#south african galago

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Go Go Southern Lesser Galago!

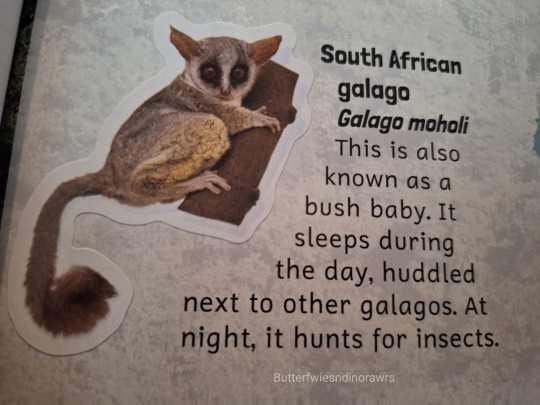

Also known as the South African galago or the mohol bushbaby, the southern lesser galago (Galago moholi) is a small primate from the Galagidae, or bushbaby family. As the name implies, they are located only in southern Africa, from northern South Africa up to Rwanda. Their preferred habitats are savannahs and semi-arid woodlands, where they can often be found high in the canopy, and they are particularly associated with Acacia trees.

The mohol bushbaby is one of the smaller members of its group; at full height they stand no taller than 15 cm (6 in) and weigh only 225 g (7.9 oz). In fact, their tail is longer than their body, easily reaching 23 cm (9 in) in length. While it isn't prehensile, the tail is still an important tool for climbing as it gives G. moholi an excellent sense of balance. Along with their incredible tails, the South African galago also has one of the largest sets of ears of any primate, proportional to its size; these ears can move independently to help the southen lesser bushbaby avoid predators. G. moholi's final distinguishing feature are their eyes, which are incredibly large and a distinctive orange color. Individuals themselves tend to be gray or light brown, which helps them blend in with their surroundings.

South African galagos are almost strictly nocturnal. At night, they forage through the canopy for moths and beetles. These bits of protein, however, are supplemental; the mohol bushbaby's primary source of food is gum, or hardened sap from the Acacia plant. G. moholi has several adaptations allowing it to specialize in gum extraction, including scraping teeth on the lower mandible; long, rough tongues; and digestive systems that have evolved to break down and ferment the tough substance. Because they have very few defense mechanisms, southern lesser galagos are a common prey for many nocturnal species like eagles, owls, snakes, mongooses, civets, and gennets.

One of the few ways the South African bushbaby avoids predation is through its social units. Groups of 2-7-- typically composed of a female, her young, and a few non-reproductive relatives-- forage together. In these groups, their collective night vision and highly-developed hearing allow them to detect and alert each other to predators long before the threat is immanent. While individuals forage seperately, they keep in contact via loud, high pitched calls that can serve as a warning for predators, a point of contact between mother and offspring, or a territorial warning between males.

Male G. moholi live seperately from social groups, and are highly aggressive against other males invading their territory. This area often overlaps that of several female-led groups, but they only come in contact with each other during the mating season. Unusually, the species has two mating seasons through the year; from January to Februrary (late summer) and from October to November (early spring). Following a gestation period of 120 days, females produce a single set of twins each mating season. Each set is weaned after approximately 3 months, and young become fully mature at 300 days. Female offspring may join the mother's group, while males leave to establish their own territory. In the wild, an individual may live up to 16 years.

Conservation status: The IUCN has classified the South African bushbaby as Least Concern. Studies have indicated that the population is stable and, in some areas, increasing. However, in other areas the species is threatened by habitat loss and possibly capture for the pet and bushmeat trade.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Gerald Doyle

Peter Webb via iNaturalist

#Southern lesser galago#south african bushbaby#Primates#Galagidae#galagos#bushbabies#mammals#savannah mammals#tropical forest mammals#africa#south africa#animal facts#biology#zoology

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to Aminal Facts Wiff Zaboo! Part 5

South African Galago!

These adowable cuties by many names is also called nagapies which means night monkeys where they're from. Zaboo is excited because dey is primates too! Along wiff their big big eyes dat helps dem see at nights dey has adapted to nocturnal living (ninja monkeys proofs #1 🥷🐒-ninjas go outs at night) wiff little satellite-like ears dat rotate independently to zero in on prey at nights. (ninja monkeys proofs #2 🥷🐒- sneaky stealthy skills for detecting) Dey eats insects which dey catchies in da air wiff dey super quick reflexes (ninja monkeys proofs #3 🥷🐒- ninja reflexes), tree gum n dey favowite is acacia tree gum, fruit n even small aminals like frogs n birbs! Dey grow to be about da size of a large squirrel 6 inches (15 centimeters) in dey body, n dey tail stretchies up to one n a half dey body, about 9 inches (23 centimeters). Dey has a special ability to store energy in dey tendons dat let's dem achieve massive jumpies dat muscles alone could no do... in 4 seconds it can jumpies 5 times to get overall jumpies of 27.9 feet (8.6 meters)!!! (Ninja monkeys proofs #4 🥷🐒- ninja jumpies) Dey has a tooth-comb which is made up of lower incisors n canine teefies dat dey use to grooms n cleans demselves. Dey is social aminals dat lives togeffer in small families of 2-7, sometimes more but dey go hunting alones at night. (Ninja monkeys proofs #5 🥷🐒- lotsa ninjas works alones)... Dey also nose boops! Dey has been seen pressing dey noses togeffer as dey like cuddling n showings affection. Dats just da cutest! 🥹🥰

N finally a final fact...dey get dey nickname bush baby from da various cries, squaks, n grunts dey makes dat sounds like human babies!

Also if yous coulds no tells Zaboo n I is convinced dat these little monkeys is ninjas! 🥷🐒 .. What do yous think?

📢📌🚫🔴🚨🛑

*runs awound hollering n making ambulance sounds*

Alert, alert, ALERT!!! Spookiness aheads, proceeds wiff cautions!!!

📢📌🚫🔴🚨🛑

Now a spooky fact for da spooky loving babies out there, there's a legend dat says dey kidnap babies n da cries you hear are actually da babies... another legend says dey sounds are really mades by a giant snake wiff a feathered head n rainbow colors which kills intruders... to dis day even though da galago is not dangerous to humans it considered a bad omen to hear dem as it means danger or death is near. Now researchers think dis all started as a story to keeps kids indoors at nights but a quick search into dis topic yields a lot of interesting infos.. if yous like da spooky spooks!

#aminalfactswiffzaboo#agere#agere blog#agere little#agere community#sfw agere#age regression#age regressor#agedre#agedre community#agedre blog#sfw agedre#age dreaming#sfw little post#sfw little community#sfw little blog#sfw little stuff#sfw littlespace#sfw age regression#sfw caregiver#sfw regression

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

South African version of the Raccoon Man [Bushbabies]

VERY EASY READ ON THESE CREATURES

0 notes

Text

Episode 7: First Rank

Image credit: Biswarup Ganguly, under CC BY 3.0.

The following is the transcript for the seventh episode of On the River of History.

For the link to the actual podcast, go here. (Beginning with Part 1)

Part 1

Greetings everyone and welcome to episode 7 of On the River of History. I’m your host, Joan Turmelle, historian in residence.

