#so i was also mad about that in addition to the central plot conflict

Text

had a four hour dream where my ex and i were stuck in the same house and arguing there was tension and intrigue and bright colors and family and chickens and people playing irl minecraft and cats. it was wonderful

#in the last part i remember they were stomping around the garden#but the far edge because everyone was out on the lawn working on some new garden plots and a chicken coop#so they looked really silly trying to be mad but near a bunch of kids having a good time#and i had just finished locking myself in our room to cry and wallow so i had just come outside to get lunch#someone had ordered mexican food#and my dear ex had come in while i obviously did not want any visitors and told me to venmo the person who got food for everyone#and reminded me to include tax#so i was also mad about that in addition to the central plot conflict#and in the ending scene i got to help decide what sort of chickens we wanted but they were still sulking#so i chose two regular chickens two fancy chickens and two silkie chickens#but the fancy chickens were like bright as fuck neon colors!#and this guy walking down the street had a neon salamander pet that was the size of s medium dog and he told us where to find them#and then i woke up before any chickens#lunch#or reconciliation could happen#yes i am hungover thank you for asking

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Circe by Madeline Miller: a review

As you might have noticed, a few of my most recent posts were more or less a liveblog of Madeline Miller’s novel Circe. However, as they hardly exhausted the subject, a proper review is also in order. You can find it under the “read more” button. All sorts of content warnings apply because this book takes a number of turns one in theory can expect from Greek mythology but which I’d hardly expect to come up in relation to Circe.

I should note that this is my first contact with this author’s work. I am not familiar with Miller’s more famous, earlier novel Song of Achilles - I am not much of an Iliad aficionado, truth to be told. I read the poem itself when my literature class required it, but it left no strong impact on me, unlike, say, the Epic of Gilgamesh or, to stay within the theme of Greek mythology, Homeric Hymn to Demeter, works which I read at a similar point in my life on my own accord.

What motivated me to pick up this novel was the slim possibility that for once I’ll see my two favorite Greek gods in fiction, these being Hecate and Helios (in case you’re curious: #3 is Cybele but I suspect that unless some brave soul will attempt to adapt Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, she’ll forever be stuck with no popcultural presence outside Shin Megami Tensei). After all, it seemed reasonable to expect that Circe’s father will be involved considering their relationship, while rarely discussed in classical sources, seems remarkably close.

Hesiod’s Catalogue of Women and Apollonius’ Argonautica describe Circe arriving on her island in her father’s solar chariot, while Ptolemy Hephaestion (as quoted by Photius) notes that Helios protected her home during the Gigantomachy. Helios, for all intents and purposes, seems like a decent dad (and, in Medea’s case, grandpa) in the source material even though his most notable children (and granddaughter) are pretty much all cackling sorcerers, not celebrated heroes. How does Miller’s Helios fare, compared to his mythical self? Not great, to put it lightly, as you’ll see later. As for Hecate… she’s not even in the book.

Let me preface the core of the review by saying I don’t think reinterpreting myths, changing relations between figures, etc. is necessarily bad - ancient authors did it all the time, and modern adaptations will inevitably do so too, both to maintain internal coherence and perhaps to adjust the stories to a modern audience, much like ancient authors already did. I simply don’t think this book is successful at that. The purpose of the novel is ostensibly to elevate Circe above the status of a one-dimensional minor antagonist - but to accomplish this, the author mostly demonizes her family and a variety of other figures, so the net result is that there are more one dimensional female villains, not less. I expected the opposite, frankly.

The initial section of the novel focuses on Circe’s relationship with her family, chiefly with her father. That’s largely uncharted territory in the source material - to my knowledge no ancient author seemed particularly interested in covering this period in her life. Blank pages of this sort are definitely worth filling.

To begin with, Helios is characterized as abusive, neglectful and power-hungry. And also, for some reason, as Zeus’ main titan ally in the Titanomachy - a role which Hesiod attributes to Hecate… To be fair I do not think it’s Hesiod who serves as the primary inspiration here, as it’s hard to see any traces of his account - in which Zeus wins in no small part because he promises the lesser titans higher positions that they had under Cronus - in Miller’s version of events.

Only Helios and Oceanus keep their share, and are presented as Zeus’ only titan allies (there’s a small plot hole as Selene appears in the novel and evidently still is the moon…) - contrary to just about any portrayal of the conflict, in which many titans actually side with Zeus and his siblings. Also, worth noting that in Hesiod’s version it’s not Oceanus himself who cements the pact with Zeus, it’s his daughter Styx - yes, -that- Styx. Missed opportunity to put more focus on female mythical figures - first of many in this work, despite many reviews praising it as “feminist.”

Of course, it’s not all about Helios. We are quickly introduced to a variety of female characters as well (though, as I noted above, none of these traditionally connected to the Titanomachy despite it being a prominent aspect of the book’s background). They are all somewhat repetitive - to the point of being basically interchangeable. Circe’s mother is vain and cruel; so is Scylla. And Pasiphae. There’s no real indication of any hostility between Circe and any of her siblings in classical sources, as far as I am aware, but here it’s a central theme. The subplots pertaining to it bear an uncanny resemblance to these young adult novels in which the heroine, who is Not Like Other Girls, confronts the Chads and Stacies of the world, and I can’t shake off the feelings that it’s exactly what it is, though with superficial mythical flourish on top.

I should note that Pasiphae gets a focus arc of sorts - which to my surprise somehow manages to be more sexist than the primary sources. A pretty famous tidbit repeated by many ancient authors is that Pasiphae cursed her husband Minos, regarded as unfaithful, to kill anyone else he’d have sex with with his… well, bodily fluids. Here she does it entirely because she’s a debased sadist and not because unfaithfulness is something one can be justifiably mad about. You’d think it would be easy to put a sympathetic spin on this.

But the book manages to top that in the very same chapter - can’t have Pasiphae without the Minotaur (sadly - I think virtually everything else about Pasiphae and Minos is more fun than that myth but alas) so in a brand new twist on this myth we learn that actually the infamous affair wasn’t a curse placed on Pasiphae by Poseidon or Aphrodite because of some transgression committed by Minos. She’s just wretched like that by nature. I’m frankly speechless, especially taking into account the book often goes out of its way to present deities in the worst light possible otherwise, and which as I noted reviews praise for its feminist approach - I’m not exactly sure if treating Pasiphae worse than Greek and Roman authors did counts as that.

I should note this is not the only instance of… weirdly enthusiastic references to carnal relations between gods and cattle in this book, as there’s also a weird offhand mention of Helios being the father of his own cows. This, as far as I can tell, is not present in any classical sources and truth to be told I am not a huge fan of this invention. I won’t try to think about the reason behind this addition to maintain my sanity.

Pasiphae aside - the author expands on the vague backstory Circe has in classical texts which I’ve mentioned earlier. You’d expect that her island would be a gift from her father - after all many ancient sources state that he provided his children and grandchildren with extravagant gifts. However, since Helios bears little resemblance to his mythical self, Aeaea is instead a place of exile here, since Helios hates Circe and Zeus is afraid of witchcraft and demands such a solution (the same Zeus who, according to Hesiod, holds Hecate in high esteem and who appeared with her on coins reasonably commonly… but hey, licentia poetica, this idea isn’t necessarily bad in itself). Witchcraft is presented as an art exclusive to Helios’ children here - Hecate is nowhere to be found, it’s basically as if her every role in Greek mythology was surgically removed. A bit of a downer, especially since at least one text - I think Ovid’s Metarphoses? - Circe directly invokes Hecate during her confrontation with king Picus (Surprisingly absent here despite being a much more fitting antagonist for Circe than many of the characters presented as her adversaries in this novel…)

Of course, we also learn about the origin of Circe’s signature spell according to ancient sources, changing people into animals. It actually takes the novel a longer while to get there, and the invented backstory boils down to Circe getting raped. Despite ancient Greek authors being rather keen on rape as plot device, to my knowledge this was never a part of any myth about Circe. Rather odd decision to put it lightly but I suppose at least there was no cattle involved this time, perhaps two times was enough for the author. Still, I can’t help but feel like much like many other ideas present in this book it seems a bit like the author’s intent is less elevating the Circe above the role of a one note witch antagonist, but rather punishing her for being that. The fact she keeps self loathing about her origin and about not being human doesn’t exactly help to shake off this feeling.

