#teimanim

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

People like to portray Judaism as a "European" religion so here's all the love to the non-European Sephardic (Turkish, Latin American, North African, Middle Eastern, Hong Kong, Singapore, etc.), Mizrahim (Egyptian, Lebanese, Syrian, etc.), Teimanim, Maghrebim (Moroccan, Tunisian, Libyan, etc.), Beta Israel, Indian Jews (Cochin, Bene Menashe, Bene Israel, Paradesi, etc.), Jews of China (Kaifeng, Ningbo), Latino Jews, converts, Persians, Bukharians, Mountain Jews, and more.

Also f u you here's love to the Ashkenazim and the Krymchaks and the Georgian Jews and the Sephardim who settled in European lands after the expulsion and Italkim and more.

#jewish#jews are diverse. we're all over the world#and if you don't realize that well. here you go#judaism#jumblr

1K notes

·

View notes

Link

What is a home?

In Jewish history, with its centuries of wandering and ritualized longing for a land most never actually saw, circumstances created not so straightforward answers to this question. For the creators of modern-day Israel, the answer was to be found in a state.

But for some Jewish refugees that arrived in this new place, it did not feel like a home, either.

“Our great-grandmother came to Israel only to be put in a tiny, crowded shack in the desert,” says Tair Haim of A-Wa.

The Tel Aviv-based band A-Wa, comprised of three sisters that fuse Yemenite folk with hip-hop and electronic music, frames its answer around what the sisters’ great-grandmother Rachel, a refugee from Yemen, said about the question of home: “bayti fi rasi” – my home is in my head.

A-Wa’s new concept album, Baiti Fi Rasi, released on May 31st, shares many of the stories they heard as little girls of Rachel, a single mother facing hardship in Yemen as a Jew, a woman — and after she arrived in Israel during Operation Magic Carpet, as an Arabic-speaking Yemenite refugee. As children in the Arava Valley, Tair, Tagel, and Liron Haim would “milk from” their elders the spicy food, the henna and those limb-turning folk tunes of Yemen they had been encouraged to leave in the past. Though they never met her, Rachel became a guiding force in the sisters becoming proud, Jewish Yemenite women.

A single mother and feminist long before the term came in vogue, Rachel never found in her wandering a place she could call home, even after she came to Israel a refugee. But she cried out for “ya watani,” my homeland: Yemen. In spite of her suffering there, it was the sights, the sounds, the smells of Yemen that signaled home for her.

After their 2016 debut album, Habib Galbi, the A-Wa sisters travelled the world, encountering Syrian refugees on the streets of Europe. War ravaged Yemen. Thousands of African asylum-seekers in Tel Aviv continued to be denied refugee status and deemed “infiltrators” by the Jewish state.

“We saw all the refugee issues in all the world, in Israel, in Paris, and it made us think of the journey [Rachel] made,” said Tair “Being musicians seeing so many places, we thought — what is a home to us? Is it a certain person? A village you grew up in? The country? So we decided to put this idea into a concept album.”

The sisters used the childhood stories they heard of Rachel as the basis for the album’s content.

“Her family would hide [this history] – don’t talk about the past, etc. – but for us, we felt our great-grandma in the studio,” said Tair, the eldest sister, at a café in her suburban neighborhood of Ramat Aviv, just north of Tel Aviv.

Though the album includes stories from their great-grandmother’s past, it wasn’t nostalgia A-Wa sought. As they were always told growing up, the past is the past. But as A-Wa conveys through their music, the past can shed light on what’s happening today, interact with it, even become something entirely different — and downright groovy.

The album’s festive but fierce music takes listeners on a hip hop journey of funky keyboards accompanied by rustic tin drums and Yemenite Arabic melodies. “Everything that is a silver plate or whatever, you can drum on it,” said Tair. “The Yemenite woman would sing about lovers and drum on plates, anything they had while they worked, so we wanted to bring that vibe into the studio.”

The band also decided for the album to decidedly bring together fashion of then and now —adorning Yemenite gold necklaces over Adidas shirts and Nike sneakers — to create a new urbo-traditional fusion aesthetic.

