#restaurant in stafford

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Top Restaurants in Stafford for Indian Food Enthusiasts

Indian cuisine is celebrated for its diverse flavors and rich culinary traditions. It offers a wide array of dishes that cater to various tastes. In Stafford, Indian restaurant in Stafford have become popular spots for food enthusiasts. They provide an opportunity to explore the vibrant and aromatic world of Indian cooking. From spicy curries to flavorful biryanis, there is something for everyone.

The Growing Popularity of Indian Restaurants in Stafford

In recent years, the number of Indian restaurants in Stafford has increased significantly. This growth reflects the rising interest in Indian food among locals and visitors. The unique flavors and cooking techniques have captivated many. As a result, Stafford has become a hub for Indian cuisine, offering a variety of dining options for those seeking authentic experiences.

Ambiance and Atmosphere

The ambiance of an Indian restaurant is essential to the dining experience. Many Indian restaurants in Stafford feature traditional decor that showcases the cultural heritage of India. Colorful fabrics, intricate artwork, and soft lighting create a warm and inviting atmosphere. This setting enhances the enjoyment of the meal and makes it a perfect place for gatherings with family and friends.

Must-Try Dishes

When visiting Indian restaurants, certain dishes are essential to try. Popular options include Chicken Tikka Masala, Lamb Rogan Josh, and Vegetable Samosas. Each dish is prepared with a unique blend of spices that highlight the flavors of the ingredients. Vegetarian and vegan options are also widely available, ensuring that everyone can find something delicious to enjoy.

The Role of Spices in Indian Cooking

Spices are the cornerstone of Indian cuisine. They not only add flavor but also offer health benefits. Common spices used in Indian cooking include turmeric, cumin, and garam masala. Indian restaurants in Stafford pride themselves on using authentic spices to create traditional flavors. The careful selection and combination of spices are what make Indian food so distinctive and enjoyable.

Catering to Different Dietary Needs

One of the appealing aspects of Indian cuisine is its ability to cater to various dietary preferences. Many Indian restaurants in Stafford offer a range of vegetarian, vegan, and gluten-free options. This inclusivity ensures that everyone can enjoy the rich flavors of Indian food. Chefs are often willing to customize dishes to accommodate specific dietary restrictions, making dining a pleasant experience for all.

Exceptional Customer Service

Indian restaurants are known for their hospitality. The staff in Stafford's Indian restaurants are typically friendly and attentive. They strive to create a welcoming environment for diners. Whether it's recommending dishes or accommodating special requests, the emphasis on customer service enhances the overall dining experience. Guests often leave feeling valued and appreciated.

Takeaway and Delivery Services

In today's fast-paced world, many Indian restaurants in Stafford offer takeaway and delivery services. This convenience allows customers to enjoy their favorite dishes at home. The packaging is designed to keep the food fresh and flavorful. Delivery options ensure that the culinary delights of Indian cuisine are accessible to everyone, even those who prefer dining in the comfort of their homes.

Popular Indian Restaurants in Stafford

Several Indian restaurants in Stafford stand out for their exceptional food and service. Each restaurant offers a unique menu and dining experience. Some popular choices include The Spice Lounge, known for its vibrant atmosphere and extensive menu, and The Indian Kitchen, which focuses on traditional recipes and flavors. These restaurants are favorites among locals and visitors alike.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Stafford is home to a variety of Indian restaurants that cater to food enthusiasts. With their rich flavors, inviting ambiance, and exceptional service, these establishments provide an unforgettable dining experience. Whether you are a fan of traditional Indian dishes or looking to explore new flavors, Stafford's Indian restaurants have something to offer for everyone. The culinary journey through Indian cuisine is sure to leave a lasting impression on your taste buds.

0 notes

Text

Nepali Restaurant In Stafford | 34 | Ayo Gorkhali

"Aayo Gorkhali" is a best restaurant in Stafford, UK, celebrated for its extensive and diverse menu that captures the essence of Nepali cuisine. Named in honor of the legendary Gorkha soldiers, "Aayo Gorkhali" offers a warm and inviting atmosphere where guests can enjoy an authentic culinary experience.

Menu Highlights

Starters

Momo: Traditional Nepali dumplings filled with minced meat or vegetables, served with a spicy tomato chutney.

Chhoila: Spicy grilled meat, typically chicken or buffalo, marinated in Nepali spices and served with beaten rice (chiura).

Aloo Tama: A savory soup made with bamboo shoots, potatoes, and black-eyed peas, flavored with Nepali spices.

Main Course

Dal Bhat: Steamed rice (bhat) served with lentil soup (dal), accompanied by vegetable curries, pickles, and sometimes meat.

Thakali Thali: A traditional platter including rice, lentils, seasonal vegetables, gundruk (fermented leafy greens), and a choice of meat.

Sekuwa: Skewered and grilled meat, marinated with herbs and spices, often served with achar (pickle) and beaten rice.

Sea Foods

Fish Curry: Fresh fish cooked in a flavorful Nepali curry sauce with spices and herbs.

Prawn Bhuteko: Stir-fried prawns with Nepali spices, onions, tomatoes, and bell peppers.

Tandoori Dishes (Clay Oven)

Tandoori Chicken: Marinated chicken cooked in a traditional clay oven, offering a smoky and tender flavor.

Lamb Seekh Kebab: Ground lamb mixed with spices and herbs, shaped onto skewers, and cooked in the clay oven.

Paneer Tikka: Cubes of paneer cheese marinated in spices and grilled to perfection.

Kids Menu

Chicken Nuggets and Chips: A child-friendly option with crispy chicken nuggets and fries.

Mini Momo: Smaller portions of the traditional Nepali dumplings, tailored for kids.

Cheese Naan Pizza: A fusion dish combining cheese naan with pizza toppings.

Side Dishes

Saag: Stir-fried spinach with garlic and spices.

Aloo Gobi: Potatoes and cauliflower cooked with turmeric, cumin, and coriander.

Papadum: Crispy lentil wafers served with chutney.

Naan and Roti

Garlic Naan: Soft bread flavored with garlic and baked in the clay oven.

Butter Roti: Whole wheat flatbread brushed with butter.

Cheese Naan: Naan stuffed with melted cheese.

Rice

Plain Rice: Steamed white rice.

Jeera Rice: Basmati rice flavored with cumin seeds.

Peas Pulao: Rice cooked with green peas and mild spices.

Biryani

Chicken Biryani: Fragrant rice cooked with marinated chicken, spices, and herbs.

Lamb Biryani: Aromatic rice dish with tender lamb pieces and a blend of spices.

Vegetable Biryani: A vegetarian version with mixed vegetables and flavorful rice.

Nepali Chow-Chow

Vegetable Chow-Chow: Stir-fried noodles with mixed vegetables and Nepali spices.

Chicken Chow-Chow: Noodles stir-fried with chicken and vegetables.

Prawn Chow-Chow: Noodles with stir-fried prawns and a mix of vegetables.

Sauces

Tomato Chutney: A spicy and tangy sauce made from tomatoes and spices.

Mint Yogurt Sauce: A cooling sauce with yogurt and fresh mint.

Tamarind Sauce: A sweet and tangy sauce made from tamarind pulp.

Hospitality

The staff at Aayo Gorkhali are known for their warm hospitality and attentive service, ensuring every guest feels welcome and valued.

Community and Culture

Aayo Gorkhali serves as a cultural hub for the Nepali community in Stafford, frequently hosting cultural events, music nights, and festivals to celebrate and share Nepali heritage.

In summary, Aayo Gorkhali in Stafford, UK, offers a comprehensive menu that caters to a variety of tastes and preferences. Whether you're looking to explore traditional Nepali dishes, enjoy flavorful tandoori items, or find kid-friendly options, the restaurant promises an authentic and delightful dining experience.

0 notes

Text

Fun with Fics

Rules: Pick any ten of your fics, scroll roughly to the midpoint, pick a line (or three) and share it. Then tag ten people.

(I got this twice in my inbox, so here goes.)

1. The Wine Is Not Enough

Sam leaned forward and offered Dany some unsolicited wisdom, “Never, ever wear open-toed sandals in a Port-o-Walder.”

2. The Seduction

Jaime lunged forward and pressed his mouth to hers in a sloppy, wet kiss. He pulled back and began kicking off his shoes. "Fine. See. You've won. I yield. You can have your way with me."

3. Vows

He shifted on the bed to lean back against the pillows, angling himself to her. “I left you unprotected in the North. Did that Wildling try to steal you? Did you let him?” His eyes glittered with something she didn’t understand. “Is that why you’re trying to refuse me?”

“No one stole me. Why would anyone even try? I’m not a possession to be stolen,” she huffed.

