#steven zaillian

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

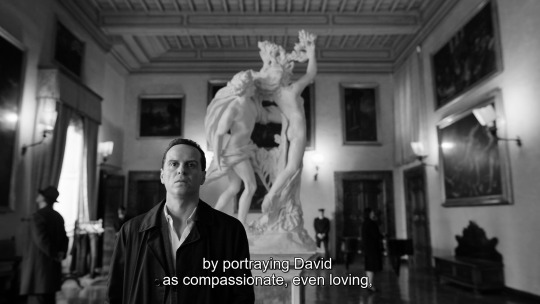

Ripley (Steven Zaillian, 2024).

321 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ripley (2024) dir. by Steven Zaillian

If there was any sensation he hated, it was that of being followed, by anybody. And lately he had it all the time. Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Mr. Ripley

#what an original idea to have art pieces spy on tom all the time#silent witnesses of ripley's wrongdoings#ripley#tom ripley#andrew scott#ripley netflix#steven zaillian#stunning cinematography#noir aesthetic#patricia highsmith#talented mr ripley#art imitates art#life imitates art#monuments#italy

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

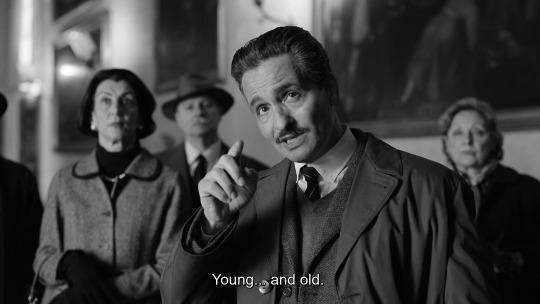

I wanted somebody older. I didn’t understand what the big deal would be that some guy’s son ran off to Europe at 25. That’s the story of every 25-year-old today. And so Tom Ripley would logically be the same age as Dickie Greenleaf [played by Johnny Flynn]. If he’s older, he’s more desperate. They’re both desperate. Ripley has been at this longer. He and Dickie have been around long enough to know that they’re failures.

Steven Zaillian on why he wanted an older Tom Ripley (x)

#Andrew Scott#johnny flynn#steven zaillian#the talented mr ripley#patricia highsmith#ripley netflix#ripley 2024#*nails this on the forehead of everyone still complaining about Andrew being too old*

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ripley Steven Zaillian. 2024

Hotel Excelsior Via del Corso, 126, 00186 Roma RM, Italy See in map

See in imdb

Bonus: also in this location

#steven zaillian#ripley#lion#statue#sculpture#stairs#hotel#rome#andrew scott#series#lazio#italy#cinema#film#location#google maps#street view#2024#patricia highsmith

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

We are lucky to be alive in the age of Andrew Scott, an actor of extraordinary breadth, skill and sensitivity, who can terrify as Jim Moriarty in Sherlock, make us fall in love (inappropriately) as the hot priest in Fleabag and cry in All of Us Strangers. He can also astonish, last year playing eight parts in a stage adaptation of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. He recently became the first actor to win the UK Critics’ Circle awards for best actor on stage and screen in the same year. And his latest project, Ripley, is a beautiful and chilling adaptation of the Patricia Highsmith novel The Talented Mr Ripley, with Scott playing the lead, dominating all eight one-hour episodes. It’s been a wild, crowning year for the 47-year-old Irish actor. But in March his mother, Nora, died of a sudden illness; she is who Scott has credited as being his foremost creative inspiration. His grief is fresh and intense and for the first half of the interview it seems to swim just beneath the surface of our conversation.

“We go through so many different types of emotional weather all the time,” he says. “And even on the saddest day of your life you might be hungry or have a laugh. Life just continues.” We are in a meeting room in his management company’s offices, talking about his ability, in his work, to modulate between emotions, to go from happy to sad, confused to scared, all within a matter of seconds. How does he do it? Scott laughs. “I would say that I have quite a scrutable face — is scrutable a word? — which is good or bad depending on what you are trying to achieve. But my job is to be as truthful as possible in the way that we are, and I don’t think that human beings are just one thing at any particular time. It is rare that we have one pure emotion.”

