#that ukraine was under polish-lithuanian rule

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

@claudia-de-lioncourt No no speak up, you're right and you should say it. Gabrielle de lioncourt is in the room with us right now and she might have some words too lol

@black-market-wd4o ah but dont forget... Marius thinks of himself as "sharing the wealth"! He's just helping civilization and art along by harnessing the talent of wasted youth! Amadeo is once again not very impressed.

@platoapproved You're 100% correct and let us not forget why Marius (cough Anne Rice cough) is so racist towards Armand! Let's see why ukraine keeps being depicted as less european and more backward than the rest of eastern europe throughout the book -Marius tells us right here, dimissing Amadeo's all in all quite reasonable lack of faith in the society that enslaved and abused him:

Ah. The Mongol invasions. Right. Thats when it became a dark and savage land. Gotcha. Hey quickly Marius what are your opinions on Fortress Europe.

Like look at this

"See Amadeo I care about REAL working men... bankers and merchants" bdjwjdkfbfjf

Also the absolute clownery of saying that last line to the boy he bought from a brothel. I don't care that he ends up wanting to send him to university or whatever, he admits himself that amadeo was not supposed to have any options but to be his to mold. No shit Armand feels discouraged.

#the white supremacy JUMPS out lol#listen im iranian#'we used to have a golden age where we were better and whiter but then the evil mongols/arabs invaded us'#is literally the bullshit co constructed western/pahlavi mythos about iran#(of course it goes further in the past than that with montesquieu coining persia as the og orientalist construct etc etc but you know)#iwtv#i KNOW marius is going around sprouting bs about fortress europe#he probably loves the EU#i need to kill him#not even touching upon the fact that anne rice fully bought into russian imperialism like hey#kiev rus was not a thing back then and she KNOWS this bc shes somehow aware#that ukraine was under polish-lithuanian rule#and yet she never writes the word ukraine + maintains that Warsaw is in russia#its not pure ignorance i do believe that to her its All Russia Anyway

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

VILNIUS, Lithuania — A DHL cargo plane crashed on approach to an airport in Lithuania’s capital and skidded into a house Monday morning, killing a Spanish crew member but not harming anyone on the ground. The cause of the accident is under investigation.

A surveillance video showed the plane descending normally as it approached the airport before sunrise, and then exploding into a huge ball of fire behind a building. The moment of impact could not be seen in the video.

The crash occurred at a time that Western security officials suspect that Russian intelligence is carrying out sabotage against their nations in retaliation for their support for Ukraine — including arson attacks, disinformation and by putting incendiary devices in packages on cargo planes.

In July one caught fire at a courier hub in Germany and another ignited in a warehouse in England.

Polish prosecutors said last month that parcels with camouflaged explosives were sent via cargo companies to EU countries and Britain to “test the transfer channel for such parcels” that were ultimately destined for the U.S. and Canada.

Lithuanian officials acknowledged that one line of inquiry will be whether Russia played a role given its suspected involvement in other cases of sabotage — although they stressed that there is no evidence pointing to that yet.

“Without a doubt, we cannot rule out the terrorism version,” said Darius Jauniškis, chief of Lithuanian intelligence.

“We see Russia becoming more aggressive,” he said. “But for now, we really cannot make any attributions or point fingers at anyone, because there is no information about it.”

The Lithuanian airport authority identified the aircraft as a DHL cargo plane arriving from Leipzig, Germany, a major freight hub, and one of the injured was a German citizen.

The German transportation ministry said that experts from the German Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accident Investigation would be sent to Lithuania to help with the investigation. Officials there also cautioned against trying to draw conclusions before all the evidence has been examined.

“No statements can yet be made about the cause of the accident. Whether it was an accident or whether another cause led to the crash of the cargo plane is the subject of the current investigation,” German Interior Ministry spokesperson Mehmet Atta said at a briefing in Berlin.

The head of Lithuania’s firefighting service said that the plane skidded a few hundred meters (yards), and photos showed smoke rising from a damaged structure in an area of barren trees.

“Thankfully, despite the crash occurring in a residential area, no lives have been lost among the local population,” Prime Minister Ingrida Šimonytė said after meeting with rescue officials.

Rescue workers sealed off the area, and fragments of the plane in DHL’s trademark yellow could be seen amid wreckage scattered across the crash site.

The cargo aircraft was carrying four people when it crashed at 5:30 a.m. local time. One person, a Spanish citizen, was declared dead and the other three crew members — who were Spanish, German and Lithuanian citizens — were injured, said Ramūnas Matonis, the head of communications for Lithuanian police, in an email.

The DHL aircraft was operated by Swiftair, a Madrid-based contractor. DHL said in an emailed comment that the plane “made a forced landing” about a kilometer (half a miles) from the Vilnius airport, adding: “The cause of the accident is still unknown and an investigation is already underway.” Swiftair did not comment.

“Residential infrastructure around the house was on fire, and the house was slightly damaged, but we managed to evacuate people,” said Renatas Požėla, chief of the Fire and Rescue Department.

One eyewitness, who gave her name only as Svaja, ran to a window when a light as bright as a red sun filled her room and she heard an explosion, followed by flashes and black smoke.

“I saw a fireball,” she said. “My first thought is that a world (war) has begun and it’s time to grab the documents and run somewhere to a shelter, to a basement.”

Laurynas Kasčiūnas, the Lithuanian defense minister, said “there were definitely no external factors that could have damaged the plane.”

“We can clearly see that,” Kasčiūnas said. “However, to find out what happened inside the plane, it will be necessary to interview the surviving crew members. And of course, the black box. That will take some time.”

Flight-tracking data from FlightRadar24, analyzed by the AP, showed the aircraft made a turn to the north of the airport, lining up for landing, before crashing a little more than 1.5 kilometers (1 mile) short of the runway.

Weather at the airport was around freezing at the time of the crash, with clouds before sunrise and winds around 30 kph (18 mph).

The Boeing 737 was 31 years old, which is considered by experts to be an older airframe, though that’s not unusual for cargo flights.

The prime minister cautioned against speculation, saying investigators needed time to do their job.

“The responsible agencies are working diligently,” Šimonytė said. “I urge everyone to have confidence in the investigating authorities’ ability to conduct a thorough and professional investigation within an optimal timeframe. Only these investigations will uncover the true causes of the incident — speculation and guesswork will not help establish the truth.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Republic Of Many Nations - Historical Opportunity for Central/Eastern Europe?

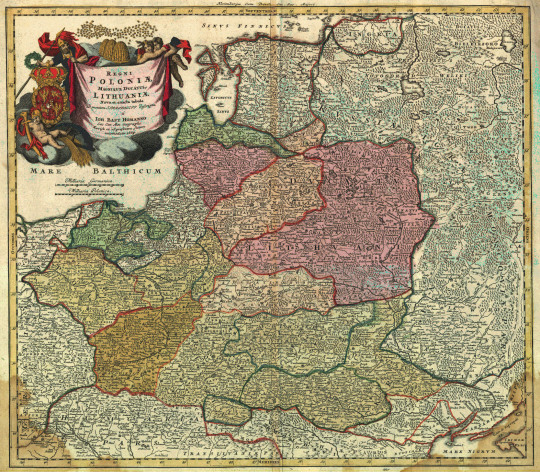

(This is a translation of an exhibition created with the cooperation of multiple Slovak and Polish institutions for the study of history that hanged in the corridors of University of Prešov in late 2023. Consider this an introduction to Rzeczpospolita for all my 1670 girlies. It's heavily biased in favor of Rzeczpospolita, luckily in ways that are neither subtle, nor do they detract from its informational value. I am leaving out most of the pictures and the commentary under them, as well as the quotes included - simply because I couldn't fit them into the format of a tumblr article. The notes bellow in [] brackets are mine, the rest of the text is from the exhibition itself, and the pictures, or something close to them - like the same building from a different angle - appeared on the exhibition panels as well. Commentary on the pictures is also from the exhibition.)

***

Did you know that from the end of the 14th century untill the end of the 18th century a unique republic existed in what is now Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine and Belarus, which was the biggest state in Europe and which wasn't founded by military expansion, but by a peaceful alliance of Kingdom of Poland and Grandduchy of Lithuania? This republic gradually fell to the pressure of surrounding absolutist monarchies led by the Tsardom of Muscovy [1], but its legacy persists in the ethos of civil liberties, democratic participation and diversity. Legacy of this republic has become a part of the identity of nations in the Middle/Eastern Europe, which for more than two centuries resisted Russian imperial rule and which cling to these values to this day.

