#túatha dé danann

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

current shrine, offerings to the túatha Dé included :^)

#I wish I had a lugh statue! but the jar of feathers stands in place for that atm#personal post#altar#shrine#pagan#túatha Dé Danann#or was the tag#túatha Dé

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are sources+resources available for the mythological cycle / the tuatha de danann?

Good question! And, it is really good to ask about this sort of thing, so good on you!

While normally I would recommend reading the primary sources first and then delving into secondary discussions, the Mythological Cycle is probably one of a few areas where I would actually recommend people read discussions of the material first.

Why would I recommend this? Well, while all of medieval Irish literature has issues with widespread misconceptions, the Mythological Cycle is a big danger zone with these misconceptions, and I think it is best to go well-armed into the sources.

With this in mind, I have two 'introduction' level texts to suggest:

(A) The Mythological Cycle by John Carey, which is accessible, inexpensive, short, and written by the unquestioned world expert on the topic of the question of mythology in early Ireland.

(B) Ireland's Immortals by Mark Williams, which is more expensive and longer, but delves into the modern reception and relationship these texts have with modern revivalist faiths some of which diverge quite significantly from historic sources.

Having checked these out, at that point I would recommend digging into the stories. For some recommendations for these, I would point you to a post a colleague of mine made on the Association of Celtic Students blog which discusses notable texts with links to where to read them online. (Warning: links relying on the Internet Archive are currently broke'd because, you know, the Internet Archive is broken, but it should be up soon-ish?)

To build off that blog post, you can listen to me reading three texts from the Mythological Cycle if audiobooks/podcasts are your sort of thing. You can check out Dé Gabáil in t-Shída ('The Taking of the Hollow Hill'), Aislinge Óenguso ('The Dream of Óengus'), and part 1 and part 2 of Cath Maige Tuired ('The Battle of Mag Tuired').

After you have read some of those sources, I would then recommend checking out some more specific scholarly publications. For instance, I am a big fan of the recent piece: John Carey, 'Ireland: the Tribes of the Gods and the People of the Hills', in The Exeter Companion to Fairies, Nereids, Trolls and Other Social Supernatural Beings: European Traditions (University of Exeter Press, 2024). Here, John does that ever-so-important thing of actually bothering to put ink to page and provide evidence for the passively widely assumed stance of 'Oh, the people of the Otherworld have a society obviously structured similarly if not exactly the same as the people of medieval Ireland'.

I hope that helps, and if you have any further questions, feel free to reach out.

#mythology#irish mythology#celtic#celtic mythology#celtic myth#ireland#mythological cycle#irish myth#túatha dé danann

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

WELCOME TO IL-GENNA!

"You find a plane ticket in your mail. It first sounds sketchy, but the moment you read the handwritten letter by TÚATHA DÉ DANANN, a mega corporation and founder of Il-Genna, you realize that your eternal vacation is indeed waiting for you."

TÚATHA DÉ DANANN is a panfandom discord mfrp. Enjoy your eternal vacation in Il-Genna, befriend new people, join a guild, and learn a new job!

✦ active community ✦ 15 character slots (+possibilty to get more!) ✦ est. august 2023 ✦ neurodivergent friendly! ✦ friendly mod team! ✦ story arcs + extending lore!

RULES ✦ PREMISE ✦ ROSTER

#discord mfrp#anime rp#discord rp#discord rp group#manga rp#multifandom rp#panfandom rp#animated mfrp#anime mfrp

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

I heard "Bres" pronounced "Bresh" on the Story Archaeology podcast originally, and was pronouncing it as that since...but I'm curious about the way it should be pronounced, if "Bresh" is not the way it actually sounds. :0

The "e" in "Bres" is broad, hence the spelling of "Breas" in modern Irish, so it's "Bres." Exactly how it looks in English. Terribly anti-climactic, rhymes with "press" as per Mark Williams.

Honestly, it's fascinating, the pronunciation they're using in that podcast, because it's inconsistent. Off the top of my head, I can hear "Lu" for "Lug", which is modern, deriving from "gh" becoming silent, I can hear "Tuaha Dé Danann", which derives from the modern Irish elimination of the "th" sound, but "Bresh." When the modern Irish spelling of Bres' name makes it very clear that it has a broad quality to it. "Elatha" sometimes has a silent "th" which it wouldn't have in Old Irish, though I sometimes hear them using the "th", but "Tethra" has his "th" pronounced, there's no fada over "The Morrígan" in how it's pronounced ("Mor-REE-gan", which pushes the emphasis kind of onto the second syllable, though, ngl, I've always struggled with this one so don't take it too much to heart), "Cath Maige Tuired" is pronounced with a hard "d" at the end and a kind of broad "u"; the way it would be pronounced in OI would be "Maige Tehreth", with a slightly hard "th" sound like "those", "Dagda" is pronounced with a hard "d" instead of a softer, lenited "d" in the middle, more like "Dagtha", likewise for "Cridenbél", which I notice they also pronounce like it has a fada over the "i", "Dinnshenchas" is pronounced with the "sh" being pronounced like the English "sh" instead of the silent "h" sound you'd get from the lenited s, the emphasis sometimes strikes me as being on an odd syllable...) (Like, there's nothing wrong with using modern Irish for Old Irish pronunciations; you will personally almost never hear me use modern pronunciations, but that's a personal choice and one that makes people tend to think I'm even more of an idiot re: pronunciations than I already am, but...I'm fascinated, honestly, especially since some of these traits are things that you'd never get in any stage of the Irish language and that got beaten out of me relatively early in my academic career.)

...also I'm not certain I'd agree that LGE is much later than CMT...given that CMT is a ninth century text heavily revised in the 11th century; LGE is an 11th century text. Like, CMT actually *drew* on LGE at a couple of points. (It's astonishing, honestly, that even though they're blatantly cribbing from John Carey's "The Baptism of the Gods" in that podcast, they don't reference it.) Like, I do believe that there are sections of CMT that were written a couple of centuries earlier, but I'm really not sold that it deserves that kind of emphasis. (Especially when you're using Oidheadh Chloinne Tuireann, an early modern text, to talk about Balor and the men of Lochlann.)

("being committed to writing around the time of the Viking encursions" It is being AUTHORED during the Viking invasions.)

...it is impossible for Bres to be king of a single túath given that Bres is, explicitly, king of the Túatha Dé. There's no reason to think he isn't a high king of Ireland. Like, first line describing Bres' reign: "There was contention regarding the sovereignty of the men of Ireland between the Túatha Dé and their wives." Bres is king of Ireland. That's 100% in the text. No reason to suppose otherwise. He rules over multiple túatha and he is the king of Ireland.

...I don't understand why we can't assume that there are literal family names, as opposed to indicating a general familial relationship.

...I like the overall point about the Fomoiri not being a distinct foreign group, but are rather human, I like that there is an emphasis that it isn't just "stupid women electing the good looking one", I like the emphasis on Bres being essentially set up (even if, to be honest, I don't believe there's all that much evidence for it in the text) and the way that Elatha kind of creates him, it's something I've been prattling on about for ages, it's kind of shocking that in the discussion of the Dinnshenchas, they don't bring in Carey's "Myth and Mythography in Cath Maige Tuired", I have no idea why they're assuming that Bres is a 100% native, indigenous god, and I have no idea how they could get the idea that Elatha conceived Bres as a take-that to Cían and Ethniu....when Lugh was born *during Bres' reign* (Lugh is significantly younger than Bres.)

...now I know where the translation of Bres' name as "Beautiful horseman" comes from. God help us all.

