#such that students get algebra 1 in eighth grade

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Me: okay time to read this "math wars" article my professor sent me

Me now that I have gone down the rabbit hole to understand the proposed math framework in California: I am ready to commit crimes

#it's SO BAD#so bad!!!!!#KIDS NEED PROCEDURAL FLUENCY!!!!!!#EVERYONE NEEDS PROCEDURAL FLUENCY#isabel.tex#school#also this math professor is right: the best way to make calculus more accessible is to improve/adjust k-8 curricula#such that students get algebra 1 in eighth grade#also sfusd apparently forced a bunch of kids who had already taken a uc-approved algebra 1 course in eighth grade#to retake it in ninth grade#hello?????#this was in like 2014 but still#*taken and passed i should clarify#oh! also there's these alleged data science courses proposed#as an alternative hs math path#that. bypass algebra 2? which is VERY NECESSARY for uh college level data science#so. yeah!

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

dean + ged thoughts under the cut, featuring some of my favorite things: dismantling the american education system, bullying sera gamble, john's journal, and sad dean hours.

the ged. oh my god the ged. look. the students i knew who went for geds instead of traditional diplomas either wanted to get out of high school early because they were miserable, or were coming back after dropping out. and regardless, it was tough. it's time-consuming, it's expensive, and it requires specific knowledge that i'm going to assume was hard to track down in the late 90s/early 00s.

imagine you're dean, you've been to multiple schools a year, you have no consistent foundation for any academic knowledge, and your dad thinks it's all pointless because he just needs you to follow orders. you missed the unit on polynomials in algebra because you were out of school for three weeks helping your dad track some ghouls. one state teaches us history in eighth grade and one teaches it in ninth, and moving between states means you missed parts of each. you've got to find the money to pay for these, find the curriculum to study, and be a resident in the state long enough to take all four tests - not to mention take and pass all four tests. and he did it. he fucking did it!

he's smart! he's so fucking smart! and i say this with two caveats: 1) that intelligence is a white supremacist concept and 2) that the american education system is primarily based on compliance and memorization, not actual skills. but figuring out how to navigate the system, figuring out what he needed to learn, learning it, and passing those tests with all the obstacles he faced. that takes so much.

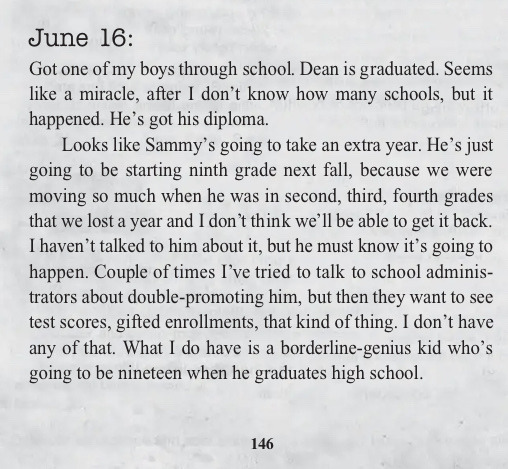

here's the thing. the ged line comes from gamble and that makes me think it was intended to be a joke about dean being dumb. but i'd argue that getting a ged in his circumstances was much more difficult than getting a traditional diploma. especially with this kicker: john's journal says dean graduated with a traditional diploma, on time. and you might say, arden, you gotta stop talking about john's journal. to which i say: no <3

john's journal, according to the author, is, "if not official canon, then certainly authorized." he wrote it in conversation with kripke and cathryn humphris during season 4. the ged line is from 05x02 (so dean having a diploma predates dean having a ged). and john's journal says unequivocally that dean got a diploma on june 16, 1998 (page 146).

so what does this mean? you might say the journal is just a stupid semi-canon moneygrab and doesn't count. okay. you might say john doesn't know the difference between a diploma and a ged. fair. i say that we have two options: one, dean had gotten his ged much earlier in secret as a contingency plan and faked getting a traditional diploma for john, or two, dean dropped out without telling anyone, faked getting a traditional diploma, and did his ged later (i'd guess stanford era when john let dean go out on his own).

why? i'm guessing john emphasized repeatedly how important it was for his kids to get "normal" diplomas like "normal" kids. and dean didn't want to let him down. hell, john describes dean graduating as "getting one of my boys through school." no credit to dean, of course. i think there could be an issue too of dean knowing he's not supposed to be the "smart one." john calls sam a borderline genius in his entry about dean's graduation and spends way more time talking about sam than dean. maybe it was in dean's advantage to play dumb? maybe sam's?

finally, timing. if he got his ged early, i'd guess it was because he wanted to drop out and help john hunt. he probably went through the whole process, got it, and never told john because john wouldn't have let him drop out. if he got his ged later, i think it was for cassie. maybe he thought if he got the ged he could go be a college kid just like her.

bottom line? i'm so proud of him. i'm so fucking proud of him.

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do both Fives get put in school in your double trouble AU? Do they get to have a chance at a (semi) normal childhood? How do the siblings handle having to actually parent one young kid and an actually an old man kid? And does young!Five bring out the childish side of old!Five? I just love this entire concept and young!Five having to fit in with the absolute disaster that his family has turned into. He loves them anyway.

“You know, we could go to school.”

Five flips a page in his book and ignored his ‘twin’ aggressively. But he could feel the heat of the stare from across the room and it was interfering with his concentration. So he glances up to meet gazes with a face identical to his own. “We aren’t going to school.”

“Why not?” Baby Five asks. Five shoots him a look but baby Five ignores him with ease, face earnest in a way they both know is false.

“I am fifty-eight years old.” Five informs his idiot double, as though anyone could ever forget what with Five bringing up his age every other minute. “I’m not going back to school.”

“Did you really keep track in the apocalypse?” Baby Five asks, raising his eyebrows at the other. His face is full of implied doubt, and Five would be offended if it wasn’t founded. When Five doesn’t respond, Baby Five crows triumphantly, “Ha! I knew you didn’t really know how old you are.”

“The Commission estimated!” Five protested, “I’m sure they were accurate!”

“Oh? Just like how accurate they were about the apocalypse definitely happening?”

There’s really no good response to that so Five just shoves his book off his lap and crosses his arms childishly. Not that he’s a child. They already established this.

Mercifully, Baby Five drops that line of inquiry to focus on the other equally terrible one. Perhaps not merciful after all. “What’s so bad about going to school, anyway?”

There’s a pause between them, before Five bristles, “It’s - it’s full of children that’s what!”

“You don’t even know what school is like!” Baby Five protests loudly, “You never even went! It could be fun!”

“If media has taught me anything it’s that school is in no way fun.” Five points out, standing his ground on the topic. Admittedly his knowledge of schools is limited - he only tried to scavenge around a couple during the apocalypse. Too many children’s corpses for his comfort, but a decent source of pens and paper and similar supplies.

“Claire said it’s fun.” Baby Five holds his position.

“Claire is six and the only things she’s really learning are how to read and write and make glitter monstrosities to hang upon the refrigerator.”

“How do you know it wouldn’t be us making cool things to hang on the fridge?” Baby Five challenged, suddenly frowning. “Plus I mean - I dunno. I love Mom but I feel like she should be able to do her own thing, you know? Instead of teaching us?”

Five would like to protest that he doesn’t need the lessons since he’s an adult, but Grace has been a life saver when it comes to bringing both of her boys up to date on the present day and also gently giving them books and worksheets about things they never got to in lessons since they left at thirteen.

“You want to be stuck learning about basic algebra and geometry?” Five asks instead, because it’s easier focusing on how school inconveniences them instead of how they are inconveniencing others. But his voice is just a tiny bit more uncertain that it was before.

Baby Five sighs deeply, “I mean. I guess not. But I’m bored of staying in the house all day and seeing the same people and just. Ugh. It’s been the same thing my whole life! Can’t we just like, pick and choose what classes to take? Maybe we could do maths with the higher up students.”

“I’m pretty sure we’re at like, the excessively knowledgeable ‘probably has a doctorate in mathematics’ level of maths.” Five says doubtfully, because it’s true. Five has been teaching his counterpart the equations and tricks he’s learned after forty-five years of doing nothing but think about equations and time travel in his spare time, but it’s not like it doesn’t come naturally to them. Five had always been light years ahead of his siblings when it came to the subject, and it was often a point of frustration when the others didn’t get something.

