#robert dorfman

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

from addica mavis / addicamavis

somewhere that’s green 💚

#guthrie little shop#lsoh#will roland#t. mychael rambo#david darrow#robert dorfman#kiko laureano#gabrielle dominique#erica durham#vie boheme

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Action Comics #346 ‘The Man Who Sold Insurance to Superman!’ and ‘The Case of the Superman Impostor!’ (1966) by Leo Dorfman, Wayne Boring, Robert Bernstein, Jim Mooney and others. Edited by Mort Weisinger. Cover by Curt Swan and George Klein.

(1967)

#action comics#supergirl#kara zor-el#linda danvers#superman#kal-el#clark kent#dc comics#leo dorfman#wayne boring#robert bernstein#jim mooney#mort weisinger#curt swan#george klein#silver age comics#comics

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Guthrie Theater has revealed the cast and creative team for Little Shop of Horrors with book and lyrics by Howard Ashman, music by Alan Menken and directed and choreographed by Marcia Milgrom Dodge. In this musical, an employee at a failing florist shop attempts to build business with a peculiar — and bloodthirsty — exotic plant. The show opens on Friday, June 28 and will play through Sunday, August 18. […] The cast of Little Shop of Horrors includes China Brickey (Guthrie: A Christmas Carol, Murder on the Orient Express) as Audrey, Time Brickey (Guthrie: debut) as Denizen of Skid Row/Puppeteer, David Darrow (Guthrie: The Tempest, Sunday in the Park With George, The Parchman Hour) as Orin/Others/Denizen of Skid Row, Gabrielle Dominique (Guthrie: Guys and Dolls, West Side Story) as Crystal, Robert Dorfman (Guthrie: The Tempest, Frankenstein – Playing With Fire, Indecent) as Mushnik, Erica Durham (Guthrie: debut) as Chiffon, Yvonne Freese (Guthrie: debut) as Denizen of Skid Row/Audrey II Puppeteer/Puppeteer, Kiko Laureano (Guthrie: debut) as Denizen of Skid Row/Puppeteer, Joey Miller (Guthrie: debut) as Denizen of Skid Row/Puppeteer, T. Mychael Rambo (Guthrie: Sunday in the Park With George, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Music Man) as Denizen of Skid Row/Audrey II Live Voice, Will Roland (Guthrie: debut) as Seymour and Vie Boheme (Guthrie: West Side Story, Refugia) as Ronnette.

finally… will roland seymour krelborn

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

A DAME BEFORE HER TIME -- A DAME TO DIE FOR.

PIC INFO: Spotlight on a promotional image of English actress & singer Julie Andrews as British glamour icon Gertrude "Gertie" Lawrence, from the 1968 American biographical musical film "Star!," directed by Robert Wise. 📸: Herbert Dorfman/Getty Images.

Source: www.townandcountrymag.com/leisure/g32825588/julie-andrews-young.

#Julie Andrews#Gertrude Gertie Lawrence#Gertrude Lawrence#Julie Andrews 1968#Cinema#Those Were the Happy Times 1969#Those Were the Happy Times#Gertie Lawrence#English Actress#Movie Actress#Film Actress#Female form#Female figure#Robert Wise#Star! 1968 Movie#Hair and Makeup#Sixties#Actress#British performer#Costume Design#1960s#Star! Movie 1968#Female beauty#60s#Biographical musical film#Star! 1968#1968#60s Movies#Feminine beauty#Star!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Allan Jones (January 14, 1938 – October 23, 2024) Popular singer and actor. He was primarily a straight-pop singer (even when he recorded contemporary material) whose forays into jazz were mostly of the big-band/swing music variety. He won two Grammy Awards and received five nominations for Grammys. He notably sang the opening theme song for the television series The Love Boat.

Jones was born in Hollywood, California, on the night his father Allan Jones recorded his signature song "The Donkey Serenade", resulting in the younger Jones' assertion that he was "practically born in a trunk." Jack attended University High School in West Los Angeles and studied drama and singing. His mother was actress Irene Hervey.

Jones made his film debut in Juke Box Rhythm (1959) playing Riff Manton, a young singer who is involved romantically with a princess (Jo Morrow). He sings three songs in the film. He acted in minor films such as The Comeback (1978), Condominium (1980), and Cruise of the Gods (2002). He had a humorous cameo in the film parody Airplane II: The Sequel (1982); as Robert Hays' character avoids searchlights while escaping captivity, the beams become a spotlight on Jones, performing a verse from his Love Boat TV theme song.

He became a staple on 1960s and 1970s variety shows performing on The Dinah Shore Chevy Show, The Ed Sullivan Show, The Andy Williams Show, The Dick Cavett Show, The Hollywood Palace, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, The Carol Burnett Show, The Jerry Lewis Show, American Bandstand, This is Tom Jones, The Dean Martin Show, The Judy Garland Show, Playboy After Dark, The Jack Benny Program, The Steve Allen Show, and The Morecambe and Wise Show in the United Kingdom.

Jones twice hosted the National Broadcasting Company (NBC-TV)'s top-rated rock and roll music series Hullabaloo (1965-1966), and was featured in two prime-time specials, Jack Jones on the Move (1966) and The Jack Jones Special (1974). He appeared on the Password TV game show with Carol Lynley in 1964 and multiple times with Joan Fontaine in 1967. He provided the vocals to the theme song of Funny Face, "The Kind of Girl She Is". When the show returned renamed as The Sandy Duncan Show, he was replaced by an anonymous chorus. He also guest-starred in a cavalcade of television series of the era, such as The Rat Patrol, Police Woman, McMillan & Wife, The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries; two game shows $weepstake$, Match Game, and the sitcom Night Court.

Jones played himself in the episode "The Vegas Show" of It's a Living. He sang the opening theme for the television series The Love Boat (1977–1985), and appeared in a 1980 episode with his father Allan.

Between 1973 and 1978, Jones hosted The Jack Jones Show, directed by Stanley Dorfman, produced and broadcast by the British Broadcasting Corporation's BBC-2 network. In 1990 he appeared in the Chris Elliott television show Get a Life on the Fox television network. (Wikipedia)

IMDb Listing

Discography

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

DC Special #3 ‘The Cheetah's Thought Prisoners’, ‘The Maid of Menace!’, ‘Special Delivery Death!’ and other stories (1969) by William Moulton Marston, Harry G. Peter, Leo Dorfman, Jim Mooney, Robert Kanigher, Carmine Infantino and others. Edited by Mort Weisinger and E. Nelson Bridwell. Cover by Nick Cardy and Neal Adams.

DC Special #3 June 1969

#dc special#wonder woman#supergirl#black canary#dc comics#william moulton marston#harry g. peter#leo dorfman#jim mooney#robert kanigher#carmine infantino#mort weisinger#e. nelson bridwell#nick cardy#neal adams#comics

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Kiss of the Spider Woman” ’s Voices in the Dark

The Argentinean writer Manuel Puig’s novel-in-dialogue forces the reader to be both director and detective, interpreting how the lines will be spoken and searching each sentence for clues as to what is going on.

