#street brawl

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

join majima construction and nothing will go wrong, probably!! it's definitely not the remnants of a recently dissolved yakuza family! and it's only like a 50/50 that your boss will make you defuse a bomb. don't worry about it. (from [x])

#the street brawls are also a plus. obviously.#yakuza#ryu ga gotoku#majima goro#yakuza fanart#contra art#fanart#comic#nishida yakuza#daisaku minami#goro majima#minami daisaku#nishida#rgg fanart#rgg#not meant to be any sort of au thing the third panel's just like that for contrast but it can be if you want it to be :] heart

643 notes

·

View notes

Text

Out of every fantastical thing in Arcane, the most unrealistic thing to me is Sevika not killing Caitlyn in 2 seconds

#multiple times she has her by the neck and then just. holds her there. for several seconds.#instead of immediately crushing her head like a melon with her gigantic robot claw arm#privileged sniper princess vs 6 foot beefy street thug who knocks heads for a living have a brawl. who would win?#sevika#caitlyn#arcane#arcane season 2#arcane league of legends#arcane netflix#arcane s2

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

#burlybrawlers

#burlybrawlers#fighting#fight#fighter#wrestler#bare knuckle fighting#Bare knuckle boxing#Street Photography#streetbeefs#street fighter#boxing#beefy man#huge man#thick man#stocky man#heavyweight#gay bear#brawl#Brawlers

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

drawing dead SSB memes because it’s what 13 year-old me would’ve wanted

#artists on tumblr#super smash bros#super smash brawl#super smash ultimate#pokemon#Incineroar#street fighter#star fox#wolf o'donnell#jigglypuff#toon link#digital art#fan art

147 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#marshall d. teach#blackbeard#blackbeard pirates#one piece#whitebeard pirates#my art#so sometimes i think about how teach stayed on WB ship for close to 30 years#now i know he was fighting and doing his part but still he never tried particularly hard and he was basically living under his dads roof#for his entire adult life#and would have continued to do so if not for the yami yami no mi#anyway after talking with a friend it got me thinking about him as a neet so there#really loose concept and this is just me procrastinating but kind of funny i thought#neet au#about marco since someone mentioned. since he was ship dr and 1st commaner i wouldnt consider him a neet#marco had a lot of responsibilities while teach was just a regular member#so marco would be the more mature and successful older bro#anyway with this i finally drew bb with tired eye bags#like this man doesnt sleep. he should look tired as hell#i feel like im going crazy#i want to draw highschool luffy and discord mod teach having a brawl on the street

857 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ron and Merlin trying to parent teenage Jake and nothing works. Taking things away does nothing cause Jake is used to having nothing. Grounding him doesn’t really work cause it’s not like Jake has any real friends and the only place he goes is the academy and he has to go with Merlin (he’s 17 and the government fears if they let him live in the dorms that he’ll disappear so thus he has to live with slider and Merlin at their home his first year).

Not entirely sure on how they figure it out but they find out the only real thing Jake responds to is air jail.

Yes, air jail. Like you would do with cats.

Jake is like 5’6”-5’7” meanwhile slider and Merlin are both over 6 foot.

So Ron just wandering through and snatching Jake up when Jake’s trying to start shit with the son of an admiral whose family is over for a dinner. And Ron being just like ‘nope we’re not doing this’ cause Jake has started fist fights with other people this way. So Ron just acts like he’s walking by and swoops him up and under his arm like a football. And it momentarily stuns him like when you put a towel over a cat.

So Ron just walking out into the backyard with Jake trying to wriggle out of Ron’s hold before he eventually just gives up and just hangs there.

Jake is well behaved the rest of the night.

Merlin days later asking Ron how he got Jake to behave that night and Ron just showing him a video of someone doing air jail to a cat and being like “this, air jail. He’s basically a cat so this”.

