#since today is German reunification day

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

OMG guys. Look what I found!! Ryan is a time traveler. Or a vampire. And maybe part German. In any case, he was at the fall of the Berlin wall.

Maybe he even brought it down, who knows. Certainly wasn't The Hoff, despite what he claims.

#ryan gooseman#ryan guzman#911#911 cast#lololol#he looked very late 80s to me#so I had to#Berlin Wall#German history#since today is German reunification day#which is NOT the day the wall fell#but the day the two Germanies were officially reunited almost a year later#the fall was 9th Nov 1989

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The crisis of the world - 1933 and 2023

Thomas Weber

Memorise content

What does 1933 teach us? If we understand National Socialism as a form of illiberal democracy, we can see that today's variants could easily slide into something worse. Then as now, exaggerated perceptions of crisis play an important role.

In times when several major crises are brewing into what is perceived as an existential poly-crisis, fears of the political consequences of this perception spread. The most spectacular case of the collapse of a democracy - the collapse of the Weimar Republic in January 1933 - is therefore repeatedly scrutinised in the hope of discovering lessons for the present.

A prime example of this in recent years is what has been happening in the United States: since the New York Times columnist Roger Cohen greeted his readers with "Welcome to Weimar America" in December 2015, "Weimerica" has developed into a veritable genre of opinion pieces and books. After the attack on the Capitol in Washington in January 2021, the son of an Austrian SA man also used his fame as a Hollywood actor and former governor of the US state of California to record a video message to the world: In it, Arnold Schwarzenegger spoke about his father and drew direct comparisons between the Reichspogromnacht, the Nazi anti-Jewish pogrom of 9 November 1938, and the situation in the US in early 2021. to resolve the footnote[3]

It is therefore not surprising that Adolf Hitler is more dominant in public discourse today than he was a generation ago. Between 1995 and 2018, the frequency with which Hitler was mentioned in English-language books rose by an astonishing 55 per cent. In Spanish-language books, the frequency even increased by more than 210 per cent in the same period. To break up the footnote[4] This increase is a result of both a growing perception of crisis and another phenomenon: an awareness of how much the world we live in today can be traced back directly and indirectly to the horrors of the "Third Reich" and the Second World War.

But the world that emerged in 1933 is not invoked everywhere in order to understand and interpret today's situation. Strangely enough, one country in the heart of Europe has taken a different direction: Germany itself. Here, the frequency with which Hitler was mentioned in books fell by more than two thirds between 1995 and 2018. The same trend applies to other terms that refer to the darkest chapter of Germany's past, such as "National Socialism" and "Auschwitz". To resolve the footnote[5] However, a declining interest in National Socialism should not lead to the false assumption that today's Germany is less strongly characterised by the legacy of the "Third Reich" and the horror that the Germans spread throughout Europe. The legacy of National Socialism defines who the Germans are, and has done so since the day Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor in January 1933.

New "special path"

In Germany, there was probably not so much explicit publicity about National Socialism because it was believed that the country had learnt from the past and built an exemplary political system with a corresponding society that had internalised the lessons of National Socialism. The prevailing narrative of the early Berlin Republic was that Germany had taken a "special path" towards dictatorship and genocide in the 19th and early 20th centuries. With reunification in 1990, however, the country had finally left this path and had fully arrived in the West. To resolve the footnote[6] According to this interpretation, the Berlin Republic was a new player in international politics, working side by side with its partners in Europe and the world to secure peace and stability at home and abroad.

However, the varying frequency with which Hitler, Auschwitz and National Socialism are referred to in books in Germany and abroad shows that Germany did not abandon its special path in 1990, but rather embarked on a new one. Germany's actual special path is that of its second (post-war) republic, which was founded in 1990 and, if one follows the argumentation of journalist and historian Nils Minkmar, collapsed in the wake of Putin's war of aggression against Ukraine. Germany's second republic, writes Minkmar, "took a holiday from history, was finally able to enjoy the moment like Faust and, also like Faust, made a pact - with Putin and with bad consequences". To resolve the footnote[7] However, Germany's holiday from history came to an abrupt end with the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022. In the words of Federal Chancellor Olaf Scholz: "24 February 2022 marks a turning point in the history of our continent." To resolve the footnote[8] Scholz is right when he speaks of a turning point, but it does not primarily concern "our continent", but first and foremost his own country. The Russian invasion of Ukraine made many Germans suddenly aware of the realities of international politics that had been present to Germany's neighbours for some time.

The Faustian pact was not born of malice - Germany's second republic had been founded and governed with the best of intentions. Rather, a certain short-sightedness had prevailed that prevented many Germans from seeing what many of their international partners had long recognised after Russia's previous invasions or the shooting down of MH17 - the Malaysia Airlines plane that was shot down by a Russian missile in Ukrainian airspace on its way from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur in July 2014. And this short-sightedness is closely linked to the normative conclusions that the protagonists of the Second German Republic had drawn from the country's experience with National Socialism, which differed quite drastically from those drawn by other countries.

As a result, many Germans relied on soft power and had little interest in hard power - without realising that the former is just hot air if it is not accompanied by the latter. At the same time, many failed to recognise that Putin's aggressive approach since the day he took office was in line with earlier phases of Russian history. This is also reflected in a sharp decline in references in German-language publications to terms associated with the dark side of Russia's past, such as "Gulag", "Stalin", "Prague Spring" or "popular uprising". Dissolving the footnote[9] In English-language books, the number of mentions of the terms "Stalin" and "Prague Spring" remained relatively constant between 1995 and 2018, while mentions of the "Gulag" actually increased significantly. Resolution of the footnote[10]

The illusions that were harboured in Germany ultimately stood in the way of both even more successful European integration and the creation of an even more durable security and peace architecture. Minkmar therefore believes that a third republic must emerge from the ruins of the second: one that takes a less short-sighted view of the world around it and leaves behind the "naivety" of thinking about the world. To resolve the footnote[11] It is therefore necessary to work out lessons from the "Third Reich" for the third republic.

Historical misunderstandings

However, the myopic view of the past is not limited to Germany. In fact, many of the lessons learnt worldwide from 1933 for crisis management in the 2020s are based on historical misunderstandings. For example, although there are countless books about the "Third Reich" and its horrors, in many cases, and without realising it, they reproduce clichés dating back to Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, or they portray Hitler and the National Socialists only as madmen driven by hatred, racism and anti-Semitism. However, such approaches will never understand why so many supporters of National Socialism saw themselves as idealists. And they will not be able to explain why, according to Hitler, reason, not emotion, should determine the actions of National Socialism. On the resolution of the footnote[12]

A reductionist approach to the question of what characterised Hitler and other National Socialists is dangerous. It tempts us to look for false warning signs in today's world and to search for Hitler revenants and National Socialists in the wrong places. We are therefore recommended to read Thomas Mann's essay "Brother Hitler" from 1938, in which he portrays the dictator as a product of the same traditions in which he himself had grown up. In doing so, he opens our eyes to the realisation that it is not the angry crybabies, but above all people "like us" who are open to dismantling democracy in times of crisis. In fact, as soon as we take the ideas of the National Socialists seriously, it becomes disturbingly clear that many people supported these policies in the period from the 1920s to the 1940s for almost the same reasons that we so vehemently reject National Socialism today - not least the conviction that political legitimacy should come from the people and that equality is an ideal worth fighting for.

