Text

Some of the elements in Viktor's arc resemble tropes originated during the Red Scare - a technological emotionless enemy, the framing of collectivist ideals as a hive mind or shared consciousness, and the forceful loss of identity. Viktor takes away people's emotions when he heals them and they join a stream of consciousness connected to him, then when he evolves them they become identical artificial forms with no trace of their former selves.

The evolution from McCarthyst propaganda to modern self produced animation is quite long, but the roots of these tropes do speak about the current landscape of anti-capitalism in popular media.

50s sci-fi exploited the fears of Soviet infiltration and nuclear disaster, so there was quite a trend of alien invasion movies. The trope of the technological and emotionless enemy took shape here, with aliens that had frightening (I guess?) forms and were set on destroying the earth. They had no reasonable motivation, just wanted the earth and humanity gone mostly, which mirrored a bit how Soviets were perceived - just The Threat that exists to attack USAmerican people.

The fear of ideological indoctrination into communism (which just stood for A Thing Other Than USAmerican Values) was explored in movies like Invasion of the Body Snatchers, where aliens take over by creating replicas of each human and replacing them when they went to sleep. The takeover is sudden, while the person is in a vulnerable state, and the protagonist must stay in a vigilante state to avoid possession.

This loss of self and identity —of humanity, which plays a major role in sci-fi— was enhanced in the 80s in Star Trek: Next Generation with the introduction of the Borg, a transhumanist species that alters their own bodies since birth where each member is a part of a larger collective consciousness.

The Borg are a threat that won't listen to reason or compassion, but rather than being just an agent of chaos they simply act on logic: their goal is to assimilate every species they deem worthy to absorb their knowledge on technology, so they can enhance themselves as a unity further. They destroy to grow, which has at least more complexity than the aliens of old.

While anti-communist propaganda of the prior decades equated collectivist ideology to conformism and submission, depicting it as a loss of emotions and identity like in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Star Trek took this trope several creative steps ahead and made the Borg become assimilated to the collective so early in their life they do not have a sense of self, always talking in plural pronouns. When separated from their companions, the collective, they still refer to themselves as ‘we’ and fail to understand the concept of an individual.

Sci-fi moved on from the immediate threat of the Cold War, delving into more universal and philosophical themes of identity, but the enemy created in the Red Scare continued to be used for these ideas. The Borg, complex and creative as they are, still mirror the perception of the Soviet Union as an expanding empire whose people have been brainwashed into pursuing collectivist ideals and technological development (this one courtesy of the race with the US).

Sci-fi notoriously provides ground to project society's fears and anxieties, which are ever changing with the years, and the Soviet Union was dissolved long ago, yet the monsters of fear and anxiety sometimes go back to wearing the costume of the Soviet caricature.

The Matrix was released in 1999, one year after Dark City. Both contain similar themes of autonomy, with a protagonist that must fight his way out of a fake world designed by an echo of anti-communist propaganda —in The Matrix it's robots who take over the digital avatars of people at will and share a collective consciousness, in Dark City it's aliens that take over the corpses of people and share a collective consciousness.

However, neither of these movies really has an intent to follow the footsteps of its predecessors regarding these tropes, they just use the costumes. Freedom and self determination do play into the propaganda as a contrast to the conformity and submission of The Threat, but it is entirely possible to explore them via these tropes without falling into ideological warfare.

Which is not the case of Legend of Korra which, while not strictly sci-fi, it does have elements of steampunk. And the use of the tropes in Korra feels almost like an afterthought, like they weren't even needed from how explicit the anti-communist message is. In the year of our lord 2012.

What the series does mainly is establish socialists as frauds and adherents as fools. Amon has a personal grudge against benders that he disguises as a social problem, the text utilizes the idea that socialists make up or exaggerate oppression in order to gain power, and there's no real inequality to begin with. He takes away people's bending abilities, leaving them as a shell of their former selves, quite like the identity loss in Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Now where does Arcane stand in all this?

Viktor’s motivations are legitimized, the inequality between the two cities is sufficiently explored. This monster wears the costume, but it's humanized.

It's a huge jump from Korra’s ridiculous propaganda, but I still have an issue with it: it's condescending.

Collectivism has a history of negative portrayals in USAmerican media, is it such a jump forward if the motivations of such apparent monster are legitimized, yet the outcome is the same? It's Viktor’s desire to eliminate the suffering created by Piltover’s oppression that causes the final destruction, not Piltover’s pursuit of progress or increasingly fascist policies.

This of course doesn't antagonize the noble cause of Viktor's motivations, which is nice all things considered, since Korra has proved it can be worse, but it does warn against disturbing the status quo. If you try to make things better, you will fail, you will make things worse; the current state of things is the only choice, it's safer and realistic, and though your intentions are good, a better world than what we already have is impossible.

Collectivist values don’t turn into a monster in real life, that's just something USAmerican propaganda made up, but the fear that it does remains. It's the same fear that was used to put a dictator in my country, so of course I have my own personal grudge against it, hence the post.

#wrote 4k words and then i got mad and wrote this#the essay might see the light of day one day but for now#this ramble#arcane#viktor

1 note

·

View note

Text

I'll probably use this blog to post commentary and analysis of other media

I'll also try to limit my ramblings to post coherent analysis instead of dropping thoughts randomly

1 note

·

View note

Text

Decoding Inazuma: What is Eternity?

(originally posted May 2023 on hoyolab)

Yoimiya mentions in her second story quest that her ancestor came up with the idea for fireworks as a means to represent the past and the future, but this isn’t a new development in the story: it is precisely the theme that her first quest revolved around and one of the most important concepts in the narrative of the Inazuma chapter.

The eternity around transience is the core of Makoto’s ideals, and what Ei comes to terms with at the end of her arc. Thus, Naganohara Fireworks and Yoimiya as a character serve as the first element of insight into the narrative of Inazuma.

The Eternal Connection of Fireworks

In Carassius Auratus act I, we learn that people use fireworks to commemorate special events in their lives, such as the old couple who set them off on the anniversary of their wedding; or to remember old times like the childhood friends who reunited every once in a while to catch up; or to keep promises to each other, like the couple who had been separated when one escaped Inazuma illegally on a boat.

These fireworks were always the same kind, because Naganohara Fireworks gives their customers a special paper slip with their recipe. So no matter how long has passed, as long as they have the paper slip, a member of the Naganohara family of any generation will be able to replicate the exact same firework, and the intentions they were made for from the past can be remembered.

Yoimiya’s character as a whole is used to appreciate the worth and celebrating the transience of human life. She likes to talk to her neighbors more than anything else about their mundane lives, and even works late into the night to provide the fireworks they request. It isn’t precisely people whose lives change the world or belong to the upper class, just regular citizens and their regular joys and sorrows.

Fireworks are used to represent not just the beauty of transience, but also as a symbol of the eternal connection that gives meaning and worth to human life across time. A single person’s life might be a small fragment of history, but ideas —values, culture, purpose, dreams— are passed through each one of them, and they can only endure the passage of time when carried collectively through the generations. This is symbolized through the paper slips provided by Naganohara Fireworks.

Transience is Part of Eternity

Makoto’s ideal of transience wasn’t a superficial preference for temporary existence. She believed transience was part of eternity, of making insignificant human life part of something bigger, long-lasting, something that could outlive mortality.

This is further emphasized in the climax of the Inazuma archon quest, when Kazuha faces the Raiden Shogun’s Musou no Hitotachi. His friend’s wish was to witness and survive its strike, what the motivations for this ambition are we’re not told, but Kazuha realizes it himself beyond his friend’s death. It is at this moment precisely that the deactivated vision rekindles once more, proving that wishes can survive human mortality as long as they’re carried by the living.

(We can still call it the power of friendship for sentimental reasons, it’s okay)

Makoto didn’t place transience above eternity, one is just a means to the other. The twin gods always shared the same goal of eternity for their nation, the difference is Ei was blinded by fear and couldn’t understand her sister’s approach, but they never held opposing views. They both wanted the same for their people: to survive and remain.

