#posedmodern

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Review: Crying Laughing Emoji

Is there a better representative of the postmodern era than the Crying Laughing Emoji? Doubt it 😂

A fellow of infinite jest, Crying Laughing Emoji has a character that wouldn’t be out of place in Hamlet or King Lear. A tragic/comic theatre mask for the internet age; an aggregate of glee and despair. Certainly a prevalent meta-game within pop culture du jour – it’s no coincidence that Hollywood pumps out legions of figures that are optimistically antiheroes or more realistically “sympathetic villains,” see Joker, Thanos; so on. They’re the ones that will expose the hard hitting realities of living in a society and hopefully make Chris Evans nodding sagely; infuriatingly kind of sexily, and saying “we’ll beat them – together” a little more tolerable in all his default smile emoji-ness.

This infamous emoji has earned its spot in the postmodern canon with a resume that boasts versatility and multiplicity of meaning. Its applications range from being an emoji substitute for “lol,” silencing opposition on Twitter, or being misinterpreted as an indicator of sadness. It’s a response to the $120,000 banana that posedmodern will inevitably rip into for a future article; it’s also the thing itself. As Marshall McLuhan once said, “the medium is the message.” It could also simply be someone laughing so hard that they’re tearing up, but nothing can really just be itself in a post-everything world. David Foster Wallace; “Time has changed Always.”

Inarguably, there is plentiful discourse surrounding the Crying Laughing Emoji. Abi Wilkinson takes a crack at it in a 2016 op-ed for The Guardian, categorizing the Crying Laughing Emoji as a “sniggering yellow bastard” and comparing it to gloating tendencies of reprehensible politicians such as Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage. There’s definitely some Trump visible within the emoji, for those reading in the U.S., but this is perhaps an unfair categorization for an emoji with no intrinsic political bias. The jeering, bodacious sort of “victory” that Wilkinson ascribes to the sobbing cacklers of the internet is enabled in no small part by intellectual frustrations: fuel for trolls, intellectual trolls, and troll intellectuals alike. In order words, to admit wrong-doing by the Crying Laughing Emoji is, in fact, to enable it. It’s like how the best thing you can do for the Joker is taking him seriously.

posedmodern score: 6.79453

postmodern because: Versatile; embraces a “multiplicity of meanings.” New, internet language. A creation of the 21st century. Provocative, but also fundamental.

#posedmodern#6#crying laughing#😂#memes#the guardian#im dead#joker#dark night#greek theatre masks#tragic#comic#comedy#tragedy#postmodern#defining postmodernism#postmodernism explained

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

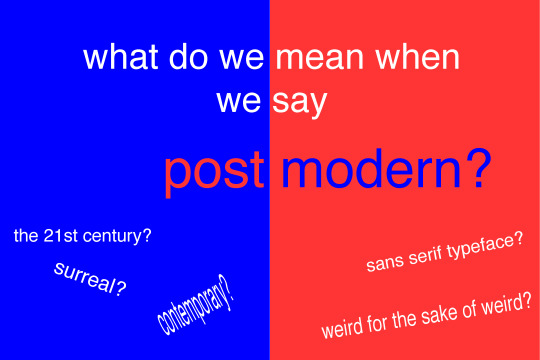

postmodern or not? part 1

In addition to reviewing and analyzing media produced post-1990, posedmodern is also committed to fostering a discussion on how postmodernism gets defined and understood. This post is the first installment of an ongoing series where we aim to share some perspectives on the topic as we explore how it manifests through media, academia, and the absurdity that is life in the 21st century.

In the third episode in the thirteenth season of Matt Groening’s The Simpsons, there’s a great moment where Moe (the series’ beloved bartender) opens a new postmodern-themed bar venture. When trying to explain it (if you click on one link in this article, let it be this one) to Homer & company, he affectionally abbreviates it as “po-mo” only to be met with blank stares. Opting for the non-abbreviated version has the same result, so he resignedly calls it “weird for the sake of weird” to a chorus of resounding “oh, I get it now”’s. It’s no coincidence that the often unreliable but also waxing philosophical but also probably alcoholic bartender is written as the one to associate with postmodernism. The movement, if we can even call it that, has never been associated with clarity of definition. Merriam-Webster only offers us “of, relating to, or being an era after a modern one” as its primary definition of postmodern. Characteristically, this is already tricky, because one must remember that in the academic realm, “modern” refers to the artistic and cultural movement that loosely ran from the beginning of the 20th century up until the 1980s, opposed to simply meaning “occurring in the present-time” or “contemporary. Even a strict timeframe for the modern era, the era by which one is supposed to define postmodernism as not being, is up for debate. We’ve barely scratched the surface and we already might feel as if we could use a stiff beverage.

Thankfully, much of postmodernism's characteristics lie within its murky definability – it can be seen as a movement that questions that which was accepted as “true” in all prior movements. To briefly roll with the aforementioned academic definition, the modern era is broadly seen as focusing on things like progress, objectivity, and rationality. Modernists valued progress and change, which began to encourage artists to move beyond the boundaries of traditional forms.