4. Age Gap

“Seriously though, Tyrion, what’s the point in having a sexy young girlfriend if I can’t have her hold up restaurant menus to prove I can read them from a distance?”

5. The Right Time

He rose from his seat and turned around, facing the bear-like man. With a deliberate swipe of his stump, he knocked the unopened cup to the floor before leaning his perfect muscular backside against the edge of her desk. His voice was like shards of ice as he spoke to the investigator. “Brienne already has plans for lunch. With me.” He then stood straight and took a step closer to the other man. “She has plans today. Tomorrow. Every lunch. Every day. Every dinner, too.”

6. Life's Sweetest Reward

Brienne shoveled a bite of eggs in her mouth and swallowed before answering. “Shuffleboard tournament.” After watching the other couples at parasailing yesterday, she thought she and Jaime were probably the most athletic ‘couple’ on board. “If Jaime manages to get up in time, we’ll likely win.”

Howland drew back from her and his previous affable expression turned into something much harder. Jyana touched his hand, a look of alarm on her face.

“Jya and I have been on ninety-seven cruises. We compete in the shuffleboard tournament every single time.” He leaned in then, his voice dark and low, “And we always win.”

7. The Kingslayer's Speech

No matter how she argued that the first kiss had been an accident, (did you trip and fall into my lips, wench?), he had insisted that he was entitled to a kiss with every goodbye now. It was his due, he said. Just to shut him up, she’d smacked her lips against his and sent him on his way.

8. The Singular Discomfort of Jaime Lannister

He hadn’t thought it possible to be this hard and not explode. “Are you,” he paused, needing to catch his breath, “are you asking me to tell you about the hot, dirty things I want to do to you?”

9. Everyone Has a Price

Aunt Myranda (wife of Stafford, mother of Daven, Cerenna and Myrielle), passed around tequila shots while discussing the benefits of erectile dysfunction medication, but the drawbacks of four-hour erections.

10. Words in the Dark Night

“Or I could warm it on your teats, what little you have, wench. Or perhaps under the sweet curve of your ass.”

Sam watched as the Maid’s gloved hand gripped the hilt of Oathkeeper. He wondered if Ser Jaime planned to die tonight.

----

Okay..this was a lot of fun. Thank you. I haven't double checked all the links, but you can find all my fics by just clicking one and then my user name. I can't always connect writers to tumblrs, so I'm going with the first few I remember. @ddagent @writergirl2011 @seaspiritwrites @glamaphonic @isolacaramella @quizzicalquinnia @ladym-rules @wackygoofball @wildlingoftarth @bussdowntarthiana

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seeing as I am not allowing myself to continue playing the Johanssons until I have bought Lovestruck - well, I went and created another family!

Meet the Stafford-Price family!

I consists of Anna Stafford (22 years old) and Diane Price (20) , their daughter Elaine (just turned 1) and dog Chiquito.

Anna and Diane knew each other when they were kids, back in Henford-on-Bagley. Anna's family still live there but Diane's mum moved after few years. Diane doesn't know her dad and joined her mum on her different moves and adventures (she lived mostly in San Myshuno).

Diane's mum eventually bought a house in Tomarang and she and Diane used it as a sort of vacation home.

In the meantime, Anna grew up in Henford-on-Bagley with her family, growing crops and tending to animals. However, she was always better in the kitchen than in the garden. She moved out a few year's ago to start working at a restaurant in San Myshuno, ran into Diane and they reconnected.

Realizing that they wanted to be together they quickly ended up with a baby, a dog and Diane's 'vacation home' - given to them by Diane's mum.

Diane's mum still lives in San Myshuno (when not travelling) but comes visiting now and then.

The girls do find family life a bit overwhelming, but hopefully they'll find a balance between being responsible adults and still only in their 20's!

I will probably post them a little, they have been great fun to play even if I have hardly played even their first week. We'll see if I play them all the way to elder-hood!

Stats - and their house - under the cut!

Anna and Diane aren't a complete match, and they will have to work on their relationship if it's going to hold all the way to retirement. Anna wants to work with food (her LTW is eventually changed as she starts to open a food stall) and Diane is a blogger!

Elaine is a very sweet baby and Chiquito is a silly dog <3

I also put their home up at the gallery. The gallery version is very basic - mainly walls/layout and some furniture. I tried not to use CC, don't know if I managed?

Anyway - we all love a spacious one-floor home so here it is! Made for a family that loves to be outdoors; there's a pool, there's a garden and there is room for outdoor play for the kids!

Fin it in the gallery, it's called Ro Kaya Rockside rebuild, my ID is kusin_tisdag!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

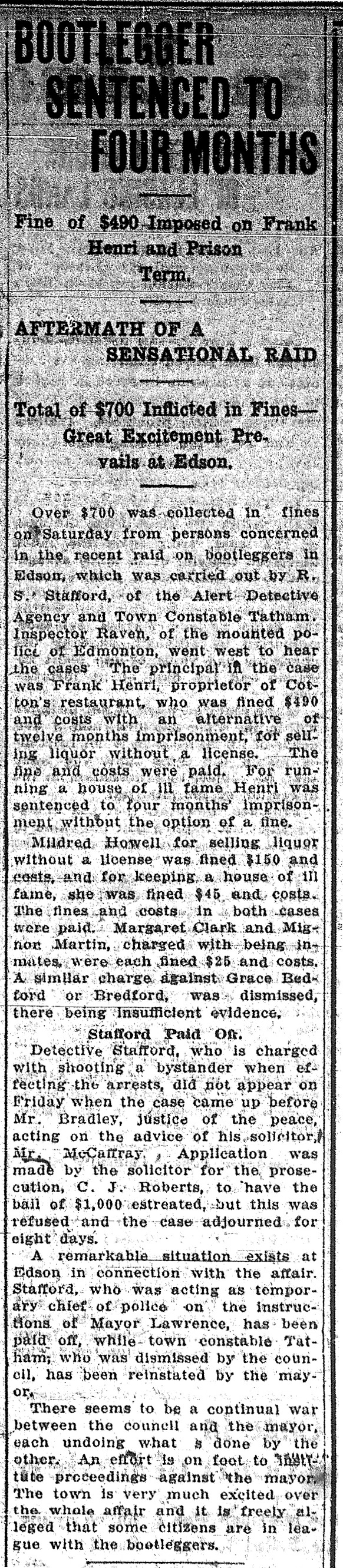

"BOOTLEGGER SENTENCED TO FOUR MONTHS," Edmonton Bulletin. March 4, 1913. Page 5. ---- Fine of $490 Imposed on Frank Henri and Prison Term. ==== AFTERMATH OF A SENSATIONAL RAID === Total of $700 Inflicted in Fines - Great Excitement Prevails at Edson. --- Over $700 was collected in fines on Saturday from persons concerned in the recent raid on bootleggers in Edson, which was carried out by R. S. Stafford, of the Alert Detective Agency and Town Constable Tatham. Inspector Raven, of the mounted police of Edmonton, went west to hear the cases. The principal in the case was Frank Henri, proprietor of Cotton's restaurant, who was fined $490 and costs with the alternative of twelve months imprisonment, for selling of liquor without a license. The fine and costs were paid. For running a house of ill fame Henri was sentenced to four months' imprisonment without the option of a fine.

Mildred Howell for selling liquor without a license was fined $150 and costs, and for keeping, a house of ill fame, she was fined $45, and costs. The fines and costs in both cases were paid. Margaret Clark and Mignor Martin, charged with being inmates, were each fined $25 and costs. A similar charge against Grace Bedford or Bredford, was dismissed, there being insufficient evidence.

Stafford Paid On. Detective Stafford, who is charged with shooting a bystander when effecting the arrests, did not appear on Friday when the case came up before Mr. Bradley, justice of the peace, acting on the advice of his solicitor, Mr McCaffray. Application was made by the solicitor for the prosecution, C. J. Roberts, to have the bail of $1,000 estreated, but this was refused and the case adjourned for eight days.

A remarkable situation exists at Edson in connection with the affair. Stafford, who was acting as temporary chief of police on the instructions of Mayor Lawrence, has been paid off, while town constable Tatham; who was dismissed by the council, has been reinstated by the mayor.

There seems to be a continual war between the council and the mayor, each undoing what's done by the other. An effort is on foot to institute proceedings against the mayor. The town is very much excited over the whole affair and it is freely alleged that some citizens are in league with the bootleggers.

#edmonton#edson alberta#police raid#private detective#bootleggers#bootlegging#selling liquor without a license#house of ill repute#brothel keeper#police violence#political corruption#corrupt officials#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada#fines or jail

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Petite Maison

“The signals we give—yes or no, or maybe—should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.” William Stafford wrote in his poem “A Ritual to Read to Each Other.”

