#rehabilitation and justice and helping the poor at least be the ones in charge??

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The pushback to the term "cultural Christianity" from atheists is real odd to me because, as someone who has been an atheist since 13, only ever went to church a handful of times never with my own family (made a note never to sleep over at that friends house on a Saturday again bc I HATED church it smelled like shit, was boring, pews are uncomfortable as fuck, and the religious people I knew were all wildly misogynistic and I've never been here for being told I was less of a person for being Born Like This), and generally had no actual connection to Christianity in a meaningful way but still only knows Christian mythology, has been steeped in Christian values I had to untangle, and my religious understandings are still deeply Christian.

Like Ive never paid attention to the bible, church, Jesus, Christian teachings, or whatever but if you asked me about any religion the one I'll reliably know the most about is Christianity. I don't know why atheists are offended by being called culturally Christian because they have bad blood with the religion because like sorry bruh that doesn't mean you're less indoctrinated by Christian values if the culture you grew up in is predominantly Christian. In fact I'd say that religion being this ubiquitous in the culture regardless of anyone's consent to exactly ONE religion being shoved down our throats is reason to team up with other religious folks who ALSO don't like being constantly evangelized to by the culture at large, not a reason to throw a fit because you don't like being tied to a religion that is so ingrained into the culture that shit like "oh my god" and "Jesus Christ" are common expressions of surprise regardless of how atheist you are. Like surely I'm not the only atheist to notice the shocking amount of cultural religious shit that works it's way into my life and speech despite having not set foot in a church since I was like 10, and I can't remember the last time I was in one before that.

Idk man cultural Christianity seems like a pretty damn useful term to describe my relationship with a religion I never fully bought into and then actively rejected as a child yet still hold weird connections to and knowledge of just because Christianity is so baked into the culture I grew up in like it or not. If you want to be mad, be mad at the Christians who stole your freedom from religion from you, not usually religious minorities who discuss cultural Christianity and how it damages them too.

#winters ramblings#like breh i HATE how much christian bullshit ive had to detangle from my life. like the idea of sin and punishment for example#id say a LOOOOOT of discussion regardless of religion leans towards a Christian understanding of the pridon system#prison is basically a recreation of hell on earth where youre supposed to go to burn off your sins in your 10x10 cell#now i gotta say not all Christians buy inti the styke of punishment and sin i know normal well adjusted Christians#but for the most part a HUGE portion of shit comes with a helping of cultural Christianity. but prison is probably the best example#hell any discussion of punishment relies on a distinctly christian flavor of 'atone for your sin or be doomed forever"#repubs bitch about so called cancel culture but thats just how Christians act towards sin lmao they do it too#except they choose shit you didnt ACTIVITY make a choice about like being gay to condem you to hell.#cant be mad that twitter cancels people for small shit like a crap joke if you actively subscribe to the same belief system#and are only mad bc that logic is applied to YOU now. anyway i could do without this logic in activist spaces#or ANY spaces being doomed forever over sin is only one way to do Christianity. like damn can the ones who like#rehabilitation and justice and helping the poor at least be the ones in charge??#regardless ive never been a Christian and barely have a meaningful connection to the religion. whuch is why i find it rather salient#that i still have this deep connection and knowledge of something i ACTIVELY REJECTED at 13#do you know HOW MUCH i had to have been indoctrinated into this shit with as LITTLE of a connection to organized religion as i do??#the fact i have ANY connection at all is kind if fucked honestly it shows you really REALLY do not get to choose#your religious leanings unless youre actively ANOTHER RELIGION BESIDES CHRISTIAN otherwise tough tiddy#you get to be Christian By Default and i don't like it either. but when i see jewish people talking about it#i know EXACTLY what they mean because i dont like my connection to a religion i never believed in and rejected at 13 either#i don't like that my choice to reject Christianity was stolen from me by such a ubiquitously christian culture#im not mad at jews for pointing this out im mad at christians for stealing my freedom of choice

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

And they WILL replace one cage with another.

Even if we keep the topic closely focused on mental health,

How mental health is treated in the criminal justice system is awful, and sending police on calls about mental health crises increases the rate of violent conflict and arrest.

We've experienced this first hand, twice. We're very lucky that family was around both times to de-escalate and persuade them out of arresting me, and that they were able to do so. There's countless stories of families or friends of a mentally ill person trying to explain to police that the person in crisis is not a threat, only for police to still arrest them or do much worse.

So what about prisons? 43% of people in state prisons have been diagnosed with a mental disorder. That means there's probably an even higher number that would qualify as mentally ill based on our society's understanding of it. And meanwhile 74% of people in state prisons haven't received any mental health care (same source as previous link). Regardless of your opinion on mental health care, you can see that it's unfair and extremely hypocritical to the justice system's purported values of not convicting someone without mens rae, and to providing appropriate resources to someone who's criminal behavior was caused by mental illness.

Part of the issue there is how the courts define mens rea, but the much larger problem is that laws are not created to minimize harm. They are created to punish anyone that the government thinks is deserving of it. (x, x, x, x, x) (each source deals with a contributing concept (or body of evidence to a contributing concept) to this conclusion. If you read the sources and come to a different conclusion, that is okay)

Side note: Ask any criminal justice classroom what the most important theories of punishment are (theories of what the criminal justice system should hope to achieve, the most effective or moral ways to deal with crime/a criminal) and in my experience the majority of students, but especially cops, ex-cops, or aspiring cops, will argue for retribution and deterrence (despite these being thoroughly proven to not help), and actively denounce rehabilitation or interventions for prevention. "These people deserve to be punished! We shouldn't be helping criminals." is a disturbingly common refrain.

If you ban involuntarily hospitalization but not incarceration, they will just keep putting us in prisons.

Like they already do, when they can find an excuse for it. This is really easy when they can categorize an entire disorder as dangerous or criminal. For example, if I'd, gotten charged with resisting arrest in either of those incidents with the police, an ASPD diagnosis justifies harsher sentencing as "incapacitation" since we're seen as dangerous, and having ASPD is not seen as a mitigating factor against mens rea, it's seen as an aggravating factor. We have other mental health issues that might mitigate, depending on various factors, but that's beside the point.

Please also consider that as of 2018, around 8% of prisoners in the US were housed in private, for-profit, prisons, which sounds like not a lot until you consider that this is 116,000 prisoners (same source as previous) and that over 3,100 corporations profit from the prison system.

There is a monetary incentive for these corporations to lobby to keep justice punitive and to keep laws that justify mass incarceration of marginalized groups, especially POC, the poor, and the mentally ill.

There is also a cultural incentive for these laws, but that is a whole essay unto itself just to scratch the surface of it.

I'm aware my ideas are too extreme for the average US democrat/liberal, but please at least consider some of these points.

If you're interested in further reading I have a Google doc with more source recommendations here. It is categorized by subject.

Antipsychiatry must include prison abolition as a guiding value. I'm tired of seeing people organize around antipsychiatry while throwing other incarcerated people under the bus. Criticizing psych wards for "treating us like criminals while we haven't broken to law" ignores the real problem: that the tools of restraint, strip searches, solitary confinement, and incarceration are violent no matter who they are forced upon. No one should be treated that way, no matter what form of incarceration you're surviving, whether that's in a prison, a psych ward, or any other institutions of total control. We are not inherently morally better than people incarcerated in prisons, and we have to build intentional solidarity to ensure we don't just replace one cage with another.

