#railways privatisation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

What are Sir Topham Hatt’s (and the engines) opinion on how privatization was handled? When I read about it, I always think how absurd it was to keep the track nationalized, but let other companies run the goods trains, then different run the passenger trains. It is a spaghetti mess. Sodor had the right idea to yoink the old Furness mainline.

Thank you for your ask! (and I'm really sorry for the long wait). This is actually going to be really fun to potentially answer, so let's see...

Officially, the NWR regards privatisation as: "an important milestone in Britain's railway history and the beginning of cooperation between the NWR and our partner railways throughout Great Britain." It's a very prim and proper way of saying "the only thing that changed was the name of the idiot company that keeps delaying our trains." In private however, reactions were very, very different.

For a few engines, it meant very little: Thomas in particular barely cared at all. "What'll change? Not my branchline, that's for sure!" he once snapped at Duck when the Western engine tried to goad him into ranting with him about privatisation. Duncan said something very similar to a visiting diesel, only his version was far too inappropriate to be put in writing. Ever.

In stark contrast, a lot of the engines had very loud opinions about the entire thing. Duck spent most of one night trying to tell anyone who would listen that it was "disgraceful, disgusting and despicable" that the GWR hadn't been reformed after privatisation. (Henry, James and Gordon had to be physically restrained by BoCo and Bear before they tore Duck a new funnel for stealing their catchphrases). Donald and Douglas both tried to convince the Fat Controller to send them to London to 'politely make a case for a fully independent Scottish network'... multiple times. They also managed to say such inappropriate things that Oliver had to double-head all of Douglas' trains for a month to act as a censor for his language!

Gordon decided to offer the press his own solution to the privatisation issue, which went something like this: "What we need, is four companies to look after trains in different parts of the country - like we used to." "Like the Big 4?" "Indeed!" "We can't do that, such a system is considered to be a monopoly, and the government won't allow it." "Alright then, how about this: we have one railway that runs in the North and the East... and down to London perhaps. Then we can also have one railway that runs in the Midlands, and in Scotland... and also down to London perhaps, so you have your competition. Then we could have a railway that is in the West, and one in the South-" "Like the Big 4?" "No! These companies would be completely different!" "Look, Gordon, the government has made it very clear that the Big 4 will not return." "Well then FUCK JOHN MAJOR AND ALL THE TORY PARTY! [...] There would be competition anyway, with the roads, don't those blithering idiots understand?! [...] If any of them took a train for once, they'd realise just how bloody stupid the whole thing is, the bunch of------" (About twenty minutes worth of ranting has been omitted, due to various constraints...)

It was no surprise to anyone that Gordon personally campaigned for the Labour Party in 1997.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Sir Stephen Hatt and his sister Bridget were frantically pouring over the old charters of the NWR, hoping to be able to keep the new companies off Sodor - and indeed they found they could, as a 1925 Government deal originally intended to keep the NWR independent of the LMS also (entirely by accident) meant that no private, standard-gauge railway company other than the NWR could operate on the Isle of Sodor. Sir Stephen happily shoved that document in parliament's face when they tried to privatise the NWR's various assets, and then got his deal for the Furness Line from a different parliament committee before anyone could cross-reference him. By the time anyone managed to question why exactly they were selling an entirely railway line to a man who had very loudly told them to 'shove off and leave my railway alone', Sir Stephen had already taken control.

Their opinion: "Why treat a railway like its an airline? Honestly, it'll just wind up causing more problems in the end. A railway is a public good - yes, it makes us a lot of money, but we still run it for the people of Sodor, not for - no, we don't know why they divided British Rail like that, it makes no sense to us either - please stop asking more questions before we can finish our thoughts."

