#proto-celtic language

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

the language nerd in me is fucking screaming and crying about the fact that Cassandra Pentaghast has what i believe may be the most accurate impression of the extinct gothic germanic accent we have, and the fact that they didn't even try to give anyone else from Nevarra the same accent is fucking criminal

yes i know it is an entirely made up accent that miranda developed herself, she unintentionally hit the nail on the fucking head with the accent of a dead language that would even be lore accurate with the placement of Nevarra relative to orlais and the other neighboring countries

also im sorry using Gothic as the language inspiration for nevarran??? is that not like too fucking perfect??

like yeh i get it accent training people for a fake accent is ridiculously hard

i do not care

give me gothic nevarrans in the truest sense of the word

i might post the notes find the notes here i have on the actual linguistic comparisons if anyone cares because i studied her pronunciation to compare to historical texts when i made the connection

#ive been studying proto-indo-european languages and myhtology for years#and dragon age pulls from sooooo many of the descendents ymthologies for its lore#like celtic#hindu#germanic#i think i even spotted so ancient persian influence#but id have confirm#but like it wouldve been so fitting in everyway for them to commit to the gothic accent#but they were fucking cowards#dragon age#dragon age the veilguard#nevarra#cassandra pentaghast#dragon age inquisition

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Hallstatt culture was the predominant Western and Central European archaeological culture of the Late Bronze Age (Hallstatt A, Hallstatt B) from the 12th to 8th centuries BC and Early Iron Age Europe (Hallstatt C, Hallstatt D) from the 8th to 6th centuries BC, developing out of the Urnfield culture of the 12th century BC (Late Bronze Age) and followed in much of its area by the La Tène culture. It is commonly associated with Proto-Celtic speaking populations.

Vierpassfibel

Hallstattzeit, Bronze

#history#archaeology#jewellery#languages#bronze age#iron age#celts#hallstatt culture#urnfield culture#la tène culture#fibula#bronze#proto-celtic language

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gaulish Latin

Car, to change, piece - English borrowed these words from French, which in turn inherited them from Latin. But they weren't native Latin words. Latin got them from Gaulish, an extinct Celtic language that was spoken in Gaul, roughly modern-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of the Netherlands, Switzerland and Northern Italy. Gaulish was a great-aunt of Welsh, Irish and Breton. Today's graphic tells you about six common Romance words of Gaulish origin, and their modern Celtic cognates.

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#english#latin#french#lingblr#catalan#spanish#portuguese#gaulish#welsh#breton#proto-celtic#irish

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finnish words by unusual language of origin

*note: this does not list all the languages that the word was borrowed from, only the oldest known origin of it

*also: if you've never seen a word on this list, please don't doxx me. These are all real words. I don't spread misinformation. Why do I still need to put this in my posts

Job: Ammatti (from proto-celtic *ambaxtos) Fun Fact: this is the same root that forms the english word “Ambassador”!

Wagon: Kärry (from proto-celtic *karros) Fun Fact: This is the root that forms the English word “Car”!

Poem: Runo (from proto-celtic *rūnā) Fun Fact: This is the root that forms the English word “Rune”!

Hikikomori: Hikky (from Japanese hikikomori 引き籠もり)

Clam: Simpukka (from Mandarin zhēnzhū 珍珠)

Goods: Tavara (from proto-turkic *tabar) Fun Fact: words descended from this root can be found as far as China and Siberia!

Dungeon, jail: Tyrmä (from proto-turkic *türmä) Fun Fact: This toot extends to Azerbaijan and even Yiddish!

Rauma (city name) (from proto germanic *straumaz meaning stream)

Cherry: Kirsikka (from ancient creek kerasós κερασός which might also have older forms) Fun Fact: this word is widespread, even appearing in Arabic.

God: Jumala (possibly from proto-indo-iranian) Fun Fact: This word could be related to Sanskrit dyumna द्युम्न if it is from proto-indo-iranian

#finnish#langblr#langblog#language#study blog#suomen kieli#finnish language#finnish langblr#word roots#proto-celtic#proto-turkic#germanic#celtic#indo-iranian

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

#ancestor vibes#ancient europe#language of our ancestors#liminal vibes#celtic pagan#spirituality#proto indo european

2 notes

·

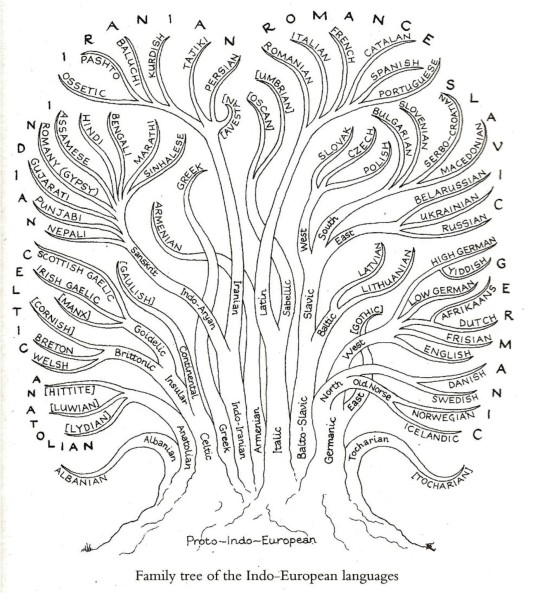

View notes

Text

#language#languages#family tree#family tree of languages#proto indo european#where language comes from#know your roots#anatolian#celtic#romance#germanic#slavic#indian#iranian#did you know#how cool is that#language is fun#language is beautiful#spoken word#written words#evolution of language#something cool#linguistics#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#where we came from#i just think they're neat

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

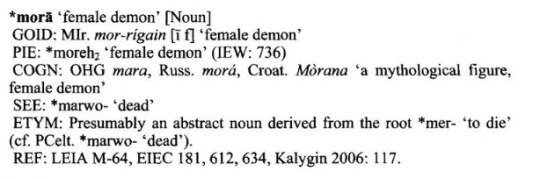

Morá

Have a gander at this from a Proto-Celtic Etymological Dictionary:

Read 'demon' with a fair amount of side-eye here, we're dealing with a translation and reconstruction from a post Christianisation period. When you see 'demon' think more 'supernatural being'.

