#roman britain time travel story

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Stones of Memory

Here is my entry for the 2024 Inklings Challenge. The @inklings-challenge is an annual writing challenge for sci-fi and fantasy writers, using certain subgenres and themes.

This story is a sequel to a short story I wrote many years ago. That story is referenced in this story, but I tried to make it readable on its own, as a standalone story.

********

I wrestle my huge suitcase through the narrow door of Aunt Alice’s little house. Do they make things smaller in England?

I pause in the familiar entry, breathing in the sights and smells I’ve missed since last year. Aunt Alice’s house is stuffed to the brim with oddities and artifacts. Shelves and tables and walls are lined with interesting things. I could spend hours looking at them.

But Aunt Alice is behind me, laughing at me, holding my other bags. She’s waiting for me to move.

I drag my suitcase into the sitting room and resume my goggling. I examine old photographs, ancient weapons, cracked vases, and worn tapestries. There are so many things to see! Clocks and seashells and lamps. And there’s a story behind each one. I ask Aunt Alice about them as we make our tea, and she tells me fascinating tales. The stories of how she came to own these things are almost as interesting as the stories of the objects themselves.

Aunt Alice is a little odd at times, but I’ve grown to like her eccentricities. Her wardrobe is interesting, for one. I can never decide what I think of it. Today, she’s wearing a blouse with metallic embroidery and a swirl of bright colors on an orange background. It brings out the reddish tones in her short, dyed hair.

After tea, I begin to help Aunt Alice wash up, but she says, “Run along and take a walk before the light goes. I can take care of the dishes.”

So I do. I step out the back door into the golden evening light. Only a swelling hill and a stand of trees separate the little cottage from the sea. I smell the salt on the fresh breeze. I take the path through the trees, climb the low hill, and emerge on the crest of it. Below me, there’s a shallow bay with a sandy shore, and beyond it, the sea.

A strange memory washes over me. I walked here many times on my visit to Aunt Alice last year. But the first time was the oddest. Something bizarre happened to me when I stood on this shore. I’ve almost forgotten it until now—because it seems almost like a dream.

When I arrived at this spot last year, I found a metal cloak pin in the grass by the shore. When I touched it, I had a vision of an ancient village, a painted ship, and an attack by Vikings. I shudder now at the thought of the Vikings chasing me. It was so real. It happened to me as if I was really there.

If I didn’t know better, I’d say I traveled back in time.

I shake away the strange sense of déjà vu. Today, there is only the empty shore, with gentle waves on the sand and rough grasses ruffled by the cool breeze.

It couldn’t be more natural. There are no Vikings to be seen—and perhaps there never were.

***

The next day, Aunt Alice and I are on the road, traveling in her battered, ancient station wagon. It’s still strange to me to drive on the wrong side of the road, but I’m no longer afraid that another car will crash into us.

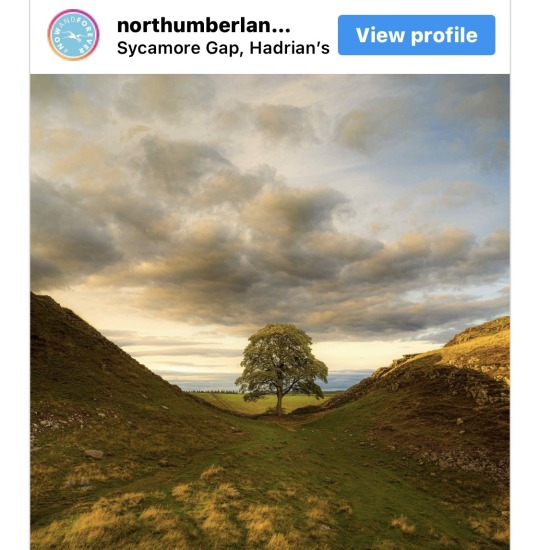

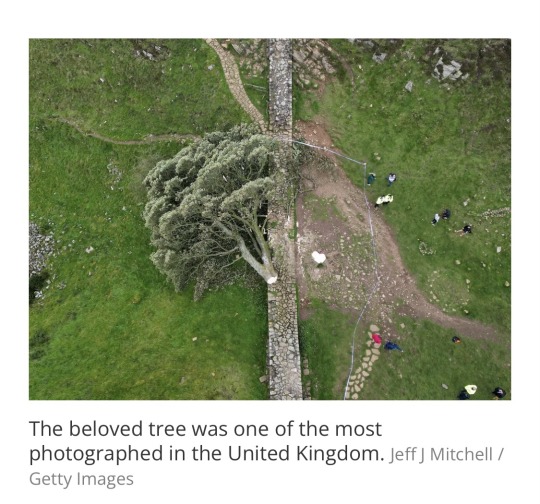

We’re headed to the site of a Roman fort on Hadrian’s Wall—or what remains of one. It’s amazing to me, an American, that something so old could survive for two thousand years, even in ruins. Perhaps that’s what attracted Aunt Alice to Britain. It’s hard to escape history when I’m in the company of my aunt.

The station wagon rattles bravely up and down green hills and around curves, swooping into valleys and over ridges. As we mount one more hill, Aunt Alice lifts her hand and points. “There,” she says. “There’s the fort.” On a hillside ahead of us lies a stony gray grid—a Roman ruin. A few minutes later, we tumble out of the car and hike up to the fort. Then I’m standing on ancient stones for the first time. The crumbling Roman walls stretch in orderly lines and right angles beneath my feet. Only the foundations remain, but it’s enough. It takes my breath away to think that Roman soldiers once patrolled these walls, back when they were still new. These stones are so old, but they’re still here. There’s still a low foundation, knee high. It’s amazing that it’s survived this long.

Beyond the wall, the countryside stretches away, ridge upon ridge. Hadrian’s Wall connects to the fort on either end and follows a ridge line up and down, slashing across the land.

Aunt Alice is watching me with a little smile. “Well?” she asks. “What do you think?”

“It’s beautiful,” I say. No, it’s majestic.

Aunt Alice turns me loose to explore the fort while she goes on to inspect the walls—just as if she was the fort commander in Roman times.

I wander around the rim of the fort, outside the walls. Below the walls, the ground drops quickly away in a downward slope.

I can’t take my eyes off the view, and I’m not watching my feet. My foot catches on something hard in the turf beneath. I nearly trip. I bend down to see what it is. I pat the grass, and my hand meets something sharp and cold. I pick it up. It’s something made of rough metal, corroded by exposure. It’s as long as my hand is wide, and it fills my palm. The metal is shaped like an arch, with a sharp spike sticking out of it. It looks like a pin—a cloak pin?

I suddenly remember another cloak pin—the one I found a year ago that gave me a vision of Viking times. A thrill runs down my spine. This piece of metal could be only a few years old—or it could be centuries old. What if it’s a Roman cloak pin?

I’ll show it to Aunt Alice. She’ll know. I turn and begin walking back to the fort to find her.

I move too fast, and my head begins to spin. The ground feels unsteady under me. I stumble.

The whole world whirls around me like a merry-go-round. The fort, the countryside, and the sky above mingle together in one solid blur. I can’t feel my feet on the ground. I’m floating, out of touch with the world—except for the hard metal pin I clutch in my hand.

I feel my feet on solid earth once more. The world comes into focus again. But everything has changed.

Instead of a bare hillside with a ruined stone foundation, a high wall rises above me. The fort is no longer in ruins. A town spreads out below it. The slope is paved instead of grass-covered, and it’s crowded with low thatched buildings. The place is alive with people. They’re dressed strangely in checkered fabrics, draped and pinned at the shoulders. I look down and find that I’m dressed in the same fashion, in a straight garment of thick brown wool.

A horn sounds, and I turn around. A patrol of men on horseback rides toward me. People scatter to get out of the street, and I hurry to follow, after a moment of staring. The men are mounted soldiers with shields and rough leather armor. At their head rides a man in a blood-red tunic with metal plate armor and a red-crested helmet—a Roman centurion.

Chills run down my spine. I stare. Could it be? Is this real? This has happened to me once before, and it’s happening again. Just like before, I am in the middle of another time. Am I dreaming, or have I truly traveled back in time?

Someone jostles me in the crowd, and a child darts around me, chasing a scrawny dog. The smoke of cookfires stings my nose, and a din of voices, human and animal, fills my ears. I finger the rough wool of the dress I am wearing.

It seems real. No dream could be so alive.