#mental health#prison abolition#i spent too much time on this :/#i wanted to write something anyways though and OP's post reminded me#long post#for blocking purposes

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Almasi for President

so in about 12 to 16 years, i am running for president. i do not believe the world will have ended then, though i do believe things will be different. hoping for better, not, not expecting worse. our system is broken. all of the systems are broken. the government is corrupt. the justice system is corrupt. those in charge are turning blind eyes, covering things up, and allowing the fall of our country. i will not be surprised if a civil war commences; although i'm also thinking they are going to really create and push for a purge. we are in real trouble then. that just goes back to what i said, are you standing for something or dying for nothing?

people were excited for biden to win. and i have to say, i was not one of them. biden seems like another puppet to me. obama was a puppet. he was his vp. crazy how biden is president and he has a black female vp now. that sounds like a win huh? wrong, she contributed to the failed prosecution of the officers who murdered Oscar Grant. that went over everyone's head during the election though. trump was just so bad had to get him out. biden is anti LGBTQ+. everyone wanted to put it on trump folks getting rowdy and such however, biden won and nothing changed.

trump's slogan was "make america great again." personally, i think he could have. trump's a businessman and to say the least, entertainment. they gave trump four years, why do you think they didn't renew his contract? because he was playing them. trump is a classist. he doesn't like poor people. personally, i think he just believes hardwork pays off, his did and so he just holds everyone to the standard he held himself. there are circumstances, however i think that's fair. he said all this racist shit everyone got mad. yet, he won by a landslide because the country said they would still rather this "bigoted, racist, sexist, classist asshole" than a woman. then the country complained the whole time. he exposed america and instead of society shining light and doing something they continued to do what we have been doing; pointing blame.

the system has failed us. the system failed us a long time ago. all trump did was present a call to action. the one thing i can give rednecks is they patriotic as fuck. they want the america they invision type shit. i feel like melanated people in general struggle with that because america never felt like home. america never wanted us here. but the fact of the matter is, this all we know. this is home now. there are 3 real options. 1. go back to where your bloodline stems. 2. sit and conform, hope they dont get you. 3. defend your rights, your home, and your people; come out on top or die trying. you have to pick something though. we have to do something because they those set to protect us are out to get us.

we do not have a democratic government not even a representative democracy like we once thought. sorry if you were today years old when you found out. we operate out of a republic; a constitutional federal republic. what's the difference? in a democracy, all that voting that we do, matters. even if it was a representative democracy. we would have representatives to disclose our decisions. the electoral college makes final decisions on elections.

a constitutional federal republic means that the constitution which is the law of the land governs the land. if this is the law of the land, why do we have sub laws? the constitution needs to be amended. want to fix the race and inequality issues? let me tell you how, real easy fix. call a convention. take out any amendment that gives rights to people AND reword the beginning anyway folks see fit so that women and americans from all ethnic backgrounds get the same level of respect and rights. there will always be an unspoken division until things like that are rectified. before black people got rights we were not even counted as complete people, simply 3/5s of a person. life liberty and the pursuit of happiness. these are unalienable rights. my very existence guarantees me these rights.

the judicial system coupled with the criminal law system are hopeful, and still in need of reform. prisons are privately owned institutions, which are supposed to be forms of rehabilitation. instead, they are condemning people and treating them inhumanely; creating the same environment they were in on the outside, on in the inside conditioning them to be stuck in these ways as means of survival and then continue to place blame on them. officers need to take crimes more seriously. people are people, bias, prejudices, and profiling have no place in the workplace. officers are corrupt, arresting kids for selling, who just are trying to help their mother with the bills, then turning around and selling it back out on the streets. officers are wrongfully convictind and killing predominately (as far as the media is broadcasting) though not only melanated people. on top of that, they are walking free. lives are being lost and they arent even losing their jobs. tax dollars are going towards keeping them safe. however, if a civilian shoots a cop. up the river for them.

lawyers aren't fighting hard enough. especially defense attorneys. it is fairly simple to get a conviction with the right information, proving innocence is always a bit more complicated. the problem is that attorneys get too big eyed. they looking at how to get their clients off, accountability is another taboo in this society. there are a multitude of people who are innocent behind bars, as well as those who received heinous outrageous sentences. that is not right.

people factor more than necessary when trying to make a decision, yet they ignore the things that remind them a person is human. its this art contest over who can paint the best picture of the defendant. which story is easy for a jurors bias to sway? how people look matters. and it shouldn't. our government since the building of america, has created dividing markers.

just like with royal kingdoms, the wife couldn't have things of her own. her role was cleaning, cooking, taking care of the kids, and whatever else was asked of her. if there was a divorce, the woman got nothing. they had no rights. imagine being the first born as a female in a royal family and being told you can't have your kingdom, correction you can but you must marry to get it. then if you get married the new king running things not you. what is that? its called patriarchy. our government is run off a patriarchy as well.

so i never really believed there could be like a true separation of church and state because every law and decision made was based on people's morals and beliefs. there is supposed to be a separation of church and state yet, due to people's religious beliefs gay marriage had to get legalized, despite there being no law for heterosexual marriage. would that not make it illegal? since gay marriage had to be legalized though there was not a law for it either? then on top of that, how do you make it a law, and still for religious reasons, ministers and such can refuse? there are always stipulations and hinderances for the rights of those who are not white men.

ABORTION: i really do not know why we are still having this conversation. its literally conversations like this that have me looking at americans like--- seriously? once again there should be a separation of church and state. so religion cannot be a reason to outlaw it. how can you put out a law that dictates what someone can do with their body? all of life, i mean every part of life should be pro-choice. its just that simple. Pro-Choice. i am all for the right to decide for yourself. and men want to feel a way about women making that decision on their own. and while i do stand behind the fact that ultimately it is the womans decision, that does not mean she can't listen to an opinion. it is a part of the woman, literally grows inside of her an entire being. and fathers can just dip out and folks will just look at the mom and suddenly she should just become super woman. the pressure that comes with having a child is enough on its own. like thats a being that is dependent on you. some people are honest with themselves and know they arent ready or dont want it. all they need is support. the mental toll life takes on us is huge as well. still people do not consider that at all.

there is no point of incarcerating people, if they have still lost a chance at a decent life once they get out. jail is for rehabilitation. they go, do their time and then they are supposed to be allowed to try again. our government knows nothing of redemption, that's why all the top leaders go through so much to hide their dirt. they crucify civilians trying to make themselves seem superior, really they are just like you and i. almasi for president. im going to save the world.

-Almasi

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exchanges and Compromises - Chapter 1

a/n: So I found a fic that has more than a dozen chapters and is finished. Kind of. It’s going to be part one of an alternate universe. But as far as part one goes, it’s finished. So I’m posting it and fixing it as I go. Yay.

A fated night, 20 years ago - so everybody thought and believed. A fated night that brought Dr Thomas and Mrs Martha Wayne, along with their 10-year-old son, Bruce, to the Cinema at Park Row to watch an old movie rerun. A fated night in which Dr Wayne had forgotten his wallet at the concession stand, and the concession attendant had chased him as they got out of the theater to head back home. It was fate that had stopped Dr Wayne to praise the 17-year-old Lucius Fox who had taken the schedule from his coworker who had played truant for the night - and handed him a thank you speech and a fifty out of said wallet along with his business card and offer for Lucius to come over to Wayne Enterprises whenever he could. Dr Wayne commented that honest man was too rare in Gotham City for him to not grab hold of one it as soon as he saw Fox.

The delays thus made it possible for Alfred Pennyworth, their butler, to arrive just in time to pick them up, just as they were held under gunpoint by a junkie who was trying to rob them. Alfred, a war veteran, had not hesitated in drawing his own gun when he saw the procession, and shot the man who were going to rob Dr and Mrs Wayne.

A fateful night of young Bruce Wayne's first introduction to crime, and the realization that his city - Gotham City - was fully invested with petty crimes. And as his father had said some minutes earlier: an honest man is rare in Gotham.