This impression that the author isn’t really fond of Circe being a wacky witch only grows stronger when Odysseus enters the scene. There was already a bit of a problem before with Circe’s life revolving around love interests before - somewhat random ones at that (Dedalus during the Pasiphae arc and Hermes on and off - not sure what the inspiration for either of these was) - but it was less noticeable since it was ultimately in the background and the focus was the conflict between Circe and Helios, Pasiphae, etc. In the case of Odysseus it’s much more notable because these subplots cease to appear for a while. As a result of meeting him, Circe decides she wants to experience the joys of motherhood, which long story short eventually leads to the birth of Telegonus, who does exactly what he was famous for.

The final arcs have a variety of truly baffling plot twists which didn’t really appeal to me, but which I suppose at least show a degree of creativity - better than just turning Helios’ attitude towards his children upside down for sure. Circe ends up consulting an oc character who I can only describe as “stingray Cthulhu.” His presence doesn’t really add much, and frankly it feels like yet another wasted opportunity to use Hecate, but I digress. Oh, also in another twist Athena is recast as the villain of the Odyssey.

Eventually Circe gets to meet Odysseus’ family, for once interacts with another female character on positive terms (with Penelope, to be specific) and… gets together with Telemachus, which to be fair is something present in many ancient works but which feels weird here since there was a pretty long passage about Odysseus describing him as a child to Circe. I think I could live without it. Honestly having her get together with Penelope would feel considerably less weird, but there are no lesbians in the world of this novel. It would appear that the praise for Song of Achilles is connected to the portrayal of gay relationships in it. Can’t say that this applies to Circe - on this front we have an offhand mention of Hyacinth's death. which seems to serve no real purpose other than establishing otherwise irrelevant wind god is evil, and what feels like an advert for Song of Achilles courtesy of Odysseus, which takes less than one page.

Eventually Circe opts to become mortal to live with Telemachus and denounces her father and… that’s it. This concludes the story of Circe. I don’t exactly think the original is the deepest or greatest character in classical literature, but I must admit I’d rather read about her wacky witch adventures than about Miller’s Circe.

A few small notes I couldn’t fit elsewhere: something very minor that bothered me a lot but that to be honest I don’t think most readers will notice is the extremely chaotic approach to occasional references to the world outside Greece - Sumer is randomly mentioned… chronologically after Babylon and Assyria, and in relation to Persians (or rather - to Perses living among them). At the time we can speak of “Persians” Sumerian was a dead language at best understood by a few literati in the former great cities of Mesopotamia so this is about the same as if a novel about Mesopotamia mentioned Macedonians and then completely randomly Minoans at a chronologically later point.

Miller additionally either confused or conflated Perses, son of Perseus, who was viewed positively and associated with Persia (so positively that Xerxes purportedly tried to use it for propaganda purposes!) with Perses the obscure brother of Circe et. al, who is a villain in an equally obscure myth casting Medea as the heroine, in which he rules over “Tauric Chersonese,” the Greek name of a part of Crimea. I am honestly uncertain why was he even there as he amounts to nothing in the book, and there are more prominent minor children of Helios who get no mention (like Aix or Phaeton) so it’s hard to argue it was for the sake of completion. Medea evidently doesn’t triumph over him offscreen which is his sole mythical purpose.

Is there something I liked? Well, I’m pretty happy Selene only spoke twice, considering it’s in all due likeness all that spared her from the fate of receiving similarly “amazing” new characterization as her brother. As is, she was… okay.

Overall I am definitely not a fan of the book. As for its purported ideological value? It certainly has a female main character. Said character sure does have many experiences which are associated with women. However, I can’t help but think that the novel isn’t exactly feminist - it certainly focuses on Circe, but does it really try to “rehabilitate” her? And is it really “rehabilitation” and feminist reinterpretation when almost every single female character in the book is the same, and arguably depicted with even less compassion than in the source material? It instead felt like the author’s goal is take away any joy and grandeur present in myths, and to deprive Circe of most of what actually makes her Circe. We don’t need to make myths joyless to make them fit for a new era. It’s okay for female characters to be wacky one off villains and there’s no need to punish them for it. A book which celebrates Circe for who she actually is in the Odyssey and in other Greek sources - an unapologetic and honestly pretty funny character - would feel much more feminist to me that a book where she is a wacky witch not because she feels like it but because she got raped, if you ask me.

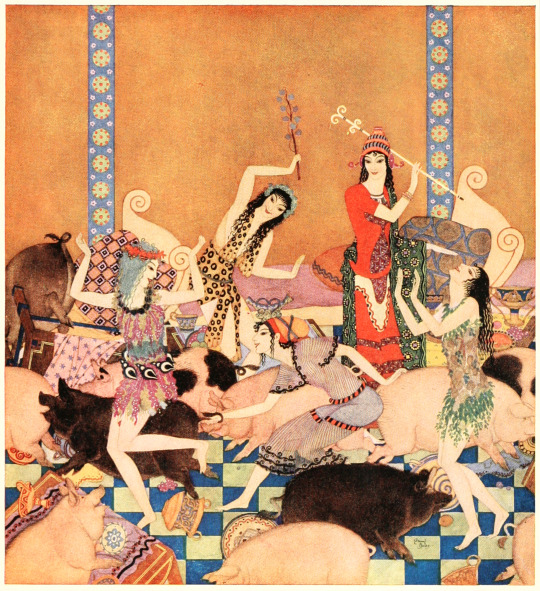

Circe evidently having the time of her life, by Edmund Dulac (public domain)

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The start of a gallery regarding Belphegor and the guys, but including a great deal of meta and extra gifs behind the cut, including relevance explicitly to Dean and Castiel, as well as Belphegor’s mythological relevance.

Edit: Since this post is making the rounds I’ma drop in my Belphegor meta-fanvid too. The meta/extra gifs are below the vid.

youtube

Yeah I know I’m a day late, no I don’t know if anyone has beaten me to this, I know some people beat me to talking about belphegor beyond me vagueblog screaming about him showing up on twitter with livetweets. For those who haven’t seen:

Belphegor - a Moabite god absorbed into Hebrew lore and then Christianity as a major DEMON. The name Belphegor means “lord of opening” or “lord Baal of Mt. Phegor.” As a Moabite deity, he was known as Baal-Peor and ruled over fertility and sexual power. He was worshipped in the form of a phallus. -- that giant rock he talked about worshipping, there you go.

In the KABBALAH, Belphegor was an angel in the order of principalities prior to his fall. He is one of the Togarini, “the wranglers.” He is an archdemon who is part of the demonic counterparts to the angels who rule the 10 sephirot of the Tree of Life; he rules over the sixth sephirah. He sits on a pierced chair, for excrement is his sacrificial offering. In Christian demonology, Belphegor is the incarnation of one of the SEVEN DEADLY SINS, sloth, characterized by negligence and apathy. According to St. Thomas Aquinas, all sins that arise from ignorance are caused by sloth.

Belphegor also rules misogyny and licentious men. He emerged from HELL to investigate the marital state among humans. For a time, he lived as a man to experience sexual pleasures. Appalled, he fled back to hell, happy that intercourse between men and women did not exist there.-- here’s the big block that I find fascinating.

Gully, Rosemary. 2009. The Encyclopedia of Demons and Demonology. New York: Visionary Living, Inc., pp. 27-28.

(For more discussion of Belphegor’s history and mythology on this blog, click this link (x) but I’m mostly narrowing it down to what’s relevant for address here.)

With that out of the way, I refer you to the gallery above, which is only a fraction of what I’ve clipped from the episode.

(Edit: As new things have come to light with a rewatch, or as new thoughts come up, I’ve been reblogging this post with additions; however, at the end of the post, I’m going to make headline titles for update thresholds and include it in here as a sort of Belphegor introduction masterpost. Any time I get to glance at part of this episode again it just gets LOUDER.)

The camera work is uncanny. Castiel and Dean are repeatedly cast not only as a unit, or Sam blotted off, or divided, but of a point of focus. A few more examples:

Oh wow Belphegor really just staring at them.

Think I’m just choosing frames I like? Check back at the scene. Whenever Sam engages it’s literally from a different, peripheral shot as so:

This filming style isn’t single shots, but the entire scene. Oh, I don’t mean the entire scene, I mean the entire episode. The only place this rule wavers is when literally everybody is packed in the Impala, including when they save the mother and child, and until people decompress it’s impossible to do such controlled shots.