To Five, complex equations and algorithms were as second nature as walking. Sure they’d had to learn the basic at some point, but once they got the hang of it, it was easy. Time travel equations were more akin to figuring out how to walk on water instead of just walking. In this needlessly complex metaphor, that is.

Baby Five slams his hands on the desk, making Five jump (though he’d deny it if pointed out), “That’s it! We could go to college! They let you pick classes and stuff there, right? So we could just test into the highest math class possible? Or not take one at all!”

“We’re thirteen.” Five counters, but his tone is a little more thoughtful. “We’d have to take tests and stuff to say we’re ready to graduate high school. Which we are. Actually I’m pretty sure Reginald had us at college level when we were nine.”

“He always did have high expectations. But seriously! Just think about it! We’d get out of the house. We’d learn cool things. Luther ‘n Allison would stop fretting about what we’re gonna do with our lives. A whole new population to play tricks on.” Baby Five grins with mischief, and it makes Five crack a small smile back.

But there’s one problem.

“Ugh, we’re going to have to legalize our existence if we want to do official things like that. And then they’re not just going to let us do our own thing, what if they try and take us away?” Five has never had a desire to go into the foster system, thank you very much.

“No one ever said we had to do things the legal way.” Baby Five sniffs, as though offended at the very thought of going through proper channels. Which, well. Yeah that sounded like the Hargreeves way. “I bet we could like, just pretend we’re the original Five’s kids or something. We would’ve been what, sixteen? There have been younger parents.”

“Pretend to be our own children? That’s your solution?” Five asks, eyebrows climbing up his face in incredulity. “And then what? Make it so we died and? Left our little orphan selves to family?”

“It’s plausible!” Baby Five protests.

“Yeah, and it would still wind up with us having one of our darling siblings as a legal guardian.” Five said firmly, which was his whole issue with this to begin with. “Which one of the boneheads downstairs do you want to have legal control of our lives?”

“Mom could do it?”

“If you think Mom legally exists in the eyes of the law you’re even more naive than I thought.” Five sniffs, “She’s even worse off than we are.”

“Well okay miss negative Nancy,” Baby Five huffs, “You figure something out then.”

“Negative Nancy? Have you been hanging out around Klaus too often?” Five looks offended at the very possibility of their brother being an influence on his alternate self. Baby Five sticks out his tongue instead of answering.

There’s a pregnant pause between them before Five sighs, “Ugh. I’ll ask Mom about it tomorrow if it means so much to you. But I still absolutely refuse to attend a public high school with a bunch of snot nosed children.”

“We’re snot nosed children if you haven’t noticed.” Baby Five gestures between them with a roll of his eyes. This time it’s Five who sticks his tongue out childishly in response, even though as an adult he should really be above such things.

“Maybe we can take a history course and you can correct the professor.” Baby Five offers, a vague sort of olive branch.

“Bet you we could make at least one physics professor faint by jumping into class.” Five shoots right back, taking said olive branch with as much grace as he can allow.

“Dibs on the time travel stuff for a thesis.” Baby Five grins.

“Absolutely not.” Five shoots down instantly, “When you spend forty years working on inter-dimensional maths, then and only then can you claim my work you little thief.”

And that ends the discussion on that.

-

BUT YEAH essentially I don’t think any iteration of Five would ever really go to high school with other kids like that because honestly?? even as an actual thirteen year old Five is lightyears ahead on some subjects and he has issues. Can you imagine Five dealing with bullies and gossip and shit teachers??

Five would have one (1) person pick on him and break someone’s arm because he was taught violence is the first answer to everything. He’s genuinely kind of too dangerous to be around other kids his age. He’s also not one to suffer fools lightly, and so the first time a teacher taught something wrong (which they would because history class is full of historical revision and Five was probably there for half of it) he would butt heads with someone. I knew teachers who didn’t like to be corrected and I knew teachers who would be thrilled their student actually knows a subject, it just depends.

I mean Five is thirteen and that’s what? Eighth grade? That isn’t even high school yet. I was learning geometry. I was reading the outsiders. Learning all the prepositions in english class. Making bridges out of popsicle sticks in physical science and watching that one miracle of life video again. We had to run the mile every Wednesday and it was the worst.

You think putting Five in a PE class anywhere near other children and dodgeballs is in any universe a good idea?? He would obliterate them. He would make at least one person cry and probably send another to the nurses office and then, when he got in trouble, wouldn’t understand what he did wrong. Because Diego threw knives at him and probably hit him at least once, a foam ball should be nothing and that kid is making a fuss for no reason. Doing sprints until he pukes - you mean an average Thursday in the Reginald Regime?

at least in college Five would be able to tailor his schedule and take whatever level course he needs. He could be in very high level math courses and be in beginner’s astronomy or intro to archaeology or linguistics 101 or whatever the hell he wants to learn tbh (probably anthropology or contemporary history courses if he wants to catch up to modern day??)

as for the parenting bit, both Five’s aren’t exactly what you would call receptive to being parented by anyone thank you very much and will aggressively tell you to fuck off if you tried

BUT both Five’s also wouldn’t know what the fuck a parent looked like if it hit them in the face with a baseball bat because when they think ‘parent’ they think ‘good old Reggie here to traumatize everyone again’ so their idea of being parented is?? being told to train, being told what to do/being given a schedule to follow with specific hours carved out for everything, private training, being told their flaws in excruciating detail, etc. so like,, if the bigger Hargreeves are careful and subtle about it and frame it in a sibling way then they can sometimes get away with it

after all if Diego drives Klaus everywhere, then it’s not bad if Diego offers to drive the Fives somewhere, even if they can do it themselves. If Allison fusses and puts more food on everyone’s plates then it’s not a thing and doesn’t need to be pointed out. If everyone has to check in with hourly texts to the group chat when they’re out after dark, then it just makes sense that the Fives do as well since knowing where everyone is can only be a boon after all the shit they went through in the apocalypse

honestly the parenting going on is basically just setting up healthy boundaries (making sure the Fives knock before just fuckin jumping into someone’s room or bathroom) and gently coaxing them into going out and doing things which they can frame as family outings/taking Grace out to see the world, and also gently nudging both Fives in the direction of healthier coping mechanisms/getting them to go to therapy, that sort of thing

Vanya is a firm believer in both therapy and setting an example so she probably gently encourages the whole family to find someone to talk to and holding up setting an example to the Fives as an excuse to get her whole family into much needed therapy is very helpful

and young Five ABSOLUTELY brings out the childish side in old Five, mainly because old five actually genuinely has No Fucking Idea how adults function and while he physically grew up, his social growth was very stunted by the,, how do i put this,,, lack of Anyone Existing Around Him For Forty Years so he has like?? vague ideas of how grown up people function but not a whole lot

like his primary example of Being An Adult are a) Reginald, an eccentric billionaire who didn’t work outside of abusing children like that was his job and b) the Handler who has no concept of personal space and frequently insinuates she’s going to kill him

and THEN,, when he actually achieves his goal and gets back to his family he gets a wonderful assortment of:

Luther, who lived on the moon for four years with no social interaction. Has never owned property or held down a job. Has he ever done taxes? Has he voted in an election? Does he even have a license?

Diego, who lives in a boiler room at the back of a gym and fights crime as a vigilante in his spare time after flunking out of the police academy. Has anger issues and an obsession with knives.

Allison, the movie star whose personal life is a fucking WRECK and is going through a brutal child custody case after she mind controlled her child on multiple occasions.

Klaus, who in general is just a wreck of a human being who has no occupation that I know of and is frequently in and out of rehab. Also homeless and overdoses on a seemingly regular basis if the nonchalant-ness with the paramedic says anything on that.

Ben, who is dead and invisible to them but who likely died before reaching adulthood anyway so.

Vanya, who has managed to hold down a job and home but has no social life to speak of and taste in men bad enough to literally end the world if given the chance. Seething with anger and resentment that has been bottled down and doesn’t know how to deal with her own emotions (though that was mostly Reggie’s fault tbh)

but as you can see there is not one single human adult in the Fives lives that is even in the ballpark of healthy normal adult role model.