1.) REPUBLIC OF MANY NATIONS The beginings of the "republic of many nations" can be traced to the year 1385, when the hand of Jadwiga, heir to the Polish throne, was offered to Jogaila, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, with the stipulation that he should become a Christian. When Jogaila ascended the throne of Poland as Władisław II. Jagiełło, it created a dynastic link between Poland and Grandduchy of Lithuania, which besides Lithuania consisted of lands in today's Belarus and Ukraine. When on the 1st of July 1569 in the Lublin Castle Polish nobility agreed to extend their privileges to the Lithuanian nobility in exchange for Lithuania ceding large territories to the Polish crown, an agreement was born, on the basis of which a dynastic union transformed into a commonwealth, now called Rzeczpospolita, i.e. The Republic. Though initially the union of these polities was motivated by the existence of common enemies - the Teutonic Order and later Russia - the strongest bond between them turned out to be the unique arrangement established by the Polish and Lithuanian representatives. The "Republic" in the name of this polity was supposed to demonstrate that the Commonwealth would be ruled by its noble citizens regardless of whether their mother tongue was Polish, Lithuanian or Ruthenian (common ancestor of Rusyn, Belarussian and Ukrainian). Though Republic was for hundreds of years plagued by numerous internal issues, and by the end of the 18th century it was destroyed by the aggression of its neighbours, in 1791 citizens managed to approve a unique document - Constitution of 3 May 1791, now considered the first modern constitution in Europe...

2.) STORY OF THE CROWN AND THE GRANDDUCHY Even after the Union of Lublin, the Polish Crown and Grandduchy of Lithuania were still separate states, just like they used to be for hundreds of years before that. After all, the rulers of Poland had their own archbishopric and royal title since the early 11th century, struggling for power against the likes of Přemyslids, while the grand dukes of Lithuania, attempting to revive the legacy of Kievan Rus', still hesitated whether to accept baptism from Rome or Constantinople. While many of the differences between them disappeared after the creation of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, as the Lithuanian estates adopted the lifestyles of Polish nobility, the grandduchy continued to have their own legislature in the form of so-called Lithuanian Statutes, as well as their own army and finance, and a strong sense of self-determination. However, the connection between Lithuanian and Polish society was very strong - in October 1791, shortly before the final occupation of the Republic by the Prussians, Russians and Austrians both Polish and Lithuanian representatives agreed upon The Mutual Vow Of Both Nations [2], in which they promised that the story of Rzeczpospolita should continue in perpetuity as an indelible federation of the two countries...

3.) THE STORY OF UKRAINE: A MISSED OPPORTUNITY FOR THE REPULIC? While its name points to a country "somewhere on the edge", Ukraine was a tempting target for many powers since the Middle Ages. After the fall of Mongolian Golden Horde in the 14th century, it was, as the former core of Kievan Rus' added to Lithuania, which presented itself as a continuation of this great Kievan empire. In this way, Lithuania came into the crosshairs of Muscovy, which held similar aspirations. After 1569 the Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania, which in many ways respected the distinct Ukrainian identity and unlike Moscow didn't consider it to be just a branch of the Russian nation, became its protector from the Muscovite incursion into Ukraine. Even the Polish-Lithuanian nobility living in Ukraine identified and called themselves "Ruthenians", and Grand Duchy of Lithuania used so-called Ruthenian as its official language. Cossacks living in the Wild Fields in the Dnipro river basin, who on the one hand didn't accept the autority of Polish-Lithuanian nobility, on the other hand helped to safeguard the borders of Rzeczpospolita from Moscow and the Ottomans, were also bearers of the sovereign Ukrainian identity. In the middle of the 17th century dissatisfaction of the Cossacks with certain magnates and issues of religion grew into the bloody uprising of hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky, who in 1654 turned to the Muscovite tsar [1] with a plea for protection. However, among the Cossacks, critical voices towards Moscow could also be heard, especially the voice of Ivan Vyhovsky, who in 1658 made a deal with the Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania about its transformation into the Republic of Three Nations with a coequal position of the Grand Duchy of Russia [3] and orthodoxy. Because of the opposition from a portion of nobility, Cossacks and Moscow, the agreement never went into effect, and thus both the Republic and Ukraine missed their historic chance...

4.) KING IS THE FIRST AMONG US, THE FIRST AMONG EQUALS The creation of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was also a key flashpoint for the transformation of royal power. Since Polish king Sigismund II. August, who thanks to the Union of Lublin became the ruler of Rzeczpospolita, died in 1572 without issue, Polish-Lithuanian nobility in accordance with the original agreement established the viritim election principle, according to which every noble present could elect their own king on special convocational sejms (diets). Ruler elected in this manner had to confirm noble privileges trough the so-called Henrician Articles and a collection of vows Pacta Conventa. Ruler's political power was thus perpetually subject to the rule of law (lex regnat non rex), and if the nobility deemed the ruler's actions unlawful, they could in the case of an emergency even call up a confederation and declare armed resistance. Thus, from then on until the acceptance of Constitution of 3 May 1791, the election of Polish-Lithuanian monarch became subject to the interests of foreign dynasties and local magnate houses. In the 18th century, an era during which the surrounding countries mostly adopted absolutism, the weakness of royal power came to be seen as the fundamental reason for the political decline of the Republic.

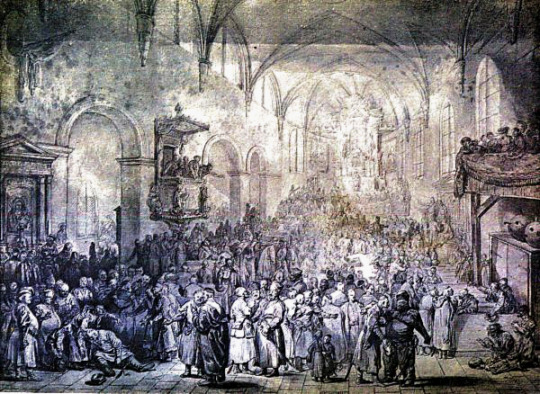

5.) NOT A MONARCHY, NOR AN ARISTOCRACY, NOR A DEMOCRACY The name Rzeczpospolita (the Republic) wasn't chosen for the Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania by accident. Polish-Lithuanian nobility actually believed that their country can revive the lost ancient legacy of the just polities, and so they considered their Rzeczpospolita, to which they had given the epithet "most serene" [2], to be the third real republic in human history (after the Roman and Venetian ones). Members of the Polish nobility, who were convinced that the noble station brings with itself the duty of civic virtues, thus positioned themselves as the new Aristotles, and considered the so-called mixed constitution, which combined virtues of the monarchy, aristocracy and rule of the people, to be the best way to organize the state. Power in Rzeczpospolita was thus divided between the elected king, the Senate consisting of highest state officials, and a chamber of noble-born representatives, who could use the later infamous liberum veto [4], or the right of individual protest, which especially in the 18th century severely hampered the flexibility of the Republic. However, in the Republic, a specific form of political decisionmaking wasn't practiced only by the parliament of nobles. In Ukraine, the Zaporozhian Cossacks created a very peculiar form of military democracy. In their fortified camps (sietches [2]) the sietch councils formed by direct election, and they in turn elected their military commanders (atamans) and government officials, made decisions about war and piece, economic policy, even legal judgements.

6.) DIFFERENT FAITHS LIVE TOGETHER WITHOUT NEED FOR BORDERS Calling the ancient Republic "Polish" might be misleading, because today the epithet "Polish" is tied mostly to the ethnic nation. However, since in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the nation was the nobility, which based its honour on citizen loyalty towards the common polity inspired by antiquity, the noble "nation" at the time included all members of the class no matter the country they were born in, language they spoke, or the faith they professed. That's why, concerning the question of self-perception in the period, we often see the phrase "I am of the Polish nation, but of Ruthenian birth." This citizenship-based definition of Polish identity was closely related to the unprecedented religious tolerance, as codified in 1573 by the so-called Warsaw Confederation. The fact that the noble "nation" included not only Catholics, Lutherans, Calvinists, Uniates and Orthodox Christians, but Mennonites and Arians, led to Rzeczpospolita being called "a state without stacks", because the foreigners there didn't end up burned at a stake, but finding a refuge. However, in the 18th century, this fragile coexistence of different denominations was severely disturbed, because the neighbouring great powers loved to use the rights of religious minorities for their own ends. In the 3 May 1791 constitution, all faiths were thus tolerated, but the Catholicism was supposed to be the state religion.