Pablo Picasso’s 1937 painting (pictured above), Guernica, is an exemplary modern painting. It evokes feelings of the sublime; perhaps to some it might even come off as being “weird” and “strange.”

But wait – these are things that we might notice in so-called postmodern works too! Does that mean Picasso was a postmodernist?

Not quite, but this is a valid observation. Guernica has a lengthy, nuanced historical context that has to be considered when we talk about it. Picasso found traditional methods to be insufficient to convey the horror and chaos of Guernica’s (a real-life city in Spain) bombing during The Spanish Civil War, so he opted for the abstract. This was a very modernist decision, as most thinkers in that era believed that traditional forms of art were no longer adequate means of creative portrayal in a rapidly industrializing world.

So then Moe is right in The Simpsons, and postmodern is just “weird for the sake of weird?” Guernica was weird for a reason, and we call it modern, and postmodern stuff is weird too, but I don’t see a reason for it. Can’t we just make pretty pictures?

Well, all work requires context. Some contexts are understood through the climate du jour, like how commodification and consumer culture are in Andy Warhol’s work. Others require personal contexts, such as the life and experiences of an artist. The thing with modern art is that the predominant contexts were those of progress, innovation, and a rebellion from traditional forms. While these are certainly present throughout postmodern media, artists had to dance to modernism's unmistakable tune to be considered relevant. “Progress” was so valuable in the modern canon that it, ironically, became detrimental to true innovation in art (at least in the eyes of the artists who came after), and a rebellion against modernism's obsession with “the new” was present in almost every movement to come after it.

The takeaway from this is that it’s generally easier to define postmodernism by what it isn’t. Modernism, and the various avant-garde sub-movements that it inspired through up until radical avant-garde, essentially lassoed groups of artists that made work talking about human society’s migration from point A to point B; each new movement a reaction to the old. Postmodern theory says that we don’t have to ascribe to such a linear understanding – in fact, we can’t. If we’re at point J in human history, we can talk about any point: Z, L, W, even A again.

Maybe in our next installment we’ll talk about what any of that actually means though.

#postmodern#posedmodern#modern#modernism#postmodernism#8#art theory#culture theory#pop#memes#dank memes#avant-garde#post-avant-garde#Warhol#Picasso#McLuhan#postmodern definiton#defining postmodernism#the simpsons

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

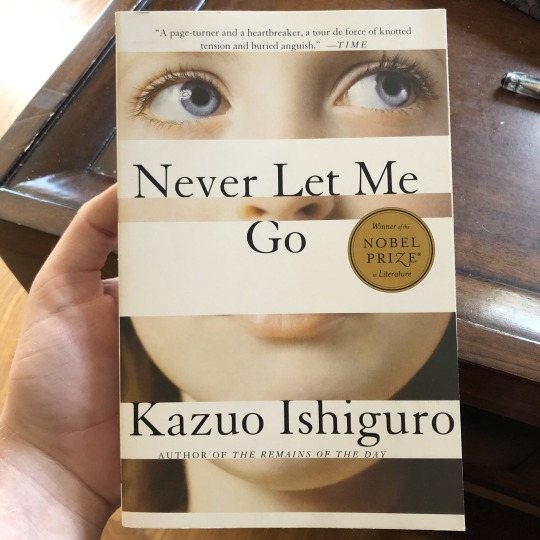

Review: Kazuo Ishiguro’s “Never Let Me Go”

Ishiguro’s 2005 novel, sold to me with the promise that “it WILL make you cry,” is a sort of Orwellian John Green endeavor. It’s teenage Brit soap opera for the first half before it pivots to Brit drama, going all in with the sci-fi tragedy in the conclusion that’s been sprinkled throughout. Somewhat backloaded, but never boring, Ishiguro writes with the authority and cohesion that you’d expect from a Nobel-in-Literature-winner.

The novel begins with narrator Kathy H. entering a lifetime recollection that forms the content of the entire novel. Of particular import are her two friends, Ruth and Tommy, along with the somewhat opaque boarding school – Hailsham – that a significant bulk of the novel occurs in. From his decision to begin the novel with an ending to his various allusions to his fantasy realist reality’s mechanics of “donations,” Ishiguro quickly establishes himself as the sort of writer that prefers slow, creeping dread opposed to having it all at once.

“As usual I was glancing into the empty rooms as I went past, and then suddenly I was looking into a classroom with Miss Emily in it. She was alone, pacing slowly, talking under her breath, pointing and directing remarks to an invisible audience in the room. I assumed she was rehearsing a lesson or maybe one of her assembly talks, and I was about to hurry past before she spotted me, but just then she turned and looked straight at me. I froze, thinking I was for it, but then noticed she was carrying on as before, except now she was mouthing her address at me.”