Also, a small rather large side note - Britain's railway privatisation is a complex and very unique affair that really showcases how exactly not to privatise a railway network. For example: for around seven years, the railway infrastructure was owned by a private company called RailTrack... which was terrible at doing its job and caused a number of major railway accidents (See Hatfield, 2000; Southall, 1997; Ladbroke Grove, 1999) and then panicked after the Hatfield crash and basically shut the network down, leading to questions over its competence and the finally its re-nationalisation because - surprise surprise - a private company trying to produce profits really shouldn't be in charge of the safety of millions of people with almost no proper accountability. Worse yet, the monopolies that the Tories wanted to avoid by breaking up the system happened anyway - see EWS, which bought up almost all the freight franchises and created a monopoly, only to be bought by Deutsche Bahn, which created an even bigger monopoly as it also owned (at the time) Arriva (they sold Arriva in 2024). To worsen the spaghetti, the system was divided into three basic sections: the infrastructure (RailTrack), Train Operating Companies (who owned the trains) and Franchises (who ran the trains and hired staff). In other words: a ticket in the UK is so expensive because you are paying for: the train crew, renting the train, renting the track, renting the platforms and producing profits for shareholders.

Oh, and suddenly freight and passenger trains owned by different companies are all competing to have priority at every. single. signalbox. in the country.

Now, I am not an expert in fixing extremely broken railway systems, but even still, I feel like I could probably do better than this mess!

Thank you for reading!

#weirdowithaquill#thomas the tank engine#railways#railway series#real life railways too#ask answered#ask me anything#british railways#british rail#privatisation of british rail#ttte thomas#ttte duncan#ttte donald#ttte douglas#ttte gordon#ttte duck

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

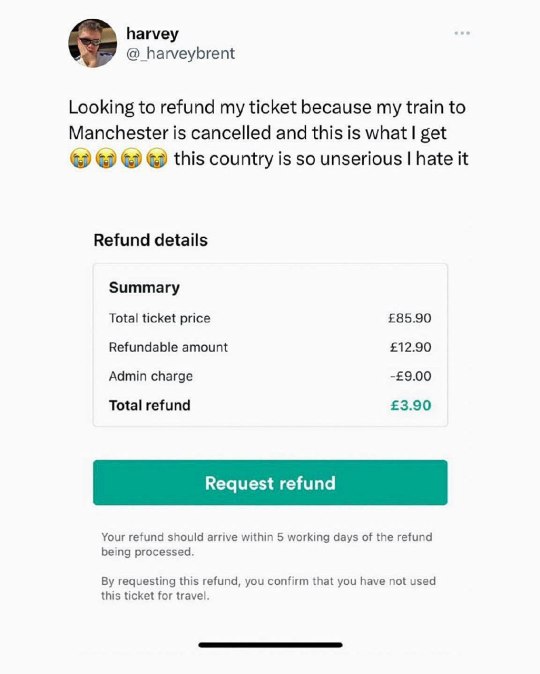

Yep that’s the privatisation of trains in the uk…

#Yep that’s the privatisation of trains in the uk…#privatisation#privatization#trains#train#railway#ukpol#ukgov#uk government#uk govt#uk#class war#manchester#london#british#britain#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals#neoliberal capitalism#anthony albanese#albanese government#eat the rich#eat the fucking rich#anti prison#antinazi

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The machinery of the British state is now just a hollowed out, privatised shell that fails to provide anything like an acceptable service and just functions as a tool to funnel as much money away to the rich as possible. Robbery.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just had to buy train tickets so I'll be spending the next 5 hours angry about privatisation.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

R.I.P

Never forget that this was a disaster both foretold and preventable.

May the guilty be damned forever.

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/3/2/greece-train-crash-2

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

NOT THE TRANS TRAINS

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Want to understand the nationalisation of British railways? This video clearly explains the history. Discover why the government took over the railways from private companies and created British Railways. Check out the full video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTrwr8Mzuig

1 note

·

View note

Text

60 Years of the Tokaido Shinkansen!

On 1 October 1964, a railway line like no other opened. Connecting Tôkyô and Ôsaka, paralleling an existing main line, the Tôkaidô New Trunk Line had minimal curves, lots of bridges, zero level crossings. Striking white and blue electric multiple units, with noses shaped like bullets some would say, started zooming between the two cities as at the unheard-of speed of 210 km/h.

This was the start of the Shinkansen, inaugurating the age of high-speed rail.

