#old irish

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Pangur Bán

I and Pangur Bán, my cat,

'Tis a like task we are at;

Hunting mice is his delight,

Hunting words I sit all night.

Better far than praise of men

'Tis to sit with book and pen;

Pangur bears me no ill-will,

He, too, plies his simple skill.

'Tis a merry thing to see

At our tasks how glad are we,

When at home we sit and find

Entertainment to our mind.

Oftentimes a mouse will stray

In the hero Pangur's way;

Oftentimes my keen thought set

Takes a meaning in its net.

'Gainst the wall he sets his eye

Full and fierce and sharp and sly;

'Gainst the wall of knowledge I

All my little wisdom try.

When a mouse darts from its den,

O! how glad is Pangur then;

O! what gladness do I prove

When I solve the doubts I love.

So in peace our task we ply,

Pangur Bán, my cat, and I;

In our arts we find our bliss,

I have mine, and he has his.

Practice every day has made

Pangur perfect in his trade;

I get wisdom day and night,

Turning darkness into light.

This Old Irish poem was written by a scribe in or near Carinthia on a copy of St. Paul's Epistles about the close of the eighth century.

Translation by Robin Flower, in The Poem-Book of the Gael, 1913

Article originally published on: Thursday 9th October 1913

Above Image credit: Pangur Ban by RosaleeLuAnn on DeviantArt

Below: Wikipedia page of the Reichenau Primer.

81 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, I was reading about Gaelic evolution, today, kind of on accident, and I came across this discussion of o-stem and s-stem verbs(?) (Might have been nouns?) changing their conjugation/declension (i think they were talking about like 800-1200 more specifically, im not totally sure though) except none of the words had any o or s in them that I could see and I was wondering if you knew anything about this

Ah. Stems. If they're o-stem and s-stem they're probably nouns. Theoretically, I was introduced to the concept of stems as an undergrad. Nobody, however, ever thought to explain what the stems were for and why we might need to know them -- I suppose they thought we might have learned this in previous language studies at school, but I did French the usual English way, and thus learned very little grammar and no linguistics. So I treated this as fun but ultimately irrelevant bonus information and spent most of my undergraduate years deeply confused.

Five years later I was sitting in a modern Irish class with a teacher who also taught Old Irish and she was explaining declensions in the context of the genitive case. "This is the first declension, and therefore behaves like this," she said, and looked at me: "Finn, that's like an o-stem masculine in Old Irish."

Me: 🤯 Me: Wait. That's what the stems are for?! That wasn't just fun bonus information??? They actually tell you something?!

So that... cleared a few things up.

Anyway, when I was doing my MA, I had to actually learn them, and have subsequently figured out they can be pretty handy when you're staring at a word trying to work out what case it could possibly be in and whether it should be behaving like that. Who knew. It's almost like a proper understanding of grammatical principles is more helpful than just giving people a textbook from the 1970s and a set of paradigms from the 1920s that were both written with the assumption that the person would have studied large amounts of Latin.

But yes, very often you will look at a word, and it claims to be an o-stem, and you're like, but there's no o here, what is this about?? So what's that all about? Well, I believe, based on the little I've gleaned from hearing people who actually understand linguistics talk about them, that this reflects the word endings in a much earlier stage of the language development -- like, way earlier, we're talking Proto-Celtic, so by the time it's Irish that's already usually gone. For example, fer 'man' from Proto-Celtic *wiros. There's an O there! Or carpat 'chariot', from Proto-Celtic *karbantos. There's an O there too. Now both of these being o-stems makes more sense.

(That said, all the s-stems also seem to end in -os in Proto-Celtic, so what makes some of them o-stems and some of them s-stems when they both contain both of those things, I could not tell you. Frankly, I zone out whenever people start offering me reconstructed forms with asterisks in front of them, so I am the wrong person to ask for more detail on that 😅)

The person who is really into all this stuff is David Stifter, who wrote Sengoidelc, among other things. He's always talking about the linguisticsy side of things! But if all you want to know is why they're called that, I think "there used to be that letter there a long time ago even if now it's gone" is probably the important part, and as for why you need to know what stem it is at all, it's because that decides how it will behave in different cases. Which is a piece of information I really would've benefited from being given five years earlier than I was actually given it.

(In fairness to my Old Irish teachers, I think if they'd realised I hadn't grasped this concept, they would have explained it. I just hadn't even understood enough to realise that I was missing a crucial piece of information, and so didn't know to ask. I was, put simply, not very good at Old Irish in undergrad, and survived purely because our language exams were also literature exams and my essays pulled my overall marks up. This did not work during my MA, when language was a separate exam. I had to (re)learn so much grammar 😞)

#i just discovered that quin's old irish workbook is on jstor but cambridge does not have access to it#but if anyone wanted a digital copy i guess it's more viable than in the past#answered#anon good sir#old irish#medieval irish

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! I was wondering, do you speak any old Irish, and if so, how did you learn it? Im interested in learning!!

