#rabadid dinasty

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fifth part of the bookscans of Al Andalus. Historical Figures, here's the previous part

expelled from their homes, since they had not surrendered peacefully, but had fought.

Charlemagne, chastened, realized that the pacts signed with the Muslim lords of northern Spain deserved no trust. He would never set foot on the Peninsula again, and subsequently dedicated itself to strengthening its borders with Hispanic Islam. For this he created the kingdom of Aquitaine, whose mission consisted of not taking our eyes off the activity of the Muslims of the places bordering Gaul.

From the disaster suffered by Charlemagne in Roncesvalles we have remains what some consider the most beautiful song of deeds of literature, La Chanson de Roland, an authentic gem of the epic poetry. Within the Spanish Ballads we find two romances that have this fact as their theme: Of the battle of Roncesvalles and the Romance of Doña Alda. The Basques also preserve a song dedicated to Roncesvalles, the Altabizaren cantua, which according to the Irishman Macnab, was written in the same century in which this event took place. But Ibn al-Arabí, who had been the originator of this whole story, was not reflected in any of these beautiful romances!

Amrus ben Yusuf: the muladí of Huesca

Muladí comes from an Arabic word that translates as "mixed race or foreigner", and was applied to those Christians who converted to Islam and continued living among the Muslims. There were many who decided to abandon Christianity, possibly for practical reasons, including stopping paying taxes, or reaching a position of social relevance among the new owners of the country and there were not a few who achieved it. There was also sincere converts, since in those centuries the roots of the Christianity was not as deep as it may seem.

This was the case of our character, Amrus ben Yusuf, whom the Christian chronicles will know him as Amorroz, born in Huesca and one of the staunchest defenders of the policies of al-Hakam I. After the death of Abd al-Rahman I, his son Hisham, a very pious emir, introducer of the Maliki doctrine in Spain, and who Driven by his religious fervor, he dedicated himself to waging war on the Northern Christians. Al-Andalus remained at peace and therefore the new emir was able to dedicate himself

to harass the Asturian monarchy. But his reign was to be very short, just seven years, and was succeeded by his second son, al-Hakam I.

But the arrival of the new emir was greeted with rebellions in all the border marches. In the most remote areas of Córdoba, the authority of the emir hardly represented anything and the governors lived in a regime of almost total independence. The insurrections against the power of the emirate were more than frequent and al-Hakam had the unfortunate luck to have to face them all. In this hard task, he will have a paladin who will always be at his side: Amrus, who will not hesitate to take radical measures when the matter is serious. This muladí would become famous on what was known as the “day of the pit.”

In the year 797, the always restless Toledo, inhabited mostly by muladíes, rose up against the Umayyad power to recognize a rebel Ubayd Allah ben Jamir, who together with a poet of Toledo, Girbib ben Abd Allah, dissatisfied with the emir, had in charge of calming down the spirits. It wasn't the first time this happen, nor would it be the last, and al-Hakam's predecessors had already had to work hard to put a stop to the rebels of Toledo.

Amrus, who at that time ruled the stronghold of Huesca, was commissioned by the emir to subdue that uprising by the means that it considers opportune. And there went Amrus willing not to disappoint his lord.

He began by eliminating the leader of the rebellion, Ubayd Allah ben Jamir, who fell into a trap prepared by him and then decided to give a lesson to the people of Toledo that they would find difficult to forget.

Amrus, according to him to avoid friction with the population, said that the best would be that, along with his troops, he would settle on a mound near the city. Towards the northwest, near the bridge over the Tagus River, rose a small fortress, possibly on the site now occupied by the Alcazar. When the enclosure was more or less finished, the emir, in agreement with Amrus, he sent an army under the command of his son, the prince Abd al-Rahman, pretending that he was going on an expedition against the Christians and that "coincidentally" had to pass near Toledo. It was a good occasion to invite the prince to visit Toledo, and Amrus, accompanied by the most important people of the city, they came out to receive him and begged him to honor them with his presence.

Abd al-Rahman seemed somewhat reluctant to accept the invitation, but In the end he agreed to it and to celebrate it the most influential mula-díes of Toledo were invited to the new fortress to celebrate a banquet in honor of the emir's son. Until then everything was more or less normal, but as the guests arrived, they became enter through a narrow passage, at the very edge of a large ditch, and the Amrus's executioners cut off their heads, while their bodies was thrown into the pit. That was the " castle of you will go and no you will come back"!

The number of those beheaded was very large. Maybe not as much as 5,000, according to some chroniclers; maybe about 700

being a very high number. What the leading class of Toledo was thus beheaded and the terrible impression produced by this event remained, for a long time, both among the Muslims and among the muladies of Toledo and from other cities.

