#slava stalin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Stalin, il terrore dei nazifascisti, dei liberali, dei padroni, dei revisionisti e dei corrotti.

Stalin, un gigante della storia, il più grande amico e rappresentante dei lavoratori e delle lavoratrici.

La sua Armata Rossa liberò Mezza Europa, il vero denazificatore.

Tutto ciò che dicono sui suoi "crimini" sono solo balle divulgate dai nazisti e accettate da benpensanti e democratici.

Putin gli può solo lucidare le scarpe.

GLORIA IMPERITURA A STALIN E ALL'UNIONE SOVIETICA.

0 notes

Text

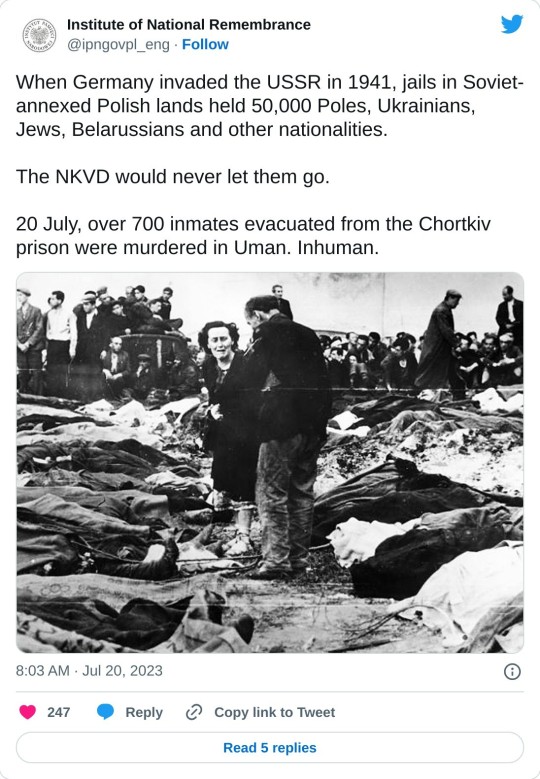

#stalinism#nkvd#soviet jails#Uman massacre#1941#soviet annexed polish lands#german invasion#russian imperialism#ukraine resistance#i stand with ukraine#slava ukraini#ukraine & poland

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

fixed me and made me more insane at the same time

Many such cases

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Not that we here at this blog are overtly political but since today’s a particular occasion in world history, I feel like this review of this particular film is something I will gladly share in this post

Credit for the video goes to History Buffs

1 note

·

View note

Text

never read anything more accurate

enver hoxha’s ‘with stalin’ reads like a teenage girl’s diary entry from the day she was partnered with her crush on a class project. he wrote it with a feather-ended glitter gel pen, laying on his bed kicking his feet up in the air behind him.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

What broke you to go from communist to liberal?

Hey thanks for the ask. I apologize my answer ran a little long. Here's a kinda summary with the bulk of my info under a readmore:

I had been getting deradicalized for a while by engaging with the news-- real news, both written text articles and video broadcasts, from many different sources. I had stopped relying on Tumblr, Twitter, and Reddit for my primary news and places of political discussion. I'd been getting more into learning about history, particularly 20th century history. Just generally getting more engaged with the real world and less absorbed with online leftist theoretical discourse.

So it'd been a long time coming.

As for the straw that broke the camel's back, it was summer or autumn of 2023. The thing that pushed me over the edge was all the lying. The uneven application of morals. The disinformation. The massive amount of believing whatever the fuck we want to believe despite evidence and calling everything else propaganda.

We (leftists) celebrated the Soviet Union, celebrated Stalin, celebrated Che Guevara and Karl Marx and whitewashed the bad aspects of all those individuals. We denied the existence of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, denied the Holodomor, denied Guevara's antiBlackness, denied Marx's antisemitism. We love the hammer-and-sickle, red-and-gold flags but at the same time we decry the Soviet Union as "not real communism" when we get pressured.

We said Trump and Hillary Clinton were the same. Biden and Trump were the same. We said gun control measures need to be frustrated by any means necessary. We said Slava Ukraini! from 2022-2023 up until another cause that we deemed more important came along and we either forgot about Ukraine or some of us started supporting Russia to ideologically cohere with the new cause.

The way we revere The Revolution as if it's not the same exact thing as Evangelicals revering The Rapture. We see the events of October 7, 2023 and go "wahoo hell yeah fuck 'em up!!! lets fucking go dude this should happen 100,000 times!" as if that's not one of the most plainly fucking evil things anyone could say and flying in the face of all leftist thought. We lie about Jews and Palestinians living in peace before the creation of the modern state of Israel. In any conflict, anywhere, in any time period, we lie about death tolls and number of civilian casualties and we distort and amplify atrocities when The Bad Guys do it while we minimize or handwave atrocities when Our Guys do it.

There's so much more. I could write you a novel about this. We are NOT consistent in any way, with anything, ever. We lie to suit our needs just like far-rightists do. We just think our causes are sufficiently good to warrant all the lying, whereas we (rightfully) know that right-wingers are unjustified in doing the same thing.

