#that man has had covid so many times and was literally hit by a truck a couple months ago lol

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I was really surprised that David Roche just won Leadville, but then I looked at who else was running and it was mostly people I'd never heard of (though tbf I can name fewer than half as many male ultrarunners as female) and Ryan Montgomery was racing in the nb category. So now I am less surprised. But I'm still very surprised that he set a course record! If gambling on ultrarunning was a thing, a handful of people who placed what I'd call a very stupid bet would have just won a lot of money

#that man has had covid so many times and was literally hit by a truck a couple months ago lol#and he's never run a 100M and not because he's new to pro trailrunning (he's not)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

So this is a way Way overdue prompt that I got ages ago, but didn't have the time or muse-cooperation to write.

But I finally managed to write it!!

The prompt was given to me by the lovely @coffeeflavoredcookies : Chris all snuggled up to Buck as he tells him bedtime stories with Eddie standing at the door looking at them fondly.

This is fluff all the way, hope you like it ❣

-

The house was dimly lit when he got back, at this point Christopher would have usually already been in bed - post bedtime story.

But Buck has been staying the last few days with them after getting hurt on a call. Nothing too bad, mild concussion, some bruised ribs and a now relocated shoulder still stuck in a sling, so things aren't exactly on the normal side.

Buck had trouble understanding Eddie’s insistence that he stays with them, not wanting to be a burden (earning him an eye-roll from Eddie) and reminded him that he shouldn’t have to look after a grown-ass man while having an actual child of his own to take care of, (which resulted in Eddie calling Christopher and asking him, on speaker, what he thought of Buck staying with them for the next few days. Christopher cheered and Buck glared at Eddie, mouthing ‘traitor’ at him.)

The thing is, Buck seems to be unable to understand that whenever he’s hurt, physically or emotionally or just generally off-balance, Eddie is thrown to a loop right with him. Eddie would rather have him near and safe than wonder how he is, if he’s sleeping, eating - taking care of himself.

Back when his leg was crushed, so close to losing Shannon, Eddie was very close to saying to hell with Ali and then Maddie and just take him over to their place.

But Buck wasn't his to keep back then, and to be honest he's not his now, but Ali is long gone and Maddie is super pregnant, giving Eddie the best excuse to bundle him into his truck and take him home.

Sore and tired, Buck mostly slept, crashing on the couch, no matter how many times Eddie tried to get him to crash in the master bedroom, at least during the day.

Eddie got used to returning home from work to find Christopher sitting in the living room either doing his homework or playing or watching TV while Buck slept on the couch. Sometimes Christopher could be found nestled to Buck's side as they both nodded off watching some nature documentary.

Eddie has an album in his phone containing multiple pictures of his boys together. He will never get tired of snapping pictures of them, moments frozen in time, forever.

Eddie took his shoes off at the door and dropped his bag next to them. He showered at the station so he wouldn't waste time with Christopher in favor of washing the day off, he quickly rinsed his hands with soup, a habit left from crazed Covid days, then went in search of his boys.

The house was quiet, and the normally occupied couch was empty. Eddie made his way to Christopher’s room, already recognizing Buck’s low gravel voice, reading what sounded like “I Had Trouble in Getting to Solla Sollew”, Buck got Christopher the book a couple of weeks prior to his injury.

He told Christopher that Maddie used to read it to him when he was younger. They read it so many times, that both of them knew it by heart at one point. This is the first time he got to read it to him, if Eddie is not mistaken.

Eddie quietly made his way to the bedroom and stopped to lean on the door frame, taking in the sight in front of him. Christopher was lying in bed snuggled up against Buck’s uninjured side, he was already fast asleep, but Buck kept reading quietly leaning against the headboard.

“Then I dreamed I was sleeping on billowy billows

Of soft silk and satin marshmallow-stuffed pillows.

I dreamed I was sleeping in Solla Sollew,

On the banks of the beautiful River Wah-Hoo,

Where they never have troubles. At least very few.”

Eddie was so caught up in the cute picture presented before him, that he hadn't noticed Buck’s stopped reading and turned welcoming eyes on him, “Hey Eds.” he greeted with a soft smile.

“Hey Buck.” Eddie greeted back with a smile, slowly making his way inside, gently detangling Christopher from Buck to lay him properly on the pillow, and freeing Buck to rise and stretch carefully.

The blonde nodded gratefully at his friend, with a last look down at Christopher, he smiled and left Eddie to tuck Christopher in safely and say goodnight. Eddie’s eyes followed Buck as he left the room, making sure he’s steady on his feet and also because he couldn’t really look away.

When Buck was out and on his way to the living room Eddie turned around, pressed a kiss to Christopher’s forehead, turned on the nightlight and left the room, closing the door behind him.

Eddie noted Buck’s absence in the living room and followed the sounds to the kitchen, standing at the door, he inquired “Should you be without your sling?”

"Honestly, no." Buck admitted with a sheepish smile, "But my neck is killing me and doing everything one handed is driving me crazy." He complained, handing Eddie a beer and leaned back against the counter while drinking the Gatorade he started earlier.

“At least you’re not drinking beer.” Eddie rolled his eyes. Buck scoffed “I wanted to, Christopher said no.” he smiled at Eddie’s laugh.

“Sounds about right.” Eddie nodded. “Did Carla make dinner?”

Buck shook his head, “No, she had to leave early, I told her I got this.”

“Tell me you ordered dinner.” Eddie demanded.

“There are waffles and Eggs in the microwave for you.” Was Buck’s sole reply.

“You’re supposed to be resting.” Eddie protested with an exasperated look.

“I have been resting, Edmundo!” Buck rolled his eyes, “And I’ll go back to resting now that your kid is fed, ready for his day tomorrow and has fallen asleep in his own bed for a change.” Buck retorted and was about to move past Eddie when the latter grabbed the wrist of his good arm and turned him around, bringing him flush against Eddie’s body.

Faces a hairbreadth away from each other, Buck met Eddie’s eyes with a curious look, “You gonna teach me to dance Eds?”

“I thought you already knew how to dance, Ev.” Eddie replied with a soft smirk, voice barely beyond a murmur.

“Hmm.. So wha..” Buck didn’t finish the rest of the sentence because Eddie’s lips were on his, and the finally in his head was so loud, it took him a second to sigh contentedly and kiss back.

Eddie’s hands strayed to Buck’s waist bringing him even closer as he maneuvered them carefully out of the kitchen and into the living room, stopping when the back of his knees hit the couch, his palms framing Buck’s face with one last kiss before breaking apart, chuckling at Buck’s protesting whine.

“What was that for?” Buck asked as Eddie rearranged the pillows on the couch before situating himself with his back to one side and reached to gently pull Buck down so he could lie back on Eddie’s broad chest, framed between his stretched forward legs.