Dozy narrates that terrible day like this: "At daybreak, a doctor that had not seen anyone leave through either of the two door, became suspicious and asked the people gathered near the entrance of the castle what had happened to the guests who had arrived early. "They must have gone out through the other door," they answered- It's strange!-the doctor then objected -; I have been for some time at the other door and I haven't seen anyone leave. After watching the steam rising above the walls, exclaimed:

Unfortunates! I swear to you that this vapor is not the smoke of a feast, but the vapor of the shed blood of your brothers, beheaded"

When things got really bad, al-Hakam knew that he could count on Amrus and so he also entrusted him with the submission of Zaragoza, the capital of the Upper March, as seditious as Toledo.

After the advent of al-Hakam, the two best generals of his father, Abd al-Karim ben Mugith and his brother, Abd al-Malik, in those moments at enmity with the new emir, they tried to evict the Aragonese chief Bahlul ben Marzuq from Zaragoza, to They settled in the city, but they did not succeed. He got a Cordoban army, and

Bahlul fled towards upper Aragon. Later this Bahlul, would take over Huesca, while other small rebellions by the Banu Qasi took place, who were descendants, it seems, of Musa ben Fortún, that Aragonese count who converted to Islam in the first moments of the conquest.

Given this panorama, it was evident that the action of Amrus who, also with full powers of the emir, came to Zaragoza in 802. Its activity was frenetic. Persecuted and killed Bahlul; took over the fiefdom of the Banu Qasi, and harshly punished to the muladíes of Huesca for their rebellious attitude. In that same year he ordered the construction of the stronghold of Tudela, between Zaragoza and Pamplona, an intermediate point that would serve as support in that always upheaval area. In this stronghold there was his son, Yusuf, commanding a strong garrison. He reinforced the walls of Huesca and put one of his cousins in charge of this city. Al-Hakam could sleep peacefully when it came to the Upper March... but even the most faithful soul is tempted in some occasions.

Installed on the banks of the Ebro, Amrus lived like a prince, enjoying your well-earned peace of mind. He had everything, or almost everything he could want, but he began to think that he too, which had garnered so much success for the emir of Cordoba, could become independent of his tutelage. It seems that he came to engage conversations with the Frankish monarch, Louis the Pious, so that supported their independence intentions and all these maneuvers reached al-Hakam's ears. The emir acted intelligent, and instead of openly declaring war on that subject that now

showed to be unfaithful, but that he had served him so many times with loyalty, he sent troops to the border, under the command of General Abd al-Karim ben Mugith, urging him not to act with the weapons until seeing Amrus's reaction to the message that the emir gave him.

This message from al-Hakam was written in the most praiseworthy and affectionate towards the muladí that you can imagine and Amrus, after reading it, was ashamed of his thoughts. He left Zaragoza and marched towards Córdoba to, once again, bear witness the emir his fidelity. Al-Hakam showered him with attention and gifts and confirmed him in the government of the Upper March. Amrus, after of this trip, he only lived two years and at his death the son of the emir, Abd al-Rahman, took charge of this March, for some time, to later pass to the son of Amrus, such was the good memory that his father had left in the emirate of Cordoba.

The "Rabadis": adventurous spirits

Most historians consider the emir al-Ha-kam I despotic and cruel. There is no doubt that his character was too impulsive and his justice extremely summary, but it is also true that his reign was affected by a series of rebellions and serious events that he had to repress as best he could. He never enjoyed the appreciation of his subjects who considered him inflexible, little inclined to piety, although it was not like that, abusive with taxes and little given to listening advice from no one. However, Dozy believes that he also had humanitarian feelings, like any other man, and that, despite of his cruel actions, his bad reputation was due, especially, to the wrath of the rebellious alfaquis, whom this emir never appreciated. And in this context, the terrible events of the suburb, rabad in Arabic, took place.

The emiral city of Córdoba had grown a lot. From Africa and from the East any Arabs and Berbers from the Maghreb continually arrived attracted by the prosperity of al-Andalus. The mosque had to be expanded larger to accommodate the number of believers who came to pray to it, and

The city was expanding beyond its walls. After the Roman bridge over the Guadalquivir was restored, there was no longer a problem for the population to settle in a suburb on the left bank of the river, which reached the vicinity from a village, Shaqunda, ancient Roman Secunda.

The inhabitants of this suburb were of very diverse origins and they carried out a multitude of diverse jobs. Besides of what could be considered the Cordoba plebs, there were many small Mullawad and Christian artisans and merchants, but due to its proximity to the main mosque and the emiral palace, many Cordobans who were employed, either in the mosque or in the palace, they settled there. Among this diverse population, also found the alfaquíes, religious leaders of the doctrine Malikí, who had reached a very prominent position and a very notable influence at court, especially with the emir Hisham, father of al-Hakam I.