7.) POLONIA PARADISUS JUDAEORUM While the Jewish people were often banished from the rest of medieval European countries, kings of Poland granted many privileges to the arriving Jews. That being not just The Great Charter of Jewish Rights [2] from 1264, but also Privilegia de non tolerandis Christianis, which allowed Jewish merchants to settle in designated communities without Christian competition. Jews gradually gained the right to their own local administration (so-called kahalas) and around the time of the Union of Lublin even to summon their own parliament, called the Diet of the Four Countries [2] (also known as Va'ad). It is therefore no wonder that in the 16th century Europeans started to call Rzeczpospolita "Jewish paradise" and that three quarters of the entire Jewish population of the world lived here. This peaceful coexistence started to suffer in the middle of the 17th century, mainly because of Cossack uprisings, during which thousands of Jews were massacred for being alleged allies of the nobility, while in the 18th century the country experienced general decline in religious tolerance. However, as part of the attempt to save the Republic during the so-called Great Sejm [2] of 1788-1792, a special commission was created to designate the position of Jews within Rzeczpospolita. And when the famous Kościusko uprising defending the independence of Rzeczpospolita and the legacy of the Constitution of 3 May 1791 against the Russian invasion broke out, many Jews didn't hesitate to join the first Jewish regiment and fight in battle for the Republic.

8.) WALLS OF CHRISTIAN EUROPE Noble citizens didn't perceive their Republic as just an embodiment of ancient community, but also a military power. That's why the nobility placed so much value on military virtues and in emulation of ancient Sarmatians, whose descendants they considered themselves to be, they also relied heavily on elite cavalry - the winged hussars, whose exotic appearance and military prowess gained them respect on the battlefield. Polish-Lithuanian nobility, convinced of the exceptional nature of their own Republic, started to perceive their polity as "antemurale christianitatis" - the bastion of Christendom, which protects the eastern borders of Europe from the outside threat. In the 1621 battle of Khotyn the united Polish-Lithuanian army, boosted by thousands of Cossacks led by the hetman of Zaporizhzhia Sahaidachny, a great promoter of cooperation between the Cossacks and Poland-Lithuania, managed to hold back the Ottoman army several times its size. The Polish society connected several such victories to the Divine providence and a faith that the Republic is fulfilling its holy mission in history. This is also the reason why the hussars of king Jan III. Sobieski are to this day considered the saviours of Vienna from the Ottoman siege of 1683 and the madona of Czenstochowa is perceived as the one responsible for the Polish-Lithuanian victory over the Swedes. Though the military glory of the former empire had declined in the 18th century, the enlightenment era reformers didn't forget the valor of their ancestors - the School of Chivalry was established on the prompting of king Stanislaw August Poniatowsky, and among its absolvents was Tadeusz Kościuszko, born in the Duchy of Lithuania, leader of the last stand of the Republic against Russia in 1794.

9.) NOTHING ABOUT US WITHOUT US While the king od France could've said "I am the state", in the Polish-Lithuanian Union the state were its citizens, that being the nobility. Nobility's agitation for their privileges gradually bore fruit - particularly important were the neminem captivabimus privilege, ensuring untouchability of a person, and the nihil novi rule, forbidding the king from issuing laws without the approval of a diet of nobles. Power of the nobility was among other things ensured by the size of this estate, since it made up 8-10% of the population (for comparison, in Great Britain, even in the mid-19th century only 6% of the population had a right to vote). In comparison with other countries, all members of the nobility were absolute equals in the eyes of the law. All of these rules were supported by the specific ideology of sarmatism, according to which were all noblemen, as the alleged descendants of the ancient ethnic group, required to protect the so-called "golden liberties" - set of rights and values which made the Polish-Lithuanian nobility consider themselves the most free nation under the the sun. Besides the exotic clothing [5], sarmatism was also expressed in numerous acts of rebellion against their own king - for example, in the 18th century nobility founded the Bar Confederation, which was supposed to rid the Commonwealth of the Russian influence, but ended up leading to the first division of Rzeczpospolita lands among the imperial powers.

10.) SPLENDOR AND MISERY OF THE MAGNATE FAMILIES Though in the Commonwealth, any use of titles that would distinguish between lower and higher nobility was strictly forbidden, the issue was nonetheless made more complicated by the high economic inequality even among the nobles. Some noble houses were able to create estates so large even the royal holdings paled in comparison. Their dominance rested on their large wealth, high positions in state offices and background influence on politics. This informal class of magnates was most prominent in the eastern part of the country, where a handful of houses amassed giant private armies and sophisticated webs of noble clients, since many of the impoverished nobles voluntarily worked for the magnates, and some even voted in the parliament according to the wishes of their benefactors. These most powerful magnates were thus also titled "little kings", and some of them actually did become elected kings of Poland. The fact that many magnates, especially in Ukraine, were out of the reach of central state power and treated their subjects especially badly led to the outbreak of antimagnate rebellions, the most successful of which was the Bohdan Khmelnytsky Cossack uprising of 1648. However, the magnate activity cannot be seen as black-and-white, because their role also involved foundation and patronage on a grand scale - it was thanks to them that many treasures of Polish-Lithuanian architecture were created.

11.) LEGACY OF THE REPUBLIC OF MANY NATIONS The Republic of Poland-Lithuania was erased from the map in 1795. However, its tradition remained in the ethos of fight "for freedom yours and ours", which was echoed by the participants of many antirussian uprisings in the 19th and 20th century. This ethos called back to the tradition of free republic, which, unlike the Russian Empire - that forced subjugated polities to adopt the samoderzhavie [6], orthodoxy and russification triad - supposedly enabled different nations to keep their freedom and "unity in diversity". Although the ethnonationalism of the 20th century has dimmed the memories of their common legacy and caused plenty of bad blood among the different nations of former Rzeczpospolita, the idea of confederation or close cooperation against Russian imperialism was returning in their consciousness, whether during the 1863 uprising or shortly after World War I. In the communist era, the writer in exile Jerzy Giedroyc famously prophesized that Poland can be truly free only when so are Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine. For Ukrainians and Belarussians, who have been threatened by the imperial idea of Greater Russia and the vision of a unified "Russian world" even after 1991, are heroes (like prince Konstanty Ostrogski or hetman Sahaidachny) and famous moments in the history of the Republic fundamental symbols of their national sovereignty and belonging to the European civilizational space. They will never cease to remind everyone that the Republic is not dead while we are alive and believe that the ties of mutual civic loyalty are stronger than differences in language, faith or ethnic origin, stronger than any enemy that would attempt to tear these ties of our values.

***

[1] - Russia. They are talking about Russia. Y'see, the etymology of "Russian" in Eastern Slavic languages is kinda confusing; originally, it meant all Eastern Slavs, but later on it came to be associated with the largest and most culturally dominant group - which is to say the predecessors of modern Russians under the rule of Princedom of Muscovy. Eventually, Ivan IV., the Grand Prince of Muscovy got himself crown the Tsar of All Russians, which was a bit presumptuous considering a whole lot of people who very much weren't under his rule also identified as the Rus'/Russians. Still, it stuck, and when Ukrainians and Belarussians wanted to define themselves against their Russian overlords, they abandoned the label "Russians" altogether. Calling post-Ivan the Terrible Russians "Muscovites" is a bit of antiquated terminology that would be common in Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

[2] - Literal translation, because I don't know what it's called in English-speaking historical literature.

[3] - Used here in the older sense of the word, i.e. Eastern Slavic in general (see [1]). In this case, the Eastern Slavs in question are clearly mostly Ukrainians despite being called Rus'/Russians (YES I KNOW)

[4] - Okay, so have you seen the first episode? The whole "One of us was against. End of story. We have a democracy." thing was... Barely an exaggeration to be honest.

[5] - Compare the shit Jan Paweł and his friends wear to normal 17th century male clothing (to which Ciesław and especially magnate's son come pretty close to) and you'll get the gist.

[6] - rus. autocracy, or rather the name for specific absolutist tradition of Russian tzars

***

Notes on the pictures:

1.) Map of Rzeczpospolita from the first half of the 18th century (most likely around 1739), made by the cartographer Johann Baptist Homann.

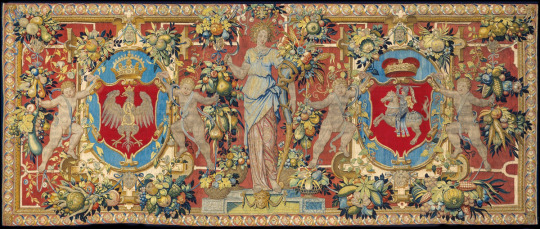

2.) Tapestry with the coats-of-arms of Poland and Lithuania - The Union of Lublin led among other things to the joining of Polish and Lithuanian coats-of-arms, so the new state coats-of-arms combined the polish royal eagle on red field with the traditional symbol of Lithuania, the Pogoń (Vytis in Lithuanian), or the armored knight on a horse, which to this day is part of the legacy of the Grandduchy in modern Lithuanian and parts of Belarussian society.