...not to say that they don't know their stuff, since I know that Isolde Carmody has an impressive track record, especially since she translated the Morrígan's rosc while being blind and knows Old Irish, but. Well. To be perfectly honest, I'm disappointed specifically because I know that she knows better.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

While I know all recorded Irish myths are copies written down by Christian monks, but is there much left detailing the indigenous Irish view of the afterlife? Roman records say the continental Celts believed in reincarnation, but is that found anywhere in Irish texts? Thank you!

ehhhhhh so. i have been holding off on answering this one (sorry for the delay) bc this is one of those things where it's really not my area of expertise due to it being too complicated for me to want to wade into unless i really really care (and i am not particularly invested in it as a question, so i steer clear). i did at one point know more about this, because i was at one point more invested, but that was a long time ago, i have memory loss, and i am in a different city from all the books that might be able to help me

so with that caveat out of the way...

the short answer is no -- as far as i am aware there is nothing that unambiguously discusses pre-christian ideas about the afterlife, because christianisation precedes literacy in ireland and therefore everything is filtered through the christian worldview and they're not super interested in writing down things they consider to be heresies, unless they can rationalise it. however sometimes they do manage to rationalise stuff within a christian framework and therefore keep it (such as their attempts to fit the túatha dé danann in by claiming they're 'half-fallen angels' (heresy) or, at other times, demons who deceived people into thinking they were gods)

but by that point it's no longer unambiguous, you see, bc it's been rationalised into a specific framework

i do not think we have any archaeological or historical evidence that we can interpret as telling us anything about how they thought of the afterlife, but this is definitely not my area. i think there is evidence that offerings were left at some of the neolithic burial mounds during the iron age -- it's aaaages since i read up on this, so this is vague, but that suggests either that they're venerating those buried there, or that they've taken on new cosmological/spiritual significance to people who wouldn't know/remember what their original purpose was. which combines with some of the literature to be like "mounds?? afterlife?? otherworld??" (see below)

but like. i recommend reading some archaeologists about that bc i am very much pulling half-remembered info out of a cupboard in the back of my brain and that is not wildly reliable lmao

then the other answer is 'yes but it's literature' so we don't know to what extent it offers any insight into genuine religious practice vs being just a literary construct. there are various stories about ... not reincarnation per se, but people living many lives in many different forms and witnessing large swathes of history as a result. some of this comes up in stories about fintan mac bóchra for example, who was meant to have lived for thousands of years and witnessed a lot of history as a result.

there's also a story about a youth who talks to colum cille, and he talks about all the various things he saw in various different periods where he was different animals. what's interesting about this one is that when colum cille's followers show up, colum cille won't tell them what the youth said, because he doesn't think it's suitable for them to hear -- suggesting it's seen as being in some way incompatible with christianity, so might be implying non-christian beliefs. again, though, this is literature, and idk enough about this text to tell you how likely it is to reflect an oral tradition or a pre-christian belief and how much is like, a later author's ideas about what earlier people might have believed (bearing in mind they had access to a lot of latin texts so might be influenced by what the romans said about celts!)

re: other takes on the afterlife, in a lot of the immrama and echtrae stories (voyage tales, otherworld adventure tales), there's a lot of overlap between the irish otherworld and the christian afterlife, particularly purgatory, and this is the case from very early on. but this sense of confusion about whether the otherworld is for the living or whether it's a world of the dead might relate to people's beliefs about the nature of síd mounds (remember, they're often burial mounds as well as being associated with the otherworld, so it's easy for some slippage to happen there, and see above on archaeological stuff on that). and this shows up right into modern folklore, the 18th and 19th century stuff -- a lot of folklore involves seeing people they thought were dead feasting in the otherworld, and not being able to bring them back to the world of the living etc. again though very unclear how old that is, the christian influences are involved from early on, it's hard to untangle those strands

this is not a particularly detailed or supported answer i'm afraid bc i generally don't focus on those kind of mythological questions. i just find them too slippery and complex and i would prefer to focus on things like "this text says X and that's interesting because Y" because i am just a literary analyst at heart lmao. i get headaches whenever i have to deal with anything too complicated, and these kinds of things usually need to be done in conjunction with, like, archaeology and stuff, and that's something i've never been trained in!

i feel like this might be something mark williams discusses in ireland's immortals, at least in passing, but i am not near my copy so i cannot check

i'm making this non-rebloggable just because i don't feel confident enough in my answer to want it to circulate too widely but if anyone has anything to add, if you tag me in a post i'll edit this to add a link to those additions

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Maybe a video responding to/debunking some of the misinformation out there would draw people in? I'd also watch something along the lines of some of your more bookish blog posts - I always enjoy your thoughts on other people's medieval retellings etc.

Interesting! Thanks. I try to avoid doing anything that seems to be targeting anyone in particular / naming names, so if I were debunking stuff, it would probably only be in general terms. This is mostly because I am deeply conflict-averse and afraid of making enemies, but it does make for less snappy video content – I know the internet thrives on drama and probably if I set myself up to point out what everyone else is doing wrong, I would get more attention. I would rather just give people better-researched alternatives (a positive addition rather than a negative one) but I know that's less popular 😅

To some extent I do already do this – whenever a detail in a text is one that gets misunderstood or misinterpreted often, I'll talk about that and where those misunderstandings come from. But I don't set things up as, like, "five things people get wrong about Óengus" or whatever.

A big part of that is also because a lot of the biggest misinfo I see is related to the more mythological material, but for a lot of people those elements have religious meaning. Many don't mind knowing that aspects of their practice were created by antiquarians or mistranslations in the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries, but some people really, really mind having that pointed out. And it is difficult for me to talk about that stuff from my academic perspective without stepping on people's toes, and either hurting others, or being targeted myself by those angry at things I've said. It's one of the reasons I switched my focus online to the Ulster Cycle, because I got too many aggressive responses to anything I said about the Túatha Dé Danann. Even now, I get the most pushback and negative comments on YouTube whenever I talk about mythological figures, because people perceive my academic, literary approach to the texts to be denigrating their religious/spiritual connection to it.

(Personally, I think people can find spiritual meaning wherever they like, and somebody pointing out what a text actually says is only a threat to that if you are building your faith on unstable foundations in the first place. I am not going to claim that something Victorian is medieval just to spare the feelings of those who would prefer to believe that, but if something Victorian has as much meaning to you as something medieval, then you do you. Just don't get angry at those trying to speak accurately about history and narrative transmission.)

So then when I start trying to directly correct misinformation, it can cause hurt, and it can make me a target. Which is why I try to only do it contextually when it becomes relevant to a specific story. In the past I've still done it clumsily enough to upset people, but I try to be more circumspect about how I approach that kind of thing these days.

Now, if there were lots of low-stakes misinformation out there for me to tackle... but most of that is also, generally, of less interest to people, and arguably ends up being nitpicking after a certain point anyway 😅

My aversion to conflict is related to why I don't talk too much about other people's books. I've done it a little on my blog, as you say, but I only tend to do it when it's a book I enjoyed and when I *liked* what it was doing with medieval material. I'm not a hater. Or rather, I dislike many books and have been disappointed by many retellings, but I will never tell anybody that. Partly because as an author, there's a chance I have mutual friends with that person and it could cause social awkwardness later, and partly because I just don't like putting negative energy out into the world. There's enough of that around.

The trouble is, though, that the books which disappoint or annoy me on that front massively outweigh the ones I love and want to talk about, which *seriously* limits how many blog posts I could write, or videos I could make!

It's one of the things I've noticed about YouTube, and the internet more widely: negative reviews, video essays that pull media apart, and generally critical content immediately reaches a larger audience than purely positive content. I guess because it feeds the drama goblin, and gets rage clicks and outrage, and makes people feel superior if they also did not like the popular thing, but it makes me feel sad. I would rather hear about what people love.

(I also try not to let YouTube duplicate my blog. Making a video takes 10x longer than writing a blog post, so if what I want to say could be said in writing, I will do that instead. I switched to storytelling on YouTube rather than vlogs for this reason; I think there's something about STORIES that benefits from the spoken, conversational element, and reaches people that blog posts wouldn't.)

Anyway, I think my planned "introduction to/beginner's guide to" style videos probably will end up addressing misinformation or misunderstandings in the course of the videos, but they're unlikely to be set up that way. I will think about prioritising topics where I've seen inaccurate info circulating, though, in the hope of countering it!

