#selections from truisms

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

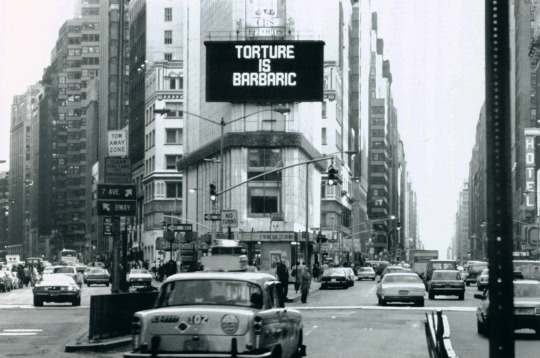

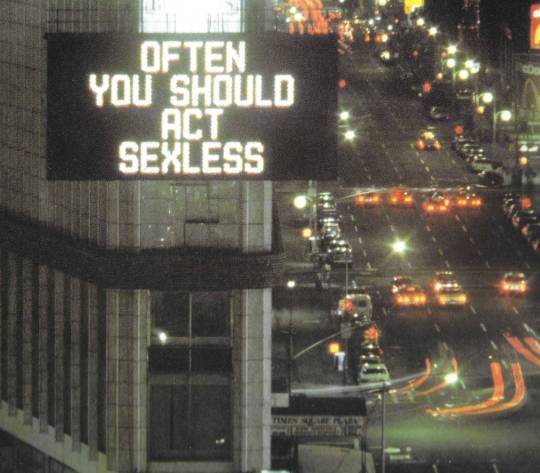

Jenny Holzer, Selections from Truisms, Spectacolor Board, 20' x 40', Installation, Public Art Fund Inc., Times Square, New York, New York, 1982

#art#design#Times Square#Jenny Holzer#Selections from truisms#truisms#slogan#saying#advertisement#torture is barbaric#installation#Public Art#public art fund#New York

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

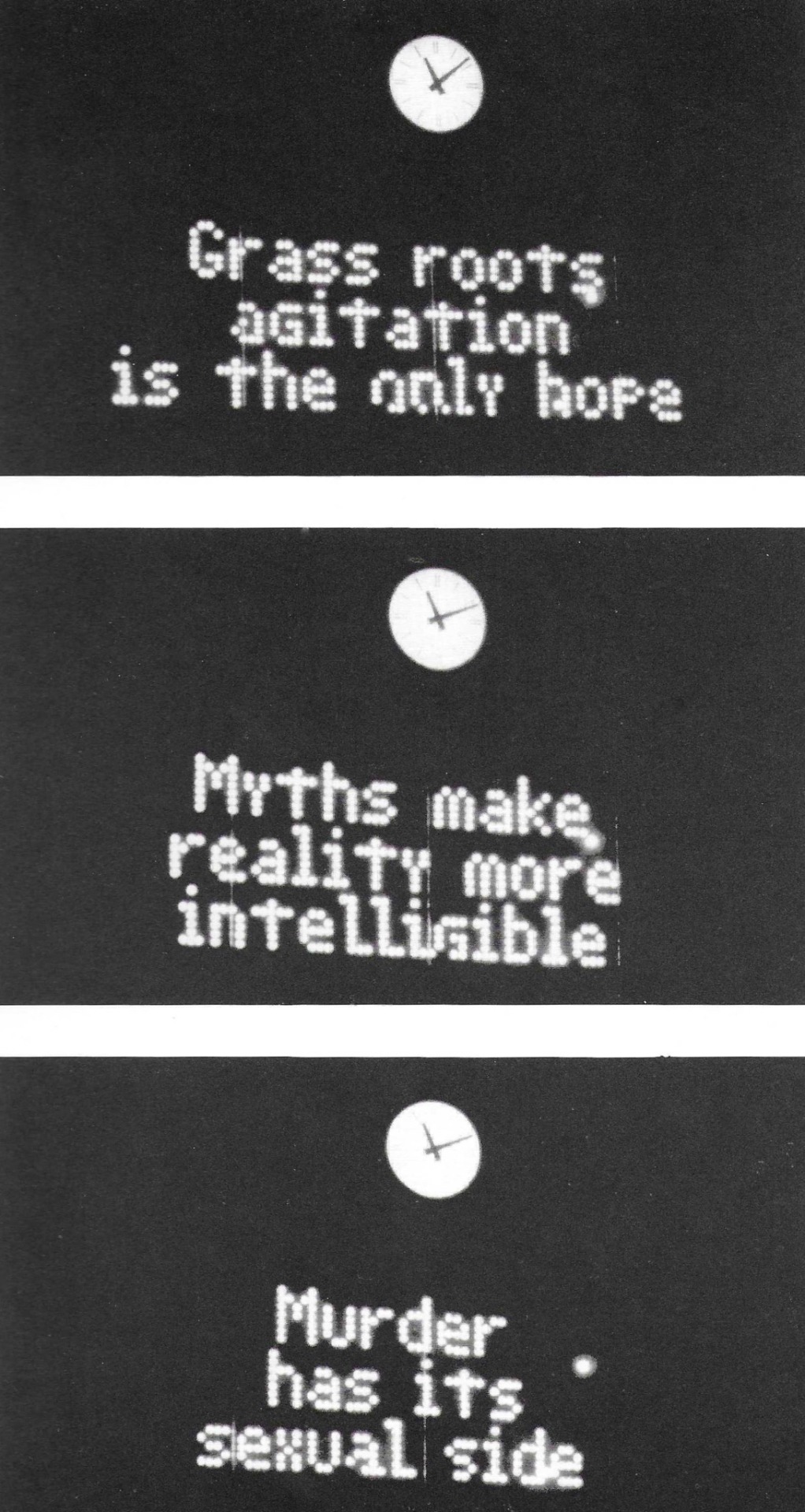

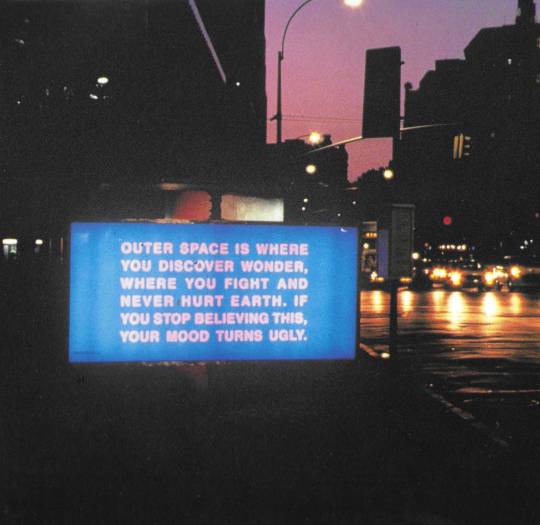

selections from 'truisms,' 1986 in jenny holzer - diane waldman (1989)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Jenny Holzer Untitled (Selections from Truisms, Inflammatory Essays, The Living Series, The Survival Series, Under a Rock, Laments, and Child Text), 1989 Tricolor L.E.D. electronic-display signboard Dimensions variable

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

:: January 16 :: Selection for Week 3 of 2025 :: 🐝" a study in scarlet" (1887) from the daily sherlock holmes: a year of quotes*🖊️

"They say that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains," he remarked with a smile. "It's a very bad definition, but it does apply to detective work."

In seeing this quote on its own, rather than embedded within a passage on a page, a few things stood out together, catching my eye: Holmes raising the topic of genius (and it arriving as it does in the very first Holmes and Watson tale); and then dropping it, so to speak, by saying the definition is false; and his smile :-) [I love Holmes's smiles, those times when he is amused at the human foibles he comes across -- antithetical to the image of Holmes-as-a-machine.]