A quick guide to the abbreviations:

GOID - Goidelic, Celtic language group including Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx.

PIE - Proto-Indo-European, ancestral language of many modern and ancient European Languages.

COGN - Think of it as comparative examples from languages outside of Proto-Celtic or its descendents.

Of the comparative examples:

OHG - Old High German

Russ - Russian

Croat - Croatian (Standard)

ETYM - Etymology

REF - Reference to source Dictionary texts.

Source: Matasović Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tiny sketches from the comic!! It's all coming along and the five tiny chapters will be (luckly) ready soon! :DDD

#languages i guess#character design#ocs#original character#lig romanian#lig italian#lig old norse#lig finnish#lig icelandic#I'm in love with her design btw#lig ukrainian#lig latvian#lig russian#lig proto-celtic#lig manx#lig cornish#my art#comic making

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Are there similarities in eastern Irish Gaelic and western Welsh? When I was at school there was some talk about language osmosis between Northern Ireland and the Scottish west isles/hebrides because of geography and trading, and I wondered if there was similar across-the-sea blending for you guys?

I’m not asking about Scots Gaelic and Welsh, I’m pretty sure they’re different language families.

Also, Gaelic was never spoken Scotland wide as Welsh was but it’s being pushed, and I know some east coast, lowland, and orkadian folk who are annoyed at the government for trying to push Gaelic signage on them when it was never spoken, and Doric, old Norse, old Scots, etc is ignored, and I’m curious as to your thoughts

So Irish and Welsh descended from different branches of the Celtic family tree (Goidelic and Brythonic, respectively) and that does mean there's broadly very little vocabulary overlap; but, I must say I found Irish to be the easiest language I ever tried to learn, and that's because they have almost identical grammar. To the point you could directly translate a sentence of Welsh to a sentence of Irish, word for word, complete with mutations, and be right about 95% of the time.

However, there is the odd example of vocab similarities as well. Occasionally it stems from a very old shared word (e.g. Proto-Celtic "glastos" becoming "glas", meaning a natural green, in both languages), sometimes it's because they got it from the same place (e.g. Welsh "Saeson" and Irish "Sasanach" from the English "Saxons"), but sometimes it's from the early Medieval period when Irish settlers came to Wales and founded the Kingdom of Brycheiniog (e.g. the word "madyn" for "fox", which derives from the Irish "madra", meaning "dog".)

Those latter settlers, by the way, also brought Ogham inscriptions with them. The greatest number of surviving Ogham inscriptions in the world is in Ireland, but the second biggest is actually Wales, not Scotland. One of those fun quirks.

Regarding your last question... so, I think this is one of those topics where I don't get a vote. The situation in Scotland simply is not like the situation in Wales, so there's a risk of me imposing my own cultural values on this in a way that is unhelpful and unwelcome. But also, Old Welsh is what was spoken in southern Scotland in the Kingdom of Strathclyde (hence Glasgow is a Welsh name, and you periodically see a bunch of Abers up there), so you know, I'm all in support of them having bilingual English and Welsh signage... (insert trollface here)

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

acta, non verba - i. a badge of honour

series masterlist | main masterlist | chapter 2 pairing: conqueror!marcus acacius x ofc!reader. synopsis: scotland, 83 AD after the battle of mons graupius. the romans have come up to the boundaries of their empire with a relentless desire to conquer the savages that inhabit the highlands. they won't rest until the Caledonian tribes are subjugated. Marcus Acacius is in charge of your clansmen's fate, but if such fate is similar to your family's, you know you need to do something about it. as the only living daughter of the tribe chief, your people look to you for leadership. power plays, treason, deception, rebellion, war, love, heartbreak, betrayal. and two souls, destined to despise each other, trying to navigate it all. a/n: well, here it is! the first chapter of my new series, set in what is now scotland, during the romans' conquest of the british isles in the 1st century. hope you guys like it! as always, all interactions welcome. thank you so much for reading! <3 warnings: 18+, mdni. death, aftermath of a battle, burial of family members. reader is an original character - female, has a name (callie) and a physical description, family history, etc. i'll try to keep the references to a minimum though. age gap (callie is 26, marcus is 48). mention of infidelity and becoming a widow. marcus’ and reader’s pov. i have taken some historical licenses for ease of writing (use of "clan" as synonym for "tribe", references to irish/celtic gods, the caledonian people speak modern scottish gaelic instead of a (proto-)brittonic language). w/c: ~4.2k. dividers by @saradika-graphics i'll be tagging some people at the end of the chapter who interacted with this post. dw, i won't tag you in the next chapters unless you ask me to! also, if you want to be removed from this post, please send me a dm.

A light breeze whistled through the nearby standing stones. The dying sun provided no heat, and the ethereal landscape was cold with hues of blue and grey. Despite the shimmering wildlife that came with the first hints of spring, the meadow was uncannily silent.

The crows cackling in the distance broke such tranquil peace and woke you from your slumber.

Slowly you blinked, something wet and warm covering your eyelids. You felt it slide down your skin, pooling in the dip of your collarbone. Your limbs felt so heavy, you couldn’t lift a hand to rub your eyes clean. In fact, you were so tired that even taking a deep breath hurt.

Your orbs fluttered shut, shattered and defeated.

