#spartan lll

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Okay, so I finish Halo: last light and omg its so good?? Like wtf, why was it so good?? Anyways Fred gets all the kisses, and for whatever reason Kelly just had me kicking my feet, like omg that girl said a few lines and I'm texting my friend like "ugh Kelly man, she had me gwaning at the bars of my enclosure."

I want more Linda and Kelly interactions so bad, like come on. Also, I loved the way Veta was written and all the Spartan lll, I love all of them and they must be protected at all cost.

Moral of my story, such a good book and I'm a little wine drunk

Also working on a Linda-058 X reader right now, because why not? And wtf give me a book about Linda please!

#Kadia chatter#halo#Halo last light#last light#so like seriously#wtf am I such a simp for kelly lately#like fuck#and Fred#I just want to give this man a kiss on his faceplate and tell him he's doing great#but that man is doing his best#and i will hear nothing else#thanks for coming to my ted talk#spartan ll#spartan lll#halo series

0 notes

Text

Noble 6 a Spartan -lll that was the newsiest member of the noble team before the fall of reach. Was thought dead before being found and rescued on November 18, 2552. Signs of tortured and such was found on them. They were in a coma for the rest the human-covenant war. On February 14, 2554 they woken up from there coma and wanted to return to active duty has soon they could. But due to injures from the fall of reach and from the torture they were taken off from the front lines. They were send to the station were they train the spartan - IV. Some higher ups jokingly said that they were hoping that hyper-lethal vector mojo rubs off on the new Spartans.

During there stay they didn't have much to do beside training new Spartans and paperwork. Due to the injured made them unfit for any psychical duties. So they turn to snacking to help starve off the boredom.

Which gave some hefty results.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I-

This.

Finishing Fall of Reach, this is what I think about most, cause we got her POV, we know she’s remorseful for what she had to do, but it had to be done. If she didn’t do it, someone else was gonna be given the program and they would have been worse. Like Ackerson, he doesn’t care for the Spartan lll, he only cares that he succeeded, at least Halsey cared for the lls.

I have so many thoughts and feelings about Halsey. Like she cries when she finds out about Miranda’s fate and cries about it often. She knows she wasn’t a good mother but she loved her daughter.

Catherine Halsey believed that she had to live with becoming the monster to save everyone, and proceeded to have to live with the people she loved the most being the ones she could not save.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emile-A239 from Noble Team.

Halo: Reach concept art, 2010.

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: I really enjoyed your book review of Sebastian Junger’s Homecoming. Perhaps enjoyment isn’t the right word because it brought home some hard truths. Your book review really helped me understand my older brother better when I think back on how he came home from the war in Afghanistan after serving with the Paras and had medals pinned up the yin yang. It was hard on everyone in the family, especially for him and his wife and young kids. He has found it hard going. Thanks for sharing your own thoughts as a combat veteran from that war. Even if you’re a toff you don’t come across as a typical Oxbridge poncey Rupert! As you’re a classicist and historian how did ancient soldiers deal with PTSD? Did the Greeks and Roman soldiers even suffer from it like our fighting boys and girls do? Is PTSD just a modern thing?

Part 1 of 2 (see following post)

Because this is subject very close to my heart as a combat veteran I thought very long and hard about the issues you raised. I decided to answer this question in two posts.

This is Part 1 and Part 2 is the next post.

My apologies for the length but this is subject that deserves full careful consideration.

Thank you for your lovely words and I especially find its heart warming if they touched you. I appreciate you for sharing something of the experience your ex-Para brother went through in coming home from war. I have every respect for the Parachute regiment as one of the world’s premier fighting force.

Working alongside them on missions out in Afghanistan I could see their reputation as the ‘brain shit’ of the British Army was well deserved. They’re most uncouth, sweary, and smelliest group of yobbos I’ve ever had the awful misfortune to meet. I’m kidding. The mutual respect and the ribbing went hand in hand. I doff my smurf hat to the cherry berries as ‘propah soldiers’ as they liked to say especially when they cast a glance over at the other elite regiments like HCav and the guards regiments.

Don’t worry I’ve been called a lot worse! But I am grateful you don’t lump me with the other ‘poncey’ officers. Not sure what a female Rupert is called. The fact that I was never accused of being one by any of those I served with is perhaps something I take some measure of pride. There are not as many real toff officers these days compared to the past but there are a fair few Ruperts who are clueless in leading men under their charge. I knew one or two and frankly I’m embarrassed for them and the men under their charge.

I don’t know when the term PTSD was first used in any official way. My older sister who is a doctor - specialising in neurology and all round brain box and is currently working on the front lines in the NHS wards fighting Covid alongside all our amazing NHS nurses and doctors - took time out one evening to have a discussion with me about these issues. I also talked to one or two other friends in the psychiatric field too. In consensus they agree it was around 1980 when the term PTSD came into usage. Specifically it was the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-lll) published by the American Psychiatric Association in 1980 partly because as a result of the ongoing treatment of veterans from the Vietnam War. In the modern mind, PTSD is more associated with the legacy of the Vietnam War disaster.

The importance of whether PTSD affected the ancient Greeks and Romans lies in the larger historical question of to what extent we can apply modern experience to unlock or interpret the past. In the period since PTSD was officially recognised, scholars and psychologists have noted its symptoms in descriptions of the veterans of past conflicts. It has become increasingly common in books and novels as well as articles to assume the direct relevance of present-day psychology to the reactions of those who experienced violent events in the historical past. In popular culture, especially television and film dramas, claims for the historical pedigree of PTSD are now often provided as background to the modern story, without attribution. Indeed we just take it as a given that soldier-warriors in the past suffered the same and in the same way as their modern day counterparts. We are used to the West to map the classical world upon the present but whether we can so easily map the modern world back upon the Greeks and Romans is a doubtful proposition when it comes to discussing PTSD.

Simply put, there is no definitive evidence for the existence of PTSD in the ancient world existed, and relies instead upon the assumption that either the Greeks or Romans, because they were exposed to combat so often, must have suffered psychological trauma.

There are two schools of thought regarding the possibility of PTSD featuring in the Greco-Roman world (and indeed the wider ancient world stretching back into pre-history, myth and legend) – universalism and relativism. Put simply, the universalists argue that we all carry the same ‘wetware’ in our heads, since the human brain probably hasn’t developed in evolutionary terms in the eye blink that is the two thousand years or so since the Greco-Roman Classical era. If we’re subject to PTSD now, they posit, then the Greeks and the Romans must have been equally vulnerable. The relativists, on the other hand, argue that the circumstances under which the individual has received their life conditioning – the experiences which programme the highly individual software running that identical ‘wetware’, if you will – is of critical importance to an individual’s capacity to absorb the undoubted horrors of any battlefield, ancient or modern.