I got away from myself but my point is that Five doesn’t know how adults act and baby Five is capable of prodding Five into joining his shenanigans partially because of this fact and partially because Five just genuinely wants to have fun sometimes

and if, occasionally, the duo pretend to be one another so that Five has an excuse for acting as childish as his genuinely teen counterpart then, well,,, who can tell them apart anyway? and it’s in the name of the game and confusing their siblings so there

I have plenty of feelings about the double trouble au goodness gracious

#double trouble au#far tua long#the umbrella academy#tua#this is the au where thirteen year old five shows up a few days after they stop the apocalypse and everyone has to deal with that#five hargreeves#number five#i'll add more tags tomorrow i'm tired and it's midnight

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Faja Essays.

May 22, 2020

We have all met people along the way who have influenced our lives. If I were to do a “top ten” of those who influenced mine, Garry Faja, my high school buddy who died last summer, would be high on the list. The son of working class parents whose father emigrated from Poland and repaired machinery at the Rouge plant, Garry went on to become the President and CEO of St. Joseph Mercy Health System. Recently, I and four or five of Garry’s friends and former healthcare profession colleagues were asked to write essays for a book about him being compiled by a friend from his grad school days at U-M. It is intended to be a keepsake for Garry’s only child. I was honored to be asked to contribute stories about Garry’s early life. Because several people who follow this space knew him well, I’ve posted the portion I wrote below:

First Impressions.

I had heard of Garry when he was an eighth-grader during the 1960-61 school year at St. Barbara’s grade school, near Schaefer and Michigan in East Dearborn. I was also in the eighth grade, attending St. Alphonsus school, just a mile or two to the north. Garry and I both had neighborhood reputations as athletes at our respective schools.

St. Al’s, however, had a much more successful CYO sports program than St. Barbara’s. We won our divisional football championship in the fall, going undefeated; we won our divisional basketball championship in the winter, going undefeated again; and we were 6 and 0 in the league in baseball that spring when we played Garry’s St. Barbara team on a sunny May afternoon at Gear Field.

That’s when--BAM--it happened: “Down go the Arrows…down go the Arrows…to Dearborn St. Barbara’s.” An old news clip from The Michigan Catholic, a popular weekly newspaper in those days, included the following snippet about CYO baseball that spring: “Dearborn St. Barbara’s came through with the upset of the week by knocking off St. Alphonsus, 11-8. St. Alphonsus still holds first place in the Southwest Division with a 6-1 mark.”

Neither Garry nor I could ever recall how either one of us performed on the field that day. We did recall, however, that we both looked forward to joining forces and playing sports together in high school. St. Barbara did not have a high school; St. Alphonsus did. Garry had long planned to enroll for his freshman year (1961-62) at St. Al’s, where his brother had been a track star, one of the top high school hurdlers in the state.

When we began high school in the fall of ‘61, I recall standing in the middle of the playground with my close friend Anthony Adams, along with Sam Bitonti and Patrick Rogers. I remember looking over to Calhoun, the side-street on which the high school was located, and noticed a small procession of cars dropping off new students from St. Barbara’s: twins Jim and Mike Keller, Sue Hudzik, Margo Tellish (Garry’s grade school girlfriend) and the “big fella” himself.

At the urging of Garry’s mother, Jim, Mike and Garry wore white shirts to school that day. “The boys” and I, on the other hand, wore multi-colored shirts (mine was purple), skinny ties, tight pants and pointed shoes. Looking like “the Sharks” from West Side Story, we approached the new kids, welcomed them to St. Al’s and shook their hands.

I’ve long thought that the way we were each dressed that day—Garry in his white button-down, me in my bold attire—portended the essence of what we would ultimately take away from each other at the completion of high school: for me, a determination to go about things the right way; for him, a touch of edginess.

The Person. The Scholar. The Athlete.

I never knew anyone who didn’t like Garry Faja. Unless, that is, you count a hulking bruiser by the name of “Bucyk” from Ashtabula, who elbowed our buddy Tony Adams in the chest and tried to intimidate us on the street at Geneva-on-the-Lake, Ohio. (Thank God we talked our way out of that one.) Otherwise, all the guys, girls, parents, nuns and coaches of the St. Al’s community loved Garry. He commanded respect on every level—for his heart, his intelligence, his athletic prowess.

Garry was a born leader. Despite being the “new guy,” he made such a good early impression in high school that he was elected president of the freshman class. He was a member of the student council all four years. And he was elected president of our senior class.

Garry was an excellent student, a member of the National Honor Society. He was neither class valedictorian--that was Lorraine Denby--nor the salutatorian--that was my girlfriend, Leslie Klein—but he had an extraordinary ability to “figure things out,” enabling him to excel at algebra, trigonometry, chemistry, the sciences. Moreover, he was highly disciplined. He had what our parents called “stick-to-it-tive-ness,” and it served him well at everything he did.

Garry was an organizer, a strategic thinker, who rallied for increased student attendance and crowd participation at high school games, involvement in a big-brother/big-sister-type mentoring program by seniors for freshmen, as well as causes he believed in. For example, it was Garry, with support from senior class leaders such as Larry Fitch, Vince Capizzo, Tony Adams and myself who compiled a list of “Ten Demands” that were presented to the school principal, Sister Marie Ruth, on behalf of the Class of ’65. It was, essentially, a protest against what we perceived to be unreasonable rules and disciplinary actions created by the priests and nuns of St. Alphonsus: single-file lines and “no talking” during change of class; locked school doors on sub-zero mornings during winter; mandatory daily Mass attendance, etc.

It was a daring, out-of-the box challenge to religious authority for a bunch of Catholic high school kids in those days. Predictably, our demands went nowhere and we were disciplined by having to stay inside the school for two weeks during recess, and, ironically, forbidden to attend daily Mass for two weeks. (The nuns showed us, I guess.)

Sometimes I wonder whether our youthful backlash, with Garry at the forefront, was an early tip-off to the kind of student thinking that morphed into the free-speech movement and anti-war protests that developed on college campuses across the country a year or two later.

As highly as Garry is remembered as a person and leader by St. Al’s Class of ’65, he is recalled by “old Arrows” for his basketball playing ability. He was a starter on the JV squad from day one of his freshman year. However, it took just a few weeks for the coaches to realize that he was talented enough to help the varsity. In Coach Dave Kline’s last year at St. Alphonsus, Garry was moved up to the varsity where he became “sixth man,” before being designated a starter at mid-season. That was big stuff, really big stuff, for a freshman at our school.

So what kind of player was Garry?

A mini-version of former U-M standout Terry Mills, in my estimation. He was a shade under 6’2” tall…thick-skinned…had a nice 15-foot jump shot…and an ability to use his derriere to “get position” under the basket. Any former St. Al’s player would tell you that Garry had game and a distinctive way of gliding up and down the court. For some reason, he also suffered severely sprained ankles more often than any other young athlete I have ever known.

Garry and I were starters together for three years under Coach Ron Mrozinski and were elected co-captains as seniors. Garry once said, “Lenny, we gotta be the team’s one-two punch.” I had speed and quickness, often stealing the ball at mid-court, and would dump it off to Garry who could be counted on to fill the lane. If he came up with the ball after the other team turned it over, I was to beat my man and streak toward the basket, expecting to receive the ball from Garry. We pulled that stuff off dozens of times each year. But we never realized our dream of winning the Catholic League’s A-West Division title and competing in the Catholic League tournament at the U-D Memorial Building (now called Calihan Hall).

However, Garry was named to the Dearborn Independent’s all-city basketball team after his senior season in 1965, a particularly special honor when you consider that St. Al’s had an enrollment of just 450 students, while most other first-teamers and “honorable mentions” on the all-city squad came from Class A schools with enrollments approaching 2,000 (Fordson, Dearborn High and Edsel Ford).

Happy Days at Camp Dearborn.

It was prime time for Dearborn during the early-to-mid ‘60s. The city had idyllic neighborhoods, spilling over with kids from the baby boom generation. The Ford Rouge plant was pumping out record numbers of vehicles, including an all-new “pony car” called the Mustang. And it owned Camp Dearborn (in Milford, 30-35 miles away), over 600 acres of rolling land with several man-made lakes, devoted to the recreational interests of Dearborn residents.