I remembered Stafford while I was making a sketch of La Petite Maison, a restaurant in the tiny village of Cucuron in Provence. I thought the signals La Petite Maison gave on that July afternoon were wonderfully clear and welcoming. The building itself seemed to have a smiling face.

So often I read of contemporary buildings that "challenge us" or make "statements." At La Petite Maison, there are no statements. It’s not the sort of place where people have power lunches or take calls.

While I was making the sketch, an elderly couple strolled up to the menu board at La Petite Maison. They held hands while carefully studying the night's offerings. The signals the menu gave—yes or no, or maybe—were also quite clear.

The couple turned and strolled away from the menu board , down the hill to the village, hand in hand, their white hair bright against the shadows.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well tomorrow going wait for Stafford 101 bus to Haley on 5 March going for birthday treat little king restaurant I hope 10.05am bus arrived in time then after chicken,rice,spice rice, and noodles make sure it gluten-free meal too. I hope noughting going wrong wish could wear Sunflower hidden disabilities landyarc but mum hate it so after meal going going see War Horse at regional theatre on 5 March got be seat by 230pm I wish could get 930am 101 bus but come 915am and can't use bus pass till after 930am in Stafford needly lost it this yesterday needle had paid £6 for bus fare but found it.

0 notes

Photo

In 2020, Ye, previously known as Kanye West, referred to the now infamous monochromatic, Axel Vervoordt–designed mansion where he lived with Kim Kardashian (and where she still resides) as a "futuristic Belgian monastery." Some might’ve just called it minimalist, but what makes Ye’s description of the Hidden Hills mansion feel particularly apt is that the design actually does reference many tenets of modern religious architecture. Its imposing, arched hallways, for one, evoke the landmark Gothic Expressionist-style Grundtvig’s Church in Copenhagen, completed in 1940. Its bare plaster walls, window cutouts, hunks of stone, and sparse, sculptural settings feel like spaces to pray or meditate; they could easily fit in alongside the light-filled atrium of Alvar Aalto’s late-1970s Riola Parish Church, or the concrete-and-glass Church of Light by Tadao Ando, built in 1989. (West and Kardashian have also both worked with Ando on home designs, though West famously left his in ruins.) Whether Ye’s declaration of the home’s look was trendsetting or trendspotting, one thing is clear: religious aesthetics are in the zeitgeist. Though Americans are becoming less religious, moving toward other forms of faith and spirituality (while also growing increasingly socially conservative), churches are being readapted as housing, hotels, and even restaurants and nightclubs. Catholic symbolism and religious aesthetics are en vogue in the traditionally secular worlds of art and fashion. Last year, a pared-down bedding style had a moment as a microtrend dubbed "monastic bed-making." The interior of a Sydney home by Stafford Architecture draws a few similarities to modernist Alvar Aalto’s Riola Parish Church.You don’t have to look far to find other examples of everyday homes that incorporate major aesthetic elements of modern ecclesiastical architecture. A California garage conversion by ADU builder Modern Granny Flat with white walls, curving ceilings, and wooden details, for example, and a Sydney terrace house by Stafford Architecture with a similar palette—plus a slender skylight that creates a holy light-beam effect—are equally reminiscent of the Riola Parish Church interiors. Meanwhile, the geometric cutouts and Tetris-like layout of a concrete cabin in Mexico designed by architect Ludwig Godefroy bring Bristol’s brutalist-style Clifton Cathedral to mind. The tall, concrete walls and geometric cutouts of the brutalist-inspired Alférez House in Mexico remind of the U.K.’s Grade II*-listed Clifton Cathedral, completed in 1973. Architecture organized around channeling the divine is not a new concept; in fact, for millennia, creating sacred space, like Greek temples or Islamic mosques and European cathedrals and synagogues, was one of the field’s main concerns. But the desire for visual simplicity in these spaces—swooping, bare surfaces, raw materials, open interiors, and strategically placed openings to capture sunlight—started to take shape in the early 20th century. The (problematic) Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner’s Goethenaum in Switzerland, for example, was pioneering for its curvilinear, exposed-concrete form when it opened in 1920. The massive domed temple mixed elements of Expressionism and organic architecture; stained-glass windows and skylights flood the pared-down interior with light so as to join its congregation with the divine. The early 20th-century Goethenaum in Switzerland mixes elements of Expressionism and organic architecture. The temple was pioneering for its curvilinear, concrete form.In the wake of World War II, as expedited fixes for partially destroyed buildings required prioritizing inexpensive and available materials like concrete and plaster, more austere modern architecture became generally accepted across Europe and the United States. By the 1950s, modernist architects like Le Corbusier, Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe, and Eero Saarinen were designing ecclesiastical spaces that were stripped of the ornate decoration of Europe’s previously predominant Gothic or Romanesque revival styles. (Photographer Jamie McGregor Smith’s 2024 book documenting postwar church architecture in Europe calls the look "sacred modernity.") The recent resonance of "sacred modernist" sensibilities in our homes is about more than actual spiritualism. In our chaotic Information Age, having a personal environment that facilitates peacefulness—and awe, while you’re at it—is just as sacred as an actual place of worship. "A house is an emotional and psychological landscape," says architect Robin Donaldson, of Donaldson+Partners, who recently completed an expansive, concrete-and-glass residence in California with sweeping hallways and atriums and sound-sensitive sitting nooks that evokes a modernist chapel and a transcendent James Turrell installation in equal measure. (In a full-circle moment: Turrell’s Roden Crater served as the backdrop for one of Kanye West’s Sunday Service gospel performances in the 2019 IMAX documentary, Jesus Is King.) The stairwell of this Melbourne house by LLDS looks like it could be inside the Goethenaum.In her 2017 book, Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives, architecture critic Sarah Williams Goldhagen makes the case for just how profoundly our environments shape our experiences as humans on a neurological level. (Goldhagen is also an expert on Louis Kahn, who himself dabbled in midcentury church design and seemed to have a similar stance on how architecture shapes identity, once saying, "There’s something about a 150-foot ceiling that makes a man a different kind of man," after visiting the Roman Baths of Caracalla.) Sparse, spacious interiors clad in expensive natural materials—whether in a chapel, an in-home meditation room, or a foyer—can foster a soothing atmosphere that’s a psychological luxury. Those same elements also tend to signal wealth (cue: the minimalist look in recent years given the moniker "quiet luxury").Of course, minimalist aesthetics have long cycled in and out of fashion—and, on its own, the use of raw materials and toned-down palettes, or sculptural walls and towering, sky-lit ceilings, isn’t novel or distinct to a specific type of built environment. But in an era rife with "technostress," political turmoil, and worsening climate anxieties, as well as the ongoing disappearance of "third places," it seems like the combination of elements that make our homes feel transcendent is a little bit more holy.Top photo of the Rothko Chapel interior by Smiley N. Pool/Houston Chronicle/Getty Images Source link

