#scottish national gallery of modern art

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Joseph Beuys: The Secret Block for a Secret Person in Ireland, Foreword by Nick Serota, Text by Caroline Tisdall, Museum of Modern Art Oxford, 1974 (Internet Archive here) [L'Arengario Studio Bibliografico, Cellatica (BS). Studio Bruno Tonini, Gussago (BS). Art: © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn]

Cover Art: Joseph Beuys, The Sun State, 1974 [MoMA, New York, NY] Typography: Peter Miller

Exhibitions: Museum of Modern Art Oxford, Oxford, April 7 – May 12, 1974; National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, June 6-30, 1974; Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), London, July 9 (10) – September 1, 1974; Municipal Gallery of Modern Art (then Hugh Lane Gallery), Dublin, September 25 – October 27, 1974; Arts Council Gallery, Belfast, November 6-30, 1974

#graphic design#art#drawing#visual writing#exhibition#catalogue#catalog#cover#joseph beuys#nick serota#caroline tisdall#museum of modern art oxford#scottish national gallery of modern art#ica london#municipal gallery of modern art#hugh lane gallery#arts council gallery#moma#the museum of modern art#1970s

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

#2493 gavid bowie chan#snapshots#50mm#original photography on tumblr#carl zeiss#scotland#edinburgh#Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art#summer#2023#naturecore#cozy aesthetic#travel

1 note

·

View note

Text

The White Drake. Joseph Crawhall. Scottish. 1895.

National Galleries of Scotland.

#Joseph crawhall#scotland#Scottish#scottish history#modern history#art#culture#1800s#national galleries of scotland#painting#animals in art#duck#ducks#birds#bird

835 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remedios Varo (1908-63) Encuentro, 1959 Oil on canvas.

#art#on display at the scottish national gallery of modern art#the first building not the second#the one called Modern One

1 note

·

View note

Text

SET FOUR - ROUND ONE - MATCH ONE

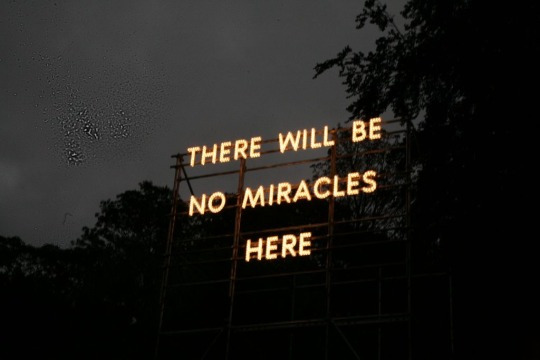

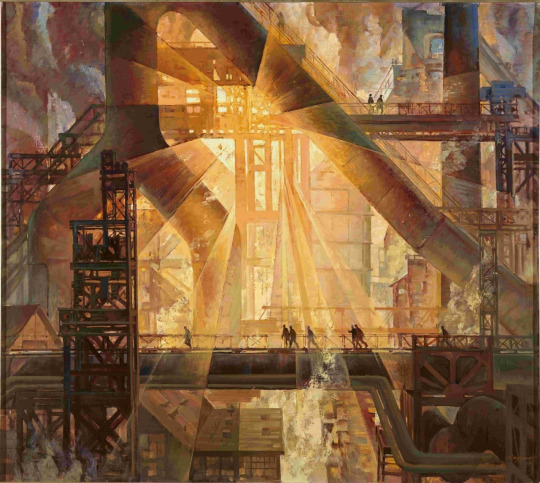

“There Will Be No Miracles Here” (2007-09 - Nathan Coley) / "Symphony of the Sixth Blast Furnace" (1979 - Evgeny Sedukhin)

THERE WILL BE NO MIRACLES HERE: This one’s a popular one. I’ve seen a lot of different pictures of it floating around online—these are just two of my favorites. It never fails to hit, though.

There will be no Miracles Here was (and possibly still is? I’m not sure if it’s still standing) a work of art that quoted, according to the National Galleries website, “a seventeenth-century royal proclamation made in a French town believed to have been the frequent site of miracles.” The site further says, “Coley’s practice is based in an interest in public space, and how systems of personal, social, religious and political belief structure our towns and cities, and thereby ourselves.”

It definitely makes me examine my social and political belief structure. Every time I see it I have to say the words slowly, feel them in my mouth: “There will be no miracles here.” It’s become, oddly enough, a litany for me. It’s a reminder, for me, that the only way out is through; that when I think I have no one else, I have myself. No one can save me but me. With every challenge I overcome, I say it to myself again: “There will be no miracles here.” It makes me feel scared and alone and proud to be alive, where I am. I’m here, in spite of the miracles, in spite of the lack of them. (@sherlockwatson)

SYMPHONY OF THE SIXTH BLAST FURNACE: The composition of the industrial machinery and the rays of artificial sun beaming through billowing steam set a glorious backdrop to the miniscule figures set in silhouette on the catwalks. Its as if this was painted just to remind you how small you are, set against the vastness of industry, and how beautiful it can be. (@lupinus-bicolor)

("There Will Be No Miracles Here" is an outdoor light installation by Scottish artist Nathan Coley. It is 6 m high and is on display at Scottish National Gallery Of Modern Art (Modern Two).

