#psychomotor effects

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Marijuana's Influence on Brain Health: Unraveling Complex Cognitive and Psychiatric Effects

Marijuana is a category of drug, it has many medical uses abut abuse causes many complications and leads to many unpredictable life issues.

Marijuana, particularly its psychoactive component Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), has significant effects on the brain, primarily through its interaction with the endocannabinoid system. This system includes cannabinoid receptors, mainly CB1 and CB2, distributed throughout the brain and body https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/addiction/marijuana-use-and-its-effects Mechanisms of Action CB1…

#brain impairments#cannabinoid receptors#cannabinoids#cannabis#CB1 Receptors#CB2 Receptors#cbd#drugs#health#Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)#marijuana#mental-health#opioids#psychiatric disorders#psychomotor effects#schizophrenia

0 notes

Note

hi!! could you possibly make a post about temporal lobe epilepsy/seizures? your account is the bestest ever for resources gosh i love it

Writing Notes: Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

Epilepsy - a chronic (persistent) disorder of the nervous system. The primary symptoms of this disease are periodic or recurring seizures that are triggered by sudden episodes of abnormal electrical activity in the brain.

The term ‘‘seizure’’ refers to any unusual body functions or activities that are under the control of the nervous system.

Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

Also called psychomotor epilepsy, psychomotor seizure, complex partial seizure

The term for recurring seizures beginning in the temporal lobe – the section of the brain located on the sides of the head behind the temples and cheekbones.

An epileptic seizure often associated with temporal lobe disease and characterized by complex sensory, motor, and psychic symptoms such as:

impaired consciousness with amnesia,

emotional outbursts,

automatic behavior, and

abnormal acts.

The temporal lobes are the areas of the brain that most commonly give rise to seizures.

The mesial portion (middle) of both temporal lobes is very important in epilepsy — it is frequently the source of seizures and can be prone to damage or scarring.

Because there are so many diverse functions either in or closely related to the temporal lobes, these seizures may have a dramatic effect on the patient’s quality of life.

Seizures beginning in the temporal lobes may remain there, or they may spread to other areas of the brain.

Depending on if and where the seizure spreads, the patient may experience the sensation of:

A peculiar smell (such as burning rubber)

Strong emotions (such as fear)

Abdominal/chest discomfort

Automatic, unconsciously repeated movements

Staring

Loss of awareness

Uncinate Epilepsy - A form of psychomotor epilepsy initiated by a dreamy state and by hallucinations of smell and taste, usually caused by a medial temporal lesion. Also called uncinate fit.

Furor Epilepticus - The sudden unprovoked attacks of intense anger and violence to which individuals with psychomotor epilepsy are occasionally subject.

Sources: 1 2 3 ⚜ More: Notes & References ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs

Thanks so much for your kind words! And your requests are always interesting, I learned a lot from this. Hope this helps with your writing.

#writing notes#medicine#epilepsy#seizures#writeblr#literature#writers on tumblr#writing reference#dark academia#spilled ink#writing prompt#creative writing#writing resources

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

I drew a new page!

Would anyone be interested on some nerd facts on very early onset schizophrenia/ schizophrenia in general? Bc in that case I might type up some info on it with sources and everything.

however what is important to mention for me: schizophrenia is a very debilitating disorder but it is often framed as overly violent and sinister by popular media without any regard for people affected for it. Even though we have a wrong diagnosis in this comic, I would like to point out that people affected by schizophrenia are not dangerous and scary but rather perceive their environment as dangerous and scary during psychotic episodes. To a point where some think they have to defend themselves and might react aggressively. People affected by schizophrenia are however more likely to be the victims of violence then enacting violence themselves and actively psychotic symptoms are not what happens all the time. And after these episodes, most of them are shocked, ashamed and deeply saddened by close relatives having been scared of them.

Schizophrenia is mostly treated with different types of medication that sadly have strong side effects (e.g. psychomotor symptoms like tremor or difficulty walking, dizziness, sleepiness etc). Life with schizophrenia is difficult but 1/3 of those diagnosed with it can live a relatively symptom free life while for the next third, multiple psychotic episodes are the case and for the last third it’s chronical. Early onset and very early onset cases are rare and have a worse prognosis than late onset. If you meet a person with schizophrenia that is taking their medication regularly, you might not even notice they experience schizophrenia.

Please treat everyone with kindness, especially people who perceive their world as scary and full of terrors sometimes - that is all I want to say for now.🙏❤️

#五夏#suguru geto#satosugu#jjk#夏油傑#tw: suicide mention#tw: psychosis#tw: psychiatry#tw: misdiagnosis#tw: medication

47 notes

·

View notes

Note

There are several pretty interesting and well-written analyses here that suggest that Mike suffers from depression (and hypothetically) an eating disorder. I'd be interested in your take on this (I realize that analyzing a fictional character with so little confirmed evidence is difficult, but as you said it's fun, and if there are these hypotheses, especially coming from Stranger Things where the brothers have made it clear that every detail (even clothes or colors) matters).

I'm pretty sure Mike is depressed because you don't jump off a cliff at 12 just to save your friend's baby teeth and it's clear in season 4 that he's not in the best of shape… but I would be very interested by your psychological expertise point of view ?

Could Mike’s behavior suggest any psychological challenges, such as anxiety, perfectionism, or even mild depression?

Hello there, lune. Thank you for this interesting Ask.

As you mentioned, analyzing a fictional character is very difficult. We're only able to use what we're shown in the course of the canon content. Even things said off-the-cuff by members of the cast or writing staff would be questionable in such an exercise unless it were reflected on-screen.

That said, Mike's behavior does point to some concerns worth further investigation.

You specifically mentioned people talking about Mike having depression or an eating disorder, so I will start with those.

In order to be diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder, someone needs to meet the following diagnostic criteria. Yes, I did pull my DSM-V off the shelf for this.

I will highlight any areas that I think could apply to Mike.

A. Five or more of the following symptoms have been present during the same 2-week period and represent a change in prior functioning; at least 1 must be either depressed mood or loss of interest.

Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated by subjective report or observation. In children or adolescents, can be irritable mood.

Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in activities most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated by subjective report or observation.

Significant weight loss when not actively dieting (+/- 5% body weight in a month) or significant change in appetite.

Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day.

Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day as observable by others.

Fatigue or restlessness nearly every day.

Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt nearly every day.

Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day.

Recurrent thoughts of death, recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or specific plan for committing suicide.

B. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

C. The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or other medical condition.

So, as you can see, Mike does not meet the criteria, in my opinion, for a depressive episode, let along Major Depressive Disorder. However, it cannot be denied that he shows some hallmarks of depression, so let's shoot over to differential diagnosis.

ADHD can sometimes make people think about depression, but it's usually due to the irritability that can come with lower impulse control. Mike certain can be irritable, but I don't think he shows criteria for ADHD.

But then there's Adjustment Disorder.

I won't list out the entire criteria here to avoid boring everyone, however it can present similarly, but less seriously, to depression. The key component here is that someone shows an onset of emotional and/or behavioral symptoms within 3 months of an identifiable stressor. These symptoms include significant distress that not proportional to the stressor and/or significant impairment in important areas of functioning. The symptoms also fade within 6 months of the end of the stressor. It's important to not confuse bereavement with adjustment disorder.

When thinking about Mike's mood at the beginning of season 2, it can be easy to think he might fit the bill here, but he was technically grieving El, who he thought was dead. Same with season 1 when he thought Will was dead. I think what we're just seeing there is that Mike becomes withdrawn, sullen, and irritable when grieving. That's not really abnormal, and he does get better in both cases when the one he is grieving is revealed to be alive.

I also don't see any evidence of eating disorders. I'm not sure where this one comes from. I know Mike is skinny, but that's because his actor is skinny.

