#so many words throughout history written and unwritten

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I fucking loveeeeee languages and linguistics. Nothing more human than creating a language

#Apparently there’s ~7000 languages in the world currently#Though I’m not sure how that figure was reached#or what distinguishes a language from a dialect#how distinct do they need to be#what is the process for creating languages that do not have a spoken format (e.g sign language or braille)#linguists must be having simultaneously the best and worst time ever always man#so many words throughout history written and unwritten#Remnants of languages we may never know in any way other than writing we cannot decipher#also like how would sign language be recorded#who created the first signs what society did the way live in#language is so tied to our identity and existence as people#communication does not always need language but language was created to communicate#linguistics#language#filled with love for people again#And wonder at our world

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Hope the stories are cool.”

At the half-murmured words, Ben turned to their source in the passenger seat beside him, brow furrowed. “What was that?”

Riley, staring out the window of Patrick’s weird-smelling car at the night around them, seemed surprised at the question. “Hm?” When he looked at Ben, however, it was clear he hadn't realized he'd said anything aloud until that moment. “Oh! Uh—" He shrugged it off with a nonchalant grin, turning away again. “Uh, nothing. Sorry.”

Oh, you’re not getting off that easy, Ben thought. “What’d you say? What stories?”

Riley rolled his eyes. “Ben—”

“No, no,” he interrupted, before a snide remark could be made, “I heard ‘stories’ and ‘cool’. Now, what cool stories were you talking about?”

Riley gave him perhaps half of a death glare, and for a moment, Ben thought he was going to ignore the question. But then he sulked back against his seat, and seemed to give in. “Well—” He scoffed, eyes on the ceiling. “Ours, I guess. I mean, we just stole the Declaration of Independence, Ben! The Declara—do you have any idea what this means?”

Ben frowned: maybe he was avoiding the question after all. “Yes, I think you've given me several ideas of the things this could possibly mean.” Besides, I thought you’d be worried out at this time of night, he added mentally.

“Yeah, but I'm not talking about going to prison, and Ian shooting us, and Abigail doing a lot more than slapping and shouting if we screw it up. She’ll probably… I dunno, impale us with those pointy heels or something.” He picked up an old neck pillow (he’d knocked it off the seat when he first climbed up front), and put it in his lap. “You know, maybe that’s why the spy chicks in the movies wear them all the time—if you can get used to running around and doing all those acrobatics in them, they can double as a lethal weapon.”

“Well, what are you talking about, then?” Ben pressed before the conversation could get too far off base: Riley could easily and resourcefully use the smallest sidetrack to avoid a topic he didn’t want to talk about. Kid was practically an escape artist.

“I’m talking about America. They're not gonna let us off with a simple little life sentence. They're gonna have us pegged even after we're dead.”

Ben bit back a comment about him watching too many ghost hunter shows, opting for the simpler, “How do you mean?”

Riley turned to fix blue eyes firmly on Ben; eyes that, to his surprise, he now saw were grounded in a gravity greater than worry. “Ben… whether we win or not, we’re gonna be locked up for basically the rest of time. Why?”

He leaned in closer, and spoke with such certainty, Ben had to suppress a shiver.

“Because we’re going to be in all the American history books for basically the rest of time. Do you understand that, Mr. History Buff? Kids are gonna be learning our names in the future. Your name, my name, maybe even her name—and unless something crazy happens, like really crazy, then…” He sighed, and plopped back against the seat. “Then even if we keep the Declaration away from Ian, we're gonna be the ones they remember stealing it.” He looked back up. “You know that, Ben?”

It took a moment for Ben to find the voice to reply. When he did, he let it out with a breath he didn’t know he’d been holding, blinking a few times. “Huh, yeah.” He sat back, stunned, as the full weight of it befell him. “Yeah...” he whispered again.

The fact was, he had thought of it. From the moment he determined to undertake the task, he’d been aware of it. But throughout their escapades and machinations, he had kept it as just that—a fact—an awareness at the back of his mind. He hadn’t thought about it. Not until that moment, in an empty parking lot in the middle of the night. Not until Riley decided to be seriously, deeply right.

And… he wanted to tell him that. He wanted to tell Riley just how dead-center his aim had been. He wanted to confess to him the sudden fear it had struck in his heart. But somehow, he couldn’t. What somehow it was, he didn’t know. But it kept his voice from him.

He started to tell himself he just didn’t want to worry him further, especially with the way things were now, but he knew that wasn’t it. Riley was the one who started this particular concern anyway. It wasn’t a matter of trust, either. This was his best friend—Riley knew things about him even his father didn’t know, and Ben would have willingly put his life in his hands. There were times when he’d had to. And there were times that Riley’s life had been in his hands, his alone, and they both knew it. And for all he knew, that could’ve been what stopped him from saying those words.

You’re dead right. We’ll never be forgotten. And it terrifies me.

Ben’s highest hope, even beyond the actual finding of the treasure, had always been to become a part of history. Just like his ancestors. Just like the Founders. Just like the men who had been his heroes since he was a boy. And throughout his adventure, there had been many times when he had thought to himself, you’re continuing that story. This is the same old tale Grandpa told you, but it’s not over. It’s going on, in this exact minute, and you’re the one carrying it now.

The thought had given him purpose, over all those years. But now, he could not help but wonder what his part in that history would be. Would he be a hero, like those men of history, the knights (official or not) that he had always looked up to? Or would he be the one to bring it all down when he failed?

But, whatever the reason, he couldn’t say all that to Riley. He couldn’t say anything at the moment. So the moment was filled with silence instead, a weighty, waiting silence, on the precipice of what tomorrow might bring. The burden of history, both written and as yet unwritten, was for him in that moment almost physical.

“That wasn’t the story I was talking about when you heard me, though.”

The breaking of the silence almost startled him. Ben glanced up at Riley, confused and close to bewildered. For a moment, all he could manage was, “Then… what—what were you…?”

Riley also looked up, and seemed to notice something strange in his hushed tone. “Oh. Sorry.” What was there to apologize for? “It’s just, I accidentally had, like, a lot of thoughts, while you and Abigail were talking. That stuff was part of it, but it wasn’t the main thing.”

He fell silent a moment, but Ben gestured him on, almost insistently. If there was more, even if it was worse, he felt he had to hear it. What could Riley have possibly meant?

Riley hesitated, then looked down and began fidgeting with a loose string on the neck pillow in his lap. “You were telling her the story. About the treasure, and how you got all that history from your grandpa.”

Ben’s ears perked up: anybody talking about his grandfather got his full attention.

“And I got thinking about it, and I just…” He shrugged. “I wondered about, y’know, what if that’s us someday? What if… what if we’re the ones some cool old guy tells his grandkids about? I mean, I know he still might think it’s bad, but at least grandpas and textbooks don’t really tell stories the same way. I assume,” he added, with a glance at Ben for confirmation.

To his own surprise, Ben felt a smile tugging at his lips. Something in that homier view of history—despite the continued possibility of failure—put him more at ease, as if he were still listening to old yarns at his grandfather’s house, slowly losing the fear of the storms outside. The cloud of heaviness that had been on him began to dissipate. Even the night around them seemed less dark.

Ben breathed a chuckle. “No, you’re right. They really don’t.”

“Yeah, so he’d be telling like a grandpa, not like some bored guy in Milwaukee having to crank out school material! Right? And then, like, he says,” and at this, Riley briefly put on the persona of an old man, complete with motions and raspy grandpa voice, “‘Come here, m’boy, let me tell you the story of the Templar Treasure,’ and the kids go huddle up in front of him with those ginormous eyes little kids always have, because apparently the smaller you are the bigger your eyes look, and he tells ‘em the whole thing, right up to where your grandpa told it, and then—and then he tells about us.”