But why is eternity so important in Inazuma?

Because Inazuma is based on Japan, and eternity is a fundamental belief in Shinto, the native religion of Japanese people:

Japanese mythology speaks of an eternity of history in the divine edict of Amaterasu. In its view of history, Shintō adheres to the cyclical approach, according to which there is a constant recurrence of historical patterns. Shintō does not have the concept of the “last day”: there is no end of the world or of history. One of the divine edicts of Amaterasu says:

"This Reed-plain-1,500-autumns-fair-rice-ear Land is the region which my descendants shall be lords of. Do thou, my August Grandchild, proceed thither and govern it. Go! and may prosperity attend thy dynasty, and may it, like Heaven and Earth, endure forever."

Modern Shintōists interpret this edict as revealing the eternal development of history as well as the eternity of the dynasty. From the viewpoint of finite individuals, Shintōists also stress naka-ima (“middle present”), which repeatedly appears in the Imperial edicts of the 8th century. According to this point of view, the present moment is the very center in the middle of all conceivable times. In order to participate directly in the eternal development of the world, it is required of Shintōists to live fully each moment of life, making it as worthy as possible.

Similarly, another core aspect of Shinto beliefs is the concept of “Makoto” (yes, like Ei’s sister):

At the core of Shintō are beliefs in the mysterious creating and harmonizing power of kami and in the truthful way or will (makoto) of kami. The nature of kami cannot be fully explained in words, because kami transcends the cognitive faculty of humans.

The kami also reveals makoto to people and guides them to live in accordance with it. In traditional Japanese thought, truth manifests itself in empirical existence and undergoes transformation in infinite varieties in time and space. Makoto is not an abstract ideology. It can be recognized every moment in every individual thing in the encounter between humans and kami.

Kami (Shinto gods) don’t need to be worshiped the way traditional gods do, as performing tasks of regular life is a form of worship in itself, and the truth of kami manifests in it. It seems like a very chill religion.

Shinto doesn’t have a list of ethical rules like conventional religions either, but the concept of Makoto (“truth” or “sincerity”) can be found at the heart of its ethical values. A person who behaves truthfully therefore acts ethically.

This is partly what is meant by the phrase kannagara-no-michi which, in the ethical context, refers to the idea that virtue is inseparable from the rest of life, especially life lived in harmony with the natural world (enlivened by kami). Beauty, truth, goodness, morality - these are all connected, inseparable from each other. Those who live life with the perspective outlined above - with an aesthetic sensitivity, an emotional sensibility toward the world, and with a sincere heart will behave morally almost naturally. List and rules are more important for training animals than for cultivating morality in humans, according to this view.

Having said this, purity rituals are common across Shinto practice, which points to the need for purity in one's heart. This purity of heart is a natural companion to makoto. Often, these activities are done at a shrine, and they symbolize the inner purity necessary for a truly human and spiritual life.

The Grand Narukami Shrine is inspired by these, where Yae Miko performs her duties as the Guuji (chief priestess) that Kitsune Saiguu entrusted to her before passing away.

As a re-interpretation of Shinto within the world building of the game, the beliefs of the kitsune Guuji and Raiden Makoto are not meant to parallel exactly those of the real life religion, but the elements are used to shape up a cohesive narrative in the story.

Yae acknowledges she has more in common with Makoto, as the characters who embody the beliefs and practices of Shinto, and it is her who schemes her way into Ei’s Plane of Euthymia to talk her into finding another path towards this eternity that Makoto wanted.

So why does Ei, the archon of the nation, struggle to follow the eternity her sister and Yae Miko understood so well?

From the names in her kit, to her visual motifs, to her lore, Ei’s character is filled with Buddhist references, portraying her with bodhisattva imagery —an entity who has attained enlightenment but has delayed their entry into paradise to help those still suffering in the mortal world. And the original name for the Plane of Euthymia ("Pure Land of One Mind") is a reference to an alternative branch of Mahayana Buddhism that spread to Japan.

Buddhism stands on a completely different set of philosophies to the traditions of Shinto. For instance, one of its main beliefs is that people are trapped in a cycle (samsara) of suffering (dukkha) through multiple reincarnations, and the only way to be released from this illusory world is by following Buddhist doctrines. Life in the mortal world should be ideally finite, it must have an end to cease all suffering, yet Shinto believes in an eternal history that strives to focus on the present moment.

Despite how incompatible they look from the outside, both religions have coexisted in Japan for centuries, and they’re practiced simultaneously by regular people.

From this perspective, it is not odd that Ei would struggle to achieve a goal that is impossible to grasp through the Buddhist lens her character is inspired on.

What we know as “ambition” in the world building of the game (the trigger for obtaining a vision) is originally called “wish” in Chinese text. In Buddhism, there are two types of desire: Tanha and Chanda.

Tanha can be translated as “craving” and it’s a type of desire that on principle causes suffering. If you crave something, this in itself is painful when it cannot be fulfilled; but if it is satisfied, then it is only a matter of time for the good feeling it produces to eventually fade and leave pain behind.

Taṇhā is the key origin of Dukkha. It reflects a mental state of craving. Greater the craving, more is the frustration because the world is always changing and innately unsatisfactory; craving also brings about pain through conflict and quarrels between individuals, which are all a state of Dukkha. It is such taṇhā that leads to rebirth and endless Samsara.

This seems to be the origin of Ei’s need to quell desires (including her own) in order to hinder her people’s progress.

Ei realized early on, in her role of kagemusha and military general, that seeking victory against enemies also brought devastation upon herself and those she and Inazuma cared about. Her sister is who led the nation before she passed away, and Ei’s only contributions as the other half of the archon title were in the battlefield.

Craving for progress, after all, only brings suffering: the fleeting memory of a victory is overshadowed by the losses that follow.

When lightning flashes, it casts a shadow; and her name means shadow. Her existence was defined by this shadow of loss under the victories of progress.

As she herself puts it:

With my blade I purged all obstacles to progress

And yet... Something was lost with each step forward

In the end, I even lost her

I've seen a nation strive forward, and lose everything to the Heavenly Principles

Khaenri’ah was a godless nation, and their demise is understood to be a consequence of their own actions, their own ambition to progress beyond the boundaries of the Heavenly Principles (whatever those are), so of course she grew afraid of what her people might become should they venture in the same direction. And the only way to keep them from meeting the same fate was to ensure her own permanence as a god, hence why she got rid of her physical form to preserve her consciousness in a perpetual meditative state in order to avoid the effects of erosion, and why she made an indestructible puppet that would never leave her nation defenseless.

In the archon quest we see Kujou Takayuki fall prey of his own desires for divine power —that of the Raiden Shogun’s martial prowess that folk tales praise but whose consequences Ei herself feels burdened by— and this is a narrative that repeats over and over again through Teyvat’s history. Watatsumi people, for instance, come from a nation that abused their political positions and manipulated their people through false faith to the artificial sun and the helpless ruling of the Sun Children.

Humans are prone to cause their own demise by indulging in this form of "tanha”, and Ei wanted to protect Inazuma from its dangers.

She never had trouble accepting her sister's death, it is because she understood the cycle of life and death so well that she grew fearful of losing what remained: Inazuma. People don't know Makoto existed, so her only legacy and proof of existence is the nation they both raised. As such, Ei vowed to protect it indefinitely by condemning herself to an eternity of stasis inside the Plane of Euthymia.

The Better Path Towards Eternity

Ei’s commitment to this eternity, this indefinite protection of her nation, never wavered until she met the traveler during the archon quest.

She called him a threat to eternity, therefore, what she saw in our protagonist was a symbol of hope, a faint wish for her nation to progress without succumbing to the Heavenly Principles like Khaenri’ah.

But desires, even in the form of hope, are something she was depriving herself (and her nation) from.