#so in my head Ron loves to work out even if he’s not active navy anymore#Jake is also still kinda malnourished at this point so he’s easier to pick up#this eventually evolves into Ron and Jake grappling in the backyard when Jake’s anger issues flare up#Ron was a wrestler in high school and at the academy#Jake fought on the streets to survive and definitely got into brawls in juvie#Merlin supervises and has to instate a rule about no sharps after Ron and Merlin figures out that Jake carries knives out of habit after one#falls out mid grappling session#juvenile delinquent Jake au#jake hangman seresin#ron slider kerner#Sam Merlin wells

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

disaster couple doomed to fail been torturing my thoughts

#artists on tumblr#street fighter#sf6#ed street fighter#sf6 avatar#fanart#comic#chrys#chrysed#oc#sketch#colored#theyre so fun mostly because theyre both messes sdfjdsk#do they have fun. yes. are they beneficial to each other. yes.#are either of them fit to be in a relationship rn NO#THEY ARGUE ALL THE TIME AND HALF THEIR DATES END WITH THUG BRAWLS ANYWAY & CHRYS IS LUCKY SHE DOESNT END UP DEAD JUST FROM BEING AROUND HIM#YES THE BREAKUP IS VERY MESSY

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

#goofy#goofy goof#big bird#sesame street#mickey mouse#fist fight#brawl#tumblr polls#polls#random polls

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

elena nation, we fucking won!

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

bro lost the fight so hard the crocs where trying to run

#funny content#funny tumblr#funny#best memes#ash posted it#alabama#riverfront#street fighter#black tumblr#brawl#Alabama riverfront#riverfront fight#alabama brawl

283 notes

·

View notes

Text

love having neanderthal brow bone i get to fuckinf destroy these mfs with ease. slam ur head into someone elses face no one sees it coming

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

#burlybrawlers

#burlybrawlers#fighting#fight#fighter#wrestler#bare knuckle fighting#bare knuckle boxing#street photography#streetbeefs#street fighter#boxing#beefy man#huge man#thick man#stocky man#heavyweight#brawl#brawlers

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

#who would win in a fite#polls#tournament tuesday#tt8#linda belcher#bobs burgers#brooklyn 99#Rosa Diaz#new jersey street brawl

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ryu from Street Fighter

#cou#street fighter#ryu street fighter#capcom#super smash ultimate#super smash bros#super smash brawl

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is the day. Another 11th August, another reblog! It's been 248 years today.

11 August 1775: A Bostonian Boxing Match

The backstory to the event described below, condensed into meme-format.

Today, I want to share a curious and largely forgotten episode from the year 1775 with you, which occurred on this very day 246 years ago. It has everything a good story requires: a gripping fight-scene, an astonishing backstory and colourful characters.

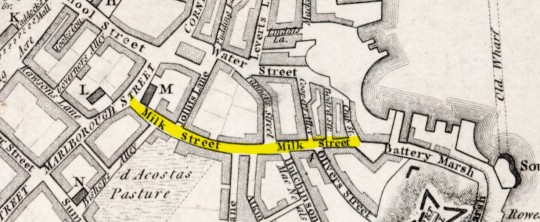

Allow me to take you to Milk Street in Boston on 11 August 1775:

At the time, British admiral Samuel Graves was tasked with enforcing the Boston Port Bill, meaning he was in charge of blockading the harbour and making sure (or at least trying to) no civilian vessels could leave or enter the same.

With Boston thus in a precarious supply situation, Benjamin Hallowell (1723–1799), Commissioner of the Board of Customs, was anxious to find ways to feed his livestock and leased one of the islands off Boston, Gallops Island, to cut the grass there to turn it into hay. What follows is a month-long (rather entertaining) back and forth that eventually culminated in a fracas.

All ye fans of 18th century drama, proceed under the cut.

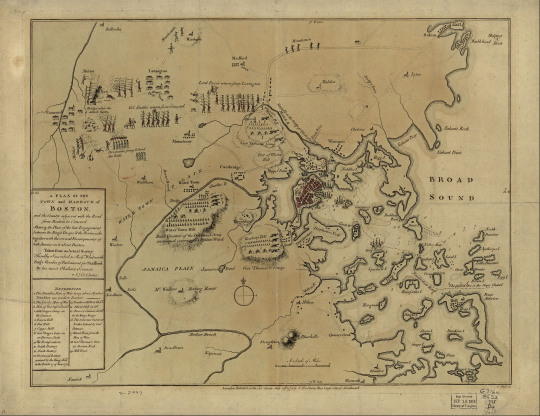

1775 map depicting Boston and its environs during the Siege of Boston and the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

3 July 1775

In order to be allowed to leave Boston via boat to go to Gallops Island, written permission from Admiral Graves was required, which Hallowell applied for but was denied. He later related to General Gage in a letter that Admiral Graves gave him advice to cut hay on either Noddle's, Grape or Thompson's island, which Hallowell understandably didn't feel like doing, seeing as he had already leased a whole island for the exactly same purpose.