There was a noticeable pause, as if it even took a little of Riley’s breath away. He smiled softly, almost in awe himself. “He tells about us.”

A few seconds passed before he noticed the gap of words, which he immediately jumped over to continue his own tale. “And—and maybe there’ll be this one kid who actually thinks about it and is like, ‘man, this Ben guy was nuts! He just goes, oh let’s steal the Declaration of Independence, and expects everybody to be totally fine with it? How could anybody deal with such a crazy guy?’ And the grandpa would be like, ‘Well, shucks, I always knew you were a smart kid.’”

At this, Ben laughed. Really laughed, clear and from the heart. How in the world could Riley complain and fret about their plans so heavily, and yet paint the future with such lightness that you could laugh at it? All the time he’d known this kid, and he still couldn’t quite understand him. But he didn’t mind. And, for the moment, there seemed nothing to fear. The weight was gone.

But Riley wasn’t finished. “Oh, but you know he'd still get pulled into it, the same way your grandpa pulled you in—the same way you pulled me in—and end up thinking it's the coolest thing ever, of course. I mean, who wouldn't, if they tell it like a Gates tells it? You guys don't skimp on the history stuff, especially family history. That’s what bought my ticket for this whole… train of thought... thing... in the first place, you and Abigail and all your history nerd talk the whole way here.”

Ben reeled back, taking false offense. “Oh, nerd talk, is it?”

“One hundred percent, man, and don’t you forget it. And it’ll still be nerd stuff when you’re the subject boring another average guy like me to sleep in the back of the car.” Riley threw his hands in the air with an air of finality. “And, who knows? Maybe one of those cute little grandkids gets all inspired the same way you did, and wants to go find a treasure and fight bad guys and figure all kind of crazy puzzles, and, heck, probably decides to go be a knight and stuff, just like u—”

He bit his lip, checking himself. But Ben took note of his near-words. Riley quickly continued on a corrected course.

“You. Just like you,” and he shoved his arm with a smirk, “Mister Sir Benjamin Franklin knighted-at-age-eleven Gates. You and all your Templars and Crusaders. ‘Cause I mean, what kid wouldn't think a guy smart enough to steal the Declaration of Independence, and crazy enough or brave enough to try to save it from the bad guys, was totally awesome?”

Ben was unvoiced. All his mouth could manage was a speechless smile, as he looked at his young friend. He felt like he’d just heard a little brother tell him he was his hero. And… maybe, in a way, he had.

But it didn’t take long for Riley to notice the smile. The moment he did, he covered his tracks with a roll of the eyes, hoping to pretend he hadn’t said as much as he had. “Except for the kids who actually have the misfortune to know you, I mean.” And on “know”, he chucked the neck pillow at Ben’s face, nailing him squarely.

“Wha—they have the misfortune?”

“Yeah, you know, studies show, the coolness-craziness ratio really gets skewed over time, especially where little kids are involved.”

Snatching the pillow from where it had fallen, Ben grinned and replied, laughter in his voice. “Well, maybe they should ask you to tell the story, then. You seem to have it pretty well mapped out.”

Riley gave him a look. “If I live to have grandkids, I might. And if that pun was actually intended.”

Noticing suddenly how the thought had come out, Ben considered it. “It is now.”

“Thought so.”

As he studied the young snark, another thought lit up Ben’s mind. One that simply could not be left under a bushel. But he did hide a growing grin behind his hand, as he prepared to speak again.

“But you know,” he mused, acting thoughtful, “I’m a little surprised at you, Riley. I mean, you left out one of the key historical figures involved in the story of the Templar Treasure. And he’s not one I thought you’d forget, either, let me tell you.”

“Oh great, here comes the history lecture.” Riley turned to him, eyes firmly planted on the ceiling just above Ben’s head, looking like a teen braced for a parental scolding. “Fine. Who'd I miss?”

“The other knight.”

At his confused look, Ben leaned back, gesturing with a bit of storytelling flair himself. “Riley Poole: computer genius and sole source of common sense, fellow treasure protector against the forces of evil and Ian Howe.” Then, as Riley gaped, Ben launched into a series of smaller voices (although he barely tried to sound like a child, let alone the three to four he seemed to be acting out). “‘Tell me more about him, Grandpa! Oh, he's such a funny guy, I like his jokes! How ever did he put up with that crazy Ben? That guy couldn’t have got anywhere without Riley!’”

Riley stared at him for a few seconds. But then, to Ben’s surprise, his mouth snapped shut, and the jaw behind it seemed, for a second at least, to clench. “Come on, Ben, not cool,” Riley muttered, jerking his face the other way. “I was serious.”

Ben felt a twinge of guilt at the almost angry reaction: Riley thought he was being mocked. But before he could feel so (mistakenly) betrayed he cut himself off from anything Ben had to say—a situation Ben really, really hated—he settled a hand on Riley’s shoulder. This earned him a rather cross glance. But, seeing past the glare, he looked his young friend dead in the eyes, with a small, sincere smile.

“So was I.”

The glance lengthened into a full-on stare. “Wait, you—”

Ben could see the exact moment that the words fully sank in. The irritation became stunned surprise, and that turned to a swelling, glowing pride. It wasn’t a joke. Ben meant every word. A smile twitched at his lips. Then the swell burst, short and sudden, in a laugh like a firework. “Wow.”

And it pleased Ben mightily to see it. The sight of those blue eyes lighting up with real joy, with no hint of sarcasm, was rare. And he was doubly happy, because he was also telling the truth. Truth in every single word. Including one word in particular. One that required a little testing. Ben paused, taking the moment in a bit longer, then lifted his eyebrows, almost humourously. “Unless, of course, you’d prefer to drop the knight part…”

“No!”

Ben nearly laughed again at the eager speed of the answer. But Riley, upon realizing the same, nearly stumbled over himself to cover up with, “Um, no, no, that’s fine. The knight part… the knight part works. D-don’t worry about it.”

“Who’s worrying?” Ben grinned, hopes fulfilled. Ever since he’d told Riley about his boyhood knighthood (and truth be told, he’d never really dropped the title, at least in his own mind), he’d found it easier and easier to think of the two of them as fellow knights. But he never said that. He didn’t want to push a title on someone else if they might think it a little childish. That was why he’d needed a test, which Riley had passed with eagerness.

And yet, pleased as he was by that eagerness, it suddenly hit him how easily it could be snuffed out. The nearer they got to the treasure, the greater the danger would grow. He was sure of that. They’d already been through some real perils, and they’d escaped without injury, but how long would it be before they wound up in front of Ian’s gun again, with ever-dwindling negotiables? The old weight began to creep back over him.

“You are.”

Ben looked back up, confused. “I’m what?”

“Worrying.”

Is it that noticeable? “Oh. Am I?”

At that, something inside Riley seemed to crumble, something he tried very much to hide. “Oh.”

Ben furrowed his brow, definitely worried now. What happened? Did I say something wrong?

He started to open his mouth to ask, but Riley seemed to steel himself, taking a breath and lifting his head. “Yeah, and you know, I totally get it,” he said, quickly and in something of an apologetic tone, “it’s a personal thing from your childhood, it feels weird letting somebody else take over it. I get it. The knight part is your thing. So if you don’t want me tacking it on,” he raised his hands in surrender, “it’s fine, I won’t say anything else about it.”