The inaccurate definition for genius -- that it is "an infinite capacity for taking pains" -- is, however, Holmes says, a fine definition for detective work. And so, via something like a literary transitive principle, detective work isn't genius; it's something more accessible, well, as long as one does more than sees, but observes :-) I love that this assertion comes up in the first outing for Holmes and Watson, in Section 3 of Part 1 of A Study in Scarlet.

I got to thinking about where the definition came from, and it turns out that it's a phrase that has proverbial status in Great Britain in the latter nineteenth-century -- "they say" fits with that observation. But most sources add that this phrase was widely-known due to the fact that Thomas Carlyle, a celebrated historian, made this claim in his biography of Frederick the Great, which aided in it being widely-circulated. And guess what! Carlyle turns up previous to this, in Section 2 of Part I of A Study in Scarlet! It's when Watson is making his list of Sherlock's deficiencies: "Of contemporary literature, philosophy and politics he appeared to know next to nothing. Upon my quoting Thomas Carlyle, he inquired in the naivest way who he might be and what he had done. My surprise reached a climax, however, when I found incidentally that he was ignorant of the Copernican Theory and of the composition of the Solar System." So perhaps this is a between-the-lines kind of thing that at least partly accounts for Sherlock's smile -- a smile that perhaps tips off the reader that, despite Watson's assertion in the earlier part of the story, that he, like anyone else, is acquainted with Carlyle :-) And that Sherlock Holmes is thus a dissident when it comes to trafficking in cultural truisms, and provides a clue that he's going to be an idiosyncratic character . . . and that he already enjoys teasing Watson a bit, even if Watson isn't yet wise to his ways.

......................................

[*Levi Stahl and Stacey Shintani, eds., U of Chicago Pr, 2019 ]

#re-considering BBC Sherlock by dipping into ACD canon#quotations#reading between the lines#john watson#sherlock holmes#sherlock fic#weekly sherlockian epigraphs 2025#by me :-)#thegildedbee

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Among President Donald Trump’s lizard-brain intuitions is that Americans are overwhelmed by choice. This exhaustion is a strangely underexplored reason for his appeal; it may even help explain why his heavy use of executive power (verging on what some experts have no problem calling authoritarianism) is often met with shrugs and blank stares.

Just to take one surprising example: Last month, Trump swept away worries about his tariff war raising the cost of an array of consumer products by suggesting that children didn’t need so many toys (“I don’t think a beautiful baby girl needs—that’s 11 years old—needs 30 dolls”)—to which a chorus on the anti-consumerist left responded, Yeah, you’re probably right. Although most observers interpreted Trump’s comments as a gaffe (because what president since Jimmy Carter has suggested that Americans should scrimp?), the journalist Alissa Quart wrote that Trump had “unwittingly” put his finger on a real problem, that “American kids are being overly defined by material goods and they and we need to buy less.” Writing in Slate, Rebecca Onion, also holding her nose, admitted that “American parenthood is an intense encounter with the excesses of the consumer economy, where the acquisition of stuff feels like it’s not in your control.”

Much of Trump’s schtick—the aspiration to wear a crown (literally), the assertion that “I alone can fix it,” the ostentatious governing through reward and punishment—can be seen as a leader offering his subjects relief from the burden of making decisions. This is not to say that Trump has developed such a supreme case for himself as Daddy, but rather that his popularity reveals the readiness of Americans to turn to one. The desire to have someone else choose might have to do with just how valueless our many options have become. Think of the expansive selection of “mid” TV shows to pick from on Netflix, or the nearly infinite number of possible sexual partners that fly by on Tinder, or the agony of selecting a candidate at the polls (among either, usually, two flawed politicians or, as in New York City’s ranked-choice Democratic primary, so many candidates that consensus feels unreachable).

The notion that Trump is the wrong answer to the right question has become something of a truism for liberals. But perhaps he is, in this unintended way, pointing us to the end of “choice idolatry.” This is the phrase that the historian Sophia Rosenfeld uses in her recent book, The Age of Choice, which sets out to explain how freedom came to be synonymous with having an endless number of possible doors to open, and how wrapped up our sense of self is with the ability “to make one’s own personally satisfying choices, with a minimum of impediments, from among a range of options.” She uses idolatry for a distinct reason, suggesting that we might be reaching a golden-calf moment: As shiny and captivating as choice has been for so long, it is revealing itself as a hollow source of identity and a distraction from what really matters.

Rosenfeld, who teaches at the University of Pennsylvania, calls herself a “historian of the taken-for-granted.” (A previous book of hers traced the history of common sense.) The presumption that freedom equals choice is the kind of fixed notion she is primed to deconstruct. To think of humans as a species that revels in possibility—unlike, say, anteaters or mice, who are not exactly seeking out novelty—seems self-evident. But Rosenfeld’s book demonstrates just how recent and culturally constructed this definition is, a seeping consequence of social and psychological developments over the past 300 years that gradually saturated the way people came to see themselves.

Ceasing to think of freedom as the possession of many options would be no small rupture. What might take its place? Abandoning a consumerist worldview might not be the worst thing for humanity, and for Americans in particular—it might lead to a sturdier value system, maybe one more concerned with the common good. But the resulting vacuum could just as easily be filled by Trump’s idea of freedom, one based on power and sovereignty over others, and on screwing the other guy before he screws you. The cruelty of this vision almost demands a reinvigoration of choice, an effort to salvage what had made this human impulse so liberating to begin with.

For Rosenfeld, the first inklings of our choosiness could be glimpsed in Western Europe in the late 17th century. Picture a woman walking into a store that sells calicos, which were ornamental pieces of cotton from India printed with varied and colorful designs of flowers, birds, and the like. These were some of the first pieces of frippery available, sold at a price point that made them accessible to more than just the rich. No longer was the act of buying goods one of provisioning, asking for flour or butter from behind the counter. Now the products were on display, Rosenfeld writes, “hung from hooks inside shops or on the side of entranceways in enticing folds that stretched down to the floor in a simulation of women’s copious skirts.” This was not mere sustenance; it was seduction.

During the century that followed, choice exploded. Soon, sales catalogs laying out the choicest wares were read for pleasure, presenting opportunities to fantasize. A new style of eating establishment, by the 1790s exemplified in the Parisian bistro, offered expanding menus of meats and sauces and drinks in hundreds of possible variations.

The habits of mind that formed around these activities altered the way people thought about their lives. This is Rosenfeld’s central contention. But shopping was soon perceived to have a moral cost; it was seen, she writes, “as emancipatory and as selfish and indulgent.”An anxiety attached itself to choice even as the rituals of consumption were becoming ingrained—the coveting, the browsing, the haggling, the price comparison.

Shopping guides emerged to help guard against making bad choices. The Tea Purchaser’s Guide; or, The Lady and Gentleman’s Tea Table and Useful Companion, in the Knowledge and Choice of Teas, authored anonymously by “A Friend to the Public,” could be considered a kind of 18th-century Wirecutter. Such compendia were created to avoid choosing according to “fancy” or “whim,” two vices that made their appearance in novels of the time, as did a new stock female character: the coquette. This was the woman who exercises her power to choose by browsing extensively but also withholding a decision. She teases. As Rosenfeld emphasizes throughout her history, such excesses were often projected onto women, who were accused of causing “social and moral decay” through their frivolity and unexpected economic power.

The shopping revolution was as significant as the more obvious political revolts that occurred around the same time. The philosophers of liberalism and the authors of new constitutions may have provided a language for talking about individual freedom, but it was the consumer’s habit, in Rosenfeld’s framing, that eventually trickled down and transformed political systems into expressions of personal preference.