Whichever school one falls down on the side of is that what seems to happen in any serious discussion of the issue of PTSD in the ancient world is to either infer it indirectly from culture (primarily, literature and poetry) or infer it from a comparative historical understanding of ancient warfare. Because the direct evidence is so scant we can only ever infer or deduce but can never be certain. So we can read into it whenever we wish.

In Greek antiquity we have of course The Illiad and the Odyssey as one of the most cited examples when we look at the character traits of both Achilles and Odysseus. From Greek tragedy those who think PTSD can be inferred often point to Sophocles’s Ajax and Euripide’s Heracles. Or they look to Aeschylus and The Oresteia. I personally think this is an over stretch. Greek writers do; the return from war was a revisited theme in tragedy and is the subject of the Odyssey and the Cyclic Nostoi.

The Greeks didn’t leave us much to ponder further. But, with rare exceptions, the works from Graeco-Roman antiquity do not discuss the mental state of those who had fought. There is silence about the interior world of the fighting man at war’s end. So we are led to ponder the question why the silence?

This silence also echoes into the Roman period of literature and history too. Indeed when we turn to the Roman world, descriptions of veterans are rare in the writings that survive from the Roman world and occur most often in fiction.

In the first poem of Ovid’s Heroides, the poet writes about a returned soldier tracing a map upon a table (Ov. Her. 1.31–5):

...upon the tabletop that has been set someone shows the fierce battles, and paints all Troy with a slender line of pure wine:

‘Here the Simois flowed; this is the Sigeian territory,

here stood the lofty palace of old Priam, there the tent of Achilles...’

This scene provides an intimate glimpse of what it must have been like when a veteran returned home and told stories of his campaigns: the memories of battle brought to the meal, the crimson trail of the wine offering a rough outline of the places and battlefields he had experienced. The military characters in poems and plays show a world in which soldiers are ubiquitous, if somewhat annoying to the civilians. Plautus, for instance, in his Miles Gloriosus, portrays an officer boasting about his made-up conquests – the model for the braggart in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum – and Juvenal complains about a centurion who stomps on his sandalled foot in the bustling Roman street.

Despite this silence, compelling works have been written that interweave vivid modern accounts of combat and its aftermath with quotes from ancient prose and poetry. At their best, these comparisons can illuminate both worlds, but at other times the concerns of the present-day author are imposed on the ancient material. But the question remains are such approaches truthful and valid in understanding PTSD in the ancient world?

So if arts and literature don’t really tell us much what about comparative examples drawn from military history itself?

Here again we are in left disappointed.

According to the Greek historian, Herodotus, in 480 B.C., at the Battle of Thermopylae, where King Leonidas and 300 Spartans took on Xerxes I and 100,000-150,000 Persian troops, two of the Spartan soldiers, Aristodemos and another named Eurytos, reported that they were suffering from an “acute inflammation of the eyes,”...Labeled tresantes, meaning “trembler,”. It is that Aristodemos later hung himself in shame. Another Spartan commander was forced to dismiss several of his troops in the Battle of Thermopylae Pass in 480 B.C, “They had no heart for the fight and were unwilling to take their share of the danger.”

Herodotus again in writing about the battle of Marathon in 490 B.C., cites an Athenian warrior who went permanently blind when the soldier standing next to him was killed, although the blinded soldier “was wounded in no part of his body.” Interestingly enough, blindness, deafness, and paralysis, among other conditions, are common forms of “conversion reactions” experienced and well-documented among soldiers today

Outside the fictional world, Roman military history tell us very little.

Appian of Alexandria (c. 95? – c. AD 165) described a legion veteran called Cestius Macedonicus who, when his town was under threat of capture by (the Emperor-to-be) Octavian, set fire to his house and burned himself within it. Plutarch’s Life of Marius speaks of Caius Marius’ behaviour who, when he found himself under severe stress towards the end of his life, suffering from night terrors, harassing dreams, excessive drinking and flashbacks to previous battles. These examples are just a few instances which seem to demonstrate that PTSD, or culturally similar phenomena, may be as old as warfare itself. But it’s worth stressing it is not definitive, just conjecture.

Of course of accounts of wars and battles were copiously written but not the hard bloody experience of the soldier. Indeed the Roman military man is described almost exclusively as a commander or in battle. Men such as Caesar who experienced war and wrote about it do not to tell us about homecoming.

It seems one of main challenges when we try to see military history through the lens of our definition of PTSD is to first understand the comparative nature of military history and what it is we are comparing ie mistaking apples for oranges.

The origin of military history was tied to the idea that if one understood ancient battle, one might fight and, more importantly, one might lead and strategise more effectively. In essence, much of the training of officers – even in the military handbooks of the Greeks and Romans – was an attempt to keep new commanders from making the same mistakes as the commanders of old. Military history is intended to be a pragmatic enterprise; in pursuit of this pragmatic goal, it has long been the norm to use comparative materials to understand the nature of ancient battle.

The 19th Century French military theorist Ardant du Picq argued for the continuity of human behaviour and assumed that the reactions of men under the threat of lethal force would be identical over the centuries: “Man does not enter battle to fight, but for victory. He does everything that he can to avoid the first and obtain the second....Now, man has a horror of death. In the bravest, a great sense of duty, which they alone are capable of understanding and living up to, is paramount. But the mass always cowers at sight of the phantom, death. Discipline is for the purpose of dominating that horror by a still greater horror, that of punishment or disgrace. But there always comes an instant when natural horror gets an upper hand over discipline, and the fighter flees”

These words offer insight to those of us who have never faced the terror of battle but at the same time assume the universality of how combat is experienced, despite changes in psychological expectations and weaponry, to name but two variables.

Another incentive for scholars and researchers is to turn to comparative material has been the growing awareness of the artificiality of how we describe war. A mere phrase such as ‘flank attack’ does not capture the bloody, grinding human struggle. Roman authors – especially those who had not fought – often wrote generic descriptions of battle. Literary battle can distort and simplify even as it tells, but if the main things are right – who won, who lost, and who the good guys are – the important ‘facts’ are covered. Even if one intends to speak the truth about battle, the assumptions and the normative language used to describe violence will affect the telling. We may note that the battle accounts in poetry become increasingly grisly during the course of the Roman Empire (perhaps owing to the growing popularity of gladiatorial games),while, in Caesar’s Gallic War, the Latin word cruor (blood) never appears and sanguis (another Latin word for blood) only appears in quoted appeals (Caes. B. Gall. 7.20, in the mouth of Vercingetorix, and 7.50, where the centurion M. Petronius urges his men to retreat). The realities of the battlefield are described in anodyne shorthand. In much the same way that the news rarely prints or televises graphic images, Caesar does not use gore, and perhaps for the same reason – to give a sense of reportorial objectivity.