This suburb will soon become a focus of discontent towards the emir's policy, promoted by the same alfaquies who with al-Hakam had neither the appreciation nor the influence that they achieved with his predecessor. On the other hand, in the city al-Hakam did not enjoy of many sympathies so it was only a matter of time before the situation exploded.

And it happened that one day a rumor spread through the city that seventy-two leading citizens had been executed and that their corpses were going to be exposed, crucified, on the right bank of the Guadalquivir. The mood be-

gan to exalt, without knowing or without asking themselves the reason for these executions. What happened was that a plot had been hatched to overthrow the emir and put in his place one of his cousins, the Umayyad Muhammad ben al-Qasim. Many notable people from the Córdoba of that time were involved in this conspiracy. Al-Hakam's cousin pretended to accept the proposal, but was immediately to tell the emir, also providing him with the list of the conspirators. Inthat same day, the emir ordered them to be arrested and executed, taking advantage of the occasion to order the murder of two of his uncles, sons of Abd al-Rahman I, who had been imprisoned since his ascension to the throne, possibly to prevent them from rebelling against him or challenging him for power. Between the crucified were figures of great social relevance, such as the son of a cadi, a palace eunuch, a market inspector and even a alfaqui. The impression that this action produced in Córdoba could not be more negative towards the emir, and the discontent, already notable, increased.

There was a plotting everywhere, at any time of the day. In the mosques, in the markets, in the streets discontent was chewed, while everyone distrusted everyone, believing they saw spies and confidants of the emir throughout the entire city.

Al-Hakam, aware of the mood, equipped himself withweapons, restored the walls, surrounded himself with a strong personal guard under the command of a Christian, Count Rabí, and prepared himself for the worst.

#book scans#al andalus. historical figures#al andalus. personajes históricos#al andalus#al andalus history#bookblr#historyblr#spanish history#sulayman ibn yaqzan ibn al-arabi#amrus ibn yusuf#rabadies#rabadi#al hakam i#al hakam i of córdoba#emirate of cordoba#umayyad emirate of córdoba#middle ages#rabadid dinasty#hisham i#hisham i of cordoba

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Related with the Rabadis chapter of the Al Andalus. Historical Figures, there's some books and historical novels about the topic. Two of them are mentioned in a a couple of articles about the Rabadis I posted and translated here on Tumblr (X) (x) if anyone wants to take a look.

The last two books are historical novels, from a saga, The Arrabal Lineage, whose second novel was published last year.

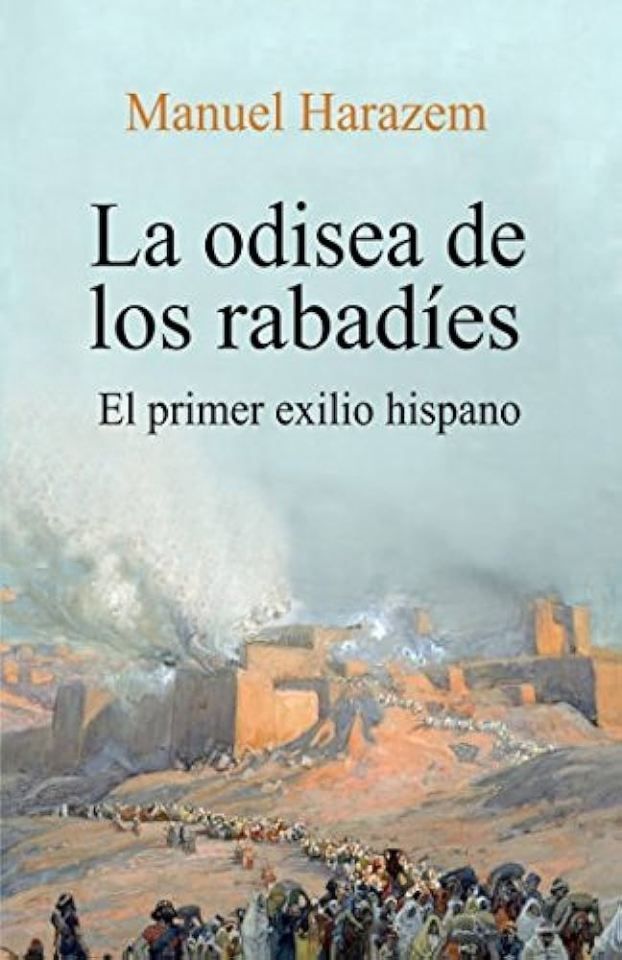

La Odisea de los Rabadíes: El primer exilio hispano (The Odyssey of the Rabadis: the first Hispanic exile) by Manuel Harazem