“What?” This was it? After all the—he still felt out of place in Ben’s life? He still felt like he was being just a burden, a tagalong?

“What?”

Ben sighed and shook his head. “You’re not taking anything over. Knighthood is meant to be passed from one to another. And it’s too important a promise to tack on to just anybody.”

“Tell that to Jagger.”

“Too important for me to just tack on, then.”

Riley seemed reluctant to accept acceptance, no matter how many times he’d received it. “Really?”

“Trust me. You’re good. That wasn’t even close to what I was worrying about.”

He let out a quiet breath of relief. “Okay.” The pause wasn’t long, however, before he glanced back up. “But you were worrying, though. That was definitely the Ben Gates worry face.”

“I have a worry face?”

“Ehh, it’s rare, but I know it when I see it. I mean, it’s you. Worrying.” Ben conceded the point with a shrug. “So why?”

“Why?” Ben hesitated, taking a breath, but his mind made itself up quickly. No more. Riley had opened up to him; it was high time, however his friend reacted, he did the same. He slowly let out his breath. “Because I think we’re gonna need the knight part pretty soon. We’re probably coming up on some… well, some pretty difficult chapters of that story, if you know what I mean. And, if I’m gonna be honest,” and at this, his voice dropped, “I’m a little afraid to know the ending.”

Riley stared at him for a silent moment. Ben wasn’t quite sure what he was hoping for next. Hope I didn’t say too much. But then Riley nodded, slowly at first. “Wow. Yeah, I mean, me too, man.” His nodding sped up. “You know, maybe I will keep the knight part after all.”

Ben smiled, relieved, though he wasn’t sure why. “Sounds like a good idea.”

“Yeah.” Riley was quiet only a moment more before he scoffed. “You know, it’s all fine when you’re just hearing about the dangerous stuff the heroes go through. You don’t really think about how threats to your life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness actually feel.”

“Yeah, sorry about that.”

“But hey,” he shrugged, “at least those future-kids are gonna have a heck of a story. I mean, for them, we’re probably coming up on the best parts!” He laughed at his own words, but still grimaced slightly.

Ben smiled. Again, the complainer held the candle in the dark. And in that moment, Ben knew he was glad to have him on this… adventure, or whatever it could be called, no matter what happened. Riley really had been the common sense, the genius, the light (shaded in sarcasm though it was), throughout the whole thing. And Ben was sure he truly couldn’t have gotten this far without him. But he knew they were about to head off into more trouble when they got to Philadelphia tomorrow, very possibly of the life-threatening type. He had to make sure Riley was okay with facing it down.

“Sure you still wanna be a part of it?” he asked, nodding toward him. “It’s a big responsibility.”

Riley tapped the red, metal, tube-like container hanging on Ben’s seat. “I know.”

Ben nodded. “You’re right. There is a very big responsibility to keep the Declaration safe. We have enough danger just from that. But the duty of the Templars, the Freemasons, and the family Gates, now, that's all on me. Not you or Abigail or anybody else. I know I pretty much dragged you into this from the beginning, and if you’d rather stay out of the line of fire, I… wouldn’t mind letting you—”

“Oh no you don’t, Mr. Gates,” Riley interrupted, grinning widely and pointing threateningly, “you made me a treasure protector, same as all your Templars, Freemasons, and family Gates! And I promise you, I’m not about to let you write me out now!”

That’s a good enough promise for me. Then, attitude restored, Ben responded in a tone of dry humour. “Well, then, in that case, I dub thee Sir Riley.” And he smacked him on the shoulder with the neck pillow.

Sir Riley seemed to take offense to the smacking as a personal challenge, and snatched the pillow away. Ben could see a glint of war fire in his eye. However, before battle could be engaged, his eye caught a sight that was becoming pleasantly familiar, to him at least. He laughingly held up a hand.

“Okay, hold up, hold up, Abigail’s coming back.”

“Oh joy,” Riley deadpanned, a little disappointed in the forced ceasefire. Then, with a thought, he smirked at Ben. “You think even she’d be okay in a story? Like as a character?”

“Abigail?” Ben considered her qualifications for such a role. And he found he couldn’t help but smile; smile at her deep passion for history (close akin to his own), her unflagging determination, and of course, her absolute refusal to ever shut up. “Could be.” He chuckled softly. “Could be…”

He looked up to find Riley giving him a very pointed look, so Ben ignored him and glanced out at her instead. As Abigail crossed the parking lot, he pondered her a little longer. “Wonder if she thinks we're the heroes or the villains.”

By the time he noticed Riley’s movement, the window was already halfway rolled down. “Good question.” Riley stuck his head out the window and yelled across the parking lot, “Hey, Abi, do you think we're the heroes or the villains?”

Still halfway across, she stopped to give him a look and shook her head. “It’s Abigail to you, and for the record, I still think you’re lunatics.”

“Well, I knew that!”

“I mean for yelling across the parking lot.”

“Well, if we're stating things for the record, you're yelling too.”

Abigail simply rolled her eyes and resumed her walk. Riley laughed again. “Guess we’re gonna have to call off the Second Revolutionary War, huh, Ben?”

“Oh, you’ll probably break the truce at some point.”

“Keep on your toes, old man.”

Riley smiled, but fell silent as he did so, staring at the dashboard. In the moment before Abigail came up to the car, his voice returned. “So… just to be clear…” He took a breath before he spoke again, and looked up at Ben hopefully when he did. “Knights?”

Ben practically beamed as he nodded: he could finally say it was true. “Knights.”

Riley held up his fist, and they sealed their eternal covenant of knighthood and brotherhood with a knuckle-bump.

A moment later, the passenger door opened. “Also, you took my seat, Bill.”

“Sir Riley, actually. Nice to meet you, milady.”

---

Well, happy Independence Day, folks! Thanks for reading, and doubly so if you've stuck with me all the way through to the end here!

This is my first National Treasure fic, but my second Lord of the Rings fic (the first is ancient and in hiding somewhere). Since NT is so patriotic and honoring of America's history and forefathers, I figured I'd post this today.

The inspiration came from two things: firstly, that fanfiction I posted about a few weeks ago, and secondly, from the story scene in The Two Towers. The kids had the movie on, and I jumped in right around there. And maybe I just had NT on the brain, but that scene just suddenly struck me as very fitting for Ben and Riley. Who are awesome, by the way.

So I wrote up a (much shorter) first draft that day, and edited it over the next several weeks. And now it's done! And I'm rather pleased with it, for my part.

It's also on fanfiction.net and, for the first time for any of my fics, AO3, if you want to check that out too.

Again, thanks for reading, hope you enjoyed, and happy Independence Day!