“With our fashion, we don’t want to keep it in the past,” said Tair. “We want to bring the tradition and statement to nowadays and make it relevant. There is no use to just bringing something as it was.”

...Even for a Jewish Yemenite refugee, Rachel was resilient, and she was courageous. As her great-granddaughter Tair recalled, Rachel was married off at the age of 12. It was an unhappy arrangement. Soon after giving birth to her daughter, Shama’a, she decided to divorce her husband — norms be damned. She married a second time, but still, luck was not on her side, so she left the man “tight like an old shoe.” Rachel met another man, and they did fall in love, but the daughter of a local sheikh seduced him, and he left Rachel — a story retold in the reggae blues-like song “Bint Al Sheikh.”

Throughout Yemen, Rachel went from village to village, a single mother struggling to find a place they could call home.

...Neither in Ibb nor Sana’a nor the ma’abarot refugee camps of Israel could Rachel find shelter she could call home. So “what is a home?” A-Wa asks again. “Bayti fi rasi,” is their response –

My home is in my head A refugee for my heart Wherever I go, it is with me.

Poor and fleeing persecution, Rachel brought from her homeland only what was intangible, possessions that she kept in the mind and soul. “She took her daughter, her loneliness, her Yemeni food, her father’s weaving and her mother’s tongue,” said Tair. “This is about identity… it’s what every refugee brings.”

The pressure to bury that identity upon arriving in a new place is widely felt among refugees, but in the album, A-Wa takes the story down the particular, dark path that Israel set Mizrahi refugees like Rachel on.

This marks new territory for the band. In their 2014 debut album, Habib Galbi, A-Wa’s music was revolutionary in Israel by its basic nature: three Jewish sisters, born and raised in southern Israel, singing modernized versions of Yemenite folk songs in Arabic. The band’s very existence is an act of rebellion against suppression of Mizrahi culture...

...The call-and-response section of refugee hopes and discriminatory reality — which Tair said was inspired by West Side Story’s similarly themed “I’d Like To Be In America” — describes in stark terms the Yemenite experience after arriving in Israel, including decrepit, overcrowded tent conditions in the ma’abarot, or refugee absorption camps, and the phenomenon in which thousands of Yemenite children disappeared and families say hundreds were abducted by the state and given to childless Holocaust survivors. From those earliest days, MIzrahim were confined to the lowest rungs of Jewish Israeli society, compelled to abandon Arabic and their native culture.

The A-Wa sisters dutifully avoid politics, but their decision to address this past feels timely following last year’s passage in the Knesset of the Nation-State Bill, which downgraded Arabic in Israel from an official language.

“A lot of Jewish people came from Arab countries, and to try to erase their language or identity, it’s really sad,” said Tair. “When Rachel and our grandma, Shama’a, came to Israel, [Israel] wanted to change their names. Shama’a [Arabic for “candle”] became Shoshana, which means rose, not a candle. So [with the Nation-State Bill] we observe it now even.”

By releasing this daringly personal album, the A-Wa sisters resist the forces they had sometimes felt even within their own family. “Maybe our grandparents were ashamed of their culture,” said Tair. “But not only are we not ashamed, we are proud of who we are. We celebrate the many identities that we wear. I’m a woman, I’m a Yemenite, I’m Jewish, I’m a sister… it goes on.”

Through the sisters’ music, however, a revival has taken place.

...For the narrative- and genre-bending A-Wa sisters, the past is no more — but memory isn’t static. It is alive, dynamic and changing with the times so a Yemenite headdress complements sneakers and tin drums turn up the dance-floor in a modern-day hip-hop production. This process that manifests in Baiti Fi Rasi’s music and aesthetic – fusing the cultures of there and here, then and now — is happening among refugees all over the world.

I wondered how the Haim sisters — second-generation Sabras with Hebrew as their native tongue and a wide but sorely incomplete Yemenite vocabulary — would relate to Rachel’s profound words. What can baiti fi rasi mean to them? “We feel we are luckier than the last generations. Israel is a home to us. The village we grew up in the Arava Valley is a home to us. My husband is a home to me,” said Tair. “But the idea of bayti fi rasi means I’m taking my home to everywhere I go. Home is a feeling. It’s a spirit.”

