#that's how bad it was. it makes capitalist economics fuN

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

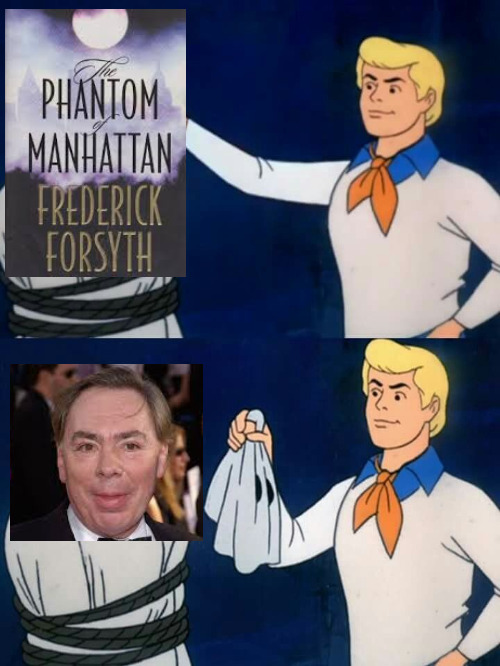

no context spoilers for the phantom of manhattan

this book is fucking TERRIBLE

#screaming into the void#my reviews#poto#no shame to anyone who actually likes it but this book was everything i hate about parallel novels and modern historical fiction#so congrats to frederick for making me forget my initial begrudging praise for the story's structure. i stand by it but eugh. bad book#the worst crime is that it's BORING. everything and nothing happens and it's fucking BORING#we get to meet all these quirky side character (who let's be honest are mostly just stock characters and stereotypes with nothing added)#and we get to know them for NOTHING and our leads are as interesting as wet cardboard#i hope whoever finds the book in the little library i immediately chucked it into appreciates it more than me because christ. CHRIST!#worst part is the book i ordered through the library isn't here yet so now i'm stuck chipping away at the equally boring pro-free market#economic history book on the great depression that i think i've been reading for years at this point#and i still would rather read THAT than another word of phantom of manhattan#that's how bad it was. it makes capitalist economics fuN

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I played some Victoria 2 today (a Japan campaign ofc, and admittedly with the Historical Flavor Mod), to sort of reflect on it in relation to Vicky 3. It is rough going back to the economy of Vicky 2 after playing 3, let me tell you - you knew intellectually it was "bad" system before, but you loved it anyway because of the full package. But now you can see the alternatives and remove the quotations, it is just bad! Building an ammunition factory that requires sulfur, having domestic RGO sources for sulfur but they are not producing enough to supply even one factory, and just not being able to do anything about it that isn't drastic or long-term because the world market is feeling fucky today is unacceptable once you have played a game where that isn't true. My industrialization strat should not waffle between "build a railroad for a 5% bump in output" and "invade Indonesia", give me a middle ground here guys! And it does not stop there - capitalists are useless, "build factory on RGO and expand forever" is optimal 99% of the time, key technologies will like double your output making them forced decisions, etc.

And, if you are can't build factories because you aren't civlizied yet...you have no econ game at all. You just do virtually nothing. Now that you see how that isn't required, the mechanics are ruthlessly bad in key ways.

But! But but but! I think Vicky 2 is a still a better game. The funny thing about that "I don't have enough sulfur" thing is that I didn't even care. I built the factory "for the future", subsidized it, it outputted zero bullets, and I barely notice because you make so much money anyway you can generally ignore it. I build the factories primarily so I can have clerks staffing them and generating research points! Is that insane game design? Yeah, it is! But it is insane game design that doesn't get in the way. Nothing stops me from building a factory, it just isn't very good. Wanna build a huge military? Encourage some soldiers with your national focuses and go to town. Want to declare war on someone? You can just do that! And then I take the army I built, click it on enemy, and it fights them - revolutionary new approaches to game design folks.

Even politics, where Vicky 2 definitely does get in the way a lot and is actively not-good, it is at least more permissive and more importantly simple. If you have elections you get events to shift voter ideology, and national focuses to boost party support that work exactly the way you would expect. If you are autocratic you can just swap who is in power! Liberals support political reforms, socialists support economic reforms, if you have a majority support for a law click a button and it passes. Done. Putting socialists in power in 1870 Japan might result in a revolution, sure, but it works, you can try it, and try to beat the militant tide.

Meanwhile in Vicky 3 if you are autocratic putting a "minority" faction in power literally breaks your government and prevents you from passing any laws. You can technically do it but you just die immediately. Wanna build a coalition then, where conservatives & agrarians ally together? You technically can again, but the penalty for "non-compatible" coalition partners is so high it 90% of the time crashes you into 0 anyway. So you have the "option" of switching parties, but...you can't. You just have to appoint the landowners every time or you die. So what is the point? Why have the option? Let me play the game!! Let me try reforming things and face a revolution I have 40% odds of losing to! That sounds fun, why are you rigging the game against that?

I tried an Iran run in Vicky 3 earlier, and I had a revolution against the landlords, who had ~50% of the "faction" points in government. I won, and so their points got knocked down to ~0%, how that works. So I made a new government, right? Well, no! Every faction left was "incompatible" with each other and none of them alone could even muster like 30%. I had literally no government capable of passing laws. So I fucking quit the game? Because this was the product of winning a revolution, why would I continue?

In Vicky 2 fascists win a revolution and they coup the government and it's fascist now. You get the fascist laws and can pass reforms they like. There ya go. Done. Is it interesting? No, not really. But it works! It doesn't literally stop you from playing the game.

My Japan game actually started as Satsuma, since in HPM Tokugawa Japan is split into substate Daimyo. I modernized via encouraging intellectuals, took military & railroad reforms, built a modern land army, and built up relations with the other domains. I launched the Meiji Restoration, got 60% of the Daimyo on my side, won the civil war. Began building factories everywhere, built up my industry, built up my research output. Used the new tech & money to build a larger army, fought the Qing in a tough war but got Korea & Taiwan, allied with the UK & built up a steamer industry to get a modern navy. Then Russia got into a crisis with Greece and so the UK and I backed Greece and broke Russia, with me claiming some territories around Manchuria in the process. Later I invaded China proper to annex Manchuria itself and get some treaty ports, easily now because my military was much more advanced. From all that my infamy was high so I coasted into the endgame and pivoted to culture techs to trigger "decisions" around modernizing Japan that gave me bonuses while having nice historical flavor to them.

And generally the game just didn't get in my way on doing all that. I could "tell the story", which for an easy game like Vicky is normally what you are here to do. Vicky 3 is a much better economy simulator, but telling the story beyond that is such a chore, and often impossible. On politics, diplomacy, and especially military, it is philosophically a step backwards such that its more "developed" mechanics cannot compensate for the mistake.

(I think it is funny how much better a gameplay experience the "narrative via decisions" of Vicky 2 w/ HPM is. They give flavor to the nations with a ton of bespoke, scripted events. Which...just works because they are straightforward. Vicky 3 wants to be "emergent" and so limited such events, but missed the forest for the trees there)

I find this sad because honestly there is a "blended" version of these two games that is amazing. Vicky 3's econ system (with tweaks ofc like making trade valuable) and philosophical commitment to minimal military micro (SO finicky in Vicky 2 to replenish armies where individual brigades die off, ugh), with a system that understood storytelling is first. Let players do things, and then give them consequences that are manageable in response. Get out of the way of the stories your sandbox game is built to tell.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

We finally finished the fifth elephant.

I wish I could say after my 2nd reading I enjoyed this book, but unfortunately it's marred by painful pacing and deeply frustrating overtures to any of the actually good scenes.

Read more for my full thoughts:

Fifth Elephant is a book that struggles with its identity in a way I haven't seen in previous watch books, and it's made all the more maddening by the fact that out of the twenty million things the book tries, there is some stuff of substance! But you can never quite get a handle on any of them because the book is so damn busy!