#my fanfiction#national treasure#ben gates#riley poole#abigail chase#lord of the rings#happy independence day

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

retrouvaille / @treebitched

his life has been a journey that most people would gasp in disbelief, or simply not believe at all. he recalls being a small boy. guessing his age would be pointless, but he knows he still had some sense of innocence, idiocy, and ignorance about the world. the three i’s that seem to be the key to a blissful existence if they can be maintained. he liked pulling things apart - objects, and then, putting them back together again. it had started when he had broken his uncle’s camouflage-designed lighter. his uncle had always lied about how he had been a military man and fought in all kind of wars. the reality was, that he was a bum and had been in so much trouble with the law, that no good place of work would take him. and so, it seemed like being a fabricated veteran was a good enough excuse to tell people as to why he didn’t work.

but max had known the lighter had meant a lot to him. as if it would continue this image he’d created of himself. and he knew, that if unfixed, his uncle would do what he often did - and often didn’t need an excuse for; violence. max had quite a knack for fixing things. his mother, a mentally ill, abused woman, had doted over max claiming that he’d be a doctor when he was older - a surgeon. but they had such little money for an education that the idea of such a profession seemed laughable. it was only when max got into computers that he’d earned enough money to buy himself into college. to sit among kids from hallmark happy families and middle-class upbringings. for a while, they seemed to look at max as if he were the token poor kid. it was only when he began to use his intelligence, to laugh in their faces at their mistakes, and use manipulation, that he won them over. charm, he’d learned, was a good way to lure people into false security.

he’d fucked many women throughout college. he’d smile and they’d flock to him like geese after breadcrumbs. and becoming this heartless killing machine, max had learned more things about people. like how plants are more courageous than human beings: an orange tree would rather die than produce lemons whereas instead of dying, the average person would rather be someone they are not. it’s why he finds that when he kills, it’s merciful rather than cruel. people just don’t see it that way. far too weaved into sociological ideas of how society should be. but all of these unwritten rules are written by white men from the 1500s. and max could say a lot about that time in history.

things had changed when he met willow. simple willow. blonde and stupid. he could have killed her. should have. didn’t. somehow along the way had found himself fascinated and infatuated with her. somewhere along the way, had become distant from her. if only because she had met another man. someone seemingly more trustworthy than max. more truthful in her eyes, but max thinks she only likes the truth when it’s said with flowers and soft-spoken words. not direct, harsh overtones. he hadn’t seen her since. a weird disappearance. nothing in the news. or the papers. no words were spoken about her on the street. just gone like a leaf being blown by the wind. you see it one moment and don’t think about it when it’s out of your eye line.

but tonight he’d seen her. he was out of town. skipped town. hands in pockets on a cold night, in a big coat. the road is quiet. empty. he waits for the bus that comes every hour thirty. but he sees her, across the street, like some kitten that’s been dumped in a cardboard box by some lousy owner who can’t make a quick purchase on a dumb cat. and joy fills him. and aggression. he wants to hurt her with how overwhelmed he feels with this...happiness. psychologists will call it cute aggression, but they don’t understand how easy it would be for max to actually follow through with killing her right now. “ weepy, ” he calls as if he’s recalling a dog that has fetched a ball. “ don’t tell me this is where mister romantic has left you. this isn’t very paris ”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Magdalene by FKA Twigs, a review.

youtube

I’ve been learning some shit from women from as long as I’ve been alive. Always some other shit that I never asked for but I got told it. I used to treat them things they said as laws as a child, but I never saw them in a book, so then I stopped believing them. They were always hushed laws though, laws told with squinted eyes and italicized whispers, laws told when no one else was around.

I mean, now of course men make the real laws that we know and live by. Well come on now, we write them on parchment, and display them on lights, we code them into computers, inscribe them on coins and stone. But these women…man women tell you some other shit, like glue shit, in low, muttered tones in the quiet part of the house. Like advice on… well not how the world works, but how to deal with the world when it works against you, and how to make it work for you. But you see, I’ve come to believe that the fairer sex tells you different laws than the vaunted laws and advice of our fathers because they all around see the world differently than men do. They may, in fact, have been harbouring different goals than us all along.

I mean for christssakes us men have our hero’s journey as clear as day, writ large and indelible across history books and entertainment. You could take that Joseph Campbell mono-myth theory and see it expressed in Arthurian swash-buckle, the middle earth ring-slaying of Tolkien, or in the recently concluded tri-trilogy of Star Wars galactic clashes. We’re in the empire business, as Breaking Bad’s Walter White infamously said. But still, the question always lingered to me: what is the heroine’s journey? Is it really just a lady in a knight’s armour? Or some tough-as-nails spy for some interloping government’s intelligence agency, delivering kidney kicks in a designer pencil skirt?

Well, I’ve come to believe that the heroine’s journey is navigating the waves of history we imperial and trans-national men make from our railroads and pipelines, our satellites and wars, them at once preserving a culture and sparking a path and creating a bond between cultures in order for them and their (il)legitimate brood to survive. That old chestnut about how behind every successful man is a woman always unnerved me by its easy adoption. I kept thinking ‘bout that woman. I kept thinking, what the fuck was she thinking?

You see women’s heroes, they ain’t as clear as day to me. They don’t kill the dragon, they don’t save the townspeople, they don’t shoot the Sherriff, or the deputy, or anyone most times. When I ask people in public at my job what super power they would like, most men go for strength, flight, and regenerative abilities (my pick). Most women went with mind reading and flight. In late night conversations though, with the moonlight coming through the white blinds and resting soft on us like so, I sometimes manage to hear that women’s heroes heal and clean the sick of the nation, in sneakers with heels as round as a childhood eraser; they feed a family with one fish and five slices of wonder bread; they would run gambling spots in the back of their house, putting the needle back on the Commodores record and patrolling the perimeter of the smoked-out room with a black .45 nested by their love handles; they climb up flag poles and speak out loud in public for the disposed and teach children those unwritten, floating laws while cloistered in the quiet part of the house.

Although their heroines are sometimes from the top strata of society –a Pharaoh here, an Eleanor Roosevelt there, an Oprah over there—they also name a healthy mix of radicals and weirdos with modest music success, people like Susan B. Anthony, Frida Kahlo, Virginia Woolf, or Nikki Giovanni, I mean did Nina Simone or Janis Joplin even crack the Billboard top ten? Yet there they are, up on the walls of a thousand college dorms across the country. So even though I couldn’t’ve foreseen it, it makes sense that of all the ultra-natural creatures, of all the great conquering kings and divining prophets of the Holy Bible, Mary Magdalene ends up the spirit animal for the album of the year for 2019.

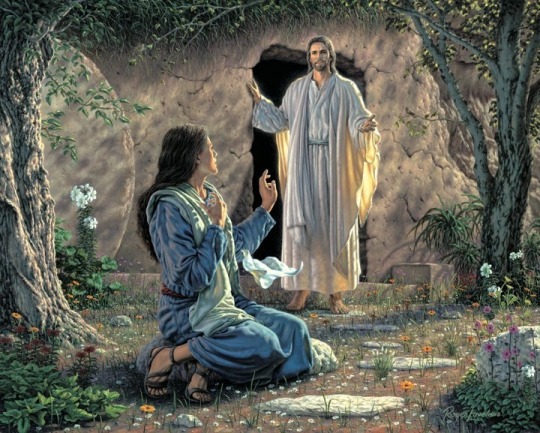

Mary Magdalene was a follower of Jewish Rabbi Jesus during the first century, according to the four Gospels of the New Testament of the Bible, a figure who was present for his miracles, his crucifixion and was the first to witness him after his resurrection. From Pope Gregory I in the sixth century to Pope Paul VI in 1969, the Roman Catholic Church portrayed her as a prostitute, a sinful woman who had seven demons exorcised from her. Medieval legends of the thirteenth century describe her as a wealthy woman who went to France and performed miracles, while in the apocryphal text The Gospel of Mary, translated in the mid-twentieth century, she is Jesus’ most trusted disciple who teaches the other apostles of the savior’s private philosophies.