3.) Battle of Orsha (1514) in which the orthodox prince Konstanty Ostrogski, claiming to carry on the legacy of the Kievan Rus', led the united Polish-Lithuanian forces and destroyed the Muscovite invasion army despite being outnumbered, saving the independence of the Grandduchy. After 1991 the day of the anniversary of this battle was celebrated as a holiday of the Belarussian army. The holiday was later abolished by the Lukashenko regime, one can currently end up in jail for celebrating it. In 2017, a common Lithuanian-Polish-Ukrainian brigade was named hetman Ostrogski.

4.) Royal Castle in Warsaw - Since the late 16th century, Warsaw became the new center of power in the Republic. The Royal Castle, originally the medieval seat of the dukes of Massovia, was rebuilt in the new baroque style. During World War II, the castle was completely destroyed. For a long time, the communist regime was refusing to greenlight its reconstruction, and its restoration based on old engravings and pre-war photographs was only made possible trough the massive public pressure.

5.) Painting of the French artist Jean-Pierre Norblin portrays a traditional part of the political life in Rzeczpospolita - a session of the so-called sejmik (Polish diminutive of sejm, a.k.a. diet). On these local assemblies of nobles of the given region, deputies for the meetings of the central sejm were elected and instructions for these deputies were agreed upon.

6.) Kruszyniany - Presence of the muslim Tartar community is part of the legacy of Rzeczpospolita. Tartars live on the territories of today's Lithuania, Belarus and Poland continuously since the 14th century. They have proven their worth as warriors in service of the Republic. Original Tartar mosques can be found especially in Podlesie in today's northeastern Poland and in Trakai in today's Lithuania.

7.) Ceiling of a synagogue reconstructed for the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw, which in 2015 was awarded the title of Best Museum in Europe. It is in this modern museum that you can learn the most about the Jews of Rzeczpospolita, the largest Jewish diaspora at the time.

8.) Sobieski at Vienna - Painting of Jan Matejko depicts the Polish king Jan III. Sobieski, who after his famous triumph over the Ottoman Turks in 1683 sent a letter to pope Innocent IX., in which he writes that the Christian Vienna was saved.

9.) Casimir Pulaski, later national hero of the United States, escaped Poland after the failure of the Bar Confederation in 1769-1772. The confederation was one of the last attempts to free the country from the increasing dependency on Russia.

10.) Zamoćś - Renessaince city founded by an exceptional person. Jan Zamoyski came from a not very wealthy noble family, but trough his own merits eventually became the richest and most powerful man in the Republic. The town hall of Zamość on the photo.

11.) Adam Mickiewicz could be the symbol of the common legacy of Rzeczpospolita. The greatest poet in the Polish language literature was born in today's Belarus (1798) and always felt like a citizen of Rzeczpospolita. His most important work begins with a line "Lithuania, my fatherland!" It was Mickiewicz who was remembered by the pope John Paul II., when he proclaimed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth the predecessor of cooperation of the entire continent within the European Union ("from the Union of Lublin to the European Union").

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s been a year since Russia invaded Ukraine, and the battle continues.

Military and civilian deaths and injuries on both sides have been estimated in the hundreds of thousands, and millions more Ukrainians have been displaced.

What set the stage for today’s conflict? Here’s a look back at the long, intertwined history of the contentious neighbors.

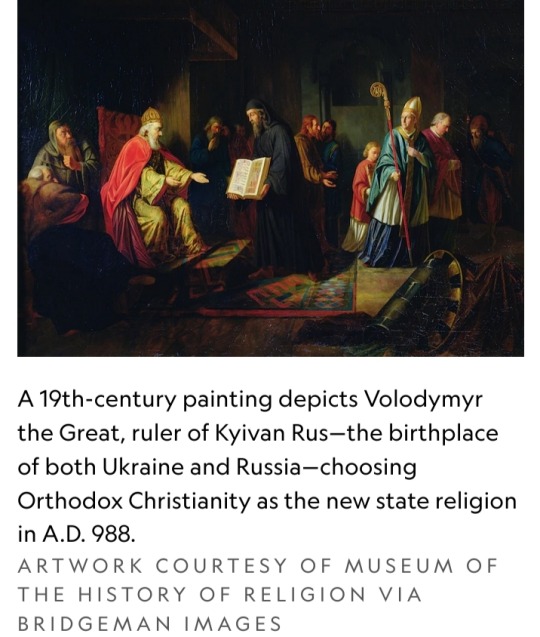

The two countries’ shared heritage goes back more than a thousand years to a time when Kyiv, now Ukraine’s capital, was at the center of the first Slavic state, Kyivan Rus, the birthplace of both Ukraine and Russia.

In A.D. 988, Volodymyr the Great, the pagan prince of Novgorod and grand prince of Kyiv, accepted the Orthodox Christian faith and was baptized in the Crimean city of Chersonesus.

From that moment on, Russian leader Vladimir Putin recently declared, “Russians and Ukrainians are one people, a single whole.”

Yet, over the past ten centuries, Ukraine has repeatedly been carved up by competing powers.

Mongol warriors from the east conquered Kyivan Rus in the 13th century.

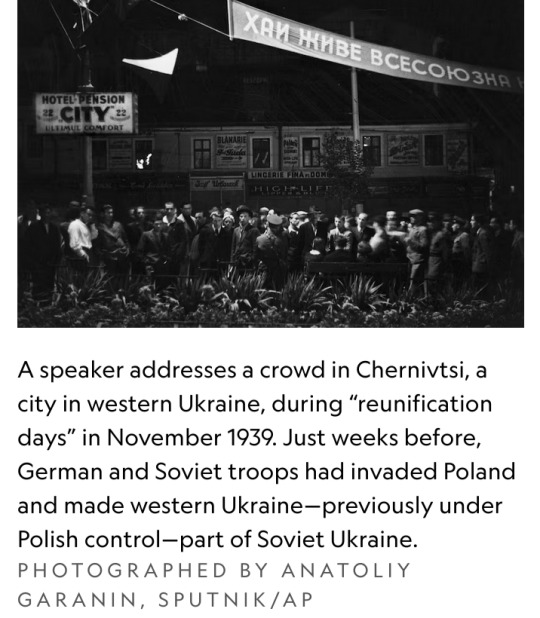

In the 16th century, Polish and Lithuanian armies invaded from the west.

In the 17th century, war between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Tsardom of Russia brought lands to the east of the Dnieper River under Russian imperial control.

The east became known as "Left Bank" Ukraine; lands to the west of the Dnieper, or "Right Bank," were ruled by Poland.

More than a century later, in 1793, right bank (western) Ukraine was annexed by the Russian Empire.

Over the years that followed, a policy known as Russification banned the use and study of the Ukrainian language, and people were pressured to convert to the Russian Orthodox faith.

Ukraine suffered some of its greatest traumas during the 20th century.

After the communist revolution of 1917, Ukraine was one of the many countries to fight a brutal civil war before being fully absorbed into the Soviet Union in 1922.

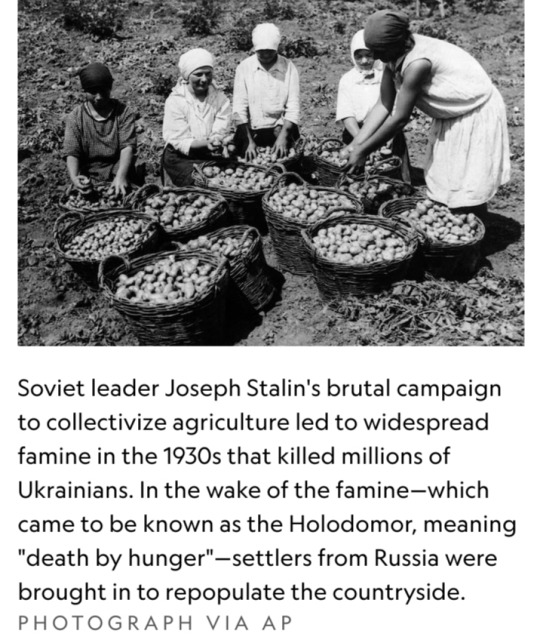

In the early 1930s, to force peasants to join collective farms, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin orchestrated a famine that resulted in the starvation and death of millions of Ukrainians.

Afterward, Stalin imported large numbers of Russians and other Soviet citizens—many with no ability to speak Ukrainian and with few ties to the region—to help repopulate the east.

These legacies of history created lasting fault lines. Because Eastern Ukraine came under Russian rule much earlier than western Ukraine, people in the east have stronger ties to Russia and have been more likely to support Russian-leaning leaders.