Alfred's' gun did not kill the wannabe-robber. Yet it shocked Bruce enough to understand that his life has been one of privilege. They did not have to wait in the chilly night or at the precinct for the cops, instead the cops - a young Detective James Gordon - went to their manor for their statements. Joe Chill, the robber, was arrested by the paramedics and police summoned by Alfred. At the trial, he had cried and told the court he was sorry, and that he was rehabilitated while in prison. He was to serve three years for attempted robbery with deadly force.

Bruce Wayne understood well just how lucky he was. He went on to follow his mother's footstep into business school instead of his father, because the blood spurting out of Chill's wound as he had gotten shot had traumatized him. He would not tell his father, but the medical profession is not something he trusted. He was even younger when he had watched his mother lost the infant that was to be his little brother and got hospitalized for it; followed by the death of their older butler, Jarvis, due to heart attack not long after. When Jarvis' son arrived at the manor, he barely could contain his delight. To the then-four-year-old, Alfred looked young enough to play with - albeit having just as cool and stern mannerism as Jarvis. Apparently, he had worked in theaters. Bruce was excited then. And Alfred became his closest companion through the years.

Ten years after that fated night, Gotham City had continued to deteriorate. It has held the position of the worst city to live in in the US for ten years in a row, regardless of everything Dr Thomas Wayne has done to fix it. Bruce, now in business school, has offered ideas that were quickly implemented by his father; his mother's brother, uncle Philip; and everyone at Wayne Enterprises. Some of the ideas rooted and sprouted, only to be killed a little while later by Gotham's own citizens who had claimed that they do not trust people like the Waynes. One of the ideas was to send Lucius Fox to college, and then hire him by the time he finished his engineering studies. Fox was one of Bruce's ideas that hit the jackpot but nearly got drowned by Fox's own colleagues.

The rich people are all corrupt, they had said during a random polling done by an external agency. Regardless of how much money the Waynes owned, or the fact that if it hadn't been for the Waynes, at least 70 percent of Gothamites would not have had a job.

"They are rebelling through crime just for the sake of pettiness," Dr Wayne commented dryly, as news about a robbery that was done by the Red Hood Gang blared on TV. "They seriously thought that robbing banks could distribute wealth instead of working hard for it."

Bruce just sighed. He couldn't understand it, either, how people were robbing banks and thought they would make a change. "Obviously, their simple minds only think that when you rob a bank belonging to one of The Families, we would be poor. They obviously has no notions of insurances and the fact that they were only stealing from their own neighbors." he commented.

The Waynes had come from a very long line of riches, all the way back to the Old World. It had been the Waynes who initially came up with the plans to build Gotham. The other families; the Kanes, a.k.a. his mother's forefathers; the Cobblepotts; the Dumases, and Crownes - all had acquired their immense wealth only after Gotham had stood.

There are only three families remaining out of Gotham's original founding families, with the rest diluted or got themselves renamed with lack of successors. Like the Dumases - now Galavan; Crownes - now Elliotts. Other families would rise, such as the Drakes, previously unknown and inventors of new medicines and amateur archaeologist - also in-laws of the Galavan; the Belmont family, who made their money in banking; the Arkham family who founded the Asylum for the Psychologically Impaired just at the outskirts of the city and so on. They truly made Bruce believe that with hard work and perseverance, anyone could get rich in Gotham.

He wondered, often, what would it take to turn a common man to change - be it for the better or worse. The criminals who got caught would blame it on a 'really bad day', and ignored the fact that their crime would make another person get a bad day; and thus perpetuate the circle.

There were still good people in Gotham, Bruce knew. People like his father, who would keep trying to open new manufacturing facilities. He would often be hindered by the anti-monopoly law that barred him from owning every manufacturing facilities that supply to Wayne Enterprises' own manufacturing line. But he would try, anyway, by making alliances with a number of the other business owners; establishing schools so that kids could grow up to be business owners; establishing free training seminars to allow people to get certifications for their skills; and so on and so forth.

Still, Gotham, the city with the highest job-hazard related incidents, seemed to want to resist him. The factories owned by unscrupulous people would continue to neglect their employees' safety, and caused incidents, that in the long run, prevented said factory to get the safety certification needed to supply Wayne Enterprises, and therefore would end up with the factory going bankrupt.

Then there were people like Dr Leslie Thompkins, a physician who was a classmate of Dr Wayne's. She opened a free clinic at the worst part of Gotham, Crime Alley. Dr Wayne would provide the supplies free of charge for her. And then people would try to rob the clinic. Bruce couldn't understand that, nor could he understand Dr Thompkins' insistence to remain there and use no security measures.

He understood the needs, alright. Wayne Enterprises has built a number of hospitals for low-income people. They have hired numerous good physicians - only to have said physicians quit or killed when gangs after gangs tried to rob the hospital. The ones remaining in those hospitals are the ones with bare minimum training or couldn't care less. Not good enough. Never good enough. None of them were Leslie Thompkins, who had skills and heart to do good all the way, by any means possible.

None of them was James Gordon, either - the Detective that was sent to question the Waynes and Alfred following the robbery. Bruce came to knew Gordon's background when he again met the man after being held at gunpoint for a robbery of his car. The one thing Gordon said had struck a note in Bruce's heart; "Just because you're wealthy, Bruce, doesn't mean you deserve to be robbed. Justice is justice, wherever levels of society you're in."

Gordon, Bruce knew, had come from Chicago; where he was 'boxed' - being sent to a boxed corner office cut off from the rest of his squad - for being too honest and refusing to let go of an investigation that involved the city's bigwigs. Gordon has two children; one biological son called James Junior, the other a daughter he had adopted when his brother and wife passed away. Her name is Barbara, and her redhead matched Gordon's, making people believed she was Gordon's biological child instead of the blond James Junior.

Gordon and his family seemed happy being in Gotham, much to Bruce's confusion. He noted that while visitors often found happiness in Gotham, most of its born-and-bred residents seemed to feel otherwise. Again, Gordon's comment - as he and Bruce started to befriend each other - made sense, "Some people just don't have it in them to appreciate what they have and think that the grass is always greener everywhere else; except in their own ignored pastures."

Bruce had often quietly promised himself that he would keep trying to help Gotham, so the city can live beautifully; and the people residing within her will realize that their home is beautiful and thus needs to be loved. With that in mind, he turned his focus in his school. There has got to be some way to keep Gotham's people happy, safe, and maybe even grateful.

#Bruce Wayne#Thomas Wayne#Martha Wayne#James Gordon#alfred pennyworth#Barbara Gordon#Dick Grayson#Jason Todd#Tim Drake#Damian Wayne#Twist of Fate!AU#JayTim#Batman

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Efforts to Keep COVID-19 out of Prisons Fuel Outbreaks in County Jails

When Joshua Martz tested positive for COVID-19 this summer in a Montana jail, guards moved him and nine other inmates with the disease into a pod so cramped that some slept on mattresses on the floor.

Martz, 44, said he suffered through symptoms that included achy joints, a sore throat, fever and an unbearable headache. Jail officials largely avoided interacting with the COVID patients other than by handing out over-the-counter painkillers and cough syrup, he said. Inmates sanitized their hands with a spray bottle containing a blue liquid that Martz suspected was also used to mop the floors. A shivering inmate was denied a request for an extra blanket, so Martz gave him his own.

“None of us expected to be treated like we were in a hospital, like we’re a paying customer. That’s just not how it’s going to be,” said Martz, who has since been released on bail while his case is pending in court. “But we also thought we should have been treated with respect.”

The overcrowded Cascade County Detention Center in Great Falls, where Martz was held, is one of three Montana jails experiencing COVID outbreaks. In the Great Falls jail alone, 140 cases have been confirmed among inmates and guards since spring, with 60 active cases as of mid-September.