Then I feel the pinch of hard metal in my other hand, clenched in my fist. I lift my hand and open my fingers. The metal pin is still in my hand. But it’s no longer dull gray, roughened by the years. It’s shiny and new, shaped in a smooth curve. There’s a red jewel at one end of it that wasn’t there before. The same thing happened with that other pin—the one that took me to Viking times. Maybe it’s proof—proof that this is real.

The cavalry detachment disappears through a gate in the high wall of the fort. Dazed, I drift along with the crowd as they follow the departing horses.

A woman’s voice snaps at me. “Girl, what are you doing?” I look down and find I’m almost stepping on a flock of squawking chickens. I hastily move away.

There are so many things to see here. A woman spins with spindle and distaff in the doorway of a hut, with a baby on the ground beside her. Off-duty soldiers duck into the door of a wine-shop. A hunter carrying a spear walks past with a wolf-skin slung over his shoulder. He wears a shining neck-ring and a magnificent cloak pin.

As I keep walking down the street between rows of huts, I look down at the pin in my hand. I think this bow-shaped cloak pin is called a fibula—and it’s Roman, not British. The gem embedded in one end of it might be carnelian, or perhaps only glass, but it’s probably not a ruby.

I stare at it in wonder. Once before, a cloak pin took me to another world—another time—the time of the Vikings. Now I’m here, in a bustling Roman fort—holding a second cloak pin. It’s strange but somehow fitting. But what kind of power could do that? Time travel is the stuff of fiction.

“You, girl!” a sharp voice shouts. A man is marching toward me, dressed in Roman armor and carrying a spear in one hand, with a crested helmet under one arm—a centurion. I look up, startled.

“What do you have there?” the soldier demands in an accusing tone. He’s pointing at the cloak pin in my hand. Instinctively, I close my hand and clutch the pin to my waist.

“You stole that fibula. It’s not yours,” the centurion guesses. Other people are looking now. A few of them approach.

I open my mouth to protest. “No, I—” But only a whisper comes out. I back away, hemmed in by accusing eyes

“Take her to the magistrate!” someone says. The centurion beckons another Roman soldier, and they close in on me.

I look around for help, but there is none.

“She looks daft,” a woman says. “Look at her eyes. See, she doesn’t understand.” But I understand. The vacant look in my eyes turns to panic.

The soldiers reach out to lay hands on me. I shake them off. I turn and run, bursting through the crowd. The soldiers weren’t expecting me to put up a fight. They run after me and give chase.

My feet pound down the cobblestone street. I don’t know where I’m going. All I can think of is to get away—somewhere they won’t find me. I turn sharply to dash down a narrow side street between two thatched huts.

The Romans are still behind me, chasing me. They follow as I dash down a maze of narrow, zigzagging alleyways.

Once I leave the main thoroughfare, the streets are quieter, but they have no order. Living huts are tangled together with taverns and shops. A cat startles and flees at my approach, shrieking.

The heavy, nailed sandals of the Romans ring on the street behind me. Where can I go?

Just then, someone pops out of the doorway of a hut—a stout older woman. “Come—hide!” she says.

That’s all the invitation I need. I veer out of the street and dive through the low doorway of the woman’s hut. I press myself against the wall beside the door, ducking to avoid the low ceiling. A moment later, the soldiers barrel past with pounding feet. I’m safe—for now.

“They’ll be back,” the woman says knowingly. I turn to look at her. “Come. In here.” She ushers me to a curtain that partitions off half the hut. We duck behind the curtain, and it falls behind us. “If they come,” says the woman, “hide under the blanket.” She gestures to a low bed covered in skins and woven rugs in faded colors.

The whole place smells unpleasant, and the blankets smell worse, but I’m too desperate to care. I smile and nod gratefully. I collapse and sit on the bed at the woman’s urging. Only then do I notice how exhausted I am. I’m still breathing hard from my run, and my limbs feel like jelly. This does not feel like a dream.

The woman disappears for a few moments and comes back with a hot, fragrant bowl of meaty stew. I taste it, and it is rich and good. I wonder if I’d still like it if I knew what was in it—but I’m hungry as well as tired, and I eat it anyway.

A commotion outside sends the woman scurrying back through the curtains. Men’s raised voices reach me, hardly muffled by the curtain. The soldiers. I put down the bowl of stew, suddenly terrified. My insides feel frozen, and I can’t stomach more food at a time like this.

I feel the hard cloak pin in my sweating hand. I keep forgetting it’s there. I should probably hide it, but I can’t bear to let go of it. It seems like my only lifeline to reality and sanity, to my own world—my own time.

The novelty of this adventure has worn off. Maybe later I’ll appreciate it. Right now, I just want to go home.

I screw my eyes shut against the voices at the outer door of the hut. Any moment now, the soldiers will barge in to search the place, and I’ll have to hide under the blankets—as if that will be enough to keep them from finding me.

Then I realize—it’s quiet. The soldiers are gone.

The woman appears through the curtains, and I jump. But she reassures me: “They're gone.” Her shrewd look tells me she’s done this before. “Wait a little. Then you can go.” I try to tell her how grateful I am, but she waves me away. A few minutes later, I step out of the hut and breathe the fresh air again. I’m so happy to see the sky. The fort walls tower above me once more, with the town nestled at their feet.

I open my hand once more and look down at the cloak pin. The red jewel glints up at me like a winking eye. I reach out with my other hand and touch it gently.

The world begins to spin around me again, whirling at a dizzying speed. Then everything slows, and the world is steady once more—and I’m back at the Roman ruins, in modern England. The sun streams down above low, crumbling walls. Tourists wander around the site with cameras and neon-colored jackets. I’m dressed in my windbreaker and jeans.

I look around in wonder. Did that really just happen? Did I travel back in time? Or was it all a dream? If it was a dream, then it’s happened twice now—and it was more than a daydream. It seemed real. But it couldn’t be. Things like that don’t just happen.

But then I feel hard, cold metal in my palm. I expect the metal will be dull and gray. But the cloak pin in my hand shines in the sun, polished and new. The red gem bursts with color in the sun. That jewel wasn’t there before. Maybe—just maybe—this really did happen.

Someone calls out to me. It’s Aunt Alice. I turn and look for her as she comes toward me, carrying her outlandish, mammoth handbag. “Come up and see the walls,” she says. I’m still dazed, but I nod vaguely and start toward her, swaying a little. Aunt Alice looks hard at me. “What’s happened to you, my girl? Has history changed you?” She’s joking, with a twinkle in her eye. But she’s right—it has changed me.

“You’ll never believe me if I tell you,” I say.

Aunt Alice squints, studying me with a wise light in her eye. “I’m not so sure about that. Why don’t you try me?” I might do just that.

#inklingschallenge#team tolkien#genre: time travel#theme: comfort#story: complete#writing#my writing#writing challenge#writing prompts#roman britain time travel story#stones of memory#healerqueen

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

TL; DR: Saving Minrathous allows Neve to hope.

(Saving Treviso allows Lucanis to forgive, but that's another story for another day.)

***

Every companion in DATV hits a character crux during the game, but Neve's and Lucanis's characters -- being linked to the cities they love -- are especially interesting to me.

In particular I think Neve's character is a brilliant navigation of the issues the devs faced in representing the Tevinter Imperium. In previous games, Tevinter is an ancient shadow empire of blood mages and oligarchy; if Ferelden is roughly medieval Britain and Orlais is roughly medieval France, Tevinter is the remnants of the ancient Roman empire, with a hefty number of Nero-like rulers (sadistic, debauched, unchecked) still in residence.

So: how do you make that a place the player can root for? You write the story of the resistance. The anti-slavery Shadow Dragons make sense as Rook's allies, and their work is important. But Neve is how DATV tells the story of Tevinter's losers: the vast majority of regular people, who aren't mages or oligarchs or magisters, but still have to get by in this violent, corrupt place.

Neve has been manipulated and disappointed by institutions her whole life (like, let's be real, most poc and women and lqgbtq+ folks irl). She has enough privilege to protect herself: she's a mage born in a world that prizes magic. But she's not rich, and she's too fiercely ethical to take the shortcuts that would allow her to accumulate power. If you travel with her long enough, she'll tell you about the relatives who were only kind to her because they wanted to use her status as mage, and the uncle who was different. When she's in Lucanis's family home in Antiva, he complains about decorating, and she tells him her entire Minrathous apartment could fit in one room. Her clothes are well-tailored because she knows that looking good is a kind of power, but she'll explain to Bellara that it's not because she actually HAS rich patrons; she just dresses to look as if she might. She knows how to use the theater of wealth, but at the end of the day she's firmly working class, surviving off street food and bad coffee above a second-rate bookshop.