March 2018 marks the 1,200th anniversary of an event that occurred in Córdoba that, despite remaining unknown to the majority of its current inhabitants, had crucial importance in the city, on the peninsula and in distant places in Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. The revolt of the Saqunda suburb, its total destruction by the emir al-Hakam I and the expulsion of the surviving residents of the subsequent brutal repression has the honor, heroic on the one hand, but sad on the other, of having been the pioneer of two constants in the history of the peninsular peoples: the popular revolts inscribed in the class struggle and the exiles for political reasons. This is the first popular revolt for socioeconomic reasons and the first exile for political reasons that we have documentary evidence in the history of the Iberian Peninsula, a land that would be lavish in them from then until today. The consequence for Córdoba will be that the southern bank of the Guadalquivir would never be historically urbanized again until today, turning it into a strange case of a large city located on the bank of a river and equipped with a magnificent bridge that did not take advantage of that circumstance to develop in parallel. The consequence for distant places will be the colonization by those exiles of one of the most important cities of the Islamic world, Fez, the ephemeral, but impactful, founding of an independent republic in Alexandria and above all the creation of a prosperous Andalusian emirate on the island. of Crete that would survive for 130 years, facing the attacks of the Byzantine Empire, and throughout which its sovereigns would maintain the title of Cordoba with persistent pride. The exiles tend to be all similar, but in this case the exile of the Rabadíes, if it resembles any, is that of the Republicans after the civil war that unleashed the Spanish Fascist Revolution. The Arrabal revolt and the Republic are comparable events because both were rebellions of the popular classes allied to enlightened strata against absolute power and the permanent injustice of the emir and the regime of the national-Catholic agro-bourgeois elites. When the Power decides to apply the lesson, the emiral repression in the suburb will last three days and the civil war unleashed by the National Catholic forces will last three years. And in both cases, the terrible destruction is followed by an exile that takes two directions, one by land and the other crossing a long stretch of sea, Fez and France, Crete and America. And all cases will be fertilizers of culture of the host lands. This informative work collects the complete sequence of those distant events, which occurred in Córdoba, Toledo, Fez, Alexandria and Crete in the 9th century, in a research effort diving into different sources in different languages to clarify dark points and dismantle some errors that over the centuries, scattered and unconnected stories had accumulated in traditional historiography. And along the way, he analyzes the city's relationship with history and the remains of its Islamic past. But above all it aims to vindicate the memory of some people from Córdoba who carried out the marvelous feat of rising up against injustice and turning their misfortune into a civilizing task in the distant lands where they sought refuge to rebuild their lives.

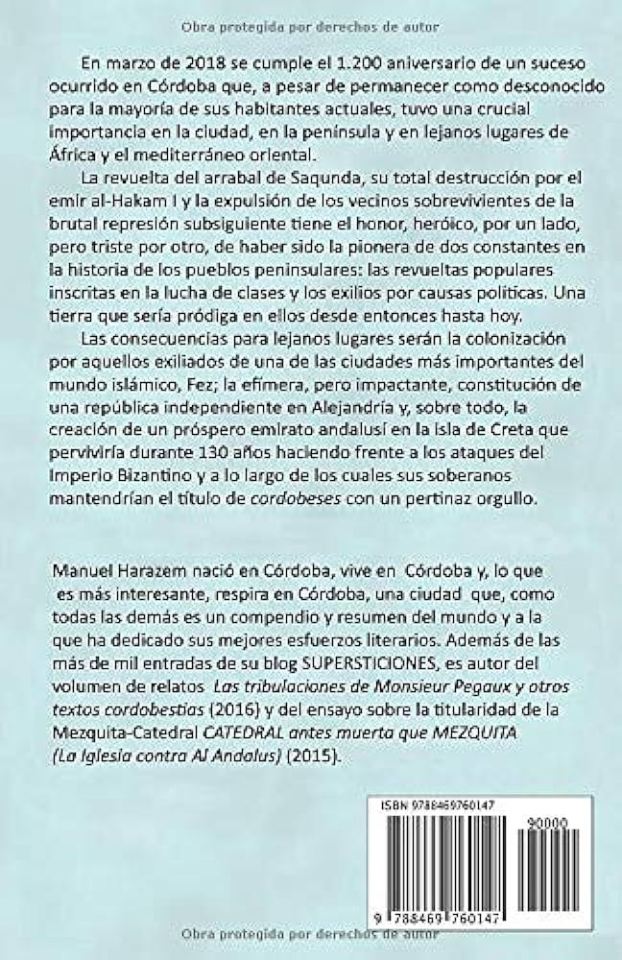

Los Andaluces Fundadores del Emirato de Creta (The Andalusian Founders of the Emirate of Crete), by Carmen Panadero