The trains, with noses actually inspired by the aircraft of the time, originally didn't have a name, they were just "Shinkansen trains", as they couldn't mingle with other types anyway due to the difference in gauge between the Shinkansen (standard gauge, 1435 mm between rails) and the rest of the network (3'6" gauge, or 1067 mm between rails). The class would officially become the "0 Series" when new trains appeared in the 1980s, first the very similar 200 Series for the second new line, the Tôhoku Shinkansen, then the jet-age 100 Series. Yes, the 200 came first, as it was decided that trains heading North-East from Tôkyô would be given even first numbers, and trains heading West would have odd first numbers (0 is even, but never mind).

Hence the next new type to appear on the Tôkaidô Shinkansen was the 300 Series (second from left), designed by the privatised JR Tôkai to overcome some shortcomings of the line. Indeed, the curves on the Tôkaidô were still too pronounced to allow speeds to be increased, while all other new lines had been built ready for 300 km/h operations. But a revolution in train design allowed speeds to be raised from 220 km/h in the 80s to 285 km/h today, with lightweight construction (on the 300), active suspension (introduced on the 700 Series, left) and slight tilting (standard on the current N700 types).

Examples of five generations of train used on the Tôkaidô Shinkansen are preserved at JR Tôkai's museum, the SCMaglev & Railway Park, in Nagoya, with the N700 prototype lead car outdoors. It's striking to see how far high-speed train technology has come in Japan in 60 years. The network itself covers the country almost end-to-end, with a nearly continuous line from Kyûshû to Hokkaidô along the Pacific coast (no through trains at Tôkyô), and four branch lines inland and to the North coast, one of which recently got extended.

東海道新幹線、お誕生日おめでおう!

#Japan#Shinkansen#Tokaido Shinkansen#0 Series#60th Anniversary#100 Series#300 Series#700 Series#JR Tokai#I'm posting this just after midnight Japanese time#oh well#late to the party#新幹線#東海道新幹線#0系#JR東海#Nagoya#SCMaglev & Railway Park#train#2023-07

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

network rail, when am I getting replaced?

A class 455 doing some sweet multi-track drifting

#like#im ok with publicisation of the railways but why is CrossCountry the last to be privatised#also hii network rail :3#*unintelligible diesel generator noises*

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

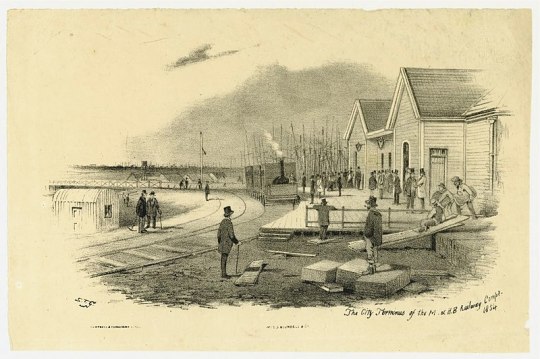

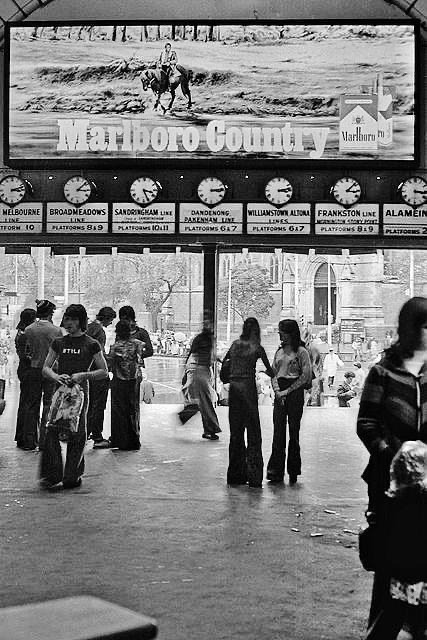

170 Years of Flinders Street Station (and railways in Victoria)

On 12th of September, 1854, Flinders Street Station, the oldest railway station in Australia was opened.

On that same day, the first ever trip on a steam engine was made departing Flinders Street to Sandridge (Port Melbourne) by the Melbourne And Hobsons Bay Railway Company.