By Isaac Butler December 11, 2022

icki Baum, the author of “Grand Hotel,” once wrote that “you can live down any number of failures, but you can’t live down a great success.” After witnessing the fall and rise of his novel “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” Manuel Puig likely would’ve agreed with her. Originally released to critical dismissal—Robert Coover called it “a rather frail little love story” in the Times—the book landed with a thud, managing to make Puig a celebrity in the gay enclave of New York City’s Christopher Street, but not much else. Yet “Kiss of the Spider Woman” had a remarkable afterlife. A play adaptation, co-authored by Puig, became an international success, and led to an Oscar-winning film starring William Hurt and Raul Julia as well as a hit musical written by John Kander, Fred Ebb, and Terrence McNally. Puig disliked the film, and, shortly after a disastrous workshop of the musical at suny Purchase, died from a heart attack, at the age of fifty-seven. Yet for all his frustration with the adaptations of his novel, they guaranteed its longevity. “Kiss of the Spider Woman” is the only book of Puig’s in English that remains steadily in print—his first novel, “Betrayed by Rita Hayworth” was recently issued for the second time this century by McNally Editions—and the cover of the Vintage International paperback boasts the same typeface and image as the playbill of the Broadway production.

The film and musical so overshadowed their source material that, when I first encountered the book, in a course called Subjectivity in Literature my freshman year of college, I thought that my eccentric professor had assigned a novelization to us as a way of challenging our assumptions about which books were worthy of study. Within a few pages, I realized my mistake. “Kiss of the Spider Woman” is a mysterious, formally inventive, beguiling work about two prisoners during the Dirty War in Argentina: a Marxist guerilla named Valentín and a gay window dresser named Molina, who develop a transformative relationship as the latter narrates the plots of his favorite movies to the former. When I was nineteen, “Kiss of the Spider Woman” struck me as a work about finding love and preserving one’s humanity in the most inhumane of places. It is in some ways the opposite of Ariel Dorfman’s “Death and the Maiden,” a play in which the psychic scars of the Pinochet regime in Chile prove a universal solvent, dissolving any attempt at decency, or humanity, or truth. Reading the novel in the period between the passage of the Defense of Marriage Act and the repeal of sodomy laws in Lawrence v. Texas, I believed it to be a work of protest art, one that defiantly asserts Molina’s personhood even amid the Dirty War’s depredations. Reading “Kiss of the Spider Woman” today, the prison seems less like a real place, and the novel seems far trickier, and far harder to nail down to any one meaning. “Kiss of the Spider Woman” slips between different interpretations, just as its late-night conversations wander from the most frivolous of trivialities to the deepest of truths.

Puig would likely have objected to the idea that frivolity was opposed to truth. His sensibility was rooted in cursi, a word that lacks a direct English translation but is key to the consciousness that underlies his work. Cursi is the Blanche DuBois to machismo’s Stanley Kowalski, passionately insisting “I don’t want realism, I want magic!” Its closest equivalent in the United States is camp, but the two are not exactly the same. There’s a yearning to cursi, and a nostalgic fabulousness. Puig was the great twentieth-century writer of the cursi sensibility. He disdained the self-seriousness of many of his contemporaries in the Latin American Boom, particularly Gabriel García Márquez, who he felt had been ruined by critical praise. “Every sentence pretends to be the maximum phrase of all of literature,” Puig griped, about the future Nobel Prize winner’s “The Autumn of the Patriarch,” “and each one ends by weighing a ton.” Puig’s novels are deliberately playful and provocatively effeminate. They often ride the line between satire and sincerity, producing a result that is somehow both sincerely felt and heavily ironized. As Puig himself put it once in a letter, “that’s the real me: Cursi and truthful.”

“Kiss of the Spider Woman” grew out of Puig’s frustrations with the politics of his era and his contemporaries. He eschewed explicit polemic in his work, which led to his being viewed with suspicion by both the left and the right. His first novel was panned by the center-right magazine La Nacíon for using colloquial Argentinean Spanish and accused of having Peronist sympathies. Living among fellow exiled Argentinean intellectuals in Mexico City, Puig found that he “was still a reactionary for not having joined the movement. Worst of all my book had been banned by the right wing and the Argentinian left didn’t care.” From this pain, he began taking notes on a novel in which two men—one straight and one gay, who “doesn’t have much education, but a great fantasy life”—would “meet through a mediator—movies.”

Puig, who wanted to be a screenwriter and only turned to writing novels after his thirtieth birthday, all but grew up in a movie theatre. According to “Manuel Puig and the Spider Woman,” a biography of Puig by his translator and friend Suzanne Jill Levine, his home town of General Villegas, in the Argentine Pampas, had one movie house, which showed a different film every day. Beginning in 1936, his mother, Malé, with whom he would remain extremely close throughout his life, took him to see “mostly American stuff” almost daily, at 6 p.m. Staring at the screen, he fell in love with the female stars of the thirties, constructing a pantheon out of Rita Hayworth, Joan Crawford, Norma Shearer, Greta Garbo, and others. “I understood . . . the moral world of movies, where goodness, patience, and sacrifice were rewarded,” he later said. “In real life, nothing like that happened. . . . I, at a certain moment, decided that reality was what was on the screen and that my fate—to live in that town—was a bad impromptu movie that was about to end.” Malé had initially only intended to stay in General Villegas for a year and passed her frustrated dreams of cosmopolitan life down to her son. “It was like living in exile,” he would later say, and, in his first two novels, he would create a thinly veiled version of his home town, called Colonel Vallejos, and treat it unkindly. As Clara, his fictionalized aunt in “Betrayed by Rita Hayworth,” puts it:

When I got off the train, my first impression was awful, there’s not a single tall building. They’re always having droughts there, so you don’t see many trees either. In the station there are no taxis, they still use the horse and buggy and the center of town is just two and a half blocks away. You can find a few trees that are hardly growing, but what you don’t see at all, anywhere, is real grass.

The Puigs left Villegas, moving to Buenos Aires by 1949, and it’s unclear whether Manuel ever returned to his home town, except in his imagination. Much of his life was lived in one form of exile or another, particularly after his novel “The Buenos Aires Affair” was suppressed in Argentina in 1974.

“Betrayed by Rita Hayworth” highlights again and again the contrast between the magic of cinema and the tawdry doldrums of everyday life. Puig preferred melodramas, which he called “the language in which the unconscious speaks,” along with screwball comedies and, once he got over the trauma of seeing “Bride of Frankenstein” at too young an age, cheap horror films. In his essay “Cinema and the Novel,” Puig wrote that the films of the thirties and forties had such lasting power because they “really were dreams displayed in images. . . . When I look at what survives in the history of cinema, I find increasing evidence of what little can be salvaged from all the attempts at realism.” He disliked much of Italian neorealism and the films of Martin Scorsese (“so much pretension and slowness”), and called Meryl Streep, Ellen Burstyn, Jill Clayburgh, and Glenn Close “the Four Horsewomen of the Apocalypse” for ushering in a more realistic femininity onscreen.

Escape into the dream world of cinema was an obsessive quest. Later in life, he would write his friend Guillermo Cabrera Infante a long list of the authors of the Latin American Boom as Hollywood starlets. Borges was Norma Shearer (”Oh so refined!”), García Márquez was Elizabeth Taylor (“Beautiful face but such short legs”), Mario Vargas Llosa was Esther Williams (“Oh so disciplined (and boring)”). Among the eighteen names was Puig’s own. He was to be played by Julie Christie, a “great actress, but since she has found the right man for her (Warren Beatty) she doesn’t act anymore.” Years later, after his writing had brought him money and international acclaim, Puig would buy television sets and VCRs for friends, and then cajole them into recording classic films for him, eventually amassing a library of more than three thousand movies on upward of twelve hundred video cassettes.