Do we Spaniards know our History? We think we know it. Sometimes important and exciting pages from our historical past appear before our eyes, which we had not heard about. There are many who are unaware, even in Spain, that thousands of families exiled from a suburb of Córdoba took the island of Crete from the Byzantine Empire, creating a dynasty of emirs there during the 9th century and part of the 10th. Very few are those who will know. that those simple people of the town, Iberians from an inland city who had not seen other waters than those of the Guadalquivir River, took over the hegemony of the eastern Mediterranean, defeating Byzantium in decisive naval battles. It all began in Córdoba, in the month of Ramadan 202 of the Hegira (March 818 AD). In this work we try to delve into the causes that caused the mutiny that gave rise to these events and we investigate the role played in it by the different social classes of the moment. Likewise, we analyze the subsequent historical events, triggered by the exile of the rebels from the Sequnda suburb and carried out by them. We will follow the outlawed Cordobans in their long and painful exodus, which, through North Africa and after a period in possession of Alexandria, concluded when they managed to take over the island of Crete. Byzantine and, later, Greek sources have dealt with to the History of the Emirate of Crete and to the people of Cordoba who founded it through manipulation and prejudice, falsifying the historical truth and even calling them pirates. It is inexcusable to finally do them justice, to rehabilitate the figure of their most important leader, Abu Hafs al-Ballutí, and that at least in Spain, his country of origin, it becomes known that the ancient town of Pedroche, his birthplace, and Córdoba, their capital, have many reasons to feel proud of this distinguished character and his lineage. This essay, with rhythm and air of chronicle, has as its main objective to banish the partial and biased vision of this chapter of our History and to make known the true nature of the State founded in Crete by the outlawed Cordobans of the Sequnda suburb. To this end, the author has had to find translators for the fundamental works that document this topic, since they had not even been translated into Spanish until now. Thanks to the Arabic chronicles and, above all, to three Greek historians (Vassilios Christides, Christos Makrypoulias and Nikolaos Panagiotakis), who for the first time faced these historical events, overcoming prejudices and initiating a rectification, we can partly reconstruct the exploits of these Hispanics, Muslims and Christians, in the eastern Mediterranean.

La Estirpe del Arrabal I: Córdoba en el recuerdo (The Arrabal Lineage I: Córdoba in memory), by Carmen Panadero

Córdoba, 9th century. Al-Hakam I, the most despotic of the Umayyad emirs, reigned. Abũ Hafs and his family are involved in the riot in a suburb of the Andalusian capital, they suffer the relentless punishment with which it was repressed, the executions of friends and neighbors, the loss of all their property, exile with 22,000 other families, the painful exodus through North Africa, but they managed to survive, and there their adventure begins. The outlaws of the suburb took Crete from Byzantium, and Abũ Hafs was sworn in as the first emir of the newborn dynasty. There they were able to recreate their second Córdoba and recover their customs. Abũ Hafs gave his life to that suffering people, guided them when they were aimless, minted their own currency, promoted flourishing trade, opened Crete to the world and settled the religious conflicts that plagued Byzantium. All of this seasoned with intrigue, betrayal, self-denial, love and heartbreak: the fight of an entire people for its survival.

La Estirpe del Arrabal I: Creta, El Precio del Olvido (The Arrabal Lineage II: Crete, The Price of Oblivion), by Carmen Panadero

10th century. The crown prince Abd al-Azĩz headed the embassy that arrived in Córdoba sent by his father, the emir of Crete Suhayb II, and when faced with the devastated suburb of Sequnda, from which a century before his ancestors were expelled by the emir al-Hakam I, felt the weight of History and meditated: — “I was never in Córdoba before, why do I feel then as if I had never left?”

But he decided to return to Crete and assume his responsibilities after swearing on those sacred ruins that, on the painful day in which he was to succeed his father, he would choose as his nickname al-Qurtubĩ, "the Cordoban", so that his people would always remember that the Forgetting their past would condemn them to lose Crete like one fateful day they lost Córdoba. And Byzantium lurked.

This novel, the 2nd part of La Estirpe del Arrabal, narrates the events of Abd al-Azĩz I al-Qurtubĩ, the last Andalusian Emir of Crete - his loves, his sorrows, his certain justice, his revenge - and in parallel offers us the touching love stories of his son Al-Numan with Bahã, and of his daughter Yannã with Karim al-Mundhir, the military hero that even Byzantium admired under the Hellenized name of “Karamountes”. And, furthermore, betrayals, intrigues, exploits, battles...

Carmen Panadero, author of novels such as El Collar de Aljófar, La Cruz y la Media Luna or El Halcón de Bobastro, gives us once again that alloy of history and fiction that constitutes the genuine historical novel.