Dhuosnos, God of the Dead, was calling you to His side. His presence was soothing, so inviting, the most melodic sounds guiding you to Him. With the eyes of your dying imagination, He extended a welcoming hand towards you, a soft smile on His mythical features.

“Come with me, sweet child of the tribes.” A guttural voice escaped His lips, so dark and sombre it enveloped you.

You nodded, gaze down, submitted to Him.

“You can’t just take her, Dhuosnos. Callie is yet to avenge them — her purpose must be fulfilled first before she can greet you as an equal.” A second voice, feminine, otherworldly and reassuring, interrupted your exchange.

Morrígan, Goddess of War, placed Her hand on Dhuosnos’ forearm as to stop Him from reaching you. A stone of relief, but also of disappointment, sat low in your stomach when He took a step back, head bowed towards Her.

Steadily you undid your curtsy, your green eyes locking on Hers. They were black as the night sky, Her pupils and irises indistinguishable from one another. You looked into the abyss of Her sight and felt a deep-rooted longing, one you never experienced before.

“You are not done yet, mo leanabh (my child). Your people await your return.” Morrígan palmed your trembling hand, escorting you back to the earthly plane.

“But…”, you turned around to look at Her, ask for Her advice.

But She had already vanished, a sweet scent of lavander left behind.

You gasped awake, your eyes so widened, the cloudy, sunset sky above felt like it was crashing down on you. You were laying down on a pool of mud. A deep, raspy grunt escaped your lungs as you tried to move your arms. When you couldn’t, you looked down, confused.

Aengus’ lifeless body was resting on top of yours. Your father’s henchman had made the ultimate sacrifice by hiding you underneath him, away from the prying eyes of the Romans. The dense liquid caressing the skin on your face was none other than his blood. A trickle of thick red dripped from the gnarly wound in his neck on to your cheek. His eyes were staring at you emptily, his soul had already left this world when you regained consciousness.

Your father, Murdoch of Inbhir Nis, the Caledonian Overlord, had come to the aid of the Taexalian Overlord, whose territory was succumbing to the legions of Gnaeus Julius Agricola, a Roman governor with a high desire to impress his Emperor, Titus Flavius Domitianus.

Your father had gathered as many fighers as the Caledonian lands could give him. Both men and women were called to arms when the tribes were threatened. Being the daughter of the Chieftain would not spare you. You would not have chosen differently anyway, had you been given the opportunity. Fighting for land, clan and honour was your duty as much as your brothers’ and sister’s.

The journey from Inbhir Nis (Inverness) to Cala na Creige (Stonehaven) had been unforgiving, with illness and evil lying in wait. But you all had been warmly welcomed by the Taexali tribe and were fed copiously, the uisge-beatha (whisky) being served like water.

Your combined armies, shy of fifteen thousand folk, had been ambushed at Raedykes during a repositioning exercise by the Roman troops led by Agricola’s most trusted man.

General Marcus Acacius.

His mere name made you sick, anger crawling under your skin.

Fighting off your own opponents, you had seen the Roman General charge against your father like a beast, wielding a gladius over his head. The metallic impact of their swords rang loud across the landscape. The men looked into each other’s souls, an exchange of words shared between them. You were too far to listen, too far to fully see what was really happening as warriors from both sides danced through the grass.

Then you foresaw it before it happened: the heavy Roman sword fell on your father, who was struck to his knees with the General’s blade lodged in his belly.

You tried to get to him, screaming “Athair (father)!” at the top of your lungs. His eyes locked on yours before he fell sideways. You lunged forward but didn’t get to him, Aengus stopping you in your tracks.

“No, Callie, it’s too late now”, he had sorrowfully whispered in your ear before throwing you off to one side to fend off an attacker.

And then blackness swallowed you, an enemy hit you in the head so hard you lost consciousness.

That was how you came to be where you were — with your back flat on the silt and Aengus’ body blanketing yours. The grey sky above you sensed your pain, and, at Taranis’ command, it parted in the middle. The God of Thunder released a downpour to clean the blood, soot and woad’s blue dye off your face and hair.

You cried your sadness away, rainy tears sliding off the corners of your eyes — your anger, your loss, your torment, you purged it all, sobbing until you were devoid of all emotion. Taking a deep breath, which caused a needling pain on your ribs, you pushed Aengus to one side to free yourself from his weight.

The thudding sound he made almost brought more tears to your eyes.

“Sorry, uncail (uncle)”, you muttered, hovering your fingertips over his eyelids to shut them for him. Now he could finally rest.

You stood up, your knees trembling like a newborn calf. A searing pain stabbed your skull, dried blood and dirt gathering on the wound on your scalp. With a straight back, you dared to look around you. The bodies of your own men and women were scattered around the hills of Raedykes. So many lives lost, you heard all your ancestors screaming from above, their cries falling upon you in the way of rain. The green, long grass was reddened with blood, but the weeping sky had started to wash away the atrocities committed by the Romans.

Then you saw him. Your athair.

“No, no, please, no...”, you whispered as your sight became blurry again, dragging your feet towards the fallen body of your dad.

Your soul tried to tear itself apart, become its own entity. You had to summon the last drop of the royal blood that ran through your veins to keep yourself in one piece. You knelt before him, craddling his bloody hand between yours. Unconciously your body rocked back and forth until you hugged him, laying flat on top of him.

Time stood still, like a thread on the expert hands of a wool weaver. It could have been minutes, hours or days, your pain too great to bear, to comprehend.

And then you felt a hand lightly tap your shoulder.

You startled, your mind and body jumping back into survival mode, gripping your sgian-dubh (small knife) close to your chest.

“It’s okay, mo phiuthar (my sister). It’s me, Torcall”, a raspy, masculine voice forced you to focus on the man in front of you.