I can read and, to a certain extent, write in Old Irish. (Most people don't speak it, but we are taught how to pronounce it...which was actually an impediment to me learning Modern Irish, because I'd had the older stuff first.)

There are a couple of options! The easiest, if you have the time + money, is always to take courses, which is how I did it. As part of my MA, I was required to take classes in both Old Irish and Welsh, and I've continued taking courses in my PhD. Now, if, for some reason, you don't have the ability to casually drop a few thousand Euros on a MA degree, there are a couple of sources I can point you to. If you do this, I can also try to walk you through it to the best of my ability, and I can assign you homework.

First off: Quin's Old Irish Workbook and Strachan's Paradigms. With most copies of Strachan's paradigms, like the one you see on Archive.org, it's kind of neat because people add notes to it over time, so it's also deeply personalized to the Celticist, like a family bible.

I'll tell you immediately: the current editions of both of these are quite frail. They fall apart quite easily, since they're softcover. (I eventually had mine custom-bound together.)

Stifter - Sengoidelic: Old Irish For Beginners. It's VERY in-depth, slightly intimidating, but there are lovely cartoons of sheep to make it slightly less scary.

Ranke de Vries - A Student's Companion to Old Irish Grammar

Antony Green - Old Irish verbs and vocabulary

Rudolf Thurneysen (trans. D.A. Binchy): A Grammar of Old Irish. I'm going to tell you now: This book is DENSE. It is technical. It is OLD. It is EXPENSIVE (especially if you want a good copy, since the one I got was so thick that it was actively falling out of its hardcover binding; I ended up buying an older copy.) BUT...it will help your Old Irish. It's still considered to be the definitive book on Old Irish, even though it's eighty years old at this point. So: I recommend it, but I'd recommend it after some of the others. De Vries is probably the most beginner friendly.

Now, after all that, you will need places to practice your Old Irish.

I highly recommend anything from DIAS' Medieval and Modern Irish series -- they tend to have very good dictionaries, so it isn't like you're being tossed into the deep end. Most of these are technically later than the Old Irish period, but they ought to give you a taste for the basics. (The problem with Old Irish is that Middle Irish was basically creeping in even from the time of some of our earliest texts.) One of these, which you can get online, is Compert Con Culainn and Other Stories, ed. Van Hamel.

Also: Thurneysen's Scéla Mucce Meic Dathó.

Ernst Windisch: Irische Texte mit Wörterbuch

If you can get ahold of it, Vernam Hull's edition of Longes mac nUislenn is also excellent.

When you're reading these texts, I recommend you to make a note of the case, number, and gender (nouns) or the classification, tense, number, whether it's adjunct or conjunct, and whether it's deuterotonic or prototonic, etc. (verbs). Mutations, including invisible mutations (nouns and prepositions). Every bit of information you can parse out, so you can instantly recognize words as you come across them and what they are doing in a sentence.

Finally:

I'm sure you've heard this before, but Old Irish is notoriously difficult as a language. Having Modern Irish helps (particularly re: vocabulary, where you'll see a lot of familiar words), but the language has also radically changed. The verb in particular has totally changed the way that it's formed, going from a predominately synthetic language to a predominately analytical language (Munster Irish is closest to Old Irish in terms of verb formation, though each dialect preserves little bits of it.) Old Irish is significantly richer as far as vocabulary, and it had many more declensions (stems), each of which has its own way of doing things. You had more tenses. You had a neuter gender (though that was already going by the wayside). The definite article was totally dependent on the case, number, and gender of the noun (preserved these days in 'an' and 'na', but it used to be much more comprehensive). You had a full dative and accusative case (no ablative, thank God.) You had infixed particles, and those were divided into three classes depending on the classification of the verb. And adding to all that is that the language was already changing, so the Old Irish that you will be learning in the textbooks is not 100% what will be reflected in the editions. I've been doing this for six years and I still need to use a dictionary + paradigms. (Keeping in mind, though, that my Old Irish has also actively decayed in the States.)

The point isn't "don't do it" -- I'm not in the business of scaring people off. BUT I'm saying that it's okay if it takes a while, or if it seems overwhelming or even impossible. (It's also okay if it comes naturally; some people ARE naturally good at it.) The best piece of advice I have EVER gotten about Old Irish was what an older gentleman told me my first day of my MA program, which is: "Old Irish becomes a lot easier when you remember you'll be learning it your entire life." Take your time, enjoy it, let it sink in, play with it. Pursue the texts you want to read, read the texts you already enjoyed in English in Old Irish, even if it's a couple of lines at a time. ENJOY the process, and don't feel pressured to learn everything at once.

You have a lifetime to learn it.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Greek híppos, Latin equus, Irish each, and Icelandic jór all mean 'horse', and Spanish yegua and Romanian iapă mean 'mare'. They're very different, yet they ultimately stem from the same Proto-Indo-European word. They drifted apart due to the sound changes they underwent.

What would their modern English, German, Dutch, French and Italian cognates look like if they had survived? I tell about it on my Patreon.

