#sir samuel morland

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

138. Schänder - Schänder (Black/Death Metal, 2021)

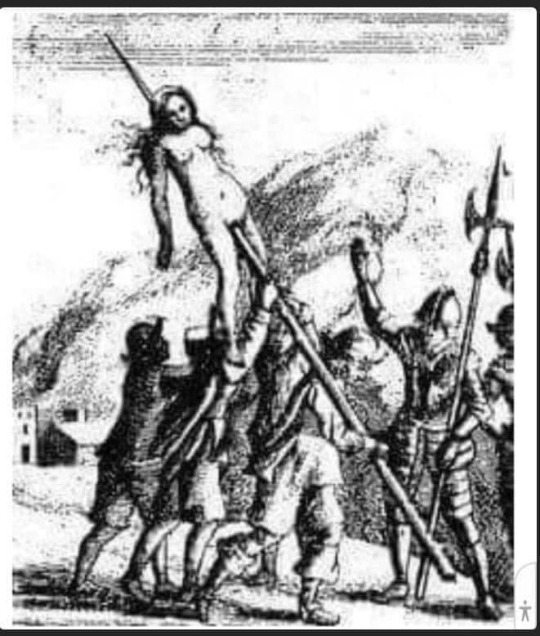

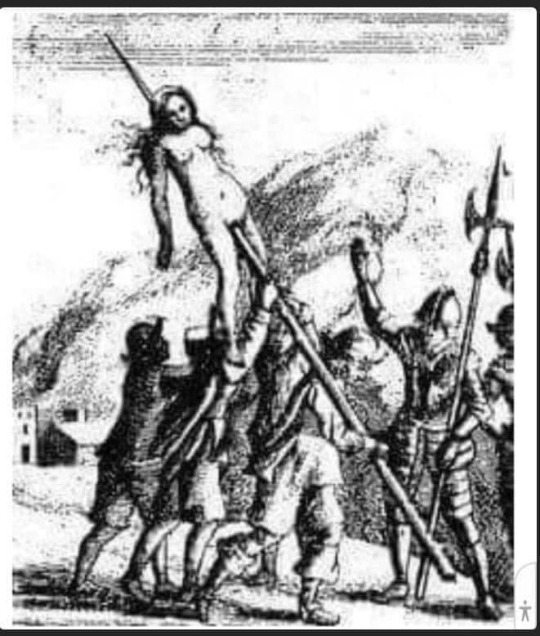

The illustration is out of "The history of the Evangelical churches of the valleys of Piemont" by Sir Samuel Morland - published in 1685.

The Savoyard–Waldensian wars were a series of conflicts between the community of Waldensians (also known as Vaudois) and the Savoyard troops in the Duchy of Savoy from 1655 to 1690. - These took place as a part of the European wars of religion.

#metal#black metal#art#artwork#music#heavy music#artist#cover art#heavy#illustration#sir samuel morland#war#17th century#history#impaled#england#austria#europe#battle

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Catherine Morland's parents are described as "plain, matter-of-fact people who seldom aimed at wit of any kind" and all we see on the page of her mother is definitely more plain sense than feeling sensibility. So it is very amusing to me that we also get this account of her taste in books, in a conversation between Isabella and Catherine:

“It is so odd to me, that you should never have read Udolpho before; but I suppose Mrs. Morland objects to novels.” “No, she does not. She very often reads Sir Charles Grandison herself; but new books do not fall in our way.” “Sir Charles Grandison! That is an amazing horrid book, is it not? I remember Miss Andrews could not get through the first volume.” “It is not like Udolpho at all; but yet I think it is very entertaining.”

The History of Sir Charles Grandison is an epistolary novel in six volumes from 1753 (so about 45 years old at the time of Northanger Abbey) by Samuel Richardson, and it features:

The beautiful, virtuous young orphan Harriet Byron, with a fortune of 15000 pounds, being pursued by a whole fleet of suitors.

The dastardly Sir Hargrave kidnapping Miss Byron from a masquerade ball and imprisoning her to force her into a marriage

The valiant Sir Charles Grandison coming to her rescue and fighting Sir Hargrave until he can bring her to safety

Miss Byron and Sir Charles falling in love but knowing that it cannot be, because! he is promised to another woman!