"Symphony of the Sixth Blast Furnace" is an oil on canvas painting by Soviet artist Evgeny Sedukhin.)

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

On March 7th 1924, Sir Eduardo Paolozzi, the renowned sculptor and artist, was born in Leith.

Eduardo Paolozzi was a prolific and inventive artist most known for his marriage of Surrealism's early principles with brave new elements of popular culture, modern machinery and technology.

The teenage Paolozzi was interned as an enemy alien. His father and grandfather were put on a ship to Canada and drowned when it was targeted by a German U-boat.

And with that his family life was deeply affected by the divisive nature of a country involved in conflict, which birthed his lifelong exploration into the many ways humans are influenced by external, uncontrollable forces. This exploration would come to inform a vast and various body of work that vacillated between the darker and lighter consequences of society's advancements and its so-called progress.

On the one hand, he would create abstract sculptures, which were dark and brutal in both material and form, portraying the idea of man as a mere assemblage of parts in an overall machine. On the other hand, he would create collages brighter in nature that reflected the way contemporary culture and mass media influenced individual identity. Some of these collages, with their appropriation of American advertising's look and feel would inspire the future Pop Art movement.

Paolozzi's early love of American culture and the collecting of its paraphernalia would lead him to make collages that were credited for launching the Pop art movement. He was the first to appropriate images from advertisements to create work representative of the shinier, happier lifestyles that were touted in American magazines and media.

Paolozzi was knighted in 1989 and by the end of his life was one of the country’s best-known artists. He died in April 2005 and left a major bequest to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. His works are now presented in a designated Paolozzi Studio in Modern Two, recreating the chaos of Paolozzi’s own workspaces.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Héré de Mallet

Mackintosh watercolour 1925 Private Collection on loan to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Attribution: Agnes Miller Parker (Scottish, 1895-1980). The Challenge, 1934, wood engraving on paper, 14.20 x 16.40 cm (paper 17.80 x 21 cm). Collection of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art @natgalleriessco. Thanks to @enchantedbooklet for the tip.

#gato#cat#katze#kat#katt#feline#wood engraving#printmaking#printmaker#scottish artist#cats in art#animals in art#gatto#gatto selvatico#chat sauvage#gato salvaje#Wilde katze

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul Klee

Ghost of a Genius, 1922

Oil and watercolor on paper laid on card

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marion Adnams, Aftermath, 1946

© John Rooks

Scottish National Gallery Of Modern

Art

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Luca Giordano, 1632-1705

Adam and Eve expelled by the Angel (Sketch), n/d, pen and black ink, over red chalk on paper. 19.20x19.70 cm

Scottish National Gallery Of Modern Art, Inv. RSA 310

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dog on Steps by Charles Reid(1837 - 1929). Scottish.

National Galleries of Scotland.

#national galleries of scotland#Charles Reid#photography#art#culture#history#modern history#animals in art#dog#dogs#scottish#Scotland#scottish history

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andy Warhol (US, 1928 - 1987)

Trash cans, 1986. 4 gelatin silver print photographs, on paper and thread support: 69 x 54 cm

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art exhibition

https://artblart.com/tag/andy-warhol-venus-in-shell/

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

RAQIB SHAW, “Self-portrait with fireflies and faces”, 2016.

Acrylic liner, enamel and rhinestones on paper mounted on cardboard 81.00 x 61.00 x 7.00 cm (framed size)

Scottish National Gallery Of Modern Art

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ELIZABETH BLACKADDER - Flowers, Oil on canvas.

Dame Elizabeth Violet Blackadder, Mrs Houston, (born 1931) is a Scottish painter and printmaker. She is the first woman to be elected to both the Royal Scottish Academy and the Royal Academy.In 1962 she began teaching at Edinburgh College of Art where she continued until her retirement in 1986.