But then there IS when they decompress as I put in the original gallery.

Belphegor sits witness to the pain and upset over Cas, unable to look at him. And, shortly after talking about the giant penis he used to worship and flirting with Dean, asks who the child was to them after Cas has stormed out, finding out about it being their son.

At this point both Castiel and Dean have had their standoffs with Belphegor, which I side by sided in the top gallery. But Dean’s integration with Belphegor goes an entirely extra level.

We’ll handwave any deep readings about the heart of a man being needed -- but the simple fact is, as we know, this is when Dean and Belphegor encounter the white woman.

That alone is a fascinating point;

Whether you take Sam’s encounter as his serial killer fetish, or his clown phobia, or some people’s read of toxic parenting, or a combination of these -- the first two more likely to tickle the general audience -- this is clear.

Whether you take Cas’ encounter with Bloody Mary as the secret about Jack and guilt over Mary, or the secret over the Empty and general guilt over failing Jack, his connection is loudly clear.

The woman in white was a spouse betrayed by her partner and driven to madness where she killed her children and then herself -- something fairly clear if we remember the metaphorical ledge Dean was on at the end of the season that he steered away from, but the argument continues.

Blahblah *heterosexual handwave* just subtext just interpretation only the other two matter for Reasons(TM), we know how that will go. This, or the random divorce drop from the victim girls for totally inoccuous and random reasons aside, is just a worthwhile note to put in here as we consider the framing of Belphegor.

Throughout the episode, Sam has no identifiable major exchange with Belphegor. He happens to be in the vicinity, occasionally mediating Dean and Cas, or in the same car, but there is no forward led conversation, there is no personal tension or banter, and most of all there isn’t even any attempt at directorial focus. If anything, directorial blotting. Sam’s plot shines more in being a forward moving, smart hunter mediating the two here, but if we’re here to look at Belphegor--

As Castiel sadly watches the rescued mother and child go to the school, in the wake of the death of his son, Dean only tersely checks on him. It’s strained, and Castiel is left staggered, only for us yet again to find Belphegor framed into the conversation, observing, as he has through the previous shots.

Belphegor’s placement is right between Dean and Cas, leaving it almost inevitable that as we move forward, he will annex emotional territory if by trust or nuisance to dig a deeper wound and antagonize the marriage he observes dissolving in front of him, a very personal and living manifestation of their struggles for these two to overcome, and inevitably part of what will send Castiel away briefly in 15.3 as he feels himself growing more and more detached from the Winchesters -- particularly Dean, as Sam is actively still engaging with him as is typical of them but like Entertainment Weekly recently put it, Castiel does has his favorite Winchester, and they’re totally-not-going-through-divorce-waves here, just totally heterosexual brovorce, of course.

Given considering my position of the overt and present canonicity of their relationship please note I’m only writing sarcastically towards the inevitable stupidity that haunts this fandom via anti dialogue and those that internalize it, but here it is, folks.

If anyone wants to even try to challenge me, I invite them to find Sam drawing belphegor’s focus on any front or being framed in the shots as Castiel and Dean are here. Belphegor is ... going to be a ride, folks. Buckle up. He’s literally been observing the hunter husbands, wracked with pain over the loss of their child, in active conflict despite their lingering stance as a unit, having held his ground with both of them to feel out their pain and rage each to themselves, and left to sit, and watch, and find what dark humor he may watch from them.

“Wanna talk about it?”

(Suggested reading: check out @tinkdw‘s post about them dividing Cas from his humanity *ba dum chink* and focusing on his angelicness this episode)

----

UPDATE 1

A belated addendum a few hours late I forgot to include but intended to: It has not escaped me that Dean and Cas also were both part of Belphegor’s spell casting. The aforementioned heart of a man with the trivial second ingredient of salt (truly not trivial at all in the alchemical scale of it, but that’s a topic for another time--just in SPNverse it seems weirdly easy; breaking down the alchemy in the last few seasons and the use of the salt in spell is its own essay), and the other common graveyard dirt and very conveniently angel blood. These things both created intensely powerful deus ex machinas that fall back to other points I made in the OP that are incredibly suspicious about the arrangement, and I’m more curious on if we should expect multiple parts of a spell eg reverse trials if you will or what.

I don’t consider these things a lack in SPN spellcasting integrity in writing. I consider these warnings.

UPDATE 2

Along with updates in the original post, someone posted this clip on twitter giggling about Dean’s expression, and something else I somehow missed the first time caught my eye.

youtube

Every time Belphegor opts to observe people or turn, while he comments on beauty and appearance (or stone penises or Dean being gorgeous), beyond his individual compliment of Dean – he is turning his head at couples. Or, well, we assume couples. At Units Of Two People. The two people units are:

A woman and a woman

A man and a woman

A man and a man.

Outside of the vehicle Belphegor is not taking any particular time paying attention to individuals. Only duos. The two women pass in front of the hearts, and one (the woman in khaki) even gestures at it to sort of make the woman in green look.

The man and the women walk by, vaguely locking arms.

Belphegor looks straight between these units. He leans forward, discussing people on earth being attractive. He turns and looks out the window to observe the two men now walking past the window with hearts.

Drops the comment about worshipping a giant penis, and so forth.

But the direct observation of duos, potentially queer ones literally framed in hearts in case anybody misses it for not being hetnorm, is… well, in lieu of the OP, this is. Yeah. It’s a whole thing. Holy crap.

UPDATE 3

This one isn’t necessarily big enough for a central update, and isn’t even entirely Belphegor focused as Belphegor adjacent. A friend ( @tarend ) had asked passively why bikes were so prominently featured in this episode, so here’s what I’ve found.

The green and blue bikes feature predominantly in the clown victim house from the first scene we see the garage, fairly early in the episode and every other showing until they’re extracted from the house. Often central, doorway, access, or backshadow in most shots. Trying to pin it on a single character would be ignoring the broadness of it, but the presence was enough to take note of.

Various two people units roll around with bikes of different and more muted colors.

The two dudes, one of them has a green bike and one has a grocery sack which I imagine ISN’T fruit from the tree of life.

I do find it weird and, especially since the green and blue bike collectively manage to get several shared minutes of screen time in a busy episode, I have to wonder, but I can’t find anything meaningful here without jumping to the common “green and blue” thing and a random joke-reach towards Queen which isn’t really my flavor of meta despite it even kind of matching the people passing by. The overlap is there and tangible, regardless, and passes in the background of Belphegor, so I’ll leave that here as a general sentiment.

Compared to the above gold mine of far more overt material, if this ever was intended to be an intentional nod of some sort, I feel like it’s been overshadowed entirely by the other content which might as well have been blasted from a bull horn, but maybe someone else can find use in it in association. Aside from the street highlights in the car while Dean sits by with Belphegor, the prominent double bike placement is best witnessed rather than screenshot into eternity in any scene involving Clown House Garage.

Though I may point out the dynamic impala shot with the paired bikes in the background is immediately followed by a stroller that colllectively haunt the three people in the car, but whether I’d swear to that being intentionally syncretic, I’m unsure. But I do feel it’s worth notating.

I’m sure you all know I’m guarded about things like this fandom’s build on key colors and don’t apply it in meta outside of standard lighting theory, and generally even props are things I ignore unless they’re actual framing and blocking focuses, but the bikes do ride a line. They just lack the overall thematic story use most things I talk about do, like mystic symbols and the ilk. I would probably completely disregard this were it not for the other elements above, but now I’ll be keeping an eye on it.

UPDATE 4

Yet another thought more from @tarend than me, but his ass just about never posts so I might as well plug it into the viral post with some credit.

There seems to be painstaking effort to frame Belphegor with stop signs.

Cough

Crack aside it’s just some angle play that could be coincidence but I’m going to be throwing that out there for meta fodder for others while this spreads around until I can truly rewatch since life is seriously climbing me right now.

Tarend also points out the school was named after The Great Dissenter (Link).

I’m going to have a bit of a comparative study on Belphegor’s and Chuck’s mannerisms for consideration but life didn’t even give me 30 minutes for a video edit today much less a rewatch.