The other woman breaking off the engagement, the hero and heroine getting married, and then valiantly stepping up to help the Other Woman stand up to her family

Sir Hargrave dying of a dueling wound after mistreating yet another woman and leaving Miss Byron part of his estate to beg her forgiveness

It also includes a lot of moralising on religion, virtue, motherhood, and good society, which is probably why it a perfect pick for Mrs. Morland. It's all the thrill of abduction and rescue and devoted pining, but neatly dressed up in a morality tale about being good and proper. So you need not blush to say you enjoyed it and can even recommend it to your daughters.

It is also a book that is known for the constancy of its characters. Their morality, good or bad, is very fixed and plain to see. Which also fits with much of the Morlands' approach to people.

All I'm seeing is 16-year-old Catherine almost tripping over her feet to get to her mother with her current volume of Sir Charles Grandison clutched to her chest. Absolutely squealing with excitement over the Miss Byron being rescued from Hargrave's carriage by a virtuous nobleman who refused to even draw his sword because he abhors violence, while her mother placidly comments on how pleasant it is to see kindness and goodness so well reflected in literature.

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because no one else has taken the time to correct OP's absolute brain dead drivel lemme throw a couple things out there: 1. This sketch comes from The History of the Evangelical churches of the valleys of Piemont by Sir Samuel Morland published in 1658 (https://archive.org/details/historyofevangel00morl/page/344/mode/2up). According to the original source it's a depiction of the execution of a woman named Anna, daughter of Giovanni Charboneire. A couple things to note; firstly, this has absolutely nothing to do with the spread of Christianity and is almost a thousand years removed from the time of Charlemagne. The events depicted in the book are about the Savoyard–Waldensian wars which took place from 1655-1690 which was both a period of persecution by the nationalist churches against the Waldensian sect and territorial conflict between Savoy and France. At most we can say this was an intra-religious conflict in Christianity, nothing to do at all with OP's claim of witchcraft 2. Let's talk about witchcraft. Firstly, the Christian Church has since the time of St. Augustine institutionally opposed persecuting witchcraft because witches don't exist and have no power.

The Church affirmed that people may be self deluded into believing themselves to have powers but that this delusion was either the result of mental illness (to use a more modern idea) or was a diabolic influence on the mind, not in reality. See the Canon Episcopi for primary source data or Jeffery Davies, A History of Witchcraft in the Middle Ages for secondary reading. The main witchcraft craze and much over publicized witch hunts of the late middle ages were largely the result of Protestant/Catholic conflict in border regions following the Reformation, Puritan Salem being a notable exception. 3. Finally, the first major demographics to convert to Christianity in the Roman Empire were women and slaves because, uniquely opposed to traditional pagan religions, Christianity affirmed the inherent dignity and worth of all humans, not just the male elite. To quote Geoffery Blainey's Short History of Christianity: "Whereas neither the Jewish, nor the Roman family would warm the hearts of a modern feminist, the early Christians were sympathetic to women. Paul himself insisted in his early writings that men and women were equal. His letter to the Galatians was emphatic in defying the prevailing culture, and his words must have been astonishing to women encountering Christian ideas for the first time: 'there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Jesus Christ'. Women shared equally in what is called the Lord's Supper or Eucharist, a high affirmation of equality." TLDR: OP's claim is without any historic, theological, or intellectual merit. If one of my students gave me this I would give them remedial work on how to properly source information and do research.

This is just a reminder of how Christianity became so popular today.*

During the reign of Charlemagne, women were impaled on sharpened poles put in the vagina.

Slowly, over days, the pole would travel the length of the body through the organs, causing tremendous pain, simply because a woman was found collecting herbs in the forest. She was labelled a witch.

Their screams could be heard for days as an example to those who would not accept the foreign faith. Christianity became so popular because of sheer terror of what would happen if it wasn't accepted

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

John Jackson - Portrait of James Abercrombie, 1st Baron Dunfermline -

James Abercromby, 1st Baron Dunfermline PC (7 November 1776 – 17 April 1858), was a British barrister and Whig politician. He served as Speaker of the House of Commons between 1835 and 1839.

John Jackson RA (31 May 1778 – 1 June 1831) was a British portraitist.

John Jackson was baptised on 31 May 1778 in Lastingham, Yorkshire, and started his career as an apprentice tailor to his father, also John Jackson, who opposed the artistic ambitions of his son. John Jackson’s mother was Ann Warrener and he had at least one brother, Roger Jackson.