One of Camp Dearborn’s attractions was a narrow tract of land along the Huron River, designated for tent camping by teenagers. Dubbed “Hobo Village,” it was “chaperoned”—if you want to call it that--by a couple of disinterested college kids who worked day jobs, cleaning up the camp, and who lived in their own tent on the river. As 15-year-olds in the summer of ’62, Garry and I got our first taste of independence when we camped there together for a week.

We set up a large tent, with two cots inside, that my Dad had purchased at a garage sale. We hung a Washington Senators pennant to decorate its interior. And we subsisted on Spam and eggs that we cooked in a Sunbeam electric fry pan (we had access to electricity) that my Mom let us borrow.

Every evening we’d cross the camp on foot en route to the Canteen for the nightly dances. We’d get “pumped” every time we heard “Do You Love Me” by the Contours playing in the distance. Our goal, of course, was to meet “chicks,” and we attended the dances for seven straight nights. However, I don’t recall that we ever met a girl. Or even mustered the courage to ask one to dance.

But that all changed in the summer of ’63.

Camp Dearborn had another, larger camping area for families called “Tent Village,” featuring hundreds of tents built of canvas and wood, set on slabs of concrete, each equipped with a shed-like structure that housed a mini refrigerator, mini stove and shelves for storing staples. The mother of our classmate, Patty O’Reilly, agreed to chaperone a tent full of St. Al’s girls, next to the O’Reilly family tent, while Tony’s mother, Mrs. Adams, agreed to chaperone a tent full of boys, next to the Adams family tent.

Tony, Vince Capizzo, Larry Fitch, Dennis Belmont, Garry and I occupied one tent. Our girlfriends occupied the other. Much to my amazement, my parents allowed me to take their new, 1963 Pontiac Bonneville coupe to camp for the week. So we had everything we needed—hot chicks, a hot car, rock ‘n’ roll, the dances and secret “make out” spots in the camp (Garry’s girlfriend at the time was a cute blonde St. Al’s cheerleader, Donna Hutson). It all made for perhaps the happiest days of our teenage lives.

And we did it all over again in the summer of ’64.

During both years we were involved in shenanigans galore: We threw grape “Fizzies” into the camp’s swimming pool…we switched out a hamburger from Vince’s hamburger bun and replaced it with a Gainsburger (dog food)…and one afternoon we took my Dad’s Bonneville out to a lonely, two-lane country road, just outside of General Motors’ proving grounds in Milford, where we floored the accelerator and topped out somewhere north of 100 mph. It scared the shit out of us when we hit a bird in mid-flight that splattered all over the windshield. Thank God for laminated safety glass. Thank God we lived to tell the tale.

Which brings me to the “edgy” side of the teenage Garry Faja.

Stupid Stuff We Did.

When Garry came to St. Al’s, my circle of friends became his circle of friends. And an eclectic group it was. Some were college bound kids. Some were mischievous pranksters. A few were borderline juvenile delinquents. None of us, including Garry, were immune to peer pressure. Consequently, we did some pretty stupid things. Here are a few examples:

The Toledo Caper--On a snowy Friday night after a basketball game during our sophomore year in high school, Garry, Jim “Bo” Bozynski and I trudged down Warren Avenue in our letter jackets, headed for Bo’s house, with the intention of ordering a pizza.

It was, perhaps, ten o’clock at night as we crossed the field in front of Bo’s home on Manor in five-inch-deep snow. As we looked ahead, Bo surmised that because the house looked dark, his parents were already in bed and likely asleep. That’s when he hatched a plan:

Bo proposed to enter the back door of his house, go to the kitchen and retrieve the keys to the Bozynski’s ’58 Mercury sedan. Then, he, Garry and I would quietly open the garage door, push the Merc down the snow-covered driveway and out to the street, where we would start the car…and head for Toledo.

Neither Garry nor I objected to the idea. Ultimately, the plan worked to perfection.

However, we were just 15 years old and had not yet obtained our driver’s licenses. Plus, Bo grabbed a bottle of Bali Hai wine that he had stashed in the garage. And, the snow kept falling…then turned to rain. We drove through slop and glop on Telegraph Road, made it to I-75 and took turns at the wheel between gulps of cheap wine as the windshield wipers labored to clear the mounting sleet piling up on the windshield.

I was sitting in the back seat, the bottle of Bali at my side, when the car slid out of control in the middle of the southbound freeway, somewhere in the downriver area. I don’t recall whether it was Bo or Garry who was driving at the time. But I do recall that the car made a 360, sliding across two lanes of freeway, before coming to an abrupt stop in a snow bank on the side of the road.

We got out of the car. No one had hit us. Miraculously, we had not hit anyone or anything. There was no damage to the Bozynski’s family car. That’s when three stupid teenagers got back into the vehicle, reversed course, headed for Dearborn, killed the engine as we turned into the Bozynski’s driveway, silently pushed the Merc back into the garage, and turned in for the night at Bo’s.

No one was ever the wiser.

The Speeding Ticket—Both Garry’s parents and mine were strict disciplinarians when it came to girls and dating, but they rarely said no whenever we asked to borrow the car. We had already turned 16 when on a beautiful June day we took a bus downtown, filled out some paperwork (or maybe took a test) and obtained our drivers’ licenses. My Dad used his old ’58 Chrysler to get to work that day and let me have the Bonneville for our use when I got home. So, Garry, Larry and I jumped in the car and headed to Rouge Park for some joy riding. As usual, we disconnected the speedometer and took the “breather” off the carb so that the exhaust would make a throatier sound when we put the pedal to the medal. When we got to the park, I turned the wheel over to Garry. It was not as though he ordinarily had a heavy foot, but he did that day. I doubt that Garry was at the wheel for more than a few minutes when he spotted the red flasher of a Detroit cop car in the rear-view mirror. We pulled over. The policeman was all business…and gave Garry a ticket for speeding. Garry’s parents were furious that afternoon when he got home and explained what had happened. Garry went to court and lost his license for 30 days.

The Stolen Cadillac--It was a beautiful summer evening and we were playing our usual game of pick-up basketball in the alley between Tony’s house and Schaefer Lanes. As I recall, four of us were just shooting around—Garry, Tony, Butch Forystek and me. Someone looked up and noticed that a 1963 Cadillac Coupe de Ville had turned off the side-street, Morross, and was slowly making its way up the alley. It stopped in front of us. Our pals, Joe McCracken and Gary “the Bear” Pearson, jumped out of the car. Turns out that the Caddy had been parked in front of a store, with the keys in the ignition. Joe and Bear got in, fired up the Caddy, and drove it to Tony’s. Then we all got in, took turns driving the car, and went to M&H gas station to buy Coke and chips. For reasons unknown, Joe and Bear unlocked the trunk of the car. Underneath the rear deck lid were piles of pressed clothes on hangers in plastic bags, apparently for delivery by someone who owned a dry-cleaning establishment. Also, there was a narrow envelope atop the pile of clothes. Someone opened it. Much to our amazement it contained over $200 in cash. We all got back into the car and headed for a cruise down Woodward Avenue. We stopped along the way at a sporting goods store to buy a new basketball. On northbound Woodward, as it passes over Eight Mile Road in Detroit, Butch grabbed a handful of cash and threw it out the window. (It seemed hilarious at the time.) Garry and I each took a five-dollar bill, reasoning that keeping such a paltry sum would not be considered a “mortal sin.” After taking turns doing “neutral slams” at red lights, we turned the car around, headed back to Tony’s, and continued playing basketball while Joe and the Bear ditched the car.

Again, no one was ever the wiser.

The Shotgun Incident—It was a crisp fall afternoon. Garry and I were hanging out with Tony in his parents’ basement, while Mr. and Mrs. Adams were away, attending some sort of event. Tony knew where Mr. Adams, a bird hunter, stored his shotgun, and proceeded to take it out to show us. There were also a few boxes of shells next to the gun. Tony informed us that his Dad owned a large piece of vacant property in an area that was known as Canton Township at the time. Knowing that his folks would not be home for several hours, we took the shotgun, a box of shells and placed it in the trunk of Mrs. Adams’ Ford Falcon. Off we went to the property in Canton. To hunt sparrows. Tony had seen his father load the gun. Otherwise, none of us had ever had any training in the proper handling of firearms. We knew enough to stand behind the guy with the shotgun in his hands. We took turns shooting into the trees. And bagged a couple of small birds. We eventually returned to Tony’s and put the shotgun away.