#supernatural#spn#15.01#final season#belphegor#directing#divorce#15x01#15.1#15x1#back and to the future#destiel#deancas#meta#my meta#mine#tree of life#thagirion#tiphareth#art

718 notes

·

View notes

Note

So, uh, a while back you mentioned making a post about how Prisoner McNord might affect the player experience/perceptions of the "default" and I would be super interested in reading that

So!

I have a few thoughts already on what is considered “default” in Skyrim to be expanded upon in a future shitstorm rant (it’s on the list, between Almalexia Is Interesting Actually and Even More Crying About Snow Elves Part 17: My Tears Have Become Sentient And Are Also Crying).

And as always, keep in mind that Skyrim is coming up on 9 years old, elements of it have not aged well, and this is in no way, shape, or form meant to be a “If you like Skyrim then you’re Bad” rant. In case you haven’t noticed, I kind of love that game. It has flaws; all games do, and frankly it’s a miracle this game is as solid as it is. The writers are that, writers. They had deadlines to make, hardware limitations to consider, and above all else, worked for a company that wanted to make money.

To keep this relatively short I’ll focus on how your perception of Skyrim is influenced by the first few minutes of the game via Ralof, the Nordiest Nord to Nord since Ysgranord, and how the writers really, really really wanted you to hold on to that perception.

Overanalysis and spoilers (Metal Gear Solid, Borderlands, and Bioshock respectively yes this will all make sense in context) under the cut.

Part 1: How To Make A Perspective In Three Easy Steps

As the saying goes, first impressions are lasting impressions. This is evident in.. well, every bit of media you can find. The first chapters of a book, the first episode of a show, the first 15 minutes of a video game, all as a general rule:

1.) Introduces the setting, a part of the main plot, and with these two, sets the tone of the medium (high fantasy movie, light hearted TV show, mystery series, horror game, etc.). Exceptions exist, especially in horrors, mysteries, and certain visual novels, but even these exceptions rely on setting a tone so they can subvert your expectations later on.

2.) Give you an idea of what is going on. This is normally accomplished with exposition of some sort; Star Wars had its famous screen crawl expositing the dark times in the Galaxy, Borderlands literally begins with “So, you want to hear a story..”, Metal Gear Solid briefs Solid Snake (you, the player character) on a vital mission to save two hostages and end a terrorist threat, so on and so forth. And again, there are exceptions: Bioshock purposefully disorients you with a plane crash in the middle of the ocean so you’re inclined to trust the first person who talks to you.

This all serves to suspend disbelief, immerse you, and earn your trust. This is a new world, you have no idea what’s going on, so you’re gonna take cues from someone who does. Combine points 1 and 2, and that..

3.) Gives you an idea of what is “good” and what is “bad”. Damn near every story has a central conflict, you gotta pick a side, and there’s gonna be a bias as to which one is superior or morally just. Using Bioshock again, this mysterious man named Atlas guides you through the first level, and tells you how to fight and survive in the hostile environment of Rapture; meanwhile, Andrew Ryan taunts and belittles you, and also has a giant golden bust of himself. The shorthand is: Atlas is humble, helpful, and good, while Andrew Ryan is a megalomaniac who wants you dead. Leaning on Borderlands again, the first voice you hear is literally a guardian angel telling you not to be afraid, and that you are destined to do great things. Once more with Metal Gear: Your organization and your commanders are good, you are good because you’re saving innocent people, and FOXHOUND is bad because they’re terrorists who have the means to launch a nuclear warhead.

Keeping all this in mind, let’s do a quick runthrough of the first, let’s call it 15 minutes of Skyrim. No commentary on my end, just a play by play of the beginning of the game.

Part 2: First Impressions In Action

You wake up on a cart. Your vision is hazy, and you are clearly disoriented. You see a man bound and gagged, another man in rags, and several men dressed like soldiers. Everyone on the cart is tied up, and the people driving the cart are wearing a neat, vastly different uniform.

Then comes the famous line: “You! You’re finally awake! You were caught trying to cross the border, got caught in that Imperial ambush same as us, and that thief over there!” The thief bitterly remarks how these damn Stormcloaks had to cook up trouble in a nice and lazy Empire. The Nord who first spoke with you nobly says that we’re all brothers and sisters in these binds.

The presumed Imperial tells you all to shut up. Undeterred, the thief and the Stormcloak provide more exposition: The gagged man is the leader of the resistance, is supposedly the true High King, and since he’s on the cart, it’s clear that everyone on board is bound for the executioner’s block. The thief is terrified; the Nord accepts his fate, but takes a moment to opine on better days when he flirted with girls and “when the Imperial walls made him feel safe.” There is also a remark about General Tulius and the Thalmor agents; the Nord, in a rare bit of anger, damns the Elves and insinuates they had a hand in this capture.

It’s execution time. General Tulius gives a speech about how Ulfric started a civil war and killed the former High King; Ulfric, being gagged, cannot say a word in defense. A Stormcloak is executed to mixed reactions (“You Imperial bastards!” “Justice!”, etc.). The thief runs away; he is shot by Imperial archers, demonstrating the futility of escape. It’s your turn. The Nord in Imperial armor states you’re not on the list; the Imperial captain doesn’t care and orders you to the block anyway.

You see the headsman’s axe rise up when, as if the gods intervene, a dragon appears and interrupts your execution. In the chaos, you run with the Stormcloaks. The game does not give you the option to run away alone, or with the Imperials; until you meet Hadvar again in the fire and death, you take orders from Ulfric.

Part 3: The Crux

A lot happens in the first few minutes of Skyrim. You’re disoriented from being unconscious, and that’s compounded by your two near death experiences (point 2), the first person you meet is a calm, almost reassuring mouthpiece of exposition while the other side, at best, doesn’t care if you die (points 2 and 3), one major aspect of the plot is revealed (point 1, and the tone is that this is a classic Rebellion story).

And people love rebellion stories. Americans especially; we spend billions on the day when a bunch of white guys said “fuck you” to a bunch of other white guys. With the additional layer of when Skyrim was developed, by who, and in what landscape it was written.. Yeah. There may be two ways to go for the Civil War questline, but for most players (myself included!) their first gut instinct is going to be “side with the guys who didn’t just try to kill me.”

It’s the same song and dance. In Bioshock, your instinct is to trust the Irish guy who wants to help you get out of Rapture alive, but he needs your help first. In Borderlands, your instinct is to trust the woman who is literally called a guardian angel, and she shows her compassion by asking you to help the people of Fyrestone and the poor robot who got hurt in a gunfight. In Metal Gear, your instinct is to shut down the threat because terrorists are evil and these ones are not just terrorists, they’re deserters. Hell, even in other Elder Scrolls games the plot is laid out by helping hands: you’re a prisoner being contacted by your murdered friend, and given the goal to stop Jagar Tharn (Arena), you’re a Blades agent tasked with putting a vengeful spirit to rest that leads you to a weapon that can secure the Empire’s power (Daggerfall), Azura literally tells you not to be afraid, and that you destined to stop an old threat (Morrowind), and a soon-to-be-assassinated Emperor voiced by Actual Grandpa Patrick Stewart recognizes you in a prophetic dream (Oblivion).

Where Skyrim departs from these games, and even the other Elder Scrolls titles, is how much it enforces the first thing you see as solidly good and evil, and how little it tries to subvert that perception. Remember point 2, when the game makes it clear that this person is trustworthy? Therein lies the bread and butter of psychological horror, mysteries, and heart wrenching plot twists: that trust gets tested, and often broken.

The rebel leader Atlas? He’s somehow more evil than Andrew Ryan, and has subtly controlled you the entire time with a command phrase (“Would you kindly..?”). You are unable to stop yourself when you bludgeon Andrew Ryan to death at Ryan’s command. “A man chooses,” he tells you. “A slave obeys.” His final words are him telling you that you are a puppet, only able to obey.

The end of Borderlands reveals that “Angel” was watching you the entire time.. from a Hyperion satellite. You were tricked into opening a Vault holding back a dangerous monster, and you don’t even know why. Borderlands 2 goes further into just what (or rather who) Angel is: a teenage girl and a powerful Siren, used by her own demented, evil, father, Handsome Jack, to manipulate the Vault Hunters and gain more power for himself. Her final mission given to you is simple: she wants you to set her free and end her father’s mad march to power by killing her.