However, John enjoyed the support of Henry Phipps, 1st Earl of Mulgrave (1755–1831), who recommended him to the Earl of Carlisle; as well as that of Sir George Beaumont, 7th Baronet, who offered him residence at his own home and £50 per year. As a result, Jackson was able to attend the Royal Academy Schools, where he befriended David Wilkie and B. R. Haydon. At Castle Howard, residence of the Earl of Carlisle, he could study and copy from a large collection of paintings. His watercolours were judged to be of uncommon quality.

By 1807 Jackson's reputation as a portrait painter had become established, and he made the transition to oils steadily, if not easily, regularly forwarding paintings to Somerset House. After a visit to the Netherlands and Flanders with Edmund Phipps in 1816, he accompanied Sir Francis Chantrey on a trip to Switzerland, Rome, Florence and Venice in 1819. In Rome he was elected to the Academy of St Luke. His portrait of Antonio Canova, painted on this trip, was regarded as outstanding.

Jackson was a prolific portraitist, strongly showing the influence of Sir Thomas Lawrence and Henry Raeburn in his work. His sitters included the Duke of Wellington, the explorer Sir John Franklin and some noted Wesleyan ministers. His 1823 portrait of Lady Dover, wife of George Agar-Ellis, 1st Baron Dover, was widely acclaimed.

He was a Royal Academy student from 9 March 1805, was elected an Associate of the RA on 6 November 1815 and elected a full member on 10 February 1817.

John Jackson was married twice, the first marriage in 1808 was to Maria Frances Fletcher, the daughter of a jeweller, Samuel Fletcher. His second marriage in August 1818 was to Matilda Louisa Ward, the daughter of the painter James Ward and a niece of George Morland. He died in 1831 in St John's Wood, London.

He had three children with his first wife Maria: Maria Rosa Jackson was born in 1808 and died in 1888. His son Charles Fletcher Jackson was born in 1810 and died in infancy in 1811. His second son, John Edmund Jackson was born in 1816 and again died in infancy in March 1817. John Jackson’s first wife Maria also died in March 1817 shortly before their son John Edmund died.

Johns first daughter, Maria Rosa Jackson married Marmaduke Brewer and she later ran a school in Monmouthshire.

Jackson had three confirmed children with Matilda. His first son, Howard William Mansfield Jackson was born in 1824. His second son with Matilda, Mulgrave Phipps Jackson (baptised Phipps Mulgrave) was born on 5 August 1830 and died on 4 October 1913. A painter himself, he exhibited in the Royal Academy for 12 years. John Jackson also had a daughter with Matilda, also called Matilda Louisa born 1825.

There was also possibly a second daughter Ida Augusta Jackson, married Roeneke (27 December 1851, London – 6 January 1874, Florence), buried in the English Cemetery, Florence.[7] This daughter has not yet been confirmed by Ancestry.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What Jane Austen’s Novels Teach Readers

[via The Atlantic]

Before she was a writer, Jane Austen was a reader. A reader, moreover, within a family of readers, who would gather in her father’s rectory to read aloud from the work of authors such as Samuel Johnson, Frances Burney, and William Cowper—as well as, eventually, Jane’s own works-in-progress.

Characters’ choices of books are a frequent target of Austen’s satire. In Pride and Prejudice, the insufferable clergyman Mr. Collins chooses to orate from James Fordyce’s Sermons to Young Women one afternoon because (as he piously proclaims) he abstains from novels.

The narrator of Northanger Abbey declares novels to be works “in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.” Austen’s works exemplify these narrative possibilities, and extol characters who are capable of appreciating them.

When Persuasion’s Anne Elliot discusses literature with her new friend Captain Benwick, who is grieving over the death of his fiancée, she concludes that Benwick’s reading, which consists mainly of Romantic poetry, has deepened his sorrow in lost love (just as Marianne Dashwood’s does in Sense and Sensibility).

Throughout her novels, Austen satirizes both literary works and readers that represent two kinds of excess: those that are overly moralizing, and those that are overly romanticized. Shallow, pietistic, or narcissistic readers such as Isabella Thorpe, Mr. Collins, Sir Walter Elliot, and even, initially, Catherine Morland, are blind to the power of good books to offer both instruction and delight. Austen’s wisest, most admirable characters are those who turn to books for knowledge of things outside themselves—truths about the human nature common to us all. For these readers, among them Anne Elliot and Elizabeth Bennet, good character is cultivated in learning to read literature, other people, and oneself well.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Post has been published on Austen Marriage

New Post has been published on https://austenmarriage.com/1531-2/

Sifting Through Austen’s Elusive Allusions

Excellent researchers have divined many, many references and allusions that Jane Austen makes in her novels and letters. In his various editions of her works, R. W. Chapman lists literary mentions along with real people and places. Deirdre Le Faye’s editions of Austen’s letters include actors, artists, writers, books, poems, medical professionals, and others. Jocelyn Harris, Janine Barchas, and Margaret Doody have written extensively about people, places and things on which Austen may have based situations or characters. Some of Jane’s references are clear, some artfully concealed.