The way my personal politics have changed is shifting from observance of a political title, of a coordinate pair on the political spectrum, to observing what's evidently, demonstrably true. It is of critical importance to me that I take political action based on reality. My experience-based assessment of modern Communism and general internet-centric leftism is that it's just based on Vibes; it's like, political action doesn't have to correspond with what's really happening, it just has to sound good or feel gratifying to represent. That shit is oil-and-water with me and so I'm no longer a Communist myself. I ended my last relationship because in order to stay in good terms with the other person, I had to literally believe things that are not true about the world so I could be enough of a leftist for them. and that's not in any way an isolated incident.

I don't really call myself any particular political label now, I just vote for the most beneficial candidate, work to treat people with kindness interpersonally, work to improve myself and my communities, and keep myself informed of empirically true facts about the world and events both current and past and apply that knowledge how I can to benefit others.

Forgive me I am incapable of being concise😝. I hope this answers your question and isn't too rambly. I appreciate the ask and I hope you have a great day/night.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

How long do you give Putin now that he's shown this much weakness?

Unless an actual full-blown civil war takes place, Wagner will be either destroyed or mitigated within 6mo (more than likely less than that). Putin’ll be like Saddam or Stalin in that he’ll be in power until his dying day or until a larger force (NATO) ousts him and he’s executed for his crimes. And that shit better be recorded on something better than a motorala flipphone.

But historically Russians have been subservient and cowardly when it comes to following their leaders, so I doubt a civil war will go far. Russians will boast about this being some kind of unity for the motherland or some other nonsense, but it’s really just genetic cowardice. Say what you want about America, but at least you can’t call them cowards when it comes to tyranny. Fuck, even France is braver, not wasting a single second to burn down paris over a slightly crooked leader.

Anywho we’re living in the call of duty timeline where Russian loyalists, ultranationalists, and western-backed separatists are all fighting in a pseudo-civil war. Slava ukraiini, inshallah the Russian Federation will dissolve. 1000 years of shameful history.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Putin wanted a place in the world's history books? He will get it - right next to Stalin, Hitler, Lenin and others similar to him "leaders".

Ukraine and president Zelensky meanwhile will have a place in the same books as heroes.

Slava Ukraine!

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Let's celebrate together the 70th anniversary of death of Joseph Stalin!!!🥳🍾🎆🎉 with sincere wishes of the most miserable death for all bloody russian and not-russian dictators for thousands of years!!!

Free Borsht. Print. https://www.redbubble.com/shop/ap/50646135

#stalin death#joseph stalin death#death to putin#death to russian dictators#slava ukraini#ukraine 🇺🇦#cool day for b-day🙃

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Observers have long compared Vladimir Putin’s regime in Russia to Alexander Lukashenko’s rule in Belarus. When protests swept the latter country in 2020 (only to be forced back into submission as winter set in), many speculated that Russia might be headed down the same path. In 2022, Moscow launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and the domestic repressions against anyone who dared speak out against Putin’s policies did indeed reach an unprecedented level, but it appears to be only the beginning of the Kremlin’s crackdown. At Meduza’s request, Artyom Shraibman, a Belarusian political scientist and a nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center, explains what Russians can expect if their country continues moving in the same direction as Belarus.

The news that politician Vladimir Kara-Murza was sentenced to 25 years in prison, and the fact that Alexey Navalny, by all appearances, will get a similar sentence, has left a lot of Russians bewildered and afraid. But for Belarusians, this is just one more confirmation that Belarusian comedian Slava Komissarenko was right when he told his now-classic dark joke:

It’s like our two countries are watching the same TV show, but you’re only on the third season, while we’re on the fifth. And sometimes we glance over at you guys and say: “Get ready — it’s about to get very interesting!”

It’s not just a joke. When you consider the scale and the cruelty of the repressions, Belarus has been ahead of the Putin regime at almost every stage of Lukashenko’s rule. The only exception was the brief span between 2015 and 2019 when Minsk was trying to behave better in hopes of thawing its relations with the West. But then the “equilibrium” was restored. The failed revolution in 2020 sparked repressions so harsh that it’s hard to find a parallel in the post-Stalin histories of either Russia or Belarus.

Though there’s one exception to that, too: the premeditated murders of journalists and politicians. For Belarus, that was and remains an extremely unusual measure that Minsk has taken only once: in 1999–2000, when the authorities abducted and most likely killed two Belarusian politicians, Viktor Gonchar and Yury Zakharenko, as well as journalist Dmitry Zavadsky and businessman Anatoly Krasovsky. At that time, even the official investigation found that security agents linked to Lukashenko, Viktor Sheiman and Dmitry Pavlichenko, were involved in the operation.

In Putin’s Russia, meanwhile, the murder (and attempted murder) of journalists and intelligence defectors has been a constant.