Neve loves Dock Town, sees how badly Tevinter's institutions have failed her community, and is deeply, fiercely protective of the weak and the vulnerable. If you drop a coin in a beggar's plate, she'll drop one too, and ask if they have shelter for the night. Hal insists he owes her free fish, but notice: every time, she says "Sure, next time, Hal," and pays him anyway. She knows he can't afford to give away business, but she'll never embarrass him by pointing this out. This is the same instinct that makes her so sweet to Bellara back at the Lighthouse: her elvhen fangirl is an open book, completely emotionally vulnerable, and Neve is immediately ready to look after her.

(It's also the instinct, I think that keeps her from confronting Rook about [redacted for spoilers] -- how terrifying would it be to fall for someone with that much of a blind spot?? But she's not going to kick Rook while they're down, and she can't help being drawn to them. Like, her fear is justified. It's not a great start to a relationship.)

But Neve is also a realist: she knows she CAN'T protect everyone, no matter how hard she fights. Over and over she's seen bad actors like Aelia slip through the cracks, and good guys like Brom (who ... maybe she had a thing for? some of her notes, idk) get killed trying to make it right. So when Rook meets Neve, this is the open question for her: CAN you make the world a better place? Can you illuminate the dark corners, and lift up the downtrodden, without compromising your own values? Or is it always already a hopeless proposition?

If Rook saves Treviso, and lets Minrathous burn, that's Neve's last straw. She stops looking. There's no way to be better than the Archon or the magisters, and so she'll join the Red Threads to beat them at their own game. Unlike Lucanis, she's still romanceable in this state, because ultimately she's still fighting for the things she loves; she just doesn't really believe in the future anymore. There's a pretty sad version of Neve's story in here, especially if you choose her to dismantle the wards in endgame. It's possible for her to lose everything she ever believed in. I've seen a lot of angry people complaining on the internet that her line at the end of her last companion quest -- "This is MY city now" -- is aggressive and cliché, but these people seem mainly to have saved Treviso and to not understand, as a result, how Neve's character is limited by the circumstances they've engineered. The complaint that her voice acting is hard, guarded, or flat is missing the point: her PERSONALITY is hard, guarded, and flat unless and until you help her believe that gentleness can be rewarded.

If you SAVE Minrathous, I think, Neve's character can have the most beautiful arc -- and her romance makes the most sense here, because as she begins to hope that her efforts in Dock Town might actually make a difference, she also begins to let her guard down. Both these things scare her shitless. Being visible (letting the citizens of Dock Town SEE her fight for them, letting Rook show her some risks are worth taking) is really scary. But if you save Minrathous, Neve begins to hope that there's a future for the soft, sweet, and vulnerable creatures of the world -- and that includes herself.

When her voice starts to crack in the later romance scenes, when her brow crinkles with anxiety and her eyes go wide and soft -- that's the reward for saving Minrathous. That's Neve Gallus with a future.

#neve gallus#datv#datv positive#dragon age the veilguard#dragon age#neve romance#character analysis#my art

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Looted Bronze Statue That May Depict Marcus Aurelius Is Returning to Turkey

The repatriation comes after years of legal disputes over the true identity and provenance of the 6-foot-4 artwork, which has been housed at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

A headless bronze statue that may depict the Roman emperor and philosopher Marcus Aurelius will be repatriated to Turkey after an investigation determined that it had been looted, smuggled and sold through a web of antiquities dealers before arriving at the Cleveland Museum of Art in 1986.

The Manhattan district attorney’s antiquities trafficking unit first identified and took possession of the looted statue in 2023. But the statue remained in Cleveland while the museum challenged the seizure.

Last week, the museum relented and agreed to return the statue to Turkey. According to a statement, “new scientific testing” had revealed that the second-century C.E. statue was “likely present” at the Sebasteion, a shrine near the ancient Roman settlement of Bubon.

“The New York district attorney approached us with a claim and evidence that we felt was not utterly persuasive,” William M. Griswold, the director of the Cleveland Museum of Art, tells the Art Newspaper’s Daniel Grant. Officials then requested scientific tests to determine the validity of the claim.

All parties agreed that the scientific investigation would be led by Ernst Pernicka, an archaeologist and chemist who serves as the senior director and managing director of the Curt-Engelhorn-Center for Archaeometry in Germany.

As Pernicka tells the Art Newspaper, his tests followed a “well-established scientific procedure,” which included soil samples, lead isotope analysis and 3D modeling of the shrine site. Soil from within the statue matched soils in Turkey, and lead at the foot of the statue matched lead residue on a stone base where it may have been attached at the Sebasteion. Investigators also traveled to nearby villages to conduct interviews with locals who remember the looting.

Per the New York Times’ Graham Bowley and Tom Mashberg, the story goes something like this: Built nearly 2,000 years ago, the shrine featured bronze statues of Roman emperors, including Lucius Verus, Valerian and Commodus. An earthquake later buried the site, which was discovered by farmers in the 1960s. Villagers plundered the shrine and sold the bronzes to antiquities dealers like Robert Hecht, who faced allegations of smuggling before his death in 2012. After covert restoration in Switzerland and Britain, the items were sold to collectors and museums around the world.

With the statue of Marcus Aurelius returning to Turkey, the antiquities trafficking unit has seized 15 items looted from Bubon, collectively valued at nearly $80 million, according to a statement.

Turkish officials are celebrating the news. In a social media post, Minister of Culture and Tourism Mehmet Nuri Ersoy lauded the efforts to return the statue “to its rightful land,” per a translation by Türkiye Today. He added, “History is beautiful in its rightful place, and we will preserve it.”

In a legal sense, the case is closed. But mysteries about the bronze remain. The most glaring question: Who does the headless statue really depict?

When the Cleveland Museum of Art bought the statue from the Edward H. Merrin Gallery for $1.85 million in 1986, the receipt said “figure of a draped emperor (probably Marcus Aurelius), Roman, late second century [C.E.], bronze,” according to the Times. Standing at 6-foot-4, even without a head, it’s now thought to be worth around $20 million.

n its statement, the museum claims to have made a “relatively recent determination” that the statue is an unnamed philosopher rather than Marcus Aurelius. One stone base at the Sebasteion is inscribed with the ruler’s name, but the tests revealed that the statue was likely positioned on a different stone base without an inscription.

“Without a head or identifying inscription, the identity of the statue remains uncertain,” the museum adds.

However, Turkish officials dispute the museum’s claims, suggesting that the statue does depict Marcus Aurelius—both an emperor and philosopher—and may have been moved around between plinths, per the Times.

For now, the mysterious statue remains in the Cleveland Museum of Art. As Griswold tells the Art Newspaper, “The Turkish authorities are prepared to consider permitting the work to remain here in Cleveland for a brief period, so that our visitors may say farewell to the sculpture and so that we may explain to the public some of what we’ve learned in this process.”

By Eli Wizevich.

#A Looted Bronze Statue That May Depict Marcus Aurelius Is Returning to Turkey#Cleveland Museum of Art#Bubon Turkey#bronze#bronze sculpture#bronze statue#looted#stolen art#ancient artifacts#archeology#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#roman art#ancient art

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

January 24th in the year 76 is the reputed birth date of Publius Aelius Hadrianus the greatest wall builder Scotland can call a friend. 😉

Although now entirely in England it is in what was often called, ‘The debatable land’ the areas around it having changed hands on many occasions, work started on the wall was built in 122AD and stood as the northern frontier of the Roman Empire for over two centuries.

It is thanks to Hadrian’s Wall that the land which became Scotland was first considered one territory. It’s also a fact that we know more about Hadrian than just about every King of the Scots until Malcolm Canmore who reigned almost 1000 years later, and the emperor who in a real sense created Scotland turned out to be a fascinating character.

Hadrian is known as one of the Five Good Emperors, the others being Nerva, Trajan, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius.

Hadrian’s family were from modern-day Spain and he may have been born there or in Rome in 76, as his father was the cousin of the previous Emperor Trajan, who looked after the boy when Hadrian’s father died when the future emperor was just nine.

I’ll skip the full story of his life and press on with the story of the wall.

Hadrian knew the east of the empire well, but not the far west. He travelled through Gaul to Britain and there he was told of the fierce barbarians to the north, so often portrayed on page and screen as savages, who frequently raided south deep into Roman Britain.

These “barbarians” were most likely the Picts who then occupied most of what is now Scotland.