It is therefore important to dispel various misconceptions about the death of democracy in 1933 that are still taught in German schools today, including the idea that the seeds of Weimar's self-destruction were sown as early as 1919, that the "unstable Weimar constitution (.... ) ultimately led to the self-dissolution of the first German democracy", that "coalitions capable of governing [became] impossible because there were too many splinter parties", On the dissolution of the footnote[13] that the rise of Hitler resulted from the strength of the German conservatives, that the world economic crisis played the decisive role in the death of German democracy, that Germans supported the National Socialists, because they longed for the return of the authoritarian state of the past and rejected democracy in any form, or that the actions of the National Socialists did little to bring Hitler to power - which is evident, for example, in the tendency to speak only of a "transfer of power" in relation to the events of 1933 and not of a process that was both a "transfer of power" and a "seizure of power". On the resolution of the footnote[14]

The beliefs of the National Socialists and the appeal of their ideas cannot be understood if we do not take seriously the central apparent contradictions at the core of National Socialism, namely that the National Socialists destroyed democracy and socialism in the name of overcoming an all-encompassing, existential mega-crisis and creating a supposedly better and truer democracy and socialism. The National Socialists preached that all power must come from the people, not out of insincere and opportunistic Machiavellianism, but because they believed it. The promise of a National Socialist illiberal "people's community democracy" as a collectivist and marginalising concept of self-determination was widely accepted and promised to overcome what was supposedly the greatest crisis in centuries. This made 1933 possible and ultimately brought the world to the gates of hell.

So if we understand National Socialism as a manifestation of illiberal democracy, we see that today's variants of illiberal democracy could very easily slide into something much worse in times of crisis than we are currently experiencing in many places around the world. If we refrain from a reductionist account of National Socialism, we will recognise that the parallels between the present and the past lie primarily in the dangers posed by illiberal democracy and the general perception of crisis.

Furthermore, if we understand National Socialism as a political religion, we can understand why Germans followed its siren song en masse. Hitler's political religion demanded a double commitment from converts: firstly, to National Socialist orthodoxy - adherence to 'correct' beliefs and the practice of rituals - and secondly, to National Socialist orthopraxy - the 'ethical' behaviour prescribed by orthodoxy. In this way, acts of violence and war against internal and external "enemies of the people" were given a moral and even heroic significance - because they supposedly served a "higher" purpose, the good of one's own "national community". The belief systems of National Socialism are therefore inextricably linked to the violence and horrors of the "Third Reich". In other words, while it may well be true that liberal democracy brings with it a "peace dividend", illiberal democracy - at least in its totalitarian, messianic incarnations - can easily generate a "genocide and war dividend" if people believe they can overcome an existential crisis in this way.

Just as the National Socialist mindset should be taken seriously as a key driver of violent and extreme behaviour, the National Socialists themselves should also be understood as political actors with a clear plan for the future. Although it often looked as if they were merely reacting to others, it was precisely this reactive character of National Socialist behaviour that was a tactic - and a very successful one at that - that explains not only the developments in 1933, but also the dynamics of twelve years of Nazi rule. The path from the seizure of power to the settlement policy in the East, to total war and to a war policy of extermination and genocide was by no means long and tortuous - in the self-perception of its actors, it was the path to overcoming an existential polycrisis.

What does 1933 teach us?

The way in which the National Socialists succeeded in seizing and consolidating power and ultimately pursuing radical policies has more in common with the cunning of Frank Underwood, the fictional US president from the Netflix series "House of Cards", than with many of the portrayals that question whether their rise was coolly calculated. The political style and the illusion game of the National Socialists, the undermining and destruction of norms and institutions as well as the pursuit of a hidden agenda are increasingly becoming characteristics of politics in our time as well. Understanding the year 1933 should therefore help us to better understand today's challenges.

We therefore need a defensive democracy with strong guard rails in order to be able to counter the perception of an existential polycrisis. This includes strong party-political organisations that - unlike in daydreams of the transformation of parties into "movements" - prevent the internal takeover by radicals. Crucially, strong party structures also provide a toolkit to deal with polarised societies by both representing and containing divisions. The behaviour of conservative parties is particularly important here. German conservatism played a central role in the fall of Weimar democracy, but in a counter-intuitive way, not through its strength but through its weakness and the fragmentation of its organisations.

However, guard rails offer little or no protection if they are poorly positioned. Thus, a look beyond Germany reveals that in trying to make our own democracy weatherproof and crisis-resistant, we may have more to learn from cases where democracy survived in 1933 than from the death of democracy in Germany. The Netherlands, for example, had established a resilient political structure, or a defencible democracy avant la lettre, capable of dealing with a wide range of shocks to its system and responding flexibly to crises. As a result, the Dutch did not need to anticipate the specific threats of 1933, as their crisis prevention and response capacities were large enough to avoid the establishment of a domestic dictatorship. The comparison also shows that some supposed guard rails of today's democracy in Germany - such as the five per cent hurdle in elections - are largely useless and only appear to offer security.

The problem of looking at specific cases of the collapse of democracy, including the German case in 1933, harbours a danger: that the most important variables are insufficiently recognised and too narrow conclusions are drawn. The exact historical context of the collapse of a political order will always vary, as will the perception of an existential polycrisis and its political consequences. It therefore makes sense to identify states and societies from the past that were resilient to the widest possible range of shocks. Or as historian Niall Ferguson puts it: "All we can learn from history is how to build social and political structures that are at least resilient and at best antifragile (...), and how to resist the siren voices that propose totalitarian rule or world government as necessary for the protection of our unfortunate species and our vulnerable world." To resolve the footnote[15]

Nevertheless, the fall of the Weimar Republic in 1933 is a warning of where uncontained perceptions of crisis can lead. After all, it was Hitler's polycrisis consciousness and the associated individual and collective existential fear that formed the core of the emergence of Hitler's political and genocidal anti-Semitism. Added to this was the identification of the Jews with this crisis and the implementation of this identification in a programme of total solutions in order to "protect" themselves permanently. To resolve the footnote[16]

Perhaps the most important warning that the past century holds for us is that the biggest and most terrible crises in the world only arise when we try to contain real or perceived crises headlessly and without moderation. To resolve the footnote[17]

This article is a revised extract from Thomas Weber (ed.), Als die Demokratie starb. Die Machtergreifung der Nationalsozialisten - Geschichte und Gegenwart, Freiburg/Br. 2022.

Footnotes

On the mention of the footnote [1]

Roger Cohen, Trump's Weimar America, 14 Dec 2015, External link:http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/15/opinion/weimar-america.html.

For the mention of the footnote [2]

Niall Ferguson, "Weimar America"? The Trump Show Is No Cabaret, 6 Sept. 2020, External link:http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/weimar-america-the-trump-show-is-no-cabaret/2020/09/06/adbb62ca-f041-11ea-8025-5d3489768ac8_story.html.

On the mention of the footnote [3]

Cf. Thomas Weber, Trump Is Not a Fascist. But That Didn't Make Him Any Less Dangerous to Our Democracy, 24.1.2021, external link:https://edition.cnn.com/2021/01/24/opinions/trump-fascism-misguided-comparison-weber/index.html.

On the mention of the footnote [4]

Cf. Google N-gram analyses for "Hitler" and "Auschwitz" in English and Spanish, created on 10 August 2022: External link:https://t1p.de/ngramspanish and External link:https://t1p.de/ngramenglish.

For the mention of the footnote [5]

Cf. Google N-gram analyses for "Hitler", "Auschwitz" and "National Socialism" in German, created on 10 January 2022: External link:https://t1p.de/ngramgerman.

On the mention of the footnote [6]

Cf. Heidi Tworek/Thomas Weber, Das Märchen vom Schicksalstag, 8 November 2014, External link:http://www.faz.net/13253194.html.

On the mention of the footnote [7]

Nils Minkmar, Long live the Third Republic, 10 May 2022, External link:http://www.sueddeutsche.de/projekte/artikel/kultur/e195647.

Mention of the footnote [8]

Government statement by Federal Chancellor Olaf Scholz, 27 February 2022, External link:http://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/suche/regierungserklaerung-von-bundeskanzler-olaf-scholz-am-27-februar-2022-2008356.

Mention of the footnote [9]

Cf. Google N-gram analyses for "Stalin", "Gulag", "Prager Frühling" and "Volksaufstand" in German, created on 10 August 2022: External link:https://t1p.de/ngramstalingerman and External link:https://t1p.de/ngramgulagpfvgerman.

For the mention of the footnote [10]

Cf. Google N-gram analyses for "Stalin", "Gulag" and "Prague Spring" in English, created on 10 August 2022: External link:https://t1p.de/ngramstalinenglish and External link:https://t1p.de/ngramgulagpsenglish.

