#shakespearian-style tragedy

Text

The King is gone. In his place, the Crowned Prince, Welsknight, rules in his lofty court. By his side, his Knight Champion, there to keep him safe until the King returns. But more dangerous than the Court is the Prince's boredom, and though Helsknight tries to do right by his Prince, what sort of knight fears laying down his life for his charge? And what resentment will build when it's demanded?

Finally finished my piece for @mcytblraufest! It is posted in it's entirety and ready to be read in all its 21k word glory!

Also, shout-out to my amazing artists for this project, @winterbyn and @thatapolloguy! Please do check them out!

You can find the compiled work they made for the fic here!

Also, if you're enjoying the fic vibes, I also made a small playlist for it! You can listen to it here!

#the barking writer#mcytblraufest2024#welsknight#helsknight#shakespearian-style tragedy#ah!! hopefully im doing this right#ive never really coordinated posting something like this before :'D

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Psychedelica of the Black Butterfly Review!!

This is my first ever official, extensive otome review!! I hope y'all enjoy, I went through so many ups and downs with this game. I hope this review inspires more people to get the game, or maybe even helps people realize it might not be for them! I also attempted to keep it as spoiler-free as possible, but there are parts that might dive into spoiler territory. I made sure to mention it, if so! Enjoy~

.

.

.

.

Psychedelica of the Black Butterfly is a visual novel developed by Otomate and published by Idea Factory in 2015, available on the PS Vita and Steam. It’s an extremely dark, gothic story with very heavy themes and romance akin to Shakespearian tragedy. When I first picked up this game, I had been previously warned about the angst it contained but nothing prepared me for what I was about to experience. This game contains themes of death, guilt, regret, grief, trauma, isolation, and more. The last time I cried so much consuming a piece of media was when I watched Les Misérables for the first time when I was 15, so that says a lot. POTBB has an iffy system, but this is easily overshadowed by the incredible storyline, jaw dropping art, compelling cast, and beautiful soundtrack.

Before we get into plot points and character routes, I’d like to talk about POTBB’s system. It’s a typical visual novel at first glance, which means mostly just clicking in order to read the text and watching the events unfold. The features that set it apart however were quite interesting- and frankly quite frustrating as well. This includes its combat system and its flowchart.

POTBB has a combat system that pops up a couple times throughout the story while you’re fighting monsters. The instructions for the combat system were very vague and confusing, especially since I played on PC where the button configurations aren’t clarified in the “Options” menu, so it was a lot of trial and error. It instructs you to shoot your gun, but not how (on PC). I had to figure out on my own that I had to use the left and right click of my mouse to shoot/lock onto targets, so the first couple of plays I was very confused and frustrated. The object of the game is to shoot as many butterflies as possible in the allotted time while also getting a good score, which is achieved by getting combos. Playing the game earns you points. Another problem is that it’s quite glitchy and hard to lock onto the butterflies properly to shoot them, but with practice you can improve (with the sacrifice of a couple of hand cramps).

The other unique thing about POTBB’s system is its flowchart, which is useful because it allows you to jump to any point in the story you’ve already unlocked, but it can be very frustrating sometimes. You’re required to use the flowchart in order to access the “Side Stories,” aka extra content you slowly unlock as you play. To access the flowchart, you have to go to the menu. The game doesn’t notify you when you’ve unlocked a Side Story, so you just have to remember to check the flowchart every once in a while to see if any have unlocked. And even if a Side Story is “unlocked”, you still have to spend your points you earned in the minigame to actually view the content. Certain character routes, endings, and choices can’t be unlocked unless you’ve viewed these Side Stories. I actually got stuck a few times during my playthrough because I didn’t realize some of the Side Stories were unlocked, and you need to read them to progress. I found that the process of scrolling through the flowchart in the middle of the story often took away from the immersion, but it wasn’t awful.

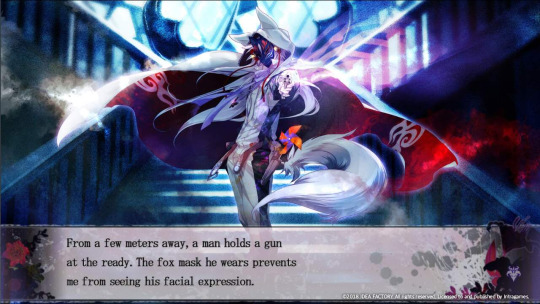

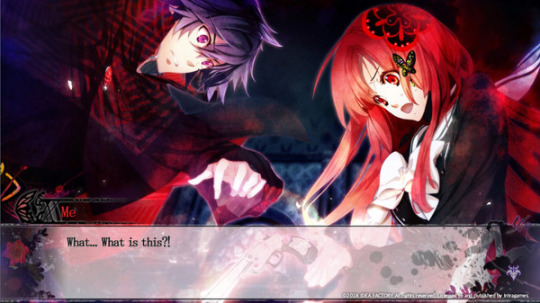

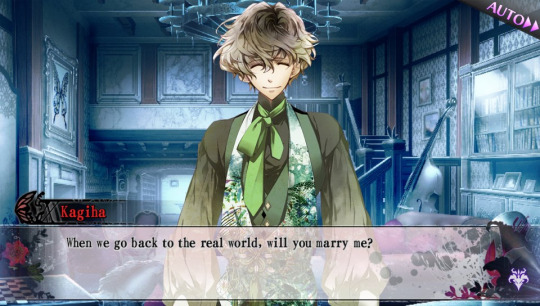

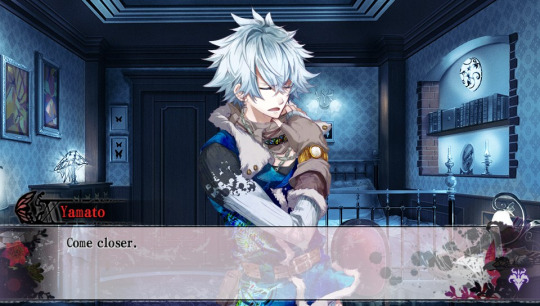

On a positive note, I have to talk about POTBB’s art, which was created by Satoru Yuiga. Yuiga has an expressive, sort of water-color art style that adds to the spiritual and mystic elements of the game. I actually didn’t like the style at first; I thought some of the character sprites looked strange, but I quickly got used to it and was soon blown away. The CGs were gorgeous and added so much life to the characters. The facial expressions were so vivid, they displayed perfect depictions of terror, shock, love… I felt every emotion through the art. I’m looking forward to playing more of Yuiga’s games just because of her art. (Images below are promotional CGs)

Now, let's talk plot! (I summarize the Common Route in this section, so feel free to skip if you consider that spoilers!) The story and characters are the best thing about this game, in my opinion. You play as a girl named Beniyuri who has just woken up in a strange mansion with no memory of her past or even herself. You see the world through Beni’s eyes as she traverses the mansion and tries to figure out what’s going on and why she’s there. The mansion is dark, gothic, and scary. Its halls seem endless, every window and door is locked, and mysterious butterflies can be seen practically everywhere. And just when things seem their darkest, Beni hears the loud roar of a beast. Two large lion-like creatures appear and attempt to attack her. Imagine if a Minotaur had a lion’s head; that’s what they look like. She thinks she’s a goner, but suddenly she’s saved by a mysterious man with dark hair and purple eyes. They hide from the monsters together, and Beni learns that this man also doesn’t have any memories. They team up and explore, eventually coming across 3 other men in the mansion who also have amnesia. The four of them find a large hall within the mansion to make their ‘base’ where they’ll be safe from the monsters. They realize that they all have phones on them, and though there isn’t any service, each of them has received one message. “Collect the shards. Complete the kaleidoscope.” They’re in this mansion for a reason, and clearly someone is pulling the strings.

I can’t go into too much detail about the individual routes because the amount of plot twists and spoilers in this game are insane. I will describe each guy and a summary of what their route meant for me and how it made me feel. Some of the routes were phenomenal in their story writing and character development, others not so much.