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#english#latin#french#dutch#spanish#german#lingblr#old irish#irish#manx#scottish gaelic#celtiberian#gaulish#proto-germanic#old english#old saxon#proto-norse#old norse#icelandic#gothic#lithuanian#romanian#sardinian#old french#occitan#catalan

237 notes

·

View notes

Text

what kind of niche do you have to be in to write a book in german about old irish grammar

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

OLD IRISH HAD SINGLE DUAL AND PLURAL NOUNS IT HAD DEDICATED ACCUSATIVE AND DATIVE CASES IM SO MAD

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moí Coire coir Goiriath or

'The Cauldron of Poesy'

An untitled Old Irish poem by an unknown poet written in the early 8th century (Breatnach 1981). In Irish, it is commonly known by the first line of the text: "Moí Coire coir Goiriath". The title 'The Cauldron of Poesy' was given to it centuries after it was written. The complete text of the poem, along with the Middle Irish annotations and glosses added by a later scribe, is found in the manuscript TCD MS 1337.

This poem is about the kinds of knowledge and ability required to be a great poet. It describes 3 metaphorical cauldrons found within each person. These cauldrons are vessels for different kinds of knowledge and skills. They are called Coire Érmae (the Cauldron of Progression), Coire Sofis (the Cauldron of Knowledge), and Coire Goiriath (Breatnach 1981, 1990). They can be upright (full of knowledge), inclined (half-full), or upside-down (empty), and events during a person's life can change the position of the cauldrons.

8th-9th c. bronze vessel from the Derrynaflan Hoard

This poem is frequently misinterpreted as describing some kind of metaphysical energy centers. Some people go as far as to link the cauldrons to Asian concepts like qi or chakras. The inaccurate translations used in these interpretations obscure the fascinating blend of Christian, Pagan, and possibly ancient Greek influences in this complex work of medieval Irish poetic lore.

Poetry was a complicated profession in medieval Ireland. Professional poets, known as filid, had a minimum of 7 years of formal education and were divided into 7 different grades with ánroth and ollamh being the 2 highest. In addition to writing and preforming poetry, an ollamh was required to memorize genealogies and compose satires (Carey 1997, Breatnach 1983, Breatnach 1981, eDIL). Bards were poets who lacked formal education and were considered to be of inferior grade to a fili (eDIL, MacNeill 1924).

I don't feel qualified to talk about these topics in depth, but I want to share an accurate translation of the poem and to discuss at least some of its cultural elements.

I know of 2 authoritative translations of this poem, one by P. L. Henry (1980) and one by Liam Breatnach (1981) which has some additions and corrections (Breatnach 1984, 1990, 2023). The translation of the poem I give here is almost entirely Breatnach's with the exception of a small section that I rewrote, because I found Breatnach's wording confusing. For the glosses and annotations, I included a few of Henry's translations and some additional information from other authors. My changes and additions are in purple. I chose to leave out more than half of the annotations, because there were so many they overwhelmed the poem. This did mean losing some information about the role of poets in medieval Irish society.

We don't actually know what the word goiraith means (eDIL). Henry translates it as warming, incubation, or maintenance, based on the inference that goiraith comes from gorad (heating or warming), the intransitive form of guirid (Henry 1980). This interpretation doesn't make sense semantically in the context of the poem. The gloss for goiraith translates as, "i.e. 'it has closed off great falsehood', i.e. 'near to me in every land'," (Breatnach 1981). The text of the poem indicates that the Cauldron of Goiraith is related to having knowledge of language and grammar, and to learning and knowledge in childhood (Breatnach 1981). I don't see how warming/incubation could relate to either closing off lies or knowing grammar.

In addition to not fitting the semantic context, the interpretation of goiraith = gorad = warming doesn't fit the poetic form. The 3 cauldrons form a triad in the poem, and triads in poetry are typically written using parallel structure. The names of the other 2 cauldrons, sofis (knowledge) and érmae (progression), are both nouns (Breatnach 1981, 1990), so it follows that goiraith should also be a noun. Guirid/gorad is a verb (Henry 1980). Breatnach identifies goiraith as a compound noun with the first syllable likely being gor 'warm.' He suggests that goiraith might mean something like 'raw material' but stresses that this translation is "speculative in the extreme; the only thing that we can be reasonably sure of is that it has to do with the initial stages of study" (Breatnach 1981).

Old Irish glossary for this post:

Amairgen: mythical ollamh of ancient Ireland

ánroth: the second highest rank of fili (eDIL)

bairdne: bardic craft or metre, a type of poetry considered inferior to the work of a fili (eDIL)

Éber and Donn: mythical Irish kings

Érmae: progression (Breatnach 1990) or motion (Henry 1980)

fili (pl filid): a professional poet with at least 7 years of formal education (Breatnach 1983)

imbas: poetic inspiration or prophetic knowledge which poets (filid) obtained through magical or supernatural means (eDIL, Carey 1997)

ollamh: the highest rank of fili (eDIL)

raind: verses of poetry? (cf eDIL rann)

síd: fairy mound (eDIL)

túath: group of people or territorial unit (eDIL)

(I apologize for the formatting. I can't figure out how format this nicely on tumblr.)