Metal Gear Solid ultimately plays it straight in that you stop the terrorists and disable the nuclear threat, but you don’t emerge from the rubble as an action hero; you’re forced to kill your own brother, the terrorist cell is revealed to be composed almost entirely of people exploited by your organization, and you secretly carry a virus designed to kill the people you were trying to save. War, as it turns out, is not as clear-cut as “we good, they bad”. The people you’ve killed without thinking are your genetic brothers. Sniper Wolf, the assassin who shot your commander’s niece, survived a genocide and has never known a life outside of war. Psycho Mantis’ telepathic gifts were exploited by both the KGB and FBI until he lost his mind. Ocelot is Ocelot.

Oh, but those are other games. What about The Elder Scrolls? Well..

In Daggerfall, your search for hidden correspondence leads you to finding the Mantella, a sort of soul gem that can power the superweapon everyone wants: The Numidium. There are six entities total who want the Mantella, some for their personal gain, one to make a home for his people, and one so he may finally die; the Underking’s soul is in that gem, you see, and he’s been trapped in this misery since the days of Tiber Septim.

In Morrowind, Dagoth Ur recognizes you not as a schlub with a dummy thick journal, but as his oldest and dearest friend. The Empire who guided you for so long? They’ve manipulated you into taking down the Tribunal, destroying the one weapon that could stand against their might, and depending on your interpretation of “then the Nerevarine sailed to Akavir”, have possibly killed you.

And what of everyone’s favorite game in the series to mock? Surprise! Oblivion isn’t even about you, hero! It’s about the actual chosen one, Martin Septim! Sure you can join the Thieves’ Guild and cavort about as Grey Fox, or uncover the traitor of the Dark Brotherhood, or run off and become the Mad God.. but none of those events actually acknowledge you. To be the Grey Fox is to literally be forgotten, by the time the Dark Brotherhood questline is complete there is effectively no more Dark Brotherhood, and to become Sheogorath is to lose yourself entirely. The Hero of Kvatch is one who is ultimately forgotten. Your actions were important, have no doubt, but such is the fate of the unsung hero: they’re not sung about.

Even Arena plays a little bit with your expectations in that the Staff of Chaos alone isn’t enough to stop Jagar Tharn; you need friendship (just kidding it’s a magic gem in the Imperial Palace). Skyrim.. kinda glosses over that. They land a few punches, but for them to stay with you, you have to keep an open mind.

Part 4: Why does that matter?

Because if your expectations are never subverted, your trust never tried in any meaningful way, then your perception of a very specific, spoon-fed worldview is never challenged. The trust you build with a group that is, in essence, a fascist paramilitary cult is never shaken in any way that’s meaningful. You get some lines intended to evoke sadness when you sack Whiterun, but by then it’s too late. Not that it matters; at the end of the Stormcloak questline, there’s not much question about who was in the right. You never lose friends or allies; the Jarls in the holds change, but is there much difference between Idgrod Ravencrone and Sorli the Builder? You might feel a little guilty when you see the Dunmer forced to live in the slums, but then the haughty High Elf says that she didn’t laze around and instead made a name for herself, or the Dark Elf farmer who complains about his snowflake kinsmen harping on about “injustices”. The Argonians seem decent until you meet the skooma addict/thief, and the Khajiit.. let’s just say that even if we disregard the two Khajiit assassins sent to kill you, there exist a lot of extremely harmful stereotypes that none of your friends dispel. They commit no horrific war crimes in your presence, the worst you hear is a Nord (normally a bandit) yell “Skyrim is for the Nords!”, or the clumsy Welcome to Winterhold script where a Dunmer woman is harassed by two Nords; one’s a veteran, by the way. Got run through the chest by an Imperial craven, or so the story goes.

Your only chance to rattle the Nord-driven story is to go against your gut feeling and side with the Imperials (the plotline is pretty weak, not gonna lie), or complete the optional quest No One Escapes Cindha Mine where you see what a Stormcloak sympathizer does to the Forsworn. Even if you complete that quest, the Forsworn still attack you. “They’re savages,” say the Nords, and the game isn’t too inclined to say otherwise.

When it comes to portraying the Nords in any light that’s not negative, Skyrim doesn’t deliver like it did in other games. You saw what life is like in Morrowind under Tribunal rule; it’s not great. The Houses are almost universally awful and they have slaves. You see the destruction in Cyrodiil and hear the rumors on how much the Empire is flailing with the Oblivion Crisis. Hell, even Arena tells you that life in Tamriel kind of sucks, but it’ll suck a little less when Tharn is dead.

That doesn’t happen in Skyrim. You are encouraged to join the sympathetic Stormcloaks, you find out your destiny as Dragonborn, and you set all these things right. Of course you do. You’re a hero, baby. Others have gone on about how storybook the Dragonborn questline is so I won’t go too much in, but that’s it exactly: Storybook. You’re Neutral Good. You’re going to kill the bad dragon that wants to do its job and eat the world.

And that refusal to really examine the nuances and horrors of war, to consider what it means to be a hero that is never morally challenged or forced into a Total Perspective Vortex, to never challenge an extremely biased perspective or even explore its “logical” conclusion?

It leads to extremely dangerous ways of thinking if unchecked.

#lore overanalysis#about my favorite subjects: media studies and skyrim#this is another long one#good god it's long

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

December 29: The Wrath of Khan

Today’s movie watching was Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.

My overall impression versus TMP is that this is clearly a smoother and more consistently entertaining film. It has a definite story with very little filler, good pacing, a lot of great little dialogue and character moments, and a strong conflict at its center.

But its sci fi bona fides are much weaker. Like by a lot.

Mom and I are talking a bit about Genesis and the more we talk, the weaker it appears to me. First, it’s not really as believable, imo, as a lot of Star Trek. Maybe it’s because it’s not alien based, but I just have a harder time suspending disbelief to think this is possible. Second, it’s not clear why anyone thought this was a good idea. I mean, as McCoy immediately pointed out, it just seems so CLEARLY dangerous: an object meant to foster creation that could so easily be the worst weapon the universe has ever known--nothing could go awry there! Third, the reason for creating such a device isn’t obvious at all. Carol mentions the “growing population” and “food scarcity” but nothing we’ve ever seen of the Federation implies they’re running out of space. Or, frankly (Tarsus IV aside), food. And fourth, there really isn’t any point to Genesis in all its particulars in this film. Like, obviously, its actual purpose is a plot device to resurrect Spock. Within just this film, it doesn’t do anything. Khan wants it, for some reason I’ve already forgotten even though I just saw the film, and he gets it, but I didn’t even notice that happening, because it was so unimportant. His REAL mission is his single minded revenge fantasy on Kirk. Genesis is just a McGuffin/space filler/plot device for the next film.

And honestly that’s not such a big deal, except that when you compare it to TMP, ,and its central idea of a human made probe that gained so much knowledge, doing what we taught it to do, that it became sentient and then started searching for the meaning of life, and how this relates to the search for meaning experienced by the main alien lead, and how his search, in that film and throughout the series, is a mirror for humans and OUR need for purpose... well it just seems really weak. “We made this really dangerous and unrealistic thing for no reason whoops!”

Mom is now criticizing Kirk for being too slow on the uptake when he first encounters the Reliant, which is fair. That’s pretty OOC of him. The idea that he’s too old for space is both one that I must personally disregard, and one that the film would have you discard, since we’ve already heard from TWO characters, the people who know him best, that his best destiny is as a starship captain, and command is his proper role. And that he might be a little rusty is also not a great explanation imo, because the rust was supposed to have come off in TMP. So, plot hole probably.

We were trying to do some math--TMP is at least 2 years post 5YM and TWOK is at least 10 years post TMP, so at least 8 years post TMP. I can understand more rust growing but like... he was already an Admiral in TMP and the idea that he was out of practice with actual command was a big part of his arc there. So it doesn’t seem warranted to do that again.

Also, the way he was commanding poorly in TMP was very IC: he was pushing too hard, trying too much, caring too much about the mission and not enough about...the laws of physics. That’s very Kirk. Being slow on the uptake, caught with his britches down--that’s not Kirk. Plus, with no one to call him out on it, like Decker did in TMP, his poor command doesn’t seem like a big character obstacle to overcome but just like...sloppiness all around.