The first route recommended is a man named Kagiha, the 2nd person that Beni meets in the mansion, and I have complex feelings about his route. He’s a tall, soft spoken, polite man with light brown hair and green eyes. He’s very kindhearted and treats Beni with a lot of care, cheering her up when she’s depressed about their situation. Kagiha was my favorite in the beginning simply due to how kind he was. All of them were in a very depressing situation with no memories and barely any hope, so his kindness was a sort of light in that darkness. I was very excited for his route and to learn his backstory. It turns out, his route is a branch of the “Best Ending” of the game, so you get to learn the truth about almost everything as you play through his route. I certainly wasn’t expecting this. I had been warned in the past about POTBB’s bittersweet endings, but I really wasn’t prepared like I thought I was. Due to Kagiha’s circumstances (that I can’t go into detail about), his route has two endings, and neither of them are “happy” in regard to his relationship with Beni. The “Best Ending” of the game does indeed end on a happy note, but they don’t end up happy together (again due to circumstances I can’t talk about without spoiling). The “Kagiha Ending” of the game does have them end up together romantically, but with very bittersweet conditions that’s more depressing than the alternative, in my opinion. I was very upset and I cried at both endings, regretting that I loved Kagiha so much because neither ending let him and Beni be truly happy together. But even though I was upset, I have to admit that the “Best Ending” was written phenomenally and deals with the concept of death, grieving, acceptance, and change in a beautiful way. The themes in this game are very heavy but discuss them in a beautiful, important way that really gets your brain going. I sat in silence for a while after the “Best Ending” just… thinking.

After that emotional wreck, I was ready for a happy ending or at least some more closure. Hikage’s route is recommended after Kagiha, which surprised me a bit. Based off of the cover art and his introduction, he seemed to be the “poster boy.” Hikage is the first man Beni meets in the mansion, the man who saved her from the monsters. I can barely describe his route without getting into spoilers, but it was intense. I didn’t like Hikage at first because he had this misogynistic mindset and constantly scolded Beni for being “weak, just like all women” and yelled at her for “slowing them down.” I wasn’t excited for his route because obviously it meant Beni would get more of this treatment, but I was honestly surprised at what his route had in store. There’s a major plot twist within the route and you come to understand why Hikage has this mindset, and that it doesn’t come from a place of misogyny, but rather trauma. The ending to his route shocked me so much and I bawled my eyes out. It definitely ends on a bittersweet note as well, but the very last scene offers some sort of closure (though not enough, in my opinion.) I overall liked his route plot-wise and thought it was also very thought provoking, tackling themes of abuse, death, mental instability, and despair. Romantically it was okay, but I felt like it took a side-seat to the plot which can either be good or bad, depending on how much you value romance and/or get attached to the characters. Without spoiling, I can tell you that Hikage is written in a way where it makes sense that romance isn’t the focus. Thankfully I wasn’t attached to Hikage as much as Kagiha, but I still cried a river anyway…

You’d think after two routes with horrifically bittersweet endings that the whole game will probably be this way, but surprisingly, the third route in POTBB filled my heart with joy. This route centered around Yamato, who’s a short-tempered, sporty guy with ice-blue hair. He has a bit of a foul mouth, often yelling or getting angry at their situation, but never in an irrational way. Yamato actually ended up being my favorite character overall. He has an unexpected soft side and his romance with Beni was the most realistic among the cast. I also felt his route was quite tragic, despite having the happiest romantic ending in the game. Yamato and Beni’s relationship is really complex, and they actually bond over grief and guilt. Both of them harbor so much guilt in their hearts and it shackles the both of them to their pasts, but by grieving together and finding strength in one another, they’re able to push each other to move on and grow. I really enjoyed this route in a moral sense. It teaches you that it’s okay to grieve and that people grieve at different paces, and sometimes it’s okay to bond over said grief. Healing and forgiveness take time, and having someone else there to heal with you can make you both stronger. The themes in his route were so beautiful and even watching his bonds with other members of the cast grow were incredible too. He has the happiest romantic ending in the game as well, which just added to how good it was. Interestingly enough, Yamato’s route also helped me come to terms with the bittersweetness of the previous routes. I was finally able to accept the circumstances and reasonings behind the depressing endings, allowing me to appreciate the game more as a whole.

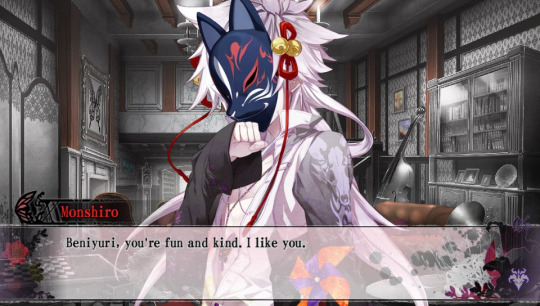

After Yamato’s romantic end, I was excited to finish the rest of the game. I prayed that this next route had a happy ending as well, and that Yamato wasn’t just an exception. I began to pursue Monshiro, who’s a mysterious man who wears a fox mask that Beni has spotted wandering the mansion sometimes. I didn’t know what to expect from him during the first bit of the game because he’s sort of absent until the end of the common route. I was pleasantly surprised, though! I learned more and more about him as I played, even in the other routes, and he’s wonderful. He’s adorable, loving, and incredibly sweet. His route tackles themes of isolation and loneliness, with Monshiro being severely traumatized due to being alone in the mansion for several years. He’s very clingy with Beni and values their relationship more than anything, his main fear being him getting left alone again. His ending was quite happy as well, but their romantic development and deep connection never really got the ending it deserved. Their bond was almost as strong as her bond with Yamato, but I feel like in the end they didn’t get to express that to each other properly. It also felt quite short to me, I wish I could have gotten more content with them that wasn’t plot-related and just focused on their bond and how much they care for each other. Overall, I enjoyed it because Monshiro is so loveable, but the ending just left me unsatisfied and begging for more.

Now, the last route was a doozy. I’d like to clarify before I begin that this is all, of course, my opinion and perspective, so don’t let this discourage you from trying the game or loving this character! I will get into minor spoilers as well here, just because it’s hard to explain my feelings without talking about what happened. The last route I played was Karasuba, who is… not the best. I can confidently say I hate him, and his route didn’t really change that for me. He has bright yellow hair and yellow eyes, so his design was already creepy to me from the start, but his personality is much worse. At first glance he seems like a funny, happy-go-lucky class clown type, but his real personality is much more twisted. He flirts with Beni so intensely to the point of sexual harassment, but then backs off and laughs, pretending it was “just a joke.” Now this is already bad enough, but he’s just incredibly rude to everyone around him as well. He demeans Beni constantly for being “naive” and “cowardly,” all with a smile on his face as he pretends he’s saying it “for her own good.” He also constantly insults the other characters, starting fights with them whenever he can and giggling about it when it’s over. The whole “reason” behind why he acts like this is because he was bullied when he was a child. He projects his insecurities onto others and thus becomes the bully he hated so much when he was younger. He does later apologize for this at the end of his route, but I felt like one sorry just wasn’t enough to atone for the way he treated everyone? He sexually harasses Beni until she starts crying at one point, then backs away and claims it was “just a joke to teach her a lesson at how dangerous men can be.” He’s just awful and I don’t think he develops very much, even in his good ending despite his apology. His bad ending was even worse, which involved him brainwashing and manipulating Beni to be with him. I know some people who enjoyed his route and while I do respect that, it’s just hard for me to understand how someone would enjoy a character like him. I do think he’s interesting because he has deep flaws and trauma and instead of growing from it, he let them taint him and he ended up becoming the very thing he hated. So, he is interesting, but that doesn’t mean he’s a good love interest for Beni or even a good character in general. If I’d have to state one major flaw about this game, it’s Karasuba’s existence and his lack of character development or redemption.

After the 5 character routes are over, you’d assume that’s the end. The game actually continues after this, though, with the “Summer Camp” ending that unlocks last. This was my favorite part of the game. It’s a “What-If” scenario where every single character gets their happy ending, and offers a lot of closure after the despair you experience in the character routes. It healed me and freshened my mind after the tragedy. It’s a wonderful inclusion and I actually cried tears of joy while playing it, due to how emotional it made me.

Overall, Psychedelica of the Black Butterfly was an emotional rollercoaster that I will never forget. While yes it has its flaws, I don’t regret playing it. The topics covered, such as isolation, death, and guilt, were so heavy and intense; but they were also so meaningful and I feel like everyone should experience them. I feel my favorite theme was the deep dive into Survivor’s Guilt and how people process and deal with it differently. The mystery surrounding the mansion and their circumstances was also very interesting and the plot twists were well executed. The whole cast is so full of life and each of their bonds are extremely complex. Beniyuri is a wonderful main character and I found myself rooting for her and her happiness the entire time. I definitely recommend this game to anyone who loves tragedy and complex plots, but I probably wouldn’t recommend this game to someone who’d be uncomfortable with really dark themes like graphic death. This game definitely took a toll on my mental health for a few days, but also offered life lessons that I’ll no doubt remember and value for a very long time.