By contrast, the Montana state prison system has the second-lowest infection rate in the nation, according to the COVID Prison Project. No confirmed coronavirus cases have been reported at the men’s prison out of 595 inmates tested. The women’s prison had just one confirmed case out of 305 inmates tested, according to Montana Department of Corrections data.

One reason for the high COVID count in jails and the low count in prisons is that Montana for months halted “county intakes,” or the transfer of people from county jails to the state prison system after conviction. Sheriffs in charge of the county jails blame their outbreaks on overcrowding partly caused by that state policy.

Restricting transfers into state prisons is a practice that’s also been instituted elsewhere in the U.S. as a measure to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. Colorado, California, Texas and New Jersey are among the states that suspended inmate intakes from county jails in the spring.

But it’s also shifted the problem. Space was already a rare commodity in these local jails, and some sheriffs see the halting of transfers as giving the prisons room to improve the health and safety of their inmates at the expense of those in jail, who often haven’t been convicted.

The Cascade County jail was built to hold a maximum of 372 inmates, but the population has regularly exceeded that since the pandemic began, including dozens of Montana Department of Corrections inmates awaiting transfer.

“I’m getting criticized from various judges and citizens saying, ‘Why aren’t you quarantining everybody appropriately and why aren’t you social-distancing them?’” Cascade County Sheriff Jesse Slaughter said. “The truth is, if I didn’t have 40 DOC inmates in my facility I could better do that.”

Unlike convicted offenders in state prisons, most jail inmates are only accused of a crime. They include a disproportionately high number of poor people who cannot afford to post bail to secure their release before trial or the resolution of their cases. If they do post bail or are released after spending time in a jail with a COVID outbreak, they risk bringing the disease home with them.

Andrew Harris, a professor of criminology and justice studies at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, said he finds it troubling that more attention is not paid to the conditions that lead to COVID outbreaks in jails.

“Jails are part of our communities,” Harris said. “We have people who work in these jails who go back to their families every night, we have people who go in and out of these jails on very short notice, and we have to think about jail populations as community members first and foremost.”

Some states have tried other ways to ensure county inmates don’t bring COVID-19 into prisons. In Colorado, for example, officials lifted their suspension on county intakes and are transferring inmates first to a single prison in Canon City, Department of Corrections spokesperson Annie Skinner said. There, inmates are tested and quarantined in single cells for 14 days before being relocated to other state facilities.

Outbreaks are also occurring in county jails in states that never stopped transferring inmates to state prison. Several jails in Missouri have experienced significant outbreaks, with Greene County reporting in mid-August that 83 inmates and 29 staffers had tested positive. Missouri Department of Corrections spokesperson Karen Pojmann said the state never opted to stop transfers from county jails, likely because of a robust screening and quarantine procedure implemented early in the pandemic.

At least 1,590 inmates and 440 staff members have tested positive for COVID-19 in Missouri’s 22 prison facilities since March, according to state data. The COVID Prison Project ranks Missouri’s case rate 25th among the states — better than some states that halted inmate transfers, including Colorado, Texas and California.

The halting of transfers was a critical part of the response by officials in California, whose prisons have been among the hardest hit by COVID-19. An outbreak at San Quentin State Prison this summer helped spur Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom to order the early release of 10,000 inmates from prisons statewide.

Stefano Bertozzi, dean emeritus at the University of California-Berkeley School of Public Health, visited San Quentin before the outbreak, and afterward helped pen an urgent memo outlining immediate actions needed to avert disaster. He recommended halting all intakes at the prison and slashing its population of 3,547 inmates in half. At that point, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation was already more than two months into an intake freeze.

Overcrowding has long been an issue for criminal justice reform advocates. But for Bertozzi, the term “overcrowding” needs to be redefined in the context of COVID-19, with an emphasis on exposure risk. Three inmates sharing a cell designed for two is a bad way to live, he said, “especially for the guy who’s on the floor.” But if those cells are enclosed, they offer far better protection from COVID-19 than 20 inmates sharing a congregate dorm designed for 20.

“It’s how many people are breathing the same air,” Bertozzi said.

Some California county jails struggled. In July, inmates in Tulare County’s facility, where 22 cases had been reported, filed a class action suit against Sheriff Mike Boudreaux alleging he’d failed to provide face masks and other safeguards. U.S. District Court Judge Dale Drozd ruled in favor of the inmates in early September, directing Boudreaux to implement official policies requiring face coverings and social distancing.

California resumed county intakes on Aug. 24 following the development of guidelines designed to control transmission risk and prioritize counties with the greatest need for space. But a huge backlog remains: 6,552 state inmates were still being held in county jails as of mid-September, according to corrections officials.

In Montana, the number of inmates at county jails awaiting transfer to prisons and other state corrections facilities was 238 at the beginning of September, according to state data obtained through a public records request.

Montana and county officials butted heads over delays in inmate transfers before the coronavirus, but the pandemic has increased the stakes.

“Once we had the issue with the pandemic and we had to maintain space for quarantining and isolating inmates, then it became even more critical because the space wasn’t really available,” Yellowstone County Sheriff Mike Linder said.

Montana Department of Corrections Director Reginald Michael acknowledged to state lawmakers in August that halting county intakes places a strain on counties but said it was “the right thing to do.”

“This is one of the reasons why I think our prisons are not inundated with the virus spread,” he told the Law and Justice Interim Committee.

Committee Chairman Rep. Barry Usher, a Republican, gave Michael his endorsement: “Sounds like you guys are doing a good job keeping it controlled and out of our prison systems, and everybody in Montana appreciates that.”

Since then, Montana officials have transferred up to 25 inmates a week, but they continue to block transfers from the three counties with outbreaks: Cascade, Yellowstone and Big Horn.

Martz dreaded the thought of COVID-19 following him out of jail. So much so that, after his release in early September, he walked to an RV park, where his wife met him with a tent.

Despite having tested negative for the virus prior to his release, he self-quarantined for a week before going home. The hardest part, he said, was not being able to immediately hug his 5-year-old stepdaughter. It “sucked,” but it’s what he felt he had to do.

“If somebody’s grandpa or grandmother had gotten it because I was careless and they ended up dying because of it, I’d feel horrible,” said Martz, who has returned home. “That’d be a horrible thing to do.”

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

from Updates By Dina https://khn.org/news/efforts-to-keep-covid-19-out-of-prisons-fuel-outbreaks-in-county-jails/

0 notes

Text

Why we need a more forgiving legal system

The Supreme Court on March 12, 2019. | Jonathan Newton/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Harvard law professor Martha Minow on the possibilities of restorative justice.

The American justice system’s approach to crime seems to be: Lock up as many people as possible. This is one of many reasons why we’re the most incarcerated country in the world.

Punishment has a role in any criminal justice process, but what if it was balanced with a desire to forgive? What if, instead of locking up as many people as possible, we prioritized letting go of grievances in order to create a better future for victims and perpetrators?

These ideas are central to a growing “restorative justice” movement in America, which seeks to bring together criminals, victims, and affected families as part of a process of dialogue and healing. Think of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission as a model for this approach to justice.