#i will be honest there is also my impostor syndrome and fear of correcting people incorrectly#which means i hesitate to engage directly with inaccurate media#answered#anon good sir

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just remembered the absolute best plot hook put forward by Scion Pride 2020:

“While non-heterosexual marriage not strictly legal under the existing laws of ancient Ireland the Pantheon is most likely still using, their divine parents and patrons would most likely be happy to extort, bribe, threaten, or argue with whoever they need to to ensure the law is bent and exceptions made on behalf of their Scion. In the case of two men or a nonbinary person being married, no major changes need to be made to the law. However, two women being married is an outstanding story opportunity to showcase the somewhat comedic dramatic tensions resulting from the Túatha Dé Danann’s Virtues. Under standard laws, the groom pays a bride price to their bride to give her financial security, with the value being based on the social status of the bride. If two women were to be married, whichever bride received the higher bride price would evidently be higher status. As the status of a daughter is based on the status of her parents, the parents of the higher status bride are evidently higher status than the parents of the other bride. The amazing story of divine parents demanding increasingly exorbitant prices for their daughter to ensure that they are undoubtedly higher status than their new in-laws and the two exasperated brides-to-be is just waiting to be told.”

I now need a rom-com entirely about this, possibly starring Katie McGrath.

#scion rpg#irish mythology#other fun things about this supplement:#you can make yourself a Scion of Sappho#there's this equally hilarious concept of a trans Welsh Scion being able to sue the universe for putting them in the wrong body#there's rules for Lovesickness#you can get a Kami for a Pride flag#on the subject of pride flags because Ancient Irish Law was very specific about what colours someone could wear#the only thing about queerness the Tuatha are fazed by are pride flags themselves#and the best thing about this supplement is simply that#from an rpg whose 1st edition gave us one of the most transphobic caricatures I've ever seen#several of the actual writers of the actual books teamed up with a load of queer fans to make two and counting books about being queer

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

I know it's probably been forever since you had to think about that particular note but Lugh's not an especially great dad in the Táin Bó Cuailnge. He gets a woman pregnant completely against her will and then puts Cú Chulainn to sleep and carts out a hundred and fifty children to die while his kid's taking a healing power nap. Midir would probably be a better Túatha Dé Danann figure to put in a paternal role.

Noted. I wasn't expecting to get the exact candidates right anyways, just the father pattern.

Addendum:

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

3° Morrigan Morrigan is one of the most important Irish deities, one of the “warrior rages” of Irish myths, goddess of war, death and fate. Morrigan is part of the Túatha Dé Danann, she is the daughter of Fiacha mac Delbaíth and Ernmas and sister of Badb and Macha. She is described as a shapeshifter, who especially likes to assume the shape of a crow, so flies over the battlefields and devours corpses. Sometimes she shows herself as an old woman calling warriors prepare to death. She also occurs as an eel, a red-eared white cow, a gray-red wolf, or a woman or giantess washing bloody clothes near battlefields, and she is able to age or rejuvenate at will too. Her shape-shifting characteristic brings her closer to the figure of the druid as a bard-sorcerer, a role she takes on in some stories, singing songs to bring victory, practicing divination and predicting the future. She is also linked to fertility and sexuality, and some stories attribute to it an insatiable sexual desire; she seduce soldiers before battle, and lead her lovers to victory.

#deitytober#deitytober2020#ckadeitytober2020#prompt list#art challenge#morrigan#celtic myth#celtic mythology#irish myth#irish mythology#folklore#myth#mythology#pagan#paganism#old gods#celtic goddess#celtic god#celtic gods

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hallowe’en - What We Kept from Samhain

What we see today, when Hallowe’en is on the doorstep - or rather about two months earlier in shops - can be summarised in a few words: spiders, pumpkins, scary monster faces, witches’ hats, sweets. Moreover, it is a festival now made for kids. Obviously, because it would make more money than if you targeted adults. If you have read more about Samhain here or elsewhere, you’ll know that this lot sounds veeeeeery much mercantile and far from any Celtic tradition. Indeed, but.

Because there is a but. There is a link, even if people are not aware at all that what they do is deeply rooted in pre-Christian traditions. Let’s have a look.

Obviously, if you ask anyone in the street today about what Hallowe’en means, they’ll answer monsters and sweets and kids. Not a festival for adults. Well, that was not the case back when Samhain was important. It was a festival for everyone because it was New Year, and everything had to be cleaned (physically or financially or whateverally, really), new fires were lit, etc… Sweets can be related to the offerings made to more-or-less malevolent spirits and fairies that night, and monsters can be related to the fact that the culture included a spiritual world not completely separated from the realm of the living, and that Samhain was a liminal period in the year, which would make the two worlds even closer to each other than they would be during the rest of the year. Disguises were already in use at Samhain too, and we’ll see why later.

Monsters & Co.

Barriers between worlds were breachable during Samhain, so offerings were made during the festival to fairies, for instance. The gifts were placed well out of the villages. Fairies weren’t those unsavoury little winged things people have inherited from a Victorian tradition and that Disney-dictatorship has translated into Tinkerbell (though the original book already had her so, but you know how books struggle against other media… ; see picture below). Fairies, or faerie, are supernatural beings or enchanted ones, living in a realm of their own. In Irish myths we have the aos sídh, who are the barrow-dwellers, and also called the faerie. Remember Aillén Mac Madgna? He was a fallen of the Túatha Dé Danann, and was called a fairy, though he burnt Tara every Samhain for twenty-three years until Fionn came and stopped him.

There are some creatures and beings more specifically active at Samhain, and here is a short description of some of them. None of them is really remembered at Hallowe’en, replaced by screaming ghost figures and werewolves.

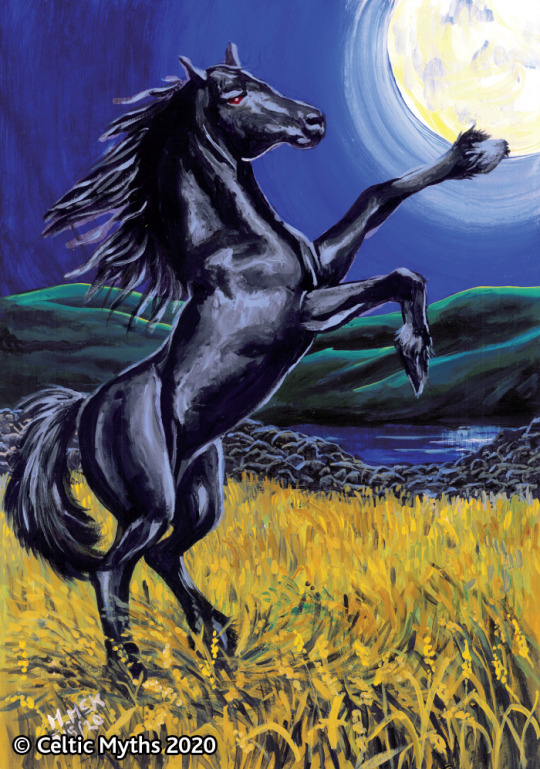

Among the specific creatures associated with Samhain is the púca, a fairy and a shape-shifter. He is said to appear most often in the shape of a black horse (see picture). The púca got offerings from the harvest to keep him checked. Some beliefs are that if the harvest, cattle and foraging is not done before Samhain, the púca will render it all inedible.

Another Samhain-apparition is the Lady Gwyn, who is a headless wanderer-chaser and who’s accompanied by a black pig. Why the heck a pig? At any rate, she is pictured in two different ways according to different sources. Either she’s a good spirit, guarding crossroads and graveyards from other less nice creatures, or her purpose is darker, and she is there to lure the odd wanderer to their doom by asking for help, or offering some glowing treasure.

Then there’s the Dullahan. The Dullahan is a headless rider (male or female, depending on sources), who roams the land in quest of victims (picture below, credit to https://www.theirishplace.com/). He is more prone to appear at some particular festivals, carrying his severed rotting head with him. No gate stays locked before the Dullahan, and anyone spotting him would go blind. The Dullahan can take lives, but, according to some sources, only if he speaks their name, and he can do that only once in his journey. The name spoken will mean death for the bearer, and there is no countercurse. The myth of the Dullahan has survived in many cultures, and for instance in The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, by Washington Irving, published in 1820. It tells the story of a soldier who lost his head during the American War of Independence, and comes back every Hallowe’en to look for it.