Buck went pretty easily, not even questioning Eddie’s tactile display, it’s been known to happen, it just didn’t usually start with a kiss. Buck turned his head to one side looking up to meet Eddie’s eyes, Eddie’s brown eyes were soft and fond, Buck couldn’t help but smile back at him when Eddie offered him a grin.

Before Buck could open his mouth and ask again what’s going on, Eddie wrapped a long arm across Buck’s broad chest and threaded the fingers of his other hand with Buck’s, resting them on Buck’s stomach. “I’m done overlooking the pink elephant in the room.”

“Is that a veiled reference of your dislike for that shirt?” Buck quipped, squeezing Eddie’s hand reassuringly.

“That too.” Eddie played along, he really did hate that shirt, but Buck kept insisting it defined his muscles, which it did, but literally most of his size-down shirts already did that. “But also because coming home to the sight of you and Christopher every night, was pretty much wearing me down.”

Buck’s face broke into a smile that was a complicated mix of self-consciousness and contentedness, which Eddie found adorable, “So what broke you tonight?” Buck asked, bringing Eddie out of his reverie “I mean, it was a pretty standard evening in the Diaz household.” He pointed out with a teasing smile.

“You made sure Christopher fell asleep in his own bed.” Eddie said, chin resting on the top of Buck’s head gently.

“Well, It felt like some normalcy was needed.” Buck replied, his voice soft. “Both of us injured and out of commission in the short span of five months seemed to be taking a toll.”

“And the fact that you’re the one who managed to find a way to stir him back into the right direction is what broke me, I guess.” Eddie admired quietly, “That, and the cute picture you two presented when I got into the room.” He smiled, pressing a kiss to Buck’s temple who was blushing endearingly.

The moment was broken by an exhausted yawn from Buck, “Sorry, been a long day, and you’re too comfortable.” he accused jokingly.

“Bed?” Eddie suggested.

“You sure?” Buck asked, it’s not like they haven’t shared a bed before but this was semi-new territory. “I've already bonded with the couch, I’m good sleeping out here until we figure this out.”

Eddie rolled his eyes, “Bed.” he determined with a growl.

Buck chuckled amusedly as he rose carefully to his feet along with Eddie, “Caveman.” he teased.

Eddie shook his head with a laugh, “brat.” he retorted, pecking Buck’s lips before taking his hand and leading him to the master-bedroom.

***

That's it :) I hope you like it!! 💖💖

ps. That book Buck is reading to Christopher is a story my dad used to read to me and my sisters when we were youngers, we all know it by heart, to this very day. 🤗💕

#buddie prompt#buddie fic#evan buckley#eddie diaz#christoper diaz#is a national treasure#short fluff#buddie#9 1 1 on fox#buddie fandom#buddie fanfiction#buck x eddie#eddie x buck#eddie and buck#9-1-1

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amphibia: Night Drivers/Return to Wartwood Review “Many Happy Returns”

Hello you happy people. And Amphibia is back and that means my reviews are back! As for why this reviews a bit late despite it leaking, I wanted to wait for today, and long story short both focused on finishing a review that WASN’T time senstive, instead of finishing it Sunday, and overestimated how much time i’d have to do two reviews on a day that included my first covid shot, grocery shopping, helping mom clean the car, and my friend coming over to watch Judas and the Black Messiah. Excellent film by hte way, as was the Sound of Metal which we watched after. Point is I done goofed and I will try to at the very least actually get the reviews of the episodes out on the same day they come out.

But slip up or not i’m happy to be back in the saddle, and back to Wartwood. I’m pumped for the heavier second half, with more secrets to uncover, some zelda style temple action, and some heavy drama with just a whiff of keith david, as well as to see the supporting cast from Wartwood again after far too long. So how’d the mid-season premire pair fair? Join me under the cut to find out.

Night Drivers: I was really excited by the Road Trip idea when first announced for season 2. A chance to expand the world and get the plantars out of their comfort zone was an amazing concept and it did lead to some really great stories and interesting locales.. mixed with episodes that had interesting locations but no interesting plot or character stuff. It was a mixed bag, and disappointing after close to a year’s wait to continue the plot that it really didn’t outside of “Toadcatcher”. Anne never really dealt with her trauma and the show never dealt with hop pop’s poularity or anything else. Again there were GOOD episodes and ideas but it felt like the show stalled for a good chunk of the season till we got to Netwopia which while still having tons of slice of life stuff felt a lot fresher with it, and had a lot more fun playing with stock plots and gave us a fresh new setting to dig into.

So I was a bit hesitant to go back to the road for an episode.. even if it was just one episode. Thankfully I was very wrong there as Night Drivers was a pretty good episode and would fit well among the best of the road trip arc like “Truck Stop Polly” “Fort in the Road” “Anne Hunter” “Toadcatcher” and “Wax Museum”.

The plot is straightforward: Sprig and Polly are excited that their almost home to wartwood and if Anne and Hop Pop drive all night they’ll be there by morning. Polly will get pillbug pancakes and Sprig will see Ivy again. This is part of a long tradtion of “skiping over the journey home because we’re tired and we wanna go home” in fiction. Jokes aside it’s a resonable device used to prevent ending fatigue and in this case to free up episodes for the second half. We already saw the journey once, we usually don’t need to see it again. To Amphibia’s credit they have valid reasons for it: The journey is LITERALLY sped up, as Hop Pop and Anne have been driving for 20 hours straight.. and their on a timer. As was established last time.. well the last time that wasn’t a spooky halloween episode, The Plantars have to get back for the harvest and really don’t have time to sightsee, while they all have to be there for whenever Marcy comes back to take Anne to the first temple. They’ve also traveled these roads before so while their going a whole other directoin, they know what perils to avoid.

But as anyone whose taken a long cartrip can tell you, you can’t shotgun it forever and the two eventually tap out with Hop Pop telling Sprig and Polly not to night drive as it’s dangerous and blah blah blah standard parental warning that will be swiftly ignored. So once Hop Pop and Anne are conked out they swiftly ignore it after we get their dreams.. which are the best gags of the episode: Hop Pop has a dream with weird, really cool looking monsters that represent his faults, only for it to turn Lucid and him to start flying and take his shirt off and whip it around Muscle Man style.

While Anne’s is about a yogurt world where there’s only one flavor... BLACK LICORICE. Yeah it quickly turns from Shopkins to the Lich From Adventure Time really fucking quick.