Strong instances like these, where an adolescent Kathy begins to witness snippets indicative of something sinister behind-the-scenes, have Ishiguro flexing his suspense muscles. This also fluidly translates into dialogue between a more grown-up trio as they tiptoe around a tense love triangle. Kathy would maybe feel like a non-character the same way Clay does in fellow sad-core teen drama 13 Reasons Why if Ishiguro wasn’t constantly in her head – allowing readers to get a fully fleshed-out, frank idea of why Kathy makes the decisions that she makes; why she tolerates Ruth’s bullshit for as long as she does.

What might be expected as being the central conspiracy is actually discerned fairly early on in the novel: that all students at Hailsham are being groomed for their organs to be harvested when they become of age. In the pseudo-dystopia of what Ishiguro calls “late 1990s Britain,” there isn’t much leeway in this, and the students are pretty much resigned to it and go about their lives without crippling depression regarding their inevitable harvesting.

The general solid structure and fluid writing seems to matter less towards the middle and through the end, where the rumored notion of a “deferral” from organ donation is revealed to be false. Expertly crafted setting dissolves a little bit as Ishiguro reveals a lot in a small amount of time, resulting in a slight thematic backload.

posedmodern score: 7.9

postmodern because: Exploration of denial experienced in the contemporary landscape. Art made by the children at Hailsham is always taken from them, a revelation experienced by Kathy and Tommy towards the end of the book. Similarly, Kathy and Tommy are denied a consummate relationship for a long while, thanks to Ruth settling with Tommy over the possibility of a deferral. It’s a nice coming-of-age story where no one gets what they want.

1 note

·

View note

Text

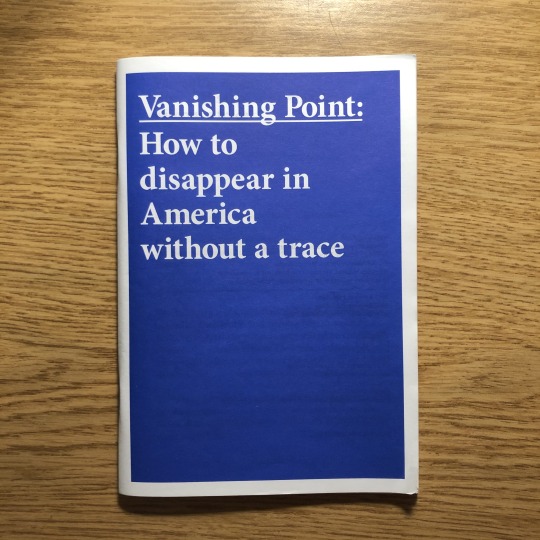

Review: “Vanishing Point: How to disappear in America without a trace”

I was a kid in a candy shop – hm, no, perhaps more of a child in the Lego aisle – when I got around to visiting Printed Matter in NYC for the first time a few months ago. Unfortunately, I had a budget, most of which had been blown on the taking-a-day-trip-to-New-York type of expenses. Fortunately, Vanishing Point was 8 USD, and at that price, it felt like a fair purchase.

TW: suicide mention

Edited by Susanne Bürner and published by Monroe Books, Vanishing Point: How to disappear in America without a trace is a republishing of an anonymous text originally posted to the now dead Skeptic Tank website. 135 staple-bound pages of what feels almost like bible paper, it’s printed in a lovely cyanotype blue Times New Roman with typos and all. It could fit in your pocket if your pockets are around the size of pockets on cargo shorts. You could go even smaller if you didn’t mind it getting warped or crinkled.

Vanishing Point is interesting for a lot of reasons. One thing that is immediately striking, however, is that the anonymous author’s voice is surprisingly apparent in the midst of a text that often defers to cold hard facts above everything else. Among the contents of this D.I.Y., off-the-grid how-to are handy tips on things such as how to use a gun, minimizing DNA evidence, “fright [sic] hopping,” and reducing body heat in case of helicopter searches. One of the most memorable passages details how to handle police dogs:

If a police dog confronts you with an officer, give up. If the police dog has been sent on ahead, kill the dog. You should sacrifice a bit of flesh to do this effectively: Offer your “dumb” hand to the dog and let it take it. (First wrap your arm in a shirt if you can.) Use the knife in your “smart” hand and try to drive it through the dog’s braincase.

Usage of the non-word “braincase” here is one of many slight acknowledgements of the author’s voice. Another one is when they very explicitly tell you to stop reading and kill yourself “if you’re thinking of hiding from a moral responsibility,” citing “child support” as their example. It was annoying having to read such a reactionary knee-jerk statement there, but to their credit, the author follows up with phone numbers for abuse and domestic violence hotlines. If I had to assign them an archetype, it might be Jaded Libertarian Grad Student.