0 notes

Photo

In 2020, Ye, previously known as Kanye West, referred to the now infamous monochromatic, Axel Vervoordt–designed mansion where he lived with Kim Kardashian (and where she still resides) as a "futuristic Belgian monastery." Some might’ve just called it minimalist, but what makes Ye’s description of the Hidden Hills mansion feel particularly apt is that the design actually does reference many tenets of modern religious architecture. Its imposing, arched hallways, for one, evoke the landmark Gothic Expressionist-style Grundtvig’s Church in Copenhagen, completed in 1940. Its bare plaster walls, window cutouts, hunks of stone, and sparse, sculptural settings feel like spaces to pray or meditate; they could easily fit in alongside the light-filled atrium of Alvar Aalto’s late-1970s Riola Parish Church, or the concrete-and-glass Church of Light by Tadao Ando, built in 1989. (West and Kardashian have also both worked with Ando on home designs, though West famously left his in ruins.) Whether Ye’s declaration of the home’s look was trendsetting or trendspotting, one thing is clear: religious aesthetics are in the zeitgeist. Though Americans are becoming less religious, moving toward other forms of faith and spirituality (while also growing increasingly socially conservative), churches are being readapted as housing, hotels, and even restaurants and nightclubs. Catholic symbolism and religious aesthetics are en vogue in the traditionally secular worlds of art and fashion. Last year, a pared-down bedding style had a moment as a microtrend dubbed "monastic bed-making." The interior of a Sydney home by Stafford Architecture draws a few similarities to modernist Alvar Aalto’s Riola Parish Church.You don’t have to look far to find other examples of everyday homes that incorporate major aesthetic elements of modern ecclesiastical architecture. A California garage conversion by ADU builder Modern Granny Flat with white walls, curving ceilings, and wooden details, for example, and a Sydney terrace house by Stafford Architecture with a similar palette—plus a slender skylight that creates a holy light-beam effect—are equally reminiscent of the Riola Parish Church interiors. Meanwhile, the geometric cutouts and Tetris-like layout of a concrete cabin in Mexico designed by architect Ludwig Godefroy bring Bristol’s brutalist-style Clifton Cathedral to mind. The tall, concrete walls and geometric cutouts of the brutalist-inspired Alférez House in Mexico remind of the U.K.’s Grade II*-listed Clifton Cathedral, completed in 1973. Architecture organized around channeling the divine is not a new concept; in fact, for millennia, creating sacred space, like Greek temples or Islamic mosques and European cathedrals and synagogues, was one of the field’s main concerns. But the desire for visual simplicity in these spaces—swooping, bare surfaces, raw materials, open interiors, and strategically placed openings to capture sunlight—started to take shape in the early 20th century. The (problematic) Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner’s Goethenaum in Switzerland, for example, was pioneering for its curvilinear, exposed-concrete form when it opened in 1920. The massive domed temple mixed elements of Expressionism and organic architecture; stained-glass windows and skylights flood the pared-down interior with light so as to join its congregation with the divine. The early 20th-century Goethenaum in Switzerland mixes elements of Expressionism and organic architecture. The temple was pioneering for its curvilinear, concrete form.In the wake of World War II, as expedited fixes for partially destroyed buildings required prioritizing inexpensive and available materials like concrete and plaster, more austere modern architecture became generally accepted across Europe and the United States. By the 1950s, modernist architects like Le Corbusier, Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe, and Eero Saarinen were designing ecclesiastical spaces that were stripped of the ornate decoration of Europe’s previously predominant Gothic or Romanesque revival styles. (Photographer Jamie McGregor Smith’s 2024 book documenting postwar church architecture in Europe calls the look "sacred modernity.") The recent resonance of "sacred modernist" sensibilities in our homes is about more than actual spiritualism. In our chaotic Information Age, having a personal environment that facilitates peacefulness—and awe, while you’re at it—is just as sacred as an actual place of worship. "A house is an emotional and psychological landscape," says architect Robin Donaldson, of Donaldson+Partners, who recently completed an expansive, concrete-and-glass residence in California with sweeping hallways and atriums and sound-sensitive sitting nooks that evokes a modernist chapel and a transcendent James Turrell installation in equal measure. (In a full-circle moment: Turrell’s Roden Crater served as the backdrop for one of Kanye West’s Sunday Service gospel performances in the 2019 IMAX documentary, Jesus Is King.) The stairwell of this Melbourne house by LLDS looks like it could be inside the Goethenaum.In her 2017 book, Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives, architecture critic Sarah Williams Goldhagen makes the case for just how profoundly our environments shape our experiences as humans on a neurological level. (Goldhagen is also an expert on Louis Kahn, who himself dabbled in midcentury church design and seemed to have a similar stance on how architecture shapes identity, once saying, "There’s something about a 150-foot ceiling that makes a man a different kind of man," after visiting the Roman Baths of Caracalla.) Sparse, spacious interiors clad in expensive natural materials—whether in a chapel, an in-home meditation room, or a foyer—can foster a soothing atmosphere that’s a psychological luxury. Those same elements also tend to signal wealth (cue: the minimalist look in recent years given the moniker "quiet luxury").Of course, minimalist aesthetics have long cycled in and out of fashion—and, on its own, the use of raw materials and toned-down palettes, or sculptural walls and towering, sky-lit ceilings, isn’t novel or distinct to a specific type of built environment. But in an era rife with "technostress," political turmoil, and worsening climate anxieties, as well as the ongoing disappearance of "third places," it seems like the combination of elements that make our homes feel transcendent is a little bit more holy.Top photo of the Rothko Chapel interior by Smiley N. Pool/Houston Chronicle/Getty Images Source link

0 notes

Photo

In 2020, Ye, previously known as Kanye West, referred to the now infamous monochromatic, Axel Vervoordt–designed mansion where he lived with Kim Kardashian (and where she still resides) as a "futuristic Belgian monastery." Some might’ve just called it minimalist, but what makes Ye’s description of the Hidden Hills mansion feel particularly apt is that the design actually does reference many tenets of modern religious architecture. Its imposing, arched hallways, for one, evoke the landmark Gothic Expressionist-style Grundtvig’s Church in Copenhagen, completed in 1940. Its bare plaster walls, window cutouts, hunks of stone, and sparse, sculptural settings feel like spaces to pray or meditate; they could easily fit in alongside the light-filled atrium of Alvar Aalto’s late-1970s Riola Parish Church, or the concrete-and-glass Church of Light by Tadao Ando, built in 1989. (West and Kardashian have also both worked with Ando on home designs, though West famously left his in ruins.) Whether Ye’s declaration of the home’s look was trendsetting or trendspotting, one thing is clear: religious aesthetics are in the zeitgeist. Though Americans are becoming less religious, moving toward other forms of faith and spirituality (while also growing increasingly socially conservative), churches are being readapted as housing, hotels, and even restaurants and nightclubs. Catholic symbolism and religious aesthetics are en vogue in the traditionally secular worlds of art and fashion. Last year, a pared-down bedding style had a moment as a microtrend dubbed "monastic bed-making." The interior of a Sydney home by Stafford Architecture draws a few similarities to modernist Alvar Aalto’s Riola Parish Church.You don’t have to look far to find other examples of everyday homes that incorporate major aesthetic elements of modern ecclesiastical architecture. A California garage conversion��by ADU builder Modern Granny Flat with white walls, curving ceilings, and wooden details, for example, and a Sydney terrace house by Stafford Architecture with a similar palette—plus a slender skylight that creates a holy light-beam effect—are equally reminiscent of the Riola Parish Church interiors. Meanwhile, the geometric cutouts and Tetris-like layout of a concrete cabin in Mexico designed by architect Ludwig Godefroy bring Bristol’s brutalist-style Clifton Cathedral to mind. The tall, concrete walls and geometric cutouts of the brutalist-inspired Alférez House in Mexico remind of the U.K.’s Grade II*-listed Clifton Cathedral, completed in 1973. Architecture organized around channeling the divine is not a new concept; in fact, for millennia, creating sacred space, like Greek temples or Islamic mosques and European cathedrals and synagogues, was one of the field’s main concerns. But the desire for visual simplicity in these spaces—swooping, bare surfaces, raw materials, open interiors, and strategically placed openings to capture sunlight—started to take shape in the early 20th century. The (problematic) Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner’s Goethenaum in Switzerland, for example, was pioneering for its curvilinear, exposed-concrete form when it opened in 1920. The massive domed temple mixed elements of Expressionism and organic architecture; stained-glass windows and skylights flood the pared-down interior with light so as to join its congregation with the divine. The early 20th-century Goethenaum in Switzerland mixes elements of Expressionism and organic architecture. The temple was pioneering for its curvilinear, concrete form.In the wake of World War II, as expedited fixes for partially destroyed buildings required prioritizing inexpensive and available materials like concrete and plaster, more austere modern architecture became generally accepted across Europe and the United States. By the 1950s, modernist architects like Le Corbusier, Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe, and Eero Saarinen were designing ecclesiastical spaces that were stripped of the ornate decoration of Europe’s previously predominant Gothic or Romanesque revival styles. (Photographer Jamie McGregor Smith’s 2024 book documenting postwar church architecture in Europe calls the look "sacred modernity.") The recent resonance of "sacred modernist" sensibilities in our homes is about more than actual spiritualism. In our chaotic Information Age, having a personal environment that facilitates peacefulness—and awe, while you’re at it—is just as sacred as an actual place of worship. "A house is an emotional and psychological landscape," says architect Robin Donaldson, of Donaldson+Partners, who recently completed an expansive, concrete-and-glass residence in California with sweeping hallways and atriums and sound-sensitive sitting nooks that evokes a modernist chapel and a transcendent James Turrell installation in equal measure. (In a full-circle moment: Turrell’s Roden Crater served as the backdrop for one of Kanye West’s Sunday Service gospel performances in the 2019 IMAX documentary, Jesus Is King.) The stairwell of this Melbourne house by LLDS looks like it could be inside the Goethenaum.In her 2017 book, Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives, architecture critic Sarah Williams Goldhagen makes the case for just how profoundly our environments shape our experiences as humans on a neurological level. (Goldhagen is also an expert on Louis Kahn, who himself dabbled in midcentury church design and seemed to have a similar stance on how architecture shapes identity, once saying, "There’s something about a 150-foot ceiling that makes a man a different kind of man," after visiting the Roman Baths of Caracalla.) Sparse, spacious interiors clad in expensive natural materials—whether in a chapel, an in-home meditation room, or a foyer—can foster a soothing atmosphere that’s a psychological luxury. Those same elements also tend to signal wealth (cue: the minimalist look in recent years given the moniker "quiet luxury").Of course, minimalist aesthetics have long cycled in and out of fashion—and, on its own, the use of raw materials and toned-down palettes, or sculptural walls and towering, sky-lit ceilings, isn’t novel or distinct to a specific type of built environment. But in an era rife with "technostress," political turmoil, and worsening climate anxieties, as well as the ongoing disappearance of "third places," it seems like the combination of elements that make our homes feel transcendent is a little bit more holy.Top photo of the Rothko Chapel interior by Smiley N. Pool/Houston Chronicle/Getty Images Source link