I thought Khan was over all... just not that interesting. I guess I’m just not into the obsession/revenge plot. Also...idk man he didn’t seem that super to me. He outsmarted Kirk, like, once, and Kirk outsmarted him like 4 times. He tortured some people--but regular humans can do that. He used those sandworm thingies, which is also something humans could do. Overall, he didn’t seem to have any particularly special skills. The only time he really seemed like a worthy adversary for Kirk was when Kirk wasn’t really being IC himself.

I’m also not into the fridging of his wife. Think how much cooler it would have been if she’d still been alive! The only non-super human in the bunch and she’s still there! Ex-Starfleet and bitter!

The K/S in this film is very soothing. Imo they are clearly together here, and the whole film is better if you assume they’re boyfriends and everyone knows. That Vulcan convo that Spock and Saavik have? Waaaaay funnier if you think she’s talking about his boyfriend (”not what I expected....very human” “Well no one’s perfect”). Every time they call each other ‘friend’ like ““friend”“? All the Looks? The birthday gift?

Also the “I have been and always shall be your [friend]” scene is a wedding I will not be taking criticism on this opinion. Could it have been written more like a vow? I think not. It’s not quite This Simple Feeling but it’s the best this film has in that regard.

I liked Saavik and I do think she’s one of the better later-movie additions (though I only like her, as far as I can remember, when played by Kirstie Alley). She didn’t necessarily strike me as super alien, though, at least not at first... But I appreciated how persistent she was about the stupid test, and her regulation quoting. I enjoyed her. I also liked how she was obviously Spock’s protege, which makes her Kirk’s step-protege, and they had just a little bit of that awkward dynamic going on. (”Did you change your hair?”)

The Bones and Kirk relationship was great in this film. You can really feel their friendship and their history with each other. Bones knows him so well and can be honest with him, just when Kirk needs it most.

I also love how Kirk has the SAME conversation with both Bones and Spock (re: being a captain again) but with Spock it’s sooooo much flirtier. In case you weren’t sure what the difference in these two relationships is.

Bonus: this bit of dialogue: Spock: “Be careful, Jim.” / Bones: “WE will.” Lol Spock people who aren’t your boyfriend do exist.

Obviously, I cried during THAT scene. Honestly AOS should have taken note about how to do emotional scenes like that: they come after the main action is over and the villain is defeated. Then they hit at the right time and to the right degree. Kirk just slumping down after Spock dies....like he’s boneless...like he doesn’t know what to do... I CANNOT.

I feel so bad for him that I’ll even forgive him that awful eulogy. Spock died for Genesis? Uh, no, he died for the Enterprise, and for YOU. Spock is the “most human”? You shut your whoreson mouth

I remember hating both Carol and David but I actually hated them less this time, Carol especially. My mom is being really harsh about her, though, which makes me feel less confident in my assessment. I mean first off, she’s the inventor of Genesis, which is a pretty big strike against her. Second...pretty lame to keep Kirk from David. Although I did some vague math and Kirk would only have been about 21, still in the Academy, when David was born, so you can see how that would work out. Also, she distinctly says “Were we together?” which means they were not--this was a fuck buddy arrangement for sure. More complicated. But it still feels weird to retcon that, like, he’s known THIS WHOLE TIME that he’s a dad and we’re only learning about it now, as an audience.

Anyway I’m getting off track. Carol. What to make of her? Is she unstable? Is she still mad at Kirk? My mom points out that she just decided on her own that David would want to join Starfleet if he knew Kirk was his father--whereas what seems to have happened instead is he didn’t just become a civilian scientist like his mom but became her specific protege--working on a project where everyone was probably handpicked by her? I would assume? Also..he hates Starfleet. Not to put everything on the mom, but how did that happen?

Also...going down the rabbit hole of this and feeling awkward about it... but David KNEW Kirk. As “that guy you hung around with.” That means Kirk was in his life for quite a while, long enough for him to have memories, and long enough for those memories to still be with him even into his 20s. But he was never allowed to know who Kirk was. That means Carol’s rule must have been “You can see your son but you can’t tell him who you are” which in some way seems meaner to me than just “please don’t contact us again.” If he was already on his way into space, that could even make sense--”I know you’re not going to be able to be a family with us, so let’s not pretend, let’s make a clean break now.” But that wasn’t what happened!

Anyway whatever not to be HAICG!Kirk about this or anything lol

David is mostly annoying because he’s so anti-Kirk lol. I found him least annoying when he came around to Kirk at the end. Another big strike against him: he wore his sweater tied over his shoulders in such a Preppy manner. I honestly don’t see what about him is supposed to be reminiscent of Kirk.

David/Saavik was definitely happening lol. I wish I could have heard that conversation. It sounds like she told him a lot!!! Not sure why she attached herself to this particular annoying human so fast but I guess she did.

....I think that might be all. The uniforms and general styling were much better than TMP (though less funny/entertaining), and it was certainly an enjoyable overall yarn. A lot to pick apart and critique but in a fun way. Will probably watch The Search for Spock soon.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think Chuck made Sam and Eileen like each other? Are you sure? Because that is not exactly the truth. They had a legitimate attraction since s11, when they met. Chuck just manipulated the situation, using a spell and helping her to reach the bunker. He didn't need to do anything else. Chuck knew that the two of them together in the bunker would undoubtedly result in a romance. Because their attraction is real. Their feelings are real. Chuck didn't manipulated it.

*sighs heavily and then looks into the endless depths of your sunglasses and wonders why we’re still doing this three months on*

If you see it that way, more power to you, honestly. I wish I could.

but also, and perhaps most importantly:

The fact that I am incapable of seeing it that way has no bearing on whether or not *you* see it that way.

Seriously. You are free to carry on with that cheerful and unproblematic view of events. Please feel free to continue to enjoy the ship as you see fit. You do not need the permission of randos typing on the internet to enjoy the show in whatever way pleases you best.

Here’s where I’m personally hitting a wall with it that nothing in canon has enabled *me personally* to climb over. To me, this isn’t something I can personally engage in a debate over, because everyone attempting to debate me on this point insists that the only satisfactory resolution to a conversation here is my unconditional acceptance of Sam and Eileen’s relationship as incontestably pure and free from the stain of Chuck’s influence. And I’m gonna put this next bit in its own paragraph, because I really, really need people to understand this, because it’s not about *you* it’s about *me*:

Because of experiences in my own life, I am incapable of seeing it that way.

Please reread that last sentence, and really, really think about what I’m telling you here. And then reconsider this campaign to convince me that I’m somehow wrong here. If I’m wrong, if canon is headed toward a Sam and Eileen happy endgame scenario, that will play out on screen in a way that I won’t be able to deny, with both of them making choices out of their own free will, untainted by Chuck’s control going forward.

If you can truly see them as already romantic, then please consider yourself lucky. Understand that some of us do not have that luxury.

As to your other points, I have never said that Chuck “made Sam and Eileen like each other.” Of course Sam and Eileen liked each other before. That’s literally what I said in the post I made about this *yesterday*:

On the surface, it’s different because Sam and Eileen actually LIKED each other before, years in the past before her untimely death.

You can read that whole (long) post here, because pulling statements out of context doesn’t serve anyone:

https://mittensmorgul.tumblr.com/post/190972379710/mad-as-a-box-of-frogs-mittensmorgul-i-just

But canon has also informed us that despite having LIKED each other when they met in 11.11, Eileen did not become a major part of Sam’s life until we saw her again in 12.17. That’s fanon. The assumption that when we did see her again, that she and Sam had been carrying on a year-long relationship offscreen. We WANTED it to be true, because how many times has Sam had someone in his life like that? But canon has told us that despite that initial chemistry, they had not had that sort of relationship. Between 11.11 and 12.17, Sam never once mentioned her. And within a few episodes of 11.11, watching in real time, most of us accepted the fact that she was-- as a hunter and a legacy MoL-- a potential future ally, but like every other one-off episode hunter, not someone who had become central to Sam’s story. The vast majority of us... accepted that and moved on.

There was a LOT of excitement over the potential for her return in 12.17, but with the power of hindsight, and s15 literally doubling down on the fact by literally making Eileen’s return a direct manipulation by Chuck for this exact purpose, when she died in 12.21 for Sam’s pain, we took our outrage at that ending for her and began writing fix-it fic, headcanoning that she couldn’t really be dead, and inventing a mythical romance between her and Sam filling in that entire year between the two times they’d actually interacted in canon. Because we were ANGRY. Rightfully so.

