Essays, reviews, short stories and free writes on music, film and life around us.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Who Is The Living Queen Of Soul?

You can vote on the Queen on the R&B subreddit here

In particular, the death of singer Aretha Franklin in August 2018 left a gash in the collective cultural psyche of America, a deepening crevice that I believe worsens the longer the title of Queen of Soul music is left uninhabited.

Upon reflection, it becomes apparent that what Aretha’s reign of Soul music most importantly did was to codify the musical textures, vocal phrasing and techniques of presentation comprise Soul music and R&B in general. Since her death, R&B music has given me a curious, rudderless impression, as if waiting for a style to settle upon, or for an emotion clear enough to spin into a groove of sentiment. What the genre needs, is a refocusing of its strengths, that broad-chested arrogance that imagination brings and the polestar of excellence that only a queen can bring. Therefore, it begs the question: who is the living Queen of Soul?

Four candidates come to my mind when thinking of living embodiments of the genre of Soul music: Gladys Knight, Patti LaBelle, Chaka Khan and Mary J. Blige. These women have each created multiple classic Soul, R&B and Disco records, spanning multiple generations, each one with enough lasting resonance to be sampled in prominent Hip-Hop records. They exemplify the genre, but with their own idiosyncratic strong points, and would chart a disparate course for the future of R&B if one was chosen as Queen of Soul over the other.

To many, especially in the American South, Gladys Knight would be their reflexive choice, the Southern Georgia bred voice that, between 1957 and 1987 powered her group The Pips 19 top 20 R&B hits with 16 of those becoming top 20 Pop hits. She imbued a deep pathos of longing on songs “Help Me Get Through The Night,” “If I Was Your Woman” and the classic “Midnight Train To Georgia.” Her church-taut control of her alto voice is the engine of the group's biggest hits, that reign brightest during her Motown years of 1966 to 1973, her languished phrasing falling out of favour by the late Seventies, over-shadowed by Disco and Pop hits, the Eighties only yielding one minor hit for the group with “Love Overboard.”

While her Sixties masterpieces have been sampled by the late J Dilla to 2000s rapper Freeway, I’m not sure that her vocal phrasing or songcraft has influence on the current generation of singers, and a choice for her would signal a traditionalist desire to return to the classic sound of Soul music, which might not be such a bad thing all things considered.

Ms. Patti LaBelle has been around just as long as Gladys, and, truth be told, is the voice I am slightly biased towards when I think of R&B. her voice contains a range of voices, from the high-pitched screams of adoration of “My Love, Sweet Love” to the hot scat at the end of “You Are My Friend.” Her voice is a sweet glue that powered her group The Bluebelle to early Sixties hits like “I Gave My Heart To The Junkman” and “The Wedding Song,” which helped to standardise the Rhythm & Blues genre in the process.

What she is missing is notable songs between 1966 and 1974, when Soul music was in heyday, with hits by Aretha, Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye. As a Pop culture figure though, she has endured, her songs covered by Christina Aguilera and sampled on classic Rap songs by Outkast and Nelly. Her voice is instantly recognizable, still a mainstay on quiet storm radio, an elemental thread in the perception of Soul music today. Her ad libs at the end of her hit “If Only You Knew” are legendary, each syllable coming hot and incandescent from her throat into our ears.

If you were looking for a queen that can bridge the old and new idioms of Soul then you would be looking for Chaka Khan. Rising to prominence with funk band Rufus with the number one hit “Tell Me Something Good” from 1974, producing 12 top 20 R&B hits with the band.

As a solo artist she was on the cutting edge of R&B, utilising the latest drum machines and synths, like on number one Pop hit “I Feel For You,” and on “Through The Fire,” famously sampled by Kanye West. Khan’s voice is an electric and druggy funk, perfect for the weird 70s and the messed-up party of the 80s. I love how she phrases sorrow and wonder, with yelps and deep layered harmonies, her wild voice writhing like the untamed want underneath Soul music itself. While she isn’t as big of a household name as others on this list, none of them were as adventurous with their sexiness as Chaka.

From her debut “What’s The 411?” Mary J Blige was a generational talent. The rough-hewn vocals expressed a working class anguish and joy that connected with young Gen X Black women looking for an alternative to Whitney Houston and Anita Baker. With her 1992 number one hit “Real Love and her hit “Be Happy” from her sophomore album, she fit in the pocket of those Hip-Hop drums, threading her runs around them.

Of the women mentioned here, Mary J Blige has consistently been on the charts the longest, a presence though the 90s, 2000s, 2010s and the 2020s with her latest album “Good Morning Gorgeous.” She had early 90s rap trendsetter Grand Puba on her debut album and buzzed-about rappers from the Griselda label on her latest. While she was not active during the 70s zenith of Soul music, Blige knows where her voice is most effective, and always has her finger on the pulse of current music. Could it be she is the queen our 21st century needs?

Aretha’s death hit me harder than I thought it would, for reasons I outlined here, but the vacuum she left has been felt as well when it comes to the state of R&B. Does it return to conservative roots with a play to its true strengths of musicianship and gospel-esque ad libs, or does it embrace the brave new world of technological improvements, production and vocals that create a ‘vibe’ to be mixed into streaming playlists? Well, only a queen can answer that.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Id and the Super Ego, part one of two

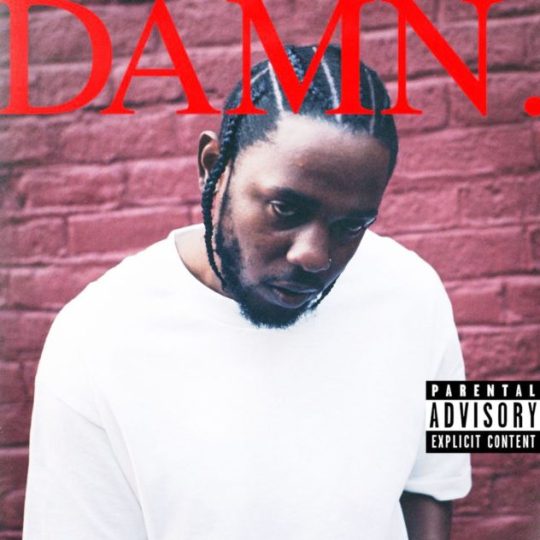

A look at Kendrick and Drake’s latest albums, and the links between them.

“I come from a generation of home invasions,” Kendrick confesses on “Father Time,“ presenting the framework he had to deal with in the environment of his youth, that between prey and predator. The individual in relation to the surrounding environment created the drama of Kendrick Lamar’s albums, from Section.80 in 2010 to DAMN, his 2017 offering. Meanwhile, Drake made sure that Drake was the problem and solution throughout his albums, from 2010s “Thank Me Later" to the present day, where his Megan Thee Stallion drama and overt honesty even overshadowed his joint album with rap star 21 Savage Her Loss. The two rap artists have been compared to each other over the past decade, the different approaches to rap and production becoming more pronounced the bigger each rapper’s renown until they became, as I stated in a 2013 review of Drake's Nothing Was the Same Again, the Eastern and Western emperors of the Roman Empire-like Hip-Hop genre.

For better or for worse it appears that these two rappers will be linked together for the foreseeable future, both for the intensity and global reach of their fanbases. It has been a well worn analysis of the two to view them through the lenses of polarities: Kendrick representing the introspective, philosophical warrior poet, and Drake the aspirational, indulgent playboy. King David or Solomon, Captain Kirk or Spock, you get the picture.

Throughout their songs the two charted their differing, circuitous rise through rap infamy, the one blasting out every mall, car and radio, the other in every earphone and group chat thread. It’s become biblical at this point, like Jacob and Esau territory, each artist thinking of themselves as the warrior, and the other the calculating usurper to rap culture’s Isaac-like blessing, each fanbase thinking the opposite. As much as we were shown the detailed, fitted, custom-made wardrobe and car manufacturers of their lives, we were left out of the examination of how these men were dealing with this Dionysian parade, and how their actions mimicked and orbited each other. Until of course, the normally reserved Kendrick decided to spill some beans.

With Drake’s Honestly, Nevermind and Kendrick Lamar’s Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers, what these 2022 solo albums from the two reveal is their fingers on the disparate pulses of America, and yet it also reveals just how similar and linked their concerns are, only expressed in their well established voices, almost as if instead of occupying distinct lands, the two are from the same body politic, Drake expressing the raw, reactionary urges as the Id of rap, and Kendrick the reflective, considered ruminations of rap from the Super Ego position, the same lusts and ambition snaking through both albums.

We may not know which way to go, on this dark road

All of these hoes make it difficult

Affairs are events that are simple to describe, but difficult to explain. The who and the where tumble out easy enough from a sordid tongue, but the why is something else, as if it has roots embedded in the person, or in fact is a boulder in front of a tomb of memories. It is appreciated then that Kendrick doesn’t overwhelm Mr. Morale... with these admissions, this steaming tea, but instead with a list of numbing material indulgences accrued since his impoverished days of Compton, indulgences that help him to “grieve different,” or to exorcise the ghosts of his traumatic youth.