Honestly, I think Mike's "issues" are overblown. He is a teenager going through teenage things for the most part, and he has a lot of supernatural stress on top of the mundane stress. Yes, he jumped off a cliff, which is highly concerning. However, when you look at the larger picture, Mike just doesn't seem to meet diagnostic criteria for any disorders, at least based on what we see. In the moment he did that, he was in a significant state of despair. Will was alive, but his only hope in finding him, El, was missing. Couple that with a bully holding a knife on one of his friends, and Mike may have just been so emotionally exhausted that he couldn't come up with any other solution. Indeed, when we see Mike when no supernatural bullshit is happening, he's more or less a typical teenager.

Mike probably should have something that can be diagnosed. Hell, all these kids should, considering what they've experienced. However, it's not depicted on screen in Mike's case. If I were personally writing Stranger Things, I probably would try to write Mike as having depression, or some symptoms, at least. It fits the course of his story and where I think it is heading in season 5. Perhaps the Duffers felt that it would be a bit much to be so heavy on the psychological repercussions on their characters. Perhaps it's because they decided to hit on these concepts a bit stronger with Will (season 2) and Max (season 4).

Regardless, Mike has a lot going on, even if there's not enough of any one thing for a diagnosis. Just because he hasn't met criteria yet, he still could in time if he doesn't get help and/or his situation doesn't improve. At the very least, his willingness to put himself in harm's way to save others is concerning. However, I think it comes more from a place of wanting to help others than hating himself. He doesn't so much devalue himself as he does simply value others more.

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

i just got diagnosed as gifted as a 20 year old!! i went to get tested because i thought i was autistic but turns out i'm gifted and have adhd

i was wondering if you would teach me a little bit about the words and general stuff about this diagnostic that i should know- most of the info i'm finding focuses on little kids, which isn't very helpful

Congratulations! It's so great you're learning new things about yourself!

Some basic info about giftedness:

--It's sometimes also called asynchronous development, because gifted people mature more quickly than their peers in some ways and more slowly in others.

--Giftedness does not have to be in traditional academic arenas.

--Gifted people are actually MORE likely to have things like ADHD or learning disabilities than the general public, not less! (People with both giftedness and another difference are sometimes called "twice exceptional" (2e).

--We got weird brains, man.

--Dabrowski described giftedness in terms of overexcitabilities - psychomotor, sensual, intellectual, imaginational, and emotional. Giftedness also tends to intersect a lot with being a Highly Sensitive Person (HSP).

--Gifted people's brains are often faster than the average person's, which can lead to some interesting results, like really fast reflexes or auditory processing disorder.

--People think that giftedness is synonymous with "achievement," but that's a misconception. While many gifted people do end up achieving greatly in their chosen area, it is not always the kind of achievement that our society values. Furthermore, pressuring gifted people to achieve can have the opposite effect.

--Gifted people are more likely than the average person to be traumatized by emotionally unsupportive environments, but are also likely than the average person to recover more quickly when they are placed in a healthy/nurturing environment.

That's all I can think of off the top of my head. Let me know if you have any more questions!

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

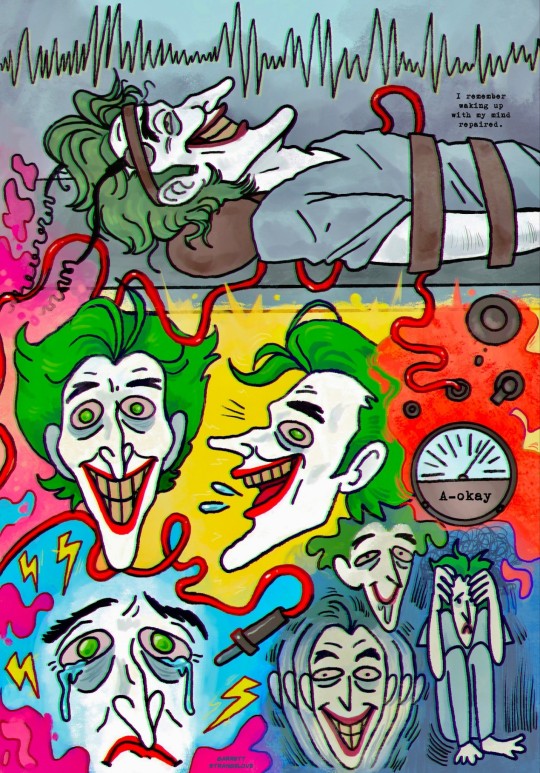

I have long been interested in what procedures are carried out on the Joker in Arkham. And comics gave me the answer about lobotomy, but I don’t remember mentions of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) (if there are such comics, recommend them in the comments).

I'm a big fan of the Joker being miserable, so I think that the procedure was carried out on him in a completely inhumane way: without anesthesia and precautions against fractures. Accordingly, all the side effects of ECT affected him 10 times more strongly. And they are:

1. Nausea and vomiting

2. Dizziness

3. Disorientation

4. Memory loss, impairment of long-term memory

5. Psychomotor agitation

6. Derealization

7. Insomnia

8. Tachycardia

9. Dental injuries

10. Jaw dislocation

Etc...

And if ECT calmed his manic tendencies for a while, it also gave a bunch of side effects, and the Joker simply experienced emotional overload, anxiety and fear of the procedure.

Batman once found out about the inhumanity of therapy and gave them all a hard time. Did the Joker feel better after this? A little.

131 notes

·

View notes

Note

what are the negative effects of common atypical antipsychotics?

> First, the adverse effects of antipsychotic medications are widely attested and very serious. They fall into at least two classes: cognitive impairments, and extrapyramidal disorders (such as akathisia, parkinsonism, and tardive dyskinesia). Both are concerning.

> Increasing evidence, both anecdotal and studied, suggests that antipsychotics frequently impair cognitive functioning. This is often described by those who have suffered from it as “zombie-like”, or as though they lacked the capacity for abstract thought [1]. There is a large empirical literature giving rigorous backing to these informal reports (see [2] for an overview and bibliography); more specifically, much of this literature suggests that antipsychotics can seriously impair procedural learning [3] [4] [9]. These empirical findings in the scientific literature, while plentiful and robust, seem not to have fully percolated yet into clinical practice.

> In addition to their potential adverse cognitive effects, antipsychotic medications are well-known to carry the risk of painful, disabling, and potentially damaging motor (“extrapyramidal”) disorders. These include akathisia (commonly described by those to experience it as “torture”), parkinsonism (a collection of symptoms similar to those involved in Parkinson’s Disease), and tardive dyskinesia (a chronic and unremitting motor disorder resulting from long-term use of antipsychotics) [5] [6] [7] [8]. While these conditions are common generally among users of antipsychotics (for those taking haloperidol—a commonly prescribed antipsychotic—extrapyramidal symptoms may present at or above fifty percent [10]), there is evidence they may be especially likely and severe, even at low doses, for autistic people [11] [12].