When the Swedish naturalist Carl von Linné (perhaps more familiar under his Latinized name, Carolus Linnaeus) took up the self-motivated task of classifying all of the then known organisms on the Earth, he placed humanity in an order he called Primates, meaning “first rank”. This gave the implication of a grand position in the system of nature, or Systema Naturae, which was the Latin title of his work. It was Linnaeus who gave the world our species name, Homo sapiens, and the 10th Edition of his book was recognized by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature in 1999 as the starting point of the official scientific naming system for animal life. Thus, our species name, and the group name Primates, is here to stay. Humanity was not alone in Linnaeus’ mammalian order, for they shared space with 32 other animals, including monkeys and lemurs (as well as bats). To Linnaeus, primates were united by cutting fore-teeth, solitary tusks on each side of the jaw, two pectoral teats, four feet (of which two are hands), usually flattened oval nails, and a diet of fruits and sometimes ‘animal food’. When critics questioned him for the sheer audacity of grouping the species that begat Shakespeare and Louis the 14th with the likes of lower animals such as baboons and capuchins, Linnaeus returned with a very basic retort:

But I seek from you and from the whole world a generic difference between man and simian that follows from the principles of Natural History. I absolutely know of none. If only someone might tell me a single one! If I would have called man a simian or vice versa, I would have brought together all the theologians against me. Perhaps I ought to have by virtue of the law of the discipline.

In the 260 years since the name Primates was coined, the work of countless biologists, paleontologists, and anthropologists has confirmed our relationship to these other, furrier creatures. While the outline and structure of the primate group has changed (for one, we don’t include bats anymore, they’re not close relatives at all), the basic idea behind it remains the same. Primates all share a suite of traits, including opposable thumbs for ease at collecting food or branches, forward facing eyes that allow stereoscopic or 3D vision, a large braincase compared to the size of the body, flattened nails rather than sharp claws, among others. This group is also united by genetics, and DNA sequencing has allowed us to better understand how all the different members of the group are related to each other. And, of course, the fossil record has supplied us with an ever-growing catalog of great remains, from the earliest primates to the rise of humans. Even though we’ve just spent the last episode bringing the history of the world up to 2.58 million years ago, we need to backtrack, so I can tell you the story of the primates and of the first peoples.

We return to the recovering world of the Paleocene Epoch, 63 million years ago, following the great mass extinction what wiped out 75% of all life on Earth. The planet is covered by tropical forests. By this point, primates were represented, like most of the other placental mammal groups, by small, scurrying animals that sought refuge in trees or along the ground. The closest relatives of these were the plesiadapiforms, who resembled squirrels or treeshrews, with long snouts, clawed digits, and continuously-growing incisor teeth. We know that this group wasn’t ancestral to the primates because most members of the group lack premolar or canine teeth, which are features that all primates share. Plesiadapiforms took the niches that modern primates as well as rodents share today, so when those groups had evolved by the end of the epoch, 57 million years ago, they couldn’t compete with them and died out.

True primates were established somewhere in southern Asia (the earliest fossils have been found there) alongside their euarchontoglire relatives the rodents, rabbits, treeshrews, and colugos. Soon after, they diverged into two lineages. One of these is the strepsirrhines or the wet-nosed primates, because they retain a rhinarium: the wet and leathery tip of the snout that you often find in dogs, cats, and many other mammals. This group is represented today by the lemurs of Madagascar, the lorises of southern Asia, and the galagos or bushbabies of Africa. However, in the Paleocene and Eocene, their range extended much more than this: after having evolved in Asia, they spread out in opposite directions, with some members going to Europe, others crossing into North America, and some extending south into Africa. As the world was still warm, wet, and forested, these primates thrived as they feasted on insects and other small invertebrates. It was around 54 million years ago that the lemurs arrived in Madagascar from Africa, possibly by rafts of floating vegetation that ran off the east African coast following a storm. It sounds ridiculous, but considering recent footage of tsunamis and how they transport large quantities of debris, it is not improbable. Following the cooling of the planet after the Eocene and the shrinking of the tropical forests, most of the strepsirrhines died out across Africa and Asia (and all of them perished in North America and Europe), leaving only the ancestors of the living species today.

The other great lineage of primates to emerge was the haplorrhines, or the dry-nosed primates: because they lost their rhinarium and their snout in place of a smooth and naked nose above a separate upper lip sported on a flattened face. They also developed a change in their skull morphology where the eye-socket became covered by a thin layer of bone along the backside. This is in contrast with lemurs and their relatives who only have a thin bone called a postorbital bar that borders the eye at its side: other mammals lack this altogether. Like the strepsirrhines, haplorrhines originated in Asia and spread out from there, this time colonizing Europe and Africa only. The earliest members of the group resembled tarsiers, which are small, large-eyed, nocturnal, insectivorous primates that reside in the rainforests of southeast Asia, though in the past they were very common, ranging as far as China. Incidentally, the tarsier lineage makes up one of two descent groups from the common ancestor of the haplorrhines, the other being the anthropoids or monkeys.

Monkeys developed many distinct traits from the other haplorrhines, and their group split from the tarsier line roughly 40 million years ago in Asia. Whereas their common ancestor (as well as the common ancestor of all primates) sported sensory whiskers along the front of the snout, monkeys lost that trait as they developed their eyesight to sport full-color vision. This proved to be a beneficial adaptation, as monkeys began to rely on colorful fruits as a major food source instead of insects, though they also seem to have eaten seeds and nuts as well. There were also key changes to the reproductive system: monkeys reduced their number of nipples down to one pair and their penis was no longer mainly attached to the body and instead hung down. Over time, monkeys grew larger in size and expanded into Africa, where one lineage eventually colonized South America by 25 million years ago, perhaps by the same process that could have delivered the caviomorph rodents (a floating raft of vegetation). These were the platyrrhines, who have earned the common name “new world monkeys”, and include capuchins, marmosets, howlers, and squirrel monkeys. These monkeys are distinguished by a flattened nose with nostrils that stick out sideways, whereas other monkeys have a more curved nose with downward-facing nostrils. Most iconic is the prehensile tail that many platyrrhines use like a fifth limb for grasping onto tree-branches: no other primates have this trait.

Back in the “Old World”, the other lineage of monkeys, the catarrhines, were facing environmental pressures in Eurasia as the climate began to cool, and it was around the start of the Oligocene that they mostly died out there. In Africa, however, they were thriving, and they diversified into a few groups. These monkeys mostly ate leaves and fruits, and they were very adept climbers in the trees. Eventually, the climate started warming again during the Miocene around 20-17 million years ago and many catarrhines returned to Eurasia as far as southeast Asia. Earlier in Africa, roughly 28 million years ago, one lineage of monkeys started growing in size as they broadened their chests and increased their brain case. Their tail vertebrate reduced in number until no visible tail was present at all. The joints of their shoulders, also, were more relaxed and mobile than their ancestors, meaning that they could move their arms much more freely around their body. This gave them the ability to brachiate, or hang from tree branches by their arms and swing across the trees. These were the first hominoids: the apes.

When we think about human evolution, we often think about the concept of “human nature” and what traits and behaviors stem from our common ancestry with the other primates. Perhaps put more philosophically, what does it mean to be human? This subject has spawned some of the biggest discussions and debates in the history of our species, and this very curiosity seems to have deep roots, with many world societies across time devoting time to this. If we want to talk about the fundamental characteristics of the human species and what unites and distinguishes us from our relatives, we have to look at this topic holistically. It is not enough to simply tackle this subject from a purely genetic or cultural or environmental standpoint: all of these fields, and more, have to be taken into consideration. This is because there is not one shared aspect of all societies or any one gene that makes us human, all of these factors are working together, intimately, to shape our species. Anthropologist Elizabeth Brumfiel has made a valuable point about this: human biology, human psychology, and human behavior are all context dependent. This enormous biological and behavioral flexibility—the ability to adopt different physiological, perceptual, and behavioral repertoires—has enabled humans to survive across the extremes of climate and habitat, from the frozen tundra to the burning desert. Our environment has shaped our being, and our being has shaped the environment. There is a lot of argument between anthropologists and other researchers about this, so it is important to keep that in mind as we move forward. The more we learn, the more our understanding shifts or changes altogether. I might even return to this podcast many years from now and say “wow, we had this all wrong!”