As someone who commissioned or oversaw the building of bridges, aqueducts and temples and who made the Pantheon the greatest building in Rome – it survives largely intact even now – the solution to the northern problem was simple. He would keep out the barbarians, and thus ordered the construction of a wall right across the “waist” of Britain from Luguvalium to Coria, or Carlisle to Corbridge as we know them.

The story is told that he was informed that it couldn’t be done – Hadrian went to Eboracum (York) and supposedly drew up the first plans himself.

For the first time, the inhabitants of what we know as Scotland knew they had a southern limit – not that it stopped them invading anyway. It was 73 miles long and in places was up to 12 ft high and 20ft wide, with forts and fortlets spread out along the wall. It remains the largest Roman artefact still extant in the world.

So was it really the southern border of Scotland? Never officially called the border, the Wall still marked the extent of the Roman Empire with everything south being Roman Britain, especially after the Antonine Wall between the Clyde and Forth was abandoned only eight years after it was completed in 154. And the Romans did not leave until the 5th century.

So for centuries, everything north of Hadrian’s Wall was seen as the land of the barbarians, and that is why, when the land we know as England was invaded by the Angles, Saxon, Jutes, Danes and Norsemen, the peoples north of the Wall were left to their own devices.

It has been argued that no one has ever really “conquered” Scotland in that the country we think of as Scotland did not really come into being until the Picts and Scots joined together and later took back Strathclyde and the Lothians from the Britons and the Northumbrians respectively – it was only in 1018 that the Battle of Carham finally confirmed the land north of the Tweed on the east coast as part of Scotland. Various English kings claimed “overlordship” of Scotland, but the man who came closest to conquering this land was a commoner, Oliver Cromwell, and even he left alone the far north and the Hebridean islands.

Hadrian died in 138, having defined the limits of the Roman Empire in the West, limits that did not include Scotland, and we should be grateful to him, for it took a man of genius to realise that the people of this land are different from those south of his Wall.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fae of the British Lostbelt

This is gonna be a long one, so strap in.

The fae and other creatures of the British Lostbelt take heavy inspiration from real-life legends; almost every major character is named after a type of fairy or mystical creature from British folklore. Many of these names are not English; I've added a pronunciation guide for these in brackets after the word. In this post, I'll go over the beings and concepts these characters are named for and compare the legend to the original. This won't include Morgan or Oberon; those figures are complex enough to deserve posts of their own.

Aesc [ASH]

Aesc is more accurately spelled Æsc. It's an Old English word for the ash tree, and also doubles as the word for the rune for the letter Æ. This is pretty much a direct translation into Old English of Aesc's Japanese name, Tonelico (トネリコ), a word meaning "ash tree".

Albion

Albion is a poetic name for the island of Britain, from Greek Albiōn (Ἀλβίων), the name used by classical geographers to describe an island believed to be Britain. The name probably means "white place", which is how it's connected to the Albion of Fate. The Albion of Fate is the White Dragon, a symbol of the Saxons from a Welsh legend. In the most well-known version of the legend, the King of the Britons at the time, Vortigern, was trying to build a castle on top of a hill in Wales to defend against the invading Saxons, but everything he tried to build collapsed. He was told by his court wizard to find a young boy with no father and sacrifice him atop the hill to alleviate the curse. He sent his soldiers out and found a boy being teased for being fatherless, but when he brought the boy to the hill, the boy, a young Merlin, told him that his court wizard was a fool and that the real reason for the collapsing castle was two dragons inside the hill, one red and one white, locked in battle. The red dragon represented the Britons, and the white dragon represented the Saxons. Merlin told Vortigern that nothing could be built on the hill until the red dragon killed the white one. A red dragon is the symbol of Wales to this day, and a white dragon is occasionally used in Welsh poetry to negatively represent England. This white dragon is Albion in Type/Moon lore.

Baobhan Sìth [bah-VAHN shee]

A baobhan sìth is a female fairy in Scottish folklore. The name literally means "fairy woman" in Scottish Gaelic. They appear as a beautiful woman and seduce hunters traveling late at night so that they can kill and eat them, or drink their blood depending on the story. They're unrelated to banshees except in terms of etymology (Banshee is from Old Irish "ben síde", meaning the same thing as baobhan sìth). They're often depicted with deer hooves instead of feet, which is probably what inspired Baobhan Sìth's love of shoes.

Barghest

In the folklore of Northern England, a barghest is a monstrous black dog with fiery eyes teeth and claws the size of a bear's. The name probably derives from "burh-ghest", or "town-ghost". It was often said to appear as an omen of death, and was followed by the sound of rattling chains. The rattling chains probably inspired Barghest's chains. Her fire powers are also obviously based on the fiery eyes of the barghest. Otherwise, she's not very connected to the folkloric barghest, which is never associated with hunger or eating humans.

Boggart

In English folklore, a boggart is either a malevolent household spirit or a malevolent creature inhabiting a field, a marsh, a hill, a forest clearing, etc. The term is related to the terms bugbear and bogeyman, all originally from Middle English bugge, or possibly Welsh bwg [BOOG] or bwca [BOO-cuh], all words for a goblin-like monster. It usually resembled a satyr. It's not really ever depicted with lion features, so it's anyone's guess why Boggart is a lion-man.

Cernunnos [ker-NOON-ahs]

Cernunnos, probably meaning "horned one", was an important pre-Roman Celtic god. His existence is only attested by fragmentary inscriptions and the repeated motif in Celtic religious art of a "horned god", a humanoid figure with deer antlers seated cross-legged. This fragmentary evidence is often led to assume that Cernunnos was a god of nature, wilderness, animals and fertility. There exists no evidence that Cernunnos was a chief deity of any kind, since we have barely any evidence he existed at all in the first place. Cernunnos might not even be his name; it's just the only name we have. Needless to say, the only thing the Cernunnos in the British Lostbelt has in common with the real figure is his large antlers.

Cnoc na Riabh [kuh-nock-nuh-REE-uh]

Cnoc na Riabh, Knocknarea in English, is a hill in Sligo in Ireland. The name means "hill of the stripes", referring to its striking limestone cliffs. It's said to be the location where Medb's tomb lies, so it's connected to Cnoc na Riabh through Fate's conflation of Medb with Queen Mab, a fairy mentioned in Romeo and Juliet; this etymology of Mab as derived from Medb was formerly accepted, but has lost favour with the advent of modern Celtic studies due to the lack of any concrete connection between the two figures.

Grímr (don't know how to say this one, apologies; Germanic myth is not my strong suit)

Odin (Wōden in Old English) was a god worshiped in many places, basically anywhere the Germanic peoples went, including the Anglo-Saxons that became today's English people. As such a widely worshiped god, he had a very large number of names, titles and epithets. Grímr is one such name, literally meaning "mask", referring to Odin's frequent usage of disguises in myths, which is fitting for how Cú disguised himself as a faerie in the British Lostbelt and hid that he possessed Odin's Divinity from Chaldea.

Habetrot

Habetrot is a figure from Northern England and the Scottish Lowlands, depicted as a disfigured elderly woman who sewed for a living and lived underground with other disfigured spinsters. She often spun wedding gowns for brides. Cloth spun by her was said to have curative and apotropaic properties. All the Habetrot of the British Lostbelt has in common with this figure is the association with brides and with spinning cloth. "Totorot" is not a real figure; the name is just an obvious tweak of Habetrot.

Mélusine

Mélusine is a figure that appears in folklore all across Europe. The name probably derives from Latin "melus", meaning "pleasant". She's a female spirit of water with the body of a beautiful woman from the waist up, and the body of a serpent or a fish from the waist down. In most stories, she falls in love with a human man and bears his children, using magic to conceal her inhuman nature. However, she tells her lover he must never look upon her when she is bathing or giving birth. Of course, he invariably does so, and when he does, he discovers her serpentine lower body, and she leaves, taking their children with her. Since Mélusine is just the name Aurora gave her, the Mélusine of the British Lostbelt has very little to do with this figure, but an analogy can be drawn between the Mélusine of folklore hiding her true form as a half-serpent to maintain her relationship with her lover, and Fate's Mélusine suppressing her true form as both a dragon and an undifferentiated mass of cells to ensure Aurora continues to love her.

Muryan [MUR-yan]

A muryan is a rather obscure Cornish fairy. The word is Cornish for "ant". Muryans are diminutive figures with shapechanging abilities, cursed to grow smaller every time they use those abilities until they eventually vanish altogether. Muryan, of course, is connected to muryans through her ability to shrink others.