I struggle to pinpoint a main theme in this book. Is it about fascism, the consequences of long distance communication, or gender and race in conservative society? The book doesn't doesn't stay with any of these concepts for long enough, which results in a muddy plot.

Is it about the past, the future, history, belief, traditions, what it means for things to stay the same and yet change, and what that means for truth? But that feels like well traveled ground, especially with Men At Arms and Feet of Clay, and honestly, this book doesn't sell this well enough to me, because while it’s Telling me these things, it's not actually Saying anything with them.

While Pratchett makes a point to give Klatch space to breathe, and make it a country on its terms (though, admittedly, he falls into orientalist tropes), Uberwald is plagued by Western exceptionalist writing choices. Why does Pratchett connect ideas of the future to Ankh Morpork (a proto-capitalist state), and imply that Uberwald must be forcefully pulled along with it? Why are there multiple scenes about how much the people of Uberwald hate living there, that they want to go to ‘modern’ Ankh Morpork, without really scrutinizing Why that is? Why is the fact that Ankh Morpork has become Such a global economic power not explored in a critical way, at least not thoroughly? (Especially since I Know Pratchett is capable of it. He did it with Jingo.)

I think the biggest crime this book does, though, is with its characterization of Vimes. I can't fathom the ‘why’, but for some reason Pratchett leans into the hyper-masculine noir traits of Vimes' character. They’ve always been there, but while the other books took a satirical spin to it, there's a certain romanticizing of it in this book. Vimes’ violent, ‘beastly’ nature is bad and Scary, but oh, isn't it Cool and Dark and Edgy too? Look how this strong, bloody man frightens the townsfolk, smokes a cigar while he shoots a man to save his poor wife. This is tolerable in bite sized portions, but in Fifth Elephant it's like sickening sweet. Why does Vimes kill a man in the streets, on purpose, (the first time he does that in the climax of these books!) and it's hardly addressed! (Yes, Wolfgang deserved it. But when So Much of Vimes' character is delegated to Not giving in to the Easy Choice, why is this decision not given the space it needs? Especially RIGHT after Jingo!)

There's just this strange sense of a focus on masculinity in this book that wasn't in any of the others. Like, why is it that in the Uberwald book, we spend more time with Carrot chasing Angua then with Angua herself? Why the hell is this not an Angua book? Why, in every scene where she has to confront her problems, whether that be her family or otherwise, must she be saved by a man?

And all of this is a shame because there Are some scenes I really enjoy in this book! I love when we see Sybil and the wedding pictures, I love Vimes getting chased by werewolves. I find Inigo a really fun character, and I LOVE MARGOLOTTA. The parallels between the clacks towers and modern day communication, the little crumbs here and there of spy media tropes, the addiction metaphors, the werewolf family! But that's the kicker! We never spend enough time with Any idea! And none of it connects well enough together! Which is crazy, because Jingo and Feet of Clay were both such Cohesive stories.

Regardless. I’m looking forward to The Truth because I really missed Ankh Morpork in this book. And Also Vetinari. (who, funnily enough, is hardly in this book. I guess he took up too much space in Jingo).

My final thoughts: Vimes should have had a daughter instead.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

"AI won't compete with talented artists"

Is my least favorite argument around AI art/writing/etc.

Firstly it poses these big issues for me: you don't understand how making art works and that people develop as an artist, that there's an easy way to place the line of who are "good talentrd artists". But there's one I want to go into more than these two issues and thats the by saying this you assume capitalists and the system we have gives a shit about "real good artists".

Capitalism doesn't care if artists can be talented or good at what they do. They don't care if the artist had a large portfolio, has worked on big named projects, is highly revered or respected, or even that they're resume is longer than most. They don't. The goal of capitalism is profit which relies heavily on worker exploitation. And with the advent of the unionization Renaissance and the writer actors strike plus much more, you can kind of piece together why talent isn't going to matter with ai art. Unionization and worker solidarity is the anthesis to workers exploitation. Solidarity is an attempt to remove power of capitalists to exploit. So, why did the execs during the writers strike/actors strike want ai so bad and kept putting their feet down? Why is ai art so promising to capitalists?

Well here's an article describing the excuse of why they want ai art

But in reality this really translates to "instead of exploiting workers (ones that will unionize/go on strike) we can replace and steal their work and avoid issues with a human worker". The propaganda is always "it will help innovation and creativity" the company line of all capitalism. But capitalism doesn't actually want to advance or be transformative or even innovate (source is general topic not just ai art). They want to maintain power and profit.

Talented artists (if you can even pick a definable line for that) will not survive in a world that does not carefully regulate AI and protect their creative property. They just won't. Automation of work can never work under a framework of capitalism where peoples jobs are tied to their Healthcare and livability.

People assume that business has their best interests at heart and many assume "well it doesn't affect me ofc bc I enjoy making ai art,". And it's a fools errand. The foot in the door to art, to automating and ridding human artists in the pursuance of profit and cheap efficiency is bad and it will get worse. The foot in the door with no regulations will affect other jobs, other humans, other fields. (Take ridding cashiers at grocery stores as a recent example. The source is a bit pro in its tone sadly, but I thought it a good article to read about the concept. And how ai forces customers to be free training for the ai so they can sell u more shit lmfao). And as more and more jobs are replaced with no regulation or power given to workers, economic disparity will get worse. And you having fun with ai art don't see that the foot in thendoor is dangerous and you don't care bc it currently doesn't affect you.

And this isn't to fear monger. Or to say technology is bad. What it is to say is stop placing your trust into businesses whose goal is efficiency and profit and exploitation above all else and stand in solidarity with your fellow human. Beg for regulations and control and protections for their sake and yours.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

No game has ever made me sit down and start writing academic-level essays like Scarlet Hollow does. There are just... so many angles it could be analyzed from, and so many fascinating themes running through it. The personhood of children, the personhood of animals, things that are passed down through the generations, from the negative (generational trauma) to the positive (local traditions and folklore).

I'm not that knowledgeable on horror as a whole, but I know there's a notion that supernatural horror is often representative of more realistic fears, and from what I've noticed, the theme running through all the horror concepts in this game is a lack of autonomy, be it economic autonomy from living under capitalistic oppression, social autonomy from an overbearing parent, or bodily autonomy, with everything from the Ditchlings taking over animals' bodies to be hosts for their young to Charles Shaw Jr. hijacking the characters' bodies and using them as puppets.

As the most alive and reactive choice-based game I've ever encountered, I obviously see a lot of space to talk about choice and free will and morality (does it blow anyone else’s mind that so much of what happens in this town, right down to who lives or dies, is entirely dependent on the decisions of this one single person? How much power the player and by extension the cousin really has? It’s what makes it fun to play but it must also be so terrifying from the cousin’s perspective). And the comparative analyses that could be made with other games based on this too… My dream comparative analysis would be between Scarlet Hollow and, um, the Quantic Dream library? I’m sorry devs, I promise I don’t mean that as an insult - David Cage is a bad person who makes bad games but there’s also always been this boldness to the choices those games allow you to make and the ways they can branch that I kind of respect? I’m very glad I now have Black Tabby to look up to in that regard instead.

All of that, plus the game is a real masterclass in worldbuilding and characterization and pacing and humor… I would use it as a teaching aid in a creative writing class, for sure.

I’m sorry for the long post, it’s just that this game makes every neuron in my brain fire rapidly. I’m the kind of person who always tries to elevate my hyperfixations to the level of high art, because I like having this kind of stuff to analyze. Scarlet Hollow is the first fixation in a while that’s made it so easy. It really deserves to be elevated in such a way. Video game good. Make me think. The end.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fun story.

