#tagore society

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#csr#csr initiatives#corporate social responsibility#fiinovation csr#business#fiinovation#reviews#finance#fiinovation reviews#fiinovation linkedin#project suno#hearing solutions#hearing loss#v guard#tagore society#society#rural development#fiinovation funds#funds#founder#fundraising#hearing

0 notes

Text

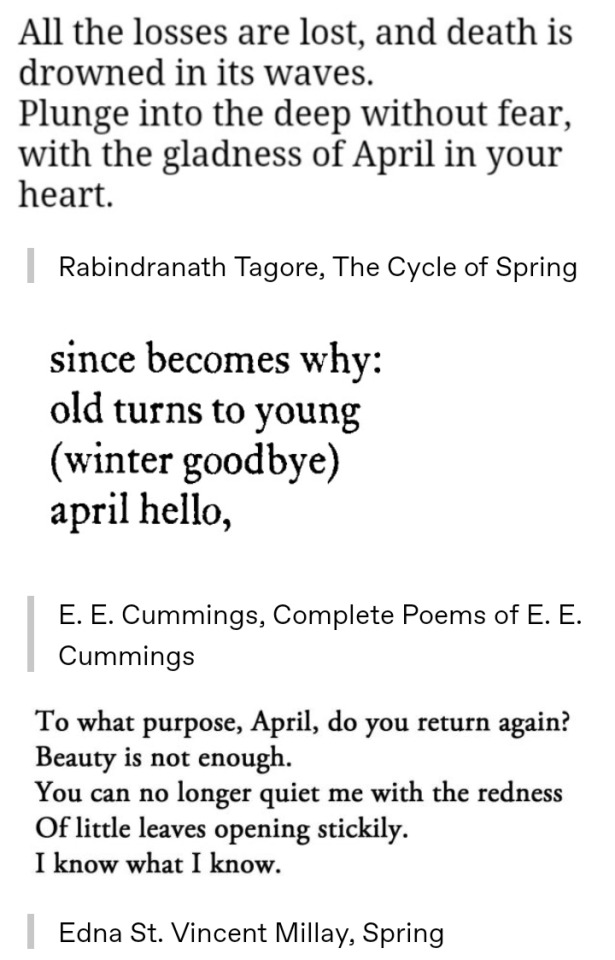

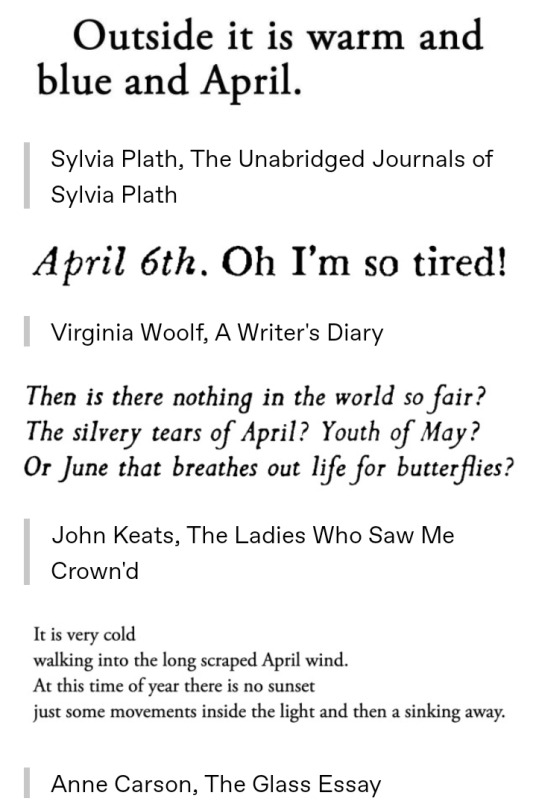

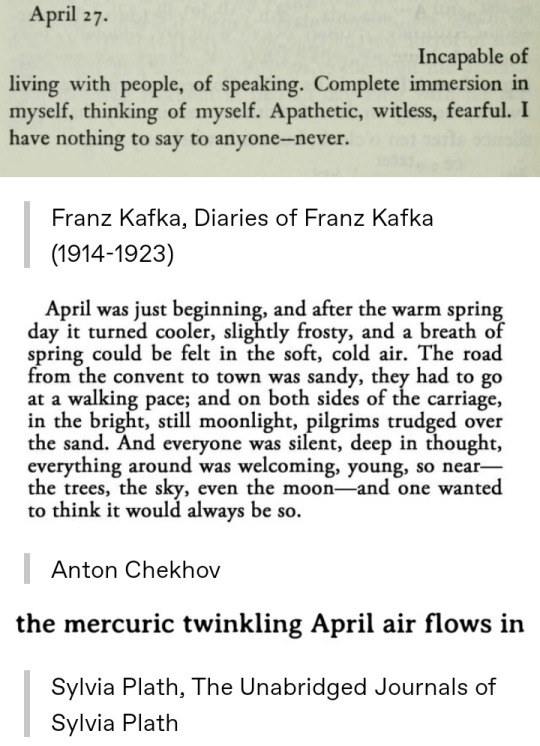

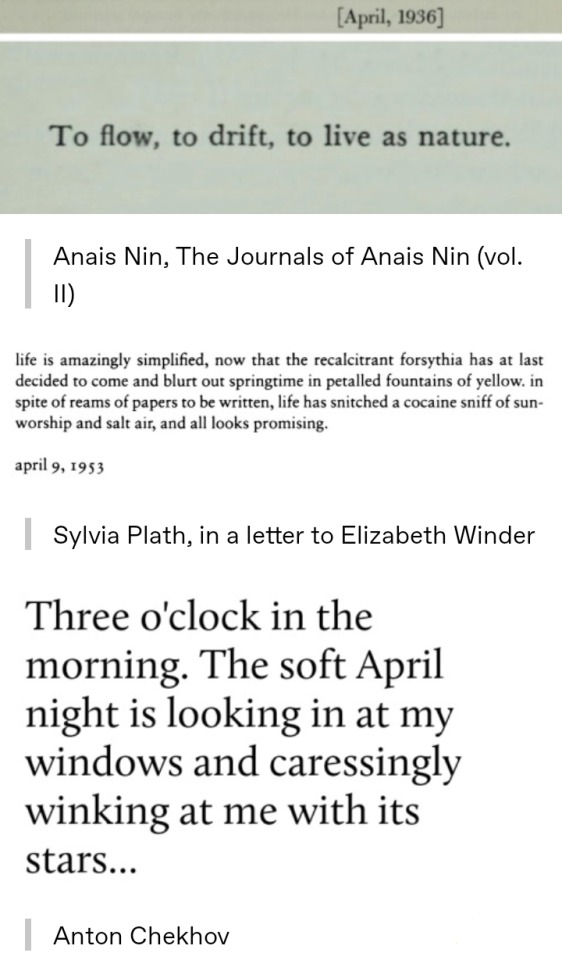

Franz Kafka, Diaries of Franz Kafka (April 8, 1914)

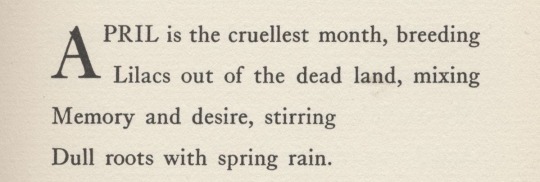

T. S. Elliot, The Wasteland

Naguib Mahfouz, Adrift on the Nile

Edna St. Vincent Millay, Song of a Second April

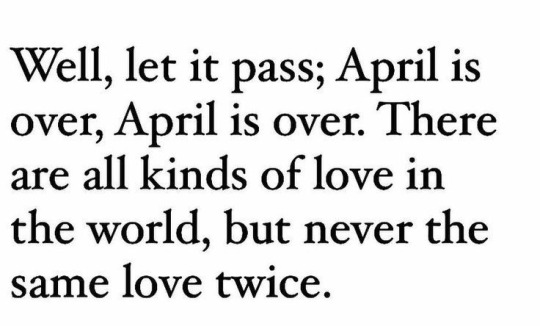

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Short Stories

#franz kafka#kafkaesque#sylvia plath#sylvia plath quotes#anne carson#rabindranath tagore#ee cummings#dead poets society#sad poetry#english poetry#sylvia plath poetry#poetry tumblr#john keats#virginia woolf#anais nin#scott fitzgerald#dealing with grief#nerd stuff#dark academia#academia aesthetic#april#april quotes#poetry#april 6th#trending#taylor swift#mental health#sad thoughts#english literature#sad poem

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

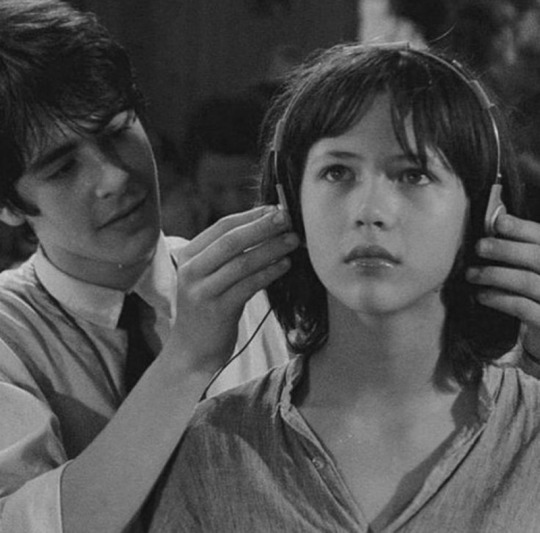

#divider by v6que#unending love (poem) by rabindranath tagore#kyunyu3 🛶#♡ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀#jaehyun messy icons#jaehyun messy moodboard#jaehyun moodboard#jaehyun#jaehyun nct#nct moodboard#nct messy layouts#nct messy icons#neo culture technology#nct 127 moodboard#nct 127 jaehyun#nct 127 messy moodboard#dead poets society#kpop#aesthetic#moodboard#messy icons#messy lq#messy moodboard#vintage moodboard#kpop moodboard#⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀#thank you and God bless you<3

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

They say why is it so important for me, Suvrahadip Ghosh, an Indian poet/writer to write so much. I don't mean, just in volume. I mean, 'so much' as in PROFOUND ENOUGH TO IGNITE ANOTHER MIND. I can't explain the importance of it without this - Do you know why it was so important for Rabindranath Thakur to write so vehemently and so beautifully and so poignantly even during the days he suffered more than anyone? So that decades later when kids like me read his work and learn his story, we are inspired to pick the pen up. And write. And write. And write. I want to do the same for another kid.