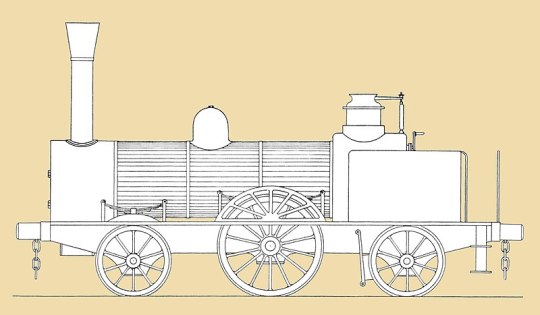

The engine itself was a local built 2-2-2 Well Tank engine that took 10 weeks to build as locomotives ordered from Robert Stephenson and Co of England were not going to arrive in time.

She broke down a lot and services did not resume until Christmas of when the English locos Unfortunately she was not preserved and it is unknown when she was withdrawn and scrapped.

The Victorian Railways were created by an act of Parliament shortly after in 1856 and started operations in 1859; absorbing the Melbourne and Hobson Bay Railway Company and other private companies that had sprung up

Flinders Street Station both preceded and outlived the VR when it was split into the State Transport Authority and the Metro Transport Authority in 1983 and privatised in the 90’s.

Flinders Street Station itself beyond its function as a train station terminus holds a vital place in Melbourne’s culture. You ask anyone in Melbourne to meet ‘under the clocks’ and they will know what you mean.

There was, and still is, a popular ‘70s style black and white photobooth there that was operated for 50 years by a gentleman called Alan Adler, who sadly passed away yesterday, RIP.

Jess Norman and Chris Sutherland (above) now run the booth.

Flinders Street Station was a popular hangout for youths, but not so much these days.

Two Sharpies at Flinders Street Station sometime in the 1970s.

Did youze all know that Flinders Street Stations has a full sized ballroom?

Yeah.

It was originally a lecture hall for the Victorian Railways Institute, a school the VR had for educating enginemen. But it blossomed into a multiuse space that included a billiards room, a gym and a boxing ring, even a running track on the roof.

The VR in the ‘60s would hold public dances here as well. What’s less known is that few of these dances were Rock ‘n’ Roll dances where Oz’s Rockers/Greasers would gather, and the first generation of Sharpies would gather outside and taunt them and it would turn into a stoush.

*tucks this tidbit away for some VR humanisation AU stories featuring Rocker diesels and Sharpie steam engines*

It’s in a bit of shithouse state at the moment, but hopefully it will be restored in the future.

Here’s to you in your 170th year, Flinders Street Station… several months late but still kind of fitting since we are celebrating 200 years of railways this year.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

More info below!

Class 483 Manufacturer: Metro-Cammell (1937-1940) Model: n/a 1938 tube stock withdrawn from the London Underground. Used on the Island Line due to low clearance on the tunnel at Ryde. Withdrawn in 2021 after an ungodly amount of years in service.

Class 325 Manufacturer: ABB (1995-1996) Model: BR 2nd Gen. EMU (Mark 3 Derived) Built for mail and parcel traffic. Withdrawn in 2024 because Royal Mail didn't feel like using trains anymore (woooo yay privatisation yayyyyy)

Class 69 Manufacturer: Progress Rail (2020-Present) [Rebuilt from Class 56] Model: n/a Due to being unable to find a manufacturer for diesel locomotives that fit Britain's loading gauge and regulation, GBRf sought to essentially stick Class 66 engines into older unused stock. They perform freight duties.

DLR B90/B92/B2K Stock Manufacturer: Bombardier (B90 1991, B92 1993-1995, B2K 2001-2002) Model: n/a Built for the Dockland Light Railway to replace the original rolling stock, which were unable to use Bank station due to their lack of emergency exits on the front of the train. Due to be withdrawn with the introduction of the B23 Stock.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

🚂 CHEMINOTS EN COLÈRE CONTRE LA PRIVATISATION DE LA SNCF !

Jeudi 21 novembre, près de 400 cheminots lyonnais se sont rassemblés à la gare de la Part-Dieu pour exprimer leur colère face à la privatisation de la SNCF et au démantèlement du fret ferroviaire.