Because of the dangers of unhindered possibility, the expansion of choice came with guardrails, rules meant to stave off anarchy and social disorder. The use of dance cards at 19th-century balls—another of Rosenfeld’s charmingly idiosyncratic examples—expanded women’s agency in choosing a mate. The little booklets allowed a woman to create a menu of options, but they also precluded a free-for-all—it was highly improper, for example, to dance with the same partner for more than a waltz or two.

With the introduction of the secret ballot, in the Yorkshire town of Pontrefract in 1872, choice idolatry conquered its last frontier: voting. No longer would elections be noisy, populous affairs in which candidates would treat voters to food and drink in a shared good time for all. No longer would political choice be the result of something like a public caucus, a ritual that mostly just codified already existing social alliances. The secret ballot began as an “experiment,” as one local paper put it, in which one was to go “alone and unbefriended to a compartment,” in the words of another, and indicate one’s favored candidate. This solitary physical act soon became, Rosenfeld writes, “what modern freedom is supposed to feel like.” The secret ballot became the most fundamental of rights in a democracy. Attention turned to the question of who should secure this right, and understandably so: Women and minority groups understood its power, even as an emblem (recall Afghan women in 2014 proudly raising their ink-stained fingers to indicate that they had taken part).

Yet even before that first ballot was shoved into a box, some saw the shift from the communal act of voting, messy as it had been, to the purely individual as carrying its own problems. Writing in 1861, John Stuart Mill, a champion of liberalism, worried about what would be let loose in the secrecy of the voting booth, where an elector might be encouraged to “use a public function for his own interests, pleasures or caprice.” Voters would think of their choices as a way “to please themselves,” or as an expression of their “personal interests, or class interest, or some mean feeling in his own mind.” The whole process, Mill argued, would move voting away from a referendum on a community’s values and toward an act of whimsy, like browsing from an array of calico clothes.

The 20th century only further solidified the idea of choice as the paramount freedom, which also meant shedding some of the guardrails of earlier eras. Many economists came to perceive an individual as the sum of their preferences, a choosing machine, Homo economicus, acting rationally and always maximizing the collective good through their own self-interest. The celebration of market-based individualism hit a peak when Milton Friedman’s neoliberalism triumphed in the 1980s. Friedman once wrote that “the freedom of people to control their own lives in accordance with their own values is the surest way to achieve the full potential of a great society.”

At the same time, paradoxically, the 20th century provided much reason for skepticism about how much control humans really have over their choices. Freud revealed the subterranean sources of our desires; advertisers manipulate our taste for breakfast cereals as well as presidents. In this century, at least to a behavioral psychologist such as the late Daniel Kahneman, even the question of free will seems unsettled. This insecurity is particularly glaring in a world of proliferating algorithms that serve us more of what they predict we will want and AIs that offer to do the thinking for us.

If choice is the “useless and exhausted idiom” that Rosenfeld suggests it might be by the end of her history, then maybe the concept is worth abandoning altogether. Doing so, she writes, would be akin to asking “if we are done with capitalism and democracy and their special offspring, human rights”—if we are ready, that is, to throw out the dominant principle of the contemporary world.

I don’t think we are. But if choice has indeed become an end unto itself, absent a set of principles for actually making choices, then something has gone awry.

Abortion rights is a telling test case. In the late 1960s, feminists began using the slogan “My Body, My Choice” to argue for the legalization of abortion in order to make it seem to be a self-evident right: Americans would never stand in the way of freedom, and to be free was to have choices. But what is clearer now, after the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, which overturned Roe v. Wade, is that the pro-choice argument was fragile. It gave conservatives the chance to challenge the consumerist-sounding appeal to “choice” with the more moral-sounding appeal of “life.” But even more damning are critiques of this framing from the left. The decision to rely on “choice,” Rosenfeld writes, made access to abortion “solely a civil right, a right to fulfill individual desires without government interference, not a social or economic right framed in response to essential needs or a matter of social justice.” She explains that this made abortion seem like “something for sale exclusively to those who had the resources—financial, familial, and psychological—to select it in a reproductive marketplace.”

Is it possible to make an argument for abortion without resorting to choice idolatry? I began to hear an inkling of this possibility during the recent presidential campaign. Access to abortion was presented not as a matter of personal bodily autonomy but as a public-health concern. In one memorable speech, Michelle Obama painted a dire picture of what would happen to women if, because of abortion bans, they didn’t get “the care” they needed; to the male partners of these women, she said, “You will be the one pleading for somebody, anybody, to do something.” Kamala Harris, in her one debate with Trump, also turned to images of medical distress—of “pregnant women who want to carry a pregnancy to term suffering from a miscarriage, being denied care in an emergency room.” Rather than appealing to women’s personal agency, Harris invoked other values: communal care and well-being.

What I picked up in this tonal shift was a realization among liberals, conscious or not, that just arguing for having choices was not enough. It matters how you choose and what you choose. What matters is the moral choice in question, the stakes—in this case, what we value more: the health and happiness of the mother, or the existence of her fetus.

This is a harder debate to have, and it demands making a more profound argument than one simply in favor of choice, but it is also more rewarding. In his 1946 lecture “Existentialism Is a Humanism,” Jean-Paul Sartre compared making moral choices to “the construction of a work of art.” The decisions you make at every juncture are what make you. This is as true of a person’s life as it is of a society. “Freedom could be reconfigured as the chance to do what one ought rather than simply what one desired,” Rosenfeld writes. Releasing ourselves from choice idolatry doesn’t have to mean letting someone else—an imperial president, for instance—decide for us. It means separating good choices from bad, understanding these categories as the ones that matter, delineating them alongside our fellow citizens. This, rather than just being drunk on options, should be the sweet slog of modernity.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