[1] Medical Xpress, “Antipsychotic meds prompt zombie-like state among patients” 5 Feb 2015 https://medicalxpress.com/news/2015-02-antipsychotic-meds-prompt-zombie-like-state.html

[2] Sarah Constantin, “Antipsychotics Might Cause Cognitive Impairment” 14 Jan 2018 https://www.sarah-constantin.org/blog/2018/1/14/antipsychotics-might-cause-cognitive-impairment

[3] Psychopharmacology, “Procedural learning in schizophrenia after 6 months of double-blind treatment with olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol” Sep 2003 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12827347/

[4] Neuropsychopharmacology, “Effects of risperidone on procedural learning in antipsychotic-naive first-episode schizophrenia” Jan 2009 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18536701/

[5] Missd, “The Agony of Akathisia” 6 Dec 2015 https://missd.co/256/

[6] National Commission on Correctional Health Care, “Akathisia: A Mysterious Medication-Induced Movement Disorder” 19 Jul 2021 https://www.ncchc.org/akathisia-a-mysterious-medication-induced-movement-disorder/

[7] Cleveland Clinic, “Parkinsonism” https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22815-parkinsonism#symptoms-and-causes

[8] National Library of Medicine, “Tardive Dyskenisia” 16 Aug 2022 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448207/

[9] Journal of Psychiatric Research, “Effects of haloperidol and risperidone on psychomotor performance relevant to driving ability in schizophrenic patients compared to healthy controls” Jan 2005 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15504428/

[10] MedicineNet, “Side effects of Haldol (haloperidol)” https://www.medicinenet.com/side_effects_of_haloperidol/side-effects.htm#haldol_haloperidol_side_effects_list_for_healthcare_professionals

[11] Spectrum News, “The missing generation” 9 Dec 2015 https://www.spectrumnews.org/features/deep-dive/the-missing-generation/

[12] Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders, “High rates of parkinsonism in adults with autism” 30 Aug 2015 https://jneurodevdisorders.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s11689-015-9125-6

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey, y'all! i just wanted to let you know that i'm still here and will be replying to some memes / asks in general i have in my inbox as soon as i can. one thing that i wanted to make known about anastasiy that's related to his mental health because i always try to talk about it with ALL of my oc's; and that's because it could greatly effect how a character acts, and/or reacts to things, though this doesn't absolve them of having to take responsibility for their own actions OFC.

and i was thinking about it for a while as i stated in my carrd that ana had a rather severe case of social anxiety + still has it, but he is someone who takes meds to help him with it. however, anastasiy has also had major depression for years, and it had recently developed into psychotic depression — so along with having symptoms that are typical of depression... ana also has been experiencing things like delusions and hallucinations. another important thing to note with this is that, according to the research i've done on it (as i'm not a licensed mental health professional, but i try my best to be as accurate as possible about these things)...

ana also fits the criteria for having psychomotor agitation or physical activity that is marked by restlessness. and by that, i mean he engages in things such as pacing, handwringing, and pulling at his clothes (and this is a symptom of major depressive disorder). there is more to it than just this as well, but from what i've seen of it, he has a form of it that's likely to be considered mild.

but this means that staying still is definitely difficult for him. masking is something that anastasiy feels as if he has to do on the daily especially considering he is in active psychosis (+ this might explain some of his unusual behaviors such as celebrating after completing another 'job' and why he's able to uhhh... continue on with his daily life so casually, i guess you could say, even though he's literally killing people. so yeahhh).

i hope this helps give y'all a deeper insight into his character and that you enjoyed this meta on ana, though i know this is quite a heavy topic

#NO ONE EVER TELLS YOU THAT BRAVERY FEELS LIKE FEAR: musings.#SEE HOW OUR WANTS HORRIFY US: headcanons.#ooc post.#tw: depression.#tw: mental illness.#tw: psychosis.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

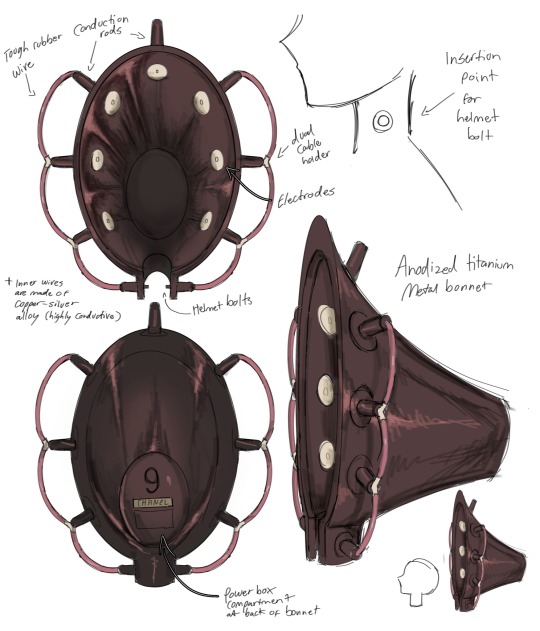

Chanel’s ECT helmet, or her “metal bonnet”

The first drawing is from 2023. The second drawing was made recently.

(Updated information and added secondary image on 5/28/24)

Despite her considerable physical strength, Chanel becomes entirely incapacitated during catatonic episodes. Her biggest vulnerability lies in bouts of catatonic stupor, likely originating from an inherited condition passed down from her mother. Catatonia is usually a comorbid disorder, so it exists along a main cognitive or neurological disorder. However, it is unknown which mental disorder Chanel may have given her upbringing. This psychomotor disorder is believed to result from disruptions or imbalances in neurotransmitter pathways, manifesting as symptoms like stupor, mutism, rigidity, waxy flexibility, posturing, and negativism. In extreme instances, it can lead to death, either due to internal complications, known as malignant catatonia, or the inability to meet essential needs because of immobility.

To ensure Chanel's effectiveness in her duties, Sibyl built Chanel a specialized “metal bonnet”, or ECT helmet, which was designed to automatically execute ECT when neurological chemical imbalances were detected ahead of time. She considered the fact that ECT has an 80% to 100% success rate in addressing catatonia and related conditions. This treatment works by inducing minor seizures to recalibrate the brain's chemistry. The helmet emits low-frequency electrical currents to regulate her brain chemistry, preventing such episodes. (ECT is typically given under anesthesia and professional oversight, but, in this fictional instance, Chanel's insensitivity to pain meant one concern was taken off the list) Given its electrical nature, it requires consistent power sources. Sibyl developed this helmet, which is powered by blood as part of their arrangement. In exchange for sustenance, Chanel aids Sibyl by procuring intelligence and bodies from her encounters with traffickers. The helmet is securely bolted into her neck and, although removable, should not be taken off for long periods because the bolts and metal sockets in her neck enable the auto-moderated procedure. These bolts serve as both anchors and receivers, processing signals from electrodes attached to the sockets that contact her neck. These synaptic transmissions occur at the junction where the bolts connect to the sockets, similar to neurons.

The electrodes detect abnormal brain activity, similar to an EEG, and send a small electrical impulse to the bolts. These bolts then relay the information to the control panel at the back of the helmet, which assesses whether conditions are optimal for the procedure. It checks parameters such as the presence of sufficient amounts of non-converted blood, insufficient amounts of non-converted blood, sufficient amounts of fuel-converted blood, or insufficient amounts of fuel-converted blood.

If conditions are safe and the helmet has enough fuel, the control unit sends a signal back to the bolts, which then reaches the metal neck guard near the voice box. This triggers the voice box to alert Chanel of its needs in Morse code. If blood or blood fuel is lacking, the helmet will notify Chanel that it needs her to collect more blood for conversion into fuel to perform the electrocution. If the blood supply is ample but fuel is insufficient, it will inform Chanel that it will begin the conversion process and to station herself somewhere secure so that any neural impulses don’t interfere with the helmet's processes. The remainder of the fuel will be used to catalyze the conversion of blood into fuel.

If conditions are optimal, the voice box gives Chanel a heads-up in Morse code about the number of minutes before a cycle starts, allowing her to find a secure location before a seizure occurs. The helmet can be powered by various fuels, including coagula blood, which can generate electricity through a bioelectrochemical process, or direct contact with an electric outlet. The coagula blood method is preferred due to the mobility it offers compared to stationary electric outlets.

Additionally, her piercings are not merely decorative but are referred to as "modulating electrodes" or "resistive electrodes." Their function is to regulate the electrical signals, preventing excessive current from reaching sensitive areas and ensuring a safe and effective ECT process. These modulating electrodes use materials with specific resistive properties to control the flow of electricity, much like variable resistors in electronic circuits, ensuring precise modulation and safety.