Suvrahadip Ghosh

#poems on tumblr#poetry#love poem#dead poets society#literature#ruinsbysuvrahadipghosh#love poems#poetry book#poems and quotes#excerpts#rabindranath tagore#indian literature

1 note

·

View note

Text

Propaganda

Irene Dunne (The Awful Truth, Theodora Goes Wild, My Favorite Wife)— The first time I saw her in Theodora Goes Wild she struck me dumb because who is that BEAUTIFUL woman being so funny and clever??? She was primarily known as a dramatic actress (and believe you me those are muscles she can FLEX, Penny Serenade hurts my feelings) but she’s also one of the funniest screwball leading ladies I’ve ever seen. Her films with Cary Grant are especially charming, but all her characters have this knowing quality in the heart of them that’s so intriguing, and her screwball girlies have this freedom to go after what (or who) they want that is delightfully subversive. I want to be her, I want to fuck her, I want to see every movie she’s ever done, she is a brilliant actress and she is my dream woman.

Devika Rani (Achhut Kanya)—She was grandniece of Rabindranath Tagore (laureate). She was sent to boarding school in England at age nine and grew up there. After completing her schooling, she joined the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) and the Royal Academy of Music to study acting and music, at a time when aristocratic women did not enter showbiz. She studied filmmaking in Berlin. It is well known that she underwent training at the UFA Studios in the art and technique of acting under Eric Pommer, and other aspects of film production including costume and set designing and make-up, under eminent directors like GW Pabst, Fritz Lang, Emil Jannings and Josef von Sternberg. She is also reported to have worked with Marlene Dietrich. She had a multi-faceted personality and took on many responsibilities of film production at Bombay Talkies, a studio that she co-founded with Himanshu Rai in Mumbai in 1934. She often took care of hair and make up, supervised set design and editing, scouted for new talent and mentored them. She was the face of Bombay Talkies, and also the reason behind the political and financial backing the studio received, at a time when even women from red light districts refused to work as actresses. She was the first recipient of the Dadasaheb Phalke Award, when it was instituted in 1970.

This is round 2 of the tournament. All other polls in this bracket can be found here. Please reblog with further support of your beloved hot sexy vintage woman.

[additional propaganda submitted under the cut.]

Irene Dunne:

irene excelled in screwball comedies, musicals, melodramas...she could do it all. she often played elegant society ladies and brought sparkling charisma and poise for days to anything she did, and sang like an angel (she pursued opera before going into moves), her rendition of jerome kern's "smoke gets in your eyes" in roberta moves me to tears every time.

youtube

A fantastic star of screwball comedies Irene Dunne is an undersung hot woman in my opinion. She rose to fame in her roles alongside the likes of Cary Grant, and was usually the funniest person in her movies. And the hottest.

She's snarky, and quick, prone to rolling her eyes, and eager to trip her counterparts up. In short, she was a devilish, charming, problem of a woman in many of her films, the pinnacle of hotness.

She’s so gorgeous and funny and her way of acting is so fresh and timeless! She’s the complete package of hotness to me with her talents, humor, and, of course, hot looks. I named my left tit after her to hopefully attract even a smidgen of her beauty and charm.

Devika Rani:

Achhut Kanya (1936) is the only one of hers I've seen but hot DAMN

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saheb, Bibi aur Ghulaam

#3

Thank you to the lovelies @arshifiesta for celebrating IPK and setting up the great moodboards and AU.

1878, Calcutta

Eleven years old Arnav Mullick had not spoken a word in a year.

Some thought it was his parents' traumatizing deaths that led to his silence. But death was nothing new. The house had lost its middle son, his Mejda Akash at tender age of 19.

So no, death made no difference to Arnav. In fact he was happy when his philanderer of a father died of drinking as well. He deserved it. Not once had he seen his father home at night.

Arobindo Mullick would often scoff when stopped, that if any man of this house had ever spent a night in his own house?

So then some speculated that Arnav's behavioral issues had gotten worse, hence why he stopped speaking for a year.

If his darling mother was alive, she would've wrestled with anyone who thought such against her Arnob. Shyam, Arnav's Borda (boro-dada = older-brother) would perhaps be the only one to chuckle and agree with the society. Arnav was tempestuous as a child.

But quiet? Never quite.

The society would never understand that it was Akash's falling for a Baiji (courtesan) at the age of seventeen, his frequent visits leading his early introduction to alcohol despite their mother's best to protect them for it that hurt Arnav the most.

This was when Arnav swore off love.

That his otherwise pious brother was gullible to follow his father's footsteps to a kotha - where Arobindo Mullick spent all his nights.

It was his mother's haunted face and tears that left Arnav speechless. Or rather Arobindo's reply to her request to stay at home.

Has any Mullick ever spent a night in their own home?

This was when Arnav swore off marriage.

Or that despite Raja Rammohan Roy having abolished Sati-pratha a good sixty years ago, Arnav's mother was dragged to her undeserving husband's pyre by her conservative in-laws to follow patni dharam.

This was when Arnav swore off religion.

But if maa was alive, what life would she have had? Arnav saw how his uncle, Kaku, eyed her. And Arnav had seen that in the months prior to his mother's death, how she was shaved, dressed in white and forced into a strictly ritualistic dreary life.

His mother, whose hair spilled like the Ganges from Himalaya, had a beauty who could rival the Goddess, lived a life none deserved simply out of rituals and religion.

Thus when Shyam gave their mother mukh-agni, Arnav found his devotion die in his mother's pyre. And when his only hope, Borda (Shyam) set sail to London abandoning him, his words died as well.

-- -- --

1880, Calcutta

Arnav had been wrong about Borda. He returned as a Barrister from London, swiftly kicking out Kaku (father's younger brother) by bringing up property possession rights and threatened the rest of the Mullicks with incarceration for having forced their mother to die.

Thirteen years old Arnav did not know what to do when the brother he thought so wrongly about did the most just thing. It was then he decided that he too would run away to London when he came of age.

But the other thing he couldn't figure out was what to do with Boudi (bhabhi; sister in law). Their grandmother had fixed Borda (Shyam's) alliance with a member of the Tagore family.

Barely two years older than him, fifteen years old Anjali Devi was to manage the household of a twenty five years of Shyam Mullick. How could Arnav accept her as the lady of the house when the post truly belonged to Maa and only her.

But Arnav realized no rebellion was needed. Boudi arrived with the biggest reverence to their mother, along with the grief of losing her own. She chatted constantly with Arnav, not questioning his silence at all - Borda had gotten fed up after a few tries.

And over the years Arnav realized he had a sibling more in Boudi than in Borda.

Perhaps, perhaps maa's essence found its way into Anjali Boudi. It would explain why Arnav's first words were celebrated by Anjali as if it was her first child who had uttered their first words.

A child she was unable to give through all of her married life.

And perhaps his family was cursed against joy for the moment Arnav saw his mother in Anjali, he saw his father in Shyam.

The easy money he made as a barrister faded quicker given his lavish expenditure in trying to out-host the British and the Indian royalties. He belittled Anjali's lineage as much as he could and tried to prove that he was a bigger industrialist than the Tagores.

Lawyer he was, businessman he wasn't.

And thus at age eighteen Arnav had to run to London, no longer chasing any dream, but at least attempting to make the fortune his brother boasted of having.

-- -- --

1893, London

London was far more accommodating than India would ever be. This was what Arnav believed until, of course, an intellectual sparring with Boudi's cousin - Rabindranath - would get him thinking about perspectives.

To think of it, majority of India's existing regressive laws were nothing but British Victorian laws.

Then who was regressive?

It had been a lazy afternoon where Arnav was entertaining his thoughts, alone, as usual when a telegraph changed his life.

URGENT STOP SHYAM DA MARRYING AGAIN STOP

Arnav tossed the telegraph aside, grabbed his documents and hailed the first ship - premier class - to India.

He only had two goals.

Stop Shyam Mullick from marrying and ruin everybody who stood as an obstacle to Bo- Didi's happiness.