Due to this range of description from varying figures in society, she gets portrayed in differing ways, by all types of women, each finding a part of Magdalene to explain themselves through. Barbra Hershey, in the first half of Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) plays her as a firm and mysterious guide, a rebellious older cousin almost, while Yvonne Elliman, in Norman Jewison’s 1973 film adaptation of Lloyd Weber’s Jesus Christ Superstar is lovelorn and tender throughout, a proud witness of the Word being written for the first time. In “Mary Magdalene,” FKA Twigs, the Birmingham UK alt-soul singer, describes the woman as a “creature of desire”, and she talks about possessing a “sacred geometry,” and later on in the song she tells us of “a nurturing breath that could stroke you/ divine confidence, a woman’s war, unoccupied history.” Her vocals that sound glassy and spectral in the solemn echoes of the acapella first third, co-produced by Benny Blanco, turn sensual and emotive when the blocky groove kicks in. That groove comes into its own on the Nicolas Jaar produced back third, and when this all is adorned with plucked arpeggios it sounds like an autumnal sister to the wintry prowl of Bjork’s “Hidden Place” from her still excellent Vespertine (2001).

This blending of the affairs of the body and of Christian theology is found in the moody “Holy Terrain” as well. While it is too hermetic and subdued to have been an effective single, it still works really well as an album track. In this arena, Future is not the hopped up king of the club, but a vulnerable star, with shaded eyes and a heart wrapped up in love and chemicals, sending his girl to church with drug money to pay tithes. Over a domesticated trap beat he shows a vulnerable bond that can exist, wailing his sins and his devotion like a tipsy boyfriend does in the middle of a party, or perhaps like John the Baptist did, during one of his frenzied sermons, possessed and wailing “if you pray for me I know you play for keeps, calling my name, calling my name/ taking the feeling of promethazine away.”

Magdalene, the singer’s sophomore release, takes the mysterious power and resonance of this biblical anti-heroine, and involves its songs with her, these emotional, multi-textured songs about fame, pain and the break up with movie star boyfriend Robert Pattinson. With “Sad Day,” Twigs sings with a delicate yet emotional yearning, imbued with a Kate Bush domesticity. The synth pads are a pulsing murmur, and the vocal samples are chopped and rendered into lonely, twisting figures. The drums crash in only every once in a while, just enough to reset the tension and carve out an electronic groove, while the rest of the thing is an exercise in mood and restraint, the production by twigs, Jaar and Blanco, along with Cashmere Cat and Skrillex, leaves her laments cosseted in a floating sound, distant yet dense and tumultuous, the way approaching storm clouds can feel. Meanwhile “Thousand Eyes” is a choir of Twigs, some voices cluttered and glittering, some others echoed and filled with dolour. “If you walk away it starts a thousand eyes,” she sings, the line starting off as pleading advice and by the close of the song ending up a warning in reverb, the vintage synths and updated DAWs used to create these sparse, aural haunts where the choral of shes and the digital ghosts of memory can echo around her whispered confessional.

In many of these divorce albums, the other party’s role in the conflict is laid bare in scathing terms: the wife that “didn’t have to use the son of mine, to keep me in line” from Marvin Gaye’s Here My Dear from 1979; the players who “only love you when they’re playin’” as Stevie Nicks sang on Fleetwood Macs Rumours (1977); or as Beyonce’s Lemonade (2017) charges, the husband that needs “to call Becky with the good hair.” At first though, Twigs is diplomatic, like in “Home with me,” where she lays the conflict on both sides here, expressing the rigours of fame, the miscommunication –accidental or intentional –that fracture relationships, and the violent, tenuous silence of a house where one of the members is in some another country doing god knows what, physically or mentally. “I didn’t know you were lonely, if you’d just told me I’d be home with you,” she sings in the chorus over a lonely piano, while the verse sections have the piano chords flanked by blocks of glitch, and littered with flitched-off synths. Then, the last chorus swirls the words again, along with the strings and horns and everything into a rising crescendo of regret.

Later in the album however, her anger once smoldering is set alight, in the dramatic highlight “Fallen Alien.” Twigs sings with an increasing tension, as her agile voice morphs from confused, pouting girlfriend to towering lady of the manor, launching imprecations towards a past lover and perhaps fame itself. “I was waiting for you, on the outside, don’t tell me what you want ‘cuz I know you lie,” she sings, and, after the tension ratchets up becomes “when the lights are on, I know you, see you’re grey from all the lies you tell,” and then later on we have her sneering out loud “now hold me close, so tender, when you fall asleep I’ll kick you down.” All while pondering pianos drop like rain from an awning, tick-tocking mini-snares and skittering noises flit across the beat like summer insects, the kicks of which are like an insistent, inquisitive knocking at the door, and then there’s that sample, filtered into an incandescent flame, crackling an I FEEL THE LIGHTNING BLAST! all over the song like the arc of a Tesla coil. The song is a shocking rebuke, and it becomes apparent upon replays that the songs are sequenced to lead up to and away from it, the gravitational weight giving a shape and pace to the whole album. Because of this, the other songs on Magdalene have more tempered, subtle electronic hues and tones, as if the seductive future soul of 2013s “Water Me” from EP2, and the inventive, booming experimentation of “Glass & Patron” from 2015s M3LL1SSX, were pursed back and restrained until it was needed most, and this results in an album more accomplished, nuanced and focused than her impressive but inconsistent debut LP1 (reviewed here).

This technique of electronic restraint has shown up in the most recent albums by experimental pioneers, with the sparse, mournful tension of Radiohead’s A Moon Shaped Pool (2017), it’s cold, analog synths and digital embellishments cresting on the periphery of the song, and with Wilco’s Ode to Joy from last year, an album bereft of their lauded static and electric scrawl, mostly embossed in acoustic solitude and brittle, wintery guitar licks. Twigs and her co-producers take the same knack for the most part throughout the album, like with closer “Cellophane,” where the dramatic voice and piano are in the forefront, while effects crunch lightly in the background like static electricity in a stretched sweater, and elsewhere, as the synths of “Daybed” slowly intensify into a sparkling soundscape, as if manufacturing an awakening sunrise through a bedroom window. And it is this seamless melding of organic and electronic instruments, to express these wretched and fleeting emotions of heartbreak that makes this the album of the year.

It makes sense that an artist like FKA Twigs would be drawn to a figure like Mary Magdalene. Of the many Marys in the New Testament, she stuck out as palpably different, or rather, she depicted a differing part of womanhood than the other two. She wasn’t the chaste, life-giving mother of Jesus, or the dutiful Mary of Clopas. Instead, Magdalene was this mixture of sexuality and spirituality, one of those figures that managed to know men and women in equal measure, wrapped up with the blood as well as the flesh. Twigs also played with this enrapturing sexuality in her work, writhing around in bed begging some papi to pacify her and fuck her while she stared at the sun, then making you identify with the lamentations of video girls, and then telling you in two weeks you won’t even recognize who you were seeing before. There was something mysterious and layered to her millennial art-chick sexpot act though, layers that have begun to be revealed with this album.

We realise now, that what she was depicting all along was more like the sexual heat that lays underneath devotion, as opposed to fleeting, mayfly lust, and that she now understands the weight and half-life of love. That is, that beyond the sex and patron and fame there is a near sacred love we build between each other for a while in time, lasting as long as both hands can bear to hold it, and also that the death of a relationship still has the memory of the love created warm within it that then radiates off slow into the air. A love that then falls into our minds for safekeeping dark and unobstructed now, the way Jesus’ blood fell from his wound into Joseph of Arimathea’s grail held aloft.