He was your father’s most important tacksman and also husband to your older sister Mairead — your sweet Maisie, as you always called her. She was the eldest of the four siblings while you were the youngest. Always so witty and quick with a joke, Maisie kept up the spirits even when the circumstances were dire — in fact, before your paths had parted during the battle, she jested about your H-shaped shield being larger than you.

When you turned around, Torcall flattened his hands on your shoulders, slightly shaking you so you would come back to reality.

His blue eyes pierced through you, the situation becoming clearer in your mind. Thousands of your tribesmen were dead. Your father too.

“Maisie?”, you asked in a hush. Your heart clenched when your brother-in-law shook his head no. You were afraid to speak, but you did nonetheless. “Aodh and Somhairle?”

Torcall stared at you, his silence speaking loudly. “They are all dead.”

The air evacuated your lungs, feeling as if a spear had run through you. Learning about the death of Maisie and your twin brothers broke something within you, something fundamental and primal. They were your everything, your most trusted confidants. Despite being of different ages, you all were so tight-knit it was difficult to find one of you alone.

A heart-shattering wail escaped your lips as you bent over yourself, your chest snug against your knees.

Morrígan had unashamedly claimed most of your family that day, except for your beautiful mother. Now Her words made sense: you were yet to avenge them, to fulfil your purpose. She had spared you for a reason, not so you could pity yourself, knees deep in the mud.

To avenge them, you had to kill the hand who showered this tragedy upon you.

General Marcus Acacius.

A raven’s strident, gurgling croak forced you to look up to the skies — a subtle reminder that Morrígan was watching closely. The massive bird was circling above your heads, like a vulture waiting to feast on a carcass. With resolution, you wiped away your tears, your sobs now silent, and nodded at Torcall.

“I understand. How many…?”, your voice faltered before you could finish your question.

“A couple of thousands. We have found cover in the Dunnottar Woods while we regroup and�� bury our dead.” Torcall replied, his eyes averted with the last sentence.

You had lost a sister, but he had lost a wife, the mother to his now half-orphaned children. “I’m sorry”, you muttered, your lips pouting once more.

“She died fighting, the death of a warrior.” His proud voice did not waver. “And your father?”

Your heart wept at his mention but managed to control the anxious fluttering.

“The General killed him.” Your teeth gritted with hatred.

“Mo bana-phrionnsa (my princess)”, one of your father’s retinue members bowed his head to you once you walked into the circle they had formed in a meadow between the trees.

A few dozen men were scattered around the area, fires lighting the dark night while shades of red and orange flickered, creating fiery, dancing shades. You held a torch and carefully waved it in front of you, looking at the faces who watched you back eagerly.

You saw in your men what was brewing inside you: despair, defeat, sorrow. All your souls grieving in unison — all of you had lost someone that day.

At six and twenty, you did not expect to be in this position. You were the youngest daughter of the Overlord — you were never meant to lead your people. The task ahead of you felt titanic, unachievable.

But you had no other option. General Marcus Acacius had forced your hand.

He came, he saw, he conquered.

And now you had to deal with the gut-wrenching outcome of his departure.

“We’ll go back home to Inbhir Nis. But before that, we must give burial to our people.” You had to make a herculean effort to infuse your tone with steadiness.

Torcall first, and then the rest, bowed their heads to you.

“As you command, mo bana-phrionnsa”, he replied, and quickly barked orders around in your stead.

Your chest felt heavy with responsibility and grief. What pained you the most was not being able to carry your brothers and sister with you back home. They would not be buried under the cairns near you family home with the rest of your ancestors.

And what was worst — thousands of lives now depended on you. The weight of your tribe's destiny heavily rested on your shoulders now, like Atlas carrying the heavens.

Maisie, Aodh and Somhairle had been lined up on a patch of wildflowers that you had picked yourself the night prior — their arms were threaded together with your sister in the middle. Your clansmen had also surrounded the makeshift burial pit with wood to aid the combustion.

As you placed the last stone on top of them, you also deposited a bright, bloomed thistle. The flower that blossomed in every nook and cranny of your beautiful motherland, despite the harsh winter or conditions it faced. Like the phoenix rising from the ashes, it would always come back, stronger and more brightful than ever.

Devotion, bravery, determination, and strength — the thistle was a badge of honour for the Caledonians.

With a renewed brawn unbeknownst to you, you threw the lighted torch and watched as the fire consumed the bodies underneath the stones.

There were no tears left within you. Only purpose and resolution.

The way back to Inbhir Nis was tiring and soul-crushing. Hiking through the Cairngorms had been a difficult task with so many people behind you, but luckily you all managed to make it through without any losses.

With each mile covered, you saw the devastation left behind by the Romans. If this was any indication of what awaited ahead, you should start bracing yourself for what you would see. It seemed that the Romans were set towards the northwest — Inbhir Nis was right in their path.

You quickly recognised the landscape as you walked towards Loch Moy. A thick, dark column of smoke towered above the pine trees. Your heart raced as you picked up your dark green skirt and ran towards the loch, ignoring the calls of your brother-in-law.

You could run through those woods blindly — this was the land where you were born, the land you were named after. Your name was an unusual one — Caledonia, in honour of the earth beneath your rushing feet. Just a few people called you Callie, mainly your family and closest friends. With your bright, fiery red hair, green almond eyes and a face dotted with freckles, you were the epitome of your people. That was probably why when someone new learned your name, they always said it suited you.

Dodging the last few trees, you made it to the edge of the loch. In the shallows, the crannog of Naimh, your community’s healer, was burning down to its foundation. You covered your mouth with a sombre expression, your eyes itchy because of the dense smoke and unspent tears.

The Romans had gotten to your settlement before you did.

“Callie, wait up”, said Torcall behind you, struggling to catch up with you.

He halted right behind you, the silence between you was almost tangible.