So while Anne has a nightmare and Hop Pop becomes unto a god, Sprig and Polly drive all night, repreadtly running into a creepy hitchiker and realizing it is as dangerous as they said with bolders, even worse creatures than usual because of course theye’d be a lot of nasty things lurk in the dark why wouldn’t they on froggy death world, a nightmarish fog and nearly dying on said foggy road they took to evade the hitchiker. Naturally the scary hook handed hitchiker.. is a friendly one, simply trying to help them and saving them from going over a cliff. They do make it three miles from Wartwood and Hop Pop wakes up angry to find they disobeyed him.. but Anne gets him to back off as they clearly learned their lesson from the sleep deprviation and nearly dying, and our heroes head for home.

Night Drivers isn’t an exceptional episode, but it is decent and still does belong with the other good road trip episodes, with some good dream sequences and a nice dynamic between Sprig and Polly. It was nice to have an episode with the two that was good unlike Quarallers Pass which made me want to run full speed into my nearest wall until I was given the sweet gift of unconciousness. While the Hook Handed man thing was a bit obvious it lead to some great gags. It’s a nice breather after the tearjerking mid-season finale and while we’ve obviously had months and a haloween episode between that, the creators rightfully realized a lot of people will be binging the series in the future. The issue I had with the first quarter of the season was it was ALL break and only a little plot progression. Here we’ve had a lot of plot progression in the last episode chronlogically, and are going to have a lot in the coming episodes with ‘After the Rain” coming next week. It’s nice to take a break and see the forest for the hook handed ghosts.

Return to Wartwood: I was excited and terrified of this one. I was excited because I missed the supporting cast from season one, mostly Ivy and Maddie, and was delighted to see them again in full. But I was also worried the show might pull out a melancholy breakup plot and having gotten attached to Ivy/Sprig and Hop Pop/Sylvia I was worried. And I was delightfully wrong as instead it’s another breather episode and an utterly fantastic one after the simply decent one above.

Our heroes return, without being drawn by rob liefield or replaced by the Squadron Supreme first, and are happily greeted by the town. Aformentoined fears died a happy death as Sylvia squeezes Hop Pop and as for Sprig, Ivy unsuprisingly ambushes him. Everyone’s back and the Mayor, who I also badly missed is back using Toadie as a gong to get everyone back to buisness, with Swampy inviting them for a big dinner at his diner that night to celebrate and welcome them back.. and to give out their gifts.

Sprig and Anne are equally confused while Polly and Hop Pop are sweating bullets. Turns out when they got the Fwagon they agreed to get a bunch of stuff for the town and forgot and now everyone’s on the hook for it and want to lie their butts off to solve it. In a nice show of character development, Anne has learned that the lying never solves anything “I think we’ve learned that lesson by now”. After SO many plots of the characters lying and it going terribly, it’s nice to have someone speak up. Sprig also wants to lie but only becuase he’s deeply afraid Ivy will break up with him as she wanted a Red Sun shell to go with the blue moon shell she gave him. Awwww. And oh crap.

So our heroes head home to plan and kick Chuck out (“I grew tulips”). So they do the natural thing... and decide to summon an edltich beast from the necronomicon... which of course Maddie gave Sprig as a present (”Aww that’s nice”. Agreed Polly, agreed.). I also can’t help but love the line “We’re all cull with practicing the dark arts to solve our problem right?” So our heroes get the proper summoning horn, thing to go with the horn and some candles.. i’ts not part of the ritual but Anne says it helps with ambience and it’s right.

So our heroes summon the Chikalisk, an edltich god that’s naturally basalisk in all but name, which dosen’t attack unless attacked and goes after gold. So they fake some golden presents, and the beast attacks at the party.. but the town naturally fights back, and our heroes are forced to help fight the monster as it stonifies people. So we get a truly glorious battle sequences as the whole town shows off how badass they are, with Maddie curing people, Sylvia showing she can keep up with Hop Pop and Ivy showing her already established badass bonafieds. It’s just awesome. Also the Mayor uses Toadie as a shield not realizing he’s turned to stone which can only remind me of this.

Once the townsfolk are freed they get into Chickalisk formation (”We have a formation for that?” “We have a formation for everything!”) And it’s offended enough to just nope out. The townsfolk are depressed though the presents got destroyed and Anne glares the family into coming clean. And while the mayor seems mad at first... he just laughs with everyone taking it in stride: It was boring without them getting into trouble and learning lessons every week, and they missed them. Ivy likewise dosen’t care about a gift she just missed her boyfriend.. and asks Sprig to take her on a proper date and smooches him on the cheek leaving both him and Anne catatonic, with Polly dragging Anne away and sprig just falling over before Maddie hits him with the potion. It dosen’t work that way, end episode.

Return To Wartwood was a standout episode, with tons of great jokes, pacing and a nice plot that showed growth in anne. While Night Drivers was decent, this was the show at it’s : Sweet, deranged and adventurous all in one episode. While Night Drivers was a good appitizer this was one hell of an entree. Or an appetizer sampler which I often use as an entree. Great episode and a nice high note to start on.

Next Time: We get an Ivy focused episode!

And Hop Pop is finally forced to own up to his lies!

As the twin kermits sooth you if you liked this review, follow me for more, check the amphibia tag for more reviews from this season and join me on patreon. If I get another patreon, i’ll add reviewing season 1 to my 25 dollar stretch goal so look out for that and my next one at 20 dollars, only 5 dollars away, nets a monthly review of a darkwing duck episode. Check it out and i’ll see you at the next rainbow.

#amphibia#night drivers#return to wartwood#anne boonchuy#sprig plantar#hopidiah plantar#polly plantar#ivy sundew#maddie flour#sylvia sundew#mayor toadstool#disney channel#disney#animation#amphibia spoilers

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

I do not want this

Like the NIN song... I do not want this. I can’t keep doing this. Being this.

Ever have an epiphany hit you so hard that you literally just say, “Fuck me!” out loud? That’s what’s happening right now.

Doing what? Being what? Well... doing this thing where I feed the fantasy. Being the fantasy. I do not want this.

My most recent conversation with Jersey has been on my mind since I opened my eyes and started crying.

Part 1: COVID. He’s a firefighter in New Jersey, right across from NYC. In previous conversations he’d told me about the uptick in calls because people who had never cooked were setting kitchen fires. I giggled, I admit it.

But he also said that people were “dying left and right” out there. Last night he told me about a friend of his who lost both of her parents to COVID. She couldn’t be with them, and they put their bodies into refrigerated trucks. Utterly heartbreaking.

He tries not to talk politics but he said that our leadership should be ashamed of themselves. (I totally agree) And then he started talking about moving to Nova Scotia and living together in a tiny house. Another fantasy. But...

Part 2: He is married. When we met in MD he and his wife were living apart and apparently had been on and off for years. But when I tried to ask what their dynamic was, he sidestepped things. Bottom line, as far as she knows they are monogamous and closed.

Even then there was talk of leaving once his kid was old enough. His kid is now 20 years old. Which set me spinning down another track...