In fact, this sprawling double album, in particular Disc 1, is occupied with inventorying our objects of desire, from “the Dolce…the Birkin" and “weird ass jewelry” he urges us to take off on single “N95,” the “Rolox watch I only wore it once" of “United in Grief,” he even champions his “rich spirit, broke phone" in “Rich Spirit.” While these possessions are presented by his Super Ego as detritus from his therapeutic excavations, they should also be looked at as the apples of his Ids eye, variegated jewels in the crown he felt deserving of the King of Rap, chief of all jewels for the Black man in the Western world, that of course being the white woman.

“Worldwide Steppers,” the thematic centerpiece of Disc 1, is an idiosyncratic song. On the first couple listens it feels less like a Kendrick song and more like those curious Q-Tip solo songs at the end of A Tribe Called Quest albums, like “What?” from 1991s The Low End Theory, or “Ego" from their 2017 comeback album Thank You 4 Your Service, We'll Take It From Here. The spare, hermetic beat, based around an organ sample from 70s band The Funkees, bounces and jives, while Kendrick half raps thoughts and memories, proclaiming at one point about his children “life as a protective father, I’d kill for her/my son Enoch is my part two,” in that skittering, rambling style, sounding the way men do when they hold on to the blunt for too long.

Then he starts listing his White women, the way men do, with that casual, vulpine pride. The first one he describes “She drove her daddy's Benz, I found out that he was a sheriff/ That was a win-win, because he had locked up Uncle Perry, she paid her daddy's sins.” You usually get a smile and a dap after tales like that. Instead, after recounting the second one, a Copenhagen white, he goes on, ”Whitney asked did I have a problem/ I said, ‘I might be racist’, ancestors watchin' me fuck was like retaliation.” It’s a striking moment of race-infused, shameful self reflection in the face of confrontation, a line we never expected Kendrick to utter, while that organ thunks away at us like our heartbeats do, laying hot on the bed after the affair.

Kendrick continues this excavation of the self throughout the album, and it heightens the songs on the album in a way that his 2017 effort DAMN didn’t, even with it’s rumination on death and violence. He sounds like he went through the same evaluation most of us did through the pandemic, deciding what was important and what needed to be jettisoned. By Disc 2, the Morale section, he becomes more realistic and sure-footed about his situation, musing over the guitar strums of the revelatory “Count Me Out,” that there's “masks on the babies, mask on an opp, wear masks in the neighborhood stores you shot.”

The album revels in these homespun philosophies, but the medicine doesn’t always go down smoothly, grinding to a crawl on the plodding “Crown,” and the voyeuristic family confessions of “Mother I Sober,” among others, but hey double albums are always stymied by their indulgences, and lauded for their welcome surprises. And these realizations come more boldly as Kendrick exits out the other end of the crucible of himself, like on the swaying closer “Mirror" where he’s saying about Whitney “jokes and gaslightin', mad at me 'cause she didn't get my vote, she say I'm trifflin'/ disregardin' the way that I cope with my own vices,” and then he turns to us, hand on the shoulder, both parties wiser for the journey, rap singing “I trust you'll find independence if not, then all is forgiven/ sorry I didn't save the world, my friend I was too busy buildin' mine again.”

The Id and the Super Ego part two can be found here

#music#rap#music review#hip hop#kendrick lamar#drake#hiphopmusic#long reads#mr. morale & the big steppers#the id and the super ego

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Id and the Super Ego, part two of two

A look at Kendrick and Drake’s latest albums, and the links between them.

The Id and the Super Ego part one can be found here

I found a new muse, that’s bad news for you

Drake on the other hand, needs no excavation, as he famously wears his heart on his sleeve, when it isn’t carved into his head. Throughout the decade the singer/songwriter rapper documented his life, focusing on two major themes: his rise to the top of rap stardom and his restless love life. Through songs like the minimalist hit “Marvin’s Room" from 2011s Take Care and “March 14th" from 2018s Scorpion, he painted voyeuristic exposes about his past loves and his estranged son respectively, garnering derisive labels of ‘sensitive’, ‘soft’ or ‘emotional’.

For his actual fans it was fascinating and compelling. Rarely did the rapper with the number one spot in the overtly masculine genre reveal their life like this. Really, what did Melle Mel tell us about his love life? Or Rakim? Or Cube? Jay Z himself waited until his third decade of albums before he pulled the curtain back. With Drake, this lack of a filter endeared him to his worldwide audience, and because he talked about the easily relatable aspects of the human experience- that of falling in and out of love- he could grab his fanbase by their heartstrings and their Id and never let go.

On Honestly… Drake continues this oversharing in songs, regaling us with his tales of excess riches and exhaustion over love, this time over kinetic, nocturnal house and dance beats, the words not studied and rapped, but sung unimpeded and untethered, as if lucid dreaming through an album. On “Sticky,” anchored by door-slam kicks and anxious hi-hats, he is relishing his assholia, blithely disposing his women like a Saudi Sheik, or forget-me-not petals. He crows “King of the hill, you know it's a steep one, if we together, you know it's a brief one/ back in the ocean you go, it's a deep one,” expressing his puerile passions with the same acuity as Kendrick on “Worldwide Steppers” when he reveals “silent murderer, what's your body count? Who your sponsorship?/ objectified so many bitches, I killed their confidence.” It’s the same transgressions, except Kendrick is reflecting on the past, while Drake takes us with him to the sweating moment.

His indulgences are entertaining, but his naked longing is more compelling. His approach to songcraft here never explicitly explains how he always ends up the bachelor looking for a bachelorette, or explores how it effects him, but, in a sense, the music reflects his mind state. Basslines are deep and ponderous behind the stalks of four-on-the-floor kick drums, while the pianos are moody, rain-speckled chords. Songs like “Massive" and “Falling Back" are the hypnotizing daze you would dance the night away to in New York’s Webster Hall or some basement party in order to get over a break-up. It’s house as cosplay sure, but in some cases the music gets the point across better than Drake’s lonesome digi-warbling could alone.

We manage a moment of clarity on “Flight’s Booked,” a late-album highlight soaked in the same midnight vibes, centering itself around a classic Marsha Ambrosious sample. Drake is lovelorn and undone, singing a tender tale of holding onto a love his life can’t bear the weight of at the moment. He sings “although there's distance between us, there's no place I'd rather be, I owe you some hospitality, and it comes so naturally/ promise, I just need some more time if you can bear with me.” It’s endearing really, but you get the sense that she will be the one to respond back in the ocean you go sir, it’s a deep one.

But a mask won't hide who you are inside

Look around, the realities carved in the lies, wipe my ego, dodge my pride

The immutable truth of ourselves lays with us in the valley, between the monuments of the persona we greet the world with. And even when the artist or celebrity inflates this persona to the size of a myth, glimpses of truth find their way through in fits and starts. With Mr. Morale…, Kendrick Lamar shepherds these truths into a grand drama of himself and the events that made him the mythical hero of the shire of rap music, a persona he had clearly gotten tired of hiding behind. The album both shines from this honesty and is hamstrung by the unevenness it causes. Really, is this how anyone wanted Beth Orton from Portishead to be utilised, swallowed by self-pity instead of defiantly belting her heart out? As fascinating and visceral as “We Cry Together" was, is this the type of Alchemist beat we wanted Kendrick over? But it reminds me about what the Good Book says about the truth in the scroll, that about it being sweet to the taste but bitter in the stomach.

Drake reveals his truth as well, in slivers of misogyny and churlish boasts, or in slipped out confessions and his unthinking yearnings for real connection through the myth of himself, across his cavernous, meaningless mansion. If his divisive Honestly, Nevermind reveals anything about him, it’s his deep love for the genres of r&b and house, as well as their function of charting the moods leading up to and away from falling in and out of love. In the context of his turbulent, beef-mottled rap career, his love songs themselves were muses about his transient muses, and this album, much more consistent than Kendrick’s, revels in these affairs. They are precious, underwritten things though, tossed-off melodies about indelible loves and groupies over muscular dance beats, the ear candy of the summer, but candy nevertheless.

These two artists, linked by ambition and circumstance, represent two different modalities of rap music, one existing to move the crowd, the other wanting to move the crowds mind. If you asked Drake fans his best songs they’d list singles, controversial diss songs and immaculate late-night driving songs. You ask Kendrick fans and they’ll tell you about his thematic closing songs, his sprawling, epic centerpieces, his tender biographies. Even their choice of bling is telling. Drake recently unveiled his chain titled Previous Engagements. Designed by famed jeweler Alex Ross, the piece consists of 42 stones totaling 351.38 carats, embedded into 18K white gold, representing the 42 women he considered marrying. Kendrick meanwhile, appeared in performance wearing a diamond encrusted literal crown of thorns by four craftsmen from Tiffany & co. The crown has 8000 cobblestone diamonds totaling 137 carats. The two pieces are both about love, but the two different manifestations of it, that of the material flesh and of the eternal spirit.

Remember though, these two lads aren’t really that different in a certain light. At their core they’re two rappers who found their lane and deliver product to a fan base attracted to the persona they present to the marketplace, same as Nas and Jay did before them, same as Rakim and Kane even earlier. However, Kendrick’s carnal urges read more like Drake’s lines sometimes, while Drake on “Flight’s Booked" sounds like the long distance musings Whitney might hear from Kendrick himself. Over these essays they have been compared to an Id and a Super Ego, famous psychological categorizations first developed by Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud, whose theories have fell out of fashion in modern times.