Yet again, no one was ever the wiser.

How The 53-Game Streak Started.

Most people know that Garry and I attended 53 straight Michigan-Michigan State football games together—whether in Ann Arbor or East Lansing—from 1965 to 2017. In fact, when the streak ended, we had been in-stadium for 48 percent of the Michigan-Michigan State games ever played.

Prior to the 2018 game, however, Garry determined that he would not be able to negotiate the steep ramps to the second deck of Spartan Stadium due to his failing knees. So, for the first time in our lives—since the days of black and white TV--we watched the game together on the tube. Here is the seemingly unremarkable way a renowned tradition began…plus a closing thought:

As I remember it, Tony Adams, Garry and I were sitting in my bedroom on a hot, steamy, mid-August afternoon, making future plans as we counted down the days to the beginning of our respective college careers. Tony would be going off to Western Michigan University as a business major. Garry would be attending U-M, majoring in engineering. While I planned to attend MSU to study journalism.

We had been athletes. Competitors to the core. Garry and I knew that our respective schools would rarely, if ever, be playing Western, but we certainly understood that he and I would be butting heads in the future, pulling for opposing teams in the Big Ten Conference every year. So, in a spirit of friendship, we mutually decided to get together every fall to attend the Michigan-Michigan State football game until one of us died.

It was as simple as that.

But when I think back to that muggy August afternoon when we made our pact, it seems a metaphor for all the goals, hopes and dreams we so often talked about between the games, joy rides, dances, pranks, parties and school projects we collaborated on at St. Al’s from 1961 to 1965. I often think, for example, about how Garry and I worked alternate days at my uncle’s store, from the spring of our junior year until the fall of our senior year, and shared tips and insights into how we each did our jobs—long before anyone ever used the term “best practices”--so that we could be the best damn stock boys my uncle ever had. As I hinted earlier, I will always be grateful to Garry for making a lasting contribution to my determination to do things the right way in life. And I’d like to think that Garry thought well of my tendency to “push the envelope” on the things I attempted, and that maybe I made a contribution to the release of his creative potential.

Miss you, Big Guy.

1 note

·

View note

Note

How does middle/high school work, what's it like and what's the difference between the two? I really need some help! (I know this is a weird question but I was homeschooled most of my life so I have no idea how middle/high school work and what's it like.)

No problem!

How to Write About Middle School/High Schools

Middle school and high school are key times within a child’s life.

Gone are the days where they only had one teacher to tell them everything; now they have to change classes and have harder content that they have to study.

There’s more friend drama now that they’re all developing their own identities and their sense of who’s a good person and who’s not, and along with that comes astronomical stress compared to their elementary school years.

There’s also puberty, which sucks, and the beginnings of serious extracurricular activities that require a lot of time and dedication.

*This may vary from school to school*

Middle school = Grades 6-8 (Kids 11 to 13)

High school = Grades 9-12 (Kids 14 to 18)

Since many people have no idea how to write about schools, whether they be homeschooled or have graduated a while ago, here’s a few tips on how to write middle school and high school.

Just a note that I’m going to be describing public schools and not private schools, Also, schools are going to be different across the country; I’m a New Yorker, and my school knowledge and experience can be way different than those of someone who went to school in the south or in the midwest.

**IMPORTANT NOTICE!**

“High school” and “middle school” are not capitalized! Only capitalize it when you’re saying the name of the school. (Example: Eldridge Middle School)

1. Know What Grades Take Which Courses (AKA Know All the Technical Stuff)

Nothing demonstrates complete lack of knowledge about the school system than not knowing the basic technical side of it, such as which grades take which classes. Aside from various exceptions, an eighth grader isn’t going to be taking Physics and a twelfth grader isn’t going to be taking Biology.

Here’s the list of the core classes in middle school and high school:

English

Math

Science

Social Studies

Foreign Language

These classes are going to be the hardest and the ones that the students stress out the most about.

Grade 6

- English

Read things like The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe and Tuck Everlasting

- Math

Multiplication and division

Decimals

- Science

Basic physics…like, very, very, very basic. Also a bit of chemistry.

-Social Studies

Ancient history

Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, Persia, China, India, Renaissance, etc.

- Foreign Language

In my school, we didn’t start a foreign language until seventh grade.

This year is very stressful because it’s the transition from elementary to middle school. They now have things like detention and multiple teachers and changing classes.

Grade 7

- English

Reading books like My Fair Lady, The Miracle Worker, The Pearl, etc.

- Math

Starting to work with “x.”

Percents, statistics, basic algebra.

- Science

Basic biology

- Social Studies

Beginnings of US history. From the Native Americans to the Industrial Revolution.

- Foreign Language

Very basic facts

How to say hi, describe yourself, furniture, food, activities, ask questions, etc.

This is a pretty chill year. You’re all adjusted from last year and have more stable friendships.

Grade 8

-English

Reading books like Call of the Wild, The Outsiders, the White Mountains.

Starting to get into Shakespeare

More in-depth analysis

-Math

Algebra

Equations, find x, etc.

-Science

Earth Science

Rocks, weather, space, etc.

-Social Studies

End of US history, from the Industrial Revolution to present day

-Foreign Language

Developing the basics learned in seventh grade.

This year can be hard because students start taking more difficult, high-school level classes.

Grade 9

- English

Reading books like To Kill a Mockingbird, Of Mice and Men, Great Expectations, and Romeo and Juliet

Introduction to research papers

- Math

Geometry

Learning about shapes and how to find the area and sides

Most useless math there is unless you want to build things

- Science

Biology

Learning about living things, cells, ecosystems, etc.

- Social Studies

Global History

Beginning of the world to the Renaissance

- Foreign Language

More complex sentence structure. Learn different tenses other than the present tense.

Yikes! This year is incredibly hard; high school is so much more difficult than middle school! There’s an open campus and a lot more freedom, but there’s also a lot more room for error. The first year where the grades start actually counting.

Grade 10

- English

Reading books like Macbeth, The Picture of Dorian Gray, The Canterbury Tales, Beowulf, and Animal Farm.

- Math

Trigonometry/Algebra II

Very difficult Algebra and Trigonometry

- Science

Chemistry

Learning about molecules, elements, formulas, and reactions.

This is the science with the periodic table and mixing stuff that blows up.

- Social Studies

Global History

The Renaissance to present day

- Foreign Language

Learning new tenses other than Past, Present, and Future (Ex: Imperfect, Conditional)

This year is okay. Mostly spent worrying about Junior year.

Grade 11

- English

Reading books like Hamlet, The Great Gatsby, and Farenheit 451

- Math

Pre-Calculus

Yikes

- Science

Physics

Also Yikes

Learn the science of movement

- Social Studies

Complete US History

Advanced Placement US History is abbreviated to APUSH (pronounced ay-push)

- Foreign Language

Same class but hard now

This year is very stressful because it’s the year that counts the most; colleges look mostly at the grades from this year.

Everyone is freaking out and taking AP and SAT and ACT prep classes. A shit-show in its purest form.

Grade 12

- English

Read books like Othello, The Crucible, and The Scarlett Letter

Senior paper

- Math

Calculus

YIIIIIIIIKKKKKEEEEESS

College course

- Science

AP Biology, Chemistry, or Earth Science

Students must choose one or the other or an elective science like Marine Biology or Anatomy

- Social Studies

Government and Economics

Two courses that are each only a semester long. You either take one class for the first semester and switch to the other class second semester or switch the classes every other day

- Foreign Language

Nobody even cares anymore

This year is the most fun year of high school; although some colleges do still look at the grades, many students are already committed to college and get a case of “Senioritis” which is when they let their grades slip and take it easy because they don’t have to worry about impressing colleges.

OKAY THAT TOOK A LOT MORE TIME THAN IT SHOULD’VE

2. Know the Types of Classes

Depending on their skill level in the area, kids can take a variety of different versions of these core classes. There’s reagents classes, honors classes, and advanced placement (AP) classes.

At least in New York, reagents classes take state-made reagents at the end of the year as a final exam.