On the mention of the footnote [11]

See Minkmar (note 7).

On the mention of the footnote [12]

In his first known written anti-Semitic statement - the so-called Gemlich letter of 1919 - Hitler rejected "anti-Semitism on purely emotional grounds" and advocated an "anti-Semitism of reason". Cf. Hitler to Adolf Gemlich, 16 September 1919, reproduced in: German Historical Institute Washington DC, German History in Documents and Images, n.d., external link:https://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/pdf/deu/NAZI_HITLER_ANTISEMITISM1_DEU.pdf.

On the mention of the footnote [13]

Cf. Fabio Schwabe, Gründe für das Scheitern der Weimarer Republik, 12 March 2021, external link:http://www.geschichte-abitur.de/weimarer-republik/gruende-fuer-das-scheitern.

On the mention of the footnote [14]

Cf. Hans-Jürgen Lendzian (ed.), Zeiten und Menschen. Geschichte, Qualifikationsphase Oberstufe Nordrhein-Westfalen, Braunschweig 2019, pp. 237-264; Ulrich Baumgärtner et al. (eds.), Horizonte. Geschichte Qualifikationsphase, Sekundarstufe II Nordrhein-Westfalen, Braunschweig 2015, pp. 242-270.

On the mention of the footnote [15]

Niall Ferguson, Doom. The Politics of Catastrophe, London 2022, p. 17, own translation.

On the mention of the footnote [16]

Cf. Thomas Weber, Germany in Crisis. Hitler's Antisemitism as a Function of Existential Anxiety and a Quest for Sustainable Security, in: Antisemitism Studies (n.d.).

On the mention of the footnote [17]

Cf. Beatrice de Graaf, Crisis!, Amsterdam 2022.

#Creative Commons Licence#CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 DE#Thomas Weber#bpb.de#Germany 1933#weimar#weimar America#stop violence#stop trump#save our democracy#vote democrat#vote blue#please vote#Weimerica#Roger Cohen#read more

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daniela Klette lived quietly. She walked her dog and gave maths tuition to her neighbours’ children.

But when she was arrested in late February, the police found tens of thousands of euros in cash in her Berlin flat and five weapons, among them a Kalashnikov assault rifle and a replica rocket launcher.

Klette, 65, had been on the run for more than 30 years. She was wanted for crimes connected to the left-wing militant Red Army Faction (RAF), which was active in Germany from the 1970s to the 1990s.

Known in its early days as the Baader Meinhof group, the gang pursued their political aims through the kidnap or murder of senior members of the business and industrial communities.

The RAF’s notoriety had led to a podcast team in Berlin trying to track Klette down using a facial recognition tool.

The podcast ran shortly before Christmas, only weeks before the arrest. But police deny a connection. They say they had a tip-off from a member of the public.

The RAF’s crimes are not forgotten in Germany, even if a generation has passed since they were committed.

They continue to exercise the imaginations of film and television producers, who have been making high-budget drama and documentary series that recall the assassinations of the 1980s and 90s.

“The RAF is deeply rooted in the collective memory, at least in western Germany,” says Petra Terhoeven, an expert in the history of political violence at Göttingen University.

Later this year, for example, German television will run a new four-part drama about Alfred Herrhausen, the head of Deutsche Bank, who was murdered shortly after the opening of the Berlin Wall in 1989. A sophisticated roadside bomb destroyed his armoured Mercedes as he was being driven to work.

In 2020 the first Netflix original series for the German market, A Perfect Crime, examined the assassination of Detlev Rohwedder. He was the head of the Treuhandanstalt, the organisation established after German reunification to privatise all state-owned industry in the former East Germany.

Rohwedder was killed by a shot from a sniper’s rifle through an upstairs window at his home in Düsseldorf in the spring of 1991.

In neither case have the perpetrators been caught.

The Netflix series was made by the Beetz Brothers production company. Recalling its origins, co-director Georg Tschurtschenthaler says the brief was to find a project that the whole country would talk about. “It had to be big and relevant,” he says. “It had to create some noise.”

A Perfect Crime, while acknowledging the letter found at the crime scene in which the RAF claimed responsibility for Rohwedder’s murder, presents a number of different scenarios as to who may have killed him. For Tschurtschenthaler the background to the murder is what matters – the rapid closure of much of East German industry and the loss of millions of jobs.

“It’s a dark period that resonates until today,” he says.

Petra Terhoeven, the historian, warns of the dangers of a trivialisation of the crimes committed by the RAF. She detects too great a focus on the perpetrators, too little consideration for the victims.

The victim who has received perhaps most attention is Alfred Herrhausen, a charismatic and influential banker and a personal friend of then-Chancellor Helmut Kohl. A new documentary will accompany the four-part television drama later this year. Herrhausen has also been portrayed in fiction, by the writer Tanja Langer.

“When I was writing my novel it was important for me to create an homage to this person,” she says of her book. The novel, an account of a relationship between a young woman and an older man, a banker, is written from personal experience. Langer and Herrhausen had a close friendship for several years until his death.

Even though the RAF claimed responsibility for Herrhausen’s murder, Tanja Langer thinks the truth may not be as simple. She did several years’ research for her novel and spent a lot of time in the archive of the former East German secret police, the Stasi.

“In the end my conclusion was that even if the RAF carried out the murder, maybe there were others that were also part of it,” she says.

It’s that uncertainty, in part, that fuels the continued interest. There are still many unsolved murders from the 1980s and it’s possible that Daniela Klette, now behind bars, knows something about them.

Not long before she was arrested, a podcast company in Berlin, Undone, set out to find her. They had been contacted by a listener who said he’d been at a party where a woman had claimed to be Klette.

“It was a crazy story,” says Patrick Stegemann, who worked on the series.

Undone brought in an AI expert who deployed facial recognition software to search the internet for pictures that matched one of Klette on an old “Wanted” poster. It came up with a match for a woman living as “Claudia” not far from where the podcasters operate out of an old industrial premises in Berlin. But when they went to look for her, she was nowhere to be found.

Two months later, when Daniela Klette, was arrested, it became clear that they had identified the right woman. Patrick Stegemann remembers hearing the news of the arrest. “It was a wild mixture of feelings,” he says.

Prosecutors are currently going through dozens of boxes of evidence and are yet to bring charges against Klette.

Petra Terhoeven is sceptical she will offer any help.

“The majority of former members of the RAF don't speak about the past,” she says. “It’s like a political sect, it’s a kind of cartel of silence. And so probably she will remain silent.”

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

2024 / 45

Aperçu of the week

"Latinos are Republican. They just don't know it yet."

(Ronald Reagan, actor and US-American politician of the Republican Party who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989)

Bad News of the Week

What has the self-luminous circulation guidance system not been used for: traffic lights. Because of them, we associate green with go and red with stop (and yellow with attention). Parties are also often associated with colors. So it's no wonder that the coalition of Social Democrats (red), Liberals (yellow) and Greens (guess what!) was also called "traffic lights coalition". "Was" because the traffic light has been history since last week. This is because the red Chancellor Olaf Scholz kicked the yellow Finance Minister Christian Lindner out of the cabinet. Whereupon the Liberals (naturally) left the coalition.

Since then, the term "Broken traffic light" has been used. Which sounds just as uncharming as a traffic accident. The traffic lights had been crunching for some time. This coalition was never a love match. Many political observers saw the end coming, there was talk of an "autumn of decisions". It should be noted that Olaf Scholz's last political job was finance minister (under the conservative Chancellor Angela Merkel). And both the very former and the recently former finance ministers have always agreed on one thing: that they think they are by far the smartest in the room. No wonder that the final stumbling block was a financial one, namely the budget.

"The government is finished and will no longer govern. That sounds insultingly banal, but because the last time a coalition broke up was 42 years ago and the last time the legislature was shortened was 20 years ago, it's a big deal when it happens," writes the news magazine Der Spiegel. This is why a cold, paralyzing fog has descended over the country just in time for the appropriate season - there is a standstill. The early elections are scheduled for February 23, 2025. Until then, the legislative apparatus will be largely dormant, as there seems to be no will to cooperate across party lines. And any new government must first find itself (it will be a coalition again) will first need time to define a program and put it into legislation.