Part 2

As a whole, primates have a larger brain case to body ratio than most other mammals, save for groups like elephants, toothed whales, pack-hunting canids, and hyenas. Bigger brains have often been hypothesized by biologists as tying closely to problem-solving, or how organisms acquire the resources they need in a challenging environment. Incidentally, these mammalian lineages are all social species, living in community groups of many individuals, and this too has been tied to large brains that allow for the processing needed for large group-living (though this correlation is controversial in that neuroscience – the study of the brain – is still uncovering new information). Primates are K-selected species and thus bare only a handful (sometimes just one) offspring that they spent much of their time nurturing, which includes educating the young on how to survive and interact with others. As such, primate childhood is remarkably longer than most mammals. While a young mouse or shrew may spend around 21-25 days with its mother, a chimpanzee can spend 9 years alongside its mother, and even then still remain nearby since, being primates, chimps live in large family groups. Alone, a primate is a vulnerable animal, lacking any means of defending itself from predators, save for a sharp bite or a powerful swing of the arm. But because primates live together, they can rely on each other for backup. When a group moves, one or two members may be on the lookout for dangers, while the others remain close by. When something is spotted, the primate can call and alert the others to the threat, and everyone can get to safety in the trees or even fight back if necessary. These behaviors are not universal among all primates, but they’re common enough throughout several lineages to give assurance that our distant ancestors could have had them too.

But what about uniquely human traits? What made our ancestors stand out from the other primates? That is a bit tricky to say, because since the dawn of scientific study, people gave many answers of varying quality. For many, humanity is special because of theological explanations: we were made special and separate from the animal kingdom, or even the natural world, by a divine force. However, such reasons are not appropriate here because supernatural matters are just that, outside of nature. Even if there was something supernatural about the world, we couldn’t use science to learn about it because scientific methods are based on and apply to natural principles. Not to mention the fact that all supernatural belief systems today are often tied to specific cultural practices and biases that are themselves products of the people who made them, and therefore not applicable to humanity as a whole.

For more naturalistic arguments, people have provided specific traits of the human body or specific behaviors that humans engage in that other organisms just don’t. Yet, on closer inspection, what we often think is human is actually present (if not common) among other animals. The use of tools was commonly applied to the humans, until it was learned that chimpanzees and other species use tools as well. In 1860s England two naturalists, Thomas Henry Huxley and Sir Richard Owen, sparked a grand debate. Owen argued that humans were unique among primates in having a specific part of the brain called the hippocampus minor (what we now call the calvar avis) that no other ape or monkey has. Huxley argued on the contrary, and it was later revealed that other primates indeed share this same feature of the brain, and that Owen has purposely suppressed that information for ideological reasons. In a significantly older (and more humorous) example, when asked “what is a man”, the Greek philosopher Plato simply stated that man is a featherless biped. This made sense, considering that birds walk solely on their hindlimbs but have feathers, while humans do not. However, this quickly backfired when a contemporary philosopher Diogenes presented a chicken with all its feathers plucked out and proclaimed, “here is Plato’s man”. If we want to understand human uniqueness, we need to do better. And, over the years, there has been enough insight to give us a good picture of our origins and how humans stood out among their cousins.

To begin our coverage of human evolution, let’s return to the story of primates. After evolving in Africa, apes were able to extend their range, and between 18 and 10 million years ago, apes ranged across Africa, Europe, and Asia. They had been among the most common and diverse of primates during that time, even out-competing many of the other monkeys that shared the world with them. The environment during this period was perfect for these primates. Lush tropical forests covered many parts of Africa and Eurasia, full of fruits and leaves. Over a hundred different types developed, well-suited to the humid forests. There was Dryopithecus: very similar to living chimpanzees, though it walked on the palms of its hands rather than on the knuckles. Little Pliobates: looking like one of the southeast Asian gibbons, but the structure of its arms prevented the kind of brachiation that gibbons do. Sivapithecus: with a curved face that reveals its close relationship to the ancestors of orangutans. And then, perhaps most spectacular of all, was Gigantopithecus. Paleontologists have only found a series of jaws and teeth, but these alone have told us so much. These were the largest apes that ever lived, reaching a standing height of perhaps 10 feet, but subsisting on little more than fruit and bamboo.

But then, following the massive environmental changes that occurred around the close of the Miocene epoch around 6 million years ago, the comfortable lands of the apes began to disappear. The tropical, humid forests that they relied on receded and in their place were extensive grasslands and a series of open-woodlands. Most of the apes could not adapt to this new world and they died out throughout their range. With their various niches available, the monkeys that previously occupied only minor roles in their ecosystems could now diversify into a great menagerie of forms. Some became folivores, and changed the anatomy of their guts to better process leaves – descendants of these include the colobus monkeys and langurs. Others developed cheek-pouches for storing food like fruits, nuts, and seeds – these include the macaques and guenons. Some members of the latter group left their arboreal existence for a more terrestrial lifestyle in the grasslands, reducing their tails and becoming quadrupedal, evolving into baboons.

The apes that did survive this extinction event went on to occupy specialized positions in the remaining tropical forests of central Africa and southern Asia, evolving into the first gibbons, orangutans, gorillas, and chimps. There was one other ape that managed to flourish in the new environments. Around 12-7 million years ago, two lineages of apes split apart from each other: one line developed into the genus Pan, which survives today as the bonobo and the chimpanzee; the other developed into the ancestors of humans. These hominins (meaning “of the tribe of humans” in Latin) would have looked very different from any chimpanzee as they had acquired many traits that made them distinct from their closest relatives.

The open-woodland habitats that hominins first inhabited would have offered abundant resources as far as food is concerned. This environment would undergo dry and wet seasons, meaning that a few months could mean the difference between full bellies and starvation. No doubt this would have been a scary place, especially with predatory animals like big cats, hyenas, and large eagles able to see their prey clearer (without dense jungle in the way). In these types of ecosystems, it helps to be a generalist (able to adjust to most living conditions). Indeed, many researchers have come to understand that the ancestral human body is the most generalized of all apes. The earliest hominin fossils add support to this. They include members of three genera: Sahelanthropus (7.43-6.38 million years ago), Orrorin (6.14-5.2 million years ago), and Ardipithecus (6.7-4.26 million years ago). With the little evidence they left behind, we can see apes with relatively unspecialized body plans. For example, the bones of Ardipithecus’ hand reveal a simple palmate walking pattern and the ability to grasp tree branches, not unlike the apes of earlier times. However, these apes show a number of distinct features that showcase their relationship to the ancestors of humans. Many features of their skeletons – the position of the foramen magnum (the hole where the spine attaches) at the base of the skull, the shape of the pelvis and limbs, the firm heel of the foot – demonstrate that these apes were already utilizing bipedal locomotion.

All apes are capable of walking on their hindlimbs, but humans are unique in that they are habitually bipedal (walking on two legs all of the time). Why? In these mosaic environments, a generalized body plan allowed for hominins to use both bipedal and quadrupedal locomotion in order to survive. Some of these hominins may have expanded their range outward onto the grasslands where there was less competition from others, and there they could find more food or at least other woodlands to travel to. It helps to see where you are going, as grasslands are often covered with tall, dense grasses and have large carnivores lurking about. And in a hot and dry environment, the need to move efficiently and conserve energy is critical (humans use 75% less energy moving upright than a chimpanzee uses on all fours). Perhaps this is why hominins became fully bipedal. We still cannot be sure about the intricacies of this transition – there are other hypotheses – but the fossil evidence tells us that this change did occur over a long period. You may have heard of the aquatic ape hypothesis: that hominins developed bipedality (among other features) in an aquatic environment. This is a bit of a fringe idea, not supported by most researchers and is actually contradicted by other geologic, environmental, and physiological data.