While dated in places, the amount of practical information contained within Vanishing Point is nothing to scoff at. If you had any doubts about the difficulty of erasing your presence in the 21st century, this book will make it somberly clear: it’s real hard. There’s more information about surviving on the streets than there is surrounding the “erasure” aspects of disappearing – Section VII has a good chunk of text solely dedicated to scavenging edible food out of garbage. Turns out that the reality of running away rarely works out as nicely as it does in the movies, where you make a whole new identity and settle down with it in a modest suburban abode for the rest of your life. Though Vanishing Point definitely acknowledges its possibility.

Say “goodbye” to money.

I didn’t know if I would find a part of the book more depressing than where it tells readers to end their lives if they’re running away from a morally righteous undertaking. I ended up finding such a moment: where the author talks about how it's only gonna get harder to vanish as time goes on, bringing in an anecdotal passage from a “Justice James C. Nelson.” Apparently, it was from a ruling over a “case where a suspect’s trash that [sic] had been discarded.”

I also know that my most unwelcome and paternalistic relative, Uncle Sam, is with me from womb to tomb. Fueled by the paranoia of “ists” and “isms,” Sam has the capability of spying on everything and everybody – and no doubt is. But, as Sam says: “It’s for my own good.”

posedmodern score: 7.2

postmodern because: “Anonymous internet text” is already a huge trope in terms of what gets lumped in as being intrinsically po-mo because, let’s be real, where else are you going to encounter that outside of the 21st century? It’s also taking strides to be user-friendly (aside from, you know, that one moment) in line with the new value placed upon access and practicality.

#vanishing point#running away#review#postmodern#posedmodern#7#text#words#susanne bürner#anonymous#anonymous text

1 note

·

View note

Text

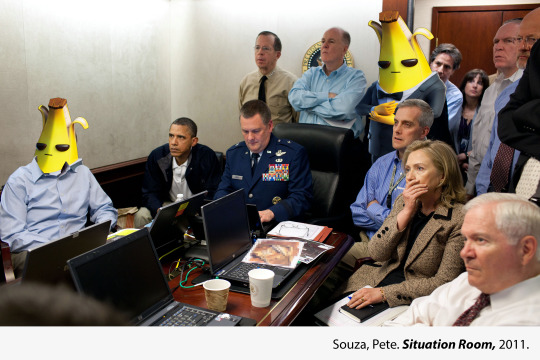

Review: Agent Peely

Between the Crying Laughing Emoji and The Simpsons, we’ve been reviewing a good amount (i.e., two) of yellow cartoon characters. Today, we’re back at it with a third: Agent Peely.

Beginning on the 20th of February and still running at the time of writing, Fortnite’s Chapter 2 Season 2 is an uninspired secret agent theme that kinda feels like Brad Bird in places, minus any ingenuity. You can fly in helicopters that are way too loud and realistic-sounding compared to how all of the audio normally works in Fortnite and you can get dusted by AI-controlled “henchmen” with fake language voices that channel Minecraft’s villagers except that the henchmen are so, so much more annoying. You can also be a spy and put on disguises and do everything else that you do in the game. It’s loads of fun.

Mortal fools like myself who shelled out 9.95 USD for a battle pass were greeted with a totally forgettable customizable skin (that boasts over 3 million options, all of which are hideous) and a handsome yellow bastard that isn’t the Crying Laughing Emoji: Agent Peely. A spy counterpart for chapter 1 season 8’s Peely skin, Agent Peely is the most sophisticated banana in Fortnite to date. His toughness and expression are enigmatic in a capacity that feels more fatherly and protective than it does menacing and could-probably-kill-you. A shining beacon of masculinity, free of toxins but for the ones built into the game.

One of this season’s gimmicks is that for almost every skin in the battle pass, players elect to choose a permanent style unlock (i.e. an alternative outfit) in either the “Ghost” or “Shadow” faction. Going for one will lock the other. Mysteriously, Agent Peely lacks this restriction: you can have the Ghost, Shadow, and even the secret solid gold style by simply playing the game with the battle pass. From a postmodern utilitarian context in which flexibility and accessibility are coveted, this fact alone would make Agent Peely the best skin of the season, no contest. But that’s not all – there’s Agent Peely lore. As mentioned in the trivia section of Agent Peely’s Gamepedia entry, the undercover banana’s access to all of the styles has some serious implications. Being a double agent in the tumultuous global political climate is damning enough, but is that really all there is to it?

posedmodern score: 9

postmodern because: Embraces a varied identity. More than what meets the eye. Open to interpretation. Engages with; affected by participants. Couldn’t necessarily have existed in any time other than the contemporary. Fun funny and ironic but also bursting at the seams with nuance.

work cited:

https://fortnite.gamepedia.com/Agent_Peely_(outfit)

Situation Room is work of the U.S. Federal Government, and is thus public domain.