Rating: 7/10!

#otome#otome game#otome fandom#otomate#english otome#psychedelica of the black butterfly#potbb#idea factory#otome review#otome reviews#otoge review#otoge reviews#otome games#otoge#visual novel#visual novels#visual novel review#otomes

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

🎨 for the ask game? hope you have a nice day!

🎨 favourite piece of fanart? link it!

oh gosh it's so hard to choose just one. (you too btw :'D) went thru my rbs and here's a few bangers:

technically an animation and not fan art but this animatic by volcanocraft is my favorite life mcyt animation of all time. the style is just to die for, the song choice is perfect, and while lots of traffic fan art and animations tend to be very dramatic and theatrical (which is totally fine, it rules) this is sort of a rare case where the artist manages to perfectly encapsulate the inherent silliness and comedic effect of using minecraft to tell your story. the goofiness of the little minecraft characters running and jumping around like bugs is perfectly captured which i feel like is a hard vibe to get in art sometimes

fan art that resembles renaissance paintings and even takes inspiration from said paintings is so beloved to me (i minored in art history so its very dear to me). specifically sillyfairygarden and floweroflaurelin come to mind! (thello's life series designs are also very dear to me, as the costumes they design remind me a lot of shakespearian plays, and make me imagine the life series as a shakespearian tragedy being told on a stage. as someone whos url is a shakespeare reference this also scratches a very specific niche in my brain. their bigb design is especially gorgeous and reminds me of 1996 mercutio)

cherri's life series as an rpg series is a banger, it really makes you yearn for the game to be real, it's also nostalgic of a lot of old rpgmaker games i used to play as a kid which is probably why i'm so drawn to it

i LOVE this secret life scar by felix convexsolos because i think the scene of scar standing in the wheat field is one of the unintentionally coolest most cinematic scenes from the life series, the off-putting angle and his stone-cold expression captures his silent rage, unhinged and unpredictable energy in that series so well

this double life fan art by ghost3a i'm absolutely obsessed with the colors and expressions, each pairing has different colors and the color choices for each pairing is so telling and the way each piece kind of fades into the next by having a hint of color at the bottom is awesome. i'm a sucker when it comes to bright contrasting colors used to convey emotions/feelings.

this last life mumbo by stackofeggs has always stuck with me because i feel like it captures red life mumbo really well; he's terrifying and dangerous with his end crystals but it also still kind of retains that wet cat energy mumbo always has. he's scary and unstable and fragile just like the end crystals

this bdubs by imflyingfish is SO COOL AND CUTE, the style is so unique and captivating and i love the choice to draw bdubs' building the earth arc as it's honestly the only fan art i think i've seen of that specific secret life moment

i'll end off by mentioning the Common Applestruda W, where i honestly can't even link a specific piece or i'd be here all day. but her color work and compositions are wonderful

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

It has heen well suggested that M. Amhroise Thomas's lyrical version oi Hamlet should have been called Ophelia. The question would not then have been raised in too direct a manner, whether or not Shakespear's tragedy has received worthy treatment at the hands of its operatic adaptors. Moreover, Ophelia, who is not the chief character, who is scarcely even a character of the first degree of importance, in Shakespear's Hamlet, is the principal personage, both in a musical and in a dramatic point of view, in the Hamlet prepared for the composer by MM. Barbier and Carre. Finally, the longest, most elaborate, and altogether the best scene in the operatic Hamlet y does not exist in the Hamlet of Shakespear at all. Here the name of Shakespear cannot be used against M. Thomas ; and if he had confined himself to this scene and entitled it The Death of Ophelia , one universal feeling of admiration would have been expressed for the work. The object, however, of M. Thomas was to produce not a poetical little cantata, but a grand opera containing a great part for Mdme. Nilsson ; and accordingly the scene of OpheHa's death is followed by an act which is superfluous, and is preceded by three acts which are in a great measure irrelevant. The parent notion of the opera was certainly the idea that the fair-haired, soft-voiced, Swedish soprano would be in every way an admirable representative of Shakespear's Scandinavian heroine; and so indeed she has proved. Mdme. Nilsson has deeper qualifications for the part than purely external ones, which, nevertheless, may be said to suggest others. All the sentiment of the character seems to belong to her naturally, so that as an actress alone, if she had not a note to sing, she would still be an admirable Ophelia. Then the pure fresh quality of her voice is quite in harmony with the rest of the personage. If the Shakespearian heroines may be divided into two categories, like the heroines of modern opera, Ophelia is eminently a " light soprano '* part, as Lady Macbeth is a part for a " dramatic soprano." The amount of Scandinavianism discoverable in the character of Shakespear's Ophelia, is, probably, very slight ; but M. Thomas has given a tinge of national colour to the music sung by the Ophelia of his opera. This he has done, not by the vulgar expedient of dragging in one national air in complete form, but by reproducing the character of the Swedish melodies (for operatic purposes Sweden and Denmark are one) in both the heroine's grand scenas, and by employing here and there actual passages of Swedish origin.

In the power of characterisation belonging to music lies one of the strong points of opera as a form of art. A Scotchman sings something in the Scotch style, or a Russian something in the Russian style, and the nationality of the personage is at once painted beyond the possibility of mistake. Neither does M. Thomas make any endeavour in Hamlet to give us a Scandinavian finale, wisely contenting himself with such a finale as the Hebrew-Prussian Meyerbeer might have wi-itten. Ophelia's solos are interspersed with little Scandinavian snatches ; and the villagers of the neighbourhood of Elsinore dance, in one place, to a quaint but very graceful melody which is apparently of Scandinavian origin. But another dance tune in the same scene is clearly derived from the Anglican, not to say cockneyfied, tune of *' Billy Taylor." Others, again, might have been written for any ballroom of the present day. M. Ambroise Thomas may, indeed, be acquitted of all intention

to give a Scandinavian character to his music elsewhere than in the strikingly-coloured part of Ophelia, and in the dance tunes of her young companions.

There are few characters, one would think, in all dramatic literature, less favourable for musical treatment than Hamlet. The address to the ghost, the interview between Hamlet and his mother are, to be sure, dramatic enough in the ordinary sense of the word, and furnish suitable groundwork for operatic scenes. But the character of Hamlet is chiefly known to us from the two great monologues ; and the monologues, though a composer of the very highest genius might, doubtless, be able to find appropriate music for them, are not the sort of ** words " that any ordinary composer would like to set, or could adequately deal with. M. Thomas, differing from all the Italian composers who have grappled with Shakespear, seems to have made an honourable endeavour to give to his principal personages their proper musical physiognomy. Verdi (to take a flagrant instance) makes Macbeth, in the most terrible moment of his career, when its tragic termination already stares him in the face, sing a sentimental air of the conventional pattern, which might just as well be sung by Renato in the Ballo in Maschera, and which — if it had not been written some years earlier — would be regarded as a very close imitation of Balfe's ** Come into the garden, Maud." Signor Verdi would doubtless have treated ''To be or not to be?" as he has treated the

*' words " which in the libretto of Macbeth replace *' Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased?" &c. But though his intentions would not have been so meritorious as that of M. Thomas, the thing achieyed would have been at least melodious. The air would have. had no philosophical character, but it would have been singable and what is called " expressive." It would have been, so to sa}^ in rhyme ; whereas M. Thomas's Hamlet sings persistently in blank verse. The only notable case in which the operatic Hamlet breaks into evenly -balanced, sharply-defined rhythm is (if we except a few graceful passages in the finale to the second act) in the drinking song which he addresses to his friends the players in lieu of the well-known hints on acting. Here, again, we are reminded of the scene in Macbeth where the King '^ obliges the company with a song," to be interrupted in the midst of his efiusion by Banquo's ghost. A drinking song is worth nothing in an opera if not relieved at intervals by some anti -jovial incident or reflection ; and in M. Thomas's work the necessary contrast is supplied by a passing change in Hamlet's ever-changing humour.