Popular culture at its most cursi undergirds Puig’s work. It’s there in his titles— “Betrayed by Rita Hayworth,” “Heartbreak Tango,” “The Buenos Aires Affair,” “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” “Pubis Angelical,” “Eternal Curse on the Reader of These Pages,” “Blood of Requited Love,” “Tropical Night Falling”—which feel as if they could be printed in the most lurid of fonts, accompanied by the most sensational of exclamation points. His frustrated attempts to work as a screenwriter gave birth to his signature style, in which dialogue, stream of consciousness, and fake secondary sources like diary entries, surveillance reports, and newspaper articles bump up against one another. This marriage of high modernist experimentation with low cultural reference points and subject matter frequently led to his dismissal by Argentinean literati. He struggled for years to publish “Betrayed by Rita Hayworth,” and the accusation that he was a lightweight shadowed him even after his death. Reviewing Levine’s biography in the Times, Vargas Llosa wrote that “of all the writers I have known, the one who seemed least interested in literature was Manuel Puig,” before sniffing that “Puig’s work may be the best representative of what has been called light literature . . . an undemanding, pleasing literature that has no other purpose than to entertain.” Vargas Llosa’s estimation couldn’t be further off the mark. While Puig’s novels are entertaining—often riotously so—his formal techniques aren’t mere games, and his experimentations with dialogue still seem radical and groundbreaking decades after his death.

The novel in dialogue form is not new—authors from Diderot to Woolf and Gaddis have experimented with it—but there is something eternally transgressive in its austerity. To work only in dialogue is to limit or altogether renounce such pleasurable tools as point of view, description, free indirect discourse, and narration. Playwrights know that their dialogue will be mediated through a production, through the choices and interpretations of a director and actors, and they can leave instructions in the form of stage directions and notes explaining their intent. But the novel in dialogue forgoes all this. It forces the reader to be at once director and detective, interpreting how the lines will be spoken, and searching each sentence for clues as to the basic facts of what is going on.

“Kiss of the Spider Woman” takes place in prison, yet it is six full pages of testy back-and-forth before the reader gets any glimpse of where the story is situated. Even these clues are related briefly:

The next movie Molina swoons over is “Destino,” a Nazi film about the evils of the French Resistance. The movie, a composite invented by Puig, is an inversion of the Hollywood film “Paris Underground,” its female protagonist rather unsubtly named Leni. Molina knows that it’s Nazi propaganda but loves it, “because it’s well made, and besides it’s a work of art.” The stage appears to be set for an extended dialogue about the relationship between art and truth, aesthetics and politics, naïveté and logic, and so on. Yet Puig shifts gears again, introducing footnotes written in parodic academese that trace a post-Freudian theory of homosexuality. The footnotes grow so extensive that they take over the book, drowning out the prisoners for pages on end. These give way to stream-of-consciousness asides that take us into Molina and Valentín’s thoughts, the former self-pitying and sentimental, the latter obsessive and fevered. The text becomes marked with ellipses to denote physical actions that would normally be described, culminating in a sex scene composed solely of the words spoken by the two men:

I can’t see at all, not at all. . . . it’s so dark. . . . Slowly now . . . . . . No, that way it hurts a lot. . . . Wait . . . no, it’s better like this, let me lift my legs. . . . A little slower . . . please . . . . . . That’s better. . . .

“Kiss of the Spider Woman” moves from an avalanche of verbiage to a space where language is inadequate, and out again, with the two characters, having physically joined their bodies, finding new selves beyond the limits of their roles. It’s not entirely clear whether, were the book written today, Molina would even be described as a man. He often identifies as a woman throughout “Kiss of the Spider Woman” and at one point says, “As for my friends and myself, we’re a hundred percent female. . . . We’re normal women; we sleep with men.” Here, Molina is contrasting his social circle with “the other kind [of gay men] who fall in love with one another.” The objects of Molina’s desires are straight men. “What we’re always waiting for,” he says—she says?—is “a friendship or something, with a more serious person . . . with a man, of course. And that can’t happen because a man . . . what he wants is a woman.” Molina is filled with self-loathing, and unable to form any kind of real community or engage in political action, because “you see yourself in the other ones like so many mirrors, and then you start running for your life.”

Molina and Valentín’s prison cell, a filthy space of isolation surrounded by the threat of torture and execution, becomes a nearly utopian arena where identity can be transcended. The two characters live, briefly, in a world beyond the self, beyond sexuality, beyond gender, beyond language. Molina describes this as feeling like “I’m someone else, who’s neither a man nor a woman” while Valentín describes the feeling as being “out of danger.” The novel that began as a series of oppositions—gay and straight, woman and man, naïve and political, dream and reality, cursi and honest—hasn’t resolved any of its conflicts so much as called into question whether these categories, and many of the others we use to organize our lives, aren’t arbitrary, as limited as they are limiting. Among the book’s many insoluble contradictions is how it demonstrates these categories being overcome but only in a prison cell and only through a near-total deconstruction of the self. “Kiss of the Spider Woman” refuses to neatly suit any kind of political program—Puig called gay readers offended by his portrait of Molina “Stalinist queens”—instead burrowing deeper and deeper into what its author called “the struggle for human dignity.”

As with Puig’s other novels, “Kiss of the Spider Woman” requires far more work on the reader’s part than we are accustomed to, but the result is a profound imaginative and emotional investment. We have, to an extent far greater than normal, created the world of the story we are reading. We are in that jail cell with Molina and Valentín, eavesdropping on their conversations, witnessing their slow transition from antagonistic cellmates to friends to lovers to something that cannot quite be put into language. Our struggle to piece together the action of their scenes together mirrors their struggle to understand each other and, perversely, the struggle of the secret police to determine what Valentín may know about the resistance unit he has until recently been leading.

“Kiss of the Spider Woman” further confounds as it goes along. Just when you think you have a handle on it, it wriggles away and changes shape. The book begins with voices in the dark, as Molina relates the real-life 1942 film “Cat People” from memory, waxing rhapsodic in his micro-detailed descriptions of clothes, lighting, faces. Soon we learn that the two men have agreed to an experiment. To help pass the time after lights out in their cell, Molina will recount films to Valentín. These movies—there are six of them in all—form the book’s backbone. As he narrates the story of “Cat People,” Molina is expansive, romantic, and charming. Valentín is the opposite: terse, controlling, and analytical. When Molina describes the protagonist as “not thinking about the cold, it’s as if she’s in some other world, all wrapped up in herself,” Valentín responds, “If she’s wrapped up inside herself, she’s not in some other world. That’s a contradiction.” (Later, Valentín establishes the rules of their talk, demanding that Molina’s stories contain “no food and no naked girls.”) Valentín only likes the movie once he is able to interpret it in Marxist and Freudian terms. The highest praise he can offer is “it’s all so logical, it’s fantastic.” Our sympathies are drawn toward Molina. He’s the dreamer, the romantic, the sincere one, and Valentín—who studies all day and cannot even tell his girlfriend that he loves her, because the resistance needs them both more than they need each other—feels almost inhuman in his discipline, incapable of recognizing that his dream of Marxist revolution is a romantic fantasy of its own.

It is no wonder, then, that the adaptations, which reduce the story to a romance between two seeming opposites amid a backdrop of degradation and fantasy, proved so much more successful. Ultimately, however, it is the book that will survive. The musical hasn’t been produced in New York since its hit Broadway run ended in 1995, and the film today feels painfully, at times hilariously, dated. William Hurt, an often wonderful actor, was miscast as Molina. Puig had objected to Hurt, responding to his signing on to the film with “in my bed maybe, but not as Molina!” And even though Hurt won an Oscar for his performance, Puig was right. Hurt, physically too large and obviously impersonating rather than inhabiting a fabulous gay character, somehow overacts and underplays at the same time. The director, Hector Babenco, primarily known for documentaries, lacks the sense of visual style the film demands, and the movie seems embarrassed by the two men’s sexual relationship. The screenplay reduces Molina and Valentín’s affair to a one-off favor that Valentín does for Molina, and the camera cannot even show us the titular kiss between the two characters, on which the ending hinges. The film is a work of compromise, between director and stars, between screenplay and Hollywood mores, and between Puig and his pocketbook—one that reinforces the very categories that the novel sought to break down.