Western Ukraine, by contrast, spent centuries under the shifting control of European powers such as Poland and the Austro-Hungarian Empire — one reason Ukrainians in the west have tended to support more Western-leaning politicians.

The eastern population tends to be more Russian-speaking and Orthodox, while parts of the west are more Ukrainian-speaking and Catholic.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine became an independent nation. But uniting the country proved a difficult task.

For one, “the sense of Ukrainian nationalism is not as deep in the east as it is in west,” says former ambassador to Ukraine Steven Pifer.

The transition to democracy and capitalism was painful and chaotic. Many Ukrainians, especially in the east, longed for the relative stability of earlier eras.

"The biggest divide after all these factors is between those who view the Russian imperial and Soviet rule more sympathetically versus those who see them as a tragedy," says Adrian Karatnycky, a Ukraine expert and former fellow at the Atlantic Council of the United States.

These fissures were laid bare during the 2004 Orange Revolution in which thousands of Ukrainians marched to support greater integration with Europe.

On ecological maps, you can even see the divide between the southern and eastern parts of Ukraine—known as the steppes—with their fertile farming soil and the northern and western regions, which are more forested, says Serhii Plokhii, a history professor at Harvard and director of its Ukrainian Research Institute.

He says a map depicting the demarcations between the steppe and the forest, a diagonal line between east and west, bears a "striking resemblance" to political maps of Ukrainian presidential elections in 2004 and 2010.

Crimea was occupied and annexed by Russia in 2014, followed shortly after by a separatist uprising in the eastern Ukrainian region of Donbas that resulted in the declaration of the Russian-backed People’s Republics of Luhansk and Donetsk.

Today, the two countries find themselves in conflict yet again, fault lines that reflect the region's tumultuous history.

Portions of this article were originally published during the 2014 Crimean crisis. It has been updated to reflect current events.

#Ukraine#Russia#Kyiv#Kyivan Rus#Volodymyr the Great#Vladimir Putin#Russification#Joseph Stalin#2004 Orange Revolution#Volodymyr Oleksandrovych Zelenskyy#Volodymyr Zelenskyy

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

In a speech in Warsaw on Tuesday, U.S. President Joe Biden praised his Polish hosts for their foresight on the threat posed by Russia and their contributions to defending Ukraine. “Thank you, thank you, thank you for what you’re doing,” Biden said. But post-communist Poland hasn’t only been a success on matters of diplomacy and security. It has also been the most successful economy in Europe, in relative terms, since 1989—more dynamic not only than other Eastern European countries but also Europe’s big heavyweights France and Germany. That economic story is a central part of Poland’s growing influence on the continent and in the world more broadly.

How has Polish history shaped its economic identity? What factors have fueled its economic rise? And to what degree has its economic success been helped, or hindered, by its populist governments? Those are a few of the questions that came up in my recent conversation with FP economics columnist Adam Tooze on the podcast we co-host, Ones and Tooze. What follows is an excerpt, edited for length and clarity.

For the full conversation, look for Ones and Tooze wherever you get your podcasts.

Cameron Abadi: Poland has a remarkable history. It was wiped off the map in the 18th century and invaded from both directions, by Germany and Russia, in the 20th century. How has that longer-term history shaped its present-day political and economic identity?

Adam Tooze: Yeah, it’s a truly staggering history. If you look at an early modern map—a map of Europe in, say, 1600—then the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was in fact the dominant power of Central and Eastern Europe. But the 18th century is a disaster. Poland ends up being divided between an ambitious Prussia, the Habsburgs, and the Russians. So, for a new Poland to emerge, which is the story of the 20th century, it basically needs a hegemonic patronage of one of those three powers, or it needs all three of them to be defeated, a kind of miracle.

And that’s precisely the miracle that transpires at the end of World War I. All three of them are defeated in sequence. First the Russians, then the Hapsburgs and the Prussians within days of each other. And by the end of 1918, Poland is established as a national unit. But it was, as you were saying, overtaken again by the aggression of its neighbors, smashed and divided between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in 1939. And then you have a new phase of economic and social development under communism, which—well, of course, what we know about communism in the long run is that it’s an economic failure, but it wasn’t from the start. And for better and for worse, one thing that Soviet-era dominance and the common rule of the Soviet Communist Party did, it industrialized Poland, it urbanized Poland, and it set a much higher bar for Polish education. The percentage of Poles in university increased tenfold between the interwar period and the 1970s. It laid the grounds for the modern Polish success story that we’re focusing on, this incredible period of growth with a Poland inserted into, on the one hand, the European Union and, on the other hand, NATO.

But the scars of this history do linger. And that then creates this space not just for coming to terms with real lived trauma but also the politics of Polish nationalism, which, especially since the election of the Law and Justice party in 2015, now dominates the Polish political scene. This nationalism has opened up a variety of historical legacies simultaneously: the reparations issue with Germany, where Poland is demanding over 1 trillion euros in reparations for the damage done to Poland during the German occupation, but also now, of course, the confrontation with Russia over its attack on Ukraine. One interesting effect of all of that is that long-standing, historic legacies of tension between Poland and Ukraine—which fought wars with each other at the end of World War I, in the phase in which both of them were struggling for independence—have been papered over and buried so that Ukraine and Poland are now closely allied in the struggle against Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

CA: When you get into the details of Poland’s development, it seems to have relied a lot on foreign direct investment—foreign firms setting up manufacturing hubs across the country. How much does this success have to do with specific policy choices that Poland has made versus simply the good luck of being geographically adjacent to the EU economic heavyweight that is Germany?

AT: I think the geographical factor is no doubt highly significant because it can’t be ignored that practically all of the former communist Eastern European states, all of which are more-or-less close to Germany and to the EU, have all done quite well. So Poland is the standout case with a growth rate since 1989 of 179 percent. But take Lithuania or Latvia or Slovakia, and they’ve all achieved 125-130 percent growth. Romania achieved a doubling of output. Slovakia, Chechnya, Hungary—which were much better off than Poland in 1990—grew by 70 percent. So everyone in that zone has achieved a relatively successful transition by comparison with, for instance, Belarus or Ukraine or indeed even Russia. And they were all, in that sense, relatively well placed. I think that’s important. I think it’s important also to be clear that Germany is a big part of this. Germany accounts for 26 percent of Polish exports, which is five times more than the next-placed country, which would be the Czech Republic and then the United Kingdom at 5 to 6 percent each.

So Germany is a key part of the Polish success story—but only in the context of Europe as a whole. So you spoke about foreign direct investment. There’s about 40 billion euros’ worth of German foreign direct investment in Poland, and that’s by comparison with the 140 billion euros that have been pumped into Poland since 2004 by the EU as a whole. So the EU matters more here.

If you ask in what ways did the Polish policies themselves inflect this, Poland is bitterly divided over what you might think would be an economic success story. And the current incumbent nationalist party is a party of ideological warfare. They campaigned on the slogan, believe it or not, “Poland in Ruins.” So what is at stake here? Well, the advocates of the Polish success story say that what Poland imposed after communism was shock therapy—they liberalized prices, they let the market rip, they allowed a wholesale destruction of communist-era economic security, a huge surge in unemployment, the bankruptcy of a whole bunch of Polish businesses—but what they crucially didn’t do was privatize early on. So they avoided the formation of the baneful system of oligarchs that we saw in Russia and many of the post-Soviet states: Ukraine, Belarus, and so on.

This is the story as the boosters of the Polish success story tell it. But what can’t be discounted is that there is a counternarrative that sees the ’80s and the ’90s—for all of the apparent success of the transition to capitalism, to Europe, and to democracy—as in fact a corrupt sellout, not on the scale of Russian chaos in the 1990s but nevertheless a subversion of the new Polish order by the corrupt holdovers of the communist period. And without reckoning with this difference of narratives about what, on the basis of the macroeconomic data, looks like a spectacular success story, you can’t understand how savage Polish politics has been in the last 15 years. The Law and Justice party has that name because it believes that those are the things that are at stake. I mean, in the West, we regard it as an unjust party that subverts the rule of law. But in their own terms, they understand themselves as bringing a new order and an end to the corrupt long-term legacies of the botched transition.

CA: The Law and Justice party has been in power for several years, and it has also presided over continued economic growth. To what extent is its economic success traced to its populist status exactly? Are there specific populist platforms or ideas that have proved economically successful?

AT: It’s really an interesting question, and I think it sort of raises the question of how we link short-run economic measures, welfare measures, and economic growth. I mean, the populists in Poland have been lucky in that they’ve inherited a growth engine, and that’s continued to work with considerable dynamism and has powered the Polish economy over the long run. And so, to that extent, I think we should probably separate that logic of economic growth from the comings and goings of governments and the policies they adopt.