0 notes

Photo

In 2020, Ye, previously known as Kanye West, referred to the now infamous monochromatic, Axel Vervoordt–designed mansion where he lived with Kim Kardashian (and where she still resides) as a "futuristic Belgian monastery." Some might’ve just called it minimalist, but what makes Ye’s description of the Hidden Hills mansion feel particularly apt is that the design actually does reference many tenets of modern religious architecture. Its imposing, arched hallways, for one, evoke the landmark Gothic Expressionist-style Grundtvig’s Church in Copenhagen, completed in 1940. Its bare plaster walls, window cutouts, hunks of stone, and sparse, sculptural settings feel like spaces to pray or meditate; they could easily fit in alongside the light-filled atrium of Alvar Aalto’s late-1970s Riola Parish Church, or the concrete-and-glass Church of Light by Tadao Ando, built in 1989. (West and Kardashian have also both worked with Ando on home designs, though West famously left his in ruins.) Whether Ye’s declaration of the home’s look was trendsetting or trendspotting, one thing is clear: religious aesthetics are in the zeitgeist. Though Americans are becoming less religious, moving toward other forms of faith and spirituality (while also growing increasingly socially conservative), churches are being readapted as housing, hotels, and even restaurants and nightclubs. Catholic symbolism and religious aesthetics are en vogue in the traditionally secular worlds of art and fashion. Last year, a pared-down bedding style had a moment as a microtrend dubbed "monastic bed-making." The interior of a Sydney home by Stafford Architecture draws a few similarities to modernist Alvar Aalto’s Riola Parish Church.You don’t have to look far to find other examples of everyday homes that incorporate major aesthetic elements of modern ecclesiastical architecture. A California garage conversion by ADU builder Modern Granny Flat with white walls, curving ceilings, and wooden details, for example, and a Sydney terrace house by Stafford Architecture with a similar palette—plus a slender skylight that creates a holy light-beam effect—are equally reminiscent of the Riola Parish Church interiors. Meanwhile, the geometric cutouts and Tetris-like layout of a concrete cabin in Mexico designed by architect Ludwig Godefroy bring Bristol’s brutalist-style Clifton Cathedral to mind. The tall, concrete walls and geometric cutouts of the brutalist-inspired Alférez House in Mexico remind of the U.K.’s Grade II*-listed Clifton Cathedral, completed in 1973. Architecture organized around channeling the divine is not a new concept; in fact, for millennia, creating sacred space, like Greek temples or Islamic mosques and European cathedrals and synagogues, was one of the field’s main concerns. But the desire for visual simplicity in these spaces—swooping, bare surfaces, raw materials, open interiors, and strategically placed openings to capture sunlight—started to take shape in the early 20th century. The (problematic) Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner’s Goethenaum in Switzerland, for example, was pioneering for its curvilinear, exposed-concrete form when it opened in 1920. The massive domed temple mixed elements of Expressionism and organic architecture; stained-glass windows and skylights flood the pared-down interior with light so as to join its congregation with the divine. The early 20th-century Goethenaum in Switzerland mixes elements of Expressionism and organic architecture. The temple was pioneering for its curvilinear, concrete form.In the wake of World War II, as expedited fixes for partially destroyed buildings required prioritizing inexpensive and available materials like concrete and plaster, more austere modern architecture became generally accepted across Europe and the United States. By the 1950s, modernist architects like Le Corbusier, Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe, and Eero Saarinen were designing ecclesiastical spaces that were stripped of the ornate decoration of Europe’s previously predominant Gothic or Romanesque revival styles. (Photographer Jamie McGregor Smith’s 2024 book documenting postwar church architecture in Europe calls the look "sacred modernity.") The recent resonance of "sacred modernist" sensibilities in our homes is about more than actual spiritualism. In our chaotic Information Age, having a personal environment that facilitates peacefulness—and awe, while you’re at it—is just as sacred as an actual place of worship. "A house is an emotional and psychological landscape," says architect Robin Donaldson, of Donaldson+Partners, who recently completed an expansive, concrete-and-glass residence in California with sweeping hallways and atriums and sound-sensitive sitting nooks that evokes a modernist chapel and a transcendent James Turrell installation in equal measure. (In a full-circle moment: Turrell’s Roden Crater served as the backdrop for one of Kanye West’s Sunday Service gospel performances in the 2019 IMAX documentary, Jesus Is King.) The stairwell of this Melbourne house by LLDS looks like it could be inside the Goethenaum.In her 2017 book, Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives, architecture critic Sarah Williams Goldhagen makes the case for just how profoundly our environments shape our experiences as humans on a neurological level. (Goldhagen is also an expert on Louis Kahn, who himself dabbled in midcentury church design and seemed to have a similar stance on how architecture shapes identity, once saying, "There’s something about a 150-foot ceiling that makes a man a different kind of man," after visiting the Roman Baths of Caracalla.) Sparse, spacious interiors clad in expensive natural materials—whether in a chapel, an in-home meditation room, or a foyer—can foster a soothing atmosphere that’s a psychological luxury. Those same elements also tend to signal wealth (cue: the minimalist look in recent years given the moniker "quiet luxury").Of course, minimalist aesthetics have long cycled in and out of fashion—and, on its own, the use of raw materials and toned-down palettes, or sculptural walls and towering, sky-lit ceilings, isn’t novel or distinct to a specific type of built environment. But in an era rife with "technostress," political turmoil, and worsening climate anxieties, as well as the ongoing disappearance of "third places," it seems like the combination of elements that make our homes feel transcendent is a little bit more holy.Top photo of the Rothko Chapel interior by Smiley N. Pool/Houston Chronicle/Getty Images Source link