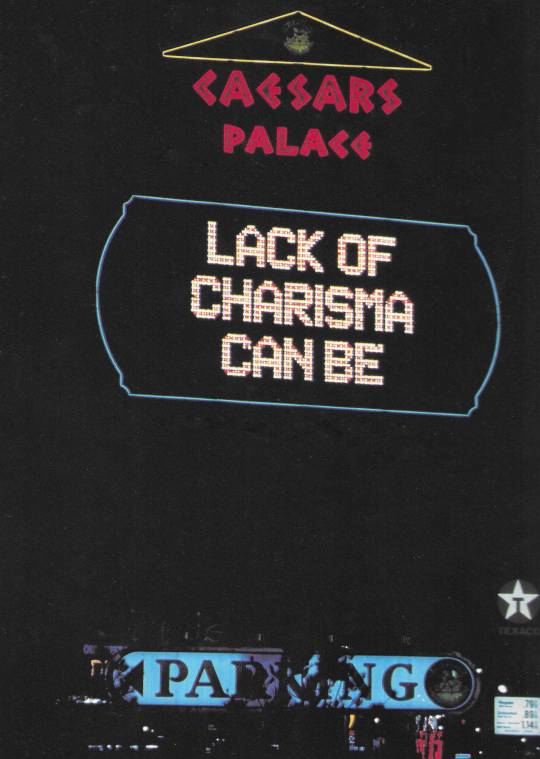

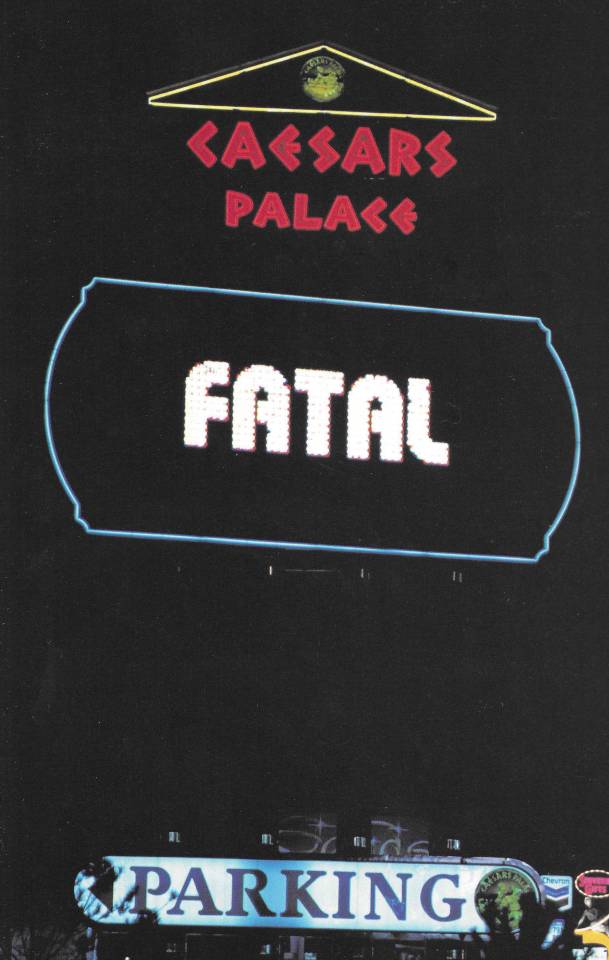

selections from 'truisms,' 1985 in jenny holzer - diane waldman (1989)

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINTS&READING: FRIDAY, DECEMBER 20, 2024

december 7_december 20

St. AMBROSE BISHOP OF MILAN (397)

This is the world into which St. Ambrose was born in Trier (Treves) about 339-40, not long after the first ecumenical council of Nicaea in 325. His father, Ambrose, a civil servant, was Gaul's praetorian prefect (governor). His command included Spain, the Netherlands, and Britain. Ambrose had one brother, Satyrus, and a sister, Marcellina, who became a nun in 353, though she continued to live as a religious at home (there were few regular convents). Ambrose was not baptized as a child because Christians still regarded any sin after baptism with such horror that the sacrament was postponed as long as possible. There was. However, a service of exhortation and benediction Witchsalt and the Sign of the Cross was employed to claim the child for God and to withdraw him from the dominance of the powers of evil. All we have of Ambrose’s childhood is a legendary tale that a swarm of bees settled on his mouth as a prophecy that he would be gifted with eloquence. Upon his father's death, while Ambrose was still young, the family moved back to Rome. The brothers were tutored by a Roman priest named Simplician, whom the boys loved (he later succeeded Ambrose as bishop of Milan). Their education ended in the study of law.

The two brothers began practicing law in the court of the prefect of Italy. Their oratory and learning attracted the notice of Ancius Probus, the prefect of Italy. Ambrose was particularly marked for the fast track. When Ambrose was little more than 30 (c. 372), Emperor Valentinian appointed him ‘consular’ or governor of Aemilia and Liguria, whose capital was Milan, the administrative center of the imperial government in the West since the beginning of the 4th century. He filled this position with great ability and justice.

The Arian Bishop Auxentius of Milan, who banned Catholic congregations from worshipping in the diocese’s churches, died in 374, and the Arians and Catholics fought over the vacant position, which exercised a metropolitan’s jurisdiction over the whole of northern Italy. Ambrose had only been in Milan for three years at the bishop’s death and expected trouble selecting his successor. So, Ambrose, a Catholic in name but still a catechumen, went to the cathedral to try to calm the rival parties. During his speech exhorting the people to concord and tranquility, a child is said to have cried, “Ambrose for bishop!” Both sides took up the cry, neither of which was anxious to decide the issue between them. The local bishops had asked Emperor Valentinian to make the appointment, but he returned the dubious honor to the bishops. Now, the matter was out of their hands. Ambrose was unanimously elected bishop by all parties. The election of Ambrose, the one in charge of the local police, heightens our awareness of a truism: all clergy are recruited from the laity. It is better to choose an irreproachable person esteemed by all, than a savant who sows discord. Ambrose's choice was bold, but it surprised no one but us. What did Ambrose think of this call? At first, he protested (just like the prophets), saying he was not even baptized and fled rather than yield to the tumult. St. Paulinus of Nola wrote of the incident: “Ambrose left the church and had his tribunal prepared. . . . Contrary to his custom, he ordered people submitted to torture. When this was done, the people did not acclaim him any the less [saying]: ‘May his sin fall on us!’ Knowing that Ambrose had not been baptized, the people of Milan sincerely promised him a remission of all his sins by the grace of baptism. “Troubled, Ambrose returned to his house. . . . Openly, he had prostitutes come in for the sole purpose, of course, that once the people saw that, they would go back on their decision. But the crowd only cried all the louder: ‘May your sin fall on us'” (Paulinus, Life of Ambrose, 7). The people, however, continually pursued him and insisted that he take the see. The emperor confirmed the nomination, and Ambrose capitulated. Beginning on November 24, 373, Ambrose was taken through baptism and the various orders to be consecrated as bishop on December 1 or 7–one or two weeks later.

Quite consciously, Ambrose set out to be an exemplary bishop despite the daunting divisions within his see, his own delicate constitution, and his lack of preparation. He was a slight figure with a beard and mustache but with the natural grace of one who had been born in a palace and who could handle authority. (An early 5th-century portrait in a church he founded shows him as a short man with a long face, long nose, high forehead, brown hair, thick lips, and a left eyebrow higher than his right.) His natural dignity was ignited by enthusiasm to correct wrongs (such as high taxation, corrupt officials, venality in the law courts, and Arians in the imperial court). On his election, he dedicated himself to an austere life and the in-depth study of the Church Fathers and Scriptures under the direction of his former tutor, Father Simplician–essentially doing his seminary work after his consecration. Following his election, his life was one of poverty and humility. He gave away all his acquired property. He gave his inherited possessions into the charge of his brother Satyrus, who had resigned from his own governorship. Ambrose was a man of charity.

Sold church property to buy back captives taken in wars. He distinguished himself in defense of the oppressed, and there is a strikingly modern note in his objection to capital punishment. This left Ambrose free to follow the life he considered appropriate to the clergy: prayer seven times daily and regular fasts (although the Church of Milan followed the Eastern rule about Saturday and did not, as the Romans did, keep it as a fast), and no food until dinner. He gave daily audiences to any who wished to consult him, then occupied himself with reading and writing. His favorite writers were Philo, Origen, and Basil. He was a Greek scholar and read most of the Greek Fathers (but seems unfamiliar with the Latin Fathers such as Tertullian and Justin Martyr). He also read heretical works to refute them. As bishop, Ambrose felt he was primarily responsible for the instruction of catechumens and would himself hear confessions before he actually administered Baptism. Ambrose always washed their feet whenever he baptized new Christians, even though he knew this was not the usual Roman custom. As a metropolitan, Ambrose had to occasionally summon councils to deal with appeals from the various dioceses and set the date for the observance of Easter. He also had to preside at the election and consecration of bishops. Episcopal duties at this time are well summed up by Chateaubriand, “There could be nothing more complete or better filled than a life of the prelates of the fourth and fifth centuries. A bishop baptized, absolved, preached, arranged private and public penances, hurled anathemas or raised excommunications, visited the sick, attended the dying, buried the dead, redeemed captives, nourished the poor, widows, and orphans, founded almshouses and hospitals, ministered to the needs of his clergy, pronounced as a civil judge in individual cases, and acted as arbitrator in differences between cities. He published at the same time treatises on morals, on discipline, on theology. He wrote against heresiarchs and against philosophers, busied himself with science and history, directed letters to individuals who consulted him in one or other of the rival religions; corresponded with churches and bishops, monks, and hermits; sat at councils and synods; was summoned to the audience of Emperors, was charged with negotiations, and was sent as ambassador to usurpers or to Barbarian princes to disarm them or keep them within bounds. The three powers, religious, political, and philosophical were all concentrated in the bishop...” Continue reading @ St Ambrose (source).