Cette mobilisation marquait un ultimatum avant le début d’un mouvement reconductible le 11 décembre, pour défendre ce service public essentiel au pays et les milliers d’emplois menacés.

La privatisation, les licenciements massifs et l’abandon des services publics ne sont pas des réformes, mais une guerre sociale déclarée. La seule réponse : c’est la grève générale et illimitée.

🚂 RAILWAY WORKERS ANGRY AGAINST THE PRIVATIZATION OF THE SNCF!

On Thursday, November 21, nearly 400 Lyon railway workers gathered at the Part-Dieu station to express their anger at the privatization of the SNCF and the dismantling of rail freight.

This mobilization marked an ultimatum before the start of a renewable movement on December 11, to defend this essential public service for the country and the thousands of jobs under threat.

Privatization, mass layoffs and the abandonment of public services are not reforms, but a declared social war. The only answer: a general and unlimited strike.

#SNCF#privatisation#privatization#class war#human rights#november 21#railway#Part-Dieu#workers rights#workers rise up#workers solidarity#workers strike#workers#worker rights#worker solidarity#worker safety#worker strike#worker drone#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals#neoliberal capitalism#anthony albanese#albanese government#antinazi#antizionist

0 notes

Text

Imagine seeing the effect privatisation has had on Britain’s water, energy and railways and thinking yes, we need more of that.

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

I HATE PUBLIC TRANSPORT! I HATE THE PRIVATISATION OF THE RAILWAY! PRICE GOUGING BASTARDS!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

B.2.2 Does the state have subsidiary functions?

Yes, it does. While, as discussed in the last section, the state is an instrument to maintain class rule this does not mean that it is limited to just defending the social relationships in a society and the economic and political sources of those relationships. No state has ever left its activities at that bare minimum. As well as defending the rich, their property and the specific forms of property rights they favoured, the state has numerous other subsidiary functions.

What these are has varied considerably over time and space and, consequently, it would be impossible to list them all. However, why it does is more straight forward. We can generalise two main forms of subsidiary functions of the state. The first one is to boost the interests of the ruling elite either nationally or internationally beyond just defending their property. The second is to protect society against the negative effects of the capitalist market. We will discuss each in turn and, for simplicity and relevance, we will concentrate on capitalism (see also section D.1).

The first main subsidiary function of the state is when it intervenes in society to help the capitalist class in some way. This can take obvious forms of intervention, such as subsidies, tax breaks, non-bid government contracts, protective tariffs to old, inefficient, industries, giving actual monopolies to certain firms or individuals, bailouts of corporations judged by state bureaucrats as too important to let fail, and so on. However, the state intervenes far more than that and in more subtle ways. Usually it does so to solve problems that arise in the course of capitalist development and which cannot, in general, be left to the market (at least initially). These are designed to benefit the capitalist class as a whole rather than just specific individuals, companies or sectors.

These interventions have taken different forms in different times and include state funding for industry (e.g. military spending); the creation of social infrastructure too expensive for private capital to provide (railways, motorways); the funding of research that companies cannot afford to undertake; protective tariffs to protect developing industries from more efficient international competition (the key to successful industrialisation as it allows capitalists to rip-off consumers, making them rich and increasing funds available for investment); giving capitalists preferential access to land and other natural resources; providing education to the general public that ensures they have the skills and attitude required by capitalists and the state (it is no accident that a key thing learned in school is how to survive boredom, being in a hierarchy and to do what it orders); imperialist ventures to create colonies or client states (or protect citizen’s capital invested abroad) in order to create markets or get access to raw materials and cheap labour; government spending to stimulate consumer demand in the face of recession and stagnation; maintaining a “natural” level of unemployment that can be used to discipline the working class, so ensuring they produce more, for less; manipulating the interest rate in order to try and reduce the effects of the business cycle and undermine workers’ gains in the class struggle.