-- -- --

A/N: Yes, babua is here and so is his very very painful history! Lemme know what you all think :)

Tagging @shiyaravi @maansiloves @featheredclover @chutkiandchotte @laad-governess @msbhagirathi @phuljari @hand-picked-star @barshifan (updating it slowly and steadily)

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have a few questions for Tagor, Twixandur, Ignir (autocorrect keeps changing it to ignore lmao), Glaca and Jirixa

1) If either of them found a wallet/a bag of gold on a street, what would they do?

2) When they are sick, how do they behave?

3) What is the most controversial opinion of each of them? (in relation to the society they live in, so hating elves is not controversial, it's very normal)

Ohhh, thanks for the ask. I love yapping about them

I will go through question by question

1) Tagor would go out of his way to bring it back personally and take no reward, or at least bring it to the nearest lost and found place if he’s in a hurry.

Twixandur would take the whole thing and use any documents to his advantage. He has probably a collection of lost and “lost“ things. If he can’t for some reason, it’s going in the gutter

Ignir would give it back with an exorbitant finders fee made possible by a very creative reading of the law, after he checked whose it is and if there is anything blackmail worthy.

Jirixa would not go out of her way to find the owner, but would bring it to a lost and found

Glaca would not bother if it does not belong to one of her people. Not her problem, she is busy. Even if it is owned by an fellow hobgoblin she would just hand it to one of her minions to figure out

2)Tagor is usually never sick he is incapable of being so. If he ever was it would be a drama in ten acts.He would think he is dying for real and would need a super comfy place and at least one person to constantly reassure him and hold his hand.

Twixandur is sick constantly, his immune system is weak and folds instantly. He needs to stay in bed and rest if he has even the slightest cold, or else it will get a lot worse. He hates that, but usually sees reason. He also reads a lot when sick.

Ignir would be such an drama queen, he will be fine and is aware of it, but acts as if he is suffering hell torture

Jirixa probably has a lot of herbal mixes to relieve the symptoms and rests for a bit.

Glaca does not rest ever. As long as she can move she will do her job. She could have every sickness on the planet on the same time and yet would still refuse to slow down, unless her god tells her to stop himself in person.

3) Tagor does not care for his followers

Twixandur has more controversial thoughts than not, he thinks bodily strength is completely overrated. He can achieve all he wants through trickery and charm.

Ignir thinks he is better than his superiors and should be the main warlord.

Jirixa does not see the purpose of war and conflict

Glaca likes dwarfs a lot. Is very fascinated by their culture and technology

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

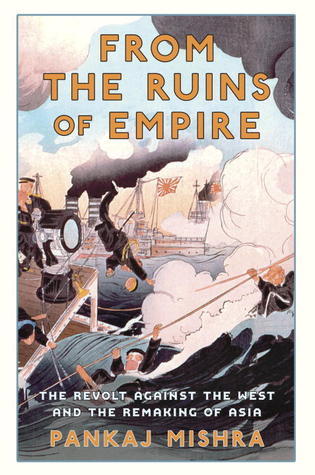

2024 Book Review #27 – From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt Against the West and the Remaking of Asia by Pankaj Mishra

Yet another work of nonfiction I picked up because an intriguing-sounding quote from it went viral on tumblr. This was the fifth history book I’ve read this year, but the first that tries very consciously to be an intellectual history. Both an interesting and a frustrating read – my overall opinion went back and forth a few times both as I read and as I put together this review.

The book is ostensibly a history of Asia’s intellectual response to European empire’s sudden military and economic superiority and political imperialism in the 19th and 20th centuries, though it’s focus and sympathy is overwhelmingly with what it calls ‘middle ground’ responses (i.e. neither reactionary traditionalism nor unthinking westernization). It structures this as basically a series of biographies of notable intellectual figures from the Islamic World, China and India from throughout the mid-late 19th and early 20th centuries - Liang Qichao and Jamal al-Din al-Afghani get star bidding and by far the most focus, with Rabindranath Tagore a distant third and a whole scattering of more famous personages further below him.

The central thesis of the book is essentially that the initial response of most rich, ancient Asian societies to sudden European dominance (rung in by the Napoleonic occupation of Egypt and the British colonization of India) was denial, followed (once European guns and manufactured goods made this untenable) by a deep sense of inferiority and humiliation. This sense of inferiority often resulted in attempts by ruling elites and intellectuals to abandon their own traditions and westernize wholesale (the Ottoman Tanzimat reforms, the New Culture Movement in China, etc), but at the same time different intellectual currents responded to the crisis by synthesizing their own visions of modernity, and tried to construct a new world with a centre other than the West.

I will be honest, my first and most fundamental issue with this book is that I just wish it was something it wasn’t. Which is to say, it is a resolutely intellectual and idealist history, convinced of the power of ideas and rhetoric as the engine for changing the world. Which means that the biography of one itinerant revolutionary is exhaustively followed so as to trace the evolution of his world-historically important thoughts, but the reason the Tanzimat Reforms failed is just brushed aside as having something to do with europhile bureaucrats building opera houses in Istanbul. Not at all hyperbole to say I’d really rather it was actually the exact opposite – the latter is just a much more interesting subject!

Not that the biographies aren’t interesting! They very much are, and do an excellent job of getting across just how interconnected the non-Western (well, largely Islamic and to a lesser extent Sino-Pacific) world was in the early/mid-19th century, and even moreso how late 19th/early 20th century globalization was not at all solely a western affair. They’re also just fascinating in their own right, the personalities are larger than life and the archetype of the globe-trotting polyglot intelligentsia is one I’ve always found very compelling. While I complain about the lack of detail, the book does at least acknowledge the social and economic disruptions that even purely economic colonialism created, and the impoverishment that created the social base the book’s subjects would eventually try to arouse and organize. And, even if I wish they were all dug into in far more detail, the book’s narrative is absolutely full of fascinating anecdotes and episodes I want to read about in more detail now.

Which is a problem with the book that it’s probably fairer to hold against it – it’s ostensible subject matter could fill libraries, and so to fit what it wants to into a readable 400-page volume, it condenses, focuses, filters and simplifies to the point of myopia. Which, granted, is the stereotypical historian’s complaint about absolutely anything that generalizes beyond the level of an individual village or commune, but still.

This isn’t at all helped but the overriding sense that this was a book that started with the conclusion and then went back looking for evidence to support its thesis and create a narrative. Which is a shame, because the section on the post-war and post-decolonization world is by far the sloppiest and least convincing, in large part because you can feel the friction of the author trying to make their thesis fit around the obvious objections to it.

Which is to say, the book draws a line on the evolution of Asian thought through trying to westernize/industrialize/nationalize and compete with the west on it’s own terms (in the book’s view) a more authentic and healthy view that rejects the western ideals of materialism and nationalism into something more spiritual, humane, and cosmopolitan, with Gandhi kind of the exemplar of this kind of view. It tries to portray this anti-materialistic worldview as the ideology of the future, the natural belief system of Asia which Europe and America can hope to learn from. It then, ah, lets say struggles to to find practical evidence of this in modern politics or economics, lets say (the Islamic Republic of Iran and Edrogan’s Turkey being the closest). It is also very insistent that ‘westernization’ is a false god that can never work, which is an entirely reasonable viewpoint to defend but if you are then you really gotta remember that Japan/South Korea/Taiwan like, exist while going through all the more obvious failures. One is rather left feeling that Mishra is trying to speak an intellectual hegemony into existence, here. (The constant equivocation and discomfort when bringing up socialism – the materialistic western export par excellence, but also perhaps somewhat important in 20th century Asian intellectual life – also just got aggravating).

It’s somewhere between interesting and bleakly amusing that modernity and liberal democracy have apparently been discredited and ideologically exhausted for more than one hundred years now! Truly we are ruled by the ideals of the dead.

I could honestly complain about the last chapter at length – the characterization of Islam as somehow more deeply woven in and inextricable from Muslim societies than any other religion and the resultant implicit characterization of secular government as necessarily western intellectual colonialism is a big one – but it really is only a small portion of the book, so I’ll restrain myself. Though the casual mention of the failures of secular and socialist post-colonial nation-building projects always just reminds me of reading The Jakarta Method and makes me sad.

So yeah! I felt significantly more positively about the book before I sat down and actually organized my thoughts about it. Not really sure how to take that.

#book review#history#From the Ruins of Empire#From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt Against the West and the Remaking of Asia#Pankaj Mishra

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

A lot went into creating Alhatham and Kaveh and how they contribute to the major themes of the chapter

I do think Alhaitham was meant to channel some of Nietzsche's worldviews, especially with regards to his elitism (since Nahida voices that concern in her voiceline about him), but ultimately just comes across as an egoist. The fact Haitham references Tagore, whose lectures (some of them) seem to be in response to Nietzsche, in his teaser and the conclusion of his arc being that he refuses the position of Acting Grand Sage both act as a denial of Nietzsche rhetoric

Kaveh has Zoroastrianism, the origin of western morals that Nietzsche was critical of, and Schopenhauer, a hero turned clown for Nietzsche (and Indian philosophy grifter) in his corner of all things, but also, and I don't understand why, fucking Ayn Rand

I want to believe miss Rand ripped off someone else who Hoyo chose as their inspiration and I just don't know who they are, but until then I have to use her name

I think fans find a bit of a dissonance between Kaveh's altruism and his idealism in art, maybe because he used all that money in such a self interested project instead of a selfless cause. Not hoyos best writing imo? Lol

Rand was an egoist who wrote fiction to shape her idea of her ideal man, something she used as a political tool against socialism in favor of capitalism, but hoyo didn't bring up ideology so I won't either.