But when it comes to other repressive practices, the Belarusian security forces really are more brutal and less selective — and they seem to be a step ahead of their Russian colleagues. It’s not that there’s a specific channel through which the Belarusian authorities pass their knowledge to the Putin regime. To move on to new forms of violence and human-rights restrictions, the Russian authorities don’t need to “peek” at what the Belarusians are doing; it’s not a matter of patents or “know-how.” Every regime goes down this path at its own pace. But because Belarus started the process first, it does make sense for Russians who want to know how Putin’s regime will degrade further to look to its Western neighbor.

Torture is routine

During the country’s 2020 protests, detainees were beaten as an additional preventative measure, in case 15 days in prison proved too light a punishment to deter them from protesting again. These days, beatings and torture and more often used when people refuse to unblock their phones, or when security agents want revenge for what they see as a personal affront — for example, when a suspect is believed to have leaked officers’ personal data.

In addition to physical violence, the authorities have begun using the tactic of humiliating people on video. In June 2022, security agents forced an arrestee to use a needle and ink to remove a tattoo that included a swastika. Other activists have been forced to draw things or stick protest symbols on their faces before recording “apology” videos.

Another practice that falls under the umbrella of physical violence is the administrative detention of political prisoners. People often spend weeks at a time in extremely overcrowded cells without mattresses, showers, opportunities to walk around, or the ability to receive packages from outside (in some cases, family members are allowed to send medicine), correspond in writing, or see a lawyer. They’re awakened twice per night and the lights are left on 24 hours a day. Many have reported being subjected to cold torture (when prisoners are left in cells with no heat and their blankets are confiscated). Prisoners serving sentences on felony charges experience numerous restrictions as well, but at the moment, the authorities’ treatment of administrative prisoners appears to be significantly worse.

Everybody’s an ‘extremist’

In early May 2023, Belarusian human rights advocates have counted almost 1,500 political prisoners in the country (which has a total population of a little more than 9 million). But even this number, they’ve said, is an undercount, as many people are reluctant to report the arrests of their relatives for fear of making their situations worse.

The majority of the country’s political prisoners have been convicted for one of two reasons: either they took part in the 2020 protests, or they allegedly engaged in “defamation” and were charged with “improper expression of one’s opinion.” This includes the Belarusian Criminal Code’s articles on “insulting the president” or other officials, “fomenting hatred” against societal groups (such as security agents), and “discrediting the Republic of Belarus”.

The concept of “fomenting hatred” is interpreted extremely widely; it can apply to as little as a rude word written on social media or in a community chat group against riot police in general. Hundreds of people have been jailed for expressing happiness about the death of a KGB officer during the raid of Minsk IT worker Andrey Zeltser’s apartment in the fall of 2021 or for conveying sympathy for Zeltser, who was shot in the same incident.

Participating in a protest becomes a felony offense in Belarus if a person enters a roadway during the demonstration. The pertinent article in the Criminal Code, which prohibits “organizing, preparing, or actively participating in actions that blatantly violate the public order,” has earned the nickname “the people’s article” for the number of citizens it’s been used to sentence. Walking around Minsk or any other city during one of the country’s Sunday protest marches in 2020 was enough to land a person in jail for up to four years. To this day, the authorities have continued arresting people for allegedly participating in those marches, using photos to identify people who don’t even remember being there.

The Belarusian authorities also apply laws against “extremism” more liberally than their Russian counterparts. Almost all non-state media outlets (including Zerkalo.io, Nasha Niva, RFE/RL's Belarusian service, and Belsat), as well as many popular Telegram channels (Nexta, Belarus Golovnogo Mozga), blogs (such as those of opposition politicians Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya and Valery Tsepkalo), and even chat groups, including some neighborhood ones in which participants discussed protest activity, have been declared “extremist.”

Subscribing to an “extremist” channel on Telegram is a misdemeanor offense. In many cases, to uncover these violations, officers order suspects to unlock their phone before searching through their messages and attempting to restore deleted files. In 2021, one married couple spent more than 200 days in custody for news articles they sent to one another in a private chat.

Even worse is the treatment of people caught working or interacting with organizations that have been declared “extremist formations.” This category includes anybody who has provided information or even comments to independent news outlets. Leading military expert Yegor Lebedok is currently serving a five-year prison sentence for two interviews he gave to the “extremist” outlet European Radio for Belarus. The wife of well-known blogger Igor Losik (who’s currently serving a 15-year sentence) was sentenced to two years in prison for telling a story about her husband to the Poland-based independent TV channel Belsat. The couple’s four-year-old daughter now lives with her grandparents.

The BySOL and ByHelp foundations, which were founded in 2020 to raise money to support victims of repressions, were declared “extremist” in 2021, which retroactively made every donation to the organizations a felony offense. But because the donations numbered in the tens of thousands and many of them came from IT workers who managed to flee the country, the authorities decided not to pursue charges against every offender and to exact payments from them instead. Many people whose bank cards appeared on donation records received visits from KGB officers who suggested they make “donations” to state-run charities several times larger than the payments they made to help repression victims. The agents promised not to open criminal cases against those who signed confessions, but the documents give the authorities yet another means of pressuring these people in the future.