After Ophelia and Hamlet, the only personage whom the composer seems to have thought it worth while to characterise is the ghost. Alas ! poor ghost. At the thought of this dreadful, because preternaturally dull and dismal, apparition, we can only cry with Hamlet:

" Angels and ministers of grace defend us " — from ever meeting with such a ghost again. In the first place we deny his ghostliness. It is not the voice of a disembodied spirit that we hear, but of a dead man singing. The statue of Don Giovanni (of which it would be unfair to speak if M. Thomas did not in a certain way invite the comparison) repeats the same note to varied harmony, then repeats another note to another succession of chords ; but the dead body of the King of Denmark emits the same sound — makes the same noise, that is to say — so unintermittently for so long a time, that instead of the divine sentiment of terror inspired by the figure on horseback, we feel the sort of awe and about the same admiration that would be excited in us by the unlookedfor appearance of an undertaker's mute. However, in these operatic presentations of great di-amatic masterpieces {Faust, Mignon, Romeo and Juliet, and now Hamlet) "realism" is the great principle cultivated; and it was, perhaps, intended that the music given to the ghost of Hamlet's father should be directly suggestive of the graveyard.

Much has been said about M. Thomas's knowledge of orchestral efi'ect, but it must be possible to abuse such knowledge. "If God had given me, instead of the faculty for creating, capacity forjudging, I do not know,** said the late Alexandre Dumas in one of his most amusing prefaces, " whether I should have had wings powerful enough to raise me to the level of the poet; but I think I should have had sufficiently robust legs to be able to walk round him." Without presuming to criticise M. Thomas's orchestral work, one may say, judging only by its effect, that it is laborious and pretentious writing. It is in many cases " full of sound and fury," whatever it may signify. A melody, or fragment of melody, is often begun on one instrument, continued on a second, and finished — or left unfinished — on a third. In some of the most agitated portions of the opera the accompaniments suggest not merely agitation, but epilepsy. In others they recall the view taken of modern instrumentation by a certain satirist, who declares that its great secret consists in treating trombones as clarinets, and assigning violin passages to the bassoon. In many places, on the other hand, especially in the quieter scenes, the combinations of instruments are charming.

The composer of so many agreeable operas in the light style and of so much pretty ballet music, seems in Hamlet to have forced his talent. Yet a decided exception must be made in favour of his truly poetical Ophelia ; and opera-goers must at least thank M. Thomas for having furnished one of the most graceful and accomplished artists on the lyric stage with a part which suits her as if she had been born for it.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Christina Nilsson#Christine Nilsson#dramatic coloratura soprano#coloratura soprano#soprano#the Swedish Nightingale#Swedish Nightingale#The Nightingale#Hamlet#Ambroise Thomas#Ophelia#Paris Opera#Opéra de Paris#Opéra Paris#Ophélie#Mad Scene#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#opera history

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

You: I did not put that much thought into my characters' names | also You: ties elements from a Shakespearian tragedy to characters' names and then genderbends it as a twist | Me: ... sssssssqqQuUEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE SO COOL I did not make that connection!! Praise for you! Praise for you!! AHH

Ahaha, but I didn't really do that much and it was super brain dead lol. I'm about halfway through the third chapter and I (for the most part) like how it's turning out! If anything, it was a very good learning experience since I don't think I've ever really colored in a watercolor style before. After that chapter, there will be one involving Kat and Viktor again trying to follow Emil around, which will be done in this style! (It's flat colors + no/little pen pressure, based on pafl's art style)

I'm still debating on how I want to do backgrounds for that chapter;;

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

//I finished my reread of Children of Húrin yesterday and I guess I have thoughts?

I felt a lot less invested this time. Bearing in mind last time I read it all I was 14 and I think I missed a few chapters somehow?? I don't know how I didn't notice how dark the world was. No wonder everyone was at each others throats all the time!

I honestly didn't care about any of the deaths when reading them, although when I think about them by myself Beleg's and Gwindor's make me so sad. Guess I felt kept at arm’s length due to the writing. Maybe the style put me in Íslendingarsögur mode: get through it and organise the plot afterwards. I’m sure some plot elements were lifted straight from the family sagas though.

I felt for Túrin more this time. I don't think before I understood that it's not his fault, and some of his boneheaded decisions come from a good place. I still found him frustratingly gung-ho and oblivious but hey, maybe I don't like him because he reminds me of me.

The deaths were gratuitous and dumb. What's the point of having immortal beings if the majority of big events happen in one man's short lifetime?

Why didn't he recognise Niënor? I know she had a memory spell on her from Galurung but did Túrin never think 'she's got the same eyes/nose as me...'? Did none of the outlaws?

I feel obliged to keep my copy as it's signed by Alan Lee OwO but idk that I'll read it again save to refresh my memory.

The main victim in all this is Mablung. Coming onto the stage like a side character in a Shakespearian tragedy, sent to tidy up the literal corpses of the (anti)heroes and give some kind of exposition. No day is ever his day.

Also it’s been so so long since I read the part where Túrin kills Brodda that as I read it I thought ‘I remember this scene from somewhere...’ Yeah, probably this book. That’s how different the vibe was this time round lol.

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Since you love Obey Me!, I wanna know something: Which events are your favorites?

Personally, I've enjoyed all of the events that I've participated, but of course, I do have a hefty list of favorites...

[FYI: This list is done in an non-specific order and does not include Birthday Events]

We're All Bad Here (Wonderland themed. MC plays the role of Alice, as they explore through Wonderland in search of the Queen of Hearts);

Ruri-chan is my Bae! (Ruri-chan themed. Leviathan drives his brothers wild with his otaku obsessions);

Demon de Butler (Butler themed. To better understand relations with humans, the Demon Bros. become butlers for one week, with MC as their master);

Good Night Devil (Sleep themed. As told by Lucifer, MC must help the Demon Bros. into developing better sleeping patterns);

Whose Glass Slippers Are These? (Cinderella themed. Playing the role of Cinderella, MC lives a fairy tale fantasy);

Summer Festival (Yukata themed. The Demon Bros. enjoy a japanese-style summer festival);

Sun, Sea and Demons! + Pearls and the Beach (Beach themed. The Obligatory Beach Episodes, where the gang enjoys some summer activities);

A Surprise For You (Happy Devil Day 2k21. MC is surprised by the Demon Bros. with a special party to thank them for the pleasant memories);

Magical Eggs 🎶 What Will Hatch? (Egg themed. The gang is tasked with taking care of little monsters as a school assignment);

The Great Yokai Parade (Yokai themed. The gang participates the Hyakki Yagyō, the Night Parade of One Hundred Demons);

Paws & Claws 1 + 2/Liar Liar, Animal Attire! (Animal themed. A series of magical events where the gang turns into furries/kemonomimi);

Welcome to the Bunny Show! + Bunny Boys at Your Service (Bunny themed. The gang works at The Fall as waiters/hosts, while dressed up as Bunnies);

The Three Worlds Festival (Happy Devil Day 2k22. The exchange students organize a major event to celebrate Diavolo's long-run harmony project);

Wedding Vows (Wedding themed. The Demon Bros. organize a proposal competition to win a chance in becoming MC's groom for a wedding-themed photoshoot);

Body Swap Panic (Body/Personality Swap themed. When MC's first attempt in spellcasting goes awry, they must use their charms to set things right with the Demon Bros.);

Trick or Treat! (Happy Devil Day 2k23. The gang goes all out while organizing a Halloween-themed café at RAD);

All Aboard the S.S. Devildom! (Sailor themed. MC and the Demon Bros. get a part-time job as sailors in a luxurious cruise for the whole weekend);

Henry and the Seven Lords (TSL/Musical themed. MC and the Demon Bros. play as their TSL counterparts in a musical, directed by Simeon, the novel's author himself);

I Kid You Not (Kid themed. After a magical mishap, the gang is transformed into little children, and MC acts as their guardian for the time being);

A Devildom Halloween (The FIRST Halloween themed event ever. With Diavolo's birthday just right around the corner, the gang organizes a belated Halloween party);

A Masked Halloween (Another Halloween themed event, with a yandere-ish twist. After wearing a set of magic masks, the Demon Bros. fall under a curse and are now preying after MC's soul);

Toys Galore (Toys/kigurumi themed. The gang is spirited away to a magical world made of toys, and they must solve a puzzle to return to the Devildom without getting caught);

Get Arty With It (Art themed. Leviathan organizes a manga relay for an art project, but everyone's ideas just keep on clashing);

Twinkle Twinkle Little Star (Constellation themed. The gang is given an assignment to magically recreate a planetarium);