0 notes

Photo

In 2020, Ye, previously known as Kanye West, referred to the now infamous monochromatic, Axel Vervoordt–designed mansion where he lived with Kim Kardashian (and where she still resides) as a "futuristic Belgian monastery." Some might’ve just called it minimalist, but what makes Ye’s description of the Hidden Hills mansion feel particularly apt is that the design actually does reference many tenets of modern religious architecture. Its imposing, arched hallways, for one, evoke the landmark Gothic Expressionist-style Grundtvig’s Church in Copenhagen, completed in 1940. Its bare plaster walls, window cutouts, hunks of stone, and sparse, sculptural settings feel like spaces to pray or meditate; they could easily fit in alongside the light-filled atrium of Alvar Aalto’s late-1970s Riola Parish Church, or the concrete-and-glass Church of Light by Tadao Ando, built in 1989. (West and Kardashian have also both worked with Ando on home designs, though West famously left his in ruins.) Whether Ye’s declaration of the home’s look was trendsetting or trendspotting, one thing is clear: religious aesthetics are in the zeitgeist. Though Americans are becoming less religious, moving toward other forms of faith and spirituality (while also growing increasingly socially conservative), churches are being readapted as housing, hotels, and even restaurants and nightclubs. Catholic symbolism and religious aesthetics are en vogue in the traditionally secular worlds of art and fashion. Last year, a pared-down bedding style had a moment as a microtrend dubbed "monastic bed-making." The interior of a Sydney home by Stafford Architecture draws a few similarities to modernist Alvar Aalto’s Riola Parish Church.You don’t have to look far to find other examples of everyday homes that incorporate major aesthetic elements of modern ecclesiastical architecture. A California garage conversion by ADU builder Modern Granny Flat with white walls, curving ceilings, and wooden details, for example, and a Sydney terrace house by Stafford Architecture with a similar palette—plus a slender skylight that creates a holy light-beam effect—are equally reminiscent of the Riola Parish Church interiors. Meanwhile, the geometric cutouts and Tetris-like layout of a concrete cabin in Mexico designed by architect Ludwig Godefroy bring Bristol’s brutalist-style Clifton Cathedral to mind. The tall, concrete walls and geometric cutouts of the brutalist-inspired Alférez House in Mexico remind of the U.K.’s Grade II*-listed Clifton Cathedral, completed in 1973. Architecture organized around channeling the divine is not a new concept; in fact, for millennia, creating sacred space, like Greek temples or Islamic mosques and European cathedrals and synagogues, was one of the field’s main concerns. But the desire for visual simplicity in these spaces—swooping, bare surfaces, raw materials, open interiors, and strategically placed openings to capture sunlight—started to take shape in the early 20th century. The (problematic) Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner’s Goethenaum in Switzerland, for example, was pioneering for its curvilinear, exposed-concrete form when it opened in 1920. The massive domed temple mixed elements of Expressionism and organic architecture; stained-glass windows and skylights flood the pared-down interior with light so as to join its congregation with the divine. The early 20th-century Goethenaum in Switzerland mixes elements of Expressionism and organic architecture. The temple was pioneering for its curvilinear, concrete form.In the wake of World War II, as expedited fixes for partially destroyed buildings required prioritizing inexpensive and available materials like concrete and plaster, more austere modern architecture became generally accepted across Europe and the United States. By the 1950s, modernist architects like Le Corbusier, Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe, and Eero Saarinen were designing ecclesiastical spaces that were stripped of the ornate decoration of Europe’s previously predominant Gothic or Romanesque revival styles. (Photographer Jamie McGregor Smith’s 2024 book documenting postwar church architecture in Europe calls the look "sacred modernity.") The recent resonance of "sacred modernist" sensibilities in our homes is about more than actual spiritualism. In our chaotic Information Age, having a personal environment that facilitates peacefulness—and awe, while you’re at it—is just as sacred as an actual place of worship. "A house is an emotional and psychological landscape," says architect Robin Donaldson, of Donaldson+Partners, who recently completed an expansive, concrete-and-glass residence in California with sweeping hallways and atriums and sound-sensitive sitting nooks that evokes a modernist chapel and a transcendent James Turrell installation in equal measure. (In a full-circle moment: Turrell’s Roden Crater served as the backdrop for one of Kanye West’s Sunday Service gospel performances in the 2019 IMAX documentary, Jesus Is King.) The stairwell of this Melbourne house by LLDS looks like it could be inside the Goethenaum.In her 2017 book, Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives, architecture critic Sarah Williams Goldhagen makes the case for just how profoundly our environments shape our experiences as humans on a neurological level. (Goldhagen is also an expert on Louis Kahn, who himself dabbled in midcentury church design and seemed to have a similar stance on how architecture shapes identity, once saying, "There’s something about a 150-foot ceiling that makes a man a different kind of man," after visiting the Roman Baths of Caracalla.) Sparse, spacious interiors clad in expensive natural materials—whether in a chapel, an in-home meditation room, or a foyer—can foster a soothing atmosphere that’s a psychological luxury. Those same elements also tend to signal wealth (cue: the minimalist look in recent years given the moniker "quiet luxury").Of course, minimalist aesthetics have long cycled in and out of fashion—and, on its own, the use of raw materials and toned-down palettes, or sculptural walls and towering, sky-lit ceilings, isn’t novel or distinct to a specific type of built environment. But in an era rife with "technostress," political turmoil, and worsening climate anxieties, as well as the ongoing disappearance of "third places," it seems like the combination of elements that make our homes feel transcendent is a little bit more holy.Top photo of the Rothko Chapel interior by Smiley N. Pool/Houston Chronicle/Getty Images Source link

0 notes

Photo

In 2020, Ye, previously known as Kanye West, referred to the now infamous monochromatic, Axel Vervoordt–designed mansion where he lived with Kim Kardashian (and where she still resides) as a "futuristic Belgian monastery." Some might’ve just called it minimalist, but what makes Ye’s description of the Hidden Hills mansion feel particularly apt is that the design actually does reference many tenets of modern religious architecture. Its imposing, arched hallways, for one, evoke the landmark Gothic Expressionist-style Grundtvig’s Church in Copenhagen, completed in 1940. Its bare plaster walls, window cutouts, hunks of stone, and sparse, sculptural settings feel like spaces to pray or meditate; they could easily fit in alongside the light-filled atrium of Alvar Aalto’s late-1970s Riola Parish Church, or the concrete-and-glass Church of Light by Tadao Ando, built in 1989. (West and Kardashian have also both worked with Ando on home designs, though West famously left his in ruins.) Whether Ye’s declaration of the home’s look was trendsetting or trendspotting, one thing is clear: religious aesthetics are in the zeitgeist. Though Americans are becoming less religious, moving toward other forms of faith and spirituality (while also growing increasingly socially conservative), churches are being readapted as housing, hotels, and even restaurants and nightclubs. Catholic symbolism and religious aesthetics are en vogue in the traditionally secular worlds of art and fashion. Last year, a pared-down bedding style had a moment as a microtrend dubbed "monastic bed-making." The interior of a Sydney home by Stafford Architecture draws a few similarities to modernist Alvar Aalto’s Riola Parish Church.You don’t have to look far to find other examples of everyday homes that incorporate major aesthetic elements of modern ecclesiastical architecture. A California garage conversion by ADU builder Modern Granny Flat with white walls, curving ceilings, and wooden details, for example, and a Sydney terrace house by Stafford Architecture with a similar palette—plus a slender skylight that creates a holy light-beam effect—are equally reminiscent of the Riola Parish Church interiors. Meanwhile, the geometric cutouts and Tetris-like layout of a concrete cabin in Mexico designed by architect Ludwig Godefroy bring Bristol’s brutalist-style Clifton Cathedral to mind. The tall, concrete walls and geometric cutouts of the brutalist-inspired Alférez House in Mexico remind of the U.K.’s Grade II*-listed Clifton Cathedral, completed in 1973. Architecture organized around channeling the divine is not a new concept; in fact, for millennia, creating sacred space, like Greek temples or Islamic mosques and European cathedrals and synagogues, was one of the field’s main concerns. But the desire for visual simplicity in these spaces—swooping, bare surfaces, raw materials, open interiors, and strategically placed openings to capture sunlight—started to take shape in the early 20th century. The (problematic) Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner’s Goethenaum in Switzerland, for example, was pioneering for its curvilinear, exposed-concrete form when it opened in 1920. The massive domed temple mixed elements of Expressionism and organic architecture; stained-glass windows and skylights flood the pared-down interior with light so as to join its congregation with the divine. The early 20th-century Goethenaum in Switzerland mixes elements of Expressionism and organic architecture. The temple was pioneering for its curvilinear, concrete form.In the wake of World War II, as expedited fixes for partially destroyed buildings required prioritizing inexpensive and available materials like concrete and plaster, more austere modern architecture became generally accepted across Europe and the United States. By the 1950s, modernist architects like Le Corbusier, Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe, and Eero Saarinen were designing ecclesiastical spaces that were stripped of the ornate decoration of Europe’s previously predominant Gothic or Romanesque revival styles. (Photographer Jamie McGregor Smith’s 2024 book documenting postwar church architecture in Europe calls the look "sacred modernity.") The recent resonance of "sacred modernist" sensibilities in our homes is about more than actual spiritualism. In our chaotic Information Age, having a personal environment that facilitates peacefulness—and awe, while you’re at it—is just as sacred as an actual place of worship. "A house is an emotional and psychological landscape," says architect Robin Donaldson, of Donaldson+Partners, who recently completed an expansive, concrete-and-glass residence in California with sweeping hallways and atriums and sound-sensitive sitting nooks that evokes a modernist chapel and a transcendent James Turrell installation in equal measure. (In a full-circle moment: Turrell’s Roden Crater served as the backdrop for one of Kanye West’s Sunday Service gospel performances in the 2019 IMAX documentary, Jesus Is King.) The stairwell of this Melbourne house by LLDS looks like it could be inside the Goethenaum.In her 2017 book, Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives, architecture critic Sarah Williams Goldhagen makes the case for just how profoundly our environments shape our experiences as humans on a neurological level. (Goldhagen is also an expert on Louis Kahn, who himself dabbled in midcentury church design and seemed to have a similar stance on how architecture shapes identity, once saying, "There’s something about a 150-foot ceiling that makes a man a different kind of man," after visiting the Roman Baths of Caracalla.) Sparse, spacious interiors clad in expensive natural materials—whether in a chapel, an in-home meditation room, or a foyer—can foster a soothing atmosphere that’s a psychological luxury. Those same elements also tend to signal wealth (cue: the minimalist look in recent years given the moniker "quiet luxury").Of course, minimalist aesthetics have long cycled in and out of fashion—and, on its own, the use of raw materials and toned-down palettes, or sculptural walls and towering, sky-lit ceilings, isn’t novel or distinct to a specific type of built environment. But in an era rife with "technostress," political turmoil, and worsening climate anxieties, as well as the ongoing disappearance of "third places," it seems like the combination of elements that make our homes feel transcendent is a little bit more holy.Top photo of the Rothko Chapel interior by Smiley N. Pool/Houston Chronicle/Getty Images Source link