Yet we should be cautious about the great number of literary or historical finds uncovered by modern scholarship, because we often don’t know how many of these Austen knew herself. When a modern researcher cites an historical person from a couple of hundred years Before Jane, the marginal query must always be, “Did JA know this?” Many, she likely did. But probably not all. Maybe not even most.

Also, we don’t know how many references and allusions are tactical rather than strategic. Many authors include passing topical references with no other goal than to place the events of a novel in a particular time and place. A writer in 1960s America might show anti-war footage playing on a television. A current writer might mention a controversial American president or British prime minister. But unless a common theme directly connects the background references with the main storyline, these references are likely tactical rather than strategic.

Here, “tactical” means the reference has no profound meaning beyond the text. “Strategic” means an effort by the writer to establish a more general social, political, or historical context. A reference to a Rumford stove in Northanger Abbey, for example, is tactical, playing a newly invented appliance off the heroine’s expectations of dank passages and cobwebbed rooms. The naval subplot in Persuasion, on the other hand, is strategic. It incorporates not only the overall historical context but also the moral and intellectual contrast between the military men who have earned their wealth versus the wealthy civilians who are squandering theirs.

For many other items, it is difficult to determine the precise source. Education and literature in Great Britain then involved a small, fairly closed set of people. Limited common sources included the Bible, Shakespeare, and authors from the classical tradition. A common set of teachers came from the same small number of colleges using those limited sources. Everyone who admitted to reading novels drew on the same small pool of books.

It is conventional wisdom, for instance, that Austen took the phrase “pride and prejudice” from Francis Burney’s book Cecilia, where the capitalized phrase appears three times at the end. However, the literary pairing of “pride and prejudice” occurs elsewhere, including the writings of Samuel Johnson and William Cowper, two of Austen’s other favorite writers.

Even First Impressions, the original name for this novel, may have come from a common vocabulary. First impressions, and not being fooled by them, was a literary trope. In Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho, the heroine, Emily, and the secondary heroine, Lady Blanche, are warned not to rely on first impressions. This novel, shown above by the headline, is mentioned so often in Northanger Abbey that it is almost a character. The concept also arises in the works of Samuel Richardson. Austen may have borrowed from one of these specific authors. Or all the authors may have used a common literary vocabulary. Indeed, it was the recent publication of two other works with the title First Impressions that led Austen to change her title.

Another question is whether Austen knew the many layers of references that academics often point out. She apparently had free run of her father’s 500-book library, but we don’t know what it contained. As an adult, she had occasional access to the large libraries at her brother Edward’s estates at Chawton and Godmersham. How much she read of the classical material there, we don’t know.

Jane knew Shakespeare and the Bible well. She knew many poets, but would she have read a still earlier classical writer referenced by those poets? Did Austen know Shakespeare’s sources, which were often obscure Italian plays? We might be able to trace many connections back to the Renaissance or before, but she may have known only the immediate one before her.

Harris, Barchas, Doody, and others have given us multiple possible historical references to the name Wentworth in Persuasion. Austen might use the name to tie into this network of families and English history going back hundreds of years (strategic). Or she might use the name because of its fame in her day (tactical). The direct novelistic use is to contrast Sir Walter, who measures family names in terms of social status, with the Captain, who fills his commoner’s name with value through meritorious service. Sir Walter finally accepts Wentworth because of his wealth and reputation. He was “no longer nobody.” Yet the baronet can’t help but think the officer is still “assisted by his well-sounding name.”

Barring a letter or other source in which Austen states her purpose, we have no way of knowing whether Austen intended a broader meaning to “Wentworth” than its general fame. To some, the name in and of itself establishes the broad historical context. To others, it would take more than the three or so brief references to Wentworth, as a name, to show that Austen means to establish a meaningful beyond-the-book purpose.