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

not a culture ask but looking for resources one- im a borderline and im trying to look into bipolar disorder, specifically the differences when it comes to mood and manic/depressive episodes

you see, I don't know much exactly of what bipolar disorder looks like (i dont trust pop culture's depictions too much), and what the true difference is when it comes to splitting in bpd compared to episodes in bd. I understand they're separate things, but don't fully understand how they are separate

I knew I saw a blog dedicated to those with both bd and bpd, but can't find it. I just want to know because even though I'm more inclined to just chalk everything up as "just bpd," it would be nice to understand more so it's within my consideration. the episodes I have I raise my brow at sometimes

If you don't have anything on bd vs bpd relating to the differences between splitting and episodes in bipolar disorder, then that's fine ^^ I just didn't know where to find anything so I figured I start somewhere

From what we know, bpd splits/episodes are

Shorter, usually a few days at most (with emptiness in between them

Usually shaped by conflict with ur relationships

More caused by trauma than genetics (brain chemistry can contribute though)

And bipolar episodes are

Longer, lasting from days to weeks on end

Mood between episodes are stable rather than empty

The effects can be a little more physiological from what I've read (ie; the lack of sleep, psychomotor agitation, pressured speech) or at least i think they're somewhat physiological?

Also, BPD splitting is moreso focused on one person or one group of people, while BP episodes are more general and are not focused on a person/group of people. Technically BPD splits could be considered BP episodes, but not all BP episodes are BPD splits.

We're not a professional, and i suggest taking this w 5 pounds of salt.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

A starter guide to opioid pain medication

I wrote this guide back when I was studying to take my boards as a favor for one of my mutuals--they wanted the info for a blog post, I needed to do some review. This covers basic info about how opioids work, how they compare to each other in strength, side effects, drug interactions, and more.

Opioids vs Opiates

First, what is the difference between an opioid and an opiate? The two words are often used interchangeably, but they actually mean different things. An opiate is a drug naturally derived from the opium poppy. Examples of opiates include morphine and codeine. “Opioid” refers to any substance, natural or synthetic, that binds to opioid receptors (more about these in a minute). For example, fentanyl is an opioid—it’s not derived from poppies, it’s made in a lab. All opiates are opioids, but not all opioids are opiates.

Mechanism of Action--How these drugs work

This is going to be very simplified. When an opioid reaches the bloodstream, it chemically binds to our cells via opioid receptors, which are a kind of protein located on the surface of our cells that allow cells to communicate with their external environment. This binding leads to a cascade of chemical changes that creates several effects in the body, one of which is analgesia (pain relief). There are several kinds of opioid receptors, such as the mu opioid receptor and the delta opioid receptor, and many opioids also have effects on other types of receptors, like the NMDA receptor (1).

Opioid Potency

Some opioids bind more strongly to opioid receptors than others, making them more “potent.” We say that these opioids have a higher “binding affinity” for the receptor. To an extent, how strongly an opioid binds to the opioid receptor is predictive of the extent of pain relief--and adverse effects--it can cause (2).

The potency of opioids is compared using something called morphine milligram equivalents. Basically, using morphine as the standard, opioids are assessed to see how much morphine provides the same amount of pain relief as the drug being analyzed.

Consider figure 1 below (3). You can see that morphine and hydrocodone (Vicodin, Norco) both have a conversion factor of 1. This means the two drugs are equally potent. But if you look at hydromorphone (Dilaudid), you can see it has a conversion factor of 4. That means it’s 4 times more potent than morphine. Codeine, on the other hand, has a conversion factor of 0.15, indicating it’s only 0.15 times as potent as morphine.

(A few of many) Drug interactions (4)

Opioids should be used cautiously with other sedating medications like benzodiazepines, muscle relaxers, antihistamines, and cold medicine. Opioids cause respiratory depression (they slow your breathing) so it’s important to avoid adding more sedatives on top of that.

Certain antifungals and antibiotics can affect the metabolism of opioids.

Opioids can interact with some of the drugs used to treat HIV.

Opioids can interact with psychiatric medication in a variety of ways.

Side Effects--whoops we didn’t want that to happen (5)

Some of the most common side effects of opioids are gastrointestinal in nature--constipation, nausea, vomiting. They can also cause sedation, respiratory depression, and urinary retention. People who are new to taking opioids may experience impaired psychomotor function--basically difficulties with coordination.

General information about a few opioids (6)

Codeine: Codeine is something called a pro-drug. By itself, it has no analgesic properties, but when you ingest it, your body converts it into morphine. Codeine is often found formulated with acetaminophen (Tylenol) such as in Tylenol 3 and Tylenol 4. Codeine is also a good cough suppressant and can be found in many cough syrups. Tylenol 3 and Tylenol 4 are both Schedule III substances in the USA.

Hydrocodone: Vicodin is probably the most well known drug that contains hydrocodone, but it’s mostly gone out of style; most doctors prescribe Norco instead. Both Vicodin and Norco tablets contain hydrocodone and Tylenol. The difference between them has to do with the ratio of hydrocodone to Tylenol. All drugs containing hydrocodone are schedule II substances in the USA. Common doses of this medication are 5, 7.5, and 10 mg in combination with Tylenol.

Oxycodone: Drugs containing oxycodone come in two varieties: immediate acting and extended release. Probably the most well-known drug that contains oxycodone is Percocet, which consists of immediate acting oxycodone and Tylenol. All drugs containing oxycodone are schedule II substances in the USA. Common doses for this medication are 5, 10 mg in combination with Tylenol. Given alone, not in combination with Tylenol, the max dose is 288 mg/day.

Hydromorphone: This is Dilaudid. It is a schedule II substance. It can be given as an injection or as an immediate-release tablet. For the tablet, dosing is initially 2 to 4 mg orally every 4 to 6 hours as needed, and it can be increased to adequate analgesia.

Methadone: Not used as often for pain management anymore, but used really commonly in the treatment of opioid use disorder. Methadone is a schedule II substance in the USA. Initial dosing for pain is 2.5 to 10 mg orally every 8 to 12 hours, and then titrated every 1 to 2 days based on response and tolerability.

Fentanyl: The most important thing to note about fentanyl is that its dosages are measured in micrograms, not milligrams--it’s a very potent drug. It’s used in the emergency department to sedate patients for procedures. Outpatient, it’s used as a transdermal patch, and the brand name is Duragesic. The proper use and disposal of these patches is super important; even after you wear the patch for 72 hours, there’s a TON of drug left in it, which can pose a threat to children and pets. Fentanyl is a schedule II substance in the USA. Patches come in a variety of strengths, measured in mcg/hour. 12 mcg/hr, 25 mcg/hr, 50 mcg/hr, 75 mcg/hr, and 100 mcg/hr

Morphine: This is the gold standard by which every other opioid is measured. Comes in immediate release and extended release formulations. All formulations of morphine are schedule II substances. Dosages range from 1 mg-120 mg.

This concludes my starter guide for opioid pain medication. If you have any questions, feel free to shoot me a message and I’ll do my best to answer them. Obviously, a lot of this is very simplified, but I tried to make sure it was nevertheless accurate. I hope this is helpful!

Sources

Cohen B, Ruth LJ, Preuss CV. Opioid Analgesics. [Updated 2023 Apr 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459161/

Drewes AM, Jensen RD, Nielsen LM, Droney J, Christrup LL, Arendt-Nielsen L, Riley J, Dahan A. Differences between opioids: pharmacological, experimental, clinical and economical perspectives. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013 Jan;75(1):60-78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04317.x. PMID: 22554450; PMCID: PMC3555047.