'The Cauldron of Poesy' translated by Liam Breatnach:

Mine is the proper Cauldron of Goiriath,(1) warmly God has given it to me out of the mysteries of the elements;(2) a noble privilege which ennobles the breast is the fine speech which pours forth from it.(3) I being white-kneed, blue-shanked,(4) grey-bearded Amairgen, let the work(5) of my goiriath in similes and comparisons be related - since God does not equally provide for all, inclined, upside-down (or) upright- no knowledge,(6) partial knowledge(7) (or) full knowledge,(8) in order to compose poetry for Éber and Donn with many great chantings,(9) of masculine, feminine and neuter,(10) of the signs for double letters, long vowels and short vowels, (this is) the way by which is related(11) the nature of my cauldron.(12) 1 goriath, i.e. 'it has closed off great falsehood', i.e. 'near to me in every land'. 2 Well has God given it to me out of the mysteries of the elements, or 'that naming which ennobles' is a raw instrument which He has granted to me out of the mysteries of the elements. 3 which pours forth poetry from it. 4 a tattooed shank, or who has the blue tattooed shank. 5 What my cauldron does is the relation of poetry on which there are said to be many forms, i.e. white and black and speckled, or the colour of praise on praise. 6 when it is upside-down, i.e. in foolish people. 7 inclined, i.e. in those who practice bairdne and raind. 8 when it is supine, i.e. in ánroth's of knowledge and poetic art. 9 with numerous displays out of the many 'great seas' of poetry, i.e. many chantings of poetry. 10 Old Irish had 3 grammatical genders. 11 This is the law which I relate about them, or it is the declaration by which poetry is related. 12 This is the function of my cauldron. I acclaim the Cauldron of Knowledge where the law of every art is set out as a result of which prosperity increases(1) which magnifies(2) every artist in general which exalts a person(3) by means of an art. 1 It confers increase of wealth on everyone. 2 'It makes great of' every art in general, or it generally 'makes great of' him who has that skill. 3 It gives exaltation to persons together with granting something to them, or his art exalts every person.

Where is the source of poetic art in a person; in the body or in the soul?

Some say in the soul since the body does nothing without the soul. Others say in the body since it is inherent in one in accordance with physical relationship, i.e. from one's father or grandfather,(1) but it is more true to say that the source of poetic art(2) is and knowledge is present in every corporeal person(3), save that in every second person it does not appear; in the other it does.

1 a fili only had full status (honor-price) if his father or grandfather was a fili (Corthals 2014). 2 of bardic art. 3 that it is in the body.

What does the source of poetic art and every other knowledge consist of? Not difficult; three cauldrons are generated in every person, i.e. the Cauldron of Goiriath and the Cauldron of Progression and the Cauldron of Knowledge.

The Cauldron of Goiriath,(1) it is that which is generated upright in a person from the first; out of it is distributed knowledge to people in early youth.

The Cauldron of Progression, then, after it has been converted(2) it magnifies; it is that which is generated on its side in a person.

The Cauldron of Knowledge, it is that which is generated upside down, and out of it is distributed(3) the knowledge of every other art besides poetic art.

1 a cauldron in which 'great falsehood' has been 'closed off'. 2 Afterwards, after being turned over, it magnifies a person. 3 measured.

The Cauldron of Progression,(1) then, in every second person it is upside down, i.e. in ignorant people. It is on its side in those who practice bairdne and raind. It is upright in the ánroth’s of knowledge and poetic art.(2) And the reason, then, why everyone else does not practice at that same stage is because the Cauldron of Progression is upside down in them until sorrow or joy converts it.

How many divisions are there of the sorrow which converts it? Not difficult; four: longing,(3) grief,(4) and the sorrow of jealousy,(5) and exile for the sake of God,(6) and it is internally that these four make it upright,(7) although they are produced from outside.

1 a cauldron 'which turns over afterwards' in him. 2 the ollam of bardic art. 3 for his father. 4 for friends (Henry 1980). 5 after cuckolding. 6 on account of the extent of his sins. 7 it is out of its interior that these four convert the cauldron, although they are put into it from outside.

There are, then, two divisions of joy through which it is converted into the Cauldron of Knowledge, i.e. divine joy and human joy.

As for human joy, it has four divisions: (i) the force of sexual longing, and (ii) the joy(1) of safety and freedom from care, plenty of food and clothing until one begins bairdne,(2) and (iii) joy at the prerogatives of poetry after studying it well, and (iv)* joy(3) at the arrival of imbas which the nine hazel trees of fine fruit at Segais(4) in the síd’s collect and which is sent upstream(5) along the surface of the Boyne, as extensive as a ram’s fleece(6), swifter than a racehorse, in the middle of June once every seven years.*

1 after (recovering from) sickness. 2 until he practices poetry. 3 at the coming of imbas along the Boyne or the Graney, ie a bubble which the sun cause on the plants, and whoever consumes them will have an art. 4 Segais is a well at Síd Neachtain which is the source of the River Boyne according to the Dindsenchas (Gwynn 1913). 5 Possibly referring to the hazel nuts falling into the well and being eaten by salmon. See discussion on imbas below. 6 ('extensive as a ram's fleece' refers to the surface area of the river covered). (A ram’s fleece being the largest size of fleece) *Division (iv) is the section of the translation I altered.