Africa continued to dry up, and the open-woodland forests started shrinking, only to be replaced by more savanna. The fossil record indicates that an evolutionary radiation of hominins (among other African faunas) occurred during this time, able to adapt to the over-expanding grasslands: these were the australopithecines: the name is a combination of Latin and Greek words meaning “southern apes”. A number of species developed between 4.02-2.2 million years ago all across eastern and southern Africa, each with its own unique characteristics and, certainly, its own behaviors.

One of the most recognized of this group was Praeanthropus afarensis which lived between 3.89-2.9 million years ago, made famous by a number of widely-publicized finds over the last few decades. For example, there is the Ethiopian specimen found by American anthropologist Donald Johanson and his team in 1973. The find was remarkable: roughly 40% of its bones were located – this doesn’t sound like much, but it was one of the better finds of early hominins during those years. They nicknamed the find Lucy, inspired by the party they threw following its discovery, during which the Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” was playing on a loop. Since that time, hundreds of remains have been unearthed, including individuals of many age ranges: males, females, young and old. What these finds reveal was a savannah- and open woodland- living hominin that used its sharp canine teeth to strip away the hardened coverings of stems, fruits, and vegetables to get at the goods inside. A set of preserved footprints from 3.6 million years ago has been attributed to this species and shows three afarensis: two differently-sized individuals moving side-by-side and a third that seems to have been stepping inside the tracks of the larger one in the front. Given that the footprints were preserved in volcanic ash from a nearby eruption of the Sadiman mountain, and seeing how the smaller tracks show an aberrant movement compared to its companion, it seems that these afarensis individuals were escaping the eruption, perhaps with the larger individual pulling the smaller one along. Regardless of just why and by whom the tracks were made, they reveal that Praeanthropus afarensis was walking bipedally with a fully upright stance than earlier hominins.

Emerging a little later at 3.3-1.9 million years ago was Australopithecus africanus, from southern Africa. This species was, incidentally, the earliest of the australopithecines found (in 1924), and lent valuable evidence for its describer, Raymond Dart, that the human lineage emerged in Africa and not Asia as had been the convention. Like the Lucy specimen, we’ve found many more fossils from this species. The face was slightly flatter than afarensis, and the skull was a little bulkier, indicating a shift towards even tougher plant foods than its predecessors. One fossil skull from a young 2- or 3-year old individual, dubbed the Taung Child after the town where it was found (and the fossil that Raymond Dart studied. incidentally), bears puncture marks inside its eye-sockets and around its skull. These are tell-tale signs of the work done by an eagle, predatory birds that often hunt and kill primates today.

There was one great lineage of australopithecines, the genus Paranthropus (which lived 2.73 million to 870,000 years ago), that specialized their diet towards grasses. Their jaws and teeth became enlarged and they sported a large sagittal crest on top of their skulls that supported the powerful chewing muscles needed to process these plants. Overall, their skulls were more robust than other australopithecines and given their heavily grass-based diet, they could very well have sported enormous guts – though, we lack many fossils beyond the skull to test that idea. In essence, these were grazing hominins – the horses and cattle of the australopithecines, though a more apt comparison may be with gorillas, who also sport great sagittal crests for processing tough plant foods.

Part 3

Among all of these australopithecines emerged the first members of the genus Homo, by 2.8 million years ago. What set apart Homo from the other hominins was a number of anatomical features, including a recognizable increase in brain size. In studying brain dimensions, paleoanthropologists rely on cranial capacity: the volume of space inside the brain-case. Whereas australopithecines averaged around 23-38 cubic inches, the earliest members of Homo had a cranial capacity of 34-49 cubic inches. There was also a lack of sexual dimorphism, with males and females averaging about the same height and width, as opposed to australopithecines and other apes where the sexes show great distinctions in size. For example, male Praeanthropus afarensis reached heights 50% taller than females. It is usually with this genus that paleoanthropologists and other researchers recognize these hominins as ‘humans’, and I will be referring to these ancestors of ours with that name from now on.

In time the climate continued to change. The cooling and drying of the world’s regions accelerated and reached its peak at the end of the Pliocene epoch. It is here where we enter the Quaternary Period, which began 2.58 million years ago and continues to the present day. This period has only two epochs, the first is known as the Pleistocene, and encompasses the great ice ages that we briefly discussed in the last episode.

I mentioned tool-use earlier and how many different animals use tools for everyday problem-solving. The biggest distinction between tool-use in humans and tool-use in chimpanzees and other animals is that we have the ability to actually visualize tools, not just use them. Some species, like crows and chimps, can slightly modify sticks and stems for specific purposes, like fishing for a food source. However, humans have the ability to look at any one object and “see” the desired shape they require, and then go about changing the object to suit that need. Though there is evidence of their use as far as 3.6 to 3.4 million years ago, the first stone tools found in the archaeological record date back to 3.3 MYA. This is the Lomekwian toolkit, named after the site where the remains were found. These rocks show evidence of clear knapping (shaping stone by striking it). We do not know why these tools were made, but we recognize that chimpanzees and other primates use stone tools to crack open nuts and other hard foods, so perhaps they were an extension of this strategy. In this case, the stones would have been shaped for the purpose of doing that job, as opposed to chimpanzees who search for stones of the right shape. Given their age, Lomekwian tools would have been created by australopithecines.

The next toolkit to appear in the archaeological record is the Oldowan, which dates from 2.6 to 1.7 million years ago. The name derives, yet again, from the site where they were first found, the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. This stone tool technology shows a much more varied use: cutting, scrapping, sharpening, striking. There are many sites from this period that show that these stone tools were used to help get at animal carcasses. A good, sharp cutting tool can easily tear a hide to get at the meat. It has been suggested by some anthropologists, including Agustín Fuentes, that this change in diet would only have been permitted by very good teamwork. These family groups of early humans would not have been actively hunting after the kinds of large-bodied prey that we see their Oldowan tools associated with. Analysis of the marks on the bones of these carcasses tells a different story. It seems that early humans were observing the kills of predatory mammals like lions, leopards, and hyenas, and later moving towards those mostly-skinned skeletons to scavenge the remains. This mode of behavior then seems to have shifted around 2 million years ago, when the remains of kill sites show that these humans were actively scaring away these carnivorans and then using the tools to cut away as much flesh as they can before the animals return to take back their meal. At that point, the humans would have carried their spoils to a safer place where they could consume them. This has been termed “power scavenging”, and it was one of the baby steps that led to a great revolution in human diet.

The earliest species of Homo, like Homo habilis (2.6-1.65 million years ago) and Homo rudolfensis (2.09-1.78 million years ago), were still very much like australopithecines in size and appearance, save for their markedly larger brains, lighter build, and more carnivorous diets. Early humans had very flattened faces, more so than the australopithecines, who still retained the outward projecting or prognathic jaws. However, there was a notable brow-ridge along the bottom of the forehead, which would have given these humans a distinct appearance.

Up until this point in time, humans had been confined to the African continent, but there were inklings that they were starting to spread out beyond their ancestral homeland. Around 2.1 million years ago, early members of the genus Homo were living in Asia. In the town of Dmanisi in Georgia, remains have been found of many members of our genus, dating to 1.85 million years ago. What is remarkable about these fossils is that they all have very distinct skull shapes, suggesting a wide variation in body forms for this singular population. These remains have been controversially named Homo georgicus, suggesting that all this variation was found among one species. This is not farfetched in the slightest, seeing as variation among individuals is a hallmark of species and of natural selection. Plus, there is great variation among the bones of humans around the world today, and there is no denying that they all belong to the same species. That said, many researchers who examined these fossils argued that had they been found in separate localities and dated to different times, they all would have been classifying as different species. And indeed, some studies seem to have found evidence that all the individuals at Dmanisi represent different species of humans.