“I never met a hero like me in a sci-fi,” FKA Twigs sings, an evocative line less so for the hegemonic patriarchy of the worldwide movie and comic book industry suggested by ‘the sci-fi’ here, and more for the ‘hero like me’ part, which suggests she had to make her hero origin story all up, without the scaffolding of centuries of relatable mythologies, presenting us with an avatar of millennial love, in all of its tortured luster. And you hear this type of love in her voice, no longer changed up and ran through a filter for Future Soul sophistication most times, but out in the open now, to express particular emotions, whether it’s in that swooping, falling ‘I’ in the heart-break closer “Cellophane,” or her assured realisation, later on “Home With Me” where she says “But I’d save a life if I thought it belonged to you/ Mary Magdalene would never let her loved ones down.”

youtube

It’s never about how to conquer with these women you see. In the end of all relationships it’s how they find their way out after us temporarily embarrassed conquerors are about to leave, jacket slung over shoulder, standing by the door. You squint your eyes back at her this time, and you listen this time, while she tells you, or tells the ground in front of you, what parts of love to let go of, and what parts are worth holding on to in this age of Satan, the parts that will help you become yourself. “I wonder if you think that I could never help you fly,” the song tells you then, one of those stinging admissions that only women come up with, and you wisely stay silent, and then the piano chords part, the synths subside. And for a while there as she looks at you, as the breathy sortilege in the song keeps going, it all sounds like something worth believing in again. And then, the words she says to you start to come across like laws.

#music#music review#rnb#rnb music#r&b#soul#future soul#future pop#alt soul#electronica#fka twigs#magdalene#mary magdalene#cellophane#Long Reads#sad day#hiro murai#new music

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

in regards to that ask about antitrust laws, and laws in general, what would you have as "laws" in an anarchic society? i dont know much about common law, is that your/a solution?

Anarchist philosophy, in practice, is a society “without rulers” (the literal definition). Many people conflate “anarchy” with “lawlessness”, and the confusion is certainly understandable. However, governance exists with or without the State and it begins with the self, extending into the home, and beyond. Many people struggle because they conflate the concept of governance with the function of a State; I had been guilty of this before I understood anarchy to mean self-governance.

We are self-governing in all of our relationships, whether it’s between a mother and child; between her and her employer; between child and teacher; buyer and supplier; disputing parties and an impartial arbiter, etc.

Mutual assent to the establishment of these relationships (and the countless others I didn’t list) is an inherently regulatory act because people set their terms, expectations, conditions, etc. before committing to them voluntarily with the exception of that between a parent and child (because who can ask you if you want to be born?)

The beauty of a free and open marketplace of ideological exchange is that people have the ability to come together and brainstorm solutions to problems that are impacting their lives. It is a far more direct and sensible approach to delegating those decision-making powers to some bureaucrat 2,000 miles away with absolutely no interest in your interests apart from saying the right combination of words to assure they are reelected for the benefit of legal and economic privileges which invariably manifest when a single, central authority has a monopoly on force and law.

Consider reading up on legal pluralism (I write about it a lot, as well). This is the notion that all people follow multiple codes, bodies of law, or moral guidelines simultaneously, even while some may conflict or overlap. Studying how various cultures throughout history have solved conflict or maintained peace can help people recognize solutions outside of the narrow confines of the State. For example, many individuals conform to social norms within the home that they would not exhibit in the workplace (and vice versa).

Anarchy isn’t the establishment of a DMV to issue you a driver’s license (that’s Statism). Anarchy is the privatization of roads, car insurance, and licensure so that the three can work in tandem to provide and maintain the infrastructure which services us as freely and efficiently as economically possible without coercion. Anarchist society, much like an economy, organizes itself without an arbitrary central authority; what works for some may not work for others. Communities are self-organized, markets are spontaneous. For instance, take this excerpt from Everyday Anarchy on dating, marriage and family:

In any reasonably free society, these activities do not fall in the realm of political coercion. No government agency chooses who you are to marry and have children with, and punishes you with jail for disobeying their rulings. Voluntarism, incentive, mutual advantage – dare we say “advertising”? – all run the free market of love, sex and marriage.

What about your career? Did a government official call you up at the end of high school and inform you that you were to become a doctor, a lawyer, a factory worker, a waiter, an actor, a programmer – or a philosopher? Of course not. You were left free to choose the career that best matched your interests, abilities and initiative.

What about your major financial decisions? Each month, does a government agent come to your house and tell you exactly how much you should save, how much you should spend, whether you can afford that new couch or old painting? Did you have to apply to the government to buy a new car, a new house, a plasma television or a toothbrush?

No, in all the areas mentioned above – love, marriage, family, career, finances – we all make our major decisions in the complete absence of direct political coercion.

When you barge into your friend’s room to ask them if you can borrow their shirt, most people close the door behind them when they leave (especially if the door was closed before you entered). It’s almost an unspoken rule to close the door behind you in such a scenario and adherence to this rule illustrates the concept I mentioned earlier: legal pluralism. This concept reflects the reality that human interaction, left to our own devices, is governed by prevailing social and cultural values and that those values are inherent to our conduct.

Besides what we consider to be “the law,” we also follow an innumerable set of unwritten rules in our day-to-day conduct. You must have noticed at this point in your life, for example, that your behavior alters between spending time among friends and spending time among family. Likewise, in the work place your demeanor shifts to conform to the standards expected of your performance in that setting. In every scenario, the penalty for breaching the terms of these unspoken norms is usually a sanction in some form or another: your parents ground you, your friends ostracize you, your boss docks your pay, etc. They do this because people respond to incentives.

Though you don’t realize it, this is anarchy in action. More examples of this are virtually limitless; the relative silence one finds in theater atmospheres is a result of a mutual, unwritten understanding between all patrons. Commercial businesses regularly agree to third-party arbitration clauses all the time, regulating the conduct of their contractual obligations outside of the confines of the Uniform Commercial Code or Federal government. Even the Juggalos have been known to settle their disputes within the context of their own communities. There are no ‘one size fits all’ answers to “what if?” scenarios.

Anarchy should not be conflated with lawlessness. A great reading recommendation on customary law, culture, and history is short book written by Dorothy Bracey called “Exploring Law and Culture”. I think its perfect introductory material to the principles within legal theory, especially for people unfamiliar with the murky concept known as “the law”. It’s short and written for the average reader rather than legal scholars.

And finally, here are a few more resources:

Mutualism:

A Mutualist FAQ

The Homebrew Industrial Revolution: A Low-Overhead Manifesto (2010) by Kevin Carson

Studies in Mutualist Political Economy (2007) by Kevin Carson

Organization Theory: A Libertarian Perspective (2008) by Kevin Carson

What is Property? An Inquiry into the Principle of Right and of Government (1840) by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

The Philosophy of Poverty (1847) by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Individualist anarchism:

The Ego and Its Own (1845) by Max Stirner

Vices Are Not Crimes: A Vindication of Moral Liberty (1875) by Lysander Spooner

Individual Liberty (1926) by Benjamin Tucker

Anarchist Individualism and Amorous Comradeship by Émile Armand

The Anarchism of Émile Armand

Agorism

Voluntaryism

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Effects of Common Law System in India

This article is written by Madhuri Pilania from Symbiosis Law School, Noida. This article deals with the Effects of the Common Law System in India.

Introduction

The Common Law is a body of law which is derived from judicial decisions also known as case laws. Common Law has been derived from the universal consent and the practice of the people from time immemorial. It is a system of jurisprudence which initially originated in England. It includes those set of rules of law which derive their authority from the statement of principles found in the decisions of Courts. The common law system includes tradition, custom and usage, fundamental principles and modes of reasoning. It is the embodiment of comprehensive unwritten principles, which were derived out of natural reasoning and sense of justice.