Germany currently has no budget plan for 2025. In the USA, such a status would probably lead to a complete government shutdown. Fortunately, it cannot get that far in this country. Nevertheless, there will be virtually no government action. For minimum half a year. In the world's third-largest economy. At a time when we are sliding into recession. If someone had asked me the week before last to draw up a horror scenario for the near future, this is pretty much what I would have come up with. Not good.

Good News of the Week

The Berlin Wall came down 35 years ago. Euphoria is certainly not a typical trait that can be attributed to Germans. And yet it was the predominant feeling that we otherwise only know from winning a soccer championship. In Berlin, strangers hugged each other, cheered and sang together. After the first tentative rapprochement - the escape of around 4,000 GDR citizens via the West German embassy in Prague - this marked the beginning of what had seemed impossible shortly before: the end of the Cold War.

The so-called fall of the Berlin Wall was the starting signal for German reunification, the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Or to put it another way: the West finally triumphed over the East. Which was, of course, presumptuous and arrogant at the time and proved to be a fatal historical blunder. After all, there would be no Vladimir Putin today, tearing apart a former brother nation, or a Viktor Orbán, who created the guide "How to create an autocracy in a democracy", if "the West" had not only opened the door to the Eastern Europeans, but also extended a hand.

Nevertheless, the day the Wall fell is and was a day of joy. The Wall did not actually fall on that day. Rather, thousands of East Berliners spontaneously set off to visit the West when Günter Schabowski, Secretary for Information, more or less coincidentally announced in a televised press conference that lighter travel restrictions would apply "immediately, without delay". And the officers on guard duty in the completely uninformed border troops had the sense not to shoot at the masses of people coming towards them, but simply to hold back. In the weeks-long party that followed, the Wall actually fell piece by piece - by diggers as well as souvenir hunters with hammers and chisels.

And even if the achievements of this liberation at the beginning of the 1990s are questioned by one or two politicians and not recognized or even forgotten by one or two voters, this does not change the basic principle: it was a liberation. You can give it up again of your own free will. But at least you held it in your hand once. After all, a real democracy can only abolish itself.

Personal happy moment of the week

Breaking News: I broke a rib. I won't tell you how, just this much: it wasn't anything heroic like "You should see the other guy!". Fortunately, the broken rib stayed in place and didn't damage my lungs or any other organ. Now I'll only be in pain for a good four weeks (I can't stop breathing obviously) and I won't sleep well because I'm bound to move the wrong way unconsciously. But still: that qualifies for a lucky moment. Not a happy one, okay...

I couldn't care less...

...that many criticize the credibility of an environmental summit in a fossil fuel exporting country. The main thing is that COP29 takes place. Because the EU climate change service Copernicus has just issued a forecast: 2024 is likely to be the first year since records began in which the average temperature will be more than 1.5 degrees warmer than the pre-industrial average. This is the defined maximum level of global warming in order to still have a chance of avoiding radical tipping points in the global climate. If there are (or should be, let's be realistic) tangible successes, someone who actually contributes too little to this can proudly announce them in the Azerbaijani capital Baku: autocrat Ilham Heydar oglu Aliyev.

It's fine with me...

...that the Self-Determination Act is now officially in force in Germany. This means that fellow human beings who were born in the wrong body finally have exactly that: the right to self-determination. Without shameful questioning, expensive expert opinions and lengthy bureaucracy. In this case, thanks to Justice Minister Marco Buschmann, who is no longer in office as a Liberal minister (see "Broken traffic light").

Post Scriptum

Okay, I held out ignoring the elephant in the room until the last column. But now it has to come out: a majority of the US electorate has decided to give Donald Trump a second term. Despite, or perhaps because of, the fact that he didn't mince his words. Because they knew exactly which personality with which values would get the keys to the White House. You don't even have to read the Heritage Foundation's "Project 2025" to find out, just listen to Trump himself. As tech billionnaire Peter Thiel famously put it eight years ago: You have to take Trump seriously but not literally.

This was almost a landslide victory: Trump not only took the majority of electoral votes by a large margin, but also won the popular vote. The Republicans have already won the majority in the Senate and a majority in the House of Representatives is practically guaranteed. With the Supreme Court already in their pocket, this is an unprecedented concentration of power. The dust has not yet settled. And I still don't know exactly how to categorize some aspects of it. So here is a loose collection of my thoughts and those of others.

"Of course I had suspected it, not only feared it, but deep down even knew that it would happen again. But you can still hope, against all odds. What else can you do? We had no choice. We are just spectators." Stefan Kuzmany in Der Spiegel.

The first personnel decisions about Trump's possible cabinet are making the rounds, with only Mike Pompeo and Nikki Haley being ruled out so far. Conspiracy theorist and avowed anti-vaccinationist Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is to take charge of health. And Elon Musk is to become head of a still not existing economic commission. And announces that he could easily cut the entire state budget by 2 trillion - that's almost a third. As head of a Department of Government Efficiency he promises no less than "fixing the government". Perhaps most glaring, however, is the choice of Fox News host Pete Hegseth as Secretary of Defense - who has no administrative, political or national security experience. But seemes to be a sexist asshole.

Election winner Trump is the first US president to enter the White House as a convicted felon. The sentence was due to be announced at the end of November. What will become of it - and of the other criminal proceedings against him? Nothing, of course. He can simply order the termination of some proceedings by having the Department of Justice fire the responsible special investigator. And others will simply be suspended until the President is no longer sitting. Doesn't that sound more like a Banana Republic?

"The racist, agitator and misogynist Donald Trump returns to the White House. A disaster - to which we in Germany are not immune. (...) You are probably just as stunned as I am: Donald Trump becomes US president again. A fascist. A liar and demagogue. And one who announces in no uncertain terms what he intends to do: rebuild and destroy the oldest democracy much more extensively and systematically than in his unprepared first term." Christoph Bautz, Chairman of the democratic activist association Campact.

"It should come as no great surprise that a Democratic Party which has abandoned working class people would find that the working class has abandoned them. While the Democratic leadership defends the status quo, the American people are angry and want change. And they're right." Bernie Sanders (who is officially an independent senator) on Twitter (I still refuse to call it X).

#thoughts#aperçu#good news#bad news#news of the week#happy moments#politics#ronald reagan#latino#traffic light#olaf scholz#coalition#germany#berlin wall#cold war#breaking news#cop29#self determination#donald trump#elections#democracy#landslide#der spiegel#white house#majority#east west#republicans#personal#usa#liberation

1 note

·

View note

Text

Shifts in Germany and elsewhere in Europe

COGwriter

A shift is happening in Europe.

Many there are concerned about Islam and migrants.

Germany’s Alternative für Deutshland (AfD) party continues to increase in popularity and looks to soon have more political clout:

Germany far-right party could win first state in eastern regional elections

September 1, 2024

BERLIN, Sept 1 (Reuters) – Germans were voting in two eastern states on Sunday, with the far-right AfD on track to win a state election for the first time and Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s coalition set to receive a drubbing just a year before federal elections.

The Alternative for Germany (AfD) is polling first on 30% in Thuringia and is neck-and-neck with the conservatives in Saxony on 30-32%. A win would mark the first time a far-right party has the most seats in a German state parliament since World War Two.

The 11-year-old party would be unlikely to be able to form a state government even if it does win, as it is polling short of a majority and other parties refuse to collaborate with it.

But a strong showing for the AfD and another populist party, the newly-created Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW), named after its founder, a former communist, would complicate coalition building. …

Both the AfD and BSW are anti-migration, eurosceptic, Russia-friendly and are particularly strong in the former Communist-run East, where concerns about a cost of living crisis, the Ukraine war and immigration run deep.

A deadly stabbing spree linked to Islamic State 10 days ago in the western German city of Solingen stoked concerns about immigration in particular and criticism of the government’s handling of the issue.