Consider then the work of Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, who believed the psyche consists of the ego, the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious. What if the two are simply mining their personal unconscious, (Kendrick digging deeper quarries of course) and, in expressing their truths in these songs, tap into the collective unconscious of rap? Drake presents to us our romantic, egotistical desires while Kendrick the spiritual and reflective, but up to a point. For within the fuckboy shell of Drake's tales is a human need for connection with another real human, and the catalyst for Kendrick’s emotional and metaphysical self-reflection is his coming to terms with his destructive addiction to the flesh and to his image. What we can learn from these two curious B-tier albums then is that our polarities, positive and negative, feed off of each other ultimately. We can acknowledge in the valley then, that to deny the earthly desires that reside within us, is as ill-advised as denying the savior that lives there as well.

#music#rap#music review#hip hop#kendrick lamar#drake#hiphopmusic#long reads#honestly nevermind#the id and the super ego

1 note

·

View note

Text

Kendrick Lamar discography review

Section.80 (2011)

***1/2

An assured and confident debut, the album shines when it's at its most focused. Highlights include "Ronald Reagan Era," which sets up the chaos and violent energy he was brought up in, both beat-wise and lyrically, and "HiiPower," an anthem that challenges you to rise above your conditions and "build your own pyramids." In between though, there are sleepy experiments like "Chapter Six," which sounds like an Outkast throwaway, the subdued observations of "Poe Mans Dreams" and "Hol Up," which is more peppy fun than substantial. Still, Section.80 is remembered by its heights and the potential of the young rapper buzzing around the verses of these songs about Compton, the main context of his later albums.

Key tracks: HiiiPower; Ronald Reagan Era; Ab Souls Outro

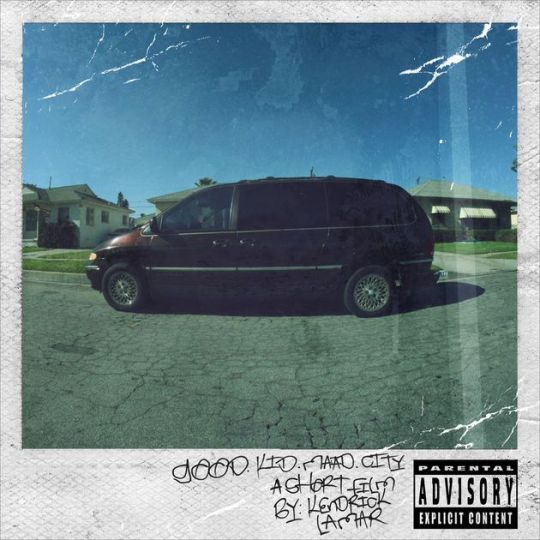

Good Kid MAAD City (2012)

*****

This album remained indelible and unique throughout this decade because, like the Notorious BIGs Ready To Die (1995), it is a storytelling album where the pieces are just as equal as the sum of the story. The peacock singalong of "Backstreet Freestyle," the dreamy hymnal of "Bitch Don't Kill My Vibe" and one of his best singles, "Poetic Justice" with Drake, are all classics that transcend the coming-of-age story. In album highlight "Sing For Me, I'm Dying of Thirst," the lyrics are raw, emotional, centered on death and spiritual redemption, the beats are mournful and grumbling, while reel to reel tape flickers throughout the epic, rendering the song, the story, and the film it's painting in our mind perfect and balanced.

Key tracks: Backstreet Freestyle; Poetic Justice; Sing For Me, I'm Dying of Thirst

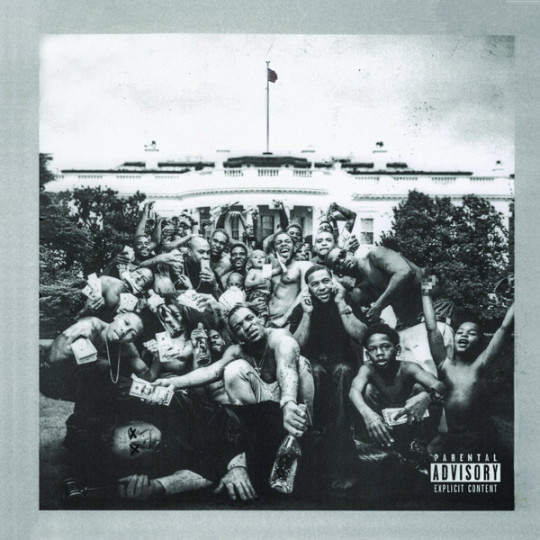

To Pimp a Butterfly (2015)

*****

Dense with ideas and textures, this 2015 set is steeped in Jazz saxophone squalling across the songs, with thick basslines anchoring the majority of the songs, and harmonies swooping and swaying every now and then. "King Kunta" shakes its butt back and forth, "Mortal Man" ruminates like a cloud, while "These Walls" does both at the same time. Obsessed with blackness in all forms, from Pac to Mandela to the homeless man on the curb, Kendrick unveils these characters with new flows and voices, while the crew of producers make it "sloppy, like a Chevy in quicksand," creating something unique, warm and proud in the process. Widely considered a classic rap album of the decade.

Key tracks: Wesley's Theory; Mortal Man; Alright; The Blacker the Berry

untitled unmastered (2016)

***1/2

A collection of leftovers from the To Pimp a Butterfly era has it's own singular charm, dressed in Pimp's sophistication of Jazz-rap squall without all the stuffy importance. "Untitled 2" is a moody seance, Kendrick rapping images of divination over a brooding trap crawl, and "Untitled 5" is the closest to the Jazz-rap sound of Pimp, with a cool verse by labelmate Jay Rock, the beat littered with piano and saxophone runs. Untitled's lack of a unifying high-minded concept is its strongest feature, it's Kendrick without some of the overwrought themes that stiffen some of his later albums, "you be in your feelings I be in my bag you bitches," he crows on "Untitled 7." What this means is no towering classic song on the set, even as it satisfies as a whole.

Key tracks: Untitled 7; Untitled 2; Untitled 5

DAMN. (2017)

****

A far more conventional album than the Jazz-infused To Pimp a Butterfly, the textures are laced together and more palatable here, with the hermetic groove of "FEEL" followed by the shiny confessional thump of "LOYALTY" and so forth. Kendrick is at the top of his form, dealing with rivals on "HUMBLE," recreating the pot-boiling terror of a belt-wielding mother on "FEAR," and conjuring a tale across states, family and time frames, co-starring a gun and a chicken shop, on closer "DUCKWORTH." A unique grower of an album that comes off as his It Was Written, a follow-up to a classic too chart-minded for it's own good.

Key tracks: DUCKWORTH; XXX; DNA

Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers (2022)

****

A fascinating and immersive look at a contemplated life-in-progress, accomplished in a raw yet sophisticated turn, bringing to mind Jay Zs 444 from 2017 and Marvin Gaye's 1978 divorce album Here, My Dear. These confessionals, while eye-opening, can slow down the momentum of the double album at points, like with the lethargic "Mother I Sober" and "Rich Interlude." When this balance between music and message is just right, you get the kinetic, descriptive "United in Grief" and the restless brilliance of "Count Me Out," two of the best songs the Compton, California native has written.

Key tracks: Count Me Out; Worldwide Steppers; United in Grief

#rap#hiphopmusic#kendrick lamar#hip hop#to pimp a butterfly#mr. morale & the big steppers#music review

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

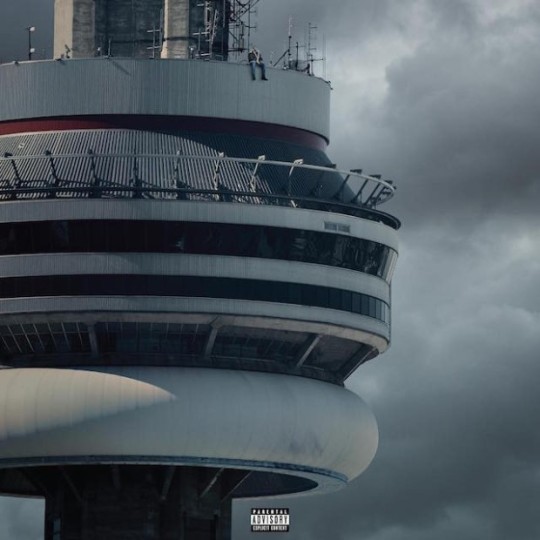

Drake discography review

Take Care (2011)

****1/2

"They love me like Prince, the new kid with the crown," Drake dryly crows on "Cameras Good Ones Go," a lumbering, synth-washed epic that, while not impressive with his melodies or chorus, stay in the hazy pocket of the nocturnal synths. It also directs the sound of the rest of the decade. The echoed confessions over moody keys were pioneered by Kid Cudi, Kanye West, The Weeknd and now Drake and Noah '40' Shebib. Songs like "Crew Love," the sparse drama of "Marvin's Room," the erotic, prowling "Make Me Proud" and "Practice" all revelled in sex and drug-laden encounters, all awash in imprecise and carnal 'vibes.' In certain quarters the album is seen as a millenial classic but ultimately overstays its welcome, and his rap bangers are mostly unimpressive on his part other than the strutting and hot "HYFR" with Lil Wayne.