It’s an approach that is particularly appropriate for the playing of Tom Ripley, an acquisitive chameleon who inveigles his way into the lives of others (in this case Johnny Flynn, as the careless and wealthy Dickie Greenleaf, and his on-off girlfriend Marge, played by Dakota Fanning). “Ripley is witty, he is very talented. That’s gripping, to watch talent. I can’t call him evil — it is very easy to call people who do terrible things evil monsters, but they are not monsters, they are humans who do terrible things. Part of what she [Highsmith] is talking about is that if you dismiss a certain faction of society it has repercussions, and Ripley is someone who is completely unseen, he lives literally among the rats, and then there are these people who are gorgeous and not particularly talented and have the world at their feet but are not able to see the beauty that he can see.”

The show was written and directed by Steven Zaillian, the screenwriter of Schindler’s List. It’s set in Sixties New York and Italy, and filmed entirely in black-and-white, its chiaroscuro aesthetic evoking films of the Sixties — particularly those of Federico Fellini — while also offering an alternative to Anthony Minghella’s saturated late-Nineties iteration that starred Matt Damon and Jude Law. This has a darker flavour. “I found it challenging,” Scott says, “in the sense that he’s a solitary figure and ideologically we are very different. So you have to remove your judgment and try to find something that is vulnerable.”

It was a tough shoot, taking a year and filmed during lockdown. Scott was exhausted at the end of it and had intended to take a three-month break, but delays meant that he went straight from Ripley into All of Us Strangers. “Even though I was genuinely exhausted, it was energising because I was back in London, I was getting the Tube to work, there was sunshine,” he says. “I found it incredibly heartful, that film, there were so many different versions of love … I feel that all stories are love stories.”

All of Us Strangers, directed by Andrew Haigh, is about a screenwriter examining memories of his parents who died when he was 12. In it Scott’s character, Adam, returns to his family home, where his parents are still alive and as they were back in the Eighties. Adam is able to walk into the memory and to come out to his parents, finding the words that were unavailable to him as a boy. Some of it was filmed in Haigh’s childhood home, and there was a strong biographical element for him and his lead. Homosexuality was illegal in the Republic of Ireland until 1993, when Scott was 16. He did not come out to his parents until he was in his early twenties. I ask if he was working with his own childhood experiences in the film. “Of course, so in a sense it was painful, to a degree, but it was cathartic because you are doing it with people that you absolutely love and trust. I felt that it was going to be of use to people and I was right, it has been. The reaction to the movie has been genuinely extraordinary — it makes people feel and see things, and that isn’t an easy thing to achieve.”

The film is also a tender and erotic love story between Scott’s character and Harry, played by the Irish actor Paul Mescal. The two found a real-life kinship that made them a delight to watch on screen and off it, as a double act on the awards circuit. “I adore Paul, he’s so, so … continues to be …” Scott pauses. “Obviously it’s been a tough time recently and he just continues to be a wonderful friend. It’s everything. The more I work in the industry, I realise, you make some stuff that people love and you make some stuff that people don’t like, and all really that you are left with is the relationships that you make. I love him dearly.”

Scott and Mescal were also both notable on the red carpet for being extraordinarily well dressed. Scott loves fashion and has a big, well-organised wardrobe that he admits is in need of a cull. “I don’t like having too much stuff. I really believe that everything we have is borrowed — our stuff, our houses, we are borrowing it for a time. So I am trying to think of people who are the same size as me so I can give some of it away, and that’s a great thing to be able to do.” One of his favourite labels is Simone Rocha. “I love a bit of Simone Rocha. What a kind, glorious person she is. I just went to her show.” Fashion, he says, is in his DNA. “My mother was an art teacher, she was obsessed with all sorts of design. She loved jewellery and jewellery design. Anything that is visual, tactile, painting, drawing, is a big passion of mine, so I have tremendous respect for the creativity of designers.”

Today Scott is wearing Louis Vuitton trousers and a cropped Prada jacket, dressed up because he is collecting his Critics’ Circle award for best stage actor for Vanya. I ask how it feels to have won the double, a historic achievement. “Ah …” he says, looking at the table, going silent, having just been so voluble. “I’m sorry …” His voice cracks a little. “It’s bittersweet.”

At the ceremony Scott dedicated the award to his mother, saying of her “she was the source of practically every joyful thing in my life”. Is it difficult for him to carry on working in the circumstances, I wonder. “Well, you know, you have to — life goes on, you manage it day by day. It’s very recent, but I certainly can say that so much of it is surprising and unique, and there is so much that I will be able to speak about at some point.”