He has been married for at least 2 decades and he’s sitting there on fire duty talking to me about running away from his life and starting over with me. That is my worst nightmare.

Can you imagine spending 20+ years married to someone only to find out that they were talking to another woman (or more than one, who knows?) on and off for (at least) FIVE YEARS?!? That is such a deep level of betrayal and hurt that it makes my heart ache to know that I’ve been that woman.

I’d justified it in my own mind... that’s between him and her, he’s the one breaking agreements. There has to be more to the story. It’s just talk anyway and I don’t think he would actually do it.

And then he said, “Life change is important after all this.” So, would he actually do it now?

I’ve done this too many times before. I did the unethical non-monogamy from the beginning. Byron and I lost our virginity to each other, then he started dating my best friend... but kept sleeping with me. And when I was sexually assaulted by another friend’s boyfriend, nobody believed me because if I would sleep with one friend’s boyfriend of course I’d sleep with another, right?!?

I was 16 years old in a relationship with a 31 year old who was literally 3 days out of San Quentin (yes, prison) when we met. His girlfriend was my mother’s best friend and when she threatened to kick my ass, my mother said, “Well, if you feel the need to do it, go ahead!”

I told the boyfriend before MM that I wasn’t ready for monogamy and commitment but when he realized that I meant it and I was hooking up with a couple from work he freaked out and ended things. I was so proud of myself for being honest. For not being that person anymore. For owning who I was and what I wanted. I had finally found a way to be honest and real and be exactly who I was without hurting anyone. That was 8 years ago.

MM and I actually had conversations about Jersey when this all started. MM was, for lack of a better word, disappointed in me for knowingly getting involved with a cheater.

Jersey isn’t the only one lately. Another of my first partners reached out to me not long ago. He’s been in a relationship with a woman for a decade. When we chatted, he went on about how I was the one who “made him a man” and that he wanted to come see me. I brought up the girlfriend and all he said was that he’s 42 not 14 anymore and that it would be a ‘business trip.’

I do not want this. I’m just a fantasy to them... to more than just those two if I’m being honest. I’ve had several others tell me that I was ‘the one who got away’ and their ‘first love’ and admitted to masturbating to pictures of me decades after we were together.

It sounds like it should be flattering. And I have to admit that a part of me still loves the attention and the idea that I’m the measuring stick that these men have used over the years with new partners. I’m that amazing.

But today it hit me like a ton of bricks. I do not want this. I don’t want to be somebody’s fantasy. I want to be somebody’s partner. I want to be a whole person in their eyes much in the way I’ve fought for so long to become a whole person in my own eyes.

And yes, I love taking sexy pictures and sharing them. I love giving head. I love being tied up and beaten. But I also love deep conversations, home-cooked meals and everyday life with a partner. I shouldn’t have to choose between the two.

I can be lovable and fuckable. I AM LOVABLE AND FUCKABLE... and there’s nothing wrong with being both, dammit!

I do not want this... This thing I’ve allowed myself to become in the eyes of these men.

I think Tor is the closest I’ve gotten to being a whole person with. He’s seen my sexy pics, but we’ve also talked about mental health and relationships and grief and loss... he is literally my supervisor and he sees the work I do and how good I really am at my job. Seeing my ass... seeing me steamed up and soapy in the shower, hearing stories about my sex life... none of that changes the other things I am with him. That is so fucking empowering.

Is this the lesson I needed to learn here? Is this one of the big clue-by-fours I’ve been artfully dodging that needed to be demolished? Holy shit.

I really miss drinking right now.

#covidquarantine#content warning#the other woman#ethical non monogamy#Nine Inch Nails#i do not want this#jersey#just a fantasy#empowered

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

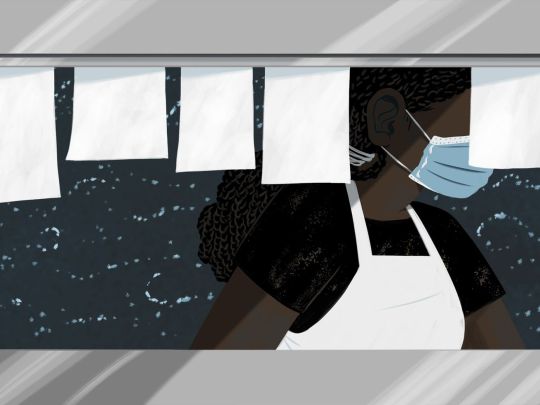

It’s Time for the Hospitality Industry to Listen to Black Women

History shows us that the novel coronavirus will impact black women restaurateurs, and their businesses, much harder

Before the pandemic, our nation was in the early stages of battling an epidemic that plagued our beloved hospitality industry: the biased structural policies, born out of our country’s legacy of racism that guaranteed that black Americans would continuously work at a deficit. Painfully honest conversations — dissecting the ways in which decades of systematic racial and gender inequality festered in the industry — had finally begun to gain traction in on- and offline spaces. But, collectively, we’d barely broken through the dysfunctional infrastructure that allowed certain groups to fail harder and faster when COVID-19 struck.

Chef Deborah VanTrece was ringing the alarm prior to the coronavirus pandemic. She regularly brought discussions of industry inequality to the table through her dinner-and-conversation series that centers black women in hospitality. “It was something that we had just started talking about at Cast Iron Chronicles, and a lot of other chefs were talking about it,” says VanTrece, owner of Twisted Soul Cookhouse & Pours in Atlanta. “But the conversation wasn’t finished. It still isn’t.”

“As much as we’ve accomplished, I still feel isolated and that I am by myself. I don’t think any of us should feel that way. We should be checking on each other. It’s like [coronavirus] happened and every man for himself,” VanTrece says. “And when I think about it, we were pretty much like that in the first place; that’s why it’s so easy for it to continue now.” Isolation has become a theme in our shared new normal of stay-at-home orders, but what VanTrece is describing is a sentiment long echoed by black women in the industry. Yet seeing the divide continue during these times is heartbreaking for VanTrece. “If we were ever needing to be one, it’s now. We need to be one.”

Black and brown voices are largely excluded from overarching conversations that will define the future of our industry

As we grapple with lives lost and the magnitude of devastation caused by novel coronavirus, accountability and transparency seem to be overshadowed by crisis-led pivots while we brace ourselves for what’s to come. And yet again, black and brown voices are largely excluded from policymaking and overarching conversations that will define the future of our industry. In the face of this pandemic, some may say the pursuit of equality has been railroaded, maybe even understandably so. Others see the crisis as a hopeful confirmation that institutional change is inevitable. Because if not now, when?