Spriggan [SPRID-jan]

A spriggan is a type of creature in Cornish folklore. The word is derived from the Cornish word "spyryjyon" [same pronunciation], the plural of "spyrys", meaning "fairy". They're usually grotesque old men with incredible strength and incredibly malicious dispositions, and are often depicted guarding buried treasure. Spriggan is not himself a faerie, and the name is stolen from a faerie he killed, but it's still appropriate due to the greed and selfishness spriggans are usually depicted with.

Woodwose

Woodwose is a Middle English term for the wild man, a motif in European art comparable to the satyr or faun. The etymology is unclear. It has little to do with wolves or animals, despite its association with wildness, but there is at least a thematic connection with Woodwose's character, since the archetype of the wild man depicts a figure who cannot be civilised or well-mannered no matter how hard he tries, much like how Woodwose barely restrains his temper by being a vegetarian and dressing in a fine suit. Woodwose's predecessor, Wryneck, is named for a type of woodpecker with the ability to rotate its neck almost 180°.

#incoherent rambling#fate grand order#fgo#lostbelt 6#avalon le fae#boggart fate#woodwose fate#habetrot#spriggan fate#muryan#melusine#baobhan sith#cernunnos#barghest#cnoc na riabh#fateposting#if i missed anyone in this post OR in the tags i will jump off a cliff#now it is bedtime#will probably give morgan and oberon their own posts in a few days#school. you know.

338 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Chronicles of Professor Chronomier

Before Season 6 launches later this autumn, I wanted to shout about my beloved Professor, in the hope more ears can find her and fall in love with her.

The Chronicles of Professor Chronomier follow the time traveling adventures of Victorian explorer and inventor, Elizabeth Chronomier in an audiobook format, where I narrate and perform every character.

Each season is loosely inspired by a literary genre, and there's plenty of plot twists and a wonderfully crafted story arc by Dario Knight.

S1 - The Tudor Assassin, adventure calls in Elizabethan London. S2 - Temper and Temporality a romance, (with hints of gothic) during the lost years of Jane Austen. S3 - The Cottage on the Moor - dystopian future. S4 - From the Depths - a crime noir with Oscar Wilde. S5 - Goddess of Victory - a tragedy of revenge in Roman Britain.

In between each season, there is also a standalone extended episode.

If you like:

ADVENTURE LITERATURE QUICK WITTED QUEER HEROINE VICTORIANA MAYBE A BIT OF STEAMPUNK INDIANA JONES DOCTOR WHO EMOTIONAL ROLLERCOASTERS COCKNEY SIDEKICK BITESIZE EPISODES ERIKA SANDERSON DOING A LOT OF ACCENTS

#audio drama#fiction podcast#podcast#queer#queer fiction#queer podcast#unbound theatre#the chronicles of professor chronomier#elizabeth chronomier#time travel#Victoriana

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

As Frankie continued to complain to Lesley about her troubles, neither of them noticed the young woman stepping out of the sea towards them.

"Greetings, Lesley. Greetings, Frances. Beautiful sunset, is it not?" asked Nalani.

"Eurgh, where'd she come from..." grumbled Lesley under her breath.

"My day hasn't been crap enough, so the Watcher sent her for a visit," whispered back Frankie.

Both of them gave Nalani small smiles in acknowledgement of her greeting. Nalani was another shell trader. Unlike them, her business was incredibly successful as she often had the rarest and most beautiful shells and treasures on offer.

Whenever Frankie had asked her how she got her hands on them, she would smile sweetly and refuse to answer, instead making cryptic comments like 'I am one with the sea'. This rubbed Frankie up the wrong way: while she understood Nalani's desire to protect her business secrets, Frankie also felt that a certain level of comradery and support was only reasonable.

Nalani settled into the sand beside them, "I do most enjoy watching the breeze blowing through the palm trees. It is difficult to observe from below the water's surface."

"Yeah..." replied Lesley and Frankie non-committally.

"Frankie, I am surprised to see you here. I was led to believe that you had relinquished your stall in order to trade goods in far off ports?"

"Yes... it's a long story. But I'll be back out on the sea soon," explained Frankie.

Nalani looked at Frankie with a kind intensity that unsettled her, "I am glad to hear it. I know how fond you are of the sea - perhaps as much as am I. Though, I too wish I could travel out beyond the seas of Sulani."

"Frankie and I were just talking about how to get started in the trade business. I would've thought you had enough from selling your treasures to buy some stock and start selling?" suggested Lesley.

Nalani bowed her head slightly, "It is not the cost that prevents me from pursuing such plans."

Frankie and Lesley exchanged side glances, trying to decide whether to pursue the conversation further by asking for more detail. As the silence stretched out, Frankie began to feel guilty and asked, "What does prevent you?"

Nalani gave the same mysterious smile that she always gave when Frankie asked about her treasures and replied, "I one with the islands as much as I am one with the sea. Good evening, ladies."

As Nalani walked away, Lesley and Frankie watched the way she moved with a purposeful beauty and then dropped back onto the sand with frustrated grunts.

"I don't consider myself a violent person, but every time I speak to her, I'm filled with the urge to hit something," grumbled Lesley.

Frankie sniggered, "an understandable impulse. Come on, let's go get a drink."

Start (Iron Age) | Start (Roman Britain) | Start (Anglo Saxon) | Start (Medieval) | Start (Tudor) | Start (Stuart)

Previous | Next

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Wedding Night Of River Song

Doctor Who » Eleven x River

Title: The Wedding Night Of River Song

Author: fairytalesandfolklore

Fandom: Doctor Who (Masterlist)

Relationship: The Eleventh Doctor x River Song

AO3 Rating: Mature (a complete collection of author's notes, inspiration credits, content warnings and tags can be found on AO3)

Summary: When the Doctor promises Melody Pond a whirlwind adventure, the last thing she expects is to spend her night standing guard while he visits another woman — his wife. Little does she know it's herself from the future. That's the trouble with time-travelers. Word of advice: Never fall in love with a man from the stars. Especially one you're meant to murder.

"We've just been to one of the most beautiful planets the universe has to offer. We've seen volcanoes erupt in the distant mountaintops, with the comfort of knowing we can't be touched. We've climbed to the top of the tallest tower and danced in the rays of the setting Barcelonian sun," he whispered, pausing for a moment to release a short, breathless chuckle as he exchanged his smile for a look of pure longing. "And all I could think about was her." The words shot through Melody's heart like a dagger. "Doctor," she said, before she could stop herself. "Who is she? Why is she so special? And why tonight?" The Doctor's smile widened, and this time, he didn't miss a beat. "She's my wife, Mels, and this is our wedding night."

Read On AO3 | Read On Tumblr:

When Melody was a little girl, she had a best friend named Amelia Pond. Like most best friends, Amelia wasn't imaginary, she didn't have a mad appetite or a taste for peculiar attire, and she didn't make promises that she couldn't keep. On the day that Melody was born, Amelia promised her that she would be safe, that she would be brave, and that no matter where she was taken, her parents were coming to find her. That promise, Melody broke on her own, because she found them first. Only, she found them quite a bit earlier than she'd intended to.

The best thing about Melody's mum was her imagination: her head was full of mad, impossible stories, and she never grew tired of telling them. When they were both seven years old, Amelia told Melody about her imaginary friend: the man from the stars. A mad time-traveler who fell from the sky and crashed into her garden. A man who ate fish fingers and custard, and opened a crack in her bedroom wall that splintered off into the end of the universe. A man who promised her that he would take her traveling in his bigger-on-the-inside blue box. A man who made her wait for fourteen years before he finally stole her away.

She told Melody that she could remember adventures that had never happened, wonderful dreams of faraway planets and the future of Great Britain carried off on the back of a star whale. Of terrible creatures made of stone and reptilian women with fiery tempers. Of millions of spaceships lighting up the sky and nights without any stars at all. Once, she'd said, Rory Williams had been a Roman Centurion, and he had waited for her for two thousand years while she slept in Pandora's box. Mels had never laughed so hard in her life, trying to picture her awkward, gangly father in Roman garb.

Amy told Mels how wonderful the Doctor was, how he had lost his entire race to a terrible war, and still, he'd soldiered on. How, in all of his nine hundred and seven years, carrying with him all of that pain and misery and loneliness, he'd never once succumbed to violence if he didn't have to. How he'd saved thousands of civilizations, altered entire worlds by changing a single mind, and had even sacrificed himself to reboot the crumbling universe.