“Our freedoms are being increasingly restricted because people are being allowed into the country who don’t fit in,” the AfD’s leader in Thuringia, Bjoern Hoecke, told a campaign event in Nordhausen …

‘POLITICAL EARTHQUAKE’

All three parties in Scholz’s federal coalition are seen losing votes on Sunday, with the Greens and liberal Free Democrats likely to struggle to reach the 5% threshold to enter parliament.

Discontent with the federal government stems partly from the fact it is an ideologically heterogeneous coalition plagued by infighting. A rout in the East will only exacerbate those tensions, analysts say.

“The state elections… have the potential to trigger an earthquake in Berlin,” Wagenknecht told a campaign rally in Erfurt, the capital of Thuringia,…

The AfD and BSW together are expected to take some 40-50% of the vote in the two states compared with 23-27.5% at a national level, laying bare the continuing divide between East and West more than 30 years after reunification. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/far-right-could-win-first-state-two-east-german-elections-2024-09-01/

The AfD is considered Germany’s anti-migrant party. Its influence has been growing as more in Germany have been supporting it in elections. The fact that the Islamic State took credit for the stabbing (see Suspected Islamic terrorism hitting France and Germany–‘Islamic State’ claims involvement) reinforces the AfD view that migrants from the Middle East and Africa are a danger.

And yes, it wants many migrants–particularly Islamic ones–to leave Germany.

But Germany is not the only nation in Europe shifting on migrants.

A reader tipped me off to the following today related to Sweden:

The Swedish government is considering offering foreigners who become naturalized citizens money to leave the country. The current “voluntary remigration“ scheme offers 10,000 Swedish kroner ($960) per adult and 5,000 kroner ($480) per child, as well as travel costs for refugees and migrants to leave Sweden.

Stockholm is considering widening the program under which migrants struggling to integrate into Swedish society are encouraged to leave, including naturalized Swedes and migrant families, according to a proposal submitted to Swedish Immigration Minister Maria Malmer Stenergard on Aug. 13.

A report based on an inquiry recommended widening the proposal but rejected increasing the grant in case it sends a signal to immigrants that “they are not welcome in Sweden.” Ministers in Stockholm had sought advice on how emigration could be “greatly stimulated.” https://prescottenews.com/2024/08/19/sweden-considers-offering-naturalized-citizens-money-to-return-to-countries-of-origin-the-epoch-times/

The AfD has suggested an involuntary program to move migrants out of Germany.

Notice also the following related to Sweden:

Europe’s lefties bash migrants (nearly) as well as the hard right

As Europe faced a sharp rise in the arrival of migrants seeking asylum in 2015, many national governments demanded more be done to stem the flow. Sweden’s prime minister disagreed. “My Europe does not build walls,” Stefan Lofven, leader of the Social Democrats, thundered in response, exuding the high-mindedness left-wingers muster at will. A couple of electoral setbacks later—it turns out voters are rather keen on walls during migration crises—the party is speaking from a different register, this time as an opposition force. “The Swedish people can feel safe in the knowledge that Social Democrats will stand up for a strict migration policy,” Magdalena Andersson, its current leader, said in an interview to a local paper … https://www.economist.com/europe/2024/08/29/europes-lefties-bash-migrants-nearly-as-well-as-the-hard-right

When my wife and I visited Sweden several years ago, we found that Swedes were getting concerned about the migrant matters there. Now, some steps to remove and restrict them have begun.

Pope Francis decried anti-migrant moves last week, yet made his own last Fall (see Pope Francis’ hypocrisy on migrants and wealth).

The Bible also shows that religion will be used by the coming European King of the North:

36 “Then the king shall do according to his own will: he shall exalt and magnify himself above every god, shall speak blasphemies against the God of gods, and shall prosper till the wrath has been accomplished; for what has been determined shall be done. 37 He shall regard neither the God of his fathers nor the desire of women, nor regard any god; for he shall exalt himself above them all. 38 But in their place he shall honor a god of fortresses; and a god which his fathers did not know he shall honor with gold and silver, with precious stones and pleasant things. 39 Thus he shall act against the strongest fortresses with a foreign god, which he shall acknowledge, and advance its glory; and he shall cause them to rule over many, and divide the land for gain. (Daniel 11:36-39)

The King of the North Beast will also push out Islam (cf. Daniel 11:40-43) and lead a powerful European military (cf. Revelation 13:3-4; Daniel 11:39-43). These are things that many in Europe want!

While the AfD has its own problems, its rise is demonstrating that Germans are becoming less tolerant of migrants than many thought.

A while back, we put out the following video:

youtube

14:22

AfD: Prelude to a Hitler Beast?

Germany’s Alternative für Deutshland (Alternative for Germany in English) party celebrated its 10th anniversary on February 6, 2023.

It objects to: ❌More illegal migration ❌More asylum abuse ❌More crime ❌More housing shortage ❌More Cancel Culture

The AfD also asserts, “Now it’s time to change that. And that’s only possible with us.” Many are concerned that the AfD’s growing political influence will impact Germany. Can a strong man worse than Adolf Hitler, that the Bible calls the Beast rise up from Germany? Could Europe reorganize with a small backing to put this leader into place? Does the AfD want to make a deal with Russia? Will Germany make a future deal with Russia that would be opposed to the USA? Does the AfD want religion involved to meet its objectives in such a way that it could support the coming King of the North Beast power that the Bible warns will arise in Europe? Could Europe unite under such a leader according to scripture? Steve Dupuie and Dr. Thiel go over these matters.

Here is a link to our video:��AfD: Prelude to a Hitler Beast?

Ireland has has migrant concerns (see ZH: ‘Irish People Are Being Attacked’ – Anti-Immigrant Riots Erupt After Dublin Stabbing Spree). As has Italy (e.g. Fox: Italy’s call for naval blockade may be only way to stem Europe’s migrant crisis, expert says) and France (e.g. Macron warns against ‘extremes,’ while Le Pen vows to deport Islamic extremists from France).

Related to Italy, notice also the following:

Italy’s Meloni Scores a Victory on Illegal Immigration as the Rest of Europe Is Reeling

The lack of a crisis is largely due to a can-do prime minister who campaigned on getting migration under control.

August 28, 2024

Impounding of MSF’s ship for 60 days is 23rd seizure of a vessel by Giorgia Meloni’s government … illegal arrivals have fallen by 65% https://www.nysun.com/article/italys-meloni-scores-a-victory-on-illegal-immigration-as-the-rest-of-europe-is-reeling

Italy steps up clampdown on boats rescuing migrants in Mediterranean Sea

August 28, 2024

Giorgia Meloni’s government has impounded a humanitarian rescue ship for the 23rd time, as Italy steps up its clampdown on irregular migration across the Mediterranean.

Just over 39,500 irregular migrants have arrived in Italy by sea this year, compared with 112,500 in the same period last year, and 53,400 in 2022, according to Italy’s interior ministry. “Italy continues to reap the fruits of the work of the Meloni government on the front of the fight against wild clandestine immigration,” Tommaso Foti, head of the Brothers of Italy’s parliamentary delegation, said this month. https://www.ft.com/content/ada8343c-3783-4600-9726-9aba86f3e38a

We are seeing a shift happening in Europe related to migrants and other matters.

However, it will end up being too little too late as far as democracy goes.

Despite elections, the Bible shows that Europe will reorganize and power will be granted to a dictator:

12 “The ten horns which you saw are ten kings who have received no kingdom as yet, but they receive authority for one hour as kings with the beast. 13 These are of one mind, and they will give their power and authority to the beast. (Revelation 17:12-13, NKJV throughout unless otherwise specified)

These ten kings have no kingdom, but are to attain one. Thus, this is a type of reorganization in verse 12–and basically a type of major or great reset (see also Is a Great Reset Coming?). Since they give their power to the Beast in verse 13, this is a second reorganization–and that Beast will be a dictator. The Beast is the one who was the prince of Daniel 9:26 (see also The ‘Peace Deal’ of Daniel 9:27). He is also the seventh king of Revelation 17:10, and becomes so with the fulfillment of Revelation 17:13. As far as the identity of the sixth king of Revelation 17:10, check out the article: The European Union and the Seven Kings of Revelation 17.