Divine joy, moreover, is the coming of divine grace to the Cauldron of Progression, so that it converts it into the upright position, as a result there are people who are both divine and secular prophets and commentators(1) both on matters of grace and of (secular) learning, and they then utter godly utterances and produce the corroborations(2), and their word are maxims and judgments, and they are an example for all speech. But it is from outside that these make the cauldron upright,(3) although they are produced internally.

1 (ie people versed in both secular and ecclesiastical learning) as were Cumain, etc. Colmán mac Lénin and Colum Cille. 2 (that is, commentaries confirming the truth of Scripture (Breatnach 2023)). 3 it is from outside that these 'are handed over’ into his cauldron. although they are produced on the inside, i.e. it is outside the person that the divisions of enlightenment 'operate' the converting of the cauldron, while composing poetry (?) i.e. the performing of their deeds caused the converting of the cauldron.

Concerning that, what Néde mac Adnai said: I acclaim the Cauldron of Progression with understandings of grace with accumulations of knowledge with strewings of imbas, (which is) the estuary of wisdom the uniting of scholarship the stream of splendor the exalting of the ignoble(1) the mastering of language quick understanding the darkening of speech the craftsman of synchronism the cherishing of pupils, where what is due is attended to where senses are distinguished where one approaches meanings(2) where knowledge is propagated where the noble are enriched where he who is not noble is ennobled, where names are exalted(3) where praises are related by lawful means with distinctions of ranks with pure estimations of nobility with the fair speech of wise men with streams of scholarship, a noble womb in which is cooked the basis of all knowledge(4) which is set out according to law which is advanced to after study which imbas quickens(5) which joy converts which is revealed through sorrow; it is an enduring power whose protection does not diminish. I acclaim the Cauldron of Progression. 1 ‘Its essence raises up' the ignoble people to make them of noble status ie with regard to equal honor-price. 2 Many varieties of knowledge are approached in it, i.e. tales and genealogies. 3 It gives exaltation to the names of the people to whom praises are made if they are uttered according to lawful means. 4 The imbas of the Boyne which is distributed lawfully afterwards. 5 The imbas of the Boyne or the Graney moves the cauldron.

What is the Progression? Not difficult; an artistic* ‘noble-turning’(1) or an artistic 'after-turning'(2) or an artistic course, ie it confers knowledge(3) and status and honour after being converted. *The MS has sai here, Breatnach tentatively interprets this as soí (artistic) 1 The 'conversion of knowledge’ to that which it has not done before is noble. 2 or 'which reverts afterwards' to that which it has done. 3 poetry or eloquence.

The Cauldron of Progression it grants, it is granted it extends, it is extended it nourishes, it is nourished(1) it magnifies, it is magnified it requests, it is requested of(2) it acclaims, it is acclaimed it preserves, it is preserved it arranges, it is arranged it supports, it is supported. Good is the source of measuring,(3) good is the acquisition of speech,(4) good is the confluence of power,(5) which builds up strength. It is greater than any domain, it is better than any patrimony, it brings one to wisdom,*(6) it separates one from fools.

1 He feeds a person together with (his) retinue, and he is fed together with (his) retinue, i.e. he provides entertainment and entertainment is provided for him. 2 He makes demands on the members of the túath, and entreaties are made to him for their forcibly removed cattle'. (This gloss refers to the function of the poet in enforcing claims on behalf of the members of his túath outside the boundaries of the túath, his means of enforcement being satire, and to the entitlements due to him for performing this function (Breatnach 1984).) 3 Good is the cauldron out of which one measures by letter and verse-foot. 4 Good is the cauldron in which is the 'fire of knowledge' 5 Good is the cauldron out of which all this is obtained. *Henry translates this line as 'it brings to (the grade of) a scholar'. 6 the same honour-price as a king. This gloss refers to the fact that an ollamh was considered worthy of the same honor-price as a king in medieval Ireland (Carey 1997).

Discussion: Divine Joy, Imbas, and Philosophy

An early 8th century composition date (Breatnach 1981) means that this poem was written a few centuries after the arrival of Christianity to Ireland. That the original author was Christian can be seen in the description of the divine joy that turns the Cauldron of Progression. Divine grace and divine prophets are common themes in Christian writing. The consistent use of God singular (Dia) as a proper noun and the mention of the body and soul as 2 separate entities also indicate a Christian author (cf Henry 1980). The mentions of imbas, however, suggest the acceptance of continued Pagan magic practices by the Christian author (Carey 1997).