Unlike the movie, which feels fixed in time, the novel of “Kiss of the Spider Woman” feels timeless, or perhaps newly relevant again and again. Its meaning has already shifted for me over the decades, from a moving insistence on gay personhood to a prescient and acutely felt dramatization of how the gender binary imprisons us all. Who knows what it will mean when I revisit it again in a decade—but it will be waiting, provocative, defiant, cursi, and ready to challenge whatever boundaries we put around ourselves. ♦

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vicki Baum, the author of “Grand Hotel,” once wrote that “you can live down any number of failures, but you can’t live down a great success.” After witnessing the fall and rise of his novel “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” Manuel Puig likely would’ve agreed with her. Originally released to critical dismissal—Robert Coover called it “a rather frail little love story” in the Times—the book landed with a thud, managing to make Puig a celebrity in the gay enclave of New York City’s Christopher Street, but not much else. Yet “Kiss of the Spider Woman” had a remarkable afterlife. A play adaptation, co-authored by Puig, became an international success, and led to an Oscar-winning film starring William Hurt and Raul Julia as well as a hit musical written by John Kander, Fred Ebb, and Terrence McNally. Puig disliked the film, and, shortly after a disastrous workshop of the musical at suny Purchase, died from a heart attack, at the age of fifty-seven. Yet for all his frustration with the adaptations of his novel, they guaranteed its longevity. “Kiss of the Spider Woman” is the only book of Puig’s in English that remains steadily in print—his first novel, “Betrayed by Rita Hayworth” was recently issued for the second time this century by McNally Editions—and the cover of the Vintage International paperback boasts the same typeface and image as the playbill of the Broadway production.

The film and musical so overshadowed their source material that, when I first encountered the book, in a course called Subjectivity in Literature my freshman year of college, I thought that my eccentric professor had assigned a novelization to us as a way of challenging our assumptions about which books were worthy of study. Within a few pages, I realized my mistake. “Kiss of the Spider Woman” is a mysterious, formally inventive, beguiling work about two prisoners during the Dirty War in Argentina: a Marxist guerrilla named Valentín and a gay window dresser named Molina, who develop a transformative relationship as the latter narrates the plots of his favorite movies to the former. When I was nineteen, “Kiss of the Spider Woman” struck me as a work about finding love and preserving one’s humanity in the most inhumane of places. It is in some ways the opposite of Ariel Dorfman’s “Death and the Maiden,” a play in which the psychic scars of the Pinochet regime in Chile prove a universal solvent, dissolving any attempt at decency, or humanity, or truth. Reading the novel in the period between the passage of the Defense of Marriage Act and the repeal of sodomy laws in Lawrence v. Texas, I believed it to be a work of protest art, one that defiantly asserts Molina’s personhood even amid the Dirty War’s depredations. Reading “Kiss of the Spider Woman” today, the prison seems less like a real place, and the novel seems far trickier, and far harder to nail down to any one meaning. “Kiss of the Spider Woman” slips between different interpretations, just as its late-night conversations wander from the most frivolous of trivialities to the deepest of truths.

Puig would likely have objected to the idea that frivolity was opposed to truth. His sensibility was rooted in cursi, a word that lacks a direct English translation but is key to the consciousness that underlies his work. Cursi is the Blanche DuBois to machismo’s Stanley Kowalski, passionately insisting “I don’t want realism, I want magic!” Its closest equivalent in the United States is camp, but the two are not exactly the same. There’s a yearning to cursi, and a nostalgic fabulousness. Puig was the great twentieth-century writer of the cursi sensibility. He disdained the self-seriousness of many of his contemporaries in the Latin American Boom, particularly Gabriel García Márquez, who he felt had been ruined by critical praise. “Every sentence pretends to be the maximum phrase of all of literature,” Puig griped, about the future Nobel Prize winner’s “The Autumn of the Patriarch,” “and each one ends by weighing a ton.” Puig’s novels are deliberately playful and provocatively effeminate. They often ride the line between satire and sincerity, producing a result that is somehow both sincerely felt and heavily ironized. As Puig himself put it once in a letter, “that’s the real me: Cursi and truthful.”

“Kiss of the Spider Woman” grew out of Puig’s frustrations with the politics of his era and his contemporaries. He eschewed explicit polemic in his work, which led to his being viewed with suspicion by both the left and the right. His first novel was panned by the center-right magazine La Nacíon for using colloquial Argentinean Spanish and accused of having Peronist sympathies. Living among fellow exiled Argentinean intellectuals in Mexico City, Puig found that he “was still a reactionary for not having joined the movement. Worst of all my book had been banned by the right wing and the Argentinian left didn’t care.” From this pain, he began taking notes on a novel in which two men—one straight and one gay, who “doesn’t have much education, but a great fantasy life”—would “meet through a mediator—movies.”

Puig, who wanted to be a screenwriter and only turned to writing novels after his thirtieth birthday, all but grew up in a movie theatre. According to “Manuel Puig and the Spider Woman,” a biography of Puig by his translator and friend Suzanne Jill Levine, his home town of General Villegas, in the Argentine Pampas, had one movie house, which showed a different film every day. Beginning in 1936, his mother, Malé, with whom he would remain extremely close throughout his life, took him to see “mostly American stuff” almost daily, at 6 p.m. Staring at the screen, he fell in love with the female stars of the thirties, constructing a pantheon out of Rita Hayworth, Joan Crawford, Norma Shearer, Greta Garbo, and others. “I understood . . . the moral world of movies, where goodness, patience, and sacrifice were rewarded,” he later said. “In real life, nothing like that happened. . . . I, at a certain moment, decided that reality was what was on the screen and that my fate—to live in that town—was a bad impromptu movie that was about to end.” Malé had initially only intended to stay in General Villegas for a year and passed her frustrated dreams of cosmopolitan life down to her son. “It was like living in exile,” he would later say, and, in his first two novels, he would create a thinly veiled version of his home town, called Colonel Vallejos, and treat it unkindly.

The Puigs left Villegas, moving to Buenos Aires by 1949, and it’s unclear whether Manuel ever returned to his home town, except in his imagination. Much of his life was lived in one form of exile or another, particularly after his novel “The Buenos Aires Affair” was suppressed in Argentina in 1974.

“Betrayed by Rita Hayworth” highlights again and again the contrast between the magic of cinema and the tawdry doldrums of everyday life. Puig preferred melodramas, which he called “the language in which the unconscious speaks,” along with screwball comedies and, once he got over the trauma of seeing “Bride of Frankenstein” at too young an age, cheap horror films. In his essay “Cinema and the Novel,” Puig wrote that the films of the thirties and forties had such lasting power because they “really were dreams displayed in images. . . . When I look at what survives in the history of cinema, I find increasing evidence of what little can be salvaged from all the attempts at realism.” He disliked much of Italian neorealism and the films of Martin Scorsese (“so much pretension and slowness”), and called Meryl Streep, Ellen Burstyn, Jill Clayburgh, and Glenn Close “the Four Horsewomen of the Apocalypse” for ushering in a more realistic femininity onscreen.