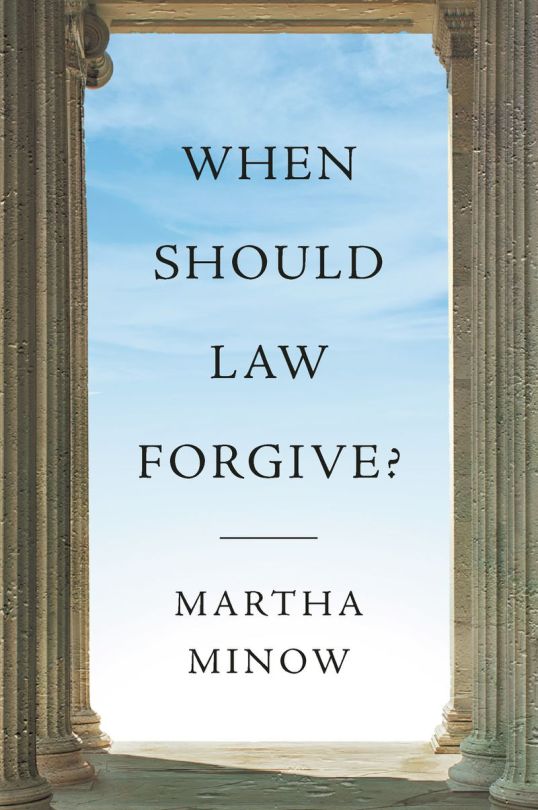

A new book by Harvard law professor Martha Minow, titled When Should Law Forgive?, explores how the restorative justice philosophy might be scaled up and applied to the broader criminal justice system. Minow was dean of Harvard Law from 2009 to 2017 and is known for her work on constitutional law and human rights, especially the rights of racial and religious minorities.

Minow’s book is very much what the title implies: a plea for a justice system that emphasizes forgiveness over resentment, resolution over punishment. It’s not a call for abolishing punishment altogether, but it is an attempt to challenge some of our most basic assumptions about law and order.

What we have now, Minow argues, is a system that forgives some and not others, that favors the powerful over the marginal. And the only way to change it, she concludes, is to rethink the incentive structure that guides our entire criminal justice process.

I spoke to Minow about what that change might look like, whether it’s compatible with the American philosophy of justice, and why some people have reservations about abandoning the status quo.

A lightly edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Sean Illing

The law, as you point out in the book, already forgives, but it’s very selective about when and who it forgives. Who gets forgiven now and why?

Martha Minow

One of the central reasons to write this book is that many of the inequalities reflected in the distribution of power in this country help explain who gets forgiven and who doesn’t, particularly when there’s discretion that’s given either to a judge or to some other law enforcement official, like a police officer or a prosecutor.

When there’s discretion, then the biases of the individual come into play. One of my favorite cartoons shows a judge with a big bushy mustache and a large nose looking down from the bench at someone with the exact same mustache and nose saying obviously not guilty.

There’s an understandable but dangerous tendency to identify with people like ourselves and to not identify with people who are different. Developing a jurisprudence of forgiveness is partially about developing criteria for judging when and how discretion is exercised.

Sean Illing

Can you give me an example of a type of person or institution that receives forgiveness now?

Martha Minow

Right now, for example, we have a bankruptcy code that allows a for-profit college or university to declare bankruptcy but does not allow the students who took out loans to go there to declare bankruptcy. That reflects a political judgement about who or what can be forgiven. And it’s an expression of who has the power to lobby in this country, of who has the power to influence legislation.

We should be critical of these sorts of imbalances and fight for a system that extends the same sense of charity to less-powerful individuals and institutions.

Matt Jonas/Digital First Media/Boulder Daily Camera via Getty Images

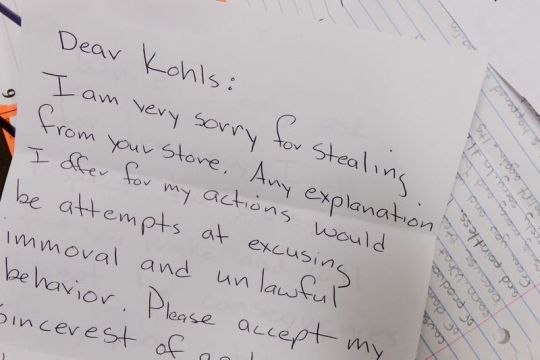

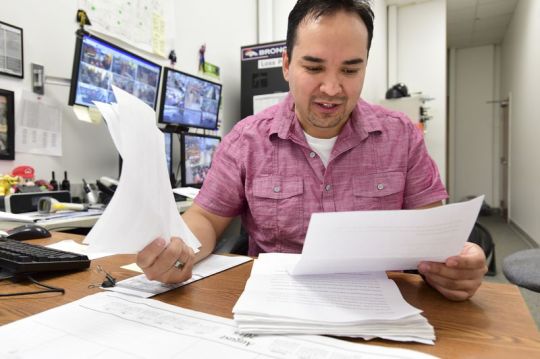

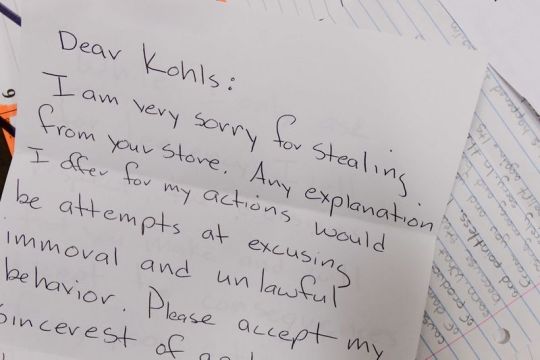

Loss Prevention Supervisor Lonnie Hernandez looks over some of the 55 letters he has received from shoplifters that have been through the Longmont Community Justice Partnership in Longmont, Colorado on August 19, 2016.

Matt Jonas/Digital First Media/Boulder Daily Camera via Getty Images

A letter Lonnie Hernandez received from a shoplifter is seen on his desk. Part of his organization’s restorative justice program includes offenders writing letters apologizing for their crimes.

Sean Illing

What are some crimes right now for which there is no mechanism of forgiveness but you think there should be?

Martha Minow

America is the most incarcerating country on the planet, and one consequence of that is the presence of fines and fees that are layered on top of people who are convicted of a crime. Many systems actually impose on the criminal defendant the cost of a probation officer or the cost of monitoring anklets with which they’re discharged, and the fines and fees accumulate.

These are often people without a lot of resources and there’s no forgiveness mechanism and therefore they can face even more incarceration for nonpayment. I think that’s an area where absolutely we should have mechanisms of forgiveness. Although there’s some efforts now to do just this, it’s not nearly enough.

Sean Illing

Who would you say gains the most from a more forgiving legal system?

Martha Minow

Not to be too simplistic, but I think we all do. In an interpersonal context, the one who forgives often gains as much if not more than the one who was forgiven. To let go of a grievance is to be freed in many ways.

More transparency and a more forgiving and pragmatic approach to crime also benefits the entire community because it constrains law enforcement and prevents the needless break-up of families, which is what incarceration does.

Sean Illing

There’s another prosecutor problem, though, which you discuss in the book and which New York Times legal reporter Emily Bazelon has written about. We have a significant number of overzealous prosecutors, people who are benefiting politically from from locking up as many people as possible. How do we address that?

Martha Minow

The emergence of progressive prosecutors is encouraging. It’s part of a broader movement to support and demand the election of people who are very clear about their intention to be less punitive and to pursue alternative models like restorative justice.

Another technique, of course, is to not have elected prosecutors at all, which is flawed for countless reasons. We can also develop ways to measure and reward other indicators of success besides how many people did you lock up. For example, we should pay more attention to how many people end up falling back into the criminal justice system after their initial contact with it.

If prosecutors are just tossing people in jail who continue to commit crimes after serving time, well, that’s obviously bad. But that’s just not part of the incentive structure right now.

Sean Illing

Do you worry that more forgiveness means prioritizing the interests of perpetrators over the needs of victims?

Martha Minow

I certainly do. And as much as I criticize mass incarceration, I do believe that we need vigorous law enforcement, and often the people most victimized by crime are the most disadvantaged. They’re poor people, people of color, people who are most likely to be targeted by violence. So while we need to talk about fairness, there are definitely dangers in taking the concerns of perpetrators too far. At the same time, we can’t let that concern get in the way of thinking more broadly about how to construct a more just, balanced, and forgiving system.