In The Fountainhead, the protagonist is an architect who often argues with his clients and faces many difficulties in his commitment to his artistic ideals, going against an industry and a society that doesn't value innovation. The character itself and the story are pretty annoying and unlikeable, I'm just making it sound appealing, but it's pretty much the structure of Kaveh's struggle in his own line of work.

The difference is, in the novel the values the protagonist challenges are that of tradition with his ideals of modernism that neglect aesthetics. Kaveh is a pretty grounded architect in that regard, he does prioritize practicality and is realistic with budgets, but he also respects the aesthetic aspect of his work, the main struggle of his character is the devaluation of arts after all.

To me, what stands out is the intention behind this. The Fountainhead is more or less a statement on individuality (though Rand for sure tried to pass it as individualism), of going against what's established and what the society enforced through collective pressure. I think there is value in Hoyo making the same point with a character that embodies everything Rand was critical of (and other egoists like Stirner and Nietzsche): altruism, self sacrifice, compassion, collectivism. Kaveh defends and upholds the value of his individuality while sporting the ethical philosophy that egoists claim does the complete opposite. The message of the novel is something like "only through egoist values can man assert his individuality, altruists are dumb and lose their identity" yet here hoyo does the same with an altruist

The personality of the protagonist fits completely that of Alhaitham, he's a wild exploration of what Ayn Rand characters would look like if they weren't fucking annoying.

Something that immediately struck me was the fact Rand removed all (except for two) instances of the protagonist sharing his inner world, the narration of his inner monologues that Rand wrote in the draft didn't make it to the published version. This is because it made the protagonist come across as calm and collected, logical at all times in his behavior and his decisions in contrast to the other characters who share their anxieties, insecurities and frustrations. Likewise, the audience never finds out what Alhaitham is feeling at any point of the story. Even during the aq when traveler reveals his experience in Sumeru, the narration shares something relevant about Cyno (vague, but personal all the same) yet about Alhaitham it only says he's interested. Other than that, his story quest is also a larger reference to the novel, but not that important in terms of his character.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I saw a lot of criticism by the Sanghis that Hindu mythology is not something one should write fanfiction about or that it's a religion, and therefore people shouldn't interpret and create stories of their own. But let me tell you something: the culture of fanfiction and re-interpretation of Hindu mythology is not at all new; it has been going on for decades.

So, as I said before in the blog, I am a Bengali, so most of the examples I will give are from Bengali literature. So Krishna is a huge part of these fandoms, and a lot of people write and draw things related to him. But this is definitely not a new thing; it has been going on since the time of Joydev's Geeta Govinda and Vidyapati's Vaishnav Padabali. There is a famous poem by Rabindranath Tagore:

শুধু বৈকুণ্ঠের তরে বৈষ্ণবের গান!

পূর্বরাগ, অনুরাগ, মান অভিমান,

অভিসার, প্রেমলীলা, বিরহ মিলন,

বৃন্দাবন-গাথা,—এই প্রণয়-স্বপন

শ্রাবণের শর্ব্বরীতে কালিন্দীর কূলে,

চারি চক্ষে চেয়ে দেখা কদম্বের মূলে

সরমে সম্ভ্রমে, —এ কি শুধু দেবতার!

Which translates to

"Are the songs of Vaishnav for Baikuntha alone?

Courting, attachment, sulkiness, sensitiveness,

Tryst, dalliances, parting and union, theme of,

The songs of Brindaban – this dream of love,

In the Shraban night on the bank of the Kalindi

The meeting of the four eyes under the Kadambatree

In blushing adoration - are these all for the Lord?

Most of the Vaishnav Padaboli and Radha Krishna Leela poets were very much influenced by their personal lives, which makes sense because they never really saw Radha Krishna with their own eyes, so obviously they need some kind of reference and muse for their works. For example, it is said that Vidyapati drew inspiration from the real relationship between a man and woman in that contemporary period for Radha and Krishna. He created the character of Radha from the very image of an adolescent, joyous young girl of that time period. His radha has a lot of human qualities. Then Chandidas, another important poet, apparently based Radha on his own lover, Rami. Rami was a lower-caste woman with whom Chandidas had an affair, but he couldn't marry her because it was not socially acceptable. Chandidas's Radha is portrayed as a sad woman, mourning for her lover from the very beginning, even before she meets Krishna, and it didn't change even when she was united with Krishna, as she was based on Rami, a woman who could never be with the man she loved due to society. Apart from them, the poets who composed Radha Krishna hymns during and after the rise of Sri Chaitanya in Bengal started including Chaitanya in their poetry. They wrote hymns dedicated to Chaitanya alongside Krishna; some of them even started crafting similar descriptions and personalities for both Radha and Chaitanya. It's from their narrative that Radha's love for Krishna symbolises devotees love for god; it was literally Krishna x Chaitanya. CHAITANYA FANFIC!!)

Apart from Vaishnav Padabali, we can also find examples of such works in Sakhta Padabali. For example, the whole concept of Durga pujo in Bengali is inspired by married women visiting their paternal family once a year with their children. The poets basically localised the mighty goddess Durga as a young girl married to Shiva, who is old and penniless. Several poets, like Ramprasad Sen and Kamalakanto (I don't remember his title), wrote hymns from the point of view of Menaka (Parvathi's mother) as she begged Giriraj (Parvati's father) to bring her daughter back. She chides Giriraj for marrying her young daughter to Shiva, who is old and penniless and roams in the crematorium with his ghost acquaintances. She worries about her young daughter suffering all alone in the Himalaya with no one to take care of. Isn't this also a kind of fanfiction? Where goddesses are made into normal women?

Also, if we talk about Mahabharat and the Ramayana, they also had fanfiction even before the rise of Wattpad and Tumblr. All the translations (except a few) adopted these epics in such a way that they could fit into their culture and contemporary society. It's a known fact that Tulsidas's Ramayan deviates a lot from the original one (Maya Sita, vegetarianism, etc.).

So in a way, it can be a retelling of some sort. So if we are shitting upon the culture of retelling and fanfiction, we should also talk about these examples, not only the modern ones. The truth is that retellings and fanfictions are necessary for these types of stories to survive. It makes sense that one modifies these age-old stories so they can fit into contemporary society. Every piece of ancient literature, be it the Greek epics, the Bible, or Hindu mythology, has its own share of retelling and fanfiction. These are not owned by a certain group of people; they don't have the right to gatekeep. People can and should explore these stories from their own point of view. They have the right to rewrite and retell the stories from a modern perspective. So before you chide a blog on Tumblr for writing Mahabharata-inspired fanfiction or incorrect quotes or bully them for writing a canonically incorrect ship,or critices them for writing self insert fic with Krishna stop and think for a second.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Online Treasure of Sufi and Sant Poetry

Introduction

Understanding the Essence of Sufi and Sant Poetry

Define Sufi Poetry

Define Sant Vani

Importance and relevance in modern times

Sufi/Sant Poetry: A Rich Heritage

Historical Background

Origins of Sufi Poetry

Development of Sant Vani

Famous Sufi Poets and Their Contributions

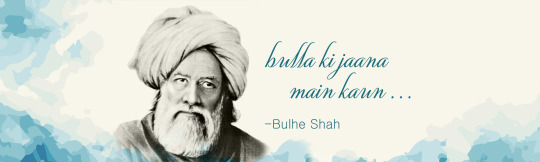

Bulleh Shah

Rumi

Amir Khusro

Renowned Sant Poets and Their Works

Kabir

Tulsidas

Guru Nanak

Sant Vani: The Spiritual Songs

Definition and Importance of Sant Vani

Connection with spirituality and daily life

Prominent Themes in Sant Vani

Love

Devotion

Humanity

Notable Compositions in Sant Vani

Kabir's Dohas

Guru Nanak's Bani

Tulsidas' Ramcharitmanas

Sufi Qawwalis: The Soulful Melodies

Origins and Evolution of Qawwali

Historical context and cultural significance

Famous Qawwals and Their Contributions

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan

Sabri Brothers

Abida Parveen

Impact of Qawwalis on Society

Influence on music and cinema

Role in spiritual gatherings

Sufi Kalam: The Divine Verses

Meaning and Importance of Sufi Kalam

Spiritual and philosophical insights

Key Figures in Sufi Kalam

Rumi

Hafez

Shah Hussain

Popular Sufi Kalam Collections

Mathnawi by Rumi

Diwan-e-Hafiz

Heer Ranjha by Waris Shah

E-Books: Accessing the Treasure

Availability of Sufi and Sant Poetry E-Books

Benefits of digital access

Top Online Platforms for Sufi and Sant E-Books

Sufinama

RekhtaBooks

Project Gutenberg

Recommended E-Books for Sufi and Sant Poetry

"The Essential Rumi" by Coleman Barks

"Songs of Kabir" by Rabindranath Tagore

"The Conference of the Birds" by Attar of Nishapur

Conclusion

The Continuing Relevance of Sufi and Sant Poetry

Modern interpretations and adaptations

Influence on contemporary literature and art

Exploring Further

How to engage with and study Sufi and Sant poetry

Online resources and communities

Example Content Sections:

Understanding the Essence of Sufi and Sant Poetry

Sufi and Sant poetry are two deeply spiritual and philosophical traditions that have enriched the cultural and literary heritage of South Asia and beyond. Sufi poetry, often associated with mysticism and the quest for divine love, is known for its profound depth and emotional resonance. Sant Vani, on the other hand, comprises the devotional songs of the Sant tradition, emphasizing ethical living, devotion to God, and social equality.