Escape into the dream world of cinema was an obsessive quest. Later in life, he would write his friend Guillermo Cabrera Infante a long list of the authors of the Latin American Boom as Hollywood starlets. Borges was Norma Shearer (”Oh so refined!”), García Márquez was Elizabeth Taylor (“Beautiful face but such short legs”), Mario Vargas Llosa was Esther Williams (“Oh so disciplined (and boring)”). Among the eighteen names was Puig’s own. He was to be played by Julie Christie, a “great actress, but since she has found the right man for her (Warren Beatty) she doesn’t act anymore.” Years later, after his writing had brought him money and international acclaim, Puig would buy television sets and VCRs for friends, and then cajole them into recording classic films for him, eventually amassing a library of more than three thousand movies on upward of twelve hundred video cassettes.

Popular culture at its most cursi undergirds Puig’s work. It’s there in his titles— “Betrayed by Rita Hayworth,” “Heartbreak Tango,” “The Buenos Aires Affair,” “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” “Pubis Angelical,” “Eternal Curse on the Reader of These Pages,” “Blood of Requited Love,” “Tropical Night Falling”—which feel as if they could be printed in the most lurid of fonts, accompanied by the most sensational of exclamation points. His frustrated attempts to work as a screenwriter gave birth to his signature style, in which dialogue, stream of consciousness, and fake secondary sources like diary entries, surveillance reports, and newspaper articles bump up against one another. This marriage of high modernist experimentation with low cultural reference points and subject matter frequently led to his dismissal by Argentinean literati. He struggled for years to publish “Betrayed by Rita Hayworth,” and the accusation that he was a lightweight shadowed him even after his death. Reviewing Levine’s biography in the Times, Vargas Llosa wrote that “of all the writers I have known, the one who seemed least interested in literature was Manuel Puig,” before sniffing that “Puig’s work may be the best representative of what has been called light literature . . . an undemanding, pleasing literature that has no other purpose than to entertain.” Vargas Llosa’s estimation couldn’t be further off the mark. While Puig’s novels are entertaining—often riotously so—his formal techniques aren’t mere games, and his experimentations with dialogue still seem radical and groundbreaking decades after his death.

The novel in dialogue form is not new—authors from Diderot to Woolf and Gaddis have experimented with it—but there is something eternally transgressive in its austerity. To work only in dialogue is to limit or altogether renounce such pleasurable tools as point of view, description, free indirect discourse, and narration. Playwrights know that their dialogue will be mediated through a production, through the choices and interpretations of a director and actors, and they can leave instructions in the form of stage directions and notes explaining their intent. But the novel in dialogue forgoes all this. It forces the reader to be at once director and detective, interpreting how the lines will be spoken, and searching each sentence for clues as to the basic facts of what is going on.

“Kiss of the Spider Woman” takes place in prison, yet it is six full pages of testy back-and-forth before the reader gets any glimpse of where the story is situated.

As with Puig’s other novels, “Kiss of the Spider Woman” requires far more work on the reader’s part than we are accustomed to, but the result is a profound imaginative and emotional investment. We have, to an extent far greater than normal, created the world of the story we are reading. We are in that jail cell with Molina and Valentín, eavesdropping on their conversations, witnessing their slow transition from antagonistic cellmates to friends to lovers to something that cannot quite be put into language. Our struggle to piece together the action of their scenes together mirrors their struggle to understand each other and, perversely, the struggle of the secret police to determine what Valentín may know about the resistance unit he has until recently been leading.

“Kiss of the Spider Woman” further confounds as it goes along. Just when you think you have a handle on it, it wriggles away and changes shape. The book begins with voices in the dark, as Molina relates the real-life 1942 film “Cat People” from memory, waxing rhapsodic in his micro-detailed descriptions of clothes, lighting, faces. Soon we learn that the two men have agreed to an experiment. To help pass the time after lights out in their cell, Molina will recount films to Valentín. These movies—there are six of them in all—form the book’s backbone. As he narrates the story of “Cat People,” Molina is expansive, romantic, and charming. Valentín is the opposite: terse, controlling, and analytical. When Molina describes the protagonist as “not thinking about the cold, it’s as if she’s in some other world, all wrapped up in herself,” Valentín responds, “If she’s wrapped up inside herself, she’s not in some other world. That’s a contradiction.” (Later, Valentín establishes the rules of their talk, demanding that Molina’s stories contain “no food and no naked girls.”) Valentín only likes the movie once he is able to interpret it in Marxist and Freudian terms. The highest praise he can offer is “it’s all so logical, it’s fantastic.” Our sympathies are drawn toward Molina. He’s the dreamer, the romantic, the sincere one, and Valentín—who studies all day and cannot even tell his girlfriend that he loves her, because the resistance needs them both more than they need each other—feels almost inhuman in his discipline, incapable of recognizing that his dream of Marxist revolution is a romantic fantasy of its own.

The next movie Molina swoons over is “Destino,” a Nazi film about the evils of the French Resistance. The movie, a composite invented by Puig, is an inversion of the Hollywood film “Paris Underground,” its female protagonist rather unsubtly named Leni. Molina knows that it’s Nazi propaganda but loves it, “because it’s well made, and besides it’s a work of art.” The stage appears to be set for an extended dialogue about the relationship between art and truth, aesthetics and politics, naïveté and logic, and so on. Yet Puig shifts gears again, introducing footnotes written in parodic academese that trace a post-Freudian theory of homosexuality. The footnotes grow so extensive that they take over the book, drowning out the prisoners for pages on end. These give way to stream-of-consciousness asides that take us into Molina and Valentín’s thoughts, the former self-pitying and sentimental, the latter obsessive and fevered. The text becomes marked with ellipses to denote physical actions that would normally be described, culminating in a sex scene composed solely of the words spoken by the two men/

“Kiss of the Spider Woman” moves from an avalanche of verbiage to a space where language is inadequate, and out again, with the two characters, having physically joined their bodies, finding new selves beyond the limits of their roles. It’s not entirely clear whether, were the book written today, Molina would even be described as a man. He often identifies as a woman throughout “Kiss of the Spider Woman” and at one point says, “As for my friends and myself, we’re a hundred percent female. . . . We’re normal women; we sleep with men.” Here, Molina is contrasting his social circle with “the other kind [of gay men] who fall in love with one another.” The objects of Molina’s desires are straight men. “What we’re always waiting for,” he says—she says?—is “a friendship or something, with a more serious person . . . with a man, of course. And that can’t happen because a man . . . what he wants is a woman.” Molina is filled with self-loathing, and unable to form any kind of real community or engage in political action, because “you see yourself in the other ones like so many mirrors, and then you start running for your life.”

Molina and Valentín’s prison cell, a filthy space of isolation surrounded by the threat of torture and execution, becomes a nearly utopian arena where identity can be transcended. The two characters live, briefly, in a world beyond the self, beyond sexuality, beyond gender, beyond language. Molina describes this as feeling like “I’m someone else, who’s neither a man nor a woman” while Valentín describes the feeling as being “out of danger.” The novel that began as a series of oppositions—gay and straight, woman and man, naïve and political, dream and reality, cursi and honest—hasn’t resolved any of its conflicts so much as called into question whether these categories, and many of the others we use to organize our lives, aren’t arbitrary, as limited as they are limiting. Among the book’s many insoluble contradictions is how it demonstrates these categories being overcome but only in a prison cell and only through a near-total deconstruction of the self. “Kiss of the Spider Woman” refuses to neatly suit any kind of political program—Puig called gay readers offended by his portrait of Molina “Stalinist queens”—instead burrowing deeper and deeper into what its author called “the struggle for human dignity.”