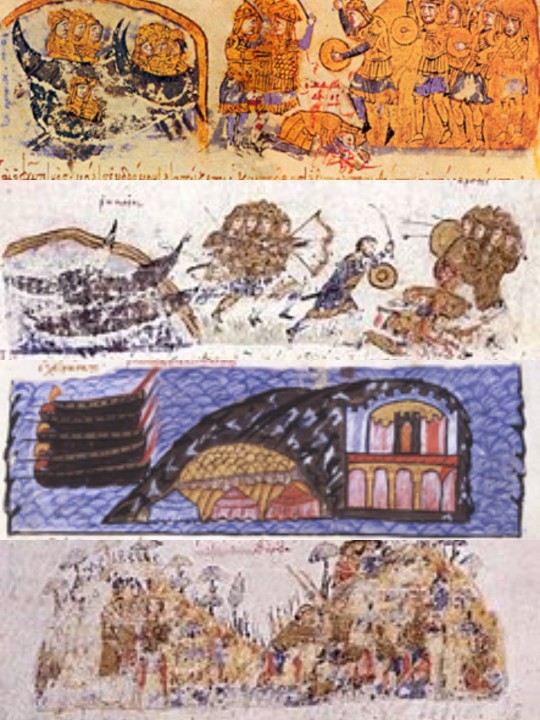

Talking about the Emirate of Crete and the Byzantine Empire, there are some depictions of the battles between them in the Synopsis of Histories, work by the Byzantine historian John Skylitzes from the 11th Century, which covers history from Byzantine Emperors between the death of Nikephoros I in 811 to the deposition of Michael VI in 1057.

Then in the Sicily during the 12th Century, a illuminated manuscript version of Synopsis of Histories was produced at the Norman court of Palermo. This manuscript is called Madrid Skylitzes, because nowadays is housed in the Spanish National Library, in the web page of the Library you can see the Madrid Skylitzes digitized.

1. Byzantine attack on Crete

2. Byzantines under Krateros defeat the Cretan Saracens

3. Byzantines under Nikephoros Phokas besiege Chandax

4. Byzantines under Ooryphas ambush and defeat the Cretan Saracens

#book scans related#al andalus#emirate of cordoba#emirate of crete#bookblr#books#al andalus history#historical novel#the rabadis#rabadid dinasty#spanish history#la odisea de los rabadíes#la odisea de los rabadíes: el primer exilio hispano#the odyssey of the rabadis: the first hispanic exile#manuel harazem#the odyssey of the rabadies#carmen panadero#los andaluces fundadores del emirato de creta#the andalusian founders of the emirate of crete#la estirpe del arrabal#the arrabal lineage#córdoba en el recuerdo#creta el precio del olvido#greek history#abd al-aziz i of crete#abd al-aziz al-qurtubi#al-balluti#synopsis of histories#john skylitzes

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

6th part of the bookscans of Al Andalus. Historical Figures, here's the previous part

The following year a very serious incident occurred in the suburb, and according to custom, al-Hakam acted summarily, executing all possible guilty suspects through the infamous crucifixion.

As if that were not enough, the mood of the population in general, an increase in the taxes that, on top of that, a Christian, the so-called Count Rabi, collected, ended up for exasperating everyone. And the spark of rebellion broke out over an apparently trivial matter, as happens on so many occasions. A soldier of the guard emir had his sword polished and it seemed to him that the swordsmith in the suburb did not attend to him with sufficient alacrity, so he killed him by piercing him with his sword in question. Al-Hakam was hunting outside Cordoba and upon returning, passing through the conflictive neighborhood, was booed. His guard arrested ten rioters and, without mercy, they were immediately crucified. The emir had barely arrived at his palace when the entire suburb was up in arms. Businesses were closed and the tents, and with sticks, stones, knives, and everything they had within their reach, artisans, merchants, and the general public headed to the doors of the Alcázar with threatening intentions and the design of demolishing them.

In those moments of anguish in the Alcázar, when his fate presented itself doubtful in the face of those angry mobs, only al-Hakam seemed to retain the calm. He asked his Christian page to fetch a jar of civet and with it he perfumed his hair and beard. The page asked him, astonished, how in those serious moments he could think of putting on perfume as if he were going to court a woman and the emir replied that he did it so that when the popu-

lace cut off his head to know that it was really the head of their prince and not that of any other. Measures were taken with all the speed that the committed moment required. The troops loyal to the emir ensured order in the city and the palace butler and his secretary gathered all the available forces to try to contain the rapidly advancing mobs that were leaving uniting more and more people. The emir's troops were beginning to falter in the face of what seemed an unstoppable force of the mutineers, until two of the generals from al-Hakam they managed to reach the first houses in the suburb. Then its inhabitants found themselves surrounded. The two exits of the neighborhood were taken by loyal to the emiral cause. The rout began... and the slaughter.