But canon has told us again that this did not happen. That wasn’t real.

Did they like each other? OF COURSE THEY DID!

Did they have the potential to have become a romantic couple? It really seemed possible back in 12.17, yes.

Did it actually happen that way? Canon says it did not. Sam himself repeatedly said it did not. That their relationship wasn’t like that. The fact that Eileen felt she had to leave after the events of 15.09 confirms it did not. If she knew for a fact that her feelings for Sam were real, if they’d established a romantic relationship before she died in 12.21 and therefore already had a solid foundation for their feelings for one another, she wouldn’t have felt conflicted about staying.

Look at it this way, and try to understand why--in addition to everything else I’ve written about s15, about Chuck’s manipulation, about the specific story he wants to unfold, about all the rest of what canon has been working through this season regarding Fate and Free Will and Chuck’s Will controlling the events of the story, how Chuck not only had Eileen stashed in Hell for two and a half years but then brought her back and arranged it so she was literally the only soul to escape hell to also escape Belphegor’s containment spell AND Rowena’s death spell, only to show up at the exact right moment after Chuck’s previous “lessons” to Sam and Dean had brought Sam to his lowest moment of hopelessness and tormented him with horrific visions only to give him a moment of reprieve, and then orchestrated the entirety of 15.06 specifically to give Sam yet another false sense of hope before ultimately breaking him in 15.09-- I can’t ignore these facts, or convince myself that they somehow don’t apply, or can be overlooked for the convenience of insisting that there aren’t any seriously complicating factors in this singular case.

Again, if you’re able to do that, seriously, please, consider yourself lucky. And maybe try to understand how the phrasing of your message feels like it’s doubling down on the gaslighting.

I don’t know how many times I need to reiterate that I have zero objections to Sam and Eileen together as an endgame couple, but I can’t see them as already having established a romantic relationship. They literally had one kiss, and in context it was a “goodbye, but please know that I actually do like you, that part was real” on Sam’s part.

I mean... Dean canonically gave Jo a similar kiss in 5.10 right before she died. I don’t really see Sam and Eileen’s kiss any differently. I can’t. Because of ^^^ all of that. Dean and Jo’s kiss wasn’t the acknowledgement that they’d been carrying on a romance up to that point. It didn’t prove a canon romantic pairing here. It was a “if only this had happened differently, maybe we could’ve had a chance.” The difference here is that Eileen... is no longer dead. They do have a potential chance in the future, and I have never denied that. I have no idea what you believe you need to convince me of here, but until canon actually has Sam and Eileen express their desires and intents to pursue a romantic relationship in a way that isn’t inextricably tied to Chuck’s plot manipulations, I’m gonna stand on what I’ve already said. Please stop trying to convince me that Chuck’s manipulation isn’t very, very real. Because in my personal experience here, the manipulation is very, very real. Waaaaayyyyyyy too real for comfort.

And that is EXACTLY all the truth I need.

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NANCY D?EW: 2019 The CW

By: Brendan Rooney & Cory Dominic

Nancy Drew is a show like no other. It may not try anything new in the sense of structure or plot, but it does update the story of the source material which was written back in 1930. What was once a story about a teenage sleuth dealing with teenage problems and solving cases that could be always be solved by pointing at an adult is now tackling issues like loss of a parent, murder or even the supernatural.

The CW’s Nancy Drew, a story about a modern-day outta high school girl working at the local diner the Claw; torn between two realities of life leaving for college, and putting her troubled past behind her.

On the other hand, Nancy still plagued with the guilt of losing her mom and knows that nothing will ever be the same decides to stay in the desolate rural society of Horseshoe Bay for the concern of her father. The more she looks into the people of the town she notices the darkness within.

When one of the town socialites is murdered she and her friends are the suspects, but she must now try to uncover what actually happened. The B plot of the season is about a girl who died 20 years ago ala Dead Lucy; absentee Lawyer father Carson, and a whole lot of “CW Fog” this is new sexy Nancy Drew.

One of the flaws of Nancy Drew is that it tries too hard to fit into too many genres. The first distinction that many would think when they watch the pilot is that the screenplay is reflective of Pretty Little Liars, and the many other teen soap operas tangled with the mystery of murder.

However, the thing that makes Nancy Drew stand above from their predecessors is the spirit of character direction.

The beautifully stunning Kennedy McMann a fairly newcomer when it comes to the small screen shines as she perfectly plays the loveable too good for her own good Nancy.

McMann also brings a sense of conflict to the role of the sleuth with the plot-driven by inner monologues while she puts up a wall of emotions to keep everyone she holds closest away from her due to her tragic past of mortality not being a case she could solve with the loss of her mother.

Acting as a catalyst that keeps her trapped in the prison of Horseshoe Bay, and a schism that tears her family apart.

The supporting cast is Scott Wolf who plays Nancy’s Dad. Wolf brings a certain fresh take on a blue collared workaholic father. He is no stranger to the small screen though as he played Bailey Salinger on the hit 90’s sitcom Party of Five. Though he plays an adult on ‘Drew’ he plays it as such as if it were my own parents. A CW parent, but a parent nonetheless.

In addition to the stacked cast, I noticed from observation is that one of the bigger plot devices is based around loss, and in fashion, the five stages of grief.

The first stage is Denial. On the show, Nancy doesn’t come to grips with the cold truth that it was her mother who died was holding her back as if since her mother died she wasn’t able to live her life thus she put it all on hold and settled in her cozy life in Horseshoe Bay.

The second stage of Grief is Anger. Nancy definitely shows anger, she might not be mad externally but you can tell that the anger drives her from the first time Nancy mentions the loss of her mother. It’s a powerful acting ability displayed by McMann who captures the determination while also showing her softer sides in every scene she’s in.

The next stage of Grief is Bargaining. In Ep 4 Nancy is at her Mom’s grave. Somewhere she would never go to. Repressing the very thought of her mother being gone. However, the interaction McMann puts on display is triumphant. Her passion and emotion can be felt through the screen of someone who has lost everything and is now willing to ask for one more day with the deceased.

In closing the show is still new it may not be a hit with everyone, but it does have a little something for everyone it has drama, star-studded cast, great writing. So tune in to the CW Wednesdays 9 pm 8 Central

#scott wolf#party of five#kennedy mcmann#nancy drew#cw#riverdale#cw dads#stages of grief#hardy boys#drama#writing#writers

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Lemma the Librarian - The Last Dance”

Published: 14 April 2018*

http://www.mcstories.com/LemmaTheLibrarian/index.html

“The Last Dance” brings an end to the episodic nature of the series. Everything from here on out is welded quite tightly into the main plot - or, rather, the main plot constitutes what happens in the last three stories. Spoilers for “The Last Dance” from here on out. What seems like a straightforward get-the-book smash-and-grab (which involves Lemma and Iola going undercover in a harem, because @midorikonton knows which side her bread is buttered on) turns into the return of fairy murdergoblin “Red” for his third and final confrontation with Lemma. Red loses, although mostly thanks to Iason and Rhoda and Rhoda’s Machamp rage-demon Sonneillon. (Rhoda being, of course, the person Lemma used the ghost last time to call for.)

Lemma’s desire to be enslaved is something she’s been dealing with, more or less successfully, up until this point, but it’s something Iason and Iola don’t actually know about yet. That reticence is now coming back to bite her in the ass. The most important conflict in this story isn’t the fight against Red, or Lugal’s** magic clothes; it’s between Lemma and Iola over what the right course of action while trapped in the palace is. Lemma wants to give in, of course, but Iola’s experience with mind-control has been a lot more traumatic than Lemma’s, and she has a very strong personal/cultural “go down fighting” ethos, and she doesn’t seem to have this particular kink on any level anyways. We were reminded just last story of all of Iola’s trauma around the whole magical mind-controlled sex thing. But unlike that time, Lemma, for strategic reasons, doesn’t feel like she has to room to let Iola do her own thing. So she doesn’t just go along with the enchantments, she actively throws her magical weight behind glamouring Iola too. Iola doesn’t know the actual reasons Lemma did this, but I’m not sure it’d make a difference anyways: she would understand it, correctly, as just as awful a betrayal either way.

The party - now up to four with the addition of Rhoda - is off to Hattush to find the last, most apocalyptic book, and it’s all very dramatic. But what sticks with me the most about the end is Iola’s refusal to tell Lemma everything’s ok.