Another element in the interpretive scrum is a given author’s goal in writing an account in the first place: Caesar, for example, was writing about himself, and he may have been producing something akin to a political campaign ad. Caesar makes Caesar look great and there is reason to believe that, if he was not precisely cooking the books, he did give them a little rinse to make him look more pristine. Given the many factors that complicate our ability to ‘unpack’ battle narratives, Philip Sabin has argued that the ambiguity and unreliability of the ancient sources must be supplemented by looking at the “form of the overall characteristics of Roman infantry in mortal combat”. Again the modern is used to illuminate that which is obscured by written accounts and the “the enduring psychological strains” are merely unconsciously assumed.

These legitimate uses of comparative materials have led to a sort of creep: because military historians have used observations of how men react to combat stress during battle to indicate continuity of behaviour through time, there appears to be a consequent expectation that men will also react identically after battle. This creep became a lusty stride with modern books written about the ancient world and PTSD.

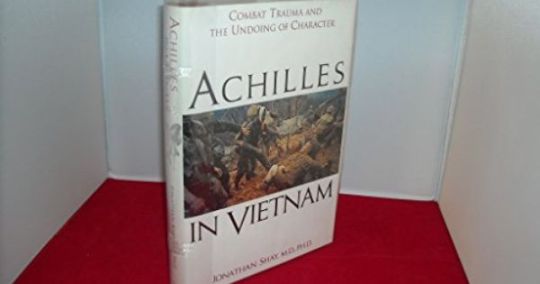

After I finished my tour in Afghanistan I read many books recommended to me by family and friends as well as comrades. One of these books is well known in military circles - at least amongst the thinking officer class - as an iconic work of marrying the ancient world and the modern experience of war. I read it and I was touched deeply by this brilliant therapeutic book. It was only months later I began to re-think whether it was a true account of PTSD in the ancient world.

This insightful book is called Achilles in Vietnam by Jonathan Shay. Shay is psychiatrist in Boston, USA. He began reading The Iliad with Vietnam veterans whom he was treating. Achilles in Vietnam, is a deeply humane work and is very much concerned with promoting policies that he hoped would help diminish the frequency of post-traumatic stress. His goal was not to explain ancient poetry but to use it therapeutically by linking his patients’ pain to that of the Iliad’s great hero. His book offers a conduit between the reader and the experiences of the men that Shay counsels. In the introduction to this work he makes a nod to Homerists while also asserting the primacy of his own reading:

“I shall present the Iliad as the tragedy of Achilles. I will not glorify Vietnam combat veterans by linking them to a prestigious ‘classic’ nor attempt to justify study of the Iliad by making it sexy, exciting, modern or ‘relevant’. I respect the work of classical scholars and could not have done my work without them. Homer’s poem does not mean whatever I want it to mean. However, having honored the boundaries of meaning that scholars have pointed out, I can confidently tell you that my reading of the Iliad as an account of men in war is not a ‘meditation’ that is only tenuously rooted in the text. “

After outlining the major plot points around which he will organise his argument, he notes, “ ‘This is the story of Achilles in the Iliad, not some metaphorical translation of it”.

The trouble was and continues to be is that many in the historical and medical fields began to rush to unfounded conclusions that Shay, on the issue of PTSD in the ancient world, had demonstrated that the psychological realities of western warfare were universal and enduring. More books on similar comparative themes soon emerged and began to enshrine the truth that PTSD was indeed prevalent throughout the ancient world and one could draw comparative lessons from it.

Perhaps one of the most influential books after Shay was by Lawrence Tritle. Tritle, a veteran himself, wrote From Melos to My Lai. It’s a fascinating book to read and there are parts that certainly resonate with my own experiences and those of others I have known. In the book Tritle drew a direct parallel between the experiences of the ancient Greeks and those of modern veterans. For instance, Xenophon, in his military autobiography, presents a brief eulogy for one of his fallen commanders, Clearchus. Xenophon writes that Clearchus was ‘polemikos kai philopolemos eschatos’ (Xen. An. 2.6) – ‘warlike and a lover of war to the highest degree’.

Tritle comments:

“The question that arises is why men like Clearchus and his counterparts in Vietnam and the Western Front became so entranced with violence. The answer is to be found in the natural ‘high’ that violence induces in those exposed to it, and in the PTSD that follows this exposure. Such a modern interpretation in Clearchus’ case might seem forced, but there seems little reason to doubt that Xenophon in fact provides us with the first known historical case of PTSD in the western literary tradition.”

Arguably in the West and especially our current modern Western culture is predicated at baulking at the notion of being ‘war lovers” as immoral. But such an interpretation speaks more of our modern Christianised ambivalence towards war; to the Spartans and Athenians the term would not have had a negative connotation. ‘Philopolemos’ is, in fact, a compliment, and the list of Clearchus’ military exploits functions as a eulogy. There are points where his analysis does not adequately address the divergences between ancient and modern experiences.

For all the talk of our Western culture being rooted in Ancient Greece and Rome we are not shaped by the same ethics. Our modern ethics and our moral code is Christian. There is no such thing as a secular humanist or atheist both owe a debt to Christianity for the way they have come to be; in many respects it’s more accurate to describe such people as Christianised Humanists or Christian Atheists even if they reject the theological tenets of the religious faith because they use Christian morality as the foundation to construct their own. Many forget just how brutal these ancient societies were in every day life to the point there would be little one could find recognisable within our own modern lives.

Now we come to third point I wish to make in determining where the Greeks or Romans actually experienced PTSD. This is to do with the little understood nature of PTSD itself. As much as we know about PTSD there is still much more we don’t know. Indeed one of the most problematic and complicated issues is the continued disagreement around the diagnosis and specific triggers of the disorder which remain little understood. We have to admit there are competing theories about what causes PTSD but, in terms of experiences that make it manifest, there are essentially three possible triggers: witnessing horrific events and/or being in mortal danger and/or the act of killing – especially close kills where the reality of one’s responsibility cannot be doubted. The last of these was strongly argued in another scholarly book by D. Grossman, On Killing, the Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society (1995).