Both times the traveler entered the Plane of Euthymia were right before the Shogun puppet (who is in charge of enforcing this vow to eternity and perpetual sacrifice) struck him with the Musou no Hitotachi, so what saved them was was rather Ei clinging to this hope. Both times she fights this metaphorical hope as well, the first one she wins, and this hope is rejected; and the second (where traveler is aided by Yae Miko) she admits defeat after witnessing the meteor shower of her people's wishes, because she’s accepted the possibility of a future where Inazuma can pursuit their ambitions freely and she doesn’t have to condemn herself to eternal sacrifice.

According to Buddhist beliefs, Tanha (the craving) is the type of desire that causes suffering, but the other form of desire, Chanda, is a path towards salvation:

Sometimes taṇhā is translated as “desire,” but that gives rise to some crucial misinterpretations with reference to the way of Liberation. Some form of desire is essential in order to aspire to, and persist in, cultivating the path out of Dukkha.

Desire as an eagerness to offer, to commit, to apply oneself to meditation, is called Chanda. It’s a psychological “yes,” a choice, not a pathology. In fact, you could summarize Dhamma training as the transformation of taṇhā into Chanda. It’s a process whereby we guide volition, grab and hold on to the steering wheel, and travel with clarity toward our deeper well-being.

So we’re not trying to get rid of desire (which would take another kind of desire, wouldn’t it). Instead, we are trying to transmute it, take it out of the shadow of gratification and need, and use its aspiration and vigor to bring us into light and clarity.

Makoto believed that eternity could be achieved by guiding the collective dreams of her nation into the right path, what matters is not physical survival or individual desires, but the collective force pushing for progress. And, in this sense, dreams could be understood as its own type of Chanda (within the narrative of the chapter, not the world building) that Ei came to terms with in her second story quest.

The losses Inazuma suffered —the shadow— are not meant to be grieved, but honored. They were all sacrifices intended for the survival and protection of the nation and its ideals and dreams, such as that of the soldiers who fought during the cataclysm, that of Kitsune Saiguu or the Tengu General, and that of Makoto as well.

Kazuha and his friend can be interpreted as an alternative exploration of this theme: Kazuha grieved his death and failed to understand the motivations behind his actions, but when he faces the Musou No Hitotachi himself he's able to comprehend and carry his friend's wishes as his own. After this, he is at peace and able to move on.

After all, life is akin to a firework that only lasts a couple of seconds, but what they symbolize and the ideas they preserve are what matters. This is the eternity of the nation of thunder.

Whenever I think about the Inazuma chapter, I'm always reminded of this anecdote about the Gold Pavilion Temple that, in a way, summarizes what Makoto believed:

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sumeru's war on Nietzsche (part 1)

One of the main themes of the Sumeru chapter is the victory of altruistic values over egoism, specifically the egoism in Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophy.

I want to point out these connections so we can agree from the getgo on Nietzsche’s presence in the chapter:

Kaveh defeats nihilism in Parade of Providence, and the defeat of nihilism is one of the main goals of Nietzsche's philosophy

Achievements in the Khvaena of Good and Evil quest are named after Nietzsche quotes

Sumeru is mostly inspired by India, Iran and Egypt, and Nietzsche had a bone to pick with the philosophical influence of all three in the west

The themes of egoism and altruism are explored through the work of western philosophers and the philosophy of eastern religions, following the real life historical interrelation of both. And because the outcome of this confrontation favors altruism more, I also think it can be interpreted as a rejection of western values of individualism as a whole.

Nietzsche has the leading role for this analysis for clarity's sake (or else it'd end up in 15k words) but the philosophical material used in the region is vast and varied.

Egyptian influence

Nietzsche blamed Egypt for influencing Greek philosophers like Plato (public enemy #1 of Nietzsche) in his conception of goodness. Philosophers of ancient Greece would go on to influence western philosophy and institutions.

Nietzsche thought that developing the idea of objective goodness which one should aspire to and be governed by is where the ancient Greeks went wrong as a society, disrupting the balance between the rational values of the god Apollo and the frenzy of the god Dionysus that made ancient Greece an ideal society in Nietzsche's eyes. The clash of order and chaos is what made Greek culture rich in his opinion, so introducing a code of ethics ruined the dichotomy.

This concern with goodness was of course Plato's fault, who most likely was influenced by the Egyptian concept of Ma'at. Ma'at can basically be understood as a moral principle that guided both Egyptian society in its religious beliefs and its institutions.

In Genshin Cyno’s character is inspired by the god Anubis and one of his main motifs is the scales, his personal drive is also the pursuit of justice and order. This is likely because in Egyptian mythology Anubis weighs the hearts of the deceased against the feather of Ma'at.

So here we have the character inspired by Egyptian culture who personifies the ancient concept of morality that Nietzsche blamed for ruining a society he considered advanced.

Indian influence

The philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer was initially Nietzsche's role model, but he'd later become his biggest critic due to the ideas promoted by his philosophical system.

Schopenhauer borrowed elements from dharmic religions (Buddhism and Hinduism) to construct his ideas, mainly the concept of Brahma (a universal consciousness which originated all creation and it therefore presents the world as a unity) and the concept of desires as the basis of suffering (therefore desires have to be suppressed).

Nietzsche considered this philosophical approach to be pessimistic, arguing that it easily led into nihilism. He thought similarly about Buddhism (although he held it in higher regard than Christianity) for being a religion that denies the self and devalues the world, only considering it a transitory illusion that had to be escaped. Nietzsche aimed for the complete opposite: giving value to the world as it was and indulging in one's own individuality, independent from collective constraints.

In Genshin I think the concept of Brahma is close to the plot of the sovereign dragon Apep, who creates life that later goes back to it in Nahida's second story quest. Buddhist philosophy is covered in Wanderer's arc, which I analysed here.

Iranian influence

Iran and India share common ancestors, so their religious practices also have common traditions (such as the worship of nature), hence why they largely make up most of Sumeru’s inspiration. The ancient religion of Iran is called Zoroastrianism, things like the Akademiya darshans and the House of Daena are named after its religious principles, as well as the overall region where the quest Khvaena of Good and Evil takes place.

Zoroastrianism was founded by Zoroaster, who conceptualized the world as a conflict between good (originated by the creator god Ahura Mazda) and evil (influenced by the entity Ahriman) where humans have free will to choose between the two.

This cosmology would later influence the abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam) and, in Nietzsche's view, originate the western perception of morality he was critical of.

He used the prophet Zoroaster (known in Germany as Zarathustra) as his own character in the book Thus Spoke Zarathustra to voice his ideas of a new kind of man that could overcome this morality that Europe had submitted to under the authority of Christianity. This way, since Zoroaster was the one to introduce morality to the western world, so would he be the one to denounce it.

Historical context

The philosophical confrontation between egoism and altruism began in the aftermath of the French revolution, when European countries formed into republics. The threats of democracy, liberalism and socialism loomed over the aristocratic class and the societal status quo, which produced reactionary responses in the shape of individualism and egoism: the exaltation of the individual over the collective majority.

Nietzsche himself took part in (and built his ideas around) this reactionary response, he argued that the purpose of society was producing culture, which could only be achieved by the subjugation of one class to support the elites who could produce the art that the inferior class was supposedly incapable of producing. He denounced democracy, the egalitarian cause of liberalism and the class equality of socialism of attempting against this purpose, and he used the altruistic values of religion as a scapegoat that collectively addressed the three.

Nietzsche's philosophy

In this sense, Christianity was a method of control to suppress the individual from the basis of resentment —here's where the master and slave morality dichotomy he authored comes from: the subjugated class, in his theory, motivated by feelings of resentment and powerlessness against the elites, would develop values of humility, altruism and collectivism in order to morally place themselves above the “masters”.

For Nietzsche, this dominating morality was limiting and produced no worthy culture or arts, and without a purpose society was doomed to fall into nihilism (a state of being devoid of meaning). He identified the pessimistic approach of eastern religion (like the influence they had on Schopenhauer) and the slave morality of western religion as the culprits of nihilism, as well as the conformity of the “last man” (as he called it) who didn't aspire to anything beyond what was imposed on him.