In order to know where we are going, we have to understand where we’ve been. Black restaurant owners, black women especially, are in a more precarious position from the get-go. According to the latest figures, from 2017, black women were paid 61 cents for every dollar paid to their white male counterparts, making wealth generation much more difficult. And while one in six restaurant workers live below the poverty line, African Americans are paid the least. Access to capital has been a steady barrier of entry, especially for black women. Black- and brown-owned businesses are three times as likely to be denied loans, and those that are approved often receive lower loan amounts and pay higher interest rates. For a population more likely to rent than other demographics, offering up real estate as collateral for traditional loans isn’t an option. And even for those who own a home, the lasting effects of redlining, predatory and discriminatory lending practices, and low home valuations are palpable.

In other words, the wealth gap, combined with a lack of access to traditional loans and investors for start-up capital, puts black women at a disadvantage before they even open the doors of their restaurants. “A lot of us have had to build our businesses from scratch, and that may be through personal savings and loans, through family members, credit cards, or we have refinanced our homes,” says chef Evelyn Shelton, owner of Evelyn’s Food Love, a cafe serving comfort food in Chicago’s Washington Park neighborhood. “We are in uniquely different positions when we start, which makes where we are now even more difficult.”

In the East Bay, chef Fernay McPherson, owner of Minnie Bell’s Soul Movement, a food truck turned brick-and-mortar now located in the Emeryville Public Market food hall, is offering a limited carryout menu in an effort to keep her staff afloat, noting that some are single parents. “I was a single mother, so it’s a lot to take in when you’re thinking, ‘How am I going to feed my child? How am I going to make rent?’” During the Great Recession, McPherson was laid off and had to short-sell her home. She started Minnie Bell’s in 2009, as a catering company, while also working full-time as a transit operator in San Francisco. “It was hard being a mom, driving a bus, and trying to operate a business. It was a lot on me. And my decision was me. To work for me.”

Working multiple jobs is a necessary for many entrepreneurs whose bootstraps are shorter to begin with, says Lauren Amos, director of small-business development at Build Bronzeville, a Chicago incubator that advocates for South Side business owners. “We’re talking about people literally working a full-time job, supporting themselves and their family while still pursuing this dream of opening a business,” she says. “And they’re doing it out of their own physical pocket.”

McPherson, a San Francisco Chronicle 2017 Rising Star Chef, says it was tough getting a job in the restaurant industry after culinary school. “I came into a white, male-dominated field and I was a young, black woman that wasn’t given a chance. My first opportunity was from another black woman and I worked in her restaurant.” Access to a solid professional network, including mentors, is absolutely as vital as access to capital — social capital is another part of the ecosystem, and can be a bridge to resources necessary for growth. But without the right connections, strong networks may be hard to plug into, and exclusion from these networks can have a stifling effect on one’s career.

McPherson has steadily established a solid network over the years. Now, she’s envisioning what her post-pandemic future will look like, including a possible alliance with other women chef-owners. “We’re talking about collectively developing our own restaurant group, in a sense, where we can build a fund for each member, build benefits for our employees, and build career opportunities,” she says.

In coming weeks and months, people in many industries will be taking stock of what could have been done better. But for now, McPherson’s most pressing need is capital to be able to restart.

Studies show that African-American communities were hit hardest by the Great Recession. According to the Social Science Research Council, black households lost 40 percent of wealth during the recession and have not recovered, but white households did. Unemployment caused by the recession disproportionately affected black women, a double-edged sword for many of whom worked lower-wage jobs that relied on tips. The costs of these disparities are far reaching. Six years after a defunct grocery chain shut its doors, creating a food desert in the Chicago South Side neighborhood of South Shore, a new grocery store finally opened — just last December — a few months before the pandemic.

Black communities are undervalued. “Mom-and-pop,” a term of endearment that acknowledges the fortitude and nobility in owning a small business, is rarely applied to black-owned businesses. Racial discrimination and biased perceptions of black-owned restaurants in black communities costs them billions of dollars in lost revenue. Disinvestment in these communities sets the landscape for quick-service restaurant chains to flourish, as professor Marcia Chatelain eloquently lays out in Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America, all of which presents added pressure for the competing independent restaurant owners, whose margins are already miniscule.

“We’re truly hanging on by a thin thread,” Shelton says. She encourages local legislators to call on neighborhood restaurants and caterers to feed people who are food insecure, as well as individuals at the 3,000-patient field hospital erected at McCormick Place, the Chicago convention center that already houses Shelton’s now-closed second location. Meanwhile, Shelton regularly delivers meals to the ER staff at a neighboring hospital, paid for out of her own pocket.

Disparities in restaurants are emblematic of the nation. Indicators show that African-American communities are hit the hardest by COVID-19. ProPublica sums it up: “Environmental, economic, and political factors have compounded for generations, putting black people at higher risk of chronic conditions that leave lungs weak and immune systems vulnerable: asthma, heart disease, hypertension and diabetes.” And a lack of access to quality health care means the novel coronavirus has the potential to disproportionately decimate black communities, and the independent restaurants within them, if adequate support is not provided.

History shows us that the most vulnerable are left behind, and a similar pattern will likely occur post-pandemic. “The difference is the ability to be able to bounce back,” says Build Bronzeville’s Amos. When the pandemic hit, her organization swiftly aligned with other South Side organizations to urgently deliver vital information to small-business owners through grassroots efforts. “This is not a drill. Now is the time for all of us who want to be resource providers and boil it down for people,” Amos says.

Recognizing that communities with the most funding will have the greatest chance for survival, Amos leverages her relationships and personally calls and sends texts to restaurateurs conveying time-sensitive information like grant deadlines — she has become a lifeline for vulnerable small-business owners during this critical time. Amos has also extended assistance to Dining at a Distance, a delivery and takeout directory, after noticing its site had robust coverage of hot spots in the city, but little representation of South Side restaurants. Amos became a link and added a slew of South Side restaurants to the platform, noting that consumer-facing exposure is urgently needed. “A grim reality is that we have to capture these dining-out dollars now,” she says, “because there will come a point where people will stop ordering out because it just won’t be fiscally responsible for them to do so.”

As we envision a new path for the hospitality industry, black women must be central to the conversation: Their journeys hold wisdom that is widely absent from in-depth studies and data. And there’s no better industry to lead change than one known for breaking bread.

To support her community and staff, VanTrece has launched a pay-what-you-can menu at Twisted Soul, thinking of the model as a fundraiser of sorts. “This is a whole new pricing structure. You’re not pricing to pay the bills and pay the rent,” says VanTrece, whose landlord told her she wouldn’t have to pay a late fee on her rent, which is $10,000 a month. In addition to cashing in her credit card points for gift cards for her staff, she’s turned her restaurant into a hub where they can quickly grab necessities like a hot meal and toilet paper. It’s a service most of her team participates in. “But then I have some that are just scared,” she says. “They don’t want to come and I can’t blame them.”