Al-Hakam gave orders that no mercy be shown to the rioters and for three the looting and massacre continued, and no one knows what it could had happened if the minister Ibn Mugith did not advise the emir to cease in that horrible carnage. The suburb was closed so that no one could leave there until al-Hakam passed sentence or thought about what to do with the rebel subjects. The solution was still terrible, as terrible as three hundred notables of the suburb would be crucified and the rest of the inhabitants who had survived would preserve their lives in exchange for immediately abandoning Córdoba. The suburb would be completely demolished, plowed and planted so that no one could build a house or a habitation there. None of al-Hakam's successors dared, until the end of the 10th century, to contravene that now distant prohibition dictated by the emir and the suburb remained, for

a long time, like a desolate and dead place in which it seemed impossible there would have been so much life.

The inhabitants of the suburb, "rabadis" as they would be known, had to abandon house, business and city in the first fortnight of April 818. Only the fuqahāʾ and their families were freed from this expulsion, much to the dismay of al-Hakam, knowing as he knew that if they had not been the direct instigators of the rebellion, they encouraged it and did nothing to calm things down. It is not well known how many people were banished from the suburb, it is believed that perhaps there were about 20,000, since it was a very populous neighborhood, although the figure may have been a bit exaggerated. And there begins the odyssey of the “rabadis”, who showed themselves to be accomplished adventurers, forced, no doubt, by the need.

Some went to take refuge in Toledo, a city always willing to welcome to all those who showed themselves against the central power. But they feared that the anger of that vengeful emir reached them, so they decided to flee further away, as far as to cross the sea. The Rabadis, with their families, left towards the Mediterranean coast, not without suffering the assault of the unscrupulous in their modest convoys in which they carried the few belongings they saved from the merciless looting to which they had already been subjected. Some went to North Africa and settled among the Berber tribes. In this region there were few cities and Prince Idris II was looking for inhabitants who could populate the city of Fez that their father had founded. It would not

take much time to increase this population with a new city, very close to the one that already existed and spread the word that everyone who came to populate both cities would be welcomed with open arms. Many Rabadis, with their families, moved there and very soon the new foundation of Idris II was known as Madinat al-Andalusiyyin, the “City of the Andalusians”. To this city they took the rabadis their knowledge of gardening and agriculture, crafts and architecture, as well as as their forms of citizen life. But this was not their greatest feat of those banished.

Part of them set out to sail the Mediterranean, dedicating themselves to privateering and piracy to survive. Although the Rabadis were not sailors, it is very possible that they they were accompanied by Valencian or Andalusian sailors, muladíes most likely, and that together they would undertake that adventure.

One day they docked in front of beautiful Alexandria, in those days subjected to fighting, that were taking place throughout Egypt, among the governors appointed by the caliph. The Rabadis became strong in the city and with the help of a faction Arab, the Lajmis, and the followers of a puritan Islam, created a kind of independent republic that they would maintain for more than ten years.

In vain the inhabitants of Alexandria tried, on more than one occasion, to get rid of these upstarts who had become masters of their city. Finally, in May 827, the governor Abd Allah ben Tahir, besieged them and after several days of siege, the Rabadides surrendered. They were allowed to go, but

they could not take any of their slaves and had to compromise that they would not dock in any port that was in Abbasid territory.

Thus they found themselves expelled from Egypt, as they had already been expelled from Córdoba, and they began the journey again, this time heading towards the island of Crete, which belonged to the Byzantine Empire. In command of that expedition that sought a place to settle, there was a man from Córdoba from Llano de los Pedroches, called Abu Hafs Umar al-Balluti. They landed on the island and occupied it in their whole. Abu Hafs al-Balluti founded a dynasty there that remained on the island for one hundred and thirty-four years, until the year 961.

They repelled incessant Byzantine attacks that wanted to recover Crete, until that the general Nikephoros Phocas managed to recapture the island for the Byzantine emperor Roman II.

Back at sea, those already distant Andalusians, for more than a century and medium, frightened the entire navigation of the central and eastern Mediterranean, also acting with great audacity in the Aegean islands.

Ziryab: the singer of Baghdad

A somewhat peculiar character from Muslim Spain was Ziryab, although he wasn't a politician, nor a religious person, nor a warrior, he was going to have a capital influence on the Andalusian society, creating fashions and implementing customs and ways of life that ended up adopting Moors and Christians, and that would remain until our days.

Ziryab was called that because he had very dark skin and he was given this nickname in reference to the black plumage of a bird, the blackbird, but its real name was Abu-l-Hasan Ali ben Nafi. He was born in Mesopotamia and was a freedman of the Abbasid caliph al-Mahdi. From a very young age he showed to be gifted, in a privileged way, for singing and was a disciple of another celebrity in the field of music, the singer of the Baghdad court, Ishaq al-Mawsilí. Very soon he became so famous that the Great Caliph Harun al-Rashid asked the teacher to bring his disciple to court to hear him sing.