Another consideration is that, cumulatively, commentators have found an enormous number of supposed references and allusions in Austen. Could a fiction writer, with all the work required in creating, writing, and revising a novel, have the time and energy to find and insert a myriad of outside references and allusions? Could a writer insert many references without bogging down the work?

Every writer who has tried her hand at historical fiction, for example, knows that too much history can overwhelm the novel’s story, leaving characters standing on the sideline to watch events pass by. Every external reference creates extra exposition that creates the danger of gumming up the plotline. It might also create a new emotional tone at odds with the characters’ situation or other complexities that must be resolved. We can’t underestimate the extra work for an author who already has her head full of practical book-writing issues—plot and character development—that need to be kept straight.

Finally, writers often plant things for no other reason than fun. In Northanger Abbey, John Thorpe takes Catherine Morland for a carriage ride early in the story. Barchas points out that he asks her about her relationship with her friends, named Allen, at just the point where their carriage would be driving past Prior Park, the home of Ralph Allen. This was the stone mogul who helped build Bath.

Austen does not explicitly call out the family home. Readers who know Bath’s geography and make the connection to the wealthy masonry clan get an extra chuckle. Readers unfamiliar with the geography, or with the wealthy Allen descendants, would not suffer from a lack of understanding.

All a reader needs to know is that Thorpe thinks the Morlands are connected to a very wealthy family, when in fact their friends named Allen are only modestly well-to-do. Thorpe’s misunderstanding drives the book’s plot. Very likely, all Austen wanted with the Prior Park allusion was to give a wink to the bright elves reading her book.

Thus the author may mean one thing, while later analysts might find something beyond what the writer ever intended. In Mansfield Park, for instance, Henry Crawford reads Henry VIII aloud. A broad interpretation might connect the attitude of the rogue Henry Crawford with the attitude of the rogue Henry VIII: Women and wives are interchangeable, expendable, to be taken at whim and tossed away at whim. Or perhaps the name Henry is nothing more than a tip of the hat to Jane’s favorite brother, Henry.

Austen may well have intended multiple levels of interpretation. But note that she has Henry Crawford himself say that Shakespeare is “part of an Englishman’s constitution … one is intimate with him by instinct.” Edmund Bertram agrees: “We all talk Shakespeare, use his similes, and describe with his descriptions.”

Others may feel that Austen deliberately weaves in as many references as she can. One must imagine her writing with a variety of concordances stacked to the ceiling. But she indirectly tells us of a different approach. One is “intimate” with Shakespeare by “instinct.” She knew the Bard and other writers in depth, and the references come out organically. Much more than by design, this fine writer pulls what she needs from history by “instinct.”

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

#18th century literature#Captain Wentworth#Jane Austen#Northanger Abbey#Persuasion#Regency era#Regency literature

0 notes

Video

instagram

muspeccoll -- We were challenged by @sfplbookarts to post seven days of #bookcovers without explanation or review.⠀ ⠀ Day 1: Morland, S. (Samuel), Sir, 1625-1695. The doctrine of interest, both simple & compound. London : Printed by A. Godbid and J. Playford, sold by J. Playford, 1679. HG1638.E6 M6 ⠀ ⠀ We challenge @ucmspeccoll! ⠀ ⠀ #goldtooling #beautifulbooks #antiquebooks #bibliophile #bookstagram #booklover #rarebooks #specialcollections #librariesofinstagram #iglibraries #mizzou #universityofmissouri #ellislibrary #7daysofbookcovers #7daybookcoverchallenge #judgeabookbyitscover

0 notes

Text

I am going to start posting about authors Jane Austen read, liked and by whom she was inspired. Please leave comments if you know more authors. This is a work in progress.

Books were an expensive luxury two hundred years ago. In 1810 a new novel would have cost around £100 at today’s prices, or around half a week’s wages for a skilled worker at that time.Purchasing new works of fiction would have been beyond the likes of the modest Austen family. Jane, who read extensively from a young age, relied on her family’s libraries, borrowing from friends and Circulating Libraries.

(via http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/0/21122727)

Here is a list of some of books the experts say were her favorites:

The first one is was an Irish novelist who’s early “Gothic” works had untold influence on Jane Austen’s life and writing. Austen admired her so much, that she sent her a complimentary copy of Emma when it was published in 1815.

MARIA EDGEWORTH

Read complete article here: http://www.janeausten.co.uk/maria-edgeworth-jane-austen

s-gothic-inspiration/

FANNY BURNEY

Another author that influenced Jane Austen was Fanny Burney, byname of Frances d’Arblay, née Burney.