He is looking forward, he says, once promotion for Ripley is over, to taking some time off, going on holiday, going back to Ireland for a bit. He has homes in London and Dublin. To relax he walks his dog, a Boston terrier, dressed down in jeans and a hoodie “like a 12-year-old, skulking around the city” or goes to art galleries on the South Bank — he was considering a career as an artist until he was 17 and got a part in the Irish film Korea. He goes to the gym every day, “not, you know, to get …” he says, flexing his biceps. “More that it’s good for the head.” He is social, likes friends, likes a party. When I ask if he gave up drinking while doing Vanya, which required him to be on stage, alone, every night for almost two hours, he looks horrified. “Oh God, no! Easy tiger! Jesus … Although I didn’t drink much, I did have to look after myself. But we had a room downstairs in the theatre, a little buzzy bar, because otherwise I wouldn’t see anybody, so I was delighted to have people come down.”

Scott was formerly in a relationship with the screenwriter and playwright Stephen Beresford and is currently single, although this is not the sort of thing he likes to talk about. He is protective of his privacy, not wanting to reveal where he lives in London, or indeed the name of his dog — but he swerves such questions with a gentle good humour.

He is famous on set for being friendly and welcoming, for looking after other people. “The product is very important, but most of my time is spent in the process, so I want that to be as pleasant and kind as possible. I feel like it is possible to do that, that it is an honourable goal.” He is comfortable around people, with an easy charm — no one I have interviewed before has said my name so many times. And although when we talk he sometimes seems reflective or so very sad, there are also moments when he is exuberant, silly, putting on accents. “I feel like, as a person, I am quite near my emotions. I cry easily and I laugh easily, and there is nothing more pleasurable to me than laughing.”

Scott was raised a Catholic and is no longer practising, but says his view about religion is “ever changing — I definitely have a faith in things that cannot be proved”. When he was younger and felt overwhelmed, just before or after an audition, he would go to the Quaker Meeting House in central London and sit in silence, something that made its way into the second series of Fleabag, in which Scott’s priest takes Waller-Bridge’s character to that same meeting house. “It’s just around here,” he says, standing up, looking out of the window at Charing Cross Road. “When Phoebe and I first talked, we met at the Soho Theatre. We talked about love and religion, we walked all around here. And I said, ‘This is a place I go,’ so we called in and there was no one there, so we sat in there and we talked. It was a really magical day.”

Scott says he sees all the different characters that he has played as versions of himself. “It’s like, ‘What would this version of me look like?’ rather than, ‘Oh, I’m going to be somebody else.’ You filter it through you, and you discover more about yourself. I think that is a very lucky thing to be able to do, to find out more about yourself in the short time that we are here.”

#Andrew Scott#Ripley#Nora Scott#Critics Circle#Vanya#Chekhov#West End#All of Us Strangers#Paul Mescal#Hot Priest#Fleabag#Phoebe Waller-Bridge#Jim Moriarty#Sherlock#Patricia Highsmith#The Talented Mr Ripley#Dickie Greenleaf#Marge Sherwood#Dakota Fanning#Johnny Flynn#Steven Zaillian#Matt Damon#Jude Law#Anthony Minghella#Simone Rocha#Louis Vuitton#Andrew Haigh#Korea#Stephen Beresford

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Mission Impossible#Tom Cruise#Brian De Palma#Bruce Geller#David Koepp#Steven Zaillian#Robert Towne#VHS#90s

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

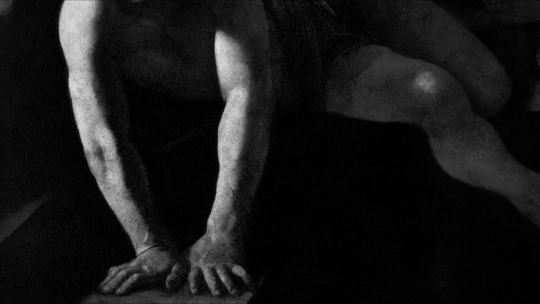

Ripley (2024) : Steven Zaillian

*Nota dell'editore: Le molte mani presenti nel nuovo adattamento di Ripley.