Australia is famously pretty bad at regional rail transport, and my state, New South Wales (NSW), is probably the worst at it out of the whole country. NSW's primary rail transport network consists of 19 of these things — XPTs (eXpress Passenger Transport) — which, while state-of-the-art in the 1980s when they were being built, are over 40 years old at this point and have been largely unrefurbished since the 1990s. XPTs in the modern era are famous for being slow, faulty, arthritic and uncomfortable.

However, in 1988, when the XPTs were still brand-new, the conservative NSW state government of the time commissioned a report from American consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton, a firm otherwise largely known for advising the UAE on how to set up their digital surveillance state, regarding the future of rail transport in NSW. The issue that the government had was that the XPT just wasn't profitable enough. Booz Allen Hamilton's solution was not to increase advertising for rail transport, lower the cost of tickets, run more frequent services or anything else. Their solution, on purely economic grounds, was to scrap long-distance rail transit in NSW entirely.

If you're a capitalist, this makes sense. The population of NSW is too small and too sparsely populated for any regional rail network to be profitable. However. Many small towns in regional NSW are reliant on regional rail, the XPT in particular, for connection to each other and to the state's major cities, and without it, they would be pretty much entirely isolated from the wider world. Regional towns in NSW have had next to no economic support from the state government for decades now and are almost unilaterally deeply poverty-stricken; if you live in one of these towns, access to a car is going to be unlikely at best, and access to a car that is capable of driving the ~150km to the next town over, let alone up to 500km to a major city, might be nigh impossible. If the state government had accepted the outcome of Booz Allen Hamilton's report, regional NSW would be dead.

Thankfully, they didn't, and we still have trains. In fact, within the next few years, the XPTs are getting replaced with a larger fleet of new diesel/electric trains, hopefully bringing NSW up to par with the rest of the country. But ultimately, had NSW's government followed the money, they would have found themselves with an absolute disaster on their hands.

Trains are good, people.

People who talk about what population density is necessary to "justify" a rail system are wrong but they're wrong in the opposite way from how they think. Even in Japan which has more than twice the population density of China the rail system is not profitable. JR makes most of its profit by operating malls and collecting rent from vendors. If you blindly follow profit instead of considering the broader social benefits the result will always be putting your rail system into a death spiral of rationalization. Stop expecting public transport to turn a profit that's not what it exists for.

32K notes

·

View notes

Text

Saw Transformers One tonight. As far as animated movies go, it was okay. I think I was just expecting way more out of it than I was going to get, for a movie that was aimed at kids.

More under the cut

Cons:

I feel like Megatron’s arc happened really fast. I understand that once he accepted the truth of the situation he got very angry very quickly, but it still felt like it was a bit too quick.

Mixed feelings about Elita. Her writing was good in some places and really clunky in others. Fell victim to the classic “only girl in the group” writing problems

I don’t know how I feel about Orion and D-16 both being mining bots? Orion as an orator and Megatronus as a gladiator offered a very Professor X vs Magneto dichotomy that I liked, and offered some very interesting ideas about the political and economic climate of Cybertron. Them both being mining bots doesn’t work quite as well

I think Brian Tyree Henry did a very good job as Megatron, but casting a black character as a villain with such a loaded past is…a dubious choice. Especially alongside a lot of white actors who are mainly known for their work in Marvel and have very little voice acting work under their belts.

Bumblebee. Dear god what did they do to my boy. It would have been so easy to have him chatty and awkward and unsocialized without making him such a bumbling mess. He’s still Bee so I can’t hate him but good grief did I want someone to throat-punch him occasionally.

I don’t know how I feel about goofy Optimus? It felt like spotting him into that role only worsened both his characterization and Bumblebee’s.

The fights were so fast I struggled to follow. Slow them down maybe 10-25%, and I’d be able to keep up.

Pros:

I really liked the elements of the Professor X vs Magneto dichotomy we did get between Orion and D-16. I like that dichotomy, and it can be very compelling if done well. And their friendship was fun to watch

Sentinel was immediately hateable. Look at him with that shiny blue and all that gold, so tacky. He just gets more punches le because he’s so casual about all the terrible things he’s done.

Starscream. Just everything about him. As chaotic as ever, and the homoerotic relationship persists. This man was quite literally asking Megatron to choke him out in front of Primus and everyone.

There is something deeply wrong with Airachnid, she’s absolutely terrifying in the best way for a female villain

A lot of interesting visual elements for the flashbacks

The quintessons were absolutely horrible to look at, excellent villain design. Go for the insect design, then the main villain with the Cthulhu tentacles. They were a mix of metal and flesh that was deeply uncomfortable so kudos for that

Sentinel welding the symbol of Megatronus into D-16’s chest? Dear lord? That was awful to watch but excellent for villainy

Megatron’s eyes doing the light trail like you get with a Gundam sometimes!!

The whole sequence where Orion is given the matrix and becomes Optimus was visually stunning and the music was phenomenal

The silhouette of Optimus with his face in shadow and his eyes glowing. Again, visually stunning.

All in all, it wasn’t a bad movie. I do have some things I think would have made it much better, but it was fun. I also couldn’t help but think every time how the options it presented might have been expanded on for more meaningful commentary. You have the Matrix retreating because people wanted its power, a villain systematically and intentionally disabling his citizens to keep them in line, that same villain selling mass quantities of their most precious commodity to their enemies while his people starve, and a friend-turned-antagonist who is radicalized by the extreme suffering of those around him while the rich live like kings who profit off that same suffering. There was potential for interesting commentary about capitalist greed, the effects of war on the economy, class divisions, and just generally Megatron’s shift from revolutionary to tyrant. But I went into a kids’ movie expecting Gundam IBO storytelling, so that’s partially on me.

0 notes

Text

Phantom Liberty

I have been playing Cyberpunk since launch and have been a staunch defender of it. The glitches were all on the consoles or PC's that shouldn't be playing it. There was a ton of effort and care put into this game. I have done 10 playthroughs and have amassed 355 hours in the game. The themes of this game cover many political and social issues related to hyper capitalism. There is also amazing cultural representation! There is even a trans woman who has a great quest.

I was so excited about Phantom Liberty because the story addressed topics I have personally struggled with. I have a business degree and originally was excited to do a career in economic politics or owning a business. I even at one point wanted to be President of the USA. Now however I am a staunch anti capitalist and vehemently dislike the political structures in the US and how they cause harm to the most marginalized of people. I also had enlisted in the US air force during high school. I was never given the opportunity to serve because Donald Trump had banned the enlistment of trans people in the military. I feel this is for the better however because I was able to access a career field I truly care about. The cherry on top of the DLC is that its a super spy thriller. I love this genera and have watched and read many of Ian Flemings' James Bond Novel based media. I wrote my own super spy setting for D&D and am working on its 2nd expansion right now.

These are some photos I took during my playthrough (admittedly pretty late into it). I really think CD Projekt Red really improved their lighting aesthetics. I also had a lot of fun making outfits.

In my first ever playthrough of the game I got the "Where Is My Mind" ending. Which sees you being fucked over by corporations. I played a corpo and instead of rejecting cooperate control I embraced it. This made Johnny kick and scream the whole way. I figured out that characters like Misti and Johnny are the story tellers way of speaking to us. They however only talk to you after you have made the decisions. I decided to do another capitalism lover in my Phantom Liberty playthrough. I don't fully understand why I prefer playing these characters. I think it feels like a safe space for me to grapple with these topics and experiment with what I would do in these situations. I LOVED the "bad" ending for the DLC. With all of the other endings in the base game V is unable to find a cure. In this one you ARE able to find a cure! Which is so freaking refreshing.