There are many legends about this performance. One of the best known is the that Ziryab, before the caliph, very sure of himself, told him that he knew how to sing what other great singers knew but, who also sang, what no one knew sing. If the caliph so desired, he would put in his ears

a music and a song that no one had heard before. Harun al-Rashid was surprised and intrigued and wanted me to act for him, interpreting those unknown melodies.

It is said that Ziryab did not use the traditional lute as accompaniment, but who used an instrument of his invention. It was a kind of five-string guitar, the first, the third and the fifth were made with lion's guts; the second and fourth were made of red silk. To press them, instead of the typical pick of wood, he used the claw of an eagle.

Harun-al Rashid was fascinated by what he heard and told the singer that he returned the next day to perform, again, for him. But Ziryab didn't returned to the palace in Baghdad. What had happened for the musician to not coming back? Well, his master felt deep envy of the success of his disciple. He understood that he was going to take away his place as a favorite singer in the court and threatened to kill him. Ziryab, fearing for his life, decided to leave from Baghdad as soon as possible

The sad days of exile as a traveling musician began for him. For some time he lived in Cairo, crossed the deserts of Egypt and Libya and he settled in Qayrawan, a city that had nothing to do with the splendor of Baghdad or the refined Córdoba. But wherever he went, those who heard him singing could never forget the timbre of his voice and the harmony of his compositions. And so it was that through another musician, less jealous than his mas-

ter!, the Cordoban Jew Abu-l-Nasr Mansur, reached the ears of al-Hakam I the mastery of Ziryab and sent for him. Al-Hakam I, like all the emirs and, later, Andalusian caliphs, was a great lover of music and poetry and himself a notable poet. Ziryab embarked immediately to Algeciras. There, as soon as he disembarked, he received news that the emir had just died and became disheartened, thinking that his good luck was ending. But Abd al-Rahman II, son and successor of al-Hakam, let him know that he maintained the contract that his father had offered him and sent him gifts of such magnificence that the singer was clear that he would remain in al-Andalus forever. The emir received him with the greatest attention and not only that: he assigned him a fabulous pension for the time, 200 gold dinars a month, in addition to providing him with a house and servitude, giving him some land in the countryside of Córdoba, which was very productive, and complete his offering with two hundred sextars of barley and one hundred of wheat to maintain his house and his family. There was not in all Muslim world another poet, musician, singer or scholar who was better paid than Ziryab, and the splendid remunerations of which he was the object, extended, even further, his fame everywhere. In truth it must have been an exceptional being for the emir treated him with such kindness!

But to better understand the generosity of Abd al-Rahman II it is interesting to know something about what his life and his court were like, in which he adopted all the royal forms of the Court of the Abbasids. His father had left him the Treasury coffers completely packed, which allowed the new emir to dedicate

to acquire the most precious merchandise that arrived to Córdoba brought by Jewish, Slavic and Iraqi merchants.

Abd al-Rahman II was an unrepentant lover and admirer of women. Of all Europe and also from the East, beautiful young women will arrive, always virgins to the harem of the emir, who is said to have had forty-five male children and forty-two daughters. Some of his many concubines managed to reach just fame for her beauty, careful education and talent. Such is the case of the three young people known as the “Medinese”, not because they were natives of this city, what's more, one of them was Spanish, but all three had been educated in a perfect Arab culture. They were magnificent singers, versifiers and experts in Medinese music and entertained the leisure of their lord who appreciated them in such a way. So for them he had a special pavilion built inside the Alcázar.

A man like the emir, lover of all pleasures, both the sensual ones like intellectuals, it was not surprising that he appreciated moving art and only one of Ziryab, who arrived in al-Andalus in the year 822, with four children who, with over time, they would continue his work, and he stayed until his death in 857. In these thirty-five years the emir and he always maintained cordial relations and they appreciated and respected each other.

But Ziryab's activities were not only limited to music, but his genius manifested as a profound innovator of the Muslim society of the time. He created a conservatory... and a beauty institute, because Ziryab was a true and refined dandy.

#al andalus. historical figures#al andalus. personajes históricos#book scans#al andalus#historyblr#bookblr#al andalus history#spanish history#rabadies#rabadid dinasty#al hakam i#al hakam i of córdoba#emirate of cordoba#emirate of crete#abu hafs al-balluti#abd al rahman ii#abd al rahman ii of córdoba#zyriab#abu-l-hasan ali ibn nafi#zyriab the singer of baghdad#al-balluti

7 notes

·

View notes