Now, the whole thing is more complex than it looks from the outside; Hallowell would quite likely have required the protection of the Royal Navy (seeing as he asserts that there had been prior incidents on other islands where the interception of 'rebels' had prevented the making of hay, or the same had been burnt to render it useless) and Graves, who received letters upon letters to the effect of "please sent us a ship to [insert town here] as soon as possible we really need protection over here" almost daily without having the men, ships or supplies to do so, probably didn't consider a single disgruntled individual very high on his list of priorities.

Graves, hinting at the need for military protection of such a venture, pretty much refused but told Hallowell he would have to consult General Gage on this matter and give him a reply the following Wednesday, 12 July.

Hallowell didn't like that because he thought the quality of the grass would suffer if not cut right away, which Graves negated, but then agreed to get back to him on the 5th.

Benjamin Hallowell (l) and Samuel Graves (r).

4 July 1775

Hallowell however did not like having to wait a single day longer and in turn went directly to General Gage himself who told him that he didn't see any issue with the request- prompting Hallowell to immediately after pay a visit to the admiral who at first seemed obliging, but, according to Hallowell's own narrative, told him he still wouldn't give him permisson to go to Gallops Island because he wanted the hay for himself: "Do You Know Sir- that I have five horses and three cows and must have hay?"[1] In the ensuing back and forth, Hallowell alleges that Graves offered to go halfsies but angrily told a refusing Hallowell that "if I can't have half the hay you shall not bring it off the island."[1] For a parting shot, an enraged Hallowell insinuated Graves wasn't treating him like a gentleman, an accusation that would set the tone for their future encounters.

Detail of a 1775 map of the Battle of Lexington and Concord and the Siege of Boston. Gallops Island is circled in red, the alternatives proposed by Admiral Graves in blue.

6 July 1775

Brushing over the fact their conversation had turned rather nasty, Hallowell tries again, this time sending a letter to Admiral Graves.

7 July 1775

Graves received a second letter by Hallowell, asking for a reply. Earlier in the day, Hallowell had sent a servant to inquire at the admiral's for a reply, but informed there wasn't any.

9 July 1775

You may guess what happened to the second letter: once again, Graves treated Hallowell to the 18th century experience of being left on read. Hoping to finally get a reply out of the man, Hallowell reluctantly informed Graves in a third letter that he would go along with Graves' proposal of splitting the hay.

20 July 1775

Hallowell tried to get himself and his men onto the island, but was stopped by Captain Hartwell of HMS Boyne (coincidentally a pal of the admiral's), resulting in another Strongly Worded Letter being sent Graves' way, which ended in the following paragraph:

Are we not sufficiently oppressed by the enemies without, but must suffer by those who are sent for our protection? - as an officer of the crown therefore I demand by what right you thus Continue to deprive me of my Property?[2]

27 July 1775

Who wants to guess if Graves replied? You're correct, he didn't. Which is why Hallowell tried to get General Gage involved, asking him to step in and talk to Graves, whom he refers to as "that gentleman" at one point, in his stead.

