probably never been so threatened on their own lands as they are at present. Amazonia is being disputed on various fronts. On the one hand, there is neo-extractivism and the pressure being exerted by great business interests that want to lay hands on its petroleum, gas, lumber, gold and forms of agro-industrial monocultivation. On the other hand, its lands are being threatened by the distortion of certain policies aimed at the “conservation” of nature without taking into account the men and women, specifically you, my Amazonian brothers and sisters, who inhabit it. We know of movements that, under the guise of preserving the forest, hoard great expanses of woodland and negotiate with them, leading to situations of oppression for the native peoples; as a result, they lose access to the land and its natural resources. These problems strangle her peoples and provoke the migration of the young due to the lack of local alternatives. We have to break with the historical paradigm that views Amazonia as an inexhaustible source of supplies for other countries without concern for its inhabitants. I consider it essential to begin creating institutional expressions of respect, recognition and dialogue with the native peoples, acknowledging and recovering their native cultures, languages, traditions, rights and spirituality. An intercultural dialogue in which you yourselves will be “the principal dialogue partners, especially when large projects affecting your land are proposed”.[1] Recognition and dialogue will be the best way to transform relationships whose history is marked by exclusion and discrimination. At the same time, it is right to acknowledge the existence of promising initiatives coming from your own communities and organizations, which advocate that the native peoples and communities themselves be the guardians of the woodlands. The resources that conservation practices generate would then revert to benefit your families, improve your living conditions and promote health and education in your communities. This form of “doing good” is in harmony with the practices of “good living” found in the wisdom of our peoples. Allow me to state that if, for some, you are viewed as an obstacle or a hindrance, the fact is your lives cry out against a style of life that is oblivious to its own real cost. You are a living memory of the mission that God has entrusted to us all: the protection of our common home. The defence of the earth has no other purpose than the defence of life. We know of the suffering caused for some of you by emissions of hydrocarbons, which gravely threaten the lives of your families and contaminate your natural environment. Along the same lines, there exists another devastating assault on life linked to this environmental contamination favoured by illegal mining. I am speaking of human trafficking: slave labour and sexual abuse. Violence against adolescents and against women cries out to heaven. “I have always been distressed at the lot of those who are victims of various kinds of human trafficking. How I wish that all of us would hear God’s cry, ‘Where is your brother?’ (Gen 4:9). Where is your brother or sister who is enslaved? Let us not look the other way. There is greater complicity than we think. This issue involves everyone!”[2] How can we fail to remember Saint Turibius, who stated with dismay in the Third Council of Lima “that not only in times past were great wrongs and acts of coercion done to these poor people, but in our own time many seek to do the same…” (Session III, c. 3). Sadly, five centuries later, these words remain timely. The prophetic words of those men of faith – as Hector and Yèsica reminded us – are the cry of this people, which is often silenced or not allowed to speak. That prophecy must remain alive in our Church, which will never stop pleading for the outcast and those who suffer. This concern gives rise to our basic option for the life of the most defenceless. I am thinking of the peoples referred to as “Indigenous Peoples in Voluntary Isolation” (PIAV). We know that they are the most vulnerable of the vulnerable. Their primitive lifestyle made them isolated even from their own ethnic groups; they went into seclusion in the most inaccessible reaches of the forest in order to live in freedom. Continue to defend these most vulnerable of our brothers and sisters. Their presence reminds us that we cannot use goods meant for all as consumerist greed dictates. Limits have to be set that can help preserve us from all plans for a massive destruction of the habitat that makes us who we are. The recognition of these people – who can never be considered a minority, but rather authentic dialogue partners – as of all the native peoples, reminds us that we are not the absolute owners of creation. We need urgently to appreciate the essential contribution that they bring to society as a whole, and not reduce their cultures to an idealized image of a natural state, much less a kind of museum of a bygone way of life. Their cosmic vision and their wisdom, have much to teach those of us who are not part of their culture. All our efforts to improve the lives of the Amazonian peoples will prove too little.