0 notes

Photo

In 2020, Ye, previously known as Kanye West, referred to the now infamous monochromatic, Axel Vervoordt–designed mansion where he lived with Kim Kardashian (and where she still resides) as a "futuristic Belgian monastery." Some might’ve just called it minimalist, but what makes Ye’s description of the Hidden Hills mansion feel particularly apt is that the design actually does reference many tenets of modern religious architecture. Its imposing, arched hallways, for one, evoke the landmark Gothic Expressionist-style Grundtvig’s Church in Copenhagen, completed in 1940. Its bare plaster walls, window cutouts, hunks of stone, and sparse, sculptural settings feel like spaces to pray or meditate; they could easily fit in alongside the light-filled atrium of Alvar Aalto’s late-1970s Riola Parish Church, or the concrete-and-glass Church of Light by Tadao Ando, built in 1989. (West and Kardashian have also both worked with Ando on home designs, though West famously left his in ruins.) Whether Ye’s declaration of the home’s look was trendsetting or trendspotting, one thing is clear: religious aesthetics are in the zeitgeist. Though Americans are becoming less religious, moving toward other forms of faith and spirituality (while also growing increasingly socially conservative), churches are being readapted as housing, hotels, and even restaurants and nightclubs. Catholic symbolism and religious aesthetics are en vogue in the traditionally secular worlds of art and fashion. Last year, a pared-down bedding style had a moment as a microtrend dubbed "monastic bed-making." The interior of a Sydney home by Stafford Architecture draws a few similarities to modernist Alvar Aalto’s Riola Parish Church.You don’t have to look far to find other examples of everyday homes that incorporate major aesthetic elements of modern ecclesiastical architecture. A California garage conversion by ADU builder Modern Granny Flat with white walls, curving ceilings, and wooden details, for example, and a Sydney terrace house by Stafford Architecture with a similar palette—plus a slender skylight that creates a holy light-beam effect—are equally reminiscent of the Riola Parish Church interiors. Meanwhile, the geometric cutouts and Tetris-like layout of a concrete cabin in Mexico designed by architect Ludwig Godefroy bring Bristol’s brutalist-style Clifton Cathedral to mind. The tall, concrete walls and geometric cutouts of the brutalist-inspired Alférez House in Mexico remind of the U.K.’s Grade II*-listed Clifton Cathedral, completed in 1973. Architecture organized around channeling the divine is not a new concept; in fact, for millennia, creating sacred space, like Greek temples or Islamic mosques and European cathedrals and synagogues, was one of the field’s main concerns. But the desire for visual simplicity in these spaces—swooping, bare surfaces, raw materials, open interiors, and strategically placed openings to capture sunlight—started to take shape in the early 20th century. The (problematic) Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner’s Goethenaum in Switzerland, for example, was pioneering for its curvilinear, exposed-concrete form when it opened in 1920. The massive domed temple mixed elements of Expressionism and organic architecture; stained-glass windows and skylights flood the pared-down interior with light so as to join its congregation with the divine. The early 20th-century Goethenaum in Switzerland mixes elements of Expressionism and organic architecture. The temple was pioneering for its curvilinear, concrete form.In the wake of World War II, as expedited fixes for partially destroyed buildings required prioritizing inexpensive and available materials like concrete and plaster, more austere modern architecture became generally accepted across Europe and the United States. By the 1950s, modernist architects like Le Corbusier, Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe, and Eero Saarinen were designing ecclesiastical spaces that were stripped of the ornate decoration of Europe’s previously predominant Gothic or Romanesque revival styles. (Photographer Jamie McGregor Smith’s 2024 book documenting postwar church architecture in Europe calls the look "sacred modernity.") The recent resonance of "sacred modernist" sensibilities in our homes is about more than actual spiritualism. In our chaotic Information Age, having a personal environment that facilitates peacefulness—and awe, while you’re at it—is just as sacred as an actual place of worship. "A house is an emotional and psychological landscape," says architect Robin Donaldson, of Donaldson+Partners, who recently completed an expansive, concrete-and-glass residence in California with sweeping hallways and atriums and sound-sensitive sitting nooks that evokes a modernist chapel and a transcendent James Turrell installation in equal measure. (In a full-circle moment: Turrell’s Roden Crater served as the backdrop for one of Kanye West’s Sunday Service gospel performances in the 2019 IMAX documentary, Jesus Is King.) The stairwell of this Melbourne house by LLDS looks like it could be inside the Goethenaum.In her 2017 book, Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives, architecture critic Sarah Williams Goldhagen makes the case for just how profoundly our environments shape our experiences as humans on a neurological level. (Goldhagen is also an expert on Louis Kahn, who himself dabbled in midcentury church design and seemed to have a similar stance on how architecture shapes identity, once saying, "There’s something about a 150-foot ceiling that makes a man a different kind of man," after visiting the Roman Baths of Caracalla.) Sparse, spacious interiors clad in expensive natural materials—whether in a chapel, an in-home meditation room, or a foyer—can foster a soothing atmosphere that’s a psychological luxury. Those same elements also tend to signal wealth (cue: the minimalist look in recent years given the moniker "quiet luxury").Of course, minimalist aesthetics have long cycled in and out of fashion—and, on its own, the use of raw materials and toned-down palettes, or sculptural walls and towering, sky-lit ceilings, isn’t novel or distinct to a specific type of built environment. But in an era rife with "technostress," political turmoil, and worsening climate anxieties, as well as the ongoing disappearance of "third places," it seems like the combination of elements that make our homes feel transcendent is a little bit more holy.Top photo of the Rothko Chapel interior by Smiley N. Pool/Houston Chronicle/Getty Images Source link