On a recent Friday, a carryout fish fry was on VanTrece’s menu, a reminder of the ones she grew up going to during better days. She looks to the past for guidance often. “At Cast Iron, we always talked about the strength and the tenacity of our forefathers, and I’m calling upon that strength now to keep me putting one foot in front of the other, because there are times I just want to roll over,” she says. “And I can’t do that. I fought to get this far and I’m going to continue to fight through this.”

Angela Burke is a food writer and the creator of Black Food & Beverage, a site that amplifies the voices of black food and beverage professionals. Shannon Wright is an illustrator and cartoonist based out of Richmond, Virginia.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/3bi4741 https://ift.tt/3bj5Juk

History shows us that the novel coronavirus will impact black women restaurateurs, and their businesses, much harder

Before the pandemic, our nation was in the early stages of battling an epidemic that plagued our beloved hospitality industry: the biased structural policies, born out of our country’s legacy of racism that guaranteed that black Americans would continuously work at a deficit. Painfully honest conversations — dissecting the ways in which decades of systematic racial and gender inequality festered in the industry — had finally begun to gain traction in on- and offline spaces. But, collectively, we’d barely broken through the dysfunctional infrastructure that allowed certain groups to fail harder and faster when COVID-19 struck.

Chef Deborah VanTrece was ringing the alarm prior to the coronavirus pandemic. She regularly brought discussions of industry inequality to the table through her dinner-and-conversation series that centers black women in hospitality. “It was something that we had just started talking about at Cast Iron Chronicles, and a lot of other chefs were talking about it,” says VanTrece, owner of Twisted Soul Cookhouse & Pours in Atlanta. “But the conversation wasn’t finished. It still isn’t.”

“As much as we’ve accomplished, I still feel isolated and that I am by myself. I don’t think any of us should feel that way. We should be checking on each other. It’s like [coronavirus] happened and every man for himself,” VanTrece says. “And when I think about it, we were pretty much like that in the first place; that’s why it’s so easy for it to continue now.” Isolation has become a theme in our shared new normal of stay-at-home orders, but what VanTrece is describing is a sentiment long echoed by black women in the industry. Yet seeing the divide continue during these times is heartbreaking for VanTrece. “If we were ever needing to be one, it’s now. We need to be one.”

Black and brown voices are largely excluded from overarching conversations that will define the future of our industry

As we grapple with lives lost and the magnitude of devastation caused by novel coronavirus, accountability and transparency seem to be overshadowed by crisis-led pivots while we brace ourselves for what’s to come. And yet again, black and brown voices are largely excluded from policymaking and overarching conversations that will define the future of our industry. In the face of this pandemic, some may say the pursuit of equality has been railroaded, maybe even understandably so. Others see the crisis as a hopeful confirmation that institutional change is inevitable. Because if not now, when?

In order to know where we are going, we have to understand where we’ve been. Black restaurant owners, black women especially, are in a more precarious position from the get-go. According to the latest figures, from 2017, black women were paid 61 cents for every dollar paid to their white male counterparts, making wealth generation much more difficult. And while one in six restaurant workers live below the poverty line, African Americans are paid the least. Access to capital has been a steady barrier of entry, especially for black women. Black- and brown-owned businesses are three times as likely to be denied loans, and those that are approved often receive lower loan amounts and pay higher interest rates. For a population more likely to rent than other demographics, offering up real estate as collateral for traditional loans isn’t an option. And even for those who own a home, the lasting effects of redlining, predatory and discriminatory lending practices, and low home valuations are palpable.

In other words, the wealth gap, combined with a lack of access to traditional loans and investors for start-up capital, puts black women at a disadvantage before they even open the doors of their restaurants. “A lot of us have had to build our businesses from scratch, and that may be through personal savings and loans, through family members, credit cards, or we have refinanced our homes,” says chef Evelyn Shelton, owner of Evelyn’s Food Love, a cafe serving comfort food in Chicago’s Washington Park neighborhood. “We are in uniquely different positions when we start, which makes where we are now even more difficult.”

In the East Bay, chef Fernay McPherson, owner of Minnie Bell’s Soul Movement, a food truck turned brick-and-mortar now located in the Emeryville Public Market food hall, is offering a limited carryout menu in an effort to keep her staff afloat, noting that some are single parents. “I was a single mother, so it’s a lot to take in when you’re thinking, ‘How am I going to feed my child? How am I going to make rent?’” During the Great Recession, McPherson was laid off and had to short-sell her home. She started Minnie Bell’s in 2009, as a catering company, while also working full-time as a transit operator in San Francisco. “It was hard being a mom, driving a bus, and trying to operate a business. It was a lot on me. And my decision was me. To work for me.”

Working multiple jobs is a necessary for many entrepreneurs whose bootstraps are shorter to begin with, says Lauren Amos, director of small-business development at Build Bronzeville, a Chicago incubator that advocates for South Side business owners. “We’re talking about people literally working a full-time job, supporting themselves and their family while still pursuing this dream of opening a business,” she says. “And they’re doing it out of their own physical pocket.”

McPherson, a San Francisco Chronicle 2017 Rising Star Chef, says it was tough getting a job in the restaurant industry after culinary school. “I came into a white, male-dominated field and I was a young, black woman that wasn’t given a chance. My first opportunity was from another black woman and I worked in her restaurant.” Access to a solid professional network, including mentors, is absolutely as vital as access to capital — social capital is another part of the ecosystem, and can be a bridge to resources necessary for growth. But without the right connections, strong networks may be hard to plug into, and exclusion from these networks can have a stifling effect on one’s career.

McPherson has steadily established a solid network over the years. Now, she’s envisioning what her post-pandemic future will look like, including a possible alliance with other women chef-owners. “We’re talking about collectively developing our own restaurant group, in a sense, where we can build a fund for each member, build benefits for our employees, and build career opportunities,” she says.

In coming weeks and months, people in many industries will be taking stock of what could have been done better. But for now, McPherson’s most pressing need is capital to be able to restart.

Studies show that African-American communities were hit hardest by the Great Recession. According to the Social Science Research Council, black households lost 40 percent of wealth during the recession and have not recovered, but white households did. Unemployment caused by the recession disproportionately affected black women, a double-edged sword for many of whom worked lower-wage jobs that relied on tips. The costs of these disparities are far reaching. Six years after a defunct grocery chain shut its doors, creating a food desert in the Chicago South Side neighborhood of South Shore, a new grocery store finally opened — just last December — a few months before the pandemic.