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Awakenings, 1990

#biography#drama#awakenings#penny marshall#oliver sacks#steven zaillian#robert de niro#robin williams#julie kavner

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ripley (2024)

#film#movie#ripley#netflix#Steven Zaillian#Patricia Highsmith#Andrew Scott#Dakota Fanning#Johnny Flynn

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

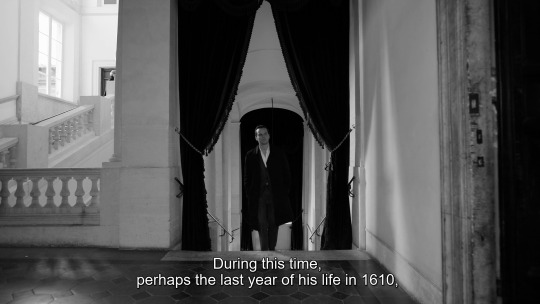

Ripley

Season 1, “III Sommerso”

Director: Steven Zaillian

DoP: Robert Elswit

#Ripley#Sommerso#III#Ripley S01E03#Season 1#Steven Zaillian#Robert Elswit#Andrew Scott#Tom Ripley#Johnny Flynn#Dickie Greenleaf#Patricia Highsmith#Netflix#Endemol Shine North America#Entertainment 360#Diogenes Entertainment#FILMRIGHTS#Showtime Studios#TV Moments#TV Series#TV Show#television#TV#TV Frames#cinematography#April 4#2024

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

#andrew scott#you look good in black and white#ripley#behind the scenes#steven zaillian#dakota fanning

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

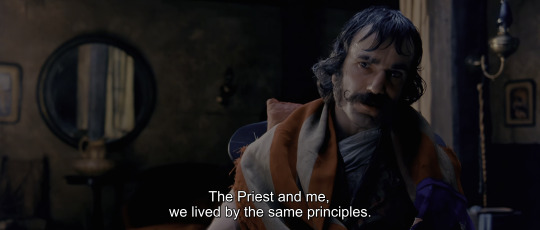

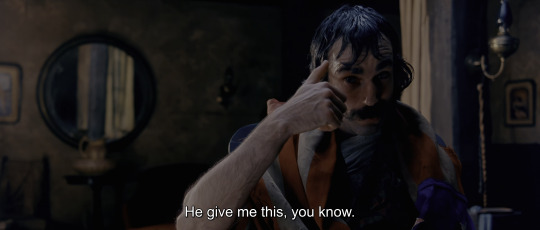

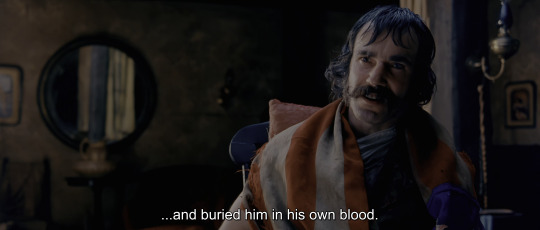

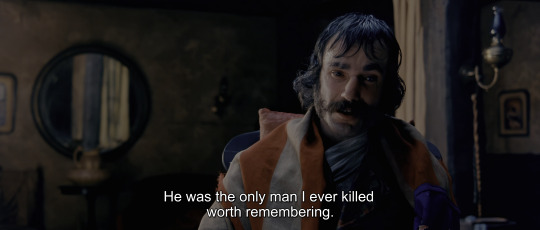

Gangs of New York (Martin Scorsese, 2002).

#gangs of new york#martin scorsese#daniel day lewis#leonardo dicaprio#jay cocks#steven zaillian#kenneth lonergan#michael ballhaus#Thelma Schoonmaker#dante ferretti#Sandy Powell

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

+ some stolen artworks and a couple dead bodies haunting your consciousness

#ripley#ripley netflix#tom ripley#andrew scott#steven zaillian#black and white#noir aesthetic#andrew is such a chameleon in this#costume department did really well

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andrew Scott en Ripley, Steven Zaillian, 2024.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