But anti-extremism laws aren’t the Lukashenko regime’s only means of purging the country’s third-sector organizations; they’ve also had no qualms about simply dissolving them. The authorities didn’t arrive at this approach through trial and error, nor did they waste time with hybrid forms of repression such as declaring groups “foreign agents.” Instead, beginning in June 2021, after the latest round of European sanctions, security agents began liquidating hundreds of NGOs, including ones that weren’t involved in opposition politics even tangentially. The targets included environmental associations, historical societies, cultural organizations, charity foundations, organizations for disabled people, groups for Lithuanians and Poles living in Belarus, and urbanist, birdwatching, and cycling clubs. Acting on behalf of a non-registered organization is also a felony offense.

Repression, the Belarusian way

All of the repressive practices outlined above are familiar to Russians, albeit on a smaller scale, but there are a number of other methods that are frequently employed by the Lukashenko regime that aren’t yet common in Russia.

In the last few years, the Belarusian authorities have held many of its high-profile legal proceedings behind closed doors, refusing to allow even the suspects’ relatives to attend. As a result, the details of many cases, including sometimes the defendants’ names, remain publicly unknown. And in open trials, police officers serving as witnesses, who often give boilerplate testimonies about how a suspect “was walking down the street, started cursing, and resisted arrest,” are allowed to use pseudonyms and wear masks so that they can’t be identified later.

Often, the authorities try to force well-known political prisoners and opposition leaders to observe this “regime of silence,” including by disbarring and arresting their lawyers. Alexey Navalny’s regular Twitter threads, for example, wouldn’t be possible in Belarus, because his lawyers could lose their licenses or wind up in prison simply for trying to transport his political statements out of prison.

Another difference between the Belarusian and Russian systems is that the former allows the death penalty, while Russia has imposed a moratorium on the practice. In the spring of 2022, the Belarusian authorities decided to expand the set of offenses eligible for capital punishment, making it applicable to “attempted terrorist attacks.” In March 2023, “state treason” became punishable by execution as well (though the authorities have yet to use this approach).

In early 2023, Minsk decided to revive the Soviet-era practice of depriving political emigrants of citizenship obtained through birth; the law will come into effect in July. By all appearances, the government plans to apply the new law to exiled opposition leaders, who have already been sentenced in absentia to long prison terms.

In some of its less brutal forms, the Lukasheko regime’s repressions stand out for their thoroughness. For example, the Belarusian authorities now keep a registry of hundreds of thousands of citizens who either appeared on their radar for political disloyalty — by participating in protests, for example — or who simply voted for other presidential candidates in the 2020 election. Since 2021, depending on the severity of their “crimes,” these people have been systematically fired from government agencies, banks, state companies, and public organizations, including medical, educational, and cultural institutions, and banned from reapplying for public-sector jobs.

The Belarusian government has also been known to pay extra attention to members of specific ethnic groups. Immigrants from Ukraine who work in public organizations, as well as Ukrainian citizens who have lived in Belarus for years, have reported being called in by the KGB for interrogations, sometimes with polygraph tests, as the authorities seek information about Ukrainian intelligence agencies. And government employees with Polish roots who receive “Polish Cards” — documents that entitle them to certain benefits if they move to Poland — have reported being forced to relinquish the cards in order to keep their jobs.

No end in sight

It’s impossible to predict whether Russia will follow exactly the same path that Belarus has in recent years. The sudden surge of repressions in Belarus had an obvious trigger: the attempted revolution in 2020. Russia’s crackdown over the last 15 months was sparked by the invasion of Ukraine. But there’s a real risk that Russians will face a significantly more far-reaching domestic clampdown when the Kremlin realizes it’s exhausted its potential on the battlefield, and it needs somewhere to channel its frustration. It might embark, for example, on a larger-scale purge of “traitors” and “domestic enemies” who it claims are preventing the country from uniting and keeping the army from winning.

But the most important thing Belarus can teach Russia is that it can always get worse. Yesterday’s “red lines” stop working; isolated excesses become the norm. Society adapts to the regime’s cruelty, and people who immerse themselves in the news start catching themselves feeling an alarming sense of relief when somebody’s sentenced to two years in prison instead of ten.

The government itself may not understand at every specific moment whether its clampdown has internal limits, but it gradually pushes the limits of what’s permissible. Repressions are like a gas. They always expand to fill the space available — until the ruling elites or society begin to resist.

This isn’t always because a specific villain decided to turn the terror up to ten. Repression is a self-replicating machine. They create a class of beneficiaries — career security agents for whom the fight against “enemies” becomes a career elevator, a Stakhanovite competition. As soon as these incentives start to work, they no longer need a command from above to start searching for new forms of cruelty.