Worse or not? - the Sluagh, a creature that steals souls from houses, always flying from the West (so… the Enemy doesn’t always come from the East, does he, Mr Tolkien?). Are those sort of Dementors? Whom do they steal souls from? Dead souls from the family? Or straight from living people? At any rate, ancient tradition says they are faerie gone terribly wrong, fearless and merciless. People would keep their western windows closed tight at all times, for fear of the Sluagh coming for a soul. Some sources say that it is because the Sluagh come out at Samhain that all fires had to be extinguished at that time, so as to avoid detection. Other sources say it was because a year had ended and needed to start afresh. I’d rather back that second one.

Now about the banshee. Aka the Bean Sídhe (picture of the Bunworth Banshee, Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland. 1825). Bean Sídhe actually means woman of the barrow/rath. They were originally graceful and gentle women of the people of Danu (i.e. the Túatha Dé Danann). Today we think about banshees as horrid howling old hags. Actually, Irish mythology tells that the Bean Sídhe can take three forms, one being that of a beautiful woman, one that of an old woman with red eyes, and one that of a red-headed long-haired woman in a white dress. Some sources say Bean Sídhe sings people to their deaths, though most say they foretell whom in the clan will die, and that hearing her keening meant someone in the clan or family would die. They are, in some sources, considered a household fairy, who would be attached to a family and move with them. Myth has it that at first, the Bean Sídhe would keen only for the five foremost Irish families, the only ones being blessed with a lament by one of the faerie, wherever the dying person was. Her cry was the first news of someone snuffing it in the family. Those families were the O’Neills, the O’Briens, the O’Connors, the O’Gradys, and the Kavanaghs.

During Samhain, people also wore disguises. Usually, those were animal skins, along with their heads. And not bunny rabbits. Usually scary animals. The idea was to hide themselves from their deceased relatives who would be able, that night, to come back and visit, since the barriers between the realms would vanish. The disguise would prevent relatives from imposing upon the living, or taking them to the otherworld. Spirits were also believed to leave their barrows/raths to mingle with the living, which would probably be one more reason to hide oneself. Those people were called aos sí (pronounce ‘ees shee’), meaning ‘the people of the hollow hills’ and the raths were the sídh (shee). As barrows go, those were believed to be portals to the otherworld and very prone to opening during Samhain, the most liminal time of year. Remember the story of Fionn against Aillén and the saving of Tara? And again, rings a Tolkien bell? The Barrow Downs (aka Tyrn Gorthad) are exactly that, and Frodo, Sam, Pippin and Merry experience the trouble of meeting the Barrow-Wights on their way to Bree. The Hobbits meet the Barrow-Wights during a foggy morning, which is, as fog goes, a liminal moment in weather: orientation goes haywire, sounds are muffled, nothing is really right.

All Hallows Eve

In the eighth century, Pope Gregory III decided that 1st November would be All Saints Day. That’s yet another example of how a new religion takes hold of what they would call pagan traditions and usually consider a threat to their domination. Using a traditional feast to build a new one (or a sacred location to build another temple) is common throughout history, and has as an aim to assess the power and predominance of the newly come/imposed belief. That is particularly true for monotheistic religions, though in the case of Samhain, it was not completely possible to annihilate the old rituals, but it looks like Christianity had to do with it rather than completely against it. The Day of the Dead is celebrated on 2nd November since it was created by the abbott Odilon at the monastery of Cluny, France, in the 11th century, and is either ‘only’ a way to remember the dead, because they don’t come back in the realm of the living, in Christianity, or is a way of feasting over their coming back for a day, like in Mexico, where traditional and Christian beliefs mingle for that feast.

There was no real way to occult the idea that the realms of the living and the dead would be in closer contact during that time, so the Church had to make do, basically. It is now widely believed that the Church tried to wipe off the important festival of Samhain and replace it with something that it would sanction, as it did with many other celebrations, like for instance Christmas.

About the name of Hallowe’en, though, as feasts tended to start on the evening before the actual day - as they did in Celtic tradition too - the day of All Saintss, i.e. All Hallows, started on All Hallows’ Even, 31st October. Evolution of language made it into Hallowe’en or Halloween. Traditions of disguising and hiding from the otherworld were kept. There are also the lanterns and the sweets… but why?

Why Do We Carve Pumpkins? - Jack o Lanterns

And why Jack? You could ask. Well. They weren’t always pumpkins, to start with. Pumpkins sailed to Europe in the 16th century, so millenia after the beginning of any sort of Samhain festival. At some point in history, people, in addition to using disguises, started to carve root vegetables like turnips into scary faces and place a candle inside, to keep the evil spirits away and with them a bloke called Stingy Jack. Having lanterns was an expensive business, so people used root veggies to the same effect. Later those were replaced by pumpkins, but the idea was the same. Some casts of carved turnips are visible at the National Irish Museum.

So what about that Jack person? That is a tale that comes after Christianity had overtaken Ireland. It goes like so: Stingy Jack was a penniless drunkard, who liked roaming the roads at night. One such night, he came upon a body with a twisted face on the road. Thinking it was his end at last and that Death had come for him in the shape of Satan. Not willing to depart this world without a last sip, he asked the devil to come and have a drink with him at the pub. They went. After a few pints, it was time to pay, and true to his name, Jack asked the devil to cough up, because he was skint. The devil was too. Jack told the devil: ‘Turn into a coin so I can pay and then you turn back into yourself whenever the bartender is not watching.’ So the devil, acknowledging the level of trickery in Jack, turns into a coin. Jack, trickster among the tricksters, decides not to pay but to pocket the coin and go. Trouble is, in his pocket was also a crucifix, meaning that the devil was basically at Jack’s mercy. You can imagine that Satan wasn’t very happy with the arrangements. He asked Jack to free him, but Jack bartered with the devil: ten years to let him go. And Satan agreed. What were ten years for an immortal thing like him?

Ten years later, the same scene repeated: Jack stumbled upon Satan on the road and the devil told him it was the moment to fulfill his part of the bargain. Jack, true to himself, asked for an apple to feed his empty stomach. Satan - he was really daft - didn’t see the trick, and climbed up an apple tree to get what Jack asked. Meanwhile, Jack carved a cross into the trunk, and Satan couldn’t get down. Asking for his release, the devil heard a second demand from Jack: ‘I’ll let you down if you promise never to take my soul to Hell.’ To which the devil agreed, frustrated to have been outwitted once more.

Eventually, Jack died. He arrived at the gates of Heaven, but was rebuked and sent to try his luck in Hell. Arriving in Hell, Satan, keeping his promise to Jack, didn’t take his soul in. And Jack was then left to roam the limbo with an ember inside a hollowed turnip for light.

That’s how we have turnips and now pumpkins at Hallowe’en. Naturally, this story has many versions, and the number of years allowed to Jack and the ways the crosses are used change from one story to the next. However, he always meets the devil twice and is denied entrance to both Heaven and Hell, and wanders the Earth with a turnip lantern. The Irish first called him Jack-of-the-Lantern, which soon shortened into Jack-o’-Lantern.

How Come Hallowe’en Is a United-Statesian Affair?

I’m not speaking of Dias De Muertos, which is a Mexican festival that is, though related, completely different, mostly because it has a way more religious connotation than Hallowe’en (which has none).

If we look back at the US history of immigration from Europe, it is quite obvious that Hallowe’en cannot have travelled there via the so-called first settlers, because of their rigid protestant laws. The celebration of some sort of yearly festival seems to have started in the southern colonies, by the telling of ghost stories, and pranking, maybe to remember the púca and other pranksters from Irish folklore? Nothing really widespread happened before the great waves of immigration of the 19th century, when a massive arrival of Irish settlers fleeing the Potato Famine brought Hallowe’en with them. Before the 19th century waves of immigration arrived, there was a move to change the prank-and-witches feast into something more neighbourly, more community-centered. By the mid-19th century, the feasts had become more centered on games, food and festive costuming, trying to remove anything frightening or grotesque from the feast (quite intriguing, given that it was also the boom of the gothic movement). The consequence was that by the 20th century, Hallowe’en was basically a garden-party/town parade business. The 1950s baby boom meant more children, and the parties moved to classrooms and homes, and were more directly designed for younger humans. The trick-and-treating was also revived, and giving out sweets was a relatively cheap way to avoid getting pranked. Obviously, this can be related to the tradition of making offerings to faerie and getting disguised to avoid recognition by malevolent spirits, but it has come a long way from Celtic Ireland to this.