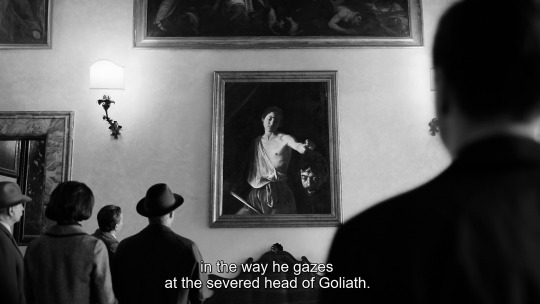

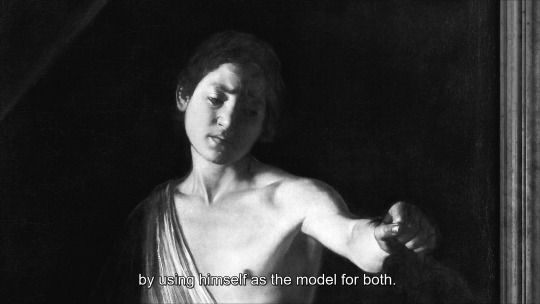

'Is Tom Ripley gay? For nearly 70 years, the answer has bedeviled readers of Patricia Highsmith’s 1955 thriller The Talented Mr. Ripley, the story of a diffident but ambitious young man who slides into and then brutally ends the life of a wealthy American expatriate, as well as the four sequels she produced fitfully over the following 36 years. It has challenged the directors — French, British, German, Italian, Canadian, American — who have tried to bring Ripley to the screen, including in the latest adaptation by Steven Zaillian, now on Netflix. And it appears even to have flummoxed Ripley’s creator, a lesbian with a complicated relationship to queer sexuality. In a 1988 interview, shortly before she undertook writing the final installment of the series, Ripley Under Water, Highsmith seemed determined to dismiss the possibility. “I don’t think Ripley is gay,” she said — “adamantly,” in the characterization of her interviewer. “He appreciates good looks in other men, that’s true. But he’s married in later books. I’m not saying he’s very strong in the sex department. But he makes it in bed with his wife.”

The question isn’t a minor one. Ripley’s killing of Dickie Greenleaf — the most complicated, and because it’s so murkily motivated, the most deeply rattling of the many murders the character eventually commits — has always felt intertwined with his sexuality. Does Tom kill Dickie because he wants to be Dickie, because he wants what Dickie has, because he loves Dickie, because he knows what Dickie thinks of him, or because he can’t bear the fact that Dickie doesn’t love him? Ordinarily, I’m not a big fan of completely ignoring authorial intent, and I’m inclined to let novelists have the last word on factual information about their own creations. But Highsmith, a cantankerous alcoholic misanthrope who was long past her best days when she made that statement, may have forgotten, or wanted to disown, her own initial portrait of Tom Ripley, which is — especially considering the time in which it was written — perfumed with unmistakable implication.

Consider the case that Highsmith puts forward in The Talented Mr. Ripley. Tom, a single man, lives a hand-to-mouth existence in New York with a male roommate who is, ahem, a window dresser. Before that, he lived with an older man with some money and a controlling streak, a sugar daddy he contemptuously describes as “an old maid”; Tom still has the key to his apartment. Most of his social circle — the names he tosses around when introducing himself to Dickie — are gay men. The aunt who raised him, he bitterly recalls, once said of him, “Sissy! He’s a sissy from the ground up. Just like his father!” Tom, who compulsively rehearses his public interactions and just as compulsively relives his public humiliations, recalls a particularly stinging moment when he was shamed by a friend for a practiced line he liked to use repeatedly at parties: “I can’t make up my mind whether I like men or women, so I’m thinking of giving them both up.” It has “always been good for a laugh, the way he delivered it,” he thinks, while admitting to himself that “there was a lot of truth in it.” Fortunately, Tom has another go-to party trick. Still nurturing vague fantasies of becoming an actor, he knows how to delight a small room with a set of monologues he’s contrived. All of his signature characters are, by the way, women.

This was an extremely specific set of ornamentations for a male character in 1955, a time when homosexuality was beginning to show up with some frequency in novels but almost always as a central problem, menace, or tragedy rather than an incidental characteristic. And it culminates in a gruesome scene that Zaillian’s Ripley replicates to the last detail in the second of its eight episodes: The moment when Dickie, the louche playboy whose luxe permanent-vacation life in the Italian coastal town of Atrani with his girlfriend, Marge, has been infiltrated by Tom, discovers Tom alone in his bedroom, imitating him while dressed in his clothes. It is, in both Highsmith’s and Zaillian’s tellings, as mortifying for Tom as being caught in drag, because essentially it is drag but drag without exaggeration or wit, drag that is simply suffused with a desire either to become or to possess the object of one’s envy and adoration. It repulses Dickie, who takes it as a sexual threat and warns Tom, “I’m not queer,” then adds, lashingly, “Marge thinks you are.” In the novel, Tom reacts by going pale. He hotly denies it but not before feeling faint. “Nobody had ever said it outright to him,” Highsmith writes, “not in this way.” Not a single gay reader in the mid-1950s would have failed to recognize this as the dread of being found out, quickly disguised as the indignity of being misunderstood.