The human psyche clings to the familiar, even if that means informal norms of coexisting with the state. But the Belarusian experience shows us that these norms are extremely unstable when the government is plunging into the abyss of reactionism, and society is too atomized and frightened to resist. The inability to realize in time that yesterday’s taboos no longer apply has cost many Belarusians their freedom. They failed to escape the threat because they didn’t believe the threat was possible.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#russian imperialism#soviet crimes#stalin#stalinism#soviet union#stop russian invasion#slava ukraini

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

«[...] Prima, sapevamo delle crudeltà tra di loro: tra le diverse popolazioni di lingua slava ma di appartenenze etniche, politiche o religiose, diverse. Sapevamo per esempio della lotta feroce fra i cetnici, sostenitori di re Pietro, e i partigiani di Tito. Lussinpiccolo, nel ‘43, fu occupata dai cetnici, che arrivarono con le loro famiglie. Poco dopo giunsero i partigiani di Tito: presero tutti, compresi donne e bambini, li caricarono sulle barche, li portarono al largo e li annegarono...

Noi sapevamo. Ma pensavamo che tutto questo non ci riguardasse. Churchill, Roosevelt e Stalin ci avevano garantito a suo tempo che ogni popolo avrebbe comunque deciso dei suoi destini; noi eravamo italiani, e tali saremmo potuti rimanere. A tal punto ci avevamo creduto, che io, nel ‘42, se non ricordo male, avevo fatto ristrutturare completamente la nostra casa. E rimasi sbalordito quando uno dei muratori mi disse: “Questa casa, lei se la godrà ancora per poco...”. Quell’uomo era slavo, ed evidentemente sapeva ciò che io non sapevo, che tutti noi ignoravamo...

Arrivò il 1943, e gli slavi iniziarono a reclutare come partigiani, nel nostro esercito allo sbando, sia quanti si dichiaravano comunisti e loro alleati, sia quei poveri soldati che non sapevano dove e con chi andare, e neppure avevano i mezzi per tornare a casa. In quella circostanza si rifornirono anche delle armi che sino ad allora non possedevano.

E arrivò anche il 1945: entrarono in città, a Pola, dove cominciarono col prendere possesso delle caserme, del municipio, degli edifici pubblici, di qualche villa privata. Durò quarantacinque giorni, e poi giunsero gli Alleati: noi credevamo fosse per restituirci a noi stessi; in realtà fu solo per garantirci la possibilità di andarcene, esuli, ma vivi... E noi, di andarcene, lo decidemmo subito dopo l’occupazione e i primissimi momenti di sbalordimento atterrito: decidemmo non appena fummo in grado di capire che per noi non c’era più speranza, che se fossimo rimasti avremmo dovuto vivere nel terrore quotidiano. Perché non fummo noi, a volercene andare; la verità era, ed è, che “loro” non ci volevano su quelle terre, di cui pretendevano di cancellare, insieme alla nostra presenza, anche la storia...».

Anna Maria Mori & Nelida Milani, Bora. Istria, il vento dell’esilio

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://youtu.be/jOtYV9ZcjdA?si=ybol8gpYjmbcR7Av

This historian is right on the button with his take on how dictators like Putin think...and what is a shame is that his intelligence can get so warped, that he becomes a prisoner if his own design seeking external causes to deflect from issues at home and repressing an already submissive nation. Ukraine is a nation in its own right as are other republics in the federation whose local identities, Stalin-like dictators have quashed in recent times. Slava Ukraine.

0 notes

Text

Meduza's The Beet: Kaliningrad: An imperial gem and a thorn in everyone’s side

Hello, and welcome back to The Beet!

Eilish Hart here, the editor of this special dispatch from Meduza covering developments across Eurasia. If someone forwarded you this newsletter, you can sign up here to receive a fresh edition every Thursday. Some of our stories, like last week’s report about Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan’s contentious border deal, are available on Meduza’s website, but others are exclusive to subscribers — the more the merrier!

Last September, Vladimir Putin kicked off the school year more than a thousand kilometers from Moscow — in Russia’s western exclave of Kaliningrad. After addressing an audience of star pupils, Putin opened the floor for questions, and a teenage girl immediately confronted him with her concerns about the future. “What plans does Russia have for the development of biotechnology and bioengineering,” the 17-year-old asked, “under the present circumstances, when we’ve been cut off from so many foreign technologies?” Skirting the topic of international sanctions and the brutal war that triggered them, Putin gave an evasive reply: “Regarding the issue of someone cutting someone off from something, that’s really hard to do in the modern world. [...] Can you imagine it? It’s practically impossible.”

A birds-eye view of Kaliningrad, Russia. August 2017.

LARS BARON / GETTY IMAGES

Ironically, Putin was visiting a corner of Russia where the effects of being “cut off” are felt in more ways than one. Bordering Poland, Lithuania, and the Baltic Sea, the Kaliningrad region has no land links to the rest of the Russian Federation. And prior to World War II, it wasn’t part of Russia at all. The territory changed hands as a result of the Allied victory, passing from Adolf Hitler’s defeated Germany to Joseph Stalin’s USSR. The Soviet authorities stripped the region of its German population and heritage, changing the name of its capital from Königsberg to Kaliningrad and turning a centuries-old port city into a restricted military zone. Since 1991, Kaliningrad has become even more isolated, geopolitically speaking, as its neighbors joined NATO and the European Union. But local residents enjoyed the perks of proximity to E.U. countries and, in recent memory, even saw their city open its doors to the world during the FIFA World Cup in 2018. Just a few short years later, however, the fallout from Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has left Kaliningrad and its residents “cut off” from Europe once again. Journalist Sergey Faldin reports for The Beet.