Key tracks: Marvin's Room; Practice; Crew Love

Nothing Was The Same (2013)

****

Drake's strongest draw is how he included the listener in his ascent, his details of designer brands and foriegn flights felt less like braggadocio, but more like sign posts to check for in a voyage to prosperity. His transformation from up-and-comer to a king of rap was complete by this album and the songs reflected this. "Worst Behavior" and the epic grandeur of "Marble Cake" were the soundtrack of the black excellence wished for in the Obama years. The single from this, "Just Hold On(I'm Coming Home)" is a crafted gem of a song, lightly personal ("you act so different around me") but generally universal, a portrait of a man in control of his loves and his life for the time being.

Key tracks: Just Hold On; Tuscan Leather; Worst Behavior

If You're Reading This It's Too Late (2015)

*****

While this project might be the start of his tossed-off, meme-able album cover trend, this is a serious and integral part to Drake's musical offerings. When old heads think the rapper is singing too much, or college kids think he should drop a real hit, those disparate opinions revolve around the gravity of this 2015 set, when the sound of rap revolved around him. These Boi-1da, 40 and Wondagurl beats he rides comfortably and with a controlled rapping style. "Energy," the catchy boast "10 Bands," the seductive, growling "Company" (with then new star Travis Scott), the cosmopolitan sway of "Preach" with Partynextdoor, were all evocative, boastful songs with ear candy choruses and they comprised the sound of youth culture in America at the time. The respectable and conscientious To Pimp a Butterfly was ultimately a selection of rap album of the year from the electoral college of black culture. If it was left up to the popular vote, this album would have been chosen. All the different trends up to that time, from trap to chill wave, had Drake's finger on their pulse, leading to labels of culture vulture and of ghostwriting, but, the somber truth is that the omelet is never judged by the number of eggs cracked in the process.

Key tracks: Know Yourself; 10 Bands; You & the 6

Views (2016)

***1/2

The frustratingly inconsistent and overlong album cements the rapper on the top of the streaming charts from the twenty tracks and tacked on hit "Hotline Bling." What Drake's lack of quality control obscures is a breathtaking midsection. Over six or so songs as many styles are displayed, from down south drive rattle like "Faithful" to trap drawl in "Still Here" to the melodic world dance pop of "One Dance" with Wizkid and Kyla. The themes are the same, a look into the life of a brooding prince falling in and out of love, but maybe it's too studied, like how the Rhianna song here, "Too Good," sounds just like a Drake and Rhianna song should sound like, without demanding more. This oddly makes Views a good entryway album into Drake.

Key tracks: One Dance; Controlla; Feel No Ways; Hotline Bling

More Life (2017)

****

Initially written off as a content dump like its predecessor Views, this album/playlist has aged handsomely, establishing itself as a recurring soundtrack to our summer escapades. "Passionfruit" is a bright lounge classic, paving the way for the explosion of afro pop and campo today. "Blem" is nocturnal and oversharing, while "Glow" with Kanye West, is sprawling and relaxing. Between Drake being Drake though, is an international zeal that adds texture and unpredictability to the set. "Madiba Riddim" is tender and swaying music while "Skepta Interlude" is dense and industrial. Drake maintained his hold on pop and rap, even if this eclecticism was more of an aesthetic than inspiring.

Key tracks: Madiba Riddim; Blem; Passionfruit

Scorpion (2018)

***

An album that showcases the polarities of Drake, due to the double album becoming inflamed and muscular due to a brutal beef with rapper Pusha T. His most hardcore and steel-toed songs are here ("8 out of 10", "Emotionless") couples with his most breeziest ("Summer Games", "Ratchet Happy Birthday"). While the set has one of his best singles in the rousing fem anthem "Nice For What," the most interesting part of Scorpion is the drama and context surrounding it.

Key tracks: 8 out of 10; Nice For What; In My Feelings

Honestly, Nevermind (2022)

****

The house beats are less flashy and glitchy than the ones on Beyonce's summer release Renaissance, mostly here the songs are grumbling basslines with synth figures echoed and repeated. It fits with the lonely ballads he usually makes with producer 40 Shebib, a dance with the forlorn heart of the party. Even in the middle of the heavy dance heat of "Massive," Drake sings "I don't want to go." He sounds cold and autotuned, tempered and unknowable.

A touristic visit to a historied subgenre much in the same vein as David Bowie's 1975 album Young Americans and Madonna's 1994 R&B romp Bedtime Stories. The attempt to dip into house and dance mostly pays off because it plays to his strengths of melody and letting the phrasing emerge from the feeling the track elicits. In "A Keeper" he turns a taunt to a lover into an ear candy chorus twisting around the house thump. "Currents" sounds like an overheard half drunk call, and the idyllic first half of "Calling My Name" is less song lyrics and more the stuff you muse about looking out of windows. The album feels immediate, as if recorded in a couple of days, as if nothing was written down, and that improves it, even if it means no lyrics with wordplay and insight. It's this wide-eyed gut reaction to everything: love, the future, fame, that pussy calling his name.

Key tracks: Calling My Name; Massive; Flights Booked; Jimmy Cooks

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Thrill, by Wayne Snow, from Figurine

youtube

Ultimately, an artist tries to search for, and excavate, parts of themself through their art. Producing items fully and solely to reflect the demands of the market can only responsibly be called a craft. Meaning, with art, the artist must at some point peak through under the caul of aesthetic.

Influences, obsessions, memories, fears and loves get thrown into the piece until all is set and settled. Over time, the art piece remains a kind of star map to the universe of the artist. Take Wayne Snow, a Nigerian born singer-songwriter and visual artist based out of Berlin, Germany. He is currently touring Europe behind his impressive debut album Figurine, from last year.

Centered mostly in the idiom of Soul and R&B, Snow's influences and inspirations spill over the album, videos and accompanying artwork. "Faceless" is anchored by a cool, mysterious scat and a booming dance thump. The song plays with tension and release, expressing and phrasing the intoxicating moments when love and desire derive out of the dark magus. "Love is faceless, the same for everyone," he observes.

Meanwhile, "The Thrill" is a cool groove recalling not only D'angelo (a stated influence), but Instant Vintage-era Raphael Saadiq on the sharp guitar work, and with "Figurine" Wayne shines over a drum break and agile bassline, joined later with a furrowed synth, an echoed space throughout the song as Snow wonders "who's gonna carry me?" There's a clean sophistication here in the vein of SOHN or James Blake, a jazz piano gathering up the end of the song with a warm solo.

The different approaches to sound never distract from Snow's singular character and voice, and the same dynamic is with the album artwork, the stark figure recalling ancient Malian portraiture and sculpture, or perhaps mid-eighties Grace Jones album covers. Snow prefers bold colours, alert lines overlayed with observed details. These different factors show a different approach to R&B from the drugged-up, nocturnal vibes of today's singers, dotting the album with delicious moments like the final coda "FOM" or, like on "Number 1," when the dynamic humming riff shifts into a cool choral, leaving a deepened tone, and a new way to look at this artist's portrait.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

“Magical,” by Laura Mvula from Pink Noise

A curious millennial once asked me what the 1980s really was like, and immediately I opened my mouth to prattle on about the magic of Michael Jackson and Prince, or about the kaleidoscopic glare of bright jackets caught in the neon lights, or the movie and television screens inflating entertainment personalities into immortal superstars. However, the more I truly contemplated the question, the more I realised that the eighties only resembled those moments in palpable bursts during electric peaks, and I realised furthermore that my bronzed memories from then were couched in far more peaceful, pastoral years and sounds than the garish swash in the background of marketed 1980s iconography lets on nowadays.

Compared to the non-stop pace of today's internet age, life in those days was slower, the rush towards new technology allayed by a clash against long-standing values, I mean the whole place was just imbued with religious commands, symbols, or sayings.

And across that slow tension, your eyesight was just more tessellated with the textures of decades prior.

Everywhere you looked there were people, still wearing clothing from the seventies, getting into Datsuns from the sixties where their AM radio stations played Sam Cooke songs from the fifties. Memes and dances from commercials and sitcoms stuck around for years not weeks and, because of the lack of constant connectivity, the very real fear of nuclear annihilation wasn't even as pervasive as our modern concerns about terrorism or pandemics.

Artists nowadays have tried to capture the feel of the cultural memory of that aesthetic-rich decade in their albums, to just slip it on them sleek like a jacket, most notably Taylor Swift with 1989 from 2014, The Weeknd’s After Hours, from last year, and Coldplay’s Peter Gabriel-esque pep on their recent Music of the Spheres album. Overall, they leaned heavily on the industrial neon glare and synths of the decade, and less on the spaces in between, where we all would take a collective breather.

Each of those albums accomplished the aesthetic goals they attempted, and they draped their best songs in that approach. Looking back now, through the narrow yet fertile valley of memory, I can see that the context, or the width of a culture, is as important as it’s heights. And so, for a more catholic representation of that storied decade, I'd point towards Birmingham, UK singer-songwriter Laura Mvula's latest album Pink Noise.