Safe Opioid Prescripting: A SMART on FHIR Approach to Clinical Decision Support - Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/CDC-Calculating-MME-Conversion-Factor-chart_fig2_319874294

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/drugs/21127-opioids

Bhatnagar M, Pruskowski J. Opioid Equivalency. [Updated 2024 Feb 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535402/

DiPiro, Joseph T., et al. DiPiro’s Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. McGraw Hill Medical, 2023.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing tips: How to describe depression with body language

WARNING: may be triggering to some; not meant to diagnose, only as a tip for writing characters suffering with mental health issues

Depression is usually different for everyone, but there are several symptoms that can be expanded upon and explored. Everyone is familiar with the concept of depression, but there’s a lot of physical responses that are visible and can also help in show-don’t-tell writing.

1. Depressed mood: pretty self-explanatory. Downcast eyes, unfocused gaze, downturned lips, sluggish movements, slow or slurred speech

2. Anhedonia (loss of interest in pleasurable activities): your character may be wandering, turning down offers, wanting to do something relating to a hobby but being unable to start or concentrate, other people may notice lack of passion, listless eyes, numbness

3. Loss of appetite/Weight loss or gain: playing with food, not having the energy to cook meals, eating the same thing over and over again, skipping meals, forgetting to eat until stomach is rumbling, eating to fill metaphorical emptiness, eating out of boredom, snacking instead of cooking meals, visible changes in weight and/or strength

4. Insomnia/Hypersomnia: struggling to fall asleep, turning and turning in bed without finding a comfortable position, waking up several times at night and struggling to fall back asleep, depression naps (usually lasting several hours), being sluggish, bags and shadows under eyes, taut, sallow skin

5. Psychomotor retardation/agitation: slow speech and movements, very little movement, delayed answers and physical responses; OR bouncing legs, wringing hands, nail biting, quick replies, nervousness

6. Fatigue: breathlessness, tiredness, weak legs and muscles

7. Diminished concentration: can be shown through character’s hobby (blank page for a writer, rereading the same paragraph over and over again, unsatisfactory work etc.), muffled sounds in conversations, lessons/lectures/work, easily avoidable mistakes slipping past character’s eyes

8. Feelings of worthlessness or guilt: recurring deprecating/horrible comments about skills/appearance/behaviour etc.,

7. Recurrent thoughts of death/ideation: not going to get into it, pretty self-explanatory.

General behaviours:

Again, this changes from person to person. As a generalised theme, people suffering from depression have a hard time with daily tasks. Brushing teeth, showering, food shopping, cleaning, tidying up, chores etc.

Also, don’t say a character feels depressed. Depression often feels like apathy, boredom, frustration, and sometimes, very intense anguish and hopelessness. Imagine the range of human emotions as a line. Depression is a line parallel to that but much lower, more muffled. It feels like a bubble that muffles feelings and the world around someone. It feels like trudging through mud to complete the simplest tasks. You may slow down the pacing to help the reader see just how long and exhausting every little action is, place a lot of inactivity inbetween actions, staring at walls etc.

A character with depression may also have very low libido, with difficulty orgasming, not wanting sex but desiring intimacy, mind wandering during sex etc.

Meds and healing

Medication can take up to 6 weeks to start to show results. Side effects in those 6 weeks range from nausea to dizziness, fatigue, migraines, and most of all, a feeling of constant apathy. Emotions are either not felt or being felt much less. That includes hopelessness as much as joy, excitement, sadness etc.

After those 5-6 weeks, character may notice the range of their emotions is widening. They feel more, more often. They may cry at a touching scene in a film, laugh or suddenly feel hopeful or happy or excited about a small thing. It’s fleeting, but human emotions actually last very little time. Don’t jump into happiness. For many depressed people, healing looks more like feeling different emotions more frequently, having slightly more energy, having inspiration for a painting, a story, a walk in nature. Healing looks very subtle, it’s a continuous process.

#i have a psych degree#doesn’t mean i know all about it#because everyone’s different#writing#writing tips#writers on tumblr#creative writing#writing body language#body language#psychology#mental health writing#writing depression#show don't tell#fanfiction writer

74 notes

·

View notes

Note

Saw the tag so wanted to send an ask! Do you want to talk/infodump about the history of antipsychotics and how that relates to ASD because that sounds fascinating.

oh my god i got asked to infodump about my most special of interests. thank you so much, most-definitively-a-human, you have made my day.

Disclaimer: I am not a psychiatrist or mental health professional, and I have no experience of either psychosis or taking psychiatric medication, so I can't promise that the facts are 100% perfect, nor that I have an understanding of what these facts mean in day-to-day life. But the least I can do is try to understand, and hope that someone else finds this interesting, or, better yet, useful.

I cannot be bothered tracking down all my sources again, so if anything in this post is interesting to you, please fact-check it, because I can't promise it's going to be right. This is medical information, so, as this is a rambling tumblr post, please take it with a grain of salt.

Skip to the end for the discussion of how autism, schizophrenia, and the antipsychotics are linked. Most of this is just me infodumping about antipsychotics, since I find them so fascinating for some reason.

Trigger warning: This post discusses medical abuse of people with severe mental illness and neurodevelopmental disorders, as well as the side-effects of psychiatric medication. There is also some discussion of self-harm in autism. As such, tread carefully.

A short(-ish) history of antipsychotics

In 1953, a new medication hit the market. Its name was chlorpromazine, and it belonged to a family of chemicals called the phenothiazines. The phenothiazines contained a lot of very, very revolutionary/historically significant meds – some highlights include methylene blue, an antimalarial that happened to be the first ever fully synthetic medication (which, due to its original purpose being 'fabric dye', had the convenient side effect of making your urine go blue); and phenbenzamine, which was not the first antihistamine ever (that honour goes to piperoxan, which is too toxic to use in humans), but was the first that was safe for use in humans. Phenbenzamine was very, very sedating, and from it, we got another compound, fenethazine. From fenethazine, we then got two derivatives: promethazine, and chlorpromazine.

Promethazine is an antihistamine, and like most old antihistamines, it's very sedating. As such, scientists tested whether promethazine worked for sedating people—and, indeed, it worked as a pretty good sedative. Its younger cousin, chlorpromazine, synthesised in 1950, also was very, very sedating. So, someone gave it to a psychiatric patient who was having a manic episode, and then, something cool happened. That is, the manic patient wasn't manic anymore.

Okay—so, chlorpromazine was sedating in a way that meant it could have some potential for previously difficult-to-treat psychiatric syndromes. (From memory, I'm fairly sure that lithium was around at the time, but frustratingly, not all mania responds to lithium. I don't know whether this patient had been trialled on lithium—all I know is that chlorpromazine worked for him.) So, it was trialled on quite a few psychiatric patients with schizophrenia, and they, too, seemed better.

Now, chlorpromazine, being related to promethazine, had a similar side-effect profile to most old antihistamines. That is, it made you eepy beyond belieepy (i'm sorry). This sedation was also accompanied, rather horrifyingly, by apathy, psychomotor retardation (thinking and moving much slower—I once saw someone online liken it to moving 'through molasses'), and emotional quieting. This triad—not moving, not wanting, and not expressing—was known as neurolepsis, and was originally thought to indicate that the drugs were working well. However, this wasn't necessarily true—in part, that's because schizophrenia spectrum disorders have negative, as well as positive, symptoms, and neurolepsis is basically a combination of actively worsened negative symptoms and physical/mental slowing. So, chlorpromazine made the psychosis better, but also induced neurolepsis, as well as several other side-effects (including but not limited to: reversible Parkinson's-like motor symptoms; orthostatic hypotension, which is when your blood pressure plummets when you stand; and anticholinergic effects, which I'm going to get back to later). Chlorpromazine was wonderful because it meant that finally, patients could deal with psychosis in a way that meant they didn't have to be institutionalised, and because it meant that much, much worse treatments (looking at you, insulin shock therapy) could finally be discarded. Chlorpromazine was awful, because, in addition to its awful side-effects, it wasn't always given consensually, and could be used to abuse and harm patients. Such is still an ongoing problem with antipsychotics—while they have revolutionised psychiatry and allowed many people to live much, much better lives, they've also indubitably been used to harm so many people. This is why it's crucial to have informed consent in psychiatry—and while I don't know how to handle this when a person is going through florid psychosis and is probably very, very scared, we ought to do much better than we are at the moment.