And it seemed to frighten Highsmith herself. In the second novel, Ripley Under Ground, published 15 years later, she backed away from her conception of Tom, leaping several years forward and turning him into a soigné country gentleman living a placid, idyllic life in France with an oblivious wife. None of the sequels approach the cold, challenging terror of the first novel — a challenge that has been met in different ways, each appropriate to their era, by the three filmmakers who have taken on The Talented Mr. Ripley. Zaillian’s ice-cold, diamond-hard Ripley just happens to be the first to deliver a full and uncompromising depiction of one of the most unnerving characters in American crime fiction.

The first Ripley adaptation, René Clément’s French-language drama Purple Noon, is much beloved for its sun-saturated atmosphere of endless indolence and for the tone of alienated ennui that anticipated much of the decade to come; the movie was also a showcase for its Ripley, the preposterously sexy, maddeningly aloof Alain Delon. And therein lies the problem: A Ripley who is preposterously sexy is not a Ripley who has ever had to deal with soul-deep humiliation, and a Ripley who is maddeningly aloof is not going to be able to worm his way into anyone’s life. Purple Noon is not especially willing (or able — it was released in 1960) to explore Ripley’s possible homosexuality. Though the movie itself suggests that no man or woman could fail to find him alluring, what we get with Delon is, in a way, a less complex character type, a gorgeous and magnetic smooth criminal who, as if even France had to succumb to the hoariest dictates of the Hollywood Production Code, gets the punishment due to him by the closing credits. It’s delectable daylit noir, but nothing unsettling lingers.

Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr. Ripley, released in 1999, is far better; it couldn’t be more different from the current Ripley, but it’s a legitimate reading that proves that Highsmith’s novel is complex and elastic enough to accommodate wildly varying interpretations. A committed Matt Damon makes a startlingly fine Tom Ripley, ingratiating and appealing but always just slightly inept or needy or wrong; Jude Law — peak Jude Law — is such an effortless golden boy that he manages the necessary task of making Damon’s Tom seem a bit dim and dull; and acting-era Gwyneth Paltrow is a spirited and touchingly vulnerable Marge.

Minghella grapples with Tom’s sexual orientation in an intelligently progressive-circa-1999 way; he assumes that Highsmith would have made Tom overtly gay if the culture of 1955 had allowed it, and he runs all the way with the idea. He gives us a Tom Ripley who is clearly, if not in love with Dickie, wildly destabilized by his attraction to him. And in a giant departure from the novel, he elevates a character Highsmith had barely developed, Peter Smith-Kingsley (played by Jack Davenport) into a major one, a man with whom we’re given to understand that Ripley, with two murders behind him and now embarking on a comfortable and well-funded European life, has fallen in love. It doesn’t end well for either of them. A heartsick Tom eventually kills Peter, too, rather than risk discovery — it’s his third murder, one more than in the novel — and we’re meant to take this as the tragedy of his life: That, having come into the one identity that could have made him truly happy (gay man), he will always have to subsume it to the identity he chose in order to get there (murderer). This is nowhere that Highsmith ever would have gone — and that’s fine, since all of these movies are not transcriptions but interpretations. It’s as if Minghella, wandering around inside the palace of the novel, decided to open doors Highsmith had left closed to see what might be behind them. The result is the most touching and sympathetic of Ripleys — and, as a result, far from the most frightening.

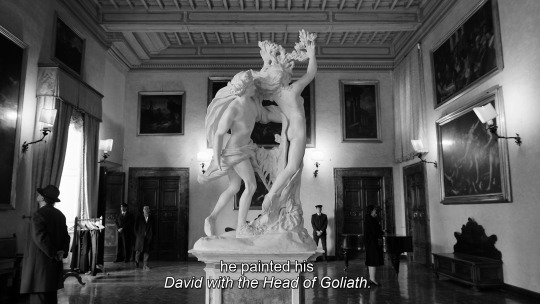

Zaillian is not especially interested in courting our sympathy. Working with the magnificent cinematographer Robert Elswit, who makes every black-and-white shot a stunning, tense, precise duel between light and shadow, he turns coastal Italy not into an azure utopia but into a daunting vertical maze, alternately paradise, purgatory, and inferno, in which Tom Ripley is forever struggling; no matter where he turns, he always seems to be at the bottom of yet another flight of stairs.