Migrant matters will be a factor in his rise.

He will also be the one who will lead the attack against the USA and its British-descended allies in what could be called WWIII.

The time for that is getting closer.

Related Items:

Europa, the Beast, and Revelation Where did Europe get its name? What might Europe have to do with the Book of Revelation? What about “the Beast”? Is an emerging European power “the daughter of Babylon”? What is ahead for Europe? Here is are links to related videos: European history and the Bible, Europe In Prophecy, The End of European Babylon, and Can You Prove that the Beast to Come is European? Here is a link to a related sermon in the Spanish language: El Fin de la Babilonia Europea.

The European Union and the Seven Kings of Revelation 17 Could the European Union be the sixth king that now is, but is not? Here is a link to the related sermon video: European Union & 7 Kings of Revelation 17:10. Must the Ten Kings of Revelation 17:12 Rule over Ten Currently Existing Nations? Some claim that these passages refer to a gathering of 10 currently existing nations together, while one group teaches that this is referring to 11 nations getting together. Is that what Revelation 17:12-13 refers to? The ramifications of misunderstanding this are enormous. Here is a link to a related sermon in the Spanish language: ¿Deben los Diez Reyes gobernar sobre diez naciones? A related sermon in the English language is titled: Ten Kings of Revelation and the Great Tribulation.

Germany in Biblical Prophecy Does Assyria in the Bible equate to an end time power inhabiting the area of the old Roman Empire? What does prophecy say Germany will do and what does it say will happen to most of the German people? Here are links to two sermon videos Germany in Bible Prophecy and The Rise of the Germanic Beast Power of Prophecy.

War is Coming Between Europeans and Arabs Is war really coming between the Arabs and the Europeans? What does Bible prophecy say about that? Do the Central Europeans (Assyria in prophecy) make a deal with the Arabs that will hurt the USA and its Anglo-Saxon allies? Do Catholic or Islamic prophecies discuss a war between Europe and Islam? If so, what is the sequence of events that the Bible reveals? Who does the Bible, Catholic, and Islamic prophecy teach will win such a war? This is a video.

Will Islam be Pushed Out of Europe? On June 8, 2018, Austria’s Chancellor Sebastian Kurz announced the closing of seven Islamic mosques in an effort to reduce “political Islam.” In the past several years, at least 6 European nations have banned the wearing of a commonly used garment by Islamic females. Heinz-Christian Strache (later Vice Chancellor of Austria) has declared that Islam has no place in Europe. Did Germany’s Angela Merkel call multiculturalism a failure? Will there be deals between the Muslims and the Europeans? Will a European Beast leader rise up after a reorganization that will eliminate nationalism? Will Europe push out Islam? What does Catholic prophecy teach? What does the Bible teach in Daniel and Revelation? Is Islam prophesied to be pushed out of Europe? Dr. Thiel addresses these issues and more in this video.

Can the Final Antichrist be Islamic? Is Joel Richardson correct that the final Antichrist will be Islamic and not European? Find out. A related sermon is titled: Is the Final Antichrist Islamic or European? Another video is Mystery Babylon USA, Mecca, or Rome?

World War III: Steps in Progress Are there surprising actions going on now that are leading to WWIII? Might a nuclear attack be expected? Does the Bible promise protection to all or only some Christians? How can you be part of those that will be protected? A related video would be Is World War III About to Begin? Can You Escape?

Might German Baron Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg become the King of the North? Is the former German Defense Minister (who is also the former German Minister for Economics and Technology) one to watch? What do Catholic, Byzantine, and biblical prophecies suggest?

Germany’s Assyrian Roots Throughout History Are the Germanic peoples descended from Asshur of the Bible? Have there been real Christians in Germanic history? What about the “Holy Roman Empire”? There is also a You-Tube video sermon on this titled Germany’s Biblical Origins.

Must the Ten Kings of Revelation 17:12 Rule over Ten Currently Existing Nations? Some claim that these passages refer to a gathering of 10 currently existing nations together, while one group teaches that this is referring to 11 nations getting together. Is that what Revelation 17:12-13 refers to? The ramifications of misunderstanding this are enormous. A related sermon is titled Ten Kings of Revelation and the Great Tribulation.

The ‘Peace Deal’ of Daniel 9:27 This prophecy could give up to 3 1/2 years advance notice of the coming Great Tribulation. Will most ignore or misunderstand its fulfillment? Here is a link to a related sermon video Daniel 9:27 and the Start of the Great Tribulation.

Who is the King of the West? Why is there no Final End-Time King of the West in Bible Prophecy? Is the United States the King of the West? Here is a version in the Spanish language: ¿Quién es el Rey del Occidente? ¿Por qué no hay un Rey del Occidente en la profecía del tiempo del fin? A related sermon is also available: The Bible, the USA, and the King of the West.

Who is the King of the North? Is there one? Do biblical and Roman Catholic prophecies for the Great Monarch point to the same leader? Should he be followed? Who will be the King of the North discussed in Daniel 11? Is a nuclear attack prophesied to happen to the English-speaking peoples of the United States, Great Britain, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand? When do the 1335 days, 1290 days, and 1260 days (the time, times, and half a time) of Daniel 12 begin? When does the Bible show that economic collapse will affect the United States? In the Spanish language check out ¿Quién es el Rey del Norte? Here are links to three related videos: The King of the North is Alive: What to Look Out For. The Future King of the North, and Rise of the Prophesied King of the North.

The Great Monarch: Biblical and Greco-Roman Catholic Prophecies Is the ‘Great Monarch’ of Greco-Roman Catholic prophecies endorsed or condemned by the Bible? Two sermons of related interest are also available: Great Monarch: Messiah or False Christ? and Great Monarch in 50+ Beast Prophecies.

Could God Have a 6,000 Year Plan? What Year Does the 6,000 Years End? Was a 6000 year time allowed for humans to rule followed by a literal thousand year reign of Christ on Earth taught by the early Christians? Does God have 7,000 year plan? What year may the six thousand years of human rule end? When will Jesus return? 2031 or 20xx? There is also a video titled 6000 Years: When will God’s Kingdom Come? Here is a link to the article in Spanish: ¿Tiene Dios un plan de 6,000 años?

The Times of the Gentiles Has there been more than one time of the Gentiles? Are we in it now or in the time of Anglo-America? What will the final time of the Gentiles be like? A related sermon is available and is titled: The Times of the Gentiles.

Lost Tribes and Prophecies: What will happen to Australia, the British Isles, Canada, Europe, New Zealand and the United States of America? Where did those people come from? Can you totally rely on DNA? What about other peoples? Do you really know what will happen to Europe and the English-speaking peoples? What about Africa, Asia, South America, and the Islands? This free online book provides scriptural, scientific, historical references, and commentary to address those matters. Here are links to related sermons: Lost tribes, the Bible, and DNA; Lost tribes, prophecies, and identifications; 11 Tribes, 144,000, and Multitudes; Israel, Jeremiah, Tea Tephi, and British Royalty; Gentile European Beast; Royal Succession, Samaria, and Prophecies; Asia, Islands, Latin America, Africa, and Armageddon; When Will the End of the Age Come?; Rise of the Prophesied King of the North; Christian Persecution from the Beast; WWIII and the Coming New World Order; and Woes, WWIV, and the Good News of the Kingdom of God.

LATEST NEWS REPORTS

LATEST BIBLE PROPHECY INTERVIEWS

0 notes

Text

Week 8: Perfect Distractions

Hi again! This week, things have been picking up speed as we approach the final countdown until our research papers/posters are due for our symposium in a little over a week. Since I’m sure my underlying stress about that will be thoroughly captured in my next blog post, this one can be reserved for the fun activities that filled this week to help distract us from our actual responsibilities here.