It is no wonder, then, that the adaptations, which reduce the story to a romance between two seeming opposites amid a backdrop of degradation and fantasy, proved so much more successful. Ultimately, however, it is the book that will survive. The musical hasn’t been produced in New York since its hit Broadway run ended in 1995, and the film today feels painfully, at times hilariously, dated. William Hurt, an often wonderful actor, was miscast as Molina. Puig had objected to Hurt, responding to his signing on to the film with “in my bed maybe, but not as Molina!” And even though Hurt won an Oscar for his performance, Puig was right. Hurt, physically too large and obviously impersonating rather than inhabiting a fabulous gay character, somehow overacts and underplays at the same time. The director, Hector Babenco, primarily known for documentaries, lacks the sense of visual style the film demands, and the movie seems embarrassed by the two men’s sexual relationship. The screenplay reduces Molina and Valentín’s affair to a one-off favor that Valentín does for Molina, and the camera cannot even show us the titular kiss between the two characters, on which the ending hinges. The film is a work of compromise, between director and stars, between screenplay and Hollywood mores, and between Puig and his pocketbook—one that reinforces the very categories that the novel sought to break down.

Unlike the movie, which feels fixed in time, the novel of “Kiss of the Spider Woman” feels timeless, or perhaps newly relevant again and again. Its meaning has already shifted for me over the decades, from a moving insistence on gay personhood to a prescient and acutely felt dramatization of how the gender binary imprisons us all. Who knows what it will mean when I revisit it again in a decade—but it will be waiting, provocative, defiant, cursi, and ready to challenge whatever boundaries we put around ourselves. ♦

1 note

·

View note

Text

Birthdays 5.6

Beer Birthdays

Bernard "Toots" Shor; saloonkeeper (1903)

Five Favorite Birthdays

George Clooney; actor (1961)

John Flansburgh; pop musician, "TMBG" (1960)

Willie Mays; San Francisco Giants CF (1931)

Anne Parillaud; actor (1960)

Orson Welles; film director, actor (1915)

Famous Birthdays

Paul Alverdes; German writer (1897)

Nestor Basterretxea; Spanish artist (1924)

Charles Batteux; French philosopher (1713)

Raymond Bailey; actor (1904)

Tom Bergeron; television host (1955)

Tony Blair; British politician (1953)

Susan Brown; English actor (1946)

Geneva Carr; actor (1971)

Jeffery Deaver; writer (1950)

Willem de Sitter; Dutch scientist (1872)

Robert H. Dicke; physicist and astronomer (1916)

Ariel Dorfman; Argentinian writer (1942)

Roma Downey; actor (1960)

Sigmund Freud; psychiatrist (1856)

Jimmie Dale Gilmore; country singer (1945)

Stewart Granger; English-American actor (1906)

Dana Hill; actor (1964)

Amy Hunter; actor and model (1966)

Ross Hunter; actor (1926)

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner; German-Swiss artist (1880)

Paul Lauterbur; chemist (1929)

Kal Mann; songwriter (1917)

Harry Martinson; Swedish writer (1904)

Lars Mikkelsen; Danish actor (1964)

Christian Morgenstern; German writer (1871)

Motilal Nehru; Indian politician (1861)

Martha Nussbaum; philosopher (1947)

Michael O'Hare; actor (1952)

Adrianne Palicki; actor (1983)

Robert Peary; arctic explorer (1856)

Marguerite Piazza; actor (1920)

Gina Riley; Australian actor (1961)

Maximilian Robespierre; French revolutionary (1758)

Tony Scalzo; pop singer (1964)

Bob Seger; rock musician (1945)

Rolf Maximilian Sievert; Swedish physicist (1906)

Randall Stout; architect (1958)

Jean-Baptiste Stuck; Italian-French composer (1680)

Rabindranath Tagore; Indian writer (1861)

James Turrell; artist (1943)

Rudolph Valentino; actor (1895)

Adrienne Warren; actor (1987)

Andre Weil; French mathematician (1906)

Theodore H. White; historian and writer (1915)

Lynn Whitfield; actor (1953)

Wally Wingert; actor (1961)

Jaime Winstone; English actor (1985)

Denny Wright; English guitarist (1924)

Raquel Zimmermann; Brazilian model (1983)

0 notes

Text

Week 7: Digital Citizenship and Health Education: Body Modification on Visual Social Media

Recently social media started to grow more and more, creating lots of platforms to serve as a dynamic space for self-expression, creating a connection between users and sharing tons of information. Thanks to the emergence of social media and digital technology has been associated with a shift in the nature of labor, as well as the popularization of pornography and the "porn chic" look (Drenten, 2020). In addition, body modification also started to rise up among influencers and celebrities to improve their appearance on social media, gain more view and popularity. Furthermore, according to the 2017 data provided by the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 42% of surgeons said that their patients are pursuing aesthetic surgery to enhance their image on Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and other networks (Dorfman, 2018). Beside that, body modification and pornography by sexualizing self-looking is a way marketing utilize to promote product. Celebrity and influencers apply the body modification and expose themselves to their social media to gain more following and potentially attract some advertisement. Influencer labor based on affiliation aims to attract and retain the interest of an external business by engaging in fun and sexually provocative interactions with followers on social media who are activated by increasingly subtle digital affordances (Drenten, 2020). In addition, with body modification, change their appearance and look to create an image that boosts more popularity to the influencer and brand advertise. However, by over doing plastic surgery, modification to the body can create some long-term harmful effects to health and therefore it’s a risky beauty treatment to gain popularity. As social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook continue to rise more, influencers and celebrities from around the will continue to pornified and show their body modification to gain attention and attract advertisers. It is important to remind people to educate themselves more about what is the long-term impact of body modification to avoid any unfortunate.

Reference:

Drenten, J, Gurrieri, L & Tyler, M 2020, “Sexualized labour in digital culture: Instagram influencers, porn chic and the monetization of attention,” Gender, work, and organization, vol. 27, no. 1, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford, pp. 41–66.

Robert G Dorfman, Elbert E Vaca, Eitezaz Mahmood, Neil A Fine and Clark F Schierle, ‘Plastic Surgery-Related Hashtag Utilization on Instagram: Implications for Education and Marketing’, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 38, Issue 3, March 2018, pp 332–338

0 notes

Text

guthrie theater tiktok full of choreography: "In the rehearsal room for LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS! 🌱 Fun is being had, songs are being sung, human eating plants are being grown."

#lsoh#some fight choreo like orin dentist role doesn't sing at any point before he does surely but i'm only so familiar in various ways#enough to go well this isn't a lsoh song but from there i wouldn't have a clue. told us in their tags though like oh okay then#the unenthusiastic backup he's getting lol#guessing that's a plant standing Objet. thought someone was standing in for it even more but think they're standing right Behind it#go actor robert dorfman....#will roland#seymour krelborn

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animal House (1978)

National Lampoon’s Animal House is an important movie. You can see its influence in the many raunchy and gross-out comedies that attempted to ride on its coattails after its release. Countless films have either imitated its style or attempted to one-up its hijinks. It’s unapologetically vulgar and crass, memorable and often hilarious. It’s also horribly dated - we’re talking Breakfast at Tiffany’s dated - which makes it hard to recommend unless you’re from a certain era, or watching it for academic reasons.

In 1962, Faber College’s Dean Vernon Wormer (John Vernon) is fed up with the Delta Tau Chi "Animal House" Fraternity. It isn’t hard to see why. Its members are nothing but hard-partying, womanizing delinquents with low grade point averages and a knack for disobedience - unlike the prestigious, snooty, elitist Omega Theta Pi house, who hate them just as much as the Dean does.