Honors classes are basically advanced versions of reagents classes. They teach at a faster pace and go more in-depth into the topics. They, too, take reagents at the end of the year.

AP classes are the hardest of them all. They’re college-level classes and make students eligible to take the AP test. Depending on what score they get on the AP (1-5), they can skip the 101 classes in college.

(Example: If a girl gets a 4 on the Global History AP, she can skip Global History 101 in college)

Junior year is also the year students take the SAT and ACT, huge tests that are very important for college.

Other schools may have other kinds of classes like IB, but this whole list is JUST ACCORDING TO MY EXPERIENCES.

3. Just Know that School Is Not the Worst Place on Earth

Although there are certain times when school can be the absolute worst thing ever and there are a lot of flaws in the education system, it’s not all downsides!

School is a place where you learn new things, meet new friends, and get to hang out with people you wouldn’t hang out with otherwise.

There are extracurricular activities available for FREE that you can join, and aside from being academic, school sponsors a very nice social climate that is crucial for kids to develop skills in communication and interaction with others.

Of course, high school is also the place where people start getting into serious relationships, which you can research here.

I really hope this helped!

#writing#writing help#writing advice#school#help for writers#writing about school#high school#middle school

498 notes

·

View notes

Text

My school didn’t have a “gifted” program. What it had was a “you’re going to take high school classes in middle school” and “we’ve outsourced this advanced class to an off-campus program.”

So everyday during my science class, I and one other student walked down to the high school to take geometry with freshmen and sophomores and juniors, and I started to do poorly in science given that I was missing over half of the class time each day. But it wasn’t all bad, because I got to talk to someone on the walk down to the high school, and I did relatively well in these classes.

Then, in the afternoon, I would be picked up by a family member or carpool with one (1) different student to go to an offsite education program over thirty minutes away during my lunch period. This wasn’t so bad, because I was only missing ELA classes, which were the advanced classes I was taking off site.

So it wasn’t so bad.

Except for one year. Seventh grade. When I was placed in Algebra with a group of eighth graders. I didn’t have a friend this time. I didn’t have a walk. And I didn’t have my glasses. And I was alone in a classroom of The Big Scary Kids and a teacher I didn’t understand and I ended up doing poorly in Algebra. Enough to make me hate math forever. Enough that I had to follow my teacher to his next class so he could help me revise my final exam enough for me to get a C on it. And I remember being the only one.

I am glad though, looking back as I am now, that we didn’t have a “gifted” program. That we knew we were a little advanced, but no one told us we were gifted or special. Because I can only imagine how much harder the self-disappointment would hit me had I been taking Algebra in a classroom and doing so poorly amongst a larger group of people. If I had not been separated by age or experience and it was a class of people who were told they were gifted, and there I am, proving I’m not.

The gifted program at school was like "You solved a puzzle really good and that means you're Gifted which means you're going to a different classroom to do more puzzles while these other plebs learn math" and would you like to guess who consistently failed math for the next decade

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

A bully is mean with Cyrus ( not necessarily because of his sexuality) and TJ is pissed.

Basketball Day - a Tyrus fanfiction

I apologize for the extremely long wait. I really liked this idea, and it was a very fun idea to play around with. I hope you enjoy it!

On the third Friday of every month, Jefferson Middle School’s gym coach allowed (forced was a better word in Cyrus’s opinion) his students to partake in a monthly game of basketball. This usually enabled the Good Hair Crew and Jonah to form a group of their own (mostly Buffy and Jonah played, although Jonah was admittedly not that great at the sport, while Andi and Cyrus would stand idly by, making sure it looked like they were participating whenever their coach threw a glance their way.) It was the perfect setup; everyone got the chance to spend time with their friends, and no one got hurt! However, on the third Friday of April, the group’s normal routine did not play out like they had expected it to.

“Cyrus, come on!” Andi groaned, dragging her best friend Cyrus towards gymnasium. Getting Cyrus to come to gym was probably the biggest chore of all of the responsibilities that came with being Cyrus’s friend. That boy did not like PE.

“I don’t wanna!” he whined. He stumbled over the threshold as she dragged him towards his inevitable doom. Oh, how he despised gym class.

By the time that gym had rolled around that Friday morning, Cyrus’s day was already off to a bad start. He had missed another opportunity to possess one of the much coveted chocolate chocolate-chip muffins, he hadn’t gotten the grade he had wanted on his most recent algebra test, and, even worse, Buffy was missing school.

It was a rare occurrence for his best friend, and Cyrus felt naked without her at his side. Of course he missed her, and it was tough to face the day without her random quips about Ultimate Frisbee, or her unrelenting support, but nevertheless, Cyrus wholeheartedly approved of her absence. She was finally getting the opportunity to spend the day with her mom, who had just returned from her lengthy deployment, and Cyrus knew how far and few between chances like this came for his best friend. His only worry was that him, Andi, and Jonah might have to find a fourth team member that they didn’t really know well, or one that didn’t know them that well, either. Those people usually made fun of him.

Once Andi finally got Cyrus past the entrance and into the gymnasium (Andi had to bribe him with tater tots from The Spoon, but the trade was well worth it in her opinion), she ordered him to stay put while she went to go look for Jonah. Cyrus watched her run off into another direction, and he felt his heart begin to pound. He hated being by himself.

In order to calm his nerves, he began glancing around at his classmates, looking at potential prospects for a fourth teammate. This is good, he told himself as his heart rate began to decrease steadily. Just keep…oh.

Cyrus’s eye caught on a certain basketball player, and his heart stopped altogether. T.J. Kippen.

Cyrus watched T.J. run a hand through his effortlessly tousled hair as he talked to a group of what Cyrus assumed were his friends, and he felt an unexplainable urge to touch the boy’s wavy, chestnut locks. Why did it look so soft?

Cyrus blushed when T.J. fleetingly glanced his way, and he ducked his head to conceal his flushed cheeks. That was a close one, he thought to himself. Be more careful!

Post-bar-mitzvah, Cyrus could admit that his feelings for T.J. had grown into something…different. Something that made his heart pound in his chest, his palms sweat, and his words to get stuck in his throat. And, maybe, something he couldn’t entirely label just yet.

Somehow, it felt a little different for what he felt for Jonah, or used to feel, that was. Whatever feelings he had harbored in his heart for the Frisbee player were now shifting to T.J., the most recent object of his affections. It was all so confusing, and even more so when he couldn’t talk to anyone about it (besides Andi and Buffy). Cyrus longed for the day where he could be open about his huge secret with everyone; especially his family. It was starting to become really hard to keep such a huge secret from his four shrink parents…

Before Cyrus could finish his thought, a bell-like laugh emitted from the basketball player, and the butterflies in his belly stirred uneasily at the sound. He loved it when he witnessed T.J. being happy and lighthearted.

Prior to having been introduced to him (he was still calling him Scary Basketball Guy at this point), Cyrus caught glimpses of the brooding basketball player in the halls or in their few shared classes. He had always wondered what T.J.’s problem was. Was being the captain of the basketball team too much pressure on him? Was he struggling with family problems? Or was he just a jerk that didn’t care who he hurt?

However, upon meeting him, Cyrus was surprised by how kind T.J. was to him, a complete contrast to how he treated Buffy. He never would have guessed that the same basketball player who was so spiteful to his best friend would even be capable of being caring and comforting, let alone to him.

In the end, Cyrus learned that T.J. had a learning disability, and he also felt inferior compared to other students (like Buffy) academically and physically, which caused him to lash out. It was almost hard to believe that someone that held himself up so high and mighty on the outside was actually hurting pretty badly on the inside.

Cyrus was broken from his thoughts when he noticed T.J. begin to slowly turn towards him, and suddenly everything felt like it was in slow motion. His heart rate began to climb rapidly; this was like the part in the cliche rom-com where the main protagonist met her love interest’s gaze from across the room, both of them thinking about how they were each other’s true love. Granted, Cyrus wasn’t a girl, and T.J. would never be into him like that, but still, a boy could dream.

When T.J. fully faced him, he caught Cyrus’s eye, and the corners of his mouth upturned in a slow smile. T.J. raised his hand and waved endearingly at him, and Cyrus internally swooned. He grinned widely back, beginning to return the sweet gesture, but T.J.’s friend pulled him back into their oh-so-important conversation before he got the chance.