After the credits there was like an extra 1.5 hours of gameplay. Instead of just saying "you fucked up" it was like yeah you did fuck up and hurt a lot of people but heres how you move forward with that. My favorite moment in the whole game was seeing Misti 2 years after. It felt like I was a character in her story rather than being a main character. This ending is called "Things Done Changed". The themes explored in this portion felt extremely relevant for me. I had a major mental health crisis earlier in the year and I have been spending the rest of year trying to piece together what exactly happened to me and how it has changed me. This story ultimately had an extremely uplifting message. I even tried the other ending-"Who Wants to Live Forever"- which was emotionally a lot less challenging and is one of the rare endings which doesn't end your actual playthrough (which I have always kind of been annoyed by). And its not even like the ending didnt happen either I have multiple quests that happen afterwards because of the events of the story.

All this to say I had a ton of fun. Please enjoy the photos

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

He estado jugando Cyberpunk desde la lanzamiento y he estado un defensor acérrimo a la. Todos los fallos estaben todos en el consolas o en los computadoras que no debería ser jugando lo. Habia un tonelada de esfuerzo y cuidado pone en ese video juego. Yo he hecho diez juego completos y he acumulado trescientos cincuenta y cinco horas en la video juego. Los temas de esa video juego cubren muchos temas poltico y sociales relacionada a hipercapatalismo. Tambien hay representation culturalista asombrosa! Hay incluso una mujer de trans que tengas una busqueda.

Era emocionada para Libertad Fantasma porque la estoria se hablo a temas yo he lucho con. Yo tengo un licenciatura de negocio y originalmente era emocionada a aser un carrera economica politica o ser dueno de un negotio. Yo incluso en un momento quiero a ser la presidente de los estado unidos. Pero ahora soy un acerrimo anticapitalista y con vehemencia disgusto los structitur politicos en la estados unidos y como ellos causar dano los personas mas marganalizas. Yo tambien he enlisto en la estados unidos fuerza aarea durante escuela secundaria. Nunca me dieron la oportunidad a atender porque Donald Trump habia prohibido la enlisto de personas trans en la militaria. Siento que esto es para la mejor sin embargo porque pude acceder un campo ocupacional que realmente me importa. La cereza encima de la contenido descargable es un suspenso espiar supur. Me encanta la genero y he ver y lear machas de las libros de Ian Flemings James Bond. Escribe mi propia estoria de super para D&D y estoy trabajando en mi secunda ahora.

Eso son photographias que yo tome duranta mi juegos completos (es cierto que bastante tarde). Yo realmente pienso CD Projekt Red mejorada la aestheticas de luzes. Tambien me diverti mucho haciendo trajes.

En mi primera juego completas yo obtener la “Donde esta mi mente” finale. Que te ve siendo jodido por los corperations. Jugo de un corpo y en cambio de rechazando control corporativo, yo abrace lo. Eso hecho johnny patear y gritar todo el camino. Yo descubierto esa caracteres como Misti y Johnny son los contadora de historias hablante con nosotras. Ellos sin embargo solamente habla con tu despues de haber tomado las decisiones. Yo decidió a hacer un otro amante de capitalista en mi Libertad Fantasma juego completas. No entiendo completamente porque yo preferir este caracteres. Creo que para mi es un espacio seguro para abordar estos temas y experimentar lo que haria en estas situaciones. AMO la “mal” finale para la contenido descargable. Todo los otra finales en la video juego base, V no puede encontrar una curar. En este tu PUEDES encontrar una curar! Lo cual es tremendamente refrescante.

Despues los creditos habia uno y trenta horas extras como se juega. En lugar de simplemente decir "la cagaste", fue como "sí, la cagaste y lastimaste a mucha gente, pero así es como sigues adelante con eso". Mi momente favorita de toda el juego fue ver a misti dos anos despues. Se sentia como si fuera una caricatura en ellas estoria en vez de siendo un personaje principal. Este final es llamada “Cosas Hecho Cambiado” (potencialmente suena mejor en inglés). Los temas exploradas en esta parte me parecieron extremadamente relevantes. Tuve una importante crisis de salud mental a principios de año y pasé el resto del año tratando de reconstruir qué me pasó exactamente y cómo me ha cambiado. En última instancia, esta historia tenía un mensaje extremadamente alentador. Incluso probé el otro final, "Quién quiere vivir para siempre", que fue mucho menos desafiante emocionalmente y es uno de los raros finales que no termina tu partida real (lo cual siempre me ha molestado). Y ni siquiera es como si el final no hubiera sucedido. Tengo múltiples misiones que suceden después debido a los eventos de la historia.

Todo esto para decir que me divertí muchísimo. Por favor disfruta las fotos

Después de los créditos hubo como 1,5 horas extra de juego. En lugar de simplemente decir "la cagaste", fue como "sí, la cagaste y lastimaste a mucha gente, pero así es como sigues adelante con eso". Mi momento favorito de todo el juego fue ver a Misti 2 años después. Me sentí como si fuera un personaje de su historia en lugar de un personaje principal. Este final se llama "Cosas hechas cambiadas". Los temas explorados en esta parte me parecieron extremadamente relevantes. Tuve una importante crisis de salud mental a principios de año y pasé el resto del año tratando de reconstruir qué me pasó exactamente y cómo me ha cambiado. En última instancia, esta historia tenía un mensaje extremadamente alentador. Incluso probé el otro final, "Quién quiere vivir para siempre", que fue mucho menos desafiante emocionalmente y es uno de los raros finales que no termina tu partida real (lo cual siempre me ha molestado). Y ni siquiera es como si el final no hubiera sucedido. Tengo múltiples misiones que suceden después debido a los eventos de la historia.

Todo esto para decir que me divertí muchísimo. Por favor disfruta las fotos

so sorry for the quality of the translation. Losiento para la calidad de la translacion

#cyberpunk spoilers#mental health#phantom liberty#cd projekt red#in game photography#spanish#espanol

0 notes

Text

In the areas of the US South where Kudzu was introduced, it is a grazing crop, but it is also a noxious weed, requiring significant efforts to control. Every year, it spreads farther north and west. It has crossed the Mississippi, and is making inroads on the Mason-Dixon Line.

Kudzu has not yet encountered the second part of my sentence: "an insurmountable terrain obstacle." Thus, I think the use of kudzu is an appropriate example for the metaphor of growth until a resource is maxed out.

Clearly the drive to expand and "grow" is an inherent property of things that exist

No, growth is not an inherent property of things that merely exist.

Growth is an inherent property of processes which exploit a metastable equilibrium to reach a new equilibrium. I'm sure someone has given this a fancy name like "metastability collapse," but I hadn't encountered a name for it and didn't feel like coining one for the original post.

Put abstractly, the idea is approximately this: In some systems, there is a stable condition. An outside process may be introduced to that system which upsets the stability, extracting something from that system which allows the process to continue, until the extracted something has been consumed.

Here's how that applies to each of the examples I gave:

Chemical reactions extract stored chemical potential energy, going from a high-energy state to a low-energy state and producing energy, until there is no more stored chemical energy to extract.

Fire is an example of such a reaction: the chemical potential energy is stored in the fuel, and unlocked with the combination of heat and oxygen.

Kudzu extracts stored chemical potential energy from the ground and from CO2, using water and sunlight and nitrogen fixation. The kudzu crop continues to grow until one of those inputs is limited.

Deer extract stored chemical potential energy from plant matter, using really fun chemistry that still depends on atmospheric oxygen. The deer population continues to grow until the plant-matter input is limited.

Stalin's USSR grew by extracting resources from the ground via the processes described by the Five-Year Plans. The USSR's economy grew until it hit limits on how much the Five-Year Plans could produce under the conditions in which they operated. This is a wonky example, but I included it because the first few Five-Year Plans show that "growth" is not exclusive to capitalist economics.

But anyways.

It's actually pretty difficult to argue with something like this in a way other than mocking

Nah, it's not that difficult at all. Here's a few pointers:

You figure out what the argument is about.