It’s part of the genius of this Ripley — and a measure of how deeply Zaillian has absorbed the book — that the biggest departures he makes from Highsmith somehow manage to bring his work closer to her scariest implications. There are a number of minor changes, but I want to talk about the big ones, the most striking of which is the aging of both Tom and Dickie. In the novel, they’re both clearly in their 20s — Tom is a young striver patching together an existence as a minor scam artist who steals mail and impersonates a collection agent, bilking guileless suckers out of just enough odd sums for him to get by, and Dickie is a rich man’s son whose father worries that he has extended his post-college jaunt to Europe well past its sowing-wild-oats expiration date. Those plot points all remain in place in the miniseries, but Andrew Scott, who plays Ripley, is 47, and Johnny Flynn, who plays Dickie, is 41; onscreen, they register, respectively, as about 40 and 35.

This changes everything we think we know about the characters from the first moments of episode one. As we watch Ripley in New York, dourly plying his miserable, penny-ante con from a tiny, barren shoe-box apartment that barely has room for a bed as wide as a prison cot (this is not a place to which Ripley has ever brought guests), we learn a lot: This Ripley is not a struggler but a loser. He’s been at this a very long time, and this is as far as he’s gotten. We can see, in an early scene set in a bank, that he’s wearily familiar with almost getting caught. If he ever had dreams, he probably buried them years earlier. And Dickie, as a golden boy, is pretty tarnished himself — he isn’t a wild young man but an already-past-his-prime disappointment, a dilettante living off of Daddy’s money while dabbling in painting (he’s not good at it) and stringing along a girlfriend who’s stuck on him but probably, in her heart, knows he isn’t likely to amount to much.

Making Tom older also allows Zaillian to mount a persuasive argument about his sexuality that hews closely to Highsmith’s vision (if not to her subsequent denial). If the Ripley of 1999 was gay, the Ripley of 2024 is something else: queer, in both the newest and the oldest senses of the word. Scott’s impeccable performance finds a thousand shades of moon-faced blankness in Ripley’s sociopathy, and Elswit’s endlessly inventive lighting of his minimal expressions, his small, ambivalent mouth and high, smooth forehead, often makes him look slightly uncanny, like a Daniel Clowes or Charles Burns drawing. Scott’s Ripley is a man who has to practice every vocal intonation, every smile or quizzical look, every interaction. If he ever had any sexual desire, he seems to have doused it long ago. “Is he queer? I don’t know,” Marge writes in a letter to Dickie (actually to Tom, now impersonating his murder victim). “I don’t think he’s normal enough to have any kind of sex life.” This, too, is from the novel, almost word for word, and Zaillian uses it as a north star. The Ripley he and Scott give us is indeed queer — he’s off, amiss, not quite right, and Marge knows it. (In the novel, she adds, “All right, he may not be queer [meaning gay]. He’s just a nothing, which is worse.”) Ripley’s possible asexuality — or more accurately, his revulsion at any kind of expressed sexuality — makes his killing of Dickie even more horrific because it robs us of lust as a possible explanation. This is the first adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley I’ve seen in which even Ripley may not know why he murders Dickie.

When I heard that Zaillian (who both wrote and directed all of the episodes) was working on a Ripley adaptation, I wondered if he might replace sexual identity, the great unequalizer of 1999, with economic inequity, a more of-the-moment choice. Minghella’s version played with the idea; every person and object and room and vista Damon’s Ripley encountered was so lush and beautiful and gleaming that it became, in some scenes, the story of a man driven mad by having his nose pressed up against the glass that separated him from a world of privilege (and from the people in that world who were openly contemptuous of his gaucheries). Zaillian doesn’t do that — a lucky thing, since the heavily Ripley-influenced film Saltburn played with those very tropes recently and effectively. Whether intentional or not, one side effect of his decision to shoot Ripley in black and white is that it slightly tamps down any temptation to turn Italy into an occasion for wealth porn and in turn to make Tom an eat-the-rich surrogate. This Italy looks gorgeous in its own way, but it’s also a world in which even the most beautiful treasures appear threatened by encroaching dampness or decay or rot. Zaillian gives us a Ripley who wants Dickie’s life of money and nice things and art (though what he’s thinking when he stares at all those Caravaggios is anybody’s guess). But he resists the temptation to make Dickie and Marge disdainful about Tom’s poverty, or mean to the servants, or anything that might make his killing more palatable. This Tom is not a class warrior any more than he’s a victim of the closet or anything else that would make him more explicable in contemporary terms. He’s his own thing — a universe of one.