[3] The culture of our peoples is a sign of life. Amazonia is not only a reserve of biodiversity but also a cultural reserve that must be preserved in the face of the new forms of colonialism. The family is, and always has been, the social institution that has most contributed to keeping our cultures alive. In moments of past crisis, in the face of various forms of imperialism, the families of the original peoples have been the best defence of life. Special care is demanded of us, lest we allow ourselves to be ensnared by ideological forms of colonialism, disguised as progress, that slowly but surely dissipate cultural identities and establish a uniform, single… and weak way of thinking. Listen to the elderly. They possess a wisdom that puts them in contact with the transcendent and makes them see what is essential in life. Let us not forget that “the disappearance of a culture can be just as serious, or even more serious, than the disappearance of a species of plant or animal”.[4] The one way for cultures not to disappear is for them to keep alive and in constant movement. How important is what Yésica and Hector told us: “We want our children to study, but we don’t want the school to erase our traditions, our languages; we don’t want to forget our ancestral wisdom!” Education helps us to build bridges and to create a culture of encounter. Schooling and education for the native peoples must be a priority and commitment of the state: an integrated and inculturated commitment that recognizes, respects and integrates their ancestral wisdom as a treasure belonging to the whole nation, as María Luzmila made clear to us. I ask my brother bishops to continue, as they are doing even in the remotest places in the forest, to encourage intercultural and bilingual education in the schools, in institutions of teacher training, and in the universities.[5] I express my appreciation of the initiatives that the Amazonian Church in Peru helps carry out in favour of the native peoples. These include schools, student residences, centres of research and development like the José Pio Aza Cultural Centre, CAAAP and CETA, and new and important intercultural projects like NOPOKI, aimed expressly at training young people from the different ethnic groups of our Amazonia. I likewise support all those young men and women of the native peoples who are trying to create from their own standpoint a new anthropology, and working to reinterpret the history of their peoples from their own perspective. I also encourage those who through art, literature, craftsmanship and music show the world your worldview and your cultural richness. Much has been written and spoken about you.It is good that you are now the ones to define yourselves and show us your identity. We need to listen to you. How many missionaries, men and women, have devoted themselves to your peoples and defended your cultures! They did so inspired by the Gospel. Christ himself took flesh in a culture, the Jewish culture, and from it, he gave us himself as a source of newness for all peoples, in such a way that each, in its own deepest identity, feels itself affirmed in him. Do not yield to those attempts to uproot the Catholic faith from your peoples.[6] Each culture and each worldview that receives the Gospel enriches the Church by showing a new aspect of Christ’s face. The Church is not alien to your problems and your lives, she does not want to be aloof from your way of life and organization. We need the native peoples to shape the culture of the local churches in Amazonia. Help your bishops, and the men and women missionaries, to be one with you, and in this way, by an inclusive dialogue, to shape a Church with an Amazonian face, a Church with a native face. In this spirit, I have convoked a Synod for Amazonia in 2019. I trust in your peoples’ capacity for resilience and your ability to respond to these difficult times in which you live. You have shown this at different critical moments in your history, with your contributions and with your differentiated vision of human relations, with the natural environment and your way of living the faith. I pray for you, for this land blessed by God, and I ask you, please, not to forget to pray for me. Many thanks! Tinkunakama (Quechua: Until we meet again) _________________________ [1] Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’, 146. [2] Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, 211. [3] We hear disturbing reports about the spread of certain diseases. The silence is alarming and deadly. By remaining silent, we fail to work for prevention, especially among adolescents and young people, and to ensure treatment, thus condemning the sick to a cruel ostracism. We call upon states to implement policies of intercultural health that take into account the experience and the worldview of the native people, training professionals from each ethnic group who can deal with the disease in the context of their own worldview. As I pointed out in Laudato Si’, once again we need to speak out against the pressure applied to certain countries by international organizations that promote reproductive policies favouring infertility. These are particularly directed at the native peoples. We know too that the practice of sterilizing women, at times without their knowledge, continues to be promoted. [4] Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’, 145. [5] Cf. FIFTH GENERAL CONFERENCE OF THE LATIN AMERICA AND CARIBBEAN BISHOPS, Aparecida Document (29 June 2007), 530. [6] Cf. ibid., 531 [00062-EN.01] [ [Original text: Spanish] [Vatican-provided text of Pope’s prepared speech] © Libreria Editrice Vaticana