You separate the argument from the examples and proofs. Does the argument rely on all of them being true, or can it subsist on just one?

You figure out what premises are assumed to be true within the scope of the argument. Then you assume those premises are true for the sake of argument.

You figure out what base knowledge is assumed within the conversation within which the argument occurs. If none is familiar, or if the use seems wrong, you check it.

And then you engage with the argument.

No mockery necessary!

It's actually pretty difficult to argue with something like this, [...] because no real argument has been put forth,

This post appears to have gone over your head. But that's okay; let's teach you how to play catch.

Here's my original post broken down, using those pointers I just gave you:

Argument: My original post was an objection to the idea that the feared GAI growth was because of capitalism. My argument is that GAI growth is better understood as the metaphorically-described phenomenon, instead of being understood as a capitalist urge.

Examples given: chemistry, fire, kudzu, deer, Stalin's Five-Year Plans.

Assumed premises: a GAI will grow unchecked (will foom).

Base knowledge: GAI, GAI growth concerns, capitalism, "a bar conversation", basic chemistry, fire, kudzu, deer, Stalin's Five-Year Plans, this mode of discourse

Suggested ways to engage:

Back the original argument: Point to where capitalism would be encoded in the utility function of a General Artificial Intelligence that fooms.

Back the original argument: Explain how GAI fooming for capitalist reasons would be meaningfully different from GAI that fooms for other reasons.

Make your own argument: Provide a different explanation for why GAI would foom.

Back OP's argument: Enlarge upon my argument.

Rabbithole: go off on a tangent

Additional detail: Examine the two arguments in the original post by providing information not represented in the post, such as by discussing how actual AI-safety theoreticians discuss this, or by providing examples from science fiction, or by injecting real-world information in analogous fields such as computer viruses and worms.

Answer the question: "Why should a General Artificial Intelligence be any different?"

But those suggestions are only if you feel like engaging with the post, of course.

I think this post is a pretty good example of what people talk about when they say that the rationalists aren't very good at logical reasoning. it's just various paranoid gesticulations and pathological neuroses piled on top of each other haphazardly. #like i honestly cant tell if this is trolling it's one of the stupidest posts ive ever read

OP was inviting you to play with a toy, but instead you have demonstrated that you didn't understand the invitation.

Better luck next time, eh?

The drive for a GAI to grow infinitely comes from capitalism, or so my interlocutor believed during a bar conversation the other night. This was after we had set aside mundane issues like bad orders resulting in paperclipping behavior.

I disagreed. Unbounded growth behavior, or growth to carrying capacity, is behavior that we see in situations without capitalism, without sapience, without sentience, indeed without life. A chemical reaction will continue until it reaches equilibrium. A fire will burn until one leg of the fire triangle collapses. Kudzu vines will grow until they reach an insurmountable terrain obstacle. Deer will reproduce until predation or starvation cap their numbers. Stalin's state-socialist Five-Year Plans aimed not for maintenance of the status quo but for growth.

So on every scale, from the entropic to the environmental to the economic, we see that a process will continue until it reaches a stopping point governed by the rules of that process' completion. Why should a General Artificial Intelligence be any different?

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

I find it interesting how Wilbur always seems to gravitate towards authoritarian characters when he's roleplaying, even when it's the more casual semi-roleplay of the 100 players challenges. It just seems to be the kind of character he likes playing the way Techno pretty much always makes his characters violent and Tommy usually makes his intentionally obnoxious and hot-headed.

I think it's Wilbur's charisma, it just makes him suited for that kind of role. And his interest in stories about power and politics. The easiest way to get those going is to establish an authority.

I was just watching his capitalist and communist challenge videos and what stuck with me was that the defining attribute in both of those was the authoritarianism, not the economic system. Both times Wilbur was the highest authority and punished everyone harshly if they disobeyed.

Yes, I know it's just funny minecraft videos but come on, how am I NOT supposed to analyse explicitly politically themed content? And I'm just saying it's interesting, I'm not like accusing him of making the videos wrong bc I know it's just entertainment. (I actually REALLY wanna go on a tangent about this but I’ll hold it in for now lol.)

But yeah it's just funny how even Ghostbur still has that authoritarian side. Ghostbur doesn't want to be a leader himself but he still thinks the server needs one. And even c!Wilbur's "anarchist" phase was more about destroying L'Manberg, not because of any anarchist ideals but because it wasn't what he wanted it to be, and it wasn't his anymore.

It's an interesting contradiction in a way because of all his anti-authoritarian rhetoric and being so involved in two revolutions, but it's not incongruous because the point is: ultimately he wants to be in control. He isn't happy with just anyone in power, it has to be him. Not that he necessarily needed ALL of the power: At first he would have been happy with just having the monopoly on drugs, just having his own small business "empire", but when he got denied that, he got more ambitious... and I get the sense that with every obstacle he faces he grows increasingly ambitious.

In a lot if ways Dream is the same, by the way. That's the sense I get from his character. The less in control he feels the more ambitious and authoritarian he gets. That's my read on him.

..... Okay tangent under the cut because I can’t help myself:

I gotta say I do think Wilbur should maybe do a bit more reading on political theory and political history. He's obviously interested in it but his actual knowledge seems pretty limited and superficial, and his political analysis is sometimes just kind of bizarre honestly. Since he likes writing geopolitical stories and political intrigue, it would really benefit his writing too.

I think he should definitely check out some leftist theory, and obviously I'd recommend anarchist theory too lol. Something contemporary, the classics are good and all but they're a bit outdated. And learn some economics too, just making sure to check out various different economical theories because the currently predominant economic theory is just... extremely flawed, frankly. I know I'm showing my bias but hooo boy. You really can't separate it from neoliberal politics, at all, the fact that it's being so heavily promoted has everything to do with politics.

I would recommend Ha-Joon Chang for a capitalist critique of capitalism. I would definitely consider Chang a capitalist but he's basically the least bad kind and has some really good analysis of neocolonialism. From a leftist perspective... idk, I actually struggle more with leftist recs because I'm more critical of my own side lmao. Also a lot of my own introductory reading wasn't in English. But idk, Richard D. Wolff maybe? I kinda have a soft spot for him even if I don't always agree. And like Chang he's good at talking about economics in an understandable way. That's kinda why I often rec these two, because they don't require prior economic education.

Also both of them are actually pretty entertaining. Wolff does these "Global Capitalism" talks which are recorded and posted on YouTube and which are like genuinely fun to watch a lot of the time (or they were back when he was able to have a live audience at least) and Chang has a wry sense of humour. Idk if Wolff would appeal to Wilbur specifically, but I think Chang would.

Btw if you guys can think of other good recs, go ahead and put some in the notes or reblogs. If you put in links I can reblog those additions so they show up.