VENERABLE NILUS, MONK, OF STOLBEN LAKE (1554)

Saint Nilus of Stolobnoye was born into a peasant family in a small village of the Novgorod diocese. In the year 1505 he was tonsured at the monastery of Saint Savva of Krypetsk (August 28) near Pskov. After ten years in ascetic life at the monastery he set out to the River Sereml, on the side of the city of Ostashkova; here for thirteen years he led a strict ascetic life in incessant struggle against the snares of the devil, who took on the appearance of reptiles and wild beasts. Many of the inhabitants of the surrounding area started coming to the monk for instruction, but this became burdensome for him and he prayed God to show him a place for deeds of quietude. Once, after long prayer he heard a voice saying, “Nilus! Go to Lake Seliger. There upon the island of Stolobnoye you can be saved!” Saint Nilus learned the location of this island from people who visited him. When he arrived there, he was astonished by its beauty.

The island, in the middle of the lake, was covered over by dense forest. Saint Nilus found a small hill and dug out a cave, and after a while he built a hut, in which he lived for twenty-six years. To his exploits of strict fasting and stillness [ie. hesychia] he added another—he never lay down to sleep, but permitted himself only a light nap, leaning on a prop set into the wall of the cell.

The pious life of the monk frequently roused the envy of the Enemy of mankind, which evidenced itself through the spiteful action of the local inhabitants. One time someone set fire to the woods on the island where stood the saint’s hut, but the flames went out in miraculous manner upon reaching the hill. Another time robbers forced their way into the hut. The monk said to them: “All my treasure is in the corner of the cell.” In this corner stood an icon of the Mother of God, but the robbers began to search there for money and became blinded. Then with tears of repentance they begged for forgiveness.

Saint Nilus performed many other miracles. He would refuse gifts if the conscience of the one offering it to him was impure, or if they were in bodily impurity.

Aware of his approaching end, Saint Nilus prepared a grave for himself. At the time of his death, an igumen from one of the nearby monasteries came to the island and communed him with the Holy Mysteries. Before the igumen’s departure, Saint Nilus prayed for the last time, censing around the holy icons and the cell, and surrendered his soul to the Lord on December 7, 1554. The translation of his holy relics (now venerated at the church of the Icon of the Mother of God “Of the Sign” in the city of Ostashkova) took place in the year 1667, with feast days established both on the day of his death and on May 27.

Source: Orthodox Church in America_OCA

1 Timothy 3:1-13

1 This is a faithful saying: If a man desires the position of a bishop, he desires a good work. 2 A bishop then must be blameless, the husband of one wife, temperate, sober-minded, of good behavior, hospitable, able to teach; 3 not given to wine, not violent, not greedy for money, but gentle, not quarrelsome, not covetous; 4 one who rules his own house well, having his children in submission with all reverence 5 (for if a man does not know how to rule his own house, how will he take care of the church of God?); 6 not a novice, lest being puffed up with pride he fall into the same condemnation as the devil. 7 Moreover he must have a good testimony among those who are outside, lest he fall into reproach and the snare of the devil. 8 Likewise deacons must be reverent, not double-tongued, not given to much wine, not greedy for money, 9 holding the mystery of the faith with a pure conscience. 10 But let these also first be tested; then let them serve as deacons, being found blameless. 11 Likewise, their wives must be reverent, not slanderers, temperate, faithful in all things. 12 Let deacons be the husbands of one wife, ruling their children and their own houses well. 13 For those who have served well as deacons obtain for themselves a good standing and great boldness in the faith which is in Christ Jesus.

Luke 21:28-33

28 Now when these things begin to happen, look up and lift up your heads, because your redemption draws near. 29 Then He spoke to them a parable: "Look at the fig tree, and all the trees. 30 When they are already budding, you see and know for yourselves that summer is now near. 31 So you also, when you see these things happening, know that the kingdom of God is near. 32 Assuredly, I say to you, this generation will by no means pass away till all things take place. 33 Heaven and earth will pass away, but My words will by no means pass away.

#orthodoxy#orthodoxchristianity#easternorthodoxchurch#originofchristianity#spirituality#holyscriptures#wisdom#bible#gospel#faith#saint

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Neptune Akoya (she/her). District 4 Tribute. 58. Michelle Yeoh.

There was a misunderstanding throughout all of Panem about District Four Tributes. Most people didn’t understand how they were Careers - trained killers - when the people who entered the Arena tended to be so mellow, down-to-earth, and humble. The image of a District Four Tribute did not align with those from One and Two, who sought glory, violence, and fame. The highly trained and focused Tributes from Four did not seem coherent with the District’s otherwise rebel-leaning sentiment, where they opposed much of what the Capitol did and stood for while sending Volunteer after trained Volunteer into the Games.

It came down to one word: community.

Community was everything in Four, and to Neptune Akoya. A deep distrust of government was instilled in her early, and a commitment to her District was similarly taught. After all - when the government eventually fell, District Four would have to take care of District Four. No one else would, and no one else could. This truism permeated through Neptune’s entire life. Whether that meant sharing her daily catch with a neighbor who didn’t fare as well, leaning on her family when she was injured on the boats, or training from birth to enter the Hunger Games, Neptune was solely focused on bettering the place she called home.

Yes, the Hunger Games were an integral part of District Four culture. Where Districts One and Two saw fame and glory, and many of the outer Districts saw tyrannical punishment, District Four saw them as a golden opportunity. Anytime Four brought home a Victor, that meant abundant food and resources for the District for a full six months. That was six months of time that could be spent shoring up for the next famine, or spent rebuilding walls and roads, or delving into the vibrant arts that District Four could create when taken care of. It meant that every citizen of Four was fed - not just those who could feed themselves. In short, winning the Games was the ultimate way to care for your community. And that wasn’t all; even entering the Games allowed for anyone in your District to take tessarae without fear and without shame. By Volunteering, you told the entire District, “I have your back. I support you.”

And so, Neptune trained. She entered the Academy at a young age, fully prepared to lay down her life for the betterment of her community. After all, everyone died. If not of old age, then of the violence of the state. If not by the violence of the state, then the chaos of the ocean. If not the chaos of the ocean, then something else altogether - so what better way to let her community know they were loved than by offering herself to bring them the resources they needed? She felt comfortable killing; after all, the fish gave its life for her to feed her. The seaweed dried out in the sun made her fabrics. And every Victor that Four brought home came with it a District partner who had laid their life down for the community. All beings ceased eventually, so if it was by her hand, so be it. She could thank them for their aid, since every Tribute that died meant she was closer to enriching her entire District. What was 23 lives compared to the thousands back home?

Neptune trained for all of her youth in the Academy, perfecting weapons, staying fit, and maintaining her commitment to Four. However, it was simply never meant to be for her. Each cycle, a different pair was selected by the committee to represent the fishing District. And that was okay. That was part of all of it - serve her role as best she could until she was needed elsewhere. And at age 25, she graduated from the Academy and moved on to a different type of career. She returned to the coast to support her family - all fishermen. Her strength served her well on the boats out in the deep ocean, where the Akoyas fought big game like tuna and marlin.