Roman soldiers had the potential to experience all of these things. The majority of Roman combat was close combat and permitted no doubt as to the killer. The comparatively short length of the gladius encouraged aggressive fighting. Caesar recounts how his men, facing a shield wall carried by the taller Gauls, leaped up on top of the shields, grabbed the upper edges with one hand, and stabbed downwards into the faces of their opponents (Caes. B. Gall. 1.52). As for mortal danger, Stefan Chrissanthos in his informative book, Warfare in the Ancient World: From the Rise of Uruk to the Fall of Rome, 3500BC-476AD, puts it this way: “For Roman soldiers, though the weapons were more primitive, the terrors and risks of combat were just as real. They had to face javelins, stones, spears, arrows, swords, cavalry charges, and maybe worst of all, the threat of being trampled by war elephants.”

Such terrors are regularly attested. During his campaign in North Africa, Caesar, noting his men’s fear, procured a number of elephants to familiarise his troops with how best to kill the beasts (Caes. B. Afr.72). It should also be noted that it was not unusual for the reserve line to be made up of veterans because they were better able to watch the combat without losing their nerve. Held in reserve, they had to watch stoically as their comrades were injured and killed, and contemplate the awful fact that they might suffer the same fate. This was not a role for the faint of heart.

However, while the Romans certainly had the raw ingredients for combat trauma, the danger for a Roman legionary was much more localised. Mortars could not be lobbed into the Green Zone, suicide bombers did not walk into the market, and garbage piled on the street did not hide powerful explosives. The danger for a Roman soldier was largely circumscribed by his moments on the field of battle, and even here, if he was with the victorious side, the casualties were likely to be light: at Gergovia, a disaster by Caesar’s standards, he lost nearly seven hundred men (Caes. B. Gall. 7.51). In his victory over Pompey the Great at Pharsalus, his casualties numbered only two hundred (Caes. B. Civ. 3.99).

So we are left with the disturbing question: were the stressors really the same?

This is the part where I also defer to my eldest sister as a doctor and surgeon specialising in neurology and just so much smarter than myself.

My eldest sister holds the view in talking to her own American medical peers that despite similar experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq, British soldiers on average report better mental health than US soldiers.

My sister pointed out to research study done by Kings College London way back around 2015 or so that analysed 34 studies produced over a 15-year period (up to 2015) and found that overall there has been no increase in mental health issues among British personnel - with the exception of high rates of alcohol abuse among soldiers. The study was in part inspired the “significant mental health morbidity” among U.S. soldiers and reports that factors such as age and the quality of mental health programs contribute to the difference between the two nation’s servicemen and women.

She pointed out that these same studies showed that post-traumatic stress disorder afflicts roughly 2 to 5% of non-combat U.K. soldiers returning from deployment, while 7% of combat troops report PTSD. According to a General Health Questionnaire, an estimated 16 to 20% of U.K. soldiers have reported symptoms of common mental disorders, similar to the rates of the general U.K. population. In comparison, studies around the same time in 2014 showed U.S. soldiers experience PTSD at rates of 21 to 29%. The U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs estimated PTSD afflicted 11% of veterans returning from Afghanistan and 20% returning from Iraq. Major depression was reported by 14% of major soldiers according to another study commissioned by RAND corporation; roughly 7% of the general U.S. population reports similar symptoms.

It’s always tough comparing rates between countries and is not a reflection of the quality of the fighting soldier. But one finding that consistently and stubbornly refuses to go away is that over the past 20 years reported mental health problems tend to be higher among service personnel and veterans of the USA compared with the UK, Canada, Germany and Denmark.

However my sister strongly cautioned against making hasty judgements. And there could be many variable factors at play. One explanation is that American soldiers are more likely than their British counterparts to be from the reserve forces. Empirical studies showed reservists from both America and British troops were more likely to experience mental illness post-deployment. It was also worth pointing out that American soldiers also tended to be younger - being younger and inexperienced as well as untested on the battlefield, service personnel would naturally run the risk of greater and be more vulnerable to mental illness.

In contrast, the elite forces of the British army, such as your brother’s Parachute Regiment or the Royal Marines, were found to be the least affected by mental illness. It was found that in spite of elite forces experiencing some of the toughest fighting conditions, they tended to enjoy better mental health than non-elite troops. The more elite a unit is or more professional then you find that troops tend to enjoy a very deep bonds of camaraderie. As such the social cohesion of these fighting forces provides a psychological protective buffer. Not for all, but for many.

More intriguing are new avenues of discovery that might go a long way to actually understanding one of the root causes of PTSD. According to my sister, recent research carried out in the US and Europe and published in such prestigious medical journals as the New England Journal of Medicine (US) and the Lancet (UK), seems to establish a causal link between concussive injury and PTSD.

One recent study looked at US soldiers that concerned itself with the effects of concussive injuries upon troops after their return from active duty during the war in Iraq.

Of the majority of soldiers who suffered no combat injuries of any sort, 9.1 per cent exhibited symptoms consistent with PTSD. This allows a baseline for susceptibility of roughly 10% of the population. A slightly higher number (16.2%) of those who were injured in some way, but suffered no concussion, also experienced symptoms. As soon as concussive injuries were involved, however, the rates of PTSD climbed dramatically.

Although only 4.9% of the troops suffered concussions that resulted in complete loss of consciousness, 43.9% of these soldiers noted on their questionnaires that they were experiencing a range of PTSD symptoms. Of the 10.3% of the unit who suffered concussion resulting in confusion but retained consciousness, more than a quarter (27.3%) suffered symptoms. This suggests a high correlation between head trauma and the occurrence of subsequent psychological problems. The authors of the study note that ‘concern has been emerging about the possible long term effect of mild traumatic brain injury or concussion...as a result of deployment related head injuries, particularly those resulting from proximity to blast explosions’

Although these results are preliminary, if confirmed they have profound implications for anyone trying to understand the nature of warfare in the ancient world, especially the Western world.

So why does it matter?

In Roman warfare, wounds were most often inflicted by edged weapons. Romans did of course experience head trauma, but the incidence of concussive injuries would have been limited both by the types of weapons they faced and by the use of helmets. Indeed the efficacy and importance of headgear for example can be deduced from the death of the Epirrote general Pyrrhus from a roof tile during the sack of Argos. It is likely that the Romans designed their helmets with an eye to blunting the force of the blows they most often encountered. Connolly has argued that helmet design in the Republican period suggests a crouching fighting stance (see P. Connolly, ‘The Roman Fighting Technique Deduced from Armour and Weaponry’, Roman Frontier Studies (1989). However my own view is that the change in helmet design may signal instead a shift in the role of troops from performing assaults on towns and fortifications when the empire was expanding (and the blows would more often rain from above) to the defence and guarding of the frontiers.