Blackadder worked in a variety of media such as oil paints, watercolour, drawing and printmaking. In her still life paintings and drawings, she considers space between objects carefully. She also paints portraits and landscapes but her later work contains mainly her cats and flowers with extreme detail. Her work can be seen at the Tate Gallery, the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and has appeared on a series of Royal Mail stamps. Tate.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

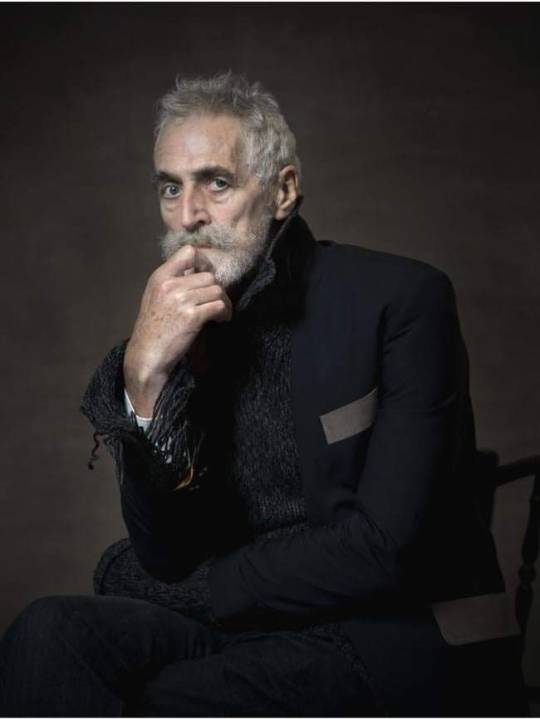

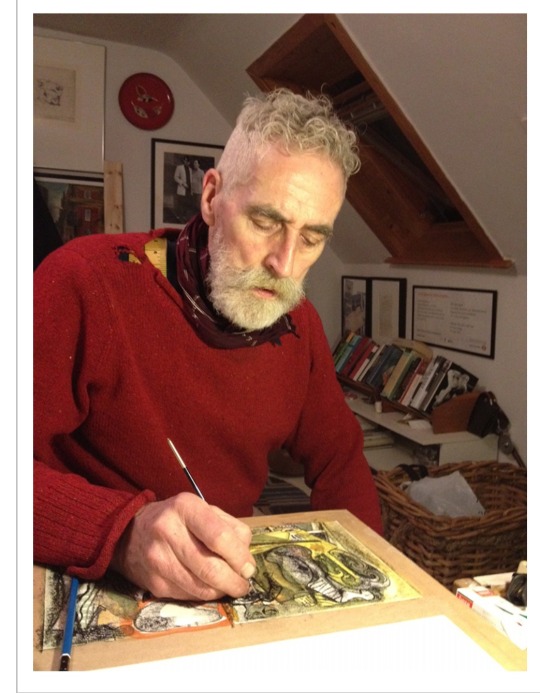

Scottish Playwright, writer and Artist John Patrick Byrne was on January 6th 1940 in Paisley.

John Byrne where he grew up in the Ferguslie Park housing scheme and was educated at the town’s St Mirin’s Academy before attending Glasgow School of Art, where he excelled. In his final year he was awarded the Bellahousten Award, the school’s most prestigious painting prize, and spent six months in Italy, returning a masterful and confident young artist. His work is held in major collections in Scotland and abroad.

Several of his paintings have hang in The Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh, the Museum of Modern Art and the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow. In 2007 he was made a full member of the Royal Scottish Academy and is an Honorary Fellow of the GSA, the RIAS, an Honorary Member of the RGI and has Honorary Doctorates from the universities of Paisley, Glasgow, Aberdeen and Strathclyde.

It was by no means an overnight success for Byrne, he was making a living designing book covers for publishers Penguin before recognition, Byrne has also designed record covers for Donovan, The Beatles, Gerry Rafferty, Billy Connolly, and The Humblebums as well as illustrations for the renowned Scottish writer James Kelman.

As well as his artwork Byrne was an accomplished writer perhaps best known as the writer of The Slab Boys Trilogy of plays which explore working-class life in Scotland, and of the excellent TV dramas Tutti Frutti and Your Cheating Heart.

In 2018 Byrne was named Scotland’s most stylish man at the age of 78 at the Scottish Style Awards in Glasgow, beating Outlander star Sam Heughan to the coveted most stylish male title, which was previously won by Richard Jobson, Robert Carlyle, James McAvoy and Paolo Nutini. Byrne, a good friend of comic, Billy Connolly Byrne said at the time he was shocked at the award saying “I dress like a tramp”.

The highlights the quintessential Scottishness of Byrne’s work, and his enduring humour and his focus on the frailty of human experience often lived on the edge of working-class communities. It is a richly rewarding show which underscores r give John Byrne a rightful place as one of Scotland’s finest and most prolific artists.

His most recent work has been murals - one for the ceiling of the King's Theatre in Edinburgh and another in Glasgow to mark the 75th birthday of his friend Billy Connolly.

During lockdown he worked with Pitlochry Festival Theatre to create a new play which was produced and performed remotely.

He and his wife Jeanine also collaborated on a children's book, Donald and Benoit.

Everything he did was drenched in colour. Without him, the world feels a less colourful place.

John Byrne passed away on Thursday November 30th aged 83.

Everything he did was drenched in colour. Without him, Scotland and the world feels a less colourful place.

41 notes

·

View notes