This controversy stems from a much larger discussion that occurs in paleoanthropology, that being the distinction between the “lumpers” – those who look at diversity within a single species – and “splitters” – who see diversity as representing multiple, sometimes co-existing species. Beyond the often stringent arguments regarding how to know what a species is (which is another complex subject for another day), there is a bit of personal gain plaguing this discussion, as many researchers in the “splitter” category are motivated to find a new species of human and give their own name for it. The process of scientific investigation, however, has no room for personal quarrels, and it is where the evidence leads that researchers much recognize and accept. In the case of the Dmanisi fossils, some paleoanthropologists in the “lumper” category argue that the name Homo georgicus is not valid, and that these fossils belong to another, already named species called Homo erectus (which I’ll discuss in a little bit) and that this early human species simply encompassed an enormous range of anatomical diversity. At the end of the day, we currently have no real way of knowing the status of the Dmanisi fossils, and we’ll have to wait for more and better fossils to help shed light on these remains. One thing to note is that one of the skulls seems to represent an elderly individual that has lost nearly all of their teeth, and survived despite that. The most likely explanation for this was that they were being fed and cared for by other members of the group. This is evidence of a form of compassion that is not seen in any other living primate species.

Despite this, the Georgian fossils are most important in that they reveal that humans were expanding their ranges outside Africa and settling in new environments. Recent comparative anatomical studies have revealed that some of these members of the early Homo group made it as far as southeast Asia. On the island of Flores, today belonging to Indonesia, there are several fossils and stone tools that reveal that groups of humans became isolated on the island before 700,000 years ago. This was Homo floresiensis, who only grew as tall as 3.7 feet and weighed 55 pounds as adults. This implies that these humans experienced island dwarfism: this is an evolutionary phenomenon where species of animals become isolated on islands and gradually adapt their bodies towards a much reduced size. This means that they do not require as much food to eat and therefore there is no self-imposed threat to resources. Other animal fossils on Flores show island dwarfism too, with the native elephants standing several feet shorter than their mainland relatives. Also in play was island gigantism, where island animals gain a larger body size in response to an abundance of resources. This means that Homo floresiensis shared its island with enormous storks that stood almost 6 feet tall and giant rats some 45 inches long from snout to tail.

Homo floresiensis made stone tools that resemble the Oldowan technology, and researchers have looked at the microwear or microscopic markings on the stones and revealed that these little humans hunted after small animals and cut up woody-stemmed plants. They seem to have refuged in caves, safe from the dangerous animals that lived in the rainforests, including Komodo dragons that would have easily made a meal of one of these people. Homo floresiensis was not a particularly good runner, as evidenced by the shortened and broad legs of their skeletons. This species would had to have remained close together during hunting, certainly keeping watch of any dangers and working together to escape threats. Homo floresiensis seems to have survived on the island of Flores until around 60-50,000 years ago.

Part 4

Later members of the genus Homo increased in overall height and brain-size, reaching as high as 6 feet and sporting a cranial capacity of between 37 and 79 cubic inches. Throughout these species, there is evidence of much more complex forms of behavior and the emergence of elemental cultures. Evolving in Africa 2.27 million years ago was Homo ergaster, which ranged throughout the continent. Populations of this human moved out of Africa in another great wave of expansion, and followed along the similar paths that the earlier Homo species took and reached China and southeast Asia. It was these non-African groups that gave rise to Homo erectus around 1.85 million years ago; the famous Java Man and Peking Man fossils belong to that species. Some paleoanthropologists who advocate “lumping” see Homo ergaster as belonging to the species Homo erectus. In any case, large and slender bodied humans, with lengthy limbs and even lengthier legs had evolved. They still had large brow-ridges, but started to look very much like our own species.

For one, the shape and length of their legs indicated that these humans were specialized for long-distance walking and running. In Homo ergaster and Homo erectus do we see the development of the modern foot, with all toes connected and compacted into one pad. Without a big, outward-facing toe to get in the way, the body could be better balanced on two feet. Longer legs enabled these humans to make longer strides, furthering energy-saving. Coupled with this, we also have genetic evidence that suggests that by around 1.2 million years ago, the fur on the body reduced significantly, the skin became darker, and sweat glands began to form across the body. This package of trait-changes had large benefits. A lack of thick fur and subsequent exposure of (almost) nude skin allows the body to cool better under the hot sun. Having sweat glands all over the body further aids in this process (sweat glands remove heat through evaporation). Dark-pigmented skin – a trait found among all humans in tropical climates – acts as a thermoregulatory tool, blocking ultraviolet radiation from entering the body (restricting hair to the head also helps with this). There are clear environmental reasons for all these new traits, but why the need to run?

Besides the obvious need to escape fast-moving predators, Homo ergaster and Homo erectus appears to have been running after its food. They were no longer power-scavenging, but actively hunting with weapons. Archaeologists have associated these humans with the Acheulian stone toolkit (1.76 million to 200,000 years ago). This toolkit is much larger than the older Oldowan tools: new additions include large handaxes, made by knapping a stone along all sides until the desired shape emerges. The symmetric shape of these tools reveals a possible capacity for aesthetic appreciation, an extension of the metal capabilities that allowed the earliest hominins to picture finished tools before they constructed them. Much speculation has emerged as to what these stone axes were actually used for, and indeed, more have been found than would possibly have been used, but they at least appear to be multipurpose. If anything, the toolkit as-a-whole included implements for killing and cutting up prey animals, including the earliest known evidence for spears. Evidence shows that large mammals make up part of the diet of Homo erectus. While many such mammals, like antelope, horses, and deer, are clearly faster, humans can actually match their total distance per day. There is a difference between sprinting and endurance running. A prey animal will run with all its might from a predator, in this case Homo erectus, but after a while it will need to rest. With endurance running, a human can keep the same pace because it is not putting all its energy into moving. It may be significantly slower, but given enough time, it will still manage to catch up to an animal that will have eventually collapsed from heat exhaustion, allowing for the kill via the thrust of a spear. Some modern forager peoples still hunt in this way, so we have been able to compare their lives with those of early humans that faced similar environmental pressures. Comparing the lives of modern peoples with those of the past is tricky: keep in mind that though these studies provide valuable insights, they are not direct evidence of prehistoric behaviors. Forager groups are people of the present day, not the past.

Homo erectus may have also been one of the first hominins to utilize fire, but there is much controversy in this field of study. For one, we know that living apes (particularly chimpanzees) recognize and do not fear wildfires, seeing them as a means of obtaining food: they will follow the movement of a fire and go after the burnt animals and plants. Secondly, there is a big different between recognizing what fire is, following wildfires, borrowing fire, and making it. Even though the earliest sites for hominin use-of-fire go back at least 1.6 million years ago (associated with Homo erectus), there is nothing to suggest that earlier species did not use fire in some way. It seems more likely that the use and eventual learning of how to make fire was a gradual process. The ability to cook food is certainly a very helpful strategy. Simple observations have shown that cooking helps soften and decontaminate food, as well as increase a food’s vital nutrients – it is essentially pre-digestion. Perhaps cooking helped foster new changes in both physiology and psychology. For example, we have discovered that Homo erectus and related forms around this time had developed key structures of the brain called frontal opercula associated with motor processing and more complex social behaviors. There was, thus, more to the increase in brain-size than meets the eye.