Last Friday was the Germany vs. Spain Euro Cup game which made it a day full of anticipation and excitement… until it became one of crushing sadness for Germans everywhere. Ok, maybe I’m exaggerating just a bit, but I’d be lying if I said you couldn’t sense the disappointment in Aachen when Germany lost in overtime in their first elimination round of the Euro Cup. Back home, I’m pretty anti-soccer/football for the theatrical fake injuries and weird penalty rules, but the passion for football culture here is infectious, and with the Euro Cup being located in Germany this year, not watching das Spiel would be like skipping a home game against Michigan State.

The main student street bars filled up a whole hour before the game, so a group of us sadly opted for one a bit further away. After trailing most of the game, Germany scored to tie it up in the last 5 minutes of regulation… only to let up a goal 15 minutes later. It was devastating, truly… or at least until we managed to remind ourselves that we are not, in fact, from Germany, and our soccer team back home wouldn't even stand a chance in a single Euro Cup game anyways… After the game, we stumbled across a heavy metal music festival happening in town and managed to catch the last band's performance. With metal being my favorite music genre, I was pretty psyched… until we realized the last band was pirate-themed and had the mosh pit “rowing” on the ground. No, no, I’m serious.

Proof there was actual rowing

Still though, I love that Aachen has so many of these live music performances throughout the summer. If I could bring anything back from the student culture here in Aachen to Ann Arbor, it would definitely be all the student run, free festivals with live music, drinks, and good vibes.

This past Saturday we visited Bonn, the former capital of West Germany. There, we started with a tour of a historical museum and learned more about Germany's development from the end of WWII to today. I’ll be visiting Berlin two weekends from now (stay tuned for that!) and after our history lesson I’m looking forward to seeing the remains of der Mauer/the Berlin Wall even more.

Part of the Germany Reunification exhibit at Haus der Geschichte in Bonn

After the tour, we split up to explore different things to do around Bonn. I more or less went the ‘Girls Day’ route which started with a delicious bowl of Ramen (oh how I’ve missed it) and a boba run. After that, we visited the Haribo superstore here and stocked up on cheap candy. Since Bonn is the birthplace of Haribo, they had two full floors of every shape, size, color, and flavor of gummy known to man.

Some (of many) Haribo candies + Ramen + and Boba = good day

One impressively cheap manicure and shopping spree later, we headed back to Aachen and relaxed after what was clearly such a taxing day of travel.

Sights from Bonn's Altstadt

On Wednesday, we traveled to a small, picture-perfect town named Monschau located about an hour's bus ride away from Aachen. Some people dream of their ‘white picket fence’, but ever since my first travels to Germany, I’ve dreamt of having one of these adorable timber-framed houses.

The picture-perfect timber-framed houses in Monschau

There's something about how quaint and cozy they look, decorated with their perfect flower baskets and colorful window panes that really makes one start thinking about early retirement and picking up knitting or butter churning. Or, I guess in the case of this town, glass blowing. Throughout Monschau, we found many souvenir shops with beautiful hand-crafted glass wares. We even found a marketplace store called the “Glashuette '' with incredible displays of glass figurines, vases, ornaments, etc. where we spent 5 euros to do our own glass blowing. Though my impeccably blown vase/plant-waterer/misc.-purpose-glass-thing probably won’t be making it back on the flight with me in one piece, it was still a fun, worthwhile experience.

Inside Glashuette: the "outdoor" indoor craft market in Monschau

After our impeccable artisanry we rewarded ourselves with ice cream in the village to perfectly complement the sunny day (Yes, it did randomly start pouring twice and cause us to say goodbye to another fallen umbrella, but still a 10/10 day by Aachen standards.)

Icecreamm <3

We ended our day in Monschau with a small hike around the outskirts of the town where we saw an incredible view of the houses from above.

Incredible views (and goats) at the top of our hike in Monschau

Tomorrow I’ll be traveling back to Dusseldorf for some pop-up fair. Not entirely sure what to expect, but with only two weekends left, I’m hoping to make this a good one! (while also trying fruitlessly to remind myself to study for German and finish my paper, but we’ll see how that part goes…)

Sarah Bargfrede

Computer Science

UROP Program in Aachen

0 notes

Text

“Throughout history Christianity has played an important role in Germany, since the 4th century within the borders on the Roman Empire and later also through the missionary activities of Irish and Scottish wandering monks in the 6th and 7th centuries.

However, Germany is also still marked by the division of the Church after the Reformation in the 16th century. Its Christian population is approximately half Catholic, half Protestant.

In the 20th century, the country experienced two World Wars Between 1933 and 1945 it was in the grip of the Nazi regime. In 1949 the western part of the country became the democratic Federal Republic of Germany, while its eastern regions became the German Democratic Republic, a Communist regime.

Political upheavals in the East, which culminated in the fall of the Berlin Wall, brought about a reunification of the two parts of Germany which formed a democratic state in 1990.

During the 1950s and 60s, a large number of so-called Gastarbeiter (guest workers) from South and South-Eastern Europe came to Germany, many of whom are now third-generation residents.

Besides the Catholic Southern Europeans, many Turkish citizens came to work in Germany who today account for the considerable proportion of Muslim inhabitants in the cities. They were joined by immigrants from Eastern Europe and, more recently, Asia and Africa.

Against this social backdrop, ecumenism, the dialog with other religions and cultures, integration, and efforts to maintain a harmonious social atmosphere are important challenges for the Church in Germany.

While the Constitution and Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany reflect our Christian heritage, we are witnessing a continuing trend towards secularization. Due to its Communist heritage, in the East of Germany the proportion of Christians is less than 20%. The vast majority of Eastern Germans are not baptized and have not heard the message of Christianity.

All the more important, then, is the motto of the XX World Youth Day— “We have come to worship Him” — which, contrary to the signs of the time—the tendency to see man as the absolute—places God in the center and makes Him the goal of all human effort. World Youth Day is a way to bear witness of Jesus Christ, the rock on which young people build their “future and a world of greater justice and solidarity” (Message on the occasion of the XX World Youth Day, no. 5). This is where the challenge comes to bear of the Ecumenical efforts of Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox Christians to be witnesses of the Gospel in Germany, a European Union Member State, and send the Christian message out into Europe.”

- Apostolic Journey of His Holiness Benedict XVI to Cologne for the 20th World Youth Day (August 18-21, 2005)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay since I remember one of the asks that disappeared, it was about what the situation is like between East Germany and West Germany today and if there are linguistic or cultural differences. (For one, if you’re interested in this, I really recommend the film Goodbye, Lenin, it’s a classic and it’s exactly about this subject and really funny and sad)

As for the linguistic side, because it’s simpler-

There are a lot of regional differences between German to begin with and I think compared to them, the differences between 'East German' German and 'West German' German are rather small. Being West German myself, I have an easier time understanding someone from Mecklenburg-Vorpommern or Brandenburg or Saxony-Anhalt than I do with someone who has a strong Bavarian, Swabian or Franconian accent, although the former were East German and the former are West German. Also they’re not necessarily more similar because they were one a specific side of the border.

There are some things that vaguely align with either region and were more common on one side - for example there are different ways to same the time, but those also predate the separation and not all 'Wessis' say it this way and all 'Ossis' say it that way.

There are some specific words and abbreviations and idioms that originated in West Germany or in East Germany, but they are mostly rooted in Hochdeutsch (Standard German) so you can conclude their meaning.

For example, in West Germany people called a supermarket a Supermarkt (generally, there are more loanwords from Western languages in 'West German') while East Germans said 'Kaufhalle'. But 'Super' and 'Markt' are both German words and even if you don't know what it means, you can conclude that it's a really great place to run your daily errands. And 'Kauf' and 'Halle' translates to 'buying hall' so you get the same idea.

In regional dialects such as Frisian or Swiss German, this would impossible, because these dialects are much older and very often have words and rules that don't exist in Standard German - not to mention they are pronounced very differently. You couldn’t deconstruct a word like that into Standard German unless they sound similar. Some researchers also said that some words were used differently and that East Germans had a stronger distinction between public and private language and make different jokes - which is pretty much a transition into the other differences. Basically, the actual use of language that came into existence because of the separation was too short-lived and too artificial to truly part of the language. Plus there was never actually an attempt by either side to create a ‘new’ German language.