Kaliningrad: An imperial gem and a thorn in everyone’s side

By Sergey Faldin

In August 1944, British air attacks demolished most of the East Prussian city of Königsberg — literally “King’s Hill.” The next year, the German region became the first the Red Army entered on the Eastern Front of World War II, as it secured essential ports along the Baltic coast on its way to victory in Berlin.

After four years of incessant fighting, starvation, and death, the Red Army saw the territory as a valuable “war trophy”; mass killings and atrocities against German civilians ensued. “The [Red Army] soldiers had all experienced the horrors of the German invasion. Nearly everyone in the Soviet Union had a family member or a friend who had died in the war,” Nicole Eaton, an Associate Professor of History at Boston College, told The Beet. “Everyone had gone hungry and had their lives torn apart by the German invaders. East Prussia, as the first German territory the Soviets entered, became a site of vengeance for them.”

Soviet troops fighting in the Königsberg suburbs in 1945. The officer in the background is firing a German submachine gun.

SLAVA KATAMIDZE COLLECTION / GETTY IMAGES

Having occupied the region, the Red Army stayed. At the 1945 Potsdam Conference, the Allies carved up East Prussia, leaving Königsberg and much of its surrounding territory under Moscow’s control. In 1946, Königsberg became Kaliningrad, renamed after the Bolshevik revolutionary Mikhail Kalinin. The city would go on to become a Soviet military outpost with access to the Baltic Sea, a strategic point of control in Europe. Thus, as Eatonwrites in her book German Blood, Slavic Soil, “Königsberg / Kaliningrad”became “the only city ruled by both Hitler and Stalin as their domain. Not only in wartime occupation but also as an integral part of their empires.”

More than half of Königsberg’s population of about 375,000 was either killed or displaced during the war. In its aftermath, the Soviet authorities initially prevented the region’s remaining Germans from leaving, only to deport them en masse in 1947–1948. “The region is unique in one aspect,” said historian Tomasz Kamusella, a Reader at the University of St Andrews, “which is that the history of its people dates back only to 1945.”

Indeed, by 1946, the Soviet program for “resettling” the Kaliningrad region had already started to gather speed, drawing settlers from across the Russian FSFR and, to a lesser extent, from Belarus and Ukraine. Having suffered through Nazi occupation and the destruction of their hometowns, many were ready to take the leap into new Soviet territory and rebuild their lives. By the early 1950s, roughly 400,000 people from across the Soviet Union had moved to Kaliningrad.

When the USSR collapsed in 1991, and the neighboring Baltic countries regained independence, the territory and its residents were cut off from the rest of the newly formed Russian Federation, turning the Kaliningrad region into an exclave, which by the early 2000s would find itself wedged between E.U. and NATO members Lithuania and Poland.

The newfound independence of former Communist states brought about an identity crisis: for the first time in 50 years, people in Kaliningrad could talk openly about what had happened to their city before and after World War II. “Suddenly, a new narrative was formed. Not just, ‘We came to build socialism on the ruins of fascism,’” said Eaton, referring to the Communist Party’s standard credo about Kaliningrad’s postwar construction. “People began thinking and talking about their German heritage in ways they hadn’t been able to before.”

‘Gdańsk is closer than Moscow’

Eaton describes the 1990s and early 2000s as a period of “post-1991 Euro enthusiasm,” when Moscow granted relative freedom to the regions, enabling them to elect their governments without Kremlin interference. But by the mid-2000s, “Putin was re-envisioning Russia’s economic policy and started giving special attention to regions like Vladivostok and Kaliningrad,” Eaton explained. “Moscow poured a lot of money into these regions to make them feel more ‘Russian’ because as cosmopolitan port cities they seemed to be slipping away and forming strong local identities.”

Pedestrians walk along a wall in Kaliningrad. March 2004.

OLEG NIKISHIN / GETTY IMAGES

“After 1991, we suddenly started to question, What is Kaliningrad? Kalinin’s city? But he was a Bolshevik, and we’re not communists anymore,” said Yury, a crisis psychologist from Kaliningrad who now resides in Tbilisi. “Are we Prussians then? But we have no ties to them except the architecture.”

A local border traffic agreement with Poland (which lasted from 2012 to 2016, allowing Kaliningrad residents visa-free travel to nearby Polish provinces for up to 30 days) fostered ties with Europe and helped shape the identity of the people in the region as “Russian Europeans.” Slowly, people began to acknowledge their city’s German past. “In 1995, Kaliningrad marked its 50th year as a [Russian] city; but in the early 2000s it was the 750th anniversary [of its founding],” Kamusella pointed out. “Everything that happened here is our history. Even the history of Prussia and the history of fascism,” a tour guide from Kaliningrad told The Beet.