#agent peely#fortnite#agent peely review#peely#banana#body horror#posedmodern#postmodern#defining postmodernism#conspiracy theory#lore#words#9#avant-garde#post-avant-garde#epic games#inside job#meme#dank

1 note

·

View note

Text

Review: Maurizio Cattelan’s “Comedian”

After all this scholarly debate, could it be that the definitive trait of postmodernism is simply the color yellow? Or maybe it’s the banana that’s postmodern. Maurizio Cattelan’s 2019 piece, Comedian, has made enough clickbait waves to nearly make us believe that to be the case.

Chances are that if you were looking around the trending sections on social media early December 2019, you came across something about the “$120,000 banana” or the “duct tape banana.” Featured in The New York Times, TMZ, Vogue, CNN; pretty much everything covered it.

As any of those articles will tell you, the duct tape banana is a conceptual artwork by Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan titled Comedian; it debuted over at Art Basel Miami Beach. It was eventually eaten by a performance artist by the name of David Datuna, briefly restored with a fresh banana, and finally taken down after Art Basel management deemed it a health and safety liability.

It’s easy to see how such a piece could provoke a slew of knee-jerk, “So This Is What Art Has Come To Huh” reactions. It’s also fairly simple to construct a pseudo-intellectual argument about how Comedian challenges our notions of what constitutes art, or how it might function as a critique of the harmony between capitalism and art. Unfortunately, it’s not especially spectacular in either regard.

It’s a boring continuation of an already tired, decade-old trope within anti-art, which (arguably) began with Duchamp’s Fountain in 1917, if not earlier. Artists like Andy Warhol, Ashley Bickerton, and Robert Rauschenberg, to name a few, furthered exploration of anti-art through the 20th century. It didn’t just happen with Duchamp and then resume again with Comedian. If we were asked to name a strength of the latter, we’d say that it’s perhaps dismayingly appropriate for an age so drenched in clickbait and sensationalism. Aforementioned artists’ work had comparatively more nuance, whereas Cattelan foregoes it entirely in order to create the most fundamentally reactionary piece he could cook up.

The most upsetting part of Comedian is its “$120,000″ branding that one will find mentioned in nearly every article written about it. This is so critical to the functionality of the piece that it could be titled $120,000 Banana Duct Taped to a Wall and practically have the same impact. The monetary factor is what gets the real clicks; there’s a banana on the wall scenario within most veins of contemporary art discourse. But this one’s $120k. It reeks of the all too common socio-politically “woke” art that begins and ends on a vague indictment with nothing to show for it.

Had it been framed around this discussion from the get-go, it would perhaps be more acceptable. As it stands now, however, Cattelan’s framing of the piece can be likened to a scientist raving about eugenics without considering the ethical repercussions. Comedian doesn’t provoke discussion, it provokes clicks.

posedmodern score: 0

postmodern because: “Anything can be art, am I right bros?”

image courtesy of Rhona Wise for Shutterstock

#comedian#maurizio cattelan#art basel miami beach#posedmodern#postmodern#postmodernism#anti-art#duchamp#bad art

0 notes

Text

postmodern or not? part 2

In addition to reviewing and analyzing media produced post-1990, posedmodern is also committed to fostering a discussion on how postmodernism gets defined and understood. This post is the second installment of an ongoing series where we aim to share some perspectives on the topic as we explore how it manifests through media, academia, and the absurdity that is life in the 21st century.

In our previous installment of this series, we began to discuss the complex task of nailing down a definition for “postmodernism.” While we didn’t make any significant progress on that front, we talked about defining postmodern via comparison to that which came before it – as many art movements are characterized by rejecting X quality of their predecessors. Unfortunately, this would require us to discern where exactly postmodernism began, a date that no one can definitively agree upon.

For further reading, check out this short & sweet article on postmodernism's characteristics from tate.org: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/postmodernism

For the sake of this post, let’s say that postmodernism began to rear its ugly head around the 1970s with artists like Andy Warhol and the radical avant-garde. Art theorists such as Charles Jencks have characterized the radical avant-garde movement as a bitter acknowledgement of emergent late capitalism’s grasp on art in an increasingly materialist society. A popular solution was to immerse oneself within the system in order to critique it, as many artists felt stuffed out and denied space to create novel work.

But like, have they even seen 2020?

“Almost anything carried to its logical extreme becomes depressing, if not carcinogenic.” - Ursula Le Guin

Art has never been the free-spirited absolutely basic component of existence that it’s often made out to be, and this discussion is in no way a new one.

We at posedmodern would also argue that the world has never quite looked like it does now in the 21st century.

An oft-encountered idea that first gained traction in the 1970s with the radical avant-garde is some variation of “great art might never make it into a museum.” Absolutely an innocent statement, but also one that easily blossoms into a (carcinogenic, with Le Guin in mind) chain of resultant questions.

How do we define “great” art in the first place? Since we’re way beyond the point of art being “good” or “bad,” and perhaps we always have been, we have yet another series of obstacles in determining how we should talk about art in the first place. Considerations like relevance, context, climate, history, and so on. If we go deep enough down this rabbit hole, we might venture beyond the point of no return. And then we have to deal with the accessibility roadblock, as we often look to academia and theory to draw our conclusions when our basic “common sense” (ew) and “aesthetics” (yikes) don’t suffice.