Neptune found the love of her life on those boats: a fishmonger named Tetra. She was bookish and small, but gruff and hardheaded - the perfect balance to Neptune’s measured patience and grace. They met as Neptune brought fish to the market where Tetra was buying. She was the first person Neptune ever argued with, and from that moment she knew there was no one else who could rile her up that way. (At least, that’s the story Neptune told. Her family would disagree about the arguments).

For fifteen years, Neptune and Tetra built a life together. Hosting neighbors, attending to the home, keeping each other sharp and comfortable. Over the years, they did what they could to resist the Capitol, by shorting fish shipments, adjusting books to hide money away, by storing weapons on their fishing boat. But all beings came to an end. If not by old age, then by violence of the state. If not by the state, then by the chaos of the ocean. And sometimes, those lines were blurred.

Tetra had joined Neptune on a fishing voyage, as she often had over the years. A storm picked up, as it often did. And the boat capsized, as it sometimes does. What was odd, however, was the small explosion in the hull - where there was nothing that could explode. What was odd was the way neighbors seemed unable to reach them, even with their vessels designed for rescue. What was odd was Tetra, who could swim like the best of them, being too close to the blast when it happened. No one would be able to prove foul play, given the noise of the storm and the fact that the boat was now at the bottom of the ocean. But when Neptune was finally pulled onto a rescue craft, exhausted from trying to find Tetra, she knew in her heart that something was not right. Tetra’s body was never recovered.

All beings came to an end, as Neptune knew. But this event only spurred her on further, organizing and supporting the rebel cause. And then the announcement was made: the age restriction was to be lifted - and Neptune knew in her heart what she needed to do. There were young ones who felt prepared to go into the Arena, but that was not their fate. There would be other times for them. Neptune knew this was her chance to fully commit to the cause. Get in, win the Games, and bring back six months of prosperity to the District. After all, she had trained her entire life for this moment.

And all beings came to an end, anyway.

Trained, motivated, dedicated to the cause

Mellow, calculated, emotionally walled

Token: Tetra’s wedding ring

PENNED BY: M

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jenny Holzer, Selections from Truisms, Spectacolor Board, 20' x 40', Installation, Public Art Fund Inc., Times Square, New York, New York, 1982

#art#design#Jenny holzer#selections from truisms#truisms#slogan#sign#saying#billboard#digital billboard#installation#public art#public art fund#Times Square#New York#money creates taste#Spectacolor Board

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

selections from 'truisms' + 'the survival series' in jenny holzer - diane waldman (1989)

853 notes

·

View notes

Text

A friend of mine recently mentioned to me that someone has chastised them for being upset with someone who has a personality disorder for saying something hurtful to them. I don’t know the specifics and wouldn’t describe them if I did anyway, but a conversation followed about whether mentally ill people are responsible for their actions or not.

And leaving aside what everyone ELSE said about this, I’m realizing my answer is I’m not always sure.

It’s a tumblr truism that if a mentally ill person does a mean thing, they were “choosing to be an asshole,” and therefore are responsible. It’s described as if the illness stirs up a reaction in you, maybe an intense one, but you get a dialogue prompt in the game of Being You, where you get to choose to act on it or not. And if you did, you knew.

I’ve said before that I suspect the women in my family have narcissistic traits. My mom, my aunt, most notably my grandmother. I loved and still love my grandmother dearly, so this is not meant as “narcissists are unlovable and inhuman.” (Also, I’m AFAB and genetically related to these people. If I’m right that they have enough narcissistic traits to be an issue, then so, most likely, do I.) She was very smart, never let anything get in her way, and fiercely protective of me and others she loved. I don’t say this to claim she was devoid of love or completely horrible.

But! The woman was OBSESSED with how people saw her, how everything anyone said and did reflected on the family. She curled and dyed her hair well into her 90’s. It was the consistency, and the color, of straw. When she finally succumbed to dementia, one of the earliest signs was her going to a hair appointment… at 3am… and, finding the place closed, banging on the doors and screaming about how important her appointment was and how they simply had to attend her immediately until she was led away.

“It hurts to be beautiful” was her favorite saying. Any suggestion that beauty might be discardable, even temporarily, because one does not wish to be hurt, was written off as obviously foolish, maybe even crazy.

As her dementia advanced and her brain to mouth filter disintegrated, she began to comment incessantly on people around her who were ugly or fat. She went up to someone and berated him for choosing visible hearing aids rather than the subtle flesh toned kind.

My mom and aunt inherited her obsession with how things look, whether because personality is in part genetic or because she shamed it into them or both. Both have very aggressively shamed me over similar stuff, a lot. This is bad, and I don’t deserve it and neither did they from Grandma.

So the question of responsibility becomes, at least for me: what about that dialog box?

When my mom sees that I dress butch and is disgusted because I’m MEANT to be beautiful, or feels she’s failed at teaching me anything about adulthood because my floor isn’t swept, does she get that little break, that little pause, in the horror that is the thought someone will see my floor, and explicitly select “be an asshole?”

I find myself thinking not.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is difficult, being a moral paragon. When my friends invite me to go out to a spot of a certain marketing specialist-cum-restauranteur, I have to nip that particular Grey Gardens bud before it blooms, as it were. It's for their own protection. If they'll fall for that nihilistic old truism that "vibes increase the perceived value" and pay more to sit next to the retro 90's miami-chic flamingo mural while eating, they'll fall for anything. If they are with her in the belief she intimates that taking pot-shots from the comfort of your 2nd husband's money is the same as being a strong woman then, I'm sorry to say, it is kindest just to put them out of their misery. Sure, I want to "just be present with you", but I can sniff out when, over glasses of Special Selection BIODYNAMIC wine, the genuine humanity of the conversation has been overwhelmed by the therapy speak embedded in the substrate and drawn up by the cold of my presence.

0 notes

Text

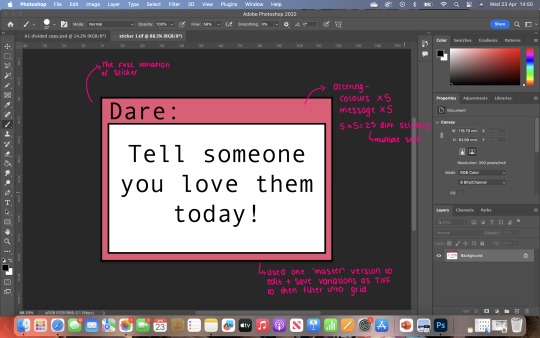

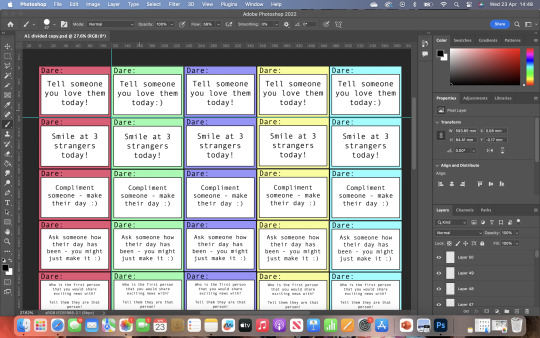

10.2) Sticker Making -

In this second part of the sticker making process I wanted to explain some of the choices that I made during this time and how I got to the results that I did. While I discussed a lot of the collaborative practice with technicians, I wanted to ensure I don't leave out the choices I made in this design stage.