Mvula's 2013 debut Sing to the Moon, (reviewed here) was a tender beauty of an album, floating on a cloud of choral harmonies, horns and solemn pianos. Her songs there dealt with self-determination, the searching for purpose, and the gentle embrace of love. Her follow-up, 2016s The Dreaming Room, while less focused, continued her musical back-drop of floating harmonies, nocturnal chord changes punctuated by danceable songs of encouragement and heartbreak, helped along in that regard by legendary producer Nile Rodgers on "Phenomenal Woman." With Pink Noise, Mvula changes this approach, tempering her wistful, searching harmonies, and buttoning down the lyrics of her wandering songs of love into punchy, clear-eyed synth pop and r&b. This risk is rewarding for the most part.

“Church Girl” grooves with a stinging snare, harmonies that sway with and against each other, garnished with synth sparkles on the chorus. It’s a swaying, entertaining update of Who’s Zooming Who-era Aretha Franklin, with Laura ensconced in wonderment and concern in the middle of the dance floor, asking, about a love or maybe the music industry itself, "how can you dance, with the devil on your back?/ how can you move? Caught up in a picture perfect that will never last?” Meanwhile, closer “Before the Dawn" is an encouraging anthem that switches between two tempos and moods of electric pop, at one point recalling the high-powered synths of Lionel Richie and Cameo, and then gearing down into the strutting encouragement of a Chaka Khan ballad, all in four or so minutes.

Producers Dann Hume and Troy Miller excel at transitioning Mvula’s songs and swirling lines into these nostalgic textures. The song most reminiscent of her debut, “Golden Ashes,” is layered in sparkled synth notes attempting to balance the Mvulian minor chords. The song would have brightened up The Dreaming Room, but here it is a sleeping album track, indicating true growth is taking place instead of plastic cosplay. The song softens the middle section of the album, along with "Remedy," with its percussive synth lines, and soft chorus in the middle.

Notably though, these songs do not distract, because the interesting and socially conscious lyrics are caught in the type of synth romp that, upon reflection, typified most songs of the eighties. You see, what plays on digital stream playlists nowadays are the starting lineup of that decade, but the vast musical soundscape of the eighties consisted of songs like these. The album tracks on Wham!, New Edition albums or the myriad movie soundtracks of the era will produce the same musical template.

Meaning, what the sound of the eighties really sounded like, was a menage of late seventies disco hits, Pop vocal power ballads, Reggae lover's rock, Rock hits, and these new wave synth pop dancing songs. There were a bunch of songs that didn’t need to knock it into the stands every time, they just took their time, and found their rhythm.

While there was less neon exuberance playing than the present-day nostalgia of the eighties leads you to believe, there still was an aesthetic of ‘new' in a lot of the media, packaging designs and culture, so I believe that the true feeling of that strange, singular decade was mostly expressed in the synth-laden ballads of Luther Vandross, Atlantic Starr, or Evelyn “Champagne” King that replaced the lush, dense quiet storm staples from seventies soul singers Smokey Robinson and Teddy Pendergrass. That electric sentimentality that came from the throats of everyone's sisters, younger aunties and girlfriends.

It is for that reason that Pink Noise's true highlight is not only the high powered swing of the impressive single "Got Me," but also the towering ballad "Magical." The song finds Mvula trying to mend a frayed romance by utilising the best motifs of the eighties -chucking rhythm guitars, timpanis rolling into the chorus, ponderous synth squats, and a chorus billowed by naked sentimentality, with bright trumpets appearing at the end, played with pomp and alacrity. The song brightens the back end of the album with a steady glow, flourishing character into Pink Noise, the hot midday sister to the furtive, nocturnal Sing to the Moon.

So then the eighties, the eighties. The truth is that thankfully there was less self-aware irony and branded sophistication of the self. Less emphasis on being seen and more on what you were seeing. So much so that you didn’t know the eighties was a thing until the moonwalk. You didn’t know it was over until the Cosby Show was winding down and NWA burst through from someplace called Compton. Mvula easily reminds me though, that there once really was this electric groove snaking high and low amongst the church bells and birdsong and the silence. It was coming out of our cars and homes all hot and new, just out there softly couching our memories.

7 notes

·

View notes

Video

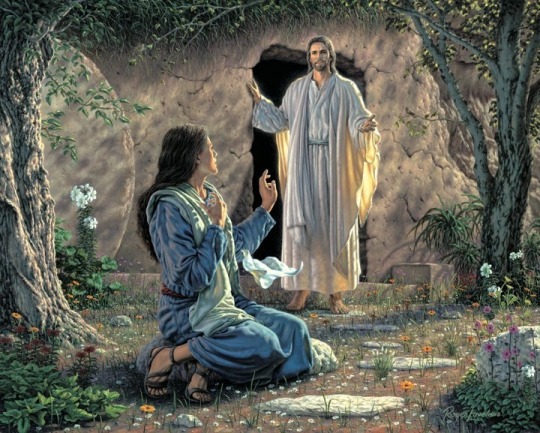

To celebrate the new movie about Aretha Franklin, "Respect," here is a review I wrote on the Sunday after her passing on her classic "Amazing Grace." Shout out to Jennifer Hudson doing her thing.

youtube

Amazing Grace by Aretha Franklin from Amazing Grace

You see sometimes a song is more than what it is. By that I mean more than its functionality, you know, as some sweet words sung to pass the time or some cool verse to rap to. Sometimes songs become amulets, enclosing images of the mind more vivid and pervasive than a picture, or sometimes they enclose the time it came from, the person that sung it, the people who heard it, and you yourself might get mixed up into the song, layer upon layer fused together until it becomes its own shape, its own idea in your mind, fused like it’s an auditory sigil of some sort. Sometimes all this comes rushing into you all at once, at one moment, over one word in a line, mantic on one note, sung by a voice the kind of which you will never hear again.

Aretha Franklin’s rendition of Amazing Grace comes to me like this. Recorded in a Los Angeles Baptist church in 1972, the album the song is from spans two nights of concerts, and is the last of her great performances during her classic Atlantic Records period. First the choir sings their hosannas and the preacher, the affable yet resolute Rev. James Cleveland speaks, and the congregation gets into it, and then Aretha takes the raw, black, atavistic power in a church run, and focuses it with the precision and intention that you get from years in the studios of the top record companies making some of the most important Soul and Pop records in American recorded music. Full of that power, that feeling, like she sings of in the ethereal ascension of “Wholly Holy.”

Then the song starts, and it vibrates and shines with a distinctly human electricity, first from the moaning and understanding organ laying the foundation, then from the affirmations of the choir and bromides that are hooted an’ hollered from the congregation, then lastly from Mrs. Franklin herself, the words coming from her shocked and rising, becoming violently incandescent, tempered only by the control of her voice, steady just like her Preacher father’s hand on the forehead of a worshipping Christian gesticulating and arched in the throes of the Holy Ghost.

Keep reading

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Between the death of Pac in '96 and the ascendancy of Kanye and Wayne in the mid 2000s, there were only two men that could be called rap music's superstar, 50 Cent and Dark Man X.

But while 50 had the persona of the clever criminal, a cad almost, DMX came across as legitimately scary, an expression of the barely contained violence of a hollowed-out America that acts like Marilyn Manson, Linkin Park and Rage Against the Machine reveled in.

If it was this one note of crime rap though, then he would be seen as another violent fix in the glittering Jiggy Age, like Limp Bizkit or Bonecrusher, but the layering of Christianity, temptation, regret, shame and the Devil made him into a singular artist.

His face and voice during those redemptive prayers he would bring from himself, remind me mostly of the Old Testament, in particular of Jacob wrestling the angel. Xs voice wavering under his growls, his prayers would sound like overheard confessionals, his struggle less with the angel Michael or Samael, and more with the agitated angel of himself.

Here he is, holding court at Woodstock 99, giving one of the best live performances I've seen a rapper give, full of breath control and that prickly violence I told you about.

Rest easy now King, your earthly struggle is over now.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

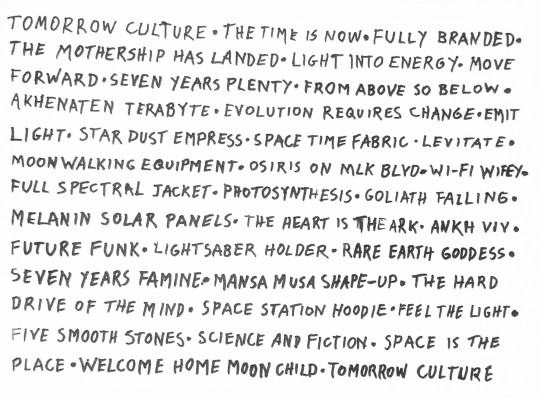

"Precepts(Tomorrow Culture)" by c.bradley.white (instagram: @c.bradley.white)

My collaboration with Wilbert Mcbryde for his innovative clothing brand Tomorrow Culture (@_tomorrowculture) has been fully edifying and imaginative, binding together my literary and visual works.

The challenge was to reflect in words the visual themes of Mcbryde's designs: a stew of sci-fi, afrofuturism, music, sensuality, african history, egyptology, and the connective tissue of space and time.