#dream smp#wilbur soot#wilbur soot critical#i guess#idk#i don't mean this to be negative#scheduled post

241 notes

·

View notes

Text

I would like to suggest that corporate pride is not actually always the cynical and manipulative capitalist scheme that people portray it as on the internet. Corporations are bad and American capitalism is bad and it's funny to make fun of the silly candles at target but I actually think that a) it's a very complicated project to try to actually judge the level of dissonance involved in the actions of a corporation and a large corporation can simultaneously make a choice to invest money and lobbying efforts in support of an anti-queer politician or political party that actively denies the humanity of queer people as a fundamental part of their political ideology AND make a relatively socially benevolent choice to release some kind of pride statement those things can exist at the same time within an organization of that scale without a top level executive convening some sort of meeting where everyone sits around and talks about their cynical plot as a company to manipulate the queer and clueless ally marketplace. I actually think that one of the big problems with corporations is that as primarily profit-motivated entities, even if people in the company have good social intentions, it may be economically unfeasible for the corporation to structurally carry out those intentions. In my view the actual problem with corporate pride is structured not as "cynical and manipulative corporate evil," which is how people talk about it on the internet but as a fundamental problem with trying to view corporations as coherent moral entities. It's overly reductive to say that corporate pride is good or evil because, like many other things in the world of socioeconomic phenomena, it simultaneously produces harm and good. b) I think that corporate pride is a spectrum. It's very silly and ultimately not very bold or productive for Home Depot or whatever to make their logo rainbow for a month however if a company has made an active investment in donating to advocacy organizations or hiring queer designers or even making a highly public statement in support of queer people that is probably producing an undeniable social good, even if the company is doing harm in other ways. c) The level of public exposure of queer people and queer rights issues today is a vast improvement over where we were at even five years ago and I think that corporate pride is to some extent a symptom of that. It would be much harder for a kid to grow up with a complete lack of awareness of queer issues now than it was when I was growing up and that's a really good thing in some ways, even if it means that corporations try to sell us silly rainbow products one month a year. d) as a caveat to all this I will note that I think that corporations have for the most part chosen to collect the most marketable and palatable version of queer culture under their various pride practices. One of the reasons I am personally frustrated by corporate pride is that I think it tends to promote an extremely white, monosexual, male, allosexual version of queer culture which is yet another example of corporate moral incoherence.

Basically, corporate pride is quite frustrating and silly but also a spectrum and complicated and that's a very hard reality to negotiate with any kind of nuance. Ultimately like I think that we should all keep making fun of foolish products that target sells and giggle about the home Depot logo being rainbowified and be enraged by the fact that so many companies donate so many millions of dollars to reactionary political organizations that deny that we should have basic human rights but I also think that if we can't approach this whole issue with any kind of nuance nothing will ever change.

Anyway...

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me and some others joke about hating Byakuya (because it’s just plain funny to do so), but the actual serious criticism of him is deeper. It basically boils down to the fact that he just isn’t very well-written and it ends up harming his likability a lot. Well, at least for some of us fans who can’t bring ourselves to like Byakuya or the way he was written in canon.

I mean, all of us know what Kubo was going for, turning Byakuya from one of the main antagonists of the Soul Society arc into an ally of the main characters using a sympathetic angle. However, Kubo’s attempt at giving Byakuya a redemption arc wasn’t very successful and was clearly very rushed—Byakuya basically went from “I will not look at my sister for 40 years straight and now I will let my sister die” to “I will do anything for my sister” in a heartbeat. And it honestly just isn’t a very believable character change at all. If we had been allowed to see some more interaction between Byakuya and Rukia—perhaps Rukia not immediately forgiving him and seeing more of Rukia and Byakuya working through their feelings towards each other, slowly rebuilding their brother and sister relationship—Byakuya would be a better-written character.

Another criticism is that Byakuya ends up stealing a lot of the spotlight when it comes to Rukia’s achievements, and that this is in fact one of his main roles as a character post-SS arc so it’s a bad look. Post SS-arc, we see Rukia constantly seeking the approval of her brother, and so it’s almost like the narrative is saying that in order for Rukia to be worthy and her accomplishments to be valued it must have the stamp of approval by a man, and moreover that Rukia as a character believes this. Which is just a really fucking weird thing considering he hurt her so badly? A lot of the emotional power of her fights and accomplishments, like her fight with Aaroniero or As Nodt or her captaincy or her marriage, gets a bit marred because of Byakuya’s constant “I will be here for the nod of approval” presence. Even with such a great female character and awesome character moments, Kubo’s misogynistic writing still shows through by making what Rukia has done all about a man and that man’s approval.

Beyond Byakuya’s personal interactions there’s the criticism of him being obscenely rich and not doing anything of value with his vast wealth, which is not a quality that is admired by many fans these days considering the opinions many of us have about capitalism and those who hoard wealth. However, this criticism isn’t specific to Byakuya, as there are lots of other obscenely rich characters or ones who come from nobility. So it’s really more of a huge narrative problem that causes characters like Byakuya to look irredeemable in the eyes of some fans. There are systemic economic and political issues within the Bleach universe that are naturally brought up because of the way Kubo created those worlds, i.e. having poverty-stricken areas alongside a few small groups who hold all power and wealth in the afterlife. But these important systemic economic and political issues that would help shape how characters would interact with each other are swept under the rug, and it becomes a problem when talking about wealthy characters like Byakuya who we don’t see put their wealth towards good things.

In the Bleach universe, Byakuya is a rich man that tends to be admired or respected by almost everyone rather than reviled by average/poor folk for his obscene wealth. We don’t see any of the characters who have a background of poverty hate his guts for his wealth he does nothing good with, not even those like Renji who interact with Byakuya all the time and would clearly be traumatized and radicalized by the insane gap of wealth. So while this Rich Boy Trait does not affect the way other characters think of Byakuya in canon, it’s something that rubs some fans (especially those who are staunchly anti-capitalist) the wrong way.

After all, it’s kinda hard to enjoy a character that is representative of everything you stand against as a real person. And this is especially true when it’s not acknowledged in the narrative that he sucks hard since he’s framed as cool and heroic the majority of the story, even to the point that the narrative bends backwards to ensure that he is a liked and respected character in his universe even when he does not deserve it. And it makes fans like me not want to like him, but to instead make fun of him. Because yeah, he is a rich boy asshole, and sometimes those types of characters can indeed be fun! But Byakuya is not particularly endearing or well-written.

#bleach#byakuya kuchiki#does this count as analysis? idk anymore i blur the line between formal analysis and casual opinions

30 notes

·

View notes

Link

A pretty decent entry in the genre of “arguing over meritocracy by left wing and contrarian pundits.” You should read it. @slatestarscratchpad couple weeks ago had his own entry in the genre when reviewing Freddie deBoer’s book.

But I’m going to point to and expand upon a minor point Yglesias makes.

***

The fun thing is to argue over meritocracy at the level of principles. Is it ethically sound to reward some people more than others for things somewhat outside their control? Everyone has a take!

But look, there is a difference between:

The most productive quartile of people in a field earn 25% more than the least productive quartile.

and

The top five people in a field earn ten thousand times more money than everyone else.

And both of these are meritocracy! They are rewarding people who are better at things. They both might even be unfair in certain ways, depending on what your definition of “is better at your job” is.

But you can see why the first scenario is “a fairly boring reward structure that incentivizes some people but does not create large scale injustice” and the second scenario is possibly society destroying inequality. If parts of your meritocratic judgment are unfair (like being influenced by social connections or inherited benefits from your family or just cultural affinity rather than “pure smarts and effort”) then it will be even more disgusting in the world where that leads the winner to earn 10,000 times as much. Especially if the non-winners aren’t even earning living wages. You’re going to see new workers, and even their parents, stress themselves out to an extreme degree to try to be one of the “winners” in that scenario. It introduces more *distortion* to the system.

People argue a lot about the principles of meritocracy a lot, but really what’s *causing* all this obsession with our economic system of rewards is the vast gulf between winners and losers in our current system.

Part of this is just laziness. Not on the part of thinkers but the broader society. For various reasons - good and bad - we let capitalist competition determine how large the reward for the “winners” of the system will be, and we just kind of accept that coefficient, and then argue endlessly about whether there should be a reward gap at all. MAYBE THE GAP BETWEEN WINNERS AND LOSERS SHOULD JUST BE SMALLER. Maybe we can be meritocratic without “one SAT score means you have two houses and a yacht, and a slightly smaller score means you live off food stamps in an apartment you share with three roommates.”

And maybe you don’t want to mess with the capitalist system that led to this since you like the other materialist progress it has given us, but then there’s no reason to argue about meritocracy writ large if you are already going to back the status quo. Except for the fact that from the perspective of the pro-capitalists, it’s a lot safer to argue “meritocracy: yay or nay” than to argue over “should we make ten thousand times as much as the middle of the curve, or only a hundred times as much?”