Today, Hallowe’en is a huge commercial event: for instance, 25% of all sweets bought yearly in the USA are bought for Hallowe’en. Europe had not been touched a lot by this wave until recently, but there are not really parties or trick-or-treaters on continental Europe. They are a thing on the British Isles, obviously, but I reckon the US version of Hallowe’en has taken over the traditional one. There are sort of revivals of new fires and traditions, of course, but they are marginal compared to the mercantilism of today’s Hallowe’en.

How it happens in the Harry Potter books

There is not much in the Harry Potter series about Hallowe’en, but it is a time of danger and a turning point in the story, usually, because weird things happen that shouldn’t be happening: Lily and James Potter die at the hand of Voldemort, and Harry survives; Quirrell makes the Troll enter Hogwarts in Philosopher’s Stone; Nearly Headless Nick’s Deathday is on Hallowe’en, and famously, Harry, Ron and Hermione attend his 500th Deathday party in Chamber of Secrets, and it was on the same day that the Chamber of Secrets was opened for the first time after fifty years, and the Basilisk Petrified its first victim, Mrs Norris; in Prisoner of Azkaban, Sirius Black enters Hogwarts on Hallowe’en, frightening the Fat Lady who must be replaced by Sir Cadogan for a while; in Goblet of Fire, the Triwizard Cup is launched and Harry chosen as fourth champion.

Besides, as Harry and Neville were born on 30th/31st July, it is likely they were conceived on or around Hallowe’en the year before.

So Hallowe’en is an important date, because in the first four books something central to the plot happens. However, in terms of links with Samhain, there is practically nothing. Is it because the lore in the Wizarding World is already rich enough? Because no kind of religious reference was wanted there, be it ‘pagan’ or not? Pumpkins and live bats are the only references to any kind of tradition in the books.

Everyone can make their own idea about how they want (or don’t want) to celebrate Samhain or Hallowe’en. I separate the two because now that I've learnt a bit about Samhain, it is impossible to relate it completely to the 21st century version of Hallowe’en. However, I hope you enjoyed this trip throughout cultures and history. I did.

Sources

Online Sources:

http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/celtic/jce/beansidhe.html

https://brewminate.com/samhain-the-celtic-inspiration-for-modern-halloween/

Text of the Second Battle of Mag Tuired: https://celt.ucc.ie//published/T300010/index.html

https://celticmke.com/CelticMKE-Blog/Samhain-Tlachtga.htm

http://fermoyireland.50megs.com/bansheestory.htm

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow - text: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/41/41-h/41-h.htm

https://www.history.com/topics/halloween/history-of-halloween

https://www.knowth.com/the-celts.htm

https://thefadingyear.wordpress.com/2016/11/01/the-puca-and-blackberries-after-halloween/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/paganism/holydays/samhain.shtml

https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/zbkdcqt

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Samhain

https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/courses/13things/7448.html

https://www.theirishplace.com/heritage/the-dullahan/

https://www.history.com/topics/holidays/samhain

https://www2.nau.edu/~gaud/bio300w/frsl.htm

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/when-people-carved-turnips-instead-of-pumpkins-for-halloween-180978922/

Bookses and Papers

Farrar, J., Farrar, S., & Bone, G. (2001). The Complete Dictionary of European Gods and Goddesses. Capall Bann Publishing, Berks, UK.

Harari, Y. N. (2014). Sapiens: A brief history of humankind. Random House.

Johnson, P. (2008). The Little People of the British Isles - Pixies, Brownies, Sprites, and Other Rare Fauna. Wooden Books, Glastonbury, UK.

MacKillop, J. (2006). Myths and Legends of the Celts. Penguin UK.

Meuleau, M. (2004). Les Celtes en Europe. Ed. Ouest-France.

Rees, A., & Rees, B. (1991). Celtic Heritage: Ancient Tradition in Ireland and Wales. 1961. Reprint.

Rowling, J. K. (1997). Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Bloomsbury, London.

Rowling, J. K. (1998). Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, Bloomsbury, London.

Rowling, J. K. (1999). Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Bloomsbury, London.

Rowling, J. K. (2000). Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Bloomsbury, London.

Rowling, J. K. (2007). Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. Bloomsbury, London.

#Halloween#Samhain#Stingy Jack#Púca#theDullahan#Bean Sídhe#banshee queen#Turnip#Pumpkin#HarryPotter#j.k. rowling#Hogwarts#Louhi

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lore || Druidic magic

A New God arrived in Inis na bhfiodhbhadh, the Island of woods, as pirates brought to the Irish shores Maewyin Succat, later known as Patrick, and as years later Naomh Breandán sailed to the Isle of the Blessed. For people now would follow the lesson of the shamrock, and believed in the Trinity who defeated evil; for people would follow those who bore the sign of the cross and the sun. (Stolen, stolen!) And it is said that Danu, mother of all, cried with all her might and anger as her lands were conquered, as people forgot her name, as the land withered and the rivers ran dry - when magic left the green soil like water evaporating under the scorching sun. Hunted down and exiled, the people of Ériu fled to the woodlands and wilderness, their dominion left untouched by the New God. There, the Old Faith in the Gods of old still lived in secrecy. And magic was hidden from the world.

“Stepbrother tell me where have you been when they brought me to this godforsaken place. Sign of the cross - they took me away for healing with herbs by the way of grace. Now I wait for the day to feed the flames.”

Druidic magic may be one of the primordial forms of magic, deeply connected with nature and natural elements in general, as a spiritual bond. Legends say the Túatha Dé Danann and the Fomorians, both rivals and allies, gifted the worthy humans (the Milesians) with knowledge and skills - about the earth and the sky and seas and the realm of animals and all the world above, as the sons of Danu took the world below (the Otherworld) never to be seen again in the Isle of Emerald. This kind of magic can be performed only by Druids, members of the high-ranking class in ancient Celtic cultures: they were religious leaders, legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals, and political advisors. They were the chosen ones, holding power in the different clans, acting as chiefs, when needed, and priests.

Druidic magic consists in the control and manipulation of the power of nature, and, of course, it draws upon nature-related magical energies - for this very reason druids and natural elements share this special bond, and druids are not allowed to abuse such powers and spell. it usually manifests itself with a green/jade glow radiating from the hands and the eyes, and as the magic gets stronger, it may design an intricate pattern on the skin, resembling thorns and leaves crawling from their hands, along their arms and shoulders and neck. The longer a druid may use its powers, the more these signs would burn on the skin and hurt.

Druids can control animals, first of all, and understand them - even speak with them. Usually, a druid has a familiar - not a servant, but a friend who faithfully follows the druid. They can also turn into an animal, with no need to be an animagus, a technique knows as shapeshift. They have a peculiar affinity with the world of plants and herbs, the forest being one of their dominions: druids can speak with plants and understand them as if they were animals or humans. They will never lose their path in a forest, and the forest will provide them for a way out of a refuge is the druid so required, and even keep trapped enemies - its also way easier for them to survey the area and feel whether an enemy is near or not: druids’ senses are more efficient in their favored terrain Druids can animate plants, a really effective way to also fight: they can make roots sprout from the ground, vines and thorns lash out at the offender and trap them or keep them still. Another way to defend themselves is also turning their skin into hard bark, to make their skin more resistant to wounds. Their knowledge about plants and herb is shown also in their great abilities with herbology and potions, making druids great potioneers and healers. Strongest druids can control earth, creating earthquakes.

Being able to control the natural elements, they can control waters as well. They can summon fogs and clouds and a soft rain or snow, but cannot invoke a drought or a storm. Hail can be summoned whether a storm is happening. They can also control the flow of a stream, making it quicker or slower, and can make the water freeze or evaporate. Druids can also summon water directly from steam. A way to attack using water powers is summoning waters jets that can hit the enemy, and they can defend themselves using a shield of water if they are, in fact, near a body of water.

Air is another element druids can control: warmth or cold, they can slightly change the weather and the atmosphere, always in their range of powers, which can never overcome nature. They can summon winds to bring clouds and rain, or soft gusts or air.

Fire is the hardest element to control. They can light small flames (such as candles) from afar just with their gaze, or produce a flickering flame appearing in their hands that does not burn their skin. In front of a fire, they can make it stronger or weaker or shape its flame (as a wall) but never extinguish it. it’s also really easy for a Druid to see faeries’ fires, one of the few ways the spirits of old have to communicate with them.