Due to the neurolepsis-inducing side-effect profile, chlorpromazine was deemed a neuroleptic. Most people will use the terms 'neuroleptic' (neurolepsis-inducer) and 'antipsychotic' interchangeably—however, the categories are a venn diagram, not a circle. There are some antipsychotics with only very mild neuroleptic effects (we'll get back to this), and some neuroleptics that aren't antipsychotic—for example, if you've ever the taken over-the-counter antinauseal/migraine relief drug called metoclopramide (Anagraine, Paramax, MigraMax, Metozolv, Reglan, etc), you've taken a neuroleptic. Neuroleptics are dopamine antagonists—that is, they bind to the receptor for dopamine in the brain, which means dopamine can't bind to that receptor, so you can't get the effects of dopamine at that bit. This basically explains neurolepsis as a syndrome, since dopamine is associated with reward pathways and movement; less dopamine in the reward pathways -> emotion blunting, lost motivation; less dopamine in the movement pathway -> i can't fricken' move, can't fricken' move emotionally, Parkinson's-like symptoms (Parkinson's is in part due to a dopamine deficiency in certain movement-related bits of the brain).

The antipsychotics allowed for de-institutionalisation to occur, and also gave rise to the tricyclic antidepressants, as imipramine (the first tricyclic antidepressant) is a chlorpromazine derivative. Fun! Problem was, these older psychiatric drugs tended to have fairly intolerable side-effects. So, the first-generation antipsychotics were by and large very neuroleptic—as such, we needed less neuroleptic antipsychotics for them to be tolerable. This started to happen around the 1990s and onwards, when the second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs)—olanzapine, risperidone, amisulpride, aripiprazole, quetiapine, etc.—started coming out. These SGAs bound to serotonin as well as dopamine receptors, and tended to have fewer motor side-effects than their older counterparts. They came with their own set of extra side-effects, however—some that come to mind are prolactin elevation (sexual side-effects), and appetite increases or decreases (this is not necessarily a bad thing)—but they're generally considered more tolerable, and while they're sedating, they're considered not to induce neurolepsis to the same degree. As such, they're called atypical (where typical means 'cue the neurolepsis and motor symptoms).

The problem with the typical/atypical split, however, is that most atypicals aren't quite as atypical as they're said to be. Every single atypical antipsychotic except for quetiapine and clozapine can still be linked to motor symptoms, and all of 'em can be linked to sedation of some degree. Moreover, one nasty motor side-effect of neuroleptics AND antipsychotics is this thing called tardive dyskinesia—tardive meaning late-onset, dyskinesia meaning unwanted/uncontrolled movements. So, over time, we go from Parkinson's-like symptoms (less movement) to tardive dyskinesia (more, unwanted movements), which is irreversible and sometimes progressive—the only way to deal with it is to switch to another antipsychotic and hope that it doesn't have the same effect, which is great, except if you've otherwise got a nice balance of symptom management and side-effects, that's a horrible curveball. The atypicals are said to cause tardive dyskinesia at much lower rates... except people still get TD on the atypicals. Moreover, most folks who are still taking typical antipsychotics have probably been on them longer than those on the atypicals, since people don't tend to try chlorpromazine first when quetiapine or olanzapine is more likely to do a better job of attenuating psychosis while inducing fewer adverse effects. As such, part of the difference in TD rates may be due to time, since TD develops in the long term. So, most atypicals aren't as atypical as is said.

Moreover, to split more hairs, just as antipsychotics and neuroleptics are a Venn diagram, SGAs and atypicals are also a Venn diagram, rather than a perfect overlap, due to the existence of one pesky compound called clozapine. Clozapine is pesky on several levels. Clozapine is reserved for those who've tried at least two other antipsychotics and found that they didn't fit, and this is because of its side-effects. Clozapine has a small chance of a potentially life-threatening side-effect called agranulocytosis—technically, almost all antipsychotics can cause agranulocytosis, but clozapine is the most likely to do it. If you get regular blood testing, which you will, if you take clozapine, you'll probably be fine. Otherwise, clozapine is the most atypical antipsychotic we have side-effects wise (of course, YMMV for individuals, since the human body doesn't behave according to textbooks), though it still has MANY side-effects, and it's also more likely than the others to be very effective for attenuating psychosis. (I say 'likely' because everyone's brain chemistry is different, so saying 'this drug is better than this drug' just isn't true, because different compounds work differently for different people. Some people will benefit nicely from haloperidol or perphenazine, others from ariprazole, and others will benefit most from taking mood stabilisers, instead of antipsychotics.) Clozapine is also a somewhat old antipsychotic, having been first put onto the market in 1972. But it tends to get lumped in with the SGAs simply because it's so atypical, which leads me back to the point: most atypicals aren't 100% atypical, and drug categorisation in psychiatry is confusing.

One other side-effect that antipsychotics tend to have is that they're usually very anticholinergic. Anticholinergic drugs reduce levels of a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine, which is very important for memory, movement, and so, so much more. However, the reason I mention memory is that most antipsychotics are contraindicated (recommended against) in those with dementia-related psychosis, primarily since depleting memory chemicals is the last thing you wanna do in someone with a major neurocognitive disorder. This is also why we need to be careful prescribing anticholinergics in those over 65. For the record: most severe mental illnesses tend to have some degree of neurodegenerative effect, which is why medication is so, so important, as it prevents that illness-related neurodegeneration: as such, taking an antipsychotic will prevent schizophrenia/bipolar/major depression-related cognitive decline and worsened illness, but may also have some subtle cognitive effects that probably balance out with those of the illness. It's something to monitor over time, but not something to be scared of.

I've harped on a lot about SIDE EFFECTS SIDE EFFECTS SIDE EFFECTS, so this is a reminder—if the name of a certain medication has been brought up here as associated with a side-effect, that doesn't mean the medication is necessarily bad. Antipsychotics have done a lot of good for many people, and so long as they are prescribed consensually, they will continue to be invaluable.

Also: not everyone who takes an antipsychotic has psychosis, and not every with psychosis takes antipsychotics. Medications don't necessarily indicate what illness someone has—they just help with symptoms, and antipsychotics can help with a heckuva lotta symptoms when used well.

Okay, great. How does this relate to autism, aside from that being proof that you, the author, meet criterion B3 for ASD?

We're almost there.

Several early theories of autism conceptualised it as a pervasive, childhood-onset form of schizophrenia ('childhood schizophrenia' and 'autism' have historically been used synonymously at times). Notably, several of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum disorders can be considered similar to the executive and social symptoms of autism—autism has its own positive set of symptoms, and schizophrenia its own positive symptoms, but there's an overlap between negative symptoms of the two. Autism was originally the name Eugene Bleuler gave to the way schizophrenic patients tended to withdraw into a fantasy world of their own—that is, withdrawing into an inaccessible inner world, rather than reality. While schizophrenic autism isn't nearly as relevant a clinical concept anymore, it's kinda funny how the two diagnoses diverged from that point.

It's also worth noting that schizophrenia spectrum disorders are probably neurodevelopmental, and both schizophrenia-spec disorders and autism feature enlarged ventricles in the brain. But correlation is not causation—this commonality may not mean anything. In schizospec disorders, ventricle enlargement tends to link to greater untreated duration of illness (as a visible sign of neurodegeneration), while in autism, I think it's just there. Not sure on that one, though. Not all people with ASD or schizospec disorders necessarily have enlarged ventricles, either—it's just a thing that seems worth noting.