I think Matt, Scott, and Freddie all have good points at the margins, about the ways we define meritocracy and ways it is unfair or useful and can be modified. But none of those are nearly as important as the *size* of the rewards under our current system, which is what is really driving the stress and anger around this issue.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Squid Game’s Scathing Critique of Capitalism

https://ift.tt/3kOEMpF

This Squid Game article contains MAJOR spoilers.

From the very first game of ddakji out in the real world with Train to Busan actor Gong Yoo, Squid Game poses the question: how far would you go for money? How much of your body, your life, would you trade to keep the wolves at bay and to get to live the life you’ve always dreamed? Once you start, could you stop, even if you wanted to? And in the end, would it even be worth it? While Squid Game depicts an attempt to answer these questions taken to the extreme, they are the same essential questions posed to everyone living under capitalism: What kind of job, what terrible hours, what back-breaking labor, what level of abuse, what work/life imbalance will we tolerate in exchange for what we need or want to live? Unlike many examples of this genre, Squid Game is set in our contemporary reality, which makes its scathing critique of capitalism less of a metaphor for the world we live in and more of a literal depiction of life under capitalism.

Squid Game’s Workers

At the most basic level, the entire competition within Squid Game would not exist without extreme financial distress creating a ready pool of players. It’s no coincidence that Gi-hun’s hard times started when he lost his job, followed by violence against the workers who went on strike. Strike-breakers and physical violence against striking workers may feel like an antiquated idea to an American audience. South Korea, however, has something of an anti-labor reputation, with only 10% of its workers in unions and laws limiting unions to negotiating pay, among other restrictions. In the US, the anti-labor fight is alive and well, though transformed, where it takes the shape of the deceptively named “Right to Work” laws, which benefit corporations and make it harder for unions to operate.

As noted in our review, (most of) the players choose to leave and then willingly return to the arena, which separates Squid Game from other entries in the genre like the Hunger Games series and Escape Room. This element of volition contributes to the series’ primary critical goal. As Mi-nyeo and others brought up early on, they’re getting killed in the real world too, but at least inside they might actually get something for their troubles.

As an anti-capitalist parable, the only ways to fight back or upend the game in some small way are through acts of solidarity or by turning down the allure of the cash. The final clause in the game’s consent form states that the game can end if a majority of players agree to do so. After the brutal Red Light, Green Light massacre in the first, they do exactly that. The election might as well be a union vote. It’s shocking that the contract for the game included an escape clause at all, but it seems the host and his ilk enjoy at least allowing the illusion of free will if nothing else. The players who didn’t return after the first vote to leave the game, though unseen in this narrative, are perhaps the wisest of all.

Read more

TV

Squid Game’s Most Heartbreaking Hour is Also Its Best

By Kayti Burt

TV

Squid Game Ending Explained

By Kayti Burt

During tug of war, Gi-hun’s team surprises everyone by winning. Their teamwork, unity of purpose, and superior strategy help them defeat a stronger adversary, which is a basic principle of labor organizing, albeit usually not at the expense of the lives of other workers. Player 1 (Il-nam) and Player 240 (Ji-yeong) each find their own way to beat the game by essentially backing out of the competition during marbles. In exchange for friendship and choosing the circumstances of their own deaths, Ji-yeong and Il-nam each make their own, ethically sound choice under this miserable system. Il-nam gets an asterisk since he was never going to die, but he still found a choice beyond merely “kill” or “be killed” by teaching his Gganbu one “last” lesson and helping him continue on in the game.

In the end, Gi-hun confounds the VIPs and the Front Man by coming to the precipice of victory and simply walking away. Under capitalism, this group of incredibly rich men simply could not understand how someone could come so close to claiming their prize, and choose not to. But for Gi-hun, human life always had greater value. Gi-hun followed (Player 67) Sae-byeok’s advice and stayed true to himself, refusing to actively take anyone’s life, especially not the life of his friend.

Squid Game’s Ruling Class

Since the competition only exists because of the worst aspects of capitalism, it’s not surprising that in the end, it is itself a capitalist endeavor. Ultra-wealthy VIPs, who mostly seem to be white, Western men, spectate for a price and bet on the game. In their luxury accommodations, they lounge on silent human “furniture” and mistreat service staff. In one notable example, a VIP threatens to kill a server (who the audience knows to be undercover cop Hwang Jun-ho) if he doesn’t remove his mask, even though the VIP knows it would cost the server his life.

Perhaps most enraging of all is what Player 1, who turns out to actually be the Host, has to say to Gi-hun a year after the game ends. It all circles back to the game’s existential connection to economics; on the one hand, there is the unshakeable link to a population in which a significant portion of people suffer from dire financial woes. On the other hand, there is the Host and his cronies, the ultra-rich who are so bored from their megarich lives that they decided to bet on deadly human bloodsport for fun just so they could feel something again, as though they were betting on horses.

In spite of the enormous gulf between the two, the Host attempts to draw comparisons between the ultra-wealthy and the extreme poor, saying both are miserable. His little joke denies the reality of hunger, early death, trauma, and many other ways that being poor is actively harmful, both physically and mentally. It’s the kind of slow death that makes risking a quick one in the arena seem reasonable. He and his buddies were just kind of bored. Moreover, the Host denies the role of economic coercion in players taking part in the game, insisting that everyone was there of their own free will. But what free will can there be for people who owe millions, with families at home to care for and creditors at their back, when someone comes along and offers a solution, even a dangerous one? Anyone who has taken a dodgy job offer to get away from a worse one, or because they’re unemployed and the rent and college loans are due, knows that there is a limit to how truly free our choices can be when we need money, especially if there’s little to no safety net.

Read more

TV

Why Are Squid Game’s English-Language Actors So Bad?

By Kayti Burt

TV

Best Squid Game Doll Sightings

By Kayti Burt

Throughout the series, it is clear that someone had to be funding Squid Game at a high level. Unlike science fiction or fantasy takes, the show is grounded in our current reality, so the large-scale, high-tech obstacles and the island locale must have cost a pretty penny. Of course for any who see it as unrealistic, consider the example of Jeffrey Epstein, a man who bought an island from the US government and ran a sexual abuse and human trafficking ring not entirely disimilar (though far more pedestrian in its purpose) from this one.

The Host is able to pay for everything because he works in – you guessed it – banking. It’s a profession where he gained wealth by moving capital around. Given the Korean debt crisis – South Korea has the highest household debt in the world, both in size and growth – his profession makes him a worthy villain, in the same way the Lehman Brothers were after the 2008 crash. The bank executive calls in Gi-hun to offer him investment products and services, because of course someone with 45 billion won can accrue significantly more money passively, and who wouldn’t want that? Gi-hun’s decision to walk away is a callback to his earlier attempt to walk away from Squid Game when millions of dollars was within his grasp.

Throughout the series, the people running the game actively pit the players against one another in much the same way capitalism pits workers against one another. Whether they’re giving the players less food to encourage a fight overnight, the daily influx of cash every time another player dies, or giving them knives for the evening, the mysterious people pulling the strings want the players to fight each other like crabs in a barrel so they can’t work together to figure out what’s going on or take on the guys in red jumpsuits. Though there are notable examples of the players working together to succeed, it is always within the rules of the system. It is never treated as a viable or likely option for the players to team up and take the blood money literally hanging over their heads or to prevent death, merely to redirect it or choose how they will die. No, to win that, they must play the Squid Game’s rules.

In our society, this kind of worker-vs-worker rhetoric takes the form of employers telling workers their workload is harder or they can’t go on vacation or get a raise because of fellow employees who leave or go on maternity leave.. In reality, these are all normal aspects of managing a business that employers should plan for, and their failure to do so is not the fault of their workers. Much like in Squid Game, it benefits managers and owners if workers are too busy being mad at each other to have time or energy to fight the system and those who make unjust rules in the first place.