This system requires several stages of research and analysis to determine the appropriate law in a given situation. The facts should be ascertained properly and relevant cases and statutes are to be identified. The common law is different from codified law as it follows the judgment while the codified law precedes it. So it can be rightly said that it is a system of rules and declarations of principles from where the judicial ideas and legal definitions are derived.

If a similar dispute has been resolved in the past, the Court is bound to follow the reasoning used in the prior decision. In other words, it is developed by judges through decisions of courts and similar tribunals that are also called case laws.

It gives precedent weightage to common law, on the principle that it is unfair to treat similar facts differently on different occasions. The precedent is also known as “common law” and future decisions are bound by it. In future cases, when parties disagree on what the law is, the common law court looks to past decisions of the relevant Courts.

If a similar dispute or case has been resolved in the past, the Court is bound to follow the reasoning used in the prior decision this is also known as the doctrine of stare decisis. If the Court gets to know that the current dispute is different from the previous decisions of the cases, then the judges have the authority and duty to make law by creating a new precedent. The new decision of the Court becomes precedent and it will bind the Courts in future also. But sadly, the development of the common law in many cases is now of historical interest only. However, the basic principle is preserved, statutory changes have been made which modify the effects of many landmark cases.

Click Here

History of Common Law

It is a term that was originally used in the 12th century, during the reign of “Henry II” of England. The ruler established tribunals with the goal of establishing a system which is uniform in deciding legal matters. Such decisions created a unified “common” law throughout England. The precedent set by the Courts through the twelfth and thirteenth centuries were often based on tradition and custom and was known as a “common law” system.

Common law in the United States dates back to the arrival of the colonists, who brought with them the system of common law with which they were already familiar. They followed the American system and the newly formed states adopted their own forms of common law which were different from the federal law.

The application of common law has been comprehensive in the Indian context. It has been incorporated in the Indian legal system over two centuries by the English to the point that one cannot assign an individual identity to Indian jurisprudence. Therefore, it can be said that common law has been applicable in a different format than that of England as the needs and demands of the Indian society were different from that of the English.

It is found that much of the law compiled in codes that we have today were primarily derived from the Common Law principles.

The basic statutes that govern Civil and Criminal justice are the Indian Penal Code, 1860, Indian Evidence Act, 1872, the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 and the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908.

One thing can be said about these legislations is that they have stood the test of time with minimum amendments. Codification of laws made the law consistent throughout the country and stimulated a kind of legal unity in fundamental laws. The Codes apply uniformly throughout the nation.

Indian legal system by Common Law is another contribution of the adversarial system of trial. In this system, the person who is accused is presumed to be innocent and the burden is on the prosecution to prove reasonable doubt that he is guilty. The accused enjoys the right to silence and cannot be forced to reply. The truth is supposed to come into view from the respective versions of the facts presented by the prosecution and the defence before a neutral judge. Both the parties have a right to question their witnesses and the opposing side has a right to test their testimony by questioning them. The judge acts like an overseer to see whether the prosecution has been able to prove the case beyond reasonable doubt and gives the benefit of doubt to the accused. His ultimate duty is to pronounce the judgment regarding the matter.

Does Common Law lead to Judicial Overreach and Judicial Activism?

If the Judiciary gets into the creation of laws or steps into the role of the Executive without a strong reason, it leads to the situation of Judicial Overreach. In other words, it occurs when the Court acts beyond its jurisdiction and interferes in making of the laws. Common law system leads to judicial overreach because common laws are judge-made laws.

Judges continuously apply the existing laws to new situations and thus creating new laws. Judges perform the judicial function and go through the historical, social and legal text. It is considered as activism and becomes law themselves. Judicial activism has created the scope for judge-made laws or the common law system and that is an abuse of the constitutional power given to them. Judge’s decision is affected by several social and political factors that lead to judicial activism and judicial overreach.

The Legislative creates laws and the judiciary is supposed to interpret and enable the implementation of laws and not make laws.

Judicial Review and Activism are considered as valid and necessary. Judicial overreach is sometimes considered as an obstruction or undermining the functions of other arms of the Government. Judicial precedents have derived their force from the doctrine of stare decisis.

Common Law is Rigid and Inflexible

The Common Law has a number of defects but it is mainly rigid and inflexible. The inflexibility of the system leads to injustice because matters that were not within the scope of writs recognized by the Common Law are dismissed. Also, the Common Law does not recognize rights in the property other than those of strict legal ownership. The Common Law Courts had no power of enforcement. Also, it does not allow any form of oral evidence.

Clear weakness of the precedent is the inflexible nature of binding precedent. Lower Courts in the hierarchy are bound by existing precedent if they cannot distinguish material facts. Judgements from such previous cases are not taken into consideration. This creates a system of lawmaking that is rigid and not open to change.

Does Common Law give rise to Jury Trial and Adversarial System?

The adversarial system is a legal system that is used in the Common Law countries where two advocates represent the cases of their parties to a jury or judge. They determine the truth and pass the judgement accordingly. It is a two-sided structure.

A trial without a jury, in which both questions of fact and questions of law are decided by judges is known as a bench trial. The lawyers are given free advice for the issues that they present. The judge presides over the trial and rules on issues of procedure and evidence, asking questions of the witness to clarify evidence. He concludes the trial by summing-up the facts for the jury and advise them about the relevant law. It is not open to the judge in an adversarial system to enquire the facts and evidence beyond that are presented by the opposing lawyers. The role of the judge is largely passive, but the judge can be partial sometimes on giving his views or judgements.

Solutions to the Issues

Judges are required to apply the laws made by the executive and the legislature. In Common Law, judges make the laws that lead to judicial overreach. If the integrity of the judiciary needs to be preserved, it is important that the executive and the legislature acts with accountability and transparency.

To ensure the checks and balances, the Constitution separates the powers between the executive, legislature and the judiciary in a political democracy. Any laws made or any amendment made is the domain of the legislature and not the judiciary.

The judiciary can introduce or enforce policies which are the domain of the executive, it can lay down regulations which are the domain of the legislature and in this way the work and powers divided can reduce the need of judicial overreach.

There should be some mechanism that checks judicial overreach that will make the judiciary accountable to the citizens. Judges need to remember that their work is to interpret law and not make or give laws.

The jury trial has given rise to a system in which facts are concentrated in a single trial rather than multiple hearings and therefore the trial of Court is greatly limited. Jury cases can be reduced in number to avoid the impartiality in the decision of the cases. A judge in jury should discharge the person who is unsuitable for jury services. There should be a system of alternate juror in England and Wales to take the place of discharged juror.

No external pressures and threats should be allowed and the jury should not be under the influence of the trial judge. Adversarial may lead to injustice thus, to avoid that, fair trials are needed. It should properly observe the rights of the defending and prosecuting rights and prosecution should be allowed to present the facts as they are interpreted. Both the parties should be given a chance to present witnesses and evidence to support their positions.

The only remedy provided by the Common Law was not appropriate and also damaged in certain cases. This led to injustice and the need to remedy the weaknesses in the Common Law system was there. A general rule is less likely to do justice in all the particular cases as the facts of the cases may not be the same each time.

An attempt to construct the qualifications in advance, it is necessary to do justice in all cases. But it would lead to a system of rules that are too complex, even if all the problems could be foreseen.