What this fusing together resulted in was "Precepts(Tomorrow Culture)," a stark yet variegated piece that formed the basis for the advertising copy of the brand. These commands and concepts take their inspiration from not only Mcbryde's themes, but from sources as disparate as the Holy Bible, the booming proclamations of experimental jazz legend Sun Ra, hand-written wing spot posters, and the disjointed stories of modernist writer Gertrude Stein.

I think there is a special, delicate result that comes from minds in congress together to create something new, and inspired. The clothing and accessories are cool as hell, looking towards the future, and rocking those space station hoodies really get me in a mood for creation, inducing the unspoken inspirations that the grand precepts of old were all constructed around.

Check us out on Instagram @_tomorrowculture, and visit website www.tomorrowculture.store where the code "yourculture" gets you 15% off and remember, space is the place.

#blackart#blackcreatives#afrofuturistic#sun ra#black magic#melanin#atlanta#black men#clothing#streetwear

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Carter Trilogy, part five of five

Conclusion: We know the pain is real, but you can’t heal what you never reveal

"Marriage,” Joseph Campbell, Professor of Literature at Sarah Lawrence College, once said in an interview with former White House Press Secretary and journalist Bill Moyers, “is not a love affair, it is an ordeal, the sacrifice of the ego to the twoness, which becomes the one,” and anyone can see that sobering, bone-dry realization in the mahogany roots of any failed marriage.

But that realization can come hot and stinging from a reckoning within the marriage too, one that comes out usually some mournful evening, with a mumbled greeting and then slow, prowling questions, until a lie justifying a confession comes, and then shaking hands and voices would report, hitting on shoulders in the same tempo as the judge's gavel one dodged all those years.

In our grandparents time, they got about three or so reckonings before the thing was up and done with, some of them ol' union-man unions kept on after that, but they got all heavy and colossal the more wet transgressions were uncovered. Nowadays, who knows how many you get, so everyone I know is walking around with their nose all clean, and their fist all balled up.

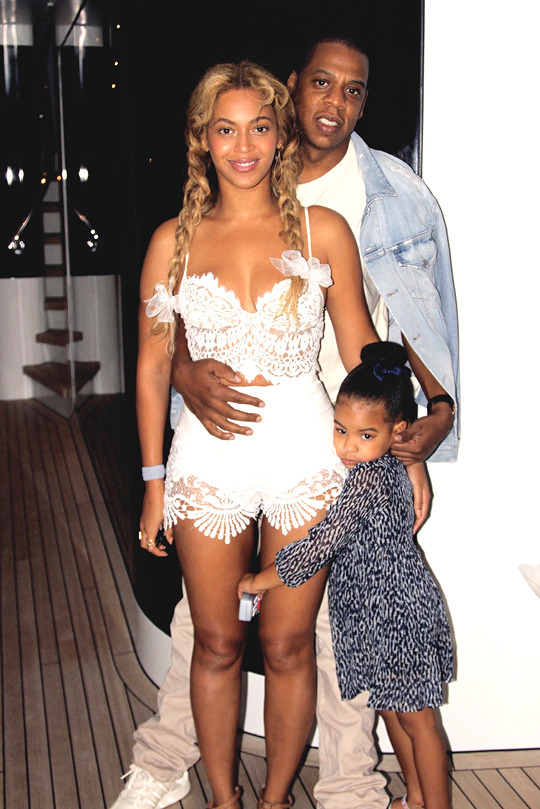

Well, here we had presented to us in real time, a marriage of black royalty that survived such a reckoning. An under-reported yet typical three act play for marriages that usually played out in hushed, violently whispered conversations behind closed doors.

But remember, these aren’t diary entries, this is a years-spanning narrative, told over numerous time zones and of course, numerous UPC bar codes. These aren’t your friends, but instead are black entertainers that slotted themselves into the black consciousness as the couple of note, the way Nat King and Maria Cole, Ozzie and Ruby Davis, or Will and Jada Pinket-Smith did over the generations. They presented themselves as something larger and blacker than they themselves were, the same way we have to continually present ourselves to the eternal pyre of our own marriages.

Meaning, they won’t always get that expression out right in the studio, the same way we won’t always get the words out right during the anniversary night at the island hotel or whatever. Because that feeling you feel in the song is a feeling they took take after take to get right, that beat after beat was forded towards.

Jay Z and Beyonce ultimately monetized their best talents, and created a national conversation on the nature and shape of American marriages, but at the same time left some of their wisened observations and most iconic moments ensconced in dated production, like with 4:44s “Moonlight,” and Lemonade's “Sorry." And let’s not forget that Love Is Everything is as mid as their Bonnie and Clyde collaborations throughout the years promised it would've been.

That’s said, I like how pro-black the two first singles from their albums were. “Formation" got your black noses and fists raised, and commanded you into a shucking, trap jive, while “Story of OJ" was a downbeat groove, a chopped-up, Nina Simone-led basement afterparty to Queen Bey's Black Broadway parade.

And I like the duo on the foot-stomping testimony of “Family Feud,” where Jay reaches across hip-hop generations over Beyonce’s swaying harmonies, Jay accenting his “and old niggas, let’s stop acting brand new/ like Tupac ain’t had a nose ring too,” among the ringing piano.

Later on the song, Jay not only struggles with his household crown, he relates his troubles to Michael Corleone in the opening scene of 1974s The Godfather Part II. “My consciousness was Michael’s common sense, I missed the karma that came as a consequence/ niggas bussing off in the curtain cuz she hurtin', Kay losing the baby with the future’s uncertain,” he says, with unencumbered eyes, while Bey's recurring “higher, higher” swirl around him like curling affirmations. They reconcile the song at the end, reminding you of this black cultural wonder they are, the thing we wanted Whitney and Bobby to be throughout the nineties, these stewards to a possible black renaissance if we can all keep the weight up.

But there’s something that’s missing here across this trilogy. There’s this lack of clarity in the narrative, and that lies mostly with the mercurial Beyoncé. Jay Z is baring his guts here, confessing to affairs, neglect and a lack of empathy from his cold, cold heart, while on the songs across Lemonade and Everything Is Love, there’s a lightness in the confession department, a lack of that one softly thrown line from her that could bare all on the floor.

But you know, maybe I’m being too hard on the Queen, after all, this is just some story being played out of a box by characters that we treat as a couple in the family. When the glowing screen shows me other scenes from a marriage I don't get all constructive and demanding, I just sit back and take it all in. I mean I never really demanded any of this clarity or confession from The Godfather’s Kay Adams, so I shouldn’t from Beyonce Knowles-Carter either.

Although, come to think of it, in those first scenes of The Godfather I always thought it was strange that Kay still fell for Michael after he told her that Johnny Fontane story at the table all calm-like while sipping his drink. She knew he wasn’t gonna go straight right? She knew she was going for a cool ride with this Mafioso didn’t she? I mean why wasn’t she dating one of the other teachers at that school she taught at when he showed up all of a sudden? What was her whole deal in this game? What was she steering Michael to become? Wouldn’t it have been cool to get a couple scenes of her whole side of the plot? I’m just saying though, wouldn’t that have made that classic drama even more grand, even more ill?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Carter Trilogy, part four of five

Everything is Love: we broke up and got back together, to get her back, I had to sweat her

The narrative had been set in cultural stone by the time 2018s Everything Is Love appeared out of nowhere one Summer afternoon: there was the dutiful, overly ambitious wife betrayed, and the profligate, amoral husband, atoned for his sins. While this surprise album finds the bruised and dynamic duo finally together again, under moniker The Carters, the nine song set doesn’t really show us where they want to carry their renewed union, the two content with a measured celebration of love in the sounds of right now.

“713” is alert and engaging, not only with the piano-led boom, but from Jay Zs tale of how he and Beyonce met off-and-on throughout tours and flights, a tentative love forming between hectic schedules, while “Summer” is a cool, relaxed Soul ride produced by Cool & Dre, who give them the type of heavy-bottomed Soul that Wilson Pickett or Bobby Womack sang their hearts over. Here, Beyonce takes stage, strings floating behind some of her gut-bucket runs, suggesting “let’s make love in the summertime, and be in each other’s arms,” while Jay toasts to “let it breathe, let it breathe.”

“Black Effect,” the best song on the set, immerses itself with a booming sway of love and a yearning for black excellence, and it shows the two at their most natural and nonchalant, like Lebron in the fourth when he stops passing and just goes off. “I park my ride at the Projects I’m so reck-a-less/ Extra magazine, hopped off the Jet with an Ebony chick” Jay says, and later, when the drums fall out, and just that sample is echoed into an articulate cloud that abides by him, he says “the FCC, the FBI or the IRS/ I pass them alphabet boys like an eye test.”

Meanwhile, Beyonce cradles the song with yelping ad-libs (I’M MALCOLM X!), swooping harmonies, and this recurrent, resonant mantra of “higher, higher” that fill out and accentuate the secular praise going on. Along with “Lift Off" from 2011s Watch the Throne, it’s her performance that makes these songs their two best collaborations over the years.