“The rangers have returned from their reconnaissance mission.” His voice was plain, contained. You turned your heard towards him, slowly, hardening yourself for his next words. “Your mother is dead.”

The last glimmer of hope within you vanished. A single tear skidded through your cheek — angrily, you wiped it off.

You were alone in this world. Everyone you cared for had been taken from you.

“Is everything to your liking, Dominus (Master)?”, the male roman servant asked in a low hush, head bowed, eyes fixed on the cobblestone.

“Yes, now leave”, Marcus dismissed him with a wave of his hand.

The General looked around him with a mixture of curiosity and disgust. He was accustomed to much more elegant surroundings. Although the barbarians did try, their architecture was nothing in comparison to Rome’s.

The castle he was in was small and it only had two floors. It was mainly made of sturdy, grey rocks and dark wood. The design was not very sophisticated, all square and rugged edges. It had two towers and a barbican. The decoration inside was bare, with just enough furniture and no luxuries.

The only warmth was brought by the colourful tapestries adorning the cold, thick walls — one had caught Marcus' attention at his arrival when he first entered the dais. It told a story he had not heard before.

A dragon-like figure lurked beneath the rippling surface of a lake, attracting the attention of the villagers. At dusk it would emerge, a guttural sound echoing in the dead of night, as if it was calling another. Any bìrlinns (wooden vessel) left on the shore would appear destroyed the next morning. Fishermen were worried and called upon the town's druids, afraid of the Loch Ness monster. To appease the beast, every full moon, the druids would whorship the creature, bringing oblations and sacrificies to quench its thirst.

Marcus made a mental note of keeping his distance from that Loch Ness. As a devoted Roman, he was wary of the mystic creatures that skulked in the depths of human fear.

Although he missed his home, he had several debts to pay. The Emperor would not accept no for an answer, so he had to be a reluctant participant in this incursion — in fact, neither Domitian nor Agricola had really asked him to tame the highlanders up in Caledonia. They knew his skills would be most needed in combat, having been praised by bards and poets alike after his many years in the battlefield.

At eight and forty, Marcus Acacius had had his good share of tragedy and death, both personal and in war. His life had not been easy, having to forge a name of his own since childbirth and then having been recently betrayed by his own spouse.

The thought of Livia still angered him — she had had the audacity of blaming him for her infidelity, accusing him of always being away, of loving Rome more than his own family. Her cheating had been going on for as many years as their arranged marriage, throwing a doubtful shade on his paternity to both his children.

His life had come crumbling down in the last few months, so maybe coming to Britannia had not been such a bad idea. Female adultery was a crime penalised with death and that was a decision that Marcus had yet to make — outing Livia’s unfaithfulness would condemn her to Pluto's realm. Did he really want that for who had been his wife for more than thirty years?

Pinching the bridge of his hooked nose, Marcus walked towards the only window in the room. The roman took a deep breath and exhaled steadily — he needed to think of something else.

His mind went back to the battle of Mons Graupius. The spilling of blood never became easier with time — if anything, it had become harder, splintering his soul further. If he closed his eyes, he could still hear the piercing, pained shriek of a woman as he imparted death on Murdoch of Inbhir Nis.

Her hair was dyed with black soot and tied back, her face covered in a blue paste and ash. He was too far to catch the colour of her eyes, but he thought them dark azure. The fierceness of her expression took him aback, her voice shouting a word he did not recognise. But his eyes did not have time to linger on the feral woman a few yards away, because a savage attacked him.

His hand stilled on the rocky window’s sill. The barbarians called this place Inbhir Nis. The stone castle was that of the chief’s family, atop of a hill with views to the scenery underneath. It was rudimentary and lacked many commodities — nothing comparable to his villa in Rome. The tribal settlement was formed of huts made of stone, timber and hay.

Agricola had decided to burn down the outskirts of the town and killed the wife of the clan chief making a macabre example of her, so the people would submit to the Roman’s yoke quickly, crushing any opportunity of rebellion. The message was clear: Rome would not tolerate being challenged. Anyone who did, would face the most painful of deaths. The governor left to go northward, leaving Marcus behind to rebuild the area to Rome’s standards. The emperor had deemed the location an important enclave for his empire, being the main town in the Moray Firth.

Marcus was standing in what he thought was the bedchamber of Murdoch. With the Overlord and his family alienated, the primitive people of the highlands needed educating and he had been given the task of doing so. Not a welcomed one, but he had a duty to Rome that had to be fulfilled.

With a heavy sigh, he undid the brooch at the base of his neck, relieving himself of the heavy, white sagum (cape) that was part of his attire. He threw it on the uncomfortable bed. He unfastened the golden, laurel-shaped bracelets around his wrists, and then proceeded to undo the tight knots that held his armour in place.

Then a knock on the thick, wooden door broke the silence of the room.

“Come in”, thinking it would be his male servant, he didn’t turn around.

“Dominus, dinner is ready”, a very soft voice with a very marked accent made him look over his shoulder.

A pair of very bright, almond-shaped, emerald-green eyes locked on his, framed by what he would describe as fire hair — so red it looked like a hellish aura crowning your head.

So bright were your eyes, he almost felt his soul being examined by your hypnotising gaze. Marcus had never seen eyes like those.

How dared he stand where your father did? Anger shimmered under your skin, but you kept it in check. When you realised you were holding his gaze for longer than what was appropriate for a servant girl, you averted your eyes, inspecting the stones under your feet.

Torcall called you mad for doing this, but you had made up your mind. If you really wanted to overthrow the Roman General and win back your family’s castle and land, you would need to sew yourself into his everyday life. Gain his trust, learn his secrets and use that information against him. Your people were counting on you for freedom, and you would not allow yourself to disappoint them. Even if it was the last thing you did.

“Who are you?”, his raspy voice filled the atmosphere as he resumed the task of undoing the ties on his armour.