Returning briefly to the art historical canon, the 1990s were a fascinating time for both redefining art and expanding the definition of postmodernism. In all its MTV hellishness, artists active in this period made work with what has been retrospectively identified as a sense of “urgency.” Something like a Spider-Sense; an awareness of what was in store for a world that continued to implode without ever looking back. While capitalism continued to push pop culture and the trendiest next thing du jour, artists looked towards identity politics and the self for insight.

There was a beautiful moment where, for a hot second, it felt as if we could make amazing work by simply looking inward. You and I talking: that’s the art. Your beautiful body; you’re the art. A gross oversimplification of art made in this period? Yes absolutely. Did the emergence of the internet and its subsequent hyper-accessibility serve to upend this dynamic? Pretty much, yeah, because now everyone’s an artist. And before you come at us: no, that’s not a bad thing.

So where does that leave us?

It’s hard to say what this point in time will be named a few decades down the road. We haven’t exactly seen a “movement” like Pop Art or Anti-Art since the turn of the century, instead opting for secular terms like “internet art” or “new media art.” Until scholars and art historians figure it out, there’s really no time like the postmodern time (Era? Age? Period?). With its characteristics as varied as the 8+ billion people on earth, we can only tentatively say that it’s gonna be what we make of it.

0 notes

Text

about posedmodern

posedmodern is a blog that specializes in review, analysis, and discussion of any and all media produced post-1990. Specifically, posedmodern aims to contextualize both known and unknown work in the oft talked-about classification of postmodernism, discussing topics such as: Is everything made past a certain date intrinsically postmodern?

What distinction(s), if any, are to be made between contemporary and postmodern?

What exactly makes something postmodern in the first place?

In a post-everything post-world, posedmodern believes in takes more so than answers. We are more than content to offer opinions, but we’re not trying to make a definitive statement as to what postmodernism is or isn’t, nor are we claiming our assessment of media to be objective.

posedmodern is currently operated solely by [◼◼◼◼◼◼], a [◼◼◼◼◼◼]-native artist and writer. [◼◼◼] graduated from [◼◼◼◼] in [◼◼◼] with a dual B.A. in English and art, and is currently a MFA candidate with the writing program at [◼◼◼◼◼].

0 notes

Text

Review: “The Tatami Galaxy”

Masaaki Yuasa’s distinct set of stylistic and thematic tendencies were in many ways perfect for The Tatami Galaxy (2010). The animator blessed us with a welcome departure from the high-school-male-who-can-do-no-wrong trope that is recycled throughout legions of anime. The Tatami Galaxy provides viewers with a rare collegiate perspective that is flawed, human, and deeply relatable.

I struggle to think of a more significant transitory period in my life than the one I experienced during my switch from a high school senior to a college freshman. All of university’s oft-associated social conventions were byzantine and unfamiliar to me, and I don’t recall feeling properly “adjusted” until my third year of undergrad at the earliest. There were numerous instances before that where I would become broodingly introspective, wondering if the choices that I’d made up until a given moment had been the right ones.

If any of the above is even somewhat relevant to viewers, then they will likely find a small bit of themselves in the unnamed protagonist of The Tatami Galaxy.

Director Masaaki Yuasa’s break-out hit was the surreal, offbeat anime Kaiba in 2008. In addition to The Tatami Galaxy in 2010, his resume also includes Ping-Pong: The Animation (2014), Devilman Crybaby (2018), and most recently Keep Your Hands Off Eizouken! (2020). He has also made guest contributions to similarly quirky shows such as Adventure Time and Space Dandy. His style is especially recognized for its resistance of typical conventions found within the anime medium, i.e. slice-of-life, harem, Mary Sue-isms, etc. His dialogue is welcomely wordy but always thoughtful. His visuals, especially in Tatami, are delightfully loose and seem to become be whatever he needs them to be from scene to scene.

The central perspective of The Tatami Galaxy follows an unnamed, emerging third-year college student who can’t rid himself of the notion that he has somehow wasted his past two years. His missed opportunities include ventures with various student clubs, film-making, secret societies, and romantic pursuits. The narrative format of the series is somewhat unconventional: each episode is a condensed retelling of the protagonist’s first two years in college. Each iteration functions as a hypothetical vignette in which the protagonist made a distinct choice that he feels that might reward him with a “rose-colored college experience.”

Of course, each episode ends with what’s best case lingering melancholy or worst case complete disaster. The protagonist winds up dissatisfied no matter what he does, which necessitates the narrative “rewinding” to a fresh start that serves as the end of each episode before the final three entries. There’s no explicit fantasy element to the series, as the whole implied time travel occurs in the hyper-introspective protagonist’s internal considerations of hypothetical revisions of a collegiate experience that he feels was underwhelming and wasted.