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Amazon Biome

The biome occupies an area of 4,196 943 km², which represents more than 40% of the country and consists mostly of tropical forest. The Amazon is in states of Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Pará and Roraima, and certain regions of Maranhão, Mato Grosso, Rondônia and Tocantins states. The Amazon is made up of different ecosystems and dense forests, deciduous forests, flooded fields, meadows, grassands mountain refuges, and pioneer formations.

Even thought this biome is the most preserved, about 16% of his area has been destroyed, which is equivalent to two times the area of São Paulo state.

Desforestation, fires, mining, biopiracy and agro-pasture represent the main enviromental problems in the Amazon biome. All these actions are responsible for severe climate changes on the planet – like global warming.

The amazon is considered a great atmosphere “cooler” and it is the world’s largest biodiversity shelter. Some research indicates that in the Amazon there are about thirty million species of animals.

Fonte: <http://www.ibflorestas.org.br/en/amazon-biome.html>

0 notes

Text

It's not just Brazil's Amazon - Bolivia's vital forests are burning out of control, too

https://sciencespies.com/environment/its-not-just-brazils-amazon-bolivias-vital-forests-are-burning-out-of-control-too/

It's not just Brazil's Amazon - Bolivia's vital forests are burning out of control, too

Up to 800,000 hectares of the unique Chiquitano forest were burned to the ground in Bolivia between August 18 and August 23. That’s more forest than is usually destroyed across the country in two years.

Experts say that it will take at least two centuries to repair the ecological damage done by the fires, while at least 500 species are said to be at risk from the flames.

The Chiquitano dry forest in Bolivia was the largest healthy tropical dry forest in the world. It’s now unclear whether it will retain that status. The forest is home to Indigenous peoples as well as iconic wildlife such as jaguars, giant armadillos, and tapirs. Some species in the Chiquitano are found nowhere else on Earth.

Distressing photographs and videos from the area show many animals have burned to death in the recent fires.

Bolivia just lost half a million ha of the unique Chiquitano forest in 5 days. Media is focusing in Brazil, but we need press attention so that the government acts and asks for inter. help. Please report@BBCWorld @guardIaneco @georgeMonbiot @dpcarrington https://t.co/nPmCpANPtQ

— Alfredo Romero (@Alf_RomeroM) August 21, 2019

The burnt region also encompasses farmland and towns, with thousands of people evacuated and many more affected by the smoke.

Food and water are being sent to the region, while children are being kept home from school in many districts where the air pollution is double what is considered extreme. Many families are still without drinking water.

While the media has focused on Brazil, Bolivians are asking the world to notice their unfolding tragedy – and to send help in combating the flames.

It’s thought that the fires were started deliberately to clear the land for farming, but quickly got out of control. The perpetrators aren’t known, but Bolivian President Evo Morales has justified people starting fires, saying: “If small families don’t set fires, what are they going to live on?”

The disaster comes just a month after Morales announced a new “supreme decree” aimed at increasing beef production for export.

Twenty-one civil society organisations are calling for the repeal of this decree, arguing that it has helped cause the fires and violates Bolivia’s environmental laws. Government officials say that fire setting is a normal activity at this time of year and isn’t linked to the decree.

Morales has repeatedly said that international help isn’t needed, despite having sent just three helicopters to tackle the raging fires. He argued that the fires are dying out in some areas – although they continue to burn in others and have now reached Bolivia’s largest city, Santa Cruz de la Sierra.

Many say that the fires could have been contained far sooner with international help, as videos show volunteers trying to beat back the fires with branches.

As the fires worsened, people gathered to protest in Santa Cruz state. Chanting “we want your help“, they complained that the smoke was so bad they were struggling to breathe. They want Morales to request international aid to fight the fires. While firefighters and volunteers struggle to tackle the blaze in 55℃ heat, Bolivians have set up a fundraiser to tackle the fires themselves.

A fortnight after the fires began, a supertanker aeroplane of water arrived, hired from the US. But if the reactions to the president’s announcement on Twitter are anything to go by, many Bolivians think this is too little, too late. Morales is fighting a general election and has faced criticism for staying on the campaign trail while the fires spread.

Thread on the current fires in #Bolivia:

Fires have been used to expand agro-cattle area before, but our current catastrophe stems from the government authorizing further fires on FOREST lands in a new alliance with private sectors who wanted these lands.https://t.co/lfS7btxcNW pic.twitter.com/Ho4AuFm1xZ

— Jhanisse V. Daza (@JhanisseVDaza) August 20, 2019

Some Indigenous leaders are asking for a trial to determine responsibility for the fires, and the response to them. Alex Villca, an Indigenous leader and spokesperson, said:

It is President Evo Morales who should be held accountable. What are these accountabilities going to be? A trial of responsibilities for this number of events that are occurring in the country, this number of violations of Indigenous peoples and also the rights of Mother Nature.

President Morales came to power in Bolivia in 2006, on a platform of socialism, Indigenous rights, and environmental protection. He passed the famous “Law of the Rights of Mother Earth” in 2010, which placed the intrinsic value of nature alongside that of humans.