While the evidence is clear that concussion is not the only risk factor for PTSD, it is so strongly correlated that it suggests that the incidence of PTSD may have risen sharply with the arrival of modern warfare and the technology of gunpowder, shells, and plastic explosives. Indeed, accounts of shell shock from the First World War are common, and it was in the wake of that war that those observing veterans suspected that neurological damage was being caused by exploding shells.

For soldiers of the Second World War and down to our modern day, an artillery barrage is like an invention of hell.

As one American put it in his memoirs of fighting the Japanese at Peleiu and Okinawa, “I developed a passionate hatred for shells. To be killed by a bullet seemed so clean and surgical but shells would not only tear and rip the body, they tortured one’s mind almost beyond the brink of sanity. After each shell I was wrung out, limp and exhausted. During prolonged shelling, I often had to restrain myself and fight back a wild inexorable urge to scream, to sob, and to cry. As Peleliu dragged on, I feared that if I ever lost control of myself under shell fire my mind would be shattered. To be under heavy shell fire was to me by far the most terrifying of combat experiences. Each time it left me feeling more forlorn and helpless, more fatalistic, and with less confidence that I could escape the dreadful law of averages that inexorably reduced our numbers. Fear is many-faceted and has many subtle nuances, but the terror and desperation endured under heavy shelling are by far the most unbearable” (see E.B. Sledge, With the Old Breed at Peleiu and Okinanwa, 2007).

The psychological effect of shelling seems to result from the combined effect of awaiting injury while at the same time having no power to combat it.

There is another aspect that I alluded to above which is the psychological and societal conditioning of the Roman soldier. In other words a Roman male’s social and cultural expectations of his place in the world. Feelings of helplessness and fatalism were probably a less alien experience for most Romans – even those in the upper classes. In general, the Romans inhabited a world that was significantly more brutal and uncertain than our own.

This another way of saying that the Roman and 21st century combat are very different in a variety of ways that subject the modern soldier to a good deal more stress than the legionary was ever likely to suffer. And the Roman’s societal preparation – his life before the battle – was far more robust than that we enjoy today.

Take infant mortality. In the modern developed world, our infant mortality rates are about ten per thousand. In Rome, it is estimated that this number was three hundred per thousand. Three-tenths of infants would die within the first year, and an additional fifth would not make it to the age of ten - 50% of children would not survive childhood. Anecdotal evidence supports these statistics: Cornelia, the mother of the Gracchi, gave birth to twelve children between 163 bc and 152 bc; all twelve survived their father’s death in 152 bc, but only three survived to adulthood. Marcus Aurelius and his wife, Faustina, had at least twelve children but only the future emperor Commodus survived.

Then look at how that child grows up. The typical Roman child would be raised in a society that readily accepted ultra-violent arena entertainment, mob justice, frequent and bloody warfare as a fact of life. This was reinforced by religious and societal encouragement to see war as natural and beneficial, open butchering of food animals, a total lack of support structures for the poor and less able.

Compared to the legionary our modern soldier has been protected from such realities to a greater degree than at any other point in history, and will thus be far less well prepared for the horror of a warfare that contains far more stress factors than for a man who might fight a handful of battles in his military career, with long periods of relative calm in between, state of war notwithstanding. Modern special and elite forces training often emphasises the brutalisation and ‘rebuilding’ of the recruit in readiness for this step into darkness, but it seems likely that no such conditioning would have been needed two thousand years ago.

I would argue that we experience war very differently from the way the Romans did. Our modern identity is defined far more by our Western Christian heritage than our Western Classical roots. They are in fact world apart when it comes to ethics and morality. Consider the fact that when we talk of war and killing today we often do so through conflict between our civilian moral codes – which offer the strict injunction not to do violence to other human beings – and wartime, when men are commanded to violate such prohibitions. It is a terrible thing to try to navigate ‘Thou shalt not kill’ and the necessity of taking a life in combat.

It is sometimes the case that the qualities that make the best soldier do not make the best civilian, a point amply attested in Greek poetry by heroes such as Heracles and Odysseus.

The Romans, for their part, celebrated heroes such as Cincinnatus, who could command effectively and then leave behind the power he wielded to return to his humble plough. It is important, however, when evaluating combat and its effects in the ancient world, that we do not read our ambivalence about violence onto the Romans. They inhabited an empire whose prosperity was quite openly tied to conquest.

As M. Zimmerman writes in his academic article, “Violence in Late Antiquity Reconsidered’ (2007), “The pain of the other, seen on the distorted faces of public and private monuments, or heard in the screams of criminals in the amphitheatre, reassured Romans of their own place in the world. Violence was a pervasive presence in the public space; indeed, it was an important basis for its existence, pertaining as it did not only to victories over external enemies but also to the internal order of the state.”

Violence then was both the means and the expression of Roman power. The Roman soldier was its instrument. The Roman warrior then would have brought a different perspective to lethal violence, and would have had a far more restricted moral circle to his modern counterpart – his friends and family, clan, patron and clients, as opposed to millions of fellow citizens via the internet and social media.

Part II follows next post

#question#ask#PTSD#war#roman#greek#classical#legionary#spartan#mental health#depression#trauma#warfare#british army#mental illness#homecoming#soldiers#combat veterans#veterans

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

what are the top ten most interesting people in history to you?

10. Catherine de’ Medici: said to be one of the most powerful woman in Europe

9. Charles V: the heir to three of Europe’s leading dynasties and his domains ranged for 4 million square miles

8. Richard lll of England: last king of York, and a mystery of whether he murdered his two nephews has never been solved

7. Henry VII of England: the first of the Tutors

6. Roman Emperor Tiberius: said to be one of the greatest Roman generals, but was known to be a dark ruler

5. Caligula: Tiberius’ heir, who was INSANE

4. Alexander The Great: one of the world’s most successful military commanders: undefeated in battle

3. Marco Polo: the first person to document their travels to Asia, and the Mongol leader refused to allow him to leave

2. Thutmose III: conquered 350 cities and was a military genius, and considered the greatest Egyptian warrior pharaohs that transformed Egypt into an international powerhouse

1. Leonidas the legendary King of Sparta: who sacrificed himself and his 300 men to protect Greece from an invading Persian empire, famous words when asked by the persians to give up their weapons: “come and get them!” when seeing that they were surrounded; he commanded the remaining greeks to return and defend the city, 300 Spartans and 700 Thespians and himself stayed behind to protect the city and were killed in a trap.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Babylonia Section 3~Section 4

Mean time while waiting for news on Christmas event this year + recovering Command Seals on JP again... Let’s return to the adventures in Babylonia where the crew finally makes a visit to the oldest King, Bilgamesh!