These poetic forms have not only provided spiritual solace to millions but have also acted as a medium for social reform, challenging rigid societal norms and advocating for a more inclusive and compassionate worldview.

Famous Sufi Poets and Their Contributions

Bulleh Shah Bulleh Shah is one of the most celebrated Sufi poets whose verses transcend the boundaries of time and culture. His poetry, written in Punjabi, is a testament to his profound spiritual journey and his quest for unity with the Divine. Bulleh Shah’s works, such as "Bulleya Ki Jaana Main Kaun," are timeless classics that continue to inspire and resonate with readers around the world.

Rumi Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi, more commonly known as Rumi, is perhaps the most famous Sufi poet in the world. His works, written in Persian, have been translated into numerous languages and are widely read across the globe. Rumi’s poetry, encapsulated in his magnum opus "Masnavi," explores themes of divine love, the soul’s journey towards God, and the nature of existence.

Amir Khusro Amir Khusro, a prolific Persian poet and a disciple of Nizamuddin Auliya, made significant contributions to Sufi literature and music. He is often credited with the invention of several musical instruments and the development of new genres of poetry. His ghazals and qawwalis are integral to the Sufi musical tradition and continue to be performed with great reverence.

Prominent Themes in Sant Vani

Sant Vani, the poetic expressions of the Bhakti saints, often revolve around themes of love, devotion, and social justice. The Bhakti movement, which gave rise to Sant Vani, sought to transcend the barriers of caste and creed, promoting a direct and personal relationship with the Divine.

Love and Devotion The Bhakti saints, such as Kabir and Guru Nanak, emphasized the importance of love and devotion in their teachings. Kabir’s dohas (couplets) are renowned for their simplicity and profound wisdom, urging individuals to seek the Divine within themselves and to practice love and compassion in their daily lives.

Humanity and Social Equality The Bhakti poets often used their verses to challenge societal norms and advocate for social justice. Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, composed hymns that spoke against the caste system and gender discrimination, promoting the ideals of equality and universal brotherhood.

Famous Qawwals and Their Contributions

Qawwali, a form of Sufi devotional music, has a rich history and a profound impact on South Asian culture. This genre, characterized by its repetitive and hypnotic melodies, is designed to induce a state of spiritual ecstasy and divine connection.

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan is often hailed as the greatest qawwal of all time. His powerful voice and emotive renditions of Sufi poetry have captivated audiences worldwide. His contributions to qawwali music have not only preserved this ancient tradition but also brought it to the global stage, influencing musicians across various genres.

Sabri Brothers The Sabri Brothers, a legendary qawwali group from Pakistan, are known for their dynamic performances and soulful renditions of Sufi poetry. Their qawwalis, such as "Bhar Do Jholi Meri" and "Tajdar-e-Haram," are celebrated for their spiritual fervor and emotional depth.

Abida Parveen Abida Parveen, one of the most iconic female Sufi singers, has made significant contributions to the world of Sufi music. Her powerful and evocative voice has brought the poetry of Sufi saints to life, making her one of the most revered figures in the genre.

Recommended E-Books for Sufi and Sant Poetry

For those looking to delve deeper into the rich traditions of Sufi and Sant poetry, numerous e-books are available online. These digital collections provide a convenient way to explore the profound wisdom and spiritual insights of the Sufi and Bhakti poets.

"The Essential Rumi" by Coleman Barks This renowned translation of Rumi’s poetry by Coleman Barks captures the essence of Rumi’s mystical and spiritual insights. The book includes some of Rumi’s most famous poems, making it an essential read for anyone interested in Sufi literature.

"Songs of Kabir" by Rabindranath Tagore Rabindranath Tagore’s translation of Kabir’s dohas brings the profound wisdom of this Bhakti saint to a global audience. The book offers a selection of Kabir’s most insightful and thought-provoking verses, providing a glimpse into his spiritual teachings.

"The Conference of the Birds" by Attar of Nishapur This classic Persian poem, written by the Sufi poet Attar of Nishapur, is an allegorical journey of the soul towards enlightenment. The book, available in various translations, is a profound exploration of Sufi philosophy and spiritual quest.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cowling refers approvingly to Victorians "not falling for the Brahmo Samaj" and becoming lazy universalists, but what is the Brahmo Samaj?

it looks awfully like Unitarian Universalism for Hindus

The Brahmo Samaj was a monotheistic sect of Hinduism. The movement began through meetings of Bengalis in Calcutta in 1828. One of the leading figures was Ram Mohun Roy. This group was known as the Brahmo Sabha. In 1831, Roy visited England as a reforming ambassador and died there in 1833. He was buried in Bristol and his funeral sermon was conducted by Lant Carpenter, a Unitarian minister.

Debendranath Tagore, the father of Rabindranath Tagore, was a key member of the Brahmo Sabha. In 1843 he was involved in the creation of the Brahmo Samaj. Keshub Chunder Sen, a disciple of Tagore, joined the Samaj in 1857 but broke away in a formal schism in 1866. This schism was called the Brahmo Samaj of India. In 1870, Sen visited Britain and met with Mary Carpenter, the daughter of Lant Carpenter. Together they founded the National Indian Association, an organization designed to promote social reform in India and provide a meeting place for Indians and British people in Britain. Sen returned to India and created a major schism in the reforming society of the Brahmo Samaj when he married his 14-year-old daughter to the Maharaja of Cooch Behar, violating the Brahmo Marriage Act.

However, the Brahmo Samaj (in its various guises) continued to flourish in India and particularly Bengal. Rabindranath Tagore's Visva Bharati University was founded in 1921 as an expression of Brahmo universalism. The influence of Ram Mohun Roy and Keshub Chunder Sen in Britain could also be seen into the twentieth century. The cemetery where Roy was buried became a pilgrimage spot for Brahmos visiting the UK and the National Indian Association convened annual remembrances on the anniversary of Sen's death.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tagore Society Celebrates Varsha Mangal at Rabindra Bhawan

Annual monsoon tribute features dance and song performances by Tagore School of Arts The Tagore Society honors Rabindranath Tagore’s love for monsoon season with traditional Varsha Mangal event. JAMSHEDPUR – The Tagore Society organized its annual Varsha Mangal celebration at Rabindra Bhawan, paying homage to Rabindranath Tagore’s affinity for the monsoon season. Varsha Mangal, an annual…

#जनजीवन#Bengali cultural events#Jamshedpur art scene#Life#monsoon-themed play#Rabindra Bhawan event#Rabindranath Tagore monsoon tribute#seasonal artistic traditions#Tagore School of Arts performance#Tagore Society Jamshedpur#Tagore&039;s nature-inspired works#Varsha Mangal celebration

0 notes

Text

History of Bangladesh

1. Ancient Bengal (Before 1204 AD)

Prehistoric Bengal:

The history of Bengal dates back to ancient times, with archaeological evidence of human settlements dating to around 4000 BC. The early inhabitants were proto-Australoid, Tibeto-Burman, and Dravidian people. Bengal's history was largely shaped by the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta, which fostered trade and agriculture.

Vedic and Mauryan Period:

During the Vedic period, Bengal was known as "Vanga," and it is mentioned in early Sanskrit literature. Bengal was later integrated into the Mauryan Empire under Emperor Ashoka (3rd century BC), who promoted Buddhism across his vast empire. After the fall of the Mauryan Empire, Bengal was ruled by several local dynasties, including the Pundras and the Samatatas.

Gupta Empire and Bengal's Flourishing Culture:

During the Gupta period (320-550 AD), Bengal became an important cultural and political region. The Guptas, with their capital in Pataliputra, dominated much of northern India, including Bengal. The Buddhist Pala Dynasty (8th-12th century AD) succeeded the Guptas in Bengal, ushering in an era of prosperity. The Palas were great patrons of Buddhism and established universities like Nalanda and Vikramshila.

The Sena Dynasty:

The Hindu Sena dynasty (c. 1095-1204 AD) replaced the Palas. The Sena rulers were patrons of Brahmanical Hinduism and played a key role in shaping Bengali culture and society. They were the last major Hindu rulers of Bengal before the Muslim conquest.

2. Medieval Bengal (1204–1757 AD)

Early Muslim Conquests:

The Muslim conquest of Bengal began with the Turkish general Bakhtiyar Khalji’s invasion in 1204. Khalji’s forces defeated the Sena dynasty, and Bengal was gradually absorbed into the Delhi Sultanate. Over the next several centuries, Bengal became a key region in the Islamic world, ruled by various Muslim dynasties, including the Bengal Sultanate (1352–1576), which was known for its wealth and cultural diversity.