Sean Iling

Some people have raised concerns that there’s an imbalance in terms of our expectations about who should forgive and that simply calling for more forgiveness risks normalizing certain forms of oppression or violence. How do you respond to this?

Martha Minow

These are very important objections and I don’t think it’s accidental or unique to our society that people with relatively less power are either more likely to be expected to forgive than people with more power.

People of color and women in particular, at least in our society, have developed more muscles when it comes to forgiveness, even when they may be more often on the receiving end of harms. We see this now with the Me Too movement where very often someone who’s been identified as engaging in sexual assault or sexual harassment then expects their victims to forgive, and that’s often an expression simply of the power that they had in the first place.

I don’t think the problem here is forgiveness, though. Forgiveness is a resource every human being has and indeed every religion, every major moral philosophy, and every society has tried to cultivate. The real problem, as you suggested, is the unequal expectations around who should forgive and when.

Sean Illing

The idea of forgiveness seems at odds with our whole philosophy of justice in this country. Do we need a fundamental shift in how we think about justice and law?

Martha Minow

Every law student learns that there are multiple purposes of the criminal justice system. Deterrence of crime is one, incapacitation of people who are dangerous is another, but so is retribution and finally rehabilitation. Those are the four classic goals.

The United States doesn’t have a criminal justice system — we have many, many local fiefdoms of criminal justice systems and many of them have been moving away from rehabilitation for a long time and very much toward retribution and not even always thoughtfully using deterrence as a goal.

Since most of our system operates by plea bargain, much of it’s not even public. Prosecutors often work by stacking up as many charges as possible so that people will plead to something and then using that as leverage to press them into some admission of guilt and then some kind of punishment.

So how does that feed back into a deterrent system? It’s not clear. I think we’ve swung way out of balance from the goals that the system itself is supposed to have.

I think that we can learn some from other systems. I’m very encouraged when I hear that there are delegations from a city in the Midwest going to Norway or Finland to learn about how they engage in more restorative practices. There are increasing experiments in this country. The District of Columbia has decided to use restorative practices for its juvenile justice docket. I think there are a lot of people from a lot of different walks of life, different political persuasions, who are saying, “There’s something very broken here and we can change.”

Sean Illing

Let’s say we did shift to a more forgiving legal system, are there any trade-offs that concern you? Is there something our current system does well that we might lose if we made this change?

Martha Minow

I think we have to step back and recognize that we have too many people incarcerated and too many people in debt and we need a reset. That’s what I’m calling for.

But are there risks? Of course. One danger is that introducing more forgiveness into the system could further jeopardize the principle of equality under the law if it’s not applied fairly. If we don’t eliminate the imbalances we were talking about earlier, then more forgiveness could easily deepen the inequalities that already exist.

So, above all, we have to ensure that the benefits of a more forgiving system extend to everyone and not simply to the most powerful forces in the country. If we can do that, the country as a whole will be better.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/2XegO9Q

0 notes

Text

Why we need a more forgiving legal system

The Supreme Court on March 12, 2019. | Jonathan Newton/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Harvard law professor Martha Minow on the possibilities of restorative justice.

The American justice system’s approach to crime seems to be: Lock up as many people as possible. This is one of many reasons why we’re the most incarcerated country in the world.

Punishment has a role in any criminal justice process, but what if it was balanced with a desire to forgive? What if, instead of locking up as many people as possible, we prioritized letting go of grievances in order to create a better future for victims and perpetrators?

These ideas are central to a growing “restorative justice” movement in America, which seeks to bring together criminals, victims, and affected families as part of a process of dialogue and healing. Think of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission as a model for this approach to justice.

A new book by Harvard law professor Martha Minow, titled When Should Law Forgive?, explores how the restorative justice philosophy might be scaled up and applied to the broader criminal justice system. Minow was dean of Harvard Law from 2009 to 2017 and is known for her work on constitutional law and human rights, especially the rights of racial and religious minorities.

Minow’s book is very much what the title implies: a plea for a justice system that emphasizes forgiveness over resentment, resolution over punishment. It’s not a call for abolishing punishment altogether, but it is an attempt to challenge some of our most basic assumptions about law and order.

What we have now, Minow argues, is a system that forgives some and not others, that favors the powerful over the marginal. And the only way to change it, she concludes, is to rethink the incentive structure that guides our entire criminal justice process.

I spoke to Minow about what that change might look like, whether it’s compatible with the American philosophy of justice, and why some people have reservations about abandoning the status quo.

A lightly edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Sean Illing

The law, as you point out in the book, already forgives, but it’s very selective about when and who it forgives. Who gets forgiven now and why?

Martha Minow

One of the central reasons to write this book is that many of the inequalities reflected in the distribution of power in this country help explain who gets forgiven and who doesn’t, particularly when there’s discretion that’s given either to a judge or to some other law enforcement official, like a police officer or a prosecutor.

When there’s discretion, then the biases of the individual come into play. One of my favorite cartoons shows a judge with a big bushy mustache and a large nose looking down from the bench at someone with the exact same mustache and nose saying obviously not guilty.

There’s an understandable but dangerous tendency to identify with people like ourselves and to not identify with people who are different. Developing a jurisprudence of forgiveness is partially about developing criteria for judging when and how discretion is exercised.

Sean Illing

Can you give me an example of a type of person or institution that receives forgiveness now?

Martha Minow

Right now, for example, we have a bankruptcy code that allows a for-profit college or university to declare bankruptcy but does not allow the students who took out loans to go there to declare bankruptcy. That reflects a political judgement about who or what can be forgiven. And it’s an expression of who has the power to lobby in this country, of who has the power to influence legislation.

We should be critical of these sorts of imbalances and fight for a system that extends the same sense of charity to less-powerful individuals and institutions.

Matt Jonas/Digital First Media/Boulder Daily Camera via Getty Images

Loss Prevention Supervisor Lonnie Hernandez looks over some of the 55 letters he has received from shoplifters that have been through the Longmont Community Justice Partnership in Longmont, Colorado on August 19, 2016.

Matt Jonas/Digital First Media/Boulder Daily Camera via Getty Images

A letter Lonnie Hernandez received from a shoplifter is seen on his desk. Part of his organization’s restorative justice program includes offenders writing letters apologizing for their crimes.

Sean Illing

What are some crimes right now for which there is no mechanism of forgiveness but you think there should be?

Martha Minow

America is the most incarcerating country on the planet, and one consequence of that is the presence of fines and fees that are layered on top of people who are convicted of a crime. Many systems actually impose on the criminal defendant the cost of a probation officer or the cost of monitoring anklets with which they’re discharged, and the fines and fees accumulate.

These are often people without a lot of resources and there’s no forgiveness mechanism and therefore they can face even more incarceration for nonpayment. I think that’s an area where absolutely we should have mechanisms of forgiveness. Although there’s some efforts now to do just this, it’s not nearly enough.

Sean Illing

Who would you say gains the most from a more forgiving legal system?

Martha Minow

Not to be too simplistic, but I think we all do. In an interpersonal context, the one who forgives often gains as much if not more than the one who was forgiven. To let go of a grievance is to be freed in many ways.

More transparency and a more forgiving and pragmatic approach to crime also benefits the entire community because it constrains law enforcement and prevents the needless break-up of families, which is what incarceration does.

Sean Illing

There’s another prosecutor problem, though, which you discuss in the book and which New York Times legal reporter Emily Bazelon has written about. We have a significant number of overzealous prosecutors, people who are benefiting politically from from locking up as many people as possible. How do we address that?

Martha Minow

The emergence of progressive prosecutors is encouraging. It’s part of a broader movement to support and demand the election of people who are very clear about their intention to be less punitive and to pursue alternative models like restorative justice.