At the sudden loss of interaction with T.J., Cyrus frowned. You can always talk to him later, he thought, trying to console himself. It’s not like it’s the end of the world. Except it was. It always was the end of the world in his mind.

In order to hide his disappointment, Cyrus busied himself by untying and retying his shoelaces. In his case, they could never be knotted too tight! It was a good distraction, too, from all the surrounding rambunctious students that were making his stress levels rise unnecessarily.

When the remaining students finally joined their peers in the gymnasium, dressed and ready to go, their gym coach stormed in with a clipboard in his hands.

Instead of waiting for them to settle down their chatter naturally, he blew sharply into his whistle, and the noise pierced the air with its shrill tone. Cyrus winced at the sound, and he shrinked back as the coach glared at all of them. He didn’t think he’d ever seen the coach so mad. Well, except for yesterday, he added in his mind.

“Everyone quiet!” the coach demanded, causing a group of eighth-grade boys to pause in their obnoxiously loud conversation. They smirked at each other, not seeming to care about their obviously frazzled coach. “Because of an incident that occurred during yesterday’s game of flag football,” Coach Anderson said, shooting a not-so-subtle glance at the boys that were just talking, “Dr. Metcalf has requested that I assign teams instead of allowing you to do it yourselves.”

At first, the students were baffled into silence. They weren’t allowed to pick their teammates? It was the most absurd thing they had ever heard! Then, all at once, the middle schoolers outburst at the new rule, causing chaos within the spacious gym room.

“You can’t do that!”

“That’s not fair!”

“Why should we all get punished?”

A jumble of complaints and cries about the coach’s decision went on and on, and Cyrus prepared his ears. He didn’t have to be a genius to predict what was going to happen next: one, two…

The coach blew whistle, effectively silencing the middle school students. “Enough!” Coach Anderson barked as the middle schoolers covered their ears in discomfort. “Let’s get this show on the road, shall we?” As the students shuffled nervously, shifting from foot to foot in anticipation, the coach began to call out groups. “Team 1 is Andi, Gus, Denise, and Jonah.”

Cyrus gulped, and his panic began to rise in his throat. How had Andi and Jonah been put together but not him? And what was he going to do? What if he got stuck with someone he didn’t know? Or even worse…someone who would tease him…

Cyrus tried to shake his worries away, albeit unsuccessfully. Why was he born with a tendency to worry about everything?

He glanced over at T.J., and he longed for the boy to be on his team. T.J. always knew how to make him feel calm with his presence (except when Cyrus allowed himself to get worked up about his feelings for the boy), which was a welcome change from the constant anxious frenzy inside of his mind.

As the coach continued down the list, Cyrus got more and more distressed. He had originally hoped that he would get paired with some of the classmates in his grade (at least he’d know them), but most of them had already been called. Even T.J., his last hope, had been assigned to Team 4. The day seemed determined to be a nightmare specifically designed for Cyrus to endure, and painfully so.

After calling a few more names, Coach Anderson finally gave the answer to the question that Cyrus had been uneasily waiting for. “Team 6 is Cyrus, Kyle, Aaron, and Cameron.”

Cyrus felt his stomach clench. He had never even talked to any of these boys, but he had a feeling that they wouldn’t be too accepting about having him as their teammate.

Aaron was the only one out of the bunch that was from his grade, although they had never talked. Aaron seemed decent enough, from what Cyrus could tell. He was quiet, and he kept to himself, but that wasn’t a bad thing.

Cameron, on the other hand, was a different story. Cyrus hadn’t talked to him either, but he knew that Cameron was the captain of the soccer team. From the horror stories that Cyrus heard about him through Buffy, he was even more ruthless than T.J. had been just a few months ago.

Even so, Kyle was the most callous of them all. In fact, Cyrus and the rest of his peers had witnessed the boy’s cruelty first-hand during flag football yesterday.

It had started out as a normal, innocent game; Buffy was dominating as usual, Jonah was attempting to follow Buffy’s strict commands in order to appease her (she was the team captain, after all), Andi was continually trying to keep up with their teammates (how exactly did one play flag football, anyway?), and Cyrus was cowering in the corner in order to stay out of everyone’s way. He wasn’t really sure how to play the game, and it looked too intense to actually partake in. And there was a lot of running. He couldn’t deal with lots of running.

However, the one rule Cyrus did know about the sport was that there was no tackling allowed. But, as the game progressed, it was apparent that this rule was not being followed by his classmates. By the end of the class, one kid had a bloody nose and the other had her glasses broken beyond repair. ��All because of Kyle and his corrupt band of jerk friends.

When inquired by Coach Anderson and Dr. Metcalf, Kyle played off his offense as ‘an accident,’ claiming that him and his buddies had gotten excited in the midst of the game and tripped, crashing right into their poor victims. Dr. Metcalf and Coach Anderson suspected foul play, but because there was no evidence to support their suspicions, they were forced to go along with it. However, this clearly was not stopping their principal from taking the matter into his own hands.

“Cyrus?” Andi asked, nudging him. Cyrus shook himself from his thoughts. When had she shown up beside him? “Are you going to be okay?”

Cyrus glanced worriedly at the coach, who was already chastising a student that had requested a switch. He frowned, but tried to hide his trepidation from his best friend. You’ll be okay. “I’ll be fine,” he insisted, reiterating his own thoughts aloud. He wasn’t sure who he was trying to convince more: Andi or himself. “Go have fun with Jonah.” Cyrus forced a smile upon his face, but he could tell that she saw the insincerity behind it.

She looked questioningly at her friend. “Are you sure?” she asked. “I can talk to Coach Anderson if you want…,” Andi offered unsurely. Her eyes wandered over to the coach, and Cyrus saw her corners of her lips dip down as she watched the teacher reprimand their classmate.

“It’s fine,” Cyrus promised, feeling his stomach churn even more. He couldn’t believe he was going through with this. “Go, I’ll be okay.”

Andi gave him one last worried glance before squeezing his arm. “Good luck.”

Cyrus bit his lip as she jogged away, running towards her teammates. He needed more than good luck for what he was about to endure.

As Cyrus began to stroll over to his own teammates (reluctantly, he might add), he took deep breaths, only focusing on taking one step at a time. Right foot, left foot, right foot… He was so concentrated on walking that he didn’t even realize when he bumped into Kyle. At the contact, he ricocheted off of the boy’s freakishly tall body like a pinball in a pinball machine, and he stumbled backward, barely managing to catch his balance.

“Watch where you’re going, Goodman,” Kyle said cruelly, still chuckling. Cyrus ducked his head to hide his bright red cheeks, and he silently cursed his entire existence. Why did he have to be so clumsy?

After he got his brutish laughter out of the way, Cameron nudged Kyle. “Come on, man, let’s get started!”

Kyle agreed. “Okay, how about me and you versus Owens and the dweeb?” Cyrus winced when the bully referred to him as ‘the dweeb’. More than anything, he wished that Buffy were here to defend him. Even if he hated confrontation, being insulted to his face stung more.

Cameron shrugged. “Sounds good to me.”

As the team began to play two-on-two, Aaron and Cyrus versus Cameron and Kyle (like the latter had arranged, with no objection on Cyrus or Aaron’s part), Aaron tossed the ball to Cyrus, who hurled the ball towards the basket as well as he could possibly manage. The basketball missed its intended target completely, landing pathetically three feet away from the goal.

Kyle snickered at the sight as he plucked the ball in one fluid motion, and Cyrus almost envied his gracefulness. “I bet you can’t even hit the backboard!” he taunted, laughing harshly. Cyrus grimaced at the sound. He wasn’t one-hundred percent sure what the backboard was, but he was certain that whatever Kyle had just said wasn’t a compliment. “Why do you even take gym if you’re such a girl?”

Cyrus resented his comment, and not just because Kyle was insinuating he was girly. Taking gym wasn’t even a choice. If it had been, Cyrus would’ve definitely would’ve taken any other class. He tried to point this out, too. “Actually, it’s a state requirement-” he tried to input. Before he could finish his statement, he was cut off by Cameron.

“What a loser,” the boy remarked, sniggering along with Kyle. Those two had sure become fast friends, Cyrus noted. If only they hadn’t bonded over making fun of him.