And what about speech? When did humans begin talking to each other with languages? This is a very controversial topic and there is no consensus as to the evolution of speech and language, so let’s just take a look at what we know and see where the evidence could lead us. Communication – the exchange of information with others – clearly extends back into our primate heritage. Language – the symbolic code that facilitates communication, verbally or non-verbally – is a bit trickier to pinpoint. It has been argued by many researchers that several organisms, including dolphins, have languages, but there is a lack of concrete evidence for this. What does neuropsychology have to say? There are key areas of the brain that aid with the facilitation of speech and language, like Broca’s Area (which controls the regions of the mouth, throat, and lungs that produce speech) and Wernicke’s Area (which deals with speech comprehension). Physiologically, the low position of our larynx has allowed humans to produce a wider range of sounds than other primates can. So all we’d have to do is look at what fossil remains we have for early humans and see when these important features show up. As far as brain casts are concerned, we see a human-like Broca’s & Wernicke’s Area in Homo habilis & Homo erectus, as opposed to the more ancestral brains of australopithecines. Interestingly, the shape of the base of the skulls in mammals shows a correlation to larynx position. What we find is that a low-oriented larynx shows up in Homo erectus, but it isn’t until around 300,000 years ago that we see the right curvature in the base of the skull, suggesting that a larynx that allows a fully-fledged suite of symbolic speech had appeared. This corresponds with the earliest Homo sapiens and their kin. That’s about the best we can do for now: explanations for the evolution of these traits are, at best, informed speculation. We can be confident, however, that when clear evidence of symbolism, including expressions of culture, appear in the archaeological record, we know that early humans must be communicating with each other using languages of a type that we’ll never hear.

All of this new information would have dramatically changed the family-group dynamic of early humans. Learning how to knap and shape stone tools would have been information that was shared and passed down generation by generation. This collective learning, as it is called, would have been facilitated by experienced individuals who understood the intricacies of making the proper stone tools. Young children could have been directly taught by these teachers, or simply observed them and tried it out themselves. Among other primates today, like chimpanzees, the young are often close-by watching their parents or other members of the group when they gather and use tools, learning for themselves how to undertake the task. And over time, new ways of making the tools can arise from these individuals, adding much needed improvements and revisions, and these can be taken up by the rest of the community.

Another key change was in the way that the young were raised. Based on the analysis of the best pelvic bones we have for hominins, anthropologist Robert Martin has argued that childbirth would have become very difficult by the time of Homo ergaster. This would have been due to the gradual transition towards bipedality (which altered the shape of hominin pelvises) and the expansion of the size of the brain which meant that mothers faced extreme pain and pressure trying to pass their infants through the vagina. If left alone, there was a strong possibility of death by childbirth, which is why Robert Martin has proposed that the practice of midwifing – assisting a mother in labor – would have to have been in practice at this time. There is also evidence of a shift in childhood among later Homo species, with the length of time for development growing. This meant that, for at most the first 5 years of life, young humans would have been staying by their mother’s side for much longer, nursing and bonding until they were of the age to assist with other members of their family group. Like other primates, there would have been many members of these family groups assisting in the care of the infants, allowing the mothers to participate in hunts, tool-making, and other problem-solving activities.

All of these shared experiences, of working together to survive the odds, of bringing up the next generation, and of assuring that their children have all the skills they need to function in their communities, are all hallmarks of humanity. It is perhaps reassuring that it is these most basic and most precious of human social behaviors that have been around for millions of years.

And with that, we must lay anchor to our river journey. In the next episode, the story of human evolution continues. We visit a world caught in the grips of the ice ages and various human species struggle to survive the extreme shifts of temperatures as they expand across Africa and Eurasia. We meet two of our closest human relatives, the neanderthals and denisovans, and see what sorts of cultures they created, hundreds of thousands of years ago.

That’s the end of this episode of On the River of History. If you enjoyed listening in and are interested in hearing more, you can visit my new website at www.podcasts.com, just search for ‘On the River of History’. This podcast is also available on iTunes, just search for it by name. A transcript of today’s episode is available for the hearing-impaired or for those who just want to read along: the link is in the description. And, if you like what I do, you’re welcome to stop by my Twitter @KilldeerCheer. You can also support this podcast by becoming a patron, at www.patreon.com/JTurmelle: any and all donations are greatly appreciated and will help continue this podcast. Thank you all for listening and never forget: the story of the world is your story too.

0 notes

Text

Murchison Falls National Park Safari- Wildlife, Adventure and Comfort

Murchison Falls Park is Uganda's biggest national park. It is a habitat of an assortment of animals and birds. The world’s longest river Nile divides the park into two halves and makes it have both the northern and the southern part. The National Park gets its name from the mighty fall of the river Nile that powers its self into a limited gorge down the base. It is a fantastic view to have a look at the waterfalls. The southern part of the national park is a forest region and northern side is a savannah territory. The topography of the area along with the bio-diversity present makes it the best place to have a safari when in Uganda. Murchison Falls National Park Safari gives you opportunities to explore the wilderness and have adventure with excitement. On the other hand, the comfortable and luxurious lodges offer you the perfect means to have a comfortable stay. The adventure, activities and comfort that you can experience at Murchison Falls National Park are detailed below.

Chimp trekking

Budongo Forestis situated on the southern side of Murchinson Falls National Park. Budongo Forest is an amazingly charming place, due to having most differed flora and faunas in the entire East Africa. The 790 square kilometer forest has over 465 plant species, more than 250 butterfly species, an extensive variety of warm-blooded creatures, including a significant populace of chimpanzees in Uganda. Other known primates are red-tailed monkeys, black and white colobus, blue monkey, potto and various forest galago species. Budongo Forest is also a favorite spot for birders as it offers the opportunity to view more than 366 bird species, including 60 West or Central African birds that stay in less than 5 areas in East Africa.

Chimpanzee trekking happens in the Kaniyo Pabidi area. Chimp habituation began formally in 1992. Guided chimp trekking leaves at 8.00 AM and 3.00 PM; The guides are amazingly obliging and adaptable. The achievement of locating the chimps is high, even though it depends enormously on the fruiting seasons, with improved probability of good viewings of the chimps between the long periods of May and August. The landscape experienced amid the trek through the woods as you look for the chimpanzees is genuinely extreme through some precarious and long slopes. Nevertheless, the excellence of the forest overwhelms you totally, as you stroll along the well-maintained ways listening to the tremendous assortment of bird songs and creature calls. The educational guided walk gives you the historical backdrop of the forest and helps you to appreciate the rich and widely varied vegetation.

Game Drives

Murchison Falls National Park is the best game park in Uganda with regards to game drives. On a regular game drive, you can see a substantial number of antelope species, including the Bush buck, the water buck, Thomson's gazelle and the dik-dik to give some examples. Bigger herbivores, for example, giraffes and elephants are available in the park in extraordinary numbers and frequently the animals cross the tracks directly before you. It is the most open savannah park in Uganda to see the giraffe.

Colossal gatherings of buffalos are a typical sight while exploring the park on a game drive. Primates for example, the patas monkey, gaze at you as you go by. On the off chance that you are a birder, Murchison Falls National Park will not disappoint you. Murchison is the best park in Uganda to see the enormous cats, yes; you can spot the lions and leopards with ease.

Boat trip

The boat trip upstream the river Nile to the base of the falls is one of the best experiences to have. Cruising up and down the Nile gives an incredible chance to watch the animals as they come down to the water's edge to drink. The Nile bolsters the biggest concentration of hippos and crocodiles in Africa and an amazing variety of water birds. The perspectives of the falls as you approach by boat are terrific. The Nile has white water rapids and afterwards at the falls it drops 40m over the remaining cliff at Murchison falls. The boat trip lasts around 3 hours.

Way to the top of the falls

A short drive on a winding road takes you to the highest point of the falls. Here, you can hear and see the thunder and feel the splash as the water constrains itself through the rocky gorge. Views from the highest point of the falls are amazing and offer a magnificent photography platform.

So, you would love to have a Murchison Falls National Park Safari. After a tour for the entire day, you wish for a comfortable place to rest. Murchison Falls National Park does not disappoint you in this respect too. There are various luxurious and clean comfortable lodges where you can stay during a safari. Let us have a look at some of those lodges.