*Look, it was supposed to be out this week, but the EMCSA (my canonical reference for links and dates) is on a one week break, I’m travelling next week, and its been posted to Tumblr now. Also it’s been burning a hole in my drafts folder for nearly a month now. ;P

**His death at the hands of Red is a little abrupt, but he’s enough of a controlling jerk I can’t brink myself to feel too sorry for him. Plus, you know, dying abruptly is a peril of kingship. (If Red had murdered, say, poor Simta, I’d be a lot angrier; but Jenny seems to have learned her lesson since the Vamp!Brea business***.)

***Yes, I’m still mad. ;P

When The Fuck Are We? 🤷

For the first time, we’re further back in time than the Bronze Age Collapse! “Possession with Intent” is set in Khemeth, which is clearly K•m•t, Egypt*. Ancient Egypt is one of those things everyone at least knows a little about** so I’ll focus on two slightly more obscure points.

The first is Iason’s reference to Khemeth being “the breadbasket of the Inner Sea”, which is both true and false in an interesting way. Egypt, being spectacularly fertile, essentially one-dimensonal, and laid out on a lazy, easily navigable river, is indeed just about the optimum imaginable setting for extracting massive food surpluses with ancient technology and governance. But it wasn’t a big export from Egypt (Egypt’s main ancient export was papyrus, thanks to its ecologically-enforced monopoly). Rather, it was mostly used to pump up Egypt’s own population, and in particular the showpiece capital cities such as Memphis, Thebes, or Alexandria. In the ancient world, having an unnecessarily - nay, infeasibly - large capital was a point of pride, which is where Egypt’s actual role as a breadbasket comes in: after it lost its independence in 30BCE, the Romans told Alexandria to get stuffed and began exporting Egypt’s wonderful easy grain surpluses to Rome, instead***. But of course, there’s not much here to imaginably suggest that we’re in the Roman Empire, timeline-wise.

Which brings us to the other point: the party being around for the invention of pyramids is obviously just for the joke, but even discounting that Egypt is old. The usual comparison is to note that when Augustus began redirecting the Egyptian grain surplus to Rome, the pyramids at Giza were already older than Augustus is now. The Egyptian state that survived the Bronze Age Collapse was the already declining New Kingdom, third of the traditional old/middle/new kingdoms division of ancient Egyptian history; it’s the heir to a polity stretching back into the 31st C BCE. Egypt is old.

“The Last Dance” takes us to the one city-dwelling society even older than Egypt. Lagasch/Lagash is a Sumerian town, and Sumer (the south end of Mesopotamia, so modern-day south-central Iraq) has recognizable cities all the way back into the fifth freakin’ millennium BCE, and a historical record stretching patchily into the late fourth. Lagash ceased to exist as in independent city-state in the late third millennium*****, so about as long before our stop in Etruria as that was before Mercia, or Mercia is before the present day (and this story doesn’t seem to be taking place at the end of Lagash’s time as an independent polity, either). Based on some truly shoddy historical research******, we might slap this with a date of 2500 BCE - old enough to actually start getting close to the invention of the pyramids.

Sumerian, like Etruscan, is a language that seems to be unrelated to every other known language. (Before you come up with a brilliant theory that will revolutionize ancient history - no, they don’t seem to be related to each other, either.) Unlike Etruscan, we have such a huge corpus of text that we can translate it fairly reliably. (It helps that Sumerian remained in use as a record-keeping language for centuries after it had stopped being spoken - rather like Latin in Medieval/Early Modern Europe.) I’ve already mentioned the problems with king lists and such, but one of the great things about Mesopotamia is that unlike the logistical records of Mycenae, or the glorifying propaganda of Egypt, we have all of that and also preserved letters, and that lets us look so much further afield into the culture, you don’t even know. We even have recognizable preserved jokes: a regional administrator writes the central palace complaining that his requests for supplies to repair a dangerously deteriorating wall have been ignored, and it’s going to fall over and hurt someone. He demands supplies again, “and if you can’t send those at least send a doctor”.

Also, despite what Neal Stephenson will tell you, Sumerian is not glossolalic and you can’t use it to mind-control people.

*Look, you try transliterating Coptic into Latin characters! Like its distant relatives the Semitic languages, Coptic is based around consonantal root-words, into which vowels are slotted to make verbs, adjectives, and so forth. It makes for somewhat awkward transliterations.

**He says, and then panics trying to figure out how much people who aren’t actually historians have read about ancient Egypt. Tutankhamen’s weird Sun cultist dad is common knowledge, right?

***Rome’s peak in the Augustan period at a couple of hundred thousand, maybe a million****, was almost entirely on the back of the annona, a massive subsidized bread ration distributed to the Roman civic populace, and supplied in large part by Egypt. (It’s not terribly comparable to modern food stamps or other social welfare; in an ancient context, it’s more like spiking the football.) The population cratered between then and the burned-out husk the Goths and Byzantines squabbled over in the 6th C CE, but not because of the “fall of Rome”. Rather, the 4th C CE founding of Constantinople and the redirection of the Egyptian grain surplus there (so the new capital would bulk up to an appropriately prestigious population) was what really did it for Rome; and all of that happened when the Roman Empire was still riding high. The state of Rome was closer before and after the Visigoth sack than either was to Augustus’ city of marble.

****The brilliant if wildly opinionated historian Colin McEvedy had a great turn of phrase arguing for 250,000. (He has a great turn of phrase for everything, you should read him.) After laying out the more archaeological arguments about land use and suchlike, he notes that the one solid literary record for the annona we have, around the time of Augustus, gives a little less than a quarter of a million rations, and “who ever heard of a dictator who put a smaller figure on his largesse than he needed to. If [Augustus] had fed a million Romans he would have said so.”

*****We can peg it to exact years relative to related dates - the Mesopotamians were pretty through chroniclers, so we know how long kings ruled, in what regnal year they went on what campaign, and so forth, but they’re floating around in a little bit of a void. There are a couple of different possible chronologies depending on which recorded astronomical events you make line up with which calculated astronomical events.

******To wit, googling “Lagash king list dates” and looking for names that resemble “Lugal”. My historiography prof just shuddered and doesn’t know why.

~

Next time: the thrilling climax! Oh, man, does Lemma do some climaxing.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ESCAPE FROM BAGHDAD! BY SAAD Z. HOSSAIN

T. S. MILLER

ISSUE:

6 APRIL 2015

With an unembarrassed exclamation point to punctuate its classic pulp adventure title, Saad Z. Hossain's explosive first novel announces itself as something other than entirely serious. But readers in the early 21st century immediately understand that the desire to escape from Baghdad is the desire to escape from an unending nightmare, a geopolitical cataclysm that cannot be reversed—and perhaps can only be laughed at. Self-consciously outrageous and at times silly to the point of becoming sophomoric, Escape from Baghdad! achieves its true emotional impact through expressions of genuine wit bound to powerful meditations on the inanity of war, and on the special inanity of a particular 2003 war.

Of course, Hossain is not the first novelist to approach the traumas of armed conflict with a strong sense of the absurd—Vonnegut and Joseph Heller will spring to mind as obvious precedents—but, if a single modern war deserves to receive this kind of darkly satirical treatment, it would certainly have to be the Iraq War. Although I doubt that, for example, Hossain's farcical depictions of the dysfunctional bureaucracy of the American military command bear any resemblance to historical fact, these scenes finally seem no more outlandish than, say, Dr. Strangelove's portrayal of the same dysfunction, and operate similarly as a critique of power and violence. In terms of both sheer hilarity and profounder insight on war, Hossain's novel never quite rises to the heights of a Slaughterhouse-Five or Kubrick's inimitable melding of existential terror and absurdist humor in his 1964 film. Even so, Escape from Baghdad! remains an honorable new entry in this same tradition, and also refreshingly brings us a war story that focuses largely on civilians, civilians who, for instance, find that their financial assets have become "fictional" (23), and whose interpersonal relationships dissolve into nothing as family members become collateral damage and neighbors and acquaintances of all kinds begin to doubt one another's allegiances. Hossain ingeniously links the brutal chaos of post-invasion Iraq to the carnivalesque as a mode: a nation at war is necessarily a world turned upside-down, so why not turn it over to a few drinking, swearing, and wisecracking Lords of Misrule?