The Vampire Special (The second Vampire themed event. MC is advised to temporarily stay away from the Demon Bros. due to a vampiric disease);

Sacrifice of Darkness (Chuunibyou themed. The gang starts speaking in shakespearian tragedies thanks to a strange disease, and act out on cringy edgelord fantasies to cure themselves);

Like A Dame + Princess Rose (Crossdressing themed. In which we're reminded that the gender binary means nothing to ancient demons, as they dress up as Dames to please a fellow royal colleague of Diavolo's);

Blue Spring Paradise (High School themed event. Leviathan is depressed and the Demon Bros. try to cheer him up by helping him live his Slice-of-Life anime fantasies);

Halloween Prank Problems (Yet another Halloween themed event. MC has a weird dream about the Demon Bros. and the Triworlds gang engaging in a prank war);

Valentine's Day Canceled?! + A Weird White Day (V-Day themed events. The gang tries to calm down angry and heartbroken spirits so they can celebrate the holidays in peace with MC);

Happy⭐Holidays! (Christmas themed. RAD's decorating event and Diavolo's wellbeing are in jeopardy as an ancient evil threatens to ruin the holidays);

Absolute Zero (Carnival/Mardi Gras themed. MC becomes the representant of a major winter event, all the while trying to solve a huge crisis of dying crops);

Revolution of the Stained Glass Flower (Band themed. When ancient demonic treasures are unearthed, a powerful reality-bending relic is discovered).

1 note

·

View note

Text

So the thing about Moby Dick is that, like. It's a weird book, right?

For one thing there's the sliding between genres thing, in that there's everything from Shakespearian-style soliloquies to lengthy, Homeric metaphors, to anatomical studies, to flights of philosophy & theology---to say nothing of how the first-person narration will just quietly slip fully into another character's head without commenting on it at all. And it's not that it's exactly hidden that Ishmael is an unreliable narrator---plus there's the whole thing where Queequeg says they're married as he'd all "oh, silly Queequeg not understanding English, we just slept in the same (one-time bridal) bed & spooned & cuddled pillow-talked, he just means we're best buds :D"; like....sure, Jan. By the by, this book is one of the most homoerotic texts this side of the Iliad that I've encountered. And speaking of homoeroticism, what can I even say about the chapter where the crew has to constantly work the spermaceti found in the sperm whale's head with their hands in order to keep it at the proper consistency, which our narrator blithely describes as "squeezing the sperm."

Aside from all of that though, it's completely fascinating how, the longer the voyage goes on, the more the style of the story begins to dip into a kind of magical realism---I can't help but think about a moment near the end of the book where Ahab has declared that all the crew is an extension of himself, a collection of limbs for him to manipulate; because that's kind of what ends up happening. The captain is the ship & the crew is the captain and the ship is the crew, and at that moment individuality dissolves and the Pequod becomes one single organism, going up against the great organism of the white whale. Is that why Ishmael gives us the thoughts and feelings of so many of his crewmates? Was it a gesture towards that eventual (and, per the themes of the novel, fated) experience of the Pequod, or a result of it? What does this have to do with the theme of cannibalism? I'm actually fascinated by that particular theme, especially in how it plays into the crew's interactions with whales---of course they're killing them & rendering their fat for oil, and it's a grisly process that the book describes, but outside of those times the whales are described more or less as people, with emotions and family relations and desires and so on.

And hell, I haven't even touched on how, in some ways, Ishmael as a character is defined more by what he doesn't say than by what he does---I'm particularly struck by how, after Queequeg's near-fatal fever, both he and Ishmael begin to disappear from the text; Queequeg is only alluded to as one of the group of harpooners, while Ishmael stops giving any information about anything he's assumedly doing as part of his literal job on the ship. It's only after the ill-fated final encounter with Moby Dick that we even learn where he was at the time everything was going on. It's almost like, the closer the story gets to its inevitable tragedy, the more Ishmael wants to distance himself from it (maybe that's part of the reason for his digressions---if he didn't "pad out” the story so to speak, he'd have to actually talk about what happened). That may also be why he stops mentioning Queequeg, even though he told us near the beginning that he stuck to his, uh, companion "like a barnacle" ever since Nantucket---like, he can talk about his near-death, but his actual death is a wound too painful to touch.

Hell, Ishmael doesn't say a single word about how he feels about seeing the Pequod sink, or how he felt in the minutes and hours after---or even about where he was when it happened!---until the Epilogue, which is less than a single page. For all of that, though, the last sentence in the book fucking breaks me. I listened to an audiobook version as this my first experience of the story, but all the same when I came to that line and it was all over I had to just stare at the wall for a little bit.

#I DID SAY I HAVE TO BE ANNOYING ABOUT THIS BOOK NOW SO HERE I AM STILL ON MY BS#i would've word-vomitted even more BUT I FUKCIN RAN OUT OF CHARACTERS SOMEHOW

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Importance of Antiheroes

By Brooksie C. Fontaine (me) and Sara R. McKearney

Few tropes are as ubiquitous as that of the hero. He takes the form of Superman, ethically and non-lethally thwarting Lex Luthor. Of Luke Skywalker, gazing wistfully at twin suns and waiting for his adventure to begin. In pre-Eastwood era films, a white Stetson made the law-abiding hero easily distinguishable from his black-hatted antagonists. He is Harry Potter, Jon Snow, T’Challa, Simba. He is of many incarnations, he is virtually inescapable, and he serves a necessary function: he reminds us of what we can achieve, and that regardless of circumstance, we can choose to be good. We need our heroes, and always will.

But equally vital to the life-blood of any culture is his more nebulous and difficult to define counterpart: the antihero. Whereas the hero is defined, more or less, by his morality and exceptionalism, the antihero doesn’t cleanly meet these criteria. Where the hero tends to be confident and self-assured, the antihero may have justifiable insecurities. While the hero has faith in the goodness of humanity, the anthero knows from experience how vile humans can be. While the hero typically respects and adheres to authority figures and social norms, the antihero may rail against them for any number of reasons. While the hero always embraces good and rejects evil, the antihero may do either. And though the hero might always be buff, physically capable, and mentally astute, the antihero may be average or below. The antihero scoffs at the obligation to be perfect, and our culture's demand for martyrdom. And somehow, he is at least as timeless and enduring as his sparklingly heroic peers.

Which begs the question: where did the antihero come from, and why do we need him?

The Birth of the Anti-Hero:

It is worth noting that many of the oldest and most enduring heroes would now be considered antiheroes. The Greek Heracles was driven to madness, murdered his family, and upon recovering had to complete a series of tasks to atone for his actions. Theseus, son of Poseidon and slayer of the Minotaur, straight-up abandoned the woman who helped him do it. And we all know what happened to Oedipus, whose life was so messed up he got a complex named after him.

And this isn’t just limited to Ancient Greece: before he became a god, the Mesoamerican Quetzalcoatl committed suicide after drunkenly sleeping with his sister. The Mesopotamian Gilgamesh – arguably the first hero in literature – began his journey as a slovenly, hedonistic tyrant. Shakespearian heroes were denoted with an equal number of gifts and flaws – the cunning but paranoid Hamlet, the honorable but gullible Othello, the humble but power-hungry MacBeth – which were just as likely to lead to their downfall as to their apotheosis.

There’s probably a definitive cause for our current definition of hero as someone who’s squeaky clean: censorship. With the birth of television and film as we know it, it was, for a time, illegal to depict criminals as protagonists, and law enforcement as antagonists. The perceived morality of mainstream cinema was also strictly monitored, limiting what could be portrayed. Bonnie and Clyde, The Good the Bad and the Ugly, Scarface, The Godfather, Goodfellas, and countless other cinematic staples prove that such policies did not endure, but these censorship laws divorced us, culturally, from the moral complexity of our most resonant heroes.

Perhaps because of the nature of the medium, literature arguably has never been as infatuated with moral purity as its early cinematic and T.V. counterparts. From the Byronic male love interests of the Bronte sisters, to “Doctor” Frankenstein (that little college dropout never got a PhD), to Dorian Grey, to Anna Karenina, to Scarlett O’Hara, to Holden Caulfield, literature seems to thrive on morally and emotionally complex individuals and situations. Superman punching a villain and saving Lois Lane is compelling television, but doesn’t make for a particularly thought-provoking read.