This is the last document in the build-up to the main event I know of, so, without further ado:

11 August 1775

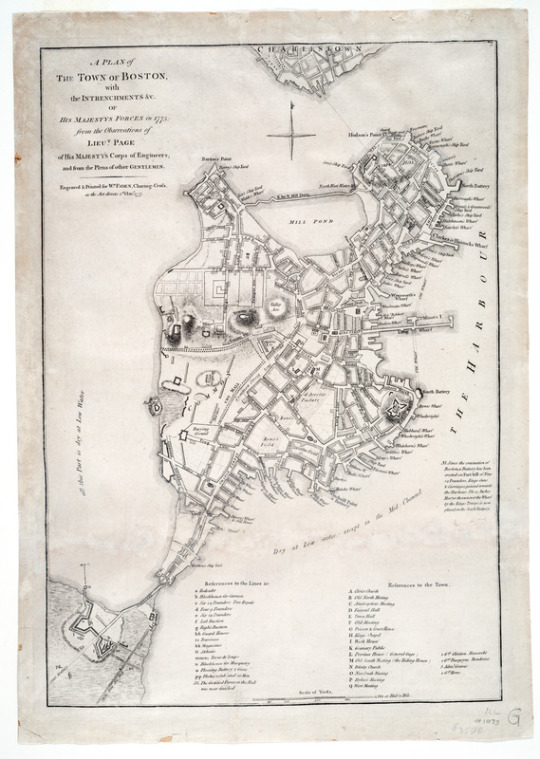

A 1775 plan of the city of Boston, showing many of the streets and places relevant to the events of 11 August 1775 and their aftermath.

There are several reports of what happened on that day; one by Hallowell, which, if you read it, makes logically the least sense as it's quite clear he edited some things for his benefit, and two by eye-witnesses of which the one printed in the London Chronicle in their 31st October– 2nd November[3] is the most detailed.

More importantly, the author, who aside from being and an eye-witness to the affair is only identified as a "gentleman", takes care to distinguish between relating the events and his personal opinion on them, giving this account an air of nuance and credibility Hallowell's version, which paints Graves as the sole aggressor, lacks.

According to this version of events, Samuel Graves was walking down Milk Street on his way to General Gage's when Hallowell stopped him in the street, asking why he hadn't replied to his letters. Graves brushed him off, wanting to continue on his way, but Hallowell was not so easily deterred. Once again, he cut the admiral off.

Milk Street. Detail from the above city plan [highlighting by me].

This is where things turn nasty. The admiral replied just the same as he had before, which marks the end of Hallowell's month-long fuse: enraged, he informed Graves that "you are no Gentleman but a Scoundrel", which within the context of (the perception(s) of) personal honour and the social value ascribed to it was a pretty severe insult.

Graves' retaliation came swiftly: "hitting him a very slight slap in the face", Graves afterwards reached for his sword, drawing it, presumably with the intention to give Hallowell a warning not to insult him again seeing as he put it back into the scabbard immediately and proceeded on his way when Hallowell, shouting for someone to give him "a stick, a stone" followed him once again, the asked-for stone in hand.

And indeed, Graves stopped, presumably, as the author speculates, because he expected Hallowell to formally challenge him. Instead, Hallowell leaned in close, and supposedly whispered the words "you are a damned scoundrel" into his ear.

Not exactly known for his patience, Graves struck Hallowell a second time, this time "across the nose with his knuckles so as to make the blood trickle" and the game was on. People who had formerly been mere spectators joined in, allowing Hallowell to get to Graves' sword in the ensuing scuffle, which was luckily spotted by a soldier who tried to wrench it from Hallowell, causing it to break.

The eye-witness states that he doesn't think Hallowell would actually have stabbed Graves- moreover, he thinks Hallowell had deliberately tried to provoke a "mobbish affair" instead, a claim he bases on the fact Hallowell had come without his own sword.

If Hallowell truly thought he'd stand a chance against Graves in a match of no-rules-apply-street-brawling, he was apparently much mistaken. Our Bostonian informant recounts that

it looked to me if it had not been for the mob, the Admiral, although he must be near 60 [he was 62], would have drubbed Mr. H----ll confoundedly, notwithstanding he is a stout young man of 34 or 35 years of age; as it was, he was blind for a week as they told me.

Although the eyewitness claims Hallowell was lucky there were people holding Graves back from beating him to a pulp, other reports of the time make mention of the fact that Graves apart from losing his sword nursed a black eye or even two- the latter of which I am not quite prepared to believe, given that, assuming we're talking panda eyes (periorbital ecchymosis), there is no evidence to suggest Graves may have suffered a basilar skull fracture as a result from his fight with Hallowell. In fact, judging from his correspondence in the days after the incident, he appears to have simply kept calm and carried on.