Further, the predominant theory of how schizophrenia spectrum disorders work is that there is dopamine dysregulation—that is, some bits of the brain are getting too much, causing positive symptoms, and others are not getting enough, causing negative symptoms. Either that, or dopamine metabolism isn't working properly. We largely figured out that dopamine is probably involved in schizospec disorders by working backwards from the mechanism of action of the antipsychotics: that is, neuroleptics suppress dopamine, and dopamine suppression makes psychosis less bad—therefore, dopamine is involved in psychosis. But it's likely more complex than that, in part because not all people with schizospec disorders will respond to antidopaminergic drugs, and in part because SGAs are generally more likely to be effective than first-gen antipsychotics, and SGAs target more than just dopamine. One other theory posits that NMDA, which is a subtype of the neurotransmitter called glutamate, may also be involved. I'm not going to try to explain it here, since I don't know enough about the NMDA theory to be able to coherently string together a sentence about it. But, keep reading.

We don't entirely understand the mechanism behind autism. It probably involves synaptic pruning to some extent. It may also involve having an overactive brain, in part due to lack of pruning meaning that there is no brain highway so much as a network of ratruns that get clogged up very easily, and in part because GABA, the main inhibitory neurotransmitter we have, isn't doing something right. I think it's interesting that NMDA, a form of glutamate, might have links to psychosis, and that autism also probably involves something weird with glutamate, but I also don't know enough to say whether this is just a weird coincidence or if it's actually relevant. Nevertheless, even if it is a coincidence, I do find it funny to note these commonalities considering the historical links between the diagnoses.

It's also notable that autistic people experience psychosis at higher rates than allistic folks—I'm pretty sure schizospec disorder rates are also elevated among autistic folks—and I'm semi-sure autism is also more common in those with schizospec disorders than in those without.

Okay, now to where the meds come in.

Autism can cause varying levels of disability, ranging from those who need relatively little support to those who need full-time care. Often, higher support needs (HSN) autistics tend to have more dramatic self-injurious behaviours, and may struggle more with controlling aggression, with eloping, and other behaviours that are harmful to both themselves and others.

And I'm less-than-comfortable with how modern psychiatry has chosen to deal with this.

The only drug that's approved for treating these behaviours in ASD is risperidone, a second-gen antipsychotic. Some people will find that risperidone works really well for their psychosis—it's an effective drug! —but when it's used in ASD, it's not there to treat psychosis, usually, but to treat aggression, self-injury, and such.

Thing is, the use of risperidone for this purpose is basically an attempt to sedate the autistic child into not doing these things. I'm a low support needs (LSN) autistic who's never taken psychiatric medication, so it's not really my place to judge this as a tactic. I understand that things that some of us initially flinch at, such as putting HSN autistic children on leashes, is the right thing to do if the child is likely to elope, and I understand that if a child is going to hurt themself badly, they need help. But on the other hand, I have reservations since antipsychotics have been used unethically through history, and continue to be used unethically in certain situations. In some cases, antipsychotics may be helpful for autistic children, and I don't know enough to comment, but it's also profoundly uncomfortable to contemplate the fact that certain medications that are infamous for having horrible side-effects are being used on people who may not be able to provide informed consent. It's an ethical conundrum, since if it is the best way to prevent harm, then it's important that we don't flinch on instinct, but I also really, really hope that the HSN autistic people's needs and comfort are being taken into consideration in these circumstances, since both historically and today, HSN autistic people have been treated as subhuman in so, so many circumstances.

#infodump concluded. yikes.#hope the medical bit was as fascinating to some of y'all as it is to me#and that the information is as accurate as possible#i think i've kinda fixated on the worst bits about antipsychotics here. so i just wanna say:#if you've read this and you're on/considering taking an antipsychotic but this post has scared you#please don't worry. this is a raw text post. i promise you you're gonna be okay.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

if you have GI problems and mental health and/or neuromotor conditions make sure you are always asking what drugs they're giving you for nausea in the ER. Informed consent is a patient right and they should never be giving you drugs without telling you what they are for.

Reglan/metoclopramide is a prokinetic drug that can cause tardive dyskinesia and is black box warned for it- yet ER providers will throw it at patients without informed consent. This is still a rare side effect but people who have had TD before, or people with neuromotor disorders like Parkinsons should never be given this drug.

Compazine and droperidol are both antipsychotics that act as secondary antiemetics (anti-nausea) but they commonly cause akathisia, which is extreme psychomotor restlessness. It is absolutely awful- like overwhelming IV benadryl drowsiness with restless limbs from hell. You cannot stop moving but all you want to do is sleep.

These are drugs that are commonly overprescribed in the ER that can have severe side effects. I ended up putting all three of these on my med reaction list.

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

(about the dream bbq post) aren’t daturas like… the worst hallucinogen known to man? Known to give people horrifying trips with effects that linger for months/years? I wonder if that’s significant. I saw someone else point out the fork frog guy looks like a mad cow disease prion, + the spirals in the ballerina scene and the paper streamers also resemble prions. Both these things feel similarly related to losing one’s mind.

Ayo, you’re onto something!!!

This is an ask I recieved relating to my first ENA: Dream BBQ analysis I posted! Be sure to check that out if you haven’t already! I definitely plan to write more up ;p

Let’s look into what Mabel (I shall call this user such based on the first part of their username) brought up~!

Make Me Delirious

Daturas are a hallucinogen, more specifically a deliriant. Here are summaries about deliriants and delirium I found from Wikipedia

Already, we can see some fascinating points being brought up.

Deliriants inhibit the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which is a key part of the autonomic nervous system (aka, how our body and brain react to our surroundings). It’s an internal transmitter in the sympathetic nervous system (which is responsible for the fight-or-flight response), and the primary neurotransmitter/final product of the parasympathetic nervous system (which helps you calm down and bring your body back to normal). It’s primary function is activating muscles… so shutting that down is pretty dangerous (especially in high doses).

Deliriants are known for causing… delirium (what a shocker lol). Delirium causes psychomotor changes (hyperactivity/hypoactivity/mixed), emotional and perceptual disturbances (such as hallucinations and delusions), and disrupt sleep-wake cycles.

Most plant deliriants are part of the Solanaceae/Nightshade family, which include plants such ad belladonna/deadly nightshade, and brugsmania/angel’s trumpets. Arguably, the flowers in the trailer also look like brugsmania… but whether they’re brugsmania or datura, they’re both deliriant flowers, so all of this still applies.

These plants have historically been used by indigenous cultures in the Americas (likely in extremely small doses) for assistance in traditions/rituals involving altered states. Such rituals involve communicating with ancestors, divination, and rites of passage, and are always used under supervision of a Shaman.

Prion for Info

First and foremost, what the heck is a prion?

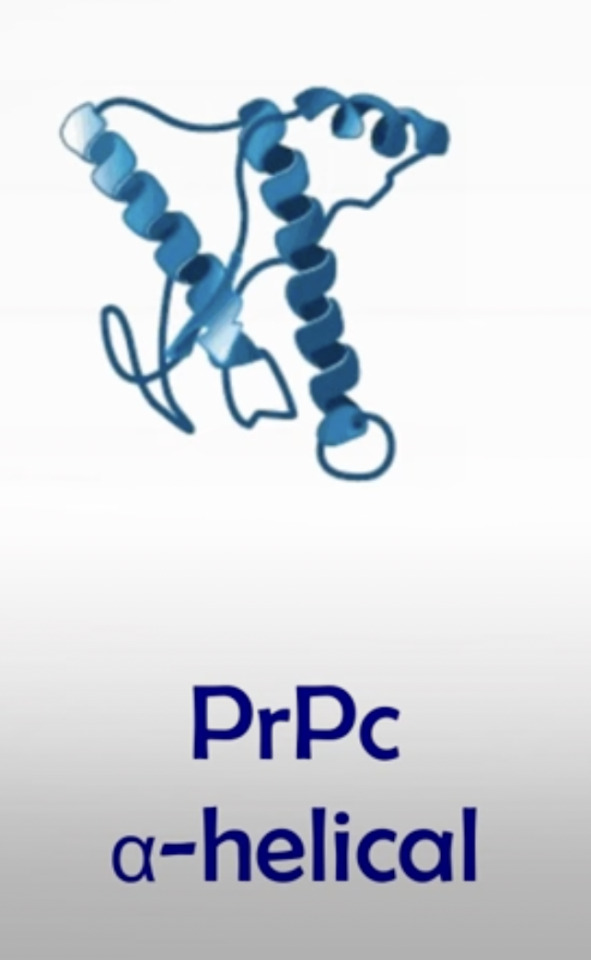

In case you haven’t taken biology yet, or forgotten those lessons from high school, the brain has a lot of normal cell proteins called prion proteins. They're an important part of our brain function... though we're still figuring out their specific purpose. Normal prion proteins look like this (pictures are from this video):