These actions, and others like it, ensures that a key role of the state within capitalism “is essentially to socialise risk and cost, and to privatise power and profit.” Unsurprisingly, “with all the talk about minimising the state, in the OECD countries the state continues to grow relative to GNP.” [Noam Chomsky, Rogue States, p. 189] Hence David Deleon:

“Above all, the state remains an institution for the continuance of dominant socioeconomic relations, whether through such agencies as the military, the courts, politics or the police … Contemporary states have acquired … less primitive means to reinforce their property systems [than state violence — which is always the means of last, often first, resort]. States can regulate, moderate or resolve tensions in the economy by preventing the bankruptcies of key corporations, manipulating the economy through interest rates, supporting hierarchical ideology through tax benefits for churches and schools, and other tactics. In essence, it is not a neutral institution; it is powerfully for the status quo. The capitalist state, for example, is virtually a gyroscope centred in capital, balancing the system. If one sector of the economy earns a level of profit, let us say, that harms the rest of the system — such as oil producers’ causing public resentment and increased manufacturing costs — the state may redistribute some of that profit through taxation, or offer encouragement to competitors.” [“Anarchism on the origins and functions of the state: some basic notes”, Reinventing Anarchy, pp. 71–72]

In other words, the state acts to protect the long-term interests of the capitalist class as a whole (and ensure its own survival) by protecting the system. This role can and does clash with the interests of particular capitalists or even whole sections of the ruling class (see section B.2.6). But this conflict does not change the role of the state as the property owners’ policeman. Indeed, the state can be considered as a means for settling (in a peaceful and apparently independent manner) upper-class disputes over what to do to keep the system going.

This subsidiary role, it must be stressed, is no accident, It is part and parcel capitalism. Indeed, “successful industrial societies have consistently relied on departures from market orthodoxies, while condemning their victims [at home and abroad] to market discipline.” [Noam Chomsky, World Orders, Old and New, p. 113] While such state intervention grew greatly after the Second World War, the role of the state as active promoter of the capitalist class rather than just its passive defender as implied in capitalist ideology (i.e. as defender of property) has always been a feature of the system. As Kropotkin put it:

“every State reduces the peasants and the industrial workers to a life of misery, by means of taxes, and through the monopolies it creates in favour of the landlords, the cotton lords, the railway magnates, the publicans, and the like … we need only to look round, to see how everywhere in Europe and America the States are constituting monopolies in favour of capitalists at home, and still more in conquered lands [which are part of their empires].” [Evolution and Environment, p. 97]

By “monopolies,” it should be noted, Kropotkin meant general privileges and benefits rather than giving a certain firm total control over a market. This continues to this day by such means as, for example, privatising industries but providing them with state subsidies or by (mis-labelled) “free trade” agreements which impose protectionist measures such as intellectual property rights on the world market.

All this means that capitalism has rarely relied on purely economic power to keep the capitalists in their social position of dominance (either nationally, vis-à-vis the working class, or internationally, vis-à-vis competing foreign elites). While a “free market” capitalist regime in which the state reduces its intervention to simply protecting capitalist property rights has been approximated on a few occasions, this is not the standard state of the system — direct force, i.e. state action, almost always supplements it.

This is most obviously the case during the birth of capitalist production. Then the bourgeoisie wants and uses the power of the state to “regulate” wages (i.e. to keep them down to such levels as to maximise profits and force people attend work regularly), to lengthen the working day and to keep the labourer dependent on wage labour as their own means of income (by such means as enclosing land, enforcing property rights on unoccupied land, and so forth). As capitalism is not and has never been a “natural” development in society, it is not surprising that more and more state intervention is required to keep it going (and if even this was not the case, if force was essential to creating the system in the first place, the fact that it latter can survive without further direct intervention does not make the system any less statist). As such, “regulation” and other forms of state intervention continue to be used in order to skew the market in favour of the rich and so force working people to sell their labour on the bosses terms.

This form of state intervention is designed to prevent those greater evils which might threaten the efficiency of a capitalist economy or the social and economic position of the bosses. It is designed not to provide positive benefits for those subject to the elite (although this may be a side-effect). Which brings us to the other kind of state intervention, the attempts by society, by means of the state, to protect itself against the eroding effects of the capitalist market system.