His environmental rhetoric has been strong but his policies have been contradictory. Morales has approved widespread deforestation, as well as roads and gas exploration in national parks.

While the fires in the Chiquitano have dominated the media within the country, hundreds more rage across Bolivia, assisted by the recent drought.

It’s unclear whether the response to these fires will affect the October election outcome, but sentiments are running high in the country, where more than 70 percent of people prioritise environmental protection over economic growth.

Bolsonaro and Brazil might grab the headlines, but Bolivia too is now host to a desperately serious humanitarian and environmental situation.

Claire F.R. Wordley, Research Associate, Conservation Evidence, Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

#Environment

0 notes

Text

“The Cockchafer, Part 2”

*(Featured image by dbgg1979 [CC By 2.0], via Flickr)

By Birgit Müller and Susanne Schmitt

We met Ernst-Gerhard Burmeister at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology where he has dedicated most of his professional life to the amazing collection of over 25 million zoological specimens, one of the largest natural history collections in the world. The collection owns more than 100 000 of the approximately 500 000 species of beetles (Coleoptera) in the world. He has been an active defender of the zoological collection in political committees and has advised the region of Bavaria on issues of biodiversity. He has also traveled extensively, following mayfly swarms (Palingenia longicauda) in Hungary, and exploring the fauna of the Amazon at the border between Peru and Bolivia. When he spoke to us about his experience of insect loss, however, he returned to the calm of the sunny conference room…

The first time I experienced that sudden feeling of loss was about 20 years ago when I could not find any cockchafers in my garden in May. I used to collect them every year for my daughter’s birthday until she was 30 years old. She was born in May and it became a tradition between the two of us that she loved. When she was small, it had been absolutely no problem to find cockchafers in the garden; but then we began to see fewer and fewer of them until, finally, I had to collect them from somewhere else. Fifty years ago cockchafers belonged to spring. It was the creature that reminded us that nature was awakening. But people live so differently nowadays that they don’t even realize the loss. Who still goes for a walk on a calm May night and observes the cockchafers buzzing around the streetlights? Who realizes what the type of agriculture we are practicing does to insects?

A cockchafer in the grass. Photo: Max Pixel (Public domain)

Cockchafers mating. Photo courtesy of Ernst-Gerhard Burmeister.

The use of potent agro-chemical continues unabated. DDT, the chemical Rachel Carson campaigned against so vigorously in 1962, is still permitted in 21 countries in the world. In France, researchers studying the layers of sediment in Lake Saint André in Savoie found the greatest concentration of DDT in sediments dating from the 1990s—that’s 20 years after DDT was banned in France. Neonicotinoids, the world’s most used pesticides, are far more toxic than DDT and have a half-life of up to 20 years in the soil. This means half of all neonicotinoids in the soil are still there 20 years later—and since their use is not forbidden, they have only been accumulating. We see traces of them in wildflowers and future crops.

Neonicotinoids are particularly harmful to many insects and act as nerve agents. Eleven thousand bee swarms have already died from toxic exposure in the Rheinland. While toxicology studies last only two to three days, the consequences of pesticide use affect insects for years. They don’t just fall dead from a stem: they lose their orientation, don’t feed properly any more, lose their capacity to reproduce, and are less resistant to disease and parasites. But if you argue with the chemical industry or farmers, many just laugh their heads off when confronted with your observations of loss and the absence of insects. Only hard data counts. This is why it was so important that the entomologists in Krefeld documented the decrease in the biomass of insects over 25 years. In one site, the biomass of insects collected over one year in 1989 was 1,6 kilograms, compared to only 300 grams of insects left in 2013.

Our nature protection laws don’t do enough to shed light on the issue of insect loss. At most, they suggest that it is important not to disturb animals in their natural environment. While those who love and know nature—and in particular insects—try to interfere with nature as little as possible, other groups continue to do whatever they please: practicing chemical intensive agriculture, or paving over soil. In Bavaria, insect habitats continue to be destroyed. Bavaria is the only federal state in Germany where farmers are not expected to establish a protective agricultural border between farmland and bodies of water.

A strip of wild flowers along a farm track at Langley Park. Photo © Des Blenkinsopp, licensed for reuse (CC BY-SA 2.0), via Geograph.

Although farmers are encouraged to plant strips of meadow flowers between cornfields and the road—called “Akzeptanzstreifen” (acceptance strips) in German—their main purpose seems to be to make people more accepting of monocultures. These strips do not help insects much; most of them are mowed just when the insects have laid their eggs. It seems that the authorities are more interested in drawing attention to insects by growing and maintaining entomology collections in institutions, rather than by nurturing actual living insects. However, we can only speak with authority against the practices that kill insects if we are able to document what types of insects exist, and where and how they live. We need to learn to pay attention to insects again.