What Amy had neglected to tell Mels all those years ago was that the Doctor was, in fact, a cheeky bastard with appalling manners and very little common sense. On the eve of Melody's twenty-first birthday, a blue police box appeared outside of her window. She never questioned who he was, or why he had come for her. She simply stepped outside and into the blue box, and the mad man with the time machine took her to see the stars.

That night, they traveled to Barcelona, a beautiful planet with a temperament to match her own, with chains of active volcanoes surrounding its outskirts like a protective gate, golden skylines blanketing the towers of the inner cities, and beaches with white-hot sand and deep, violet oceans stretching to the edges of the planet's surface. Together, they ran back into the TARDIS, laughing breathlessly, their arms filled with enough Barcelonian chocolates and spirits to last Mels three lifetimes.

The Doctor set new coordinates, and Mels waited in anticipation for their next destination. Within seconds, the TARDIS had vworped to a halt, and Mels released a gust of air she hadn't realized she'd been holding. On the other side of those doors could've been anything at all in the entire universe. This was the adventure she'd been waiting for: for this man to come and take her away. To become more than fairy tale and legend. To rewrite time and make her his companion, rather than his assassin. Heart in her throat, Melody pushed open the TARDIS doors, and an ugly grimace spread across her face.

"Now, this can't be right," she said, stepping out of the comfort of the blue box and into a dimly lit, dark gray corridor. "Where are we?"

The Doctor smiled sheepishly as he climbed out of the TARDIS. He gently closed the doors with a semi-silent click, looking about the corridors cautiously, as though expecting an ambush at any moment. His eyes met Melody's and his face broke into a ridiculous grin.

"Stormcage Containment Facility," he whispered, a ruddy blush settling into his cheeks as he added, "Just popping in to visit a friend."

In every one of Amy's stories, the Doctor had always been confident, calculated and very, very brave, if a little mad. If Mels didn't know any better, she'd think she was staring at a giddy five-year-old in a man's body. The Doctor's true intent became evident as Mels observed his nervous laughter, the way he checked the corridors around them so often you'd think he had a tick, and the way he placed special emphasis on the word friend.

"You have got to be kidding me," she nearly shouted, her heart sinking into her stomach. The Doctor placed a finger to his lips and smiled somewhat apologetically.

"Won't take long, I promise. Well, alright, it might take long. Quite long, actually, as River does like to…anyway, I'll be back in a bit. Promise."

"And what exactly am I supposed to do while you go off for a random shag?" Mels asked, not bothering to keep her voice down in the slightest. His eyes traveled to the spare guard uniform hanging up on a hook on the opposite wall, and Melody's mouth dropped open in horror. Confounded by this man's inherent lack of social code, Mels leaned up against the cold, dark gray wall, crossed her arms, and shot him a murderous glare.

The Doctor said nothing, nervously scrubbing his fingers through his disheveled hair, his blush deepening. He seemed torn between pleading and pouting as he tentatively approached her, careful not to earn a well-deserved slap across the face. He casually slid up against the corridor wall beside her, leaned in close, and gently tucked a strand of her dark, curly brown hair behind her ear, his breath ghosting over her skin as he whispered, please.

She could feel his eyes on her, burning into her skin, willing her to look up at him, and for all of her rebellious charm, he was the one who could melt her resolve with a simple flash of his magnificent smile. She'd only just met him tonight, but she had spent years of her life hearing stories about him, wondering where he'd gone and if he would ever come back. In this moment, he was Amelia's dream, and Melody's reality.

There he stood, all tweed jacket, braces, boots and bowtie-clad, his white button-down shirt rolled up to his elbows and wrinkled from their adventure on Barcelona. Pale skin brushing sweetly against hers. Soft, pink lips nearly tangible. He was real. She could reach out and touch him if she wanted to. And still, he was the one boy Mels couldn't have. He smiled lazily as he traced a fingertip down her cheek and along the bridge of her nose. For a moment, she thought he might change his mind, but his expression shifted and he pulled back, eyeing her cautiously.

"We've just been to one of the most beautiful planets the universe has to offer. We've seen volcanoes erupt in the distant mountaintops, with the comfort of knowing we can't be touched. We've climbed to the top of the tallest tower and danced in the rays of the setting Barcelonian sun," he whispered, pausing for a moment to release a short, breathless chuckle as he exchanged his smile for a look of pure longing. "And all I could think about was her."

The words shot through Melody's heart like a dagger, twisting the nerves of her stomach. She refused to look at him, knowing full well that a single glance would fracture her façade.

"She must be something special," Mels finally managed.

"Yeah, she is," the Doctor said fondly, "but she's trapped here, and…well, it's not exactly her fault. It's all a bit complicated. I really need to see her tonight, but if the guards ever found out…" The Doctor trailed off, anxiously running his hands through his hair as he peered around the corridor again. He turned back toward Mels, his expression troubled.

"Will you do this for me? I'll make it up to you one day, I promise."

Yeah, sure you will. Go on, then, raggedy man. Twist the knife.

"Bet that's what you tell all the girls," she said with a humorless chuckle.

The Doctor smiled, pure and genuine this time, and kissed the top of Melody's forehead in gratitude as he handed her the spare uniform.

"Doctor," she said, before she could stop herself. "Who is she?"

The Doctor paused on the edge of a clever lie, and then smiled.

"Spoilers," he said. "Really, though. Ridiculously complicated, timey wimey spoilers. I wish I could tell you, but I just can't."

Mels rolled her eyes in frustration, growing more irritated with him by the second.

"Who is she to you, then? Why's she so special? And why tonight?"

The Doctor's smile widened, and this time, he didn't miss a beat.

"She's my wife, Mels, and this is our wedding night."

He gave her a soft smile, turned on his heel, and disappeared down the opposite corridor, swallowed in shadow. With a sob of despair, Melody sank to the floor, the overlarge guard's cap sinking down over her eyes.

Never fall in love with a man from the stars, she mused sadly, pulling a small bottle of Barcelona's finest chocolate liqueur from her purse. She smiled softly and downed a quarter of the bottle, delighting in its fantastic taste. The cruel irony of the situation, of where and with whom she had ended up tonight finally registered, and Mels couldn't help but laugh. Especially one you're meant to murder.

• • •

This wasn't the Doctor's first time in Stormcage, and it certainly wasn't his first time in prison, but that's a different story entirely. He found River instantly — the only light in this dark corridor, with rows of narrow containment cells and an eerie silence radiating chills throughout any passerby that dared walk its halls. Most of the inmates had already gone to sleep, as it was well past four in the morning, with the exception of River Song. There she sat, cuddled up in the corner of her tiny bed, covers pulled up to her chin, and a dark blue journal resting across her lap. She looked up the moment his fingers slid around the metal bars, and her lips curled into a smile.

"And what sort of time do you call this?" she scolded as she shrugged out of her comforter to check the clock on her vortex manipulator, revealing perfectly-curled blonde hair that fell in rivulets to her shoulders. The Doctor flashed her his best apologetic smile, and whipped his sonic screwdriver from a pocket in his tweed jacket, unlocking the cell with a simple click.

"Thought I'd make a house call," he said, strolling into her room and observing the monotonous color of the walls with a look of disgust. It seemed unfair, really, that River had spent nearly all of her life in one form of a prison or another, but the Doctor was determined to make it up to her. It was, after all, in a very twisted way, his own fault that she was here.

"Where are we off to this time?" River asked, appearing behind him suddenly. Her hands curved around the muscles of his arms, her scarlet fingernail paint a stark contrast to her pale skin. He curled into her touch, and found himself properly dumbstruck. River pressed herself against him, the only fabric between her skin and his clothes a white silken nightgown, flowing from the curve of her breasts to the floor, like an intimate wedding dress. The Doctor could only stare, incapable, for the first time in his life, of speech.

"Nowhere," he finally managed. "We're staying right here."

"But, sweetie, the guards…"

"I've brought someone with me, and she's agreed to stand guard out in the main corridor."

"Oh God. You haven't got Amy—"

"No, no, of course not," he quickly amended, making a face. "It's someone else. Someone you might recall from a very, very long time ago."

Realization dawned on River as the blurred, forgotten memory returned to her. She promptly smacked the Doctor on the arm and hissed, "You bad, bad man. You made me believe I was dreaming it all up that night."

"Did I? Well, suppose I will have," he said shamefully, rubbing his arm absentmindedly. River moved in closer again, a flurry of emotions flashing across her eyes as she stared into his.