It is on single “Apeshit" though, that finds the couple finally foiled by their insatiable ambition. The beat is pure trap energy, however it subsumes them, the song only strung together by the chorus and the violent repetitions and ad-libs from Migos. Jay flounders here, hanging his verse on a toothless Lion King-referencing opener that sounds only like product placement upon reflection, while Bey is muddled and unremarkable with her rapped verse, a couple of designers names slipping out every once in a while.

And their turn on “Friends” is a half-hearted attempt to create a hazy, late-summer stew of memory and cool, the type of twinkle-dark synth stuff Jaden Smith, Drake or Frank Ocean shrug off on a beat in their sleep. Here though, the song comes off cold and anonymous, Jay listing his known cohorts, and mentioning the bond around funerals and gang codes, but the both never delivering a line to express why friendship is truly important.

And although I really like that final run she does on the end of the song, that does not assuage the frustration I feel about how opaque Beyonce is here, relying on flat cliches for lyrics, and providing no real look into her life through songcraft, only through the broad, waving flag of her voice.

Also weighing down Everything… is the Pharrell-produced “Nice," a song that tries to create a jagged, textured jam and let the bass smooth it out, but instead results in a plodding, belabored series of affirmations, made dull with an uninteresting chorus and production, even the back-and-forth between Beyonce and Pharrell only slightly entertains. Somehow, the best line of the album is here, with Jay in the cut of the ringing piano, acutely reminding us “I have no fear of jail, I was born in the trap/ I have no fear of death, we all born to do that.”

Jay has played to his strengths in collaboration, expressing self-reflection and atonement with Jay Electronica in this year’s A Written Testimony, and, most famously, in a black excellent parade with Kanye West in the aforementioned Watch The Throne. On Everything is Love though, he seems compromised, like a dealer trying to get rid of a stash before a deadline, or, yes, like a peccant husband on a make-up. It’s a clear cash-in, like Marvin and Diana was for the floundering mid-seventies careers of Marvin Gaye and Diana Ross, but at least those two had the decency to give us a “You Are Everything” in the process.

Ultimately, like all unions, it’s a calculated union, except remember, this one concerned a billion dollars on an elevator. “Y’all made up with a bag, I had to change the weather,“ Jay says on closer “Lovehappy,“ a back-handed boast, which is then followed by Beyonce riffing on the state of the marriage, as the band and the harmonies swing low, kinda like a sitcom theme, rapping the straight-backed rejoinder like a threat, “in a glass house, still throwing stones.”

#music#soul#rap#hip-hop#r&b#music review#pop#long read#beyonce#black music#jay z#jayz#everything is love#black creatives

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Carter Trilogy, part three of five

4:44: And you stare blankly into space, thinking about all the time you wasted on all this basic shit

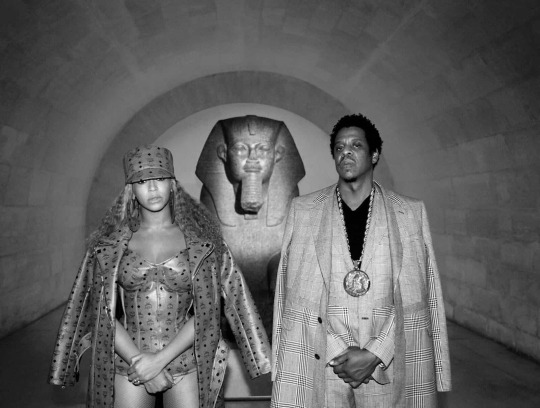

During Fade to Black, the documentary following Jay Zs 2003 farewell performance for a short-lived retirement from rap, this curious thing happens. Between the setups for the performance at Madison Square Garden, and Jay traversing the country to nest with hit producer after producer, a scene appears of Jay, presumably at his Roc-a-Fella records headquarters, asking, actually beseeching, the motley crew of executives, rappers and goons to prod him to talk about the negative effects of drugs and guns in a song, being that he had glamourized them over the course of six or so albums by that point. No resolution to change course was made at that meeting, but the look of Jay Z in that scene was riveting. He looked like a man that wanted some kind, aged woman to hold his face in her hands and tell him to follow his heart. Instead he was surrounded by men only concerned with the bottom line, men he personally chose. “If that’s what they want to hear, then they buy it,” one says.

Then, there’s a moment on the album he traversed the country for, 2003s The Black Album, on the song “Moment of Clarity,” where he says the lines “truthfully I’d rather rhyme like Common Sense, but I did five mil, and I ain’t rhyme like Common since,” once again exposing some type of urge to, I don’t know, tell the world the tumbling and uncovered things washing around in his soul that sounded like the hot whiskey that sloshed around in Nina Simone’s voice, or like Un’s voice that night he was stabbed, or like that trembling awe in Donny Hathaway’s voice when he let go and sang about being free, or that sounded like his wife’s flat voice as she stared blankly into space over the phone. Well that urge, that curiosity, to step outside of the celebrity version that one constructs to present to the world, is found on 4:44.

A stark, bracing look at the life of Shawn Carter, rife with intimacy and triumph are found across these songs, some which show a Jay Z in charge, advising and boasting, and another set of songs that deconstruct the myth of the Rap star at the same time.

Opener “Kill Jay Z” is a series of clear-eyed, accusatory, second person couplets over a panicked muffle of a beat. Confessionals and invective pushed together into lines, not only in the famous Kanye “20 mill” line but also in “you stabbed Un over some records, your excuse was he was talking too reckless,” and “you got people you love you sold drugs to, you got high on the life, that shit drugged you.” It’s the type of shit men say into the shower in tortured litanies the afternoon after a late night bender, a shocking look at a man without his crown coming to terms with himself. The lines come off as strips of ego, revealing a man as used to failing as he is to winning.

Then there is the centerpiece and title track, which along with Cardi Bs “Bodak Yellow,” was one of the best songs a New York rapper released that year, a track that marries captivating lyrics over an equally striking beat.

He uses his voice in subtle ways now, to express shaded emotions, like in “Adnis,” from the set of throwaways-for-a-reason extra CD tracks, where he confesses about his father “you couldn’t kick the habit, wished you had said something,” and over that whinnying vocal sample and those somber piano chords I try to imagine the advice a drug dealer might give to a parent that uses, the karmic kindness he might have met him with.

And on “Legacy” he is limber and reflective, on a coolly lazy chop of some drums and that Donnie Hathaway voice sample I told you about, sounding like Train of Thought-era Talib Kweli. Rapping again about his father, or Father, he says, “I studied muslims, bhuddas and Christians, I was running from him, but he was giving me wisdom.”

First the beat, a joyous chop of some modern Blue Eyed soul from Britain, the swooping runs and hot yelps of the singer swirling into a deep groove, a masterful manufacturing of voice and instrumental bombast that recalls the great beats of J Dilla’s rhythmic juggling of Luther Vandross’ voice in “Airworks,” and Just Blaze’s arresting rendering of Gladys Knights voice on Freeway’s “When They Remember.” The song, and all production here, is handled by Chicago producer No I.D.

He came up producing the first three Common albums with the same multi-bar looping of sounds, with the Common songs focusing on the bassline and guitar of jazz and funk records. But with Jay, his beats has its main characteristics coming from the chopping of the piano, the voice and the soft harmonies of Soul songs, and this song it is said, was done after No I.D. sent him the beat and song to listen to, with Jay listening and then later waking at the titular time to compose and spew his guts out about his marriage and behavior.

Now whether that story is true, or whether it is true for marketing purposes, is immaterial, because the truth and the purported truth both resulted in this resolute, unflinched honesty, these lyrics cutting into not only the mirrored scales of celebrity drama, but into the dermis and flesh of relationships themselves. “I said ‘don’t embarrass me’ instead of ‘be mine,’ that was my proposal for us to go steady,” he says, the admission of a man on top of the Rap world at the start of the millenium, from when he was cocksure and unsure at the same time.

Later, he talks of stillborns, then threesomes and then there is the crushing observation “your eyes leave with the soul that your body once housed,” and then he ends a verse with the prayer of husbands in the quote “I stew over, what if, you over, my shit?”

This is an examination of the parts of a man when he was broken and flailing for control, the myth deflated into an approachable Clark Kent of a rapper, and broken down even more until the mask goes away, until the acknowledgement that Santa Claus is fake, until what results is an aesthetic of honesty, a veteran giving a seamless performance of realness.

There of course is still Jay’s expected brand of braggadocio, the songs that make up the mythical Jay, and that creates the tension of this album. “Smile” finds Jay and his mother rising above their adversaries of career and sexuality over a sweet sampling of a Stevie Wonder classic. “Aw you thought I was washed/ I’m at the cleaners, laundering dirty money, like the teamsters,” he boasts. There’s “Bam” with Junior Gong, where he is at his most alert and violent, surrounded by an angelic cloud of Sister Nancys echoing through the reggae strut. With “Marcy Me,” the rapper is at the top of his powers, each line filled with double entendres and agile flows, the song resonant and dense enough to be the type of track found on a late-nineties DJ Clue tape, and then it starts slowing down and expanding into an epic sprawl, the voices of yesteryear stretched, echoed.