Section 3

Finally inside the royal hall aside Merlin being avoided by woman as usual... Looks like King Gilgamesh is busy with tending matters on the war and city... Definitely chaotic despite the outlook outside the castle...

While we see the good side of Gilgamesh caring for his men and people... Merlin decided to not beat around the bush and threw the crew to meet the King himself!

The High Priestess, Siduri, scolding Merlin in mean time for his lacking in his work...

... WOAH WAIT WHAT?! DINGIR?! THE NOBLE PHANTASM?!

MERLIN YOU FUCKING IDIOT! TALKING VIA FIST DOESN’T MEAN ALL OF US ARE READY TO DEAL WITH HIM, YOU STUPID COCK WIZARD!!

I realized while starting this fight... This isn’t my JP account without Merlin already existed... And about King Gilgamesh Caster, he isn’t a problem since skills wise, he doesn’t have anything to pierce defense along with his NP. But he buffs high on his attack, so it still hurt like a bitch when you don’t expect it

Your AOE Rider, Santa Artoria Alter (Welfare Servant), ideal to bring to clear the mobs along with him

......... Facing the wrath of his NP and we survived one way or another... Gilgamesh seems completely upset with the crew that even he held back halfway? So much for fist-talking...

Nevermind on second thought and as expected, the Gudas and crew are the usual mongrel that’s not even worthy of him and his time >.>

Even better, you worked your ass to give your name and he doesn’t bother! Or actually, he already knew with Clairvoyance from the start! Or actually again, he didn’t knew or bother because stupid dick wizard never told him!! >.>

And even better, he saves us the day of having the grail... WITH HIM ALREADY?! W-W-WHEN AND HOW?!

Okay, seems like even if we offer to help him defeat the three Goddess... We’re now the newly-recognized Clowns from the future who somehow made him laugh, huh...

Though while he deny us the last time... Looks like Ishtar decided to drop by and say hi to King Gilgamesh, much to the latter’s unamusement... Oh hey, she crashed in after Gilgamesh insult, as per usual by Siduri’s comment

Even a soldier seems smarter to leave from the sight of an angry goddess! KUDOS TO YOU MY FRIEND!

Gudas even remembered to bring this to the royal court, CHARGE HER FOR VEHICLE ACCIDENT! Oh and lastly, looks like King Gilgamesh decided to join us for this fight alone to teach Ishtar a lesson

I had doubts to bring Jeanne now after I remember her second skill... But thankfully, she uses extra attack for this fight... TIME FOR PAYBACK ONTO THAT HORRIBLE DRIVING LICENSE OF YOURS!

After kicking that spoiled rotten Goddess out of there... For some reason, Ana is invovled? Hmm?

Welp, at least she’s gone after picking up her pillow because she happened to be on a stroll, freely overlooking at Uruk, freely plucking her bow, freely ravaging the lands... Even Demonic Beasts have taken up north... Siduri, please don’t raise a white flag for this spoiled goddess!

Unfortunately, so much for working together, Gilgamesh definitely not even going to listen to the Guda crew at all... WOAH WHAT?! MERLIN’S MASTER IS KING GILGAMESH?!

Now that explains why he’s a Caster instead of that fucking Archer version... After complimenting us, we earned SORT OF a position to finally have him listen to us... Bottom to top, ehh... We’ve been there, so take care of us Siduri! Including kicking us out of there too, haish... OTL

Siduri herself... She’s a pure soul... At least she’s kind enough to lessen the burn from Gilgamesh’s words. So it’s time, to do our part-time job in working around Uruk!

Section 4

A decent private lodging in Uruk, a new home base outside Chaldea while we clear this Singularity :)

While Da Vinci has given trivia on the Age of Gods, the set up for summoning is ready! Celebration with feasts at our new job on the first day... The irony of life when I think about dreading to go to work OTL

Oh look, we’re reunited with Benkei and Ushikawamaru! Which apparently, Gilgamesh summoned them too... Along with the best tanker, LEONIDAS! :D Ah, seems like the ones we know in Uruk are a different copy from the one in Chaldea if they are in there (WHICH SHOULD BE ALREADY SUMMONED IN CHALDEA OTHERWISE)

And it makes more sense... Looks like rather than summoned... They sort of reincarnated to a more human form after summoned for a while from Gilgamesh himself...

Back about “Enkidu”... Even Uruk can’t believe what had happened before their eyes about them... :( Siduri also commented what the real Enkidu would be like after their relationship with Gilgamesh. Surprisingly, Gilgamesh seems uninterested at the appearance of fake Enkidu! Strange for a close relationship that he’s not saying anything...

Looks like we take care of Ana while some cock-head incubus out of a trip to a brothel, and a good rest is required after 3 chapters of tiring days the crew has been through

First day of work begins! We’re starting with shearing of sheeps for Mr. Limmat... Welp, we ARE starting from the bottom, Doctor Roman! So time to shear... 7 Berserker Demonic boars and 1 Shadow Servant... Are we really shearing sheep and shearing the farmer here?!

Okay thank god, we’re just killing the ghosts and the wild boars that’s attacking the ranch OTL And..... This is familiar, when you apply for a job and someone decided to take it from you instead... Ah the nostalgia, so much for shearing sheeps...

Second day, we’re to investigate Mr Kissinamuh’s wife who has been acting strangely....... Oh hey, private detective for marriage partner that wants to be NTR or something... At least Ana is having fun (I think) in helping a florist at the flower shop, so she can’t join us

But what does those fucking archer amor laser shooting mobs got to deal with an NTR Affair?! As from the Gudas... I’m really understanding lesser and lesser about Uruk...

<<NOT SCREENSHOT>>

.............................................. Okay nevermind, this is some weird anime plot... An undercover alien who disguised themselves as a human, going as far as being married to take over the world.... But in plot twist, they really did love their human and help save the human world....

Anyway, learning more about the Three Goddess alliance: three attack from all three direction of up north, south, northeast... And hence the problem despite Leonidas responsible at the north of Uruk...

Eh? The grail Gilgamesh have isn’t the era’s Holy Grail for this?! And the plot thickens... If Gilgamesh’s own grail is obviously his from the start... Where and who’s using Solomon’s holy grail...?