Nietzsche's main existential problem with religion was the devaluation of the world and the individual, treating both as transitory towards a “beyond” where value was placed instead (Nirvana in Buddhism, Heaven in Christianity, etc), and he sought to return this value to life through the concept of the ubermensch (“overman” or “superman”): a man who would embrace existence as it is and redefine the values of society beyond morality with his own independent and individual values.

So, to summarize, Nietzsche “blamed” Greek philosophy (which was influenced by Egyptian morality) and Zoroastrianism (the ancient religion of Iran) for the Christian dominating morality of Europe, as well as eastern dharmic religion for influencing western philosophy and leading society into nihilism. In his view, religion (and its morality) was a method of control that had to be overcome to return value to the individual.

The setting of the Akademiya

The Akademiya's original Chinese name is Sumeru Institute of Religious Decree, which means it acts as a religious institution that treats religion and education as one and the same. This church of knowledge also grants power to its elite class (formed on the basis of academic merit) who rules the nation as an extension of the god of wisdom.

The Akademiya plays three roles of authority at the same time: spiritual, educational and political, all three which serve as a means to control and shape the values of the population. The Akademiya decides which knowledge has worth and which material is allowed to be learned, it decides which faith in which god has value or is allowed to be practiced, and it decides who occupies positions of political authority and who can access the education necessary for class mobility.

In short, the Akademiya is a form of governance that has the power to define and limit the values of society: its rules, beliefs, morals, ethics, hopes and even its dreams.

However, unlike Nietzsche's assessment, it's egoist values that dominate Sumeru under the Akademiya's guidance.

The culture of the Akademiya separates people into the ordinary and the extraordinary, those who live in submission and those who stand out. There is no community between scholars, only associations where each party must benefit for the duration of the projects they collaborate in, then they are terminated.

"Relationships are merely a byproduct in this exchange of interests. They may be pleasant and captivating, but they can only ever be secondary. When scholars collaborate to solve difficult problems, we freely share our knowledge and resources with one another, as if we were all kin. However, this collaboration ends after the results of our work are published. The reason is simple: We are scholars, and there are new projects that await our attention."

This type of association described in Nilou's story quest seems very similar to Max Stirner’s Union of Egoists, an idea he proposed as an antithesis to communal society where individuals conceptualized each other as “property” that either has or doesn't have use in one's life.

As Paul Thomas summarized, Stirner believed that “we should aspire not to the chimera of community but to our own “one-sidedness” and combine with others simply in order to multiply our own powers and only for the duration of a given task.”

Egoism and God

Max Stirner was the first philosopher to publish work on egoism with The Ego and Its Own in 1844, his influence on Nietzsche is contended due to the similarities in the foundation of their ideas.

It was Stirner who first presented the concept of the death of god, meaning that society could no longer hold on to religious beliefs disproved by the scientific advancements of the Enlightenment. Nietzsche would later coin the phrase “god is dead”, and both identify man as the killer, although Stirner argued that the god of religion had been replaced by the god of humanistic values and Nietzsche proposed for man to become god himself.

Here's Stirner's quote (The Ego and Its Own, 1844):

At the entrance of the modern time stands the "God-man." At its exit will only the God in the God-man evaporate? And can the God-man really die if only the God in him dies? They did not think of this question, and thought they were through when in our days they brought to a victorious end the work of the Illumination, the vanquishing of God: they did not notice that Man has killed God in order to become now—”sole God on high." The other world outside us is indeed brushed away, and the great undertaking of the Illuminators completed; but the other world in us has become a new heaven and calls us forth to renewed heaven-storming: God has had to give place, yet not to us, but to—Man. How can you believe that the God-man is dead before the Man in him, besides the God, is dead?

Here's Nietzsche's quote (The Gay Science, 1882):

God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?

Both likely drew from the work of Ludwig Feuerbach on religion as a projection of human ideals into divine attributes. For example, omnipotence reflects human desire for control and power, while omniscience reflects human thirst for knowledge and aspiration to overcome ignorance.

Sumeru’s ubermensch

The plot of the Sumeru chapter presents a nation in the aftermath of the death of their god, Lord Rukkhadevata. The political class struggles to accept the new god left in her place, as she's far from representing the ideals of wisdom they aspire to project on their archon, and thus fails to provide meaning for scholars’ quest for knowledge.

The sages then set out to manufacture an artificial god with their collective human wisdom, a projection of themselves in the vessel of a god, transcending all established ethical (and moral) boundaries.

The vessel for this artificial god has his own motivations, which in the fairy tale that stores his memories it's depicted as such:

They essentially create an artificial ubermensch capable of redefining values, but the real ubermensch is found behind the artificial god itself.

Crime and punishment

Nietzsche called Fyodor Dostoevsky the only psychologist he had anything to learn from, as he was deeply influenced by the psychology of his novels —of which he read botched translations that didn't quite transmit the author's philosophy, but still.

The novel Crime and Punishment has a protagonist that represents the opposite of the author's beliefs, who happens to be quite similar to Nietzsche's idea of the ubermensch or the higher man. This character justifies his crime (a murder) to himself arguing that people are divided into the ordinary and the extraordinary, and the extraordinary have the right to commit crimes if it allows them to put forward their extraordinary contributions to the world.

From Crime and Punishment:

“Ordinary men have to live in submission and have no right to transgress the law, because, don't you see, they are ordinary. But extraordinary men have a right to commit any crime and transgress the law in any way, just because they are extraordinary.”

“...if the discoveries of Kepler and Newton could not have been made known except by sacrificing the lives of one, a dozen, a hundred, or more men, Newton would have had the right, would indeed have been in duty bound…to eliminate the dozen or the hundred men for the sake of making his discoveries known to the whole of humanity. But it does not follow from that that Newton had a right to murder people left and right to steal every day in the market.”

The protagonist sees himself as an extraordinary man, therefore, his murder is justified in contribution made to the world in exchange.

For Nietzsche, who sees life conditioned on the dominance over the life of others, a criminal is a man whose primordial human impulses to exercise power, which in the ordinary men have been suppressed by the dominating morality, have found an unconventional outlet through crime. Thus, a criminal is a symptom of a sick society that has domesticated itself out of its own nature.

The criminal as a glorified outcast, a rebel against modern society whose abhorrent behavior is a healthy instinct that denotes potential —at least symbolically, he wasn't calling out to people to commit crimes per se.

While Dostoevsky wrote the protagonist of his novel to struggle with guilt in the form of an illness and allowed him to find salvation in facing punishment for his crime, Nietzsche holds the criminal in high regard, seeing guilt as something beneath him.

This archetype is popular in media with characters like Hannibal Lecter, and indeed, many fans of the game expected Alhaitham or Scaramouche to fulfill it, but the character that truly embodies the outcast genius is The Doctor.

Dottore commits crimes against others to carry out his plans, never feeling guilt or shame. He was expelled from the Akademiya precisely for violating the ethical code all scholars are governed by and, as Nietzsche's ubermensch, aims to redefine the values of the world by collaborating with the Tsaritsa to “burn the old world.”

However, Dottore is the antagonist of the chapter, and the attempt at manufacturing the artificial god is depicted as an act of hubris, not a brave crusade against the restraining morality of religion. Furthermore, both the sages and Scaramouche face punishment (in their own way), something Nietzsche would disapprove of in an appropriate higher man.

Looking back on the Akademiya, the scholars seem to suffer under the culture of egoism and competition so well established in the institution.

They're often disoriented in their life, contrasting with the villagers who know themselves and their place in the world.

And the god the sages had dismissed as unworthy is reinstalled as the archon, maintaining the institution as it was while taking down the Akasha, the method of control of the sages.

Nietzsche’s egoism is rejected by the narrative, it raises and it falls in the course of the chapter, but what does this mean for the region?