Kaliningrad’s status as a “special economic zone,” along with its European location and liberal tax policies, turned the region into a lucrative investment opportunity. Some predicted that it would become a “Baltic Hong Kong.” Foreign investors helped fund urban renewal and reconstruction projects, as well as the creation of local history museums, transforming the birthplace of philosopher Immanuel Kant into an emerging tourist destination.

“They are surrounded by Europe; it would be stupid not to trade,” says Maxim Mihutsky, an IT entrepreneur from Belarus residing in the Polish city of Gdańsk, some 100 kilometers (62 miles) from Kaliningrad. Indeed, many Kaliningrad residents used their proximity to Europe to start small businesses selling E.U. goods, shaping the region’s reputation as entrepreneurial. “Everyone has a side hustle; that’s just who we are,” said Petya, a tourism student in Kaliningrad (whose name has been changed for safety reasons). Others relished living the cross-border dream: the largest IKEA in the region is in Gdańsk, just two hours away. “There’s this Polish shop on the border; it has some of the best pies, cheese, and sausages,” Petya recalled dreamily.

As of 2016, a staggering 82 percent of Kaliningraders had passports for foreign travel (by comparison, just 30 percent of Russians hold a passport in 2023). “I’m proud to be European, I’m proud to be the last part of Russia celebrating the New Year, and I’m proud of my Germanic ‘flavor,’” Sasha, a political activist from Kaliningrad (whose name has also been changed), told The Beet.

‘Not an opposition town’

In 2009–2010, Kaliningrad rattled the Kremlin with massive anti-government protests; Moscow had to dispatch a special envoy to quell the unrest. According to Sasha, who has been an active protester for the past decade, these were the region’s first and last large-scale protests. Some of The Beet’s sources speculated that the heavy military presence in Kaliningrad — the home of Russia’s Baltic Fleet — and an alleged influx of officials who purchased land for cheap could explain the increasingly depoliticized atmosphere in the region.

A rally against corruption and abuse of power in Kaliningrad’s Yuzhny Park. October 2010.

GL0CK / SHUTTERSTOCK

Kaliningrad saw a surge in political activity during the 2011–2013 Russian protests (also known as the Bolotnaya or Snow Revolution), but the movement was ultimately suppressed. “First, they canceled the special economic zone; then they stopped trying to turn Kaliningrad into anything other than just another Russian town,” said Yury. “After Bolotnaya, Kaliningrad couldn’t be independent anymore.”

Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014 escalated political repressions even further. The ensuing E.U. sanctions, together with the cancellation of the border agreement with Poland in 2016, also made it harder for Russians to travel to Europe.

“My friends and I tried to go out with posters, but it looked pathetic,” recalled Sasha, speaking of the later demonstrations that shook Russia in 2017, after Alexey Navalny’s exposé of then-Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev’s ill-begotten wealth. “Only ten or twenty people would go out on the streets. Kaliningrad is not and never will be an opposition town.”

After Putin appointed Anton Alikhanov to serve as head of the Kaliningrad region in 2018, the new governor claimed there was no “special Kaliningrad identity,” underscoring that half the population wasn’t even born in the region. “Having a Moscow-appointed governor does mean a greater connection to Moscow,” said Eaton, recalling her own time in Kaliningrad and how locals often spoke of the perceived benefits of a “strong” governor who supposedly had Putin’s ear. “But it’s [about] whose interests are being met – that’s always the question,” she added. When asked about his attitude towards the Moscow-appointed governor, Sasha replied, “He’s a good man, and he’s been doing many things for the region. But I’m sure he steals.”

Sasha was among the few in Kaliningrad who protested Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine. He recalled some 300 people taking to the city’s streets but said “nobody paid [them] any special attention.”

‘Nobody cares about the war’

After Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, some commentators raised the question of Germany’s historical claim to Kaliningrad. In response, Moscow began sounding the alarm about so-called “Germanization” (or “Westernization”), claiming that Germany (or other NATO countries) want to take back Kaliningrad and make it their own. Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov reiterated this rhetoric during a visit to Kaliningrad in 2021.

However, these concerns appear to exist solely within the minds of Kremlin politicians. “We Kaliningraders hate it when Muscovites come to our home and talk about Germanization,” said Sasha. “There was no Germanization, neither in the past nor the present. This is Russia, and everyone understands that.”

Central Kaliningrad. June 2022.

AP / SCANPIX / LETA

“Today’s Germany doesn’t harbor any projects of imperial conquest like Russia,” underscored Kamusella. “If there were any ideas today in Germany about taking back Kaliningrad they would be quickly silenced, mainly because of Germany’s War World II guilt and the utter impracticality of annexing a discontiguous territory where one million Russian citizens live,” Eaton concurred. “The potential secession from Russia, although a good story to sell by propagandists, is just not practical for anyone.”

In fact, against the backdrop of Russia’s war against Ukraine, Kaliningrad has only grown more isolated from Europe. Ever since Lithuania banned the transportation of E.U.-sanctioned goods to Kaliningrad in mid-2022 (a move Russian officials decried as an “illegal blockade”), Sasha’s father, a long-distance trucker, has been unable to find work. Many E.U. products that were once common in the region are no longer available on store shelves. “[There’s] odd juice boxes and Russian groceries I’ve never heard of instead of Lithuanian ones,” Sasha lamented.