"You really hurt me that night. I spent all that time trying not to think about the fact that you were here with another woman, and…well, now I suppose that woman was me, wasn't it? This is all very confusing. It's still difficult to remember. Obviously, the Barcelonian liqueur served its purpose. Had a bit too much, though. Trouble keeping it down. Speaking of which, I am sorry about your glass floor…"

The Doctor made a face, but reasoned that he probably deserved it after the way he'd hurt Mels. The way he was currently hurting Mels. He tried to comfort himself with the fact that he was doing the right thing. That he would make it up to her, someday. That he was about to make it up to her right now.

"Doctor, why did you bring her here?" River asked, the sorrow in her voice prickling the back of his throat as he fought for a reasonable answer.

"Why did you pull a gun on me and blow holes in my TARDIS?" he retorted.

"Fair enough," she said, rolling her eyes. "Still, that is quite an evil revenge tactic. In her timeline, she hasn't even done it yet."

"Let's just call it preemptive punishment," he said. "Besides which, Kovarian and her army of religious whatsits raised you to become a weapon. You were meant to despise everything that I am, to want to kill me. That event, my death, as you well know, is a fixed point in time. I couldn't have you spoiling history just because I'm irresistible and you happened to fall for me."

"Oh, I hate you," she said, smiling in spite of her vexation.

"You see? My plan worked. But really, you don't," he said, taking her hands in his and lightly kissing her palms. She sighed and fell into his arms, tracing the curves of his shoulders with her fingertips, and nestled into the arch of his neck.

"What brings you here, then, if not some mad adventure that will most likely get us killed, in spite of our established timeline?"

"We never did get our wedding night," he whispered softly, leaving a trail of kisses from her chin to her collarbone.

"That was in a different universe," she laughed, swatting him delicately on the head as he attempted to snake his hands underneath her nightgown.

"I can remember it. Every detail of that day exactly. So I'm still counting it."

"Oh, shut up," she teased, pulling him closer and curling her fingers into the strands of his hair as he hungrily kissed every inch of her skin that wasn't covered in the fine fabric of her nightgown. The Doctor, of course, had every intention of removing that pretty little hindrance.

"Make me," he growled, winding himself around her like a helix, until there was nothing left between them but the steam of their breath and the touch of skin against skin.

• • •

When the Doctor crept back into the main corridor several hours later, it was to find that Mels had completely disappeared. Silently panicking, he threw his hands into the pockets of his tweed jacket, frantically searching for his sonic. He felt a poke in the small of his back, and whipped around to find River, her hair now properly disheveled, handing him his screwdriver. She then pointed to the corner of the corridor, where a young girl slept soundlessly in the shadows, curled up in an overlarge guard's uniform and slumped against the front doors of the TARDIS.

"Penny in the air," River said, giggling at the Doctor's complete disregard for the obvious. He smiled in relief, wrapped his arms around River's waist, and kissed her with all of the strength he had left, promising he'd come see her again soon.

"I know," she whispered, kissing him softly, before wandering down the corridor and returning to her cell. The Doctor sighed as he strolled over to where Mels slept. Not wanting to wake her, he delicately removed the guard's uniform, hung it back up on its hook, and carried her into the TARDIS. He laid her down on the newly-conjured couch, and bundled her up in his tweed jacket, silently thanking the TARDIS for being so accommodative.

On cue, Mels promptly turned over, mumbled, "and the penny drops," and covered his shiny glass floor in her sick. The Doctor grimaced in disgust, but quickly converted his expression to a smile, and kneeled down beside her. He brushed her hair back from out of her eyes and kissed the top of her forehead, and Mels smiled contentedly in her sleep. The Doctor sighed heavily, shifted to the controls and set the coordinates for Melody's backyard. He landed as quietly as he could, found his way to her bedroom, and tucked her up into her bed.

In the morning, Mels awoke, disorientated and quite hung-over, her purse empty of Barcelonian spirits, her mind filled with brand new, impossible dreams that she could swear were real, and an ache in her heart that she couldn't quite explain. It was all a bit shambolic, but if Mels was certain of anything, it was this: it wouldn't be the last she'd see of that mad time traveler and his bigger-on-the-inside blue box.

#doctor who#eleven x river#eleven/river#11th doctor#eleventh doctor#river song#melody pond#doctor who fanfiction#the wedding night of river song#fairytalesandfolklore#fairytales-and-folklore#fairytalesandfolklore fanfiction#fairytalesandfolklore doctor who

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sir John Boardman

Archaeologist who became a leading authority on the history of Greek art, with a particular interest in gems and finger rings

As a student, John Boardman, who has died aged 96, was able to recite by heart texts in Attic Greek, the form of the language used in ancient Athens. But while studying classics at Magdalene College, Cambridge, he encountered two archaeologists whose work encouraged him to apply that flair to the study of classical objects: Charles Seltman showed him coins, and Robert Cook vases.

To these he added carved gems, sculpture and architecture, on all of which he became a leading authority, and the author of more than 30 books.

On graduating in 1948, he took Cook’s advice not to study for a doctorate, but to go to Greece and do some research there. At the British School in Athens for the next two years, as well as travelling to destinations including Crete and Smyrna, he worked in the depths of the Athens National Museum on vases from the island of Euboea (the modern Evvia).

The diagnostic pot shape that he identified enabled later archaeologists and historians to track the paths of Greeks and Greek culture to the east – Al Mina in Syria – and the west – Pithecusae, today’s Ischia, in the gulf of Naples – and at many points between.

The Greek islands and the diaspora around the Mediterranean came to be recurring themes in Boardman’s work. In 1964 he published two books, The Greeks Overseas: Their Early Colonies and Trade, and Greek Art, both of which went on to further editions.

On his first visit to Greece he met Sheila Stanford, an artist, and after he had completed his national service in the Intelligence Corps (1950-52) they married in Britain. He then returned to the British School as assistant director (1952-55), and was given his own dig, on the island of Chios.

His party of excavators and helpers there included Michael Ventris, the architect who shortly aftewards announced his decipherment of the Linear B syllabic script as an early form of the Greek language, and Dilys Powell, the eventual film critic of the Sunday Times.

Back in Britain, Boardman served as an assistant keeper at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (1955-59). Its Cast Gallery, containing plaster casts of some 900 Greek and Roman sculptures, became his preferred academic home base, and he published a catalogue of its Cretan collection (1961).

Working on another, private, collection of art objects in the 1990s gave him ideas about world art, its interconnections and aims. This led him to distinguish three main “belts”: a northern one, running from Siberia to North America, where nomads favoured small items, often depicting animals; an urban one, from China to central America, more given to monumental architecture; and a tropical one characterised by human forms, notably of ancestors. He explored these ideas in The World of Ancient Art (2006).

Other publications included Greek Gems and Finger Rings (1970); handbooks on Athenian black-figure and red-figure vases (1974 and 1975); a lecture series given at the National Gallery of Art in Washington and published as The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity (1994); Persia and the West (2000); The Archaeology of Nostalgia: How the Greeks Re-created Their Mythical Past (2002); numerous catalogues, particularly of gem collections, including the royal one at Windsor Castle; and excavation reports from Chios and from Tocra, in Libya.

After the Ashmolean appointment came university posts at Oxford, as reader in classical archaeology (1959-78) and then Lincoln professor of classical archaeology and art (1978-94). As professor emeritus, he continued to work from offices first in the Ashmolean and subsequently the classics faculty’s Ioannou Centre.

In 2020 he produced his autobiography, A Classical Archaeologist’s Life: The Story So Far. The last of its three parts focuses on a field of “minor” art that he showed could be anything but: Greek and Roman gems and finger rings. Called simply “Gems, Bob and Claudia”, it details the work that Boardman did first with the photographer Bob Wilkins and later an archivist of the Beazley Archive, in Oxford, Claudia Wagner. With her he co-authored Masterpieces in Miniature: Engraved Gems from Prehistory to the Present (2018).

Born in Ilford, Essex, John was the son of Clara (nee Wells), who had been a milliner’s assistant, and Arch (Frederick) Boardman, a clerk in the City. The family was not academic, but John was impressed by what he saw at the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum when he visited them with his father, who died when John was 11.

While at Chigwell school, John experienced second world war aerial bombardment, of which he later had vivid memories. He found the study of Greek to be “magical”, and the school’s headteacher encouraged him to apply for a scholarship at his former Cambridge college.

Though his own career developed at a time when a doctorate was not obligatory, Boardman went on to supervise vast numbers of graduate students, scattered over several continents. He had an extraordinarily acute and retentive visual memory, was prodigiously efficient and well organised in his teaching – his lectures on Greek architecture and sculpture were a revelation – as in his research and writing, and welcomed the assistance provided by digital technology.