The Tatami Galaxy is especially charming thanks to Yuasa’s expert characterization of college students. You have the jock-y yet pseudo-intellectual Jogasaki, who acts as a foil to the more introverted protagonist. There’s Ozu – the schemer – who often takes advantage of the protagonist’s jadedness. There’s romantic interest Akashi that works at the bookstore and collects mascot keychains, and there’s romantic interest Hanuki that the protagonist has to fight with Jogasaki for in a fratty drinking contest. There are also silly moments where the object of the protagonist’s affection is a life-like porcelain doll or Ozu in disguise.

However, as the protagonist comes to learn, college students don’t always act entirely within their tropes – this is where the tenderness of Yuasa’s writing really shines. The Gollum-like Ozu is revealed to be more sensitive than the protagonist initially thought, and is in fact just as insecure about his collegiate experience as his friend. The supporting cast is incredibly well fleshed-out, with dimensionality and nuance that could easily surpass that which is found in the “well-written” anime giants like Neon Genesis Evangelion. In convention-defying fashion, Yuasa delivers a heartfelt rendering of the collegiate experience in all its romance, chaos, and occasional serendipity.

posedmodern score: 9.2

postmodern because: A collection of similar, but different narratives – the majority of which occur in the protagonist’s mind as ventures into hypothetical experience. Stylistic choices help it stand out from other work in its medium.

images courtesy of Funimation, Masaaki Yuasa

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review: Kero Kero Bonito’s “Totep”

Released in 2018, the international trio’s four-track EP marked a transition in both instrumental and lyrical content. Known for their upbeat songwriting and bubblegum pop aesthetics, Totep sees Kero Kero Bonito exploring the challenges of positivism in a world that’s frequently dark and confusing.

Kero Kero Bonito (or KKB) is a British-Japanese band consisting of three members, vocalist Sarah and producers Gus and Jamie. On stage, their last names all become “Bonito.” Their first big splash came in 2014 with their single, Flamingo, which still remains their most popular song by a significant margin of around 35 million Spotify plays. Leaning heavily towards electro-bubblegum-pop, it’s an upbeat banger that invites listeners to love themselves in a way that’s thankfully more fun than it is preachy.

“Black, white, green or blue: show off your natural hues, Flamingo, if you’re multi-colored that’s cool too // You don’t need to change // It’s boring being the same // You’re pretty either way”

Sarah’s voice, a unique blend of Japanese and English accents, is nothing to scoff at – employing a tasteful, moderate amount of autotune in a genre that sometimes feels oversaturated with it. She also sings (and sometimes raps) as well in Japanese as she does in English, and will often switch between the two mid-song. However, Flamingo also has its instrumental and lyrical combo to thank for its success. The vocals feel surprisingly honest, unafraid of occasionally falling into the realm of cheese or tropes. On subsequent tracks, such as KKB’s 2016 single “Trampoline,” Sarah sings about the child-like rejuvenatory delight experienced upon revisiting an old trampoline.

A few remixes and similar songs continued to trickle out from KKB after “Trampoline” up until 2018 when Totep’s first single hit the streams: “Only Acting.” And just like that, everything fans knew about the band was fundamentally up-ended with a track so abrasive that it necessitated its own radio edit, something totally unheard of for KKB.

“Only Acting” features a Sarah Bonito that has clearly departed from her bubblegum origins. Instead, we are treated with what opens as wistful-sounding indie pop that crescendos into jarring, abrasive noise-rock.

“I thought I was only acting // But I felt exactly like it was all for real // I sure didn’t know it hurt so // But then no rehearsal could show you how to feel inside”

What felt like a jubilant, yet reasonable prescription of positivity in “Flamingo” and “Trampoline” feels retrospectively naive after listening to “Only Acting.” It could be mistaken as being some sort of “maturing,” but that would imply their previous work to be intrinsically immature, which it’s not. It might be more accurate to say that Totep sees KKB changing tracks – getting to the same messages, but taking the dark forest path instead of the sunset beach walk.

posedmodern score: 8.4

postmodern because: Totep marked the beginning of Kero Kero Bonito’s venture into their current hybridization of genres. Embraces the multiplicity of meanings, introspection, and unconventional song structure.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Review: Hiroyuki Nishigaki’s “How to Good-bye Depression”

Reviewing Hiroyuki Nishigaki’s How to Good-bye Depression is quite the undertaking. The introduction in which a critic might normally surmise or butter up the content feels inadequate for a book like this one. A stab at the typography? Or maybe the block quote included on the cover of the book: “If you constrict anus 100 times everyday. Malarkey? or Effective way?” posed modern weighs in.

Depression and postmodernism go together like Twin Peak’s Agent Cooper and cherry pie. They do fine on their own, but they’re better together. Sometimes they even exhibit a relationship that feels just short of parasitism. Where would the postmodern canon be without Joyce’s brooding Leopold Bloom, or Wallace’s weed-smokin’ tennis-playin’ Hal Incandenza? I shudder to even think about it. Nishigaki provides his own novel take on the essential po-mo trope with a book that oscillates between collected email correspondences and self-help monologues.