Another technique, of course, is to not have elected prosecutors at all, which is flawed for countless reasons. We can also develop ways to measure and reward other indicators of success besides how many people did you lock up. For example, we should pay more attention to how many people end up falling back into the criminal justice system after their initial contact with it.

If prosecutors are just tossing people in jail who continue to commit crimes after serving time, well, that’s obviously bad. But that’s just not part of the incentive structure right now.

Sean Illing

Do you worry that more forgiveness means prioritizing the interests of perpetrators over the needs of victims?

Martha Minow

I certainly do. And as much as I criticize mass incarceration, I do believe that we need vigorous law enforcement, and often the people most victimized by crime are the most disadvantaged. They’re poor people, people of color, people who are most likely to be targeted by violence. So while we need to talk about fairness, there are definitely dangers in taking the concerns of perpetrators too far. At the same time, we can’t let that concern get in the way of thinking more broadly about how to construct a more just, balanced, and forgiving system.

Sean Iling

Some people have raised concerns that there’s an imbalance in terms of our expectations about who should forgive and that simply calling for more forgiveness risks normalizing certain forms of oppression or violence. How do you respond to this?

Martha Minow

These are very important objections and I don’t think it’s accidental or unique to our society that people with relatively less power are either more likely to be expected to forgive than people with more power.

People of color and women in particular, at least in our society, have developed more muscles when it comes to forgiveness, even when they may be more often on the receiving end of harms. We see this now with the Me Too movement where very often someone who’s been identified as engaging in sexual assault or sexual harassment then expects their victims to forgive, and that’s often an expression simply of the power that they had in the first place.

I don’t think the problem here is forgiveness, though. Forgiveness is a resource every human being has and indeed every religion, every major moral philosophy, and every society has tried to cultivate. The real problem, as you suggested, is the unequal expectations around who should forgive and when.

Sean Illing

The idea of forgiveness seems at odds with our whole philosophy of justice in this country. Do we need a fundamental shift in how we think about justice and law?

Martha Minow

Every law student learns that there are multiple purposes of the criminal justice system. Deterrence of crime is one, incapacitation of people who are dangerous is another, but so is retribution and finally rehabilitation. Those are the four classic goals.

The United States doesn’t have a criminal justice system — we have many, many local fiefdoms of criminal justice systems and many of them have been moving away from rehabilitation for a long time and very much toward retribution and not even always thoughtfully using deterrence as a goal.

Since most of our system operates by plea bargain, much of it’s not even public. Prosecutors often work by stacking up as many charges as possible so that people will plead to something and then using that as leverage to press them into some admission of guilt and then some kind of punishment.

So how does that feed back into a deterrent system? It’s not clear. I think we’ve swung way out of balance from the goals that the system itself is supposed to have.

I think that we can learn some from other systems. I’m very encouraged when I hear that there are delegations from a city in the Midwest going to Norway or Finland to learn about how they engage in more restorative practices. There are increasing experiments in this country. The District of Columbia has decided to use restorative practices for its juvenile justice docket. I think there are a lot of people from a lot of different walks of life, different political persuasions, who are saying, “There’s something very broken here and we can change.”

Sean Illing

Let’s say we did shift to a more forgiving legal system, are there any trade-offs that concern you? Is there something our current system does well that we might lose if we made this change?

Martha Minow

I think we have to step back and recognize that we have too many people incarcerated and too many people in debt and we need a reset. That’s what I’m calling for.

But are there risks? Of course. One danger is that introducing more forgiveness into the system could further jeopardize the principle of equality under the law if it’s not applied fairly. If we don’t eliminate the imbalances we were talking about earlier, then more forgiveness could easily deepen the inequalities that already exist.

So, above all, we have to ensure that the benefits of a more forgiving system extend to everyone and not simply to the most powerful forces in the country. If we can do that, the country as a whole will be better.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/2XegO9Q

0 notes

Text

Why we need a more forgiving legal system

The Supreme Court on March 12, 2019. | Jonathan Newton/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Harvard law professor Martha Minow on the possibilities of restorative justice.

The American justice system’s approach to crime seems to be: Lock up as many people as possible. This is one of many reasons why we’re the most incarcerated country in the world.

Punishment has a role in any criminal justice process, but what if it was balanced with a desire to forgive? What if, instead of locking up as many people as possible, we prioritized letting go of grievances in order to create a better future for victims and perpetrators?

These ideas are central to a growing “restorative justice” movement in America, which seeks to bring together criminals, victims, and affected families as part of a process of dialogue and healing. Think of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission as a model for this approach to justice.

A new book by Harvard law professor Martha Minow, titled When Should Law Forgive?, explores how the restorative justice philosophy might be scaled up and applied to the broader criminal justice system. Minow was dean of Harvard Law from 2009 to 2017 and is known for her work on constitutional law and human rights, especially the rights of racial and religious minorities.

Minow’s book is very much what the title implies: a plea for a justice system that emphasizes forgiveness over resentment, resolution over punishment. It’s not a call for abolishing punishment altogether, but it is an attempt to challenge some of our most basic assumptions about law and order.

What we have now, Minow argues, is a system that forgives some and not others, that favors the powerful over the marginal. And the only way to change it, she concludes, is to rethink the incentive structure that guides our entire criminal justice process.

I spoke to Minow about what that change might look like, whether it’s compatible with the American philosophy of justice, and why some people have reservations about abandoning the status quo.

A lightly edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Sean Illing

The law, as you point out in the book, already forgives, but it’s very selective about when and who it forgives. Who gets forgiven now and why?

Martha Minow

One of the central reasons to write this book is that many of the inequalities reflected in the distribution of power in this country help explain who gets forgiven and who doesn’t, particularly when there’s discretion that’s given either to a judge or to some other law enforcement official, like a police officer or a prosecutor.

When there’s discretion, then the biases of the individual come into play. One of my favorite cartoons shows a judge with a big bushy mustache and a large nose looking down from the bench at someone with the exact same mustache and nose saying obviously not guilty.

There’s an understandable but dangerous tendency to identify with people like ourselves and to not identify with people who are different. Developing a jurisprudence of forgiveness is partially about developing criteria for judging when and how discretion is exercised.

Sean Illing

Can you give me an example of a type of person or institution that receives forgiveness now?

Martha Minow

Right now, for example, we have a bankruptcy code that allows a for-profit college or university to declare bankruptcy but does not allow the students who took out loans to go there to declare bankruptcy. That reflects a political judgement about who or what can be forgiven. And it’s an expression of who has the power to lobby in this country, of who has the power to influence legislation.

We should be critical of these sorts of imbalances and fight for a system that extends the same sense of charity to less-powerful individuals and institutions.

Matt Jonas/Digital First Media/Boulder Daily Camera via Getty Images

Loss Prevention Supervisor Lonnie Hernandez looks over some of the 55 letters he has received from shoplifters that have been through the Longmont Community Justice Partnership in Longmont, Colorado on August 19, 2016.

Matt Jonas/Digital First Media/Boulder Daily Camera via Getty Images

A letter Lonnie Hernandez received from a shoplifter is seen on his desk. Part of his organization’s restorative justice program includes offenders writing letters apologizing for their crimes.

Sean Illing

What are some crimes right now for which there is no mechanism of forgiveness but you think there should be?

Martha Minow

America is the most incarcerating country on the planet, and one consequence of that is the presence of fines and fees that are layered on top of people who are convicted of a crime. Many systems actually impose on the criminal defendant the cost of a probation officer or the cost of monitoring anklets with which they’re discharged, and the fines and fees accumulate.

These are often people without a lot of resources and there’s no forgiveness mechanism and therefore they can face even more incarceration for nonpayment. I think that’s an area where absolutely we should have mechanisms of forgiveness. Although there’s some efforts now to do just this, it’s not nearly enough.