I first met him in his Ashmolean office, in 1969, keen for him to be my doctoral supervisor. Almost the first word he uttered was “Sparta”: not long before, he had published an account vastly improving on previous understanding of the sand, earth and relative dating of the artefacts found at the Artemis Orthia sanctuary site there. Like many others, I appreciated his meticulous standards of archaeological observation and historical interpretation.

Boardman once wrote that he felt more at home intellectually outside Oxford, indeed outside Britain, and he was involved with and recognised by institutions in Ireland, mainland Europe, the US and Australia. For almost three decades he was on the board of the Basel-based Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (1972-99).

His activities in Britain were still considerable. He edited the Journal of Hellenic Studies (1958-65) and was a delegate of the Oxford University Press (1979-89). At the Royal Academy in London from 1989 onwards he occupied what had originally been Edward Gibbon’s seat of professor of ancient history. He was made a fellow of the British Academy in 1969, and knighted in 1986.

While ready to express a view in serious academic controversies he was resolutely apolitical. Nonetheless, he took the view that Lord Elgin’s dubiously acquired collection of sculptures from the Parthenon and other structures in Athens purchased by the UK in 1816 should remain in its entirety under the curation of the British Museum Trustees.

He received a lot of support from the publishers Thames & Hudson, and his very last publication came in the month of his death, in their Pocket Perspectives series. John Boardman on the Parthenon is a lightly illustrated repackaging of the lively text he had composed to accompany the black and white photographs of David Finn in the same publisher’s The Parthenon and Its Sculptures (1985).

Sheila died in 2005. He is survived by their children, Julia and Mark.

🔔 John Boardman, archaeologist and classical art historian, born 20 August 1927; died 23 May 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ségurant, the Knight of the Dragon (2/4)

Let us continue down our path along the documentary. Here is the German version of it, by the way, if you are interested.

So, last time we left with the sad conclusion that the origins of Ségurant were not from Great-Britain: he appears nowhere in England, Scotland or Wales. If there is nothing in British land, the next move is of course towards the land where Ségurant's tale was first found out, and the second main source when it came to Arthuriana: France.

The documentary reminds us that the Arthurian crossed the seas and arrived in France in the 12th century. It was first written about in France by a man from Normandy named Wace (who was the one who invented the Round Table), and then it was time for Chrétien de Troyes and his famous romans (first romans in French literary history and the beginning of the romanesque genre) – which became best-sellers, translated, imitated, continued and rewritten throughout all of Europe, becoming the ��norm” of the literary culture of Europe at the time (in non-Latin language of course). Chrétien de Troyes’ novel became especially popular among the expanding cities and newly formed bourgeoisies of the time, making Lancelot and Perceval true European heroes, and resulting in thousands of Arthurian manuscripts being sent and created everywhere.

There is a brief intervention of Michel Zink explaining what was so specific about Chrétien’s romans: by the time Chrétien wrote his novels, the legend of king Arthur was well-known and famous enough that the author did not feel the need to remind it or expand about it. As in: Chrétien’s novels all happen at the court of king Arthur, or begin at the court of Arthur, but none of them are about Arthur himself. Arthur and his court are just the “background” of his stories – Chrétien’s heroes are the knights of the Round Table, who were until this point basically secondary characters in Arthur’s own story. And all the novels of Chrétien follow the same basic structure of “education novel”: they are all about a young man who goes on a quest or goes on adventures, and in the process discovers his own identity and/or love and/or his destiny. And they all end with the young man being worthy of sitting at the Round Table ; or if they were already at the Round Table, they are even worthier of sitting at it.

But then the documentary completely ditches the French aspect to move to… Italy. As Arioli explains, as he was investigating the origin of the Prophéties de Merlin manuscript in which Segurant’s story was consigned, he checked an inventory of all the Merlin’s Prophecies manuscripts and thus entered in contact with the one that had made it, Nathalie Koble. And talking with her, she led him to a Merlin’s Prophecy manuscript kept in Italy – more precisely in the Biblioteca Marciana of Venice, one of the greatest collections of medieval manuscripts in the world. The documentary goes through a brief reminder of how in the 13th century the Republic of Venice was one of the greatest sea-powers of Europe, and formed the crossroad between the Orient and the Occident through which all the precious goods travelled (spices, silk… but also books) ; and how in the 14th century Petrarch had the project of making a public library in Venice and offered his own collection of books to the city, leading to what would become a century later the Biblioteca Marciana… And so we reach the manuscript Koble showed Arioli. A very humble manuscript of the Prophéties de Merlin – no illumination, no illustration, a small size, not of the best quality ; but that’s all because it was a mass-produced best-seller at the time in Venice. Koble briefly reminds us of the enormous success of the genre of the Merlin Prophecies ; of how French was spoken in Venice because it was the vernacular language of nobility (hence why this manuscript is in French) ; and of who was Merlin and why his prophecies interested so much (being the son of a human virgin and an incubus devil, he had many powers, such as metamorphosis – transforming himself or others – and seeing both the future and the past, aka “existing beyond temporality and memories” as Koble puts it). And finally she points out the very interesting detail that the Merlin Prophecies are always coded, need to be deciphered… But the process is very easy for anyone who is an informed reader.

Indeed, many of the “prophecies” of Merlin are actually coded and metaphorical descriptions of events part of the Arthurian legend. Koble presents us a specific prophecy: “A leopard named Of the Lake will go to the kingdom of Logres and will open his heart to the crowned snake. But he will sleep with a white snake and remove its virginity, while believing he slept with the crowned snake”. For a fan of Arthuriana, it is clear that the “leopard of the lake” is Lancelot du Lac, while the “crowned snake” is Guinevere.

And then, Koble showed Arioli a prophecy contained in this manuscript that apparently was about Ségurant. “Know that the dragon-hunter will be bewitched at the Winchester tournament. A stone will shine on his tent, projecting a great light outside and inside. When he will be king in the Orient, this stone will be placed onto his crown. When he will cross the sea to visit my grave, he will place the stone within the altar of Our-Lady (Notre-Dame). And thus, the dragon of Babylon will seize it.” The prophecy clearly is about Ségurant. Now, the actual author of this manuscript is unknown – as Koble explains, 13th century romanciers who wrote in prose loved inventing false identities for themselves, many times passing off as Merlin himself. The alias of the author of this specific manuscript is “Richard of Ireland”, but Koble’s personal research found out he was actually a man of Venice. Indeed numerous prophecies in the book describes the landscape surrounding Venice or Venice itself ; and there are many references to the political events of Venice at the end of the 13th century.

So, in conclusion: Ségurant was a great heroic figure in the region of Venice at the time. And so Arioli became convinced that Ségurant’s origins were to be found in Northern Italy, and spread from Venice to the rest of Europe.

Our next move is to the Italian Alps – to the Italian Tyrol, and more specifically to Roncolo Castle. Built in the 13th century, it was then bought in 1385 by the Vintler brothers, Nicolas and Francesco/François. The Vintler brothers were part of a bourgeois family that had recently become part of the nobility, and to play onto this, to “legitimate” their nobility and show they had well “adopted” the lifestyle of the nobility, they commissioned a set of medieval frescos, filled with knights and ladies, bestiary animals (fictional or real). To this day, the frescos of Roncolo Castle still form the greatest cycle of Arthurian wall-paintings in the world. And the most interesting part of those paintings, for Arioli’s investigation, is the “Gallery of the Triads”. A gallery where, as the name says, triads are depicted, representing the ideals of knighthood. There is a triad of the “greatest kings” – King Arthur, Charlemagne and Godfrey of Bouillon. There is a triad of the “three greatest knights of the Round Table”: Perceval, Gawain and Yvain (the Knight of the Lion). There is the “three most famous couple of lovers”, with Tristan and Isolde at the center. And finally we have the triad of the “Three most famous heroes”. Only two of them are named – one being Theodoric “with his sword”. And the other… Is “Siegfried, with his crown-depicting shield, as he was described in the Song of the Nibelungen”.

And here’s the new twist in our investigation. Siegfried… Ségurant… Two dragon-killers with similar names. As it is explained in the documentary, the Tyrol was not a closed land, but rather the junction point between Southern Germany and Northern Italy. As a result, Germanic literature was just as popular here as the Arthurian legend – in fact we have a 13th century manuscript written in the Tyrol that contains the Song of the Nibelungs. And so here is Arioli’s new theory: Siegfried crossed the Tyrol, reached Italy, and there became Segurant, the Knight of the Dragon.