Animal House doesn't have much of a plot. For 109 minutes, we follow various members of the fraternity as they go wild. New pledges Larry Kroger (Tom Hulce) and Kent Dorfman (Stephen Furst), the legendary John "Bluto" Blutarsky, motorcyclist/mechanic Daniel Simpson "D-Day" Day (Bruce McGill), chapter president Robert Hoover (James Widdoes), ladies’ man Eric "Otter" Stratton (Tim Matheson), and the only one with a steady girlfriend, Donald "Boon" Schoenstein (Peter Riegert) all go on the kind of adventures that you can’t believe someone committed to film in 1978. It’s essentially a series of sketches, many of which you see once and never forget. That's not necessarily a bad thing. I just need to say “the horse” and you start to crack up.

While the film doesn’t contain the kind of rampant misogyny many of its imitators attempted to mine for comedy (such as Porky’s)… it’s still got a problematic attitude towards women. If it were just one scene of Bluto peeking through a window to see ladies changing, it might be ok. The college students we see are all parading in their underwear while having a pillow fight, which is so outlandish it's funny. The problem is how many moments of this nature we see. Animal House has a scene in which a character has to seriously consider why having sex with an unconscious woman is a bad idea. It’s one rape joke too many but then there's another not too far away. Yikes.

I can’t blame anyone who gets offended at the homophobic jokes - all I can say is that’s just the way things were back then - or the racist jokes - times were different but things have changed, I swear. Even if you overlook them, the picture’s general attitude just doesn’t sit well today. You might not like the snobs in Omega Theta Pi but at least they’re good students. Animal House is filled with cheaters who take nothing seriously and then complain when the administration holds them accountable. Maybe fraternities mean a different thing in the United States than they do in Canada, or they were a bigger deal back in the day but it's hard to figure out why you should like the hooligans from Animal House at the end of the day.

If you’re curious and undeterred by the dated humor, there are plenty of funny gags and several of them produce big laughs. I just don’t know who this movie is for anymore. You’d have a difficult time looking at your female friends in the face after watching this film with them. With your kids? They’d be appalled. Even among your buddies, I suspect you’d find a larger-than-expected number of them who’d go “Hey man, this isn’t cool”. I'm glad I saw Animal House. Now that I have, I understand why the film was as influential as it was but I doubt I'll feel the need to revisit it. This makes me unsure if I recommend it or not. I suppose I do, if you know what you're getting into, at least so you can "get it" too. (On Blu-ray, July 23, 2021)

#Animal House#movies#films#movie reviews#film reviews#John Landis#Harold Ramis#Douglas Kenney#Chris Miller#John Belushi#Tim Matheson#John Vernon#Verna Bloom#Thomas Hulce#Donald Sutherland#1978 movies#1978 films

0 notes

Text

Week 9 – Digital Citizenship and Health Education: Body Modification on Visual Social Media

What a fun topic to talk about! This was the topic that I presented in class this week and it was by far the most interesting topics I’ve talked about. It is on Body Modification on Visual Social Media!

I am sure the first thing that comes into your head is “photoshop edits” or “cosmetic surgery”. Well, yes. Those are all part of this week’s topic. Before we dive deeper into this topic, here is a brief introduction of what the topic actually means.

Body modification on visual social media refers to the practice of sharing and showcasing various alterations made to the human body on platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, or YouTube. It encompasses a wide range of intentional modifications, including but not limited to tattoos, piercings, scarification, hair dyeing, body painting, cosmetic surgeries, and even more extreme alterations like implants or extreme body modifications. In addition, body modification can also be done digitally through Photoshop apps. One can alter their appearance which includes modifying body shape, size, skin tone, facial features, or adding elements like tattoos, piercings, all through an app.

Plastic surgery is one of the most well-known and widely practiced methods of body modification. Plastic surgery involves surgical procedures that alter or enhance a person's physical appearance. It can be performed for various reasons, including reconstructive purposes to correct deformities or injuries, or for aesthetic purposes to enhance specific features or achieve a desired look. Some popular procedures of plastic surgery include breast augmentation, rhinoplasty, liposuction, facelifts, tummy tucks, and buttock augmentation, among others. The realm of plastic surgery is now completely surrounded by the Internet and social media (Robert 2018). According to a study conducted by Vardanian et al (2013) more than half of American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) members who participated in a survey reported using social media for either personal or professional reasons. Furthermore, 42% of surgeons claim that their patients want aesthetic surgery to enhance their looks on Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, and other social media platforms (American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2017).

Through this data, it illustrates the extent to which social media can cause someone to feel self-conscious or insecure about their appearance and to desire plastic surgery. Social media platforms often promote and perpetuate unrealistic beauty standards through edited and filtered images. Seeing flawless and heavily edited photos can create a sense of inadequacy and make individuals feel that their natural appearance is not good enough. I can relate to this statement too because I used to go through something similar. In addition to this, Instagram has established itself as a leading platform for businesses seeking to promote to millennials, and its use in cosmetic surgery is on the rise. Many surgeons used Instagram as a tool for patient education and company growth quickly, and as a result, many now have sizable (Falzone 2016). In my opinion, this can be classified as social media misuse as it is causing plastic surgery to become more widespread as society advances. People may become more self-conscious about their appearance as a result and undergo plastic surgery right away with easy access.

All in all, the decision to undergo plastic surgery should be a personal one, driven by a genuine desire for self-improvement and an understanding of the potential risks and benefits involved. Loving the way we look involves a combination of self-acceptance, self-care, and making choices that align with our personal values and well-being. My advice would be to love yourself because you are perfectly imperfect just the way you are. You are YOU and that is what makes you special <3

References

Dorfman, RG, Vaca, EE, Mahmood, E, Fine, NA and Schierle, CF 2018, ‘Plastic Surgery-Related Hashtag Utilization on Instagram: Implications for Education and Marketing’, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 332–338.

Falzone, D 2016, Plastic surgery docs use Instagram stars to boost their practices, Fox News, viewed 12 June, <https://www.foxnews.com/entertainment/plastic-surgery-docs-use-instagram-stars-to-boost-their-practices>.

Vardanian, AJ, Kusnezov, N, Im, DD, Lee, JC and Jarrahy, R 2013, ‘Social Media Use and Impact on Plastic Surgery Practice’, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, vol. 131, no. 5, pp. 1184–1193

0 notes

Text

Week 7: Digital Citizenship and Health Education: Body Modification on Visual Social Media

In this week’s lecture I found a couple interesting points. I learnt about the idea of pornification on social media as well as online retail stores such as Fashion Nova. It has been argued that women present a highly sexualised version of themselves online to gain more traction and attention. It has been brought to my attention that these are conformances to heteronormative notions of attractiveness – which would essentially be them appealing to the male gaze. I have always noticed how sexualised some influencers pose and present themselves but have never made the link to the aesthetics of commercialised pornography. This does make sense to me now as the notion of ‘sex sells’ has been around for so long.

This does not just refer to the way that they pose, but as well as the body modifications that both men and women undergo to make themselves appear more ‘attractive’. For women this can include

- Bigger lips

- Slimmer jaw

- Higher cheekbones

- Smaller waist and large buttocks.

For men, they find themselves enhancing their lips, as well as enhancing their jaw line to be stronger and more well-defined.