Did he have no shame, undressing himself in front of a maid? Mind you, you were not an innocent servant, having been widowed recently. But still. The romans had no modesty, you assumed.

You had to think quickly. You had learnt that the governor and the general both thought the whole chief’s family dead, so you could not out yourself. A very few, selected people called you Callie, almost always in the intimacy of your home, when strangers were not around. Your nickname was precious to you because it was only used by those you loved.

“My name is Callie, Dominus”, you offered your nickname in a rusty Latin. It had been a while since you had to use a language that was not your native one.

“Callie.” The way your name rolled off his tongue gave you goosebumps. You didn’t like the way he pronounced it — it lingered in his mouth for too long, dragging each letter. You wished your words back, but you couldn't change it now.

Instead of clenching your jaw, you nodded. “Yes, my lord, I’m one of the servant girls who tended to the clan chief’s family before you.” You explained, your head still bowed.

You ventured your eyes up for a second, catching a glimpse of his naked torso. Unconsciously, you pursed your lips. The way your heart pounded loud for that one second made you furrow your brows in confusion.

He might be a gorgeous man, but he was a killer. And you had no taste for soulless murderers, that much you knew about yourself.

“Call my attendant, Atticus, to help me get ready for supper. I have no need of you. And ask the kitchen staff to heat some water and bring it up here.” His tone was emphatic, unwavering.

His rejection, in other circumstances, would have been most welcomed, but you needed him to trust you, to confide in you so you could plot his demise — to destroy him. This was not a good start to your plan, but you needed to play the long game.

“I could certainly help you with a bath now, Dominus, but your wish is my command.” You forced the words out, when in reality you wanted to spit them to his murderous face.

He just nodded in your direction, his movements stiff and measured. “Just my attendant will suffice, now go.”

With your fingers laced on your back, you curtsied, walking backwards towards the door of your father’s bedchamber. You could not seem too eager, or he would become suspicious.

When you were in the corridor with the door closed behind you, you took a deep breath and straightened your back.

You would not take no for an answer. Marcus Acacius would yield to you, whatever the cost.

@devilbat2 @subterralienpanda @lordofthundersstuff @just-mj-or-not

@grace16xx @killaqceen @minabarker @noisynightmarepoetry

@perfectlytenaciousrunaway @myheadspaceisuseless @imnvv @bekscameron

@immyowndefender @orchiddream108 @jungkooksmamii @jellybeanxc

@sjc7542 @triangleshapewinner @moongirlgodness @ijustlovemensm

@box-of-sarcasm @orcasoul @thesadvampire @shittypunkbarbeque

@penvisions @fairiebabey @blueturd16 @vestafir

@holla-at-me-hood @httpsastral @evangelinemedici @cathsteen

@ksxxxxxx @whoaitspascal87 @passionnant-peche @madnessofadaydreamer

@hufflepuff-in-narnia @akumagrl @bobcatblahs @thepalaceofmelanie

@itsbrandy @voidofendlessdarkness @tardy-bee @pascalislove

@inept-the-magnificent @dianomite @thereisaplaceintheheart @fridays13th

@witch-moon-babe @amortentiaxo @holaputanas @kmmg98

#marcus acacius#general marcus acacius#marcus acacius x oc#marcus acacius x reader#marcus acacius fanfiction#marcus acacius fic#gladiator#gladiator au#gladiator 2#gladiator 2 fanfiction#marcus acacius smut#marcus acacius x female reader#pedro pascal#pedro pascal character#pedro pascal fanfiction#pedro pascal x reader#pedro pascal fic#pedro pascal fandom#pedro pascal smut#pedro pascal cinematic universe#ppcu#marcus acacius x you#pedro pascal x you#pedropascaledit#ppascaledit#ppedit#enemies to lovers

217 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, I was reading about Gaelic evolution, today, kind of on accident, and I came across this discussion of o-stem and s-stem verbs(?) (Might have been nouns?) changing their conjugation/declension (i think they were talking about like 800-1200 more specifically, im not totally sure though) except none of the words had any o or s in them that I could see and I was wondering if you knew anything about this

Ah. Stems. If they're o-stem and s-stem they're probably nouns. Theoretically, I was introduced to the concept of stems as an undergrad. Nobody, however, ever thought to explain what the stems were for and why we might need to know them -- I suppose they thought we might have learned this in previous language studies at school, but I did French the usual English way, and thus learned very little grammar and no linguistics. So I treated this as fun but ultimately irrelevant bonus information and spent most of my undergraduate years deeply confused.

Five years later I was sitting in a modern Irish class with a teacher who also taught Old Irish and she was explaining declensions in the context of the genitive case. "This is the first declension, and therefore behaves like this," she said, and looked at me: "Finn, that's like an o-stem masculine in Old Irish."

Me: 🤯 Me: Wait. That's what the stems are for?! That wasn't just fun bonus information??? They actually tell you something?!

So that... cleared a few things up.

Anyway, when I was doing my MA, I had to actually learn them, and have subsequently figured out they can be pretty handy when you're staring at a word trying to work out what case it could possibly be in and whether it should be behaving like that. Who knew. It's almost like a proper understanding of grammatical principles is more helpful than just giving people a textbook from the 1970s and a set of paradigms from the 1920s that were both written with the assumption that the person would have studied large amounts of Latin.

But yes, very often you will look at a word, and it claims to be an o-stem, and you're like, but there's no o here, what is this about?? So what's that all about? Well, I believe, based on the little I've gleaned from hearing people who actually understand linguistics talk about them, that this reflects the word endings in a much earlier stage of the language development -- like, way earlier, we're talking Proto-Celtic, so by the time it's Irish that's already usually gone. For example, fer 'man' from Proto-Celtic *wiros. There's an O there! Or carpat 'chariot', from Proto-Celtic *karbantos. There's an O there too. Now both of these being o-stems makes more sense.