The early 10th c. text Cormac’s Glossary clearly marks imbas as Pagan magic when it condemns the ritual of imbas forosnai for requiring offerings to Pagan gods (Russell 1995, Carey 1997). This attitude is in sharp contrast with earlier Irish texts like Bretha Nemed where having imbas forosnai is considered a required qualification for an ollamh (Carey 1997). 'The Cauldron of Poesy' is, perhaps, a middle ground between a pre-Christian norm, and later Christian intolerance. It categorizes imbas as one of the 4 kinds of human joy that can turn the Cauldron of Progression, something which is beneficial for an ollamh to have but not essential (Carey 1997).

How did a medieval poet obtain the supernatural knowledge known as imbas? In the ritual described in Cormac’s Glossary, the poet chews on raw meat, chants over his hands, and then sleeps with his palms against his face (Russell 1995), a practice which bears no resemblance to the one hinted at in 'The Cauldron of Posey'. Some modern scholars have questioned whether Cormac actually knew what he was talking about (Carey 1997). Some later medieval sources are more useful for making sense of the the arrival of imbas on the River Boyne mentioned in the poem.

The Dindsenchas about the River Shannon mention 9 hazels growing around the well of Segais which is the source of 7 rivers. The hazels, which are associated with poetic wisdom, drop their nuts into the water. The nuts are then eaten by salmon (Gwynn 1913). The 12th c. Macgnimartha Find explicitly connects eating salmon from the Boyne to gaining imbas. It tells how Finn Éces spent 7 years by the Boyne waiting to catch a salmon that would grant him knowledge only to have his student Fionn mac Cumhaill accidentally eat a bit of the fish while cooking it and gain the knowledge of imbas forosnai instead (Carey 1997). Salmon swim upstream to breed during the spring and summer in Ireland (Inland Fisheries Ireland) which might explain why the poem describes imbas as being sent upstream in the middle of June.

Based on these sources, it appears the ritual for gaining the joy of imbas was simply: go to the Boyne on the summer solstice of the 7th year, catch a salmon, and eat it. How you identified the correct year, I don't know, but perhaps it was linked to the 7 years of a fili's education.

Although the joys which turn the Cauldron of Progression could be either Christian or Irish Pagan, the metaphor of the cauldrons appears to have a completely different origin. The 3 cauldrons serve as vessels for different things. Coire Goiriath, given out of the (natural) elements, contains basic childhood knowledge. Coire Érmae (Progression) contains the capacity to expand a person's knowledge based on experiences of joy or sorrow. Coire Sofis (Knowledge) contains advanced knowledge of the arts. This setup bears a striking resemblance to Aristotle's 3-part concept of the human soul. Aristotle divides the soul into (1) the nutritive soul, possessed by all living things, which contains the most basic faculties necessary for survival, (2) the animal soul, possessed by animals and humans, which contains faculties for sensation and movement, and (3) the rational soul, possessed by humans, which contains faculties for thinking and logic (Corthals 2014).

The similarities between Aristotle and the cauldrons go beyond just dividing the inner workings of humans into 3 categories of increasing intellectual complexity. Coire Érmae is moved by experiences of joy or sorrow, much like Aristotle's animals, with their animal souls, move in response to desires to experience pleasure or avoid pain (Corthals 2014, Aristotle 350 BCE/1907). Furthermore, the sensations experienced by the animal soul that lead to pleasure or pain are caused by external forces much like the sorrows that move the cauldron are caused by external forces (Aristotle 350 BCE/1907).

If Coire Goiriath is inspired by Aristotle's nutritive soul, this might explain the enigmatic glosses: 'it has closed off great falsehood', i.e. 'near to me in every land'. As the nutritive soul was only concerned with basic survival, Aristotle believed it was incapable of producing lies (Aristotle 350 BCE/1907), hence the Cauldron of Goiriath would be incapable of producing falsehood. As for the second gloss, a person always has their basic survival instincts with them, no matter where they go. The decision to replace types of souls with types of cauldrons might have been made by an Irish poet who was looking for imagery that was more familiar to their audience. (See Henry 1980 for other examples of cauldrons used in medieval Irish literature.)

While it seems unlikely than an 8th c. Irish poet actually read Aristotle, the poet may have had access to other works inspired by Aristotle's ideas. For example, the 7th c. writer Virgilius Grammaticus describes a 3-part soul that seems to have been derived from Aristotle. Virgilius might have been Irish, and even if he wasn't, parts of his writing definitely made it to Ireland (Corthals 2014).

In addition to the religious and philosophical elements I've discussed, 'The Cauldron of Posey' also contains quite a bit of material on secular Irish society with topics including the education of poets, the status of poets, and the role of poets in settling disputes (Breatnach 1981, 1984, Corthals 2014). In the section on divine joy, it appears the poet is trying to create unity between secular and ecclesiastic views of learning (Breatnach 1981). These things are well outside my area, but I do want to point out that there is more to this poem than religion.

'The Cauldron of Posey' contains an intriguing mix of Christian and Pagan, secular and ecclesiastic, foreign and native, cooked together into a single harmonious poem. It shows us that the transition from Pagan to Christian was a gradual process with elements of both existing side by side. It also shows us that religion was just one piece of Ireland’s cultural history, and if we focus exclusively a search for spiritual meaning, we risk missing out on the rich cultural details.