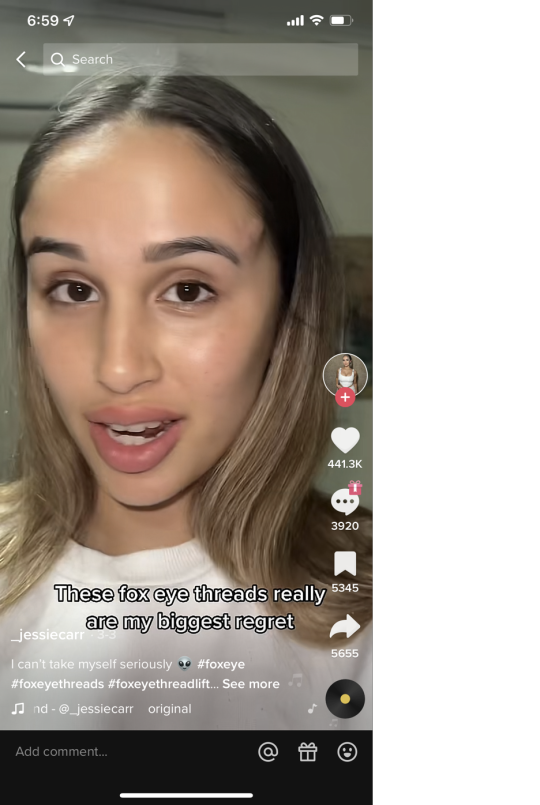

After the big trend of receiving body modifications, I have recently noticed a lot of individuals who had undergone work finding that they regret having it done or had been botched by their plastic surgeons. For women in particular, I had noticed a big trend of receiving Brazilian butt lifts, filler in the face and fox eye lifts, to name a few. Specifically, I had engaged with a user on Tik Tok, @_jessiecarr, who had received fox eye threads but ended up having swollen temples causing her to resemble the alien emoji. She has now had them removed and claims it is her biggest regret.

I do not find this surprising, as stated in the reading ‘Plastic Surgery-Related Hashtag Utilization on Instagram: Implications for Education and Marketing’ (Robert G Dorfman, Elbert E Vaca, Eitezaz Mahmood, Neil A Fine and Clark F Schierle), board certified plastic surgeons are underrepresented amongst physicians posting top plastic surgery related content on Instagram. The most top posted videos are amongst individuals who are not board-certified getting it done themselves and promoting other to do the same. This is unhealthy as there is not much education on the implications and harm that these procedures can cause, resulting in higher risk for patients looking to receive these procedures. It is important to be aware of the risks and lack of safety for patients, seeking these procedures from physicians who are not board-certified.

It is very important to be mindful and critical of the sociological and psychological consequences of social media campaigns that promote a specific body type.

References:

Robert G Dorfman, Elbert E Vaca, Eitezaz Mahmood, Neil A Fine and Clark F Schierle, ‘Plastic Surgery-Related Hashtag Utilization on Instagram: Implications for Education and Marketing’, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 38, Issue 3, March 2018, pp 332–338

0 notes

Text

Body Modification on Visual Social Media

Just as every workplace has significant and distinct aesthetic templates, sometimes more specific and professional than others, social media is also said to have such popular aesthetic templates. Ever since the introduction of the concept ‘microcelebrity’ on social media, those aesthetic templates have been looking absolutely recognizable so far. Microcelebrity is defined as a new form of identity that is linked almost exclusively to online spaces (Senft, 2012). These ‘celebrities’ rely heavily on their visibility on social media to build a specific brand of products or even themselves, thus adhering to using aesthetic templates to highlight one or both of them. In social media posts by several well-known microcelebrities, such as Kylie Jenner, or Kim Kardashian, it is not hard to point out certain poses, movements that emphasize the curves and body parts of them, which not only normalize pornification but also promote unhealthy body images. Not just one or two, but many influencers and so-called microcelebrities are openly sharing images of themselves photoshopped and posed in a way that makes them look more ‘slim’, ‘tall’, have brighter skin, etc. Many women look up to this type of body image wanting to have similar body types, or body parts, such as lashes, brows, lips, cheekbones. Therefore, image or video-based social media platforms such as Instagram and Tiktok are the destinations for many young women to find ‘inspiring’ images for body modification, without consulting a real doctor or even considering if that body is achievable in real life. Evidence suggests that before their consultation, more plastic surgery patients are looking for health-related information online and on social media. A lot of teenage girls and young female adults are said to have body dysmorphic disorder by constantly comparing themselves to aspiring body image (and actually fake) on the internet, as well as lots of them might even be underrepresented in commercials and branding that it’s hurtful and create hatred towards themselves.

Senft, T.M., 2013. Microcelebrity and the branded self. A companion to new media dynamics, pp.346-354.

Duffy BE and Meisner, C 2022. “Platform governance at the margins: Social media creators’ experiences with algorithmic (in)visibility,” Media, Culture & Society. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437221111923

Robert G Dorfman, Elbert E Vaca, Eitezaz Mahmood, Neil A Fine and Clark F Schierle, ‘Plastic Surgery-Related Hashtag Utilization on Instagram: Implications for Education and Marketing’, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 38, Issue 3, March 2018, pp 332–338

0 notes

Text

My data below the cut if you want to peak :)

20+

Larry Gelbart- S1-4, Drafted 1 year WWII

Lawrence Marks- S1-3+6, No Data

Jim Fritzell- S3-6, No Data

Everett Greenbaum- S3-6, Navy Pilot WWII

11-19

Alan Alda- S1,2,5-11, ROTC/Reserves

Gene Reynolds- S2+4+5+8, Navy WWII

Ken Levine- S5-8, Yes

David Isaacs- S5-8, Yes

Dennis Koenig- S8-11, No Data/Probably No

Thad Mumford- S8-11, No

Dan Wilcox- S8-11, Probably No

David Pollock- S9-11, No Data/Probably No

Elias Davis- S9-11, No Data/Probably No

6-10

Robert Klane- S1-3, No Data

Simon Munter- S3-4, No Data

Burt Prelutsky- S4-6, No Data

Larry Balmagia- S6,7,11, No Data

Ronny Graham- S6-8, Yes, WWII

John Rappaport- S8-11, No Data/Probably No

Karen Hall- S9-11, No

2-5

Burt Styler- S1, Yes, WWII D-Day

Hal Dresner- S1, No Data

Jerry Mayer- S1,2, No Data

Karl Kleinschmitt- S1,2 No Data

McClean Stevenson- S1,2, Yes, Navy Corpsman 46-7

Sheldon Keller- S1,2, Yes, Signal Corps WWII Pacific

Sid Dorfman- S1-5, No Data

Linda Bloodworty- S2-5, No

Mary Kay Place- S2,3, No

John W Regier- S2-4, No Data

Gary Markowitz- S2,4,5,7, No Data

Bernard Dilbert- S2,7, No Data

Erik Tarloff- S2,7,9, No Data

John D Hess- S3-5, Yes, WWII

Jay Folb- S4,5, No Data

Allan Katz- S5, No Data

Don Reo- S5, No Data

Bill Idolson- S5,6, Yes, Navy Pilot WWII

Mitch Markowitz- S7, No

Tom Reeder- S7, No Data

Sheldon Bull- S7,9, No Data

Burt Metcalfe- S7,9,11, Yes, Navy 56 2 years

Jim Mulligan- S8, No Data

Mike Farell- S8,9,11, Yes, Marines 57-59

Paul Perlove- S10, No Data

I was talking about shift in tone between early and later seasons of MASH and I wondered if it was because of the writers own experiences. So I made a list of every writer who wrote 2 or more episodes of MASH then did my best to find out who had served in the military. The results did not exactly confirm the hypothesis, but I thought they were interesting.

69 notes

·

View notes