230 notes

·

View notes

Text

It also erases non-Ashkenazi Jews.

My mother's family never spoke Yiddish, they spoke Ladino. And we Sephardim have it easier when it comes to Ashkenormativity than most other non-Ashkenazi Diasporas. They make a few footnotes to our existence while they talk over, appropriate and sometimes flat out ignore others, like the very existence of Judeo-Arabic, or Judeo-Yemenic, which is the closest dialect/language(dialanguage?) to classical Hebrew still in use today.

Has anyone else noticed the weird appropriation of Yiddish for specifically anti-zionist spaces? It makes me deeply uncomfortable.

#jewish#judaism#jewish history#jumblr#sephardi jewish#mizrahi jews#yemenite jews#teimanim#yehudim teimanim

281 notes

·

View notes

Text

i don't really like "judaism isn't just a religion, it's an ethnicity" because that implies that it's all ONE ethnicity. we're not all ashkies. i mean i am but many jews are not. there are MANY jewish ethnicities (sephardi, mizrahi, romaniote, beta israel, kaifeng, teimanim, etc). we are all jews but i feel it's important to acknowledge the vast diversity of jewish experience & cultural practice so as not to center eastern european jews as the default.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

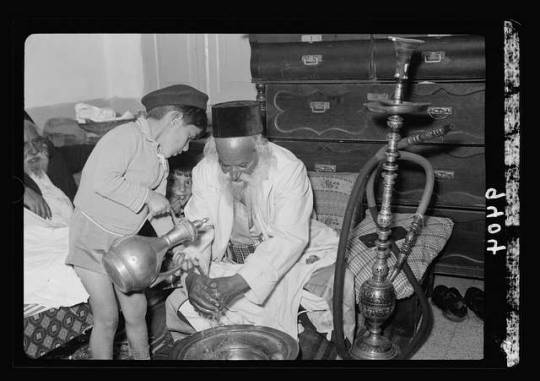

A Yemenite-Jewish family celebrating a Passover Seder, British Mandate Palestine (possibly Tel Aviv or Jerusalem), April 3, 1939. The ceremonial washing of the hands.

#jerusalem#swana jews#mizrahi jews#teimanim#Yemenite jews#Yemeni jews#eretz israel#pessach#passover seder#photography#Jewish history#Jewish heritage#ישראל#ארץ ישראל#ישראבלר#מזרחים#תימנים#פסח#פסח סדר#pesach

100 notes

·

View notes

Note

So... Maki is Jewish now? That's neat. Do you know anything about Judaism? Otherwise I think Kiyo would have to provide classes.

I don’t really. Is there any sort of ritual I need to take?

Not necessarily. I can teach you about the culture and history of the world’s Jewish communities.

There’s more than one?

Surely you don’t think such a vast group would be monolithic. Over time, the Jewish diaspora has diversified into many groups, though all united under a common heritage.

The largest are the Ashkenazim, who descend primarily from Central and Eastern Europe. They are often imagined as the traditional idea of a Jew in the western world.

Interestingly, many have come to associate names ending in suffixes such as “-berg,” “-man,” or “-stein,” or containing “Gold” as inherently Jewish in origin. In fact, this is a byproduct of a 1787 Austro-Hungarian law, decreeing that all Jewish residents of their empire must adopt Germanic family names.

Beyond them, there is also the Sephardim, who descend from the Iberian Peninsula; the Mizrahi, who inhabited much of the Middle East from as far back as the biblical era; the Teimanim, who formed a unique culture in Yemen; the Cochin and Bene Israel communities of India; the Beta Israel of Ethiopia; the Kaifeng Jews of China’s Henan province.

And these merely the many cultural and ethnic identities that have emerged over the centuries. Many denominations exist within their religion, such as the Orthodox, Hasidic, Karaites, Haymanot, Reform, Renewal, and even secularists who may observe Jewish holidays and traditions, but are otherwise non-religious.