Black communities are undervalued. “Mom-and-pop,” a term of endearment that acknowledges the fortitude and nobility in owning a small business, is rarely applied to black-owned businesses. Racial discrimination and biased perceptions of black-owned restaurants in black communities costs them billions of dollars in lost revenue. Disinvestment in these communities sets the landscape for quick-service restaurant chains to flourish, as professor Marcia Chatelain eloquently lays out in Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America, all of which presents added pressure for the competing independent restaurant owners, whose margins are already miniscule.

“We’re truly hanging on by a thin thread,” Shelton says. She encourages local legislators to call on neighborhood restaurants and caterers to feed people who are food insecure, as well as individuals at the 3,000-patient field hospital erected at McCormick Place, the Chicago convention center that already houses Shelton’s now-closed second location. Meanwhile, Shelton regularly delivers meals to the ER staff at a neighboring hospital, paid for out of her own pocket.

Disparities in restaurants are emblematic of the nation. Indicators show that African-American communities are hit the hardest by COVID-19. ProPublica sums it up: “Environmental, economic, and political factors have compounded for generations, putting black people at higher risk of chronic conditions that leave lungs weak and immune systems vulnerable: asthma, heart disease, hypertension and diabetes.” And a lack of access to quality health care means the novel coronavirus has the potential to disproportionately decimate black communities, and the independent restaurants within them, if adequate support is not provided.

History shows us that the most vulnerable are left behind, and a similar pattern will likely occur post-pandemic. “The difference is the ability to be able to bounce back,” says Build Bronzeville’s Amos. When the pandemic hit, her organization swiftly aligned with other South Side organizations to urgently deliver vital information to small-business owners through grassroots efforts. “This is not a drill. Now is the time for all of us who want to be resource providers and boil it down for people,” Amos says.

Recognizing that communities with the most funding will have the greatest chance for survival, Amos leverages her relationships and personally calls and sends texts to restaurateurs conveying time-sensitive information like grant deadlines — she has become a lifeline for vulnerable small-business owners during this critical time. Amos has also extended assistance to Dining at a Distance, a delivery and takeout directory, after noticing its site had robust coverage of hot spots in the city, but little representation of South Side restaurants. Amos became a link and added a slew of South Side restaurants to the platform, noting that consumer-facing exposure is urgently needed. “A grim reality is that we have to capture these dining-out dollars now,” she says, “because there will come a point where people will stop ordering out because it just won’t be fiscally responsible for them to do so.”

As we envision a new path for the hospitality industry, black women must be central to the conversation: Their journeys hold wisdom that is widely absent from in-depth studies and data. And there’s no better industry to lead change than one known for breaking bread.

To support her community and staff, VanTrece has launched a pay-what-you-can menu at Twisted Soul, thinking of the model as a fundraiser of sorts. “This is a whole new pricing structure. You’re not pricing to pay the bills and pay the rent,” says VanTrece, whose landlord told her she wouldn’t have to pay a late fee on her rent, which is $10,000 a month. In addition to cashing in her credit card points for gift cards for her staff, she’s turned her restaurant into a hub where they can quickly grab necessities like a hot meal and toilet paper. It’s a service most of her team participates in. “But then I have some that are just scared,” she says. “They don’t want to come and I can’t blame them.”

On a recent Friday, a carryout fish fry was on VanTrece’s menu, a reminder of the ones she grew up going to during better days. She looks to the past for guidance often. “At Cast Iron, we always talked about the strength and the tenacity of our forefathers, and I’m calling upon that strength now to keep me putting one foot in front of the other, because there are times I just want to roll over,” she says. “And I can’t do that. I fought to get this far and I’m going to continue to fight through this.”

Angela Burke is a food writer and the creator of Black Food & Beverage, a site that amplifies the voices of black food and beverage professionals. Shannon Wright is an illustrator and cartoonist based out of Richmond, Virginia.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/3bi4741 via Blogger https://ift.tt/2RKiM0b