Control over life and death of “nature” is allowed, but druids must be careful: they are not allowed to overcome nature’s boundaries.

“Rose Red, white as snow, queen of forest and clover, I gave you my heart, Rose Red, therefore become my bride.”

Seers and berserkers may be part of Aisling’s ancestry, but an important part of her heritage also belongs to the druids. Druids could use magic thanks to their connection with nature, and in the O’Broin clan (the maternal side of Aisling’s family) this trait passed from generation to generation: Aisling showed her powers when she was still a newborn as she tried to reach for a red rose and made it bloom instantly as she grasped it, no thorn would hurt nor scratch her skin.

Aisling, not being a pureblood druid, may not have access to all druidic magic’s powers.

First of all, her bond with animals is not as strong: she may feel their emotions and understand their needs feebly, but, in order to achieve the ability to turn into an animal, she had to become an animagus, while her mother can turn into a wolf (one of the sacred animals of The Morrigan) without the typical animagus’ abilities. This magic also allows Aisling to better understand her surroundings, thus she will never lose her way inside a forest. Moreover, the forest is her favored terrain, where she can hide if she wishes to. She has a good control over plants too, and make them grow and die as she wishes: this powers are easily manipulated by Aisling’s emotions, for plants could grow and bloom whenever she feels happy, but on the other hand, when she is sad, her emotions can make plants wither. She can make small plants move - even calm the Whomping Willow a bit but not fully control it. Aisling is pretty much efficient at dueling with her druidic abilities: she is able to conjure grasping vines sprouting from the ground, and direct the vines to lash out at something/someone, she can summon root to slow down her enemies and to keep them trapped. The full potential of this power can be really dangerous, even deadly, just imagine how easily she could strangle a person.

Aisling also has an affinity with water and air as well: she can control small streams and create a light fog and summon clouds. In this case too her mood can summon a light rain and winds. In the realm of fire, Aisling’s powers are not strong: it’s easier for her to detect faerie’s fires but she cannot control flames or produce fire - only weaken flames with gusts of air she can summon.

[ DISCLAIMER: this does not want, by all means, to mirror the reality of Celtic culture throughout history, which I know as well. As part of a -more or less- fantasy world, I gave myself the chance to create something. Also, I went for a simpler version of Irish mythology, I think we all agree this is not supposed to be an essay but just some general guide. ]

[ DISCLAIMER 2 = this is a work in progress, I may change things from time to time. ]

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dio Celtico delle guarigione, della caccia, dei cani e del mare, Nodens nella mitologia Irlandese potrebbe riferire a Nuada, primo re Túatha Dé Danann, in quella gallese a Nudd.Nonostante qualcuno lo abbia assimilato a figure mitologiche classiche, per esempio Marte e Mercurio, ma anche ad Ascalepio, Nodens sembra essere un dio Britannico vero e proprio e non esistono sue rappresentazioni in forma umana. Al contrario, numerose statue di cani che lo rappresentano sono state trovate nei suoi siti di culto anche se gli storici sono indecisi se esse rappresentino il dio stesso o il suo animale. Il luogo di culto per eccellenza di Nodens è il complesso di Lydney Park situato tra Gloucester e Gloucester nella Foresta di Dean, in Inghilterra. Altri centri di culto erano a Cockersand Moss nel Lancashire, a Vindolanda, sul Vallo di Adriano, a Magonza in Germania. Maynooth, una città a nord della Contea di Kildare in Irlanda, è un'anglicizzazione di Magh Nuad, "Piana di Nuadu".

altre immagini qui: https://www.twogreyhounds.com/2020/06/15/nodens/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Celts in Pop-Culture: Extra Mythology, Part #1

So, in a likely feeble attempt to ward off the slowly crawling insanity and self-doubt fueled primordial terror of an Old Irish exam today, I have decided to spend this evening doing something I have been promising to do for months now: discuss the Extra Mythology video titled: ‘Celtic Myth: the Island of Destiny.’

Now, before I get into the specifics, I would like to preface this discussion with the fact that I did reach out to the people behind this project and let them know there were issues with the material and offered my assistance to revising or helping provide research for a corrections video if it was of interest to themselves. I was informed that they were drawing on the works of Peter Berresford Ellis, a journalist who is very notably not a trained Celticist, and were comfortable with their choice as it showed the variation in the stories, and that I would look forward to the corrections episode. As it has now been eleven months since the initial video’s publication and no correction video has arrived, I want to start my commentary on it.

Oh, and before we begin, thanks to Thrythlind for transcribing this video and the next one so I can comment on them more easily.

Now, the issue with the version of events presented by Extra Mythology, drawing on Ellis, is that it is primarily absolutely totally and factually made up. Which, you know, bad start. But, lets start in the big picture and then break it down. The events described in this text are a segment of Lebor Gabála Érenn, the ‘Book of the Taking of Ireland,’ (henceforth LGE) and Cath Maige Tuired, the ‘Battle of Mag Tuired.’ (henceforth CMT) These are two exceptionally interesting texts, and a great place to start when introducing someone to Irish saga material as Extra Mythology intended to do! However, there is a large problem: the version of events told by Extra Mythology is only loosely based in these texts.

As you can see here and here, there is not actually a tremendous amount of variation between the extant versions of these two stories. LGE has four medieval versions, each of which I have had the pleasure to read (and you can too! Volumes 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5!) and CMT has one medieval version which is one of my favorite texts. I highly suggest reading it, and you can find it here.

So, as we can see, right off the bat we are not dealing with a huge amount of variant texts with a bunch of differences. In fact, there are very few versions of LGE that are very consistent in this relevant section, and CMT has no variants. (There is a Early Modern version, but nobody has ever translated it... or really worked on it. Or done anything with it.) So, I would like to initially begin by pointing out that while Extra Mythology has explained to me that they chose this version of the text to show the different versions, there are none, and the version they used does in fact offer alternatives that are not authentic, not medieval, and made up by Ellis.

Now, to begin.

Void became form and form became Earth and out of the Earth sprang a tree. It was the mighty oak, watered by the river of Heaven, the Danu. And from that oak fell two acorns from which sprang the first of the gods: The Dagda and Brigid. They were the first children of the Danu. And over time the Children of the Danu grew and built four great cities on the banks of the sacred river.

Well, that’s all fictional. The ‘Creation of the World’ for Irish mythology is the Book of Genesis, these myths (if we can call them that, see: Ireland’s Immortals by Mark Williams) are set within a Christian world and a broader Christian cosmology. There is no tree, there is no ‘river of heaven’ named Danu since Danu is a person, in theory (as we never see her ‘on screen’ and might even be dead before the events of these stories), and there is certainly no gods coming out of acorns. And the Four Cities are on islands to the north of Ireland, they are not built along a sacred river.

Now! Where is this coming from? I presume this is Ellis trying to connect Danu, the ancestral figure of the Túatha Dé Danann with the Danube River in Germany which might have a linguistic connection, but no evidence to exists to suggest they were believed to be connected by the time of LGE.

Those cities flourished and in each of them was crafted a great artifact. In one was the Stone of Destiny which would shout with joy when a righteous ruler set his foot upon it. In another was Retaliator, the greatest sword ever forged. In the third could be found the Red Javelin which once thrown would find its mark no matter how its foes hid. And, finally, in the fourth city, lay the Cauldron of Plenty which could feed all the Children of the Danu and still never empty.

Now, this section is rather interesting as it is getting some things correct and then absolutely dropping the ball elsewhere. Let us compare this statement with the actual text of CMT where this description of the Four Treasures of the Túatha Dé Danann are named and described! (Using quotation marks to make it less confusing than if I used block-quotes for both the video and original texts)

“From Falias was brought the Stone of Fál which was located in Tara. It used to cry out beneath every king that would take Ireland. From Gorias was brought the spear which Lug had. No battle was ever sustained against it, or against the man who held it in his hand. From Findias was brought the sword of Núadu. No one ever escaped from it once it was drawn from its deadly sheath, and no one could resist it. From Murias was brought the Dagda's cauldron. No company ever went away from it unsatisfied.“

So, what is wrong here? Well, most of it. Lets go treasure by treasure.