Bakers Lodge: This lodge is on the south bank of the River Nile that transects Murchison Falls National Park. The location of this lodge is such that from your room or verandah you can have a complete view of the river and the surrounding wetland, which is the home of many bird species. Along these lines for those searching for a lovely time in Murchison Falls National Park, this lodge is the best. Bakers Lodge has 10 en-suit cottages for the guests that are fun cooled and they are loaded with locally designed and developed decor. You will appreciate the supper along the Nile and a bush breakfast while seeing untamed animals and birds in this park.

Paraa safari lodge: Paraa safari lodge offers the solace, relaxation and excitement with rooms that have a view of the Nile. The second floor rooms give the best view where you can spot wildlife and birds directly from your room. It has overwhelming luxury bungalows, which you can pick as well. The lodge has diverse rooms, for example, standard rooms, luxurious suites, and exclusive cottages that are nearer to the River Nile. This is additionally the oldest and one of most esteemed luxury lodge in Murchison Falls National Park.

Chobe Lodge: The Chobe safari lodge is a top of the line accommodation and is a jewel inside Murchison Falls National Park. A stay in this lodge rewards you with amazing sights and sounds of the splendid rapids of River Nile. The views from your room will amaze and add adventure as you watch the beautiful scenery and wilderness. This lodge has fantastic and impressive rooms and furniture. It goes past creative energies and surpasses desires. This hotel gives the ideal chance to experience natural life, birds, vegetation. So on the off chance that you cherish angling this is the best accommodation for you to remain while on a safari in Uganda. This lodge is the best and one of the splendidly located luxurious lodge in Murchison Falls National Park.

Nile safari lodge: The Nile safari lodge is in the southern banks of Murchison Falls and surrounded by papyrus forest. The lodge has lovely wooden chalets and extravagant tents. They are in an ideal spot to give you eminent perspective of the national park and the African wilderness. The stay in this lodge will make you experience the excellence of Africa. The lodge has 10 spacious rooms, 5 wooden chalets and luxurious tents with luxurious washrooms, air conditioners and balconies that will give you an unimaginable view. Nile safari lodge has amazing facilities, for example, full loaded bar and multi cuisine eatery. It has campfire at night making possible for you to have the pleasure of watching the African night sky, local dance and music.

You definitely desire to have such adventurous and exciting experiences while having perfect comfort and relaxation during your visit to Murchison Falls National Park. The best way to have such a time is to book the Murchison Falls National Park Safari with Redrock African safaris --- a Uganda registered tour operator based in Kampala. They have been organizing such safaris for years and so you can expect to have the best of safari experience along with your stay at the best accommodation. Do contact dialing +256 392 842 045 or mailing at [email protected] and book one of the tours.

For more details, Please stay in touch with us through facebook, twitter, Instagram and tripadvisor social networks.

#Uganda Safari Tour Operators#Uganda Rwanda Tour#Birding Safaris in Uganda#Gorilla Tours Bwindi#Uganda Fishing Tours

0 notes

Text

Why You’ll Want to Visit Magashi – Soon

New Post has been published on https://tagasafarisafrica.com/why-youll-want-to-visit-magashi-soon/

Why You’ll Want to Visit Magashi – Soon

Rwanda GM Ingrid Baas updates us on the latest news from Magashi – we have just four months left till the camp opens!

2019 is Magashi’s year, with the first few months of the year focused on finalising work on the camp construction, staff recruitment and staff training, as well as working on our menu and guest experience – this is not including all the finer details involved in our day-to-day proceedings!

We started the year with the most wonderful news… we had suspected that the Amahoro lioness was hiding cubs and this was confirmed when she revealed them to senior guides Hein and Adriaan in early January. Besides lion sightings, we are thrilled to say that Magashi is looking like a leopard haven with many new leopard identities confirmed – our guides even enjoyed a sighting of these three leopards on their evening game drive.

The construction team has returned after a well-deserved Christmas break. With the team back on site, building is moving along swiftly. We cannot wait to see what the camp will look like when all the structures are in place.

In May 2019 we are expecting our first guests… We are very excited to share this beautiful new Wilderness Safaris camp with all our visitors, and indeed, the rest of the world!

Building progress

The construction of Magashi is moving along swiftly and the team is making fantastic progress. This means that the pictures below are already outdated! All six guest tents and the two tents for private guides have been erected, and the wooden floors and headboards are finished. The team is currently busy with bathroom tiling and the installation of basins and showers. The main area deck and the boardwalks connecting all the guest rooms to the main area are almost complete. The main area tent is up and the team is now working on the main area interiors.

Besides the guest recreation areas, the construction team is also working on the staff village and kitchen, as well as the laundry, office and workshop.

All the interiors have arrived on site and are being stored in containers for safe-keeping. It will soon be time to start unpacking the containers and our next role will be placing the furniture and décor items.

Our visitors have all noted how beautiful the site is – with special mentions being made of the trees that surround the tents and main area, the way in which the boardwalks are integrated into the natural surroundings and, of course, the absolutely breathtaking views.

Creating the camp staff team

After going through hundreds of applications and conducting many interviews, a strong team has been established. Many of the team members, like head chef Eric, Aline and Rachel in housekeeping, chef Samuel and barman Elie, have had the opportunity to train at Bisate. This team started working in May 2018, which will mean that by the time Magashi opens, they will already have had a year of experience working with Wilderness Safaris!

Other team members started with us when we opened Bisate in 2017. They are ready for the next step in their Wilderness career and are moving to Magashi.

Anita started in March 2017 as the assistant manager at Bisate, and is ready for her next challenge as manager of Magashi. Innocent, a waiter at Bisate since April 2017, always wanted to work in the bush and would love to be trained as a safari guide. Together we decided that it would be a great opportunity for Innocent to work as a waiter at Magashi, but at the same time learn as much as he possibly can from Adriaan and Hein, our senior guides. David, who worked at Bisate in the security team, has been studying food preparation in his free time. During his annual leave he volunteered for an internship in the Bisate kitchen! Because of his enthusiasm and dedication we believe that he deserves a place in the Magashi kitchen team.

The guiding team is strong with Hein and Adriaan in charge, and trackers Dorence and Trevor. They have been at Magashi since November 2018, exploring the area and very successfully habituating different species of animals. See the wildlife sightings below for proof of their work! Recently we recruited Alphonse as a junior guide to join the team. Alphonse has worked as a community freelance guide for Akagera National Park for the last five years. He grew up just outside the National Park and started his guiding career with African Parks. He is very excited to take his guiding knowledge and experience to the next level, and work full time for Magashi.

Of course I cannot mention all the Magashi staff members in this blog post, but I can promise that all of them are more than ready, and super excited.

Vehicles and boats

The Magashi vehicles are ready and we are very happy with the end result! Rob went to Tanzania several times, where the conversion to open game-drive vehicles was completed. Soon the vehicles will be transported from Tanzania to Rwanda. Once in Rwanda we will brand the vehicles with the Wilderness Safaris logo and thereafter, they will be ready for our guests! The three Toyota Hilux 4x4s are very comfortable and can accommodate seven guests, allowing each guest an outside seat. The vehicles have USB charging facilities, a fridge to keep sundowner drinks nice and cold, blue LED lights on the floor when needed for night drives, and support structures to stabilise lenses, enhancing our guests’ wildlife photography experience.

Magashi’s two eight-seater boats, the swamp cruisers, are also already. The boats come with swivel seats, allowing guests to easily turn to their preferred position. Like the vehicles, the boats have a USB charging facility, and there is even the option to sit on the roof of the boat, allowing for elevated views of the river bank and papyrus.

Sightings – leopard madness

Where to start? Magashi has surprised us all… although we knew that the area was beautiful, and game would be plentiful, we did not expect the daily sightings of herbivores and predators to be this good, or the drives to be this spectacular!

The guides and trackers have identified nine different leopards in the private Magashi area, mostly in the south of the concession very close to Magashi. The Amahoro Pride, consisting of three females, three males and two cubs, seems to prefer venturing into the north.