It is also worth noting, however, that what we now consider to be universal moral standards were once met with controversy: Superman’s story and real name – Kal El – are distinctly Jewish, in which his doomed parents were forced to send him to an uncertain future in a foreign culture. Captain America punching Nazis now seems like a no-brainer, but at the time it was not a popular opinion, and earned his Jewish creators a great deal of controversy. So in a manner of speaking, some of the most morally upstanding heroes are also antiheroes, in that they defied society’s rules.

This brings us to our concluding point: that anti-heroes can be morally good. The complex and sometimes tragic heroes of old, and today’s antiheroes, are not necessarily immoral, but must often make difficult choices, compromises, and sacrifices. They are flawed, fallible, and can sometimes lead to their own downfall. But sometimes, they triumph, and we can cheer them for it. This is what makes their stories so powerful, so relatable, and so necessary to the fabric of our culture. So without further ado, let’s have a look at some of pop-culture’s most interesting antiheroes, and what makes them so damn compelling.

Note: For the purposes of this essay, we will only be looking at male antiheroes. Because the hero’s journey is traditionally so male-oriented, different standards of subversiveness, morality, and heroism apply to female protagonists, and the antiheroine deserves an article all her own.

Antiheroes show us the negative effects of systematic inequalities (and what they can do to gifted people.)

As demonstrated by: Tommy Shelby from Peaky Blinders.

Why he could be a hero: He’s incredibly charismatic, intelligent, and courageous. He deeply cares for his loved ones, has a strict code of honor, reacts violently to the mistreatment of innocents, and demonstrates surprisingly high levels of empathy.

Why he’s an antihero: He also happens to be a ruthless, incredibly violent crime lord who regularly slashes out his enemies’ eyes.

What he can teach us: From the moment Tommy Shelby makes his entrance, it becomes apparent that Peaky Blinders will not unfold like the archetypical crime drama. Evocative of the outlaw mythos of the Old West, Tommy rides across a smoky, industrialized landscape. He is immaculately dressed, bareback, on a magnificent black horse. A rogue element, his presence carries immediate power, causing pedestrians to hurriedly clear a path. You get the sense that he does not conform to this time or era, nor does he abide by the rules of society.

The ONLY acceptable way to introduce a protagonist.

Set in the decades between World War I and II, Peaky Blinders differentiates itself from its peers, not just because of its distinctive, almost Shakespearian style of storytelling, powerful visual style, and use of contemporary music, but also in the manner in which it shows that society provokes the very criminality it attempts to vanquish. Moreover, it dedicates time to demonstrating why this form of criminality is sometimes the only option for success in an unfair system. When the law wants to keep you relegated to the station in which you were born, success almost inevitably means breaking the rules. Tommy is considered one of the most influential characters of the decade because of the manner in which he embodies this phenomenon, and the reason why antiheroes pervade folklore across the decades.

Peaky Blinders engenders a unique level of empathy within its first episodes, in which we are not just immersed in the glamour of the gangster lifestyle, but we understand the background that provoked it. Tommy, who grew up impoverished and discriminated against due to his “didicoy” Romany background, volunteered to fight for his country, and went to war as a highly intelligent, empathetic young man. He returned with the knowledge that the country he had served had essentially used him and others like him as canon fodder, with no regard for their lives, well-being, or future. Such veterans were often looked down upon or disregarded by a society eager to forget the war. Having served as a tunneler – regarded to be the worst possible position in a war already beset by unprecedented brutality – Tommy’s constant proximity to death not only destroyed his faith in authority, but also his fear of mortality. This absence of fear and deference, coupled with his incredible intelligence, ambition, ruthlessness, and strategic abilities, makes him a dangerous weapon, now pointed at the very society that constructed him to begin with.

It is also difficult to critique Tommy’s criminality, when we take into account that society would have completely stifled him if he had abided by its rules. As someone of Romany heritage, he was raised in abject poverty, and never would have been admitted into situations of higher social class. Even at his most powerful, we see the disdain his colleagues have at being obligated to treat him as an equal. In one particularly powerful scene, he begins shoveling horse manure, explaining that, “I’m reminding myself of what I’d be if I wasn’t who I am.” If he hadn’t left behind society’s rules, his brilliant mind would be occupied only with cleaning stables.

However, the necessity of criminality isn’t depicted as positive: it is one of the greatest tragedies of the narrative that society does not naturally reward the most intelligent or gifted, but instead rewards those born into positions of unjust privilege, and those who are willing to break the rules with intelligence and ruthlessness. Each year, the trauma of killing, nearly being killed, and losing loved ones makes Tommy’s PTSD increasingly worse, to the point at which he regularly contemplates suicide. Cillian Murphy has remarked that Tommy gets little enjoyment out of his wealth and power, doing what he does only for his family and “because he can.” Steven Knight cites the philosophy of Francis Bacon as a driving force behind Tommy’s psychology: “Since it’s all so meaningless, we might as well be extraordinary.”

This is further complicated when it becomes apparent that the upper class he’s worked so arduously to join is not only ruthlessly exclusionary, but also more corrupt than he’s ever been. There are no easy answers, no easy to pinpoint sources of societal or personal issues, no easy divisibility of positive and negative. This duality is something embraced by the narrative, and embodied by its protagonist. An intriguingly androgynous figure, Tommy emulated the strength and tenacity of the women in his life, particularly his mother; however, he also internalized her application of violence, even laughing about how she used to beat him with a frying pan. His family is his greatest source of strength and his greatest weakness, often exploited by his enemies who realize they cannot fall back on his fear of mortality. He feels emotions more strongly than the other characters, and ironically must numb himself to the world around him in order to cope with it.

However, all hope is not lost. Creator Steven Knight has stated that his hope is ultimately to redeem Tommy, so by the show’s end he is “a good man doing good things.” There are already whispers of what this may look like: as an MP, Tommy cares for Birmingham and its citizens far more than any “legitimate” politicians, meeting with them personally to ensure their needs are met; as of last season, he attempted a Sinatra-style assassination of a rising fascist simply because it was the right thing to do. “Goodness” is an option in the world of Peaky Blinders; the only question is what form it will take on a landscape plagued by corruption at every turn.

Regardless of what form his “redemption” might take, it’s negligible that Tommy will ever meet all the criteria of an archetypal hero as we understand it today. He is far more evocative of the heroes of Ancient Greece, of the Old West, of the Golden Age of Piracy, of Feudal Japan – ferocious, magnitudinous figures who move and make the earth turn with them, who navigate the ever-changing landscapes of society and refuse to abide by its rules, simultaneously destructive and life-affirming. And that’s what makes him so damn compelling.

Who needs traditional morality, when you look this damn good?

Other examples:

Alfie Solomons from Peaky Blinders. Tommy’s friend and sometimes mortal enemy, the two develop an intriguing, almost romantic connection due to their shared experiences of oppression and powerful intellects. Steven Knight has referred to Alfie as “the only person Tommy can really talk to,” possibly because he is Tommy’s only intellectual equal, resulting in a strange form of spiritual matrimony between the two.

Omar Little from The Wire, an oftentimes tender and compassionate man who cares deeply for his loved ones, and does his best to promote morality and idealism in a society which offers him few viable methods of doing so. He may rob drug dealers at gunpoint, but he also refuses to harm innocents, dislikes swearing, and views his actions as a method of decreasing crime in the area.

Chiron from Moonlight, a sensitive and empathetic young man who became a drug dealer because society had provided him with virtually no other options for self-sustenance. The same could be said for Chiron’s mentor and father figure, Juan, a kind and nurturing man who is also a drug dealer.

To a lesser extent, Tony from The Sopranos, and other fictional Italian American gangsters. The Sopranos often negotiates the roots of mob culture as a response to inequalities, while also holding its characters accountable for their actions by pointing out that Tony and his ilk are now rich and privileged and face little systematic discrimination.

Walter White from Breaking Bad – an underpaid, chronically disrespected teacher who has to work two jobs and still can’t afford to pay for medical treatment. More on him on the next page.

Antiheroes show us how we can be the villains.

As demonstrated by: Walter White from Breaking Bad.

Why he could be a hero: He’s a brilliant, underappreciated chemist whose work contributed to the winning of a Nobel Prize. He’s also forging his own path in the face of incredible adversity, and attempting to provide for his family in the event of his death.