(That said, all the s-stems also seem to end in -os in Proto-Celtic, so what makes some of them o-stems and some of them s-stems when they both contain both of those things, I could not tell you. Frankly, I zone out whenever people start offering me reconstructed forms with asterisks in front of them, so I am the wrong person to ask for more detail on that 😅)

The person who is really into all this stuff is David Stifter, who wrote Sengoidelc, among other things. He's always talking about the linguisticsy side of things! But if all you want to know is why they're called that, I think "there used to be that letter there a long time ago even if now it's gone" is probably the important part, and as for why you need to know what stem it is at all, it's because that decides how it will behave in different cases. Which is a piece of information I really would've benefited from being given five years earlier than I was actually given it.

(In fairness to my Old Irish teachers, I think if they'd realised I hadn't grasped this concept, they would have explained it. I just hadn't even understood enough to realise that I was missing a crucial piece of information, and so didn't know to ask. I was, put simply, not very good at Old Irish in undergrad, and survived purely because our language exams were also literature exams and my essays pulled my overall marks up. This did not work during my MA, when language was a separate exam. I had to (re)learn so much grammar 😞)

#i just discovered that quin's old irish workbook is on jstor but cambridge does not have access to it#but if anyone wanted a digital copy i guess it's more viable than in the past#answered#anon good sir#old irish#medieval irish

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

English is part of a large language family that includes French, Welsh, Polish, Persian, Greek, and Albanian. They stem from a common ancestor reconstructed as Proto-Indo-European. The cardinal numerals from 1 to 10 illustrate their relationship well. Click the image for a selection.

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#english#latin#french#german#spanish#welsh#irish#sanskrit#persian#polish#russian#italian#gothic#proto-germanic#proto-celtic#proto-indo-iranian#proto-balto-slavic#lithuanian#ancient greek#albanian#icelandic

101 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you give an overview of your conworld and language for new people?

Absolutely! :D

The World

The setting I write in (hereafter "Boralverse") is an alternate history of Earth. The original difference from our own history (hereafter "IRL") is the existence of the island of Borland (Istr Boral) between Great Britain and Denmark, inspired by the IRL existence of Doggerland.

The human pre-classical history of Borland can be summarised as:

With sea level rise about 8k years ago, Borland was cut off from the continent and from Britain (this is when Doggerland was submerged IRL); some Stone Age people remain. They leave some monuments—burial mounds, the Çadrosc labyrinth—and were farmers, but they had no writing or ironworking.

The Celts arrive in Borland shortly before they settle Britain in the second millennium BCE, taking up iron tools and establishing many tribal groups. Due to some later migration from Britain to Borland, they speak a language (Borland Celtic) which is most closely related to Proto-Brythonic.

I assume that as far as possible the history of the rest of the world is indistinguishable from the IRL history up to this point. I continue to do so while the Romans invade and settle Borland shortly after Britain, despite conceding to credulity and allowing a few classical references:

...in Ptolemy's description of the Pritannoi we can understand he referred to the Insular Kelts of Ireland, Britain and Borland as a whole... ...contrasting Hadrian's policies in Britain and in Borland is vital for understanding their different fates in the post-Classical age...

where I admit that the Roman Empire having an entire additional province should probably have some observable effects.

Once the Western Roman Empire collapses, I start properly diverging Boralverse history from IRL history. This begins with a different pattern of Anglo-Saxon migration; the two petty kingdoms of Angland and Southbar arise in western Borland, while the settlement of England proceeds slightly slower than IRL.

Historical divergence spreads through western Europe over the next few centuries, and by 1000 CE things are beginning to go off the rails all across Eurasia and North Africa. I leave the history of the Americas the same until Old World contact (via Basque fishermen stumbling across Newfoundland in 1470 CE), and likewise with Australia.

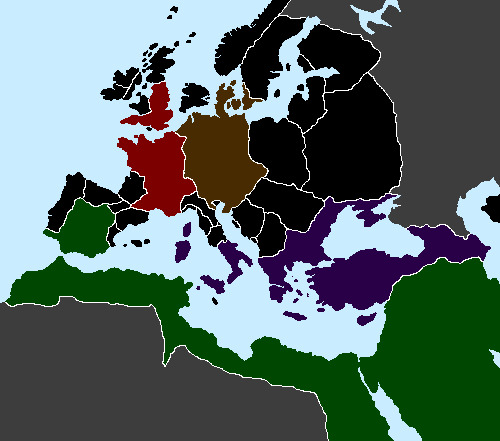

The map below shows Europe in 1120, during the Second Tetrarchy Period. At this time, Europe was unusually centralised, with four great empires: the First Drengot Empire (red), the German Empire (brown), the Second Roman Empire (purple) and the Single Caliphate (green).

In the modern era, my hope is that the Boralverse world feels fractally uncanny; at every scale something is unexpectedly different, from political borders and languages to fashion and pop culture references.

For clarity, I employ an inconsistent Translation Convention when writing from a Boralverse perspective, mostly using IRL English but peppering in calques of Boralverse English jargon for flavour, such as threshold force "nuclear power" or jalick "garment socially equivalent to a tuxedo".

The Language

The original motivation for this alternate history setting is Borlish (Borallesc), the Romance language spoken on Borland.

It picked up a few Borland Celtic loanwords from the existing population at the time of the conquest (macquar ~ Welsh magu "raise, rear"; vrug ~ Welsh grug "heather"), but was much more influenced through the first millennium by Anglo-Saxon settlement and then Norse conquest during the Viking Age. The following is an example of late Old Borlish (ca. 1240):

…sovravnt il deft nostre saȝntaðesem eð atavalesem n iȝ atrevre golfhavn seȝ hamar dont y verb divin ismetre ac povre paian. peðiv soul ez font istovent por vn nov cliȝs d istroienz istablir… …uphold our most sacred and ancient duty to let Gulfhaven be the centre from which we will send the Word of God to pagan lands. We ask only for the necessary funds for a new teachinghouse…

The Modern Borlish language has undergone spelling standardisation (most recently deprecated some irregular spellings in 1870), and contains many more Latin and Greek loanwords, along with borrowings from languages across the world.