When I was a toddler I was fascinated by everything that crept and fluttered. My father was the son of a forest ranger and he understood my fascination with the natural world, that I needed to touch things in order to understand them. Contrary to other kids my age, and especially the kids today, I was allowed to keep bugs in boxes, dig up maggots, and play in forest swamps. I used all my senses, had to touch everything to examine it, test it and try it out. I liked bugs with stable chitinous armor that were not easily damaged by my handling them. When I became a biology student, I specialized in insects and became fascinated with their capacity to identify and follow smells. Did you know that ants can distinguish left-handed sugar molecules from right-handed ones? It took humans two hundred years to figure that out.

Goliath beetle. Photo by Skyscraper [CC BY 3.0], from Wikimedia Commons.

There is so much to discover. Parents and schoolteachers should let their kids get close to insects and share knowledge about them. If a child knows something, they lose their fear of it, their timidity. They constantly discover new things and learn from them: “Oh these butterfly wings have soft scales, I’d better not touch them.” It is our alienation from insects, being out of touch with them, that makes people in Germany not realize that insects are disappearing.

When I was in East Africa, in Irangi Kenya, the people had names for all kinds of insects and could distinguish them according to their use: as natural predators, as food. I would describe an insect to children there and they would fetch it for me. They knew what kinds of rotten fruit attracted them. Like me when I was small, they played with bugs. I remember they had a giant bug—we called it a Goliath beetle (Goliathus). They would tie it to a string and have it fly around them like a helicopter; and when it got tired, they would let it go.

Here in Germany people think they can lead a sterile life: everything has to be washable. Any apple with a worm in it gets rejected. Everything has to be flawless. They don’t want to share their habitat with small creatures, to feel revulsion because something else is living with them—especially if that something is a creature scuttling out of sight, like a silverfish (Lepisma saccharina) or cockroach (insect of the order Blattodea). If you switch on the light and see something disappear under the cupboard…Uhhh!

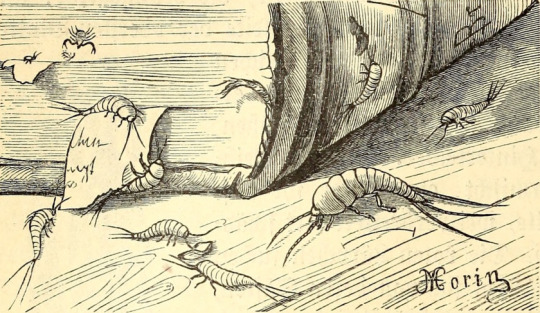

Silverfish belong in the bathroom. They are useful there. They eat the algae from the joints of bathroom tiles. Cockroaches rid the kitchen of discarded food where fungi and bacteria might otherwise settle. Kids are not by nature afraid of spiders. Although, even my grandchildren cry when they come to my house: “Uhhh there is a vibrating spider (Pholcida, or cellar spider) up there!” But at least they know it by name.

Illustration of silverfish (Lepisma saccharinae) taken from Brehm et al., Brehms Tierleben : allgemeine Kunde des Tierreichs (Wien: Bibliographisches Institut, 1890), 696. Image via Flickr (Public domain).

We have a lot of work ahead of us to counter this tendency. Most of the initiatives to help insects are still limited and voluntary. It is generally private nature protection associations (Naturschutzverbände) that offer courses and excursions for those interested in rediscovering and reconnecting with insects, when the state and the official school system should really be the ones driving these actions. Nevertheless, such initiatives have been quite successful in encouraging the public to engage with their environment: In big supermarkets that sell gardening supplies, glyphosate has been taken off the shelves because of pressure exerted by the customers (although farmers do of course still use large amounts of it on their fields). Hobby gardeners have turned away from fragrance-free flowers and are asking for aromatic plants that will attract insects. Nature protection associations have also encouraged their members to abandon uniform mowed lawns. As a result, we’re now seeing some of the 540 species of solitary bees and bee colonies returning to pollinate flowers and blossoms. These are small beams of hope indeed.