(Born June 13, 1752, King’s Lynn, Norfolk, UK—died January 6, 1840, London). English novelist and letter writer, daughter of the musician Charles Burney, and author of Evelina, a landmark in the development of the novel of manners.

Source: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/85638/Fanny-Burney

SAMUEL RICHARDSON

The History of Sir Charles Grandison, epistolary novel by Samuel Richardson, published in seven volumes in 1754. The work was his last completed novel, and it anticipated the novel of manners of such authors as Jane Austen.

Source: www.global.britannica.com

This is said to be one of Jane Austen’s favorite books.

Another favorite of our dear Jane by Samuel Richardson.

Read more here: http://austenprose.com/2010/08/10/jane-austen-and-the-father-of-the-novel-samuel-richardson/

LORD BYRON

George Noel Gordon – Lord Byron at age 25 Portrait by Richard Westall -1813

Ann Radcliffe

(née, Ward 9 July 1764 – 7 February 1823) was an English author and a pioneer of the Gothic novel. Her style is romantic in its vivid descriptions of landscapes and long travel scenes, yet the Gothic element is obvious through her use of the supernatural. It was her technique of explained Gothicism, the final revelation of inexplicable phenomena, that helped the Gothic novel achieve respectability in the 1790’s. It also gave Austen the material for Northanger Abbey, in which 17-year-old Catherine Morland is obsessed with Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

SAMUEL JOHNSON

Mentoring Jane Austen: Reflections on “My Dear Dr. Johnson”

Read more about his influence here: http://www.jasna.org/persuasions/printed/number11/gross.htm

ROBERT BURNS

https://janeausteninvermont.wordpress.com/2013/01/25/jane-austen-and-robert-burns/

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

What did Jane Austen read? I am going to start posting about authors Jane Austen read, liked and by whom she was inspired.

0 notes

Text

Vade mecum: or, The necessary pocket companion.

Vade mecum: or, The necessary pocket companion.

Before the iPhone, Uber, GPS… 847F John Playford ca. 1655-1685/6. Vade mecum: or, The necessary pocket companion. Containing, I. Sir Samuel Morland’s Perpetual almanack, … curiously gra… Source: Vade mecum: or, The necessary pocket companion.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Vade mecum: or, The necessary pocket companion.

Vade mecum: or, The necessary pocket companion.

Before the iPhone, Uber, GPS… 847F John Playford ca. 1655-1685/6. Vade mecum: or, The necessary pocket companion. Containing, I. Sir Samuel Morland’s Perpetual almanack, … curiously graved in copper; with many useful tables proper thereto. II. The years of each king’s reign from the Norman Conquest, compar’d with the years of Christ. III. Directions for every month in the year, what is to be done…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

so I did a bit of googling, and this is basically all bullshit. this image is attributed to the Piedmontese Easter of 1655 (Charlemagne died eight centuries beforehand so that's a load of bunk), allegedly a massacre that occurred after a group of Waldensians (a sect of Christianity) in the Franco-Italian Alps were ordered expelled by the Catholic Piedmontese but stayed in their homes.

thus, the local government allegedly sent troops to remove the Waldensians and it descended into the massacre that's depicted where anywhere from 1,000 to 6,000 people were killed.

I say allegedly because almost every single source on the subject was written almost directly after the event (including this image that came from a 1658 English manuscript by Sir Samuel Morland) which complicates things because, as became quite evident when you actually look at the sources, they were all written by PROTESTANTS. y'know, the group that had a vested interest in making Catholics seem barbaric and bloodthirsty.

you gotta remember that the 30 years war hadn't even been over for a decade before this alleged massacre, the Catholic/Protestant divide was still a hot topic issue. and to make it worse, almost all modern sources I've found echo those same Protestant sources from around the time period.

so I feel safe in saying the image is either grossly exaggerated (which is still horrible, but nothing really unique to religion) or even flat-out false to tar Catholics

This is just a reminder of how Christianity became so popular today.*

During the reign of Charlemagne, women were impaled on sharpened poles put in the vagina.

Slowly, over days, the pole would travel the length of the body through the organs, causing tremendous pain, simply because a woman was found collecting herbs in the forest. She was labelled a witch.

Their screams could be heard for days as an example to those who would not accept the foreign faith. Christianity became so popular because of sheer terror of what would happen if it wasn't accepted

2K notes

·

View notes