After the session with Boris, learning about and creating the formatted stickers for printing, I had to ensure that the final designs of the stickers were completed, so that I could complete the document to print. Here is where I had to compare the different versions that I had printed and tested. It was mostly a choice of colour scheme selection, messages that I would display, the font styles and how I'd incorporate a QR code into the stickers. Because I was aiming for around 100 stickers I thought it ideal to make sure that there was a number of variations that all fit into that one hundred equally, so that I had an equal number of all the different stickers. I chose to have five different colours and five different messages, equalling 25 different variations of stickers (4 copies of the different variations, once printed). I went off of the colours that I had previously experimented with, blue, pink, green, yellow and purple. I think that these colours were appropriate as I knew that to use pastel versions of these colours, I will avoid them printing out too dark and dull, and they will still appear quite bright as they are a much paler anyways. Though this did seem like the best way to mitigate the risk of dull printing, I still wanted to make sure that the colour psychology made sense for the project. Because it was a positivity influenced idea it was quite important for me that each aspect of the project had intent to impact people positively, and something as simple as colour selection can have this effect. I discovered that psychologically, pastels shades are most commonly associated with; springtime, childhood, playfulness, optimism, serenity and laughter. I was pleased to read such positive and happy connotations of these colours, it reassured me that they were definitely appropriate for the project, it also felt as though it further enhanced this positive energy that is already woven into the stickers.

Here you can also see the experimenting with a new type face. I felt as though the original choice that I had selected, though working practically, it felt somehow very automated and in a sense quite robotic. I thought make to my truisms at the beginning of the project as I had tested with a few different type faces, and similar to this I wanted to have a bold font, this selection needed to feel slightly softer and less confrontational but still eye catching. I remembered the typewriter type face that I had used for my first set of truisms and I remembered at the time, enjoying the almost hand typed feel that this font had to it. Though it wasn't a handwritten styled serif font, it is still classed as a serif styled font.

Serif Fonts: Serif fonts typically have small extensions/strokes formed off of the main body of the letter. Typewriter fonts; typically have blunt formations that make it the serif style, these are typically known as 'slabs' which gave the type writer font the name "slab serif". The font is typically monospaced also, which means that each character occupies the same amount of space/width. I think this feature of the font used in my work in particular really helps with legibility as the characters are so evenly spaced.

I tested these two font against each other and I was still very conflicted between the two of them. I asked for various opinions around the studio as I know how important public feedback would be for my projects, especially from fellow creatives that understand audience focused design and know the motivations of my project, and we all came to the conclusion that this typewriter face had this slight edge on the original font that I'd tested with. It was agreed that this hand typed feel to it gave it a more personal, human touch to it which we agreed was quite important for a project that is based off of human emotion and interaction.

The last aspect of the whole design process was considering how I would weave the interactive aspect of the project into the designs. I had decided that i'd use a QR code with a link to some form of website so that people could leave feedback on the project, it was just where i'd place this QR code. While drawing onto the printed versions I roughly sketched having it on the physical sticker, however I feel as thought this simply overcrowded the sticker. I liked the idea of the stickers simply being these stand alone signs that are just there for people to observe and enjoy, the QR code aspect of it was simply so that I could measure whether or not the projects aims and objectives were successful, and to see how it does effect people. For this reason I thought that it may be best for the QR code to be separate from the main sticker but shown close by in the same art style, so that people were aware they were related, and had the option to approach the QR code should they want to learn more. Because the length of the messages on each of the stickers also varied (some with a significantly longer 'dare') it simply wouldn't cohesively fit onto the sticker. The dare message being the most important aspect, and so to shrink this size down to fit QR code on to the sticker, I felt, would take away from the focal point of the designs.

After these physical design decisions were made it was simply the case of making the different variations of stickers (5 different messages each in 5 different colours) and then filling out the pre-made grid with the preset sticker sized documents, ready to then print. This was a slightly lengthy process simply due to the fact that I had the original "master" document that I was editing and saving all of the new individual stickers from, into a new file of stickers. I worked in a process whereby I altered the text/dare first, and then changed the border colour, saving each copy individually. I did this process first so that I had all of the individual stickers saved and placed into a folder. I then started to fill in the grid with the stickers. I entered the stickers by columns of colour as I thought that this may make the printing process less complex.

Image 1 : Shows the file with each different variation of sticker, so each colour had 5 variations with the different messages on them.

Image 2: Shows the 'master' sticker which shows the first variation. This sticker would have been saved as a new copy in a TIFF format, into the sticker folder, leaving the 'master' document to be edited and for the process to repeated a further 25 times, to obtain all the versions of the stickers.

Image 3: Is a close up version of the grid that I filled out once all of the copies were saved into my sticker folder. You can see how all of the stickers could easily slot together as it was all measured up so that they could all fit into place neatly.

Image 4: This image shows the final document once completed. This had all of the variations of the stickers on and after some final improvements and adjustments with the formatting and columns, would then be ready to take to print!

After all of the stickers were in place I did just check over the document to ensure that all of the stickers were in line, as I know this would be a huge help one trimming all the stickers down to their individual states. I noticed that there were a few gaps and that some of the stickers not exactly parallel to one another, and so I tried to amend this as best as I could. After altering what I could see, I thought it best to get a second opinion from Boris, and so I forwarded the document to ensure that it was fit for printing, and the feedback was as followed:

It was very useful that as he updated and added the slight improvements to the document he updated and shared how to do this. It wasn't only helpful in the sense that it got me closer to having my stickers ready to print but throughout the whole process we were collaborating, he also taught me how to do the different processes that he did to get my work to that positioning. It introduced me to areas of photoshop that I had never previously used and functions that I didn't realise were so useful.

After this the stickers were ready to print and I went to collect them that afternoon. Boris was very kindly trimming the stickers all down to their individual sizes, and I was very happy with the result!! There was a slight printing error whereby on of the columns of the pink colour didn't print very successfully and I lost a few stickers this way, but aside from this technical fault I was very pleased. He informed me on the kind of vinyl that I was using and how, because it is so tightly wound an a roll, the stickers were very curled and that the next steps were to gradually press the stickers so that they flatten out and are then ready to use. He said this is best done by applying gradually increasing pressure in a warm room and leaving them under this pressure for an extended period of time. He said that if too high a pressure is placed on them straight away it can cause air bubbles between the vinyl and paper back which means it would start to lose its adhesive properties. I started off by separating the stickers into smaller piles as there was large bulk of them once stacked together. I then applied a small sized book on top of each and let it slowly flatten the stickers, not completely as I wanted to ensure the process was gradual. As time went on I started to apply larger heavier books over the different piles. I left them in front of my bedroom so that the sunlight would, hopefully, help in keeping them warm as they flatten out. I even moved them into the bathroom with me while showering so the steam, heat and pressure would help them flatten. I carried out this process over the course of a few days so that they were in the best state to be used and stuck up.

While I had the main stickers printed, I couldn't start sticking them up without the QR codes, as these were a crucial part in monitoring the project and its outcome. Instead of printing these sheets through Boris and the large scale printers in Parkside again, I thought that because of the scale, i'd only really need a sheet or two of A4, and so I should be able to use the printers in the school of art. I needed again, however, to see what materials would work with the main printers in the school of art, as this would also determine whether or not I'd have to use the printing rooms again. This is where I got in touch with the school of art based technician, Laura Gale, a senior photography technician who, I was advised, would know best when it comes to printing with these printers.