Others, like Petya, do not connect these developments to the ongoing war. “When the special military operation [sic] began, my friends called me, worried,” he told The Beet, using the Kremlin’s official term for the 2022 invasion. “I was surprised: for us, nothing changed. We were, and still are, Russia. The war is in Ukraine.”

Nevertheless, the Russian exclave hasn’t been spared the war’s chilling effects. Last March, Russia’s Interior Ministry added two Kaliningrad journalists to its federal wanted list. Local activist Igor Baryshnikov, who criticized the war on social media, faces two criminal charges of spreading “false information” about the Russian military (the 64-year-old’s trial was postponed indefinitely after he was hospitalized in February). One of The Beet’s contacts from Kaliningrad declined to give an interview, citing concerns about being blacklisted as a “foreign agent.”

Last March, Alexey Milovanov, a Kaliningrad journalist and the former editor-in-chief of Novy Kaliningrad, found a sign taped to his apartment building’s front door that read “Zдесь жиVёт предатель”— “A traitor lives here” (with the capitalized Latin letters “Z” and “V” that have become key symbols in the Kremlin’s war propaganda). Milovanov posted a photo of the sign on his Telegram channel, commenting, “Ordinary fascism. Surprised it took them so long.”

Journalists at Mediazona report that some 180 killed soldiers from the Kaliningrad region are among the 18,000 independently confirmed Russian casualties in Ukraine. Recent viral videos showing mobilized troops from Kaliningrad and other regions refusing to fight and being called “cannon fodder” highlight the grim realities Russian draftees face. “We used to have a tradition in Kaliningrad,” Yury, the psychologist, explained, “that anyone who serves in the military [only] serves within the region. Seems that this tradition has been neglected.”

A pro-war “Z” adorns the facade of Kaliningrad’s Yunost Sports Palace. August 2022.

IGOR IVANKO / KOMMERSANT / SIPA USA / VIDA PRESS

Besides the initial sporadic protests and random arrests, Sasha says the atmosphere in Kaliningrad hasn’t changed much since February 24, 2022. “It’s as if nothing is happening,” he told The Beet. “Nobody cares about the war. Even the [lack of] transit [to the E.U.] isn’t affecting the mood. It’s demoralizing.”

Russia’s mobilization drive last September also provoked little backlash in the region. Sasha knows only one person who has been killed in action — “but he was a contract soldier” — and has another colleague who was called up last month and is now in Ukraine. “That one is still alive and texts me occasionally,” he said.

A great asset to an empire

In late 2022, Warsaw announced plans to construct a temporary “wall” along Poland’s border with Kaliningrad, citing concerns about Moscow potentially turning the exclave into an illegal migration route (along the lines of the 2021 E.U. border crisis with Belarus). “It took so long to tear down those walls from a historical perspective,” Kamusellatold The Beet. “Of course, we know why it’s being built, but as a historian, I also know that if erected, those walls will stand.”

“The wall has significant repercussions,” said Eaton. “In many ways, it’s a continuation of a repeating tragedy from the past century. The region, once a polyglot and multiethnic community of German, Polish, and Lithuanian speakers, became Germanized by the Nazis, and then was Russianized by the Soviets. It’s tragic because Kalinigrad’s residents after the Soviet collapse could engage in these great cross-border exchanges and cultural dialogues once again, but now no longer.”

Despite these developments, the consensus appears to be that Kaliningrad remains more of an asset than a liability to the Kremlin.

In 2018, a Russian official confirmed that Moscow had equipped the region with Iskander missiles — nuclear-capable rockets that could potentially reach not only the Baltic countries but also parts of Poland and, in certain circumstances, even Berlin. Experts debate if Kaliningrad is actually capable of launching nuclear attacks or if it’s just another Kremlin bluff. “I would say with 70-percent certainty there are nuclear missiles over there,” Kamusella said. “We all remember the Warsaw Pact and how that turned out.” (During the Cold War, the Soviet Union denied stockpiling nuclear weapons in Communist Poland, only to have their storage sites discovered after the Warsaw Pact dissolved in 1991.)

“As long as Russia and NATO exist, Kaliningrad will be a thorn in NATO’s side and vice versa. I find it difficult to imagine Kaliningrad changing hands unless this war catastrophically escalates globally,” Eaton speculated. “From an imperial perspective, Kaliningrad is a great asset,” added Kamusella. “An exclave surrounded by the enemy? It justifies whatever military measures Russia takes in that region.”

That’s all for now!

For more of Sergey Faldin’s reporting for The Beet, check out his last report on how Russia’s 2022 mobilization impacted the country’s HIV patients. Until next time,

Eilish

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Let us never forget on this day the millions of lives ended too soon in Holodomor.

1932-1933

#photography#history#Ukraine#slava ukraini#stalin#communism#genocide#black and white#statue#holodomor

4 notes

·

View notes