Part 2 will examine how the narrative engages with the philosophies of altruism and how both egoism and altruism converge in the characters of Alhaitham and Kaveh

#sumeru#long post#genshin lore#posted some weeks ago and meant to cross post here the two parts together but i dont think its gonna be written in quite a while#main post

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

changing fate in teyvat is possible

how?

(i didnt know what to do with this thought so i guess im just leaving it here)

scaramouche has feelings and emotions like a human, behaves like a human, and is accepted as a human by other humans, but he insists that he isn't because he doesnt have a heart. so we're being told explicitly that what defines a human in the world building of genshin is a heart.

we are not told textually what the concept of heart really means, however.

by the end of inversion of genesis, we come to understand that a human is that who defines themselves a human.

if scara defines himself a human, then he is a human.

scara spent most of his life(s) being defined by others: his names were given by other people. he says he is a blank slate, so he allows others to give him meaning/value. after all, he has a unique kind of existence, he's neither human nor tool, and both at the same time. he does not have definition of his own.

we could say, then, that a heart is definition.

but scara wasn't born without a heart, it was taken from him: the gnosis. this is what initially defined him, it was taken from him, so he no longer had a definition. he was a blank canvas.

so here is the question: if individuals are born with a heart, with a definition, can they change or make a new definition for themselves?

a definition is what informs you who you are and what you can do. in that regard, is a heart not something like fate?

if fate is taken from you, can you make your own instead?

the kid tells scara: "what if hearts can be born from ashes?"

a new heart/definition/fate can be formed after a fire takes place.

my question would be, then, what is fire

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eternal Punishment: Ideology, Performance, and Martyrdom as Sunday's Expressions of the Death Drive

“Sleep sleep happy child. All creation slept and smil’d. Sleep sleep, happy sleep, While o’er thee thy mother weep” -William Blake, “A Cradle Song,” Songs of Innocence and of Experience “So, where is my dream?” “It is a continuation of reality.” “But where is my reality?” “It is at the end of your dream.” -The End of Evangelion (1997)

Considering the majority of his development occurred in Penacony’s third act, Sunday has proven himself as a compelling antagonist who rivals both Takuto Maruki (Persona 5 Royal) and Kevin Kaslana (Honkai Impact 3rd) in grandiosity and pessimism. Although his motivations and methods closely resemble theirs, the tragic path that led Sunday to his rigid belief system began when he was still a child and is intimately related to his experience with family. Having both witnessed the suffering of others and experienced it himself, Sunday’s ideology was born with a single purpose: to shelter humanity from the pain of reality. His answer to life appears rational on its surface and is constructed with kind intentions, but in practice it would have damned the cosmos to a purgatorial world of constancy and doomed its creator to infinite loneliness. It is this tension between Sunday’s intentions and the truth of his actions that fascinates me, because it reveals a deeper conflict within him that is also at the center of Penacony’s story. Here, I’ll use some of Freud’s psychoanalytic theories to illustrate what exactly that conflict is, and why it’s so important for a full understanding of both Penacony's finale and Sunday’s arc thus far.

Cohesion not guaranteed, my brain feels like swiss cheese after 2.2

Spoilers for the entire 2.2 Trailblaze Mission (In Our Time) and a small post-quest with Robin (The Feather He Dropped).

Disclaimer: All content in this post, especially the psychoanalysis, should be taken in the spirit of media analysis and nothing more. Also, corrections and additions are welcome, whether they are about interpreting Freud or HSR. :)

To cut down on post length, external sources (that is, any reading that is not official Star Rail material) are given as numbered in-text citations and gathered in a pastebin document linked at the bottom with the full title and exact page numbers of the source.

And before we begin, a huge thank you to my boyfriend for proofreading this numerous times despite not having played any Hoyoverse games, and for talking out the philosophy with me T_T That’s love right there!

Penacony, Freud, and the Occasion for the Death Drive

“The IPC does not care about its workers! I bet you they would love it if those monsters came and killed me. That way they wouldn’t have to pay for my pension!” “Sounds like somebody could use a Sprinkles cupcake!” -It’s Always Night in Penacony Show

It is impossible to avoid Sigmund Freud when discussing the psychology of dreams, and his psychoanalytic theories are tightly woven into nearly every aspect of Penacony’s environment and story. Our most salient point of entry into his work is The Family’s sweet dream, which embodies the base instinct in human nature towards pleasure-seeking behavior and instant gratification, even at the expense of self-preservation, also known as the pleasure principle.¹ Be it slot machines, luxury cars, decadent food, or endless shopping malls, everything in the sweet dream exists to further each guest’s pursuit of pleasure—such is the purpose of dreams, Freud theorized, as vehicles for wish-fulfillment.² “Death,” let alone pain, is not allowed to exist in the sweet dream in order to preserve that pleasure:

“A further incentive to a disengagement of the ego from the general mass of sensations–that is, to the recognition of an ‘outside’, an external world–is provided by the frequent, manifold and unavoidable sensations of pain and unpleasure the removal of which is enjoined by the pleasure principle, in the exercise of its unrestricted domination. A tendency arises to separate from the ego everything that can become a source of such unpleasure, to throw it outside and to create a pure pleasure-ego which is confronted by a strange and threatening ‘outside’” (Freud, 1930, p. 4).³ “One of the twelve Dreamscapes in Penacony, and its time coincides with midnight. Here, the dream's time is forever stuck at 00:00. Tomorrow will not come, and this night of revelry will never end” (Loading Screen: Golden Hour). Gallagher: …Think about this — what would it cost to create and maintain such a lavish dreamland? Gallagher: It's people's lives. The opulent dream is built upon the decay of spirits, with a toxic elixir called "pleasure" flowing through the Dreamscape. It tempts people to indulge in the Dreamscape, and gradually their minds succumb, becoming nourishment for the sweet dream. (The Public Enemy)

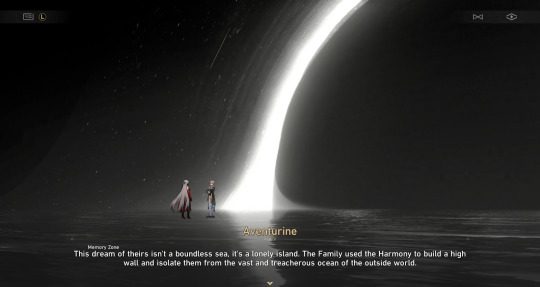

Aventurine: This dream [Memory Zone] of theirs isn’t a boundless sea, it’s a lonely island. The Family used the Harmony to build a high wall and isolate them from the vast and treacherous ocean of the outside world.

But “death” still lurks beneath the juvenile fantasy and its sweet commercial lies, in the yawning chasm proceeding spiritual death. This space, the Primordial Dreamscape, is a chaotic rendering of memories and emotions that goes beyond consumerism as the ultimate form of pleasure, and the high walls of the sweet dream separate each “Moment” from its depths. It is the original form of the sweet dream, its primitive reflection in the Memory Zone’s water, and the crystalline bodies of its memetic entities are like mirrors into the past inviting guests’ introspection.

Introspection is the Achilles’ heel of The Family’s superficial paradise, because curiosity about oneself redirects the ego’s interest from external objects to the inner abyss of thoughts and desires deemed unacceptable in reality, and remembering their existence reveals psychic pain. The Family’s denial of these ‘impure’ thoughts reflects the process by which the ego represses instinctual impulses to avoid that pain:

Robin: While I was away from Penacony, the boundaries of the Twelve Dreamscapes kept expanding outward. But whenever I mentioned the anomalies in my dreams... all The Family heads refused to talk about it. Only my brother was willing to respond... Robin: Later, I discovered the secret letters from the IPC ambassador, which further convinced me that there are hidden secrets beneath the surface of Penacony. So, following the clues in the Oak Family's dossiers, I found my way here... Robin: ...The land of the exiles, concealed by The Family under the guise of "Death", a dream within a dream where Penacony's past is buried. (Small Town Grotesque) “Life is parceled in impenetrable barriers, obstructing the intrusion of the alien. But beneath that ironclad shell, there is a region both nameless and fragile” (Memory Zone Meme “Heartbreaker” Story). “We are very apt to think of the ego as powerless against the id; but when it is opposed to an instinctual process in the id it has only to give a 'signal of unpleasure’ in order to attain its object with the aid of that almost omnipotent institution, the pleasure principle” (Freud, 1926, p. 92).⁴

Freud begins Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920) by pointing out the foundational assumption of psychoanalysis, namely that all psychic processes serve the pleasure principle in infantile life and the reality principle at a later point of ego development. The reality principle arises from the ego’s instinct for self-preservation, and it redirects pleasure-seeking behavior so that one is willing to wait for its payoff. Rather than relying on dangerous sources of pleasure that provide instant gratification, instead the constraints of reality (or “time”) imposed on the ego and any consequent pain (or “tension”) are endured for the sake of eventual pleasure.⁵ For psychoanalysts, this only further cemented pleasure’s importance in mental life.