The Court of Chancery emerged as a solution to the common problems faced by the Common Law system by the law of equity. Equity of law was derived to balance some fair results because of some strict decisions in the past in Common Law. The decisions in common law were subjected to injustice. The decisions were permanent and rigid as they were made by the judges. Equity came to remedy Common Law as they did not provide a fair result. Equity system is a separate system of law and it moderates the Common Law and also helps to soften the Common Law. Equity provides remedies like injunctions, specific performance, compensation, rectification and many more. Equity can use the common injunction to prevent Common Law judgement being enforced so that there is no injustice in the decision made by the judges. There should be common rules in Common Law so that judges are not liable for the conduct. Judges have to follow the precedent but if they could change it, the rigidity of Common Law can be reduced. It was made so that the errors in Common Law can be minimised.

Conclusion

Common law has disadvantages for which remedies can be derived. In Common Law, no two cases can be the same, therefore, the laws made by the judges need not be a perfect match with the facts of the case. The Common Law system was originally derived from England. It started because there were different situations for different cases and so the judges made case laws rather than applying the general statements of principle. However, some defects were found in this system.

It is rigid and not flexible since once the case judgements are made, it needs to be followed in the same way and no changes can be made. Lengthy records need to be maintained and to access the previous cases, a uniformity needs to be there. Nothing is codified like the other laws. In other countries, this system is popular along with jury trials. To remedy the defects of the Common Law system, the concept of Equity of law came. Also, Common Law sometimes leads to judicial overreach which can be overcome. The body of past Common Law was made to bind judges to ensure consistency and uniformity in deciding the case judgement but because of this, it became rigid. It can be said that Common Law has been applicable here in a different format than that of England as the needs and demands of the Indian society were different from that of the English.

References

https://www.jstor.org/

https://www.lawteacher.net/free-law-essays/administrative-law/what-is-common-law-administrative-law-essay.php

https://common.laws.com/common-law/common-law-v-statutory-law

The post Effects of Common Law System in India appeared first on iPleaders.

Effects of Common Law System in India published first on https://namechangers.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Meeting of the Mentors

By Andrea Wuerth

There was Earl and Ronny. Miss Frieda, Miss Lily and Miss Gwen. And the Reverend Williams. All sitting in the front room of the Marion Cheeks Jackson Center. Connected to each other through a shared experience: growing up in the 1950s, 60s and 70s surrounded by a network of unofficial mentors in Chapel Hill’s Northside neighborhood. They were gathered recently on a Tuesday night in August, next door to the church many of them grew up in, because they are mentors to a new generation of kids, growing up in very different times without the benefit of the tight-knit community they knew.

The kids they are mentoring live scattered throughout Chapel Hill, often far beyond the borders of the Northside neighborhood. Kids who know very little if anything at all about the history of Northside or about segregation, civil rights activism, and school desegregation in their own backyards. The mentors, armed with their personal histories, are changing that.

They tell kids about their own experiences in segregated schools and neighborhoods, in sit-ins and protest marches, and as some of the first black kids to attend integrated schools. But tonight they are here to share their stories with each other.

Very quickly, the discussion begins to focus on relationships. Relationships in the various Northside neighborhoods (Pottersfield, Sunset, Tin Top, Pine Knolls) between black kids “coming up” and a whole range of adults who all knew who they were and who their parents were. They were teachers, ministers, other people’s parents, extended family members, shopkeepers. And sometimes, as Miss Frieda pointed out, it was an older kid who looked out for you or reminded you how to act. The others nodded and agreed emphatically. The stories just came rolling out, one after the other.

They also talked about relationships with white people in Chapel Hill—bosses, policemen, university students, politicians. And astonishingly, when talking about the people who so often looked down on them, they emphasized the importance of keeping the lines of communication open, of staying focused and developing long-term goals– most often very long-term goals– and of acknowledging the small victories.

According to Reverend Williams, speaking with a knowing smile and slow nod: “Chapel Hill is a unique place. You could talk to the whites. It ‘s unlike any other place.”

In the front room at the Jackson Center, most of those present echoed this sentiment, that relationships between black and white people were what made Chapel Hill such a unique place. And yet, these relationships so often appeared to be a sort of dance. In the early 1960s, when white town leaders anticipated rising discontent with their reluctance to integrate the schools or the police force, they would make a step towards the black community, implementing a change in the right direction. White town leaders were able to give an inch so that they would not have to give a yard. And the town of Chapel Hill was able to maintain its progressive reputation Social justice requires more than a step; it requires that both partners choreograph the dance. And the music has got to be something other than “Dixie.” This hasn’t happened.

Though some of the assembled generously put a positive spin on it, black-white relationships sometimes were based upon mutual acknowledgment and even mutual regard; but the stories they told show they were not based upon equality or upon recognition that both parties’ viewpoints were equally valid or upon the value of different perspectives.

The town’s liberal reputation seems to rest on an unspoken paternalism. The relationships between whites and blacks in Chapel Hill both before and after segregation was officially outlawed, were and still are based upon inequality, held in place partly by friendly gestures, partly by the threat of violence.

Reverend Williams recalled a relationship with a Mr. Pendergraft, the owner of a garage on Franklin Street. His uncle, a black man, had worked for Mr. Pendergraft for decades. Somehow this relationship guaranteed his uncle that no harm would come to him, despite the fact that everyone knew he hosted weekly Klan meetings. In fact, when Reverend Williams was small, he remembers looking for his uncle and instead running in to Mr. Pendergraft dressed in his Klan robes. Robby Bynum tells the story of how he had to be counseled by elders in the Northside community to help him overcome the fear that gripped him whenever he had to leave the safety of his neighborhood and venture into white Chapel Hill.

Violence could be avoided if a person was not perceived as threatening the balance of power in which white people’s freedoms and privileges were accepted and unquestioned. Relationships with whites were possible, even encouraged, so long as everyone understood that the balance of power would remain firmly in the hands of white people. An occasional glimpse of a Klan robe was a clear reminder of how far some whites in town would go to see that the balance wasn’t upset. And so, as some of the mentors mentioned, parents would often tell kids to stay away from Franklin Street when the civil rights marchers came through. Those relationships their parents had established with white people in town could be seriously jeopardized if word got out that a family member was protesting.

The liberal traditions the university town celebrates are understood very differently by those who grew up on the “other side” of Franklin Street. Many black residents talk about surviving and getting by here, living, often fearfully, by a code—written and unwritten– that existed just as it did in the rest of the state. That’s what I hear behind Rodney’s gracious words: “Don’t let your feelings get in the way of your spirit.”

So many liberals live in all-white neighborhoods, unaware of the dwindling supply of affordable housing, well-paid jobs, educational support and business opportunities. But more importantly, what’s missing is a community knit together by lasting, meaningful relationships. Without a neighborhood and a feeling of community, these networks are strained and have to be created deliberately rather than organically.

This group of volunteer-mentors were all in, ready to connect with students, ready to continue the work of mentoring kids they don’t know but want to know. And they have a wealth of experience and wisdom and love to offer.

Every person in the room at the Jackson Center that night had experienced Chapel Hill’s racism. And yet every one committed themselves fully to building bridges and honoring the tradition of building relationships. How long will it take for white people to accept relationships based upon real and true equality? I think it’s clear that it can only happen when the oppressors hear the voices that are speaking truth to power. And to really listen.

If you want to hear history speak its truth, start talking to the mentors of Northside. The Jackson Center is open.

Andrea Wuerth is a volunteer participant in the Center’s Learning Across Generations local history curriculum and our Oral History Archive. She agreed to let us post her blog entry after archiving Hollywood’s oral history interview. Access to Andrea’s full blog can be found here.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Slavery: Who is to Blame?