Why he’s an antihero: In his pre-meth days, Walt failed to meet the exceptionalism associated with heroes, as a moral but socially passive underachiever living an unremarkable life. At the end of his transformation, he is exceptional at what he does, but has completely lost his moral standards.

What he can teach us: G.K. Chesterton wrote, “Fairy tales do not tell children that the dragons exist. Children already know that dragons exist. Fairy tales tell children the dragons can be killed.” Following this analogy, it is equally important that our stories show us we, ourselves, can be the dragon. Or the villain, to be more specific, because being a dragon sounds strangely awesome.

Walter White of Breaking Bad is a paragon of antiheroism for a reason: he subverts almost every traditional aspect of heroism. From the opening shots of Walt careening along in an RV, clad in tighty whities and a gas mask, we recognize that he is neither physically capable, nor competent in the manner we’ve come to expect from our heroes. He is not especially conventionally attractive, nor are women particularly drawn to him. He does not excel at his career or garner respect. As the series progresses, Walt does develop the competence, confidence, courage, and resilience we expect of heroes, but he is no longer the moral protagonist: he is self-motivated, vindictive, and callous. And somehow, he still remains identifiable, which is integral to his efficacy.

But let us return to the beginning of the series, and talk about how, exactly, Walt subverts our expectations from the get-go. Walt is the epitome of an everyman: he’s fifty years old, middle class, passive, and worried about identifiable problems – his health, his bills, his physically disabled son, and his unborn baby. Whereas Tommy Shelby’s angelic looks, courage, and intellect subvert our preconceptions about what a criminal can be, Walt’s initial unremarkability subverts our preconceptions about who can be a criminal. The hook of the series is the idea that a man so chronically average could make and distribute meth.

Just because an audience is hooked by a concept, however, does not mean that they’ll necessarily continue watching. Breaking Bad could have easily veered into ludicrosity, if it weren’t for another important factor: character. Walt is immediately and intensely relatable, and he somehow retains our empathy for the entirety of the series, even at his least forgivable.

When we first meet Walt, his talents are underappreciated, he’s overqualified for his menial jobs, chronically disrespected by everyone around him, underpaid, and trapped in a joyless, passionless life in which the highlight of his day is a halfhearted handjob from his distracted wife. And to top it all off? He has terminal lung cancer. Happy birthday, Walt.

We root for him for the same reason we root for Dumbo, Rudolph, Harry Potter: he’s an underdog. The odds are stacked against him, and we want to see him triumph. Which is why it’s cathartic, for us and for Walt, when he finally finds a profession in which he can excel – even if that profession is the ability to manufacture incredibly high-quality meth. His former student Jesse Pinkman – a character so interesting that there’s a genuine risk he’ll hijack this essay – appreciates his skill, and this early appreciation is what makes his relationship with Jesse feel so much more genuine than Walt’s relationship with his family, even as their dynamic becomes increasingly unhealthy and Walt uses Jesse to bolster his meth business and his ego. This deeply dysfunctional but heartfelt father-son connection is Walt’s tether to humanity as he becomes increasingly inhumane, while also demonstrating his descent from morality. It has been pointed out that one can gauge how far-gone Walt is from his moral ideals by how much Jesse is suffering.

But to return to the initial point, it is imperative that we first empathize with Walt in order to adequately understand his descent. Aside from the fact that almost all characters are more interesting if the audience can or wants to empathize with them, Walt’s relatability makes it easy to understand our own potential for toxic and destructive behaviors. We are the protagonist of our own story, but we aren’t necessarily its hero.

Similarly, we understand how easily we can justify destructive actions, and how quickly reasonable feelings of anger and injustice swerve into self-indulgent vindication and entitlement. Walt claims to be cooking meth to provide for his family, and this may be partially true; but he also denies financial help from his rich friends out of spite, and admits later to his wife Skylar that he primarily did it for himself because he was good at it and “it made (him) feel alive.”

This also forces us to examine our preconceptions, and essentially do Walt’s introspections for him: whereas Peaky Blinders emphasize the fact that Tommy and his family would never have been able to achieve prosperity by obeying society’s laws, Walt feels jilted out of success he was promised by a meritocratic system that doesn’t currently exist. He has essentially achieved our current understanding of the American dream – a house with a pool, a beautiful wife and family, an honest job – but it left him unable to provide for his wife and children or even pay for his cancer treatment. He’s also unhappy and alienated from his passions and fellow human beings. With this in mind, it’s understandable – if absurd – that the only way he can attain genuine happiness and excel is through becoming a meth cook. In this way, Breaking Bad is both a scathing critique of our current society, and a haunting reminder that there’s not as much standing between ourselves and villainy as we might like to believe.

So are we all slaves to this system of entitlement and resentment, of shattered and unfulfilling dreams? No, because Breaking Bad provides us with an intriguing and vital counterpoint: Jesse Pinkman. Whereas Walt was bolstered with promises that he was gifted and had a bright future ahead of him, Jesse was assured by every authority figure in his life that he would never amount to anything. However, Jesse proves himself skilled at what he’s passionate about: art, carpentry, and of course, cooking meth. Whereas Walt perpetually rationalizes and shirks responsibility, Jesse compulsively takes responsibility, even for things that weren’t his fault. Whereas Walt found it increasingly acceptable to endanger or harm bystanders, Jesse continuously worked to protect innocents – especially children – from getting hurt. Though Jesse suffered immensely throughout the course of the show – and the subsequent movie, El Camino – the creators say that he successfully made it to Alaska and started a carpentry business. Some theorists have supposed that Jesse might be a Jesus allegory – a carpenter who suffers for the sins of others. Regardless of whether this is true, it is interesting, and amusing to imagine Jesus using the word “bitch” so often. Though he didn’t get the instant gratification of immediate success that Walt got, he was able to carve (no pun intended – carpentry, you know) a place for himself in the world.

Jesse isn’t a perfect person, but he reminds us that improving ourselves and creating a better life is an option, even if Walt’s rise to power was more initially thrilling. So take heart: there’s a bit of Heisenberg in all of us, but there’s also a bit of Jesse Pinkman.

The savior we all need, but don’t deserve.

Other examples:

Bojack from Bojack Horseman. Like Walt, the audience can’t help but empathize with Bojack, understand his decision-making, and even see ourselves in him. However, the narrative ruthlessly demonstrates the consequences of his actions, and shows us how negatively his selfishness and self-destructive qualities impact others.

Again, Tony Soprano. Tony, even at his very worst, is easy to like and empathize with. Despite his position as a mafia Godfather, he’s unfailingly human. Which makes the destruction caused by his actions all the more resonant.

Antiheroes emphasize the absurdity of contemporary culture (and how we must operate in it.)

As demonstrated by: Marty Byrde from Ozark.

Why he could be a hero: He’s a loving father who ultimately just wants to provide for and ensure the safety of his family. He’s also fiercely intelligent, with excellent negotiative, interpersonal, and strategic skills that allows him to talk his way out of almost any situation without the use of violence.

Why he’s an antihero: He launders money for a ruthless drug cartel, and has no issue dipping his toes into various illegal activities.

Why he’s compelling: Marty is an antihero of the modern era. He has a remarkable ability to talk his way into or out of any situation, and he’s also a master of using a pre-constructed system of rules and privileges to his benefit.

In the very first episode, he goes from literally selling the American Dream, to avoiding murder at the hands of a ruthless drug cartel by planning to launder money for them in the titular Ozarks. Despite his long history of dabbling in illegality, Marty has no firearms – a questionable choice for someone on the run from violent drug kingpins, but a testament to his ability to rely on his oratory skills and nothing else. He doesn’t hesitate to engage an apparently violent group of hillbillies to request the return of his stolen cash, because he knows he can talk them into giving it back to him. The only time he engages other characters in physical violence, he immediately gets pummeled, because physical altercation has never been his form of currency. Not that he’s subjected to physical violence particularly often, either: Marty is a master of the corporate landscape, which makes him a master of the criminal landscape. He is brilliant at avoiding the consequences of his actions.

It’s easy to like and admire Marty for his cleverness, for being able to escape from apparently impermeable situations with words as his only weapon. He’s got a reassuring, dad-ly sort of charisma that immediately endears the viewer, and offers respite from the seemingly endless threats coming from every direction. He unquestionably loves his family, including his adulterous wife. As such, it’s easy to forget that Marty is being exploited by the same system that exploits all of us: crony capitalism. The polar opposite of meritocratic capitalism – in which success is based on hard work, ingenuity, and, hence the name, merit – crony capitalism benefits only the conglomerates that plague the global landscape like cancerous warts, siphoning money off of workers and natural capital, keeping them indentured with basic necessities and the idle promise of success.