Capitalism is an inherently anti-social system. By trying to treat labour (people) and land (the environment) as commodities, it has to break down communities and weaken eco-systems. This cannot but harm those subject to it and, as a consequence, this leads to pressure on government to intervene to mitigate the most damaging effects of unrestrained capitalism. Therefore, on one side there is the historical movement of the market, a movement that has not inherent limit and that therefore threatens society’s very existence. On the other there is society’s natural propensity to defend itself, and therefore to create institutions for its protection. Combine this with a desire for justice on behalf of the oppressed along with opposition to the worse inequalities and abuses of power and wealth and we have the potential for the state to act to combat the worse excesses of the system in order to keep the system as a whole going. After all, the government “cannot want society to break up, for it would mean that it and the dominant class would be deprived of the sources of exploitation.” [Malatesta, Op. Cit., p. 25]

Needless to say, the thrust for any system of social protection usually comes from below, from the people most directly affected by the negative effects of capitalism. In the face of mass protests the state may be used to grant concessions to the working class in cases where not doing so would threaten the integrity of the system as a whole. Thus, social struggle is the dynamic for understanding many, if not all, of the subsidiary functions acquired by the state over the years (this applies to pro-capitalist functions as these are usually driven by the need to bolster the profits and power of capitalists at the expense of the working class).

State legislation to set the length of the working day is an obvious example this. In the early period of capitalist development, the economic position of the capitalists was secure and, consequently, the state happily ignored the lengthening working day, thus allowing capitalists to appropriate more surplus value from workers and increase the rate of profit without interference. Whatever protests erupted were handled by troops. Later, however, after workers began to organise on a wider and wider scale, reducing the length of the working day became a key demand around which revolutionary socialist fervour was developing. In order to defuse this threat (and socialist revolution is the worst-case scenario for the capitalist), the state passed legislation to reduce the length of the working day.

Initially, the state was functioning purely as the protector of the capitalist class, using its powers simply to defend the property of the few against the many who used it (i.e. repressing the labour movement to allow the capitalists to do as they liked). In the second period, the state was granting concessions to the working class to eliminate a threat to the integrity of the system as a whole. Needless to say, once workers’ struggle calmed down and their bargaining position reduced by the normal workings of market (see section B.4.3), the legislation restricting the working day was happily ignored and became “dead laws.”

This suggests that there is a continuing tension and conflict between the efforts to establish, maintain, and spread the “free market” and the efforts to protect people and society from the consequences of its workings. Who wins this conflict depends on the relative strength of those involved (as does the actual reforms agreed to). Ultimately, what the state concedes, it can also take back. Thus the rise and fall of the welfare state — granted to stop more revolutionary change (see section D.1.3), it did not fundamentally challenge the existence of wage labour and was useful as a means of regulating capitalism but was “reformed” (i.e. made worse, rather than better) when it conflicted with the needs of the capitalist economy and the ruling elite felt strong enough to do so.

Of course, this form of state intervention does not change the nature nor role of the state as an instrument of minority power. Indeed, that nature cannot help but shape how the state tries to implement social protection and so if the state assumes functions it does so as much in the immediate interest of the capitalist class as in the interest of society in general. Even where it takes action under pressure from the general population or to try and mend the harm done by the capitalist market, its class and hierarchical character twists the results in ways useful primarily to the capitalist class or itself. This can be seen from how labour legislation is applied, for example. Thus even the “good” functions of the state are penetrated with and dominated by the state’s hierarchical nature. As Malatesta forcefully put it:

“The basic function of government … is always that of oppressing and exploiting the masses, of defending the oppressors and the exploiters … It is true that to these basic functions … other functions have been added in the course of history … hardly ever has a government existed … which did not combine with its oppressive and plundering activities others which were useful … to social life. But this does not detract from the fact that government is by nature oppressive … and that it is in origin and by its attitude, inevitably inclined to defend and strengthen the dominant class; indeed it confirms and aggravates the position … [I]t is enough to understand how and why it carries out these functions to find the practical evidence that whatever governments do is always motivated by the desire to dominate, and is always geared to defending, extending and perpetuating its privileges and those of the class of which it is both the representative and defender.” [Op. Cit., pp. 23–4]