However, as World War I came to an end, Freud found these principles alone were insufficient to explain the purpose of trauma dreams in veterans returning from the battle front. Their dreams would faithfully recreate traumatic memories from the war each night, with no pleasurable payoff for the dreamer, and this directly contradicted Freud’s theory of dream interpretation.⁶ If trauma dreams did not fulfill the dreamer’s unconscious wishes, then they did not follow the pleasure principle; they seemed to serve some other purpose.

Though unconsciously repeating pain in waking life was not a new idea in psychoanalysis, trauma dreams highlighted a critical flaw in its understanding of this behavior’s ends. To untangle this complexity, Freud reexamined the aims of the “compulsion to repeat,” and speculated that it is not only an instinctual behavior, but also has an earlier origin than the pleasure principle. He then proposed a dualistic theory of desire that revealed something he believed was common to all organic life—that if there are life instincts, or what he called “Eros,” that are geared towards an organism’s pleasure and self-preservation, then there is also a primary death drive, or death instincts, that aims for its destruction:

Acheron: The Beautiful Dream is crumbling, but not because of a particular Aeon, a particular faction, or a particular visitor. Its collapse stems from a certain inevitability of human nature. The Family refuses to acknowledge this, and it has ultimately backfired and become a catalyst… Acheron: As people immerse themselves in the Dreamscape, where consequences and pain cease to exist, and only ease and pleasure prevail, they draw closer and closer to necrosis. Regardless of the perceived bliss, death looms as the inevitable conclusion. Acheron: Also, this necrosis will diffuse and spread. One piece of the puzzle’s mutation will eventually cause the entire building to shake, break…and crumble. Welt: …In the end, the dreams that people built in the name of freedom became the cage that imprisoned them. (When the Sacred Ginmill Closes)

The “inevitability” Acheron refers to is one and the same with the death instincts as illustrated through the Nirvana principle, originally proposed by psychoanalyst Barbara Low and adopted by Freud in Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Early on in the work, he identifies G. Th. Fechner’s principle towards stability, or the constancy principle, as a greater implication of the pleasure principle’s terms. According to this principle, the psychic apparatus (or ‘psychic processes’) aims not only to relax psychic tension to avoid pain, but also to keep tension low and constant.⁷ But this raises a problem: the pleasure principle’s express purpose is to avoid pain, but pleasure is a finite state that can only be felt as such if there is pain to reduce in the first place. If this balance is interfered with, we do not preserve the initial euphoria of pleasure infinitely, but instead find it dulled with time until it approaches ‘zero’:

“When any situation that is desired by the pleasure principle is prolonged, it only produces a feeling of mild contentment. We are so made that we can derive intense enjoyment only from a contrast and very little from a state of things” (Freud, 1930, p. 16).⁸

This ‘zero’-state is the aim of the Nirvana principle, where it is not just the reduction of excitation but rather its total elimination that is ultimately desired.⁹ In other words, its aim is stillness through the suspension of psychic processes, a state of being that could only find its analogue in dormancy,¹⁰ or something unto death. Acheron’s point is that this necrotic, empty feeling is not an accident, because “death” lays the foundation for something new.

And this, at last, brings us back to Sunday. Incongruence, fantasy, and wishful thinking are just some of what drives Sunday to create his ideal world, a paradise where every day is a day of rest. Though his methods are misguided and extreme, he does this out of compassion for the weak and a sense that he must catch them in his paradise before they crash to their death. In truth, this “paradise” was death in a different form, where reality is inverted with one’s personal fiction and conflict is transcended by removing choice. The conflict between the life instincts and death instincts is key to understanding how Sunday arrived at this answer to life’s pain, but to understand the depth of that conflict we must go beyond his facade and grasp the true meaning of his infantile fantasy. By employing a Freudian psychoanalytic reading of Sunday’s arc, I hope to open new avenues of discussion about both his character and the meaning of Penacony.

The Prison of Fate

“Is darkness equal to daylight? Are sinners equal to the righteous? If you are born weak, which god should you turn to for solace?” -Sunday, Everything that Rises Must Converge “You know, in the thick of things, people are blind to the grit in their eyes...yet they can always feel its scratch. Want the answer? I'll give it to you. The whole thing is just fate playing a cruel joke on us.” -Gallagher, A Walk Among the Tombstones

We’ll begin with Sunday’s warped understanding of society and his ideology, as these represent the first layer of his fantasy. What’s striking about Sunday’s reading of human nature is his pessimistic outlook on human relationships and the potential for individuals to change. Sunday believes that life obeys a natural law called “survival of the fittest,” a perverse interpretation of Darwinian principles of evolution, that categorizes individuals as “strong” or “weak” based on inherent, unchangeable qualities within them. This law is the foundation of a chaotic world where the strong do not defend the weak, but trample them for their own gain:

Sunday: While the Harmony holds noble aspirations, the strong will always be strong, and the weak will always be weak, even in this carefree dream... Human nature contains greatness, but it also harbors inherent weaknesses that can't be eradicated. Sunday: In the end, if people can't even secure their own survival, they won't care about the illusory future of equality. As long as the law of survival of the fittest prevails... there will always be fledglings crashing to their death. (The Only Path to Tomorrow)

Sunday’s ideology takes a page from Arthur Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Idea, where he argues that the will to life is the reason individuals suffer, because, like the pleasure principle, “the basis of all willing is need, deficiency - in short, pain.”¹¹ Willing is a feature of individuality, which Schopenhauer further identifies as an illusion of nature—that is, individuality obscures how all life is an expression of one underlying Will, the common source of life.¹² In Sunday’s ideology, Schopenhauer’s “individuality” and “willing” are substituted by the term “self-value,” which forms the basis of the illusory prison of human consciousness. Self-value, then, is the root of human suffering, because satisfying the will to life requires taking “value” from others:

Robin: That's just sophistry. If that were true, then only the powerful would have the right to determine the future. Sunday: Unfortunately, that's exactly what happens. Another name for "the future" is "self-value." [...] Sunday: Some are born weak and vulnerable, some find themselves trapped in unfortunate circumstances, some fall victim to malice and cowardice. When it comes to survival, everyone is equal, and the weak can only watch as their value [future] gets constantly diminished by external forces. (The Only Path to Tomorrow) Firefly: So, what is your definition of living a happy life? Sunday: Good question. Human consciousness is fundamentally an illusion, a cage known as "self-worth". People lured in by this illusion, make mistakes, yet still ask that external influences bear the burden. Sunday: When one mistake after the next permeates the masses, they become impossible to trace... Thus, the amassing of these individual cages culminate to form a prison, a place dictated only by the rule of "survival of the fittest." Sunday: Nature is always accompanied by predation and sacrifice... Its antithesis is known as Order. (Beauty and Destruction)

As long as the will to life must be satisfied, “survival of the fittest” will persist; in other words, the illusion of self-value ensures the law’s survival in the future. While this tells us part of why Sunday equates self-value with the future, his statement can also be interpreted through a psychoanalytic lens, particularly as it relates to transference and the repetition compulsion. Transference is the process by which people unconsciously cast the roles of past figures onto current relationships, repeating past trauma in the present. The individuals filling the roles may change, but the roles themselves remain constant through time. Through transference, a person’s unresolved past and unconscious beliefs adopted from those experiences construct an illusion that passes for objective reality:

"What psycho-analysis reveals in the transference phenomena of neurotics can also be observed in the lives of some normal people. The impression they give is of being pursued by a malignant fate or possessed by some 'daemonic' power; but psycho- analysis has always taken the view that their fate is for the most part arranged by themselves and determined by early infantile influences" (Freud, 1920, p. 15).¹³

Transference is driven by an underlying compulsion to repeat the past known as the repetition compulsion. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Freud found that the repetition compulsion does not solely operate in service of the pleasure principle as it was previously understood, but also as an unconscious compulsion to repeat pain. Psychoanalyst and scholar Jonathan Lear provides an example of this in Freud (2015) when he describes the nature of unconscious mental processes:

“Suppose, to take a highly simplified case, a child has an unconscious fantasy, ‘I am the unloved one.’ Precisely because this fantasy is exempt from contradiction and is presented in a timeless mode, the person will tend to interpret life’s passing events through a frame of feeling unloved. The person will focus on real-life slights; but even kind gestures will tend to be treated with suspicion, as though there must be some underlying motive (‘He was nice to me only because he wants something from me’). The world will come to seem an unloving place, thus reinforcing the fantasy. The person can come to feel that she is somehow fated to be unloved.” (Lear, 2015, p. 6).¹⁴

To put Lear’s example in Sunday’s terms, an unconscious fantasy adopted from past experiences is the underlying material that constructs the illusory prison of self-value. The prison shapes our perception of reality, and this perception then reinforces the prison’s ‘form’ by affirming the unconscious fantasy. If one’s perception or the fantasy were to change, the dimensions of the prison would change with them, reshaping ‘reality.’

The prison of self-value therefore ensures the past’s survival in the present by facilitating its repetition; through repetition, the past becomes the prisoner’s future. In other words, by materializing the unconscious fantasy in reality through actions, the prison of self-value becomes one’s fate. We can then apply this framework to Sunday’s ideology: if fantasy and perception co-construct one another to create an individual human consciousness, it follows that Sunday’s ideology, as a reflection of his perception of the world, is rooted in an unconscious fantasy too, a belief that he has about himself.

Sunday: Well, don’t forget this…. not everyone really has a future.

So, just what is that belief? The past holds great significance to Sunday, and he vividly remembers the consequences of each decision he made. While in his inner world, he recounts three decisions that led him to lose faith in the Harmony and choose the Order for salvation. These decisions involved a Charmony Dove he and Robin found as children, a fraudulent stowaway, and Robin’s brush with death while she traveled beyond Penacony. He then asks which choice the Trailblazer would make given each scenario—the same choice as Sunday did, or some other choice? However, the choices are limited to either-or decisions between Sunday’s choice and its extreme opposite: either support Robin’s journey, or prevent her from taking it; either remain silent, or ask the Bloodhounds for mercy; either cage the Charmony Dove, or build a nest for it in a yard of predators, and no matter the choice, it always ends in tragedy.

Sunday: I know the suffering of being tormented, the turmoil of losing your way, how sorrow… and even despair, set in when matters don’t work out. All of this causes me unending pain, because this is not what “happiness” is at all.

This is because Sunday understands the world in terms of dichotomies, where things are either good or bad, righteous or sinful, strong or weak. It’s also why Sunday’s choice in each scenario is cast as the “good” choice, because it was made with kind intentions, while its opposite is the “bad” choice because it lacks compassion for the individual. The unfortunate outcome of either decision, both real and imagined, is therefore meant to persuade the player that Sunday’s perspective is ultimately correct, because “good” choices do not necessarily result in “good” outcomes in a disorderly world. Rather, choice itself is a chaotic variable that introduces uncertainty, splitting life into infinite paths and possibilities, or “untraceable mistakes.” In order to control outcomes, choice must be removed, even if such an outcome can only be achieved through fantasy.

To see the world in this way is to inhabit the monochrome world Acheron first referred to in Act I, a world where it’s all or nothing, and everything appears black or white. This manner of thinking constructs each decision as a false dilemma, which artificially limits the available options or perspectives to two extremes. For our purposes, this is among the most meaningful hints as to what Sunday’s unconscious fantasy is, because it is born out of his intense need for control, which is both a defense against the fantasy and the primary way that he repeats it.

Acheron: The golden dream is getting restless. In the coming long night, I'm afraid you will face many tribulations and witness many tragedies. And finally...your sight will only see black and white. Acheron: But please believe me that in that monochrome world, there will be a glimpse of fleeting red, and when you make a choice, it will reappear before you once more… (The Knocking at Ungodly Hours)

With this in mind, we can use Sunday’s black and white thinking to our advantage. Upon closer observation, a common theme is repeating itself in each decision Sunday did make, with each individual cast in the same role at different points in time. Despite his best intentions, Sunday’s actions alone can’t protect them from tragic outcomes—indeed, he is powerless against their fate. According to his ideology, there are inherently strong individuals and inherently weak individuals, and the strong have the power to defend the weak, but often choose not to; by this same logic, if Sunday can’t defend the weak despite his intentions to do so, then he must not be strong. He must be weak.

This brings us to the Charmony Dove’s fate, which is undoubtedly the most significant to his character out of the three scenarios, and acts as a symbol of the difference between Sunday’s and Robin’s beliefs regarding humanity. The bird is an object that they project these beliefs onto, shaped by their individual “cages,” and its fate reflects those beliefs back at them, reinforcing their diverging fantasies:

Sunday: This place is too dangerous for a fledgling. Let's take it with us — we can put it on the wooden shelf in front of your window. Robin: Okay! A bird like that must have a beautiful singing voice. But where will it live? Sunday: I'll ask the family head to build a cage for it. Robin: A cage... but then it won't have the freedom to fly, right? [...] Robin: Even if it's small and not fully feathered, and can't sing... it didn't come into this world just to be locked up in a cage. Robin: Birds... belong to the sky. (The Only Path to Tomorrow)

To Robin, the Charmony Dove is full of potential, and its fate can’t be determined by a single moment of its life, but Sunday regards it with caution and uncertainty; one wrong move, and the bird will take its last breath. This difference becomes the central disagreement in their debate over the sweet dream’s value, and Sunday reveals the bird’s tragic fate to Robin in order to drive home his point:

Sunday: Shortly after you left, it crashed to its death right in front of your window. Robin: ...I had surmised as much. I knew you wouldn't have avoided mentioning the bird for no reason. Robin: Despite that unfortunate outcome, I still believe it was the right decision. Birds aren't meant to spend their lives in cages... They belong in the sky, even if they can't fly. Sunday: But here's the thing. If there are birds in this world that can never fly, can we really assert that they belong in the sky?

Sunday’s meaning is clear: flightless birds are no different from those individuals who are born weak, and their fate is to watch their future disappear under the pressure of external influences. While Robin came to embody her beliefs by leaving Penacony behind, Sunday stayed and rose through the Oak Family’s ranks, never leaving the sweet dream’s cage. He embodies his beliefs by denying himself a future, because to choose otherwise would contradict his fantasy—that he is a flightless bird too, and therefore has no “value”:

[Sunday]: The victor bears the responsibility of victory. Finish me... and fly into the sky. [Robin]: We were supposed... to fly into the sky together. [Sunday]: ... [Sunday]: If only... I could… (The Feather He Dropped)

Sunday's unconscious fantasy—that he is an inherently weak person, a bird that will never fly—is a reflection of his self-value. By unconsciously repeating the pain of his past, his fantasy becomes the illusory prison known as one’s future, a self-fulfilling fate.

But all of this is only a small piece of the puzzle. It tells us what the unconscious fantasy is and how it affects him, but it doesn’t really tell us why he has it in the first place. Just as the belief was hidden in the shadows of Sunday’s ideology, its origin is hiding behind something even more conspicuous—a grand performance on the dreamscape’s finest stage.