The Aftermath

The pro-Graves faction insinuated that Hallowell's anger at Graves sat much deeper, namely because Graves court-martialled one of his brothers' in law, a naval captain, for disobedience once and stated that the impossibility of protecting such a venture with what scarce military resources Graves could muster aside, Graves had considered it unfair for one individual to get the chance to get to do something everyone else wouldn't.

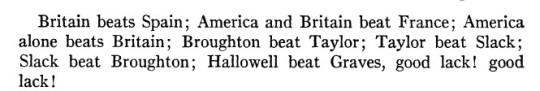

The pro-Hallowell faction meanwhile claimed the direct victory in the street-brawl for themselves. Perhaps due to Graves' spectacular unpopularity, their voices were heard much more readily and curiously, despite this having been a spat between a loyalist and British official and a British admiral, the Boston Gazette (with contributors such as Paul Revere and Samuel Adams, you have an idea where the paper stood politically) chimed in, too, publishing this little ditty:

Boston Gazette, issue of 21 August 1775, reprinted in: French, Allen. November Meeting. The Hallowell-Graves Fisticuffs, 1775 (1930).[4]

In this remarkable verse, the author essentially claims Hallowell as an American hero despite the fact he was a loyalist. To add some context, Broughton, Taylor and Slack were three of the most famous British boxers of the mid-18th century. "Britain beats Spain" refers to the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) and "America and Britain beat France" to the North American theatre of the Seven Year's War (1754-1763). "America alone beats Britain" is quite evident and goes hand in hand with "Hallowell beat Graves", making the fracas into a mini-rebellion in its own right, which the Americans already won.

This has not been explored in any articles on the matter, but what may also have been important is the imagery the fight created; in art, a broken sword symbolises defeat and dishonour; to illustrate this, think for example of this rather well-known posthumous portrait of Richard III or this 1750s satirical print of John Byng, to name just two examples. Graves with his broken sword quite simply looked like the loser and perhaps the broken sword may have been read not just in a symbolic, but in a prophetic way in relation to his position as well.

The Graves' Retaliate

Despite public sympathy obviously being rather more with Hallowell than Graves, the former did not live quietly in the days and weeks following the fracas; Graves, who enjoyed a very close bond with his nephews whom he supported and was quite protective of, now in turn saw them come to his defence. They went, in fact, what is commonly called apesh*t these days.

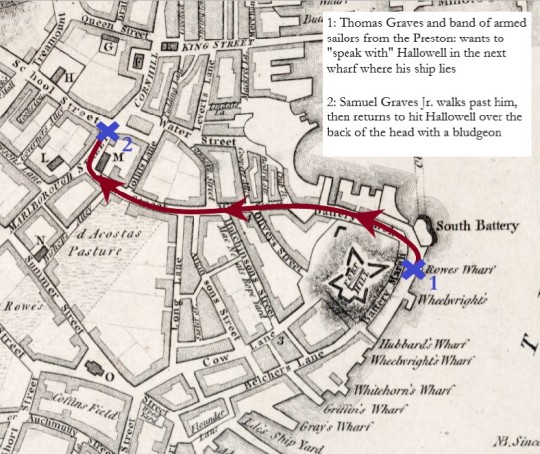

At first, Thomas Graves (c. 1747–1814) took it upon himself to send Hallowell two consecutive challenges for a duel, which Hallowell of course didn't accept. Thomas however wouldn't let matters slide just so easily, and according to Hallowell's letter to Gage on 2 September, this happened to him earlier in the day:

[...] at Rowes wharfe, I perceived that Mr Thomas Graves accompany'd by the Boatswain of His Majestys Ship Preston, with two or three other decently dressed persons, and Several Sailors had posted themselves in such a manner as to prevent my return, Mr Graves besides his Sword had a large bludgeon in his hand and some of the others had sticks - As I approached towards them Mr Graves advanced Several paces, and desired to know why I had not met him in consiquence of the messages he had sent me, that he wished to speak with me on the same business, and desired me to retire withhim to the next wharfe, Where the vessel laid which he now commands [...].[5]

As a little aside, I cannot help but find it rather ironic that Hallowell got a taste of his own medicine- being held up in the street for ignoring letters. That said, Hallowell didn't bring a mob of loyal sailors and the fact everyone was armed also makes it plain Thomas' intentions for Hallowell were far more sinister than an impromptu scuffle. Thomas Graves was in fact court-martialled for his behaviour, but given his rather remarkable later career, this incident is pretty much forgotten.