The Bengal Sultanate:

The Bengal Sultanate flourished during the 14th and 15th centuries as an independent Muslim kingdom. It was a center of trade, culture, and learning, connecting the Indian subcontinent with the broader Islamic world. The Sultans built architectural marvels, such as mosques and forts, many of which still stand today. The most prominent sultan, Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah, was a patron of Persian literature and established diplomatic relations with China.

Mughal Period (1576–1757):

The Mughals, under Emperor Akbar, annexed Bengal in 1576 after a protracted struggle. Bengal became one of the wealthiest provinces of the Mughal Empire due to its fertile lands and thriving trade. Dhaka was established as the capital of Bengal during the Mughal period and became a key center for commerce and craftsmanship, particularly in textiles. The Nawabs of Bengal, appointed by the Mughal emperors, effectively ruled the region, but they gradually gained autonomy.

3. Colonial Bengal (1757–1947)

British East India Company:

The turning point in Bengal’s history came with the Battle of Plassey in 1757, when British forces, led by Robert Clive, defeated Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah. This marked the beginning of British control over Bengal and eventually over much of India. Bengal became the first region to come under direct control of the British East India Company. The company’s exploitation of Bengal’s resources, combined with heavy taxation, led to economic distress and famines, such as the Bengal Famine of 1770.

Bengal Renaissance:

Despite British exploitation, the 19th century saw a cultural and intellectual awakening in Bengal, known as the Bengal Renaissance. Influential figures such as Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, and Rabindranath Tagore played crucial roles in reforming society, promoting education, and fighting against social injustices like Sati and child marriage. Bengal became the epicenter of Indian nationalism, with movements like the Young Bengal Movement and the Brahmo Samaj gaining prominence.

Partition of Bengal (1905) and Reversal (1911):

In 1905, the British colonial administration, under Lord Curzon, divided Bengal into two provinces: East Bengal and Assam, and West Bengal. This decision, seen as a tactic to divide and weaken the growing nationalist movement, sparked widespread protests and boycotts. The partition was eventually reversed in 1911, but the seeds of communal tension between Hindus and Muslims had already been sown.

The Independence Movement:

Bengal was at the forefront of the Indian independence movement. Leaders such as Subhas Chandra Bose, Surya Sen, and Chittaranjan Das played significant roles in resisting British rule. The Quit India Movement of 1942 also found strong support in Bengal. However, communal violence between Hindus and Muslims escalated during this period, especially during events like the Calcutta Killings of 1946.

4. The Partition and Pakistan Era (1947–1971)

Partition of Bengal (1947):

With the end of British rule in 1947, Bengal was once again divided, this time along religious lines. The western part became the Indian state of West Bengal, while the eastern part became East Pakistan, a part of the newly-formed state of Pakistan. Despite being geographically and culturally distant from West Pakistan, East Bengal (East Pakistan) became part of a nation dominated by West Pakistan.

Discontent in East Pakistan:

East Pakistan’s relationship with West Pakistan was strained from the beginning. The people of East Pakistan felt marginalized and exploited by the political and economic policies of the central government in West Pakistan. The imposition of Urdu as the sole national language in 1948 sparked the Bengali Language Movement, which culminated in the deaths of several students in Dhaka on February 21, 1952. This day is now commemorated as International Mother Language Day.

Economic disparities between the two wings of Pakistan further fueled discontent. East Pakistan, despite being the more populous and resource-rich region, received far less development aid and political representation. The situation worsened when the government of Pakistan, under President Ayub Khan, pursued policies that favored the western wing at the expense of the east.

Rise of Bengali Nationalism:

By the 1960s, Bengali nationalism was on the rise, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his party, the Awami League. The demand for greater autonomy for East Pakistan grew stronger. In 1966, Sheikh Mujib presented the Six-Point Movement, which called for significant political and economic autonomy for East Pakistan. The movement gained widespread support, especially after the devastating Bhola Cyclone in 1970, which killed hundreds of thousands of people and was met with an inadequate response from the central government.

5. The Bangladesh Liberation War (1971)

1970 General Election:

In the general elections of 1970, the Awami League, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, won a landslide victory in East Pakistan, securing 167 out of 169 seats allocated to the region in the National Assembly. This gave the Awami League an overall majority in the Pakistan National Assembly, but the ruling elite in West Pakistan, led by President Yahya Khan and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, refused to hand over power.

Operation Searchlight and the Declaration of Independence:

Tensions escalated, and on March 25, 1971, the Pakistan Army launched Operation Searchlight, a brutal crackdown on the people of East Pakistan. Thousands of Bengalis, including students, intellectuals, and political leaders, were killed. On the night of March 25, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman declared Bangladesh's independence, and the Liberation War began.

The Liberation War:

The war for Bangladesh’s independence lasted nine months, from March to December 1971. The Mukti Bahini (Liberation Army), comprised of Bengali military defectors and civilians, waged a guerrilla war against the Pakistan Army. India, under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, supported the Bengali cause and provided training and arms to the Mukti Bahini. In December 1971, following a full-scale war between India and Pakistan, the Pakistan Army surrendered in Dhaka, and Bangladesh was born as an independent nation on December 16, 1971.

6. Post-Independence Bangladesh (1971���Present)

Early Years and Sheikh Mujib’s Leadership:

Bangladesh emerged from the war of independence devastated, with millions of lives lost and much of its infrastructure destroyed. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, widely revered as the "Father of the Nation," became the first prime minister. His government focused on rebuilding the country, but the challenges were immense. Famine, economic instability, and political unrest plagued the early years of independence.

In 1975, Mujib introduced a one-party system through the BAKSAL (Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League) party, which led to dissatisfaction among many factions. On August 15, 1975, Sheikh Mujib and most of his family were assassinated in a military coup, plunging the country into political chaos.

Military Rule and Political Instability:

Following Mujib’s

#each with a hashtag:#-#AncientBengal#VangaKingdom#PalaDynasty#SenaDynasty#MuslimConquestOfBengal#BengalSultanate#MughalBengal#BattleOfPlassey#BritishColonialBengal#BengalRenaissance#PartitionOfBengal#BengaliLanguageMovement#SixPointMovement#BangladeshLiberationWar#IndependenceOfBangladesh#SheikhMujiburRahman#PostIndependenceBangladesh#MilitaryRuleInBangladesh#ModernBangladesh

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Devi

How many filmmakers can start with a comedy of manners and pivot to tragedy? Bergman? Ozu? Add Satyajit Ray to that list. His DEVI (1960, Criterion Channel, TCM, YouTube) starts as a trenchant commentary on Indian society, gender roles and religion. When her husband (Soumitra Chatterjee) goes off to Calcutta to study English, Dayamoyee (Sharmila Tagore) stays in his family’s palatial home to care for her father-in-law (Chhabi Biswas). It’s clear Biswas has it bad for the young woman, and when he dreams she’s the goddess Kali, it gives him an outlet for his forbidden libidinal energy. He starts worshipping her and, when she seems to save the life of a dying peasant boy, the whole countryside joins in. Ray is a director of details, and as Tagore’s cult grows, closeups reveal how trapped she feels in her new identity until it seems to eradicate her. It’s a fascinating view of how a traditional patriarchal society can erase women simply by idealizing them. Biswas’ adoration is not of Tagore, but rather an image in his head. He turns her into the perfect woman, a goddess, and in so doing destroys the beautiful, caring woman he couldn’t allow himself to see. He’s not the only one to ignore who she is. When Chatterjee learns of what’s going on, he comes home to save his wife, which starts by his telling her what she’s thinking. Biswas is often quite funny as the father-in-law, while Chatterjee, who’s living a bachelor’s life in Calcutta until he realizes he’s about to lose the wife he’s basically deserted, has some surprisingly moving moments. In the title role, the 16-year-old Tagore is exquisite, creating her character’s inner life even when she can’t speak or even move. Ustad Ali Akbar Khan contributed the evocative score.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

_*Experiences with Maha Periyava: Paul Brunton’s search for his Master*_

*Very Long but worth reading till the end.*

About the time of tiffin, that is, tea and biscuits, the servant announces a visitor. The latter proves to be a fellow member of the ink-stained fraternity, to wit, the writer Venkataramani. Several letters of introduction lie where I have thrown them, at the bottom of my trunk. I have no desire to use them. This is in response to a curious whim that it might be better to tempt whatever gods there be to do their best – or worst. However, I used one in Bombay, preparatory to beginning my quest, and I used another in Madras because I have been charged to deliver a personal message with it. And thus, this second note has brought Venkataramani to my door. He is a member of the Senate of Madras University, but he is better known as the author of talented essays and novels of village life. He is the first Hindu writer in Madras Presidency, who uses the medium of English, to be publicly presented with an inscribed ivory shield because of his services to literature.

He writes in a delicate style of such merit as to win high commendation from Rabindranath Tagore in India and from the late Lord Haldane in England. His prose is piled with beautiful metaphors, but his stories tell of the melancholy life of neglected villages.