The Stone: Extra Mythology claims that the stone would shout when ‘a righteous ruler set his foot upon it’ where as the actual text says it would make a noise when ‘beneath every king that would take Ireland.’ There is zero moral judgement here, the rock is just a prophecy stone that says when someone will be King of all Ireland. Very different.

The Spear: Extra Mythology calls this the ‘Red Javelin’ which is a name I have never heard before, and claims that the spear is unerring. In reality, the spear is just described as the spear that Lug had, and its function is far cooler in that battles cannot be won against the wielder. Pretty.... massive difference to tell the truth. (I think Extra Mythology via Ellis is talking about The Lúin, a colossal spear that distorts reality to always hit and always kill from an entirely different story)

The Sword: Extra Mythology claims the sword is named ‘Retaliator’ and it was simply the greatest sword forged. The reality describes this as the Sword of Núadu (who Extra Mythology will call Nuada) and that no one ever escaped from it, and no one could resist it when drawn. Vague, but way more detailed than what Ellis has informed Extra Mythology with. Furthermore, ‘Retaliator’ is a different sword, one named Fragarach (translated as Retaliator) which is Manannán mac Lir’s sword which can command the wind, cut through any armour, and will always kill someone it wounds. Super weird call there.

The Cauldron: Extra Mythology presents this as ‘The Cauldron of Plenty’ and that it can feed all of the Children of Danu. The reality just calls it The Dagda’s cauldron and that ‘no company ever went away from it unsatisfied’ which probably sounds very similar, but the difference is important. In a culture with such heavy emphasis on feeding and hosting as medieval Ireland, the importance I would put here is not just on the cauldron’s ability to feed everyone, but to satisfy everyone. There won’t be honour arguments over who got better food, there won’t be violence over issues of disparity, everyone will be satisfied and the host’s duty will be completed.

So, they got the treasures wrong. In fact, they just subbed out two of them for totally different magical items from different Irish sagas, and then sort of misrepresented the other two. Anyways, continuing.

But one day, The Dagda called the greatest of his children from all the cities and told them of their destiny. For it was not for them to remain by the sacred river Danu but to head to an island where the sun set. Before they went, though, Brigid offered them a warning. They would not be alone on this island. Others would try to make it theirs. With this warning, the Children of the Danu set out for their new home. Bringing with them their four great treasures for protection. Unsure of what they'd find on this Island of Destiny. Or so some say.

None of this happens,the only person who says this is Ellis I presume as it is not at all found in any of the medieval texts. We never get an explanation of why the Túatha Dé leave the Four Cities for Ireland, never gets explained.

Some say they came in a dark cloud from origins unknown and alighted on a mountaintop. Others still say they came from strange cities across the sea. Where they learned science and magical arts and when they arrived they burnt their ships behind them. Wagering all on the conquest of Ireland.

Oh, this is true! Our first factual bits of information here. So, yes, the variation here is actually mentioned in texts! That either the Túatha Dé arrived in ships of mist, or that this was just people misunderstanding that they had burned their ships when they arrived. Though, in both versions they still come from The Four Cities.

As they started to explore the misty plains of Inis Vale they encountered a curious people already living there: the Fir Bolg.

Also known as: relatives of the Túatha Dé Danann, and also the native people of Ireland at this time. So, the Túatha Dé have arrived, and found a bunch of native people living in the island they want, I am sure they will be very polite and get along well. Yeah? Well no, of course not, the Túatha Dé Danann are conquering colonizers, they’re not good people.

The Danu asked for half of Ireland to be theirs to settle and they could live in peace. But the Fir Bolg refused so battle was decided upon.

Firstly, ‘the Danu’? No. That would be like calling the Romans ‘The Romulus.’ Secondly, the Túatha Dé demanded half of Ireland from the Fir Bolg who, understandably, were not entirely okay with just giving up half of their land no questions asked to a foreign bunch of randoms who just rolled up and burned their ships.

LGE says, “They demanded battle or kingship of the Fir Bolg. A battle was fought between them, to wit the first battle of Mag Tuired” which if I am reading this correctly is consistant through the versions. So! The Túatha Dé rolled up, went ‘we demand either that we are in charge of you all [and your lands] or fight us about it.’ Very different.

But just to be clear, battle back then was a lot different to the way we think of it now. This was a matter of honor. The Children of the Danu made spears for the Fir Bolg to use. And the Fir Bolg crafted javelins for the Children of the Danu. They agreed on how many soldiers each side would bring. And where they would do battle. They even agreed on how many days they would fight for.

This is a weird misunderstanding or misrepresentation of the facts. Bres mac Elatha and Sreng meet each other and exchange the demands for Ireland, and then exchange spears with each other in a very homoerotic scene after handling and inspecting each other’s spears.

At this point we start getting into a long description of a battle which I’m going to pick specific things out of to discuss rather than going word for word.

Until the leaders of both sides, Nuada of the Children of the Danu and Sreng for the Fir Bolg, met in the center of the melee.

Sreng is the champion of the current high king of the Fir Bolg at the time, he isn’t the leader of the Fir Bolg. The Fir Bolg king at this time was Eochaid mac Erc.

Then, Sreng landed a titanic strike. His blade cleft through Nuada's shield and severed his right arm in one stroke. Nuada stumbled back, dazed. It looked as though the end had come. Then The Dagda himself intervened and spirited Nuada away.

Yes, Sreng cuts off Nuadu’s hand (or arm. Lám in Old Irish could mean either), but The Dagda isn’t even mentioned in this scene. That’s a super weird detail for Ellis (presumably it was him and not Extra Mythology) to make up.

They took him to Dian Cecht; God of Healing, Lord of Physicians; who crafted him a new arm of pure silver that moved like an arm of flesh and blood.

Also Creidne the smith. Everyone always forgets Creidne and I won’t stand for it.

Now you might think that the Children of the Danu would have quavered at the sight of their leader fallen in front of them. That they would break as their king was smote by the Fir Bolg champion. But, no, Bres, Warrior of the Danu, quick of mind and beautiful of form seized the king's right arm and raised it aloft. Angered by such a sight, the Children of the Danu swore vengeance. And plunged into the Fir Bolg ranks.

This is literally all fictional and I have no idea why Ellis would even make this up.

Finally, the Fir Bolg were all but defeated. 300 Fir Bolg warriors remained. Led by Sreng, their great champion. They took counsel and decided to fight to the last.

So this is sort of weird a) because we are glossing over the fact that in this version the Túatha Dé have essentially committed genocide here, and b) because other Fir Bolg escape this battle.

They quickly chose Bres as their leader for his valor and charm of mind.

So firstly, we don’t mention that now we are dealing with an entirely different text? Well, okay. And also sadly CMT is more misogynistic than this as CMT explains: “There was contention regarding the sovereignty of the men of Ireland between the Túatha Dé and their wives, since Núadu was not eligible for kingship after his hand had been cut off. They said that it would be appropriate for them to give the kingship to Bres the son of Elatha, to their own adopted son, and that giving him the kingship would knit the Fomorians' alliance with them, since his father Elatha mac Delbaith was king of the Fomoire.”

So, bit more complicated and has inter-tribal strife along gendered lines in reality.

But Bres was half Fomorian, a name we've not heard tell of yet in this tale. But we soon will. In his rule he acted more as a Fomorian than as one of the Danu. But, the reign of Bres and the war against the ancient and strange Fomorians is a story for next time.

Okay, again, still, ‘the Danu’ just catches my ear and confuses me every time. Bres has come up in this story before and is an entirely reasonable person, and like, most of the Túatha Dé big-names are part Fomorian. The Dagda, Nuadu, and Ogma are all Bres’ brothers and also sons of Elatha of the Fomori. And, ‘acted more as a Fomorian than as one of the Danu’ is just such a loaded statement. Yes, the Fomorians are raiding slavers who exploit less powerful tribal groups for personal wealth. The Túatha Dé are, shockingly, raiding slavers who exploit less powerful tribal groups and we have just seen them slaughter the indiginous population of Ireland and regulate them to a small portion of their original land. There is no moral connection here, the Fomorians and the Túatha Dé are just supernatural peoples hanging out in Ireland. One isn’t good and one isn’t bad.