Day 3, a break from work, the crew is training with Leonidas! Or rather a job from Spartan training with 100 soldiers... I thought we’re done with his interlude to stop that

Leonidas.. The Gudas are still normal people, at least 60 is already more than enough to deal with at their capacity... ==lll

But still, Leonidas is definitely a great teacher and commander to inspire his army for Uruk :) Despite the confusing lecture he’s giving out...?

Seems like Ana doesn’t have any idea what a Servant means despite being one... And rejected the offer to be our Servant... I wonder if she really hates humans and fears one so much to not want to be a Servant to anyone...

Day 4, looks like the Gudas returned from their odd job. And Ushikawamaru as usual angered King Gilgamesh... Leonidas also returned to join us for dinner :D

Damn, Siduri’s butter cake made Ana enjoying the dessert a lot! Merlin’s back with a kick from Fou in the face too :D Now DW, can we get the option to send food to Doctor Roman? He’s feeling lonely too despite what he said?!

Day 5, or Day 20 nearly 3 week since the Guda started their life in Uruk... The Gudas got a day off or thankfully a job from Ana! But fight..? Wonder where we are headed to... With 6 ghosts and 1 Soul Eater?

Ah, it seems we’re exorcising evil spirits along with her... Turns out there was spirits spreading deadly disease in Uruk, spiritual death rather than physical death. Spiritual death considered as an illness rather than departing...

While Mash helps Ana to explain Siduri... The Gudas met an old man... Familiar one? Nevermind looks like what Merlin would have been if he isn’t that too dick-headed!

The Gudas decided to give the old man food, which... A cryptic warning was given to them by the old man. But also a compliment for their insight and thoughtfulness... Three storms will come to Uruk, empathize not with the hateful ones and celebrate not with the joyous ones... And extol not the pained one...

Woah okay, he disappeared the moment they demand of his identity! A cliffhanger to end for this chapter... Three storms... Damn trouble is already brewing to end the daily life in Uruk...

I’ll end things here since I need sleep after one bullshit in Lostbelt... Will be back later/tomorrow to continue things in Babylonia!

#fgo#fate grand order#babylonia singularity#the shit I shit myself into#the calm before the storm...#can't wait for tomorrow to see the story#BUT NOT LOOKING FORWARD TO THE BATTLES DEFINITELY#babylonia NA

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Teen Titans x Halo Part 4

Year 5, Starfire's looking upon the horizon of Far-side with her Spartan-lll lieutenant, Bailey. Starfire is in charge of 2 Battalions, one on Far-side, one on Targon, with a Spartan-lll lieutenant for both. Both are named Titan Battalion, to remind her of her friends. The soldiers have been there to support her in her defense operations for 4 years now, and they've been through a lot together.

Ella is doing fine, her powers steady. She's not as powerful as Raven, but is learning fine. Hopefully Raven taught Starfire enough to tide Ella over until Raven portals her way to this universe.

Suddenly, a helicopter explodes in the distance. Then a big green missile is headed for her. An evil Green Lantern attacks. Starfire tells Bailey to head to base and warn them. She fights the lantern, grabbing the green jerk and tossing him into a man sized crater. But then an evil Flash attacks. She fights him too. He may be fast, but she's trained against 3 speedsters at once. A clothesline attack sends him sprawled in the dirt. Then the rest attack.

After a big fight, Starfire manages to beat back an evil Wonder woman, Flash, Batman, Green Arrow, Martian man, Aquaman, Wildwoman, Green Lantern, Black Canary, and other Injustice members.

Then Evil Superman shows up. Starfire immediately calls for a planetwide evacuation, tells her lieutenant Superman's weakness is kryptonite. Saying it was an honor to work with them, she turns of the helmet, she tosses it aside.

She fights Superman in a brutal 1v1, crashing through buildings and several fields until everyone evacuates. As the second to last ship of the UNSC escapes, Superman realizes he's been stalled. Slightly perturbed, he then knocks her through some buildings, she crashes into the outskirts, and falls unconscious.

0 notes

Note

The smaller Spartan's head kept looking around. Not entirely registering that the taller one was speaking to her just yet.

Safe. Safe. Was she safe? Unsure. Unsure.

Then it eventually clicked, a voice was talking to her. She looked up at him, sky blue eyes clouded with worry and something dangerously close to fear. He was big enough to scare her handlers away right? He was too tall to be a IV, and he didn't look much like a lll either. Then again she could be wrong, but a lll works just as well as a ll.

"Uh, um...h-hello."

Ethier she was too anxious to speak properly or she rarely spoke in general. But her voice was quiet, she sounded so...small.

🤝 for Spartan Wash

From @the-tired-spartan

David wasn't entirely sure when the last time he'd slept was. His most recent deployment been of a rough mission, and since returning to the Infinity, he'd barely had a minute to himself. Which wasn't out of the ordinary; he was just getting used to being busy, again.

So he was surprised to find himself being jerked back to reality by a small hand sliding into his own.

Cocking his head, he glanced downwards to find a — kid? she appeared to possibly be a younger Spartan-IV — almost pressed anxiously to his side. Apparently, for whatever reason, he was yet again a source of fascination — or safety, perhaps — for another Spartan aboard the Infinity.

"Uh, hey there."

( @the-tired-spartan )

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blue Team [Master Chief | John-117 + Fred-104] relationship headcanons

Didn't realize that Tumblr now has a character limit, so Kelly and Linda's will be on another post.

Kelly + Linda

It took less than a week into your relationship to realize John's love language is doing acts of service. He's great at listening and if he hears you're having a problem and he can fix it, you bet your ass the Master Chief will go out of his way to help. You're hungry? John will disappear for ten minutes and bring you back a plate of food with too much on it. John sees that you're struggling to carry something, this man will appear at your side and take it from you. Is someone bothering you? Not anymore.

Maybe not immediately, but John will eventually abuse his position for you, whether it's to keep you safe, or reroute orders to have you on his team to simply seeing the joy on your face receiving something you've wanted, he has no shame. John's had too much taken from him, and he's not abusing his power to hurt anyone so it's okay in his mind.

Kelly just stares at him with her mouth slightly agape when she witnesses him do something like this for the first time. She was certainly not expecting it but also John says it's okay, so it's okay.

Firstly when the rest of Blue team find out John's in a relationship, Fred drops whatever he's holding, Kelly calls bullshit and Linda is the one to stop Kelly from approaching his partner and grilling them for answers. Once the surprise dims down, they're all pretty supportive and protective of his partner. You're something good that's happened in his life and they respect that, especially once they find out you asked John out.

They want to know everything, so they can tease the hell out of the Master Chief. Especially Kelly, Fred's here for the ride and Linda will simply find out one way or another.