Squid Game’s Managers

The Front Man insists the game is fair, gruesomely hanging the dead bodies of those involved in the organ harvesting scheme because they traded medical knowledge for advanced intel on the game. However, like capitalism, there are many ways that the system is clearly rigged, no matter what the people at the top insist. There’s the obvious corruption in the organ harvesting ring, but even at its “purest” form, the game is not equitable. Sometimes the managers and soldiers in red jumpsuits stand by when unfair things happen, like Deok-su and his cronies stealing food. At other times, the people in charge intervene in player squabbles, like enforcing nonviolence during marbles and elections but encouraging violence at other times. They especially set things up to their own advantage, such as cutting the lights so the players couldn’t see the glass in the penultimate game, or the way they set up the election. Everyone knew how everyone else voted, they shared the total amount of money immediately beforehand, in an attempt to sway votes, calling to mind Amazon’s scare tactics before the recent unionization vote.

Read more

Culture

Squid Game Competitions, As Played By BTS

By Kayti Burt

Movies

Squid Game: Best Deadly Competition TV Shows & Movies to Watch Next

By Kayti Burt and 3 others

Ultimately, much like any manager/employer, the Front Man’s insistence on fairness has nothing to do with the actual value of equality, but rather the capitalist need to ensure betters are happy with the stakes and their chance at a favorable outcome.

Even the workers, soldiers and managers in red jumpsuits, who seem to be in charge, are ultimately only in power (and alive) so long as they serve the needs of the system. Like so many low-level managers, many wield their tiny amount of power ruthlessly, shooting players with impunity or running their organ harvesting side gig. It soon becomes clear that they’re as expendable as players, if not moreso, and the Front Man shoots them without hesitating. A player asks (and it’s too bad we never learned) what “they” did to the people in red jumpsuits to get them to run this game, but it’s not too hard to guess. They seem to be very young men, who likely needed money and wouldn’t be missed if they never returned.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

The biggest trick capitalism ever pulled was convincing workers it’s a zero-sum game, that anything we want but don’t have is the fault of someone else who “took it” from us. Within the game, that means every player was a living obstacle to the money, and that Gi-hun should kill his childhood friend to succeed and celebrate when he’s done. But as we see after he “wins,” even without taking Sang-woo’s life himself, the money isn’t worth it. The greater success would have been both men walking out of the arena alive.

The post Squid Game’s Scathing Critique of Capitalism appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3CUfVXz

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

How about Scrooge from Ducktales 2017?

Scrooge is an interesting case, I really like the character but he's also NOT a good person, and that's okay really, it doesn't mean I like the character any less

Scrooge is pretty selfish and yeah let's not forget, he's rich. He's a capitalist, he's the definition of capitalism, no matter how nice he is to his family that's always going to be a part of the character, that's always going to be his flaw, that's what's always going to make him not be a good person, yeah even if this is a cartoon world

But like I said, I do love Scrooge. I of course really love the 'cold and distant character goes softer with his loved ones' and Scrooge is also the definition of that. He definitely cares a lot about his family, and it really feels like everytime he is nice to someone he starts to consider them part of his family, especially to kids, and that's really sweet

Scrooge cares a lot about his family AND his money, those are his main prioritities. He always stops some bad guy that tries to do something evil and he of course doesn't want to see others get hurt, but Scrooge doesn't seem to care about others that aren't part of his family or friends with him and his family that much. I mean, if he did, he wouldn't be rich

And to be fair, it really seems like the relationship with his family got better because THEY tried to make things better, but he's never the first one to try to make things right. If anything goes wrong he gets sad, he gets mad, he pushes others away and he's miserable for years, but he doesn't try to fix things himself. Donald could have hated him for what happened to Della, but leaving your nephew alone with three kids for 10 years, specially knowing Donald himself really needed help emotionally and I'm sure economically as well, isn't... great. He should have helped, he should have done something, yes it's great that he searched for Della in space, but he should have also cared about his family on earth

Anyway, Scrooge isn't great but I really love him, at the end of the day he's a cartoon duck and I really could never hate him, he's fun and sweet, I just wished they could explore that side of his character more instead of always painting him as a good guy

15 notes

·

View notes

Link

March 1 – Marx’s Theory of Alienation

The alienation of labour that takes place specifically in capitalist society is sometimes mistakenly described as four distinct types or forms of alienation. It is, on the contrary, a single total reality that can be analyzed from a number of different points of view. In the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts, Marx discusses four aspects of the alienation of labour, as it takes place in capitalist society: one is alienation from the product of labour; another is alienation from the activity of labour; a third is alienation from one’s own specific humanity; and a fourth is alienation from others, from society. There is nothing mysterious about this fourfold breakdown of alienation. It follows from the idea that all acts of labour involve an activity of some sort that produces an object of some sort, performed by a human being (not a work animal or a machine) in some sort of social context.

Alienation in general, at the most abstract level, can be thought of as a surrender of control through separation from an essential attribute of the self, and, more specifically, separation of an actor or agent from the conditions of meaningful agency. In capitalist society the most important such separation, the one that ultimately underlies many, if not most other forms, is the separation of most of the producers from the means of production. Most people do not themselves own the means necessary to produce things. That is, they do not own the means that are necessary to produce and reproduce their lives. The means of production are, instead owned by a relatively few. Most people only have access to the means of production when they are employed by the owners of the means of production to produce under conditions that the producers themselves do not determine.

So alienation is not meant by Marx to indicate merely an attitude, a subjective feeling of being without control. Although alienation may be felt and even understood, fled from and even resisted, it is not simply as a subjective condition that Marx is interested in it. Alienation is the objective structure of experience and activity in capitalist society. Capitalist society cannot exist without it. Capitalist society, in its very essence, requires that people be placed into such a structure and, even better, that they come to believe and accept that it is natural and just. The only way to get rid of alienation would be to get rid of the basic structure of separation of the producers from the means of production. So alienation has both its objective and subjective sides. One can undergo it without being aware of it, just as one can undergo alcoholism or schizophrenia without being aware of it. But no one in capitalist society can escape this condition (without escaping capitalist society). Even the capitalist, according to Marx, experiences alienation, but as a “state”, differently from the worker, who experiences it as an “activity”. Marx, however, pays little attention to the capitalist’s experience of alienation, since his experience is not of the sort which is likely to bring into question the institutions that underpin that experience.

The first aspect of alienation is alienation from the product of labour. In capitalist society, that which is produced, the objectification of labour, is lost to the producer. In Marx’s words, “objectification becomes the loss of the object”. The object is a loss, in the very mundane and human sense, that the act of producing it is the same act in which it becomes the property of another. Alienation here, takes on the very specific historical form of the separation of worker and owner. That which I produced, or we produced, immediately becomes the possession of another and is therefore out of our control. Since it is out of my control, it can and does become an external and autonomous power on its own.

In making a commodity as a commodity (for the owner of the means of production) I not only lose control over the product I make, I produce something which is hostile to me. We produce it; he possesses it. His possession of what we produce gives him power over us. Not only are we talking here about the things that are produced for direct consumption. More basically, we are talking about the production of the means of production themselves. The means of production are produced by workers, but completely controlled by owners. The more we, the workers, produce, the more productive power there is for someone else to own and control. We produce someone else’s power over us. He uses what we have produced in order to wield his power over us. The more we produce, the more they have and the less we have. If I make a wage, I can work for forty or fifty years, and at the end of my life have not much more than I had at the beginning, and none of my fellow workers do either. Where has all this work gone? Some has gone into sustaining us so that we can go on working, but a great deal has gone into the expanded reproduction of the means of production, on behalf of the owners and their power. “Society” gets wealthier, but the individuals themselves do not. They do not own or control a greater proportion of the wealth.