Reflections on Insect Loss “The Cockchafer, Part 2” *(Featured image by dbgg1979 , via Flickr) By Birgit Müller and Susanne Schmitt…

#biodiversity#cockchafer#conservation#DDT#education#entomology#environmental policy#insects#pesticides

0 notes

Text

Grain production depends on ending deforestation, studies show

In Brazil, researchers warn of “agro-suicide” and recommend new moratorium in response

[Image description: cornfield is inspected during Operation Shoyo Matopiba in April 2018, when Brazil’s Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) and Federal Public Ministry.]

Recent scientific studies confirm what Brazilian farmers already feel in practice: the uncontrolled production of agricultural commodities is destroying the productivity and profits of agribusiness itself, a cycle researchers are calling “agro-suicide.”

Regions such as the southern Amazon and Matopiba (the borderland between the Brazilian states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia) in the Cerrado savanna are the most affected by lack of rain, prolonged rains and waves of extreme heat.

Resulting financial losses are expected to reach at least $4.5 billion annually by 2050, according to a conservative estimate; if deforestation continues unchecked, damage could reach $9 billion per year.

Though grim, the scenario can still be reversed; one recommendation from the study is to adopt a moratorium on soy in the Cerrado, inspired by the Amazon Soy Moratorium.

Continue reading.

#brazil#brazilian politics#politics#environmentalism#environmental justice#farming#mod nise da silveira

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inside the indigenous fight to save the Amazon rainforest

Speaking to Rayanne Cristine Maximo Franca, the 25-year-old indigenous youth activist from the Amazon, about a historic march, resistance, and youth empowerment

On August 19 2019, thick black clouds covered the city of São Paulo in an apocalyptic darkness. São Paulo’s black sky was a result of the amazon rainforest ravaged by tens of thousands of fires. The number of forest fires in Brazil has grown 70% since this last January over the same period last year. The rainforest most hit, several Brazilian local governments also declared a State of emergency, in addition to all flights being diverted. The plume of smoke advanced into the South American continent, also fueled by forest fires in Bolivia and Paraguay, reaching parts of Southern Brazil, Northern Argentina and Uruguay. It’s been proven that all outbreaks of fire in the Amazon are caused by human activity, mainly due to deforestation for the sake of corporate agriculture.

Even though winter is the most favourable time of the year for the spread of fire in Brazil because of its drier weather, in the case of the Amazon there is no natural process that could cause wildfires. This means that all outbreaks of fire in the Amazon are caused by human activity, mainly due to deforestation for the sake of agriculture. In other words: the peak of deforestation is now being followed by a peak of wildfires. Thus, the explosion in forest fire occurrences in the Amazon is directly associated with the intensification of deforestation in the region.

In the Amazon rainforest, roughly the size of a football pitch is now being cleared every single minute, according to satellite data. So far, that leads to a total of 315,686 football fields. Despite recent rapid fire alert systems put into place, President Jair Bolsonaro not only blames environmental groups for setting fires whilst downplaying their risks, he persistently attempts the Ministry for Farming - which increases agro-industrial production, destructive mining and logging practices, and is under the firm grip of lobbyists – to take control of the Amazon.

As the world’s largest rainforest, the 6.7m square km Amazon region plays a crucial role in absorbing carbon dioxide emissions and stabilising temperatures. If destroyed, it would be incredibly difficult to limit global warming and save the planet. Much of the remaining forest is already owned, including by Brazil’s indigenous people. They hold 13 percent of Brazil’s land area. But as the appetite for destruction increases, the situation has sparked tensions, and in some cases violence, between Brazil’s indigenous populations and land-grabbers, who believe they have the unspoken support of Bolsonaro’s administration.

Indigenous women and girls – who increasingly play outsized roles as leaders, forest managers, and economic providers – are even less likely to have recognised rights. Which is why in August, for the first time ever, tens of thousands of them took to the streets of Brazil’s capital Brasília for days to denounce Bolsonaro’s “genocidal” policies. Themed “Territory: Our body, our Spirit,” they called for unity and visibility in their strength and critical roles as human rights defenders and safeguards of the world’s lands and forests. They’ve made it clear that women are the most impacted by agribusiness, climate change, sexism, and racism.

Among them was Rayanne Cristine Maximo Franca from the Amazon rainforest, whose family was receiving frequent death threats because her father had spoken out against corruption. When leaving her home at 17 to study in Brazil’s capital, she embarked on a relentless pursuit of rights and recognition for young indigenous women.

Read her interview.

#brazil#amazon rainforest#environmental justice#indigenous rights#feminism#brazilian politics#jair bolsonaro#rayanne cristine maximo franca#politics#amazon fires 2019#brazil forest fires 2019

97 notes

·

View notes