It’s also true that they have, however, adopted significant welfare policies. So they came into power promising to rescue their country, widely regarded as an economic success story, from the ruins that had been created by the decades of unequal pro-Western growth since the 1990s. And they promised to do this by lowering the retirement age, rolling it back from 67 for both men and women to 65 for men and 60 for women. Expanding family benefits, they created this 500 zloty—which is about a 110 euros a month—payment for families with more than with two kids and upwards. And then they also set about building new apartments on state-owned land, a kind of program of investment, a redistribution. And it’s not inconceivable that welfare spending could in various ways enhance the growth potential of a country. It could help build human capital. In the health sector, it could be the driver of technological change. But this sort of spending really doesn’t fall into that category. It’s hard to see how any of these measures could really increase Poland’s long-run growth rate.

So I think really what we’re talking about now in Poland is a sort of subtle balance of a growth machine shaped in the 1990s that at least has some distance to run still—there’s that story. And then there’s a story essentially that is driven by the toxic politics of the aftermath of communism in Poland on the one hand and on the other hand the story of regional and social inequality. And if you dig down, if you really dig into the data, it’s pretty obvious that the drama here is that Polish society since the 1990s has experienced truly dramatically diverging fortunes. If you look at the top 1 percent of Polish society, their incomes have more than quadrupled—they probably increased by 450-odd percent. So what we’re really talking about is a society not unlike others in the world since the 1990s but a particularly extreme case of a society that was once relatively solidaristic under communism and has now been divided in really quite fundamental ways by economic growth.

And what the populist politics quite precisely identifies are those gaps, those spaces in between, and sets about remedying them in a rather direct way. One of the extraordinary things about Polish politics recently is people are just not afraid to buy votes. They wave a benefit and get votes for it, which is in some ways a degeneration of democracy. But it speaks to a very specific need. But it seems quite unrelated to the underlying growth dynamic that feeds it.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

9 famous castles of Ukraine — witnesses of noble past

Castles are among the most interesting historical monuments in Ukraine. According to researchers, there were more than 5,000 fortifications in Ukraine, but most of them are gone today. To date, 116 Ukrainian strongholds have fully or partially survived.

Though inanimate and silent, having belonged to different state territories and nations in the past, these castles still tell their stories as witnesses of crucial events in European and Ukrainian history. Now they constitute Ukrainian heritage to be cherished and preserved. In this publication, we would like to tell you about the nine most famous castles in Ukraine.

Kamianets-Podilskyi Fortress

The first wooden fortification in Kamianets refers to the 11th century, later rebuilt in stone. In the 14th century, it acquired a contemporary look. Only twice in its history, the fortress has been conquered: in 1393 by Lithuanian Prince Vytautas and in 1672 by a large Turkish army that remained here until 1699. Kamianets-Podilskyi Fortress lost its defensive significance after the end of the Russo-Turkish War of 1812 — when the borders of the Russian Empire expanded significantly to the south. At that time, the fortress served as a prison. However, during the two world wars, it was used as a fortification again.

Kamianets-Podilskyi Fortress is well-preserved to this day. It occupies 1.5 hectares and consists of eleven towers arranged in an irregular quadrangle and connected by fortress walls. For its architectural ensemble that has no analogy in Europe, Kamianets-Podilskyi Fortress is included in the UNESCO World Heritage Site Tentative List.

Khotyn Fortress

The first reliable fortifications, in the form of a rampart with wooden barriers and a moat dug across the rocky cape, appeared in Khotyn at the turn of the 10th and 11th centuries. After annexing this territory to Rus, Kyivan Prince Volodymyr the Great started building new fortresses as centers of princely power and places of residence for governors.

In 1621, Khotyn witnessed the war between the Ottoman Empire and Poland, in which the Ukrainian Cossacks played a crucial role. The victory at Khotyn saved Western Europe from the Turkish invasion.

Khotyn Fortress has survived to this day in an authentic state. Today, it is a state historical and architectural reserve. Knight Tournaments “Battle of Nations” are often held here, and historical films are shot.

Akkerman Fortress

Akkerman Fortress, or White Fortress, is a unique monument of fortification architecture of the 13th-15th centuries.

The fortress was under Turkish rule for more than 300 years. In 1789, Akerman came under the control of Russian troops and gradually lost its military and defense function. The historically formed planning and spatial structure have mostly been preserved to modern days. Since the early 20th century, restoration work has been carried out here to adapt this historical and architectural complex for cultural and tourist purposes.

Mukachevo Palanok Castle

Mukachevo Palanok Castle was built on the crossroads of ancient trade and military routes at the end of the 13th century. It served as a stronghold for the northeastern part of the Hungarian Kingdom and Austrian Empire. Overcoming sieges and wars, Palanok Castle is one of only five fortresses in Europe that have never been seized by a storming attack. The castle consists of 130 different rooms with a complex system of underground passages connecting them. Currently, it houses a museum dedicated to the history of Mukachevo and the castle.

Olesko Castle

The 600-year-old Olesko Castle near Lviv belonged at different times to Lithuania, Poland, and Hungary and witnessed constant battles for ownership. It is the birthplace of Polish Kings — Jan III Sobeski and Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki.

Today, it is a museum featuring collections of antique furniture and art, tapestries, ancient weapons and everyday life items from the 16th and 17th centuries. This collection is considered one of the richest treasuries of Polish art outside of Poland.

Pidhirtsi Castle

This residential castle-fortress was erected 80 km east of Lviv in the 17th century for the Polish Grand Crown Hetman Stanislaw Koniecpolski. Above the entrance gate, a marble plaque to this day bears a Latin inscription: “A crown of military labors is victory, victory is a triumph, triumph is rest.” The interior of the castle saw Polish Kings and military commanders.

During World War I, its splendor suffered devastation and looting by Russian troops. Soviet authorities opened a tuberculosis sanatorium there after World War II. Nowadays, Pidhirtsi Castle is in the register of 100 world monuments that need immediate restoration.

Svirzh Castle

Svirzh Castle was built under the patronage of the influential Svirzh family in the 15th century. Only fragments of the foundation and lower walls have survived from that heroic period. When the castle was owned by the Zetner family (second half of the 17th — early 19th centuries), the castle complex acquired a modern look, transforming from a purely defensive structure into a cozy residence.

The owners cherished and persistently revived their estate from the ruins during the Cossack wars and the Polish-Turkish confrontation and saved it from vandalism by Russian troops. The last of the noble family, Ignacy Zetner, created a magical park around the castle. During World War I, the Svirzh Castle became the center of active hostilities, and as a result, it stood in ruins for more than 30 years. The restoration of the castle began only in 1975. Now, Svirzh Castle is reopened for tours. It is planned to create a cultural and artistic center here.

Lutsk Castle

Lutsk Castle, also known as the Castle of Lubart, was founded in 1340 when Lithuanian Prince Lubart ordered the construction of stone walls instead of wooden ones that had existed since 1000. In 1366, the city of Lutsk was captured by Polish troops, and since then, Lutsk has become both the permanent residence of the prince and the capital of the principality.

The reliability of the fortress was well-known in European countries, so it is not surprising that it was here, in the Upper Castle in Lutsk, that the Congress of Monarchs was held in 1429 — 15,000 people came to Lutsk to discuss the most burning political and economic issues of the time.

Lubart’s Castle withstood numerous assaults and sieges, but over time, the lack of financing to maintain the castle caused the defensive structure to decay. It lost its fortification function and served only to house the administration and courts.

Now, Lutsk Castle is a symbol of the city, attracting visitors to various festivals and cultural events. The Entrance Tower of Lutsk Castle is depicted on the 200 UAH bill.

Uzhhorod Fortress

The foundation of the castle in Uzhhorod dates back to the 9th century and is associated with the legendary Hungarian Prince Laborets. In the 10th century, the territory of the citadel was conquered by the Hungarians, who began to build a new structure. In the early 14th century, King Charles Robert granted the castle to the Italian family of Drugeti. The Drugeti counts owned the palace for almost four centuries. They invited Italian craftsmen to rebuild the castle — strong fortification walls were erected, and the complex acquired a Renaissance style. From the end of the 17th century, Uzhhorod Castle passed into the hands of Hungarian count Miklós Bercsenyi, who, together with his wife, turned it into a pompous count’s residence, the center of the cultural and political life of the region. In the middle of the 18th century, the palace housed a theological seminary until the arrival of Soviet troops in the 1940-s.