As it turns out, constricting one’s anus is only the first of six crucial steps to good-byeing depression laid out by Nishigaki. He also recommends a “[voluntary] trip into the hell” (as a means of ego-reduction), fighting, three-week fasts, reducing sex and masturbation “by half,” and “rotating your energetic [sic] vortex of your body.” After he gets this manifesto out of the way, the format then changes over to email correspondences. These are purported to be exchanges between Nishigaki and the people, inviting dialogue from willing anus constrictors and skeptics alike.

Hello I have also constricted my anus and dented my navel 100 times in succession almost everyday for about 18 years after I was taught by him. As a result, I have grown 10-20 years younger. Furthermore, I can overcome the stress of various complains [sic] which are the causes of depression. I owe much gratitude to him now.

Not everyone featured in How to Good-bye Depression is a believer. There are many emails that express doubt in the effectiveness of Nishigaki’s proposed self-help technique. Lots of people jeering and laughing. I found myself laughing here and there, but I was really fascinated by the email format and I wish that it hadn’t disappeared when he brought up the other, non-constrictive aspects of his proposed depression cure.

It’s a great gimmick book to have on your coffee table; fun to bring up with literature bros at parties perhaps, but not much else.

posed modern score: 200 divided by 100 consecutive anus constrictions = 2

postmodern because: Doesn’t adhere to conventions of formatting or spelling. Quite possibly fake. Depressing.

0 notes

Text

Review: Jin Kwang Kim’s “Shelf Life”

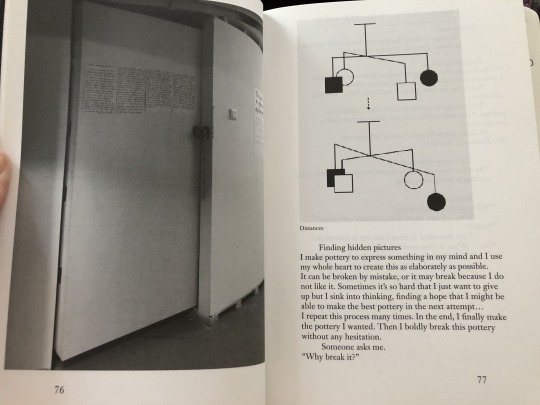

A review of the second book I was able to snag from Printed Matter last time I visited. Having picked this based on the cover alone – which doesn’t tell you much; you have to look for the title on the spine – I had no idea what to expect. The meta, heavily referential Shelf Life takes some patience to get into, but it’s a treat when you take your time with it.

New York-based artist Jin Kwang Kim’s Shelf Life starts on page 67. Meaning it begins with it, meaning that you open to the first page and you’re on what’s labelled as page 67. You’ll have to venture into the book’s physical center for a proper “page 1,” where you’ll find acknowledgements, an ISBN, and a title page. The content is mostly textual, occasionally pivoting to images. This results in a book that feels as much like a thesis paper as it does an art book. Kim doesn’t really try to disguise this, in fact, he openly admits to it. The preface, located just past the physical halfway point of Shelf Life, confirms that this is indeed his thesis work.

My thesis work falls between a twin interest in spirituality, which can refer to the search for a meaning in present life, and spiritualism, which often refers to a communication with a non-living spirit from the past or the future. […] This allows me to follow my interest in language and graphic design as something that exists in both material forms and as part of a more ethereal or metaphysical spirit of life.

Suddenly, everything makes sense. Or at least it begins to.

The 60 or so pages preceding the thesis statement feature a 50/50 combination of novel text from Kim and borrowed text from various artists, theorists, and writers. In line with his discussion of materiality, Kim’s voice fades in and out through Shelf Life. Sometimes it becomes difficult to tell where it’s him talking or where it’s one of the individuals that he is quoting, which became a small source of frustration for me as I’m not familiar with every reference. However, it seems that Kim would ask if such familiarity is necessary in the first place.

My thesis work has been motivated and shaped by different interests in the conceptual background framed here. It has provided a structure loose enough to trust my own feelings and approaches along a path guided by many influential spirits that will no doubt continue to influence and inhabit my work.

His external sources are not random snippets of inspiration; they more so build up the lens through which he approaches art-making. “If we both spoke logically all the time, we would never get anywhere,” echoes Gregory Bateson on page 68. Kim seems comfortable with having his voice merged with that of his influences. This concept is in itself essentially the entire content of Shelf Life: Kim’s work alongside everything that built it is, in fact, the work.

posedmodern score: 8.4

postmodern because: Kim takes a thesis statement, art portfolio, and various scholarly sources and makes a book out of it. The disruption of linearity and “common sense” honestly (but also, occasionally ironically) reflect the process of creation that is, at times, nonsensical and convoluted.

0 notes