Patience is a key virtue when in a relationship with any Spartan, more so, the lls and llls. They were taught to be soldiers and get missions done, regardless of the sacrifice. Interacting with anyone outside their Spartan families was almost frowned upon. This being said positive reinforcement and communication with John is a must. He doesn't know what he's doing, this is all new for the spartan, so please talk with him. And he'll do his best to work on his communication with you if something is bothering him.

John is awful at telling you he's uncomfortable with certain things, whether it's something he doesn't understand or with how fast things could be proceeding. He won't say anything but when he tenses up, that is his dead giveaway. So you'll need to ask him what's wrong or tell him you know something bothering him.

After a certain point, you'll be able to recognize meaning in his movements, not fully understand Spartan gestures unless they teach you but you can tell when he's annoyed about something or when he's excited to see you and visa versa, John's able to tell what kind of mood you're in from across the room.

Unless you're adamantly against it, be ready to learn how to defend yourself if you don't already. John makes it his personal mission to teach you how to use different weapons and how to spar, hell even if you know how to defend yourself John will be teaching his partner new ways of sparing and pointing out mistakes you're making. He knows the training you received, if any, wasn't like his but he can help you improve.

John is also one who will gladly go on morning runs with you, yes he is faster, but he doesn't mind slowing down his pace to stay with his partner.

There isn't any doubt that John's protective by nature, if he has to pull rank to get you to listen, he will, especially if you're injured. John knows you can take care of yourself but he can't help it, he's lost too many.

You'll notice that John will stand closer to you after the relationship is first established. He does it subconsciously like he's ready to jump in front of you to protect his partner at a moment's notice.

There is an unspoken agreement among the Spartans to watch out for each other's significant others if they have one, so you can bet if you get into a fight with anyone, Kelly will be the first to jump in.

In the beginning, you'll need to instigate most things until he gets comfortable enough to do, more often than not behind closed doors. However, when he needs to reassure himself you're safe and there, the only thing he'll do is gently grab your hand and give it a squeeze before letting go if you happen to be in public.

The man might never admit to your face, but Fred likes hugs, specifically your hugs, and everyone on Blue team knows it. As do you. It's really not a secret even though he refuses to talk about it. He just likes holding you, or when you hold him, Fred isn't picky. He's lost alot of people and when you're in his arms, he feels like he can protect his partner from the realities of the world. The first time you asked to hug him, the lieutenant tensed up so visibly that you thought you offended him. Fred was so confused and might've short-circuited, don't mind him, he's just being our confused puppy.

Kelly did in fact tease him about how quickly he melted into your embrace and how it took him a full minute to mirror your actions. She likes telling him, 'Don't freeze this time.' whenever you show up. Linda had also boarded the 'tease Fred over this' train and you bet your ass she will tell John when they see him next.

The first time you kissed Fred's cheek, completely flabbergasted, he didn't know what to do with himself and just said 'thanks?' after a few minutes of staring at you. He makes you swear to never tell the others.

Never let him live this down. The Ferrets heard about it and now make fun of him for it [in a very loving way for Spartans]. Anytime he does anything for them, they just say 'thanks?' and he's confused before he hears one of them snicker softly. You have witnessed Mark of all people doing this to him while off his smoother, to say you almost died laughing is an understatement. tbh Mark is really proud of himself for this.

Also if you ever kiss Fred on his helmet in front of the Ferrets, Olivia will gasp and say "What about me?" then pretend to be offended. You hugged her once and she hella tensed up before forcing herself to relax and after a minute remarked, "This is nice."

Fred only starts understanding how touch-starved he is when you come skipping along into his life. Like, he didn't believe that was a thing until recently because he will take every chance to hug you when in private. He gets genuinely happy to have your attention at any given second as it makes him feel validated, and if you voice that you like his hugs or attention, he feels like he's doing great and could conquer the world.

Please tell him he's doing good in the relationship. We all know Fred's got some anxiety, so positive validation is important to him, whether he realizes it or not. He stresses when he hasn't seen you in awhile because he thinks you might be upset but you knew what you were signing up for when getting into a relationship with him. Tell Fred, he's fine and that yes, you still love him and will continue to love him, regardless of the distance.

Sit with him while he does paperwork, Fred enjoys your company and likes sitting next to his partner when working.

On the unspoken agreement to watch a Spartan's S/o's back, Olivia has stood behind you getting ready to jump into a fight about to throw down between you and an ODST. She's not going to stop you simply out of respect nor get Fred but you bet she's gonna help and if Ash or Mark find out, you got the gammas rolling up their sleeves.

This stresses Veta out when the ferrets disappear to have your back, only to find them celebrating their win and the only defense they have is "it's the spartan agreement."

Some Retirement! Blue Team headcanons next anyone?

#Halo#halo series#master chief#john 117#fred 104#halo headcanons#headcanons#john 117 x reader#fred 104 x reader#master chief x reader#blue team#halo x reader#i could just give these two a million kisses

77 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Shein cut and sew faux fur panel sweatshirt contest LLL by naomig-dix featuring Imusa

Pressbox vintage tee / Long sleeve sweatshirt / High-waisted jeans, $42 / Print bag / LogoArt gold plated jewelry / Long chain necklace / Forever Collectibles acrylic scarve / Forever Collectibles knit glove / Print iphone case / COVERGIRL brow makeup / Covergirl face makeup / Nail care / Imusa small appliance / Top of the World Women's Michigan State Spartans Palette Cap

#polyvore#fashion#style#Pressbox#LogoArt#Forever Collectibles#COVERGIRL#Imusa#Top of the World#Old Spice#clothing

0 notes

Text

Jun-A266, the sniper from Noble Team.

Halo: Reach concept art, 2010.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

I never thought you meant animated shows are worth less no worries!

I'm very sad about them ignoring the established lore. There's so much good lore they could have chosen from but noooo....

And I totally agree with you that there's soooo much potential for an amazing Clone Wars esque Halo animated show! I'd love it to be centered around the Forerunners and the Flood but it could also be really cool to see things about the Spartan lll's, ONI, or even something from the Covenant's point of view! (I want more Sangheili cultural lore please 343!)

mad because the halo show is visually stunning but looks terrible as a show

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Catherine-B320 (Kat) from Noble Team.

Halo: Reach concept art, 2010.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Halo: Reach concept art.

2010.

#halo reach#concept art#game#halo#jorge#emile#carter#2010#noble team#jorge 052#spartan#spartan ll#spartan lll#carter a259#emile a239#noble one#noble four#noble five

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Halo: Reach, 2010.

9 notes

·

View notes