As he enters the room I look at his tall, lean person, his small head with its tiny tuft of hair, his small chin and bespectacled eyes. They are the eyes of a thinker, an idealist and a poet combined. Yet the sorrows of suffering peasants are reflected in their sad irises. We soon find ourselves on several paths of common interest. After we have compared notes about most things, after we have contemptuously pulled politics to pieces and swung the censers of adoration before our favourite authors, I am suddenly impressed to reveal to him the real reason of my Indian visit. I tell him with perfect frankness what my object is; I ask him about the whereabouts of any real Yogis who possess demonstrable attainments; and I warn him that I am not especially interested in meeting dirt-besmeared ascetics or juggling faqueers.

He bows his head and then shakes it negatively. “India is no longer the land of such men. With the increasing materialism of our country, its wide degeneration on one hand and the impact of unspiritual Western culture on the other, the men you are seeking, the great masters, have all but disappeared. Yet I firmly believe that some exist in retirement, in lonely forests perhaps, but unless you devote a whole lifetime to the search, you will find them with the greatest difficulty. When my fellow Indians undertake such a quest as yours, they have to roam far and wide nowadays.

Then how much harder will it be for a European?”

“Then you hold out little hope?” I ask.

“Well, one cannot say. You may be fortunate.”

Something moves me to put a sudden question:

“Have you heard of a master who lives in the mountains of North Arcot?”

He shakes his head. Our talk wanders back to literary topics. I offer him a cigarette, but he excuses himself from smoking. I light one for myself and while I inhale the fragrant smoke of the Turkish weed, Venkataramani pours out his heart in passionate praise of the fast disappearing ideals of old Hindu culture. He makes reference to such ideas as simplicity of living, service of the community, leisurely existence and spiritual aims. He wants to lop off parasitic stupidities which grow on the body of Indian society. The biggest thing in his mind, however, is his vision of saving the half-million villages of India from becoming mere recruiting centres for the slums of large industrialized towns. Though this menace is more remote than real, his prophetic insight and memory of Western industrial history sees this as a certain result of present day

Trends. Venkataramani tells me that he was born in a family with a property near one of the oldest villages of South India, and he greatly lamented the cultural decay and material poverty into which village life had fallen. He loves to hatch out schemes for the betterment of the simple village folk, and he refuses to be happy whilst they are unhappy. I listen quietly in the attempt to understand his viewpoint. Finally, he rises to go and I watch his tall thin form disappear down the road.

Early next morning I am surprised to receive an unexpected visit from him. His carriage rushes hastily to the gate, for he fears that I might be out. “I received a message late last night that my greatest patron is staying for one day at Chingleput,” he bursts out. After he has recovered his breath, he continues: “His Holiness Shri Shankara Acharya of Kumbakonam is the Spiritual Head of South India. Millions of people revere him as one of God’s teachers. It happens that he has taken a great interest in me and has encouraged my literary career, and of course he is the one to whom I look for spiritual advice. I may now tell you what I refrained from mentioning yesterday. We regard him as a master of the highest spiritual attainment. But he is not a Yogi. He is the Primate of the Southern Hindu world, a true saint and great religious philosopher. Because he is fully aware of most of the spiritual currents of our time, and because of his own attainment, he has probably an exceptional knowledge of the real Yogis. He travels a good deal from village to village and from city to city, so that he is particularly well informed on such matters. Wherever he goes, the holy men come to him to pay their respects. He could probably give you some useful advice. Would you like to visit him?”

“That is extremely kind of you. I shall gladly go. How far is Chingleput?”

“Only thirty-five miles from here. But stay?”

”Yes?”

“I begin to doubt whether His Holiness would grant you an audience. Of course I shall do my utmost to persuade him.

But “”I am a European!” I finish the sentence for him. “I understand.”

” You will take the risk of a rebuff?” he asks, a little anxiously.

“Certainly. Let us go.”

After a light meal we set out for Chingleput. I ply my literary companion with questions about the man I hope to see this day. I learn that Shri Shankara lives a life of almost ascetic plainness as regards food and clothing, but the dignity of his high office requires him to move in regal panoply when travelling. He is followed then by a retinue of mounted elephants and camels, pundits and their pupils, heralds and camp followers generally. Wherever he goes he becomes the magnet for crowds of visitors from the surrounding localities. They come for spiritual, mental, physical and financial assistance. Thousands of rupees are daily laid at his feet by the rich, but because he has taken the vow of poverty, this income is applied to worthy purposes. He relieves the poor, assists education, repairs decaying temples and improves the condition of those artificial rain-fed pools which are so useful in the riverless tracts of South India. His mission, however, is primarily spiritual. At every stopping-place he endeavours to inspire the people to a deeper understanding of their heritage of Hinduism, as well as to elevate their hearts and minds. He usually gives a discourse at the local temple and then privately answers the multitude of querents who flock to him. I learn that Shri Shankara is the sixty-sixth bearer of the title in direct line of succession from the original Shankara. To get his office and power into the right perspective within my mind, I am forced to ask Venkataramani several questions about the founder of the line.

It appears that the first Shankara flourished over one thousand years ago, and that he was one of the greatest of the historical Brahmin sages. He might be described as a rational mystic, and as a philosopher of first rank. He found the Hinduism of his time in a disordered and decrepit state, with its spiritual vitality fast fading. It seems that he was born for a mission. From the age of eighteen he wandered throughout India on foot, arguing with the intelligentsia and the priests of every district through which he passed, teaching the doctrines of his own creation, and acquiring a considerable following. His intellect was so acute that, usually, he was more than a match for those he met. He was fortunate enough to be accepted and honoured as a prophet during his lifetime, and not after the life had flickered out of his throat. He was a man with many purposes. Although he championed the chief religion of his country, he strongly condemned the pernicious practices which had grown up under its cloak. He tried to bring people into the way of virtue and exposed the futility of mere reliance on ornate rituals, unaccompanied by personal effort. He broke the rules of caste by performing the obsequies at the death of his own mother, for which the priests excommunicated him. This fearless young man was a worthy successor to Buddha, the first famous caste breaker. In opposition to the priests he taught that every human being, irrespective of caste or colour, could attain to the grace of God and to knowledge of the highest Truth. He founded no special creed but held that every religion was a path to God, if sincerely held and followed into its mystic inwardness. He elaborated a complete and subtle system of philosophy in order to prove his points. He has left a large literary legacy, which is honoured in every city of sacred learning throughout the country. The pundits greatly treasure his philosophical and religious bequest, although they naturally quibble and quarrel over its meaning.

Shankara travelled throughout India wearing an ochre robe and carrying a pilgrim’s staff. As a clever piece of strategy, he established four great institutions at the four points of the compass. There was one at Badrinath in the North, at Puri in the East, and so on. The central headquarters, together with a temple and monastery, were established in the South, where he began his work. To this day the South has remained the holy of holies of Hinduism. From these institutions there would emerge, when the rainy seasons were over, trained bands of monks who travelled the country to carry Shankara’s message.

This remarkable man died at the early age of thirty-two, though one legend has it that he simply disappeared. The value of this information becomes apparent when I learn that his successor, whom I am to see this day, carries on the same work and the same teaching. In this connection, there exists a strange tradition. The first Shankara promised his disciples that he would still abide with them in spirit, and that he would accomplish this by the mysterious process of “overshadowing” his successors. A somewhat similar theory is attached to the office of the Grand Lama of Tibet. The predecessor in office, during his last dying moments, names the one worthy to follow him. The selected person is usually a lad of tender years, who is then taken in hand by the best teachers available and given a thorough training to fit him for his exalted post. His training is not only religious and intellectual, but also along the lines of higher Yoga and meditation practices. This training is then followed by a life of great activity in the service of his people. It is a singular fact that through all the many centuries this line has been established, not a single holder of the title has ever been known to have other than the highest and the most selfless character.

Venkataramani embellishes his narrative with stories of the remarkable gifts which Shri Shankara the Sixty-sixth possesses. There is an account of the miraculous healing of his own cousin. The latter has been crippled by rheumatism and confined to his bed for many years. Shri Shankara visits him, touches his body, and within three hours the invalid is so far better that he gets out of bed; soon, he is completely cured. There is the further assertion that His Holiness is credited with the power of reading the thoughts of other persons; at any rate, Venkataramani fully believes this to be true.

We enter Chingleput through a palm-fringed highway and find it a tangle of whitewashed houses, huddled red roofs and narrow lanes. We get down and walk into the centre of the city, where large crowds are gathered together. I am taken into a house where a group of secretaries are busily engaged handling the huge correspondence which follows His Holiness from his headquarters at Kumbakonam. I wait in a chairless anteroom while Venkataramani sends one of the secretaries with a message to Shri Shankara. More than half an hour passes before the man returns with the reply that the audience I seek cannot be granted. His Holiness does not see his way to receiving a European; moreover, there are two hundred people waiting for interviews already. Many persons have been staying in the town overnight in order to secure their interviews. The secretary is profuse in his apologies.

I philosophically accept the situation, but Venkataramani says that he will try to get into the presence of His Holiness as a privileged friend, and then plead my cause. Several members of the crowd murmur unpleasantly when they become aware of his intention to pass into the coveted house out of his turn. After much talk and babbling explanations, hewins through. He returns eventually, smiling and victorious.

“His Holiness will make a special exception in your case. He will see you in about one hour’s time.”