Marty isn’t benefiting from his hard work in the Ozarks. Everything he makes goes right back to the drug cartel who continuously threatens the life of him and his family. He is rewarded for his efforts with a picturesque house, a boat, and the appearance of success, but he is not allowed to keep the fruits of his labor. Marty may be an expert at navigating the corporate and criminal landscape, but it still exploits him. In this manner, Marty embodies both the American business, the American worker, and a sort of inversion of the American dream.

In this same manner, Marty, the other characters, and even the Ozarks themselves embody the modern dissonance between appearance and reality. Marty’s family looks like something you’d respect to see on a Christmas card from your DILF-y, successful coworker, but it’s bubbling with dysfunctionality. His wife is cheating on him with a much-older man, and instead of confronting her about it, he first hired a private investigator and then spent weeks rewatching the footage, paralyzed with options and debating what to do. The problem somewhat solves itself when his wife’s lover is unceremoniously murdered by the cartel, and Wendy and Marty are driven into a sort of matrimonial business partnership motivated by the shared interest of protecting their children, but this also further demonstrates how corporate even their family dealings have become. His children, though precocious, are forced to contend with age-inappropriate levels of responsibility and the trauma of sudden relocation, juxtaposed with a childhood of complete privilege up until this point.

Conversely, the shadow of the Byrde family is arguably the Langmores. Precocious teenagers Ruth and Wyatt can initially be shrugged off as local hillbillies and budding con-artists, but much like the Shelby family of the Peaky Blinders, they prove to be extremely intelligent individuals suffering beneath a society that doesn’t care about their stifled potential. Systemic poverty is a bushfire that spreads from one generation to the next, stoked by the prejudices of authority figures and abusive parental figures who refuse to embrace change out of a misguided sense of class-loyalty.

Almost every other character we meet eventually inverts our expectations of them: from the folksy, salt-of-the-earth farmers who grow poppies for opium and murder more remorselessly than the cartel itself, to the cookie-cutter FBI agent whose behavior becomes increasingly volatile and chaotic, to the heroin-filled Bibles handed out by an unknowing preacher, to the secrets hidden by the lake itself, every detail conveys corruption hidden behind a postcard-pretty picture of tranquility and success.

Marty’s awareness of this illusion, and what lurks behind it, is perhaps the greatest subversion of all. Marty knows that the world of appearance and the world of reality coexist, and he was blessed with a natural talent for navigating within the two. Like Walter White, Marty makes us question our assumptions about who a criminal can be – despite the fact that many successful, attractive, middle-aged family men launder money and juggle criminal activities, it’s still jarring to witness, which tells us something about how image informs our understanding of reality. Socially privileged, white-collar criminals simply have more control over how they’re portrayed than an inner-city gang, or impoverished teenagers. However, unlike Walt, Marty’s criminal activities are not any kind of middle-aged catharsis: they’re a way of life, firmly ingrained in the corporate landscape. They were present long before he arrived on the scene, and he knows it. He just has to navigate them.

Just like our shining, messianic heroes can teach us about truth, justice, and the American way, so too does each antihero have something to teach us: they teach us that society doesn’t reward those who follow its instructions, nor does it often provide an avenue of morality. Even if you live a life devoid of apparent sin, every privilege is paid for by someone else’s sacrifice. But the best antiheroes are not beacons of nihilism – they show us the beauty that can emerge from even the ugliest of situations. Peaky Blinders is, at its core, a love story between Tommy Shelby and the family he crawled out of his grave for, just as Breaking Bad is ultimately a deeply dysfunctional tale of a father figure and son. Ozark, like its predecessors, is about family – the only authenticity in a society that operates on deception, illusion, and corruption. They teach us that even in the worst times and situations, love can compel us, redeem us, bind us closer together. Only then can we face the dragons of life, and feel just a bit more heroic.

Other examples:

Don Draper from Mad Men. A similarly Shakespearian figure for the modern era, Don is a man who appears to have everything – perfect looks, a beautiful wife and children, a prestigious job. He could have stepped out of an ad for the American Dream. And yet, he feels disconnected from his life, isolated from others by the very societal rules he, as a member of the ad agency, helps to propagate. It helps that he’s literally leading a borrowed life, inherited from the stolen identity of his deceased fellow soldier, and was actually an impoverished, illegitimate farmboy whose childhood abuse permanently damaged his ability to form relationships. The Hopper-esque alienation evoked by the world of Mad Men really deserves an essay all it’s own, and his wife Betty – whose Stepford-level mask of cheerful subservience hides seething unhappiness and unfulfilled potential – is a particularly intriguing figure to explore. Maybe in my next essay, on the importance of the antiheroine.

#my writing tips#writing tips#tommy shelby#peaky blinders#walter white#breaking bad#jesse pinkman#bojack horseman#don draper#writing advice#antihero#the types of antiheroes#long post for ts

984 notes

·

View notes

Text

I decided to create a list of media anti shippers would be trying to ban of they actually believed the bullshit they spewed, and didn't just want to take the moral high ground in shipping arguments. This list isn't comprehensive by any means, just what I could think of snow. Feel free to add to it. I certainly will be.

Lolita

Heathers

Beetlejuice

Game of Thrones/ASOIAF

Gone Girl

The Hunger Games

Twilight

Most YA novels actually. Also anything that depicts a minor having sex, because God forbid teenagers explore their sexuality through the safe medium of fiction

Fifty Shades of Grey

Actually make that most, if not all "bodice ripper" style romance books

Hannibal the show/ the Hannibal lecter books and movies

Anything written by Stephen King

Most of the horror genre in general

Dracula

Anne Rice's vampire series.

The true blood TV show and books, though that's kinda with the bodice riper category

Romeo and Juliet

Supernatural

The Simpsons

Futurama

Basically any adult western cartoon

Hamlet, Othello, Macbeth. Basically any Shakespearian tragedy.

The Odyssey, The Illiad

Any depiction of the Hades and Persephone myth

Any depiction of a lot of myths from many cultures actually, including norse, judeo-christian, greek, hindu, shinto, celtic, etc. Buddhist myths are ok though, I think.

Most accurate depictions of life in different time periods. Unless they steer well away from the problematic aspects of that time period.

Death note, talentless nana, assassination classroom, jojos bizarre adventure, attack on titan, parasite, flcl, evangellion, any anime with a yandere, any harem anime, any psychological anime. Just. A lot of anime.

Anything with a villain protagonist

Any story that veers into morally grey territory

These are all I could think of in half an hour, but there are so many is ridiculous.

Note how many of these fictional works are also those that conservative Christians want to ban 🤔

#pro shipping#anti censorship#shipping discourse#fan fiction#ao3#i can wait to come on here and say these works SHOULD be banned#i will die laughing

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Has anyone done a BBC ghosts au where mike is the one to start seeing ghosts? Because the potential is there!

Whether Mike suffers the same Julian caused injury as Alison did in canon, or gains an injury in a different way is up to you.

Mikes reaction to everything would be far different from Alisons, mostly in that I don't think he'd be as able to flat out ignore the ghosts (as we saw in the poker night, his first instinct is to oblige others) However he would also stick to his belief that it was all a delusion for far longer.

Alison in Mikes shoes would be far less likely to just go along with everything. While mike had an attitude of 'i am very concerned about everything that is going on right now, but i'll see where you are going with it.' I believe Alison would have a more 'Ok, no. This is deeply concerning and we are doing this instead.' approach.

I can see Mike and Pat getting along great! Just two friendly guys who chat and make some absolutely awful jokes. They immediately hit it off. The only time I can see them not getting along is if everyone was watching TV, Mike seems the type to talk about and make fun of the programme , and we already know how Pat gets.

Kitty tends to want him to pass messages to alison more than she wants to just chat with him, but he is happy to answer her questions and thinks she is quite nice.

Thomas is unable to talk to his crush, and can only talk to her though the man she loves. He marks as a Shakespearian style tragedy. In reality it plays out as Mike trying to talk to him, Thomas finding something to be mortally offended by, and then retreating to the lake or the window to pontificate about loves barred from one another by nature, time, and man. How if only he could talk to her, they could be together (when we know exactly how him talking to her plays out)