Bibilography:

Aristotle. (1907). De Anima (R. D. Hicks, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published ca. 350 BCE) https://archive.org/details/aristotledeanima005947mbp/page/n7/mode/2up

Breatnach, L. (1981). The Cauldron of Poesy. Ériu, 32(1981), 45-93. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007454

Breatnach, L. (1984). Addenda and Corrigenda to 'The Caldron of Poesy' (Ériu xxxii 45-93). Ériu, 35(1984), 189-191. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007785

Breatnach, L. (1990). On the Citation of Words and a Use of the Neuter Article in Old Irish. Ériu, 41(1990), 95-101. http://www.jstor.com/stable/30006290

Breatnach, L. (2023). Varia 1. Proclitic mis. 2. fírad. 3. Further to In Coire Érmae, ‘The Caldron of Poesy’. Celtica, 35(2023), 66-77. https://journals.dias.ie/index.php/celtica/article/view/6/5

Breatnach, P. (1983). The Chief's Poet. Proceedings of the RIA: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, 83C(1983), 37-79. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25506096

Carey, J. (1997). The Three Things Required of a Poet. Ériu, 48(1997), 41-58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007956

Corthals, J. (2014). Decoding the 'Caldron of Poesy'. Peritia, 24-25(2013-14), 74-89. https://www.scribd.com/document/721674860/Decoding-the-Caldron-of-Poesy

eDIL 2019: An Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language, based on the Contributions to a Dictionary of the Irish Language (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1913-1976) (www.dil.ie 2019). Accessed on 6/30/24

Gwynn, E. (1913). Royal Irish Academy Todd lecture series: The Metrical Dindshenchas Part III (Vol. X). Hodges, Figgis, & Co., LTD. https://archive.org/details/toddlectureserie10royauoft/page/n3/mode/2up

Henry, P.L. (1980). The Cauldron of Poesy. Studia Celtica, 14/15(1979/1980), 114-128. https://www.seanet.com/~inisglas/henrycauldronpoesy.pdf

MacNeill, E. (1924). Ancient Irish Law. The Law of Status or Franchise. Proceedings of the RIA: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, 36(1921 - 1924), 265-316. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25504234

Russell, P. (1995). Notes on words in early Irish glossaries. Etudes Celtiques, 31(1995), 195-204. https://www.persee.fr/doc/ecelt_0373-1928_1995_num_31_1_2070Russell 1995

#old irish#middle irish#early medieval#sorry about the cauldron puns#poetry#translation problems#8th century#irish history#the salmon of knowledge

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Irish language underwent several major and minor phonological and structural changes between its Primitive and Old’ periods. It might be said, | indeed, that it changed more during that time than it has ever done since. Words which at the Primitive Irish stage would have had four or two syllables frequently have only two or one respectively in Old Irish. The majority of the old case-endings were lost and replaced by a very different inflectional system, and a series of sound changes which in Primitive Irish were determined entirely by phonetic environment were raised by the Old Irish period to the status of morphophonological mutations and survive as such to the present day. Many of these developments can be seen taking place on the inscriptions, some are not detectable owing to the limitations of the alphabet while others, which belong to the Early Primitive Irish period not covered by the Ogams, had already run their course before the erection of the monuments and appear as a fait accomplion them."

— A Guide to Ogam by Damian McManus

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something interesting came up in my Irish class today when we were learning about family terms - the word for 'brother' in Irish has an interesting origin and had changed over time. I got curious and just had to look it up. Here's what I found (I love making these little etymology charts):

So I found this interesting explanation online about how this split happened because of Ireland's strong monastic tradition - apparently there were so many monks that people needed to distinguish between "brother" meaning a monk and an actual sibling.

But I have another theory too. In Old Irish, bráthair could mean not just "brother" but also "kinsman" or "cousin", kind of like how you might call fellow clan members "brother" (or like how nowadays we sometimes say "brother/bro" for close friends?). Maybe people started needing a way to specify "actual brother" versus "brother-in-arms" or "distant cousin"?

The etymology is fascinating either way - the 'derb-' prefix comes from the same root as English 'true' (both from PIE *drewh₂- meaning "firm/steady") and in Modern Irish it actually evolved into prefix dearbh- — real, blood-.

So nowadays these two words have distinct meanings in Modern Irish: bráthair has an ecclesiastical meaning, while deartháir specifically means a blood brother.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about the time I was in an Old Irish classroom and we were reading a poem about an Irish winter, and my teacher had the air conditioner on full-blast, conveniently hitting me in the face with its icy gusts. It's like she was trying to simulate the Irish winter we were reading about 😂😂😂

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

*Deh₂nu

*Deh₂nu- is a hypothetical goddess of water in Proto-Indo-European mythology, with connections to the names of rivers like the Danube, Don, Dnieper, and Dniester, as well as the Vedic deity Dānu, the Irish Danu, and the Welsh Dôn. Despite acknowledging a possible lexical connection, Mallory and Adams contend that there is not enough evidence to support the idea that a distinct river goddess existed in Proto-Indo-European beliefs. They primarily highlight the Indic tradition's understanding of river deification. Furthermore, Mallory and Adams suggest that a theory for a sea god called *Trih₂tōn—whose name is derived from the Greek Triton and the Old Irish word for sea, trïath—is unsupported by the lack of a corresponding sea god in Irish mythology and only minor lexical similarities. The Ossetian god Donbettyr is also mentioned in the story. Who is placated by gifts to keep the waterwheel turning, and who Donnán of Eigg proposes as a Christian equivilent of this figure.