0 notes

Photo

In 2020, Ye, previously known as Kanye West, referred to the now infamous monochromatic, Axel Vervoordt–designed mansion where he lived with Kim Kardashian (and where she still resides) as a "futuristic Belgian monastery." Some might’ve just called it minimalist, but what makes Ye’s description of the Hidden Hills mansion feel particularly apt is that the design actually does reference many tenets of modern religious architecture. Its imposing, arched hallways, for one, evoke the landmark Gothic Expressionist-style Grundtvig’s Church in Copenhagen, completed in 1940. Its bare plaster walls, window cutouts, hunks of stone, and sparse, sculptural settings feel like spaces to pray or meditate; they could easily fit in alongside the light-filled atrium of Alvar Aalto’s late-1970s Riola Parish Church, or the concrete-and-glass Church of Light by Tadao Ando, built in 1989. (West and Kardashian have also both worked with Ando on home designs, though West famously left his in ruins.) Whether Ye’s declaration of the home’s look was trendsetting or trendspotting, one thing is clear: religious aesthetics are in the zeitgeist. Though Americans are becoming less religious, moving toward other forms of faith and spirituality (while also growing increasingly socially conservative), churches are being readapted as housing, hotels, and even restaurants and nightclubs. Catholic symbolism and religious aesthetics are en vogue in the traditionally secular worlds of art and fashion. Last year, a pared-down bedding style had a moment as a microtrend dubbed "monastic bed-making." The interior of a Sydney home by Stafford Architecture draws a few similarities to modernist Alvar Aalto’s Riola Parish Church.You don’t have to look far to find other examples of everyday homes that incorporate major aesthetic elements of modern ecclesiastical architecture. A California garage conversion by ADU builder Modern Granny Flat with white walls, curving ceilings, and wooden details, for example, and a Sydney terrace house by Stafford Architecture with a similar palette—plus a slender skylight that creates a holy light-beam effect—are equally reminiscent of the Riola Parish Church interiors. Meanwhile, the geometric cutouts and Tetris-like layout of a concrete cabin in Mexico designed by architect Ludwig Godefroy bring Bristol’s brutalist-style Clifton Cathedral to mind. The tall, concrete walls and geometric cutouts of the brutalist-inspired Alférez House in Mexico remind of the U.K.’s Grade II*-listed Clifton Cathedral, completed in 1973. Architecture organized around channeling the divine is not a new concept; in fact, for millennia, creating sacred space, like Greek temples or Islamic mosques and European cathedrals and synagogues, was one of the field’s main concerns. But the desire for visual simplicity in these spaces—swooping, bare surfaces, raw materials, open interiors, and strategically placed openings to capture sunlight—started to take shape in the early 20th century. The (problematic) Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner’s Goethenaum in Switzerland, for example, was pioneering for its curvilinear, exposed-concrete form when it opened in 1920. The massive domed temple mixed elements of Expressionism and organic architecture; stained-glass windows and skylights flood the pared-down interior with light so as to join its congregation with the divine. The early 20th-century Goethenaum in Switzerland mixes elements of Expressionism and organic architecture. The temple was pioneering for its curvilinear, concrete form.In the wake of World War II, as expedited fixes for partially destroyed buildings required prioritizing inexpensive and available materials like concrete and plaster, more austere modern architecture became generally accepted across Europe and the United States. By the 1950s, modernist architects like Le Corbusier, Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe, and Eero Saarinen were designing ecclesiastical spaces that were stripped of the ornate decoration of Europe’s previously predominant Gothic or Romanesque revival styles. (Photographer Jamie McGregor Smith’s 2024 book documenting postwar church architecture in Europe calls the look "sacred modernity.") The recent resonance of "sacred modernist" sensibilities in our homes is about more than actual spiritualism. In our chaotic Information Age, having a personal environment that facilitates peacefulness—and awe, while you’re at it—is just as sacred as an actual place of worship. "A house is an emotional and psychological landscape," says architect Robin Donaldson, of Donaldson+Partners, who recently completed an expansive, concrete-and-glass residence in California with sweeping hallways and atriums and sound-sensitive sitting nooks that evokes a modernist chapel and a transcendent James Turrell installation in equal measure. (In a full-circle moment: Turrell’s Roden Crater served as the backdrop for one of Kanye West’s Sunday Service gospel performances in the 2019 IMAX documentary, Jesus Is King.) The stairwell of this Melbourne house by LLDS looks like it could be inside the Goethenaum.In her 2017 book, Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives, architecture critic Sarah Williams Goldhagen makes the case for just how profoundly our environments shape our experiences as humans on a neurological level. (Goldhagen is also an expert on Louis Kahn, who himself dabbled in midcentury church design and seemed to have a similar stance on how architecture shapes identity, once saying, "There’s something about a 150-foot ceiling that makes a man a different kind of man," after visiting the Roman Baths of Caracalla.) Sparse, spacious interiors clad in expensive natural materials—whether in a chapel, an in-home meditation room, or a foyer—can foster a soothing atmosphere that’s a psychological luxury. Those same elements also tend to signal wealth (cue: the minimalist look in recent years given the moniker "quiet luxury").Of course, minimalist aesthetics have long cycled in and out of fashion—and, on its own, the use of raw materials and toned-down palettes, or sculptural walls and towering, sky-lit ceilings, isn’t novel or distinct to a specific type of built environment. But in an era rife with "technostress," political turmoil, and worsening climate anxieties, as well as the ongoing disappearance of "third places," it seems like the combination of elements that make our homes feel transcendent is a little bit more holy.Top photo of the Rothko Chapel interior by Smiley N. Pool/Houston Chronicle/Getty Images Source link

0 notes

Photo

In 2020, Ye, previously known as Kanye West, referred to the now infamous monochromatic, Axel Vervoordt–designed mansion where he lived with Kim Kardashian (and where she still resides) as a "futuristic Belgian monastery." Some might’ve just called it minimalist, but what makes Ye’s description of the Hidden Hills mansion feel particularly apt is that the design actually does reference many tenets of modern religious architecture. Its imposing, arched hallways, for one, evoke the landmark Gothic Expressionist-style Grundtvig’s Church in Copenhagen, completed in 1940. Its bare plaster walls, window cutouts, hunks of stone, and sparse, sculptural settings feel like spaces to pray or meditate; they could easily fit in alongside the light-filled atrium of Alvar Aalto’s late-1970s Riola Parish Church, or the concrete-and-glass Church of Light by Tadao Ando, built in 1989. (West and Kardashian have also both worked with Ando on home designs, though West famously left his in ruins.) Whether Ye’s declaration of the home’s look was trendsetting or trendspotting, one thing is clear: religious aesthetics are in the zeitgeist. Though Americans are becoming less religious, moving toward other forms of faith and spirituality (while also growing increasingly socially conservative), churches are being readapted as housing, hotels, and even restaurants and nightclubs. Catholic symbolism and religious aesthetics are en vogue in the traditionally secular worlds of art and fashion. Last year, a pared-down bedding style had a moment as a microtrend dubbed "monastic bed-making." The interior of a Sydney home by Stafford Architecture draws a few similarities to modernist Alvar Aalto’s Riola Parish Church.You don’t have to look far to find other examples of everyday homes that incorporate major aesthetic elements of modern ecclesiastical architecture. A California garage conversion by ADU builder Modern Granny Flat with white walls, curving ceilings, and wooden details, for example, and a Sydney terrace house by Stafford Architecture with a similar palette—plus a slender skylight that creates a holy light-beam effect—are equally reminiscent of the Riola Parish Church interiors. Meanwhile, the geometric cutouts and Tetris-like layout of a concrete cabin in Mexico designed by architect Ludwig Godefroy bring Bristol’s brutalist-style Clifton Cathedral to mind. The tall, concrete walls and geometric cutouts of the brutalist-inspired Alférez House in Mexico remind of the U.K.’s Grade II*-listed Clifton Cathedral, completed in 1973. Architecture organized around channeling the divine is not a new concept; in fact, for millennia, creating sacred space, like Greek temples or Islamic mosques and European cathedrals and synagogues, was one of the field’s main concerns. But the desire for visual simplicity in these spaces—swooping, bare surfaces, raw materials, open interiors, and strategically placed openings to capture sunlight—started to take shape in the early 20th century. The (problematic) Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner’s Goethenaum in Switzerland, for example, was pioneering for its curvilinear, exposed-concrete form when it opened in 1920. The massive domed temple mixed elements of Expressionism and organic architecture; stained-glass windows and skylights flood the pared-down interior with light so as to join its congregation with the divine. The early 20th-century Goethenaum in Switzerland mixes elements of Expressionism and organic architecture. The temple was pioneering for its curvilinear, concrete form.In the wake of World War II, as expedited fixes for partially destroyed buildings required prioritizing inexpensive and available materials like concrete and plaster, more austere modern architecture became generally accepted across Europe and the United States. By the 1950s, modernist architects like Le Corbusier, Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe, and Eero Saarinen were designing ecclesiastical spaces that were stripped of the ornate decoration of Europe’s previously predominant Gothic or Romanesque revival styles. (Photographer Jamie McGregor Smith’s 2024 book documenting postwar church architecture in Europe calls the look "sacred modernity.") The recent resonance of "sacred modernist" sensibilities in our homes is about more than actual spiritualism. In our chaotic Information Age, having a personal environment that facilitates peacefulness—and awe, while you’re at it—is just as sacred as an actual place of worship. "A house is an emotional and psychological landscape," says architect Robin Donaldson, of Donaldson+Partners, who recently completed an expansive, concrete-and-glass residence in California with sweeping hallways and atriums and sound-sensitive sitting nooks that evokes a modernist chapel and a transcendent James Turrell installation in equal measure. (In a full-circle moment: Turrell’s Roden Crater served as the backdrop for one of Kanye West’s Sunday Service gospel performances in the 2019 IMAX documentary, Jesus Is King.) The stairwell of this Melbourne house by LLDS looks like it could be inside the Goethenaum.In her 2017 book, Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives, architecture critic Sarah Williams Goldhagen makes the case for just how profoundly our environments shape our experiences as humans on a neurological level. (Goldhagen is also an expert on Louis Kahn, who himself dabbled in midcentury church design and seemed to have a similar stance on how architecture shapes identity, once saying, "There’s something about a 150-foot ceiling that makes a man a different kind of man," after visiting the Roman Baths of Caracalla.) Sparse, spacious interiors clad in expensive natural materials—whether in a chapel, an in-home meditation room, or a foyer—can foster a soothing atmosphere that’s a psychological luxury. Those same elements also tend to signal wealth (cue: the minimalist look in recent years given the moniker "quiet luxury").Of course, minimalist aesthetics have long cycled in and out of fashion—and, on its own, the use of raw materials and toned-down palettes, or sculptural walls and towering, sky-lit ceilings, isn’t novel or distinct to a specific type of built environment. But in an era rife with "technostress," political turmoil, and worsening climate anxieties, as well as the ongoing disappearance of "third places," it seems like the combination of elements that make our homes feel transcendent is a little bit more holy.Top photo of the Rothko Chapel interior by Smiley N. Pool/Houston Chronicle/Getty Images Source link

0 notes