Just a short walk away from the wharf, Hallowell was ambushed in a street by Thomas' older brother Samuel Graves Jr. (c. 1741–1802) who hit him over the head with a bludgeon and later sent him a challenge as well.

Contemporary map with Hallowell's probable route on 2 September 1775 and the places where he encountered Thomas and Samuel Graves Jr. [additions are mine].

From then on, things turn fairly quiet all of a sudden; I would guess seeing as he was intent on helping his nephews to become able, successful officers, the admiral called Thomas and Samuel to order.

Hallowell in his letter to Gage insinuates not exactly subtly that Graves may have known and approved of his nephews' behaviour, or even sent them; personally, I don't think this is likely because as stated above, he would not have wanted them to jeopardise the budding careers he spent time and his personal reputation in building. Additionally, the admiral was particularly close with Thomas (so close in fact Thomas moved to live close to his uncle and his only daughter became pretty much the grandchild Samuel Graves never had), so I would consider it possible for Thomas (and Samuel) to have acted out of feeling the need to 'protect' their uncle- perhaps also because they thought they would stand a greater chance at winning a duel than a portly sixty-two-year-old who had had a major health scare (a severe "fit" of no more precise description) just the year prior.

If anything, the Band of Brothers Graves taking matters into their own hands only manifested the impression of Graves as a nepotist and added to the unfavourable opinion of him in Boston.

Conclusion

...and the hay, you ask? As far as I can tell after digging into this curious episode of Bostonian history, it is not recorded what happened to the grass on Gallops Island, whether it was mown or not, and of course, by whom.

Both Hallowell and Graves have sunk into relative obscurity and are more or less only remembered in connection with their children (biological and in spirit): both Benjamin Hallowell Carew (1761–1834) and Thomas Graves went on to become hugely successful naval officers under Nelson; Hallowell served with Nelson at the Battle of the Nile (1798) (and presented him with a coffin made of the wood of the French flagship L'Orient... Nelson loved the present, by the way); Thomas Graves distinguished himself as Nelson's second-in-command at the Battle of Copenhagen (1801).

One wonders if the two knew and associated each other with the 1775 incident.

As to the Graves-side of things, Samuel certainly was not the last of his family to be involved in a somewhat curious dispute over the use of agrarian products in a specific area; in 1805, his godson John Graves Simcoe was involved in a dispute over who the dung left behind by the horses of the local militia belonged to. He was challenged by Lord Rolle, the other party considering himself the rightful owner of the horse droppings, who proposed a fistfight to settle matters. Simcoe however (perhaps as much due to his severe health-issues that included gout in his hands as generally not wanting to engage in an activity that could be perceived as ungentlemanly) declined. ...If Samuel would have had he been in his godson's place, will forever remain a matter of speculation.

Footnotes:

[1] Narrative of Benjamin Hallowell, 4 July 1775, in: Clark, William Bell (Ed.). Naval Documents of the American Revolution (1). Washington 1964, p. 814.

[2] Benjamin Hallowell to Vice Admiral Samuel Graves, 20 July 1775, in: Clark, William Bell (Ed.). Naval Documents of the American Revolution (1). Washington 1964, p. 935.

[3]Anonymous. An Account of the Fracas Between Vice Admiral Graves and Benjamin Hallowell, One of His Majesty's Custom Commissioners, originally published in: London Chronicle, issue 31st October– 2nd November 1775, Clark, William Bell (Ed.). Naval Documents of the American Revolution (1). Washington 1964, p. 1119–1120.

[4] French, Allen (1930). November Meeting. The Hallowell-Graves Fisticuffs, 1775; Letters from Benjamin W. Crowninshield; Schuyler Colfax to Samuel Hooper. Massachusetts Historical Society (63): 22–51, p. 34.