Sean Illing

Who would you say gains the most from a more forgiving legal system?

Martha Minow

Not to be too simplistic, but I think we all do. In an interpersonal context, the one who forgives often gains as much if not more than the one who was forgiven. To let go of a grievance is to be freed in many ways.

More transparency and a more forgiving and pragmatic approach to crime also benefits the entire community because it constrains law enforcement and prevents the needless break-up of families, which is what incarceration does.

Sean Illing

There’s another prosecutor problem, though, which you discuss in the book and which New York Times legal reporter Emily Bazelon has written about. We have a significant number of overzealous prosecutors, people who are benefiting politically from from locking up as many people as possible. How do we address that?

Martha Minow

The emergence of progressive prosecutors is encouraging. It’s part of a broader movement to support and demand the election of people who are very clear about their intention to be less punitive and to pursue alternative models like restorative justice.

Another technique, of course, is to not have elected prosecutors at all, which is flawed for countless reasons. We can also develop ways to measure and reward other indicators of success besides how many people did you lock up. For example, we should pay more attention to how many people end up falling back into the criminal justice system after their initial contact with it.

If prosecutors are just tossing people in jail who continue to commit crimes after serving time, well, that’s obviously bad. But that’s just not part of the incentive structure right now.

Sean Illing

Do you worry that more forgiveness means prioritizing the interests of perpetrators over the needs of victims?

Martha Minow

I certainly do. And as much as I criticize mass incarceration, I do believe that we need vigorous law enforcement, and often the people most victimized by crime are the most disadvantaged. They’re poor people, people of color, people who are most likely to be targeted by violence. So while we need to talk about fairness, there are definitely dangers in taking the concerns of perpetrators too far. At the same time, we can’t let that concern get in the way of thinking more broadly about how to construct a more just, balanced, and forgiving system.

Sean Iling

Some people have raised concerns that there’s an imbalance in terms of our expectations about who should forgive and that simply calling for more forgiveness risks normalizing certain forms of oppression or violence. How do you respond to this?

Martha Minow

These are very important objections and I don’t think it’s accidental or unique to our society that people with relatively less power are either more likely to be expected to forgive than people with more power.

People of color and women in particular, at least in our society, have developed more muscles when it comes to forgiveness, even when they may be more often on the receiving end of harms. We see this now with the Me Too movement where very often someone who’s been identified as engaging in sexual assault or sexual harassment then expects their victims to forgive, and that’s often an expression simply of the power that they had in the first place.

I don’t think the problem here is forgiveness, though. Forgiveness is a resource every human being has and indeed every religion, every major moral philosophy, and every society has tried to cultivate. The real problem, as you suggested, is the unequal expectations around who should forgive and when.

Sean Illing

The idea of forgiveness seems at odds with our whole philosophy of justice in this country. Do we need a fundamental shift in how we think about justice and law?

Martha Minow

Every law student learns that there are multiple purposes of the criminal justice system. Deterrence of crime is one, incapacitation of people who are dangerous is another, but so is retribution and finally rehabilitation. Those are the four classic goals.

The United States doesn’t have a criminal justice system — we have many, many local fiefdoms of criminal justice systems and many of them have been moving away from rehabilitation for a long time and very much toward retribution and not even always thoughtfully using deterrence as a goal.

Since most of our system operates by plea bargain, much of it’s not even public. Prosecutors often work by stacking up as many charges as possible so that people will plead to something and then using that as leverage to press them into some admission of guilt and then some kind of punishment.

So how does that feed back into a deterrent system? It’s not clear. I think we’ve swung way out of balance from the goals that the system itself is supposed to have.

I think that we can learn some from other systems. I’m very encouraged when I hear that there are delegations from a city in the Midwest going to Norway or Finland to learn about how they engage in more restorative practices. There are increasing experiments in this country. The District of Columbia has decided to use restorative practices for its juvenile justice docket. I think there are a lot of people from a lot of different walks of life, different political persuasions, who are saying, “There’s something very broken here and we can change.”

Sean Illing

Let’s say we did shift to a more forgiving legal system, are there any trade-offs that concern you? Is there something our current system does well that we might lose if we made this change?

Martha Minow

I think we have to step back and recognize that we have too many people incarcerated and too many people in debt and we need a reset. That’s what I’m calling for.

But are there risks? Of course. One danger is that introducing more forgiveness into the system could further jeopardize the principle of equality under the law if it’s not applied fairly. If we don’t eliminate the imbalances we were talking about earlier, then more forgiveness could easily deepen the inequalities that already exist.

So, above all, we have to ensure that the benefits of a more forgiving system extend to everyone and not simply to the most powerful forces in the country. If we can do that, the country as a whole will be better.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/2XegO9Q

0 notes

Text

Why we need a more forgiving legal system

The Supreme Court on March 12, 2019. | Jonathan Newton/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Harvard law professor Martha Minow on the possibilities of restorative justice.

The American justice system’s approach to crime seems to be: Lock up as many people as possible. This is one of many reasons why we’re the most incarcerated country in the world.

Punishment has a role in any criminal justice process, but what if it was balanced with a desire to forgive? What if, instead of locking up as many people as possible, we prioritized letting go of grievances in order to create a better future for victims and perpetrators?

These ideas are central to a growing “restorative justice” movement in America, which seeks to bring together criminals, victims, and affected families as part of a process of dialogue and healing. Think of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission as a model for this approach to justice.

A new book by Harvard law professor Martha Minow, titled When Should Law Forgive?, explores how the restorative justice philosophy might be scaled up and applied to the broader criminal justice system. Minow was dean of Harvard Law from 2009 to 2017 and is known for her work on constitutional law and human rights, especially the rights of racial and religious minorities.

Minow’s book is very much what the title implies: a plea for a justice system that emphasizes forgiveness over resentment, resolution over punishment. It’s not a call for abolishing punishment altogether, but it is an attempt to challenge some of our most basic assumptions about law and order.

What we have now, Minow argues, is a system that forgives some and not others, that favors the powerful over the marginal. And the only way to change it, she concludes, is to rethink the incentive structure that guides our entire criminal justice process.

I spoke to Minow about what that change might look like, whether it’s compatible with the American philosophy of justice, and why some people have reservations about abandoning the status quo.

A lightly edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Sean Illing

The law, as you point out in the book, already forgives, but it’s very selective about when and who it forgives. Who gets forgiven now and why?

Martha Minow

One of the central reasons to write this book is that many of the inequalities reflected in the distribution of power in this country help explain who gets forgiven and who doesn’t, particularly when there’s discretion that’s given either to a judge or to some other law enforcement official, like a police officer or a prosecutor.

When there’s discretion, then the biases of the individual come into play. One of my favorite cartoons shows a judge with a big bushy mustache and a large nose looking down from the bench at someone with the exact same mustache and nose saying obviously not guilty.

There’s an understandable but dangerous tendency to identify with people like ourselves and to not identify with people who are different. Developing a jurisprudence of forgiveness is partially about developing criteria for judging when and how discretion is exercised.

Sean Illing

Can you give me an example of a type of person or institution that receives forgiveness now?

Martha Minow

Right now, for example, we have a bankruptcy code that allows a for-profit college or university to declare bankruptcy but does not allow the students who took out loans to go there to declare bankruptcy. That reflects a political judgement about who or what can be forgiven. And it’s an expression of who has the power to lobby in this country, of who has the power to influence legislation.

We should be critical of these sorts of imbalances and fight for a system that extends the same sense of charity to less-powerful individuals and institutions.

Matt Jonas/Digital First Media/Boulder Daily Camera via Getty Images

Loss Prevention Supervisor Lonnie Hernandez looks over some of the 55 letters he has received from shoplifters that have been through the Longmont Community Justice Partnership in Longmont, Colorado on August 19, 2016.