Anyways, that’s the end of the first of two videos put out on this. Hopefully I shall do the next one this weekend.

In conclusion, what we see here is just a very strange misrepresentation of the events of LGE and a bit of CMT. Entire scenes are made up, ‘the Danu’ as a sacred river is... absolute nonsense. The idea of a world tree and gods born from acorns is fictional. So much of this is just fictional, an outright lie, or very misleadingly represented that I really cannot recommend this as an introduction to medieval Irish saga literature. I am disappointed that so little care or research was put into this by the Extra Mythology series, where when the original texts are available for free and in translation they instead chose a fictional version of the story made up by a journalist. It is incredibly irresponsible in the least, especially that when contacted the concerns on the accuracy and validity of the story they had told to their audience was brushed away.

Oh well, on to the second half of this story.

#extra mythology#irish mythology#celtic mythology#celtic myth#irish myth#celtic studies#mythology#túatha dé danann

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

WELCOME TO IL-GENNA!

"You find a plane ticket in your mail. It first sounds sketchy, but the moment you read the handwritten letter by TÚATHA DÉ DANANN, a mega corporation and founder of Il-Genna, you realize that your eternal vacation is indeed waiting for you."

TÚATHA DÉ DANANN is a panfandom discord mfrp. Enjoy your eternal vacation in Il-Genna, befriend new people, join a guild, and learn a new job!

✦ active community ✦ 15 character slots (+possibilty to get more!) ✦ est. august 2023 ✦ neurodivergent friendly! ✦ friendly mod team! ✦ story arcs + extending lore!

RULES ✦ PREMISE ✦ ROSTER ✦ DISCORD SERVER

#manga rp#discord rp group#discord rp#anime rp#discord mfrp#multifandom rp#panfandom mfrp#panfandom rp#animated mfrp#anime mfrp

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I've actually read a theory that claimed Cu Chulainn was originally a thunder god. The theory came about because Cu Chulainn's weapon and various attacks contain the word "thunder" like "thunder bolt" or "thunder strike." I'm not saying they're right but I'm curious about what you think.

my gut reaction, based on nothing at all, is to say “nahhhh, that just sounds like someone trying to draw parallels to other literature like norse stuff and looking for connections there so that they can try and make these figures fit their idea of a pantheon”, but that’s based entirely on a gut reaction and also my general reluctance to even consider cú chulainn as a god, because, like... he’s never presented as a god in irish lit. and how they present gods is pretty nebulous and vague anyway, but while he’s got a number of connections to the túatha dé danann and does various bits of magic, he’s not really considered to be one of them. he’s just a dubiously human weirdo with a lot of otherworldly friends.

but like even with the people who are almost certainly actual gods (in the literature at least; that tells us nothing about history/religion), they’re not really gods of stuff. they’re gods who are good at stuff but it’s not... a pantheon? you can’t be like “this person is the god of [x] and that person is the god of [y]”, that’s just not how it works in irish lit. trying to fit them into that kind of paradigm is often just, as gantz put it, pinning roman tails on a celtic donkey.

so as well as not thinking of cú chulainn as a god, i also wouldn’t ever say that an irish figure is a “thunder god” or a “love god” (preserve me from victorian ideas about aengus) or a “sun god” (noooooo). some would but.... i would not be one of them, and neither would very few academics writing in the past few decades.

[while you’re here, i’d highly recommend ireland’s immortals: a history of the gods of irish myth by mark williams. like i can’t stress this enough. if you want to know about the mythological side of things, that’s probably the best book to start with because it’s academic yet accessible, and more importantly, it’s recent. a LOT has changed in celtic studies as a field in the last 50 years yet it often feels like most people i encounter online haven’t read anything more recent than, like, the 40s. at best. which is Not Great. that book came out in late 2016, so actually reflects the current state of the field/discipline based on what we now know about the texts we’re working with and whatever]

but i figured i’d go look for those thunder references just to see if there’s anything in it beyond that, even though it’s like... nearly 1am and i should be in bed. i make bad life choices. hey, kids, don’t do irish lit.

soooooo.... i mean it’s really hard to translate any of the names for the feats he performs and most of them don’t make a lot of sense but i’ve never really noticed a thunder theme? he has his salmon leap, that’s one of the most famous ones.... that’s a fish. like, here’s the list of feats from recension 1 of the táin, translated by cecile o’rahilly (bearing in mind they’re hard to translate)

The ball-feat, the blade-feat, the feat with horizontally-held shield, the javelin-feat, the rope-feat, the feat with the body, the cat-feat, the hero's salmon-leap, the cast of a wand, the leap across ..., the bending of a valiant hero, the feat of the gae bolga, the feat of quickness (?), the wheel-feat, the eight-men feat, the overbreath feat, the bruising with a sword, the hero's war-cry, the well-measured blow, the return-stroke, the mounting on a spear and straightening the body on its point, with the bond of a valiant champion.

there’s nothing about thunder there? they’re most about weapons or movement and where there’s a theme at all, if anything it’s an animal theme, like the cat-feat and the salmon-leap. in the wooing of emer you get

the spear-feat, and the apple-feat, and the sword-edge feat.

so now we’ve got apples as well as weapons

like there’s one reference in R1 that could be relevant, where it says “the thunder-feat of the two warriors in the ford”, but it’s also talking about how noisy they are in the same paragraph, and anyway that would theoretically make them both thunder gods really, it’s not unique to CC

and there’s a couple of references to thunder in R2 as well, like when CC is approaching fer diad and his charioteer in his chariot, but again it just seems to be referencing noise, not directly comparing to thunder (and that’s just the english translation, it’s way too late at night to go looking for the irish right now). and at one point it says he runs as swift as a thunderbolt? but then you go to the muster of the ulaid towards the end and like... half the ulaid are compared to thunder in terms of the noise they’re making as they gather, so it really doesn’t seem like it’s a unique feature of him, that’s just the kind of noise that happens when you get a ton of angry men in one place with their weapons

so idk tbh as a proposition it seems decidedly sketchy to me and based on very little actual textual evidence. like... the feats are hard to translate, i think i’d be wary of anyone saying with too much certainty that they all mean stuff to do with thunder, or whatever, and any references i’ve found to thunder seem very much in keeping with how warriors in general are described, rather than being some unique trait of cú chulainn’s. but also... like, sure, cú chulainn for sure isn’t 100% human, but i would very much hesitate to classify him as a god of any variety, and even if i did, i wouldn’t start trying to pantheon anyone

disclaimer: it’s 00:50am and i had never encountered this theory before 00:26am today so this isn’t exactly the most academic and well-researched answer in the world but whatevs

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! If it's no bother asking, I am a bit confused as to who was in Ireland first (Fomorians, Fir Bolg, Tuatha Dé Danann) and I was wondering if you could help explain it? I am trying to write a story based on Irish myths and this topic fascinates me as much as it confuses me 😅

Hello!

I think it goes in the order you listed in your ask -- certainly the Túatha Dé Danann defeat the Fir Bolg, but are later defeated themselves. The Fomoire aren’t generally listed as one of the groups of invaders/settlers because they’re the “bad” guys, but exactly when they turned up I’m not sure, as it’s not an area I’ve looked too closely at myself (being more an Ulster Cycle / Finn Cycle kind of person).

The story you want here is Lebor Gabála Érenn (the Book of Invasions). You can find it here; be aware that it’s pretty long and is in several parts as a result. This is... largely why I haven’t looked at it in too much depth. I’m still waiting for someone to come out with a modern, single-volume translation of it, because I’m lazy 😂

You might also want to read Cath Maige Tuired (which, thankfully, is shorter!), and if you want to talk to someone about that in more depth, I’d recommend @wildandwhirlingprinterfucker who knows more about it than virtually anyone else I know and has Very Strong Opinions about it (... dubious username aside).

If you’re looking for a solid, accessible, academic book about the Túatha Dé Danann -- who they are, what they’re doing, and how they’ve become what they are in pop culture and modern literature -- then you can’t go wrong with Ireland’s Immortals: A History of the Gods of Irish Myth by Mark Williams.

Hope this helps!

20 notes

·

View notes