I fill the time with some idle wandering in the picturesque lanes which run down to the chief temple. I meet some servants who are leading a train of grey elephants and big buffbrown camels to a drinking-place. Someone points out to me the magnificent animal which carries the Spiritual Head of South India on his travels. He rides in regal fashion, borne aloft in an opulent howdah on the back of a tall elephant. It is finely covered with ornate trappings, rich cloths and gold embroideries. I watch the dignified old creature step forward along the street. Its trunk coils up and comes down again as it passes.

Remembering the time-worn custom which requires one to bring a little offering of fruits, flowers or sweetmeats whenvisiting a spiritual personage, I procure a gift to place before my august host. Oranges and flowers are the only things in sight and I collect as much as I can conveniently carry. In the crowd which presses outside His Holiness’s temporary residence, I forget another important custom. “Remove your shoes,” Venkataramani reminds me promptly. I take them off and leave them out in the street, hoping that they will still be there when I return!

We pass through a tiny doorway and enter a bare anteroom. At the far end there is a dimly lit enclosure, where I behold a short figure standing in the shadows. I approach closer to him, put down my little offering and bow low in salutation. There is an artistic value in this ceremony which greatly appeals to me, apart from its necessity as an expression of respect and as a harmless courtesy. I know well that Shri Shankara is no Pope, for there is no such thing in Hinduism, but he is teacher and inspirer of a religious flock of vast dimensions. The whole of South India bows to his tutelage.

I look at him in silence. This short man is clad in the ochrecoloured robe of a monk and leans his weight on a friar’s staff. I have been told that he is on the right side of forty, hence I am surprised to find his hair quite grey. His noble face, pictured in grey and brown, takes an honoured place in the long portrait gallery of my memory. That elusive element which the French aptly term spirituel is present in this face. His expression is modest and mild, the large dark eyes being extraordinarily tranquil and beautiful. The nose is short, straight and classically regular. There is a rugged little beard on his chin, and the gravity of his mouth is most noticeable. Such a face might have belonged to one of the saints who graced the Christian Church during the Middle Ages, except that this one possesses the added quality of intellectuality.

I suppose we of the practical West would say that he has the eyes of a dreamer. Somehow, I feel in an inexplicable way that there is something more than mere dreams behind those heavy lids.

“Your Holiness has been very kind to receive me,” I remark, by way of introduction. He turns to my companion, the writer, and says something in the vernacular. I guess its meaning correctly.

“His Holiness understands your English, but he is too afraid that you will not understand his own. So he prefers to have me translate his answers,” says Venkataramani.

I shall sweep through the earlier phases of this interview, because they are more concerned with myself than with this Hindu Primate. He asks about my personal experiences in the country; he is very interested in ascertaining the exact impressions which Indian people and institutions make upon a foreigner. I give him my candid impressions, mixing praise and criticism freely and frankly. The conversation then flows into wider channels and I am much surprised to find that he regularly reads English newspapers, and that he is well informed upon current affairs in the outside world. Indeed, he is not unaware of what the latest noise at Westminster is about, and he knows also through what painful travail the troublous infant of democracy is passing in Europe.

I remember Venkataramani’s firm belief that Shri Shankara possesses prophetic insight. It touches my fancy to press for some opinion about the world’s future.

“When do you think that the political and economic conditions everywhere will begin to improve?”

“A change for the better is not easy to come by quickly,” he replies. ” It is a process which must needs take some time. How can things improve when the nations spend more each year on the weapons of death?”

“There is nevertheless much talk of disarmament to-day. Does that count?”

“If you scrap your battleships and let your cannons rust that will not stop war. People will continue to fight, even if they have to use sticks!”

“But what can be done to help matters?”

“Nothing but spiritual understanding between one nation and another, and between rich and poor, will produce goodwill and thus bring real peace and prosperity.”

“That seems far off. Our outlook is hardly cheerful, then?”

His Holiness rests his arm a little more heavily upon his staff.

“There is still God,” he remarks gently.

” If there is, He seems very far away,” I boldly protest.

“God has nothing but love towards mankind,” comes the soft answer.

“Judging by the unhappiness and wretchedness which afflict the world to-day, He has nothing but indifference,”

I break out impulsively, unable to keep the bitter force of irony out of my voice. His Holiness looks at me strangely. Immediately I regret my hasty words.

“The eyes of a patient man see deeper. God will use human instruments to adjust matters at the appointed hour. The turmoil among nations, the moral wickedness among people and the suffering of miserable millions will provoke, as a reaction, some great divinely inspired man to come to the rescue. In this sense, every century has its own saviour. The process works like a law of physics. The greater the wretchedness caused by spiritual ignorance, materialism, the greater will be the man who will arise to help the world.”

“Then do you expect someone to arise in our time, too?”

” In our century,” he corrects. “Assuredly. The need of the world is so great and its spiritual darkness is so thick, that an inspired man of God will surely arise.”

“Is it your opinion, then, that men are becoming more degraded?” I query.

“No, I do not think so,” he replied tolerantly. “There is an indwelling divine soul in man which, in the end, must bring him back to God.”

“But there are ruffians in our Western cities who behave as though there were indwelling demons in them,” I counter, thinking of the modern gangster.

“Do not blame people so much as the environments into which they are born. Their surroundings and circumstances force them to become worse than they really are. That is true of both the East and West. Society must be brought into tune with a higher note. Materialism must be balanced by idealism; there is no other real cure for the world’s difficulties. The troubles into which countries are everywhere being plunged are really the agonies which will force this change, just as failure is frequently a sign-post pointing to another road.”

“You would like people to introduce spiritual principles into their worldly dealings, then?”

“Quite so. It is not impracticable, because it is the only way to bring about results which will satisfy everyone in the end, and which will not speedily disappear. And if there were more men who had found spiritual light in the world, it would spread more quickly. India, to its honour, supports and respects its spiritual men, though less so than in former times. If all the world were to do the same, and to take its guidance from men of spiritual vision, then all the world would soon find peace and grow prosperous.”

Our conversation trails on. I am quick to notice that Shri Shankara does not decry the West in order to exalt the East, as so many in his land do. He admits that each half of the globe possesses its own set of virtues and vices, and that in this way they are roughly equal! He hopes that a wiser generation will fuse the best points of Asiatic and European civilizations into a higher and balanced social scheme.

I drop the subject and ask permission for some personal questions. It is granted without difficulty.

“How long has Your Holiness held this title?”

“Since 1907. At that time I was only twelve years old. Four years after my appointment I retired to a village on the banks of the Cauvery, where I gave myself up to meditation and study for three years. Then only did my public work begin.”

“You rarely remain at your headquarters in Kumbakonam I take it?”

“The reason for that is that I was invited by the Maharajah of Nepal in 1918 to be his guest for a while. I accepted and since then have been travelling slowly towards his state in the far north. But see! – during all those years I have not been able to advance more than a few hundred miles, because the tradition of my office requires that I stay in every village and town which I pass on the route or which invites me, if it is not too far off. I must give a spiritual discourse in the local temple and some teaching to the inhabitants.”

I broach the matter of my quest and His Holiness questions me about the different Yogis or holy men I have so far met. After that, I frankly tell him: “I would like to meet someone who has high attainments in Yoga and can give some sort of proof or demonstration of them. There are many of your holy men who can only give one more talk when they are asked for this proof. Am I asking too much?”

The tranquil eyes meet mine. There is a pause for a whole minute. His Holiness fingers his beard.

” If you are seeking initiation into real Yoga of the higher kind, then you are not seeking too much. Your earnestness will help you, while I can perceive the strength of your determination; but a light is beginning to awaken within you which will guide you to what you want, without doubt.”

I am not sure whether I correctly understand him. “So far I have depended on myself for guidance. Even some of your ancient sages say that there is no other god than that which is within ourselves,” I hazard.

And the answer swiftly comes: “God is everywhere. How can one limit Him to one’s own self? He supports the entire universe.”

I feel that I am getting out of my depth and immediately turn the talk away from this semi-theological strain.

“What is the most practical course for me to take?”

“Go on with your travels. When you have finished them, think of the various Yogis and holy men you have met; then pick out the one who makes most appeal to you. Return to him, and he will surely bestow his initiation upon you.”

I look at his calm profile and admire its singular serenity.

“But suppose, Your Holiness, that none of them makes sufficient appeal to me. What then? ”

“In that case you will have to go on alone until God Himself initiates you. Practise meditation regularly; contemplate the higher things with love in your heart; think often of the soul and that will help to bring you to it. The best time to practise is the hour of waking; the next best time is the hour of twilight. The world is calmer at those times and will disturb your meditations less.”

He gazes benevolently at me. I begin to envy the saintly peace which dwells on his bearded face. Surely, his heart has never known the devastating upheavals which have scarred mine? I am stirred to ask him impulsively:

”If I fail, may I then turn to you for assistance?”

Shri Shankara gently shakes his head. “I am at the head of a public institution, a man whose time no longer belongs to himself. My activities demand almost all my time. For years I have spent only three hours in sleep each night. How can I take personal pupils? You must find a master who devotes his time to them.”

“But I am told that real masters are rare, and that a European is unlikely to find them.”

He nods his assent to my statement, but adds:

“Truth exists. It can be found.”

“Can you not direct me to such a master, one who you know is competent to give me proofs of the reality of higher Yoga?”

His Holiness does not reply till after an interval of protracted silence.