Anyway, sexuality gives any Ripley adapter more to toy with than money does, and the way Zaillian uses it also plays effectively into another of his intuitive leaps — his decision to present Dickie’s friend and Tom’s instant nemesis Freddie Miles not as an obnoxious loudmouth pest (in Minghella’s movie, he was played superbly by a loutish Philip Seymour Hoffman) but as a frosty, sexually ambiguous, gender-fluid-before-it-was-a-term threat to Tom’s stability, excellently portrayed by Eliot Sumner (Sting’s kid), a nonbinary actor who brings perceptive to-the-manor-born disdain to Freddie’s interactions with Tom. They loathe each other on sight: Freddie instantly clocks Tom as a pathetic poser and possible closet case, and Tom, seeing in Freddie a man who seems to wear androgyny with entitlement and no self-consciousness, registers him as a danger, someone who can see too much, too clearly. This leads, of course, to murder and to a grisly flourish in the scene in which Tom, attempting to get rid of Freddie’s body, walks his upright corpse, his bloodied head hidden under a hat, along a street at night, pretending he’s holding up a drunken friend. When someone approaches, Tom, needing to make his possible alibi work, turns away, slamming his own body into Freddie’s up against a wall and kissing him passionately on the lips. That’s not in Highsmith’s novel, but I imagine it would have gotten at least a dry smile out of her; in Ripley’s eight hours, this necrophiliac interlude is Tom’s sole sexual interaction.

No adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley would work without a couple of macabre jokes like that, and Zaillian serves up some zesty ones, including an appearance by John Malkovich, the reigning king/queen of sexual ambiguity (and himself a past Ripley, in 2002’s Ripley’s Game), nodding to Tom’s future by playing a character who doesn’t show up until book two. He also gives us a witty final twist that suggests that Ripley may not even make it to that sequel, one that reminds us how fragile and easily upended his whole scheme has been. Because Ripley, in this conception, is no mastermind; Zaillian’s most daring and thoughtful move may have been the excision of the word “talented” from the title. In the course of the show, we see him toy with being an editor, a writer (all those letters!), a painter, an art appreciator, and a wealthy man, often convincingly — but always as an impersonation. He gives us a Tom who is fiercely determined but so drained of human affect when he’s not being watched that we come to realize that his only real skill is a knack for concentrating on one thing to the exclusion of everything else. What we watch him get away with may be the first thing in his life he’s really good at (and the last moment of the show suggests that really good may not be good enough). This is not a Tom with a brilliant plan but a Tom who just barely gets away with it, a Tom who can never relax.

Tom’s sexuality is ultimately an enigma that Zaillian chooses to leave unsolved — as it remains at the end of the novel. Highsmith’s decision to turn Tom into a roguish heterosexual with a taste for art fraud before the start of the second novel has never felt entirely persuasive, and it’s clearly a resolution in which Zaillian couldn’t be less interested. Toward the end of Ripley, Tom is asked by a detective to describe the kind of man Dickie was. He transforms Dickie’s suspicion about his queerness into a new narrative, telling the private investigator that Dickie was in love with him: “I told him I found him pathetic and that I wanted nothing more to do with him.” But it’s the crushing verdict he delivers just before that line that will stay with me, a moment in which Tom, almost in a reverie, might well be describing himself: “Everything about him was an act. He knew he was supremely untalented.” In the end, Scott and Zaillian give us a Ripley for an era in which evil is so often meted out by human automatons with even tempers and bland self-justification: He is methodical, ordinary, mild, and terrifying.'

#Andrew Scott#Ripley#Matt Damon#The Talented Mr Ripley#Anthony Minghella#Steven Zaillian#Purple Noon#Alain Delon#Johnny Flynn#Dickie Greenleaf#Peter Smith-Kingsley#Jude Law#Gwyneth Paltrow#Robert Elswit#Caravaggio#Marge Sherwood#Freddie Miles#Philip Seymour Hoffman#Eliot Sumner

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

RIPLEY (2024) S01E01 - I A HARD MAN TO FIND

12 notes

·

View notes