This look at the man behind the throne is what gives a lot of 4:44 its social and emotional push forward. As time has passed though, we see that the album that came with building-spanning pomp and mysterious advertisements, is in reality an insular record, with wisened words cosseted in beats with warm, swirling harmonies. What the Brooklyn, N.Y. rapper manages to do is produce a solid album, not about relishing in cash, money and hoes, but about a life in the wake of those excesses, and about the barbed reckoning in the heart of marriages necessary for them to beat again. I don’t think Jay is haunted by his searching questions from that moment in the documentary. And I don’t think he gets up at four-something in the morning anymore either.

But there’s something that stops me from just calling 4:44 a new classic and an epic comeback like others did upon release. It’s just that, well, I wish this album swung for the fences more. There’s a ton of great album tracks dealing with the knotted distemper of love and of life, but only “4:44” and “Marcy Me” even try to whip any of this up into a frenzy, and I think that is because other than the tangled root of Frank Ocean in “Caught in Their Eyes” and the thick chants of “Bam,” there isn’t much in the way of choruses here.

There is a hermetic groove here, the songs that Jay picked for NoI.D. to chop up included a number of warm Soul records from the seventies. The songs are turned inward most lines, causing him to employ more relaxed tones in his voice, like his drugged, mocking confessions on the foggy “Moonlight.” This works well for some songs to play after some fine Common or Talib Kweli joints, but Jay Z, and his voice, are at their best when they are on top of the world, not coiled and engaging in self-flagellation.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Carter Trilogy, part two of five

Lemonade: Ten times out of nine I know you’re lying, but nine times out of ten I know you’re trying

When I last reviewed a Beyonce album it was 2011s 4 (reviewed here ) , which I then lamented as unfocused, seemingly sequenced by committee, and utterly dependent on production as opposed to proper song-craft. I concluded then that the limping hodge-podge of an album was going to be Beyonce’s last okay album, and from there on it was going to be a calculated subsuming into a digital and anonymous cloak of modern production, leaving true emotion and song-craft parched, attritioned and abandoned with each subsequent release. Now, with the album 4 I believe I was proven correct, as the album has aged badly, and other than “Love On Top,” left no indelible mark on the pop landscape. But that conclusion on her future? Man listen, I was way off base.

Turns out this black woman from Houston, Texas got on her grind. She still is observant of all prominent trends in black culture and production, but over the last two albums and their accompanying visual films, Beyonce begun to establish the major themes of who she is and, thanks to directors like Jonas Ackerlund and Khalil Joseph and writer Warsen Shire, has concretely fused herself and her struggles into the larger narrative of black women in America.

And so Lemonade, her second best album, along with the emotional Lemonade(Film), present her as an American wife, defiant against the current rigors of her country, and a past that mutilates and morphs the men in her life. This well-crafted view of her though, is a fabrication, one that many stars have tried to present to the public. It feels digestible and true coming from Beyonce though, given that this album roll out was predicated on a very public (and very real) fight involving her sister Solange and her husband Jay Z.

What this gave the project was a narrative flow and imbued a sense of rage, disappointment or sorrow to the songs set. Those feelings were sometimes derived not from the song itself, but from the news details and gossip that filled in between the lines, or hovered over the whole album. But when the lights turn off and the band packs up, how well did the songs themselves transmit this idea of Beyonce?

The guitar lays a base for the song in curt chucks, not scratchy and acerbic, but warm and echoed, like the lazy, beautiful guitar throughout Bob Marley and the Wailers “Stir it Up.” The bassline curls and growls around the verdant pylons of drum kicks like an affectionate panther, while Beyonce holds a call and response with a choral of Beys, skanking and in love in the middle of this kinky reggae of “All Night.” “I’ve seen your scars and kissed your crime,” she says in a bold voice and melody, then later on she decides “give you some time to prove that I can trust you again,” before she relaxes into the joyous chorus. Her voice here on the hook is clear and strong yet delicate and floating, like Misty Copeland’s legs, or Beres Hammond’s voice on 90s reggae classic “Come Back Home.”

The album gets more interesting and tender like this as it goes along, like with the anthemic thump of “Freedom (featuring Kendrick Lamar),” a song with positive messages of black consciousness and self-determination that gets its blood pumping from the engaging drums, bass, Kendrick’s dexterous flows and the grooving organ.

Similar sturm und drang is found on first half highlight “Hurt Yourself (featuring Jack White)” where the drums and organ synth are agitated and staccato, while the guitars rage on unrestrained like white water rapids. “Who the fuck do you think I is? I smell that fragrance on your Louis V boy,” she demands, the static filter on her voice heightening the tension in her marital threats, and accosting the song.

Elsewhere, “Forward” with James Blake is a moody interlude, the voices and atmospherics setting the tone for the fog of emotional stasis that follows a crisis in relationships and the tentative steps out of it. It is mysterious and melodic, reminiscent of some of those dense songs on the first half of her best album, 2013s Beyonce.

These songs give true dimension to the album, and provide a strong enough thematic base for Lemonade to resolve itself with the Black pomp and majestic boom of lead single “Formation.” That balance between strong lyrics and engaging music in service of those themes is not an easy one to get right on such a varied album, and the whole storyline of the tarnished marriage papers over its mis-steps at some points.

Take “Sandcastles” for instance, a somber ballad with great piano and vocal harmonies throughout, while Beyonce reveals the fragility of love. Ballads like these usually accomplish this theme with a delicate poetry, but here the lyrics are wanting, hiding behind the singer’s dramatic rendering, at points wrenching the words out her throat. And on “Sorry,” the buzzed-about insults and vulgarity obfuscate the hollow production, which even now already sounds dated.

“6 inch” finds Beyonce in her f- me pumps, the woman undone, with The Weeknd narrating this lost weekend of bacchanalia with usual surface-level observations. A booming, strutting song built around an Isaac Hayes sample, the synth work around it though is a bit too overproduced and showy, and the words and the weak chorus don’t truly match the unwieldy production. At points in the song, while her harmonies descend with the grand, arranged music like Cinderella at the ball, none of this matters, but, in the clear light of the day after, the drawbacks remain.

Another factor that softens any drawbacks to the songs are their inclusion in her Lemonade(Film), released the same day as the album. The images, directed by Khalil Joseph and Beyonce are arresting at points, dreamlike at others, emphasizing the connection between the Carter’s marriage and those of the Black community at large.

Here, the image of Beyonce drowning in a room feels like an image any anguished woman might describe to you, and the images of older women in their chairs, the dancers popping and locking to “Formation” all seem like permutations of the same woman finding her way through a yet-to-be-broken cycle.

Many images, film shots and techniques here accompany the songs well, but some feel too weighty and derivative, reminding me too much of the works of Terrance Malick, the illusive director of classics like 1979s Days of Heaven starring Richard Gere, 1998s The Thin Red Line, starring Sean Penn, and 2005s The New World, an exploration of the Pocohontas story. Beyonce’s off-camera narration is very similar to the narration of The New World, down to her prayers to the moon and her dearest mother, shit even the font used for the chapter headings look the same. By the end, the film feels self-important, a spectacle of anguish, as opposed to an exploration of the self or the characters involved.

And it is that self-exploration that usually led to the more nuanced lines and confessions in divorce albums of the past, while on a lot of Lemonade it’s either all invective or adoration.

On Marvin Gaye’s 1979 album Here My Dear, he tells his ex-wife on “Anna’s Song” “Annas here's your song, the one that i promised you all along/ I knew all the time that I’d find the rhyme/ Never have a fear, here it is my dear,” his voice a soft reveal, showing the tragedy of finally figuring out what to tell a woman when she’s on her way out the door. And Lindsay Buckingham tells us on Fleetwood Mac’s “Never Going Back Again,” from Rumours, “she broke down and let me in/ made me see where I’ve been.” Shading in a portrait of a relationship with parts of oneself can lead to illuminating results, and this is seen in one of Beyonce’s best songs, “Love Drought.”

A slinky midnight love song that set up the conflicts and desires of this super-star marriage without being subsumed by the tabloid hurricane around them. “Ten times out of nine I know you’re lying, and nine times out of ten I know you’re trying,” she observes, resonant 808 booms and curling synth notes in the background. The personal life of the singer provides some context, but the songwriting and melodies are strong enough to exist without it, telling a universal story of modern love.

“I always paid attention, been devoted, tell me, what did I do wrong?” she confidently pleads, the film curiously overlaying her words with scenes from a baptism, Beyonce among the apostles of women wading into a body of water, raising their hands, yearning to be cleansed anew by the same tormenting earth.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Carter Trilogy, part one of five

Introduction: Let's make love in the summertime, and breathe in each other's arms

There's an interesting cultural and historical framing device us Americans have been using in order to make sense of, and to comb out the nappy-headed developments of the past couple of years. In our interactions with each other, we've resorted to reducing our shared events, and this ol’ President, and this ol’ year in particular, to a television show. The U.S. President assassinated a top Iranian General at the beginning of the year, and the news was communicated in countless late night jokes and online memes as the raucous events of the season premiere of 'America - The Series.'

In conversations throughout the year we would reduce the countless and needless complexities of this year into bite-sized episodes, and the countless and needless complexities of the Presidency into a mean ol’ villain or defiant hero in that show. We do this so we could for a moment, warren order from the disorder of a pandemic, and we do it in order to masticate Trump, in an attempt to find something of cultural value in the marrow there.