From 1947 till nowadays, the castle has been a local history museum that contains the largest collection of bronze treasures and Celtic antiquities in Ukraine, a numismatic collection, rare manuscripts and printed books, embroidered shirts, folk clothes, and folk musical instruments of Transcarpathia, cold steel and firearms of the 16th-20th centuries.

Text: Liubov Pikulia Design: Vladyslav Rybalko

0 notes

Text

Russia and Ukraine have a complex and contentious history. Here's a brief overview:

Historical Background: Ukraine has a rich history and a distinct cultural identity. It was part of various Eastern Slavic state formations throughout the centuries, including the Kyivan Rus, which was a predecessor to both Russia and Ukraine. Ukraine later fell under the rule of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Russian Empire.

Soviet Era: After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Ukraine experienced a period of independence from 1917 to 1921, but it eventually became part of the Soviet Union in 1922. During the Soviet era, Ukraine went through significant political and demographic changes, including the 1932-1933 Holodomor, a man-made famine that resulted in millions of deaths.

Dissolution of the Soviet Union: With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine gained independence. However, the dissolution led to challenges, including economic difficulties and political instability. Ukraine sought to establish its own identity and pursue a path separate from Russia.

Crimea Annexation: In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea, a region that was previously part of Ukraine. The move was widely condemned by the international community, and it sparked a conflict between Russia and Ukraine.

Conflict in Eastern Ukraine: Since 2014, an armed conflict has been ongoing in eastern Ukraine between Ukrainian government forces and Russian-backed separatists. The conflict has resulted in thousands of deaths and displacement of people. Several ceasefire agreements have been reached, but the situation remains unresolved, with sporadic clashes occurring.

International Relations: The conflict in Ukraine has strained relations between Russia and the West, particularly the United States and European Union. Sanctions have been imposed on Russia, and diplomatic efforts have been made to find a peaceful resolution to the conflict.

It's important to note that this is a simplified overview, and there are many nuances and complexities involved in the relationship between Russia and Ukraine.

Gas Disputes: Russia is a major supplier of natural gas to Ukraine and Europe. Disputes over gas prices and transit fees have occurred between Russia and Ukraine in the past, leading to disruptions in gas supplies to Ukraine and, subsequently, to parts of Europe. These disputes have often been intertwined with broader political tensions.

Cultural and Linguistic Differences: Ukraine has a distinct culture and language. While Ukrainian is the official language, Russian is widely spoken, especially in eastern and southern regions where there is a significant Russian-speaking population. The language issue has sometimes been a source of tension and political debate within Ukraine.

Geopolitical Considerations: The conflict in Ukraine is seen by many as a manifestation of broader geopolitical rivalries between Russia and the West. Ukraine has sought closer ties with the European Union and NATO, which Russia views as a threat to its influence in the region. The West has provided political and economic support to Ukraine, but there are divisions among Western countries on the approach towards Russia.

Humanitarian Impact: The conflict in eastern Ukraine has had a significant humanitarian impact. It has resulted in casualties, displacement of people, damage to infrastructure, and disruption of daily life for many residents. Humanitarian organizations have been providing assistance to those affected by the conflict.

Minsk Agreements: The Minsk agreements, signed in 2014 and 2015, aimed to establish a ceasefire and a political resolution to the conflict in eastern Ukraine. However, full implementation of the agreements has been challenging, and the conflict has continued, with periodic escalations and violations of the ceasefire.

International Diplomatic Efforts: Various countries and international organizations have been involved in diplomatic efforts to resolve the conflict, including the Normandy Format (involving Ukraine, Russia, France, and Germany) and the Trilateral Contact Group (Ukraine, Russia, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe). These efforts have aimed to facilitate dialogue, ceasefire implementation, and a peaceful resolution.

Crimea's Status: The annexation of Crimea by Russia in 2014 has led to a significant shift in the region's status. Russia considers Crimea as part of its territory, while Ukraine and most of the international community continue to view it as an integral part of Ukraine. The annexation has not been recognized by the United Nations or many countries around the world.

Donbass Region: The conflict in eastern Ukraine primarily revolves around the Donbass region, which includes the Donetsk and Luhansk provinces. These areas have seen heavy fighting between Ukrainian government forces and separatist groups supported by Russia. The conflict has resulted in a de facto separation of these territories from the rest of Ukraine, with the creation of self-proclaimed entities known as the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic.

Human Rights Concerns: The ongoing conflict has raised significant human rights concerns. There have been reports of human rights abuses, including civilian casualties, displacement, torture, and arbitrary detentions. Both Ukrainian forces and separatist groups have been accused of committing such violations, and international human rights organizations have documented these abuses.

Economic Interdependencies: Ukraine and Russia have deep economic interdependencies, including trade relations and energy cooperation. Ukraine is an important transit route for Russian gas exports to Europe, and Russia has used gas supplies as a political lever in the past. Efforts have been made to diversify Ukraine's energy sources and reduce its dependence on Russian gas.

Cyberattacks and Information Warfare: Russia has been accused of engaging in cyberattacks and information warfare targeting Ukraine. These activities include hacking, disinformation campaigns, and the spreading of propaganda. Cybersecurity concerns and the manipulation of information have become significant challenges in the region.

Crimea Bridge: In 2018, Russia completed the construction of the Crimean Bridge, connecting the Russian mainland to Crimea. The bridge has faced criticism from Ukraine and the international community as it reinforces Russia's control over the region and undermines Ukraine's territorial integrity.

Ongoing Negotiations: Efforts to find a peaceful resolution to the conflict continue through negotiations and diplomatic channels. However, progress has been slow and hindered by ongoing hostilities and divergent positions between the parties involved.

These points provide a broader understanding of the Russia-Ukraine dynamics, but it's important to note that the situation is complex and evolving. The geopolitical landscape and events may have changed.In conclusion, the relationship between Russia and Ukraine is characterized by a complex and contentious history. Ukraine gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 but has faced numerous challenges in its efforts to establish its own identity and pursue a path separate from Russia. The annexation of Crimea by Russia in 2014 and the ongoing conflict in eastern Ukraine have further strained their relationship.The conflict in eastern Ukraine, primarily centered around the Donbass region, has resulted in casualties, displacement, and significant humanitarian concerns. The international community has condemned Russia's actions and provided support to Ukraine, while diplomatic efforts have aimed to find a peaceful resolution.The situation is influenced by broader geopolitical considerations, with Ukraine seeking closer ties with the European Union and NATO, seen as a threat by Russia. Gas disputes, cultural differences, and human rights concerns also contribute to the complexities of the relationship.Efforts to resolve the conflict have been ongoing, with negotiations and diplomatic initiatives such as the Minsk agreements. However, challenges remain, and the situation is fluid, with periodic escalations and violations of ceasefires.It is important to note that this conclusion provides a summary of the key points discussed and the general state of the Russia-Ukraine relationship. The dynamics and developments in the region can change rapidly, and it is essential to stay informed about the latest updates from reliable sources.

0 notes

Text

Why intersectional theory doesn’t fit the description of ethnic discrimination in Eastern Europe (longread - I don't know if you will read this, but I think it's important)

Disclaimer 1: I am a historian, not a sociologist, and this affects my analysis. Disclaimer 2: I know best the history of the Russian Empire and least of all the Ottoman history. As we know, intersectional theory emerges from the concepts of "privilege" and "oppression". There are social categories that have greater access to benefits (education, good income, representation in art and media, etc.), and there are those that are oppressed for certain essentialist reasons, although the reasons are actually socially constructed (non-white skin color, non-straight sexuality, but you know about this without me). It’s important that such a system has been established for centuries, starting from about Early Modern times.

Intersectional theory is aimed at increasing the diversity of discourse and representing as many identities as possible in society. Also, the theory assumes a description of the intersections of various discrimination, where race, class, gender and sexuality aren’t separated from each other, but together form a person's identity. But ironically, this theory is very Americancentric, as it stemmed in large part from racial conflicts in the United States. It’s also partly Western Europeancentric, and includes mainly such colonial relations as between Britain and India, France and Algeria, etc.

But on the example of countries on the territory of the former Russian, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, it doesn’t work well, and here's why.

Mostly, the intersectional theory assumes the same type of conflicts and relations (racial, class, gender) in society over the centuries, which began to be established precisely in the late 15th - early 16th centuries, and this isn’t at all obvious for Eastern Europe.

Eastern Europe has distinguished itself by its "long" feudalism. Feudalism, on the other hand, means political fragmentation instead of absolutism, a greater concentration on religious affiliation (hello to the beginning of secularization in Western Europe) and the priority of status over class. Yeah, in capitalism it was difficult for a peasant to become a worker, and a worker (even more difficult) to become a small entrepreneur. But feudalism, in principle, doesn’t imply any social mobility - everyone is literally obliged to remain within the framework of their social strata.