Cyrus looked helplessly towards Aaron, but the boy wouldn’t look him in the eye. Aaron’s reluctance to help him made his throat tighten, and tears pricked at his eyes. How was he going to handle anymore of this by himself?

As Kyle and Cameron bickered about who’s turn it was to check the ball (whatever that meant), Cyrus took a deep breath to calm his nerves. You can do this, Cyrus, he assured himself. Just ignore them.

It was easier said than done. While Cameron was trying to pass the ball to Kyle, Cyrus shuffled across the gym floor awkwardly, hopping from side-to-side. He wasn’t trying to block Kyle from receiving the ball; in fact, he was trying to get out of Kyle’s way so that he didn’t have to encounter his wrath, or be his next victim of PE crime. However, in the midst of his getaway plan, Kyle stuck out a leg, causing a clueless Cyrus to trip and stumble onto the hard gym floor below with a loud thud.

Cameron and Kyle chortled at the sight, both exchanging a sadistic smirk. “Look, he can’t even stand up without falling over!”

Cyrus squeezed his eyes shut, wishing that he could be somewhere, anywhere else other than right here at this very moment. Their grating laughter consumed his senses entirely, and he almost missed the squeaking of sneakers echoing from the gym floor behind him.

When Cyrus felt a hand come down on his shoulder, he apprehensively opened his eyes, seeing none other than T.J. Kippen himself staring down at him with a worried expression, his lips dipped downward and his brow furrowed.

T.J. bent down to his level, maintaining eye contact with the boy in front of him as he did so. “Are you okay?” he asked Cyrus in a quiet, yet urgent, voice. Cyrus felt a sense of security wash over him as he stared deeply into T.J.’s gorgeous green eyes, and he felt a warm tug in the pit of his stomach. No. Please help me. I need you.

When he opened his mouth to answer him, Cyrus found that no words would come out, so he settled for a trembling shake of the head. At that single motion, T.J. rose, bringing Cyrus up with him.

“What did you guys do to Cyrus?” he asked accusingly. His hand never wavered from Cyrus’s shoulder, and Cyrus gulped as the butterflies in his stomach swirled uneasily.

Kyle put on an innocent facade, speaking fluently without guilt. “I have no idea what you’re referring to, T.J.,” he said, giving an easy-going shrug. Cyrus couldn’t decide if this kid was a good actor or a pathological liar; probably both. “Goodman here just has a little trouble with sports. I think he’s a tad girly. Or should I say she,” he joked, getting Cameron to laugh along with him. Cyrus felt T.J.’s grip on him tighten in anger, and he wished that he could grab the basketball player’s hand to help comfort him in return.

“Says the guy who didn’t make the basketball team this year,” T.J. shot back. Kyle choked during his fit of laughter, and his face turned an angry red at T.J.’s comment. Someone has a bruised ego, Cyrus thought to himself.

“You’ve become so lame since you’ve been hanging out with this loser,” Kyle sneered in retaliation.

T.J. was clutching onto Cyrus so tight that he was bunching up the boy’s gym uniform in his hand. “You guys are the losers,” he retorted, releasing Cyrus of his grip. “Come on,” T.J. urged him, seizing his hand defensively. “You’re playing on my team today.”

Cyrus was completely floored. It was one thing for T.J. to risk his reputation for him, but for him to risk getting in trouble, too? It was too hard to comprehend. “But…Coach Anderson said-”

“I don’t care what Coach Anderson said,” T.J. interrupted, tugging Cyrus forward. He paused in his tracks, consequently causing Cyrus to stop in front of him, only mere inches from his face. T.J. searched Cyrus’s eyes, and the basketball player’s mouth melted into a gentle, sweet smile that made Cyrus’s heart leap in his chest. “You’re playing on my team today,” T.J. confirmed, as if to relieve any of the lingering anxiety in Cyrus’s mind.

Cyrus took a deep breath before relenting. If you say so. “I’m playing on your team today,” he repeated, the words passing softly from his lips. Maybe Cyrus had a newfound appreciation for basketball day after all.

*sighs dramatically* WHEW! Glad I finally finished writing that. I’ll be working on my other prompts, and I’ll try to get those done for y’all soon. Thank you so much for reading this prompt and don’t forget to comment below or to read it on AO3 or fanfiction.net. Thank you!

~emmagrace13

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Are there any other American students with trauma from school shootings or something of that calibur?

Like, it doesn’t matter what grade you’re in. Your English teacher cries when it sounds, telling you they’d die for all of you, and you look around the room deciding who you would die for. You keep your phone on silent all the time. Your teacher from Algebra 1 tells you it’s okay to fall asleep in class the day after a hard lockdown drill. You don’t go to the bathroom during school. Your first instinct when you see police at your school is to come out, crying, with your hands in the air, fingers separated.

My grandma took me to laser tag with my brother and a bunch of random strangers, and nobody understood why, any time someone aimed the bullet line at me, I rolled to the side and hurriedly tried to shut off my phone. My team called me a coward. I didn’t have the bravery to tell them that no, I’m not, I have trauma.

My brother was too young to really remember it. He says that he just remembered that he didn’t have to do his homework that day and that I came home an hour late, crying, because someone took me for investigating at the age of seven.

All drills now cause kids to cry. Any time the PA turns on at an unexpected time, we all silence ourselves until they say something other than “we are going into hard lockdown, locks, lights, out of sight” and the class is terribly close. We couldn’t bear to lose each other, even the ones we ‘hate’. We aren’t allowed to walk around the school alone. On top of the fact we need hall passes to go anywhere, we had to bring a few people with.

Your teacher tells you ‘go ahead and sleep during class. Cry during a lesson. Don’t do your homework for a while. I won’t count it’ or ‘Alright, today we’re talking about-’ before bursting into tears and giving you free time.

The only school shooting experience I remember was when I was seven, and I didn’t do my homework for a week after.

And, you know how most middle schoolers joke about wanting to die, and stuff like that? My school doesn’t do that. Mainly because we’re scared it will actually happen and we won’t be able to protect someone else.

A locker slammed on the second floor of my school near our end of the hallway, and all the seventh and eighth graders who had been in that shooting ducked and grouped together. The only people who didn’t were the new kids. They just looked at us like we were insane. They assured it it was just a locker. The fire alarm rings, but nobody moves. A trap? A drill? Nobody knows. We all are closer as a class now, especially the kids who would take the time to stand up in front of somebody that they cared about.

I think it makes me terrified because I’ll never be the one to help someone. On one account, I’m short and lightweight. On another, I get scared out of my wits WAY to easily.

So. That’s my story. Share yours.

1 note

·

View note

Text

School Should Be An Opportunity

Okay, so I want to put something out that I view as important so I’m just gonna leave it here - take is as you want to.

Whenever I have geometry homework, my mom tells me she never had to do it. My parents also tell me that at least 60% of what they learned in high school was never needed after the test. What if High School was different?

What if you were only required to do math until you completed algebra 1? What if you only had to take Social Studies until the end of eighth grade? What if English was the only current class required until high school graduation?

Hear me out, other classes are important to everyone for general knowledge - until about 8th grade. English, however, is learning about your own language and so it is probably considered very important, so that’s why it should stay.

The only other required class for high school (assuming algebra 1 has been completed) should be a life management class. A class to learn about things like taxes, bills, how to get a job, discussion on important things of today’s world and so forth.

After those, there would be 5 or 6 classes open for the students’ choosing (depending on how many classes your school has... mine has eight.) To choose those classes, students should have a guidance counselor who they can meet with to discuss what they want to do with their life. The counselor could recommend classes and help the student find classes that interest the student. The counselors could also tell them if there are any classes that they would be required to ake for the profession they are after. And from there they could select classes. If the student wants to take a science, math, social studies, or any other class that we have to take currently then fine. If that’s what they need or are interested in then they should take it. But if they need band or choir or music composition or photography or computer science, then they should take those classes and classes relating to that.

Some people are concerned that students would be irresponsible with this freedom, which is why counselors should help. Parents could also be required to give consent to the courses selected by their child if it is that big of a concern or issue. This way the student is prepared for what they want and can explore more classes that interest them.

And what if the student changes their mind and wants to do something else with their life? Fantastic! They can choose different classes that fit their needs for the path they want going forward.