An Infantile Drama

Trailblazer: Where is the Stellaron? Why am I not seeing it? Sunday: It hides behind the curtain. Or rather, it is the theater itself. (Everything that Rises Must Converge)

Naturally, this leads us to the Embryo of Philosophy.

There is so much to talk about between the three phases of this entire fight, not to mention the mountains of references it makes to other media. However, I want to train our attention on the Embryo’s tears. Why is it crying, and why at this particular moment? The religious meaning of its tears is clear, but what is their psychoanalytic significance?

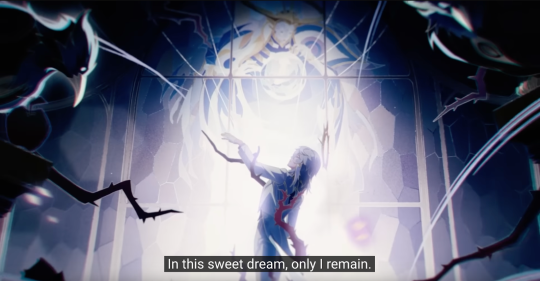

First, let’s consider their context. The Embryo’s golden tears stream down its face with each turn of “Im Anfang war das Wort” (“in the beginning was the word”), stretching its arms towards the sky with palms open in worship of Order. On the 8th turn, it reaches toward the sky to ask for Ena's blessing; Ena answers its call, reaching down to grant it power, nearly touching the Embryo’s outstretched pointer finger with THEIR own. In doing so, they create a mirror image of Michelangelo's The Creation of Adam, a depiction of God giving Adam the spark of life.

This artistic and religious reference, alongside the Embryo’s fetal imagery and tears, leaves no doubt that the third phase in the fight is Sunday’s “moment of birth” as an Aeon, and this suggests that birth must inform the answer to our original question. So then, why does the Embryo’s “birth” bring it to tears? The answer lies in the meaning of Sunday’s performance in Penacony Grand Theater, of which the Embryo is just one part, and how it relates to his unconscious fantasy.

In a final effort to dissuade the Astral Express from resisting his plan, Sunday stages a dramatic retelling of the Order’s Genesis story and Penacony’s history that chronicles its changing masters through the eras. As an immersive stage play, its completion hinges on the crew’s participation, which involves slaying the master at each act’s conclusion in order to usher in the next one. Through his play, Sunday argues that humans crave a master who can provide them with meaning in the face of chaos, and because of this inherent weakness, progress is an illusion. The past, present, and eternal show of human history is one of endless repetition and self-delusion – though the individual master may change, humans remain puppets by their own design.

The Past, Present, and Eternal Show

This fraught relationship between humanity and its masters was a foundational point of Freud’s theory of the death instincts, which he grounded in his observations of infantile play. While he was staying with his daughter’s family, Freud noticed a peculiar game his grandson played with his toys that further called the pleasure principle’s dominance into question. The game began when his grandson threw the toys out of sight to make them “disappear,” after which he would retrieve them with his mother’s help to make them “return.” Freud deduced that this game (Fort/Da) was a reenactment of his mother “disappearing” when she left him at home, and speculated that it played a crucial role in his grandson’s good behavior during her absences.¹⁵ If the game was in service of the pleasure principle, Freud expected that the entire game would be played to completion, where the pain of the toys’ disappearance is endured for the eventual pleasure of their return. Instead, his grandson often only repeated the disappearance – the “drama’s” most painful part.¹⁶

In infantile play, several instincts intersect with a child’s memory in order to process psychological stimuli.¹⁷ Repetition facilitates their sense of mastery over unfamiliar stimuli, whether pleasurable or painful,¹⁸ and play offers a safe, fictional space for children to make sense of reality, where they can leave behind their role as spectators of life’s phenomena and become actors on its stage.¹⁹ By playing an active part in a memory’s repetition through play, indeed by controlling it, children move toward an even grander wish in their hearts: “the wish to be grown-up and to be able to do what grown-up people do.”²⁰ Freud suspected this was why his grandson played the game, because it offered him a sense of agency over his mother’s absences that reality could not.

The Golden Hour base model and its uncanny inhabitants, found in Dewlight Pavillion. One of the Oak Family Head’s toys.

However, Freud’s point was not that repetition in infantile play is pathological, but rather that when trauma is repeated in adult life—a time when experiences do not feel so new, and therefore do not bring as much pleasure or sense of mastery per repetition²¹—the mind is reverting to a previous state,²² namely to the way it functioned in childhood. In other words, the repetition compulsion is related to the instinct for mastery, and trauma repetition is the mind’s attempt to master a painful experience by replaying the past in the present, as it did through infantile play. In this way, life itself becomes the game, or a “play,” and fantasy merges with reality.

Now, let’s examine the conclusion of Sunday’s stage play, as humans take fate into their own hands on the Genesis story’s seventh day:

2:1 THEY bestowed upon all beings the gift of ‘meaning.’ All had been brought into existence. And then, THEY rested from all THEIR creative work. 2:2 However, once again, all the beings beseeched Ena, praising THEM, the magnificent Aeon with divine power, but with a tone of curse. 2:3 ‘With Order, you have defined all things in the Cosmos, yet this only made us realize that we are mere puppets within your grasp.’ 2:4 Thus, on that day, all beings united and cast the Aeon into the pit of destruction. 2:5 And so it was done. That marked the seventh day. (Lost Property readable)

Like a parent guiding their child, Ena imbued the universe with meaning through Order, weaving the answer to each of humanity’s questions into THEIR grand symphony. Humanity then recognized its passive role in relation to Ena, a higher being who is able to act on the universe’s grand stage, while mortals merely watch THEM. And just as Freud’s grandson casts away his toys in the first part of the drama, humanity then casts Ena into the abyss to make THEM “disappear,” rejecting their old master in a bid for control only to seek THEM out again in the eternal show. In their effort to become masters, humans seal their fate as puppets; or by another interpretation, this is the intended outcome all along, because out of the two desires at play here—the desire to replace the master themselves and the desire to submit to another—answering to a new master is far easier than becoming one:

[Tiernan]: Sin Thirsters... the obsessions of the Pathstriders. They emerge from the depths of IX, seeing themselves as masters of their own destiny, unknowingly repeating the actions of their past lives. [Tiernan]: They emerge from the Nihility and head toward it, leading purposeless lives… (And on the Eighth Day) Butler: "Either I shall be my own master, or I shall return to my former master! I shall not submit to a new master under any circumstances!" "I wish they could regain their reason [calm down] and cast away the shackles of hypocrisy," proclaimed the new master. (Tune Butler's emotion to Calm) Butler: "Without a master, who can grant me true freedom?" (Everything that Rises Must Converge)

By returning the planet to Order, its Pathstriders hope to reinstate the earlier phase of galactic history before Ena was absorbed by Xipe the Harmony. Understood through Freud’s observations of infantile play, this can be seen as a struggle between retaining the innocence of childhood, the previous state, and the “grand wish” to become an adult with agency; desires that are at once contradictory, and yet work in tandem with one another. But is this really all that Sunday’s performance is about?

For the moment, let’s return to trauma repetition and its conflict with the pleasure principle. To Freud, trauma is like a bodily wound, where unfamiliar stimuli “breach” the mind’s protective layer and overwhelm it; the repetition compulsion is a response to this breach, replaying past trauma in the present so that the mind learns to anticipate the disturbance in the future:

“The fulfilment of wishes is [...] brought about in a hallucinatory manner by dreams, and under the dominance of the pleasure principle this has become their function. But it is not in the service of that principle that the dreams of patients suffering from traumatic neuroses lead them back [...] to the situation in which the trauma occurred. [...] These dreams are endeavouring to master the stimulus retrospectively, by developing the anxiety whose omission was the cause of the traumatic neurosis” (Freud, 1920, p. 26).²³