Moreover, this deity and the Dan river in Centeral Asia may have similar etymologies.

She is frequently seen as the mother of a mythical tribe, the *Deh₂newyóes, in many Indo-European cultures; these tribes are deduced from the Vedic Danavas, the Irish Tuatha Dé Danann, the Greek Danaoi, and the Norse Danes. Under Bel's leadership, this tribe is said to have fought a hero called *H₂nḗrtos, which could connect them to characters like the Norse god Njord, the Nart from the Nart saga, and Indra's epithet nrtama.

#Irish#Vedic#Norse#Nart#Mallory#Irish Danu#Welsh Dôn#Irish mythology#hypothetical goddess#Proto-Indo-European#Welsh#Adams#Indic#Greek#Old Irish#Ossetian#Christian#Dan#Central Asia#Indo-European#Vedic Danavas#Tuatha Dé Danann#Danaoi#Bel#deity#sea#river#Norse Danes#tribe#druidicentropy

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have been rereading Damian McManus' 1991 A Guide to Ogam and have come to the conclusion that we really can't 'accurately' write ANYTHING in Ogam which has pretty much crushed my soul.

Oh sure, you can probably coble together something fairly legible using Old Irish and manuscript era Ogam phonetics... but even that is a rickety bridge to stand on 😭

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Put stained glass window cling in my window to help reduce the headaches I get from having the sun in my eyes while at my desk (and to make it easier to see my computer screen), and now even my Old Irish verb paradigms are gay :)

Unfortunately I still don't know what this specific verb is doing, mostly because I think it's doing Cursed Middle Irish Crimes. I'm gonna translate it as a passive because it seems to make the most sense, but god knows what it actually is.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

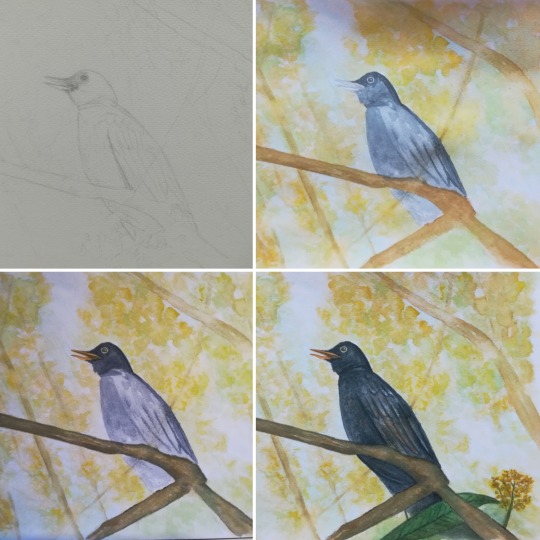

'Int én bec/ ro.léic feit/ do rind guip/ glanbuidi/ fo.ceird faíd/ ós Loch Laíg/ lon do chraíb/ charnbuidi.' "The little bird / has whistled/ from point of beak/ bright yellow;/ throws out a cry/ over Loch Laoi,/ a blackbird from branch/ heaped with yellow (blossom)". Watercolour illustration of the titular blackbird of this 9th Century Medieval Old Irish poem (October 2022) ����🍃🐤✨ This watercolour appeared in my published article translating this Old Irish poem into Quenya in Estel 99 (Summer 2023 edition of the official magazine of the Spanish Tolkien Society).

✨ArtStation: https://www.artstation.com/artwork/Nyk54N ✨Blogger: http://aeternalswirlingfight.blogspot.com/2023/10/quenya-translation-aiwe-int-en-bec.html

#tolkien#quenya#elvish#old irish#irish#translation#medieval ireland#medieval irish#gaeilge#blackbird#poetry#irish poetry#watercolour painting#watercolours#My art#My works#spanish tolkien society#sociedad tolkien española#ste#painting#traditional art#animal art#bird art#treescape#landscape art#forest painting#landscape painting#int én bec#int en bec#ireland

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The word tooth is a remnant of an ancient present participle meaning 'biting'. It is etymologically related to French dent, German Zahn, Irish déad, Ancient Greek odṓn, and Sanskrit dán. These words all stem from the same Proto-Indo-European ancestor.

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#english#latin#french#dutch#spanish#german#portuguese#catalan#italian#romanian#proto-celtic#old irish#irish#scottish gaelic#welsh#breton#danish#swedish#norwegian#icelandic#old norse#proto-germanic#frisian#low saxon#proto-indo-iranian#sanskrit

151 notes

·

View notes