In short, you are part of an amazingly diverse community. I would be more than happy to share what I know with you.

I never knew any of this until now.

I’d like that. Thank you.

18 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Smaller Jewish groups include the Georgian Jews and Mountain Jews from the Caucasus; Indian Jews including the Bene Israel, Bnei Menashe, Cochin Jews and Bene Ephraim; the Romaniotes of Greece; the ancient Italian Jewish community; the Teimanim from the Yemen; various African Jews, including most numerously the Beta Israel of Ethiopia; the Bukharan Jews of Central Asia; and Chinese Jews, most notably the Kaifeng Jews, as well as various other distinct but now extinct communities.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jewish_ethnic_divisions

0 notes

Photo

A Yemeinite Habbani family celebratin Passover in Tel Aviv, British Mandate of Palestine, 1946

272 notes

·

View notes

Text

I grew up around people whose parents and grandparents and great-grands came to Israel from Yemen in '49. I don't know why I feel required to say that, except to emphasize that this is not an abstract thing for me. It's the food Ruti would make for Shabbat when my parents went to her house, it's the way the most secular Israeli I ever met would still brag for hours about his grandfather the rabbi who brought his whole congregation safely to Israel, it's a friend asking her mom to spell the town the family came from again, for her school project.

These are real people. They are not abstract 'brown Jews' who can be propped up like paper dolls to mean anything you want without their permission.

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

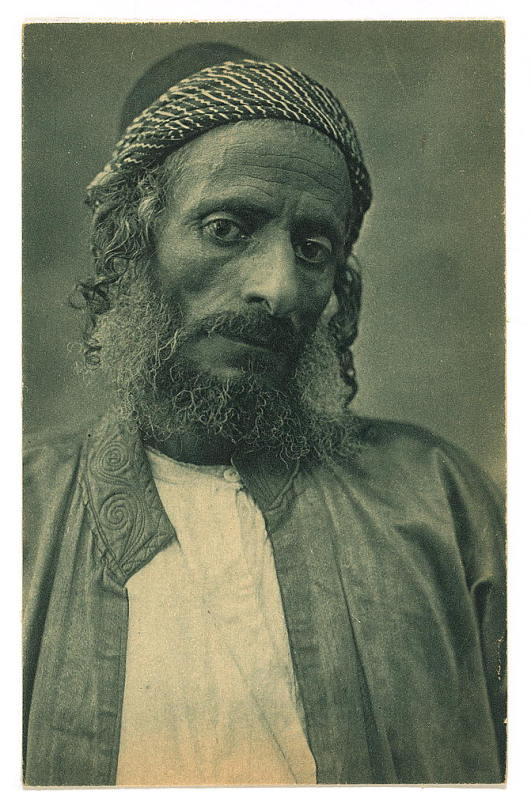

A Yemenite Jew in Jerusalem, 1921. Originally published under the name "A Vernomito Jew in Jerusalem" as a postcard; vernomito is a misspelling of Yemenite.

358 notes

·

View notes

Note

what was the state where jews were told that if they didn't leave the law wouldn't protect acts of violence against them? I remember this happening a few months ago but there was so little coverage of it that I can't seem to find the details...

Yemen.

Here’s more info: Yemenite government to Jews: Convert or leave Yemen, Israeli politician says Yemen’s last Jews need help to get out, Yemen to Jews: Convert, Leave or Die

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Yemenite-Jewish family celebrating a Passover Seder, British Mandate Palestine (possibly Tel Aviv or Jerusalem), April 3, 1939. The eating of the herbs / Maror מָרוֹר to represent the bitterness of slavery which the Israelites experienced in Egypt.

#jerusalem#swana jews#mizrahi jews#teimanim#Yemenite jews#Yemeni jews#eretz israel#pessach#passover seder#photography#Jewish history#Jewish heritage#ישראל#ארץ ישראל#ישראבלר#מזרחים#תימנים#פסח#פסח סדר#maror#מָרוֹר

35 notes

·

View notes