I actually watched some videos about North Koreans living in South Korea and struggling with the language and I noticed that for one, that Koreans said there was a rather consistent North Korean way of speaking - but while there are certain dialects like Saxonian that are ‘typical’ East German dialects (my parents can tell you if someone comes from East or West Berlin and often which part of either just based on the way they speak), there is not ONE East German dialect. Plus, the duration and intensity of the separation cannot be compared to that of Korea. Many East Germans still listened to West German radio and watched Western television. People could talk on the phone and write letters. And before the ‘death strip’ was finished, people could even talk across the wall. So there was some interaction.

As for other differences -

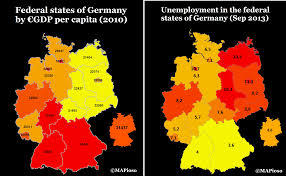

The obvious ones are the economical differences. West Germany still has a stronger economy than East Germany - a map, as an example (although it’s a bit small I know) - you can easily make out which part used to be GDR and which used to be West Germany.

The result is that many young East Germans, especially young women, move into the West to work, especially from rural regions. There are a lot of towns actually shrinking because they're only populated by old people and those who stay behind and try to make it work. At the same time, a lot of West Germans have started studying in the East because things are cheaper there. Many of them are students - so, again, young people - but they are moving into the cities like Leipzig, Potsdam or Dresden.

I definitely think there is a generational divide in the attitude East Germans and West Germans have for each other. I was born after the reunification and I've always considered all of Germany my home-country and so do pretty much all my peers and everyone up to a certain age. But my mother, for example, was born three years after the wall was first built and her entire youth, she watched it become bigger and higher and stronger - back then, she could barely imagine ever seeing a reunification and living in West Berlin, she experienced East Germany as a hostile country surrounding her and restricting her and being the cause of all the military presence - so she also didn't really see them as the other half to a whole and more of an enemy.

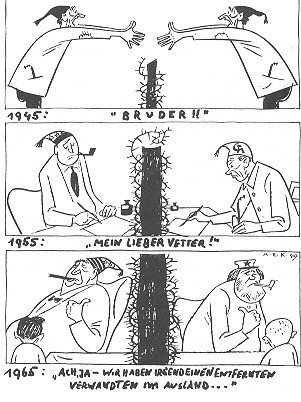

This was one of my favourite caricatures in my history books in school, it’s about the changing attitude East and West had to each other, the text says:

1945: “Brother!” 1955: “My dear cousin!” 1965: “Oh, right - we still have some distant relative living in a foreign country.”

The generation who was actually born pre-separation was born under the NS-regime and for most of them, watching the country as it was fall apart and rebuilding their lives after the war was a formative experience. This generation was all about looking forward, not back (because...looking back was very ugly, too). People who had family in the other half tried to stay in contact, make it work - but people who didn't usually had a more ambiguous relationship to all of this.

After the war, West Germany under Chancellor Adenauer's leadership was at least as eager to build relationships with the West as to reunify. And considering that occupied Germany could do very little to actually solve the whole Cold War problem all by itselves, the focus for the West was really on reconciling with France, forming a stronger European community (what would eventually turn into the European Union), rebuilding the country (Miracle on the Rhine) as well as rebuilding its international reputation. The fight to reconnect with the East (like attempts to form a 'pan'-German Olympics team) was mostly carried by individuals and organisations.

West Germany never considered itself saturated - for example, the reason that our Constitution is not called a Verfassung but a Grundgesetz a 'basic law' is that having a constitution would imply that this is a fully-formed state, when really, it was only expected to exist until the reunification. But de facto, in the 1960s and 1970s, reunification had begun to seem so unlikely that West Germany begun to ‘solidify’. I live near Bonn (the capital of West Germany) and it's interesting that the buildings the government moved into during the 1970 are much more permanent and secure (also partly because of RAF terror attacks).

You also have to keep in mind, even when the wall came down, only very few countries actually supported a reunification - many wanted the two Germanys to continue to exist as separate countries or to find a different solution. People were really worried about German reunification meaning that Germany would suddenly revert back to Nazi-Germany or, less paranoid, that a united Germany would be such an economic super-power that it would dominate the EU (...well) with only France and Britain (...well) being able to opposite it. So being too vocal about reunification for no reason was a delicate diplomatic endeavour in the decades prior to reunification. But long story short, there was always the dream of reuniting and becoming a whole new country together one day.

Which is...kinda the problem today.

Culturally, East Germany had an entirely different attitude towards itself, West Germany, its Allies and the world. It was a lot more militaristic, it was socialist and also had a very different relationship to the legacy of the NS-history and had very different international allies. For example, in SED-lingo, the “Berlin Wall” was called the “Anti-Fascist Protection Wall” (The West being the fascists.) They considered themselves a new country. West Germany considered itself the Nachfolgestaat (successor state) to Nazi Germany with all responsibilities like building a good relationship with Israel etc. while East Germany held up the communist resistance and saw themselves more as the successors of the people who fought against the Nazis. A lot of members of the SED government had actually fled Germany during the NS-regime and gone to Russia and aided the resistance from there.

I already mentioned West Germany's great plans about reuniting and becoming a whole new country together. But when the wall fell, that never happened. West Germany absorbed East Germany and moved on with no new constitution or actual negotiation. Compared to West Germany, East Germany didn't have a strong economy and it was socialist, which means that the companies were owned by the state. A state that had ceased to exist, basically. So West Germany decided on a plan to bring East Germany up to (capitalist) standard. Chancellor Kohl promised that he would turn it into 'Blühende Landschaften', 'thriving lands' (which is something West Germans often mockingly say when they're angry about something happening in East Germany, so you do the maths).

Problem with all of this was that this meant basically re-modelling the entire economy. A lot of people lost their jobs, the weaker East German currency was replaced with the West German currency and Western companies moved into East Germany.

There is this old joke about reunification: East Germany: "West Germany, West Germany, you broke your promises." West Germany: "Don't worry about it, I'll buy you a new one."

Basically, through the Solidaritätszuschlag a lot of money was invested into the East - something that to this day, many people in the West resent, especially people who come from poorer regions themselves and accuse East Germans of mismanaging money or say that cities like Leipzig or Dresden were built up to be representative for the success of the reunification while certain regions in the West like the Ruhr-region are suffering at least as much as rural regions in East Germany. These groups demand that the Solidaritätszuschlag isn’t just invested into the East but all regions that have a poor infrastructure or similar problems.

You have to understand what a big deal reunification was when it happened. To this day, it is considered the 'only peaceful revolution on German soil' and East Germans take great pride in beating that regime while West Germans consider it the fulfillment to all diplomatic ambitions the country had since it was formed. And obviously, families were reunited after decades, people could move freely - you have to keep in mind, travel was extremely restricted and now everyone could go wherever they pleased. It was the biggest, best and happiest moment in living history. And then it took a giant nose-dive in the 90s and the stereotypes of the 'whining East German' and the 'arrogant West German' were born.

For example, the poverty caused a rise in right-wing radicalism in East Germany. The country was very isolated and suddenly a lot of families lost their income and people started blaming it on immigrants. West Germans, in response, decided East Germans are all Nazis and racists and are ruining our elections.

These days, parties like the right-wing AfD are actually trying to use the 'Western is the default' culture of Germany to appeal to East Germans and presenting themselves as the only ones who will represent East Germany. That's why they're rather successful in East Germany - they actually address East Germans as a group while the other parties look out for their supporters in specific regions in the West. At the same time, many East Germans who aren't racist, aren't Nazis and aren't voting the AfD or NPD accuse West Germans (rightfully imo) of blaming all problems there are with racism in the country on the East to avoid addressing their own issues.

East German: “As if there was no racism in the West.” West German: “There is...but it’s only latent.”

I think it’s important to understand that there are cultural differences and they can’t be broken down into: “East Germany has more Nazis”. And there are different experiences people made on either side.