0 notes

Quote

History shows us that the novel coronavirus will impact black women restaurateurs, and their businesses, much harder Before the pandemic, our nation was in the early stages of battling an epidemic that plagued our beloved hospitality industry: the biased structural policies, born out of our country’s legacy of racism that guaranteed that black Americans would continuously work at a deficit. Painfully honest conversations — dissecting the ways in which decades of systematic racial and gender inequality festered in the industry — had finally begun to gain traction in on- and offline spaces. But, collectively, we’d barely broken through the dysfunctional infrastructure that allowed certain groups to fail harder and faster when COVID-19 struck. Chef Deborah VanTrece was ringing the alarm prior to the coronavirus pandemic. She regularly brought discussions of industry inequality to the table through her dinner-and-conversation series that centers black women in hospitality. “It was something that we had just started talking about at Cast Iron Chronicles, and a lot of other chefs were talking about it,” says VanTrece, owner of Twisted Soul Cookhouse & Pours in Atlanta. “But the conversation wasn’t finished. It still isn’t.” “As much as we’ve accomplished, I still feel isolated and that I am by myself. I don’t think any of us should feel that way. We should be checking on each other. It’s like [coronavirus] happened and every man for himself,” VanTrece says. “And when I think about it, we were pretty much like that in the first place; that’s why it’s so easy for it to continue now.” Isolation has become a theme in our shared new normal of stay-at-home orders, but what VanTrece is describing is a sentiment long echoed by black women in the industry. Yet seeing the divide continue during these times is heartbreaking for VanTrece. “If we were ever needing to be one, it’s now. We need to be one.” Black and brown voices are largely excluded from overarching conversations that will define the future of our industry As we grapple with lives lost and the magnitude of devastation caused by novel coronavirus, accountability and transparency seem to be overshadowed by crisis-led pivots while we brace ourselves for what’s to come. And yet again, black and brown voices are largely excluded from policymaking and overarching conversations that will define the future of our industry. In the face of this pandemic, some may say the pursuit of equality has been railroaded, maybe even understandably so. Others see the crisis as a hopeful confirmation that institutional change is inevitable. Because if not now, when? In order to know where we are going, we have to understand where we’ve been. Black restaurant owners, black women especially, are in a more precarious position from the get-go. According to the latest figures, from 2017, black women were paid 61 cents for every dollar paid to their white male counterparts, making wealth generation much more difficult. And while one in six restaurant workers live below the poverty line, African Americans are paid the least. Access to capital has been a steady barrier of entry, especially for black women. Black- and brown-owned businesses are three times as likely to be denied loans, and those that are approved often receive lower loan amounts and pay higher interest rates. For a population more likely to rent than other demographics, offering up real estate as collateral for traditional loans isn’t an option. And even for those who own a home, the lasting effects of redlining, predatory and discriminatory lending practices, and low home valuations are palpable. In other words, the wealth gap, combined with a lack of access to traditional loans and investors for start-up capital, puts black women at a disadvantage before they even open the doors of their restaurants. “A lot of us have had to build our businesses from scratch, and that may be through personal savings and loans, through family members, credit cards, or we have refinanced our homes,” says chef Evelyn Shelton, owner of Evelyn’s Food Love, a cafe serving comfort food in Chicago’s Washington Park neighborhood. “We are in uniquely different positions when we start, which makes where we are now even more difficult.” In the East Bay, chef Fernay McPherson, owner of Minnie Bell’s Soul Movement, a food truck turned brick-and-mortar now located in the Emeryville Public Market food hall, is offering a limited carryout menu in an effort to keep her staff afloat, noting that some are single parents. “I was a single mother, so it’s a lot to take in when you’re thinking, ‘How am I going to feed my child? How am I going to make rent?’” During the Great Recession, McPherson was laid off and had to short-sell her home. She started Minnie Bell’s in 2009, as a catering company, while also working full-time as a transit operator in San Francisco. “It was hard being a mom, driving a bus, and trying to operate a business. It was a lot on me. And my decision was me. To work for me.” Working multiple jobs is a necessary for many entrepreneurs whose bootstraps are shorter to begin with, says Lauren Amos, director of small-business development at Build Bronzeville, a Chicago incubator that advocates for South Side business owners. “We’re talking about people literally working a full-time job, supporting themselves and their family while still pursuing this dream of opening a business,” she says. “And they’re doing it out of their own physical pocket.” McPherson, a San Francisco Chronicle 2017 Rising Star Chef, says it was tough getting a job in the restaurant industry after culinary school. “I came into a white, male-dominated field and I was a young, black woman that wasn’t given a chance. My first opportunity was from another black woman and I worked in her restaurant.” Access to a solid professional network, including mentors, is absolutely as vital as access to capital — social capital is another part of the ecosystem, and can be a bridge to resources necessary for growth. But without the right connections, strong networks may be hard to plug into, and exclusion from these networks can have a stifling effect on one’s career. McPherson has steadily established a solid network over the years. Now, she’s envisioning what her post-pandemic future will look like, including a possible alliance with other women chef-owners. “We’re talking about collectively developing our own restaurant group, in a sense, where we can build a fund for each member, build benefits for our employees, and build career opportunities,” she says. In coming weeks and months, people in many industries will be taking stock of what could have been done better. But for now, McPherson’s most pressing need is capital to be able to restart. Studies show that African-American communities were hit hardest by the Great Recession. According to the Social Science Research Council, black households lost 40 percent of wealth during the recession and have not recovered, but white households did. Unemployment caused by the recession disproportionately affected black women, a double-edged sword for many of whom worked lower-wage jobs that relied on tips. The costs of these disparities are far reaching. Six years after a defunct grocery chain shut its doors, creating a food desert in the Chicago South Side neighborhood of South Shore, a new grocery store finally opened — just last December — a few months before the pandemic. Black communities are undervalued. “Mom-and-pop,” a term of endearment that acknowledges the fortitude and nobility in owning a small business, is rarely applied to black-owned businesses. Racial discrimination and biased perceptions of black-owned restaurants in black communities costs them billions of dollars in lost revenue. Disinvestment in these communities sets the landscape for quick-service restaurant chains to flourish, as professor Marcia Chatelain eloquently lays out in Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America, all of which presents added pressure for the competing independent restaurant owners, whose margins are already miniscule. “We’re truly hanging on by a thin thread,” Shelton says. She encourages local legislators to call on neighborhood restaurants and caterers to feed people who are food insecure, as well as individuals at the 3,000-patient field hospital erected at McCormick Place, the Chicago convention center that already houses Shelton’s now-closed second location. Meanwhile, Shelton regularly delivers meals to the ER staff at a neighboring hospital, paid for out of her own pocket. Disparities in restaurants are emblematic of the nation. Indicators show that African-American communities are hit the hardest by COVID-19. ProPublica sums it up: “Environmental, economic, and political factors have compounded for generations, putting black people at higher risk of chronic conditions that leave lungs weak and immune systems vulnerable: asthma, heart disease, hypertension and diabetes.” And a lack of access to quality health care means the novel coronavirus has the potential to disproportionately decimate black communities, and the independent restaurants within them, if adequate support is not provided. History shows us that the most vulnerable are left behind, and a similar pattern will likely occur post-pandemic. “The difference is the ability to be able to bounce back,” says Build Bronzeville’s Amos. When the pandemic hit, her organization swiftly aligned with other South Side organizations to urgently deliver vital information to small-business owners through grassroots efforts. “This is not a drill. Now is the time for all of us who want to be resource providers and boil it down for people,” Amos says. Recognizing that communities with the most funding will have the greatest chance for survival, Amos leverages her relationships and personally calls and sends texts to restaurateurs conveying time-sensitive information like grant deadlines — she has become a lifeline for vulnerable small-business owners during this critical time. Amos has also extended assistance to Dining at a Distance, a delivery and takeout directory, after noticing its site had robust coverage of hot spots in the city, but little representation of South Side restaurants. Amos became a link and added a slew of South Side restaurants to the platform, noting that consumer-facing exposure is urgently needed. “A grim reality is that we have to capture these dining-out dollars now,” she says, “because there will come a point where people will stop ordering out because it just won’t be fiscally responsible for them to do so.” As we envision a new path for the hospitality industry, black women must be central to the conversation: Their journeys hold wisdom that is widely absent from in-depth studies and data. And there’s no better industry to lead change than one known for breaking bread. To support her community and staff, VanTrece has launched a pay-what-you-can menu at Twisted Soul, thinking of the model as a fundraiser of sorts. “This is a whole new pricing structure. You’re not pricing to pay the bills and pay the rent,” says VanTrece, whose landlord told her she wouldn’t have to pay a late fee on her rent, which is $10,000 a month. In addition to cashing in her credit card points for gift cards for her staff, she’s turned her restaurant into a hub where they can quickly grab necessities like a hot meal and toilet paper. It’s a service most of her team participates in. “But then I have some that are just scared,” she says. “They don’t want to come and I can’t blame them.” On a recent Friday, a carryout fish fry was on VanTrece’s menu, a reminder of the ones she grew up going to during better days. She looks to the past for guidance often. “At Cast Iron, we always talked about the strength and the tenacity of our forefathers, and I’m calling upon that strength now to keep me putting one foot in front of the other, because there are times I just want to roll over,” she says. “And I can’t do that. I fought to get this far and I’m going to continue to fight through this.” Angela Burke is a food writer and the creator of Black Food & Beverage, a site that amplifies the voices of black food and beverage professionals. Shannon Wright is an illustrator and cartoonist based out of Richmond, Virginia. from Eater - All https://ift.tt/3bi4741

http://easyfoodnetwork.blogspot.com/2020/04/its-time-for-hospitality-industry-to.html

0 notes