She quickly got back to me, and she had personally looked into kinds of sticker paper that she knew would comply with the printers in school of art. She had even attached links to the different kinds of papers that I could use. I looked into each of them and considered factors such as cost, appearance and the function of them. I would ideally like them to be vinyl as they'd match the stickers from Parkside, and I then know that all of the materials used can be recycled. Though vinyl isn't openly advertised as recyclable, it can be under the right circumstances, and so if I were to keep all of my materials in the same recycling bracket, it could make this aspect of the project much easier and safer. She had responded and said that they wouldn't print onto vinyl plastic, but there were vinyl based sticker sheets that have the same effect. She advised three different options that can be sourced on amazon. The first was a pack of preset sticker sheets that had existing squares for you to decorate/print onto. These looked suitable, however now that I knew how to create a grid preset on photoshop, I thought it better to work this way as there would be less paper wastage as I can create the document to completely fill the page, whereas these preset square stickers had gaps and spaces on the A4 sheets. The second material that she had advised were the Vinyl sticker sheets. These came with multiple plain sheets, and were vinyl based. These also claimed to be; suitable for outdoors, water resistant, easy to peel off, scratch resistant and can stick on to a wide range of different surfaces. These to me sounded like a very good option as they not only seemed as though they'd have a similar look to the main stickers, but they seem most suitable for the different locations where they'd be showcased. The last choice was a pack of transparent stickers, these had very similar qualities to the vinyl based sticker sheets however, they were transparent. I thought these did sound very cool, however, I had considered the design of the stickers and I wanted them to have a very obvious link to the main sticker design. And while transparent areas on the stickers sound very cool, I think it makes more sense to use stickers that would have a plain white background, like the main dare stickers. I also thought that If there were areas of transparency to the stickers, it may make them slightly camouflaged to the surface to which they are stuck on and leaves the potential of people not noticing them and therefore missing that opportunity for interaction. After assessing them all I felt that the second option would work best and so I double checked with Laura that these would be suitable, and I placed a next day delivery order. She reassured me that as long as the materials state they say laser printer, they should be fine to use in our printers. I organised to see her the following Friday (waited until I had the sheets) so that I could get the QR code stickers printed as soon as possible and ultimately start sticking the stickers up!

0 notes

Text

INFINITE COMBINATIONS

Parris Goebel is the choreographer of the moment. As dancers go she’s a polymath, drawing on references and techniques from as disparate sources as traditional Polynesian styles and hip-hop. One of her dances draws from the Siva Tau, a traditional Samoan war dance.

Hold that thought.

Multiple Nobel science prizes awarded last year went to researchers who required multi-disciplinary backgrounds to do what they did. The chemistry prize went to chemists who were really computer scientists. Stepping back from their achievement, we see that the three award winners relied on databases previously amassed by thousands of other chemists.

And…hold that thought, too.

In creative expressions of all sorts, we have always experienced news works inspired by unexpected sources, or at least sources that may not have captured mainstream attention yet. But in the era of instantaneous information distribution, we have finally arrived at a moment where a profoundly deeper ocean of ideas have the potential to be influential. The truism that artists should create based on what they know still holds true. To wit, Van Gogh painted a wheat field in motion because he saw wheat fields in motion in real life. It’s not a stretch to imagine a choreographer similarly inspired by similar sights. It’s also not a stretch to think that medical researchers might be inspired by what were once impossible inventions of science fiction. The point here is that ideas are no longer bound by time and space and opportunity. In fact, since you’re likely reading this on a hand-held device, you’re intimately aware of just how many ideas are pulling at your attention right now. Too many, most likely.

In the original Star Trek (shout out to fellow Trekkers!), the founder Gene Roddenberry floated an idealistic concept that largely shaped the moral center of the show. He called it “Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations”. As a physical object, presented in an episode called “In Truth is there no Beauty?” , the IDIC medal implied something that our future culture would value enough to serve as the basis for a high honor. As a story element the award never really caught on—we don’t see it again in the series (it was kind of a hokey clunker, if we’re being honest)—but as a narrative concept, it became the soul of something that continues to resonate for those who care to listen.

As a concept it’s also a surprisingly concise way of capturing the whole point. In fact, it’s prescient. Expertise in any discipline or skill demands focus and repetition and insight. Innovation requires expertise that has the wisdom to draw lessons from other disciplines. That requires not only an openness to otherness, but a curiosity and respect for otherness—infinite diversity in infinite combinations, in other words. This is, ironically, something that’s been happening automatically through genetic mixing for about two billions years. Genes, which are essentially just information coded into molecules, recombine. That recombination enables evolution, which is effectively the process where something new emerges from the stuff that already exists.

Taken as a weather vane for the future of innovation, the forecast looks exciting. With essentially limitless combinations, one can imagine untold discoveries in science, art, culture, and even political thought. But endless opportunity does not always enable endless innovation. More tools do not make a better artists. Let’s also not pretend that the advent of Artificial Generalized Intelligence presents serious risks to this process. (Next month’s blog discusses a key aspect of cultural transformation due to AGI. Mark your calendars!) The challenge is in being both selective and disciplined about how to approach creative work. Ideas by themselves will not generate great work. Everyone has a great idea for a movie, but most people never figure out how to do the monstrously hard work of making one. Simultaneously, we are now all capable of encountering the most esoteric information at all times, in just about any format and at just about any level of depth and complexity that we may want to pursue. We must make choices. Not everything possible is worth pursuing, but figuring out which unexpected pursuits might deliver something moving and meaningful is now a fundamental part of the process of making anything.

@michaelstarobin

facebook.com/1auglobalmedia

0 notes

Text

Jenny Holzer, Selection from Truisms

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

WORDY

The Guggenheim Museum is a notoriously difficult space for art. The most successful installations assert themselves sculpturally against the brazen and seductive forms of the architecture. An artist can't simply underestimate or obscure the Frank Lloyd Wright building.

Jenny Holzer's new exhibit Light Line updates her famous 1989 installation Untitled (Selections from Truisms, Inflammatory Essays, The Living Series, The Survival Series, Under a Rock, Laments, and Child Text), hanging scrolling electronic panels on the inner rotunda walls. The cool, dazzling text graphics with her iconic high-art "haiku" spiral upwards, pulsing like a stock ticker or electrocardiograph, speeded just enough to complicate legibility.

Some of Holzer's physical works are displayed in the small galleries along the ramp. There are marble benches, plaques, and shards engraved with original text. There are canvases laminated with gold foil and FBI diagrams plotting military attacks. There are reproductions of papers from the January 6 hearings. And there are metal panels stamped with Donald Trump's presidential tweets. These pieces are swallowed by the spiraling, sloping architecture; they can't hold their own, they feel small and lusterless. And, curiously, about half the galleries are left empty. The museum has never felt so desolate.

The electronic text settles right into the building. Compare this to the chyron on cable news, that might present facts at odds with the program, or address an altogether different subject. At the Guggenheim there's nothing of substance for Holzer's words to rub up against. More substantial artworks, visible in the galleries beyond the scroll, would have offered contrast.

Holzer's writings in the 80's and 90's carried a twinge of menace and subversion. BE CAREFUL WHAT YOU WISH FOR. YOUR OLDEST FEARS ARE THE WORST ONES. They were platitudes and also the awful truth, not messaging one expected from fine art. Today they no longer surprise. One museum guest wore a tank top with ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE printed across the front, like a sports team logo.

Occasionally a line reaches a loopy kind of poetry. IN A DREAM YOU SAW A WAY TO SURVIVE AND YOU WERE FULL OF JOY. Others are as dull-witted as the platitudes they were intended to dislodge. RAISE BOYS AND GIRLS THE SAME WAY. TORTURE IS BARBARIC. But here Holzer's writings, especially the most recent, just don't resonate; they feel jumbled, aphasic, as if the electronics controlling the monitors are generating the sentences. They observe laws of syntax but resist logic. I WILL THINK MORE BEFORE I CANNOT. IF YOU BEHAVED NICELY THE COMMUNISTS WOULDN'T EXIST.

As we're bombarded by text via messaging and media, words have lost some primal explain, arouse, and denote. This exhibit makes that spectacularly apparent.

Jenny Holzer, Light Line, 2024. Photo courtesy of the Guggenheim Museum.

0 notes