Thus, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth remained de facto politically fragmented up to partitions in 1795. The Russian Empire retained the priority of (Orthodox) religion over class until (!) the February Revolution in 1917. For example, in imperial Russia there was such a concept as the Pale of Settlement - a territory where Jews could live and were forbidden to move outside of it. At first glance, this looks like normal segregation, HOWEVER. Christianized Jews could live outside the Pale of Settlement, and especially rich and educated Jews had the right to do so. Yes, here it’s necessary to make disclaimers that there were such a minority and towards the end of the Russian Empire there was state discrimination of "privileged" Jews (for example, under tsar Alexander III). But we must take into account this "ambiguity" of social relations.

In the three empires, very different peoples lived side by side, who didn’t live segregated from each other, and built their identity not on "citizenship", but on the same religion or even on the area of residence. It can be said that Russians were an ethnic group in the Russian Empire, but this statement will tell you nothing about the relationship between Jews and Ukrainians, Poles and Romanians, Georgians and Armenians, etc. Moreover, empires had many mixed families, which significantly influenced attempts to build "nations" in these regions.

Serfdom existed for a long time in the Austro-Hungarian and especially in the Russian Empire. In fact, this is a form of slavery, but it extended to peasants, regardless of their ethnicity. In general, returning to the first point, the stratification here was very strict. In the Russian Empire, at the time the Bolsheviks came to power, 3/4 of the population were peasants and illiterate.

Oh yes, the Bolsheviks. The USSR in general confused everyone. At the beginning of the USSR, all nationalities were formally declared free (the Pale of Settlement and the priority of religion were abolished), but things went badly after the arrival of Stalin, under whose rule massive repressions were carried out against national minorities. At that time, many Germans lived in the USSR, who were a rather privileged community in the Russian Empire (recall that Catherine II was an ethnic German). But under Stalin, the Germans were among the first repressive and deported groups (largely due to the arrival of the Nazis in Germany and the invasion to the USSR). But by God, for reasoning about whether the USSR was an "empire" and what ethnic conflicts there were, 10 more posts are needed.

Finally, relations with the metropolises. Due to the redistribution of territories, the same territories with ethnic minorities belonged to different empires. The Balkans were part both of the Ottoman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Russia also wanted to annex them. As for today, the Czech Republic or Western Ukraine are unlikely to have any conflicts with Austria (but I’m not saying here about the entire Western European world). What can’t be said unequivocally about the Balkans and Turkey, and even more so about Russia and Belarus, Ukraine and Central Asia. In general, guys, it is possible to operate with intersectional theory only in the case of countries which 1) colonies were far from the metropolises; 2) capitalism developed early; 3) racial and ethnic minorities were severely segregated. And it hardly applies to countries that have been feudal for a long time, have gone through a massive revolution, a Soviet / nationalist dictatorship and suddenly become neoliberal.

#eastern europe#intersectionality#intersectional politics#colonialism#neocolonialism#post colonialism#history#us#western europe#russian empire#austro-hungary#ottoman#post soviet#capitalism#racism#nationalism#chauvinism

298 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jewish History Time!!!!!! 🕥

Hiiiiii

The Yiddish term for town, shtetl commonly refers to small market towns in pre–World War II Eastern Europe with a large Yiddish-speaking Jewish population. While there were in fact great variations among these towns, a shtetl connoted a type of Jewish settlement marked by a compact Jewish population distinguished from their mostly gentile peasant neighbors by religion, occupation, language, and culture. The shtetl was defined by interlocking networks of economic and social relationships: the interaction of Jews and peasants in the market, the coming together of Jews for essential communal and religious functions, and, in more recent times, the increasingly vital relationship between the shtetl and its emigrants abroad (organized in landsmanshaftn).

No shtetl stood alone. Each was part of a local and regional economic system that embraced other shtetls (Yid., shtetlekh) and provincial towns. Although the shtetl grew out of the private market towns of the Polish nobility in the old commonwealth, over time a shtetl became a common term for any town in Eastern Europe with a large Jewish population: towns not owned by noblemen in Poland, as well as towns in Ukraine, Hungary, Bessarabia, Bucovina, and the Subcarpathian region that attracted large-scale Jewish immigration during the course of the nineteenth century.

For all their diversity, these shtetls in Eastern Europe were indeed markedly different from previous kinds of Jewish Diaspora settlement in Babylonia, France, Spain, or Italy. In those other countries, Jews had lived scattered among the general population or, conversely, inhabited a specific section of town or a Jewish street. Rarely did they form a majority. This was not true of the shtetl, where Jews sometimes comprised 80 percent or more of the population. In many shtetls, Jews occupied most of the town, especially the streets grouped around the central marketplace. Poorer Jews would live further from the center and the frequently agrarian gentiles would often be concentrated on the peripheral streets, in order to be closer to the land that they cultivated.

This Jewish life in compact settlements had an enormous psychological impact on the development of East European Jewry—as did the language of the shtetl, Yiddish. Despite the incorporation of numerous Slavic words, the Yiddish speech of the shtetl was markedly different from the languages used by Jews’ mostly Slavic neighbors. While it would be a great mistake to see the shtetl as an entirely Jewish world, without gentiles, it is nonetheless true that Yiddish reinforced a profound sense of psychological and religious difference from non-Jews. Suffused with allusions to Jewish tradition and to religious texts, Yiddish developed a rich reservoir of idioms and sayings that reflected a vibrant folk culture inseparable from the Jewish religion.

The shtetl was also marked by occupational diversity. While elsewhere in the Diaspora Jews often were found in a small number of occupations, frequently determined by political restrictions, in the shtetl Jewish occupations ran the gamut from wealthy contractors and entrepreneurs, to shopkeepers, carpenters, shoemakers, tailors, teamsters, and water carriers. In some regions, Jewish farmers and villagers would be nearby. This striking occupational diversity contributed to the vitality of shtetl society and to its cultural development. It also led to class conflict and to often painful social divisions.

The experience of being a majority culture on the local level, sheer numbers, language, and occupational diversity all underscored the particular place of the shtetl as a form of Jewish Diaspora settlement.

Shtetls developed in the territories of the old Polish Commonwealth, where the nobility encouraged Jews to move onto estates in order to stimulate economic development. The eastward expansion of the commonwealth after the Union of Lublin in 1569 coincided with a growing market in Western and Central Europe for timber, grain, livestock and hides, amber, furs, and honey. Eager to develop their estates, the nobles needed competent managers and entrepreneurs—as well as regular markets and fairs. Jews were suitable instruments, especially because they could never become potential political rivals. thus developed the arenda (leasing) system, in which landlords leased key economic functions to a Jewish arendar (agent). Arenda usually included extensive subleasing, which further encouraged Jewish immigration to the landed estates. The manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages—largely in Jewish hands—was particularly important as it gave landlords an important hedge against falling grain prices in export markets.

Noble magnates established private market towns and sought to attract Jews to reside in them. Economic competition from Christians in older cities in western and central Poland, as well as Jew-hatred fanned by the church and by guilds, also stimulated Jewish migration to the shtetls in the less-developed eastern regions of the commonwealth (today’s eastern Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania). These new towns—all centered on a market square—reflected an emerging symbiosis of nobles, Jews, and the surrounding peasantry. One side of the market would often feature a Catholic church, built by the local landlord as a symbol of primacy and ownership, with a synagogue on the other side. The weekly market days brought together Jews and peasants and created a web of relationships that were both economic and personal. Usually the landlords granted charters that precluded market days and fairs on the Sabbath or on Jewish holidays. The shtetls—with their synagogues, schools, ritual baths, cemeteries, and inns—also served as a base for the numerous dorfsgeyer, that is, Jews who would fan out to the villages as carpenters, shoemakers, and agents. Many Jews who lived lonely lives in the countryside as taverners, innkeepers, or leaseholders could come to the shtetl for major holidays and important family occasions.

While some shtetls date from the sixteenth century, the peak of shtetl development occurred after the 1650s, following the ravages of gzeyres takh vetat (the Khmel’nyts’kyi uprising) and the Swedish invasion. The nobility made a concerted effort to recoup their economic standing by establishing new market towns. The development of these shtetls coincided with an enormous demographic increase of Polish Jewry. While the Polish–Lithuanian Jewish population stood at perhaps 30,000 in 1500, by 1765 it had expanded to about 750,000. A striking feature of this Jewish settlement was its marked dispersion. By the 1770s, more than half of Polish Jews lived in hundreds of private towns owned by the nobility: about one-third lived in villages. In many Polish cities, Christian guilds and the Catholic Church fought to curtail Jewish residence rights.