The guiding team has also created additional game drive loops on the concession, creating access to areas that were previously unexplored.

All the game, including leopards and lions, are getting accustomed to the vehicles, and are very relaxed on sightings. One of the younger males was even spotted sniffing the vehicle and tyres on one of the evening game drives.

We recently took some guests on a few game drives on the concession, and they had good sightings of several leopards, lion, hyaena, elephant, warthog, oribi, Defassa waterbuck, hippo, buffalo, blotched genet, Senegal galago, gerbil, eland, hundreds of impala, topi, plains zebra, giraffe, crocodiles and more.

The birdlife has been amazing too, providing wonderful photo opportunities, especially from the boat on Lake Rwanyakazinga.

Akagera Management Company

Wilderness Safaris is developing Magashi in partnership with the Rwanda Development Board and conservation group African Parks, but which would not have been possible without the support of the Howard G. Buffett Foundation for African Parks.

African Parks is a non-profit conservation organisation that takes on the complete responsibility for the rehabilitation and long-term management of national parks in partnership with governments and local communities.

In 2010, the Rwanda Development Board and African Parks joined to create the Akagera Management Company (AMC). This joint company assumed management of Akagera National Park in 2010, with the aim to restore, develop and manage Akagera National Park as a functioning savannah ecosystem, through biodiversity rehabilitation, sound conservation practices and tourism development. In the past eight years significant steps have been made towards achieving this goal.

Initially the focus for the project was on developing the foundations for effective and efficient management of the park. Investments and improvements were made on infrastructural developments, including a fully functioning workshop and storage facility, new and renovated offices, vehicles and machinery, a law enforcement block, staff housing and renovations to all existing facilities.

Law enforcement and the protection of the park was a priority from the beginning. New rangers were employed, with the total number of law enforcement staff now at over 80. The changes among the law enforcement team has, and continues to, yield positive results. 2014 was a major turning point, with a dramatic reduction across all illegal activities and continued increase in patrols. The law enforcement team has been working with a canine unit and the latest technology and software since 2015.

The communities surrounding Akagera are vital to the success of the park, and they experience tangible benefits from the park’s existence. Local employment is one of the major direct benefits, with over 250 people employed by the park full time. Akagera also contributes to the national revenue sharing scheme, and on-going community sensitisation programmes are conducted. Alongside this, environmental education among local schools is seen as vital in creating support from the local community and ensuring the long-term survival of the park.

Lion have been extinct in Akagera for almost 15 years, and their return in June 2015 was a conservation milestone celebrated far and wide. Before their reintroduction, the last rhino sighting in Akagera was in 2007. Ten years later, in May 2017, Eastern black rhinos were translocated to the park.

Akagera is well on its way to becoming self-sustaining, and a valuable contributor to the tourism industry and the economy of Rwanda as a premier tourism destination and conservation success story.

We believe that Magashi will contribute to this success and we are privileged to have the opportunity to use our model of responsible ecotourism to further conservation and community empowerment in Akagera National Park.

Post courtesy of Wilderness Safaris

0 notes

Text

Udzungwa Mountains National Park

Udzungwa Mountains national Park is cover an area of about 2,000 sq km, It lies in Iringa and Morogoro regions of south central Tanzania where it is bordered by the Great Ruaha River to the north and the Mikumi Ifakara road to the east. The park major attractions are its bio diversity and unique rainforest where many rare plants, not found anywhere else in the world, have been here identified including a tiny African violet to 30 meter high trees. The park is home to eleven types of primate. Five of these are unique to udzungwa, including the endangered Iringa red colobus monkey and the Sanje crested mangabey. The plateau also supports populations of elephant, buffalo, lion and leopard. Visitors should not expect to necessarily see these larger species however as they tend to be found in the less accessible area of the park. Bush baby or as they are sometimes called Galago, bush pig, civet, duiker, honey badger and three types of mongoose are more likely to be seen. The park which is about 65 km, or a two hour drive, south west of Mikumi National Park, is also home to a number of rare forest birds many of which are only found in this area of Tanzania Read the full article

0 notes

Text

POTIONS | October 6th | Lesson #15 | African Potions

Western Witches and Wizards, particularly the maheka-lala, or the Curse-Breakers of Gringotts are still seeking the true nature of Egyptian Magic, or heka. In fact, the Magical communities of Egypt now have no recollection of this heritage of powerful and advanced magic either, and the magic practiced there now can best be characterized as Western in nature.

However, one of the ingredients endemic to Potions in Northern Africa, particularly those brewed in Morocco, contains flowers and essential oils from the argan tree, a species of tree in the Sous valley in southwestern Morocco. The flowers of the argan tree are used in beautifying creams as well as slimming and thinning potions. The oil, meanwhile, has widespread use in North African Potioneering, being utilized not only in different beautifying potions, but also love and lust potions, and certain healing potions, particularly those that cure digestive issues, ulcers, and other stomach problems.

There are a few species native to North Africa that are still used in region-specific potions. The first of these is the Fat-Tailed Scorpion, of the genus Androctonus, whose etymological root comes from the Greek for “man-killer.” The tail of this scorpion is used in certain strong antidotes to poison, and can also be used in powerful anti-venoms. The claws meanwhile can be used in potions that increase an individual’s stealth and cunning.

The Egyptian Cobra is another popular ingredient - as well as occasional Witch or Wizard pet - in North Africa. Despite its common name, this snake can be found across most of North Africa and parts of the Middle East, as well as across the savannas of West Africa, and even parts of East Africa. The blood of this snake is a very powerful ingredient, and it is thought that the skin of the hood of the Egyptian Cobra may be one of the important ingredients in the mysterious Drink of Despair, occasionally known as the Emerald Potion. The use of the hood of this cobra is illegal in most parts of the Magical world.

A very important animal that, while it can be found elsewhere in the world, originally came from Egypt is the phoenix. The feathers of the phoenix will be well known to students in Great Britain, as it is one of the three cores that the Ollivander family uses exclusively in their wands. While phoenix tears are on their own magical curatives, these tears can also be used in very powerful curing potions. Phoenix tears are exceedingly rare and difficult to track down by legal and ethical means, so these potions are not often used.

One relatively unique aspect of North African Potioneering that is seen, though to a lesser extent, in Central and Eastern African regions is the use of chips of metallic and stone elements in Potioneering, often heavily utilizing the substances alchemic principles. For instance, there is an incredibly power love potion that was invented in the sixteenth century in Morocco that utilizes not only dates from the date palm and two spines from the crested porcupine, but also incorporates shavings of copper as one of its major ingredients.

Traditionally, Witches and Wizards of Southern Africa took the role of shaman, priest, healer, and occasionally even leadership positions within their communities, mostly of the San, Bantu, and Khoikhoi people, although those of the Zulu nation arrived a little later in the region’s history. Potions were not quite as commonly used as healing energies, healing charms, and even runic enchantments. However, traditional plants native to Southern Africa were used in potions primarily brewed for healing, protection and strength, and dreams. For example, the leaves of a plant native to South Africa known as Uzara are used in antidotes to uncommon poisons. Meanwhile, the roots of the plant Silene pilosellifolia are used in several Draughts of Vivid Dreaming.

One of the most powerful protective potions known to Wizardkind is, in fact, a highly complicated and time-sensitive concoction that comes from Southern Africa composed of the blood of a Blackhead Persian sheep, the eyes of a galago (more commonly called a bushbaby), and charred wood chips from an African date tree. This potion, while it will not defend the taker from all harm or disease, will make them resistant to many forms of dark magic and assault. Few have managed to brew this protective potion successfully, and none off the continent of Africa, interestingly. Galago eyes are also used in other protective potions, which, while they are not quite as efficacious as the Staalhart Serum, are still quite handy, and can be brewed in Europe and Great Britain.