This does not mean that these reforms should be abolished (the alternative is often worse, as neo-liberalism shows), it simply recognises that the state is not a neutral body and cannot be expected to act as if it were. Which, ironically, indicates another aspect of social protection reforms within capitalism: they make for good PR. By appearing to care for the interests of those harmed by capitalism, the state can obscure it real nature:

“A government cannot maintain itself for long without hiding its true nature behind a pretence of general usefulness; it cannot impose respect for the lives of the privileged if it does not appear to demand respect for all human life; it cannot impose acceptance of the privileges of the few if it does not pretend to be the guardian of the rights of all.” [Malatesta, Op. Cit., p. 24]

Obviously, being an instrument of the ruling elite, the state can hardly be relied upon to control the system which that elite run. As we discuss in the next section, even in a democracy the state is run and controlled by the wealthy making it unlikely that pro-people legislation will be introduced or enforced without substantial popular pressure. That is why anarchists favour direct action and extra-parliamentary organising (see sections J.2 and J.5 for details). Ultimately, even basic civil liberties and rights are the product of direct action, of “mass movements among the people” to “wrest these rights from the ruling classes, who would never have consented to them voluntarily.” [Rocker, Anarcho-Syndicalism, p. 75]

Equally obviously, the ruling elite and its defenders hate any legislation it does not favour — while, of course, remaining silent on its own use of the state. As Benjamin Tucker pointed out about the “free market” capitalist Herbert Spencer, “amid his multitudinous illustrations … of the evils of legislation, he in every instance cites some law passed ostensibly at least to protect labour, alleviating suffering, or promote the people’s welfare… But never once does he call attention to the far more deadly and deep-seated evils growing out of the innumerable laws creating privilege and sustaining monopoly.” [The Individualist Anarchists, p. 45] Such hypocrisy is staggering, but all too common in the ranks of supporters of “free market” capitalism.

Finally, it must be stressed that none of these subsidiary functions implies that capitalism can be changed through a series of piecemeal reforms into a benevolent system that primarily serves working class interests. To the contrary, these functions grow out of, and supplement, the basic role of the state as the protector of capitalist property and the social relations they generate — i.e. the foundation of the capitalist’s ability to exploit. Therefore reforms may modify the functioning of capitalism but they can never threaten its basis.

In summary, while the level and nature of statist intervention on behalf of the employing classes may vary, it is always there. No matter what activity it conducts beyond its primary function of protecting private property, what subsidiary functions it takes on, the state always operates as an instrument of the ruling class. This applies even to those subsidiary functions which have been imposed on the state by the general public — even the most popular reform will be twisted to benefit the state or capital, if at all possible. This is not to dismiss all attempts at reform as irrelevant, it simply means recognising that we, the oppressed, need to rely on our own strength and organisations to improve our circumstances.

#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

'London Transport' the name many remember came about over many years, so here we go with a brief look. Although the history of transport in the capital is complicated, I will try to take us through the earlier developments of public transport in London. This began with official horse-drawn services in 1829, which were gradually replaced by the first motor omnibuses around 1902.

Over the years the private companies which began these services amalgamated with the London General Omnibus Company (LGOC) to form a unified London bus service.

The Underground Electric Railways Company of London, also formed in 1902, finally unified the pioneering and private underground railway companies which built the London Underground. Then in 1912 the Underground Group took over the LGOC and in 1913 it also absorbed the London tramway companies. The Underground Group then became part of the new London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB) on 1st July 1933, which also took over the Metropolitan Railway. Eventually underground trains, Green Line coaches, trolleybuses and trams then began to operate under the umbrella of London Transport, although the name 'General' continued to be seen on buses and their timetables for a while longer. So the name London Transport was eventually born! Phew, I hope that made sense.

Bringing us fairly up to date and privatisation the London Transport name continued in use until 2000 and 2003 on the Underground.

This film takes us on a little journey from the fifties to the eighties, educating us on the expansion and modernisation of transport, both buses and trains, and taking us out to the new post war towns around London and showing us how transport can change our lives.

Please check out other posts with hashtag #video on @vintage-london-images

#london history#london life#street scene#social history#transport#underground#tube#railways#london transport#1800s#1900s#video

93 notes

·

View notes