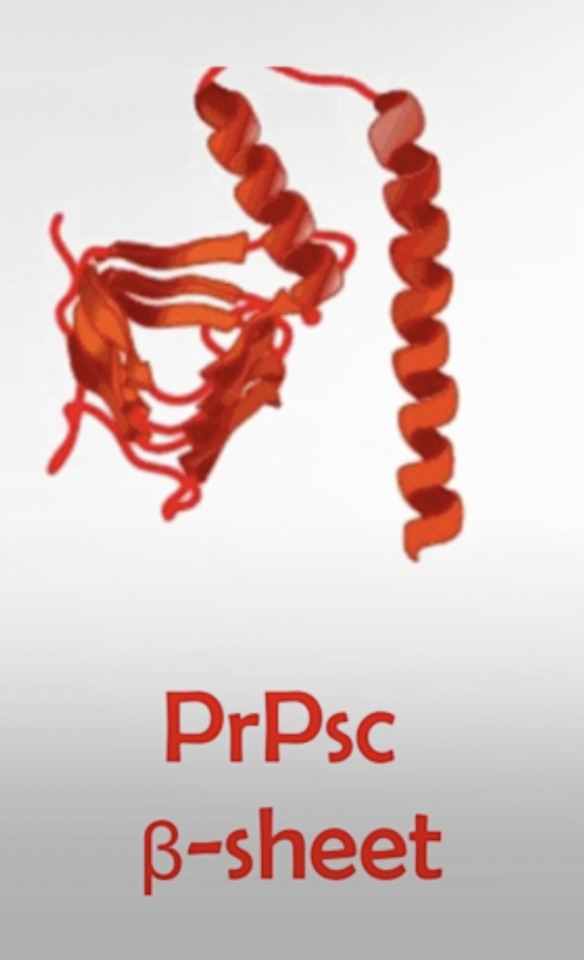

However, there are also misfolded, abnormal prions that look like this:

These are usually referred to simply as "prions" (we specify the normal, healthy ones as prion proteins), and they're able to spread their abnormal/misfolded structure onto the normal variants of the prion protein. This chain reaction is a major causative of neurodegenerative disorders, primarily via spongificatioxn of the brain (destroying the brain's gray matter). This can lead to severe symptoms such as rapid dementia, ataxia (loss of limb control), and insomnia. Once the disease starts, it's incredibly rapid and always fatal.

One of these neurodegenerative disorders that is especially prominent is Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy, also known as BSE or Mad Cow disease. As the names suggest, this disease primarily harms cattle... but humans are able to become infected by it.

How? By consuming contaminated beef.

What do you usually eat at a barbecue?

"Where is my mind" by the Pixies at full blast

In all seriousness, all of these connections to literally losing your mind and dying from madness are all very concerning. BBQ!ENA is going to go through so much more (as if the two other forms of her didn't allude to that already), and I'm very worried about her.

#ENA#ena joel g#ENA: Dream BBQ#Dream BBQ Spoilers#I'm definitely planning to do another post about the new voice reveals as well#stay tuned for that!!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Discovery of the first antipsychotic, Chlorpromazine, AKA Thorazine

In 1933, the French pharmaceutical company Laboratoires Rhône-Poulenc began to search for new anti-histamines. In 1947, it synthesized promethazine, a phenothiazine derivative, which was found to have more pronounced sedative and antihistaminic effects than earlier drugs.[50]: 77 A year later, the French surgeon Pierre Huguenard used promethazine together with pethidine as part of a cocktail to induce relaxation and indifference in surgical patients. Another surgeon, Henri Laborit, believed the compound stabilized the central nervous system by causing "artificial hibernation", and described this state as "sedation without narcosis". He suggested to Rhône-Poulenc that they develop a compound with better stabilizing properties.[51] In December 1950, the chemist Paul Charpentier produced a series of compounds that included RP4560 or chlorpromazine.[6]

Chlorpromazine was distributed for testing to physicians between April and August 1951. Laborit trialled the medicine on at the Val-de-Grâce military hospital in Paris, using it as an anaesthetic booster in intravenous doses of 50 to 100 mg on surgery patients and confirming it as the best drug to date in calming and reducing shock, with patients reporting improved well being afterwards. He also noted its hypothermic effect and suggested it may induce artificial hibernation. Laborit thought this would allow the body to better tolerate major surgery by reducing shock, a novel idea at the time. Known colloquially as "Laborit's drug", chlorpromazine was released onto the market in 1953 by Rhône-Poulenc and given the trade name Largactil, derived from large "broad" and acti* "activity".[6]

Following on, Laborit considered whether chlorpromazine may have a role in managing patients with severe burns, Raynaud's phenomenon, or psychiatric disorders. At the Villejuif Mental Hospital in November 1951, he and Montassut administered an intravenous dose to psychiatrist Cornelia Quarti who was acting as a volunteer. Quarti noted the indifference, but fainted upon getting up to go to the toilet, and so further testing was discontinued (orthostatic hypotension is a known side effect of chlorpromazine). Despite this, Laborit continued to push for testing in psychiatric patients during early 1952. Psychiatrists were reluctant initially, but on 19 January 1952, it was administered (alongside pethidine, pentothal and ECT) to Jacques Lh. a 24-year-old manic patient, who responded dramatically, and was discharged after three weeks having received 855 mg of the drug in total.[6]

Pierre Deniker had heard about Laborit's work from his brother-in-law, who was a surgeon, and ordered chlorpromazine for a clinical trial at the Sainte-Anne Hospital Center in Paris where he was Men's Service Chief.[6] Together with the Director of the hospital, Jean Delay, they published their first clinical trial in 1952, in which they treated 38 psychotic patients with daily injections of chlorpromazine without the use of other sedating agents.[52] The response was dramatic; treatment with chlorpromazine went beyond simple sedation with patients showing improvements in thinking and emotional behaviour.[53] They also found that doses higher than those used by Laborit were required, giving patients 75–100 mg daily.[6]

Deniker then visited America, where the publication of their work alerted the American psychiatric community that the new treatment might represent a real breakthrough. Heinz Lehmann of the Verdun Protestant Hospital in Montreal trialled it in 70 patients and also noted its striking effects, with patients' symptoms resolving after many years of unrelenting psychosis.[54] By 1954, chlorpromazine was being used in the United States to treat schizophrenia, mania, psychomotor excitement, and other psychotic disorders.[14][55][56] Rhône-Poulenc licensed chlorpromazine to Smith Kline & French (today's GlaxoSmithKline) in 1953. In 1955 it was approved in the United States for the treatment of emesis (vomiting). The effect of this drug in emptying psychiatric hospitals has been compared to that of penicillin and infectious diseases.[52] But the popularity of the drug fell from the late 1960s as newer drugs came on the scene. From chlorpromazine a number of other similar antipsychotics were developed. It also led to the discovery of antidepressants.[57]

5 notes

·

View notes