Y stal zajadau dy marcað nogtorn accis par lamp fumer eð y lun fragnt de mar receven cos equal party a domn pescour pevr jarras e fenogl gostant tan eð eç nobr robað n'ornament fluibond ant queldin raut frigsað ne papir cerous. The night market's various stalls lit by smoky lamps and the sea-shattered moon welcomed flocks of fishwives sampling paprika and fennel as well as notables in flowing finery carrying stir-fried suppers in wax papers.

In terms of sound changes and grammatical developments, the major points include:

Intervocalic lenition /p t k b d g/ > /v ð j ∅ ∅ ∅/: catēna > caðen "chain", dēbēre > deïr "must".

The use of ç (and c before e i y) for /ts/, and the use of g in coda to represent /j/. Along with some vowel shifts, this leads to things like cigl /tsajl/ "darling".

Total loss of final consonants in multisyllable words, including -s, which leads to:

Collapse of noun declension, including number; Borlish does not mark number on nouns, and if it wants to it uses demonstratives or simply relies of verb agreement: l'oc scuir pasc, l'ec scuir pascn "this boy eats, these boys eat".

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

basically all literature dealing w the origin of the Etruscans seems to assume a binary choice between the two origin myths proposed in Antiquity—that the Etruscans are autochtonous to Italy (as per Dionysus of Halicarnassus), or that they migrated to Italy from Anatolia (as per Herodotus). this assumption can sometimes lead to some funny places, like that one article that famously confirmed Etruscans are genetically indistinguishable from their Italic neighbours ascribing the association of the Iron Age Villanovan culture w the Etruscans to Dionysus, which, like. when Dionysus of Halicarnassus claimed the Etruscans literally sprouted from the earth, I don't think he had the Villanovan culture of Iron Age Tuscany in mind, no.

incidentally, and apparently following the same logic I'm criticising here, Wikipedia quotes that same article as evidence that the presence of Etruscan (or, rather, Tyrrhenian) in Italy predates the arrival of Indo-European languages to the peninsula. well, to me, the fact Etruscans are genetically indistinguishable from their Italic-speaking neighbours does not make me think their language must predate the arrival of Italic to Italy—if anything, it makes me think the Proto-Tyrrhenians were pushed into Italy by the Proto-Italics!

(as for what sequence of archaeological cultures might then be associated w the Proto-Tyrrhenians prior to the Iron Age... I'm not sure! apparently the Villanovan culture was preceded by a Bronze Age "Proto-Villanovan" phase—though I've found at least one article (from the 70s, in Italian) that wasn't very optimistic abt there ever being a single Proto-Villanovan culture; Italian Wikipedia considers the Canegrate culture of upper Lombardy a close relative of the Proto-Villanovans, though it follows the customary & simplified association of the larger Urnfield tradition w Proto-Celtic... and this all still leaves like a billion years between the Etruscans and the Neolithic, ofc. I'll have to do some more digging)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Take this how you will:

From the Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic 2017

This will mean more to folks in the UK, so don't worry if it seems a bit random.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

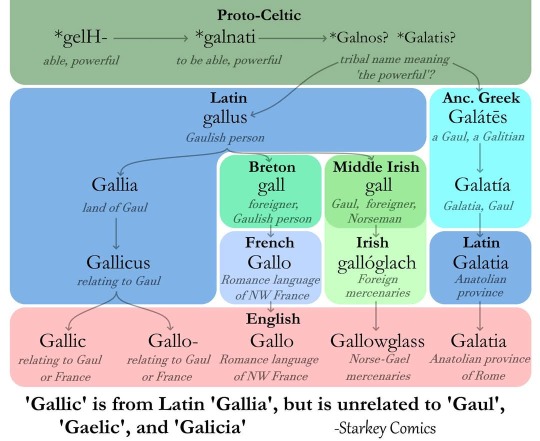

From Starkey Comics on Facebook: New post!

Have you ever noticed how many names associated with Celtic peoples seem to be related? Many of them have names that start with something like "gal".

Well, some of them *are* related, some of them aren't! The whole thing is actually a bit of a mess.. so I thought I'd try to clear things up with an image.

Well, it spiralled into 4 images, because there are basically there are 4 groups you can sort these terms into:

1) Gallic, Gallo-, Gallo, Galloglass, Galloway (not shown here) and Galatia all come from a Celtic tribal name. This name was "Gallus", in Latin, which referred to the Celtic people of Gaul.

2) (Corn)wall, Wales, Gaul, Walloon, Wallachia are all from a Germanic word originally meaning "foreigner". "Galles", the French word for "Wales", is also in this group, adding another "gal" word for us.

And yes, that means "Gaul" (which is from a Germanic name for the territory) and "Gallus" the Latin name for the territory, are unrelated!

3) Gael and Gaelic are from an Brittonic word meaning "wildman", as is "Goidelic", the name we use to group the Irish, Manx, and Scottish Gaelic language.

4) And finally Galicia and the second half of Portugal *might* be related to each other, but are unlikely to be related to any of the names above. The most common theory is that they are named for a Celtic group that inhabited that area, who may have named themselves using a word derived from the Proto-Celtic word for forest. This one is the shakiest, as both Galicia and Portugal have disputed ultimate origins.

Galway in Scotland and Galicia in Eastern Europe are also unrelated to any of these (and each other).

13 notes

·

View notes