[5] Benjamin Hallowell to Thomas Gage, 2 September 1775, in: Clark, William Bell (Ed.). Naval Documents of the American Revolution (1). Washington 1964, p. 1292-1293.

Literature on the subject:

French, Allen (1930). "November Meeting. The Hallowell-Graves Fisticuffs, 1775; Letters from Benjamin W.Crowninshield; Schuyler Colfax to Samuel Hooper". Massachusetts Historical Society (63): 22–51, p. 34.

Source material:

If you are interested in reading more about the Hallowell-Graves-affair by engaging with primary sources, I recommend the Naval Chronicles of the American Revolution, vol. 1 (see footnote 1). All 13 volumes published so far are available for download for free.

Maps:

De Costa, J, and Charles Hall. A plan of the town and harbour of Boston and the country adjacent with the road from Boston to Concord, shewing the place of the late engagement between the King's troops & the provincials, together with the several encampments of both armies in & about Boston. Taken from an actual survey. London, 1775. Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress [accessed 10 August 2021].

Page, Thomas Hyde, Sir, and Faden, William. A plan of the town of Boston, with the intrenchments &c. of His Majestys forces in 1775 : from the observations of Lieut. Page of His Majesty's Corps of Engineers, and from the plans of other gentlemen. London 1777 (printed). Map reproduction courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library.

Image credits:

Benjamin Hallowell Jr. by John Singleton Copley, c. 1764, in the collection of the Colby College Museum of Art [accessed 11 August 2021].

Can I Copy Your Homework template [accessed 10 August 2021].

Samuel Graves by James Northcote, Wikimedia Commons, photograph by Christie’s [accessed 11 August 2021].

#samuel graves#benjamin hallowell#boston port act#1775#american revolution#revolutionary war#amrev#cw mild violence#rev war#fist fight#street brawl#boston#boston tea party#royal navy#british military

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE-RACE-RIVALS Announcement

What if there were object characters from many object shows, object characters based on characters from movies and anime, or ones that are custom made by me and the object community, began racing real world cars on places that are set in the track, city, countryside, and off-road? Well here's I concept that I'll be making, called THE-RACE-RIVALS.

Hello everybody. My name is RaymondYouTube1, and I will be making this new object show that involves driving real-world cars to race.

Remember, this is just a concept, but I will be bringing this concept to life. I'll be using Assetto Corsa, LibreOffice Impress, X-Plane 11, OpenShot Video Editor, Shotcut, Tortoise-TTS, and KdenLive. I'll also be using Decky Recorder to record Assetto Corsa and X-Plane 11 gameplay on my Steam Deck.

This object show involves object characters from many object shows, object characters based on characters from movies and anime, or ones that are custom made by me and the object community, racing real world cars on places that are set in the track, city, countryside, and off-road. Incorporating both historical and fictionalized aspects, other than the talking objects with limbs, this object show will borrow a lot of elements from reality and some of the events will be based on real life events. This object show will take place in an alternate timeline where objects are former actors of elimination shows that turned into race car drivers.

I'll be posting artwork of object character with their cars. And because this object show would be grounded in reality, just like ONE, the object characters will have human names, and the no arm/leg object characters would also have arms and legs. So, I'll be showing art of object characters based on fictional characters or real life people. I'll also be showing some design changes to some object characters. Now because I'll be using Tortoise-TTS, I'll have to make a disclosure that Tortoise-TTS is an AI voice cloner from GitHub and that I'm using AI generated voices.

Like I said, I'll be bringing this object show idea to life, but because of how humongous this task is, making this is time-consuming, and I can only work on it on my free time. So, yeah. I'll be updating this when I can. Thanks for reading and I'll see you next time.

Check out my subreddit on THE-RACE-RIVALS: https://www.reddit.com/r/TheRaceRivals/

#osc#object shows#object show community#gran turismo#initial d#mf ghost#wangan midnight#ford v ferrari#rush 2013#fast and furious#bfdi#battle for dream island#inanimate insanity#one cheesy hfj#object universe#the daily object show#object invasion#object overload#brawl of the objects#object lockdown#formula 1#monster jam#dakar rally#world rally championship#wrc#formula e#street racing#off road#car racing#bfdia

5 notes

·

View notes